ABSTRACT

This study investigated how middle managers can facilitate change by affecting subordinates’ affective responses and attitudes towards a merger. We utilized leader-member exchange theory and appraisal theory to argue that employees who have a high quality exchange relationships with their supervising manager would be provided with more change information and opportunities for participation in the change, and, in turn, would have more positive affective perceptions of the change in terms of trust, cynicism, uncertainty and control, and subsequently be more open to the change. Multi-group analysis was applied to data of 326 employees of two health insurance companies that were involved in a merger. The findings largely supported the research model, suggesting that middle managers can facilitate change by developing high-quality relationships with their subordinates, and addressing employees’ affective perceptions of the change through change information and change participation. Our focus on the middle managers’ relationship with their employees offers theoretical and practical insights into the affective and attitudinal processes that occur during organizational change.

MAD statement

This study aims to Make a Difference by exploring how employees’ reactions to a planned organizational change can be influenced by their supervisor. This study emphasizes the importance of the work (exchange) relationship of middle managers and their subordinates. Employees who experienced a qualitatively better relationship felt better about the change because they were given more change information and opportunities to participate, and were more open to the change. So it seems that middle managers can have a vital role in the effective implementation of planned change.

In todays’ dynamic world, change is the only constant (Huang, Citation2012). Global competition, technical developments, economic crises, and changed legislation are some of the factors that have forced organizations to adapt their business processes in the past decade, although changes can also be initiated for less urgent reasons (By, Citation2020). As organizational change can have a substantial impact on the people working in the organization, it can evoke strong and affective responses that can be critical for employees’ change attitudes (Kiefer, Citation2005; Van Dam, Citation2018).

Owing to their proximity to and day-to-day collaboration with their subordinates, middle managers are considered key players in organizational change efforts, particularly for employees’ responses to such changes (Battilana & Casciaro, Citation2013; Giangreco & Peccei, Citation2005; Gjerde & Alvesson, Citation2020). As a link-pin between the strategic and operational level of the organization, middle managers often serve as important agents in the change process (Balogun, Citation2003; Huy, Citation2002). They are the ones who can involve their subordinates in the change, for instance by providing them with crucial information and opportunities for participation, and thus by increasing employees’ acceptance of the change (Allen et al., Citation2007; Van Dam et al., Citation2008).

Despite the crucial position of middle managers in organizational change, only a few researchers (e.g. Faupel & Süß, Citation2019; Furst & Cable, Citation2008; Gjerde & Alvesson, Citation2020; Huy, Citation2002; Rafferty et al., Citation2013) have studied the role of middle managers in affecting employees’ change responses. Most literatures have focused on top managers, and/or the leadership styles these managers should adopt when guiding their company through change (Faupel & Süß, Citation2019; Herold et al., Citation2008; Kotter, Citation1996; Oreg & Berson, Citation2011). Additionally, middle managers’ sensemaking (Balogun & Johnson, Citation2004; Teulier & Rouleau, Citation2013) and emotions (Smollan & Parry, Citation2011; Vince, Citation2006) during change have been a topic of research. However, there is still more we should know about the role that middle managers play in facilitating effective change process. Specifically, what other mechanisms do managers have to promote and support employees to successfully implement organizational changes? For example, can middle managers’ relationship with their subordinates shape employees’ change responses and the implementation of organizational changes? Answers to this critical question are important to better understand and guide change processes.

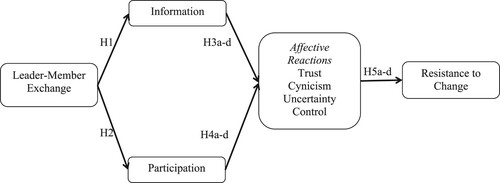

The goal of this study was to investigate how the exchange relationship middle managers have built with their employees relates to employees’ perceptions of the change implementation process, and consequently to their change responses. This study goes beyond existing research of change responses in several ways. First, instead of focusing on general leadership styles, this study takes employees’ perceptions of their daily relationships and interactions with their supervising middle manager. This is important because much of employees’ involvement in a change will happen at this dyadic, leader-subordinate level where the middle manager serves as a manager, coach, and change agent at the same time (McClellan, Citation2011). Second, we investigate the mechanisms that may explain these responses by applying Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) theory (Graen & Uhl Bien, Citation1995) and appraisal theory (Lazarus, Citation1991; Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984) as theoretical frameworks. Third, in line with appraisal theory, four affective change perceptions (trust, cynicism, uncertainty, and control) that convey a specific feeling toward or worry about the change and its consequences serve as outcomes of change involvement. These perceptions can be considered affective; while their positive poles trigger positive arousal and emotions that encourage employees to actively engage in the change process, the negative poles trigger and intensify negative arousal and emotions. As such, these perceptions affect how one feels and acts (Bar-Anan et al., Citation2009). Moreover, these affective perceptions likely relate to employees’ attitude towards the change. The research model is presented in .

Theoretical Background and Conceptual Framework

Appraisal Theory and LMX Theory

Planned organizational changes are generally considered sources of stress and uncertainties (Allen et al., Citation2007; Kiefer, Citation2005). In order to understand and minimize these negative consequences, organizational change research has started to focus on the role of employees’ change appraisals (Biggane et al., Citation2017; Fugate et al., Citation2012). According to appraisal theory, also known as the transactional theory of stress and coping (Lazarus & Folkman, Citation1984), individuals assess a stressful encounter to determine what it implies for them. As such, the announcement of a planned organizational change can start a series of appraisals that will be targeted at the change process as well as the outcome of the change (Liu & Perrewé, Citation2005; Rafferty & Restubog, Citation2017). Change appraisal is considered a fundamental cognitive process that represents an evaluation of a person-situation transaction in terms of its meaning for the individual and his/her position at work, resulting in affective and behavioural responses (Fugate, Citation2013). Whereas appraisal theory posits three types of appraisals (threat, harm and challenge), findings of change appraisal research indicate that individuals generally evaluate organizational change in a negative way, i.e. as a harm or a threat, which in turn has been related to decreased well-being and work enjoyment (Pahkin et al., Citation2014), increased negative affect (Fugate et al., Citation2011; Scheck & Kinicki, Citation2000) and withdrawal behaviour (Biggane et al., Citation2017; Fugate et al., Citation2012). Our study did not directly focus on harm, threat, or challenge appraisals but instead on the change perceptions underlying these appraisals. While trying to give meaning to the change situation, employees will develop specific affective perceptions of the change, such as (dis)trust or cynicism, that can affect how they will respond to the change. We call them affective perceptions because they entail a cognitive evaluation as well as an affective tone that can trigger and intensify negative arousal and emotions (Bar-Anan et al., Citation2009). Previous research has shown the relevance of affective change perceptions, such as (dis)trust (Oreg, Citation2006) and cynicism (Barton & Ambrosini, Citation2013) for employees’ change responses.

The appraisal process, and its outcomes, may be affected by the LMX relationship that middle managers hold with their subordinates. LMX theory (Graen & Scandura, Citation1987) states that managers develop unique relationships with each of their subordinates through an ongoing series of interpersonal exchanges. A high-quality LMX relationship has high levels of mutual support, trust, and loyalty, and behaviours that go beyond the employment contract. A low-quality LMX relationship is impersonal and transactional, grounded in contractual exchanges between both parties. Middle managers behave differently toward employees in high versus low LMX relationships by, for instance, more readily delegating authority, sharing information, setting challenging goals, and providing development opportunities to employees in high-quality LMX relationships (Dulebohn et al., Citation2012). In turn, and strengthening the exchange relationship, employees who experience high-quality LMX relationships respond positively; LMX is positively related to positive outcomes such as achievements, happiness, retention and openness to change (Gerstner & Day, Citation1997; Martin et al., Citation2016; Van Dam et al., Citation2008).

LMX Relationships, Change Information, and Change Participation

Middle managers may increase effective change implementation through the LMX relationships they maintain with their subordinates. A characteristic aspect of high-quality LMX relationships is the mutual sharing and provision of information, which in turn builds employee loyalty and trust (Graen & Uhl Bien, Citation1995). Information provision is particularly important in organizational change, because changes often imply a high degree of ambiguity and workers are not clear in which ways the change has consequences for themselves and the organization (Biggane et al., Citation2017; Oreg et al., Citation2011). Research findings indicate that change information that is accurate, timely, and useful can positively impact employees’ responses to the change (Biggane et al., Citation2017; Bordia et al., Citation2004; Oreg, Citation2006; Wanberg & Banas, Citation2000). As intermediates between the strategic and operational level, middle managers are in the position to pass down relevant, accurate and timely information about the change to their subordinates. Given the nature of the LMX relationship, managers will be more likely to provide such information to employees in high-LMX relationships than to those in low-LMX relationships (Graen & Uhl Bien, Citation1995). A previous study indeed observed that LMX was positively related to change information (Van Dam et al., Citation2008).

Hypothesis 1: LMX relates positively to change information.

Hypothesis 2: LMX relates positively to change participation.

Change Information, Change Participation, and Affective Change Perceptions

By involving their trusted subordinates in the change, through information and participation, middle managers can influence employees’ appraisal processes and, as such, their affective perceptions of the change (Cox et al., Citation2009; Rafferty et al., Citation2013 ). The current study focused on four affective change perceptions, i.e. trust, cynicism, uncertainty, and control. Whereas trust and cynicism involve affective perceptions that relate to others (i.e. change management), uncertainty and control relate to affective perceptions about the self and one’s position at work. These four change perceptions have shown relevance in previous change research (e.g. Oreg, Citation2006; Stanley et al., Citation2005) but have not been studied in this specific combination. Yet, these change appraisals are especially crucial because they affect how employees attend to and, subsequently, respond to the change (Fugate et al., Citation2011).

Trust refers to employees’ confidence that those responsible for the change are capable, and can be counted on to do what is best for the organization and its members (Kotter, Citation1996; Oreg, Citation2006). In the context of organizational change, information and participation are crucial aspects that can increases change related trust in management since both involve explanations of the rationale and intended outcome of the change, clarifications about how the change will proceed, and give employees a say in change implementation (Armenakis & Harris, Citation2013; Oreg et al., Citation2011). For instance, Oreg (Citation2006) found positive relationships of change information and change participation with employee trust.

Where trust involves beliefs about management’s abilities, change cynicism refers to a disbelief in management’s motives for the change (Stanley et al., Citation2005). Findings indicate that management can temper or prevent change cynicism by providing sufficient change information and opportunities for participation (Barton & Ambrosini, Citation2013; Brown & Cregan, Citation2008; Stanley et al., Citation2005). Conversely, cynicism increases when there is inadequate information about the change, and change participation is obstructed (Bommer et al., Citation2005).

Uncertainty about the future is rather common during organizational change. It is often difficult to imagine in advance what the future work situation of employees will look like after the change (Allen et al., Citation2007). Although uncertainty perceptions in change situations may be difficult to prevent, they can be reduced through change information and change participation (Allen et al., Citation2007; DiFonzo & Bordia, Citation1998). Organizations can lower employees’ experienced uncertainty by providing information about the objectives, process, and intended outcome of the change, including individuals’ job security and prospects, and by offering employees with opportunities for participation in the implementation of the change (Johnson et al., Citation1996).

Control, or employees’ perceptions of the influence over their personal work situation and career opportunities, might also be threatened in change situations (Kiefer, Citation2005; Schweiger & Denisi, Citation1991). Change information and change participation can enhance perceptions of personal control because it increases knowledge and predictability of events (Bordia et al., Citation2004; Johnson et al., Citation1996). Researchers (e.g. Bordia et al., Citation2004; Wanberg & Banas, Citation2000) observed positive associations of change information and change participation with control perceptions. Based on this theoretical and empirical evidence, we developed the next hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3: Change information relates positively to trust (H3a) and control (H3b), and negatively to cynicism (H3c) and uncertainty (H3d).

Hypothesis 4: Change participation relates positively to perceived trust (H4a) and control (H4b), and negatively to cynicism (H4c) and uncertainty (H4d).

Affective Change Perceptions and Change Attitudes

Employees’ affective perceptions of the change can, in turn, determine whether they are open to the change or resist it. Trust is widely considered a critical facilitator of organizational processes (Dirks & Ferrin, Citation2002), such as change. Employees with little faith in a change’s management effectiveness may alienate themselves from the change and ultimately resist it (Kotter, Citation1996). Research indicates that employees with high levels of trust in management are more open to change, and more willing to cooperate with the change, whereas employees with distrust resisted the change more (Oreg, Citation2006; Stanley et al., Citation2005).

Similarly, employees’ cynicism has been related to change resistance and low motivation to support change efforts (Stanley et al., Citation2005; Wanous et al., Citation2000). Additionally, change cynicism can have detrimental consequences for employee work attitudes, such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and work motivation (Wanous et al., Citation2000).

Uncertainty is generally considered an aversive state because it disables individuals to prepare for future actions (DiFonzo & Bordia, Citation1998). Employees appear to resist a change when perceived uncertainty is high (Allen et al., Citation2007; DiFonzo & Bordia, Citation1998; Schweiger & Denisi, Citation1991). Additionally, uncertainty during organizational change is associated with more stress, anxiety, and turnover intention and less job satisfaction, and organizational commitment (Allen et al., Citation2007).

Finally, control perceptions matter. Employees are likely to reject a change that threatens their personal control over their work situation and career opportunities, whereas they will be more open to a change that maintains their control. Wanberg and Banas (Citation2000) found that control perceptions were positively related to employees’ change acceptance. Control also relates negatively with employees’ symptoms of stress during a large-scale change (Bordia et al., Citation2004). Based on this theoretical and empirical evidence, we hypothesed the following:

Hypothesis 5: Trust (H5a) and control (H5b) relate negatively to resistance to change; cynicism (H5c) and uncertainty (H5d) relate positively to resistance to change.

Methods

Change Context, Procedure, and Participants

Participants were employed by two Dutch health insurance companies during an ongoing merger. New national legislation had made it easier for customers of insurance companies to end their contract with their insurer and switch to another insurer. For the two companies in this study, this might imply that they would loose customers and market share, and in the end might have to downsize and turnover employees. To prevent such a situation and strengthen their economic position, the two companies had decided to merge and enhance operational and financial efficiency. A new foundation was established, that would prepare and implement the merger, with the two directors as Board of Directors. Middle managers of both organizations were regularly invited to meetings to discuss the progress and implementation of the change, which was intended to be completed within a two-year period.

At the time of the study, the implementation of the merger had just begun and employees were facing changes in work procedures and management practices. Still, there were many insecurities. For example, it was not clear whether the new company would provide a uniform health insurance product, or whether the locations would remain the same. While the change would ultimately affect the job system, it was still too early to talk about the consequences for individual employees. Although all employees initially remained employed in the new, merged organization, the merger could potentially involve job losses further along, once the consequences of the merger and the new legislation would become apparent.

The two companies differed in size; company A employed about 2000 workers and company B employed about 560 workers. In company A, a random sample was drawn by the HR department, consisting of 20 percent (N = 396) of the employees by selecting every fifth employee of the list with employees; in company B, all 560 employees were asked to participate in the study. Employees received a questionnaire and a return envelope, which were sent to their home address. A cover letter explained the study objectives, and its anonymous and voluntary character. After two weeks, a reminder was sent to the potential participants of company A. Unfortunately, company B preferred that we do not send a reminder.

Three hundred and twenty-six questionnaires were returned, 163 (41.2% response rate) from company A and another 163 (29.1% response rate) from company B. Mean age was 40.6 years (SD = 9.0); mean organizational tenure was 12.3 years (SD = 8.8); 63 percent were female and 37 percent were male. Education included vocational training at middle level (58.9%), vocational training at higher level (31.3%), and university (9.8%).

Measures

A five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) was used for all scales, such that higher scores reflected higher values on the variable. McDonalds’ Omega (ω) was calculated as an indication of the internal consistency of the scales.

Leader-member exchange as perceived by the employee was assessed with Graen and Uhl Bien’s (Citation1995) seven-item LMX7 scale (ω = .94). An example item was ‘My working relationship with my leader is good’.

Change information was assessed with six items asking about the perceived timeliness, accuracy, and usefulness of the information about the merger (e.g. ‘The information I have received has adequately answered my questions about the change’; ω = .90) (Bordia et al., Citation2004; Oreg, Citation2006; Wanberg & Banas, Citation2000).

Change participation was assessed with a five-item scale (e.g. ‘I had the opportunity to participate in discussions about the change’; ω = .87) developed by Oreg (Citation2006), based on Wanberg and Banas (Citation2000).

Affective change perceptions were assessed as follows. Trust was measured with a five-item scale developed by Oreg (Citation2006) (e.g. ‘Overall, I have the feeling that the people who are leading this change can be trusted’; ω = .87). Cynicism was measured with five items (e.g. ‘I question management’s motives for this change’; ω = .84) of Stanley et al.’s (Citation2005) change-related cynicism scale. Employees’ perception of uncertainty was assessed with six items of Bordia et al.’s (Citation2004) uncertainty scale (e.g. ‘I am uncertain whether I will “fit” into the culture of the new organization’; ω = .81). To measure employees’ perceptions of control over their work situation, the three-item scale of Bordia et al. (Citation2004) (e.g. ‘I have the feeling that I have no control over my work situation’; ω = .87) was extended with two control items of Judge et al.’s (Citation2003) scale for core self-evaluations, which were adjusted to apply to a change situation.

Change resistance was assessed with Oreg’s (Citation2006) 15-item scale (e.g. ‘I express my objections regarding the change to management’; ω = .89).

Several demographic characteristics were assessed, i.e. age, gender, tenure, and education.

Data Analysis

A two-step procedure was used in data-analysis. As a first step, confirmatory factor analysis was applied to investigate the measurement model. Using the full sample, we started with the 8-factor model that represented the separate variables in our research model, and then systematically merged variables into combined factors. The correlations between the variables were used to decide which constructs to merge. In each step, we tested the new model against the 8-factor model that included all research variables. As shows, the 8-factor model represented the correlational structure of the data best (χ2 = 834 (df = 377); CFI = .93; TLI = .92; RMSEA = .061), indicating that the scales were distinct measures of the model variables.

Table 1. Results model comparisons with CFA to test measurement model.

In the next step, structural equation modelling (SEM) with maximum likelihood estimation on the manifest variables was used to examine the fit of the research model and test the hypotheses. As this study collected data in both organizations that were involved in the merger, it was decided to conduct a multi-group analysis. A multi-group analysis provides a more stringent test of the research model, investigating whether the proposed relationships hold in both data sets. We first tested the full model, which simultaneously included all of our hypotheses, using the full sample (see ). We then conducted a multi-group analysis. To test the measurement invariance between the two groups, and following the procedure proposed by Van de Schoot et al. (Citation2012), five hierarchical models were investigated: Model 1, the unconstrained model that tested configural invariance; Model 2, in which regression weights were constrained to be equal across the two groups; Model 3, in which regression weights and intercepts were constrained, testing for scalar invariance; Model 4, in which the covariances between the variables constrained in addition to the constraints of model 3; and Model 5, a fully constrained model in which, in addition to the other constraints, the residuals were also constrained to be equal across groups.

All SEM analyses were performed in R (R core Team, Citation2016), using the package Lavaan (Rosseel, Citation2012). Several fit indices were used to evaluate model fit: the Comparative-Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) 0; and the Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA) (Kline, Citation2005).

Results

presents the statistical characteristics of the study variables.

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, intercorrelations, and reliability estimates (Cronbach’s alpha).

Model Fit

When testing the model with all participants as one group, the model fitted the data well (χ2 = 27.20 (df = 7); CFI = .98; TLI = .93; RMSEA = .094). Using a multi-group analysis, we then tested the robustness of our model (see ). The fully constrained model (Model 5) fitted the data in both organizations well (χ2 = 122.68 (df = 51); CFI = .94; TLI = .93; RMSEA = .093), indicating that the model is robust across both organizations. The significant difference between Models 1, 2 and 3, however, suggests that there were nevertheless a few differences in regression weights and intercepts across the two groups. Whereas most regression weights were equal across groups, two regression paths, i.e. from information to control and uncertainty, were highly significant in one group (company B), but only marginally significant (p < .10) in the other group (company A). Overall, our findings suggest that the research model is robust over organizations, implying a cross-validation of the conceptual model. Consequently, we report the structural weights estimates (standardized coefficients) of the total-group analysis (see ).

Table 3. Outcomes multi-group analysis.

Table 4. Estimated regression coefficients(β) and explained variance for each variable from the structural model for the full sample.

Hypothesis Testing

Both Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2 were supported; LMX related positively to change information (β = .32, p < .001) and change participation (β = .28, p < .001).

Hypothesis 3 was largely supported. Within the full sample data, change information related significantly to trust (β = .56, p < .001), cynicism (β = −.52, p < .001), uncertainty (β = −.36, p < .001), and control (β = .26, p < .01). As noted previously, the multi-group analyses revealed some differences between companies. Whereas regression weights for the relationships of information with control and uncertainty were highly significant for company B (uncertainty: β = −.52, p < .001; control: β = .35, p < .001), they only showed a trend for company A (uncertainty: β = −.17, p = .058; control: β = .13, p = .095).

Hypothesis 4 was partly supported. While change participation related significantly to control (β = .34, p < .001), it was unrelated to trust (β = −.03, ns), cynicism (β = −.01, ns), and uncertainty (β = −.04, ns).

Finally, Hypothesis 5 was fully supported. Resistance to change was predicted by all four affective perceptions: trust (β = −.29, p < .001), cynicism (β = .20, p < .001), uncertainty (β = .28, p < .001), and control (β = −.09, p < .05).

The proportion of explained variance in the research variables was 12.8% (change information), 9.7% (change participation), 43.0% (trust), 31.0% (control), 41.6% (cynicism), 14.2% (uncertainty), and 57.6% (resistance to change).

Post-hoc Analyses for Indirect Effects

Given these outcomes, it was interesting to investigate whether there were indirect effects. Bootstrapping analysis was used to assess the indirect effects of information and participation on resistance, through the four affective change perceptions (Preacher & Hayes, Citation2008; Shrout & Bolger, Citation2002). In addition, Hayes’ (Citation2013) Process macro was applied to run mediation analyses. The outcomes of the bootstrap analysis indicated that the indirect effects of information on resistance to change via trust, uncertainty and cynicism are significant. The total indirect effect of information on change resistance is −.41; 95% Confidence Interval (CI) [−.49, −.33]. Only the indirect effect of information via control is small (−.03) and not significant; 95% CI [−.08, .00]. The other indirect effects with the 95% CIs were: −.17 [−.23, −.10] for trust, −.10 [−.17, −.04] for cynicism, and −.10 [−.15, −.07] for uncertainty. The direct effect of information on resistance (.01) is not significant; 95% CI [−.07, .10]. Finally, the total indirect effect of LMX on resistance, through information, participation, and the four affective perceptions, is −.20; 95% CI [−.28, −.13]. These findings are indicative of indirect processes for information but not for participation.

Discussion

Using LMX and appraisal theories as theoretical frameworks, this study focused on the role middle managers play for their subordinates’ responses to a substantial, top-down initiated organizational change. The findings supported our expectation that middle managers can facilitating change through the LMX relationship with their subordinates. Employees in a high-quality LMX relationship had received more change information and participation opportunities than those in a low-quality exchange relationship. Previous LMX research similarly suggests that high-LMX employees are better informed, more aware of organizational events, such as change, and experience the climate of the organization as more supportive for change (Graen & Uhl Bien, Citation1995; Kozlowski & Doherty, Citation1989; Van Dam et al., Citation2008).

In addition, and consistent with LMX theory, LMX was indirectly, through change information and change participation, associated with employees’ affective perceptions of the change. Employees who received more information about the change reported increased confidence in change managers’ ability to lead the change, were less cynical about the motives for the change, experienced less uncertainty regarding the future, and felt more in control of their personal work situation, compared to employees who had received less information. These outcomes support previous research that has shown the relevance of change information for change responses in general (Oreg et al., Citation2011; Teulier & Rouleau, Citation2013) and change appraisal in particular (Biggane et al., Citation2017), indicating that middle managers can affect change appraisal processes by providing their subordinates with timely and accurate information. The outcomes of the multi-group analysis revealed that some of the relationships (i.e. with uncertainty and control) were stronger for the smaller company than for the larger company. It is possible that the change was perceived differently in the two organizations with the employees of the smaller company viewing the reorganization the result of a takeover more than the outcome of a merger. In preparatory interviews, employees of the smaller company had mentioned that they expected to have to exchange their customary procedures and practices for those of the larger company. As such, these employees may have felt more threatened by the change and therefore needed the information about the change more than the employees of the larger company who were more likely to persist in their way of working after the change. As far as we know, there is no research yet that has addressed the impact of different types of change on employees’ need for information. Yet, in both the smaller and the larger company, change information was related to employees’ affective change perceptions.

The findings only partly supported the expected role of change participation. Employees who participated in the change reported feeling more in control, which supports notions in the change literature that change participation processes can install a sense of ownership and power over the change process (Armenakis & Harris, Citation2013; Oreg et al., Citation2011). Yet, participation did not predict the other affective perceptions. It is possible that the type of change in this study, a merger, might explain the low associations. As the low mean for participation in indicates, there was not much room for change participation, and although participation showed significant, albeit moderate correlations with the four affective change perceptions, the correlations for change information were stronger. This pattern of associations suggests that, in this specific merger, information may have been more important than participation for employees’ perceptions of trust, cynicism and uncertainty. Moreover, some other studies similarly failed to find significant relationships. For instance, Wanberg and Banas (Citation2000) noticed that change participation at Time 1 was unrelated to change acceptance at Time 2 (two months later). Similarly, leadership research has observed only modest effects of participation on outcomes such as motivation, satisfaction, and performance (Lam et al., Citation2002; Wagner, Citation1994). However, it is also possible that change participation has an effect on outcomes that were not included in this study (see Oreg et al., Citation2011).

Finally, all four affective change perceptions were related to employees’ attitude toward the merger. Employees reported more resistance when they had little confidence in change management’s ability and motives, felt more uncertain about the future, and experienced little control over their personal situation. By establishing the unique contribution of each affective perception in the prediction of change resistance, our study extends previous research that focused on only one or two of these perceptions at a time (Bordia et al., Citation2004; Schweiger & Denisi, Citation1991; Stanley et al., Citation2005). Moreover, the findings indicated that the four affective perceptions fully mediated the relationships of information with resistance to change. The mediating role of employees’ affective change perceptions has been studied by only a few researchers (e.g. Bordia et al., Citation2004; Fugate et al., Citation2011; Stanley et al., Citation2005). Bordia et al. (Citation2004) for instance found that perceptions of control and uncertainty mediated the relationships of information and participation with symptoms of strain. Stanley et al. (Citation2005) observed that information predicted cynicism and that cynicism predicted resistance; mediation was not investigated, however.

Limitations and Implications for Research

This study has several limitations. One limitation of our study concerns its concurrent design, which limits the possibility for causal inferences. Causal interpretation might be increased by using a longitudinal design with multiple waves, by applying an experimental design where information and participation are manipulated, or by using a quasi-experimental design with different companies or departments undergoing a change at different times. Another limitation concerns the use of only employees as a source of information, which could affect observed relationships. Future research could take into account ratings from peers and supervisors, or collect data in multiple waves (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). Moreover, our data were collected in a specific context, a merger between two health insurance firms in the Netherlands. As such, the generalizability of the current findings to other change contexts might be limited. We encourage future research to reexamine the study findings in other change contexts, branches and countries. Finally, we have no information about those who did not complete our questionnaire. Therefore, the outcomes should be interpreted with some caution. Also, the lower response rate for company B might indicate that the employees of company B were less well represented in this study, although 29 percent response is still substantial for change research, and the outcomes for both companies showed great similarity.

Despite these limitations, we believe that our findings have meaningful implications for research and practice regarding top-down implemented organizational change. Whereas evidence of the strategic role of the middle manager during change is accumulating, there is still need to further explore the mechanisms explaining how middle managers exert their strategic influence. The present study tried to open this ‘black box’ by studying the role of middle managers for employees’ change responses, using LMX and appraisal theory as frameworks for explaining some of these mechanisms. Our findings indicate that middle managers, through daily interactions, can influence how employees perceive the change and respond to it. In other words, middle managers can serve as change agents who facilitate the acceptance of change through the LMX relationship they have developed with their subordinates. Besides the LMX relationship, other middle manager characteristics, such as adaptability or strategic position, as well as different social exchange processes, such as team-member exchange, may affect employees’ change appraisal and openness to change. New research is needed to investigate how these factors relate to appraisals, perceptions and responses to organizational change.

In line with appraisal theory, this study highlights the role of change information for employees’ affective perceptions of planned change. High-quality information about the change was strongly related to employees’ confidence in management as indicated by high trust and low cynicism, and to perceptions of uncertainty and control. These four affective responses appeared to fully mediate the effect of change information on employees’ attitudes towards the change. As such, our findings provide an explanation for the impact of change information on change attitudes that has been observed by other researchers (e.g. Allen et al., Citation2007; Oreg, Citation2006; Schweiger & Denisi, Citation1991). Apparently, the extent to which change information is provided and dialog opportunities are created, affect how employees appraise the change, and whether they are open to it. Organizations tend to cut back on information when management expects the change to have a negative impact on employees (Richardson & Denton, Citation1996). Employees often consider any information (even negative information) as more helpful than no information (Johnson et al., Citation1996), which might be due to the role information plays in the change appraisal process. Indeed, our findings for the smaller company suggest that change information is crucial especially when the change might be perceived as a threat (see also Biggane et al., Citation2017; Fugate et al., Citation2011, Citation2012). To substantiate this suggestion, future research could investigate whether employees’ appraisal of the change in terms of a threat or a challenge, moderates the influence of change information and change participation on employees’ responses to a change.

Together, the findings indicate that planned organizational change can serve as an affective event that triggers an assessment process and results in different affective perceptions, which affect employees’ attitude towards the change. Overall, it appears that employees’ responses to change are complex and involve different perceptions and worries. Researchers are increasingly paying attention to employees’ affective responses to change, and to the different ways they deal with these responses and adapt to the change (e.g. Fugate et al., Citation2011; Rafferty & Restubog, Citation2017; Van Dam & Meulders, Citation2020). Future research could more explicitly study which discrete emotions occur (Kiefer, Citation2005), and how these emotions relate to change appraisals, and to aspects of the work situation, such as middle manager characteristics. Moreover, employee characteristics, such as adaptability, trait affectivity, and experiences with prior changes, might play a role in the change appraisal process (Van Dam, Citation2018).

Practical Implications

Relatedly, our study has important practical implications. Our findings emphasize that middle managers should be aware that they can facilitate planned organizational change through building supportive and high-quality exchange relationships with their subordinates, involving employees in the change, and addressing their worries about the process and outcomes of the change, all of which may affect employees’ change appraisal. Moreover, middle managers should be aware of their tendency to treat employees differently, which can affect subordinates’ perceptions of and responses to organizational change efforts. Additionally, middle managers, HRM professionals and general management alike need to be aware that high-quality information and participation programmes are crucial for employees’ change responses (cf Cox et al., Citation2009). Especially when a change has important (negative) outcomes, it is important that all parties communicate extensively about the change in order to affect change appraisals and prevent a possible decline in employees’ confidence in management. Finally, our findings indicate that employees’ appraisal of the change can result in a number of affective change perceptions that might be important for their acceptance of the change. Middle managers should be aware of these perceptions and take them seriously (Kiefer, Citation2005). Insufficient attention to employees’ affective responses can undermine the effectiveness of the change programme (Kotter, Citation1996) and might additionally affect other organizational outcomes such as job performance, turnover, well-being, and absenteeism (Wanberg & Banas, Citation2000).

Given increased organizational dynamics with rapid changes and innovations, it is of crucial importance that middle managers are competent for change management. In addition to being more aware of their crucial role for change effectiveness, middle managers can be trained to further develop their ability to manage change. In the literature, several recommendations can be found for improving middle managers’ competencies for providing leadership during changing and dynamic work situations. Zaccaro and Banks (Citation2004), for instance, describe an extensive training programme consisting of different HRM programmes for developing change managers abilities. As this programme emphasizes. management development should focus on the wider organizational context and pay attention to the daily reality of continuous organizational change.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on the contributors

Karen van Dam is a professor in Work and Organizational Psychology at the Open University of the Netherlands. She received her Ph.D from the University of Amsterdam and has taught across the full spectrum of Organizational Behavior and Human Resource Management topics. Her research focuses on how employees adapt to changes at and demands from work; including individual adaptability, resistance, emotion regulation, appraisal processes, and coping with stress. She has published in e.g. Journal of Applied Psychology, Journal of Management, Journal of Vocational Behavior, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, and Personality and Individual Differences. Email: [email protected].

Peter Verboon is an associate professor and chair of the department of Methods & Statistics at the Faculty of Psychology of the Open University of the Netherlands. He received his Ph.D. at the University of Leiden, and worked as a methodologist at the Dutch Bureau of Statistics and the Ministry of Finance, before joining the Open University. His research interests include a large range of data analysis procedures, such as nonlinear multivariate analysis, single case designs and ESM designs. He has published in e.g. Psychometrika, Journal of Economic Psychology, European Journal of Social Psychology, British Journal of Psychology, and Journal of Child and Family Studies. Email: [email protected].

Amanuel Tekleab is a professor of Management, Entrepreneurship and Innovation, at Wayne State University, USA. Starting his education at Addis Ababa University in Ethiopia, he subsequently obtained his doctoral (Ph.D) degree at College Park, the University of Maryland. He is the current Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Managerial Psychology. In teaching and research, he focuses on organizational change, leadership, team processes, justice, and the psychological contract. He has published in e.g. Academy of Management Journal, Journal of Organizational Behavior, Organization and Management Journal, Group and Organization Management and Journal of Business Research. Email: [email protected].

References

- Allen, J., Jimmieson, N. L., Bordia, P., & Irmer, B. E. (2007). Uncertainty during organizational change: Managing perceptions through communication. Journal of Change Management, 7(2), 187–210. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14697010701563379

- Armenakis, A. A., & Harris, S. G. (2013). Reflections: Our journey in organizational change research and practice. Journal of Change Management, 9(2), 127–142. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14697010902879079

- Balogun, J. (2003). From blaming the middle to harnessing its potential: Creating change intermediaries. British Journal of Management, 14(1), 69–83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00266

- Balogun, J., & Johnson, G. (2004). Organizational restructuring and middle manager sensemaking. Academy of Management Journal, 47(4), 523–549. https://doi.org/10.5465/20159600

- Bar-Anan, Y., Wilson, T. D., & Gilbert, D. T. (2009). The feeling of uncertainty intensifies affective reactions. Emotion, 9(1), 123–127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014607

- Barton, L. C., & Ambrosini, V. (2013). The moderating effect of organizational change cynicism on middle manager strategy commitment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(4), 721–746. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.697481

- Battilana, J., & Casciaro, T. (2013). Overcoming resistance to organizational change: Strong ties and affective cooptation. Management Science, 59(4), 819–836. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1120.1583

- Bezuijen, X., Van Dam, K., Van den Berg, P. T., & Thierry, H. (2010). How leaders stimulate employee learning: A leader-member exchange approach. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(3), 673–693. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909X468099

- Biggane, J. E., Allen, D. G., Amis, J., Fugate, M., & Steinbauer, R. (2017). Cognitive appraisal as a mechanism linking negative organizational shocks and intentions to leave. Journal of Change Management, 17(3), 203–227. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2016.1219379

- Bommer, W. H., Rich, G. A., & Rubin, R. S. (2005). Changing attitudes about change: Longitudinal effects of transformational leader behavior on employee cynicism about organizational change. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(7), 733–753. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.342

- Bordia, P., Hunt, E., Paulsen, N., Tourish, D., & DiFonzo, N. (2004). Uncertainty during organizational change: Is it all about control? European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 13(3), 345–365. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320444000128

- Brown, M., & Cregan, C. (2008). Organizational change cynicism: The role of employee involvement. Human Resource Management, 47(4), 667–686. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20239

- By, R. T. (2020). Editorial: Organizational change and leadership: Out of the quagmire. Journal of Change Management, 20(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2020.1716459

- Cox, A., Marchington, M., & Suter, J. (2009). Employee involvement and participation: Developing the concept of institutional embeddedness using WERS2004. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(10), 2150–2168. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190903178104

- DiFonzo, N., & Bordia, P. (1998). A tale of two corporations: Managing uncertainty during organizational change. Human Resource Management, 37(3-4), 295–303. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-050X(199823/24)37:3/4<295::AID-HRM10>3.0.CO;2-3

- Dirks, K. T., & Ferrin, D. L. (2002). Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 611–628. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.611

- Dulebohn, J. H., Bommer, W. H., Liden, R. C., Brouer, R. L., & Ferris, G. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of antecedents and consequences of Leader-Member Exchange: Integrating the past with an eye toward the future. Journal of Management, 38(6), 1715–1759. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311415280

- Faupel, S., & Süß, S. (2019). The effect of transformational leadership on employees during organizational change: An empirical analysis. Journal of Change Management, 19(3), 145–166. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2018.1447006

- Fugate, M. (2013). Capturing the positive experience of change: Antecedents, processes, and consequences. In S. Oreg, A. Michel, & R. T. By (Eds.), The psychology of organizational change (pp. 15–39). Cambridge University Press.

- Fugate, M., Harrison, S., & Kinicki, A. J. (2011). Thoughts and feelings about organizational change: A field test of appraisal theory. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 18(4), 421–437. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051811416510

- Fugate, M., Prussia, G. E., & Kinicki, A. J. (2012). Managing employee withdrawal during organizational change: The role of threat appraisal. Journal of Management, 38(3), 890–914. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309352881

- Furst, S. A., & Cable, D. M. (2008). Employee resistance to organizational change: Managerial influence tactics and leader-member exchange. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(2), 453–462. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.453

- Gerstner, C. R., & Day, D. V. (1997). Meta-analytic review of leader-member exchange theory: Correlates and construct issues. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(6), 827–844. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.82.6.827

- Giangreco, A., & Peccei, R. (2005). The nature and antecedents of middle managers resistance to change: Evidence from an Italian context. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16(10), 1812–1829. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190500298404

- Gjerde, S., & Alvesson, M. (2020). Sandwiched: Exploring role and identity of middle managers in the genuine middle. Human Relations, 73(1), 124–151. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718823243

- Graen, G. B., & Scandura, T. A.. (1987). Toward a psychology of dyadic organizing. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 9, pp. 175–208). JAI Press.

- Graen, G. B., & Uhl Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory over 25 years; applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219–247. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/1048-9843(95)90036-5

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to moderation, mediation and conditional process analysis. Guilford Press.

- Herold, D. M., Fedor, D. B., Caldwell, S. D., & Liu, Y. (2008). The effects of transformational leadership on employees’ commitment to a change: A multilevel study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(2), 346–357. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.346

- Huang, C. A. (2012). Taiji/yinyang philosophy. TedxHendrixCollege. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8TSEnoAa39s

- Huy, Q. N. (2002). Emotional balancing of organizational continuity and radical change: The contribution of middle managers. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47(1), 31–69. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3094890

- Johnson, J. R., Bernhagen, M. J., Miller, V., & Allen, M. (1996). The role of communication in managing reductions in work force. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 24(3), 139–164. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00909889609365448

- Judge, T. A., Erez, A., Bono, J. E., & Thoresen, C. J. (2003). The core self-evaluation scale: Development of a measure. Personnel Psychology, 56(2), 303–331. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2003.tb00152.x

- Kiefer, T. (2005). Feeling bad: Antecedents and consequences of negative emotions in ongoing change. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(8), 875–897. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.339

- Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practices of structural equations modeling. Guildford.

- Kotter, J. P. (1996). Leading change. Harvard: Harvard Business School Press.

- Kozlowski, S. W. J., & Doherty, M. L. (1989). Integration of climate and leadership: Examination of a neglected issue. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(4), 546–553. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.74.4.546

- Lam, S. S. K., Chen, X.-P., & Schaubroeck, J. (2002). Participative decision making and employee performance in different cultures: The moderating effects of allocentrism and efficacy. Academy of Management Journal, 45(5), 904–914. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069321

- Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. American Psychologist, 46(8), 819–834. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.46.8.819

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. Springer.

- Liu, Y., & Perrewé, P. L. (2005). Another look at the role of emotion in the organizational change: A process model. Human Resource Management Review, 15(4), 263–280. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2005.12.001

- Martin, R., Guillaume, Y., Thomas, G., Lee, A., & Epitropaki, O. (2016). Leader-Member exchange (LMX) and performance: A meta-analytic review. Personnel Psychology, 69(1), 67–121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12100

- McClellan, J. (2011). Reconsidering communication and the discursive politics of organizational change. Journal of Change Management, 11(4), 465–480. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2011.630508

- Oreg, S. (2006). Personality, context and resistance to organizational change. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 15(1), 73–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320500451247

- Oreg, S., & Berson, Y. (2011). Leadership and employees’ reactions to change: The role of leaders’ personal attributes and transformational leadership style. Personnel Psychology, 64(3), 627–659. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01221.x

- Oreg, S., Vakola, M., & Armenakis, A. A. (2011). Change recipients’ reactions to organizational change: A 60-year review of quantitative studies. Journal of Behavioral Science, 47(4), 461–524. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886310396550

- Pahkin, K., Nielsen, K., Väänänen, A., Mattila-Holappa, P., Leppänen, A., & Koskinen, A. (2014). Importance of change appraisal for employee well-being during organizational restructuring: Findings from the Finnish paper industry’s extensive transition. Industrial Health, 52(5), 445–455. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2014-0044

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

- Rafferty, A. E., Jimmieson, N. L., & Restubog, S. L. D. (2013). When leadership meets organizational change: The influence of top management teams and supervisory leaders on change appraisal, change attitudes, and adjustment to change. In S. Oreg, A. Michel, & R. T. By (Eds.), The psychology of organizational change: Viewing change from the employee's perspective (pp. 145–172). Cambridge University Press.

- Rafferty, A. E., & Restubog, S. L. D. (2017). The impact of change process and context on change reactions and turnover during a merger. Journal of Management, 36(5), 1309–1338. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309341480

- R Core Team. (2016). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

- Richardson, P., & Denton, D. K. (1996). Communicating change. Human Resource Management, 35(2), 203–216. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-050X(199622)35:2<203::AID-HRM4>3.0.CO;2-1

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

- Scheck, C. L., & Kinicki, A. J. (2000). Identifying the antecedents of coping with an organizational acquisition: A structural assessment. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(6), 627–648. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1379(200009)21:6<627::AID-JOB43>3.0.CO;2-D

- Schweiger, D. M., & Denisi, A. S. S. (1991). Communication with employees following a merger: A longitudinal field experiment. Academy of Management Journal, 34(1), 110–135. https://doi.org/10.2307/256304

- Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422

- Smollan, R., & Parry, K. (2011). Follower perceptions of the emotional intelligence of change leaders: A qualitative study. Leadership, 7(4), 435–462. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715011416890

- Stanley, D. J., Meyer, J. P., & Topolnytsky, L. (2005). Employee cynicism and resistance to organizational change. Journal of Business and Psychology, 19(4), 429–459. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-005-4518-2

- Teulier, R., & Rouleau, L. (2013). Middle managers’ sensemaking and interorganizational change initiation: Translation spaces and editing practices. Journal of Change Management, 13(3), 308–337. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2013.822674

- Van Dam, K. (2018). Feelings about change: The role of emotions and emotion regulation for employee adaptation to organizational change. In M. Vakola, & P. Petrou (Eds.), The psychology of organizational change (pp. 67–77). Routledge-Taylor & Francis Group.

- Van Dam, K., & Meulders, M. (2020). The adaptability scale: Development, internal consistency, and initial validity evidence. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000591

- Van Dam, K., Oreg, S., & Schyns, B. (2008). Daily work contexts and resistance to organizational change: The role of leader-member exchange, development climate, and change process characteristics. Applied Psychology, 57(2), 313–334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00311.x

- Van de Schoot, R., Lugtig, P., & Hox, J. (2012). A checklist for testing measurement invariance. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9(4), 486–492. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2012.686740

- Vince, R. (2006). Being taken over: Managers’ emotions and rationalizations during a company takeover. Journal of Management Studies, 43(2), 343–365. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00593.x

- Wagner, J. A. (1994). Participation’s effect on performance and satisfaction: A reconsideration of research evidence. Academy of Management Review, 19(2), 312–330. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1994.9410210753

- Wanberg, C. R., & Banas, J. T. (2000). Predictors and outcomes of openness to changes in a reorganizing workplace. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(1), 132–142. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.1.132

- Wanous, J. P., Reichers, A. E., & Austin, J. T. (2000). Cynicism about organizational change: Measurement, antecedents, and correlates. Group and Organization Management, 25(2), 132–153. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601100252003

- Zaccaro, S. J., & Banks, D. (2004). Leader visioning and adaptability: Bridging the gap between research and practice on developing the ability to manage change. Human Resource Management, 43(4), 367–380. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20030