ABSTRACT

Despite a plethora of frameworks and processes, in planned organizational change models (POCMs), the role of change organizations, i.e. organizations dedicated to change, remains rarely explored. In this paper, we delve into this subject via a multiple case-based research design studying eleven large Finnish companies via 33 interviews. We find that although all studied case companies bear some component(s) of change organizations, these vary substantially. To this end, our findings bear three contributions. First, we propose a typology on change organizations as consisting of change networks, change teams and individual change roles, incorporating varying dimensions each. We further found three interrelations between these dimensions. Second, we demonstrate that change organizations exist in company practice more than they appear in the POCM literature. Third, we develop a framework for the evaluation of the maturity of a company’s change organization. Going forward, our findings are a call for further research on change organizations and their role in planned organizational change.

MAD statement

This article aims to Make a Difference (MAD) by offering a coherent lens that can be used both in the research and in the development of change organizations, in theory and in practice. Change organizations (networks, teams and roles dedicated to change) are a somewhat underrepresented dimension in classic planned organizational change models. However, in practice, companies’ change organizations play various active roles in planned change. Building on evidence from a multiple case study of eleven Finnish large companies, we suggest a multi-dimensional typology on change organizations. Through identified interrelations, we suggest that certain types of change organizations may be preferred over others in particular circumstances. In addition, we offer a change organization maturity framework for developing and evaluating companies’ change organizations.

Introduction

Change is present all around us – as an unlimited force, it penetrates and flows through the everyday make-up of society. When considering recent global crises and major changes such as the COVID-19 pandemic, Brexit or global warming, it is evident that change has become the ‘new normal’. The organizations with the ability to change and adapt quickly have better probability of enduring amid this ‘turbulent climate’ (Smith et al., Citation2012). There is a consensus that the pace of change has never been greater than in the current continuously evolving business environment (By Todnem, Citation2005).

Yet, there are different types of change. While on the one hand, change can be unprecedented, ambiguous and hard to grasp, on the other hand, it can also be planned, foreseen and managed. Notwithstanding, there are numerous theories and models suggesting differing approaches toward managing organizational change. Whether it be Kurt Lewin’s seminal three-step model of planned change (Burnes, Citation2004a; Cummings et al., Citation2015; Lewin, Citation1947) and its adherents, emergent approaches to change (Burnes, Citation2004b; Livne-Tarandach & Bartunek, Citation2009) or a contingency approach to change (Dunphy & Stace, Citation1996), divergent views on organizational change co-exist.

In the scope of this paper, we examine planned organizational change, adopting the conception of organizational change as intentional and manageable. We treat change as ‘a deliberate strategy’ (Mintzberg & Waters, Citation1985). Planned organizational change models (POCMs) comprise of different steps/phases/variables through which organizational change is approached. Building on Lewin’s (Citation1947) work, POCMs have undergone significant development in the past half-century (Rosenbaum et al., Citation2017), offering numerous frameworks for managing planned organizational change. Despite these advances, in the bulk of this work, the role of change organizations has received scarce attention.

In this paper, we start addressing this theoretical gap in understanding. The research question guiding this paper is: what do companies’ change organizations consist of? Given the lack of prior research on change organizations in the pursuit of planned change, we adopted a grounded theory-building approach (Eisenhardt et al., Citation2016; Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967), via a multiple case design (Eisenhardt, Citation1989; Yin, Citation1994), studying eleven large Finnish companies via 33 interviews.

In this paper, focusing on change organizations means analyzing organizations within organizations. Although it can be debated if there is such a thing as stability, in this paper, we consider organizations and change organizations as somewhat stabile and routinized, consisting of ‘things’ instead of ‘processes’ (Tsoukas & Chia, Citation2002). We have chosen to focus on the factual and the tangible, taking a ‘snapshot’ view as our focal point. This means that for us, organizations are not a process or a social construction. We look at organizations from a ‘formal arrangements’ (Nadler & Tushman, Citation1980) perspective, where organization and job design are mainly ‘ … explicitly designed and specified, usually in writing’ – whilst simultaneously acknowledging the fact that informal arrangements exist and that organizations do develop and change continuously. When examining change organizations in our case studies, we analyzed what is visible at the moment of study.

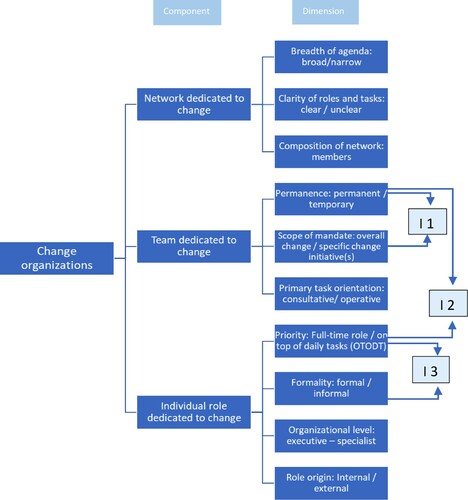

The main contribution of this paper is three-fold. First, we present a typology on change organizations. Based on an abductive process, we define change organizations as change networks, change teams and individual change roles. We demonstrate that change organizations differ via many dimensions and we further identify three interrelations between these dimensions. Second, we show that change organizations seem to be a somewhat underrepresented element in planned organizational change models (POCMs). We add to the theories of planned organizational change models by pointing out the role of change organizations, which we currently see as inadequately represented in contrast to what our empirical data suggests. Third, we offer a change maturity framework for beginning to assess the maturity of companies’ change organizations. We believe that our contributions facilitate further studies on the role of change organizations in planned organizational change, while also developing companies’ change organizations in practice.

The paper is structured as follows. We proceed in the next section with a review of the literature, examining prior research on planned organizational change models with respect to how they cover change organizations. Section three presents our research setting and methods. In section four, our findings are presented. Section five concludes by discussing the paper’s theoretical contribution, practical implications and limitations, while identifying future research directions.

Change Organizations in Prior Literature on Planned Change

When examining how prior literature on planned organizational change has studied change organizations, we used the recent review by Rosenbaum et al. (Citation2017) on planned organizational change models as our backbone. Amid the plethora of models on planned organizational change, Rosenbaum et al. (Citation2017) provide a comprehensive review of this field. In addition to Lewin’s seminal three-step model of planned change, their review covers 14 well-known and most cited models on planned change, encompassing both academic and practitioner-based models. It deserves mention that with some planned organizational change models (such as Proscis’s ADKAR model, Citation2020), the role of change organizations may not be visible in the original model itself, though discussed in the authors’ subsequent publications. Our analysis is based on an analysis of the original models and approaches, as presented in Rosenbaum et al. (Citation2017).

In the following, we present the findings of our analysis as regards prior literature on change organizations, with respect to three levels of analysis: (1) change networks, i.e. networks dedicated to change, (2) change teams, i.e. teams dedicated to change, as well as (3) individual roles dedicated to change. presents our analysis of the fifteen planned organizational change models from Rosenbaum et al.’s (Citation2017) review and summarizes our findings regarding the presence and role of change networks, change teams and individual roles dedicated to change in these models. Further, we position our analysis on change organizations into the broader literature on planned change.

Table 1. A review of change organizations in planned organizational change models (POCMs).

Networks Assigned to Planned Change

We approach change networks as networks bearing roles of active responsibility in planned change, leaving out change recipient networks (Tenkasi & Chesmore, Citation2003). Taking a closer look (see ), five of the examined fifteen planned organizational change models in Rosenbaum et al. (Citation2017) mention change networks. Zooming closer, we identify two categories.

On the one hand, two of the models merely mention change networks. To this end, Peters and Waterman (Citation1982) emphasize that if there are no support networks for champions, no innovation and change will happen. Networks therefore bear a crucial role in delivering change successfully. Senge et al. (Citation1999), in turn, acknowledge that to deliver change, networks of committed people are needed.

On the other hand, three of the models suggest building specific networks with individuals actively facilitating organizational change. To this end, ACMP (Association of Change Management Professionals, Citation2020) distinguishes the possibility of building sponsor networks and change agent networks. Dunphy et al. (Citation2003), in turn, state that change agents need to operate in networks, given that networks are more impactful than individual change agents. Change agent networks can comprise of various change agent roles operating at various levels to increase influence. All the while, Beckhard and Harris (Citation1977/Citation1987) distinguish between two types of network structures: the ‘diagonal slice’ suggesting a team of a representative sample across all organizational areas, and the ‘kitchen cabinet’ composing of the executives’ close collaborators. To summarize, change networks bearing an active role in executing planned change are discussed in only three of the fifteen well-known planned organizational change models. In other words, classic planned organizational change models do not provide change networks with an extensive role, though their importance is recognized.

Setting these findings into a wider perspective in the study of planned change, there are few papers discussing change networks. Mohrman et al. (Citation2003) have studied different social networks’ roles in planned change, finding that the usage of existing organizational networks and the establishment of new networks facilitate planned change. Tenkasi and Chesmore (Citation2003), in turn, suggest that the density of networks of strong ties between change implementation and change recipient networks facilitates the implementation of large-scale planned organizational change. All the while, Bartunek’s (Citation2003) work on ‘change agent groups’ in organizational change in the education sector discusses the power of networks in change, though not labelling the ‘change agent group’ as a change network per se. More recently, Caldwell and Dyer (Citation2020) study a change network that emerged and was created for the implementation of a large-scale programmatic change in the telecommunication industry, using internal consultant teams. Despite these individual advances on network-type actors facilitating change, it deserves mention that networks actively dedicated and purposefully set in place for delivering planned change are not plentifully represented in extant academic literature. Change networks, therefore, deserve further study in the context of planned change.

Teams Dedicated to Planned Change

Teams are dynamic entities of two or more interdependent individuals who work together toward common goals (Kozlowski & Bell, Citation2003). To simplify concepts, in our paper we use the term ‘change teams’ to refer to teams with the designated task related to change, whether it be planning, implementing or other activities that are formally assigned to the team. Upon analyzing the fifteen planned organizational change models (), we observe that, as with networks, some models discuss change teams more than others. Some form of change team is visible in nine of the models. Taking a closer look, these can be subdivided into two categories.

For one, as with change networks, some models mainly mention change teams. For example, Carnall (Citation1990) mentions implementation teams and change project management teams briefly. Also, Senge et al. (Citation1999) discuss change teams by mentioning pilot groups in change implementation. Taffinder (Citation1998), in turn, associates the ‘change team’ with the senior management leading the change. Yet, these three models do not go deeper in the description.

For another, six of the models discuss change teams in more depth. From these, ACMP (Citation2020) describes change teams as groups of individuals working together, listing out several change management activities that a change team can bear responsibility for. Bridges (Citation2003), in turn, suggests temporary ‘transition monitoring teams’ to help in the transition. All the while, Dunphy et al. (Citation2003) suggest giving responsibility to business units and staff charged with the specific responsibility of organizational change. The model also suggests establishing a change co-ordination team. In their classic work, Peters and Waterman (Citation1982) suggest ‘chunking’, where task forces are considered as efficient means to solve problems and implement changes. Temporary project teams and project centres are deemed suitable regarding large-scale projects that need more administration. ‘Skunk work’ teams are considered as informal teams. Kotter (Citation1996), in turn, discusses in detail the creation of a winning coalition: a well-formulated team to make the planned change happen. Beckhard and Harris (Citation1977/Citation1987) state that it is often necessary to create temporary systems, meaning also teams, to accomplish change. These are called transition management structures, composed of various roles. All of the aforementioned six models discuss change teams by connecting their role to a specific change/transformation initiative, the composition of the change team varying by team and by model. The terminology varies, though. In addition to using the word ‘team’, models discuss change teams as ‘task forces’ and ‘skunk work teams’ (Peters & Waterman, Citation1982), ‘a [winning] coalition’ (Kotter, Citation1996), ‘change units’ (Dunphy et al., Citation2003) or ‘systems’ and ‘structures’ (Beckhard & Harris, Citation1977/Citation1987). Planned organizational change models, therefore, consider multiple differently labelled teams as bearing the task of change.

Yet, none of the studied models appear to treat change teams as a permanent part of the organization. Instead, change teams are created for temporary purposes and do not seem to exist ‘in the meantime’ (Beckhard & Harris, Citation1977/Citation1987; Bridges, Citation2003). In that light, it may even be somewhat paradoxical that while many of the models suggest using (temporary) change teams to facilitate a given planned change initiative, the authors nevertheless consider organizational change in general as permanent and ongoing (Beckhard & Harris, Citation1977/Citation1987; Bridges, Citation2003; Dunphy et al., Citation2003; Kotter, Citation1996).

In sum, we conclude that change teams are represented in many, yet not all, of the planned organizational change models from Rosenbaum et al. (Citation2017). These POCMs label change teams using varying titles, viewing change teams as temporary organizations, existing for the duration of a given planned change initiative. Yet, the role of permanent change teams is not visible.

Going a step further, some research regarding teams and change can be identified. Previous research has, for example, studied how teams are affected by and adapt to change (Koseoglu et al., Citation2017), as well as how teams themselves change (Johnson et al., Citation2013; Trainer et al., Citation2020). Pearce and Sims (Citation2002), in turn, have studied how different leadership styles predict the effectiveness of change management teams. In their study, Pearce and Sims describe change management teams (CMTs) as regards team composition, how the CMTs originated and what kind of leadership the teams have. All the while, Macdonald (Citation2003) describes the role of a change management team in a social-investment agency. In addition, change teams are also discussed from the perspective of change implementation teams (Higgins et al., Citation2012), defined as ‘a team charged with designing and leading the implementation of an organization-wide change strategy’. In turn, Theberge et al. (Citation2006) have studied a specific planned change team actively working with a specific change initiative. In these approaches, as with the POCMs from Rosenbaum et al. (Citation2017), permanent change teams do not seem to be covered. Teams with the task of change are considered as temporary, coexisting with a specific (planned) change initiative. While research on change teams in planned change exists, literature on permanent change teams is scarcer.

Active Individual Roles Dedicated to Planned Change

With the same fifteen planned organizational change models (Rosenbaum et al., Citation2017) previously analyzed from the viewpoints of change networks and change teams, we now present the findings of our analysis as regards individual’s roles dedicated to change (). We took into account only roles that have active responsibility in change execution, leaving out change recipient roles. We find that from the fifteen planned organizational change models, all but two of the models (namely, Kübler-Ross, Citation1969; Lewin, Citation1947) discuss individual’s active change roles. Taking a closer look, we identify three categories in relation to individual roles.

To begin with, in most of the planned change models, i.e. in ten models, the role of managers and leaders is emphasized (ACMP, Citation2020; Beckhard & Harris, Citation1977/Citation1987; Bridges, Citation2003; Carnall, Citation1990; Kotter, Citation1996; Nadler & Tushman, Citation1980/Citation1997; Peters & Waterman, Citation1982; Prosci, Citation2020; Senge et al., Citation1999; Taffinder, Citation1998). When discussing individuals, it thus seems that most POCMs associate the change role with individuals in management or leadership positions. It must be noted that depending on the model, managerial responsibilities with regard to planned change do vary depending on the level of the manager. There are differences from line managers to senior executives, with some models discussing managers on a more general level, while other models cover different managerial roles and levels more in-detail (Kotter, Citation1996; Senge et al., Citation1999). Regardless of the detailed roles and organizational level, most planned organizational change models present managers and leaders as bearing active roles vis-à-vis planned change.

Second, in addition to managerial roles, in nine of the models also other individual roles are mentioned. We observe that four of the planned organizational change models utilize the term ‘change agent’ to describe an individual who is actively responsible for change (ACMP, Citation2020; Bullock & Batten, Citation1985; Dunphy et al., Citation2003; Taffinder, Citation1998). Across the planned change models, many approaches and meanings are associated with the role of change agents. For example, Taffinder (Citation1998) discusses change agents as managers, while Dunphy et al. (Citation2003) consider various levels and roles for change agents. Furthermore, change agents seem to have distinct roles and tasks at different levels of the organization, while the descriptions of change agent roles and skills vary by model.

With other non-managerial individual change roles, ACMP (Citation2020), for example, lists multiple distinctive active roles such as those of the change management practitioner and change management lead. Product champions and executive champions are suggested by Peters and Waterman (Citation1982), while Taffinder (Citation1998) mentions champions and programme coordinators. In turn, Carnall (Citation1990) suggests a project management strategy with a change project management team consisting of different roles such as steering group, project manager, working parties, staff and management consultants. Additional supporting individual roles include the sponsor (ACMP, Citation2020; Taffinder, Citation1998) or godfather (Peters & Waterman, Citation1982) of a planned change initiative. In addition, Senge et al. (Citation1999) mention coaches and mentors. The previous all represent individuals’ active change roles associated with a particular planned change model and do not seem to appear in a multitude of models, although similar role descriptions may exist having divergent titles. As regards roles bearing similarity, Bridges (Citation2003), Senge et al. (Citation1999) and Carnall (Citation1990) all discuss the usage of external consultants.

Third, three models merely mention individuals’ roles. For example, Burke and Litwin (Citation1992) include individuals inside the ‘structure’ variable of their model. Bullock and Batten (Citation1985), in turn, briefly mention change agents and consultants, but the model does not discuss these roles more in detail. In the Prosci (Citation2020) model, change management teams using the suggested planned change model can consist of various active individuals.

Looking beyond these classic models of planned change, while the role of individuals has been researched from many angles, it appears that change recipient and managerial roles are the most prevalent, while the role of active employees, as well as, management consultants is also visible. First, individuals amid organizational change have been widely researched as change recipients, be it as regards the individual’s reactions towards change (Oreg et al., Citation2011, Citation2018), response and resistance to change (Piderit, Citation2000; Szabla, Citation2007), positivity and organizational change (Avey et al., Citation2008) and the individual’s emotions amid change (Castillo et al., Citation2018; Vince & Broussine, Citation1996). Throughout these approaches, the individual seems to be the subject to change: the one progressing through the ‘change curve’ (Kübler-Ross, Citation1969).

Second, there is a dichotomy between the roles of managers vs. employee participation in planned change, with the latter perspective gaining importance over the years. Indeed, the managerial or leadership roles in change are visible in the classic literature on planned change (Rosenbaum et al., Citation2017). In parallel, research has focused on employee participation in organizational change (Coyle-Shapiro, Citation1999), actors in organizational change (MacAulay et al., Citation2010), and employee readiness and participation in organizational change (Cunningham et al., Citation2002). Thus, achieving planned change depends on the participation of individuals at different organizational levels (Woiceshyn et al., Citation2020). Employee/individual active participation in organizational change can occur via numerous roles, although the importance of managers is often prioritized in the literature as compared with ‘low-power actors’ (Hyde, Citation2018) or frontline employees (Woiceshyn et al., Citation2020). With active roles that individuals have in planned change, it is worthwhile considering that in change implementation teams, it is possible for team members to withhold multiple memberships. For example, they can simultaneously be members of an implementation team and stakeholders being affected by change (Higgins et al., Citation2012).

Third, we find that the term ‘agent’ is widely used, often coupled with active individuals implementing change, as it is in four of the POCMs from Rosenbaum et al. (Citation2017). Westover (Citation2010) defines change agents’ tasks as follows: ‘the change agent's job is to develop a climate for planned change by overcoming resistances and rallying forces for positive growth’. Jones (Citation1969) describes agents in planned organizational change as change agents, change catalysts and pacemakers. The definition of the roles is not precise and all three can encompass groups, social constructions, behavioural units or individuals.

Fourth, in addition to employees, we note that management consultants are recognized in previous research. External management consultants and their role regarding organizational change have been researched from countless angles such as the dual roles of change consultants with organizational change and their respective consultancy firms (Shaw, Citation2019), power and symbolic roles that consultants carry (Kaarst-Brown, Citation1999), consultant-client relationships and knowledge transfer in change processes (Martinez et al., Citation2016) and many other advances.

In sum, research on individual roles in planned change has been researched via many angles, managerial roles and change recipients having the most visible presence. Roles such as change agents and external consultants are covered in previous literature, whilst research on employee participation is gaining importance.

Synthesis and Towards a Research Project

In sum, our review of prior research on planned organizational change and change organizations led us to the following conclusions.

First, change networks are recognized, albeit rarely studied in this literature.

Second, some of the planned organizational change models discuss change teams, albeit with varying terminology. All the while, these change teams are rarely provided robust roles in planned change. Furthermore, change teams are treated as temporary, existing for the duration of a specific change initiative. Permanent change teams are, to the best of our knowledge, not present in any of the classic models of planned change.

Finally, individual active change roles are given more prominence, as they appear in most of the classic models on planned change. Taking a closer look, it is often managers and leaders who are held primarily responsible for planned change. Other active individual roles vary by approach, with role titles bearing a multiplicity of meanings.

In synthesis, change organizations are mentioned, yet not thoroughly covered in prior literature of planned change. In order to further our appreciation of change organizations in times of planned change, in this paper we empirically explore change organizations with respect to the three aforementioned levels: (1) change networks, (2) change teams, and (3) individual roles.

Methods and Research Setting

Although this paper’s focus is on change organizations, our inquiry was part of a larger research project, where we explored change implementation processes across companies. When approaching our research question, we were faced with the question of how to embark on a journey where the data gathered would provide the best insight on the research question at hand. Consequently, the question was, how do we get from ‘here’ to ‘there’ (Yin, Citation1994)?

Qualitative research is suitable when searching for complex interrelationships among matters (Stake, Citation1995). Qualitative research acknowledges particularity and context, going beyond the ‘what’ to addressing ‘how’. The interpretation of data and events are key in order to pursue answers to our research question. Qualitative work often favours an inductive, interpretative approach that usually relies on multiple sources of information (Van Maanen, Citation1998; Yin, Citation1994). We felt that conducting a quantitative study might incorporate undesirable risks of leaving us with too many unanswered questions about companies’ change organizations, about the particularity of cases and would not take into holistic notion the contextuality of the research cases (the uniqueness of cases, Stake, Citation1995). That is why for us, qualitative research provided an excellent path.

The case study inquiry is considered a comprehensive research strategy itself, not merely a data collection tactic or a design feature. Case studies rely on multiple sources of evidence (with data needing to converge in a triangulating fashion). (Yin, Citation1994) Approaching the research question with real-life examples, namely case companies from the field as our units of analysis, seemed like the most suitable approach for carrying out our research. Case studies give weight to the rich real-world context where reality happens (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007).

Since we sought to obtain information from a wider audience compared to a single case, we adopted a multiple case study approach (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007; Yin, Citation1994) with individual companies as cases. Multiple cases can fortify the base for theory-building (Yin, Citation1994) and provide more ‘robust, generalizable and testable theory’ than single case studies (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007). Our study can be labelled as an embedded multiple case design (Yin, Citation1994) since we study multiple cases (companies) and within those companies, we have multiple levels of analysis (Eisenhardt, Citation1989), i.e. change networks, change teams and individual change roles.

Given the paucity of prior research on the subject matter, we adopted an inductive theory-building approach. Inductive methods rely on a grounded theory-building process (Eisenhardt et al., Citation2016) where theory emerges as a process. Inductive theory building from cases with rich empirical data is ‘likely to produce theory that is accurate, interesting and testable’ (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007). We used a grounded theory approach (Eisenhardt et al., Citation2016; Gioia et al., Citation2012; Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967), where we seek to gather knowledge on companies’ change organizations.

Data Collection

Inductive theory-building relies on theoretical sampling (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967), where cases are selected based on the perception that their ability is ‘to illuminate and extend relationships among constructs’ (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007). We selected the studied cases based on three principles. First, since investigating a relatively novel subject, as compared to a single case study, a multiple case design enables to ‘maximize what we can learn’ (Stake, Citation1995). Second, all the companies studied (the cases) represent different industries. The goal was to explore the possibilities for comparison and analytic generalization (Yin, Citation1994) between industries. Third, we expected that the country’s largest companies would have organizations dedicated to change. That is why we approached companies from the ‘top 100 largest companies in Finland’. This list is formed according to annual income and personnel number, based on Finnish Asiakastieto (Citation2020), i.e. customer information, ranking.

The research design consists of eleven case companies representing different industries, as per : infrastructure and building, telecommunications, food and consumer goods, airline, energy, facility services, chemistry, finance and insurance, private healthcare, retail and gaming and gambling. The original number of cases was thirteen, however, two organizations withdrew their participation before the first informant interviews. One organization did not see the research as fitting their agenda in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and the other organization’s contact person for the research left the organization before the interviews could start. Hence, the final number of studied cases was reduced to eleven.

Table 2. Overview of participant companies, industries and informants interviewed.

All case companies are large companies, with over 1,000 to over 20,000 employees and an annual income ranging from 500 million euros to over 1 billion euros. The studied companies were selected on the basis of bearing similar characteristics with respect to size, organizational set-up and operationality (see Appendix 1).

We deliberated on the most suitable mediums of data collection, deciding that interviews would serve us best in gathering information on companies’ change organizations. We wanted to delve deeper: to understand the change organizations actually responsible for change. Assuming that people in organizations ‘know what they are trying to do and can explain their thoughts, intentions, and actions’ (Gioia et al., Citation2012) was taken as focal point. We wanted to hear the informants’ interpretations, taking the role of ‘‘glorified reporters’’ (ibid) collecting the informants’ experience. Data was collected primarily via recorded semi-structured informant interviews of an open-ended nature (Yin, Citation1994), containing also close-ended questions. Our data sources consisted in (1) informant interviews, (2) companies’ documentation (with most companies but not with all) such as organizational charts, (change) process/programme descriptions, policies, scorecards, KPI-charts and project portfolio materials, (3) secondary sources such as company internet-pages, and (4) archival records such as old surveys about personnel satisfaction were displayed by some of the informants. Throughout the research, the data collected via interviews was the main source of information, since the documents were only shown and not physically handed to the researcher, as they were classified as confidential.

All data were collected by the first author. In total, the researcher interviewed 33 informants across the studied 11 companies (). Informants were selected to represent professionals best placed to help us understand each case company (Stake, Citation1995), i.e. individuals with knowledge of their company’s change organizations. As Eisenhardt and Graebner (Citation2007) affirm, using numerous informants from different levels and/or functions of the organization, provides data from a wider angle. Twenty-nine informants were interviewed individually, while four of the informants from the same company were interviewed in pairs due to informant requests amid tight work schedules. The interviews were organized over a time period of eight months (January–August 2020). The first third of the interviews were held face to face, yet due to the COVID-19 pandemic in spring 2020, two-thirds of interviews were held via video meeting tools. Informants were asked to reserve a 1.5 hours’ time-slot for the interview, although the duration of the interviews varied between one to three hours, depending on the informant and the time they were willing and able to allocate for the interview. With three informants, the interview was split into two sessions owing to time constraints.

The organizational levels of the informants can be seen in . A minimum of two informants per case company were interviewed, informants ranging between two to six informants per case company. Initial recruitment of informants was done either by (a) approaching a previous contact inside the company by e-mail or (b) directly approaching a previously unknown key decision-maker via e-mail. The informants primarily targeted were executives (executive board level or director level) who bore the term ‘change’, ‘transformation’, ‘development’ or ‘strategy’ in their respective titles. In companies, where the researcher did not have previous contacts and no change or transformation-related decision-makers could be identified from secondary sources, HR executives were approached. Inside case companies, a ‘snowball-method’ in recruiting informants was utilized. Recruitment of (further) informants per case company took place either via the first contacts or first interviews. In these instances, the primary contact person or informant provided a reference to (an)other person(s) who could be interviewed – i.e. persons who were working in change organizations or responsible for change in their respective companies. In three companies, the researcher presented the research agenda in more detail to the company representatives, before they agreed to proceed to informant interviews. The informant-researcher affiliations are presented in Appendix 2.

In informant interviews, rapport building and the relationship between researcher and informant bears a meaningful role. Informants were generally cooperative (Stake, Citation1995) and open towards our inquiry. On a practical level, rapport formation has usually been successful when the informant is relaxed and reassured of their role and confidentiality (Dundon & Ryan, Citation2010). Here, the relationship of the researcher and informant plays an important role. Concerning senior managers as informants, rapport building can be more affected also by practical matters, such as time constraints, or managers having knowledge of sensitive information that involves their roles personally (Laurila, Citation1997).

The nature of the themes and questions regarding change organizations were of two types. When beginning our inquiry, we started with open-ended questions, but we soon noticed that there is a need for close-ended questions in order for us to obtain the information needed regarding our research agenda. We acknowledged the fact that the process of building theory that is grounded includes not only data gathering but also adjusting data collection in real-time, in order to adapt to changing circumstances or requirements (Eisenhardt et al., Citation2016) and that the interview questions can change as the research advances (Gioia et al., Citation2012). Open-ended questions, such as ‘how do you see it, who is in charge of change in your organization’, provided us with descriptive and detail-rich answers. However, the explanations seemed to reflect the informant’s individual perceptions about the subject matter. Therefore, during the first interviews, we noticed that close-ended questions were also needed. Close-ended questions such as asking if an organization has ‘a formal change/transformation organization or organization dedicated to change/transformation’ provided us with straightforward ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answers and discussions. Additionally, we noticed that in order to obtain valid data, we had to stress matters such as formal change organizations meaning ‘persons or teams/units/functions/networks with scorecard/KPI responsibilities or as change/transformation stated and included in individual’s or team’s/unit’s/function’s/network’s role descriptions’. Having the most topic-suitable roles and functions in our informant pool and by interviewing multiple informants from the same case companies, the answers of informants to close-ended questions proved consistent.

Data Analysis

All interviews were recorded. After a first informant interview per company, an initial synthesis about the interview was made by the first author, reviewing the notes and the recording. This synthesis was reviewed before interviewing the next informant from the same case company. The synthesis provided initial observations and helped the researcher to see if some subjects were left unclear or missing. For instance, if an informant was unsure or did not exactly know about change roles in other units (which can be fairly common in large companies), the researcher made note of the matter and sought clarification from the next informant from the same company. The researchers discussed the syntheses jointly as informant interviews progressed.

When beginning with data examination (whilst still conducting interviews), based on the emerging findings, researchers jointly started to formulate an initial analytical framework with different categories and initial coding (i.e. first order coding, Gioia et al., Citation2012). As the research progressed, the classification and coding were adjusted accordingly – we soon noticed emerging themes, narratives and dimensions (i.e. second-order themes, ibid.). The role of the second author in examining the collected data enabled to look at the data ‘from outside’. Since the second author had not been interviewing informants, it was the data that was central – the perceptions were in no manner linked to informants or interview situations.

All gathered data from individual informant interviews was analyzed as follows. Since all the individual interviews were recorded, discussions could be transcribed from audio to a written transcript and timestamped accordingly. Transcribing individual informant interviews was the first round of data analysis, done by the first author. In the next round of analysis, the first author proceeded to compare different data sources with one another. During the transcription, the researcher reviewed her personal notes regarding specific interviews, comparing with recorded information and adding to the transcribed information. After transcribing all the informant interviews and reviewing notes, the researcher continued to the third round of data analysis by reviewing notes on other data sources (e.g. documentation such as organizational charts, (change) process/programme descriptions, policies, scorecards, KPI-charts and project portfolio materials), comparing notes on other data sources to the interview transcripts. As a result of these three data analysis rounds, the individual transcripts were enrichened. At this stage of the analysis, second-order themes (Gioia et al., Citation2012) had been ratified by researchers as a joint effort.

As a next round of analysis, we jointly proceeded from individual informants towards individual case companies. Interviews were disassembled one company (case) at a time, starting with data from company A, then data from company B and continuing on a case-by-case basis. This allowed comparisons and validations within a case company and the formulation of perceptions at a case level. Following Yin’s (Citation1994) suggestions, we first wanted to understand change organizations within one case. A central dimension in building theory from case studies is replication logic (Eisenhardt, Citation1989), where each case is a separate analytical unit.

Thereupon, in a final round of data analysis, we contrasted cases to one another. Comparison of the cases presented us with interesting findings regarding similarities, differences and patterns (correspondences) between cases. We looked for ‘meaning’ (Stake, Citation1995). At the cross-case level, we focused on explanation-building (Yin, Citation1994). This analysis led us to the next-presented three-fold typology as regards change organizations via change networks, change teams and individual change roles. In light of the inductive nature of our research design and data analysis, it is at this stage that we returned to the literature with more directed questions as regards how change networks, teams and individuals are presented in extant research on planned organizational change. This analysis features in the literature review section of this paper, in respect of an academic paper’s structure.

Change Organizations

As we proceed to present our findings, the reader is advised to refer to , which provides an overview of the three main thematic findings with respect to the studied companies’ change organizations (i.e. networks, teams, individuals) together with their empirical mapping in the 11 studied case companies. We proceed by sharing our findings by level of analysis (change networks, teams and individuals), also presenting identified sub-dimensions within each level of analysis.

Table 3. Case companies’ change organizations.

Change Networks

Formal change networks are networks with the dedicated task(s) of change. Whether it be communicating change, creating change, advising, engaging with operational matters or other named tasks – the purpose and tasks of change networks seem to vary across the case companies. As a subject of research, change networks proved to be an ambiguous topic for discussions because of the lack of formality associated with network-type structures and activities. So, what did we find? We found that five of the eleven case companies studied have some kind of formal networks dedicated to change (B, D, E, H and K – see ). All of these five case companies have different approaches towards change networks, their roles and tasks. We identify the following three dimensions that encompass the majority of the discussion on change networks’ features in these case companies:

breadth of the agenda from broad to narrow

clarity of roles from clear roles/tasks to unclear roles/tasks, and

composition of the network.

Breadth of the agenda. To begin with, the agenda of the networks varies from broad to narrow. Starting from broad, H is the only company with ‘general’ change agent networks not dedicated to a certain change agenda but toward all planned changes in the organization. This change agent network has multiple tasks: from communicating change to being part of creating the change, advising and doing hands-on change implementation tasks.

All the while, illustrating the narrow agenda, B, D, E, H and K use change networks dedicated to promoting specific planned change initiatives. Starting with company B, it has several change networks, all promoting certain change activities or certain change themes. There is no general-level change agent network. B’s change agent networks have various tasks, usually related to advising, communicating or hands-on operational tasks. Moving onto company D, it uses change agent networks to help in the implementation of certain on-the-spot changes, usually doing hands-on operational tasks at the grass-root level. D’s change networks are activated when needed and tasks assigned accordingly. As regards company E, the building of a change ambassador network was ongoing. The aim of the company is to harness this network in the promotion of change regarding a certain area of strategic change. The role and tasks of the network remain under discussion. In addition to their ‘general’ change network, company H has several change networks dedicated to driving specific change initiatives. Since the company’s structure is complex, multiple networks exist simultaneously – some fixed towards specific change programmes/projects and some towards changes in specific fields or domains (such as HR and finance). All of H’s networks have divergent roles and tasks, ranging from communications to advising and hands-on tasks. Company K, in turn, uses specialist networks to drive certain change agendas, mainly by communicating change. K has had change networks in the past, up to the point that some have felt change networks members being ‘everywhere’ or ‘too much’. K is in the situation where change networks may be scaled down or re-focused. While, their number is large, their roles and tasks lack clarity. In sum, the case companies’ identified change networks usually work for a specific initiative instead of supporting all change initiatives, s summarized by the following quote:

[Networks of] change agents are for specific projects but we don't have a ‘general’ change agent network. (Informant, Company D)

Clarity of roles and tasks. The role and the tasks of change networks seem to vary from clear role and responsibility descriptions (several networks in company H) to somewhat ambiguous definitions (company E and K), with most networks being somewhere in between. Tasks include for example communicating, creating change, advising or training others. Although the change networks discussed here are identified as formally set in place by the case companies, it proved to be moderately challenging for some informants to state the networks’ formal tasks or agendas. Change networks exist, but only the minority have a clear purpose and assigned responsibilities, as the next quote exemplifies:

Here, when discussing with you now, I realize that maybe we should be much better in describing the different roles and networks that we have supporting and doing change. (Informant, Company K)

Composition. The assemblage of individuals in the networks posits major differences between the studied networks. With some networks, members represent the same functions and/or organizational levels (H), while with other networks it is considered critical that members represent different organizational functions and/or levels (K). Some networks have members that are appointed top-down (H), while for others, members apply or express their interest to be part of the network (E). The composition of change networks does not appear to be systematic in studied companies, and network membership may not be precisely defined. H makes an exception, since the company has multiple change networks assigned to specific roles – the quote below illustrates their finance-focused change network:

… the controller network, that works very well. (Informant, Company H)

Although proving to be a somewhat challenging theme to grasp for case companies, formal change networks do exist and are used to promote, facilitate and drive planned change. After a thorough analysis of our data, we observe that multiple change networks exist in five of our case companies and that they vary within the three dimensions of breadth of agenda, role clarity and composition.

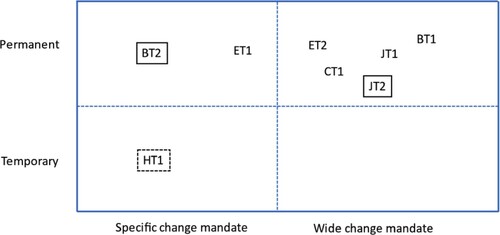

Change Teams

As regards change teams, five of the eleven case companies (B, C, E, H and J) have formal change teams in place (). Amid these five companies, we identified a total of eight change teams. A formal change team is a team (or equivalent) with the primary task of executing planned change. Taking a closer look at the five companies with change teams, we observed the nature of change teams to vary along three dimensions, which we discuss in detail below:

permanence of team, from permanent to temporary,

scope of mandate, from wider change mandate to specific change initiative(s), and

primary orientation of tasks, from consultative to operative.

Permanence. First, the identified change teams varied with respect to their permanent vs. temporary nature. Companies B, C, E and J support permanent change teams set up as formal parts of the company, yet each with a different approach. To begin with, in company B there is a small team (BT1) dedicated solely to business change management activities. This team supports change execution throughout the company, regardless of the nature of the change and the business unit ‘owning’ the change agenda. The team’s role is consultative. Due to the limited resourcing of this team, B’s informants noted that the business change managers tend to be utilized in larger-scale changes. Additionally, company B has a variety of formal teams driving certain change initiatives inside the company, such as initiative BX coaches (team BT2). These teams have more responsibility in operative work, such as training and coaching.

Moving onto company C, its different business lines have operated independently in executing change. That is why it has a team/function (CT1) set up with the purpose of streamlining and aligning the company’s change and transformation activities and systems. The team has only a few named resources, dedicated to supporting the implementation of large strategic change projects, and it has been relying extensively on the help of external consultants. Lately, consultant work is no longer actively utilized, and the team’s purpose is shifting from developing company C’s change management towards managing separate change projects.

Company E, in turn, has a mid-sized (5–10 persons) change team located in one business function (ET1). The team is fairly new, thus its scope of responsibilities are under development. The change team operates mainly in its own business function, which is considered important for the company’s strategy, yet the team aims to drive change throughout the company. The team’s task is to help change projects and programmes in implementing change. What this actually means remains blurry, according to the informants. Some informants describe the team’s and its members’ role as strategic or consultative, while others see it as hands-on undertaking operational tasks. The team’s purpose, therefore, appears to be under development. Additionally, company E has another small change team (ET2) comprising of members from the company’s other functions. This ET2 team works virtually.

In company J, there are change teams at different organizational levels, with different purposes. To this end, in the strategy function, there is a transformation team (JT1) dedicated to the implementation of strategy. The team advises programmes and projects on change management activities and coordinates strategic projects. Their role is supportive and consultative, working with a high-level overall agenda. Another team inside company J is dedicated to more operational tasks (JT2) such as training and coaching on change toward different change initiatives. JT2 works with different change programmes/projects and does hands-on activities in change execution.

Finally, case company H is the only company in our sample of companies with a formal temporary change team. The company has a large change programme ongoing since several years. Therefore, it has developed a business change management team (HT1) as a formal part of the overall organizational structure. The sole task of HT1 is executing and managing change regarding the aforementioned large change programme. This change team is formally set in place, though set for a fixed time. In summary, as regards the permanence of change teams, it seems that the large majority of the change teams in our study are set up as permanent parts of the company.

Scope of mandate. Based on our empirical data, the first dimension of a change team (permanent – temporary) affects its second dimension: the scope of the mandate (interrelation 1, as later illustrated with ). The studied change teams’ scope of mandate varies case by case, from a broader mandate over wide (company-level) planned change initiatives to a mandate over a specific planned change initiative. Furthermore, temporary change teams tend to cover specific initiatives, whilst permanent change teams work with a wider array of changes at strategical level, thus involved in so-called must win-battles (Killing et al., Citation2005) related to the studied companies’ strategy. It is thus that the permanent change teams BT1, CT1, ET1 and JT1 operate primarily with strategic company-wide agendas, with must-win battle initiatives, as illustrated in the quote below. In contrast, company H’s business change management team, the only temporary team in the cases studied, is devoted to serving only one major change programme.

There’s a lot of things that COULD be done and [change] projects but we focus on the biggest ones [must-win’s] currently. (Informant, Company E)

Task orientation. The third dimension relates to the range of tasks that change teams are responsible for. We observed that the tasks of change teams operate on a continuum ranging from ‘consultative’ to ‘operational’. Some change teams appear directed towards a strategic, high-level coordinative and advisory role (BT1, CT1, ET1, ET2, JT1). Although the tasks of individuals may vary within these teams, the teams bear identifiable primary roles and tasks. We have labelled some of the teams’ tasks as ‘consultative’, in the sense that these teams do not ‘do’ or operate, instead, they advise, as illustrated by this quote:

We take the lead in ‘this needs to be driven like this', there’s a structure around change management and you need to do it properly like that. (Informant, Company E (regarding team ET1’s role))

At the other end of the spectrum, there are teams describing their tasks as hands-on operational duties involving training, coaching, giving workshops, communications and facilitating change. For example, teams BT2 and JT2, in companies B and J, respectively, can be perceived to function at the operational end of the continuum. These teams carry out activities, thus they do not deal with strategic policies. With company H’s temporary change team (HT1), the business change management team can be labelled as hybrid, since it includes roles from both ends of the continuum.

Beyond formal change teams, the role of project-based teams deserves recognition. Case companies do not see programme or project teams as change teams as such, since the breadth of their agenda covers matters not related to change. All eleven companies have temporary project and programme teams built to deliver a certain end-result – usually some change – but the data gathered suggests that these temporary teams are project teams, not assigned with change (management) tasks at a team or functional level. This being said, these kind of programme/project teams can include individual roles assigned with the task of bringing forth change. In our definition, having an individual with the task of change in the project team does not make the team a change team as an entity. Individual change roles are covered in the next section.

During the interviews, some informants deliberated on the role of their project management office (PMO) and change teams. Here, the researcher proceeded by asking the informants to describe the tasks and mandate assigned to the company’s PMO. Five case companies have a centralized PMO function, whether situated under group functions or elsewhere in the company. In contrast, five companies do not have a PMO function, but do have individual roles dedicated to managing projects (either full-time or part-time), while for one case company, the information concerning their PMO is not available. Whatever the composition and resourcing, none of the eleven companies identified the project management office or PMO teams being dedicated to change or transformation. PMOs among the case companies were considered from an administrative viewpoint, as exemplified by the quote below from company C:

PMO was more about the ‘technical’ side of projects and managing the project itself, not so much change management. (Informant, Company C)

summarizes our findings from the five case companies having change teams.

Figure 1. Eight identified change teams from five case companies, illustrated as regards three dimensions. Permanent teams – temporary teams. Specific change mandate – wide change mandate. Teams with primary tasks of a consultative nature (not marked), teams with primary tasks of an operative nature (circled). HT1 as a hybrid organization.

As shows, a temporary change team with the mandate for a specific change only exists in one of the case companies. This contrasts with the view from the literature on planned organizational change models, which mostly discuss temporary change teams, set for a specific change. In contrast, our empirical evidence suggests that these types of temporary change teams are an exception, as permanent change teams represent the majority (seven teams out of eight) of the change teams in our sample of case companies. Notwithstanding, their ‘permanence’ can be debated since it can be argued that nothing is permanent. The building and scaling down of change teams connects to the strategy of the company: when pursuing major strategic objectives, change teams are set up. In many cases, such change teams result from executive board-level initiatives. Consequently, when new strategies emerge and/or executives leave and enter the company, teams can be terminated. We considered a change team as ‘permanent’, when the change team had no liaison to a certain change initiative: that is to say, no ‘expiration date’ for the team is set. It is also worth noting that in our cases studied, there was no identified change team(s) being temporary and having wide change mandate. Our results support the notion that temporary change teams are set up to cover for specific changes, wide permanent ones support a wider array of change.

In summary, while change teams exist in a minority of the cases studied, they nevertheless play important roles in their respective companies. Change teams can be temporary or permanent, having a mandate over specific or wide agendas and encompassing various tasks from operative to consultative. Most change teams in our company cases were set up as permanent. The resourcing of change teams appears to be scarce: in most of the companies change teams are small teams consisting of under five persons, although covering wide agendas and tasks. To finish, we note that change teams themselves change continuously within their mandate and range of tasks, as the quote below illustrates:

We started with big strategic programmes … Now we are doing strategic projects again, although they are at very large scope. I see a ‘risk' that soon we will become a PMO-function. (Informant, company C)

Change-Making Individuals

In this last section presenting our findings, our attention shifts to the individuals in charge of undertaking planned change. All case companies recognized the presence of individual roles for conducting change. Most informants spoke of this subject with enthusiasm. Descriptions were rich and vibrant. Many case companies did not have any difficulty identifying roles dedicated to change, while for some informants, it was not easy to identify any change roles at the very beginning of the conversation. Informants had a problem in naming the individual or individuals who were responsible of the change/transformation agenda inside the company, as the quote below illustrates. When an evident answer was not found, the finger was usually pointed towards the HR or strategy functions. We also noted that external consultants are often utilized in planned change initiatives.

As you can see, it’s a hard question to answer (Q: who is/are responsible for change in your company?). If the answer was clear, I would be able to give it to you straight away. The responsibility for change is very unclear … I guess that in theory it can be the business leaders or owners, I don’t know. (Informant, Company G)

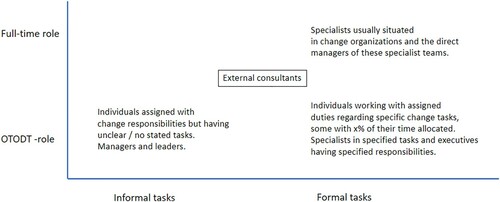

In all of the eleven case companies, individual roles dedicated for planned change were identified (see ). These roles varied substantially within four different dimensions, as regards the

priority of roles, from full-time roles to change being a task conducted on top of one’s daily tasks,

formality of roles, from formal roles to informal roles,

organizational level, from executive to specialist roles, and

origin of the roles, from internal to external roles.

We next cover findings as regards case companies’ individual change roles via these four dimensions.

Priority of roles. Companies with internal full-time roles dedicated to change are present in a minority of the companies in our sample. Four companies – B, C, E and J – identify full-time internal change roles in their companies, whilst six do not. Company H has a few full-time change roles in the company’s network consisting of mutually-owned companies. All the while, some companies did not identify any individuals full-time in charge of change, as the informant from company G observes:

We haven’t got a single full-time person named for doing transformation or change. Not a single resource. (Informant, Company G)

In contrast to full-time roles, on top of daily tasks-roles (OTODT) are roles where the individual’s primary role is not related to change. OTODT change roles can be found in all studied companies, as the quote below illustrates. All OTODT-roles are company internal roles. In these OTODT-roles, we seldom see time or other resources being allocated for task(s) as regards change. An exception is made by individual roles assigned to specific change programmes, projects or equivalent, where an individual is assigned to spend for example ‘10%’ or ‘40%’ of their working time on a specific change agenda (company H).

On a group level, we have no dedicated personnel in change implementation. It's always part of someone’s role on top of daily tasks. (Informant, group level, Company H)

Full-time internal change roles are likely to be situated in change teams: case companies B, C, E and J have internal full-time roles dedicated to change, while they also have formal change teams where these roles are situated. Our case studies thus show that when there is a permanent change team set in place in the company, full-time internal roles dedicated to change will presumably be located in that team (as later illustrated by interrelation 2 in : the dimensions of change team permanence and priority of individual change roles are interlinked). The ‘on top of daily tasks’ – roles (OTODT) are usually not part of change teams since individuals in these roles are not responsible for change full-time. Case company H makes an exception, since the company has a formal temporary change team set in place even though the change roles are mostly OTODT.

Formality. Individual change roles vary on a dimension from formal to informal. An important aspect of role formality is the link to the full-time position of the role. If the internal change role is full-time, responsibilities and tasks are articulated in job descriptions, task lists and targets. Thus, the role is formal. Individuals having internal full-time change roles know what they are expected to do on a daily basis. In our sample of companies, we did not find any full-time role, internal or consultant-based, dedicated to change, that would be informal (as later illustrated in : interlinkage between the dimensions of the priority and the formality of individual change roles).

With external consultant work, roles are formal. Tasks and responsibilities are described in contracts between the company and the consultant, yet there is variation in the level of precision in which consultants’ tasks or roles are articulated.

On top of daily tasks (OTODT) -roles can be either formal or informal. All OTODT-roles do however have at least some degree of assigned accountability (formality) for change since the change role can be identified. Nonetheless, most tasks assigned to OTODT-roles were described vaguely. The person assigned to the role has ‘some’ responsibility for change, but it may not be evident what the concrete duties are, thus the role is informal. Change is not part of the individual’s established requirements such as task lists, job descriptions or targets/KPIs. The question becomes, what do individuals in these, quite commonly present, types of informal OTODT-roles actually do? The answer is not easy, as the following quotes illustrate:

What comes to me, I have no idea what is the change that I should drive. (Informant 1, informal OTODT-role, Company D).

Additional (on top of daily tasks) roles work in some cases, like easy ones. But in more demanding cases, maybe not. (Informant 2, formal OTODT-role, Company D).

In some cases, the OTODT-role can be more easily labelled as formal: the role has clearly assigned responsibilities, although not being a full-time role. Formal OTODT-roles are present in specific change programmes/projects, where individuals have certain designated change responsibilities or tasks to do in the programme/project (like with company H’s temporary change organization HT1). These formal roles can also be visible via change networks.

Managerial roles are by far the most common informal OTODT-roles that our case companies discuss: all of the eleven companies state that managers and leaders have a crucial role vis-à-vis planned change and that they are expected to implement changes. Change is even seen as one of the main tasks of the manager, as the quotes below illustrate. Controversially, companies do not allocate these managers and leaders with clearly stated (formal) tasks, time resources, guidance, tools, methods and training on responsibilities regarding change. It is assumedly part of their managerial role.

The line manager’s role is extremely important to us and we do demand a lot from the managers. (Informant, Company B)

The manager’s responsibility (in implementing change) is crystal clear. We have put a lot of emphasis on this. (Informant, Company I)

Organizational level. Formal change roles are easier to grasp from an organizational level point of view. Since these roles are defined, they can be identified. A few formal full-time roles from our cases studied can be found at the managerial/director level, usually managing change teams consisting of specialists. Formal full-time change roles are most often specialist level roles, usually situated in change teams. External consultants appear to be predominantly located at the specialist level in the organization.

OTODT-roles are more arbitrary as regards their location and level in the organization. They can be found throughout the organization, from executive board (ExBo) to grass root specialists, with most of the roles being either at the managerial or at the specialist levels. Specialists with OTODT-roles usually work in change networks or in specific programmes/projects and tend to have more established assignments than managers, who are expected to secure/do/implement change on a more general level.

Most often, OTODT-roles are present at managerial and executive levels where the executive, director, manager or leader has declared responsibility to ‘make sure that change X gets done’, but simultaneously does not have formal resources or time allocated for the task. Three of the case companies’ informants (A, J, K) could identify an ExBo member assigned with the task of change. All companies stated that most of the ExBo members had ‘some’ accountability for change. The ExBo-members’ role was most often that of a sponsor in a specific change/must win battle, yet the role content was described ambiguously. In many cases, especially with informal OTODT-roles, the accountable person(s) for change can be hard to reach since no formal responsibilities and/or tasks are visible in the organization:

If I’m being honest, I would have no clue where to look for (help in executing change) when in need. (Informant, company C)

Origin. The last dimension of individual roles dedicated to change relates to the role’s origin. We found that change roles can be internally or externally resourced. ‘It is almost unthinkable for an organization to embark on a significant change initiative without seeking some sort of preliminary advice or expertise from consultants’, Caldwell (Citation2003) states. Coherently, we find that all companies in our sample revert to external help vis-à-vis organizational change. Consultants are assigned to different tasks regarding planned change, either working with a specific project/programme/equivalent or working with change at a more general, usually company-wide, level. They can be involved in change communications, change training/workshops/coaching, developing change tools, building change capability, creating change agendas and many other versatile tasks – depending on their contract. Consultant work can be used for a short time or a longer period, ranging to several years. Consultants can be full-time employees for the company or assigned for a few hour’s tasks. Whatever their individual roles and tasks, external consultants are utilized in planned change initiatives more often than internal staff – at least what comes to more formal change roles that are identifiable in organizations.

We noted that the attitudes towards external consultant work vary. Some of the sampled companies consider external consultants as helpful. These companies’ informants mention reasons such as keeping focus and priority in their own work, obtaining professional (consultant) assistance for change via methods and tools, and the possibility to adjust and allocate resources swiftly when needed. The below quote illustrates a positive attitude towards consultant work:

We use more external resources than our own. Before, we tried to do everything with our own resources but we noticed that our own resources may not always be the best. When big changes happen seldom, it’s worth taking someone that does these as their living - they probably have better knowledge. (Informant, company F)

The companies and informants who view the usage of external consultants negatively considered that the money spent on external help could be utilized to hire change professionals in-house. As the quote below illustrates, additional dubious aspects relate to the multiplicity of methods and tools, as each consultancy has their own. We identified doubts about the consistency of consultant work and worries related to the hand-over of work, when the consultants leave. Also, the idea that know-how remains outside of the organization instead of becoming in-house knowledge capital, is a source of concern.

We have had external people coaching change management matters since not having enough own people to do it. That leads to different ways of doing with different units and projects. One unit had an internal person helping them and the other hired an external consultant to help. (Informant, company C)

In synthesis, as regards the individual roles dedicated to change in our eleven case companies, the roles come in many forms. They can be either full-time or on top of daily tasks roles. They can be informal or formal roles, and the roles are present at all organizational levels from the executive board to the specialist level. Change roles can be internal or external. Regarding individual’s change roles, summarizes the findings.

Figure 2. Individual roles dedicated to change in eleven case companies, and the organizational levels where roles are most often present. Full-time roles – on top of daily tasks (OTODT)-roles. Roles having informal tasks – roles having formal tasks. External consultants can have multitudes of roles in companies.

As illustrates, individual roles dedicated to change are multifaceted. We have sought to group the different roles across their different dimensions. Although some variation surely exists, we see that case companies that have change teams in place seem to have internal formal change roles (full-time role and formal tasks) and thus, also internal resourcing for change. As said, we did not find a single internal full-time role dedicated to change that would be informal. Managerial roles are by far the most common on top of daily tasks-roles, usually coupled with vague task definitions (OTODT-role and informal tasks). These roles are provided little support and guidance, although they appear to be numerous. OTODT-roles with formal tasks seem to be associated with specific change initiatives and defined responsibilities and/or time allocation in executing these tasks. These roles are mainly occupied by specialists in specific change projects/programmes or executives in sponsor roles. We noticed the absence of full-time roles coupled with informal tasks. Although our conclusion may not be surprising, it makes a case for the fact that internal full-time roles dedicated to change seem to be quite formal: roles come with stated tasks, targets and job descriptions. Finally, all studied companies use uses external consultants to facilitate change. Consultants have varying tasks, usually on a specialist level.

Discussion

The aim of this paper was to discover what companies’ planned change organizations consist of.

While prior research in the field of planned organizational change is abundant, our review of the field led us to observe that there is little guidance as regards planned change organizations. Given the paucity of prior research on the subject matter, we adopted an inductive theory-building approach (Eisenhardt et al., Citation2016; Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007) with a grounded theory approach (Eisenhardt et al., Citation2016; Gioia et al., Citation2012; Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967), conducting a multiple case study of eleven large Finnish companies.

The main contribution of this paper is threefold. First, we present a typology of change organizations. Based on our review of the literature and empirical data, we define change organizations as change networks, change teams and individual change roles. We show that change organizations exist in companies, and that they differ via several dimensions. We demonstrate three interrelations identified between these dimensions. Second, we show that change organizations seem to be a somewhat underrepresented element in planned organizational change models (POCMs). We add to the theories of planned organizational change models by pointing out the role of change organizations, which we currently see as inadequately represented in contrast to what our empirical data suggests. Third, we offer a change maturity framework for beginning to assess the maturity of companies’ change organizations. We believe that our contributions facilitate further studies on the role of change organizations in planned organizational change, while also developing companies’ change organizations in practice. In the following, we discuss these contributions in greater detail, while this section ends by addressing the paper’s limitations and setting future research directions.

Change Organizations: A Typology

Based on the planned organizational change model literature and on the empirical data collected from our case study of eleven large Finish companies, we develop a typology displaying the main components of change organizations. These components consist of change networks, change teams and individual change roles. illustrates our typology of change organizations.

Figure 3. Change organizations. Components of change organizations: networks, teams and individuals. Dimensions of components. Interrelations (I) between dimensions are shown with arrows.