ABSTRACT

This article is the posthumous publication of a lecture given by the artist and academic Beth Harland (1964–2019). It was originally presented at a conference on Theatricality, at Lancaster University in 2017. This paper begins by working through the arguments of Michael Fried, to situate the key terms of theatricality and absorption, before then turning to contemporary painting practice (with notable reference to the work of Tomma Abts) to advance her reading of ‘an absorptive mode of address within contemporary painting’. This article also situates Harland's own art practice.

Introduction

I was fortunate to meet Beth Harland, 10 years ago, when I arrived at Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton. As was her way, she was immediately welcoming and we quickly struck up a friendship and working relationship. I tentatively mentioned my interest in the drawings of Roland Barthes, which she encouraged me to pursue. In talking together of Barthes (Citation2005) interest in the Neutral, I mentioned his brief note in which he describes spilling ‘neutral’ coloured Sennelier ink, a bottle of which I had on my desk. A day later Beth returned with a series of test strips which we pinned upon the office wall. It was this act (this makerly mode of enquiry) that marked the beginnings of an untold research endeavour and collaboration, even if perhaps in the manner of Flaubert’s comical copy-clerks, Bouvard and Pécuchet. Indeed, we had no specific idea of where we might take things, nor how we might best combine our approaches. Nonetheless, we made several trips to the Bibliothèque nationale de France to view the collection of Barthes’ drawings held there; we developed plans for their exhibition and we convened a dedicated panel for a conference marking Roland Barthes’ centenary. During this time, we also collaborated on a near-foolhardy project to collate over 100 critical writings for a 4 volume publication, Painting: Critical and Primary Sources (Harland and Manghani Citation2015).

When Beth told me she was leaving Winchester to take up a professorship at Lancaster University, I was both delighted and dismayed. I was delighted her acumen and commitment to art practice and education were acknowledged in this way, but equally, I was sad to think we would no longer be immediate work colleagues. Needless to say, we continued to collaborate; the aforementioned projects easily carried over to the new circumstance. I will always be deeply grateful to Beth. Her inimical enthusiasm and openness were a tonic at a time when I was needing to settle into the context of working at an art school. Despite having largely developed my work as a writer, Beth keenly sensed my background in painting and enduring love for the medium. Or perhaps, put another way, Beth always had a way of looking at the world in the ‘way of painting’. And she wanted always to share that vision, to enable others to see it too. On hearing the sad news of her passing, a colleague described Beth as having a wonderfully ‘generous laugh’. Like Barthes (Citation1982:, 75) beautiful definition of haiku (‘not a rich thought reduced to a brief form, but a brief event which immediately finds its proper form’), this always struck me as a perfectly formed portrait of Beth and her ethic of painting, reading, conversing. She was serious about painting, but ever generously, enlivenly so.

The giving of ‘life’ is a theme that emerges at the close of Beth’s text here on Michael Fried and contemporary painting, whereby she refers to how works of art can appear to have a life of their own, an emergent quality. In reference to paintings’ ‘self-organisation’, she seeks to secure an ‘absorptive mode of address within contemporary painting’. It is an account she builds through careful reading of Michael Fried’s (Citation1980; Citation1996; Citation1998) well-known terms of theatricality and absorption, which while typically the preserve of Modernism, are drawn together for an understanding of contemporary practice. A key point of reference is Tomma Abts. I still recall standing with Beth, surrounded by Abts’ paintings, in the opening room of the Tate’s Painting Now exhibition (2013-214; Wroe and Grant Citation2013). The curatorial note described Abts’ work as exploring the ‘possibilities of an abstract language of form. Her paintings emerge through a succession of intuitive, yet complex decisions guided by the internal logic of each composition’. As Beth points out in her text here, Abts would not consider her paintings as ‘abstract’, since they are not abstractions of something, rather they are the forming of image without origination. What I think absorbed Beth so much as we looked around the room was what she read there as a combined (almost simultaneous) force of decision-making and spontaneity. As Beth explains, what Abts’ wants (and achieved through this process) ‘is to keep the image “open”, still be resolved, ambiguous’.

Beth’s text should be read in dialogue with Ian Heywood’s article in the same issue of this journal. But, also, a third text to keep in mind is Beth’s last key publication, ‘Drawing in Atopia’ (Harland Citation2021). This text, which provides direct reference to Beth’s practice (see ), usefully expands upon the argument made here of the open work. The chapter begins with reference to ‘arche-drawing’, to describe what comes ‘before the binary oppositions of drawing and color’ (222). The initial reference is Matisse, whose work brings to the fore ‘core principles of a new kind of productive practice’, and what Beth refers to as a type of ‘space’ (222). More specifically, reading from Barthes, she sets out an account of ‘atopia’, as a form of drift or ‘an escape from the topic and the continual demand to make sense and act according to preconceived classifications. Atopia, from the Greek atapos, meaning “no-place” or “without-place”, is an open space of emergence’ (226). We can begin to discern not simply a practice of painting, but as much an ethics of painting, which Beth variously develops as a ‘way of looking’, an aesthetics of distractions, a diffusion of gaze. While Beth took painting seriously in the manner of the modernist (deeply engaged with form and modalities), her sense of the ‘space of absorption’ was always contemporary. Reminded again of her generosity, as well as her interest with Barthes’ concern for proximities, of learning to live together (Barthes Citation2005; Citation2013), her practice was always both a site of making (see ) and of reception(s).

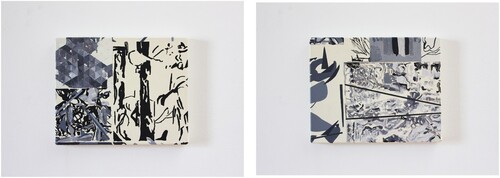

Figure 1. Beth Harland, Methods of Modern Construction, part 1, 2016, mixed media, 205 × 135 cm. © Collection of Artist.

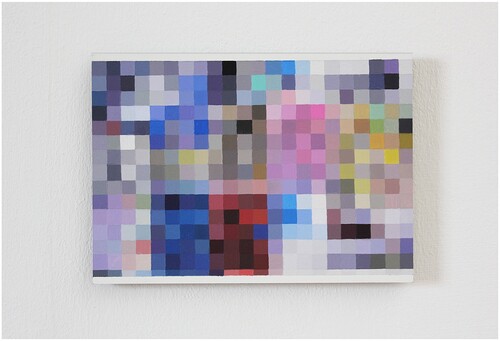

Figure 3 [Above and overleaf]. Beth Harland, Methods of Modern Construction, Part 3 (No. 1–3), 2016, oil on canvas, each panel 26 × 21 cm. © Collection of Artist.

Sunil Manghani

I will highlight two aspects of my series in order to explore how Matisse’s method and understanding of drawing/color have been influential. The first aspect is what Bois … has called ‘an aesthetic of distraction’, by which he means the disturbance of categories of center and periphery […] I have worked with this idea through building large wall collages from small, diverse elements, using color, image, and pattern in an unruly assemblage that challenges a settled orderly visual scanning of the work. This interest is in part a response to the sensation that in our digital culture it can be difficult to make center and periphery distinctions given the 24/7 access that we have in indescribable amounts of visual and other material online. (Harland Citation2021, 231)

The wall collage Methods of Modern Construction, Part 1, was built up piece by piece through small, varied components. These elements are exuberant in their use of color, eclectic materials and motifs. Many of them are loose re-workings of some of Matisse’s interior and studio paintings, which I flattened by removing color and tracing the images as a series of diagrammatic forms. […] Various reworkings of this collage followed: Part 2 of the work took the form of a digital wall collage presented on a small screen, similar in scale to the individual collage elements. The re-presentation of it as a screen image is again an action of removal from the origin and also introduces another form of attention and temporality, that of the digital realm. (Harland Citation2021, 233)

Part 3 rephrased passages from the collage back into small, precise easel paintings … They each focus on separate aspects of the original […] The parts of the work take different positions. Part 1 enters the energy, imagery, inventive spirit of early modernism, of particular iconic figures and works, and plays there, responding directly and intuitively. Part 2 begins to acknowledge the conditions of contemporary access, digital space and its impact on our relation to the origin of other works, of painting’s history. In a sense the screen version is a provocation, as well as an alternative origin. Part 3 takes an analytical position, requiring distance. These paintings have a documentary feel, a different presence, contained, and concise. […] In my action of revision there is movement from loose, intuitive making processes through to studied reworkings that are concise, mysterious to read, withheld as signifying objects. The modernist origin becomes a kind of screen/layer over the present. It is here that drawing as a generative category reveals a particular form of attention … (Harland Citation2021, 233; 234)

What I want to propose is a space to digress and test, won through a form of drawing that can take on a ‘drifting’ orientation, a type of wandering that might counter the tendency for the work to close itself and its dialogue with other works too quickly or completely. […] Returning to Barthes’s idea that artists are working on an already ‘coloured’ surface seems appropriate – I deliberately work with the archive of modernist painting but not always in a direct and identifiable way. This sideways glance at the sources seems to me to make up a meaningful originary structure – a necessarily loose structure – for a current practice. (Harland Citation2021, 235)

Michael Fried’s theatricality and the practice of painting

The dominant figure in discussions of theatricality as a critical term in the visual arts is Michael Fried, who explores the term, along with its paired opposite absorption, from the perspectives of art historian and art critic. As an art historian, his key text Absorption and Theatricality: Painting and the Beholder in the Age of Diderot (1980), is a study of eighteenth-century French painting. Fried identifies an anti-theatrical, anti- Rococo revolution evident in paintings and critical commentaries of the time, in particular the Salons of Denis Diderot. For these commentators Rococo painting had become unbelievable or untenable; works by for example François Boucher seemed ‘staged’, ‘mannered’, too self-consciously enticing to arrest, attract and engage the viewer. What was shown to the viewer –with little subtlety– by the artist was less believable than what the beholder might prefer to have actively seen, or found, for herself. The sense of having actively sought and seen something is more convincing and arresting than the suspicion of having been spoon fed.

The emerging anti-theatrical strategy associated with Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Jean- Siméon Chardin and others rested on the counterfactual view that paintings are not made to be seen by a beholder. In absorptive paintings figures typically do not engage the viewer’s gaze. They are represented as engrossed in a task or as mentally at one with the scene in which they are viewed. In other words, they appear absorbed in a world of their own, not displayed, or displaying themselves, as a spectacle for the delectation (or edification) of the viewer. Paradoxically, to ‘arrest’ and ‘enthral’, the painter adopts the ‘supreme fiction’ that the viewer did not exist, and as the century wore on, ever more extreme strategies proved necessary to negate the very possibility of beholding. Although there is no space to pursue it here, in After the Beautiful the philosopher Robert Pippin explores a general crisis of meaning emerging in the late nineteenth century, with social dimensions as well as different artistic and cultural expressions. Pippin sees Hegel as providing the best available account of this crisis of intelligibility. Related views of historical crisis and response appear in works by Fried and T. J. Clark. (For a report of a relevant exchange of views on this and related matters see Pippin Citation2005 and Citation2014.)

Absorption and Theatricality was widely praised for its impeccable scholarship and fresh insights. Fried emphasized that his approach at this point was unambiguously art historical, not critical; for example, he says there are no fixed pictorial features that would determine once and for all whether a painting was absorptive or not. Judgements of competent observers, including artists themselves, could and often did change over time. Hence, the art historian must be alert to shifts in sensibility and frameworks of interpretation and evaluation. Yet tensions between Fried the historian, Fried the critic and Fried the philosopher surface periodically in his writing. We note at this point that Fried’s thoughtful, observant attention to actual works is often in tune with a kind of thinking attuned to painting and its criticism; he does not simply treat them merely as reflections or concrete instances of schematic, high-altitude concepts, like social relations, ideology, episteme or epoch.

We now need to go back to Fried’s earlier, 1960s incarnation as an art critic. In a series of articles and reviews Fried defended the abstract painters Frank Stella, Larry Poons, Jules Olitski, Kenneth Noland and the sculptor Anthony Caro, and vigorously attacked the emerging minimalist or what he called ‘literalist’ work of artists such as Donald Judd and Robert Morris. In his essay ‘Art and Objecthood’ (1968) he accused the minimalists of arranging for the audience an intense perceptual experience that ‘solicited and included the beholder’ in a manner that the anti-theatrical work he most valued did not. And here we do see the terms marshalled to support critical judgements. Although minimalist sculpture was devoid of figurative or narrative interest Judd, Morris and other minimalists were highly accomplished at scene-setting and perceptual orchestration, that is, at theatrical effects. At the core of minimalism was an attempt to visualize and skilfully present or stage ‘pure objecthood’, a bare abstraction that had the look of ‘non art’, the appearance of art having become, for various reasons, unappealing to advanced tastes.

What precisely Fried saw as the ontological, aesthetic or moral character of the abstract works he defended is less easy to say; there is relatively little about ‘absorption’ in ‘Art and Objecthood’. A closing passage, however, notorious for some of his critics, describes them as having ‘presentness’ and ‘grace’ (Fried Citation1998, 167–8) and speaks of their need to compel ‘conviction’, in particular that they could stand comparison with the great art of the past (ibid: 165). It is not obvious that this helps, as convincingness and canonical quality would surely be the results of ‘presentness and grace’, not their explicans. This critical controversy was of course a long time ago. Yet for some of Fried’s many critics, Rosalind Krauss and Hal Foster among others, it marked a sputtering final defence of high formalist modernism. Today, when postmodernism is no longer fashionable, questions about early and high modernism, their nineteenth-century origins and contemporary significance, have reappeared.

We need now to mention a later historical study relevant to Fried’s idea of theatricality, specifically how theatricality and absorption relate to a decisive moment in the development of modernism in the visual arts. In Manet’s Modernism (1998), Fried argues that Manet exhibited an ‘extreme response’ to the mid-nineteenth century crisis in the anti-theatrical tradition. In a way baffling for his contemporaries, and still challenging, Manet’s paintings simultaneously affirm and deny the presence of the beholder. Manet’s radical move was the construction a new mode of address Fried calls ‘facingness’, works that are simultaneously anti-theatrical and theatrical by ‘building into the painting separateness, distancedness and mutual facing … ’ (Fried Citation1998, 263). While utilising absorptive mechanisms, there is nevertheless a direct acknowledgement of the beholder’s presence. Manet’s theatricality is different from that of popular salon pictures of the day. It was, as Fried puts it, the attempt to ‘make the painting in its entirety – the painting as a painting … face the beholder as never before’ (ibid: 266) and in so doing, make them aware of the painting-beholder relationship.

Manet’s struggle against traditional absorptive closure resulted not only in innovations in composition. For example in paintings such as Le Dejeuner sur L’herbe rather isolated figures are juxtaposed in ways rendering their relationship incomprehensible to audiences of the day, but also new forms of execution, the ‘flatness’ and speed we see in the paint handling, the tension created by the juxtaposition of movement and stillness. In other words, the opaque or withheld relations between figures in the paintings, and between different passages and features of the painted surface, spreads to that between the audience and a dislocated, obdurate work and, by implication, to the reflective self-relation of the viewer herself. Together these innovations point towards two further terms used by Fried to develop an understanding of this new mode of address: ‘strikingness’ and ‘instantaneousness’. Drawing upon the influences of photography and Japanese woodblocks, the sharp contours and lack of modelling in Manet’s paintings contribute to their ability to ‘strike’ the beholder. This then is a different method for arresting and holding the viewer, and as such is Manet’s alternative to how traditional painting had used an absorptive mechanism to achieve significance.

The medium of photography has become the focus of Fried’s (Citation2008) much more recent application of his analysis of absorption and theatricality. In Why Photography Matters Now As Never Before (2011) Fried, with clear relish, seizes on the opportunity presented by the development of large tableau format photography from the 1980s onwards, to connect the preoccupations of artists such as Jeff Wall and Thomas Struth to the anti-theatrical pictorial tradition of eighteenth and nineteenth-century painting.

Against this background, we have chosen to try and say something about the application of the idea of theatricality to contemporary painting, for three reasons. Painting was largely what Fried was concerned with in his early criticism and art history, although noticeably less often in his work on contemporary visual art. Fried’s account of eighteenth and nineteenth-century French painting does, however, cast light on modern and contemporary developments in visual art generally. Finally and more pragmatically, concentrating on painting, rather than the profusion of styles, media and approaches in today’s visual culture, makes things a bit more manageable.

Is Fried’s theatricality a useful notion when applied to current painting? This needs a caveat. In speaking about practices of painting it often seems best to concern oneself with individual works and artists. But then, inevitably, generalizations about the ‘state of painting’, painting sui generis, or even about its predominant styles, seem to become too abstract, less persuasive. Who and what could represent painting now? The tactic adopted here is to identify prominent and influential painters of recent years and then add to these sample painters who are good examples of particular approaches. Examples of the former might include Gerhard Richter and Luc Tuymans, and of the latter Tomma Abts, Amy Sillman and Jacqueline Humphries.

With these bodies of work in mind, how useful is theatricality? At first glance, not very. One obvious reason why this is so is that Fried’s examples in Absorption and Theatricality are figurative works, many with religious, moralistic or sentimental content alien to contemporary tastes. Tuymans’ and Richter’s interest in recent history –the aftermath of Belgium’s imperial adventures in Africa and World War II for example – and the derivation of their imagery from photographs and films is very distant from those of the Fried’s eighteenth century painters. The works of Sillman, and Humphries are abstract or semi-figurative, plausibly comparable to the abstractions of Fried’s 60s heroes, but even then their self-conscious remaking of modernist gestures and in some cases their vigorous eclecticism seem remote from the projects of those artists.

We want to suggest, however, that a cluster of notions related to theatricality and absorption do appear potentially more useful. We noted above that as a historian Fried does not tie absorption and theatricality strictly to overt pictorial features, such as whether or not figures have their backs towards the viewer or gaze fixedly at one another, although admittedly he is often on the lookout for such things outside their original eighteenth-century setting. Even in Fried’s usage, then, there is precedent for treating these notions somewhat loosely. With this in mind, we offer an elaboration of linked and contrasting ideas related to theatricality and absorption as the foundational terms of Fried’s criticism.

There isn’t space to explain all of this in detail, but some of the terms reappear in Fried’s treatment of examples of contemporary art in his Four Honest Outlaws (Citation2011) and his article ‘Sala with Schiller: World, Form, and Play in Mixed Behavior’ (Citation2012). A brief look at what Fried says about this video by Anri Sala and paintings of Joseph Marioni serve as a preface to our discussion of paintings by Tomma Abts.

Sala’s Mixed Behaviour confronts the viewer with a shot of a nocturnal cityscape, the sky filled with the sights and sounds of fireworks. Close to the camera is a sound rig covered by a tarpaulin onto which rain patters. A DJ seen from behind enters and pushes his way under the covering. As fireworks go into reverse and take on the rhythms of the music we realize that the display and the sounds are coordinated; the DJ may be somehow orchestrating, or mixing, the display itself. Once again there are Fried’s favoured signs of absorption, shots from the back, the DJ’s obliviousness of the viewer, as well as an overt structuring – aesthetically satisfying and evocative – imposed on otherwise contingent or indexical sounds and sights recorded by microphone and camera.

The relation of Marioni’s mainly monochrome canvasses to the earlier colour field painting of Rothko, Still, and Newman, and later work of Robert Ryman and Bryce Marden, is clear. In a review of Four Honest Outlaws Brendan Boyle (Citation2012) writes that Marioni’s ‘astonishing discovery’ is that ‘paintings like this can still be made.’ He quotes Fried to the effect that in these canvases exposure to colour is extended and intensive, in a way without limit, yet ‘fitted perfectly’ to the shape of the support.

Fried’s excursions into contemporary art deal with photography and video more frequently than painting, and in the case of Marioni the continuity of approach and style with 60s abstraction puts little pressure on his critical categories. What happens if we turn to another, more recent non-figurative painter: Tomma Abts? It will have become clear by now that it is possible to pursue the topic of theatricality too narrowly. Theatricality and absorption belong to a group of aesthetic and moral ideas that constitute the field of cultural values which Fried advocates. So, rather than crowbar theatricality into our encounter with Abts it seems best to look at and reflect on her paintings in light of a broad approach to Fried’s critical framework.

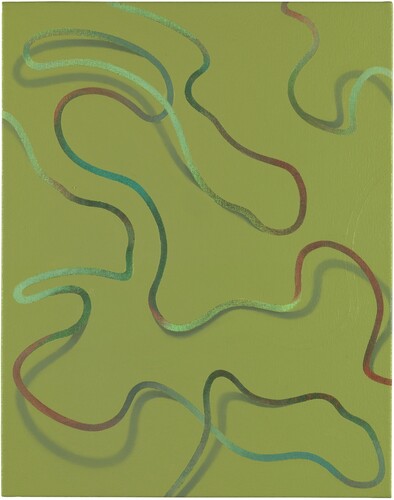

Compared to Marioni’s canvasses those of Abts are relatively small, her favourite dimensions being 48 cm × 38 cm. Their portrait (vertical) orientation suggests the setting up with the viewer of a sort of portrait encounter. These are certainly not undifferentiated monochrome paintings, but typically made up of intricately interlocking, overlapping or juxtaposed strips, bands and areas of colour. The viewer can see in Abts’ paintings signs of earlier stages carefully integrated into later ones, and these traces of a history of the changing appearance of the painting through the preservation of otherwise transient details suggests something akin to the working of memory (see ).

Figure 4. Tomma Abts, Lüür, 2015, acrylic & oil on canvas 48 × 38 cm (18 ⅞” × 15”). Private collection. Photo © Marcus Leith. Courtesy of the Artist and greengrassi, London.

Abts does not consider her paintings to be ‘abstract’ because she is ‘constructing an image from nothing’ but also trying to ‘define it very clearly, so it becomes legible.’ In a largely spontaneous process of painting she says: ‘I define shapes more clearly and add other elements, for example: outlines, stripes or shadows, to create lots of possibilities. A long phase of trial and error commences.’ (Abts in Wroe and Grant Citation2013). Abts often defines what appear to be ‘positive’ shapes by painting around them, and while she seeks to trace out and follow an emerging logic to a conclusion as forms are set down, submerged and rediscovered she also wants to keep the image ‘open’, still to be resolved, ambiguous.

It is not that the laboriousness of the process (or its sincerity) that encourages us to believe in what we see, that ‘arrests’ and ‘convinces’, to use Diderot’s terms. Labour and skill can fail. Here it is the capacity of what we see (the visible painting, the result) to persuade us that the painting is ‘organizing itself’, suggesting a world coming into being, a world taken-up or absorbed in its emergence yet vividly appearing in ours. We know this to be a fiction of course, but it is another way of saying that we do not feel that a ‘product’ has been made based on some idea of what ‘needs to be made’ or the application of an existing template. In Abts’ case, this coming into being of the work applies to the surface, the image and the object; this is certainly not Fried’s ‘bare objecthood’. In coming to be seen as self-organized, retaining traces of its past but being open to new possibilities, the work seems to have a ‘life’, as Jan Verwoert (in Buchholz and Müller Citation2005) describes it, an ‘emergent’ quality, the product of many decisions as the painting continually constructs its own criteria. As such ‘the picture itself produces an awareness of its crises and contradictions’(ibid: 48). Here perhaps there is the echo of an absorptive mode of address within contemporary painting.

To conclude, we set out to trace some of the twists and turns in Fried’s application of a notion of theatricality to visual art. We have seen that theatricality and absorption as historical and critical terms are most at home in the period for which Fried devised them, although theatricality was also central to his earlier criticism. Fried has applied both terms to recent photography and video, although rarely and then largely conservatively to contemporary painting. We have also highlighted a group of ideas that articulate Fried’s larger philosophy, with its views on art, authenticity, rigour, modernism and so on. While theatricality and absorption cannot be applied so literally to an example of current painting practice such as that of Tomma Abts, some of these broader ideas, in conjunction with the observant and thoughtful criticism displayed by Fried at his best, do yield worthwhile insights and productive questions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Beth Harland

Beth Harland (1964–2019) studied at the Ruskin School of Art and the RCA before completing her PhD at the University of Southampton. She was an associate lecturer at Central St Martins, a senior lecturer at Winchester School of Art and latterly a professor of Fine Art at Lancaster University, as well as an associate editor of the Journal of Contemporary Painting. Her research interests included: pictorial modes of address and spectator experience; painting and digital imaging and notions of temporality in art. Exhibitions of her work included Impermanent Durations; On Painting and Time, at the Institute for Contemporary Art, Singapore, the Bundoora Homestead Arts Centre, Melbourne and the Peter Scott Gallery, Lancaster.

Sunil Manghani is a professor of Theory, Practice and Critique at Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton (UK). He is a co-editor of Journal of Visual Art Practice, a managing editor of Theory, Culture & Society, and a fellow of the Alan Turing Institute. His books include Image Studies (2013), Zero Degree Seeing (2019); India’s Biennale Effect (2016) and Farewell to Visual Studies (2015). He curated Barthes/Burgin at the John Hansard Gallery (2016), along with Building an Art Biennale (2018) and Itinerant Objects (2019) at Tate Exchange, Tate Modern.

References

- Barthes, Roland. 1982. Empire of Signs. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang.

- Barthes, R. 2005. The Neutral: Lecture Course at the Collège de France (1977–1978). Translated by R. E. Krauss and D. Hollier. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Barthes, R. 2013. How to Live Together: Novelistic Simulations of Some Everyday Spaces. Translated by K. Briggs. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Boyle, Brendan. 2012 ‘Outside the Law: Michael Fried’s “Four Honest Outlaws”’, Los Angeles Review of Books, January 20 2012. Accessed September 2017. https://lareviewofbooks.org/contributor/brendan-boyle/#.

- Buchholz, Daniel, and Christopher Müller, eds. 2005. Tomma Abts. London: Galerie Daniel Buchholz, Cologne; greengrassi. See also archive of articles about Abts kindly supplied by greengrassi (TA_selected texts_e.pdf).

- Fried, Michael. 1980. Absorption and Theatricality: Painting and the Beholder in the Age of Diderot. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Fried, Michael. 1996. Manet’s Modernism or The Face of Painting in 1860s. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Fried, Michael. 1998. Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Fried, Michael. 2008. Why Photography Matters as Art as Never Before. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Fried, Michael. 2011. Four Honest Outlaws: Sala, Ray, Marioni, Gordon. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Fried, Michael. 2012. ‘Sala with Schiller: World, Form, and Play in Mixed Behaviour’, Nonsite. Accessed September 2017. http://nonsite.org/article/sala-with-schiller-world-form-and-play-in-mixed-behavior.

- Harland, Beth. 2021. “Drawing in Atopia: An Exploration of “Drift” as Method.” In A Companion to Contemporary Drawing, edited by Kelly Chorpening, and Rebecca Fortnum, 221–237. London: Wiley & Sons.

- Harland, Beth, and Sunil Manghani, eds. 2015. Painting: Critical and Primary Sources. 4 vols. London: Bloomsbury.

- Pippin, Robert B. 2005. The Persistence of Subjectivity: On the Kantian Aftermath. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pippin, Robert B. 2014. After the Beautiful: Hegel and the Philosophy of Pictorial Modernism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Wroe, Nicholas, and Simon Grant. 2013. ‘Why painting still matters’ (Interviews), The Guardian, November Friday 8, 2013. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/nov/08/why-painting-still-matters-tate-britain.