Abstract

The fight against negative neighbourhood effects has been led by urban regeneration policies aimed at mixing by ethnicity, income, tenure as well as demolition and poverty deconcentration – all of which sought to create mixed communities with improved reputations. This paper is based on the methodology applied in my PhD research and outlines how Participatory Photo Mapping (PPM) can evaluate impact and explore internal neighbourhood reputations providing both temporality and depth to the perception of urban spaces affected by change. PPM has involved residents of two European disadvantaged neighbourhoods (New Deal for Communities area, Bristol; Ponte Lambro, Milan) in the active and collaborative construction of their own narratives on the area and its developments and interventions. While also referring to the empirical findings, this paper focuses on the design and delivery of PPM and covers the challenges and the opportunities of the research method, conducted in times of Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns and social distancing. Despite the remote but innovative setting (Google My Maps) and data collection (online focus groups and 1–1 interviews), PPM confirms being an empowering tool to ‘re-create’ place images from within and give voice to urban areas where territorial stigma tends to prevail.

INTRODUCTION: AN OVERVIEW OF THE STUDY

Research on urban neighbourhoods and, notably, on state-led regeneration has primarily focused either on territorial stigmatisation and neighbourhood reputations, including social housing estates (Kearns, Kearns, and Lawson Citation2013; Permentier, van Ham, and Bolt Citation2008; Slater Citation2021; Wacquant Citation2007), or on the effects of social mix or tenure mix on the residents’ social fabric and mobility (Arthurson, Levin, and Ziersch Citation2015; Barwick Citation2018). From a methodological point of view, quantitative research is emphasised in both fields of study, and when qualitative methods are employed, they generally focus on specific moments in time or discrete events (during or immediately after a specific event), rarely considering the long-term effects of local phenomena such as neighbourhood change. Social mix and territorial stigma literatures also appear to rarely meet either theoretically or methodologically, although existing studies have demonstrated the close relationship between neighbourhood change and reputations as well as their implications on further inequalities and discrimination (Arthurson Citation2013; Permentier, van Ham, and Bolt Citation2007; Slater Citation2021).

This paper focuses on the qualitative and creative research method used within my international comparative PhD research project which goes further in assessing the impact of social mixing policies over the longer term, through the analysis of neighbourhoods’ reputations. The PhD research has explored the long-term impact of social mix in Ponte Lambro, Milan, and the New Deal for Communities areaFootnote1, Bristol, on both internal and external neighbourhood reputations, by looking respectively at perceptions from local communities and local newspaper articlesFootnote2 from a Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) approach. The two disadvantaged and historically stigmatised areas have been targeted by state-led urban regeneration policies, Contratto di Quartiere II (CdQ) and the New Deal for Communities (NDC) in the early 2000s for about 10 years. Both policies aimed at ‘desegregation’ of ‘problem areas’ through social and tenure mixing as well as community involvement through private and public partnerships (Calvaresi and Cossa Citation2011; MacLeavy Citation2009). Although local specificities in the design and implementation ought to be considered, Ponte Lambro and the NDC area were selected because of their similar experiences: the renovation of social housing estates as well as of public facilities, including schools, parks, and community centres; the tenure and social mixing practices within specific blocks (in Ponte Lambro) and through the integration of private housing compounds (in the NDC area); the common overarching aspirational aim of improving the neighbourhoods’ reputation in the long run (Calvaresi and Cossa Citation2011, 17; Community at Heart Citation2005, 8). Their territorial stigma, making them continuous targets of renewal interventions, builds upon their concentrated socio-economic deprivation, social housing, and immigration/minority ethnic demographics (Comune di Milano Citation2011; Bristol City Council Citation2018). Building on the conceptualisation of neighbourhood reputation identified by Permentier, van Ham, and Bolt (Citation2008), the project provides an alternative methodological approach for the investigation and analysis of reputations, based on qualitative methods of CDA and Participatory Photo Mapping (PPM) alongside semi-structured focus groups and interviews. This paper’s focus is to present PPM as a valid collaborative, remote, and creative research method to investigate place images, and in particular internal neighbourhood reputations in the two case studies.

In the next section, I set out the theoretical and methodological approach behind the deploy of PPM. Then, I present the research method considering data collection and analysis, and focus the research findings on a specific aspect of the internal neighbourhood reputation, that is the visual place image provided by the PPM. The last sections outline the contributions to existing literature, highlighting advantages and limitations encountered while conducting remote PPM during the Covid-19 pandemic.

CONTEXT OF APPLICATION AND APPROACH

Although the literature on state-led social mixing strategies has analysed their long-term effects on the targeted neighbourhoods, especially in the US mixed communities’ context (Chetty, Hendren, and Katz Citation2016; DeLuca and Rosenblatt Citation2010; Mendenhall, DeLuca, and Duncan Citation2006), insufficient attention has been paid to the European context, in terms of comparative and longitudinal approaches, as well as participatory methods (Agustoni, Alietti, and Cucca Citation2015; Bacqué et al. Citation2011; Bolt, Van Kempen, and Van Weesep Citation2009; Moreira de Souza Citation2019). By contrast, the literature on neighbourhoods’ reputations (Permentier, van Ham, and Bolt Citation2008) and territorial stigmatisation (Slater Citation2021; Wacquant Citation2007) has rarely considered the impact of change and social mixing interventions in shaping and re-shaping perceptions both inside and outside the affected urban area. In order to provide an integrated perspective and additional insights into policy aims and the impacts of policy implementation over time, the PPM employed in this project considers the performative feature of discourse as powerful tool in the construction of ‘truths’ and urban realities (Foucault Citation1981), thus taking an epistemological approach based on the discourse analysis of place images and territorial stigma of urban areas affected by change.

Standing out from the mostly quantitative literature on neighbourhood reputations, I provide a more integrated overview of the constructions of power and place images within the case studies, by adopting qualitative research methods to assess the impact of CdQ and NDC policies in Ponte Lambro and the NDC area. An only quantitative approach to neighbourhood reputations, as it has often been the case in the literature on territorial stigma and place image (Jones and Dantzler Citation2020), not only prevents to understand the roots of such perceptions, but tends also to keep significant stories and experiences of the place out of the analysis, ignoring the ‘dynamics of reputations’ and the ‘power actors’ responsible of their construction (Permentier, van Ham, and Bolt Citation2008, 851). Thanks to the deployment of a qualitative methodology, this research sheds light on the importance of investigating external and internal neighbourhood reputations together, given their mutual influence of active and passive actors playing at the local level (Arthurson Citation2013). Instead of looking at the discourse framed either by residents or by the urban regeneration policy, as urban and housing studies have largely explored (Hastings Citation2000; Jacobs Citation2006; Richardson Citation1996; Watt Citation2008), this project looks at the narratives produced by both the local press and the local community. I hence conceptualise the discourse produced by the local press as external reputation; while internal reputation results, in this specific case, from the interplay between three levels of perceptions (a. the changed neighbourhood, which includes visual place image, as well as positive, negative, and neutral perceptions; b. the social mixing policy; c. the external reputation or stigma). To investigate the long-term outcomes of the policies through the dimension of reputation, the research has employed a comparative approach across time and space, which not only provides in-depth temporality to the discursive approach, but it also allows for the identification of differences and similarities between the place images themselves and the delivery of social mixing practices in two distant but similar urban contexts.

Although residents’ perceptions on urban areas have often been gathered through quantitative or qualitative surveys in the academic and grey literature (Permentier, van Ham, and Bolt Citation2008; Citation2007; Permentier, Bolt, and van Ham Citation2008 Citation2011; Jones and Dantzler Citation2020), qualitative research methods, such as focus groups and 1–1 interviews, and particularly participatory research, have the potential to appreciate the complexity of personal experiences and neighbourhood reputations, and provide fundamental insights into policymaking (Arthurson Citation2013; Bryman Citation2012). To explore the production and the evolution of the internal neighbourhood reputations, I have undertaken fieldwork, both remotely and in person, involving residents of the two areas in the making of PPM. Within the field of urban geography and sociology, photographs have been used as research tools in various forms. From participant-driven photo-elicitation (Barker et al. Citation2022; Jeon and Kim Citation2023; Van Auken, Frisvoll, and Stewart Citation2010), to photo-voice (Carpenter Citation2022; Cheng Citation2021; Liebenberg Citation2019), visual methods involving the direct control of participants over the research tool – photographs of their neighbourhood – facilitate meaningful and in-depth data generation, that can capture lived experience and elicit new perspectives on the local space. These methods have been generally applied to in-person ethnography, and seldom to remote contexts of research (Bakare and James Citation2022). PPM positions itself between participatory mapping (Corbett Citation2009; Töppel and Reichel Citation2021) and photovoice led by participants (McIntyre Citation2003) and has been employed in urban and housing studies involving a face-to-face design. The spatial dimension of the neighbourhood map provides a further layer of analysis, hence an added value and depth to the data collected: as photographs are geographically contextualised, participants are able to share their knowledge, experience, and perception of the place through a fully visual support. Within geography, urban planning and housing studies, as well as social science more broadly, PPM has been used to investigate locals’ perceptions of their neighbourhood on, among others, property vacancy (Teixeira Citation2015), social mobility (Richardson et al., Citation2019), public housing (Teixeira et al. Citation2020). This study, conversely, employs PPM as a remote tool to explore how local communities perceive their neighbourhood over time and in relation to the effects of social mixing policies.

METHODOLOGY

As a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, which broke out in Italy just before I could start my fieldwork in Milan, the face-to-face and ethnographic dimensions that were initially considered in my research design and ethics had to be readapted to the new circumstances of social distancing and travel restrictions.Footnote3 In light of this disruption, PPM needed to be moved to an online setting with the employ of Google My Maps and paired with remote focus groups and 1–1 interviews with residents of Ponte Lambro and the NDC area. Online focus groups on Zoom (with up to three participants each) were initially offered to participants as the primary research method to allow collaborative construction of perceptions, sharing of memories and uses related to the neighbourhood. However, if focus groups could not be facilitated because of participants’ unavailability, 1–1 interviews online or over the phone were suggested as alternative option to take part in the study. When evaluating the ethical implications of conducting social research during a pandemic, priority was given indeed to flexibility and inclusion as criteria to guide the research process and face times of great life and research uncertainty that was affecting marginalised communities especially (Gratton, Fox, and Elder Citation2020; Howlett Citation2020). Participation to all parts of the study, including PPM, became voluntary and open to any change of plans or impediments from participants.

Data Source and Sample

Considering the travel and social distancing restrictions in place during the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic, data collection from the field sites had to take place remotely. As a result, the recruitment and sampling of research participants had also to be carried out predominantly at distance, although contacting and meeting with local community centres and institutions still resulted to be crucial in building trust with residents and spreading the word about the project. To respond to the research question on the internal neighbourhood reputation and how it has evolved with the end of the social mixing policies, the sample included both long-term residents (current and former) living in the areas since late 1990s, and newcomers, who have been living in the neighbourhoods for 5 years or less. Former residents are also considered since they either have lived before and during the implementation of the social mixing policies in the area, or they have moved into the neighbourhood’s surroundings and kept a strong relationship with it, which allowed to express their views also on the most recent developments. Both circumstances provide longitudinality to the data on how both the neighbourhood and their perceptions changed over the years. Calls for participants were distributed via remote and in-person strategies: participants were recruited mainly via Facebook neighbourhood and postcode groups, but also through posters shared in popular meeting places in the areas, as well as through snowball-sampling. Data collection through focus groups and 1–-1 semi-structured interviews as well as participant observation in the field covered about 4 months for each case study. Overall, 40 participants (20 each) took part in the study, forming a relatively diverse sample in terms of demographic characteristics and time of residence in the neighbourhood. In both instances and for both case studies the PPM entailed the following steps:

Photographs of the area could either be taken in the days prior to the interview/focus group or could also be part of the participant’s personal album – notably, if they wished to illustrate local changes. Participants were given liberty to establish subjects and number of photographs they wished to share (hence the difference in the final numbers of photographs on the maps), but these were required to be representative of ‘how they see their neighbourhood’, thus ‘how they would represent its identity’ using a camera. Their contribution was then shared with me by the day of the meeting with a brief description and address of the location where the photo was taken.Footnote4

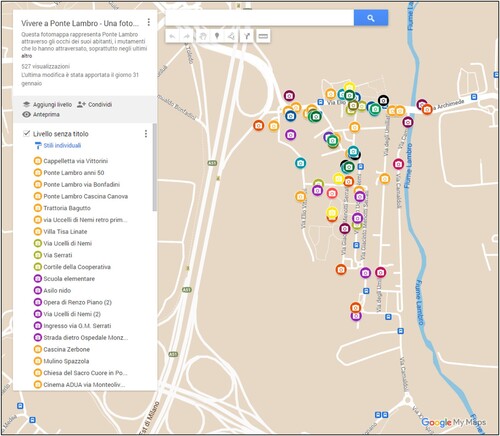

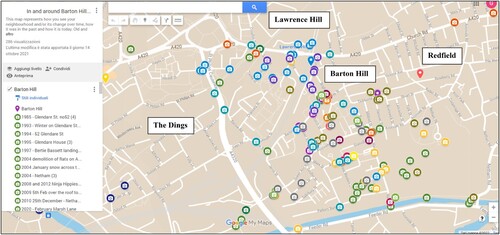

Information about the photographs’ location was used to build the shared and private online map on Google My Maps. To facilitate participants in the use of the map, I was responsible of its creation and editing, including uploading, and locating the photographs, whilst participants were only able to access it and view its content. As illustrated by the figures below ( and ), each tag contains one or more photographs and descriptions (up to 3) which open with a click; tags are divided into colours and each colour was assigned to a participant to ensure anonymity.

Focus groups and interviews were semi-structured to ensure flexibility whilst still guiding the discussion and group interaction, which was organised around three topics: (I) the motivations and stories behind the photographs selected by participants and their comments on the map; (II) the neighbourhood change over time, especially with and after the social mixing policy’s interventions; (III) their experience and perception of the external discourse on the neighbourhood. Perceptions and experiences collected were supported by participant observation in the field sites, where the interaction with local organisations, history groups, and community centres allowed the data to be contextualised and confirmed through triangulation.

As it is often the case with photovoice (McIntyre Citation2003), after each fieldwork I organised a small temporary exhibition, with the support of Barton Hill History Group for Bristol and Uniponte youth club (C.A.G. Ponte Lambro) for Milan, where the results of each PPM were presented to the public and the local community. This represented an opportunity to not only give back to the community that informed my research, but also to bring the discussion further and share knowledge and narratives on the neighbourhood that can differ from the wider discourse and often challenge it as counter-narrative (Garbin and Millington Citation2012).

Within the NDC area, I conducted 14 in-depth semi-structured interviews and 2 online focus groups. The final sample included 10 current long-term residents, 6 newcomers and 4 former long-term residents, for a total of 20 participants. Most participants (ten) came from the neighbourhood of Barton Hill, which was predominantly affected by the interventions, six from Redfield, two from Lawrence Hill, and one from The Dings – an aspect which is also mirrored by the distribution and number of photographs on the map (). 17 participants out of 20 agreed to take part in the PPM of the area, which resulted in the sharing of 175 photographs. In the summer of 2021, as soon as international travel was permitted, I spent three months in the neighbourhood of Ponte Lambro where I conducted in-person participatory observation as well as remote focus groups and interviews with residents. I ran fourteen 1–1 semi-structured interviews and three online focus groups; in both instances and throughout my interaction with participants, I employed my first language, Italian. The Ponte Lambro sample included 12 current long-term residents, seven former residents, and one newcomer. And 14 participants out of 20 contributed to the PPM of the neighbourhood, sharing overall 92 photographs.

Data Analysis

Photographs from the PPM maps and related descriptions and comments were coded through Thematic Coding (Keats Citation2009; Rose Citation2016). Semiotic analysis, which is generally applied to visual data, was not considered as analytical method as photographs served as data supporting and informing the internal neighbourhood reputation from interviews and focus groups; and the interpretation of the photographs was suggested by captions and comments provided directly by participants. Moreover, given the considerable number of photographs (92 from Ponte Lambro and 175 from the NDC area), those photographs featuring something that was not discussed or explained at all during data collection were excluded from the analysis, including when the photograph did not carry any caption and did not elicit any direct or indirect comment from participants. The PPM allowed to build what emerged as the visual place image of the two local contexts and integrated at the same time other dimensions or layers of the internal neighbourhood reputation: the positive, negative, neutral perceptions of the changed neighbourhoods; the perceptions of the urban interventions over the time.

CDA was applied not only on newspaper articles in relation to the external reputation, but also in the analysis of focus groups and interviews data to explore discourses informing the internal neighbourhood reputations (Fairclough Citation1992; Huckin Citation1997; Waitt Citation2010). This research method is applied on the textual analysis as operationalised by the linguist Norman Fairclough (Citation1992; Citation2003), that is by following an inductive approach within a three-dimensional framework that goes from the micro (the text) to the meso (the discursive practice or context of production) and macro (the social practice or the society where it is embedded) levels of analysis (Huckin Citation1997). To provide further depth to the interpretation of the data, CDA was combined with Critical Narrative Analysis (CNA) (Dunn Citation2001; Souto-Manning Citation2014), which allows for the identification within the texts (interview and focus groups transcripts) of internalised or ‘recycled’ language from the external discourse on the area. Indeed, since ‘everyday narratives as a genre offer institutional discourses an effective way to assert themselves as power discourses’ (Souto-Manning Citation2014, 162), the employment of CNA proved to be crucial in investigating internal perceptions on the neighbourhood, which are inevitably the result of different discourses influencing each other also at conversational level.

The analysis of primary data from interviews and focus groups took place on NVivo and followed an inductive two-steps procedure focused on the discourse produced (CDA) and reproduced (CNA) by the research participants (Waitt Citation2010). The descriptive round of coding entailed first the organisation of the collected material, including the photographs from the PPM, into the three main topics discussed during data collection and in relation to the three groups of participants. Secondly, the data were coded using the interplay of four different strategies in support of the discourse and textual analysis: Thematic Coding; Values Coding; In Vivo Coding; Emotion Coding (Saldana, Citation2016). Thematic and In Vivo coding consisted in identifying both latent and manifest themes described by participants when talking about their neighbourhood. Values Coding allowed to distinguish participants’ statements into ‘Positive aspects’, ‘Negative aspects’, and neutral aspects (‘Now and Then’) of their area over time. Whilst participants’ emotions were considered specifically when analysing the last part of interviews/focus groups, that is the reactions and comments to the territorial stigma perceived by residents (Emotion Coding). Codes were then reorganised into further macro-categories, while placing emphasis on perceptions of the neighbourhoods’ change. This further layer of discourse analysis through analytical coding allowed to categorise data into three macro-topics or dimensions that compose the internal neighbourhood reputation: (a) the perception of the changed neighbourhood; (b) the perception of the social mixing policy; (c) the perception of the external reputation. Such categorisation was repeated for each group of residents to preserve nuances and complexities in the construction of narratives, showing heterogeneity of views and experiences in the same urban area.

THE INTERNAL NEIGHBOURHOOD REPUTATION: THE VISUAL PLACE IMAGE

Empirical findings with regard to the internal neighbourhood reputations of the two case studies can be summarised as follows, considering the internal reputation as the interplay of the three levels of perceptions identified (a., b., and c.). In both urban contexts, boundaries between positive and negative perceptions are often blurred, as a third perspective on the neighbourhood’s change – the neutral reputation – makes its way through the general polarised discourse. However, findings show that local interventions have not produced consistent improvements to the internal reputation, and both urban contexts emerge as contested spaces, where either class or racial/cultural tensions for the right to the neighbourhood are central.

Ponte Lambro

Ponte Lambro results as an abandoned neighbourhood, that is still socially and spatially excluded from the city of Milan; a divided neighbourhood, where tensions see private owners vs. social housing tenants, tenants vs. tenants, ‘locals’ (or native Italians) vs. ‘non-locals’ (or racialised non-Italians); an unsafe neighbourhood, in which fear of crime is often related to the use and the control over the ‘territory’, and immigrants are identified as intruders and responsible of internal disorder and decline. Overall, Ponte Lambro’s internal reputation tends to focus on perceived negative aspects and problems affecting the area or its inhabitants, usually for extended periods of time. From a general perspective, when talking about Ponte Lambro current long-term residents are more sensitive to terms such as periferia (suburbs) and paese (town), which are used by participants firstly to proudly describe community spirit and sense of belonging, and secondly complain about spatial and social marginalisation from the rest of Milan. Former residents tend to emphasise their narrative on change, and particularly on the demographical change within the neighbourhood, especially focusing on perceived advantages and disadvantages of the presence of immigrants. The newcomer provided a third perspective focusing on local resources for the future of Ponte Lambro and held a more optimistic view. Current and former long-term residents shared limited satisfaction with short and long-run effects of CdQ; while the plans of regeneration were able at the time to attract newcomers. With reference to the external reputation, participants often referred to past or recent episodes of various forms of perceived discrimination and stereotyping related to the neighbourhood, affecting education, the workplace, housing, and services.

NDC Area

The NDC area emerges as a complex area experiencing gentrification where, despite a strong sense of neighbourliness that is still appreciated by residents, the community feels forgotten by institutions and internally divided. Gentrification, affecting both food and housing in the area, appears to play a crucial role in shaping residents’ internal reputation, leading to both benefits and disadvantages. Overall, current long-term residents tended to talk extensively about what has worsened over time or what still needs to be improved, and value community as the most important factor by which to measure their satisfaction. Newcomers provided the opposite outcome and perceived the area positively, highlighting the up-and-coming nature of the area as an inevitable development. On the other hand, former long-term residents tended to have a less polarised view about the area. Moreover, it is possible to observe a balanced perception of residents towards the NDC policy, as the many criticisms were mostly counterbalanced by appreciations of the improvements that it enabled as well as by stories on the policy’s actions and organisation. Current long-term residents and newcomers believe that the external reputation does not correspond to the reality of the area and that the local newspaper plays a significant role in dictating such stigma only focusing on local problems, without giving enough credit to positive news. Former residents feel the stigma can still be found among non-residents whose view of the neighbourhood hardly corresponds to the real living experience.

For the purpose of this paper, however, the specific findings presented below refer only to the visual place images emerging from the PPM. From the thematic analysis of photographs collected and shared by participants numerous themes have been identified, which express different levels of perceiving the neighbourhoods and the use of the space (see Teixeira et al. Citation2020). Except for some instances (such as the ‘Renzo Piano project’ for Ponte Lambro, and pubs for the NDC area), the predominant focus of photographs is not on local issues, but on neighbourhood change as a more neutral aspect, which emerges as the very nature of both areas. Photographs have indeed represented a starting point for conversations and elicited further reflections on the impact of the interventions, as well as on positive and negative aspects. Among the most popular categories, three appear as central to the internal narrative of both case studies with regard to the visual place image: change, natural environment, and community.

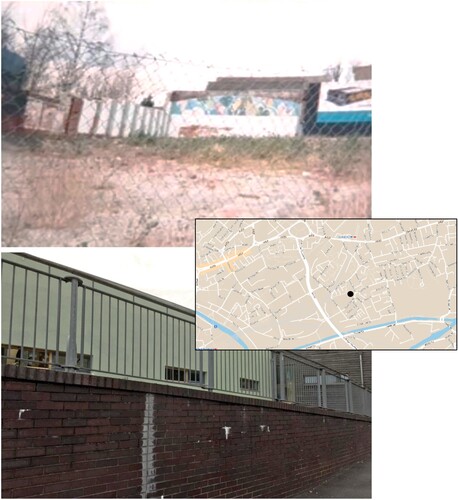

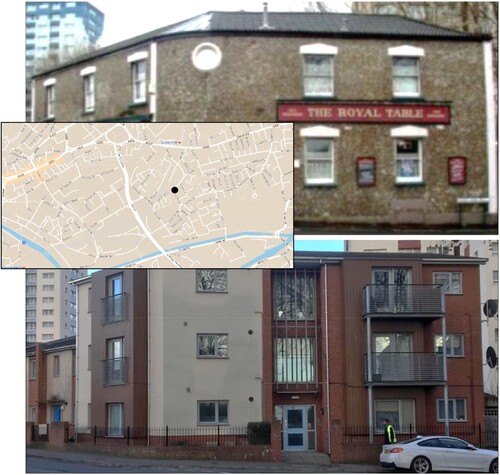

Change: Continuous Transformations Between Improvements and Disappointments

Photographs expressing change were shared by most participants across both fields, although perspectives on the same event differed and there were important nuances to consider across the three groups of residents. The interest in describing the changed neighbourhood is reflected in the great number of participants’ photographs focusing on developments, demolitions and ‘now and then’ comparisons, which in many cases include regeneration and social mixing interventions. Photomapping focused primarily on transformations in and around the neighbourhood over time: regenerations and demolitions of either streets or housing units; memories of shops and facilities; the signs of industrial and rural heritage of the local areas. Such changes are shown and were discussed not only using photographs portraying the neighbourhood in the recent past, but also, in some instances, with ‘now and then’ collages created by participants on their own initiative. When walking along via Ucelli di Nemi, the incomplete project of Laboratorio Renzo Piano, or as residents refer to it, ‘ponte (bridge) di Renzo Piano’, is imposing right in the middle of the street, connecting the two social housing blocks. What was meant to become the symbol of innovation and social mixing in the heart of the neighbourhood, was left uncomplete, and has turned into a permanent construction site (). Renzo Piano’s bridge appears to be doomed to the same destiny of other empty buildings, as BarbaraFootnote5 observes here: an attempt to develop a great and expensive project that ended up being an abandoned construction site attracting littering, drug dealing, and squatting. Her comparison also indicates a sense of disenchantment with regard to investments and infrastructures in the neighbourhood, which often fail to meet expectations and plans.

It [Renzo Piano’s bridge] was a bit like the hotel, the one of the 90s, the famous hotel they demolished, never completed. And you always think, they try, but then eventually nothing comes up from that. (Barbara, former long-term resident, 50–60)Footnote6

The Baths were demolished in 1997, and as a child I played on the wasteland and would build a den with my friends behind the advertising billboard that is seen on the right-hand corner of the photo used in the comparison shot. The new Barton Hill Academy now stands on the land where the Baths and the old Barton Hill Primary School used to stand. (Markus, current long-term resident, 30–40, Barton Hill)

Then there is another side that I like, this one on via Umiliati where there were outdoor laundries along the river. There flows the river Lambro and in the past people used to go to via Umiliati to wash their clothes. Picture yourself ladies with baskets full of dirty clothes walking towards the river to wash them. There was this dock where everyone would go and wash their clothes. Nice. [smiling] (Fabrizio, current long-term resident, 40–50)

Natural Environment: Parks and Community Gardens as Resources for the Neighbourhood

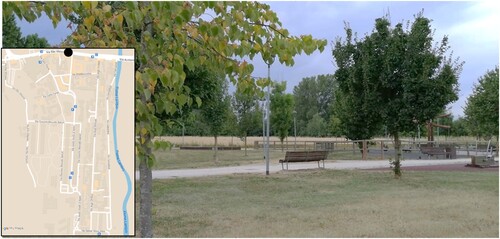

The green areas around the river Lambro, from which the neighbourhood takes part of its name, feature extensively in the photomapping discussions. Whereas parks, community gardens, as well as the Feeder Canal in the southern part of Barton Hill are also very common subjects photographed by participants, indicating a strong interest and attachment to the area’s natural environment. One of these green areas in Ponte Lambro, certainly the most mentioned one, is Parco Vittorini (), which current and former long-term residents enjoy notably as source of clean air, a pleasant meeting and recreational place for everyone. The large park, that extends along via Vittorini in the northern side of the neighbourhood, including the surrounding fields for agricultural use as well as new cycle and pedestrian paths, was inaugurated in 2013, after the demolition of the so-called ecomostro (architectural monster and source of urban decay). In 1989, a 300-rooms massive hotel started to being built on the site for the 1990 Football World Cup, but was never completed, leaving 240 thousand sqm of environmental and urban decay for more than 20 years (Comune di Milano Citation2022). The former hotel was demolished in 2012 and the area regenerated to make room for a long-awaited urban park, wheat fields and a WWF natural reserve (WWF Sud Milano).

This regeneration gives the idea that in the suburbs you can see something beautiful. You don’t need to go to the city centre to find a nice green area. (Rachele, current long-term resident, 50–60)

PHOTO 3. ‘Lavanderie Pome’, via Umiliati 20 – Pome’ outdoor laundries, via Umiliati 20’ (Source: Carlo, current long-term resident, 50–60).

Community: From Lost to Renewed Sense of Belonging

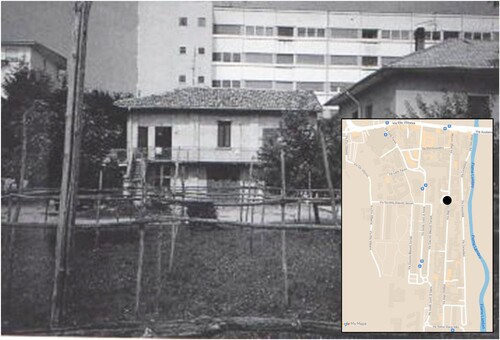

Photographs expressing community spirit from different perspectives are common across the three groups of residents in both field sites but are predominant among current long-term residents. To this category belong not only community centres and facilities providing core services to the whole area, but also examples of social participation and solidarity within the community. The most mentioned sites in Ponte Lambro include the local church and oratory, where many participants used to spend their free time with friends in the past years; and the community (C.A.M.) and youth centres (C.A.G.) (), which have always been very active in the organisation of workshops and events, and in the support of local young students with afterschool and job placement programmes.

The sudden end of the policy funding in 2016 has meant that the social activities, festivals, and events organised by the community centre responsible for the delivery of CdQ, Laboratorio di Quartiere, that used to involve the entire community have stopped or at least considerably decreased in the following years. The end of neighbourhood festivals and community engagement led to an increasing state of abandonment and quietness according to Volontario Sottovoce (current long-term resident, over 60) who talks about those years with nostalgia ().

These pictures show the change in the neighbourhood where local associations and institutions enabled us to do that. And so, people would come together, share moments together, children would come and play, we would help them out, be involved in the organisation and this was perhaps the best moment of the neighbourhood. Those years were the most beautiful years. (Volontario Sottovoce, current long-term resident, over 60)

PHOTO 8. ‘La serenità del quartiere – The neighbourhood's serenity’ (Source: Volontario Sottovoce, current long-term resident, over 60).

PHOTO 9. ‘The heart of Barton Hill, Ducie Road’ (Source: Shaila, current long-term resident, 25–30, Barton Hill).

Moreover, the shift from a predominantly white working-class to an ethnically diverse neighbourhood is reflected in the use of the space by residents and how it has evolved for the community since early 2000s. Saturday G reflects here on the causes of such change while talking about the Lord Nelson pub ():

Lord Nelson is a pub that is now derelict. So, it's no longer functioning as a pub, that's because of the change in the demographic in this area. The people that went to pubs are no longer in the demographic and demographic has changed quite substantially over, I would say, the last 10, 15 years. (Saturday G, newcomer, 40–50, Barton Hill)

CONCLUSION: REMOTE PPM AS CHALLENGE AND OPPORTUNITY

This paper, based on the qualitative and comparative research conducted in the context of my PhD, has focused on outlining how remote PPM, as a creative and collaborative method, can explore and allow the building of internal neighbourhood reputations in disadvantaged urban areas affected by change. The combination of CDA, CNA, and thematic analysis to investigate internal neighbourhood reputations from the PPM allowed this research to uncover meanings and internalised perceptions in interactions with research participants. Such methods of analysis were applied in an innovative way for a qualitative research project, that is in a longitudinal and comparative approach. Challenging the recommendations of Permentier, van Ham, and Bolt (Citation2008) and Lees (Citation2004), this research has offered an original perspective on the study of neighbourhood reputations, which involved the qualitative comparison of place narratives not only across space (Ponte Lambro, Milan and NDC area, Bristol), but also across time (pre and post intervention of the social mixing policies), providing an in-depth analysis of neighbourhood change.

Travel and social distancing restrictions due to the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic imposed critical changes to both my methodology and ethics, bringing challenges and opportunities to the research design. As participants’ recruitment could happen predominantly remotely and not door by door, I am aware that it very likely excluded vulnerable and marginal local groups that were struggling during lockdowns or had limited access to internet connections or information. To reach a more diverse demographic sample, that would suitably represent the population in both field sites, I sought support from local community centre and institutions, which made me even more aware of the socio-cultural contexts I was researching: for instance, calls for participants were translated in Somalian exclusively for the NDC area (with the help of the leader of the Bristol Somali Community Association), whereas for both case studies I offered interested participants the possibility to run the interview in any of the languages I speak (Italian, English, French). However, although social distancing made both recruitment and data collection challenging, it also provided some advantages along the way, as circumstances encouraged qualitative researchers to develop resilience and explore alternative methods of research and participants engagement (Gratton, Fox, and Elder Citation2020; Partlow Citation2020). On the one hand, in-person interviews and focus groups would have helped create a deeper connection with participants, hence a greater level of trust with me as the ‘privileged and outsider researcher’ (Bryman Citation2012; Dowling Citation2010). On the other hand, remote interactions allowed not only to reach former residents currently living far from the area, but also to record and transcribe online meetings with more ease, as Zoom enabled – at least for the English language – automatic transcription (Partlow Citation2020).

Overall, this research project contributes to the literature of discourse and territorial stigma by introducing the idea that discourses and policies can be mutually influential and that this can lead to crucial socio-economic implications (see also Department for Work and Pensions Citation2010; Permentier, van Ham, and Bolt Citation2008; Slater Citation2021): neighbourhood change can affect reputation, and stigmatised areas can be targeted by urban policies; internal and external reputations are also powerful in influencing each other, determining or maintaining spatial discrimination and exclusion (Arthurson Citation2013). Furthermore, this study provides insights into broader and timely discussions around participatory planning for urban renewal, and more specifically highlights the contradictions of this strategy when, in many cases, community participation tends to be reduced to consultations, rather than active co-design and co-production of public space, as social mixing policies have long claimed to provide (see Edwards and Imrie Citation2015; Monno and Khakee Citation2012). Such critique of the social mixing ideals is informed particularly by the analysis of residents’ perceptions from the internal neighbourhood reputations, who denounced the temporary and insufficient interest in the community (or, better, communities), leaving them with disappointment and abandonment as well as political disenchantment.

More specifically, this paper also contributes to the literature on participatory research and visual methods, as it explores internal reputations in relation to neighbourhood change through the lens of PPM created with the collaboration of participants on two separate Google My Maps. While common PPM involve the use of GIS (Richardson et al., Citation2019) or apps, such as Esri Storymaps (Teixeira Citation2015; Teixeira et al. Citation2020) paired with in-person interviews, this study employs a digital platform, Google My Maps, to collect and locate photographs in a shared and sharable space, and while focus groups and interviews are conducted remotely. Because of its user-friendly design, high accessibility from different devices and for its extremely customisable features, Google My Maps, proves to be a simple but effective tool to undertake PPM at a distance. Despite becoming an optional and remote activity in this project, PPM demonstrates to be an engaging method, that brought participants together through creativity and, because of its asynchronous and online setting on Google My Maps, it enabled to establish an open-ended dialogue with participants: some participants sent their photographs and contributed to the map even after the meeting itself. Numerous participants provided positive feedback on the PPM and were enthusiastic to present their own photographs about the neighbourhood together with stories and memories from the past: the activity turned to be an opportunity for many to spend time outdoor during social distancing while exploring the neighbourhood; the exchange of information and points of view about the history and the present of the area enabled to visit the neighbourhood while staying home and discover unknown spots, or to deconstruct the biases of residents themselves towards specific areas. The practice of taking pictures and locating them in the space was an opportunity for participants to ‘take control’ over the place image – often dominated by the public discourse – and reflect on the space they are or were inhabiting, by looking at phenomena of change under a different light and considering the use of the neighbourhood as individuals as well as part of a community (Rose Citation2016; Teixeira et al. Citation2020).

I didn't realize how much I have internalized the significance of pubs until I was actually asked to take pictures. (Angst-on-the-Moon, newcomer, 30–40, Redfield)

Finally, although Covid-19 restrictions related to travels and social distancing represented a critical challenge for the research design, they offered at the same time the opportunity to activate creativity and explore new forms of interaction and collaboration with participants. While differing from the in-person setting that was initially envisioned, the PPM still allowed the active sharing of photographs among participants, hence the collective construction of meanings and perspectives associated to the neighbourhoods during interviews and focus groups (Kara Citation2015; McIntyre Citation2003), all in a relaxed and interactive environment. Either in times of crisis or when data collection faces obstacles and in-person PPM is not possible, the remote use of this creative tool of investigation can offer a variety of potentials, while drawing connections between the spatial element – the use of the local space – and the more introspective element of neighbourhood communities – the perception and feeling of the place. This project seeks to promote the important role of participatory research (and policymaking) specifically through visual methods, to consider voices and experiences of residents directly affected by urban regeneration, whose view tends to be involved at the start of interventions but in most cases ends up being forgotten with time. Consistent and continuous assessment of social impact emerges as necessary in urban contexts of high deprivation and territorial stigma, in order to prevent the spread of further internal tensions and new forms of inequality.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to the community centres and the research participants from Ponte Lambro and the NDC neighbourhoods for having devoted their time and energy to this study, and for permissions to disseminate the results and use their photographs.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Giada Casarin

Giada Casarin is currently a research associate at the School of Geographical Science, University of Bristol, and a teaching assistant at the Urban Studies Department of the Politecnico of Milan. She is an urban geographer interested in spatial inequalities, urban regeneration, and participatory methodologies.

Notes

1 With the New Deal for Communities area I refer to the following neighbourhoods in East Bristol inner-city invested by the New Deal for Communities (2000–2011): Lawrence Hill, Barton Hill, Redfield, The Dings.

2 Critical Discourse Analysis was carried out on the local newspapers of La Repubblica Milano and Corriere della Sera (Milan) and The Bristol Post (Bristol), comparing the early 2000s and post-intervention years (2017–2019).

3 This research has been reviewed and approved by the ‘School of Geographical Sciences Research Ethics Committee’, University of Bristol, on October 20th, 2020 – reference: RE-B-CASARIN-20201020.

4 On a few occasions, I took pictures on behalf of some former residents and participants with limited mobility or time availability.

5 Pseudonyms were selected by or negotiated with participants to include them even more in the decision-making process.

6 Hereinafter, quotes related to the Italian case study are my original translation from interview and focus group transcripts.

References

- Agustoni, A., A. Alietti, and R. Cucca. 2015. “Neoliberismo, Migrazioni e Segregazione Spaziale.” Politiche Abitative e Mix Sociale nei Casi Europeo e Italiano, Sociologia Urbana e Rurale 106: 118–136.

- Arthurson, K. 2013. “Mixed Tenure Communities and the Effects on Neighbourhood Reputation and Stigma: Residents’ Experiences from Within.” Cities 35: 432–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2013.03.007.

- Arthurson, K., I. Levin, and A. Ziersch. 2015. “What is the Meaning of ‘Social Mix’? Shifting Perspectives in Planning and Implementing Public Housing Estate Redevelopment.” Australian Geographer 46 (4): 491–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2015.1075270.

- Bacqué, M. H., Y. Fijalkow, L. Launay, and S. Vermeersch. 2011. “Social Mix Policies in Paris: Discourses, Policies and Social Effects.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 35 (2): 256–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00995.x.

- Bakare, G. O. and G. D. James. 2022 "Remote Ethnography: Using Photo-Elicitation as an Alternative to Participant Observation in a Study of Urban Livelihoods in Nigeria." In Sage Research Methods: Doing Research Online. London: SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529603200

- Barker, R., S. Rowland, C. Thompson, K. Lock, K. Hunter, J. Lim, and D. Marks. 2022. “Ties That Bind: Young People, Community and Social Capital in the Wake of the Pandemic.” SSM – Qualitative Research in Health 2 (100155): 1–10.

- Barwick, C. 2018. “Social mix Revisited: Within- and Across- Neighbourhood Ties Between Ethnic Minorities of Differing Socioeconomic Backgrounds.” Urban Geography 39 (6): 916–934. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2017.1405690.

- Bolt, G., R. Van Kempen, and J. Van Weesep. 2009. “After Urban Restructuring: Relocations and Segregation in Dutch Cities.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 100 (4): 502–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.2009.00555.x.

- Bristol City Council. 2018. “The Population of Bristol”, December 2018. Accessed January 15, 2021. www.bristol.gov.uk/population.

- Bryman, A. 2012. Social Research Methods. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Calvaresi, C. and L. Cossa. 2011. Un ponte a colori. Accompagnare la rigenerazione di un quartiere di periferia milanese. Rimini: Politecnica, Maggioli Editore.

- Carpenter, J. 2022. “Picture This: Exploring Photovoice as a Method to Understand Lived Experiences in Marginal Neighbourhoods.” Urban Planning 7 (3): 351–362. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v7i3.5451.

- Cheng, Y.-W. 2021. "Sleepless in Taipei: The Application of Photovoice Method to Explore the Major Challenges Perceived by Homeless People Facing Multifaceted Social Exclusion." Critical Social Policy 41 (4): 606--627. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018320981849.

- Chetty, R., N. Hendren, and L. F. Katz. 2016. “The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children: New Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment.” American Economic Review 106 (4): 855–902. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20150572.

- Community at Heart. 2005. Revised Strategic Plan 2005–2010. Bristol: Community at Heart.

- Comune di Milano (Milan City Council). 2011. I dati del censimento 2011 a Milano. Le schede territoriali sui Municipi, NIL e Aree di Censimento. Settore Statistica. Milano. Accessed February 25, 2022. http://www.comune.milano.it/wps/portal/ist/it/amministrazione/datistatistici/indicatori_Censimento_2011.

- Comune di Milano (Milan City Council). 2022. Quartiere Ponte Lambro. Sgomberato lo stabile di proprietà comunale in via Ucelli di Nemi. Ufficio Stampa. Milano. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://www.comune.milano.it/-/quartiere-pontelambro.-sgomberato-lo-stabile-di-proprieta-comunalein-via-ucelli-di-nemi?fbclid=IwAR0yIufDqKI91ogruVFxl8WztaHxcbNBFhpkE2yK6-S14gwuS06w44KdSdc.

- Corbett, J. 2009. Good Practices in Participatory Mapping, A Review Prepared for the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). Rome: IFAD.

- DeLuca, S., and T. Rosenblatt. 2010. “Does Moving to Better Neighborhoods Lead to Better Schooling Opportunities? Parental School Choice in an Experimental Housing Voucher Program.” Teachers College Record 112 (5): 1443–1491. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811011200504.

- Department for Work and Pensions. 2010. Postcode Selection? Employers’ Use of Area and Address-Based Information Shortcuts in Recruitment Decisions, Research Report No 664.

- Dowling, R. 2010. “Power, Subjectivity and Ethics in Qualitative Research.” In Qualitative Research Methods in Human Geography, edited by I. Hay, 26–39. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dunn, K. 2001. “Representation of Islam in the Politics of Mosque Development in Sydney.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Social Geografie 92 (3): 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9663.00158.

- Edwards, C., and R. Imrie. 2015. The Short Guide to Urban Policy. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Fairclough, N. 1992. Discourse and Social Change. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Fairclough, N. 2003. Analysing Discourse, Textual Analysis for Social Research. London: Routledge.

- Foucault, M. 1981. “The Order of Discourse.” In Untying the Text: A Post-Structuralist Reader, edited by R. Young, 48–78. Boston, London and Henley: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Garbin, G., and G. Millington. 2012. “Territorial Stigma and the Politics of Resistance in a Parisian Banlieue: La Courneuve and Beyond.” Urban Studies 49 (10): 2067–2083. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098011422572.

- Gratton, N., R. Fox, and T. Elder. 2020. “Keep Talking: Messy Research in Times of Lockdown.” In Researching in the Age of COVID-19: Volume II: Care and Resilience, edited by H. Kara and S. Khoo, 101–110. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Hastings, A. 2000. “Discourse Analysis: What Does It Offer Housing Studies?” Housing, Theory and Society 17 (3): 131–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036090051084441

- Howlett, M. 2020. “Looking at the ‘Field’ Through a Zoom Lens: Methodological Reflections on Conducting Online Research During a Global Pandemic.” Qualitative Research 22 (3): 387–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794120985691.

- Huckin, T. N. 1997. “Critical Discourse Analysis.” In Functional Approaches to Written Text: Classroom Applications, edited by Tom Miller, 78-92. Washington, DC: English Language Programs United States Information Agency.

- Jacobs, K. 2006. “Discourse Analysis and its Utility for Urban Policy Research.” Urban Policy and Research 24 (1): 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111140600590817.

- Jeon, Y., and S. Kim. 2023. “Fear of Vacant Houses: Analyzing Perceptions on Housing Abandonment in Shrinking Inner-city Neighborhoods.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 38 (3): 1819–1842. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-023-10018-0.

- Jones, A., and P. Dantzler. 2020. “Neighbourhood Perceptions and Residential Mobility.” Urban Studies 00(0): 1–19.

- Kara, H. 2015. Creative Research Methods in the Social Sciences, A Practical Guide. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Kearns, A., O. Kearns, and L. Lawson. 2013. “Notorious Places: Image, Reputation, Stigma.” The Role of Newspapers in Area Reputations for Social Housing Estates, Housing Studies 28 (4): 579–598.

- Keats, P. A. 2009. “Multiple Text Analysis in Narrative Research: Visual, Written, and Spoken Stories of Experiences.” Qualitative Research 9 (2): 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794108099320.

- Lam-Knott, S. 2020. “Reclaiming Urban Narratives: Spatial Politics and Storytelling Amongst Hong Kong Youths.” Space and Polity 24 (1): 93–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2019.1670052.

- Lees, L. 2004. “Urban Geography: Discourse Analysis and Urban Research.” Progress in Human Geography 28 (1): 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132504ph473pr.

- Liebenberg, L. 2019. “Thinking Critically About Photovoice: Achieving Empowerment and Social Change.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 17: 1–9.

- MacLeavy, J. 2009. “(Re)Analysing Community Empowerment: Rationalities and Technologies of Government in Bristol’s New Deal for Communities.” Urban Studies 46 (4): 849–875. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098009102132.

- McIntyre, A. 2003. “Through the Eyes of Women: Photovoice and Participatory Research as Tools for Reimagining Place.” Gender, Place and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography 10 (1): 47–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369032000052658

- Mendenhall, R., S. DeLuca, and G. Duncan. 2006. “Neighborhood Resources, Racial Segregation, and Economic Mobility: Results from the Gautreaux Program.” Social Science Research 35 (4): 892–923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2005.06.007.

- Monno, V., and A. Khakee. 2012. “Tokenism or Political Activism? Some Reflections on Participatory Planning.” International Planning Studies 17 (1): 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2011.638181.

- Moreira de Souza, T. 2019. “Urban Regeneration and Tenure mix: Exploring the Dynamics of Neighbour Interactions.” Housing Studies 34 (9): 1521–1542. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1585520.

- Partlow, E. 2020. “Prioritizing Inclusion, Ethical Practice and Accessibility During a Global Pandemic: The Role of the Researcher in Mindful Decision Making.” In Researching in the Age of COVID-19: Volume II: Care and Resilience, edited by H. Kara and S. Khoo, 121–130. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Permentier, M., G. Bolt, and M. van Ham. 2011. “Determinants of Neighbourhood Satisfaction and Perception of Neighbourhood Reputation.” Urban Studies 48 (5): 977–996. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098010367860.

- Permentier, M., M. van Ham, and G. Bolt. 2007. “Behavioural Responses to Neighbourhood Reputations.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 22 (2): 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-007-9075-8.

- Permentier, M., M. van Ham, and G. Bolt. 2008. “Same Neighbourhood … Different Views? A Confrontation of Internal and External Neighbourhood Reputations.” Housing Studies 23 (6): 833–855. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030802416619.

- Richardson, T. 1996. “Foucauldian Discourse: Power and Truth in Urban and Regional Policy Making.” European Planning Studies 4 (3): 279–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654319608720346.

- Richardson D. M., H. Pickus, and L. Parks. 2019. "Pathways to Mobility: Engaging Mexican American Youth Through Participatory Photo Mapping." Journal of Adolescent Research 34 (1): 55–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558417713303

- Rose, G. 2016. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials. London: Sage Publications.

- Saldana, J. 2016. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. London: Sage Publications Inc.

- Slater, T. 2021. “The Production and Activation of Territorial Stigma.” In Shaking Up the City, Ignorance, Inequality, and the Urban Question, edited by T. Slater, 137–163. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Souto-Manning, M. 2014. “Critical Narrative Analysis: The Interplay of Critical Discourse and Narrative Analyses.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 27 (2): 159–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2012.737046.

- Teixeira, S. 2015. “It Seems Like No One Cares”: Participatory Photo Mapping to Understand Youth Perspectives on Property Vacancy.” Journal of Adolescent Research 30 (3): 390–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558414547098.

- Teixeira, S., D. Hwang, B. Spielvogel, K. Cole, and R. L. Coley. 2020. “Participatory Photo Mapping to Understand Youths’ Experiences in a Public Housing Neighborhood Preparing for Redevelopment.” Housing Policy Debate 30 (5): 766–782. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2020.1741422.

- Töppel, M., and C. Reichel. 2021. “Qualitative Methods and Hybrid Maps for Spatial Perception with an Example of Security Perception.” Urban Planning 6 (1): 105–119. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v6i1.3614.

- Van Auken, P. M., S. V. Frisvoll, and S. I. Stewart. 2010. “Visualising Community: Using Participant-Driven Photo-Elicitation for Research and Application.” Local Environment 15 (4): 373–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549831003677670.

- Wacquant, L. 2007. “Territorial Stigmatization in the age of Advanced Marginality.” Thesis Eleven 91 (1): 66–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0725513607082003.

- Waitt, G. 2010. “Doing Foucauldian Discourse Analysis – Revealing Social Identities” in Qualitative Research Methods in Human Geography, edited by I. Hay, 217–240. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Watt, P. 2008. “Underclass’ and ‘Ordinary People’ Discourses: Representing/re-Presenting Council Tenants in a Housing Campaign.” Critical Discourse Studies 5 (4): 345–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405900802405288.