ABSTRACT

Securing accountability of states for their climate actions is a continuing challenge within multilateral climate politics. This article analyses how novel, face-to-face, account-giving processes for developing countries, referred to as ‘Facilitative Sharing of Views’, are functioning within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and what these processes help to shed light on. We analyse the nature and scope of the ‘answerability’ being generated within these novel processes, including what state-to-state questioning and responses focus on, and what ‘performing’ accountability in this manner delivers within multilateral climate politics. We find that a limited number of countries actively question each other within the FSV process, with a primary focus on sharing information about the technical and institutional challenges of establishing domestic ‘measuring, reporting and verification’ systems and, to lesser extent, mitigation actions. Less attention is given to reporting on support. A key aim is to facilitate learning, both from the process and from each other. Much effort is expended on legitimizing the FSV process in anticipation of its continuation in adapted form under the 2015 Paris Agreement. We conclude by considering implications of our analysis.

Key policy insights

We analyse developing country engagement in novel face-to-face account-giving processes under the UNFCCC

Analysis of four sessions of the ‘Facilitative Sharing of Views’ reveals a focus on horizontal peer-to-peer learning

States question each other more on GHG emission inventories and domestic MRV systems and less on mitigation and support

We find that limited time and capacity to engage, one-off questioning rather than a dialogue, and lack of recommended follow-up actions risks generating ‘ritualistic’ answerability

Such account-giving also intentionally sidesteps contentious issues such as responsibility for ambitious and fair climate action but may still help to build trust

Much effort is expended on ‘naming and praising’ participant countries and legitimizing the process

1. Introduction

Securing state-to-state accountability is a key challenge for multilateral climate governance. Two components of accountability – answerability and enforceability – are difficult to secure in a global governance context. The latter is particularly challenging (Biermann & Gupta, Citation2011). Answerability is related to a given actor (in this case, a state) providing justification for its actions and behaviours to another. This can include demonstrating adherence to an agreed standard of environmental performance, and a judgement about whether an agreed standard of performance is met (Gupta & Van Asselt, Citation2019; Newell, Citation2008). Enforceability goes further in seeking to ensure compliance with standards of performance, through measures such as sanctions or liability for damages in case of non-compliance.

The enforceability component of accountability has been largely out of reach in the global climate context, as countries are reluctant to devise strong compliance mechanisms for international obligations. But what about answerability? Is state-to-state answerability for current and intended climate actions easier to realize in the climate context? This question is rarely posed, much less empirically analysed. In this article, we examine how recently institutionalized, novel, public, face-to-face answerabilityFootnote1 processes within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) function, and what kind of accountability they help further.

While the term ‘accountability’ does not appear in UNFCCC agreements, the concept is increasingly evoked in relation to the ever-greater levels of climate transparency demanded within multilateral processes. Transparency is widely assumed to be a precondition for enhanced accountability (Gupta et al., Citation2020; Mason, Citation2020). The assumption is that making visible what countries are doing will further accountability, and enhance mutual trust that progress is being made by all countries in meeting climate pledges (CEW, Citation2018; Gupta & Mason, Citation2016, Gupta and Van Asselt, Citation2019, Weikmans et al., Citation2020).

Whether such positive effects from transparency are being achieved remains to be empirically established. This question becomes even more relevant with the adoption of the 2015 Paris Agreement, which calls for an ‘enhanced transparency framework’ to be implemented by all countries starting in 2024 (United Nations, Citation2015, Art. 13). It is thus important to analyse how existing UNFCCC transparency arrangements have worked thus far, and the extent to which they have furthered state-to-state answerability for climate actions. This is our focus here, with particular attention to answerability processes in which developing countries are participating for the first time.

We proceed as follows: Section 2 discusses how accountability in global governance has been analysed in the literature. Section 3 describes evolving transparency and answerability processes within the UNFCCC, including differentiated arrangements for developed and developing countries and their political significance. Section 4 outlines our methodology for data generation and analysis of developing country participation in the face-to-face component of answerability processes, known as the Facilitative Sharing of Views (FSV). Section 5 presents our empirical analysis. We conclude by discussing our results in Section 6 and drawing out implications for the role of transparency and answerability processes in promoting the successful implementation of the 2015 Paris Agreement.

2. Accountability in global governance

Accountability is a fundamentally relational concept. Grant and Keohane (Citation2005, p. 29) define accountability as a relationship wherein ‘some actors have the right to hold others to a set of standards, to judge whether they have filled their responsibilities in light of those standards, and to impose sanctions if they determine that those responsibilities have not been met’. This definition implies several crucial components of an accountability relationship: it assumes that one set of actors is accountable to another; that this account-giving relates to agreed standards of performance; that it is possible to judge and assess if standards are being complied with; and that sanctions are possible if standards are not met (see also Biermann & Gupta, Citation2011).

Most of these elements are hard to realize in contested areas of global governance, ranging from nuclear non-proliferation to human rights to climate change (Chayes & Chayes, Citation1995; Groff & Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, Citation2018; Von Stein, Citation2016). Yet a public rendering of accounts by the actor to be held accountable is almost always a core element of accountability (e.g. Philp, Citation2009). In a global context, public accountability may help to legitimize the design, practices and outcomes of multilateral governance arrangements (Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, Citation2016). Given that public account-giving as institutionalized practice is relatively novel in the multilateral climate context, it is instructive to explore it here.

In doing so, we briefly consider publicly enacted peer review processes in another contested global governance domain, the international human rights regime, to distil propositions relevant to explore in the climate context. At the core of public answerability in the human rights regime is the Universal Periodic Review (UPR). The UPR falls under the remit of the UN Human Rights Council. Through the UPR, the human rights records of UN member states are periodically assessed against human rights benchmarks, such as treaties they have ratified. The process includes a publicly held, account-giving ‘interactive dialogue’ broadcast live on UN Web TV. Each country prepares a report on their human rights performance and publicly presents it. After the presentation, other countries may make comments or recommendations, or ask questions. The country under review responds at the end of the session but follow-up questions are not permitted.

While some have questioned whether this process actually constitutes a dialogue (Milewicz & Goodin, Citation2018, p. 518–519), it does force the country under review to react to points made. Much literature has analysed the UPR, focusing on country performance (Etone, Citation2017; Mao & Sheng, Citation2017; Smith, Citation2011, Citation2013), basis for review (Bernaz, Citation2009), or nature and scope of recommendations (McMahon & Ascherio, Citation2012). Less attention has been paid to the interactive exchange itself and what it achieves. The UPR is a response to the ‘bid to overcome (…) the alleged politicization’ (Dominguez Redondo, Citation2008, p. 722) of the UN human rights body, where naming and shaming states for violating human rights was seen as potentially biased. Given its intergovernmental setting, the UPR is state-controlled and inevitably political, with regional alliances playing an important role (Abebe, Citation2009, p. 8.19). Nonetheless, since all countries are required to go through the UPR, the process is, in theory, non-discriminatory.

Regarding content, many UPR interventions praise the country under review for its good performance but do not ask meaningful questions (Dominguez Redondo, Citation2008, p. 731). Some have argued this creates a risk of ‘ritualism’ (Etone, Citation2017), whereby states participate in ‘performing accountability’ yet to little effect (Charlesworth & Larking, Citation2015, p. 16). By contrast, Dominguez Redondo (Citation2012) contends that the value of the UPR does not lie in ‘naming and shaming’ countries using confrontational approaches, but in strengthening human rights norms through renewed commitments.

This makes the parallel with the multilateral climate context fascinating, because fostering answerability through face-to-face account-giving is emerging as important here too, but remains little examined. Is the claim of ritualism applicable here as well? Is naming and shaming the approach adopted, or are the dynamics distinct, in both theory and practice?

In analyses of accountability within global environmental governance, attention has focused in recent years on the rise of private governance, and hence on private, hybrid and plural accountabilities (e.g. Backstrand, Citation2008; Chan & Pattberg, Citation2008). International legal scholarship has retained its concern with state accountability, however, given a focus on compliance mechanisms in international treaties (Treves et al., Citation2009), including in the climate context (Oberthür & Lefeber, Citation2010; Voigt, Citation2016; Wang & Wiser, Citation2002). The political implications of (the lack of) state accountability for international climate commitments have also recently been the focus of renewed attention (e.g. Gupta & Van Asselt, Citation2019; Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen et al., Citation2018 Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen & McGee, Citation2013;; Steffek, Citation2010).

An important strand of literature on accountability within public management and policy studies offers an alternative to the more hierarchical, confrontational, legal and/or compliance-based understandings of state accountability in global environmental governance scholarship. This strand understands accountability as a process aimed at enhancing mutual learning, collaboration and facilitative trust building (e.g. Lehtonen, Citation2005). The novel face-to-face answerability processes of the UNFCCC may well reflect such an understanding of accountability. In our empirical analysis, we thus assess the kind of answerability sought and generated through these processes: i.e. whether it is a substantive, outcome-oriented answerability concerned with meeting formal commitments; or a procedurally-oriented answerability centred on facilitating learning and empowerment of participants (see also Mason, Citation2020). A further question is whether procedural, learning-oriented accountability generates substantive consequences, such as enhanced actions (Gupta and van Asselt, Citation2019; Weikmans et al., Citation2020).

Before exploring these aspects in our empirical analysis, we next describe the design of novel face-to-face account-giving processes within the UNFCCC and the political dynamics shaping their adoption and institutionalization.

3. UNFCCC transparency arrangements: evolution and political context

Within the UNFCCC, public answerability is organized via a cycle of country reporting about greenhouse gas (GHG) emission trends and national climate actions, and international review and/or analysis of these submitted country reports. We refer to these as UNFCCC transparency arrangements (also known earlier as ‘measuring, reporting and verification (MRV) systems’).

The most recent UNFCCC transparency arrangements, agreed in 2010 in Cancun and in operation since 2014, apply differentially to developed and developing countries, as have all earlier reporting obligations under the Convention (for a detailed overview, see Van Asselt et al., Citation2019). The 2010 Cancun transparency arrangements include two components: country reports generated domestically and submitted to the UNFCCC, and international review/analysis of submitted reports. As of 2014, developed (Annex I) countries are required to submit Biennial Reports (BR) that undergo a two-stage International Assessment and Review (IAR) process. The reports are first subject to a ‘expert technical review’ (ETR) by a team of UNFCCC appointed experts, followed by a face-to-face question-and-answer session with other Parties, referred to as a multilateral assessment (MA).

Developing countries (non-Annex I Parties) are also required to submit so-called Biennial Update Reports (BURs) starting in 2014 (this start date does not apply to least developed countries (LDCs) and small island developing states (SIDs), who can submit reports at their discretion). BURs undergo a two-stage International Consultation and Analysis (ICA) process. They are first ‘technically analysed’ by a ‘team of technical experts’ (TTE), with countries then participating in a face-to-face question-and-answer session, termed the Facilitative Sharing of Views (FSV). At this FSV session, developing countries present and respond to questions from other states (Parties) about the content of their BURs, including GHG inventories and the methodologies used to generate these, mitigation actions, support needed and received, and capacity building needs.Footnote2

These FSV sessions (and the corresponding MA sessions for Annex I countries, noted above) are organized during UNFCCC meetings, under the auspices of the Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI). The Chair of SBI presides over them (sometimes replaced by the vice-Chair or SBI rapporteur). In a 3-hour workshop, 5 countries participate, with 35 minutes on average allocated to each for a 15 minute presentation, followed by a 20-minute question-and-answer session. While non-state actors are present as observers, only Parties can pose questions. Parties may also submit written questions to a country ahead of time, to which responses can be given during the opening presentation at the FSV. As a culmination, the UNFCCC Secretariat compiles a summary of the presentation and question-and-answer session for each country and makes it available on the UNFCCC website, together with a web-recording of the FSV/MA session.Footnote3

In organizational set-up, the FSV sessions are thus similar to MA sessions for Annex I countries. The key differences are that the BRs and BURs have distinct reporting requirements, with more extensive reporting required from Annex I countries. The Annex I technical review is also more stringent than the technical analysis for non-Annex I countries.Footnote4 Furthermore, the ICA and its FSV for non-Annex I Parties is explicitly required to be ‘non-intrusive, non-punitive and respectful of national sovereignty’, with questions ‘on the appropriateness of domestic policies and measures’ remaining beyond its scope.Footnote5

These differences in transparency arrangements are related to extensive political contestations over the extent to which developing countries' reporting requirements should be on par with those of developed countries. A key political landmark in this debate was the 2007 Bali conference, when MRV for developing countries was actively discussed. Persistent conflicts came to a head during the 2009 Copenhagen conference, with developing countries such as China and India objecting to international ‘verification’ (in the terminology used then) of their voluntary climate actions. As Dubash (Citation2009) describes it, the conflict over developing country MRV ‘rapidly became one of the potential Copenhagen deal-breakers. Driven by its domestic politics, the US insisted that developing countries (but particularly China) also subject their actions to international scrutiny. Under the final compromise, non-Annex I countries are to report upon their mitigation actions, with ‘provisions for international consultations and analysis under clearly defined guidelines that will ensure that national sovereignty is respected’’ (Dubash, Citation2009, p. 10; see also Prasad et al., Citation2017).

The 2009 Copenhagen Accord thus laid the basis for the ‘international consultation and analysis’ terminology to which developing countries agreed to subject themselves under the 2010 Cancun transparency agreements. The IAR and ICA processes agreed here institutionalized continued differentiation between developed and developing countries, as reflected also in the distinct terminology (a technical review for developed countries versus analysis for developing countries; and a multilateral assessment versus a facilitative sharing of views). Despite this differentiation, developing countries did take on more stringent transparency obligations in the ICA than they had in the past (Van Asselt, Weikmans and Roberts, Citation2019).

In a key development, this continuing bifurcation in transparency processes between the ICA and the IAR has been phased out in the 2015 Paris Agreement ‘enhanced transparency framework’ (ETF). The ETF calls for submission of Biennial Transparency Reports (BTRs) by both developed and developing countries starting in 2024, which are to be subject to technical expert review and a face-to-face ‘facilitative, multilateral consideration of progress’ (UNFCCC, Citation2018).Footnote6 Strikingly, the mandate of this face-to-face process is very similar to that of the FSV, in that it is to be conducted in a ‘facilitative, non-intrusive, non-punitive manner, respectful of national sovereignty, and avoid placing undue burden on Parties’ (United Nations, Citation2015, art.13.3). In designing and implementing the Paris Agreement’s ETF, the aim is to build on lessons learned from the IAR/ICA process, upon which it has been modelled to large extent.

Given the contested politics around transparency obligations for developed versus developing countries in the UNFCCC over time, it is important to ascertain the kind of answerability being generated within these current, and hardly analysed, ICA/IAR processes, including their face-to-face public account-giving components. To begin to fill this research gap, we focus here on the first few years of the FSV process. We select this focus because of the historic nature of these FSV sessions, being the first time that developing countries have agreed to international scrutiny of their voluntary domestic climate actions and processes.

4. Methods

We outline here the methods we have used to assess the nature and scope of the answerability generated by developing country engagement in the FSV process. Our database consists of the first four FSV sessions (held in May and November 2016, and May and November 2017) during UNFCCC meetings. At least one author attended each of these FSV sessions. In addition, to generate our dataset, we transcribed the full proceedings of all four sessions, using the recordings publicly available on the UNFCCC website.Footnote7

The transcribed proceedings of the four sessions (with a total of 35 developing countries participating) were then qualitatively analysed through a mix of deductive and inductive coding. For the analysis, we used ATLAS.ti 8 – a computer software tool to facilitate analysis of large quantities of text. A number of preset codes were used to ascertain which countries asked questions within each of the four sessions, to whom these were directed, and what the questions focused on. The ‘about what’ category had three pre-set ‘mother’ codes. These were: measuring, reporting and verification (MRV); mitigation actions; and support needed and received. Additional topics were coded as ‘other’. Inductive coding was used to generate sub-codes under these mother codes, so as to capture diverse themes under each (see Annex I for a list of all codes).

Once all the material was transcribed and coded, we analysed the content of the questions that countries asked each other, in order to shed light on what countries seek to hold each other answerable for. We also ran quantitative analyses using Boolean operators and co-occurrence functions across all four FSV workshop transcripts to determine, (a) which questions were asked most often, (b) who asked the most questions and what they asked about; and (c) who was asked the most questions and by whom. This allowed us to identify emerging patterns in questions posed across the four FSV workshops. Finally, we read through all transcribed documentation to interpretively and qualitatively assess (without resorting to coding) the nature and scope of the answers provided to the questions posed.

5. Generating answerability: facilitative sharing of views

We present and discuss our findings here in four sub-sections. Section 5.1 presents patterns of engagement in FSV sessions, i.e. which countries were most actively engaged in questioning their peers. Section 5.2 illustrates the content of questioning, i.e. which topics are covered. Section 5.3 discusses dynamics of ‘naming and praising’ during questioning. Section 5.4 explores the nature and quality of answers.

5.1. Generating answerability: who participates in questioning?

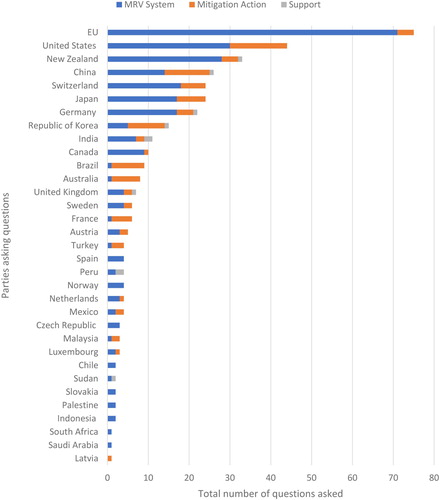

To discern patterns of engagement, the first-order question we asked was: ‘who was asking questions to whom’ in the four FSV sessions. Our findings reveal that, across all four sessions, developed countries asked the most questions, with the European Union, the US, and New Zealand taking the lead. China led in asking questions from among developing countries, followed by India and Brazil. Our data show that, over the four workshops, 34 countries asked questions, of which 12 were developing countries.

The countries who asked questions can be divided into the following categories (drawn from established Party groups of the UNFCCC):

EU and its member states

Umbrella group (non-EU developed countries): Australia, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, and the United States

The BASIC coalition: Brazil, South Africa, India, and China

The Like-Minded Group of developing countries (overlaps with the BASIC group but adds to the list Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Sudan)

Environmental Integrity Group, including Mexico, South Korea and Switzerland.

Additionally, a few countries who do not belong to the above-mentioned groups asked questions, including Singapore, Peru, Colombia, Palestine and Turkey. Groups of countries that had no, or only limited, representation in the first four FSV question-and-answer sessions included LDCs (only Sudan); SIDS; Arab States (only Saudi Arabia); African countries (only Sudan and South Africa); and Russia and former Soviet republics.

Our analysis also revealed that only four countries and one country grouping asked questions consistently across all four workshops: the EU, Japan, New Zealand and the US, and China from the group of developing countries. Others were active in some sessions but silent in others. Among developing countries, we observed a tendency to ask questions to regional ‘neighbours’, such as Chile asking Mexico, or Malaysia asking Vietnam.

displays who asked how many questions and also indicates the focus of questioning, which we discuss in more detail next.

5.2. Generating answerability: about what topics?

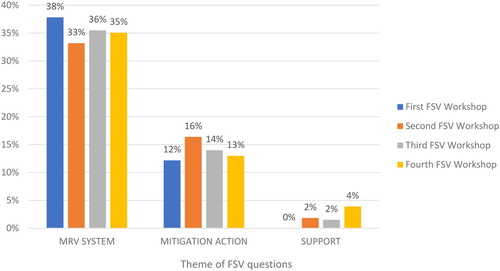

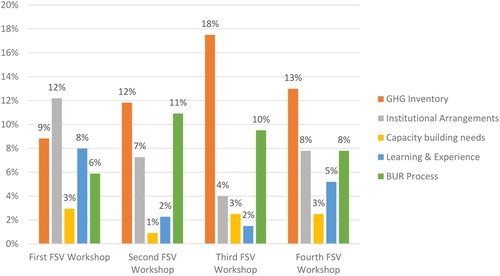

In assessing what was being asked about, we distinguished between three topics: MRV processes, mitigation actions, and support needed and received.Footnote8 We find that attention to each topic was relatively similar across the four workshops, as shown in (with the exception of support, which was hardly raised in the first workshop). As and also show, there was relatively little attention devoted to support, with most questions focusing on MRV processes, and to a lesser extent, mitigation. We elaborate below on the scope and content of questioning within each of these three main categories.

5.2.1. MRV processes

This main category covered several inter-related topics. We thus divided it into five sub-categories, and for coding purposes, we developed the following sub-codes: GHG inventory; establishment of the domestic MRV system; capacity building needs; preparation of the BUR; and lessons learnt from participating in the international ICA process.

In the first sub-category, GHG inventories, countries were questioned about technical issues around generating inventories, including data gaps, quality assurance and quality control systems, and methodologies used. Many enquiries related to whether a country was using the 1996 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Guidelines to prepare such inventories or the more comprehensive 2006 guidelines, or whether it was transitioning from one to the other. A representative example of questioning was the EU asking India: ‘What are India’s highest priorities in relation to improvements of the GHG inventory? What is India’s experience of using different guidelines in parallel in the BUR, does the presence of different sets of guidelines add to the flexibility needed in the inventory preparation process, or is this rather seen as a burden?’ In response, India provided more information on how it had generated its GHG inventory using 2006 IPCC guidelines, the quality of its inventory data, its plan to improve the inventory process and ongoing challenges faced in doing so.Footnote9

The second sub-category focused on establishing MRV systems at the national level, processes to institutionalize these systems, and whether they were established on a long-term or a temporary ad-hoc basis. Questions encompassed constraints faced in setting up these systems, identification of best practices, and data governance among relevant institutions, including data compilation and distribution, ensuring data quality and incentivizing local governments and non-state actors to provide data. A typical question was one Turkey asked Serbia: ‘What do you consider the biggest challenge of setting up a complete MRV system?’ to which the response was that domestic ‘monitoring and reporting is the biggest challenge, because there is a lack of understanding of respective ministries that they need to monitor and report on their actions’.Footnote10 Many others also noted this domestic data gathering challenge.

In the third sub-category, questions focused on what capacities needed to be developed to participate in transparency arrangements and to identify and undertake mitigation actions; whether capacity building needs had been identified, whether training had been conducted, and if so what kind, and with what outcomes. A representative question here was the UK asking Colombia whether it had ‘any advice for other countries looking to identify capacity building priorities, and how they should go about that?’Footnote11 Colombia’s response noted that public and private sector actors had very different assessments about capacity building needs, highlighting that capacity building is not just a technical matter (Klinsky & Gupta, Citation2019).

The fourth sub-category addressed lessons learned from engaging in the ICA process, including the technical analysis of the BUR. Questions focused on the perceived utility of the technical analysis, and whether engaging in the ICA cycle had contributed to improving the next BUR. As Austria asked Serbia: ‘you mentioned that the ICA process has improved your climate change action process and increased regional cooperation. Can you give another example of a positive outcome of this process?’ to which Serbia replied that it is ‘easier to learn by doing and learn from previous experiences of others … Regional cooperation is important because most countries have similar level of actions, activities and goals. But they have different levels of achievement of these goals. This way we can exchange views with partners in similar circumstances’.Footnote12

The last sub-category focused on the process of developing BURs. For example, India and Ecuador received questions from the US about institutional arrangements in place to generate the BUR. Peru, Indonesia, Macedonia, Thailand, and Mauritania were questioned about lessons learned and experiences gained from BUR preparation. Other questions addressed the role of external consultants in BUR development.

breaks down questioning according to five sub-categories of the MRV systems topic. It shows that GHG inventories and institutional arrangements for domestic MRV systems dominated questioning across the four workshops, but interest in best practices and lessons learned from BUR development and engagement in the ICA process was also high.

5.2.2. Mitigation

Questions on mitigation fell into two broad sub-categories. The first concerned past and current mitigation measures, where a majority of questions focused on (technical) aspects of mitigation measures, as well as policies and their implementation and outcomes. Questions often focused on sectors identified as important in the presentation, but sometimes also on sectors not mentioned. Japan often asked a country to identify the most important mitigation measures among the ones currently being pursued. Some questions concerned synergies or co-benefits of mitigation measures for sustainable development. A question from China to other developing countries was typical here, asking, for example, ‘Could Brazil share their experience with how to incorporate climate change goals in your sustainable development agenda, to achieve synergies in different areas?’ to which Brazil responded that they saw such a link as ‘beyond the scope of this exercise … [but] welcomed it very much, we have always defended since 1992 that climate change is a development issue’.Footnote13

A second category of questions around mitigation focused on enabling cross-country learning, including: advice for other countries seeking to take similar mitigation actions: lessons learned regarding policy tools for a sector, identification of good practices, and challenges facing countries in executing specific mitigation measures. Less often focused on were decision-making processes by which mitigation actions were determined. A notable exception was New Zealand’s question to Israel about its development of a mitigation action plan, and how it determined what share of emissions should come from different sectors. Israel’s answer here pointed to a domestic multi-stakeholder process that led to development of its mitigation action plan.Footnote14

In sum, under this category, questions focused on existing mitigation actions and, to a lesser extent, challenges faced in implementing these as well as intended future actions.

5.2.3 Support

Notably, there were only a handful of questions posed in the first four FSV sessions on support. This is surprising, given the importance of the topic to developing countries and because such questioning could have helped donors to prioritise countries and sectors needing support. Some questions focused on the challenges of increasing transparency of support received, as China asked Georgia, and India asked Jamaica. As Argentina noted in a remark that resonated broadly with others: it is difficult for countries to report on support received, because it remains challenging to separate climate finance from other financial flows.Footnote15

For the rest, questions tended to focus on support needed to prepare BURs and participate in the ICA process, rather than support needed for the taking of climate actions (mitigation or adaptation). One exception was the Republic of Korea asking Thailand about its priorities for international support in the energy sector, given that the country had noted a commitment to reduce GHG emissions 7%–20% by 2020, depending on the level of international support. India asked Thailand a related question about constraints faced in quantifying support needed for its planned energy sector mitigation measures. Thailand’s response noted a domestic goal of 7% energy sector emission reductions without support, increasing to 20% with international support, but emphasized the difficulties of estimating the level of support needed for energy efficiency measures, given that MRV here is complicated.Footnote16 This highlights a key issue meriting more research: whether this need to quantify levels of support may side-line measures that are suitable for a country but harder to quantify.

5.3. Generating answerability: naming and praising and legitimizing the process

In addition to specific topics covered, asking a question was often prefaced by statements expressing general appreciation for a country’s participation in the FSV. While this is a normal component of diplomatic processes, the extent of ‘naming and praising’ here points to a key dynamic of these early FSV sessions: to legitimize their utility and to signal the historic nature of this process, wherein developing countries were permitting a degree of formal international scrutiny of their voluntary climate actions for the first time.

Praise focused on the quality of the country presentation, on answers provided to written questions, on the quality of the BUR, and on being open during the question-and-answer session about challenges encountered, thereby enabling others to learn. Thus, the US commended Bosnia and Herzegovina for ‘identifying clear capacity constraints in your BUR’Footnote17 and Singapore thanked Vietnam ‘for being so open about the challenges [you have] faced because it helps us, the rest of the developing countries, realize that we’re not alone in the challenges that we face in the process. More importantly, we can together think of how we can address these challenges for all Parties’.Footnote18

Countries were also praised for being the first in their region or country grouping to take part in the FSV process, thereby setting an example for others. For example, the US (and the EU in similar words) thanked Mauritania ‘ … for setting an example to other LDCs and SIDS in submitting the BUR’.Footnote19 The FSV Chair’s words of appreciation at the end of the first FSV workshop were illustrative in this regard. He noted that:

‘These 13 Non-Annex I countries made this workshop historical. It is your active engagement, it is your in-depth discussions, the atmosphere in the room you have created … This is the demonstration of the true spirit and principles of ICA.’ (FSV 1, Chair Mr. Tomasz Chruszczow).Footnote20

On mitigation, appreciation for current and future commitments was expressed, as exemplified by Austria’s comment to Tunisia, ‘I was particularly impressed that you have a long term climate strategy in place up to 2050’, or Brazil to India, noting ‘how India has been able to promote the very impressive advances in such short time, and what is the role of government and private sector in designing and implementing these very ambitious policies’.Footnote21 This included praise for specific policy schemes, such as to the Republic of Korea for their national emissions trading scheme; or to Malaysia for preserving forests and going ‘above and beyond’ in its climate ambition and being a good example to others. An example was China’s praise for India:

‘Thanks for the presentation by India, it’s very comprehensive and detailed, and I think it’s very impressive about the solar initiatives, it sets a good example to the world and also a good example to the developing country Parties’.Footnote22

5.4. Generating answerability: the scope and quality of responses

In addition to the nature and scope of questioning, we comment here briefly on the quality and breadth of the answers provided.

In general, answers were comprehensive and contained substantial technical detail. In some cases, countries began their presentation by noting the prior written questions submitted by Parties, and integrating their answers into the presentation.Footnote23 This indicated that countries took the queries received seriously and made a good faith effort to respond in the time allotted. There was also no indication that countries considered some questions inappropriate, even those asking for more detail on mitigation plans.

In almost all FSV sessions, the Chair collected questions from several countries before giving the floor to the presenting country to answer them together. However, there were only very few instances when the presenter, after answering a question, asked if the response had been satisfactory, thus inviting further exchange. Noting lack of time, the Chair did not permit this line of enquiry to go further. There was thus almost no space for a dialogue or in-depth exchange about best practices or lessons learned.

6. Discussion: generating answerability or ritualistic performance?

We began our analysis with the question: What do face-to-face account-giving processes yield in this multilateral climate context? Here we synthesize and discuss our findings.

6.1. What kind of answerability? A focus on learning

First, what kind of answerability is being generated (and what kind is not) within these novel FSV processes, and how does this compare with the mandate of the FSV?

As designed, the FSV face-to-face account-giving sessions are public fora, where countries exchange information and are asked questions about their climate-related actions and national circumstances. As such, these sessions have clear elements of a public accountability forum. As we discussed in section 2, public accountability can take diverse forms, from hierarchical and compliance-focused, to collaborative and learning-focused. Our empirical analysis shows that the nature of account-giving in FSV processes is characterized by a polite exchange of encouragement among equals, representing a form of horizontal peer-to-peer accountability aiming to enhance mutual learning. Thus, we find that a predominantly procedural, accountability-as-learning form of answerability is being generated within FSV processes. The tone of the workshops, the types of questions asked, and how questions are framed, all point towards a cooperative rather than a confrontational approach to accountability, geared indeed towards, as the name suggests, a ‘facilitative sharing of views’.

This highlights that the kind of answerability being generated within the first sessions of the FSV is very much aligned with its mandate and intent, as described in Section 3. While this finding may be unsurprising, it is important nonetheless in revealing how a politically negotiated mandate is interpreted in practice, given long-standing contestations over international answerability for voluntary climate actions of developing countries.

6.2. Answerability-as-learning: what is being learnt, and who is learning?

If answerability-for-learning is indeed a key outcome of these FSV processes, in both intent and practice, then our analysis sheds light on a second question as well: what concretely is being learned (and what is not) and by whom? And what challenges are experienced in realizing mutual learning?

With regard to what is being learned, our findings highlight which topics received most attention during these sessions. As shown, the information exchanged (and thus the potential for learning) centred on technical issues such as GHG inventories, domestic MRV systems and, to a lesser extent, mitigation actions underway or planned. While the details exchanged do exhibit the potential for substantive learning and sharing of best practices, much less information was exchanged, for example, about support needed or received. In what was aired on this topic, some lines of questioning signalled concern about the challenges of quantifying levels of support needed for specific mitigation actions (such as energy efficiency). This brings to the fore a question meriting further analysis: whether certain mitigation actions that may be less amenable to quantification might be de-emphasized in favour of those that are more quantifiable.Footnote24 Whether transparency of support has become a more prominent focus of FSV sessions in recent years is also an important question, particularly in light of the increased significance of this topic under the Paris Agreement.

In general, our findings point to an important lacuna thus far in answerability-for-learning via these processes, whereby topics of central interest to developing countries might not be as prominently addressed in these sessions, partly because they remain voluntary elements of reporting (such as support needed and received, or even adaptation actions), compared to mandatory requirements (GHG inventories and mitigation). This merits further analysis. Equally important to consider is whether similar dynamics are at play in the developed country face-to-face MA sessions, or whether aspects such as support given by developed countries (a mandatory obligation), receive more sustained attention.

With regard to who is learning, our analysis reveals that certain groups of countries (e.g. LDCs and SIDs) were little engaged in the first four sessions of the FSV, including in questioning others. Again, whether this has changed since then, as experience and understanding of the FSV process has grown, will be useful to assess.Footnote25 Further empirical research is also needed to better understand the reasons for this relatively limited engagement, including whether it can be attributed partly to lack of human and other resources required to participate in asking questions, and/or whether such participation is not a priority for these countries for now.

Some criticism of design and operationalization of FSV sessions is now becoming evident in the grey literature, which is also relevant to the potential for mutual learning. For example, South Africa, in a submission to the UNFCCC, noted that since FSV sessions were held in parallel with the UNFCCC political negotiations, this hindered meaningful and inclusive participation from all, particularly from smaller developing country delegations. A key critique was also the lack of dialogue, and lack of recommendations provided on follow-up actions that countries subject to these processes could take (South Africa, Citation2017). Both of these latter aspects limit the prospects for learning and generating substantive answerability. Finally, factors such as language barriers (all FSV sessions were held in English, with no translation to other UN languages) might also present hurdles to learning.

6.3. Beyond learning: seeking legitimation of the process and recognition of effort

Beyond answerability-for-learning, our analysis highlights two other aims being furthered in practice within these novel FSV processes. First, we find that through naming and praising, developed countries in particular are keen to justify and legitimize developing country engagement in an international answerability process, given their longstanding demands for more climate transparency from developing countries. In the UN Human Rights Council, states under review in the UPR also systematically receive praise, even though their participation is mandatory.

As a mirror second aim, developing countries engaging in the first FSV sessions also see it as an opportunity to secure recognition for their (voluntary) climate efforts and for their active engagement in international transparency processes. Given contestations around having such answerability in the first place, both these aims are significant. They also raise the question of where and for whom the greatest value-added of these processes is perceived to lie: whether it lies in facilitating technical, content-based mutual learning between developing countries to improve reporting; or in legitimizing long-standing developed country demands for more transparency for all countries; or in securing international recognition of developing countries' voluntary climate actions; or even in generating financial support for proposed climate actions, through enhanced reporting on quantifiable mitigation initiatives that are candidates for such support.

6.4. Beyond learning: implications for enhanced action?

Finally, what are the implications of these findings for whether, and to what extent, enhanced transparency can help to stimulate enhanced climate action, and from whom?

As shown, the topics most focused on during the FSV sessions were technical aspects of establishing domestic MRV systems and engaging in the ICA process, and to a lesser extent, mitigation actions and support. Aligned with its mandate, FSV questioning avoided contested political questions, such as adequacy of effort or a country’s level of climate ambition. Thus links between face-to-face account-giving and enhanced climate action are not explicitly sought in these processes, with any such aspects, if addressed, refracted through an ostensibly non-contentious learning and capacity building lens (Klinsky & Gupta, Citation2019).

However, given that questioning focused on GHG emission levels and inventories, which are seen as key to deciding on mitigation actions, a key question for future research is whether further institutionalization of developing country reporting, and the learning and capacity building associated with these processes, stimulates enhanced mitigation commitments from developing countries (see also Weikmans et al., Citation2020). While this might be seen as the need of the hour by some, a concern voiced by developing countries during Paris Agreement negotiations was that enhanced transparency obligations would result in subtle pressure on this group of countries to take on more ambitious actions. As India put it, ‘[T]he transparency framework should not [create] de facto limitations on the extent to which Parties, particularly developing countries, may exercise national determination in shaping and communicating their NDCs [Nationally Determined Contributions] (UNFCCC, Citation2016, p. 33).

Whether engagement in subsequent FSV sessions and adherence to the Paris Agreement’s enhanced transparency framework does facilitate or push for enhanced climate actions from developing countries needs to be empirically assessed. Fieldwork in countries is required to assess domestic impacts and benefits versus burdens of engaging in UNFCCC transparency and account-giving processes. It is equally unclear whether the largely facilitative approaches to UNFCCC answerability can encourage much-needed climate ambition from developed countries as well, a key gap in knowledge that persists.

In this light, a question going forward is whether these ever-more institutionalized face-to-face account-giving processes within multilateral climate governance are serving to depoliticize contestations over where responsibility rests to undertake ambitious and fair climate action, and how to hold states accountable to each other on these aspects as well. This question pertains both to future processes under the Paris Agreement, but also to the MA sessions for developed countries under the current IAR process. The MA aims to generate answerability about Annex I countries’ progress in meeting quantified emission reduction targets, with a ‘view to promoting comparability and building confidence’. While such comparability of efforts is a crucial and potentially transformative impact of transparency, preliminary evidence suggests that comparability remains largely out of reach, at least in the formal process. Developed countries struggle, furthermore, to report on progress in meeting emission reduction targets and support provided to developing countries (Van Asselt, Weikmans and Robberts, Citation2019, p. 12), both issues crucial to multilateral climate politics.

7. Conclusions and implications for the Paris Agreement

Our analysis of novel, face-to-face public answerability processes in the UNFCCC reveals that these arrangements, and particularly the FSV sessions examined here, go beyond being a mere ritualistic ‘performance’ of accountability. Instead, they facilitate learning about key aspects of developing country climate reporting and actions, through rendering visible what countries are doing, particularly with regard to establishing reporting infrastructures and (planned) mitigation actions. They also facilitate a sharing of best practices and experiences, as well as challenges encountered. As such, they generate a (deliberately limited) form of learning-oriented answerability.

What are the implications of these findings for answerability processes envisioned under the Paris Agreement and its enhanced transparency framework? As we noted in Section 2, the ETF will be applicable to all countries. Its stated aim is to ‘build mutual trust and confidence and promote effective implementation’ of the Paris Agreement (United Nations, Citation2015, art. 13.1) and provide a ‘clear understanding of climate action … including good practices’. This latter emphasis on making visible good practices connects to the focus on learning that we observed in the first round of FSV workshops.

It is worth noting that the modalities, provisions and guidelines (MPGs, also called the ‘rulebook’) of the Paris Agreement’s ETF were negotiated in the period 2016–2018, and ran parallel to the implementation of the ICA/IAR arrangements. On the one hand, the push for ever greater transparency from all in this multilateral context is clearly emphasized, with the rulebook noting the ‘importance of facilitating improved reporting and transparency over time’ (UNFCCC, Citation2018: para 3b) from all. At the same time, the need to exclude any discussion of the level of ambition of countries is made even more explicit. Thus, the rulebook further specifies that the scope of the ‘facilitative, multilateral consideration of progress’ (the successor under Paris to the bifurcated FSV/MA face-to-face account-giving processes) is to cover only efforts that Parties make to implement and achieve their NDCs (UNFCCC, Citation2018, p. 189). Technical review teams are explicitly instructed not to review the adequacy or appropriateness of a Party’s NDC (UNFCCC, Citation2018, p. 149), and any Party can indicate if it considers questions to be outside the mandate’s scope (UNFCCC, Citation2018, p. 192.c).

Whether eventual implementation of the Paris Agreement’s ETF will also witness a side-stepping of contentious questions around ambitious and fair burden-sharing, as existing learning-oriented answerability processes are doing, remains to be seen. Specifically, whether the public face-to-face account-giving processes will enable more substantive, target-oriented answerability (from developing, but more importantly, from developed countries) is for future research to establish.Footnote26 Meanwhile, it is noteworthy that civil society has devoted relatively little attention to these FSV and MA processes. Notwithstanding their role as watchdogs in the multilateral climate regime, NGOs seem not to have considered these processes worthy of much attention, despite being permitted to observe proceedings. This raises the question of whether these answerability fora are indeed depoliticized technical spaces that merit little scrutiny, or whether they still have the potential, as widely asserted in policy rhetoric, to generate substantive answerability and promote appropriate, fair and adequate climate action by all.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this article, we use ‘answerability’ and ‘account-giving’ interchangeably. By both terms, we mean reporting and face-to-face question-and-answer processes, where states give an account to each other of their national-level emissions data and climate actions taken or planned.

2 Annex IV: Modalities and guidelines for international consultation and analysis, UNFCCC COP Decision 2/CP.17 43, http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2011/cop17/eng/09a01.pdf#page=43

3 Logistics of the FSV process are described at: https://unfccc.int/FSV#:~:text=1.,behalf%2C%20preside%20over%20the%20workshop

4 For detailed discussion of the differences, see Van Asselt, Weikmans and Roberts Citation2019.

5 International consultation and analysis for non-Annex I Parties, UNFCCC National Reports, http://unfccc.int/national_reports/non-annex_i_parties/ica/items/8621.php

6 As noted in Section 3, except LDCs and SIDs, who can engage at their discretion. Furthermore, compliance with reporting obligations for developing countries is subject to flexibility given differential capabilities.

7 The facilitative sharing of views under the ICA process, UNFCCC, http://unfccc.int/national_reports/non-annex_i_parties/ica/items/9382.php. We limited our transcription to the question-and-answer session following each country presentation. We did not transcribe or analyse the presentation itself, given our primary interest in the focus and nature of the questions asked and answers given.

8 In addition to the three themes included in , there was a fourth ‘theme’ we refer to as ‘other’ in our coding list (see Annex I). We do not reflect that here, hence the percentages in do not add up to 100%.

9 Third FSV Workshop, Bonn, Germany, 15 May 2017.

10 Fourth FSV Workshop, Bonn, Germany, 10 – 11 November, 2017.

11 Second FSV Workshop, Marrakech, Morocco, 10–11 November 2016.

12 Fourth FSV Workshop, Bonn, Germany, 10 November 2017.

13 First FSV session, Bonn, Germany, 20–21 May 2016.

14 Third FSV session, Bonn, Germany, 15 May 2017.

15 Second FSV Session, Marrakech, Morocco, 10 November 2016.

16 Third FSV session, Bonn, Germany 20–21 May 2016.

17 First FSV Session, Bonn, Germany, 20–21 May 2016.

18 First FSV Session, Bonn, Germany, 20–21 May 2016.

19 Third FSV Session, Boon, Germany, 15 May 2017.

20 First FSV Session, Bonn, Germany, 20–12 May 2016.

21 Third FSV session, Bonn, Germany, 15 May 2017

22 Third FSV session, Bonn, Germany, 15 May 2017.

23 Topics covered during Q&A were also included in each country’s presentation. While this may imply lack of need to follow-up on certain topics that may have been well-covered, the focus of questioning still gives an indication of the perceived importance to countries of the different topics.

24 For critical analysis of the politics of measuring, reporting and verification systems, and the ‘quantification’ turn in global climate governance, see Dooley & Gupta, Citation2017; Gupta et al., Citation2014; and Gupta et al., Citation2012.

25 Following the four FSV sessions analysed here, four more sessions have been held in 2018 – 2020. Information about FSV sessions is available at: https://unfccc.int/FSV

26 The ETF is not the only arena for peer-to-peer account-giving within the 2015 Paris Agreement. Nonetheless it is a foundational component that is to feed into other key mechanisms. One such is the Global Stocktake, a process that seeks to assess the adequacy of collective, if not individual, climate ambition in meeting temperature targets enshrined in the Paris Agreement.

References

- Abebe, A. M. (2009). Of shaming and Bargaining: African states and the Universal Periodic review of the United Nations human rights Council. Human Rights Law Review, 9(1), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/hrlr/ngn043

- Backstrand, K. (2008). Accountability of Networked climate governance: The rise of Transnational climate Partnerships. Global Environmental Politics, 8(3), 74–102. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep.2008.8.3.74

- Bernaz, N. (2009). Reforming the UN human rights Protection procedures: A legal Perspective on the establishment of the Universal Periodic review Mechanism. In K. Boyle (Ed.), New institutions for human rights Protection (pp. 75–92). Oxford University Press.

- Biermann, F., & Gupta, A. (2011). Accountability and Legitimacy in Earth system governance: A research framework. Ecological Economics, 70(11), 1856–1864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.04.008

- CEW [Clean Energy Wire]. (2018). Germany wants transparent global climate reporting to ensure trust. https://www.cleanenergywire.org/news/germany-wants-transparent-global-climate-reporting-ensure-trust

- Chan, S., & Pattberg, P. (2008). Private Rule-making and the politics of accountability: Analysing global Forest governance. Global Environmental Politics, 8(3), 103–121. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep.2008.8.3.103

- Charlesworth, H., & Larking, E. (eds.). (2015). Human rights and the Universal Periodic review: Rituals and ritualism. Cambridge University Press.

- Chayes, A., & Chayes, A. H. (1995). The New sovereignty. Compliance with international Regulatory agreements. Harvard University Press.

- Dominguez Redondo, E. (2008). Universal Periodic review of the UN human rights Council: An assessment of the first sessions. Chinese Journal of International Law, 7(3), 721–734. https://doi.org/10.1093/chinesejil/jmn029

- Dominguez Redondo, E. (2012). The Universal Periodic review – Is there Life beyond naming and shaming in human rights implementation. New Zealand Law Review, 4, 673–706.

- Dooley, K., & Gupta, A. (2017). Governing by expertise: The contested politics of (accounting for) land-based mitigation in a new climate agreement. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 17(4), 483–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-016-9331-z

- Dubash, N. (2009). Copenhagen: Climate of Mistrust. Economic and Political Weekly, XLIV(52), 8–11. December 26.

- Etone, D. (2017). The Effectiveness of South Africa’s engagement with the Universal Periodic review (UPR): potential for ritualism? South African Journal on Human Rights, 33(2), 258–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/02587203.2017.1362163

- Grant, R. W., & Keohane, R. O. (2005). Accountability and Abuses of Power in world politics. The American Political Science Review, 99(1), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055405051476

- Groff, M., & Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S. I. (2018). The Rule of Law as a global public good: Exploring Trajectories for Democratizing global governance through increased accountability. In S. Cogolati, & J. Wouters (Eds.), The Commons and a New global governance? (pp. 130–159). Edward Elgar.

- Gupta, A., Boas, I., & Oosterveer, P. (2020). Transparency in global sustainability governance: To what effect? Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 22(1), 84–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1709281

- Gupta, A., Lövbrand, E., Turnhout, E., & Vijge, M. (2012). In pursuit of carbon accountability: The politics of REDD+ measuring, reporting and verification systems. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 4(6), 726–731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2012.10.004

- Gupta, A., & Mason, M. (2016). Disclosing or obscuring? The politics of transparency in global climate governance. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 18, 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2015.11.004

- Gupta, A., & Van Asselt, H. (2019). Transparency in multilateral climate politics: Furthering (or distracting from) accountability? Regulation & Governance, 13(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12159

- Gupta, A., Vijge, M. J., Turnhout, E., & Pistorius, T. (2014). Making REDD+ transparent: The politics of measuring, reporting and verification systems. In A. Gupta, & M. Mason (Eds.), Transparency in global environmental governance: Critical Perspectives (pp. 181–201). MIT Press.

- Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S. I. (2016). Legitimacy. In C. Ansell, & J. Torfing (Eds.), Handbook of Theories of governance (pp. 194–204). Edward Elgar.

- Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S. I., Groff, M., Tamás, P. A., Dahl, A. L., Harder, M., & Hassal, G. (2018). Entry into force and then? The Paris agreement and state accountability. Climate Policy, 18(5), 593–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2017.1331904

- Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S. I., & McGee, J. (2013). Legitimacy in an Era of Fragmentation: The case of global climate governance. Global Environmental Politics, 13(3), 56–78. https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00183

- Klinsky, S., & Gupta, A. (2019). Taming Equity in multilateral climate politics: A Shift from responsibilities to capacities. In J. Meadowcroft, D. Banister, E. Holden, O. Langhelle, K. Linnerud, & G. Gilpin (Eds.), Chapter 9 in what next for sustainable development? Our Common future at Thirty (pp. 159–179). Edward Elgar.

- Lehtonen, M. (2005). OECD environmental performance review Programme: Accountability (f)or learning? Evaluation, 11(2), 169–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389005055536

- Mao, J., & Sheng, X. (2016-2017). Strength of review and Scale of response: A quantitative analysis of human rights Council Universal Periodic review on China. Buffalo Human Rights Law Review, 7, 1–40.

- Mason, M. (2020). Transparency, accountability and empowerment in Sustainability governance: A Conceptual review. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 22(1), 98–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2019.1661231

- McMahon, E., & Ascherio, M. (2012). A Step ahead in promoting human rights: The Universal Periodic review of the UN human rights Council. Global Governance, 18(2), 231–248. https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-01802006

- Milewicz, K. M., & Goodin, R. E. (2018). Deliberative capacity building through international Organisations: The case of the Universal Periodic review of human rights. British Journal of Political Science, 48 (2), 513–533. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123415000708

- Newell, P. (2008). Civil society, corporate accountability and the politics of climate change. Global Environmental Politics, 8(3), 122–153. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep.2008.8.3.122

- Oberthür, S., & Lefeber, R. (2010). Holding countries to account. The Kyoto Protocol's compliance system after four years of experience. Climate Law, 1(1), 133–158. https://doi.org/10.1163/CL-2010-006

- Park, S., & Kramarz, T. (eds.). (2019). Global environmental governance and the accountability Trap. MIT Press.

- Philp, M. (2009). Delimiting Democratic accountability. Political Studies, 57(1), 28–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2008.00720.x

- Prasad, S., Ganesan, K., & Gupta, V. (2017). Enhanced transparency framework in the Paris Agreement: Perspective of Parties. Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW).

- Smith, R. K. M. (2011). Equality of Nations large and small: Testing the theory of the Universal Periodic review in the Asia-Pacific. Asia-Pacific Journal of Human Rights and the Law, 12(2), 36–54. https://doi.org/10.1163/138819011X13215419937904

- Smith, R. K. M. (2013). To see themselves as others see them: The five Permanent Members of the Security Council and the human rights Council's Universal Periodic review. Human Rights Quarterly, 35(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2013.0006

- South Africa. (2017). Submission by South Africa to the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Paris Agreement on Transparency of Action and Support, 13 March 2017. On file with author.

- Steffek, J. (2010). Public accountability and the public Sphere of international governance. Ethics & International Affairs, 24(1), 45–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7093.2010.00243.x

- Treves, T., Tanzi, A., Pineschi, L., Pitea, C., Ragni, C., & Jacur, F. R. (2009). Non-Compliance procedures and mechanisms and the Effectiveness of international environmental agreements. T.M.C. Asser Press.

- UNFCCC. (2016). Parties’ Views Regarding Modalities, Procedures and Guidelines for the Transparency Framework for Action and Support Referred to in Article 13 of the Paris Agreement. FCCC/APA/2016/INF.3. UNFCCC, Bonn.

- UNFCCC. (2018). Decisions adopted at the Climate Change Conference in Katowice, Poland, 2-14 December 2018. Modalities, procedures and guidelines for the transparency framework for action and support referred to in Article 13 of the Paris Agreement. Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement.

- United Nations. (2015). Paris Agreement.

- Van Asselt, H., Weikmans, R., & Timmons Roberts, J. (2019). Pocket Guide to Transparency under the UNFCCC. European Capacity Building Initiative (ecbi), Available at: https://ecbi.org/news/pocket-guide-transparency-under-unfccc

- Voigt, C. (2016). The compliance and implementation Mechanism of the Paris Agreement. RECIEL, 25(2), 161–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/reel.12155

- Von Stein, J. (2016). Making Promises, Keeping Promises: Democracy, Ratification and compliance in international human rights Law. British Journal of Political Science, 46(3), 655–679. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123414000489

- Wang, X., & Wiser, G. (2002). The implementation and compliance Regimes under the climate change Convention and its Kyoto Protocol. RECIEL, 11(2), 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9388.00316

- Weikmans, R., van Asselt, H., & Timmons Roberts, J. (2020). Transparency requirements under the Paris Agreement and their (un)likely impact on strengthening the ambition of nationally determined contributions. Climate Policy, 20(4), 511–526. doi:10.1080/14693062.2019.1695571

Appendix 1: Coding scheme

COUNTRIES

First FSV Workshop

1.1. Countries Presenting

1.1.1. Azerbaijan

1.1.2. Bosnia and Herzegovina

1.1.3. Brazil

1.1.4. Chile

1.1.5. Ghana

1.1.6. Namibia

1.1.7. Peru

1.1.8. Republic of Korea

1.1.9. Singapore

1.1.10. South Africa

1.1.11. Macedonia

1.1.12. Tunisia

1.1.13. Vietnam

Second FSV Workshop

2.1. Countries Presenting

2.1.1. Andorra

2.1.2. Costa Rica

2.1.3. Colombia

2.1.4. Argentina

2.1.5. Lebanon

2.1.6. Mexico

2.1.7. Paraguay

Third FSV Workshop

3.1. Countries Presenting

3.1.1. India

3.1.2. Indonesia

3.1.3. Israel

3.1.4. Malaysia

3.1.5. Mauritania

3.1.6. Montenegro

3.1.7. Morocco

3.1.8. Moldova

3.1.9. Thailand

3.1.10. Uruguay

Fourth FSV Workshop

XX

4.1.1. Armenia

4.1.2. Ecuador

4.1.3. Georgia

4.1.4. Jamaica

4.1.5. Serbia

CODING THE QUESTIONS

QUESTIONS

5.1. SUBMITTED WRITTEN QUESTION

5.2. FSV QUESTION

5.3. COUNTRY ASKING QUESTION

5.3.1. Australia

5.3.2. Austria

5.3.3. Brazil

5.3.4. Canada

5.3.5. Chile

5.3.6. China

5.3.7. Colombia

5.3.8. Czech Republic

5.3.9. EU

5.3.10. France

5.3.11. Germany

5.3.12. India

5.3.13. Indonesia

5.3.14. Japan

5.3.15. Latvia

5.3.16. Luxembourg

5.3.17. Malaysia

5.3.18. Mexico

5.3.19. Netherlands

5.3.20. New Zealand

5.3.21. Norway

5.3.22. Palestine

5.3.23. Peru

5.3.24. Republic of Korea

5.3.25. Saudi Arabia

5.3.26. Singapore

5.3.27. Slovakia

5.3.28. South Africa

5.3.29. Spain

5.3.30. Sudan

5.3.31. Sweden

5.3.32. Switzerland

5.3.33. Turkey

5.3.34. UK

5.3.35. US

5.3.36. Unknown

MRV SYSTEM

6.1. GHG INVENTORY – (technical and process)

6.1.1. Technical Clarification on methodologies for estimating/(re)calculating emission data/time series/local emission factors

6.1.2. Experience with IPCC guidelines/adopting higher tier methods/times series (challenges & benefits & lessons learned)

6.1.3. Process for systematic collection, compilation and production of GHG inventory/time series to ensure consistency and efficiency

6.1.4. Challenges/Constraints/gaps in reporting inventory data

6.1.5. Improvement plans/future/inventory improvement planning (what and how)

6.2. INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS

6.2.1. Steps taken

6.2.1.1. To enhance capacity of institutions, coordinating units, working groups, national/sub-national sectors, national framework, action plans

6.2.1.2. To enhance capacity of experts: In-house experts, training programmes, phase out of consultants

6.2.1.3. To enhance information flow management: Data collection, archiving, sharing, analysis, timely BUR, procedures

6.2.2. Future steps / development of domestic MRV to guarantee continuity

6.3. CAPACITY BUILDING NEEDS (can also be indirectly referred to through constraints/challenges to develop MRV system)

6.3.1. Technical (IPCC guideline related/inventory report/time series)

6.4. LEARNING

6.4.1. Learning for own country

Lessons learned, best practices, constraints

6.4.2. Learning for other countries

6.5. BUR PROCESS

6.5.1. Experience and Learning (What a country has learned/appreciates from having gone through the BUR process/applying the guidelines)

6.5.1.1. Added Value

6.5.1.2. Challenges, constraints and gaps: Capacity building needs, financial resources, time taken to receive funding

6.5.1.3. Future improvement: Next BUR etc., Strengthening BUR process/system)

6.5.2. PRIORITIES: Identified through technical review

6.5.3. Process of preparing BUR

7. MITIGATION general; renewable energy/LULUCF/ other sectors;

7.1. GOVERNMENT POLICIES/actions/outcomes/experience

7.1.1. General: mitigation policy-making, flagship programmes, NAMAs, mitigation options

7.1.2. Specific: LULUCF, sinks, low carbon tech, REDD+, adaptation, emissions trading schemes, carbon tax, behavioural change, carbon tax, CDM

7.2. CONSTRAINTS / CHALLENGES

7.3. FUTURE PLANS/projections/targets/priorities/expectations: In mitigation relation areas/topics e.g. solar targets; in implementing mitigation actions

7.3.1. General

7.3.2. Specific

7.4. TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS: On quantification of mitigation effects/actions, methodologies/assumptions

7.5. MOST IMPORTANT MITIGATION ACTIONS

8. SUPPORT

9. OTHER

9.1. Praise

9.2. Context to question (usually on what the country has done)

9.3. Suggestions for improvement

9.4. Question is beyond the scope of the exercise

9.5. Opinion (we believe …)

9.6. Chair

9.7. Collaboration