ABSTRACT

This study draws upon conservation of resources theory to investigate if laissez-faire leadership influences employees’ perceptions of role clarity, and two forms of well-being (job satisfaction and work-related burnout), in the context of organizational restructuring. Moreover, role clarity is studied as a mechanism linking laissez-faire leadership to employee well-being. These relationships were tested using a three-wave time-lagged investigation conducted over a two-year period with a sample of 601 employees working in the Swedish process industry. The results of the structural equation modelling analyses showed that laissez-faire leadership was negatively related to role clarity 9 months later. In turn, role clarity mediated the relationship between laissez-faire leadership and employee well-being. This study contributes to the understanding of how laissez-faire leadership in the context of organizational restructuring may affect employee outcomes. We discuss implications for theories and practices, as well as directions for future research.

MAD statement

The majority of research on leadership during organizational restructuring has focused on positive outcomes of constructive forms of change leadership. However, other forms of leadership, such as laissez-faire leadership, may also play a crucial role for employee outcomes when implementing change. This study is to our knowledge the first to focus on the relationship between laissez-faire leadership and employee well-being in the context of organizational restructuring. We suggest that organizations work actively to include knowledge on this form of leadership in change-leadership training. We also suggest monitoring work-groups’ perceptions of role clarity (as a mechanism directly affected by laissez-fair leadership) during restructuring so that measures can be taken to facilitate transitions when needed.

Leadership is a social and goal-oriented influence process, which involve all individuals striving for a common objective (i.e. not merely limited to actions by a small number of individuals in a managerial role; Yukl, Citation2006). Although leadership is a collective phenomenon, in certain times and contexts, someone may own greater influence on someone else, than vice versa (Fischer et al., Citation2017). In the context of organizational restructuring managers often have a designated mandate and delegated responsibility to lead implementation of changes, especially in hierarchal organizations (Balogun, Citation2007). During such change initiatives, it has, therefore, been proposed that specifically the influence of managers’ leadership behaviours is of interest to examine (Battilana et al., Citation2010).

The insecurity and turbulence caused by organizational restructuring can be sources of considerable stress for employees and can therefore affect employee well-being negatively (de Jong et al., Citation2016). To counteract the strain caused by the restructuring, managers’ leadership behaviours may therefore be of significant importance to facilitate transitions (Day et al., Citation2017). Consequently, managers’ leadership behaviours have repeatedly been identified as a vital resource in successfully implementing changes in the workplace, and for reducing the negative effects that these changes may have on employee well-being (e.g. Day et al., Citation2017; Farahnak et al., Citation2020). For example, managers’ may actively empower employees to engage in the change process, lend them support in solving problems and remove obstacles, that will help them adapt to the new roles and tasks (Stouten et al., Citation2018).

However, beyond such active leadership behaviours (i.e. involvement), their leadership can also be characterized as passive (i.e. laissez-faire leadership behaviours, characterized by non-involvement or non-responsiveness when perceived as needed by employees; Skogstad et al., Citation2007). Conversely to active leadership behaviours, managers’ passive leadership behaviours, have been suggested to have opposite (i.e. adverse) effects (Neves & Schyns, Citation2018; Otto et al., Citation2018). These suggestions are based on findings from recent studies where managers’ laissez-faire leadership is depicted as a root cause of employee stress (Skogstad, Hetland, et al., Citation2014).

At the same time, alternative views on what outcomes managers’ laissez-faire leadership behaviours may produce can also be found in the leadership and organizational change management literature. Yang (Citation2015) suggested that laissez-faire leadership might be seen as a strategy to respect and give room for others competence in a certain situation. Similarly, a leader’s ability not to intervene (i.e. their negative capability), has been suggested as potentially important during uncertain circumstances (Simpson et al., Citation2002). From this perspective leaders ability to ‘back-off’ can help create a space in which new ideas and engagement from all others involved can be evoked (Simpson et al., Citation2002; Yang, Citation2015). Thus, laissez-faire leadership is here viewed as a prerequisite for positive employee outcomes.

Despite its suggested importance for employee outcomes laissez-faire leadership behaviours have received surprisingly little attention in empirical studies, both in general (Robert & Vandenberghe, Citation2020), and in conjunction with uncertain circumstances, such as restructuring (de Jong et al., Citation2016; Neves & Schyns, Citation2018). Qualitative studies have described managers’ tendencies to act avoidant (e.g. by actively withdrawing to their office and staying out of sight) as unhelpful leadership behaviours for implementing changes in a healthy way (Saksvik et al., Citation2007). Still, little is known about how such laissez-faire leadership behaviours affect employee outcomes in the context of organizational restructuring (Lundmark, Nielsen, et al., Citation2020; Otto et al., Citation2018). Thus, the aim of the present study is to longitudinally examine the relationships among managers’ laissez-faire leadership, employee role clarity, and job satisfaction and work-related burnout (i.e. employee well-being) during an organizational restructuring initiative.

Role clarity can be viewed as a desired proximal change outcome because transformed or expanded work roles often are a direct consequence of changes in a task or mission (Saksvik et al., Citation2007). As a workplace factor, role clarity can also be seen as an intermediate outcome to employee well-being because it may reduce the strain caused by the uncertainty that organizational change often encompasses (Vullinghs et al., Citation2018). We will therefore examine both direct relationships between managers’ laissez-faire leadership and the three outcomes (i.e. role clarity, job satisfaction and work-related burnout), as well as the indirect relationships among managers’ laissez-faire leadership, employee job satisfaction, and work-related burnout, mediated by role clarity. For this purpose, employee self-report data retrieved at three time points in conjunction with a planned organizational restructure at a Swedish process industry site will be analysed.

This study contributes to the change management literature by, to our knowledge, being the first to examine the influence of managers’ laissez-faire leadership on employee wellbeing outcomes during an organizational restructuring initiative. The debate on circumstances in which these behaviours may play a more profound role (Yang, Citation2015), and recent findings of the potentially strong influence of laissez-fair leadership on employee outcomes in times of change (Bligh et al., Citation2018), has led to calls to study this form of leadership in different change contexts (Neves & Schyns, Citation2018). Otto et al. (Citation2018) from a resource perspective, suggested that as organizational restructuring in itself may be a stressful event, and not having the support of a constructive leadership may further add to employee stress. In the present study, we build upon these findings and suggestions and add to the understanding of how, why and under which circumstances, laissez-faire leadership may affect employee well-being.

Additionally, the present study also contributes to the leadership literature in general by answering calls to perform prospective longitudinal studies examining the relationship between laissez-faire leadership, role clarity and employee wellbeing outcomes (Barling & Frone, Citation2017; Vullinghs et al., Citation2018). So far, existing studies examining these relationships have used a cross-sectional design, which impairs the possibility to draw strong conclusions.

Organizational Restructuring from a Resource Perspective

Organizational restructuring is a common form of organizational change that is driven by strategic considerations to adopt new structures in response to, for example, a perceived changed environment, or a need to improve performance (Balogun, Citation2007). To become effective, an organizational restructure have to be put in practice by members of the organization. In other words, beyond changes to an organizational chart, restructuring involves making changes to the way people work (de Jong et al., Citation2016). Several reviews have concluded that organizational restructures increase work-related demands and thereby poses a threat to employees’ work-related well-being (Bamberger et al., Citation2012; de Jong et al., Citation2016; Quinlan & Bohle, Citation2009; Westgaard & Winkel, Citation2011). Here, work-related well-being is viewed as a broad concept that, besides psychological and physical symptoms, also encompasses generalized job-related experiences such as job satisfaction (Danna & Griffin, Citation1999).

Conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, Citation1989) has been suggested as a theoretical framework to help understand how employees’ well-being is affected during organizational restructuring (Dubois et al., Citation2014; Lundmark, Nordin, et al., Citation2020; Neves & Schyns, Citation2018). According to COR theory, employees strive to obtain, foster, and protect valued resources, and conversely, they try to minimize the loss of these resources. The resources at work include object resources (e.g. tools for work), personal resources (e.g. skills), conditional resources (e.g. social support), and energy resources (e.g. money). When employees experience valued resources being threatened, lost, or impossible to regain/replace after investing effort, they will experience stress.

The depletion of valued resources in one domain (e.g. support as a conditional resource) also increases the chances of loss of resources in other domains because employees will seek to compensate for the loss, creating a loss spiral (Hobfoll et al., Citation2018). From an organizational restructure perspective, employees may perceive such change initiatives as a threat to, or an actual loss of, resources because they, for example, may have to develop new skills and relationships when changes to work tasks and teams are introduced. If possibilities (i.e. resources) to reduce or tackle these added demands are lacking or limited, then employees risk being resource depleted and, as a consequence, will experience stress followed by reduced well-being (Dubois et al., Citation2014; Hobfoll et al., Citation2018).

Managers’ constructive leadership behaviours (i.e. actively influencing employees by supporting and enhancing the tasks and strategy of the organization, as well as the motivation and wellbeing their followers; Skogstad, Aasland, et al., Citation2014) may constitute a resource for employees that can mitigate some negative outcomes of restructuring (Day et al., Citation2017). For example, in a study by Rafferty and Griffin (Citation2006), employees who reported high supportive managerial leadership during the change – process experienced less psychological uncertainty. Similarly, in a qualitative study by Smollan (Citation2015), employees who experienced a high degree of support from their managers during the change process reported less strain than those experiencing a lack of support from their manager. However, beyond what is depicted as lack of support from managers, managers’ laissez-faire leadership behaviours has been suggested as an added strain that increases the risk of undesired outcomes in an organizational restructuring context (Neves & Schyns, Citation2018).

Managers’ Laissez-faire Leadership – a Threat to Employee Wellbeing During Restructuring

Managers’ laissez-faire leadership is commonly operationalized as avoiding taking decisions and not being present when needed (Skogstad et al., Citation2007). From an employee perspective, this includes perceptions of a manager abdicating from responsibilities and authority associated with the managerial role, ignoring work-related problems, and not attending to employee needs (Robert & Vandenberghe, Citation2020; Skogstad, Aasland, et al., Citation2014).

Yang (Citation2015) suggested that laissez-faire leadership alternatively can be seen as a non-involvement strategy. From this perspective, managers’ laissez-faire leadership should not be discarded as always inappropriate. Yang (Citation2015) suggested that laissez-faire leadership may even have positive effects on employee outcomes as it may result in lower dependency, and in turn higher self-determination and autonomous motivation among employees. However, whether laissez-faire leadership behaviours should be considered effective is highly dependent on context, for example in situations where employees experience a high level of competence and capability (Yang, Citation2015). Additionally, employee expectations also seem to matter. Wong and Giessner (Citation2018) in a field study of 150 manager-employee dyads found that even though a manager may withdraw their involvement with the ambition to empower employees; this may not be perceived as empowering from an employee perspective. Thus, if managers’ non-involvement with intentions to empower is not aligned with employee expectations, employees will view them as being laissez-faire in a negative (i.e. avoidant when needed) sense (Wong & Giessner, Citation2018).

Based on the above we suggest that organizational restructuring is a critical event during which employees may experience as a threat to their resources (e.g. in terms of competence) and therefore expect a constructive leadership from their manager. Hence, it can also be expected that managers’ laissez-faire leadership (independent of strategic intentions) will have a negative influence on employee outcomes. For example, managers’ laissez-faire leadership may stand in the way of receiving expected vital information, active guidance, and social support needed to perform job tasks satisfactorily (Robinson et al., Citation2013).

So far, laissez-faire leadership has not been studied in the context of organizational restructuring. However, Bligh et al. (Citation2018) studied the influence of managers’ leadership style (i.e. transformational, transactional, laissez-faire, and aversive leadership) on error learning (as an important aspect of change implementation). The results showed that laissez-faire leadership had the strongest (i.e. negative) relationship with error-learning orientation among employees. Based on these results, we find it reasonable to suggest that in the context of restructuring, which in itself has been found a stressful event for employees (e.g. de Jong et al., Citation2016), laissez-faire leadership will be associated with negative employee outcomes.

Impaired Role Clarity – a Proximal Outcome of Managers’ Laissez-faire Leadership

An often important mission for managers’ during organizational restructuring is to facilitate employee transitions into new roles and work tasks (Saksvik et al., Citation2007). The ways in which managers can smoothen these transitions for employees through their leadership are therefore intimately connected to employees’ experience of role clarity (Bliese & Castro, Citation2000). Thus, managers clarifying what is expected of employees can be seen as a prerequisite to employees adapting to new or modified roles and to relieving the strain imposed by the imposed changes (Barling & Frone, Citation2017). Conversely, managers performing laissez-faire leadership per definition avoid helping and guiding employees, which implies that they do not facilitate role clarity (Skogstad, Hetland, et al., Citation2014). In other words, employees may fail to gain a needed resource from managers who act in a laissez-faire manner (Vullinghs et al., Citation2018).

Instead, employees’ role experience can be affected negatively when a manager disregards employees’ needs and expectations by withdrawing, not helping to solve problems, not providing feedback, and so on (Skogstad et al., Citation2007). Thus, managers leave employees in uncertainty by not establishing what should be done, and thereby, employees are less likely to adopt new routines (Barling & Frone, Citation2017), as, for example, suggested by restructuring plans. In the leadership literature, laissez-faire leadership has repeatedly been depicted as an antecedent to employees’ perceptions of role clarity, or the opposite – role ambiguity (Barling & Frone, Citation2017; Skogstad et al., Citation2007; Skogstad, Hetland, et al., Citation2014; Vullinghs et al., Citation2018). In line with these results, we hypothesize that the following:

H1: In the context of organizational restructuring, managers’ laissez-faire leadership will be negatively associated with employees’ role clarity over time (i.e. between baseline and 9-month follow-up).

Impaired Job Satisfaction and Work-related Burnout – Employee Well-being Outcomes of Managers’ Laissez-faire Leadership

If organizational restructuring poses an initial threat to resources, then continued loss or threat to employee resources may, as argued above, be a result of a laissez-faire leadership response from managers when in need of support and guidance. This may cause a continued loss spiral, which may lead to resource depletion and thereupon diminished job satisfaction and work-related burnout (Dubois et al., Citation2014; Halbesleben et al., Citation2013; Hobfoll et al., Citation2018). Job satisfaction (i.e. the overall evaluative judgment about one’s job; Judge et al., Citation2017) is perhaps the most studied employee well-being outcome in the context of organizational restructuring (for a compilation, see de Jong et al., Citation2016). Results from these studies show that deteriorated employee job satisfaction is a common result of restructuring. In turn, meta-analytic findings indicate that job satisfaction is related to a variety of health outcomes such as anxiety and depression (Faragher et al., Citation2013).

Skogstad, Aasland, et al. (Citation2014) compared the effects of constructive, active-destructive (i.e. tyrannical), and laissez-faire leadership on job satisfaction in a representative sample of the Norwegian workforce. The results showed that the effects depended on the timeframe. Active destructive leadership showed an effect after a 6-month time lag, whereas laissez-faire leadership was concluded to have influences later on (i.e. measured after 2 years). They concluded that laissez-faire leadership may be a stress-inducing form of leadership that accumulates over long period of time (Skogstad, Aasland, et al., Citation2014). Thus, the combined and spiraling loss of resources as a result of a laissez-faire leadership in conjunction with organizational restructuring would likely render lower employee job satisfaction.

We, therefore, hypothesized the following:

H2a: In the context of organizational restructuring, managers’ laissez-faire leadership will be negatively associated with employees’ job satisfaction over time (i.e. between baseline and 2-year follow-up), when controlling for baseline levels of job satisfaction.

Work-related burnout (i.e. perceptions of physical and psychological fatigue and exhaustion related to work; Kristensen et al., Citation2005) has infrequently been studied as an employee well-being outcome of organizational restructuring (Bellou & Chatzinikou, Citation2015). One exception is the study by Dubois et al. (Citation2014), which found that employees’ perceived loss of valued resources resulted in an increased risk for work-related burnout.

A few studies, mainly cross-sectional, have related laissez-faire leadership directly to employee work-related burnout. Some of these have found no relationship (e.g. Vullinghs et al., Citation2018), whereas others have found support for a direct relationship (e.g. Usman et al., Citation2020). However, from a COR-theory perspective, the increased strain that laissez-faire leadership in the context of organizational restructuring may entail is likely to be associated with higher employee stress levels in the long-term and thus work-related burnout (Diebig & Bormann, Citation2020). This assumption is supported by studies showing a relationship between managers’ laissez-faire leadership and employees’ increased levels of hair cortisol (as a stress indicator; Diebig et al., Citation2016) and daily stress (Diebig & Bormann, Citation2020). Based on the above, we, therefore, hypothesized the following:

H2b: In the context of organizational restructuring, managers’ laissez-faire leadership will be positively associated over time (i.e. between baseline and two-years follow-up) with employee work-related burnout, after controlling for baseline levels of work-related burnout.

Role Clarity as the Mediating Mechanism Between Managers’ Laissez-faire Leadership and Employee Wellbeing

As suggested in the leadership literature (e.g. Skogstad, Hetland, et al., Citation2014; Vullinghs et al., Citation2018), and as argued above, managers’ constructive leadership behaviours form a key driver for employees’ experienced role clarity. Consequently, managers’ laissez-faire leadership may instead undermine employees’ ability to successfully enact their (new) work roles. In times of organizational restructuring, work roles are often transformed, which may in itself be perceived as a resource loss (e.g. of competence and relationships connected to the roles). If managers are unable to, or avoid, helping employees to adapt to the designated new roles, then employees’ strive for regaining resources may be wasted and instead lead to resource depletion (Barling & Frone, Citation2017; Diebig & Bormann, Citation2020).

As such, laissez-faire leadership is understood primarily as a role stressor, and inability to regaining role clarity the mechanism through which laissez-faire leadership relates to hampered employee well-being (Barling & Frone, Citation2017). Thus, managers’ laissez-faire leadership during organizational restructuring can be seen as hindering the (re-)creation of role clarity, as an important mechanism for employees striving to regain or compensate for the loss of this conditional resource.

The link between laissez-faire leadership and employee well-being may, in other words, best be understood as a sequential mediational process, with role clarity as the mediator. Although not previously studied in conjunction with an organizational restructure, three cross-sectional leadership studies have examined the relationships between laissez-faire leadership, role clarity or role ambiguity, and employee wellbeing (Barling & Frone, Citation2017; Skogstad et al., Citation2007; Vullinghs et al., Citation2018). The results from these studies, additionally to the theoretic arguments above, suggest that this mediation process is probable. We, therefore, hypothesized the following:

H3a: In the context of organizational restructuring, role clarity (at 9-month follow-up) will mediate the relationship between managers’ laissez-faire leadership (at baseline) and job satisfaction (at 2-year follow-up).

H3b: In the context of organizational restructuring, role clarity (at 9-month follow-up) will mediate the relationship between managers’ laissez-faire leadership (at baseline) and work-related burnout (at 2-year follow-up).

Method

Participants and Procedures

The participants comprised employees working at a process-industry site in Sweden during a large-scale organizational restructure. Overall, the restructuring initiative aimed to increase profitability and thereby maintain a competitive market position. The restructure included hardware investments, transforming the organizational structure and implementing new job roles. The structural changes aimed to facilitate effective decision making. Specialist representation (e.g. HR representatives and engineers) was included in the lowest-level (section) management groups to make decisions closer to operations. The restructure also aimed to streamline positions in terms of work-role expansion for blue-collar employees, reducing the work force through natural turnover, and implementing a management-by-objective follow-up system. Managers’ were instructed to involve team members in the change, to clarify new roles, and to help employees adopt new behaviours (e.g. taking initiative to improve operations, collaborate across team borders, and report safety issues).

All registered employees of the organization (N = 843 at baseline) received a web-based survey. For the present study, we used data from the baseline (T1), the 9-month follow-up (T2), and the 2-year follow-up (T3). The total sample (i.e. employees responding to one or more of the three surveys at T1–T3 who gave consent to use the data in research) comprised 601 employees reporting to 62 leaders. Of these, 19.9% were women, the mean age was 47.67 (SD = 12.12), and the mean organizational tenure was 21.21 (SD = 14.68). At T1, a sample of 450 employees (73% of the total sample) rated questions in the present study and gave consent to use data for research purposes. Of the respondents, 18.4% were women, the mean age was 49.43 (SD = 11.61), and the mean organizational tenure was 23.00 (SD = 14.13). At the first follow-up (T2), a sample of 341 employees responded to the questions (76% of the T1 respondents and 55% of the total sample). Of these, 22% were women, the mean age was 48.46 (SD = 11.62), and the mean organizational tenure was 23.41 (SD = 14.49). At the second follow-up (T3) a sample of 393 respondents rated questions (87% of the T1 sample and 64% of the total sample). Of these, 20.4% were women, the mean age was 46.67 (SD = 11.51), and the mean organizational tenure was 21.23 (SD = 14.44).

No statistically significant differences appeared for any variables at T1 (i.e. laissez-faire leadership, job satisfaction, and work-related burnout) when comparing participants who dropped out between T1 and T2 with participants who remained at T2, nor between participants who dropped out between T2 and T3 and those remaining at T3. Similarly, no statistically significant difference appeared in responses to role clarity at T2 between those who dropped out at T3 and those who remained at T3. However, when comparing respondents’ demographics (i.e. sex, age, and tenure) at various time points, statistically significant differences appeared for age (t = 2.09, df = 732, p = .04) and for tenure (t = 2.04, df = 732, p = .04) between the samples at T2 and T3. These differences (i.e. lower age and tenure over time) may exist via the work force’s reduction through natural turnover that occurred during these 2 years.

Measures

All the scales have previous translations into Swedish, so we used the published translations of these scales. The internal consistency (ω) of all scales appears in .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics – latent means, standard deviations, reliabilities, and latent variable correlations.

Laissez-faire Leadership

We used the four-item laissez-faire scale from the Swedish version of the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire 5X-short (Bass & Avolio, Citation2000) to assess laissez-faire leadership. A sample item appears as follows: ‘[My immediate supervisor] avoids getting involved when important issues arise.’ Respondents used a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (frequently, if not always).

Role Clarity

We measured role clarity using the three-item scale from the second version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ-II; Berthelsen et al., Citation2014; Pejtersen et al., Citation2010). A sample item appears as follows: ‘Do you know exactly what is expected of you at work?’ Respondents used a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (to a very low extent) to 4 (to a very large extent).

Job Satisfaction

We used the four-item scale in COPSOQ-II (Berthelsen et al., Citation2014; Pejtersen et al., Citation2010) to measure job satisfaction. A sample item appears as follows: ‘[Regarding your work in general. How pleased are you with] your job as a whole, everything taken into consideration?’ Respondents used four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very unsatisfied) to 4 (very satisfied). The respondents also, in accordance with the original scale, had the option 0 (not relevant), and we omitted these answers from the analysis.

Work-related Burnout

We assessed work-related burnout using three items from the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (Kristensen et al., Citation2005). An example item appears as follows: ‘Do you get emotionally exhausted from your work’ Respondents used a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (to a very low degree) to 5 (to a very high degree). The scale’s internal consistency (ω) at T2 appears in .

Control Variables

We controlled for the follower’s age in years, sex (male = 1, female = 2), and tenure because previous studies show these demographics might influence employees’ responses to outcome variables used in our study (Brewer & Shapard, Citation2004; Clark et al., Citation1996; Clark & Oswald, Citation1996; Randall, Citation2007).

Analysis

We conducted statistical analyses using Mplus version 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2019) and used a robust maximum likelihood estimation for all SEM analyses. As recommended, we handled missing data by using a full-information maximum likelihood robust estimation that uses all available information from the covariance matrix (Enders, Citation2010). We conducted the analyses in four steps.

First, we examined the longitudinal measurement invariance in the job satisfaction and work-related burnout scale (i.e. between T1 and T3) to ensure that invariance over time did not yield biased estimates and erroneous interpretations (Widaman et al., Citation2010). In line with Chen’s (Citation2007) recommendations for evaluating structural invariance across models, a change in CFI/TLI (ΔCFI/TLI) of less than 0.01 and a change in RMSEA (ΔRMSEA) of less than 0.015 or a change in SRMR (ΔSRMR) of less than 0.03 (0.01 for scalar) supports invariance over time.

Second, we included all latent constructs to evaluate the model fit and correlations among constructs in a measurement model. We used multiple fit indices to evaluate the model fit. We used traditional cut-off criteria (CFI > .90; SRMR and RMSEA < .08) to indicate an acceptable fit (Kline, Citation2015) and stricter criteria (CFI and TLI > .95; SRMR <.08 and RMSEA<.06) to indicate a good fit (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999; Kline, Citation2015). We allowed the outcome variables’ indicators to covary over time to account for indicator-specific effects over time (Little et al., Citation2007).

Third, based on the measurement model, we constructed a structural model for the hypothesis. In the structural model, job satisfaction and work-related burnout at T3 were regressed on role clarity at T2 and laissez-faire at T1, as well as on job satisfaction and work-related burnout on at T1 (to control for baseline values). Role clarity at T2 was regressed on laissez-faire at T1. Role clarity at T2 and job satisfaction and work-related burnout at T3 were all regressed on the three control variables (age, sex, and tenure). We collected data from various work units with different supervisors, so we used the TYPE = COMPLEX option in MPlus to account for data clustering (Muthen & Satorra, Citation1995). As in the measurement model, we allowed the outcome variables’ indicators to covary over time to account for indicator-specific effects over time (Little et al., Citation2007).

Fourth, we used the recommended bootstrapping procedure (Rucker et al., Citation2011) with a bootstrap sample of 3,000 to assess point-estimates (PE) and the 95% bias-corrected (BC) confidence intervals (CI) of laissez-faire leadership’s indirect relations to the distal outcomes in our model.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations between all study variables appear in .

All variables at T1, T2, and T3 correlated in expected directions. Laissez-faire leadership negatively associated with job satisfaction (at T1 and T3) and with role clarity (at T2), and it positively associated with work-related burnout (at T1 and T3). Job satisfaction negatively associated with work-related burnout at T1 and at T3. Job satisfaction and work-related burnout both positively associated with the same measure across time (e.g. job satisfaction at T1 with job satisfaction at T3).

The longitudinal invariance test for job satisfaction and work-related burnout between T1 and T3 supported the use of a scalar model in both cases. The measurement model with job satisfaction and work-related burnout at a scalar level showed a good fit for data: χ2 (107) = 158.24, p = .00, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = .028, CI [.02 .04], SRMR = .051. We, therefore, continued to test our hypothesis in the structural model, with job satisfaction and work-related burnout at T1 and T3 constricted to a scalar level. The structural model also showed a good fit for data: χ2 (235) = 384.28, p = .00, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = .033, CI [.03 .04], SRMR = .076. The model fit results for all the longitudinal models appear in .

Table 2. Model fit of longitudinal CFA models.

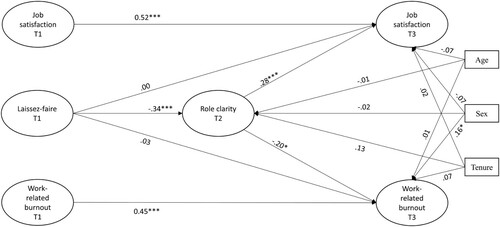

In line with Hypothesis 1, laissez-faire leadership at T1 negatively associated with role clarity at T2 at a statistically significant level (β = −0.34, p < .01). Laissez-faire leadership did not, as hypothesized (Hypotheses 2a and b), directly relate to job satisfaction (β = 0.00, ns) nor to work-related burnout (β = −0.03, ns). However, laissez-faire leadership’s indirect relation to job satisfaction through role clarity was significant (PE = –.07, 95% BC, CI [–.143, –.024]), as was laissez-faire leadership’s specific indirect relation to work-related burnout through role clarity (PE = .08; 95% BC, CI [.001, .200]). This supports Hypotheses 3a and b. None of the control variables (age, sex, and tenure) related to any of the outcomes in this study, except that sex-related to work-related burnout (β = 0.16, p < .05), indicating women reported higher levels of work-related burnout. The structural model with paths and standardized coefficients appears in .

Figure 1. Standardized parameter estimates for the structural mediation model. T1 = time 1 (baseline), T2 = time 2 (nine month follow-up), T3 = time 3 (two years follow-up). ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05. Correlations between latent variables at the same measurement-point were omitted for presentation reasons.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the prospective relationship of laissez-faire leadership on three employee outcomes (role clarity, job satisfaction, and work-related burnout) and to test role clarity as a mechanism that carries laissez faire leadership’s influence on well-being in the context of organizational restructuring. Laissez-faire leadership related to role clarity 9 months later (in line with Hypothesis 1). We found no direct relationship between laissez-faire leadership and employees’ job satisfaction and work-related burnout, contradicting Hypotheses 2a and b. Instead, role clarity mediated the relationship between laissez-faire leadership and employees’ well-being in terms of job satisfaction or on work-related burnout after 2 years (in line with Hypothesis 3a and b).

Our results thus suggest that managers’ laissez-faire leadership in the context of restructuring may undermine employees’ ability to achieve clarity within their new work roles, which in turn may deteriorate their wellbeing. From a COR perspective, the results pinpoint the proposed negative loss spiral that managers’ laissez-faire leadership may contribute to during organizational restructures. By undermining employees’ possibilities to (re-)gain role clarity, laissez-faire leadership becomes a role stressor. Employees’ efforts to reduce stress by seeking manager guidance and support thus appear wasted, and instead add to the stress and, over time, may further resource depletion and well-being reduction (Barling & Frone, Citation2017; Diebig & Bormann, Citation2020). Our findings also align with previous cross-sectional empirical leadership research on the relationship between laissez-faire leadership, role clarity and employee wellbeing outcomes (Barling & Frone, Citation2017; Skogstad et al., Citation2007; Vullinghs et al., Citation2018). By using a longitudinal design with control for outcomes at baseline, we strengthen the assumptions of the relationships between these variables. The use of this longitudinal design also advances the understanding of how and why undesirable employee outcomes during organizational restructuring may be produced over time (i.e. 15 months).

Implications

Although the importance of considering managers’ laissez-faire leadership has been called for, it has received sparse research attention compared to constructive leadership, both in general and in the context of organizational restructuring (Bligh et al., Citation2018). The results of this study indicate that with managers performing a high degree of laissez-faire leadership organizations do not only run the risk of not reaching intended change outcomes (as has previously been shown; Bligh et al., Citation2018). Employees’ who perceive that their manager performs a high degree of laissez-faire leadership in times of restructuring may also experience negative change in their wellbeing. Thus, the outcomes of laissez-faire leadership during organizational restructuring are not only a question of absence of positive results, but may also affect employee health negatively. From this perspective, managers’ laissez-faire leadership in times of organizational restructuring is a potential employee stressor that organizations should consider minimizing to secure employee wellbeing. Although this study contributes to our understanding of how (affects role clarity), why (perceived resource loss), and when (during restructuring) managers’ laissez-faire leadership affects employee outcomes, there is still more research needed for drawing more general conclusions. We suggest that future studies on mangers’ leadership during organizational restructuring, and organizational change in general, consider not only the outcomes of constructive, but also to higher degree laissez-faire leadership behaviours.

Additionally, more research is needed to clarify under which conditions different leadership behaviours are more or less effective. As has been proposed (Simpson et al., Citation2002; Yang, Citation2015), non-involvement behaviours may sometimes constitute a ground for positive outcomes. This suggests that there may be contextual (e.g. cultural) and perhaps employee characteristics (e.g. experience) that moderates the relation between laissez-faire leadership behaviours and outcomes. Laissez-faire is operationalized in most studies, including the present, as employee ratings of managers not being present when needed. Hence, focusing on employees’ perceptions and expectations, rather than managers’ actual behaviours and intentions with these behaviours. Alternative conceptualizations, other measures, and ways of evaluation (e.g. mixed method) may be needed to capture when, how, and for whom, managers backing-off may play a potentially important function that can contribute to positive outcomes.

Furthermore, we suggest that organizations can work actively to prevent negative outcomes of laissez-faire leadership during organizational restructuring. First, organizations can include information about how laissez-faire leadership behaviours may influence outcomes in change-leadership training, and change preparations. This can raise managers’ awareness regarding the outcomes of these leadership behaviours. Additionally, it can help managers seek help when they cannot provide employees with the support they require (e.g. because of lack of resources).

Previous research has shown that laissez-faire leadership might have more extreme and long-lasting (negative) effects compared to the (positive) effects of constructive leadership (Skogstad, Aasland, et al., Citation2014). This implies that organizations should strive towards identify laissez-faire behaviours among mangers, and provide them with additional training or support to act in a more constructive fashion. Alternatively, to make them aware that the ambition to empower employees by withdrawing may be misunderstood if not communicated as a strategy, and applied in situations where employees have the right prerequisites (e.g. competence) to fill the space.

Second, organizational restructuring is a challenge for managers and for employees. Based on this study’s results, we recommend monitoring role clarity as essential to the understanding of which work groups might struggle more with adapting to the change. Instead of monitoring laissez-faire leadership, which may have several problems (e.g. reducing trust), researchers could alternatively focus on the mechanisms of laissez-faire leadership (e.g. adapting new roles) to detect the work groups with potential challenges. Organizations could then support work groups and managers in order to increase their resources and, thereby, reduce the amount of laissez-faire leadership, and its consequences.

Limitations

The current study has some shortcomings. First, this study used a blue-collar sample (i.e. in a process industry) where staff primarily comprising men who had a high mean age and low turnover. This sample might represent this industry, but we recommend replicating the study within other sectors and forms of organizational change to understand the investigated relationship using different samples in different context to increase the results’ generalizability.

Second, this study relies on self-reports from employees. This may yield a mono-method bias (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003; Spector, Citation2006). However, the constructs investigated here comprise subjective experiences most accurately assessed via self-reported data. To reduce the risk of mono-method bias, we took several measures. For example, we assured participants that we would protect their identity and privacy at all times (Conway & Lance, Citation2010). The questionnaire was also designed so the constructs under investigation were presented in separate thematic parts of the survey, and short introduction texts helped participants transition to different parts (Podsakoff et al., Citation2011). Future studies may include outcomes of laissez-faire leadership that could be objectively assessed, such as sickness absence due to mental illness. Using other, complementary methods, such as interviews or observation, could also provide a more nuanced picture of managers’ leadership behaviours and employees’ reactions.

Third, we chose a time lag of 9–15 months. Although Skogstad, Hetland, et al. (Citation2014) may indicate that laissez-faire leadership’s effects may develop over the long-term (> 2 years), the appropriate time lag to study the short- and long-term effects of laissez-faire leadership remains unclear. Shorter time lags might also be more appropriate, especially when investigating the effects of laissez-faire leadership in the context of organizational restructuring. Identifying relevant time lags for investigating laissez-faire leadership is one way to further understand the mechanisms of laissez-faire leadership. We recommend that future research focus on identifying relevant mechanisms to further our understanding how and why the negative consequences of laissez-faire leadership may evolve.

Conclusion

This study examines the prospective relationship between laissez-faire leadership and role clarity as well as two well-being outcomes (job satisfaction and work-related burnout) in the context of an organizational restructuring. In line with our prediction, we found a negative prospective relationship between laissez-faire leadership and role clarity. Role clarity was also found to mediate the relationship between laissez-faire leadership and employee well-being. To reduce the risk of adding to the employee stress that organizational restructuring may include, it is important for organizations to be aware and counteract managers’ laissez-faire leadership behaviours when performing such changes. If not, managers’ unavailability when needed may contribute to further resource drain rather than regain, and consequently to employees’ resource depletion.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the organization and its employees who participated in the study. We would also like to thank consultants Mikal Björkström and Maria Eliasson for helping us with the data collection. Ethical approval for this study was received by [Regional Board of Ethics (EPN), Umeå] under Grant [2015/23-31Ö].

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Robert Lundmark

Robert Lundmark (PhD) is a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Psychology, Umeå University, Sweden. His research is focused on managers’ role and leadership behaviours during implementation and sustainment of organizational change, as well as interventions targeting managers’ capabilities to lead organizational change.

Anne Richter

Anne Richter (PhD) is an Associate Professor in psychology at the Medical Management Centre of Karolinska Institutet, Sweden. Her research interests focus on workplace change, in particular how new ways of working can be introduced through providing a supporting context (e.g. through leadership or interventions on the right level) as well as how employees experience these changes (e.g. experiencing job insecurity).

Susanne Tafvelin

Susanne Tafvelin (PhD) is an Associate Professor at the Department of Psychology, Umeå University, Sweden. Her research focus on the impact leaders have on employees, as well as of transfer of leadership training.

References

- Balogun, J. (2007). The practice of organizational restructuring: From design to reality. European Management Journal, 25(2), 81–91. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2007.02.001

- Bamberger, S. G., Vinding, A. L., Larsen, A., Nielsen, P., Fonager, K., Nielsen, R. N., & Omland, Ø. (2012). Impact of organisational change on mental health: A systematic review. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 69(8), 592–598. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2011-100381

- Barling, J., & Frone, M. R. (2017). If only my leader would just do something! Passive leadership undermines employee well-being through role stressors and psychological resource depletion. Stress and Health, 33(3), 211–222. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2697

- Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (2000). MLQ, Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire sampler set: Technical report, leader form, rater form, and scoring key for MLQ form 5x-short. Mind Garden.

- Battilana, J., Gilmartin, M., Sengul, M., Pache, A. C., & Alexander, J. A. (2010). Leadership competencies for implementing planned organizational change. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(3), 422–438. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.03.007

- Bellou, V., & Chatzinikou, I. (2015). Preventing employee burnout during episodic organizational changes. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 28(5), 673–688. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-11-2014-0197

- Berthelsen, H., Westerlund, H., & Søndergård Kristensen, T. (2014). Stressforskningsrapport nr 326: COPSOQ II-en uppdatering och språklig validering av den svenska versionen av en enkät för kartläggning av den psykosociala arbetsmiljön på arbetsplatser. Stressforskningsintitutet.

- Bliese, P. D., & Castro, C. A. (2000). Role clarity, work overload and organizational support: Multilevel evidence of the importance of support. Work & Stress, 14(1), 65–73. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/026783700417230

- Bligh, M. C., Kohles, J. C., & Yan, Q. (2018). Leading and learning to change: The role of leadership style and mindset in error learning and organizational change. Journal of Change Management, 18(2), 116–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2018.1446693

- Brewer, E. W., & Shapard, L. (2004). Employee burnout: A meta-analysis of the relationship between age or years of experience. Human Resource Development Review, 3(2), 102–123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484304263335

- Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

- Clark, A. E., & Oswald, A. J. (1996). Satisfaction and comparison income. Journal of Public Economics, 61(3), 359–381. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2727(95)01564-7

- Clark, E. A., Oswald, A., & Warr, P. (1996). Is job satisfaction U-shaped? Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 69(1), 57–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1996.tb00600.x

- Conway, J. M., & Lance, C. E. (2010). What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(3), 325–334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9181-6

- Danna, K., & Griffin, R. W. (1999). Health and well-being in the workplace: A review and synthesis of the literature. Journal of Management, 25(3), 357–384. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639902500305

- Day, A., Crown, S. N., & Ivany, M. (2017). Organisational change and employee burnout: The moderating effects of support and job control. Safety Science, 100, 4–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2017.03.004

- de Jong, T., Wiezer, N., de Weerd, M., Nielsen, K., Mattila-Holappa, P., & Mockałło, Z. (2016). The impact of restructuring on employee well-being: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Work & Stress, 30(1), 91–114. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2015.1136710

- Diebig, M., & Bormann, K. C. (2020). The dynamic relationship between laissez-faire leadership and day-level stress: A role theory perspective. German Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(3), 324–344. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2397002219900177

- Diebig, M., Bormann, K. C., & Rowold, J. (2016). A double-edged sword: Relationship between full-range leadership behaviors and followers’ hair cortisol level. The Leadership Quarterly, 27(4), 684–696. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.04.001

- Dubois, C. A., Bentein, K., Mansour, J. B., Gilbert, F., & Bédard, J. L. (2014). Why some employees adopt or resist reorganization of work practices in health care: Associations between perceived loss of resources, burnout, and attitudes to change. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(1), 187–201. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110100187

- Enders, C. K. (2010). Applied missing data analysis. Guilford Press.

- Faragher, E. B., Cass, M., & Cooper, C. L. (2013). The relationship between job satisfaction and health: A meta-analysis. In Cooper, C. L. (Eds.), From stress to wellbeing Volume 1 (pp. 254–271). London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137310651_12

- Farahnak, L. R., Ehrhart, M. G., Torres, E. M., & Aarons, G. A. (2020). The influence of transformational leadership and leader attitudes on subordinate attitudes and implementation success. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 27(1), 98–111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051818824529

- Fischer, T., Dietz, J., & Antonakis, J. (2017). Leadership process models: A review and synthesis. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1726–1753. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316682830

- Halbesleben, J. R. B., Wheeler, A. R., & Paustian-Underdahl, S. C. (2013). The impact of furloughs on emotional exhaustion, self-rated performance, and recovery experiences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(3), 492–503. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032242

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Judge, T. A., Weiss, H. M., Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., & Hulin, C. L. (2017). Job attitudes, job satisfaction, and job affect: A century of continuity and of change. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 356–374. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000181

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press.

- Kristensen, T. S., Borritz, M., Villadsen, E., & Christensen, K. B. (2005). The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work & Stress, 19(3), 192–207. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370500297720

- Little, T. D., Preacher, K. J., Selig, J. P., & Card, N. A. (2007). New developments in latent variable panel analyses of longitudinal data. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 31(4), 357–365. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025407077757

- Lundmark, R., Nielsen, K., Hasson, H., von Thiele Schwarz, U., & Tafvelin, S. (2020). No leader is an island: Contextual antecedents to line managers’ constructive and destructive leadership during an organizational intervention. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 13(2), 173–188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWHM-05-2019-0065

- Lundmark, R., Nordin, M., Yepes-Baldó, M., Romeo, M., & Westerberg, K. (2020). Cold wind of change: Associations between organizational change, turnover intention, overcommitment and quality of care in Spanish and Swedish eldercare organizations. Nursing Open, 8(1), 163–170. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.615

- Muthen, B. O., & Satorra, A. (1995). Complex sample data in structural equation modeling. Sociological Methodology, 267–316. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/271070

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2019). Mplus. The comprehensive modelling program for applied researchers: User’s guide.

- Neves, P., & Schyns, B. (2018). With the bad comes what change? The interplay between destructive leadership and organizational change. Journal of Change Management, 18(2), 91–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2018.1446699

- Otto, K., Thomson, B., & Rigotti, T. (2018). When dark leadership exacerbates the effects of restructuring. Journal of Change Management, 18(2), 96–115. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2018.1446691

- Pejtersen, J. H., Kristensen, T. S., Borg, V., & Bjorner, J. B. (2010). The second version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 38(3_suppl), 8–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494809349858

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2011). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

- Quinlan, M., & Bohle, P. (2009). Overstretched and unreciprocated commitment: Reviewing research on the occupational health and safety effects of downsizing and job insecurity. International Journal of Health Services, 39(1), 1–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2190/HS.39.1.a

- Rafferty, A. E., & Griffin, M. A. (2006). Perceptions of organizational change: A stress and coping perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(5), 1154. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.1154

- Randall, K. J. (2007). Examining the relationship between burnout and age among Anglican clergy in England and Wales. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 10(1), 39–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670601012303

- Robert, V., & Vandenberghe, C. (2020). Laissez-faire leadership and affective commitment: The roles of leader-member exchange and subordinate relational self-concept. Journal of Business and Psychology, 36, 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-020-09700-9

- Robinson, S. L., O’Reilly, J., & Wang, W. (2013). Invisible at work: An integrated model of workplace ostracism. Journal of Management, 39(1), 203–231. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312466141

- Rucker, D. D., Preacher, K. J., Tormala, Z. L., & Petty, R. E. (2011). Mediation analysis in social psychology: Current practices and new recommendations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(6), 359–371. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00355.x

- Saksvik, PØ, Tvedt, S. D., Nytr⊘, K., Andersen, G. R., Andersen, T. K., Buvik, M. P., & Torvatn, H. (2007). Developing criteria for healthy organizational change. Work & Stress, 21(3), 243–263. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370701685707

- Simpson, P. F., French, R., & Harvey, C. E. (2002). Leadership and negative capability. Human Relations, 55(10), 1209–1226. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/a028081

- Skogstad, A., Aasland, M. S., Nielsen, M. B., Hetland, J., Matthiesen, S. B., & Einarsen, S. (2014). The relative effects of constructive, laissez-faire, and tyrannical leadership on subordinate job satisfaction. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 222(4), 221–232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000189

- Skogstad, A., Einarsen, S., Torsheim, T., Aasland, M. S., & Hetland, H. (2007). The destructiveness of laissez-faire leadership behavior. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.12.1.80

- Skogstad, A., Hetland, J., Glasø, L., & Einarsen, S. (2014). Is avoidant leadership a root cause of subordinate stress? Longitudinal relationships between laissez-faire leadership and role ambiguity. Work & Stress, 28(4), 323–341. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2014.957362

- Smollan, R. K. (2015). Causes of stress before, during and after organizational change: A qualitative study. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 28(2), 301–314. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-03-2014-0055

- Spector, P. E. (2006). Method variance in organizational research: Truth or urban legend? Organizational Research Methods, 9(2), 221–232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428105284955

- Stouten, J., Rousseau, D. M., & De Cremer, D. (2018). Successful organizational change: Integrating the management practice and scholarly literatures. Academy of Management Annals, 12(2), 752–788. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2016.0095

- Usman, M., Ali, M., Yousaf, Z., Anwar, F., Waqas, M., & Khan, M. A. S. (2020). The relationship between laissez-faire leadership and burnout: Mediation through work alienation and the moderating role of political skill. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 37(4), 423–434. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.1568

- Vullinghs, J. T., De Hoogh, A. H., Den Hartog, D. N., & Boon, C. (2018). Ethical and passive leadership and their joint relationships with burnout via role clarity and role overload. Journal of Business Ethics, 165(4), 719–733. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4084-y

- Westgaard, R. H., & Winkel, J. (2011). Occupational musculoskeletal and mental health: Significance of rationalization and opportunities to create sustainable production systems – a systematic review. Applied Ergonomics, 42(2), 261–296. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2010.07.002

- Widaman, K. F., Ferrer, E., & Conger, R. D. (2010). Factorial invariance within longitudinal structural equation models: Measuring the same construct across time. Child Development Perspectives, 4(1), 10–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2009.00110.x

- Wong, S. I., & Giessner, S. R. (2018). The thin line between empowering and laissez-faire leadership: An expectancy-match perspective. Journal of Management, 44(2), 757–783. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315574597

- Yang, I. (2015). Positive effects of laissez-faire leadership: Conceptual exploration. Journal of Management Development, 34(10), 1246–1261. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-02-2015-0016

- Yukl, G. (2006). Leadership in organizations (6th ed.). Pearson-Prentice Hall.