ABSTRACT

This paper examines the roles of different language ideologies—sets of common-sense beliefs about language and its speakers—in students’ identity construction and negotiation in the context of internationalizing higher education. Along with the increasing diversity of students as English speakers, language ideologies have been critically examined for potential contribution to inequalities among students. I analyze two focus group discussions of students from international English-medium instruction master’s programs at a Finnish university. I explore the students’ talk using critical discursive psychology to illuminate possible intersections between language ideologies and students’ situated identity construction, paying attention to ideological dilemmas alongside students’ identity negotiation. The findings indicate that both emerging and established language ideologies may become relevant to students’ identity construction and negotiation. Possibly, turning students’ attention towards the multilinguality of every student and the specific purposes and characteristics of academic language might contribute to the discursive sustainability of inclusive interpersonal relationships among students.

Tässä artikkelissa tarkastellaan eri kieli-ideologioiden—eli arkisten kieltä ja sen puhujia koskevien uskomusten—rooleja opiskelijoiden identiteetin rakentamisessa ja neuvotteluissa kansainvälistyvän korkeakoulutuksen kontekstissa. Englanninkielisten opiskelijoiden lisääntyvän monimuotoisuuden myötä kieli-ideologioita on tutkittu mahdollisena opiskelijoiden välisen epätasa-arvon rakentajana. Analysoin kahta fokusryhmäkeskustelua, joiden osallistujat ovat erään suomalaisen yliopiston kansainvälisten englanninkielisten maisteriohjelmien opiskelijoita. Tutkin opiskelijoiden puhetta kriittisen diskursiivisen psykologian avulla tarkoituksenani ymmärtää mahdollisia yhtymäkohtia kieli-ideologioiden ja opiskelijoiden identiteetin rakentamisen välillä. Kiinnitän erityisesti huomiota opiskelijoiden identiteettineuvotteluihin liittyviin ideologisiin dilemmoihin. Tutkimuksen tulokset osoittavat, että sekä uudet että vakiintuneet kieleen liittyvät ideologiat voivat tulla merkityksellisiksi opiskelijoiden identiteetin rakentamisessa ja neuvotteluissa. Pohdin, kuinka opiskelijoiden huomion kiinnittäminen jokaisen opiskelijan monikielisyyteen ja akateemisen kielen erityisiin tarkoituksiin ja ominaisuuksiin saattaa edistää opiskelijoiden välisten osallistavien vuorovaikutussuhteiden diskursiivista kestävyyttä.

Introduction

This paper examines the roles of different language ideologies in students’ identity construction and negotiation in the context of internationalizing and Englishizing higher education. Language ideologies are, simply put, sets of common-sense beliefs about language and its speakers that might contribute to inequalities by hierarchically categorizing people into different linguistic groups (Woolard & Schieffelin, Citation1994). With the growing diversity of students as English speakers, the notion of English as a lingua franca has been increasing its presence in higher education. This notion defies the taken-for-granted idea of reserving the authenticity of English for those who are recognized as speaking English as the first language, the so-called ‘native speakers’ of English (see e.g. Björkman, Citation2011; Jenkins, Citation2014). People get labeled as ‘native’ or ‘non-native’ speakers of English based on their membership or non-membership in English-speaking national or ethnic communities rather than their proficiency in English (see Doerr, Citation2009). It would be reasonable to challenge the utility and legitimacy of the categories of ‘native’ and ‘non-native’ speakers in higher education, where students’ language proficiency is most likely concerned. Nevertheless, even in Nordic universities, many of which are major providers of international English-medium instruction (EMI) programs (Henriksen et al., Citation2019), ‘native-speaker’ norms of English are prevalent in not only university language policies (e.g. Saarinen & Nikula, Citation2013) but also students’ discourses (e.g. Kuteeva, Citation2014; McCambridge & Saarinen, Citation2015).

This current coexistence of the conflicting views of English in internationalizing higher education makes me ponder the possible meanings of different language ideologies in interpersonal relationships among students. Language ideologies are, in principle, matters of intergroup relations, in that they provide social categories by mediating between ideas about language and people (Woolard & Schieffelin, Citation1994). However, these ideologies may also be consequential to interpersonal relationships because membership in social categories can become part of a person’s identity through interaction (Stokoe, Citation2012). Bucholtz and Hall (Citation2005) propose approaching ‘identity as a relational and socio-cultural phenomenon that emerges and circulates in local discourse contexts of interaction rather than as a stable structure located primarily in the individual psyche or in fixed social categories’ (p. 585–586). Furthermore, in shedding light on the intersection between intercultural communication and lingua franca communication (especially in English), Zhu (Citation2015) argues that people are likely to negotiate their national or ethnic identities when interacting with others in a lingua franca. It is therefore meaningful to address language ideologies with respect to identity construction and negotiation of students in international EMI programs.

In this paper, I analyze two focus group discussions of students from international master’s programs at the University of Jyväskylä in Finland (JYU) through the lenses of language ideology and identity. This specific Nordic university was chosen as a research site because, through the university’s active incorporation of recent findings in applied linguistics research into its language policies and practices, JYU students are likely to be exposed to emerging as well as more established language ideologies. I am interested in different kinds of interpersonal relationships among students being collaboratively created through language ideologies as the students talk in small groups. The discussion theme was interpersonal relationships among students in the participants’ programs, in connection with language practices and proficiency. I analyze the students’ talk using critical discursive psychology to illuminate possible intersections between language ideologies and students’ identity construction. I pay special attention to ideological dilemmas—dilemmas among different co-occurring ideologies—alongside students’ identity negotiation. The findings will enhance our understanding of how students may navigate their interpersonal relationships with their peers in international EMI programs of higher education today. The research questions are: (1) What language ideologies become relevant to students’ discursive construction of their identities in international master’s programs at JYU? (2) How do the students negotiate their identities when an ideological dilemma occurs?

Theoretical framework

Given that what we label as intercultural communication can be inherently multilingual (see Piller, Citation2011), people’s linguistic practices, repertoires, and backgrounds are expected to be crucial in intercultural communication. I therefore recognize the importance of exploring language ideologies in identity construction from an intercultural communication perspective, and this paper demonstrates one way of doing such an exploration.

Language ideologies, intergroup relations and interpersonal relationships, and identity

With a critical view of the role of language in the social world, Irvine defines language ideology as ‘the cultural (or subcultural) system of ideas about social and linguistic relationships, together with their loading of moral and political interests’ (Citation1989, p. 255). Language ideologies may explicitly or implicitly inform us of ideas about who should be using what language and how, in terms of characteristics, roles, status, rights, obligations, and affections (Kroskrity, Citation2010). Hence, when people interact with one another by means of speaking or writing, language ideologies available in everyday and scientific discourses at the institutional and societal level may become discursive resources for social categorization. People may draw on different linguistic practices, repertoires, and backgrounds to categorize themselves into in- and out-groups—thus constructing and rationalizing specific intergroup relations (Woolard & Schieffelin, Citation1994). Indeed, language ideologies primarily pertain to intergroup relations; however, they may also be relevant to interpersonal relationships, in light of the process of identity construction, and I am interested in the intersection of these different levels of relationship.

In communication research, intergroup relations are conceived as constructed through the enactment of social identity (i.e. membership in social categories such as ethnicity and social class), and interpersonal relationships through that of personal identity (i.e. idiosyncratic characteristics; Gudykunst, Citation2005). Nevertheless, matters of large-scale intergroup relations may become relevant to interpersonal relationships in local interactional contexts through the enactment of identity. At any point of a social interaction between two or more persons, their membership in social categories might be brought up or acted upon—thus momentarily turning the interpersonal interaction into an intergroup one. Accordingly, in the last two decades, a growing number of discourse studies have attended to both macro-level categorizational and micro-level sequential aspects of social interaction by utilizing a combination of membership categorization analysis and conversation analysis (see Stokoe, Citation2012).

In line with this methodological development, this paper addresses the relevance of language ideologies to interpersonal relationships among students along with their identity construction in locally situated interactions. I argue that it is important to examine language ideologies as discursive building blocks for people to construct their identities to make sense of their interpersonal relationships with others, seeing language as shaping social processes of power and inequality and vice versa (Heller et al., Citation2018).

Language and identity in intercultural communication

Piller (Citation2011) notes that intercultural communication (by means of speaking or writing) is marked by multilingual practices, and points to language choice and language proficiency as crucial aspects of intercultural communication in both practical and ideological senses. Notably, multilingual practices are most likely interpreted as the concurrent use of multiple national or ethnic languages in intercultural interactions, given that intercultural communication is often regarded as involving people with different national or ethnic backgrounds (regardless of whether presupposed, emergent, or negotiated) in intercultural communication studies (e.g. Piller, Citation2011; Zhu, Citation2015).

The notion of language as national or ethnic language—a fixed social construct—has long been taken for granted for the formation and maintenance of nation-states (see Anderson, Citation2006). In recent years, however, multilingualism based on such a monolingual view of national or ethnic membership has been challenged as (re)constructing discursive and material inequalities among people in the globalizing society (e.g. Makoni & Pennycook, Citation2012; Nikula et al., Citation2012). In this vein, sociolinguistic aspects of English have been receiving a great deal of scholarly attention. For example, Holliday (Citation2006) coined the term native-speakerism to problematize inequalities between those who are recognized as so-labeled ‘native’ and ‘non-native’ speakers of English. Alternatively, some inclusive views of English, such as English as a lingua franca (Jenkins, Citation2015) and lingua franca English (Canagarajah, Citation2007), have been introduced to empower anyone who speaks English in their own right. I support the virtue of inclusiveness in lingua franca discourses; however, I also wonder if this shift can accommodate the complexity of the social reality for many of us who still live in the world of nation-states (see Billig, Citation1995). I find the coexisting conflicting views of English in internationalizing higher education intriguing in terms of how students as language speakers navigate their interpersonal relationships.

In the last ten years, some scholars with critical attitudes towards intercultural communication studies (e.g., Dervin & Liddicoat, Citation2013; Piller, Citation2011) have been encouraging examining ‘who makes culture relevant to whom in which context for which purposes’ (Piller, Citation2011, p. 13) in order to address inequalities disguised by ‘cultural differences’. Here, ‘culture’ refers to something related to national or ethnic membership of interactants, acknowledging that what makes communication intercultural is often the involvement of people from different national or ethnic groups (as explained above). Zhu (Citation2015) claims that it is important to negotiate frames of reference and national or ethnic identities for the engagement in intercultural and lingua franca communication. Furthermore, Liddicoat (Citation2016) identifies inequalities between the so-labeled ‘native’ and ‘non-native’ speakers as being co-constructed in interpersonal interactions by both those who benefit from native-speakerism and those who do not. To address the complexity of identity in relation to language as practice and ideology, the notion of language as languaging—a fluid and dynamic practice—has been proposed to reconceptualize language, for instance through the concepts of translanguaging (Li, Citation2018) and metrolingualism (Makoni & Pennycook, Citation2012; Otsuji & Pennycook, Citation2010). Metrolingualism is defined as ‘creative linguistic conditions across space and borders of culture, history and politics, as a way to move beyond current terms such as multilingualism and multiculturalism’ (Otsuji & Pennycook, Citation2010, p. 244, emphasis in original).

Supposedly, internationalizing higher education where English is used as the primary (academic) lingua franca may turn out to be one of the common settings of intercultural and lingua franca communication. Therefore, I set out to examine the roles of different language ideologies in identity construction and negotiation in interpersonal interactions among students in international EMI programs.

Methodology

This study takes a social constructionist approach. I understand language as constituting and being constituted in social realities (Burr, Citation2015), and I also consider the interrelationship between language and power (see Heller et al., Citation2018). People are likely to be afforded multiple versions of their identities through social interaction, some of which might be contradictory, and people as language speakers may be consciously or subconsciously engaging in some power-plays. In acknowledging the emergent, relational, and dilemmatic nature of the social world and the dynamics of power and inequality, I analyze focus group discussions with the framework of critical discursive psychology.

Critical discursive psychology

Critical discursive psychology (CDP) is a type of social constructionist discourse analysis in the critical paradigm, but it takes an ethnomethodological approach to talk and text (Wiggins, Citation2017). This unique combination of theory-guided and data-driven analysis allows examining manifestations of large-scale societal issues in locally situated interactions to critically examine different versions of social reality constructed in talk and text, and thus elucidating the intersection between macro- and micro-level discourses (e.g. Edley, Citation2001). CDP uses the key analytical concepts of interpretative repertoires, subject positions, and ideological dilemmas. Interpretative repertoires are common-sense descriptions or explanations about objects, actions, and events, which are comprised of easily recognizable themes, places, and tropes (Potter & Wetherell, Citation1987; Wetherell, Citation1998). Interpretative repertoires connect wider societal discourse to situated discourse, ‘providing a basis for shared social understanding’ (Edley, Citation2001, p. 198). These repertoires serve as discursive building blocks of social reality, each repertoire offering a different version of reality (Potter & Wetherell, Citation1987; Wetherell, Citation1998). Once interpretative repertoires are employed in talk and text, they afford people specific subject positions as their identities in discourse (Edley, Citation2001; Wetherell, Citation1998). Since different repertoires offer different subject positions, ideological dilemmas may be created when there are inconsistencies or contradictions among the different repertoires co-occurring in a particular talk or text (Edley, Citation2001). These dilemmas socially produce ‘more than one possible ideal world’, which requires ‘an assessment of conflicting values’ (Billig et al., Citation1988, p. 163). Billig et al. (Citation1988) claim that these dilemmas cannot be resolved and can only be handled by changing the topic of discussion.

The three analytical concepts of CDP can be reasonably applied to the exploration of language ideologies. As reviewed above, language ideologies are beliefs widely shared in society that describe or explain language structure and use and people as language speakers. These ideologies may create language-related social categories, and thus afford people specific subject positions based on their linguistic practices, repertoires, and backgrounds. Some language ideologies may contradict one another, and in such a case ideological dilemmas are likely to be created for people. In short, language ideologies can be regarded as interpretative repertoires about language and its speakers. CDP therefore helps identify language ideologies (large-scale societal issues) relevant to students’ discursive construction and negotiation of their identities (locally situated interactions). I find the concept of ideological dilemmas particularly useful for this study to explore contradictory versions of the social reality of students that are possibly produced by different co-occurring language ideologies. The findings will offer insights into the ways in which different language ideologies may act as discursive resources for students to navigate their interpersonal relationships with their peers in the context of today’s internationalizing higher education where English serves as the primary (academic) lingua franca.

Focus group discussions

Focus group discussions are a method of qualitative data collection which utilizes a group discussion ‘focused’ around the research topic of interest or a set of relevant issues (Wilkinson, Citation2016, p. 84). They are commonly used as data sources in CDP studies (e.g. Edley, Citation2001) to increase the accessibility to on-topic talk (Edwards & Stokoe, Citation2004). Although some controversy persists regarding the naturalness of interaction in interviews including focus group discussions, I see these types of interaction as forming ‘a specific discursive space’ in and of itself (Nikander, Citation2012, p. 410). As Morgan (Citation2012) summarizes, the focus of analysis has traditionally been on content (‘what is said’) of discussions, rather than process (‘how it is said’). In recent years, the importance of addressing the connection between the substantive content and the interactive process has been increasingly emphasized (Morgan, Citation2012). This paper, which combines focus group discussions with CDP, is in line with this shift, in that CDP attends to both content and process of interaction (as explained above). I am interested in how different kinds of interpersonal relationships among students are collaboratively created through language ideologies as students chat in small groups.

Data set

Two focus group discussions of students from international master’s programs at JYU are explored in this study. JYU is a Finnish multidisciplinary university with 6 faculties and 17 international master’s programs taught in English in different disciplines (including a joint program with other European universities). Both local and international students are eligible to study in those programs. Of particular note, JYU has been active in integrating recent findings in applied linguistics research into its language policies and practices (e.g. language requirements for admission). It is likely that these policies and practices are exposing JYU students to emerging as well as more established language ideologies. I find JYU interesting as a research site to study the meanings of language ideologies in the social reality of students.

The focus group discussions were conducted in Spring 2021. I recruited participants through a mailing list of the international master’s programs, a few lecturers in those programs, Facebook pages of a few JYU student communities, and a newsletter of the student union of JYU. I asked potential participants to come with one or two of their program peers to have a group discussion about interpersonal relationships among students in their programs, in connection with language practices and proficiency. Eventually, two groups of students voluntarily participated in the study (3 participants in Group 1 and 2 participants in Group 2). I did not collect any demographic profile of the participants (e.g. which program they were in, where they were from). The sessions were conducted in English via Zoom for about one hour (52 minutes in Group 1 and 67 minutes in Group 2). All the participants had their cameras on during the sessions. I provided the following topics as prompts to facilitate discussion: (1) people in your program and the languages they speak, (2) the atmosphere in your program group, (3) doing group work with people in your program (in general/with some particular experiences), (4) interacting with your program peers on campus outside the classroom (in general/with some particular experiences), (5) language proficiency and academic success in your program, and (6) language and friendship with your program peers. In both sessions, I introduced the topics one by one in the chat box over the course of the discussion. After covering all the topics, the participants were given an opportunity to elaborate on some of the topics and also start a new talk according to their interest.

My role in both sessions was to take care of administrative matters as the meeting host, not to moderate the discussion. I had my camera off during the discussion, and I did not ask any follow-up questions to steer the discussion, or offer further explanation on each topic or term. With the participants’ permission, I video-recorded the Zoom sessions using the program’s own recording function, and later transcribed the recordings using Gail Jefferson’s transcript symbols (Citation2004; see Appendix) with some modifications. The transcript of Group 1 is 43 pages long, and that of Group 2 is 45 pages long.

Data analysis

In this study, I take language ideologies as interpretative repertoires about language and people as language speakers, students’ identities as subject positions, and contradictory co-occurring language ideologies as ideological dilemmas. First, I went over the recordings to search for different ways of talking about language and students (e.g. ideas about who speaks what language among students in the participants’ programs, roles of different languages for the students in different interactional situations on campus, their language practices and proficiency expected from one another for everyday and academic purposes). I then examined patterns across these different descriptions to identify language ideologies, taking an ethnomethodological, inductive approach although I was already familiar with some common language ideologies in both everyday and scientific discourses about internationalization of higher education. At the same time, I addressed the construction of the students in the participants’ programs as language speakers. In order to identify these specific students’ identities, I paid attention to the participants’ use of pronouns in different descriptions about the students. By doing so, I shed light on some possible intersections between the students’ situated identity construction in my data and language ideologies pervasive in internationalization of higher education. Lastly, I examined inconsistencies or contradictions among different language ideologies co-occurring in the participants’ talk to search for ideological dilemmas and possibly accompanying identity negotiation of the participants. Throughout the analysis, I attended to interpersonal relationships (including power relations) among the students in the participants’ programs, in acknowledging identity as relational (Bucholtz & Hall, Citation2005).

Findings

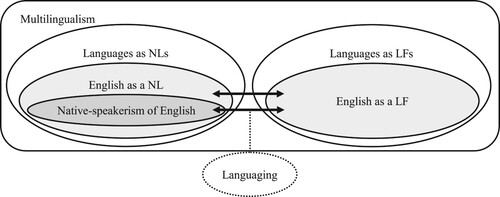

My analysis identifies some common language ideologies based on the established notion of language as national or ethnic language in the participants’ identity construction across the two student focus group discussions (see ). First of all, national language ideologies mediate between languages as first languages and membership in specific national or ethnic communities to construct students as members of specific national or ethnic communities. In contrast, lingua franca ideologies legitimize the use of languages as lingua francas to present students as speakers of specific languages as lingua francas. Accordingly, multilingualism acknowledges the coexistence of different languages as first languages or lingua francas in students’ linguistic repertoires to portray students as multilinguals. Lastly, native-speakerism of English gives the authority on English to students who are recognized as speaking English as the first language over those who are not, classifying students as either so-called ‘native’ or ‘non-native’ speakers of English. Despite the prevalence of these ideologies, the emerging notion of language as languaging is also present in the discussions. The notion of languaging with a focus on purposes of language use distinguishes academic from everyday language in the use of linguistic repertoires to construct students as students.

Figure 1. Language ideologies in the student focus group discussions.

Note. solid figures–language ideologies based on the notion of language as national or ethnic language, dotted figure–the notion of language as languaging, double arrows–ideological dilemmas, NL–national or ethnic language, LF–lingua franca.

In both group discussions, ideological dilemmas occur to apparently complicate the identity construction of the participants who regard English as their first language when the notion of English as a lingua franca is paired with the notion of English as a national or ethnic language or native-speakerism of English (see ). However, multilingualism or the notion of languaging is identified as enabling the participants to reconstruct their identities, and thus the dilemmas are seemingly managed in the participants’ identity negotiation. In what follows, I will explain how my analysis identifies these ideologies in the two focus group discussions with respect to the participants’ identity construction of themselves and their peers, paying attention to the management of ideological dilemmas alongside the participants’ identity negotiation.

Multilingualism for inclusion with a dilemma of being speakers of English as the first language

National language ideologies, lingua franca ideologies, and multilingualism appear to be enabling the participants in both group discussions to describe the student linguistic demographics of their programs. In Group 1, for example, these ideologies can be identified during the discussion on the first topic ‘people in your program and the languages they speak’ (Extract 1):

Extract 1–Group 1 (Topic 1: people in your program and the languages they speak)

S2 succinctly describes the participants’ program as ‘a quite international program’ (Line 1 in Extract 1), which is contrasted with ‘Finnish’ (i.e. locals) by S3 (Line 12 in Extract 1). S3 lists a few more nationalities or ethnicities—‘one from Nepal and Pakistan’ (Line 27 in Extract 1). Language is defined as national or ethnic language when the subject of talk changes from nationality or ethnicity to language in S1’s comment on the language of the peers from Nepal and Pakistan—‘they actually speak the same language’ (Line 28 in Extract 1). The notion of lingua franca appears soon after S1 refers to ‘a lot of people who speak or understand German’ (Lines 36–37 in Extract 1). S3’s subsequent phrases—‘those who studied’ and ‘learn in high school’ (Lines 38–41 in Extract 1)—clarify those students as being recognized as speakers of German as a lingua franca, rather than their first language to claim membership in German-speaking national or ethnic communities. To conclude the topic, S1 portrays the students as a group of multilinguals who speak at least one language as a lingua franca in addition to their first language(s)—‘everybody somehow speaks or at least has learnt one or more foreign languages in their life’ (Lines 70–71 in Extract 1); ‘we’re people who speak quite many languages’ (Lines 75–76 in Extract 1). Given the initial description of the program as ‘a quite international program’, multilingualism complements internationality in the talk. Multilingualism can therefore be interpreted as a discursive resource for inclusive interpersonal relationships in the international groups of students from different national or ethnic communities with different linguistic repertoires.

Multilingualism in both group discussions apparently pivots around English, in that it is pronounced as the lingua franca among the students (in fact, the discussion was conducted in English). This centrality of English seems to result in creating a dilemma between the notions of English as a lingua franca and English as a national or ethnic language when English is claimed to be someone’s first language. In Group 2, the ideological dilemma and its management can be spotted in the discussion on the first topic ‘people in your program and the languages they speak’ (Extract 2):

Extract 2–Group 2 (Topic 1: people in your program and the languages they speak)

S4 describes the students in the participants’ program as ‘speak[ing] quite many [languages]’ (Line 1 in Extract 2) and portrays them as ‘a quite diverse group’ (Line 1 in Extract 2). Considering that language is already defined as national or ethnic language at the beginning of the discussion, the adjective ‘diverse’ here can mean international. Subsequently, S5 claims to be ‘the only person who speaks English as the first language’ (Lines 5–6 in Extract 2). The prefatory phrases ‘I would say’ and ‘I mean’ (Line 4 in Extract 2) imply her hesitation to make such a claim. She then quickly repronounces English as ‘the language that everybody shares and that [the students] study in’ (Lines 8–9 in Extract 2). The conjunction ‘but’ (Line 6 in Extract 2) between the two views of English indicates the dilemma between the notions of English as a national or ethnic language and English as a lingua franca. Later on, S5 again presents herself as ‘the one L1 speaker in [the participants’] group of English’ (Lines 48–49 in Extract 2), and further describes her position as beneficial—‘I just get to benefit from that’ (Line 49 in Extract 2). Although she does not specify what benefit she gets and how she gets it, her remark emphasizes the possible risk of jeopardizing the inclusion of her as part of the group of students as speakers of English as the lingua franca by the differentiation of her as a member of an English-speaking national or ethnic community from her peers. S4 first acknowledges this differentiation by reusing her word ‘the one’ in his phrase ‘the chosen one’ (Line 51 in Extract 2). But then, he draws attention to ‘German’ in her linguistic repertoire (Line 53 in Extract 2), which she accepts (Line 54 in Extract 2). At this moment, S5 is reconstructed as a multilingual who speaks English as the first language and German as a lingua franca to be recognized as part of the international group of students. The ideological dilemma is seemingly managed along with this identity negotiation by shifting attention from English to German. Hence, multilingualism with a focus on languages other than English can be seen as discursively enhancing inclusive interpersonal relationships in the international groups of students who communicate in English as the lingua franca.

Yet, whether those who regard English as their first language can be acknowledged as multilinguals or not seems to depend on how proficient they are expected to be in (an) other language(s). In Group 1, being a multilingual is defined narrowly in the discussion on the last topic ‘language and friendship with your program peers’ (Extract 3), and broadly in the last phase of the discussion session when the participants talk freely about the importance of learning local languages to understand local people while being abroad (Extract 4):

Extract 3–Group 1 (Topic 6: language and friendship with your program peers)

Extract 4–Group 1 (free discussion)

S2 expresses admiration for S1’s linguistic competence—‘you are so fluent in English and Finnish and German’ (Lines 4–6 in Extract 3). S2 then assesses her Finnish vocabulary as ‘not good enough’ (Line 18 in Extract 3). In this sequence of talk, she defines being a multilingual as being proficient in multiple languages for everyday communication, like S1. S2 thus fails to construct herself as a multilingual, highlighting her low proficiency in Finnish. After a while, in the last phase of the discussion session, S3 points to many languages in S2’s linguistic repertoire—‘is that why you try to learn different many languages’ (Lines 1–5 in Extract 4). S2 ambiguously approves S3’s comment—‘I mean I enjoy learning and I love culture’ (Lines 7–10 in Extract 4). In this segment of talk, being a multilingual is redefined as speaking multiple languages regardless of proficiency. Here, S2 is reconstructed as a multilingual. This identity negotiation suggests that, by removing the threshold for language proficiency, multilingualism can be made more inclusive in the international groups of students when those who regard English as their first language assess their proficiency in languages other than English relatively low.

Languaging for inclusion with a dilemma of being so-called ‘native’ speakers of English

In both group discussions, a dilemma seems to be created between the notion of English as a lingua franca and native-speakerism of English when English is claimed to be someone’s first language as to proficiency for academic purposes. For instance, the ideological dilemma can be found in the discussion of Group 1 on the fifth topic ‘language proficiency and academic success in your program’ (Extract 5):

Extract 5–Group 1 (Topic 5: language proficiency and academic success in your program)

S1 portrays the students in the participants’ program as equally proficient speakers of English in her assessment on their English proficiency—‘we all have a quite good level of English … otherwise we wouldn’t have been accepted to this program anyway or wouldn’t have applied’ (Lines 1–7 in Extract 5). After a long pause, however, S2 pronounces English as ‘[her] native language’ (Lines 14–15 in Extract 5), and then assesses her peers’ academic performance in English—‘it really impresses me that people can do a whole master’s program in English’ (Lines 15–17 in Extract 7). In this sequence of talk, a link is established between S2’s authority on English over her peers and her membership in an English-speaking national or ethnic community. The contrasting descriptions by S1 and S2 of the students’ English proficiency for academic purposes can be interpreted as displaying the dilemma between the notion of English as a lingua franca and native-speakerism of English. This dilemma implies that the inclusion of all the students as speakers of English as the lingua franca is potentially jeopardized by a hierarchical relationship between S2 as a so-called ‘native’ speaker of English and her peers as ‘non-native’ speakers. Nevertheless, this possible risk is not explicitly brought up in the participants’ talk.

Meanwhile, such a risk is articulated by S5 in Group 2 during the discussion on the third topic ‘doing group work with people in your program’ (Extract 6):

Extract 6–Group 2 (Topic 3: doing group work with people in your program)

S5 expresses her worry about being a person who speaks English as ‘[her] first language’ (Line 2 in Extract 6) in a hypothetical situation in which she corrects her peers’ English without telling them—‘if I see that something is incorrect grammar-wise or whatever else I would just go behind people and fix it’ (Lines 6–9 in Extract 6). This sequence of talk indicates that she gives the authority on English to herself as a member of an English-speaking national or ethnic community. She continues to say that being ‘the only person that has English as the first language … has a different tone’ (Lines 11–15 in Extract 6). Despite S4’s disagreement with her—‘no I don’t think like that’ (Line 17 in Extract 6), S5 problematizes her supposed role as a language checker for her peers, pointing to the possibility that she might ‘insult someone accidentally’ (Line 20 in Extract 6) by secretly correcting their English. Many fillers (e.g. ‘it’s like’, ‘I mean’, ‘maybe you wouldn’t but’, ‘you never want to like’, ‘I don’t know’; Lines 15–20 in Extract 6) imply her hesitation to articulate such a worry. In this segment of talk, native-speakerism of English seems to be enabling S5 to hypothetically construct and also problematize herself as a so-called ‘native’ speaker of English in contrast to her peers as ‘non-native’ speakers. The two group discussions taken together indicate that native-speakerism of English can be seen as a necessary but controversial resource for the identity construction of those who regard English as their first language in the international groups of students who study together in English as the lingua franca.

As seen above, the participants in both group discussions center on English when the topics are related to language use for academic purposes, and correspondingly multilingualism cannot be identified as highly relevant to their identity construction. Instead, the notion of languaging can be identified alongside native-speakerism of English, for example, during the discussion of Group 2 on the fifth topic ‘language proficiency and academic success in your program’ (Extract 7):

Extract 7–Group 2 (Topic 5: language proficiency and academic success in your program)

S5 characterizes ‘academic English’ with ‘specific terms and certain kinds of knowledge’ that are ‘things [she] also didn’t know’ (Lines 3–8 in Extract 7). The specific purposes and characteristics of academic language are emphasized in such a description of academic English. As shown in the phrase ‘I also’ (Line 8 in Extract 7), she singles herself out as an exception among the students in the participants’ program, constructing herself as a person who would be expected to know those characteristics of academic English. S5 seems to be differentiating herself as a so-called ‘native’ speaker of English from her peers as ‘non-native’ speakers, given her earlier construction of herself and her peers as such. At the same time, she is including herself as part of the group of students who are learning academic English. In a sense, the very short phrase ‘I also’ captures a moment when S5 is reconstructing herself and her peers equally as students by shifting the focus from national or ethnic categories of language to purposes of language use. This identity negotiation can be interpreted as putting native-speakerism of English and the notion of English as a lingua franca aside to result in the management of the dilemma between these two ideologies, both of which are bound to English, a named language. It also suggests the notion of languaging as a discursive resource for inclusive interpersonal relationships in the international groups of students who use English as the academic lingua franca. That said, a clear-cut distinction between academic and everyday languages seems unlikely, as S5 expresses difficulty in distinguishing ‘general [language] proficiency’ from ‘academic style writing’ (Lines 46–50 in Extract 7).

Discussion

My analysis identifies national language ideologies, lingua franca ideologies, multilingualism, native-speakerism of English, and the notion of languaging as relevant to students’ discursive construction of their identities in the two groups of students from international master’s programs at JYU. In particular, the notion of English as a lingua franca prevails throughout the discussions, creating dilemmas when paired with the notion of English as a national or ethnic language or native-speakerism of English. These ideological dilemmas apparently put the participants who regard English as their first language in a difficult position when they construct their identities. Inclusive interpersonal relationships between them and their peers (all as speakers of English as the lingua franca) are potentially jeopardized by divisive or hierarchical interpersonal relationships between them and their peers (as members and non-members of English-speaking national or ethnic communities or as so-called ‘native’ and ‘non-native’ speakers of English). There are nevertheless moments where those specific participants are reconstructed as multilinguals just like their peers, or all of them as students, by shifting attention from English to other languages and from national or ethnic categories of language to purposes of language use. Seemingly, this identity negotiation as a result of emphasizing multilingualism or the notion of languaging enables the dilemmas to be managed, leading to the discursive maintenance of inclusive interpersonal relationships among the students in the participants’ programs.

In the early phase of the discussions, the participants and their peers are constructed as multilinguals who speak at least one language as a lingua franca as well as their first language(s). This suggests that the established notion of language as national or ethnic language (Anderson, Citation2006) is likely to serve students in international EMI programs as the default framework of identity in terms of language. Although the monolingual view of national or ethnic membership has been challenged as disregarding the fluid and dynamic nature of linguistic practices and identity construction (e.g. Li, Citation2018; Makoni & Pennycook, Citation2012; Otsuji & Pennycook, Citation2010), multilingualism based on such a view of language and people may be essential for students to highlight their internationality when they are all recognized as English speakers regardless of membership in different national or ethnic communities. On the one hand, this traditional, conventional understanding of multilingualism might enable students to see themselves as an international group of multilinguals. On the other hand, it might (re)construct in- and out-groups and also hierarchies among languages and speakers of those languages in the student community. Nikula et al. (Citation2012) have pointed out this risk in their explanation of ‘monolingual multilingualism’: ‘the representation of languages as hierarchical entities of our, national, foreign and so on, which implies that languages are learned and used separately, each in their own sphere’ (p. 61, emphasis in original).

The central position of English as the primary (academic) lingua franca most likely contributes to the construction of not only inclusive but also divisive and hierarchical interpersonal relationships among students. Over the last few decades, stakeholders of internationalization of higher education, including students, have been encouraged to see English as a lingua franca for its theoretical inclusiveness (e.g. Björkman, Citation2011; Jenkins, Citation2014). In practice, however, the notion of English as a lingua franca may not always support the inclusion of all students as English speakers, as illustrated by the ideological dilemmas about English in this study. Students who regard English as their first language may differentiate themselves and/or be differentiated from their peers based on their membership in English-speaking national or ethnic communities, and furthermore, this differentiation might create a hierarchy between them and their peers as so-called ‘native’ and ‘non-native’ speakers of English. Notably, despite the fact that native-speakerism of English has been receiving criticism for its artificial and prejudicial nature (e.g, Holliday, Citation2006), none of the participants in both group discussions seems to be fully accepting the hierarchy nor directly challenging it. Rather, the hierarchical interpersonal relationships are co-constructed in the discussions (see Liddicoat, Citation2016). This co-construction implies that the participants who regard some language(s) other than English as their first language(s) are enacting respect for their peers’ claim of membership in English-speaking national or ethnic communities, which is afforded by native-speakerism (see Doerr, Citation2009).

Meanwhile, inclusive interpersonal relationships among the students in the participants’ programs are maintained in both discussions, seemingly by emphasizing multilingualism or the emerging notion of language as languaging, as seen in the participants’ identity negotiation. Interestingly, this is in line with two major suggestions made in recent literature. From a perspective of linguistic diversity (see Piller, Citation2016), Jenkins and Leung (Citation2019) stress the importance of multilingual resources of students who regard English as their first language to enhance communication and equality among students in international universities where English is used as the primary (academic) lingua franca. Similarly, Jenkins emphasizes multilinguality in her recent definition of English as a lingua franca: ‘multilingual communication in which English is available as a contact language of choice, but is not necessarily chosen’ (Citation2015, p. 73). Yet, as the case of Group 2 indicates, to what extent multilingualism can be inclusive is subject to whether a threshold for language proficiency is set or not. As another suggestion, recent studies on university language policies call attention to the specific purposes and characteristics of academic language (e.g. Kuteeva, Citation2014; Leung et al., Citation2016) and discipline-specific linguistic practices (e.g. Airey et al., Citation2017), which are not necessarily tied to national or ethnic categories of language. However, such categories may often be more salient than the distinction between academic and everyday languages, given the difficulty of clearly distinguishing academic from everyday language, as pointed out by Group 1.

Overall, I find it valuable to learn that multilingualism (with a focus on languages other than English) and the notion of languaging (with a focus on purposes of language use) may play important discursive roles in sustaining inclusive interpersonal relationships among students in internationalizing and Englishizing higher education. The flexible use of emerging and established language ideologies may allow students to ‘accommodate both fixity and fluidity’ of their identities as language speakers (Otsuji & Pennycook, Citation2010, p. 252). The findings suggest that turning students’ attention towards the multilinguality of every student and the specific purposes and characteristics of academic language might encourage students to see themselves all as multilingual students for enhanced inclusion—rather than solidifying themselves as English speakers for division and hierarchy along with inclusion. In doing so, the ideological dilemmas about English might be managed although they cannot be resolved (see Billig et al., Citation1988). These implications align with Amadasi and Holliday’s (Citation2017) argument on intercultural narratives—students need to be encouraged to nurture ‘thread narratives that resonate across boundaries to reveal shared cultural creativity’ rather than ‘block narratives that restrict, separate, and maintain essentialist boundaries’ (p. 258) for creative engagement with others in new environments. Lecturers and universities may consider these points in their classrooms and institutional language policies and practices to provide inclusive learning environments for diverse students.

To conclude, I would like to note that the participants in this study might have been highly motivated to demonstrate their fellowship or friendship during the group discussions, taking into account that they were recruited as groups of program peers who agreed on sharing their talk about interpersonal relationships among students in their programs. Indeed, it requires further research to examine if the kinds of relationships students wish to create with their peers might determine the ways in which different language ideologies are made relevant to students’ identity construction and negotiation, and/or vice versa.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the students who generously shared their time and experiences with me. This study would have not been possible without their contribution. I am also grateful to my supervisors, Malgorzata Lahti, Marko Siitonen, and Laura McCambridge, for their thoughtful guidance and support over the course of writing this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mai Shirahata

Mai Shirahata is Doctoral Researcher in Intercultural Communication at the Department of Language and Communication Studies, University of Jyväskylä, Finland. She is interested in ethnomethodological approaches to intercultural communication. Her doctoral research project explores language ideologies in internationalizing higher education concerning intergroup relations and interpersonal relationships among students.

References

- Airey, J., Lauridsen, K. M., Räsänen, A., Salö, L., & Schwach, V. (2017). The expansion of English-medium instruction in the Nordic countries: Can top-down university language policies encourage bottom-up disciplinary literacy goals? Higher Education, 73(4), 561–576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9950-2

- Amadasi, S., & Holliday, A. (2017). Block and thread intercultural narratives and positioning: Conversations with newly arrived postgraduate students. Language and intercultural communication, 17(3), 254–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2016.1276583

- Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. Verso.

- Billig, M. (1995). Banal nationalism. Sage Publications.

- Billig, M., Condor, S., Edwards, D., Gane, M., Middleton, D., & Radley, A. (1988). Ideological dilemmas: A social psychology of everyday thinking. Sage Publications.

- Björkman, B. (2011). English as a lingua franca in higher education: Implications for EAP. Ibérica, 22, 79–100.

- Bucholtz, M., & Hall, K. (2005). Identity and interaction: A sociocultural linguistic approach. Discourse Studies, 7(4–5), 585–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445605054407

- Burr, V. (2015). Social constructionism (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Canagarajah, S. (2007). Lingua franca English, multilingual communities, and language acquisition. The Modern Language Journal, 91, 923–939. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2007.00678.x

- Dervin, F., & Liddicoat, A. J. (2013). Introduction: Linguistics and intercultural education. In F. Dervin, & A. J. Liddicoat (Eds.), Linguistics for intercultural education (pp. 1–25). John Benjamins.

- Doerr, N. M. (2009). The native speaker concept: Ethnographic investigations of native speaker effects. Mouton de Gruyter.

- Edley, N. (2001). Analysing masculinity: Interpretative repertoires, ideological dilemmas and subject positions. In M. Wetherell, S. Taylor, & S. J. Yates (Eds.), Discourse as data: A guide for analysis (pp. 189–228). Sage Publications.

- Edwards, D., & Stokoe, E. (2004). Discursive psychology, focus group interviews and participants’ categories. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 22(4), 499–507. https://doi.org/10.1348/0261510042378209

- Gudykunst, W. B. (2005). An anxiety/uncertainty management (AUM) theory of effective communication: Making the mesh of the net finer. In W. B. Gudykunst (Ed.), Theorizing about intercultural communication (pp. 281–322). Sage Publications.

- Heller, M., Pietikäinen, S., & Pujolar, J. (2018). Critical sociolinguistic research methods: Studying language issues that matter. Routledge.

- Henriksen, B., Holmen, A., & Kling, J. (2019). English medium instruction in multilingual and multicultural universities: Academics’ voices from the Northern European context. Routledge.

- Holliday, A. (2006). Native-speakerism. ELT Journal, 60(4), 385–387. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccl030

- Irvine, J. T. (1989). When talk isn’t cheap: Language and political economy. American Ethnologist, 16(2), 248–267. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.1989.16.2.02a00040

- Jefferson, G. (2004). Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In G. H. Lerner (Ed.), Conversation analysis: Studies from the first generation (pp. 13–31). John Benjamins.

- Jenkins, J. (2014). English as a lingua franca in the international university: The politics of academic English language policy. Routledge.

- Jenkins, J. (2015). Repositioning English and multilingualism in English as a Lingua Franca. Englishes in Practice, 2(3), 49–85. https://doi.org/10.1515/eip-2015-0003

- Jenkins, J., & Leung, C. (2019). From mythical ‘standard’ to standard reality: The need for alternatives to standardized English language tests. Language Teaching, 52(1), 86–110. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444818000307

- Kroskrity, P. V. (2010). Language ideologies – Evolving perspectives. In J. Jaspers, J. O. Östman, & J. Verschueren (Eds.), Society and language use (pp. 192–211). John Benjamins.

- Kuteeva, M. (2014). The parallel language use of Swedish and English: The question of ‘nativeness’ in university policies and practices. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 35(4), 332–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2013.874432

- Leung, C., Lewkowicz, J., & Jenkins, J. (2016). English for academic purposes: A need for remodelling. Englishes in Practice, 3(3), 55–73. https://doi.org/10.1515/eip-2016-0003

- Li, W. (2018). Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Applied Linguistics, 39(1), 9–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amx039

- Liddicoat, A. J. (2016). Language planning in universities: Teaching, research and administration. Current Issues in Language Planning, 17(3–4), 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2016.1216351

- Makoni, S., & Pennycook, A. (2012). Disinventing multilingualism: From monological multilingualism to multilingual francas. In M. Martin-Jones, A. Blackledge, & A. Creese (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of multilingualism (pp. 439–453). Routledge.

- McCambridge, L., & Saarinen, T. (2015). “I know that the natives must suffer every now and then”: Native/non-native indexing language ideologies in Finnish higher education. In S. Dimova, A. K. Hultgren, & C. Jensen (Eds.), English-medium instruction in European higher education (pp. 291–316). De Gruyter.

- Morgan, D. L. (2012). Focus groups and social interaction. In J. F. Gubrium, J. A. Holstein, A. B. Marvasti, & K. D. McKinney (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of interview research: The complexity of the craft (pp. 161–176). Sage Publications.

- Nikander, P. (2012). Interviews as discourse data. In J. F. Gubrium, J. A. Holstein, A. B. Marvasti, & K. D. McKinney (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of interview research: The complexity of the craft (pp. 397–414). Sage Publications.

- Nikula, T., Saarinen, T., Pöyhönen, S., & Kangasvieri, T. (2012). Linguistic diversity as a problem and a resource – Multilingualism in European and Finnish policy documents. In J. Blommaert, S. Leppänen, P. Pahta, & T. Räisänen (Eds.), Dangerous multilingualism: Northern perspectives on order, purity and normality (pp. 41–66). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Otsuji, E., & Pennycook, A. (2010). Metrolingualism: fixity, fluidity and language in flux. International Journal of Multilingualism, 7(3), 240–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790710903414331

- Piller, I. (2011). Intercultural communication: A critical introduction. Edinburgh University Press.

- Piller, I. (2016). Linguistic diversity and social justice: An introduction to applied sociolinguistics. Oxford University Press.

- Potter, J., & Wetherell, M. (1987). Discourse and social psychology: Beyond attitudes and behaviour. Sage Publications.

- Saarinen, T., & Nikula, T. (2013). Implicit policy, invisible language: Policies and practices of international degree programmes in Finnish higher education. In A. Doiz, D. Lasagabaster, & J. Sierra (Eds.), English-medium instruction at universities: Global challenges (pp. 131–150). Multilingual Matters.

- Stokoe, E. (2012). Moving forward with membership categorization analysis: Methods for systematic analysis. Discourse Studies, 14(3), 277–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445612441534

- Wetherell, M. (1998). Positioning and interpretative repertoires: Conversation analysis and post-structuralism in dialogue. Discourse & Society, 9(3), 387–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926598009003005

- Wiggins, S. (2017). Discursive psychology: Theory, method and applications. Sage Publications.

- Wilkinson, S. (2016). Analyzing focus group data. In D. Silverman (Ed.), Qualitative research (pp. 83–100). Sage Publications.

- Woolard, K. A., & Schieffelin, B. B. (1994). Language ideology. Annual Review of Anthropology, 23(1), 55–82. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.23.100194.000415

- Zhu, H. (2015). Negotiation as the way of engagement in intercultural and lingua franca communication: Frames of reference and interculturality. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 4(1), 63–90. https://doi.org/10.1515/jelf-2015-0008

Appendix

Transcription symbols