ABSTRACT

Universal Design (UD) is promoted internationally for the design of public playgrounds that support outdoor play, social participation, and inclusion. Despite this international recognition of UD, there is a lack of research evidence concerning the applicability of UD for playground design. Instead, municipalities need to rely on best practice guidelines to inform the design of public playgrounds for inclusion. Internationally, numerous grey literature guidelines have been produced for designing public playgrounds for inclusion, resulting in a lack of consensus on core principles for applying UD. Thus, this scoping review study aimed to synthesise findings from a review of international grey literature guidelines to strengthen the knowledgebase for designing public playgrounds for inclusion. Three themes were identified that characterise core considerations for good design: (1) design approaches, (2) design principles and (3) design recommendations. Although UD is recognised as having potential to support the design of public playgrounds, inconsistent design approaches, principles, and recommendations, were communicated within these guideline documents. Still, the core concept of inclusion underpinned all guideline documents and a tailored application of UD dominated. Consequently, to fully realise the design of public playgrounds for inclusion, UD may need to be tailored for play; however, further research is required.

Introduction

Play is a universal and important process that is known to confer extensive benefits for children’s health and wellbeing. This point is made in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UN Citation1989), Article 31, the right to play, and further reinforced by play researchers (e.g. Ginsburg Citation2007; Moore and Lynch Citation2018). Public playgrounds, the focus of this paper, are outdoor play environments intended for community use, which in most countries differentiates them from school playgrounds (Burke Citation2013). Public playgrounds are key geographies for families and children (Refshauge, Stigsdotter, and Cosco Citation2012) as they enable gathering, socialising, resting and importantly, participating in play (Lynch et al. Citation2020).

Yet, many children are not afforded equal opportunities to benefit from participating in a play in public playgrounds due to incongruencies between children’s play needs and formal play environments typically designed, planned and managed by adults (Moore, Lynch, and Boyle Citation2020; Stafford Citation2017). Researchers have identified that public playgrounds can inadvertently perpetuate social and spatial marginalisation and exclusion, particularly for children with disabilities and their families, because of inadequate access, unsatisfactory play options, poor play value and insufficient opportunities for social interaction (e.g. Burke Citation2013; Jeanes and Magee Citation2012; Moore, Lynch, and Boyle Citation2020; Stafford Citation2017; Woolley Citation2012). Hence, there is a fundamental need to strengthen inclusive playground provision in the public realm.

Although much of the research on inclusive playground provision has taken place within schools (e.g. Bundy et al. Citation2008, Citation2011; Doak Citation2020; Kretzmann, Shih, and Kasari Citation2015; Sterman et al. Citation2020; Yantzi, Young, and Mckeever Citation2010), research is evolving on inclusive playground provision in the public realm. For example, researchers have explored user perspectives, investigated the perspectives of municipality representatives, reviewed policy documents, analysed guidelines, studied research evidence, developed tools to assess playground design, proposed frameworks for creating inclusive playgrounds, evaluated playground design, investigated the frequency and duration of children playing on a universally designed playground compared to children playing on an inclusive playground and designed inclusive playgrounds (Supplementary Table 1). No studies to date have evaluated outcomes of inclusive playgrounds from a Universal Design (UD) and play value perspective, as fundamental aspects of effective design (Brown et al. Citation2021; Moore, Lynch, and Boyle Citation2020; Parker and Al-Maiyah Citation2022).

Evidently, the design of public playgrounds has been implicated as a contributory factor in enabling inclusion (Brown et al. Citation2021; Fernelius and Christensen Citation2017; Lynch et al. Citation2020; Moore and Lynch Citation2015; Moore, Lynch, and Boyle Citation2020). Furthermore, addressing play and participation through inclusive playground design has emerged as deserving of attention (Lynch et al. Citation2020; Moore and Lynch Citation2015; Moore, Boyle, and Lynch Citation2022; Moore, Lynch, and Boyle Citation2020, Citation2022). While Universal Design (UD) is commonly cited across the literature, there remains evidence of inconsistent understanding and application of the term (Moore, Boyle, and Lynch Citation2022). For example, Bianchin and Heylighen (Citation2018) identified that ‘UD’, ‘inclusive design’ or ‘design for all’, are used internationally, but vary depending on the continent or region. The new European standard EN 17210:2021 Accessibility and usability of the built environment – Functional requirements (NSAI Standards Citation2021), elaborated upon these three terms and identified that further terms to the above such as ‘accessible design’, ‘barrier-free design’ and ‘transgenerational design’ are often used interchangeably. However, from this plethora of terminology, UD has emerged as a design approach that appears to be linked most closely with inclusion (Lynch et al. Citation2020; Moore and Lynch Citation2015; Moore, Boyle, and Lynch Citation2022; Moore, Lynch, and Boyle Citation2020, Citation2022).

The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) defines UD as ‘the design of products, environments, programmes and services to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialised design’ (UN Citation2006, 4). Indeed, the UNCRPD (UN Citation2006) endorses UD as the most efficient way of ensuring that everyone can access and use public services and facilities. Furthermore, General Comment No. 17 (GC17) (CRC Citation2013), an authoritative statement on Article 31, identified UD as the way forward in public play provision. Still, Moore, Lynch, and Boyle (Citation2020) recently identified a lack of evidence as yet concerning the applicability of UD for playground design. In addition, researchers found that despite having seven principles and eight goals to enable its application, UD is poorly understood as a concept, and requires further clarity and specificity as it pertains to playground design and inclusion in outdoor play (Moore, Boyle, and Lynch Citation2022; Moore, Lynch, and Boyle Citation2022).

Despite these limitations to UD specifically, there is an abundance of documentation to support ‘inclusive design’ in its general sense in the form of guidelines. Design guidelines play an important role in translating the principles of an approach such as UD to guide the creation of inclusive solutions that meet the needs of children and families. They differ from published academic literature insofar as they are often more easily accessed by diverse stakeholders and aim to increase understanding of relevant design principles and their application. Numerous grey literature guidelines have been produced internationally for the design and provision of playgrounds for inclusion, and come from several sources, including non-governmental and not-for-profit organisations, industrial organisations (e.g. commercial manufacturers of playground equipment) and from implications of formal and informal research studies (Casey Citation2017; Lynch, Moore, and Prellwitz Citation2018, Citation2019). Despite their proliferation, researchers have found that few formal guidelines clearly articulate what a universally designed playground is or should be (Burke Citation2013; Fernelius and Christensen Citation2017; Moore and Lynch Citation2015). Also, inconsistent design principles, as well as solutions, are resulting in a lack of clarity (Moore, Lynch, and Boyle Citation2020); thus, it is difficult to establish good practice for the design and provision of playgrounds for inclusion, as few efforts have been made to synergise the information (Olsen Citation2015).

While some effort has been made in recent years to examine the evidence for best practice for designing playgrounds for inclusion (Brown et al. Citation2021; Fernelius and Christensen Citation2017; Moore and Lynch Citation2015; Moore, Lynch, and Boyle Citation2020), and to assemble information from guideline documents (Kim, Kim, and Maeng Citation2018; Lynch et al. Citation2019), to date, there has not yet been a systematic analysis of grey literature guideline documents to synthesise the design approaches, design principles and design recommendations for the design of universally designed public playgrounds, that enhance play value for inclusion and participation. Thus, to move beyond the exclusionary practices and determine what designing public playgrounds for inclusion is, or should be, the purpose of this study was to explore international grey literature guidelines for the design of public playgrounds for inclusion, and examine the design approaches, design principles and design recommendations within these guidelines. Moreover, the review aimed to determine the applicability of UD and play value, to bring together an improved understanding and knowledgebase for those who plan, design and/or provide public playgrounds for inclusion.

Methods

This paper describes scoping review search methods that were developed and applied to conduct a review of grey literature pertinent to guidelines for the design of public playgrounds for inclusion. The most common definition of grey literature (the ‘Luxembourg definition’) defines it as ‘that which is produced on all levels of government, academics, business and industry in print and electronic formats, but which is not controlled by commercial publishers, i.e., where publishing is not the primary activity of the producing body’ (Schöpfel et al. Citation2005). The Internet is often used as a platform for publishing grey literature by a wide range of organisations (Benzies et al. Citation2006) and tends to be widely accessible as subscriptions are not required, as may be the case with the peer-reviewed scholarly literature (Godin et al. Citation2015).

Although scoping reviews typically comprise a review of published and grey literature on a given topic (Arksey and O'Malley Citation2005; Levac, Colquhoun, and O'Brien Citation2010; Peterson et al. Citation2017), for this study, a scoping review of grey literature exclusively was selected for four main reasons. First, a scoping review of published peer-reviewed research literature on the design and provision of playgrounds for inclusion has already been conducted (Moore, Lynch, and Boyle Citation2020) and found no studies that reported on outcomes for the application of UD to enhance inclusion; second, the design and provision of public playgrounds for inclusion is therefore informed primarily by expert opinion and guidelines on good practice rather than being evidence-informed from formal peer-reviewed studies; third, these guidelines warrant investigation, as inconsistent design approaches, principles and solutions are resulting in a lack of clarity on what a public playground design for inclusion is or should be; and fourth, guidelines for designing playgrounds for inclusion are typically released by government and non-government organisations and not published in academic journals. Thus, a review of grey literature would provide a more complete review of all available evidence (Mahood, Van Eerd, and Irvin Citation2014).

Consequently, a scoping review of grey literature was conducted using the five-stage approach originally described by Arksey and O'Malley (Citation2005) and later refined by the Joanna Briggs Institute (Peters et al. Citation2015) and other researchers (Levac, Colquhoun, and O'Brien Citation2010).

Stage 1: Identifying the research question(s)

This scoping review focused on answering the following research questions: (1) what are the characteristics of the grey literature guidelines for designing public playgrounds for inclusion (e.g. year published, source organisation, by whom they were developed, intended audience, goal/objectives of guideline)? and (2) what are the design approaches, design principles and design recommendations articulated within the guidelines for designing public playgrounds for inclusion?

Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies

To identify guideline documents for designing public playgrounds for inclusion, an electronic search of Google search engines was completed in November 2019 and updated in June 2020. Search terms included combinations of the following, in recognition of the various terms used to describe UD: (playground OR playspace OR ‘play space’) AND (guide* OR ‘design guide*’) AND (design* OR access* OR inclus* OR ‘Universal Design’). The search generated 106 potentially eligible records.

Stage 3: Study selection

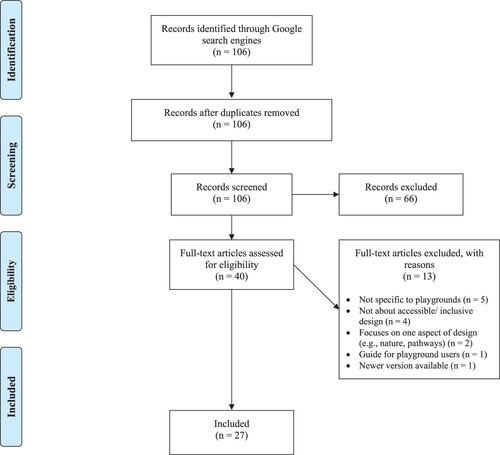

As the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) recommends using a study flow diagram to describe the screening and study selection process (Moher et al. Citation2009), this process was applied to the grey literature search methods (). The title, year of publication, source organisation and web links of guideline documents identified were entered into an Excel sheet. For a guideline document to be included, strict inclusion criteria needed to be met ().

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram of study selection process (Moher et al. Citation2009).

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Of the 106 screened records, twenty-seven guideline documents that focused on designing public playgrounds for inclusion, met the inclusion criteria ().

Stage 4: Charting the data

Following a full review of each included guideline document, data were extracted pertaining to guideline characteristics (source organisation, year published, by whom they were developed, intended audience, goal/objectives of guideline) and the design approaches, design principles and design recommendations within these guidelines. Only data that were relevant to the design of public playgrounds for inclusion were extracted (i.e. guidelines pertaining to specific play items were not extracted), consistent with the a priori objectives of the review.

Stage 5: Collating, summarising and reporting the results

Using the data extraction chart, data were collated and summarised. Data analysis was conducted by the lead author of this scoping review and independently reviewed by the remaining authors. Data were analysed using a UD and play value framework.

Results

Evidence characteristics

Evidence characteristics were identified from the twenty-seven guideline documents that met the inclusion criteria, and data extracted pertaining to research question one. These are listed in and, where referenced within this paper, highlighted with the relevant number.

Table 2. Design approaches, principles and recommendations.

Of these, twenty-four guideline documents were published between 2003 and 2020; a further three guideline documents did not list their date of publication (). Ten of the guideline documents originated from the United Kingdom (UK), six from the United States of America (USA), five from Australia, two from Canada and one each from Ireland, Denmark, China and India.

The guideline documents ranged from 7-pages to 156-pages, with the average number of pages being 51.6-pages, and originated from several sources, including non-profit organisations (n = 13), industrial organisations (n = 6), government organisations (n = 4), industrial-education cooperation (n = 2), government advisory organisation (n = 1) and from education (n = 1) (). All guideline documents provided guidance for designing public playgrounds for inclusion and the intended audiences for the guideline documents were those that plan, design and/or provide public playgrounds (design professionals, councils/municipalities and community groups).

Furthermore, as shown in , thirteen guideline documents referred explicitly to UD; however, only four of these utilised the seven principles of UD as their design principles (6, 11, 18 and 19). Thus, a degree of inconsistency and confusion was evident among the included guideline documents. Yet, the core concept of inclusion underpinned all twenty-seven guideline documents, irrespective of what design approach or design principles were adopted. Moreover, specific design recommendations relating to designing public playgrounds for inclusion were evident in all guideline documents. These will be discussed under the summary of main findings.

Summary of main findings

Three themes were identified from the data extracted and pertain to research question two. The first theme describes the design approaches that were used to describe designing for inclusion. Theme two addresses the design principles articulated to describe the concept of designing for inclusion. The third theme highlights the design recommendations for designing public playgrounds for inclusion.

Theme 1: Design approaches

Although all twenty-seven guideline documents provided guidance for designing public playgrounds for inclusion, UD was not always articulated as a design approach. As shown in , accessible design, inclusive design and UD were used to describe non-discriminatory planning and design processes.

Of the twenty-seven guideline documents, thirteen documents referred to UD as a design approach for inclusive public playground design () and used UD interchangeably with accessible design and inclusive design; yet all thirteen documents defined what was meant by UD. Specifically, six documents drew upon definitions proposed by Ronald Mace (6, 18 and 22) and international Centres of Excellence in UD (9, 11 and 16). Moreover, two documents referred to rights-based documents when defining what was meant by UD; one guideline (8) drew upon GC17 (CRC Citation2013), while another guideline (19) referred to the UNCRPD (UN Citation2006). Furthermore, five documents did not necessarily cite their source, but defined UD differently as the design of: ‘buildings, products, and environments that are usable and effective for everyone, not just people with disabilities, without the need for adaptation or specialised design’ (13), ‘products, environments, programmes, and services to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialised design’ (15), ‘environments, services and products that are useable and accessible for people of any age and ability’ (21), ‘an approach to designing products, services, and environments to be usable by as many people as possible regardless of their ability’ (24) and ‘environments that are usable by more people, to the greatest extent possible’ (25).

Overall, while differences were apparent across the definitions, when discussed in relation to play environments, the aims of UD, were articulated as follows: (i) moving beyond minimum accessibility, to ensure equal emphasis is placed on maximising varied play opportunities and supporting social integration (11, 16, 19, 22 and 24); (ii) creating a space where everyone is welcomed (9, 15 and 25); (iii) providing the same or equivalent experiences and activities (these may have to be provided in different ways for different people) (9 and 15); and (iv) designing a space with accessible, inclusive routeing and infrastructure and access to relevant ground- and elevated-level activities (19).

Yet, for the remaining fourteen guideline documents that did not refer explicitly to the UD design approach, ten guideline documents utilised inclusive design in combination with accessible design (). Also, two documents used inclusive design exclusively; like UD, inclusive design was defined as a space that ‘offers and encourages play experiences for people of all abilities … ’ (4), and ‘beginning from a perspective of ‘strengths,’ … create [a] play space that is designed with everyone in mind and that challenges and supports children with a wide range of abilities’ (14). In this way, inclusive design mirrored UD, in that it was about providing for all. Moreover, two further documents used accessible design exclusively, with a greater focus on children with disabilities; accessible design was defined as ‘the criteria by which accessibility should be judged therefore is whether the disabled child was able to play at the playground, rather than whether they were able to access a particular item of equipment, or complete a particular activity …' (1) and ‘encouraging disabled and able-bodied children to play together’ (26).

To summarise, most guideline documents (n = 23) utilised a combination of design approaches, or indeed, used the terms interchangeably for designing public playgrounds for inclusion. While UD was identified as a design approach with specific meanings and aims, when used, it was always used in combination with other approaches. It is not clear why this was the case; however, as established in the literature review, UD, inclusive design and accessible design are often used interchangeably. Nevertheless, given that UD was defined as a specific design approach with specific aims, inclusive design held similar meanings to UD, whereas accessible design differed because it was about designing for disability. In any case, it could be argued that while single design approaches were adopted in some instances, a combination of approaches appears to be the most favoured approach for designing public playgrounds for inclusion among the included guideline documents. Indeed, apart from two documents focusing on accessible design, there was an overall recognition among the guideline documents of the need to move beyond minimum accessibility, and thus, a combination of approaches was adopted in most instances.

Theme 2: Design principles

The principles and/or goals of UD were not always articulated as design principles for designing public playgrounds for inclusion among the twenty-seven guideline documents. However, given the establishment of UD as the design approach recommended by the GC17 (CRC Citation2013) and the UNCRPD (UN Citation2006), and the evidence of it being the most advanced in terms of principles and goals, the seven principles of UD were used as an analytical tool to map the design principles. As shown in , the number of design principles, listed in the guideline documents, ranged from nil to ten principles, with the average number being 4.4 principles.

As noted earlier, thirteen guideline documents referred explicitly to UD. However, only seven guideline documents referred to the commonly accepted seven principles of UD; four of these guideline documents utilised the seven principles of UD as their design principles (6, 11, 18 and 19), while three guideline documents tailored the principles of UD for playgrounds (22, 24 and 25) (). For the remaining six guideline documents that referred explicitly to UD, one document identified seven principles (9), one guideline document listed three principles (16), one guideline document named three essential factors (21) and three documents did not list design principles (8, 13 and 15) ().

For the remaining fourteen guideline documents that did not refer explicitly to UD but instead referred to accessible design and/or inclusive design, numerous design principles were apparent. Specifically, three guideline documents listed ten design principles (3, 5 and 26), one guideline document identified seven design principles (7), two guideline documents listed six design principles (4, 10), one guideline document utilised five design principles (20), one guideline document named three design principles (23) and six guideline documents that referred to accessible design and/or inclusive design did not list any design principles (1, 2, 12, 14, 17 and 27) ().

To summarise, a combined eighteen of the twenty-seven guideline documents articulated design principles for designing public playgrounds for inclusion. Thirteen guideline documents referred explicitly to UD; however, only seven guideline documents referred to the commonly accepted UD principles (Connell et al. Citation1997). Still, only four of these guideline documents utilised the seven principles of UD as their design principles (6, 11, 18 and 19), while the remaining three documents employed them in different ways to make them more specific to playgrounds (22, 24 and 25). A further eleven guideline documents articulated their own design principles suggesting that UD principles either require further tailoring to make them more specific to playgrounds or are not deemed applicable. Yet, as evident above, the principles vary significantly across the guideline documents, which further adds to the confusion when attempting to determine what an inclusive playground is or should be.

Still, play, play value and children’s participation in the physical and social environments for play were significant. Moreover, when the seven principles of UD were applied as an analytical tool to map the design principles that did not use the seven UD principles, but instead either tailored the seven UD principles, or articulated their own design principles, the three most common UD principles evident were equitable use, flexibility in use and tolerance for error. Moreover, regardless of what design principles were adopted, twenty-two guideline documents endorsed the need for co-design when designing public playgrounds for inclusion. Co-design varied from engaging and involving children (1, 2 and 5), adults (e.g. parents) (14 and 19), children and adults (3, 4, 6, 7, 13 and 20), children, adults and the community (e.g. disability organisations; residents) (9, 11, 15, 16, 18, 21 and 22), as well as the community (12, 23, 26 and 27).

Theme 3: Design recommendations

Among the twenty-seven guideline documents, numerous design recommendations for designing public playgrounds (play spaces) for inclusion were apparent. Design recommendations were categorised into recommendations as they pertained to: (1) play value, (2) location, layout and accessibility and (3) support features. While the length of the paper precludes a full discussion of each of the design recommendations (e.g. the design process and including users), attention will be drawn to the main messages.

Play value

Play value is used to describe the value of an environment, object or piece of equipment for play. For play value, design recommendations pertained to the provision of inclusive play spaces and play items that were inclusive of persons of all backgrounds, ages and abilities to participate in varied types of play. Play value recommendations were categorised into nine issues, outlined below.

For engaging people of all ages and abilities, twenty-five documents provided recommendations (). Indeed, the need to provide meaningful opportunities for inclusive, intergenerational play was recommended. Specific recommendations included the need to: provide play equipment to allow family groups to play together; select play activities so that people of all ages can engage in play; avoid segregating individuals by ability by ensuring that the most fun activities are also the most accessible; and include adult-centred play spaces where seniors can socialise through shared activities (e.g. exercise equipment, etc.). While there was acknowledgement of the need to provide meaningful opportunities for inclusive, intergenerational play, twenty documents were primarily oriented towards play for children (1, 2, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 24, 25 26 and 27).

For selecting play space equipment, twenty-four documents provided recommendations (). Specifically, there was recognition among the documents that having a one hundred per cent accessible play space is not possible; however, the overall aim is to ensure that all children have access to the social experience of play and equality of play experience. Even so, specific recommendations included the need to: select equipment that complies with country specific standards; ensure some provision for people with differing abilities (e.g. equipment with UD features); select ‘non-prescriptive’ equipment that can be used flexibly by children of different ages and interests; use colour carefully to avoid over stimulation or confusion; and maintain equipment overtime to reduce the inherent risks.

For accessing play space equipment, twenty documents provided recommendations (). Recommendations included the need to: ensure access to high-interest, fun areas of the play space; ensure clear ground space so that a child who is using a wheelchair can access the play equipment and features by sitting at/under them; place equipment so that it can be reached by children at different sitting and standing heights and abilities; and provide play equipment that accommodates variations in gross and fine motor control.

For grouping play space equipment, fourteen documents provided recommendations (). Specifically, there was recognition that good play spaces avoid segregating children based on age or ability and are laid out so that equipment and features can be used by a wide range of children and allow for different patterns of usage. Specific recommendations included the need to: consider play equipment fall zones, movement zones, areas to ‘wait your turn’ and space for multiple users when grouping equipment; locate similar types of equipment in the same area; and incorporate equipment or features with graduated levels of challenge, that is, options for children to try different challenge levels.

For incorporating challenge and risk, twenty-one documents provided recommendations, particularly as it related to play challenge in the playground (). Recommendations included the need to: include a range of stimulating and imaginative activities in the play space with several overlapping scales of difficulty; and balance risk and benefits in a strategic way, using a policy framework (detailing the approach to risk and safety), to help resist unjustified negligence claims.

For play types then, recommendations were largely categorised into affordances for four play types: physical, sensory, social and cognitive/dramatic/imaginative play. For physical play, twenty-four documents provided recommendations (). Physical play affordances included features, equipment or spaces that afforded the following actions: spinning; sliding; rocking; swinging; climbing; crawling and strengthening; balancing; jumping and bouncing; and walking, running and rolling. Moreover, tunnels and cableways/ziplines were recommended. Also, the provision of accessible play items that provide for varied play preferences and play styles, as well as graduated challenge was recommended.

For sensory play, twenty-three documents provided recommendations (). Sensory play affordances included features, equipment or spaces that afforded the following sensory experiences: tactile/touch (smooth, soft, hard, rough, grainy and uneven); auditory/sound; visual experiences/sight;as well as smell and taste. Also, natural elements (water, earth, fire and wind), natural features (e.g. trees, willow structures and plants that create loose parts), planting (non-thorny and non-toxic) and cosy/quiet areas, were recommended. Moreover, the need to carefully consider the location of sensory stimuli to avoid creating a chaotic sensory environment of haphazard stimuli as well as ensure that sensory stimuli were accessible to all and afford play value was recommended.

Also, for social play, twenty-five documents provided recommendations to foster social play opportunities (). These included the need to include features, equipment or spaces that: encourage cooperative play (e.g. equipment that requires reciprocal interaction to operate it); and encourage interaction with others while playing (e.g. spaces to congregate).

Finally, for cognitive/dramatic/imaginative play, twenty-three documents provided recommendations to foster cognitive/dramatic/imaginative play opportunities (). These included the need to: include a mixture of dramatic and realistic play equipment and features (e.g. stage/platform, playhouse and play items that resemble other items); utilise play spaces under/on the play structure; incorporate loose parts (e.g. construction materials); and ensure that cognitive/dramatic/imaginative play opportunities are accessible.

Location, layout and accessibility

For location, layout and accessibility, design recommendations primarily pertained to maximising accessibility and inclusion in the built environment and were categorised into nine main issues: location; parking and other ways to arrive; entryway and orientation; surfacing; pathways; wayfinding; orientation in and around the space; perimeter boundary; and supervision and surveillance. While the length of the paper precludes a full discussion, the design recommendations for location, layout and accessibility as they relate to each of these nine issues can be found in Supplementary Materials.

Support features

Support features largely pertained to supportive infrastructure and amenities to maximise inclusion in the built environment within and surrounding the play space. For support features, design recommendations were categorised into twelve main issues: seating; tables/picnic tables; spaces to gather and socialise; shade and sheltered areas; toilets/changing facilities; litter bins; drinking fountains; lighting; storage facilities; service/assistance animals; signage; web page/social media. While the length of the paper precludes a full discussion, the design recommendations for support features as they relate to each of these twelve issues can be found in Supplementary Materials.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore international grey literature guidelines for designing public playgrounds for inclusion. Moreover, this review aimed to determine the applicability of UD and play value in designing public playgrounds for inclusion. While some effort has been made in recent years to examine the evidence for best practice for designing public playgrounds for inclusion (Brown et al. Citation2021; Fernelius and Christensen Citation2017; Moore and Lynch Citation2015; Moore, Lynch, and Boyle Citation2020), and to synergise information from guideline documents (Kim, Kim, and Maeng Citation2018; Lynch et al. Citation2019), for the first time, this systematic analysis of grey literature guideline documents provides a broad understanding of how design approaches, design principles and design recommendations for designing public playgrounds for inclusion are conceptualised and discussed in guidance documents in many international contexts. Indeed, findings from this review show that grey literature guideline documents are an important source of knowledge for designing for inclusion, and in the absence of evidence for implementing UD, potentially provide a vision for inclusive playground design (Moore, Lynch, and Boyle Citation2022).

Despite differences, the core concept of inclusion underpinned all twenty-seven guideline documents in this review. Findings from this review highlighted the importance of autonomy of inclusion, which deconstructs assumptions on ‘providing for all’. Certainly, there was acknowledgement that no one size fits all and public playground users are not a homogenous group; inclusion, however requires that provision be made for different ages, abilities, play preferences and comfort preferences, for example. Nevertheless, while there was acknowledgement of the need to provide meaningful opportunities for inclusive, intergenerational play among most guideline documents, they were primarily oriented towards the play of children. Nevertheless, given that achieving inclusion by providing for different abilities is a defining feature of UD, we must carefully consider how it can underpin the design of public playgrounds, echoing findings from a recent review of the academic literature (Moore, Lynch, and Boyle Citation2020). This would contribute to discussions on changing social expectations of the concept of who can ‘play’ and where, given the value of public playgrounds in terms of providing shared community spaces.

In this review of guideline documents, multiple design approaches and numerous design principles were evident, suggesting an inconsistency and confusion between approaches, principles and application. Indeed, the analysis revealed that design approaches were often named without context/source/citation. While UD and inclusive design were the most common approaches articulated among the reviewed guideline documents, two used accessible design exclusively as a design approach. Despite the assertion that accessible design is synonymous with UD, it has recently been asserted that accessibility factors alone are inadequate for addressing play participation in inclusive playgrounds (Moore, Lynch, and Boyle Citation2020, Citation2022; Moore, Boyle, and Lynch Citation2022). As noted in the findings, design recommendations identified the need to consider accessibility, play value, progressive levels of challenge and adopt a balanced approach to risk. These extend beyond accessibility and aim toward the provision of public playgrounds that offer inclusive and varied play experiences and facilities. Therefore, conflating accessible design with UD risks overlooking key inclusion measures such as play value, and a collective approach to its eventual use. Indeed, the concept of play value is now identified as central to public playground design among international researchers (e.g. Parker and Al-Maiyah Citation2022; Woolley and Lowe Citation2013).

It has been concluded elsewhere that the application of UD is problematic when considering the need to design for play (Casey Citation2017; Lynch, Moore, and Prellwitz Citation2018; Moore, Lynch, and Boyle Citation2020). Despite the challenges, UD is endorsed by GC17 (CRC 2013) and the UNCRPD (UN 2006), and is also promoted by international researchers for providing conceptual guidance for designing playgrounds that are inclusive (Burke Citation2013; Casey Citation2017; Moore, Lynch, and Boyle Citation2020, Citation2022; Moore, Boyle, and Lynch Citation2022; Prellwitz and Skär Citation2007, Citation2016; Stanton-Chapman et al. Citation2020; Woolley Citation2012). Consequently, to fully realise the design of public playgrounds for inclusion, UD may need to be tailored for play (UD for play [UDP]) (Moore, Boyle, and Lynch Citation2022) in the same way it has been tailored to ensure equity of teaching and learning in inclusive education (UD for Instruction/UDI) (Burgstahler Citation2009). A similar approach could be adopted to consolidate the importance and future application of UD for Play (UDP) – this proposal suggests that UD could/should be integrated with play value in such a way that it can be applied to the overall design of inclusive public playgrounds as well as of specific playground components, terrain and facilities.

Methodological considerations

Despite efforts to conduct this scoping review of grey literature systematically and rigorously, there are some limitations. To maintain the focus of this scoping review, several criteria were put in place that excluded potentially relevant studies. Specifically, the use of Google search engines as the primary source for locating grey literature, available free of charge, may have omitted a greater diversity of evidence. Also, guidelines selected for inclusion focus on public playgrounds that are intended for community use, and do not specifically consider school playgrounds; this may have overlooked potentially relevant evidence, as school playgrounds are becoming more available for public use, outside of school hours, in international contexts. Although these guidelines originated in four continents (North America, Australasia, Europe and Asia), no specific cultural or spiritual differences were identified, which needs further exploration in future studies. Finally, this scoping review of grey literature was limited to guideline documents published in the English language; therefore, evidence published in other languages was omitted.

Importantly, this scoping review excluded guideline documents for specific contexts that do not translate to other contexts (e.g. each fit within specific national country-specific contexts in relation to standards and laws). While the included guideline documents applied to designing public playgrounds for inclusion in general, it must be acknowledged that country specific standards/laws are mandatory, and therefore, guideline documents need to be used in combination with the relevant country specific standards/laws to avoid potentially dangerous/illegal practices. Nevertheless, if country specific standards/laws do not mention UD then there might be a perception that there is no obligation to attempt or consider UD for public playground design. However, given the establishment of UD as the design approach recommended by the GC17 (CRC Citation2013) and the UNCRPD (UN Citation2006), this scoping review revealed that guideline documents play an important role in offering guidance for designing public playgrounds for inclusion. Thus, the overlap between what is mandatory (country specific standards/laws) and what is optional (guidelines) is worth exploring in future research.

Conclusion

The review of grey literature evidence reveals some important findings that would not have been apparent without a comprehensive analysis of grey literature. The synthesis of evidence from this review brings together an improved understanding for those that plan, design and provide public playgrounds for inclusion. Although UD is recognised to have the potential to support the design of public playgrounds, inconsistent design approaches, principles and recommendations, were communicated among the included guideline documents. Still, the core concept of inclusion underpinned all guideline documents, and a tailored application of UD dominated. Consequently, to fully realise the design of public playgrounds for inclusion, UD may need to be tailored for play (UD for play [UDP]) (Moore, Boyle, and Lynch Citation2022); however, further research is required.

Therefore, future research needs to establish best practice guideline documents for designing public playgrounds for inclusion as well as explore the perspectives of ‘users’ and ‘creators’ (i.e. ‘end users’ and those with technical expertise) of public playgrounds, to overcome the inequalities faced by diverse public playground patrons and strengthen socio-spatial inclusion. While involving users is not yet common practice in built environment design (Heylighen, Van der Linden, and Van Steenwinkel Citation2017), this review highlighted that the success of public playground design is dependent on honest and respectful co-design and co-creation with creators, from project inception to outcome, otherwise, design can/does still occur with limited contextual understanding of the lived experience.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any human or animal participants.

CCHG_2073197_Supplementarymaterial

Download MS Word (53.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Acknowledgements

Special thanks are due to the reviewers for their important feedback during the review process. The first author’s PhD research is funded by an Irish Research Council award; the second and third authors supervise this PhD research.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alison, John, and Rob Wheway. 2004. Can Play Will Play: Disabled Children and Access to Outdoor Playgrounds. London: National Playing Fields Association. http://www.childrensplayadvisoryservice.org.uk/pdf_files/Publications/can_play_will_play-CPASwebsite.pdf

- Arksey, Hilary, and Lisa O'Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Benzies, Karen M, Shahirose Premji, K. Alix Hayden, and Karen Serrett. 2006. “State-of-the-Evidence Reviews: Advantages and Challenges of Including Grey Literature.” Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 3 (2): 55–61. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6787.2006.00051.x.

- Bianchin, Matteo, and Ann Heylighen. 2018. “Just Design.” Design Studies 54: 1–22. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2017.10.001.

- Brown, Denver, Timothy Ross, Jennifer Leo, Ron Buliung, Celina H Shirazipour, Amy E Latimer-Cheung, and Kelly P Arbour-Nicitopoulos. 2021. “A Scoping Review of Evidence-informed Recommendations for Designing Inclusive Playgrounds.” Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences 2: 1–13. doi:10.3389/fresc.2021.664595.

- Bundy, Anita C, Tim Luckett, Geraldine A Naughton, Paul J Tranter, Shirley R Wyver, Jo Ragen, Emma Singleton, and Greta Spies. 2008. “Playful Interaction: Occupational Therapy for All Children on the School Playground.” The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 62 (5): 522–527. doi:10.5014/ajot.62.5.522.

- Bundy, Anita C, Geraldine Naughton, Paul Tranter, Shirley Wyver, Louise Baur, Wendy Schiller, Adrian Bauman, et al. 2011. “The Sydney Playground Project: Popping the Bubblewrap - Unleashing the Power of Play: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial of a Primary School Playground-based Intervention Aiming to Increase Children’s Physical Activity and Social Skills.” BMC Public Health 11 (680): 1–9. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-680.

- Burgstahler, Sheryl. 2009. “Universal Design of Instruction (UDI): Definition, Principles, Guidelines, and Examples.” https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED506547.pdf

- Burke, Jenene. 2013. “Just for the Fun of It: Making Playgrounds Accessible to All Children.” World Leisure Journal 55 (1): 83–95. doi:10.1080/04419057.2012.759144.

- CABE Space. 2008. “Public Space Lessons: Designing and Planning for Play.” Accessed 16 June 2020. https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/asset/document/designing-and-planning-for-play.pdf

- Casey, Theresa. 2017. “Outdoor Play and Learning in the Landscape of Children’s Rights.” In The SAGE Handbook of Outdoor Play and Learning, edited by Tim Waller, Eva Arlemalm-Hagser, Ellen Beate Hansen Sandseter, Libby Lee-Hammond, Kristi Lekies, and Shirley Wyver, 362–377. London: SAGE Publications.

- Casey, Theresa, and Harry Harbottle. 2018. Free to Play: A Guide to Creating Accessible and Inclusive Public Play Spaces. Scotland: Inspiring Scotland, Play Scotland and the Nancy Ovens Trust. https://www.inspiringscotland.org.uk/publication/free-play-guide-creating-accessible-inclusive-public-play-spaces/

- Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation. n.d. “Toolkit for Building an Inclusive Community Playground.” Accessed 22 June 2020. http://s3.amazonaws.com/reeve-assets-production/Quality-of-Life-Toolkit-2-1.pdf

- Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC). 2013. General Comment No. 17 on the Right of the Child to Rest, Leisure, Play, Recreational Activities, Cultural Life and the Arts. Geneva: United Nations. https://www.refworld.org/docid/51ef9bcc4.html

- Connell, Bettye Rose, Mike Jones, Ron Mace, Jim Mueller, Abir Mullick, Elaine Ostroff, Jon Sanford, Ed Steinfeld, Molly Story, and Gregg Vanderheidedn. 1997. “The Principles of Universal Design, Version 2.0.” https://projects.ncsu.edu/ncsu/design/cud/about_ud/udprinciplestext.htm

- DESSA. 2007. “Play for All: Providing Play Facilities for Disabled Children.” Accessed 16 June 2020. https://www.dessa.ie/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Play-for-All.pdf

- Doak, Lauran. 2020. “Realising the ‘Right to Play’ in the Special School Playground.” International Journal of Play 9 (4): 414–438. doi:10.1080/21594937.2020.1843805.

- Dunn, Karen, Michele Moore, and Pippa Murray. 2003. Developing Accessible Play Space: A Good Practice Guide. London: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. http://www.carltd.com/sites/carwebsite/files/Accessible%20Play%20Space.pdf

- Fernelius, Courtney L., and Keith M. Christensen. 2017. “Systematic Review of Evidence-based Practices for Inclusive Playground Design.” Children, Youth and Environments 27 (3): 78–102. doi:10.7721/chilyoutenvi.27.3.0078.

- Ginsburg, Kenneth R. 2007. “The Importance of Play in Promoting Healthy Child Development and Maintaining Strong Parent-Child Bonds.” Pediatrics 119: 182–191. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-2697.

- Godin, Katelyn, Jackie Stapleton, Sharon I Kirkpatrick, Rhona M Hanning, and Scott T Leatherdale. 2015. “Applying Systematic Review Search Methods to the Grey Literature: A Case Study Examining Guidelines for School-based Breakfast Programs in Canada.” Systematic Reviews 4 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1186/s13643-015-0125-0.

- Government of South Australia. n.d. “Inclusive Play: Guidelines for Accessible Playspaces.” Accessed 22 June 2020. https://dhs.sa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/85023/Inclusive-Play-GuidelinesV2.pdf

- HAGS. 2018. “Inclusive Play: Design Guide.” Accessed 29 June 2020. https://issuu.com/hags-uk/docs/hags_-_inclusive_play_-_design_guid

- HAGS. 2019. “Inclusive Play: Guide to Creating Inclusive Playgrounds.” Accessed 29 June 2020. https://www.hags.com/en-us/designing-inclusive-playgrounds/download-links-inclusive-playground-pack

- Heylighen, Ann, Valerie Van der Linden, and Iris Van Steenwinkel. 2017. “Ten Questions Concerning Inclusive Design of the Built Environment.” Building and Environment 114: 507–517. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2016.12.008.

- Inclusive Play, KIDS, and Amy Wagenfeld. 2019. “PiPA: Plan Inclusive Play Areas.” Accessed 16 June 2020. https://www.inclusiveplay.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/PiPA-Interactive-Form.pdf

- Jeanes, Ruth, and Jonathan Magee. 2012. “‘Can we Play on the Swings and Roundabouts?’: Creating Inclusive Play Spaces for Disabled Young People and Their Families.” Leisure Studies 31 (2): 193–210. doi:10.1080/02614367.2011.589864.

- Kim, Yun-Geum, Hana Kim, and Soo-hyun Maeng. 2018. “Characteristics of Inclusive Playground Guidelines.” Journal of the Korean Institute of Landscape Architecture 46 (6): 75–84. doi:10.9715/KILA.2018.46.6.075.

- Kompan Play Institute. 2020. “Play for All: Universal Design for Inclusive Playgrounds.” Accessed 25 June 2020. https://www.kompan.ie/play-for-all-universal-designs-for-inclusive-playgrounds

- Kretzmann, M., W. Shih, and C. Kasari. 2015. “Improving Peer Engagement of Children with Autism on the School Playground: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Behavior Therapy 46 (1): 20–28. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2014.03.006.

- Landscape Structures. 2018. “Inclusive Playspace Design: Planning Guide.” Accessed 16 June 2020. http://viewer.zmags.com/publication/c878a7ae#/c878a7ae/1

- Levac, Danielle, Heather Colquhoun, and Kelly K O'Brien. 2010. “Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology.” Implementation Science 5 (1): 69. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

- Liedtke, Helena. 2016. “Creating Inclusive Play and Community Spaces: An Out-of-the-Box Approach to Social and Emotional Inclusion.” Accessed 16 June 2020. https://www.communityinclusion.org/inclusiveplayspaces/inclusive_playspaces.pdf

- Luce, Brian. 2015. “Inclusive Design Manual: A Guide to Creating Play Spaces Which Welcome Children of All Abilities.” Accessed 16 June 2020. https://playgroundideas.org/dashboard/

- Lynch, Helen, Alice Moore, Claire Edwards, and Linda Horgan. 2019. Community Parks and Playgrounds: Intergenerational Participation Through Universal Design. Dublin: National Disability Authority. http://nda.ie/Publications/Others/Research-Promotion-Scheme/Community-Parks-and-Playgrounds-Intergenerational-Participation-through-Universal-Design1.pdf

- Lynch, Helen, Alice Moore, Claire Edwards, and Linda Horgan. 2020. “Advancing Play Participation for All: The Challenge of Addressing Play Diversity and Inclusion in Community Parks and Playgrounds.” British Journal of Occupational Therapy 83 (2): 107–117. doi:10.1177/0308022619881936.

- Lynch, Helen, Alice Moore, and Maria Prellwitz. 2018. “From Policy to Play Provision: Universal Design and the Challenges of Inclusive Play.” Children, Youth and Environments 28 (2): 12–34. doi:10.7721/chilyoutenvi.28.2.0012.

- Mahood, Quenby, Dwayne Van Eerd, and Emma Irvin. 2014. “Searching for Grey Literature for Systematic Reviews: Challenges and Benefits.” Research Synthesis Methods 5 (3): 221–234. doi:10.1002/jrsm.1106.

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, and Douglas G Altman. 2009. “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement.” BMJ 339 (4): b2535. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2535.

- Moore, Alice, Bryan Boyle, and Helen Lynch. 2022. “Designing for Inclusion in Public Playgrounds: A Scoping Review of Definitions, and Utilization of Universal Design.” Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 1–13. doi:10.1080/17483107.2021.2022788.

- Moore, Alice, and Helen Lynch. 2015. “Accessibility and Usability of Playground Environments for Children Under 12: A Scoping Review.” Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy 22 (5): 331–344. doi:10.3109/11038128.2015.1049549.

- Moore, Alice, and Helen Lynch. 2018. “Understanding a Child’s Conceptualisation of Well-Being Through an Exploration of Happiness: The Centrality of Play, People and Place.” Journal of Occupational Science 25 (1): 124–141. doi:10.1080/14427591.2017.1377105.

- Moore, Alice, Helen Lynch, and Bryan Boyle. 2020. “Can Universal Design Support Outdoor Play, Social Participation, and Inclusion in Public Playgrounds? A Scoping Review.” Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–22. doi:10.1080/09638288.2020.1858353.

- Moore, Alice, Helen Lynch, and Bryan Boyle. 2022. “A National Study of Playground Professionals Universal Design Implementation Practices.” Landscape Research, 1–17. doi:10.1080/01426397.2022.2058478.

- National Standards Authority of Ireland (NSAI) Standards. 2021. “Accessibility and Usability of the Built Environment – Functional Requirements.” I.S. EN17210:2021&LC:2021. Dublin: NSAI.

- NSW Government. 2019. “Everyone Can Play: A Guideline to Create Inclusive Playspaces.” Accessed 16 June 2020. https://everyonecanplay.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-02/Everyone%20Can%20Play%20Guideline.pdf

- Olsen, Heather M. 2015. “Planning Playgrounds: A Framework to Create Safe and Inclusive Playgrounds.” Journal of Facility Planning, Design & Management 3 (1): 57–71.

- Parker, Ruth, and Sura Al-Maiyah. 2022. “Developing an Integrated Approach to the Evaluation of Outdoor Play Settings: Rethinking the Position of Play Value.” Children's Geographies 20 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1080/14733285.2021.1912294.

- Peters, Micah DJ, Christina M Godfrey, Hanan Khalil, Patricia McInerney, Deborah Parker, and Cassia Baldini Soares. 2015. “Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews.” International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 13 (3): 141–146. doi:10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050.

- Peterson, Jessica, Patricia F Pearce, Laurie Anne Ferguson, and Cynthia A Langford. 2017. “Understanding Scoping Reviews: Definition, Purpose, and Process.” Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners 29 (1): 12–16. doi:10.1002/2327-6924.12380.

- PlayCore, and Utah State University. 2016. Me2: 7 Principles of Inclusive Playground Design. Chatanooga, TN: PlayCore. https://www.playcore.com/programs/me2

- PlayCore, GameTime, and Utah State University. 2008. EveryBODY Plays!. Chatanooga, TN: PlayCore. http://www.google.ie/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=54&ved=0ahUKEwj60KTg2avKAhXD-A4KHTRKDlw4MhAWCC4wAw&url=http%3A%2F%2Focalafl.iqm2.com%2FCitizens%2FFileOpen.aspx%3FType%3D4%26ID%3D1491&usg=AFQjCNE6aR2p_WwwzEP-EnEFrFLJ4MUnKA.

- Play Wales. 2016. “Developing and Managing Play Spaces: A Community Toolkit.” 3rd ed. Accessed 16 June 2020. http://www.playwales.org.uk/login/uploaded/documents/Publications/Community%20Toolkit%202016.pdf

- Play Wales, and Alison John and Associates. 2017. “Creating Accessible Play Spaces: A Toolkit.” Accessed 16 June 2020. https://www.playwales.org.uk/login/uploaded/documents/Publications/Creating%20accessible%20play%20spaces.pdf

- Playworld. 2019. “Inclusive Play Design Guide.” Accessed 16 June 2020. https://odellengineering.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Playworld-Inclusive-Design-Guide.pdf

- Pooja Hiranandani, Vinita S., Kavitha Krishnamoorthy, and Ritu Gopal. 2016. Breaking Barriers Through Play: Policy Guidelines and a Technical Manual for Making Play Spaces Inclusive. Chennai: Kilikili. https://issuu.com/kilikili-inclusiveplayspace/docs/kilikili_technical_manual_28nov16_w

- Prellwitz, Maria, and Lisa Skär. 2007. “Usability of Playgrounds for Children with Different Abilities.” Occupational Therapy International 14 (3): 144–155. doi:10.1002/oti.230.

- Prellwitz, Maria, and Lisa Skär. 2016. “Are Playgrounds a Case of Occupational Injustice? Experiences of Parents of Children with Disabilities.” Children, Youth and Environments 26 (2): 28–42. doi:10.7721/chilyoutenvi.26.2.0028.

- Refshauge, Anne Dahl, Ulrika K Stigsdotter, and Nilda G Cosco. 2012. “Adults’ Motivation for Bringing Their Children to Park Playgrounds.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 11 (4): 396–405. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2012.06.002.

- Rick Hansen Foundation. 2019. “A Guide to Creating Accessible Play Spaces.” Accessed 16 June 2020. https://www.rickhansen.com/sites/default/files/downloads/sch-35913-guide-creating-accessible-play-spaceswebaccessible.pdf

- Rick Hansen Foundation. n.d. “Let's Play Toolkit: Creating Inclusive Play Spaces for Children of All Abilities.” Accessed 26 June 2020. https://www.rickhansen.com/sites/default/files/downloads/letsplaytoolkit.pdf

- Schöpfel, Joachim, Christiane Stock, Dominic Farace, and Jerry Frantzen. 2005. “Citation Analysis in Grey Literature: Stakeholders in the Grey Circuit.” The Grey Journal 1 (1): 31–40.

- Shackell, Aileen, Nicola Butler, Phil Doyle, and David Ball. 2008. Design for Play: A Guide to Creating Successful Play Spaces. Nottingham: The Department for Children, Schools and Families and the Department for Culture, Media and Sport. https://www.playengland.org.uk/resources/design-for-play.aspx

- Stafford, Lisa. 2017. “Journeys to Play: Planning Considerations to Engender Inclusive Playspaces.” Landscape Research 42 (1): 33–46. doi:10.1080/01426397.2016.1241872.

- Stanton-Chapman, Tina L, Eric L Schmidt, Carla Rhoades, and Lindsey Monnin. 2020. “An Observational Study of Children Playing on an Inclusive Playground and on an Universal Playground.” International Journal of Social Policy and Education 2 (2): 37–47.

- State of Victoria. 2007. “The Good Play Space Guide: I Can Play Too.” Accessed 16 June 2020. https://sport.vic.gov.au/resources/documents/good-play-space-guide-i-can-play-too

- Sterman, Julia J, Geraldine A Naughton, Anita C Bundy, Elspeth Froude, and Michelle A Villeneuve. 2020. “Is Play a Choice? Application of the Capabilities Approach to Children with Disabilities on the School Playground.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 24 (6): 579–596. doi:10.1080/13603116.2018.1472819.

- Touched by Olivia. 2012. “The Principles for Inclusive Play.” Accessed 16 June 2020. http://www.touchedbyolivia.com.au/wp-content/uploads/The-6-Principles-for-Inclusive-Play.pdf

- United Nations (UN). 1989. Convention on the Rights of the Child. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=IV-11&chapter=4&lang=en

- United Nations (UN). 2006. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-ofpersons-with-disabilities/article-7-children-with-disabilities.html

- Woolley, Helen. 2012. “Now Being Social: The Barrier of Designing Outdoor Play Spaces for Disabled Children.” Children & Society 27 (6): 448–458. doi:10.1111/j.1099-0860.2012.00464.x.

- Woolley, Helen, and Alison Lowe. 2013. “Exploring the Relationship Between Design Approach and Play Value of Outdoor Play Spaces.” Landscape Research 38 (1): 53–74. doi:10.1080/01426397.2011.640432.

- Yantzi, Nicole M., Nancy Lynn Young, and P. Mckeever. 2010. “The Suitability of School Playgrounds for Physically Disabled Children.” Children's Geographies 8 (1): 65–78. doi:10.1080/14733281003650984.

- Yuen, Chris H. C. 2016. “Inclusive Play Space Guide: Championing Better and More Inclusive Spaces in Hong Kong.” Hong Kong: Playright Children’s Play Association. https://playright.org.hk/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Playright-Inclusive-Play-Space-Guide.pdf