ABSTRACT

Outdoor learning through its immersive experience can be an avenue for critical inquiry in artmaking. Malaysian artists Piyadasa and Suleiman claim artists have not engaged in critical thinking and have become craftsmen instead of thinkers. Artmaking becomes concerned with superficial form, technique and style rather than content. The art education in Malaysian schools has emphasized the technical ‘know-how’ of art production with little critical inquiry, focusing on the end product of art as craft and not a thinking process. Outdoor learning, through the context of time and place as social materials, aims to inculcate critical thinking and develop a student’s voice and Malaysian identity. Redefining outdoor learning as sites of memory, this paper presents four types of spaces: physical space in natural and urban environments, communicative space, collaborative space and media space through an art gallery, as ways of integrating artistic thinking and developing a Malaysian identity through art education.

Introduction

Outdoor learning through its immersive experience can provide a sense of time and place for critical inquiry in artmaking. Prominent Malaysian artists Pidayasa and Suleiman (Citation1974) claim there is a void of critical debate of ideas within the local art scene. Artmaking is largely a ‘picture making’ rather than ‘problem-solving’ activity. Many artists are concerned with form, superficial style and technique rather than content. The lack of an intellectual tradition is attributed to the old notion: ‘artists do not have to verbalise on or justify their work,’ which results in a complacent assumption that artists are essentially craftsmen and not thinkers. Though the local art scene has since the 70s grown in criticality and developed into postmodernism and new forms in contemporary art (Khairuddin & Yong, Citation2013), those developments are disconnected from the Malaysian schools. The art education in Malaysian schools emphasizes the technical ‘know-how’ of art production with little critical inquiry (Hashim, Citation1989). Though renamed visual arts education (pendidikan seni visual), teaching remains focused on the final product instead of critical reflection on the process of creation (Vethamani, Citation2016). According to the National Curriculum Development Centre’s report (Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia, Citation2003), the current formal art education at the secondary school level in Malaysia emphasizes more on ‘the ability to produce artworks that look good rather than exploring its content.’ (Asmawi, Faizuan, & Leong, Citation2019). However, art history has shown that the role of art has moved from a craft and technical labour since Medieval art to artistic inquiry post-invention of photography (Stokstad & Cothren, Citation2011). Thus, art teaching should focus on the critical thinking process in artistic and intellectual rigor. This paper capitalises on the specific localities and sensorial experience in outdoor learning to nurture artistic thinking and develop a Malaysian identity in art education. Using sites of memory as an interdisciplinary approach to outdoor learning, I present four types of outdoor learning spaces: physical space in natural and urban environments, communicative space, collaborative space and media space through an art gallery.

1. Benefits of outdoor learning for art education

Outdoor environment offers a new spectrum of opportunities that can extend the indoor class and enrich learning, especially for art education. There are three aspects of art that make outdoor learning suitable; firstly in the type of knowledge, secondly as an ingredient in artmaking, and lastly as a process of artistic thinking.

If other subjects like math and science have been effectively taught within the classroom, why can’t art be taught in the same way? The cognitive knowledge in math and science subjects are empirical and objective, and therefore can be taught in a universal and decontextualized framework through memorizing, repetition and application of formulas. However, the knowledge students acquire in art is tacit, which is subjective, personalised, situated and contextualized in nature. This tacit knowledge is gained through the students’ constant engagement with the art materials in a process called material thinking (Carter, Citation2004). Unlike math and science subjects where theoretical knowledge is objective and verbally transferable, the tacit praxical knowledge in art is subjective, situated and discovered through observation, action and reflection in material thinking. Therefore, the nature of tacit knowledge in art differs from cognitive knowledge and thus warrants a different teaching approach where outdoor learning can offer great contributions.

Secondly, what are the materials needed in artmaking? To prepare for an art class, the teacher may think the only materials the students need are physical materials like pencil, paper, paints and brushes. But beyond the physical art materials, the artist requires ‘social material.’ John Dewey (Citation1934) describes the process of artistic thinking and its dependence on the human condition of context and experience, where conflict, hostility and disruption provide motivation to create art. Like Dewey, Martin Heidegger (Citation1996), also emphasizes on the importance of the social environment as ‘material’ in creating new knowledge in art. Social material may come as a physical form like objects, people and places, or a non-physical form like systems, ideas or beliefs. Don Ihde (Citation1979) claims that beyond a theoretical knowledge of art and techniques, the primary engagement in artmaking comes from a combination of tools, materials and ideas. These social material are reflections of the society’s condition, and the artist’s memories. This ties-in perfectly with the explorative nature of outdoor learning as a site for social material where learning occurs heuristically through self discovery. Therefore, outdoor learning can play a significant role by providing a contextual environment and sensorial experience to glean social material for artmaking.

Material thinking in art is a process; which is not a knowing prior to creation but a discovery from unknowing to knowing, building knowledge upon knowledge (Barret, Citation2010). Thus, art as ‘unfinished thinking’ (Borgdorff, Citation2011) makes the outdoor environment very suitable for cultivating this pre-reflective knowledge. As students experience their outdoor environment they spontaneously observe, act and get inspired to make art without following any instruction or rules. The social material provided allows them to express their relationship with the world around them by thinking in, through and with art in a ‘bodily knowledge’ (Merleau-Ponty, Citation1962).

Although indoor learning in a classroom can still achieve tacit knowledge and academic art training is still important, omitting outdoor learning entirely as a teaching platform would deprive students of a more enriching education. Outdoor learning through different types of spaces, compliments the situated heuristic learning in tacit knowledge. The outdoor learning framework provides social materials for artmaking and synthesises creation from experience. This process of combining immersive experience with material thinking elicits reflection and critical inquiry, thus nurturing the students’ individual voice and cultural identity.

2. Redefining outdoor learning as sites of memory

As much as what one learns is important, how one learns is equally important. The brain remembers different things differently, so the way to teach cognitive knowledge cannot be the same as other knowledge like affective or psychomotor. The indoor classroom is a suitable space for teaching mental, theoretical knowledge, but the variety of outdoor learning spaces outside of the classroom provides a plethora of opportunities for learning affective, psychomotor and tacit knowledge. Outdoor learning complements indoor learning because the sense of time and place enforced by our seven senses of sight, smell, taste, hearing, touch, vestibular and proprioception creates a richer sensorial experience, which aids in remembering and learning. Through the engagement of the seven senses and interactions with people and the surroundings ‘the invisible takes shape in a concrete appearance’ (Cicero & Quintilian, Citation2008, p. 19). The more immersive the outdoor learning environment is, the more concrete the ‘localisation’ of a place becomes, and the stronger the experience, memory and social material becomes.

The design of learning spaces outside of the classroom can increase the quality of learning as they create different modes of remembering. Art classes are not about cognitive memorising hard facts, data or information, rather learning occurs in the affective and psychomotor engagement of the students through different sites of memory. Physical spaces are the most common sites of memory. They come in various types and sizes, but whether they are nature, heritage sites, modern urban or rural landscapes, they all connect to different qualities of memory where meanings and values of the past are embodied in the present. As each outdoor space forms a different part of a social structure, they also embody its values in ethical, ideological, political, religious, social and economic. As spaces are inextricably linked to our activities and memory, spaces are also linked to our identity (Erll, Citation2008). Outdoor class through different types of outdoor spaces creates different sites of memory that can help students understand their society and themselves better, serving as the perfect social material for artmaking. (Marcel & Mucchielli, Citation2008)

Although the definition of outdoor means activities or things that happen outside and not in a building (Collins Dictionary), sites of memory hold many definitions which is helpful to art for its conceptual richness (Erll, Citation2008). Sites as ‘Place’ has a variety of meanings: from the physical space to medial representation, communicative memory, shared activity and shared values. From the multiple translations in different languages, Sites of memory can mean ‘the backgrounds of memory’ or as ‘centers,’ ‘knots,’ ‘crossings,’ ‘buoys’ (anchors) of memory (Cicero & Quintilian, Citation2008, p. 22). Memory also contains various meanings like ‘to learn,’ ‘to teach’ or ‘to internalize.’ Sites of memory also suggest ‘a dynamic relationship between passive as well as active attainments of learning, knowledge processing, and meaning-making … (in) a wide variety of multi-dimensional contexts’ (Harth, Citation2008, p. 85). Not only do sites of memory serve as an appropriate framework to understand the nature of memory, the definitions show the parallel relationship between ‘sites of memory’ as a conceptual structure and the neurological functions of our brain in memory. This paper explores the potential of outdoor learning space in relation to sites of memory as a multidisciplinary learning tool by looking at four types of outdoor learning spaces.

3. Cultural context & project outline

Asia has suffered an identity crisis due to many years of colonisation, and defined itself as the other, which is ‘lesser, derivative, secondary, disingenuous and inauthentic’ (Clark, Citation1993, p. 28). There is a question as to how Asia can develop their own identity in its own terms apart from the commanding Euro-American paradigms which constantly expects ‘art from the region … to reflect some “authentic” local culture devoid of Western influences’ (Sabapathy, Citation1996, p. 6). The development of Malaysian art thus far also reflects the struggle for the nation’s identity from colonial to present. This struggle culminated in the establishment of the 1971 National Cultural Policy Bumiputera Act in the aftermath of the 13 May racial riots in 1969 (Khairuddin & Yong, Citation2013). Since then, Malaysia continues in its multicultural diversity as a Southeast Asian country, with 67.4% Malays or Bumiputera, 24.6% Chinese, 7.3% Indians and 0.7% other races (Department of Statistics Malaysia, Citation2010). As Malaysia has been colonised from 1641 to 1957, it is impossible to be ‘devoid of Western influences.’ These four outdoor projects use the criteria of situated location, activity, memory and living culture of the people as sites of memory to develop the Malaysian identity.

These outdoor learning strategies are designed for young people in their fine arts and arts history class at foundation level across one semester, in a local university’s film faculty in Johor, Malaysia. Since their goal is to be filmmakers, not illustrators, and both subjects of fine arts and art history span only a short period of about three months, my expectation for the art class is basic drawing skills and not technical perfection. Instead, I focus on developing a firm understanding of design principles and artistic thinking, which is applicable for their future in any field of arts. In the journey to become a filmmaker or artist, students cannot escape grappling with the question of identity. Through the approach of designing art spaces as sites of memory, I hope to create a framework where these questions of social identity and cultural memory can be dealt with through critical inquiry in art.

My approach is to create social materials for artmaking through various art spaces. The students’ tacit knowledge depends on the amount of social material and degree of engagement in material thinking (Carter, Citation2004). Keeping the art materials and time duration constant, I vary the social materials by designing different learning spaces. While most subjects are taught entirely indoors, student-centered learning spaces are constantly evolving from indoor to outdoor, so learning is more exciting. Especially with students from diverse cultural backgrounds, changing the learning spaces also benefits as it caters to their diverse learning styles. I combined indoor and outdoor learning environments so the students’ experience of the social material gets increasingly more sensorial and interactive.

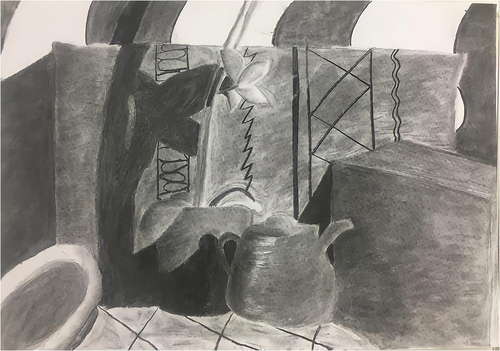

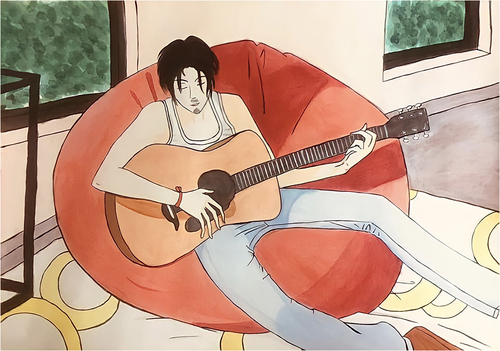

The fine art class is structured in the three genres of art- still life, portraiture and landscape, each is designed with increasing immersiveness. The first half of the classes are indoor, while the rest of the classes are entirely outdoors. For the indoor class, we begin with still life- example where a variety of objects are set on display. The next section is portraiture- example, where a scene is set up with props and a sitter. For indoor learning, the sites of memory here increase incrementally from the objects in still life to more engagement with a sitter in portraiture.

The outdoor learning spaces are designed as an extension of indoor learning. Defined as sites of memory, outdoor spaces are in antagonism to a classroom. Below are four types of outdoor learning spaces: physical space, communicative space, collaborative space and media space.

4. Physical space—natural environment

The outdoor learning for the fine art class is carried out in plein air, which is outdoor sketching. The plein air classes are a way for the students to connect place, memory and thoughts as social material in art-making. The setting of a location as a site of memory is not merely a physical space, but it embodies a duration, a history and an identity (Monk, Citation2016). Set in various parts of the city of Johor, the locations for the plein air class are each uniquely different. The first nature space is Independence Park (Taman Merdeka), which is a public recreational park built to commemorate the nation’s struggle to achieve independence; the second is Princess Harbour (Puteri Harbour), which is a part of the Iskandar South Johor revitalisation project; the last is Tan Hiok Nee heritage street which is lined with conservation shophouses built during the early twentieth century. By choosing these three outdoor locations for plein air drawing, the students experience a variety of different landscapes and architecture. Using the outdoor environment as social material also helps students reconnect with past histories, memories and present cultures buried in these sites, thereby creating an active memory in art. Using their seven senses, the students experience sites of memory in the literal sense as physical spaces, connecting both to the object of the ‘local’ in these sites and personifying them in memory through art (Monk, Citation2016).

The objective of the outdoor plein-air is to increase the social material by moving from distant subject matters in still life and portraiture to a complete immersion of a physical environment in nature. After a lecture on an art principle, students explored the outdoors freely where they engaged with their subject matter not just visually, but through their seven senses. Personal coaching came afterwards when students returned with their plein-air sketches for discussion prior to painting of artwork.

Student A—tree of life

I was overwhelmed by this huge tree in the park. I wanted to depict the comforting feeling of being protected by its huge arms and dense leaf covering. I learnt more techniques on acrylic painting from a YouTube video.

The immersive natural environment creates a stronger memory with its sensorial experience. Concept: In , Student A depicts the beauty of nature through a realistic and detailed portrayal of a giant tree. With the entire page engulfed by the foliage, Student A conveys the feeling of strength and comfort being embraced by the largeness of its canopy. Technique: using detailed realism and vibrant colours, she depicts the tree full of liveliness and peace.

Student B—Trees and Lake

I explored the whole park and finally found the perfect view climbing the bird watching tower. I wrote a poem to express my feelings- ‘A thousand flying leaves cover this garden in the city, where many gather to see its beauty.’ This is my first time using the wet-on-wet technique taught in class, so I almost tore the paper. I am learning to control the amount of water and successfully applied the sprinkle technique in this painting.

Concept: In , Student B depicts the park from a bird’s eye view as an expansive romantic space. Technique: using soft pastel colours, she portrays a warm lighthearted feeling as an expression of her outdoor experience. She used ‘gong bi’ (brushwork) technique drawn from her Chinese culture to depict the Malaysian park in a Chinese painting style. Her adoption of the Chinese painting style reflects Malaysian Chinese’s stronger affinity to their racial roots than the national Malay culture.

Student C—By the River

Figure 3b. Student D. Janlan Kaki (The Walk). 2018. Acrylic on paper. 42 × 59.4 cm. c) Student E. Desolate. 2018. Acrylic on paper, 42 × 59.4 cm.

As I sat by the park’s lake sketching, the peaceful lake and gentle swaying of the trees caused me to contemplate my future. The colourful fallen leaves represent the different thoughts I had and I used soft pastel colours to convey my feelings of peace.

Concept: In , Student C depicts her self-portrait in metaphors- the swaying branches are like her thoughts, the fallen leaves are her ideas that accompany her as she sat alone. Technique: the use of gestural lines creates an intimate portrait and the blues and greens reflect her thoughtful contemplation. The composition with her body facing away brings the focus not on her face or beauty, but on her act of contemplation for her future. Her non-focus on beauty could be a reflection of the Muslim’s values of conservatism in line with the wearing of tundung head-covering for women.

Student D—The walk

As I walked around the harbour, many thoughts about my life and future sprang into my mind. Looking up at the trees and the sea, I felt hopeful for a bright future. But looking down at the fallen leaves, I was fearful of the fragility of life. So I titled my art ‘Jalan Kaki’ (The Walk) as a double meaning for the walk I took in Puteri Harbour but also my walk in life. Despite not knowing what lies ahead, I want to walk bare feet and feel the fullest of life.

Concept: In , The outdoor experience became Student D’s material for reflection, where the setting triggered thoughts of hope and fear in her life journey. She depicts herself in bare feet to symbolise both vulnerability and courage to face the future. Technique: drawn in a realistic style with soft brushstrokes in fine detail, ‘Jalan Kaki’ embodies her reflections in life through poetry and symbolism.

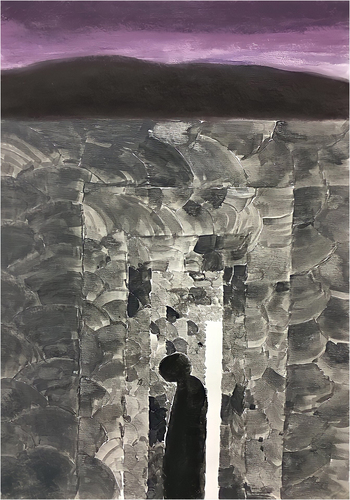

Student E—Desolate

As I walked through the series of stone arches in the park, I felt myself enclosed and trapped by the space. I did another sketch to describe my feeling using overlapping stones in concentric circles.

Concept: Unlike most students’ depiction of a peaceful retreat into nature, Student E’s artwork in expresses melancholy and depicts night though the trip was daytime. The physical space in art becomes an expression of his inner reality. Technique: the deep purple sky symbolises isolation and through repetition of the stone arches, the closed space creates a claustrophobic feeling.

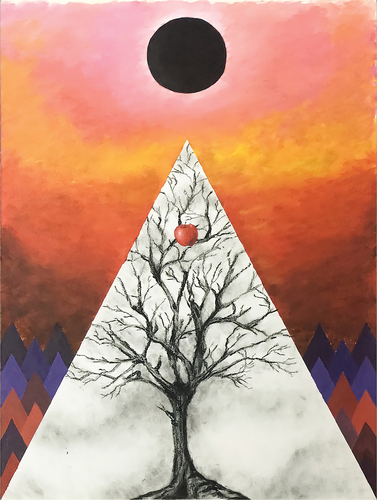

Student F—A Poison Tree

I connected my experience in the park with William Blake’s poem ‘A Poison Tree,’ which describes how anger can grow like a tree till it kills someone like poison. I used a red apple, a withered tree, a black sun and triangles as symbols to convey the complex emotions of suppressed anger and hate.

Concept: In , Student F combines his outdoor experience with a poem and deploys an illusionistic composition of trees as a metaphor for anger. Technique: he creates tension by contrasting psychedelic colours with negative white space in abstraction.

Evaluation

Successes:

The nature plein-air class increased students’ motivation as being soaked in the peaceful nature was a welcome change from the school desk. For example Student E was the weakest student in his class, but as we transitioned from indoor to outdoor learning, he showed an improvement in attitude. This shows how outdoor learning, as a student-centered environment, has been successful to motivate students to direct their own learning and develop self discipline. Secondly, this process allowed midway intervention of the teacher during students’ composition study, to give personal coaching to develop their social material. Guided through prior discussions with the teacher, the resulting artworks were not unthinking regurgitations of forms and style. The internalised experience of being in nature and their reflected response in art had stronger concepts and content compared to indoor art. Through exposure to nature, the ‘unfinished thinking’ was worked out through eye, hand and mind in material thinking (Carter, Citation2004) as a fusion of context, problem and solution.

Difficulties and failings:

As this process of outdoor learning gave students freedom to direct their own learning, it required more hard work from students to reflect and create their own solution in subject matter, composition and style. Although most students were excited by this process, a few students’ artwork lacked reflection. Also, as more time was taken up in travelling and outdoor exploration, less time was spent supervising the students’ artmaking. Thus, the artworks were made during independent learning, so a few artwork showed promise but lacked technical competency in execution. Some students did independent research on YouTube to solve technical questions. Lastly, outdoor learning required more planning from the teacher, with more administrative work for transport arrangement, students’ consent forms, location recce and also a back-up class plan in case of weather change.

5. Communicative and Physical Space—Urban Environment

This urban plein-air class constitutes the final project and seeks to portray the diverse lives and rich culture of the people in Johor. The students travelled all over downtown Johor, exploring the different sites, meeting and talking to different people, travelling from Tan Hiok Nee heritage street, Danga Bay, right to the Singapore-Johor Woodlands Causeway bridge; a bonus location included the Melaka River. Over a number of trips, students observed life, and drew inspiration from the different people they encountered at cafes, shops and places of worship. The people they conversed with, ranging from a ticket-counter clerk to a second generation café-owner, each carried with them personal stories, memories, current issues and all expressed the different facets that make-up the heart-beat of the city. From the conversations, interactions and sketches in the urban city, students created artwork that depicts the essence of Malaysians through contemporary narratives. Through outdoor learning, not only are students exposed to a physical environment as a site of memory, but the human interaction and communicative memory (Assmann, Citation2008) shared through conversations creates new sites of memory.

Student G—Urban Birds

This was my first time in Tan Hiok Nee and this scenery was, to me, the most interesting out of all the sketches and photos I took. There’s not much to it- there were a lot of birds, a lot of poop on the roads and a lot of colourful buildings. I found it odd and sort of gross, but I really liked it so I painted it.

Concept: Tan Hiok Nee is a famous heritage site, but Student G creates a realistic portrayal of observed life there in . Technique: He portrays empty streets with a lot of crows resting on the pole wires; and contrasts pale pastel shophouses with its five-footway cast in deep shadows. The bright blue sky with patchy clouds and free line work expresses a light-hearted tone. At first sight, the flock of crows resting on the wires looks whimsical, but the desolate street belies a deeper issue in this tourist site.

Student H—Ignorance

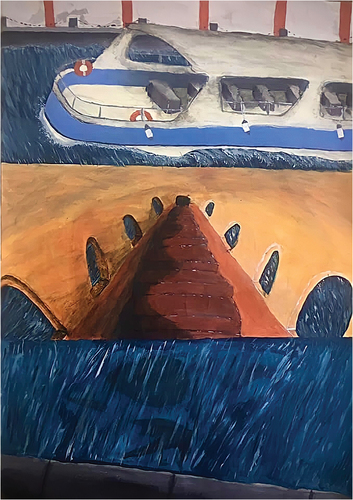

My painting was influenced by my observation as well as the films I watched during Seashorts Film Festival during this film camp. I loved the sight of the Melaka river as I frequently walked by it. I chose a sequence of contrasting cool and warm tones across the three panels and a washed-out, dirty texture in the waves to make the river stand out. Although the Melaka River is famed as a beautiful landmark, many do not know the true contents inside. I identify with this norm as a Malaysian, and drew in the last panel a dead bird buried in the water. The void of human presence in the painting symbolises a personal emptiness I feel inside.

Concept: In , Student H depicts the iconic Melaka river and its famous cruise not in its legendary glory but its actual reality. Technique: the three panels moved from objective space to subjective space. The use of contrasting space and colours creates a poetic commentary on Malaysian society through the metaphor of a dead bird in buried waters.

Student I—Money or your life

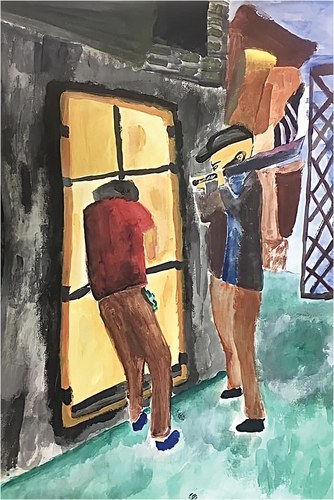

Instead of choosing the colourful facades of the Tan Hiok Nee shophouses, I explored the back alleys. Knowing about the high crime rate of theft and vandalism in the downtown zone from the news and conversations with people, I created a fictitious scene of a robbery at the alley where the robber points a knife at his victim threatening ‘Wang atau Nyawa? (money or your life)’

Concept: Although the robbery did not occur during her plein-air observation, in , Student I creates a fictional narrative of a robbery in a back-alley to express her sense of danger in downtown Johor. Technique: Her layered brush strokes, combining wet and dry brush techniques and muddy colours also increases the sense of danger in the alley.

Student J—Dream city

‘So crowded, dirty, polluted and dangerous,’ cried a 16 year old student. ‘My friend was robbed here once, so I always need company when I come here’ Upon interviewing the student at the street, I realised the good thing about downtown Johor is you can buy whatever you want, but the downside is the high crime rate. In ‘Dream City,’ I depict Johor city during the magic hour of sunset surrounded by trees like the garden city concept in Singapore. I added lights everywhere to reflect my hope for Johor Bahru becoming the brightest city in the world. Home is our dream and a feeling. I hope my dream of Johor becoming a safe, clean and beautiful city for its people will one day become a reality.

Concept: Student J loves his country and hopes it can be a safe home. Instead of depicting his city realistically as grimy and dirty with a polluted river, he portrays Johor in , as a beautiful dream city in peace and harmony. Technique: He contrasts deep blues and hot pink to bring focus to the city buildings and uses layered strokes and cascading leaves to add a dreamy look to his fantasy city. Art here not only captures his reflection towards his home country but becomes an important act of hope.

Student K—River mermaid

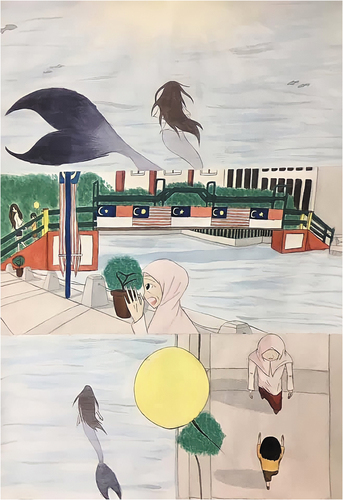

I was inspired by the Melaka River which I often pass by during our film camp. Whenever I crossed the bridge, I would hear fishes jumping up from the water, and guessed they must be playing under the bridge. But it was hard to see the fishes swimming in the river, as they always hid in the shadows. This reminded me of the mermaids always hiding in fantasy stories. So I created a story about a mermaid who helped a missing boy. But when the boy reunited with her grandmother, the mermaid’s kindness was overlooked. Just as the balloon left the boy’s hand and flew to the sky, the mermaid returned back into the dark waters alone. Although this story is a fantasy, it reflects what is happening in Malaysia. I am from a minority race in Malaysia; the mermaid, like me, is a ‘different species’ from the boy, but she is willing to help him. I have helped other races in their time of need, just as they helped me. Most people who help never asked for anything in return, the mermaid too didn’t receive any acknowledgement for her kindness. This is a way of life to live peacefully in Malaysia- help other races quietly.

Concept: in , Student K transformed her observations of activities around the Melaka river into a deeper reflection of racial relations in Malaysia in a fictional story of a mermaid. Technique: Student K’s peaceful depiction through the choice of light, warm colours portrays irony in this bittersweet story about racial difference. Her experience of ‘site’ is a crucial grounding to contextualise her social commentary and bring into coherence her imagination with her social reality.

Student L—The life of the lights

” I live alone now. My children have left me and only come back to visit me once a year.” shared the old ticket-seller. I felt sad to hear about the ticket-seller’s poverty. My hope for Johor is to see its economy improve, so I chose red and blue for the ferris wheel to depict the flag of Johor and mixed the colours outside to show the loneliness of the ticket-seller. She said that by working at the funfair she hopes to give happiness to others despite feeling dull inside. So the particles spreading from the ferris wheel reflects the happiness she spreads. I mix yellow and white to show that happiness is gold and it cannot be blocked. Even when times are rough, you can still find happiness. The dark blue reflects her bad past, and the colourful shapes represent forgetting the past and spreading happiness now. You are the light of the show, and only you can bring happiness.

Concept: Inspired by a funfair located in Danga Bay Johor, Student L creates an abstract portrait of a ticket-seller living below the poverty line in . Technique: Student K expresses emotions through colours in this abstract artwork about poverty in Malaysia. Some darker colours express melancholy, and brighter colours happiness, other colours carry symbolism of the state. Instead of figurative forms, he uses abstract forms to convey his complex emotions.

Evaluation

Successes:

Defining outdoor learning as sites of memory had two aspects in this urban environment class—physical space and communicative space. Compared to the natural environment with only environmental exposure, stronger social materials were gathered from the experience of immersive space and conversations here. Mental, emotional and bodily knowledge through personal observations and experience all contributed as social material incorporated into art as material of reflection (Dewey, Citation1934). Outdoor learning as a cultural, historical and social experience helped cultivate critical reflection on societal relations and encouraged students’ voice in response to issues in contemporary life. The exploration of space through conversations with the people in the community individualised their own experience and developed their own solution and artistic style. Unlike Students G, H and I, who created art in social realism, Students J, K and L chose imaginative fiction and abstraction as their material of reflection. By harnessing time and place in the urban environment, each student’s solution and approach was entirely unique.

Difficulties and failings:

The challenges in outdoor learning in urban plein-air were similar to nature plein-air in terms of time, admin and weather. I had to plan carefully for the project timeline and site selection to give a richer cultural context for the class. I also had to guide the students’ personally in their thought process and concept development from their plein-air sketches. Though there was more time spent outdoors, the percentage of success in this final project was higher as the immersive physical and communicative space drew more social material and stronger emotional connection.

6. Collaborative space

The first two types of outdoor learning as sites of memory explored physical space and communicative memory as a space, the next type of outdoor learning explores collaborative space. The objective of this class was to engage students in community service, and create both personal and collaborative artwork. In this community engagement, I brought the students to visit a local orphanage called Berkat Children’s Home as a way to give back to the community. The Foundation students spent an entire afternoon with the children; playing with them, talking to them, teaching them to draw and drawing with them. Some students even tied their hair and played music on the ukuleles. Though tired, the students left with a cheerful and overflowing heart. In the next semester, some students volunteered to visit the orphanage again. The orphans also asked me ‘When can you visit us again?’

There were three types of artworks produced: individual art, duo art and group collaborative art, each increasingly collaborative to reflect the bonds they shared. For individual work, the students contemplated their experience and created portraits of the children. For the duo art, each student made a drawing together with a child. In the giant collaborative drawing, everyone drew together on one giant paper cooperatively. Due to the limits of the paper, I will only introduce individual and collaborative art. The Berkat Children’s project culminated in a charity art exhibition where the students sold artwork and gave the proceeds back to Berkat Children’s Home.

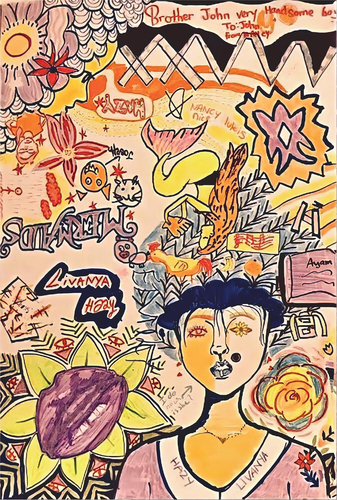

Student M—Childlike wonder

Our eyes don’t lie, they are the window to our soul. The best way to know someone is to look them in the eyes and observe what they reveal. My work was based on a photograph I took at the orphanage when this little girl caught my eye. The moment I took this picture she was looking straight at me; she didn’t shy away from me. Through this artwork, I hope to illustrate the very essence of childhood. One simple eye contact tells a thousand stories; may those who see my work rediscover their inner child.

Concept: Student M believes the eyes reveal one’s emotion and inner world and creates a portrait of the orphan’s true self. Technique: with a lot of care in the brushstrokes and a variety of colours and tones in a highly realistic style, he captures the feeling of childlike innocence in . The flexibility of site experience allowed the student to incorporate photography in his exploration.

Student N—Rebaka

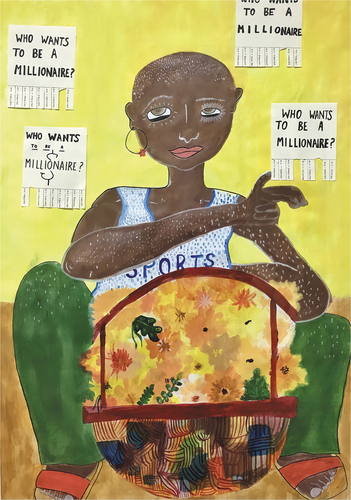

After a few minutes of conversing with the nine year old Rebeka, she popped a simple but heartfelt question, ‘Do you cry … at night before you sleep?’ Rebecca was having trouble fitting in as a new kid on the block. She often talked about escaping the orphanage. This image of the bald Indian girl sitting with her basket of flowers, came about after our in depth conversation. I drew her in a blue singlet, expressing the sadness that she feels inside. Her pants are green to symbolize growth. The yellow background takes a dip into daydream of a happier place Rebeka would rather be in. Although both her parents were abusive to her, Rebeka still missed her mother. She innocently told me that her father used to lock her up, and starved her for hours. Her parents had sent her to the orphanage as they had too many children and could not afford to raise her, thus the ‘who wants to be a millionaire’ poster.

Concept: Student N’s depiction of a girl with a flower basket alludes to the common sight of the poor selling on the streets in .

The ‘who wants to be a millionaire’ game also symbolises the poor’s illusive dream to escape their tragic life of poverty. Technique: Using lyrical lines and bright happy colours, she depicts an intimate portrait of the orphan in rich irony.Student O—Collaborative drawing

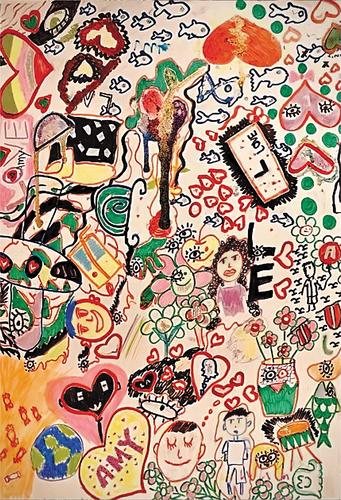

I was in my first foundation semester when we visited Berkat Children’s Home. I was a super introvert and it was very hard for me to take the initiative to talk. During the journey to Berkat, I was so anxious. I kept thinking, ‘how should I talk to the children?’ However when I reached there, I realised I worried too much. They were so cheerful and excited, and welcomed us happily. During the few hours in Berkat, we just enjoyed ourselves with the children. We shared color pencils, jokes and thoughts; their ideas were fantastic and cute. Children are the purest, I can see the sincerity in their eyes and through their drawings. Some of them even showed us their treasures. I remembered there was a girl called Amy, we were compatible and stuck together all the time and kept drawing and talking. We shared a lot of ideas, from a blank white paper, to countless colorful creatures; we also sang together. This was just a very simple activity, but we experienced joy and I am grateful to have spent my day with the orphans; the art was full of our soul and hopes.

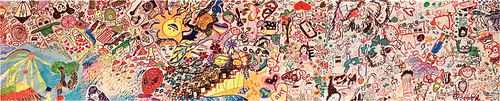

Concept: Over a couple of visits to the Home, I noticed the students created interesting art with the child they spent time with. I decided to magnify their conversations and interactions through a shared performative activity shown in

, as a site of memory through a giant cadavre exquis (exquisite corpse)—a collaborative drawing approach first used by Surrealist artists, where players took turns to draw parts of the body and created bizarre art. Technique: Using various art materials of colour pencils, crayons, markers and highlighters the children and students drew spontaneously as in . I did not tell them what to draw, but the resulting imagery was both diverse in style and content but also connected, as it was born through their mutual conversations and experience that day.Evaluation

Successes:

The students learnt three lessons through their experience in the home. First, it nurtured their social skills and they gained immense joy in community service. Some students hardly interacted with small children and were unsure whether the children would like them. However, the shared activity of drawing together caused them to warm-up through small conversations. Although some children had a language barrier as they only spoke Mandarin, the act of drawing together became a wordless bond between them.

Secondly, they learnt to synthesize emotion with experience and create art. From the social materials collected, each student created art with a strong social reality either in realism or imagination. However, the experience differed from the urban plein-air as the interaction was with a younger group, therefore the content was more childlike. But both experiences with human interaction drew out strong emotional conviction in students to create powerful artwork.

Thirdly, they discovered a new way to create art. They took turns in joining, overlapping, starting and finishing one another’s drawing. Unlike painting which embodied completion and closure, drawing carried a sense of transparency and immediacy. This shared activity of drawing in collaborative space revealed their presence and movement, thoughts and conversations in unfinished thinking (Dexter, Citation2005) as shown in and . The giant collaborative drawing between the students and children itself served as a site of remembering, where the students’ outdoor experience was captured in that one drawing in all its spontaneity and subjectivity, as an unmediated record of life.

Difficulties and failings:

The class required extra planning in terms of logistics and administration. On top of arranging for transportation and getting students to sign consent forms for outdoor activities, there was also coordination between the orphans and the students’ clashing schedules. There was also extra cost in purchasing large papers and a variety of art materials. As the paper was gigantic, spanning 475.2 cm by 84.1 cm, we had trouble finding enough tables and space to fit all the tables to lay the long scroll of paper. Furthermore, due to limited time with the orphans, extra time had to be incorporated into completing the drawing post-visit. Although most students were engaging with the orphans, one student who suffered mild autism kept to himself. Despite being unable to engage in conversation, he drew the schoolbags and individualised name tags of the orphans on the shelf, which expressed his observations of the orphans’ lived reality.

7. Media space

Most foundation students I taught have little exposure to local or Southeast Asian arts. Consequently, many of the students’ role models are chiefly Hollywood directors. They looked up to American pop culture as their ideal with little understanding and appreciation of their own arts and culture. The art history class at foundation level covers Western art history from Renaissance to Modernism. The objective of the art gallery visit is to supplement the syllabus’s biases towards Western art history and introduce more local and regional art history to the students. Though the West exerts strong influence in the international art scene, the students’ art history education would be incomplete without an introduction to Southeast Asian art history. In order for students to develop their own artistic voice, they need an understanding of Southeast Asian identity through learning about the local and regional arts and culture. Other than gallery visits, cultural exposure can also be achieved through events like film festivals and workshops etc. However, due to the limitations of this paper, I will just examine cultural exposure in media spaces through the main entry point of an art gallery. Being in Johor, I was able to bring the students overseas to nearby Singapore to visit the National Gallery.

The first benefit of visiting the National Gallery is the exposure to a huge treasure of Southeast Asian masterpieces which are found in a variety of media. The arts and cultural scene in Johor is weak as there is only one small Johor Art Gallery (Galleri Seni) and a few private art galleries. The biggest art gallery in Malaysia is the National Art Gallery (Balai Seni Lukis Negara) located at the capital city Kuala Lumpur which holds about 2500 artworks from Malaysian and International artists. In comparison, the National Gallery of Singapore showcases more than 8,000 pieces from Singapore’s National Collection, making it one of the world’s largest and most invaluable public collections of Singapore and Southeast Asian modern art from the 19th century to the present day.

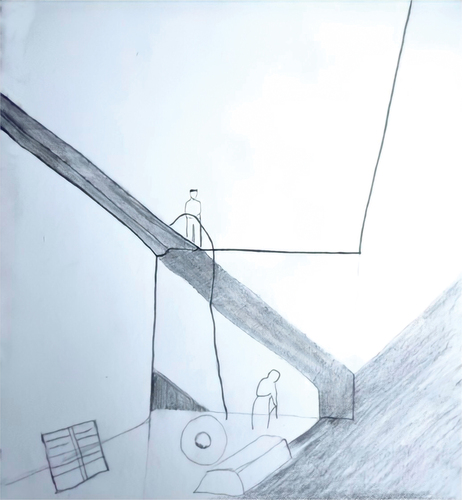

Standing before real art at the National Gallery, the students felt excited. During the visit, the students walked around the gallery, took photos, video, made sketches and eventually documented their experience into vlogs. In , Student P made a sketch of his favourite artwork which was a photograph. He studied its composition through the use of negative space. Later he painted the urban city in ‘The Bridge’ in , using the same techniques emphasizing negative space. Thus, he honed his understanding of design in negative space.

Student R—Gallery experience

It was exciting to visit Singapore’s National Gallery because we don’t have a proper gallery in Johor and Malaysia. It was a beautiful building with an amazing interior, where Southeast Asian and International art are exhibited side by side. I saw kindergarten kids led by their teachers queuing to visit the gallery. Singapore is so developed that even kindergarten kids are exposed to the arts. When I saw the collection of Nanyang style art by Singaporean Chinese artists, I reflected that though professionally curated and displayed in a world-class gallery, the spirit of the Chinese educated or ‘Nantah’ generation is gone, as Singapore is increasingly globalised and anglicised. In contrast, the Chinese-speaking community still exists in Malaysia, sustained by a network of clan associations and Chinese independent high schools; yet our arts and culture are not being protected and preserved. Malaysian Chinese are stuck in the past- isolated and marginalised, while Singapore is rapidly marching towards the future, perhaps too fast.

Evaluation

Success:

The trip to the gallery inspired the students through a wide exposure to a variety of media and increased their understanding and appreciation of Asian art. Most students have never been to a gallery, and were therefore only familiar with the traditional artmaking. The overseas class at National Gallery soaked the students in cultural experiences not just as a different physical site of memory but also the exposure to a variety of media in traditional and contemporary materials to create a new kind of sensorial experience of media as sites of memory.

Another benefit of the visit to the National Gallery was that it was overseas. As some students had never even left their home country, the overseas trip triggered new modes of learning in a foreign environment. The cultural exposure the students received went beyond the treasures in the art gallery to the physical immersion of the bustling city life in Singapore. Beyond exploring the Art Gallery, the students took the local train (MRT), went to the shopping malls and walked around the Downtown Core district of Singapore. The students were impressed by how clean the streets were and one of them said, ‘I can even lick the floor.’ Exploring the richness of the city, we also walked to the nearby Esplanade Theatre and enjoyed amazing life-jazz performances at the Singapore Jazz Festival. Thus, these exposure to specific culture and places countered the harmful effects of globalisation (Monk, Citation2016). The connection was not just with their regional cultural memory, but in collective memory as a group that grew stronger through this trip. The visit to Singapore also had a comparative value, by learning about Singapore’s culture and heritage through the arts, it gave them an understanding of its relationship with their own country in Malaysia.

Difficulties and Failings:

Above the extra administrative arrangements with the gallery and consent forms, the most challenging aspect was transport. Although Singapore was close to Johor, due the heavy jams at the causeway, a thirty minute ride could end up to be four hours. Sometimes, we had to take public transport into Singapore ourselves. Some students who had never left Malaysia, had to get a passport just for this outdoor class overseas. Also, the ticket price of US$20 and the cost of lunch in Singapore was expensive for Malaysian students, and many packed their own lunchbox. The teacher also had to be extra vigilant to oversee students’ safety from start to finish, especially at immigration checkpoints. For a larger group beyond nine students, I needed senior student leaders to aid me in supervision. Two students got separated from us due to delayed boarding in the crowded train but we later reunited. Although the students’ documented experience through photos, sketches and vlogs showed the gallery trip was eye-opening, the full impact of cultural exposure through art gallery visits cannot be fully measured within this short time or quantitatively.

Conclusion

Much can be done in the development of the Malaysian identity. If the future is in the hands of our next generation, the role of teachers in schools is pivotal in shaping that future. Art teachers are crucial in developing artistic thinking and a sense of identity in understanding regional art history and culture. Using sites of memory as an approach, outdoor learning can extend indoor classes and encourage heuristic learning and situated problem-solving in art. The final artwork is developed from the social material and internalised experience and not a superficial form, technique or style. Instead of focusing on the end product, students create materialised reflection in art, thus changing the definition of ‘artists as craftsmen’ to ‘artists as thinkers.’ Using the criteria of situated location and living cultural memory of the people, outdoor learning in art education develops the Malaysian identity.

Supplementary_Materials-_Rethinking_Art_Education_Paper_MeganW_25022022.pdf

Download PDF (72.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Asmawi, A., Faizuan, M., & Leong, S. (2019). The visual arts education crisis in Malaysia: placement of students into the arts curricular stream at the upper secondary level in Malaysian Secondary Schools. Journal of Visual Art and Design, 11(2), 79–92.

- Assmann, J. (2008). Communicative and cultural memory. In E. Herausgegeben von Astrid & N. Ansgar (Eds.), Media and Cultural Memory/Medien und kulturelle Erinnerung (pp. 85). Berlin & New York: Walter de Gruyter.

- Barret, E. (2010). Foucault’s ‘what is an author’: Towards a critical discourse of practice as research. In E. Barrett & Bolt (Eds.), Practice as research: Approaches to creative arts enquiry (pp. 135–145). Melbourne: I.B. Tauris.

- Borgdorff, H. (2011). The production of knowledge in artistic research. In M. Biggs & H. Karlsson (Eds.), The Routledge companion to research in the arts (pp. 44–63). London: Routledge.

- Carter, P. (2004). Material thinking: The theory and practice of creative research. Carlton, Vic: Melbourne University Publishing.

- Cicero, & Quintilian. (2008). Loci memoriae—Lieux de mémoire. In E. Herausgegeben von Astrid & N. Ansgar (Eds.), Media and Cultural Memory/Medien und kulturelle Erinnerung (pp. 19, 22). Berlin & New York: Walter de Gruyter.

- Clark, J. (1993). Open and closed discourses of modernity in art. In M. Chiu & B. Genocchio (Eds.), Contemporary art in Asia: A critical reader (pp. 27–45). London: The MIT Press.

- Department of Statistics Malaysia, (2010). Population Distribution and Basic Demographic Characteristic Report 2010. Author. https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/ctheme&menu_id=L0pheU43NWJwRWVSZklWdzQ4TlhUUT09&bul_id=MDMxdHZjWTk1SjFzTzNkRXYzcVZjdz09

- Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience. New York: Minton, Balch & Company.

- Dexter, E. (2005). Vitamin D: new perspectives in drawing (pp. 6–10). New York: Phaidon Press.

- Erll, A. (2008). Cultural memory studies: An introduction. In E. Herausgegeben von Astrid & N. Ansgar (Eds.), Media and Cultural Memory/Medien und kulturelle Erinnerung (pp. 4–10). Berlin & New York: Walter de Gruyter.

- Harth, D. (2008). The invention of cultural memory. In E. Herausgegeben von Astrid & N. Ansgar (Eds.), Media and Cultural Memory/Medien und kulturelle Erinnerung (pp. 85–96). Berlin & New York: Walter de Gruyter.

- Hashim, S. (1989). A balanced art education curriculum for the Secondary Schools of Malaysia. Ohio: Ohio University Press.

- Heidegger, M. (1996). Being and Time. (J. Strambaugh, ed.). Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Ihde, D. (1979). Technics and praxis. Dordrecht: Reidel.

- Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia, Bahagian Pembangunan Kurikulum Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia. (2003). Ministry of Education Malaysia, Department of curriculum development of Malaysian education. In Kurikulum standard sekolah menengah [secondary school standard curriculum] (pp. 1–56). Putrajaya: Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia.

- Khairuddin, H., & Yong, B. (2013). Introduction. In H. Khairuddin, B. Yong, & T.k. Sabapathy (Eds.), Reactions – new critical strategies: narratives in Malaysian art (Vol. 2). )Kuala Lumpur: RogueArt (pp. 14–22) .

- Marcel, J., & Mucchielli, L. (2008). Maurice Halbwachs’s mémoire collective. In E. Herausgegeben von Astrid & N. Ansgar (Eds.), Media and Cultural Memory/Medien und kulturelle Erinnerung (pp. 144–146). Berlin & New York: Walter de Gruyter.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of perception. (C. Smith, ed.). London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Monk, L. (2016). The art of memory and forgetting: Fine art and the resurrection of class memory in one London borough (pp. 33, 118). UK: University of Brighton.

- Pidayasa, R., & Suleiman, E. (1974). Towards a mystical reality: A documentation of jointly initiated experiences. In H. Khairuddin, B. Yong, & With T.k. Sabapathy (Eds.), Reactions – new critical strategies: narratives in Malaysian art (Vol. 2). Kuala Lumpur: RogueArt (pp. 31–54) .

- Sabapathy, T. K. (1996). Developing regionalist perspectives in southeast Asian art historiography. In M. Chiu & B. Genocchio (Eds.), Contemporary art in Asia: A critical reader (pp. 647–61). London: The MIT Press.

- Stokstad, M., & Cothren, M. W. (2011). Art history. (2ndVol. 2) Ed. New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.S.

- Vethamani, M. E. (2016). Visual Arts Education: A rethink on Creativity. New Straits Times. https://www.nst.com.my/news/2017/03/145985/visual-arts-education-rethink-creativity#:~:text=The%20Education%20Ministry%20has%20set%20up%20three%20Arts,arts%20while%20one%20school%20focuses%20only%20on%20music