ABSTRACT

Increasing attention to the relationships between transitions, power, spaces, and schooling, this article explores the disjuncture between seemingly liberal concepts in transition processes and hierarchical abuse of power. This ethnographic study sought to explore the perspectives of 16 children as they transitioned from one ‘early learning and childcare centre’, Lilybank, to four Scottish primary schools. Participant observations and face-to-face interviews were conducted in the formal educational settings and children’s homes. Overall, the study found that the perspectives of children can often be silenced by educational professionals or overshadowed and undermined by procedures. Children were expected to become acquiescent as they adjusted to coercive practices that limited children’s access to spaces in the school. The results suggest a need for a commitment to listening approaches, which may encourage educationalists to become respectful and responsive to children’s transition discourses and subsequent social realities.

Introduction

The opening quotation ‘Why are all the doors locked? I don’t feel free … I am not in charge of me anymore’ came from one five-year-old child as he transitioned from one early learning childcare (ELC) setting, Lilybank, to primary school. His parent could not answer his question. This article examines how power operates in transition processes as children moved from Lilybank to primary school. It draws from data produced from an ethnographic study, which illustrated that the perspectives of children and their families could often be silenced by educational professionals or overshadowed and undermined by systems. There are bound to be people who will primarily react to what is written here, for example, the findings portray that children were expected to become acquiescent as they adjusted to coercive practices used in the institutional regulated spaces. In an attempt at laying out some of the tensions that can exist as children move from ELC to primary school, the following section begins by providing a brief overview of what some children experience as they transition.

Prevailing definitions of educational transitions liken the transition process to moving from one place or phase of education to another (Harper Citation2016). An increasing number of scholars, as the literature shows, have not lost sight of the physical, social, and philosophical changes that young children have to make as they transition from one space to another (Perry, Dockett, & Petriwskyj, Citation2014). In a somewhat similar vein, Dunlop (Citation2014) highlights the intricate and multi-layered processes of transition, which are described as ‘vertical’ as children ‘move-up’ from the ELC setting to primary school and ‘horizontal’, which include changes in routine, for example, changes in location, such as moving rooms or relational as children experience changes with peers and practitioners (Holt Citation2019; Horgan et al. Citation2017). The present discussion is guided by transition research from Peters (Citation2017), who has raised a number of complex epistemological issues. Put simply, Peters argues that almost any child is at risk of making a poor or less productive transition if their individual characteristics are incompatible with the features of the environment they encounter. For example, pedagogically, there are often significant differences in the approach to teaching and learning between the ELC setting and primary school. In ELC, the pedagogical approach is more participatory as children learn through play; however, in primary school, a more authoritative discourse permeates a more transmissive pedagogy, with the practitioner focusing on discrete subjects. This perspective suggests that when the child enters the school, he or she is expected to fit into existing, homogenous, and relatively static programmes and systems, such as a grade-based curriculum and continuous assessment. Not surprisingly, children are likely to have complex feelings about new ways of learning. They may feel empowered by the intellectual challenges of the school institution and proud that they are older. At the same time, ‘their school lives are more circumscribed’ (Hillman Citation2006, 61; also Horgan et al. Citation2019). The school building is intended to edify large numbers of children, and therefore, tends to be physically bigger than the ELC setting; consequently, children report concerns about being scared or lost and not knowing where to go or worry about where the toilets are situated (Lee and Goh Citation2012). Inherent tensions exist as children frequently express that they miss being able to choose what to do, where to go, and as a consequence, lose their democratic identity (Author Citation2016). One feature of loss children experience, which dovetails with Horgan et al. (Citation2017) work, is that children often report a lack of authority over themselves.

Power and powerlessness

‘Adults everywhere assume primary roles in structuring and governing space and place, defining territorial boundaries and landmarks and transmitting historical and social (including proprietary) significances to places’ (Bowen Citation2015, 330). Reading Bowen (Citation2015) compels us to face that schools, as institutions, are spaces designed and organised by adults; they are encased in diverse political structures which operate through hierarchical means and are a context for the exercise of power. For example, schools are often imbued with hegemonic narratives that legitimise the oppression of children as children are expected to comply with the rules of the school. The adult-constructed/organised classroom reifies the children’s lack of control. Additionally, hegemonic narratives become tangible as children have no or little say in the pedagogy, curriculum, or administration of the school, and yet, they are the main occupants.

At the outset of the study, literature around power was not considered. When spending time with the study children, however, their ponderings regularly returned to the rules and regulations of the institutions. This led to an extension of research to consider the potency of power as a social phenomenon of transition and the spaces children occupy. Foucault’s (Citation1977) theory bequeaths diverse and rich interpretations of power, and his work is particularly helpful because of his influence on academic domains, particularly in the humanities and social sciences. He regularly linked his analysis of power to educational institutions. Stated plainly, Foucault challenged the idea that power is exercised by individuals, groups or both, by ways of intermittent acts of dominant control; instead, he viewed power as diffused and ubiquitous. Writing on power is demoted by extensive and ostensibly problematic differences over how it should be conceptualised or characterised. Power has often been considered as an intrinsic conflict between the user and the subject. Power for Foucault was not a thing to be possessed, nor was it essentially negative; Foucault defined power by three disparate ideas, the first being the sovereign of power, which includes conforming to the law or central authority, in this case, the school institution. The second, disciplinary power, which is a mechanism used to regulate the behaviour of individuals in the social body, such as conforming to the school timetable. Space, actions, and behaviour are also regulated as children are informed where to go and when and where to sit (Horgan et al. Citation2017). Here Foucault’s discussion on ‘docile bodies’ can be understood, where children are both able and submissive (Foucault Citation1977). Most notably, disciplinary power is carried through surveillance mechanisms. Probing this concept more deeply, Foucault insisted that ‘power is not discipline rather discipline is simply one way in which power can be exercised’ (Koupal Citation2012, 37). The third type of power, pastoral power, controls the conduct of individuals or groups of people through political organisation and actuarial classification. Indeed, as a conceptual lens, the importance of Foucault’s work lies with his emphasis on the undercurrents of power – who gets to participate and who gets excluded, by categorising, labelling, and isolating (Holt Citation2019) – being able to describe the various forms which power takes is instrumental in its manifestations, which comes in the form of action. Foucault’s work unearthed certain insights and revealed a new understanding of the role power plays in transition.

Methodology

The driving force behind the design of this study was to capture and honour children’s perspectives on the transition process. It was based on a fundamental belief that young children are rich, resourceful, and agentic social actors who are experts in their own lives. The methodological goal was, therefore, to represent children’s (and adults) views on transition. Ethnographic field research studies groups of people as they go about their everyday lives. Ethnography provided a key opportunity to understand the perspectives of children and adults in their familiar surroundings and gather research on the meanings children and adults brought to those settings. This study aimed to capture not only what children said but the interplay between participants and, importantly, what happened before and after. For example, the children voluntarily offered information. One day the children were queuing up to leave the classroom. A small group of children at the back of the queue, who would not, generally, have spoken at the front where the practitioner was leading the class, began discussing their ages. ‘I’m five now (showing five fingers), but she’s still four’, said one girl, pointing to her partner. The reaction of the four-year-old child suggested that being four may not be the desired age to be. This type of voluntary information provided indications of what was important to the children at that time. By being present in the various contexts enabled data to be gathered for the research questions asked. The research questions were:

What happens when children arrive at school?

How fluid are the power relations in transition?

Given that the focus of this study was young children’s transition, 16 children transitioning from Lilybank to 4 primary schools (Northfield, Westfield, Southfield, and Eastfield) were invited to participate. The children differed in age between 4.5 and 5.5 years and represented a mix of gender and ethnicity. The study group was, unintentionally, made up of eight boys and eight girls. There were 24 practitioners in Lilybank, who all indicated their willingness to be involved in the research. In the four primary schools, four primary practitioners contributed to the research and, tangentially, four head teachers participated in the reasearch. The practitioners who participated in the research did so informally, as the researcher captured everyday events in the settings and formally when they contributed to interviews.

Data was gathered from empirical methods such as participant observations and interviews. Participant observations took place in Lilybank and the participating schools. Most of the interviews took place in the children’s homes or a convenient environment for the family, such as a local cafeteria. Throughout the process, children were respected as active co-contributors of knowledge.

The participating institutions

The research was carried out in one local authority in Scotland in one ELC setting, Lilybank, and four schools. Two of the four schools were in areas described as being of disadvantage. After observing and gathering children’s views at Lilybank for one year, the fieldwork continued in the four schools over the course of the school year.

An introduction to Lilybank

Lilybank was an environment where various phases of development co-existed. The 57 children between the ages of 3 months and 5 years who attended daily could mingle together. This mingling together challenged traditional developmental beliefs of children following normal linear age and stages of development as it was considered children of all ages learn from each other. The children were not ‘taught’ by adults with goal-orientated plans; rather learning was child-led. Notably, children were trusted to take risks and to challenge themselves but were also challenged by highly skilled adults. Further Lilybank was a space where non-verbal and verbal children had the opportunity to participate in the ongoing transformation of the centre. Thus, Lilybank was a space that was organic and always being transformed. Children had access to both indoors and outdoors and there were no limits on where they could go and when. As well as the nursery site, the children also had access to a 26-acre wild site – the nature kindergarten and a beach school, which ran two days a week. Here it is not intended to indicate that this was the ideal environment for children, but to illustrate the significant changes in ideology, pedagogy, and space that children had to adapt to when they moved from Lilybank to primary school.

An introduction to the schools

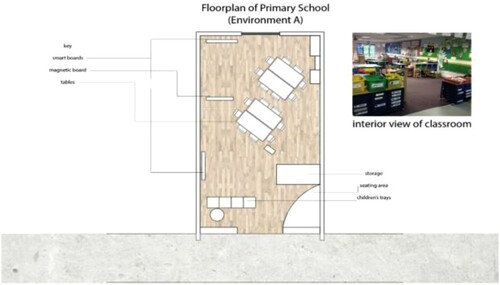

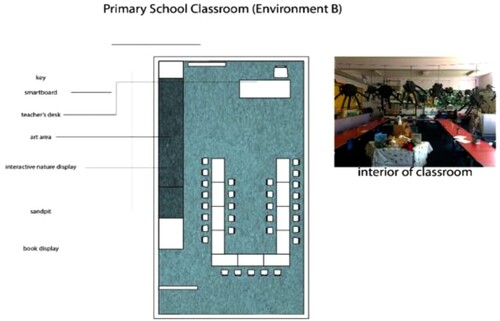

The four school research sites included two open-plan classrooms (e.g. ) and two closed-door classrooms (e.g. ). All participating schools were of an average size of 300–400 pupils and all had a nursery class attached. At the time of the research, the participating schools had a Pupil Support Assistant attached to the Primary One classroom.

The schools differed from Lilybank in respect of having more structured environments where children were under the constant gaze of adults, as they were organised in such a way that the practitioners had what Foucault (Citation1977) termed the ‘Panoptic’ gaze. The layout of the classroom allowed the adult to ‘see’ the children in all spaces. There were no opportunities for children to be alone. If they were permitted to leave the room, they had to be accompanied by an adult. Gallagher (Citation2008) named these ‘sites of control’ as spaces of ‘omnipresent surveillance’. In contrast to Lilybank, children were told where to sit, who they were to sit alongside, and what they were to do when they were situated. In this way, it could be argued that they were subordinate in their status to adults. For example, when the children left before the Easter break in one school, their tables and chairs were in small squares. When the children returned, the tables were all connected in a U shape. Adults constructed the environment to meet their plans. The children were slightly disorientated until they found their space.

All the schools had an outside space, which varied greatly according to each site. One had a small area paved with flagstones sectioned off from the main playground and another had two acres of land where children could run on the grass on dry days. The school institutions brought to mind Deleuze’s (Citation1999) concept of emergent ‘societies of control’ where both children (and adults) had little opportunity to ‘do what [they] want’. There were two open-plan classrooms, which presented as a kind of freedom. However, while the practitioners were freed from the enclosed space of a traditional classroom, they were always being observed as other practitioners, including the head practitioner, could walk back at any time to monitor practice.

Adopting an ethical approach

Research was conducted in accordance with the BERA ethical guidelines. Consent was also obtained from the Director of Children and Families, the head practitioners from the participating schools, the parents of the children, and the children themselves. Copies of information sheets and consent forms were created and sent to all participants; however, ethical approval is not enough; the researcher needs to reflect and be reflexive of their own ethical practice constantly. Subsequently, deliberate efforts were made throughout this research to live alongside children as active participants of the research processes. Researching children’s lives can raise a number of methodological concerns over informed consent, privacy and autonomy, and harm and exploitation. Information was shared with the children in a way they could assimilate and respond to. Children could also assent. This involved being attuned to the children, reading their body language, and informing children they could refuse to be involved. This was of the utmost importance. When practitioners or parents suggested that the children should respond to a question, and it looked as if the children were intrigued by something else, it was sensitively explained to the adult the children should not feel pressured to comply.

Some issues of accessing children privately arose. One of those was intergenerational inequalities – for example, not all practitioners shared the conception of the child’s right to privacy, confidentiality, and autonomy. The children’s homes too had their own micro-geographies with sets of familial power relations. During some children’s interviews, some parents expressed a desire to be present. This meant that, on certain occasions, some parents exerted control over the children’s responses. It was not unusual for parents to answer the question for their child. However, there was an occasion when one child, Philip, interrupted his parents, explaining they had answered wrongly. He proceeded to answer from his own knowledge of the experience. At times interviews were interrupted when children wandered in and out of the room, making requests to go out to play. Anonymity was preserved by the use of aliases for participants and the centres, as well as their exact geographical locations. The children chose their own names – interestingly, some children changed their alias more than once throughout the study.

Findings

After observing and gathering children’s views from the children at Lilybank for one year, the fieldwork continued in the four schools over the course of the school year. In some of the fieldwork vignettes, ‘I’ is sometimes used, this refers to the researcher. The findings have been framed using Gore’s (Citation1995) analytics of power (e.g. surveillance and normalisation). Gore (Citation1995) shared Foucault’s view that power is ‘ubiquitous’, ‘ever-changing’, and ‘benign’.

Surveillance

Surveillance is defined by Gore (Citation1995) as ‘supervising, closely observing, watching, and threatening to watch or expecting to be watched’ (Gore Citation1995, 169). On entering the school, it was obvious that surveillance as a mechanism was a socialised and embedded phenomenon of school life; and that surveillance resulted from the complex iterations between individuals:

Mixed emotions engulfed me as I pressed the school buzzer. A voice at the other end enquired who I was. I said my name and the door buzzed and I was allowed entry. The school administrator was the first person I saw. She did not smile or greet me warmly. Instead she explained that the children would soon be going into the hall. I was instructed to go there. The administrator leaned over an open window and pointed to the hall. I walked towards the hall, looking over my shoulder for guidance that I was heading in the right direction, but the administrator had disappeared back into her ‘enclosure’. Despite her disappearance I continued to feel I was under constant scrutiny. (Field notes, August)

The see-through ‘enclosure’ that the administrator occupied gave her the illusion of authority (O’Farrell Citation2005). From the administrators’ physical location, she appeared to be omniscient and visible, but out of reach. Her aloofness was evocative of the centrally-planned prisons of the nineteenth century. The most famous example of these is Bentham’s Panopticon, a design in which a central guard tower is encircled by many storeys of prison cells so that prisoners are forced to modulate their behaviour, despite not being able to see inside the guard tower. Foucault argues this is ‘the major effect of the Panopticon: to induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power’ (Citation1977, 201). In Surveiller et Punir (Citation1975) translated as Discipline and Punish in 1977, Foucault explored Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon. Panopticon refers to obtaining power over the minds of prisoners and encouraging them to police themselves.

Surveillance was frequently present in both interviews and observations. For example, one of the schools featured a small, rectangular playground, hard-landscaped in poured concrete, and bordered by a chain-link fence. The fence outlined the specific zones where children could spend their time and limited their space. There were no resources for the children to play with. This, again, evoked an architectural device used in prisons, that of the ‘Yard’Footnote1. This playground merely served as a plateau on which children could escape the tacit surveillance of the school’s interior, to the more implicit surveillance of the school’s exterior:

I was invited out into the playground today. I found myself to be very popular. Many children were keen to hold my hand and chat with me. There were other adults in the playground, pupil support assistants (known as PSAs). They did not engage with the children unless it was to give an order, i.e., stay on the paving stones, no pushing, no chasing etc. One supervisor did not vocalise her request, she simply looked at the child, pointed to a piece of litter and then indicated to the bin. The offending child was then expected to pick up the litter (dropped by him?) and put the dropped litter into the bin … A girl I had never met before (perhaps from the other Primary One class?) came up to me, laid her head on my thigh and said ‘I am going to be good today’. (Field notes, August-Westfield School)

The children were aware of being under surveillance. The playground supervisor’s non-verbal indication of inappropriate behaviour confirmed that the playing children were never hidden from the watchful eye of the surveying adult and an overall expectation that children would be obstreperous. This indicated to the children that the ‘all seeing’ supervisors had the power to punish any misbehaviour. The persuasiveness of this mechanism was apparent when the (unknown) child came up to me, another adult, and felt the need to tell me that she intended to behave, despite not being questioned or prompted, as if she did not want to disappoint me. This incident is deeply problematic as it calls into question the school’s role.

Lynch and Lodge (Citation2002) argue ‘If the State requires young people to stay in school then it is imperative that their education is an enabling and enriching experience (Lynch and Lodge Citation2002, 2). School may not have been an enabling or enriching experience for this child. For example, why was not she playing and socialising with other children? Was she so worried about the consequences of her behaviour that she could not focus on the things that intrigued and stimulated her? The girl’s anxiety at being observed was notable in her actions and expression. This supervision was not solely the province of the playground supervisor and children started monitoring and regulating the behaviour of their peers. Foucault’s (Citation1977) notion of governmentality can be useful here – the ‘conduct of conduct’ where children manage themselves and are managed (Rose Citation1999).

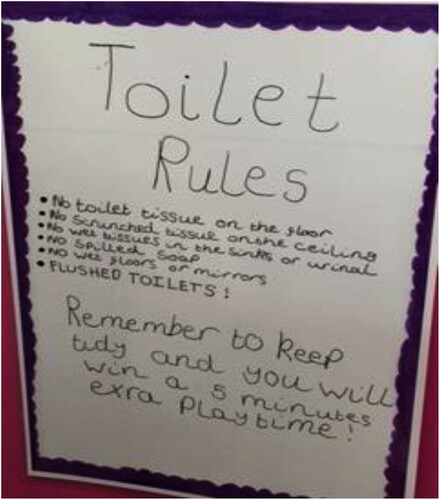

The notion of Foucault’s ‘governmentality’ could also be understood through the highly visible signage throughout the building, written by children for children, and outlining officially unsanctioned behaviour.

The Toilet Rules () were posted in the girls’ toilet. It could be contended that the author may not be known to all the children in the school – anyone could have written the sign, resulting in children not knowing who was watching and when. It must also be considered it was unlikely that ‘5 min extra playtime!’ would ever be granted due to the logistics of allowing some children five minutes extra.

Surveillance techniques were operated in a rigid fashion, but children and parents’ views varied on whether this was a good or bad thing or simply – just the way it is. One parent commented:

We know [he] feels constrained and controlled at school so as soon as he is home we let him be, no rushing around, no unnecessary demands (he still has to operate as part of a family and be considerate to us and we to him) but as much as we can we keep it all calm and gentle. (Parent interview, October)

Here we are given an impression of how the state exercises the power of individuals and populations, as the parent ‘almost’ accepts what is happening to her child needs to be somewhat tolerated.

Some children were under the illusion that certain practitioners could see everything continuously and had concerns about how non-compliance (for example, with writing) might affect their future transition:

‘And … and … em because, because if you don’t do it [writing] neatly, you don’t get to go into a different class like … like … like if you do that 10 or 20 times you have to stay in class up to next year (said with emphasis) for the rest of the year.’ explained William.

‘Did the teacher say that to you?’ I asked.

‘We just knew … ’ replied William. (Child interview with William, five years, April)

William ‘just knew’ the ‘all seeing’ practitioner would know if he did not do neat writing. Through his somewhat fear-induced hesitation, William argued that the thought of being under surveillance had a normalising effect – he wanted to do neat writing in order to progress to the next classroom with his peers. William’s example reminds us that having to follow the practitioners’ directions is strongly associated with children’s adjustment to school.

Another interpretation of William’s example is that by being compliant, following instructions and school conventions, children think they will make the necessary adjustments that enable progression and future transition. William’s example, by highlighting the practitioner’s perceived omniscience, also alludes to the Panopticon. To William, the positive aspect of self-regulation and surveillance in schools is that he can prevent future problems with the transition. It must be considered, then, that administrative or controlling surveillance, even when it instilled fear and even when some people may find it uncomfortable, is a part of school life that both children and parents expect and learn to accept.

Surveillance at school differed from surveillance at Lilybank. At school, the children were almost always under the watchful eye of the adult. As illustrated, the classrooms were either open-plan or enclosed. The exception to being constantly surveyed was when the children needed to use the toilet – although permission had to be granted first and the practitioner was aware of how long a child was away. If any child was away too long, the Pupil Support Assistant was sent to find out why he was keeping them. In one school, an adult always accompanied the child to the toilet. Furthermore, children were aware of what spaces were available to them and what spaces were not: We’re not allowed in there [staff room] … just [name of teacher] and other [teachers]. (Child interview, August – Northfield school)

However, in Lilybank, surveillance was less constant, children were free to move throughout the building and garden, there were also areas where children could go to be alone or with peers. Whilst the adults knew where the children were and they were not under constant scrutiny.

In Lilybank, power was transferred to the children, although the children may have had an awareness of occasionally being watched, which resulted in them unconsciously regulating themselves. This self-regulation, according to Foucault (Citation1977), would come from the uncertainty of knowing when they were being watched. As a result, power, argued Foucault, becomes internalised.

However, another interpretation of the approach at Lilybank could come from Tisdall (Citation2019), who would argue that when children are considered dialogic partners/social actors, they co-construct with adults, and power is shared. The approach at Lilybank can be connected to research that argues power relationships between children and children and between children and adults can be both transgressive and transformative. Practitioners at Lilybank argued that by viewing children as transformative, the learning space could be provocative and could alter children’s perceptions that they were ‘being watched’. Practitioners at Lilybank argued that they approached children as trusted contributors to the context. In contrast, at school, children’s opportunity to self-regulate increased as they learned the rules (Bernstein Citation1996) and how they were expected to behave. Some parents argued that the children needed to conform to the rules of the school:

She has been learning the … I know it sounds bad, but to follow a regime … you know follow instructions, like stay in the line … . (Parental interview, November – Southfield School)

And I guess in practice there does need to be some order (laughs). I think these things need to be adhered to. It is part of their education as well. (Parental interview, June – Westfield School)

The need for conformity highlights the interesting phenomenon that power, when expressed by the practitioner, might rapidly decrease over time, concurrent with a child’s ability to learn the norms of the institution. Foucault (Citation1977) connects surveillance mechanisms to self-regulation, and there was no doubt in the minds of respondents that increased self-regulation leads to greater child autonomy and less adult control. However, Lilybank’s approach suggests that increased child autonomy and self-regulation were related to less adult control. Ironically both contradictory perspectives end up in the same place – less adult control. This finding provided insight regarding the tensions between thinking and practice in the different settings of the study and recognise how the same curriculum could be employed to justify opposing pedagogy (child freedom v child control).

Foucault (Citation1977) argues the surveyor does not hold power – but that power is exercised simultaneously and then becomes internalised. Foucault’s conception of power differs from the often-synonymous idea of authority. The children at Lilybank were holders of power in that they exercised self-regulation, relative freedom, and self-awareness. The children in school settings have to wait to become holders of power, and adults, to different extents, seek to control this process.

However, it is undoubtedly the adult that holds the authority in all contexts, and far from being ‘fluid’, the dynamic of power is rationed. The holder of authority, and thus the distributor of power in this context, is undoubtedly the adult. Whilst the child’s power was indeed in flux, this dynamic was entirely controlled by the adult. Philip (5 years) explained how children could be excluded from other children and the class for specific periods of time, known as ‘time out’, from Philip’s description, the notion of exclusion functioned spatially (Foucault Citation1977), for example, children were removed from the classroom, or excluded to a space in the playground where they were segregated from other children to a zone of exclusion within the institution.

Above, notions of the Panopticon have been utilised to explain how surveillance operated in the different settings of the study. However, it should be noted that there is a difference between Panopticon effects in relation to surveillance and those that breed normalisation. Normalisation refers to the way that social actors are expected to conform and how specific ways of being are internalised. Foucault (Citation1977) argued that norms and expectations conveyed are hidden in everyday discourse. He differentiates between the visual Panopticon and the allegorical Panopticon (hidden values that have a normalising impact). The next section considers how children operated enforced self-regulation within discourse, for example, telling each other how they should sit and write. It argues that the practitioner is not only an omniscience authority figure as a result of their ability to operate mechanisms of visual surveillance but also due to their ability to influence the messages in children’s discourse (ways of being, thinking, and talking).

Normalisation

the primary object of normalisation is a group, a population – usually the entire population. The aim is to create the power of the norm, to, via the penalty of the norm, create ‘standardisation’, ‘homogeneity’ … A population is normalised to the extent it is brought to behave according to the relevant internally differentiated norm. (Young Citation2014, 201)

In this view, normalisation is to make everyone the same. However, this sameness can be either positive or negative. Sameness in terms of legal rights is the ideal environment of the modern democracy; however, enforced sameness, disregarding personal identity or individual motives, forms the basis of many a dystopian novel. Linked to this idea, Gore adds that normalisation includes ‘ … invoking, requiring, and setting or conforming to a standard – defining the normal’ (Gore Citation1995, 171).

Lynch and Lodge argue that schooling is ‘normalised as a social practice’ (Citation2002, 2). In what sense, then, does the school normalise? From observations, it happens in four ways:

Normalisation seeks to ensure that all children in the school behave in a similar way to other children, for example, ‘Primary 1b can you show me good sitting, good listening, and good looking’ (Field notes, September, – Eastfield School).

Institutional procedures, such as testing and assessing the children, perpetuates awareness among them of being examined. Consequently, this normalisation affects how they view themselves and others.

Children are normalised within the procedures of the school. For example, they comply with the school rhythms and the imposed spatio-temporal constraints. The children then become part of the social order and are subsequently programmable and teachable.

If the child does not behave in ‘normal’ ways, then the behaviour is viewed as ‘abnormal’ and must then become subject to some form of deterrent to correct it. This normalises both the individual and also acts as a warning or deterrent to normalise the population as a whole.

Therefore, in order to navigate the complexity of transitions, most children become ‘normalised’. However, should the child think radically in different terms to that of another child, he is likely to receive a deterrent to prevent him from doing so again:

… a child crawled under the table to get to his seat at the other side. He is told on by another child. The teacher responded by saying: ‘You are the one who tells me he has sore knees … your knees will be sore if you don’t look after them.’ (Field notes, August – Westfield School)

The normal behaviour expected from the child was to walk around the table to take his seat. The child who observed his peer’s behaviour thought it was unacceptable and told the practitioner. The ‘telling’ by the other child is what Foucault (Citation1977) meant by the ‘society of surveillance’ – when everyone within a society understands the normative ways to behave within it. The ‘telling’ child judged his peer’s behaviour in terms of the standards that had been constructed in the classroom. The practitioner provoked thought in the offending child by noting the negative consequences of his action. This chastisement was intended to normalise the child’s future behaviour.

Foucault’s (Citation1977) argument is not that normalisation was unnecessary in all circumstances – he argued that normalisation is, at times, an essential part of the institution. Foucault’s concern was that normalisation killed creativity. In the above example, it could be argued that the child was creatively using a strategy to get into his seat. However, it is unlikely that he will repeat this performance, otherwise, he will knowingly do something he should not do. Normalisation or ‘normalising judgement’ was significant to how power operated. Foucault showed that people might be ‘oppressed and dominated through standard ways of talking that served to normalise certain practices and marginalise others’ (Feinberg and Soltis Citation2004, 71). The school practitioners often transmitted normative expectations onto the children by interjecting their own beliefs into the children’s discourse:

I want to see good numbers today. (Field notes, August – Eastfield School)

When the practitioner said this, no child questioned what good numbers were. Some writers would argue there was an uncritical acceptance by the children that the practitioner was the holder of knowledge (e.g., Nassaji and Wells Citation2000). To the children, the practitioner understood good numbers – she projected a standard way to do numbers. At this early point in the children’s transition, they were forced to accept the practitioner’s perspective or expect public ridicule.

While in flux, the practitioner in this context withholds and maintains power through knowledge and authority. One device of maintaining power through knowledge is the denial of interpretation – the assertion that there are ‘good numbers’. This dynamic could be seen as contradictory to the core aims of the school system, whereby creativity and interpretation should be fostered in lieu of adherence to authority.

Gallagher (Citation2004) argues that the normalising instructions given by practitioner add to the process of successful teaching. The practitioners in all four schools used normalising techniques to bring about internal controls in the children, which corresponded with external practices. In one instance, I discovered that the practitioner would introduce an instruction, such as ‘Good listeners look at the person … ’, and then this instruction would be turned into a question, asking the children ‘What do good listeners do?’ This would be repeated in the classroom until the children could chant the answer with little consideration.

A great weight was given to children using a quiet voice in the classroom. Manifested in practice was that a quiet voice was preferred to a loud one. Commands to quieten children were repeatedly heard:

Zip it, lock it, and put it in your pocket. (Field notes, September – Eastfield School)

We have playground voices and classroom voices. (Field notes, September – Northfield School)

Normalising, then, applies to quite specific aspects of a child’s physiognomy, down to their writing styles and volume of voice.

In both the surveillance examples and the normalisation examples, power is exercised to bring the children into being, to change them, to make them different from what they were. In this way, the practitioners in this study appeared unschooled in Gallagher’s (Citation2004) view that pedagogical entry lives in the act of practitioners understanding the child. Practitioners, perhaps, unwittingly perpetuate techniques that are an obstacle to learning. So, whilst Foucault (Citation1977) argues that there are legitimate occasions for normalisation mechanisms to operate, what he does not argue is that other alternatives may be possible, such as dialogic approaches. From the observations above, the use of normalisation techniques contradicts much of what is beneficial to a child’s learning and fosters a culture of conformity and the creation of homogenous children.

Conclusion

Unique life journeys involve differences, and from their individual experiences, children construct elaborate knowledge. This study began with the core claim that children’s verbal and non-verbal dialogue on transition could influence understandings of transition. What emerged from the study was that the views of children could (and do) add nuance to our understanding of how power impacts their transition experience. Children’s accounts of discipline strategies used by the schools were insightful.

In answer to the question: What happens when children arrive at school? It was discovered that children are treated as neutral, fixed entities to be institutionalised in the broadest sense. From this standpoint, children’s individual capacities are under-explored in this industrialised system. The beginning of school life is marked by stratagems and tactics that aim to establish and sustain the classification and ordering of children – this is to the detriment of the individual child. In answer to the question – How fluid are the power relations in transition? The data suggested that power relations could have been more flexible. Mechanisms such as surveillance and normalisation, were regularly carried out by professionals and selected to ensure children complied and practitioners could teach effectively. The examples that have been presented illustrated that authoritarian strategies for ordering and controlling children in school spaces continue to be conventional and that order is imposed through fear, which can be physical but mainly psychological. Overall, the children accepted the disciplinary mechanisms without argument. It was discovered that practitioners exercised power over children, regulating the time, occupation of space, choice of clothing, meal times, and even methods of social interaction. In short, the children learned to fit into linear systems and became their guards, self-fulfilling representations of the institution.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks the anonymous readers for their invaluable peer review comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The outside exercise area.

References

- Author. 2016. “‘Rules, Rules, Rules and We’re not Allowed to Skip’: An Exploratory Study into Young Children’s Transitions.” PhD Thesis. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh. Accessed March 18, 2021. https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/22942.

- Bernstein, B. 1996. Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity. London: Taylor and Francis.

- Bowen, Z. 2015. “Play on the Mother-Ground: Children’s Games in Rural Odisha.” South Asian History and Culture 6 (3): 330–347.

- Deleuze, G. 1999. Foucault. London: Continuum.

- Dunlop, A.-W. 2014. “Thinking About Transitions: One Framework or Many? Populating the Theoretical Model Over Time.” In Transitions to School: International Research, Policy and Practice, edited by B. Perry, S. Dockett, and A. Petriwskyj, 31–46. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Feinberg, W., and J. F. Soltis. 2004. School and Society: Thinking About Educational Series. New York: Teachers College Columbia University.

- Foucault, M. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Pantheon.

- Gallagher, M. 2004. “Producing the Schooled Subject: Techniques of Power in a Primary School.” Doctoral Thesis: Geography. The University of Edinburgh: Edinburgh.cv b.

- Gore, J. M. 1995. “On the Continuity of Power Relations in Pedagogy.” International Studies in Sociology of Education 5 (2): 165–188.

- Harper, L. J. 2016. “Supporting Young Children’s Transitions to School: Recommendations for Families.” Early Childhood Education Journal 44 (6): 653–659.

- Hillman, M. 2006. “Children’s Rights and Adults’ Wrongs.” Children's Geographies 4 (1): 61–67.

- Holt, L. 2019. “The Power of Young People’s Friendships in Schools: Geographies of Emersion.” Presented at the 6th International Conference on the Geographies of Children, Youth and Families. May 22-24, Brazil 2019.

- Horgan, D., C. Forde, S. Martin, and A. Parkes. 2017. “‘Children’s Participation Moving from the Performative to the Social’.” Children’s Geographies 15 (3): 1–15.

- Koupal, R. 2012. “The Destiny of Curriculum Theory in Light of Postmodern Philosophy: A Case Study on Foucauldian Doctrines.” International Journal of Applied Linguistic Studies 1 (2): 36–41.

- Lee, S., and G. Goh. 2012. “Action Research to Address the Transition from Kindergarten to Primary School: Children’s Authentic Learning, Construction Play, and Pretend Play.” Early Childhood Research & Practice 14 (1): 1–21.

- Lynch, K., and A. Lodge. 2002. Equality and Power in Schools: Redistribution, Recognition and Representation. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Nassaji, H., and G. Wells. 2000. “What's the Use of 'triadic Dialogue'?: An Investigation of Teacher-Student Interaction.” Applied Linguistics 21 (3): 376–406.

- O’Farrell, C. 2005. Michel Foucault. London: Sage.

- Perry, B., S. Dockett, and Petriskyj A. (eds.). 2014. Transitions to School-International Research Policy and Practice. London: Springer.

- Peters, S. 2014. “Chasms, Bridges and Borderlands: A Transitions Research ‘Across the Border’ from Early Childhood Education to School in New Zealand.” In Transitions to School: International Research, Policy and Practice, edited by B. Perry, S. Dockett, and A. Petriwskyj, 105–116. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Punir. 1975. Surveiller et punir de Michel Foucault 1975-1979 is a book published by Artieres Phillippe in France, published by Pu Caen. I am not sure if this helps?

- Rose, N. 1999. “The Gaze of the Psychologist.” In Governing the Soul: The Shaping of the Private Self, edited by N. Rose, vii–xxvi. London: Free Association Press.

- Tisdall, K. 2019. “Learning from Co-Production: Participation Activities with an Impact?” Presented at the 6th International Conference on the Geographies of Children. Youth and Families. May, 22–24. Brazil 2019.

- Young, J. 2014. The Death of God and the Meaning of Life. Oxon: Routledge.