Introduction

Thanks for a great 2017, and welcome to what will be a fantastic 2018. On behalf of the Editorial Board, we would like to take this opportunity to thank all our submitting authors, reviewers, readers and those citing the work published in Journal of Change Management for your ongoing and invaluable support. Without you, we would not have the thriving journal we have today. The Journal is moving from strength to strength, and is in a stronger position than ever. We are now indexed in the Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI), and although this does not give the Journal an Impact Factor as such, it does mean that we will have better data available on citations made to the Journal. Furthermore, citations from ESCI journals are tracked in the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and counted towards Impact Factor calculations. This is an important step towards achieving the long overdue inclusion of Journal of Change Management in the SSCI and securing a healthy Impact Factor. Indeed, we are confident that we will deliver on the previously stated aim of becoming the leading journal focusing on organizational change, its management and leadership.

2018 is promising to be another exciting year. We will see new special issues, new contributions to the popular Reflections and Conversation series, as well as the first contributions to our Point Counterpoint series. With these initiatives in mind, we would like to thank Jeff Ford for looking after our Reflections series, James Vardaman for being in charge of the brand new Point Counterpoint series, and John Amis and Mike Tushman for this year's Conversation.

The focus of this year's annual editorial is that of understanding teams in order to understand organizational change. In the quest for creating proactive, agile, adaptive and flexible organizations, the current focus of organizational change literature is predominantly on the organization as a whole and on the effects and contributions of the individuals within. Although work highlighting the necessity of applying a multi-level perspective has been published (e.g. Kuipers et al., Citation2014), the role teams play in organizational change is often overlooked in the literature. This may seem at odds with the many organizational change programmes that (a) are relying heavily on teams and teamworking (Whitehead, Citation2001); (b) are aiming to improve forms of teamworking within the organization (Sullivan, Sullivan, & Buffton, Citation2001); and (c) are affecting the functioning of teams considerably (Sanner, Citation2017). It seems even stranger taking into consideration that some change approaches are specifically dedicated towards establishing and developing teams in organizations (e.g. Agile working, TQM, BPR, Lean Management and self-organization). Moreover, on a practical level, the role of managers in implementing and fostering change particularly takes place within the teams they are part of or the teams they are managing (e.g. Neil, Wagstaff, Weller, & Lewis, Citation2016). Hence, teams form an essential part of organizational change as they are a means to initiate and successfully create and implement change, and subsequently are an important level of analysis to understand organizational change, successful or not.

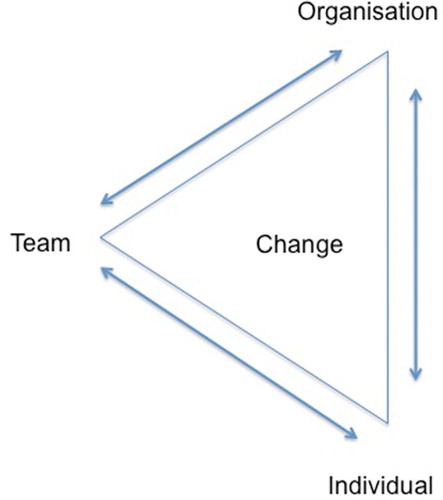

For these reasons, we aim to further explore the role of teams in organizational change by introducing the OTIC model (), with OTIC being an acronym for Organization-Team-Individual-Change. This model addresses the connections between three basic organizational levels. The first connection is the organization-individual nexus, on which most focus is put in current organizational change literature. We will discuss how through the role of autonomy the team level can play an important intermediating role. The second connection is the individual-team nexus. Here, we argue that individual and team autonomy interact with each other. The third connection is the team-organization nexus. This is the connection where organization philosophy and job design decisions have an impact on the role and shape of teamwork in creating and supporting proactive, agile, adaptive and flexible organizations. In each of these connections, we focus on the particular role of teams in organizational change. We follow Cohen and Bailey (Citation1997, p. 241) to define a team as

a collection of individuals who are interdependent in their tasks, who share responsibility for outcomes, who see themselves and who are seen by others as an intact social entity embedded in one or more larger social systems [for example, business unit or the corporation], and who manage their relationships across organizational boundaries.

Understanding teams and change

Organization-individual nexus

Looked at from one perspective – what Crowley, Payne, and Kennedy’s (Citation2014) review refers to as the ‘empowerment’ approach – the introduction of teamworking is unequivocally perceived as a good thing. This is due to its association with change towards greater autonomy and discretion for employees. As Batt (Citation2004, p. 187) expresses it, ‘workers in self-managed teams should experience higher levels of decision-making discretion’. These levels of discretion are, in turn, associated with higher levels of performance. Manz and Sims (Citation1987), for example, focus on participatory decision-making and individual discretion as important motivating factors, suggesting these will lead to more committed employees who strive for greater efficiency and effectiveness. For Cohen and Ledford (Citation1994, p. 14), self-managing teams ‘Work high in task variety, autonomy, identity, significance, and feedback [which] foster[s] internal work motivation, which in turn leads to high performance and satisfaction.’

While organizational change programmes can be undertaken on the basis of a general idea of ‘empowerment’, closer inspection shows that teams and teamworking per se often play only a small part in this. As Cohen and Ledford (Citation1994) point out, the type of work associated with teams is the same as the type of work also associated with job design models such as Hackman and Oldham’s (Citation1980) Job Characteristics Model. Because such models are applicable to the design of individual jobs, it can be difficult to identify the isolated effects of teamworking.

Currently, there is a strong tendency to conflate team-level autonomy with the discretion enjoyed by individual employees. The assumption (often implicit) is that organizational change takes place as, and through, change in the attitudes and values of employees. Teams might be part of this portrayal, but often only peripherally, as a result of their association with the broad idea of empowerment or autonomy. Teams, in this view, act merely as a cipher between the organization and the individual. In terms of the OTIC model (), it is the organization-individual nexus that is currently perceived as the essential one. However, there are strong arguments in support of further considering the other two connections. Namely the connections between the individual and the team, and between the team and the organization.

Individual-team nexus

So, what happens if, as Kirkman and Rosen (Citation1999) have argued, a clear conceptual distinction is made between individual and team autonomy, one not necessarily excluding the other? Explored as an empirical question, there is some evidence to support a positive link between team-level autonomy and individual-level discretion. Both Seibert, Silver, and Randolph (Citation2004) and Jonsson and Jeppesen (Citation2013) arrived at this conclusion. At the same time, however, we must allow for a negative relationship – or no relationship at all – between individual and team autonomy, and this has important implications both for research and for the management of organizational change.

Once individual and team-level autonomy are separated from each other, a number of possibilities are opened up. In terms of the OTIC model (), it can be argued that the nexus between team and individual needs to be given fuller consideration. There is a need to explore the possibility that individual and team-level autonomy might actually work in opposite directions to each other. Langfred (Citation2000) is amongst those who have argued that in the design of teams, organizations need to be aware that ‘autonomy at the individual level may conflict with autonomy at the group level’ (Citation2000, p. 581).

As Procter and Benders (Citation2014) point out, this conflict is one way of understanding the position taken by those critical of teams and teamworking: what Crowley et al. (Citation2014) call the ‘panoptican’ approach. From a panoptican perspective, a greater degree of team autonomy can be seen as the means through which individual autonomy is constrained or even reduced. Teamworking thus represents a change in the nature of control: individuals are now controlled by the team rather than by management directly. In Barker’s (Citation1993) account, for example, teamworking involves a move away from a rational, bureaucratic form of management control, and, in its place, the emergence of ‘concertive’ control, in which team members’ actions are controlled by normative rules which they themselves establish.

In addition to the ‘empowerment’ and ‘panoptican’ perspectives, Crowley et al. (Citation2014) refer to the ‘conflict’ perspective. While the empowerment and panoptican perspectives regard employees – positively or negatively – as rather passive conduits of change in organizations, the conflict perspective gives employee agency a much greater role in shaping its form and effects. As part of this approach, it is not always immediately apparent why any organizational advantages might be gained from teamworking. However, Procter and Currie’s (Citation2004) work on the UK civil service, for example, showed that despite teams only being able to exercise a limited amount of autonomy, teamworking appeared to have a clear positive effect on overall performance – a situation that Van den Broek, Callaghan, and Thompson (Citation2004) described as ‘teams without teamwork’.

The question then is how the apparently positive effects of introducing teams might be explained. The answer in broad terms seems to be that employees attach value simply to being a member of a team. Change in this direction is not inevitable, and there might even be differences between teams in the same organizational setting (Kuipers & Stoker, Citation2009). Teamworking proved effective in Procter and Currie’s (Citation2004) case because individuals identified with their team's work targets, and were willing to increase levels of efforts in order to achieve these. This was confirmed by later work in the same organization, which showed how this identification continued to be felt (Procter & Radnor, Citation2014). Demands made on employees had increased, but working as part of a team continued to be an aspect of work that many employees regarded in a positive light. What was important was the interdependence between members of the team and, in particular, the degree of outcome interdependence they experienced as a team. Where teams worked well, their work targets could be seen as providing the framework and incentive for a greater collective effort.

Team-organization nexus

The importance of teams is based on ‘the view that a group can more effectively apply its resources to address work condition variances within the group than can individual employees working separately’ (Manz, Citation1992, p. 1121). Thus for Stewart (Citation2006, p. 34), autonomy is one of the key elements of task design, since it ‘allows teams to improve performance through localized adaptation to variations in work environments and demands’. Within this view on teams, the concept of autonomy is an important feature, providing organizations with a greater level of flexibility to respond to exogenous forces.

The theoretical underpinning for autonomy in teams is provided by socio-technical systems (STS) theory. As Manz (Citation1992, p. 1121) argues, the ‘joint optimization’ of the social and technical aspects of the organization of work usually involves a ‘shift in focus from individual to group methods’. From an STS perspective, teams are the basic units, if not the main building blocks, of organizations (Mohrman, Tenkasi, & Mohrman, Citation2000; Trist, Citation1981), and exist in all kinds of forms and shapes, permanent and temporary, such as management teams, projects teams and operational teams (e.g. Cohen & Bailey, Citation1997). As such, teams serve different roles, functions and responsibilities.

To gain a full picture of how teams might (or might not) contribute to organizational change, we therefore need to look at the third nexus, that between the team and the organization as a whole. In other words, if team-level autonomy does not necessarily translate into individual-level discretion, its importance might instead lie at the level of the organization. At this level the team-philosophy is decided upon, with its effects on the organization design, supporting functions and leadership. Here we can distinguish between two different approaches to achieve organizational flexibility: by optimizing the hierarchical structure of the organization and thereby creating smoother production flows, or by downplaying hierarchy and creating adaptive work structures at an operational level (Adler, Citation1999; Glassop, Citation2002). Within the first philosophy, based on lean production and total quality management, teams of line operators work on particular process improvements, whereas in the second philosophy, based on STS, (semi) autonomous teams organize their full range of work activities dealing with all issues they come across (Glassop, Citation2002).

Teams and organizational change: current trends and future prospects

Currently, we observe renewed attention on organizational teams and teamwork in support of utilizing the advantages of autonomy and (certain levels of) self-organization. After previous periods of popularity in the 1960s, especially self-managing teams and the rise of the organizational development movement (Van Eijnatten, Citation1993), and between the 1980s and the beginning of 2000 by the upswing of the socio-technical approach and lean production, particularly in industrial settings (Adler & Borys, Citation1996; Berggren, Citation1993), the concepts of teams as more or less self-organizing entities in organizations were revived a couple of years ago. Not only under the heading of agile and scrum in the context of IT (Hossain, Babar, & Paik, Citation2009), and ecosystems as organic networking between organizations (Adner & Kapoor, Citation2016), but also throughout the setting of private and public service delivery. For instance, in the health care sector in the Netherlands, a major shift of responsibilities has been made towards healthcare professionals in teams at operational level as a result of government reform (e.g. Van der Voet, Steijn, & Kuipers, Citation2017). This can be seen as part of a trend where organizations are self-organizing through self-organizing or self-managing teams, to which Laloux (Citation2014) refers to the ‘Teal paradigm’.

The developments outlined above all have in common that they do not entail relatively simple structural changes, but require careful implementation of new ways of working on all levels of the organization. A major criticism of organizational change literature presented by Pettigrew and colleagues (Pettigrew, Citation1985, Citation1990; Pettigrew, Woodman, & Cameron, Citation2001) and others, is on the dominant focus on content issues including strategies and structures, versus the relatively small attention on the role of the change processes required to implement and shape these very structures and strategies (Armenakis & Bedeian, Citation1999; Kuipers et al., Citation2014). A similar critique can be found in the team literature, as the structural and design issues of teamwork usually receive much more attention than the issues regarding implementing and developing teamwork (Kuipers, De Witte, & van der Zwaan, Citation2004). As such, both fields share a similar pitfall, but can also delve on each other’s strengths to combine knowledge on work teams and change approaches.

Fundamentally, two of the dominant approaches to organizing work teams relate to the two dominant organizational change approaches: the lean production model of teamwork and the top-down Theory E approach to change, versus the STS approach to teamwork and the bottom-up Theory O approach of change. In , we highlight some of the key-characteristics of each of them (based on Beer and Nohria Citation2000; Kuipers, Citation2005).

Table 1. A comparison between the key-characteristics of dominant approaches to teamwork and organizational change (based on Kuipers, Citation2005; Beer & Nohria, Citation2000).

The comparison of approaches in sets out some important similarities between the dominant approaches to teamwork and organizational change. The lean production approach to teams and the more planned approach of Theory E have in common that the focus is on hierarchy, process improvements and extrinsic motivation of various stakeholders. The role of individual and team autonomy is perceived as being limited. The STS approach to teamwork and the emergent approach of Theory O share a more bottom-up philosophy with decentralized control aimed to increase intrinsic motivation to learn and experiment in order to enable change. In other words, there are contingencies between the type and role of teamwork and these change approaches, and the combination of each pair serves different purposes. By making use of these, more effective implementation processes can be applied to introduce and develop the different types of teamwork, but more importantly; the meaning of the team level and the nature of autonomy in change processes becomes more apparent.

Conclusion

By introducing the OTIC model, we are setting out to further explore the role of teams in organizational change. We are stressing that in the process of creating and sustaining proactive, agile, adaptive and flexible organizations, teams should not be looked at as merely a cipher. Rather, teams are important objects of change, are meaningful units to contribute to various types of change, and subsequently need to be studied as a separate level between the organization and the individual to fully understand and analyse change. In the organizational change literature, there is a focus on level of participation, and the role of employees’ autonomy and empowerment in increasing awareness, commitment, support, as well as change outcomes (e.g. Armenakis & Harris, Citation2009; Fuchs & Prouska, Citation2014; Joffe & Glynn, Citation2001; Lines, Citation2004; Van der Voet, Kuipers, & Groeneveld, Citation2016; Van der Voet, Groeneveld, & Kuipers, Citation2014). Combining this with the team literature which provides us with a conceptual framework to consider autonomy in a more concise way, we can further explore the role and importance of the team level when considering organizational change.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Rune Todnem By is Professor of Organisational Behaviour (Staffordshire University, UK) and Change Leadership (University of Stavanger, Norway), and is the serving Editor-in-Chief of Journal of Change Management. As well as delivering change and leadership sessions on MBAs and Executive MBAs, He is delivering keynotes, sessions and courses to organizations in private, public and third sector. Furthermore, he is co-founder and previous Chair of Public Leadership Foundation. He is widely published and cited, and his current research is focusing on leadership as a verb. Twitter: @Prof_RuneTBy. Email: [email protected]

Ben Kuipers is Associate Professor at the Institute of Public Administration, and manager of Leiden Leadership Center in The Hague (Leiden University, The Netherlands). His specialization is in the areas of public leadership, organizational change and teamwork. His current research is about the changing nature of leadership in the Dutch healthcare sector after the introduction of self-organization within the context of large-scale government reforms. He is also working as an independent consultant for Verbetervermogen in both private and public organizations, focusing on the development of leadership and teamwork. Furthermore, he is a co-founder and board member of the Public Leadership Foundation and Editor-in-Chief of the Holland Management Review. Twitter: @benskuipers. Email: [email protected]

Stephen Procter is Alcan Professor of Management (Newcastle University Business School, UK) and head of the Human Resource Management, Work and Employment (HRMWE) research group. He is also co-founder and organizing committee member of the International Workshop on Teamworking (IWOT), committee member of the British Academy of Management's Special Interest Group on HRM, and Treasurer of the British Universities Industrial Relations Association. He has an international reputation for his research in the management of organizational change and the development of new forms of work. Recent papers have included an examination of teamworking in the context of lean production in the UK civil service (see Procter and Radnor, Citation2017). He is currently involved in a study of team-based organizing in a large US-based multinational. Email: [email protected]

ORCID

Rune Todnem By http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3817-049X

Ben Kuipers http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0592-1709

Stephen Procter http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7408-3721

References

- Adler, P. S. (1999). Building better bureaucracies. The Academy of Management Executive, 13(4), 36–47.

- Adler, P. S., & Borys, B. (1996). Two types of bureaucracy: Enabling and coercive. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(1), 61–89.

- Adner, R., & Kapoor, R. (2016). Innovation ecosystems and the pace of substitution: Re-examining technology S-curves. Strategic Management Journal, 37(4), 625–648. doi: 10.1002/smj.2363

- Armenakis, A. A., & Bedeian, A. G. (1999). Organizational change: A review of theory and research in the 1990s. Journal of Management, 25(3), 293–315. doi: 10.1177/014920639902500303

- Armenakis, A. A., & Harris, S. G. (2009). Reflections: Our journey in organizational change research and practice. Journal of Change Management, 9(2), 127–142. doi: 10.1080/14697010902879079

- Barker, J. (1993). Tightening the iron cage. Administrative Science Quarterly, 38, 408–437. doi: 10.2307/2393374

- Batt, R. (2004). Who benefits from teams? Industrial Relations, 43(1), 183–212.

- Beer, M., & Nohria, N. (2000). Cracking the code of change. Harvard Business Review, 78(3), 133.

- Berggren, C. (1993). Alternatives to lean production: Work organization in the Swedish auto industry. Ithaca, NY: ILR Press.

- Cohen, S. G., & Bailey, D. E. (1997). What makes teams work: Group effectiveness research from the shop floor to the executive suite. Journal of Management, 23(3), 239–290. doi: 10.1177/014920639702300303

- Cohen, S., & Ledford, G. (1994). The effectiveness of self-managing teams: A quasi–experiment. Human Relations, 47, 13–43. doi: 10.1177/001872679404700102

- Crowley, M., Payne, J., & Kennedy, E. (2014). Working better together? Empowerment, panopticon and conflict approaches to teamwork. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 35(3), 483–506. doi: 10.1177/0143831X13488003

- Fuchs, S., & Prouska, R. (2014). Creating positive employee change evaluation: The role of different levels of organizational support and change participation. Journal of Change Management, 14(3), 361–383. doi: 10.1080/14697017.2014.885460

- Glassop, L. (2002). The organizational benefits of teams. Human Relations, 55(2), 225–249. doi: 10.1177/0018726702055002184

- Hackman, J., & Oldham, G. (1980). Work redesign. Reading, MA: Addison–Wesley.

- Hossain, E., Babar, M. A., & Paik, H. Y. (2009, July). Using scrum in global software development: A systematic literature review. In Global software engineering, 2009. ICGSE 2009 (pp. 175–184). Limerick.

- Joffe, M., & Glynn, S. (2001). Facilitating change and empowering employees. Journal of Change Management, 2(4), 369–379. doi: 10.1080/714042517

- Jonsson, T., & Jeppesen, H. (2013). Under the influence of the team? International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(1), 78–93. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2012.672448

- Kirkman, B., & Rosen, B. (1999). Beyond self-management. Academy of Management Journal, 42(1), 58–74. doi: 10.2307/256874

- Kuipers, B. S. (2005). Team development and team performance. Responsibilities, Responsiveness and Results: A Longitudinal Study of Teamwork at Volvo Trucks Umea. University of Groningen, Groningen.

- Kuipers, B. S., De Witte, M. C., & van der Zwaan, A. H. (2004). Design or development? Beyond the LP-STS debate; inputs from a Volvo truck case. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 24(8), 840–854. doi: 10.1108/01443570410548257

- Kuipers, B. S., Higgs, M., Kickert, W., Tummers, L., Grandia, J., & Van der Voet, J. (2014). The management of change in public organizations: A literature review. Public Administration, 92(1), 1–20. doi: 10.1111/padm.12040

- Kuipers, B. S., & Stoker, J. I. (2009). Development and performance of self-managing work teams: A theoretical and empirical examination. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(2), 399–419. doi: 10.1080/09585190802670797

- Laloux, F. (2014). Reinventing organizations: A guide to creating organizations inspired by the next stage in human consciousness. Brussels: Nelson Parker.

- Langfred, C. (2000). The paradox of self-management. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(6), 563–585. doi: 10.1002/1099-1379(200008)21:5<563::AID-JOB31>3.0.CO;2-H

- Lines, R. (2004). Influence of participation in strategic change: Resistance, organizational commitment and change goal achievement. Journal of Change Management, 4(3), 193–215. doi: 10.1080/1469701042000221696

- Manz, C. (1992). Self-leading work teams. Human Relations, 45(11), 1119–1140. doi: 10.1177/001872679204501101

- Manz, C., & Sims, H. (1987). Leading workers to lead themselves. Administrative Science Quarterly, 32, 106–128. doi: 10.2307/2392745

- Mohrman, S. A., Tenkasi, R. V., & Mohrman, A. M. (2000). Learning and knowledge management in team-based new product development organizations. Advances in Interdisciplinary Studies of Work Teams, 5, 63–88.

- Neil, R., Wagstaff, C. R., Weller, E., & Lewis, R. (2016). Leader behaviour, emotional intelligence, and team performance at a UK government executive agency during organizational change. Journal of Change Management, 16(2), 97–122. doi: 10.1080/14697017.2015.1134624

- Pettigrew, A. M. (1985). The awakening giant: Continuity and change at ICI. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Pettigrew, A. M. (1990). Longitudinal field research on change: Theory and practice. Organization Science, 1(3), 267–292. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1.3.267

- Pettigrew, A. M., Woodman, R. W., & Cameron, K. S. (2001). Studying organizational change and development: Challenges for future research. Academy of Management Journal, 44(4), 697–713. doi: 10.2307/3069411

- Procter, S., & Benders, J. (2014). Task-based voice. In A. Wilkinson, J. Donaghey, T. Dundon, & R. Freeman (Eds.), Handbook of research on employee voice (pp. 298–309). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Procter, S., & Currie, G. (2004). Target-based teamworking. Human Relations, 57(12), 1547–1572. doi: 10.1177/0018726704049989

- Procter, S., & Radnor, Z. (2014). Teamworking under lean in UK public services. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(21), 2978–2995. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2014.953976

- Procter, S., & Radnor, Z. (2017). Teamworking and Lean revisited: a reply to Carter et al. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(3), 468–480.

- Sanner, B. (2017). Learning after an ambiguous change: A grounded integration of framing and achievement goal theories. Journal of Change Management (online first). doi:10.1080/14697017.2017.1381637

- Seibert, S., Silver, S., & Randolph, W. (2004). Taking empowerment to the next level. Academy of Management Journal, 47(3), 332–349. doi: 10.2307/20159585

- Stewart, G. (2006). A meta-analytic review of relationships between team design features and team performance. Journal of Management, 32(1), 29–55. doi: 10.1177/0149206305277792

- Sullivan, W., Sullivan, R., & Buffton, B. (2001). Aligning individual and organisational values to support change. Journal of Change Management, 2(3), 247–254. doi: 10.1080/738552750

- Trist, E. (1981). The evolution of socio-technical systems (Occasional Paper 2).

- Van den Broek, D., Callaghan, G., & Thompson, P. (2004). Teams without teamwork? Economic and Industrial Democracy, 25(2), 197–218. doi: 10.1177/0143831X04042500

- Van der Voet, J., Groeneveld, S., & Kuipers, B. S. (2014). Talking the talk or walking the walk? The leadership of planned and emergent change in a public organization. Journal of Change Management, 14(2), 171–191. doi: 10.1080/14697017.2013.805160

- Van der Voet, J., Kuipers, B. S., & Groeneveld, S. (2016). Implementing change in public organizations: The relationship between leadership and affective commitment to change in a public sector context. Public Management Review, 18(6), 842–865. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2015.1045020

- Van der Voet, J., Steijn, B., & Kuipers, B. S. (2017). What’s in it for others? The relationship between prosocial motivation and commitment to change among youth care professionals. Public Management Review, 19(4), 443–462. doi: 10.1080/14719037.2016.1183699

- Van Eijnatten, F. M. (1993). The paradigm that changed the work place. Assen: Van Gorcum

- Whitehead, P. (2001). Team building and culture change: Well-trained and committed teams can successfully roll out culture change programmes. Journal of Change Management, 2(2), 184–192. doi: 10.1080/714042495