ABSTRACT

Policy perspectives on sustainability, particularly those dominating an era, can have long-lasting effects and shape the context in which decisions are made. Historical analyses of sustainability perspectives applied in policymaking can enrich our understanding of the sources contributing to decision-making processes. Through an in-depth analysis of policy documents published between 1986 and 2022 and interviews with former and current policymakers, we have studied the development of the Dutch regional government of Flevoland’s perspectives on sustainability in the agricultural sector. We developed a framework to guide our analysis of the concepts and rhetoric used and the assumptions made about social-ecological relationships, nature values, and structure and agency. Our findings show a gradual evolution of policy perspectives on sustainability, moving from an economic focus to recognising ecological value and the agricultural sector’s role in addressing environmental and social issues. However, aspects of social sustainability remain narrowly addressed, focusing on business aspects while overlooking farmers’ multifaceted roles and challenges. Moreover, despite encouraging farmer-led sustainability initiatives, the Province struggles to clarify its sustainability strategy and implement concrete measures. These insights can help challenge previously unquestioned or unknown assumptions and be instrumental in crafting better integrated and effective policy measures aimed at addressing sustainability challenges.

Introduction

The agricultural sector is under increasing pressure to confront the negative impacts of climate change and chart a course towards long-term sustainability. In recent decades, this has led to a surge in interdisciplinary research focused on sustainability within the agricultural sector (see for example Janker et al., Citation2018; Latruffe et al., Citation2016; Purvis et al., Citation2019; Slätmo et al., Citation2017). Despite ongoing efforts to find common ground on the definition and methods for achieving sustainability, the concept remains multifaceted and elusive (Janker et al., Citation2018; Vallance et al., Citation2011). As each conceptualisation or approach to sustainability is shaped by pre-existing assumptions, viewpoints, interests, and distinct notions of responsibility for future generations, the myriad perspectives create ambiguity (Abson et al., Citation2017; Hulme, Citation2009). If not properly addressed, this ambiguity can dilute the transformative impact of sustainability-oriented approaches and pose challenges to policymakers striving to harmonise and put into practice the ideals of sustainability (Abson et al., Citation2017; Hulme, Citation2009; Van Eeten, Citation1999).

The Brundtland Commission presented one of the most influential and widely acclaimed definitions of sustainability, describing it as ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (WCED, Citation1987, p. 40). In the years that ensued the report’s publication, and further developed by a proliferation of research from various disciplines and fields, three interdependent dimensions of sustainability were distinguished: environmental, economic, and social (Kuhlman & Farrington, Citation2010).

While the three-pillar model of sustainability remains a touchstone in current sustainability research, it also fuels ongoing debates. Although each dimension has been independently developed and extensively explored, scholars persistently advocate for a deeper investigation into the interrelations between them (e.g. Eizenberg & Jabareen, Citation2017; Littig & Grießler, Citation2005; Purvis et al., Citation2019). Especially within the agricultural domain, sustainability research has had a dominant focus on the environmental and economic aspects and is often critiqued for sidelining or neglecting the social dimension (Eizenberg & Jabareen, Citation2017; Janker & Mann, Citation2020; Latruffe et al., Citation2016; McCarthy et al., Citation2023). However, the significance of the social dimension has been repeatedly demonstrated. Chapman and colleagues (Citation2019), for example, showed how a disconnect with farmers’ values can result in failed sustainability interventions. Similarly, others have underscored the importance of incorporating social sustainability when analysing the correlations and trade-offs between the various dimensions (e.g. Desiderio et al., Citation2022; Galdeano-Gómez et al., Citation2017; Zhu & Oude Lansink, Citation2022).

The perspective on sustainability adopted by policymakers heavily impacts the approach taken during the policymaking process. This leads to multiple and sometimes contradicting perspectives on sustainability and ideas on how its ideals should be translated into practice, thereby limiting its development and implementation (Abson et al., Citation2017; Berg, Citation2020; Binder et al., Citation2010; Hulme, Citation2009; Van Eeten, Citation1999). Since policy processes typically occur within pre-established relationships, perspectives, and decision-making processes, changes over time tend to be limited or gradual (Gonzalez-Martinez et al., Citation2021; Steinmo, Citation2003; Walker et al., Citation2002). Such path-dependent processes emanate from a stickiness linked to institutions’ and actors’ attempts to preserve the existing model, even if it is suboptimal (Greener, Citation2002). Arguing from a path-dependency perspective, radical change only occurs ‘when external forces disrupt the institutional stability and the balance of interests that keep the political system in a state of equilibrium’ (Béland & Cox, Citation2011, p. 13). Consequently, the perspectives that dominate one era shape the context in which future choices are made, thus exerting a profound and long-lasting effect. When such perspectives overlook or undervalue one or more of the dimensions of sustainability, they can present a distorted view of the challenges at hand (Berg, Citation2020; Bradbury et al., Citation2019).

As we grapple with the multidimensionality of sustainability challenges, it is essential to become aware of the perspectives of policy-generating institutions and how they evolve. This understanding is crucial for comprehending past and current decision-making processes, which tend to inform future processes of change (Emekci, Citation2021; Gavin, Citation2020; Steinmo, Citation2003).

This paper examines changes in perspectives of policymaking institutions within the context of the Netherlands, a prominent global agricultural exporter with a strong commitment to sustainable production, biodiversity conservation, and climate change mitigation (Jukema et al., Citation2020). While the Dutch policy context is primarily characterised by ‘evidence based’ approaches, in which policymakers should make systematic, explicit and judicious use of the best available evidence when making decisions (Burssens, Citation2007; Greenhalgh & Russel, Citation2009), it is also famous for its ‘poldermodel’: a way of governance that is characterised by extensive consultation, negotiation and collaboration with and among various stakeholders (Jongeneel & Gonzalez-Martinez, Citation2021; Van der Maas, Citation2014). Due to this, the policymaking process is also a practical process of argumentation where multiple perspectives come together (Fischer & Forester, Citation1993).

More specifically, we explore the historical evolution of perspectives on sustainability in the agricultural sector of the Province of Flevoland, which is renowned for its pioneering efforts in land reclamation and agricultural development (Van der Maas, Citation2014; Van Dissel, Citation1991). We do so by shedding light on the shifts and continuities over time, unravelling the interplay between past and present approaches to sustainability employed by policymakers. Furthermore, by recognising and questioning the underlying, and often implicit, assumptions, values and power dynamics, this study aims to deepen our understanding of the many sources that contribute to both stability and change within policy processes. In turn, this can open up new avenues for challenging previously unquestioned or unknown assumptions and reveal what is needed to develop effective policies to address sustainability challenges in agriculture.

We applied an interpretive multi-method approach, combining document analysis and semi-structured interviews. An in-depth analysis was undertaken of 26 key policy documents, programmes and memoranda related to agriculture and published by the province between 1986 and 2022. We interviewed current and former employees of the province who had an active role in the development and implementation of one or more documents or programmes in Flevoland. Their insights helped contextualise and validate our findings from the document analysis, shedding light on the underlying ideas, concepts, and processes in policy development.

Developing an understanding of the perspectives embraced by the province and their evolution requires integrating insights from a diverse range of literature and disciplines. Building upon Dépelteau and Powell’s (Citation2013) elements of environmental discourses, and inspired by the arguments of West et al. (Citation2020) and Walsh et al. (Citation2021) for incorporating more relational thinking in sustainability sciences, we developed an analytical framework consisting of five elements to guide our analysis. We will discuss this framework in the next section. This will be followed by a description of the context and our research methods. After presenting our empirical findings, we conclude with a discussion of the findings and their implications.

Making sense of policy perspectives

According to Cameron and Maslen (Citation2010), perspectives are open-ended dispositions that we use to comprehend and generate intuitive structures of understanding about particular subjects or phenomena. As new information and experiences arise, perspectives can evolve, although their core remains stable. A perspective is informed by knowledge acquired during processes of interaction. As such, the transition from an individual perspective to that of an institutional organisation results from a dynamic interplay among various actors, institutions, and discourses (Barret et al., Citation1995; Stone, Citation2012). Through deliberation, negotiation, and collective action, individuals or groups articulate their perspectives and strive to influence how issues are addressed. In this process, actors consciously or unconsciously share their values, experiences, and ideologies and, through this, shape how they perceive and understand policy issues. As multiple actors engage in debates and mobilise support, certain perspectives gain legitimacy and recognition and become more widely accepted in the policy domain (Stone, Citation2012; Suddaby et al., Citation2010). This often results in a shared perspective that is reflected in both textual and verbal communication. Once these perspectives become embodied, they provide the context for further deliberation (Dryzek, Citation2022; West et al., Citation2020).

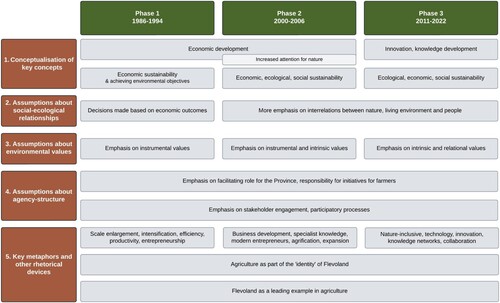

To better understand how and to what extent policy perspectives have developed over time, we developed a framework consisting of five key elements to interpret the perspectives reflected in policymaking processes: (1) conceptualisation of key sustainability concepts (CON) (2) assumptions about social-ecological relationships (S-ER), (3) assumptions about environmental values (EV), (4) assumptions about structure and agency (SA), and (5) key metaphors and other rhetorical devices (MET). These elements are based on and carefully adapted from literature on environmental discourse analysis, relational sociology, sustainability, and environmental change (Dryzek, Citation2022; Walsh et al., Citation2021; West et al., Citation2020). Moreover, the elements are interrelated and can overlap. Collectively, they shed light on the emphases, differences, and similarities in Flevoland’s policy perspectives over time. Based on their nature, CON and MET are expected to consistently emerge, whereas the presence and emphasis of the elements S-ER, EV and AS may vary. An overview of the elements is provided in .

Table 1. Analytical framework consisting of the 5 elements of a (sustainability) perspective.

The first element, Conceptualisations of Key Concepts (CON), considers how sustainability and agricultural issues are represented and conceptualised. Cook and Wagenaar (Citation2012) argue that language and concepts have an inherent performative character: they are tools that enable us to capture and compare different aspects of experience. The concepts used to address certain phenomena, such as sustainability issues, can therefore be seen as an emergent result of ever-changing patterns of material, social and cultural relationships, and can take on different meanings (Darnhofer et al., Citation2016; Dryzek, Citation2022). How they are used and conceptualised can reflect a set of beliefs about people or phenomena that influence the direction of thinking. Any operationalisation of sustainability goes hand-in-hand with normative choices and trade-offs concerning the use of resources and between different values, which can differ individually, organisationally and geographically (Sachs, Citation2015). Therefore, we chose not to predefine sustainability, but to search for definitions and conceptualisations of sustainability, sustainable agriculture and agriculture applied by the Province. We used the three-pillar model of sustainability (economic, ecological and social sustainability) to capture and compare what issues are highlighted within the key concepts. To provide further insight into how concepts are applied, we use the following subcategories: definitions, conceptualisations, approaches, issues and outcomes.

The second and third elements, Assumptions about Social-Ecological relationships (S-ER) and Environmental Values (EV), refer to the degree to which humans and nature are assumed to be interrelated and valued. Scholars from several domains have researched the influence of people’s connections to nature on sustainability outcomes and actions. Both people’s interactions with the world around them and how they value their environment shape the goals and paradigms underpinning many systems of interest (Abson et al., Citation2017). In policymaking processes, these relationships are usually assumed for large groups of people. These assumptions underpin the decisions made in, and outcomes of, policy plans and programmes (Chan et al., Citation2016; Muradian & Pascual, Citation2018), and are thus crucial components of a policy perspective on sustainability. It is therefore important to uncover what is assumed about the way humans interact with, and respond to, their natural environment. In this research, we differentiate between two elements. Assumptions about human-nature relationships (S-ER) refer to the position of humans in relation to their environment (Lejano, Citation2019; Schoon & Van Der Leeuw, Citation2015). Alongside assumptions, we also consider the approaches used. Assumptions about environmental values (EV) refer to the values that humans hold towards nature. For this, we distinguish between three types of values: instrumental, intrinsic, and relational values (Arias-Arévalo et al., Citation2017; Chan et al., Citation2016; Van den Born et al., Citation2018).

How problems are understood and addressed is generally influenced by actor-specific and/or contextual factors (Naito et al., Citation2022; Swinkels, Citation2020). The fourth element, Assumptions about Agency and Structure (AS), therefore refers to assumptions made about agency, meaning whether individuals are perceived as autonomous and driven by personal properties and forces, and structure, meaning whether opportunities for individuals throughout their lives are determined by external, constraining or enabling social entities (Dépelteau & Powell, Citation2013). To gain further insight into who or what is assumed to be influential in decision-making processes, we focus on who and what is given agency, how structural factors are addressed, and how responsibilities are allocated among the main actors.

Finally, the fifth element, Key Metaphors (MET), concerns metaphors and other rhetorical devices. In both text and speech, these play important communicative roles (Camp, Citation2019; Dryzek, Citation2022; West et al., Citation2020). To an extent, their effect stems from their ability to convince an audience by casting situations in a particular light (Camp, Citation2019). At the same time, metaphors tend to be rooted in thoughts and are part of broader clusters of meaning. They can thus be seen as an expression of the communicator’s perspective, and analysing metaphors can provide insight into the way the communicator understands phenomena (Cameron & Maslen, Citation2010). In this study, these metaphors are found in words, concepts and expressions that are used to describe key concepts or phenomena.

Materials & methods

Context

Before we continue our exploration of policy perspectives, it is important to note the historical factors that may influence decision-making processes and agricultural developments in Flevoland. This section presents a brief account of the development of Flevoland and elaborates on several key national and European agricultural policy developments.

Flevoland

The province of Flevoland is the youngest province of the Netherlands and holds a unique position in the Dutch agricultural context. Flevoland is the result of one of the world’s largest land reclamation projects. It was devised, created, and developed throughout the early and middle 1900s. The oldest part of the province, the Noordoostpolder, was completed in 1942, followed by Eastern and Southern Flevoland in the 1950s and 1960s (Van Dissel, Citation1991). One of the main goals of this newly established land was a modern agricultural sector capable of feeding the nation. For roughly forty years, procedures were implemented to select the new inhabitants of ‘the polders’, including its farmers, to create a perfect representation of Dutch society. This process was orchestrated by a specially established committee that conducted in-person evaluations of potential candidates. Selection criteria included farmers’ knowledge, motivation, education, financial situation, household situation and willingness to contribute to, and participate in, their communityFootnote1 (Vriend, Citation2022). Those who made it through the selection procedure acquired the unique status of ‘polderpioniers’Footnote2, which has been cultivated and cherished ever since (Van der Maas, Citation2014). As of today, almost seventy per cent of its land surface is allocated to agriculture (CBS, Citation2023) and the sector contributes approximately fifteen per cent of the province’s total added value (Venema & Verhoog, Citation2023). The development of the agricultural sector therefore strongly influences the quality of life and the environment in the Flevoland countryside.

Influential agricultural policy developments

The development of the province of Flevoland unfolded during a period dominated by an emphasis on economic growth, maximising productivity and efficiency, and scale enlargement of the Dutch agricultural sector. These developments were perpetuated and shaped by the European Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) in the 1960s with the introduction of guaranteed prices and subsidies (Paul, Citation2009). This resulted in a highly productive Dutch agricultural sector that focused on producing for export (Hollander, Citation2013).

From the 1980s onwards, the detrimental effects of agriculture on nature and the environment garnered attention and were reflected in several pivotal national policy plans (Manhoudt, Citation1998; van Lieshout et al., Citation2013). In the ‘Relatienota’ (Relations Memorandum)(Ministerie van Cultuur, Recreatie en Maatschappelijk werk, Citation1975), the Dutch government emphasised the importance of the interrelationships between nature and agriculture by focusing on the preservation of agricultural lands with high nature and landscape values. This was followed by the implementation of the Nature policy plan (Ministerie van Landbouw, Natuurbeheer en Visserij [LNV], Citation1990a), which focused on enhancing ecological structure and biodiversity while advocating sustainable land-use practices. This plan formed the basis for later developments and legislation in the field of nature conservation in the Netherlands. These developments were seen as a gradual broadening of the narrow productivist perspective of the Dutch government that prevailed during the previous years (van Lieshout et al., Citation2013).

Concurrently, the Dutch government presented a structural memorandum on agriculture (Ministerie van LNV, Citation1990b), that aimed for a safe, sustainable and healthy agricultural sector, and introduced a series of national environmental policy plans (NMPs) throughout the 1990s and early 2000s to address pressing environmental issues and set the stage for more sustainable agricultural practices. Moreover, at the European level, the CAP underwent several reforms, progressively incorporating international trade and environmental considerations into existing policy objectives. This shift reflects an increasing recognition of the necessity to reconcile agricultural productivity with environmental sustainability (for more comprehensive analyses of the CAP, see Daugbjerg & Swinbank, Citation2016; Erjavec & Erjavec, Citation2015; Citation2020).

In the Netherlands, more recent developments have set a different course. With the 2013 Nature Pact, the Dutch government aimed to revise and modernise nature policy in response to public discussions on the protection and development of nature in the Netherlands. This initiative, aimed to find a balance between the interests of nature conservation and economic development, envisioned a greater responsibility for provinces in establishing nature objectives and the management of nature reserves, and called for increased societal engagement (Buijs et al., Citation2022). Research by Buijs and colleagues (Citation2022) showed that this led to a diversity in strategies between the twelve Dutch provinces, with Flevoland focusing primarily on the capitalisation of ecosystem services for new financial resources.

In 2018, Dutch agricultural policy was further steered in a new direction with the Agricultural Vision ‘Waardevol en Verbonden’ (‘Valuable and Connected’, Ministerie van Landbouw, Natuur en Voedselkwaliteit, Citation2018). This emphasised a transition towards a circular agricultural model while promoting a stronger connection between agriculture and nature. Central to this vision was improving the position of farmers by ensuring substantial incomes, fostering innovation, and sustaining and passing on healthy businesses. This vision, complementary to the 2014 national Nature Vision, was the first step towards a long-term perspective for the agricultural sector (Wageningen University & Research, Citation2018). While there has since been an attempt to reach an Agricultural Agreement to provide the agricultural sector with a long-term perspective, the complexity of the issues at hand, different interests, and distrust resulted in the termination of negotiations in 2023 (NOS.nl, Citation2023; Trouw.nl, Citation2023).

Methods

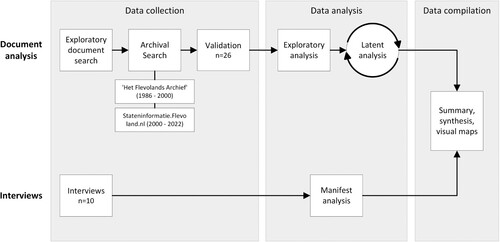

This study employs an interpretive multi-method approach to explore perspectives on sustainability in the agricultural sector from a regional institutional point of view. Applying an interpretive approach enables an in-depth investigation into specific contextualised processes of meaning-making and an exploration of hidden meanings behind the complex and interrelated processes of developing agricultural plans and programmes (Schwartz-Shea & Yanow, Citation2014). By complementing the document analysis with interviews, we tap into the content of final plans and add analytical depth by exploring cognitive processes, personal experiences and viewpoints that shape these documents. Interviews further allow us to explore major patterns and shifts in policy orientation and meaning over time as experienced by the participants, further validating our findings from our document analysis (Biggs et al., Citation2022). A visual representation of our methods is provided in .

Both the document analysis and interviews were conducted in Dutch. The codes and quotes used in this paper were subsequently translated into English by the authors.

The temporal scope considered in this study spans from 1986 to 2022. The year 1986 marks the year that Flevoland was officially established as the twelfth province of the Netherlands. 2022 is the last full year for which information was available at the time of this research.

Document analysis

Key policy documents, plans, programmes, and memoranda published by the Province of Flevoland between 1986 and 2022 were analysed using an interpretive document analysis approach (Altheide et al., Citation2008; Browne et al., Citation2019). In selecting documents, we followed a triangulation approach. First, we scoured scientific and policy papers for references to policy documents, thereby obtaining a preliminary set of potentially relevant policy documents. This was followed by an archival search. For documents up to 2000, we accessed the physical provincial archives (Het Flevolands Archief). Materials published after 2000 were accessed through the online platform Stateninformatie.Flevoland.nl. Throughout this process, we systematically narrowed down our selection based on the frequency and ways in which policy documents were mentioned. This continued until no new documents emerged. Finally, three policy advisers of the Province of Flevoland were consulted to validate the selection and ensure that all the most pertinent and influential documents were included.

This process resulted in a set of 26 documents (Appendix A), including strategic, planning and policy documents. Nine documents were aimed at future activities and outcomes in the agricultural domain. The other 17 documents related to other domains in which the agricultural sector played a substantial role, such as nature development and land-use planning. The sample size, based on our informational need, relevance and distribution over the period, was considered adequate to address the research goals with sufficient confidence.

The analysis process can be characterised as an iterative process of sense-making (Schwartz-Shea & Yanow, Citation2014), in which each document was read multiple times during several stages to explore the representation and framing of the five key elements: (1) conceptualisations of sustainability, sustainable agriculture and farming; (2) assumptions about social-ecological relationships; (3) assumptions about environmental values; (4) assumptions about agency and structure; and (5) key metaphors and other rhetorical devices.

The first stage was exploratory in nature and aimed at familiarising ourselves with the data and examining the overall content of documents. During this stage, we also refined our codebook. The categorisation of themes and codes was informed by a literature review and supplemented by emergent category designation, where categories derived from the assessed documents were added (Erlandson et al., Citation1993) (for the full codebook, see Appendix B).

In the second stage, we conducted a latent analysis, using ATLAS.ti, to explore underlying meanings, themes, and interpretations in the texts (Lune & Berg, Citation2017). Statements were analysed regarding their discursive context and coded accordingly. To ensure the quality and reliability of the analysis, this phase was performed several times, each time focusing on different elements.

In the third stage, all the collected data were summarised, synthesised and further interpreted to create a deeper holistic understanding of the material (ibid.). Visual mapping techniques were used to identify general perspectives, patterns over time and discrepancies between documents (Parmentier-Cajaiba & Cajaiba-Santana, Citation2020).

Interviews

Parallel to the document analysis, interviews were conducted with current and former employees of the Province to gain further insight into the underlying ideas, concepts, and processes of Flevoland’s policy development. Participants were selected based on their active role in the development and implementation of one or more documents or agricultural programmes in Flevoland. The interviewees were recruited through the researchers’ network and snowball sampling. Ten individuals were interviewed, including three former and six current employees plus one member of the provincial executive council. Interviews lasted from fifty minutes to two hours in length.

The interviews followed a semi-structured design and adopted a narrative approach in which data emerged dynamically through a dialogue between researcher and interviewee, rather than a strict question-and-answer format (Fujii, Citation2018) (Appendix C). The goal of the interviews was to capture each interviewee’s subjective experiences and perspectives related to the development and implementation of the policy plans, such as their views on the policy process, farming and sustainability, approaches to farming in Flevoland, and developments over time. As the nature of the interviews differed from our document analysis, we adapted our codebook to include the main topics from the interview.

With the permission of the interviewees, interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. A manifest analysis was conducted using ATLAS.ti software.

Results

This section explores the nuanced understanding of sustainability in the agricultural sector from the viewpoint of the province of Flevoland. Drawing on insights from our document analysis and interviews, we identified prevailing perspectives related to three distinct phases that correspond to periods in which the province developed programmes and plans on multiple topics.Footnote3 Each of these phases is, to differing extents, characterised by their approaches to sustainability, the underlying assumptions about social-ecological relations and environmental values, and the metaphors and rhetoric devices employed (). After some general insights on the conceptualisation of sustainability, we proceed to describe these three phases, elucidating their specific characteristics and the changes that have occurred over time. This is followed by a brief exploration of the continuities that endure amidst these changes.

Figure 2. Overview of changes and continuities in the Province of Flevoland's perspective on sustainability in the agricultural sector over time.

Approaches to sustainability

How sustainability is addressed in the Flevoland policy discourse reflects changing understandings and priorities of economic, environmental, and societal challenges (CON). Drawing on insights from our document analysis and interviews, we found that sustainability was a prominent issue throughout all periods, although the terminology used varied. ‘Sustainability’, ‘vitality’, and ‘robustness’ were commonly adopted terms to refer to processes of change wherein specific attention is paid to the long-term well-being of the environment and citizens. Since 2014, the concept of ‘futureproofing’ has also gained prominence to reflect similar sentiments. Nevertheless, only seven documents attempted to explain sustainability in any detail. These documents originate from the period between 1993 and 2003 and align with the definition of sustainability outlined in the Brundtland report.

Ecological issues were prominent in almost all the documents and interviews, with environmental considerations addressed directly through specific regulations and goals that were aimed at minimising negative impacts. Terms, such as ‘environmental carrying capacity’, ‘ecosystem services’, ‘environmental impact’ and ‘clean production’ have been frequently employed in referring to sustainability in the agricultural sector.

Further, economic viability is frequently acknowledged as a crucial factor in sustainable development. Although the emphasis on this varies over time, as will be further delineated in the following sections, the overall objective of maintaining farmers’ incomes and ensuring economic stability while pursuing ecological goals had remained a recurrent theme.

On a more social level, education, knowledge development and knowledge transfer all play a substantial role in seeking to foster sustainability within the agricultural sector. Emphasis is placed on equipping farmers with the necessary tools and information to make informed decisions when responding to sustainability challenges. The province further supports and facilitates collaboration among farmers, highlighting the benefits of sharing experiences, expertise, and resources as a means of motivating farmers to take up sustainability initiatives.

While this might appear to show that the province is making great strides with sustainability initiatives, the elaboration and implementation of concrete measures remains superficial, as also recognised by several interviewees. One policymaker described it as follows:

The thinking is already quite advanced. … So, let’s say, the idea in an abstract form, that already exists. And that has also penetrated quite a bit at the ambition level. For example, those councillors, they all think it should be done, but it is mainly about the concrete implementation, putting flesh on the bones. … This is seen as difficult: it is seen as expensive, and it is not made clear what it actually yields. (interviewee 10)

Perspectives over time; three phases

Phase 1: 1986–1994, agricultural growth and economic development

Following the official establishment of the province of Flevoland in 1986, a series of strategic and vision documents were developed to guide the development of the agricultural sector. We analysed a total of eight documents from the period of 1986 to 1994 that specifically addressed the development of the agricultural sector in Flevoland. These included five agriculture-specific documents, a social-economic policy plan, an environmental policy plan and an area development plan. Analysis of these documents showed that this phase was characterised by two primary objectives: agricultural growth and the economic development of specific sectors.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the main goal outlined in policy documents was to continue Flevoland’s pioneering activities and establish its status as a modern, leading, agricultural province. With its ‘functional design and structure’ and ‘excellent conditions for modern agriculture’, the Province was expressing the need for economic development of the agricultural sector as the driver for Flevoland’s development. Terms, such as ‘scale enlargement’, ‘intensification’, ‘efficiency’, ‘productivity’, ‘yield level’ and ‘entrepreneurship’ dominated.

The early 1990s saw a tentative increase in awareness of the need to care for nature. The 1987 Brundtland Report was frequently cited in several provincial documents as a signifier of the need for change. Additionally, the concept of sustainability and its definition as proposed by the Brundtland Commission were frequently referenced. However, the primary reason for this attention to nature was problem-oriented: the agricultural sector encountered stricter nature and environmental regulations set at the national level, alongside mounting pressure from politicians and the public ‘to prioritise sustainability’. At the same time, the sector was grappling with low prices, overproduction, and uncertainty about its future. The provincial focus was on addressing specific environmental issues and finding mitigating solutions, such as a reduction in agrochemical use to comply with the regulations set by the Dutch government. However, each regulation or issue was being addressed in isolation, without considering its potential impact on other environmental issues, or other aspects of farmers’ business models or daily lives (CON, SA and MET).

Similar lines of thinking are reflected in the assumptions made about social-ecological relationships (S-ER) and environmental values (EV). Most documents from this period frame nature as instrumental to the agricultural sector, with the quality of the environment, water and soil being seen as important for agricultural production and yields. The emphasis was not on preserving nature for its own sake but, rather, on complying with the rapidly increasing number of regulations in ways that did not hinder economic development. In other words, the goal was to maximise profitability within the constraints of the statutory framework.

The primary reasoning for this approach appears to be the often-expressed limited knowledge at the time regarding the influence of agriculture on the environment, such as little practical understanding of the effects of specific actions, long-term solutions and their consequences, combined with the often stated assumption that farmers would be unwilling to invest in environmental measures due to the uncertainties about their economic outcomes. In response to this knowledge gap, the province repeatedly expressed a need to acquire and exchange knowledge on environmental issues, both between organisations and farmers as well as among farmers themselves.

Despite this focus on economic development and progress, the ending of this phase did foreshadow the beginning of a shift in priorities away from a sole focus on maximising profitability.

Phase 2: 2000–2006, continuing development and solidifying stability

The second phase identified in the analysis spans the period from 2000 to 2006. Four documents from this period were examined, including two that were specific to agriculture, a memorandum and action programme on agricultural development, as well as the long-awaited integral environmental plan of 2006 (plus its predecessor from 2000). These documents outlined the main environmental, economic, social, cultural, and agricultural policies of the Province that were implemented over several years beyond this phase.

In many respects, the early 2000s saw a continuation of trends from the previous years. The emphasis remained on the economic development of specific sectors, with nature as still being largely perceived as instrumental for agricultural production and profitability (S-ER and EV). A policymaker working in the agricultural domain during this period stated:

It was about the economic development really. How do we see agriculture developing further? But, within a broader palette. But it was really still very much about economics – agricultural economics. That was really the angle. … We also thought … we have to do everything for the benefit of those sectors and the spatial design follows from that … and I quickly sensed that in those first conversations with the provincial executives [during that period]. Agriculture is important: it is Flevoland’s calling card. Our leading agricultural sector must … no, not be facilitated as much as possible, but it must be given the space to develop further. Everything else was, I might almost say, secondary to this. (interviewee 5)

During this time, the province also began to slowly recognise the interconnections between agriculture, the environment, and its citizens, as well as the role played by the agricultural sector. The documents reveal a desire for a sector that serves as ‘the carrier of the vitality of the rural area’. Agriculture was not only seen as contributing to regional economic development but also as having a responsibility for maintaining the quality of the rural area. Providing opportunities for farmers was seen as a key factor in achieving this goal.

This shift in thinking also reflected a move from a strictly sectoral approach to a more spatial perspective. The 2006 environmental plan demonstrated the province’s awareness of the interrelationships between domains such as agriculture, nature, health, and society. With regard to social-ecological relationships (S-ER), the environment and society were increasingly considered as interconnected wholes that dynamically interact with one another. The goal was to create greater cohesion between societal structures and Flevoland’s landscape and environment. This is particularly evident in the focus on ‘area-oriented approaches’. As awareness of the interrelationships between people and their environment grew, assumptions about environmental values (EV) shifted as well. Rather than being viewed solely as a means to achieve agriculture’s economic profitability, both the development and conservation of nature were increasingly viewed as goals in their own right. Greater attention was paid to the value of green spaces, biodiversity, preserving natural processes and restoring environmental systems.

These shifts in thinking were aligned with broader regional and societal trends, as well as advances in knowledge about environmental issues: their impacts, sources, and strategies for addressing them. As the scientific concept of sustainability evolved, and the effects of environmental degradation and human activity became more widely understood, the province began to seek ways to address these challenges.

Phase 3: 2011–2022, progress through area development and optimisation

Compared to the previous two phases, the period from 2011 onwards demonstrates a rather different approach to the agricultural sector and related policy themes. A total of fourteen documents from the period between 2011 and 2022 were analysed, with the majority focusing on the topics of nature and the broader environment. Only two documents specifically pertain to the agricultural sector, reflecting a shift from a sectoral approach to policymaking to a more integrated approach.

Apart from some small-scale programmes and funding, very few documents specific to agriculture were issued after 2006. The 2006 environmental plan and POP3 (Flevoland’s interpretation of the CAP’s Rural Development Programme) were, until 2017, considered as containing the main agricultural policies of the region. In 2017, with the introduction of a provincial environmental vision, agriculture once again became a major theme in the programme ‘Agriculture: Multiple Flavours’ (Landbouw: Meerdere Smaken). Other influential documents published during this period, although not directly aimed at the agricultural sector but in which it plays a principal role, included the ‘Action plan for soil and water’ and the ‘Agenda vital countryside’. Two overlapping but distinct themes dominated these documents. On the one hand, this period was characterised by a continuous and strong focus on development through technological innovation. By stimulating and facilitating farmers to experiment with innovative technologies, continuously develop their business plans, business models and approaches to farming, and share knowledge among themselves, the province sought to ‘lead the way’ in becoming a sector in which ‘innovation is put into practice’ (CON and MET).

Simultaneously, ecological conditions emerged as a leading theme: securing soil, water and environmental conditions was recognised as a prerequisite for a healthy and sustainable sector. Several documents of this period stated that social and economic developments should no longer impede ecological ones. The centralisation of the ecological dimension as a driver became even more prominent in the later part of this period, with terms such as ‘nature-inclusive development and agriculture’ gaining ground.

These sentiments were also reflected in other documents from this phase. Overall, the documents reviewed show increasing attention to the vitality and development of the region, encompassing environmental and communal aspects, rather than focused on sectors. Nature and the environment were increasingly regarded as something to be protected, enjoyed, appreciated, and experienced, as reflected in expressions concerning the experience of environmental and cultural landscapes and their connection to people’s identity. This highlights a shift in what was assumed about social-ecological relationships (S-ER) and environmental values (EV).

A concrete consequence of this shift was in the way the documents addressed action and responsibility (SA). From 2014 onwards, most documents were focused on stimulating and facilitating citizens (and especially farmers) to establish ‘knowledge networks’, collaborate with other farmers and initiate their own efforts towards a more sustainable sector.

Continuity despite change

Although several shifts and changes over time have been identified, it is equally important to recognise that certain underlying threads continued. These continuities, as much as the emerging trends and shifting paradigms, served as crucial touchstones that shaped and guided the policy processes.

With regard to assumptions about structure and agency (SA), there is a continued emphasis on stakeholder engagement and participatory processes. Throughout all phases, the analysed plans and programmes were generally characterised by co-governance and bottom-up approaches. Cooperation between stakeholders, both in the development and the implementation processes, plays a key role in the Flevoland context, as reflected by terms such as ‘cooperation’, ‘knowledge networks’, and ‘experimentation’. Much of the responsibility for initiating change is placed on farmers. The province’s role is more commonly framed as facilitating and inspiring. According to the interviewees, this has resulted in a good working relationship with farmers and short communication lines, which are seen as the main strengths of the region’s agricultural sector, as illustrated by the following quotes:

Our entire agricultural programme is inherently bottom-up. … So in principle the approach is always: A farmer wants something, can we see if we can find coherence in that? … We are quite approachable. We easily become enthusiastic when a group of farmers wants something. … If it fits within our policy. … We recognise that you have your own business, you must do it eventually, not me. And I think they sense that (interviewee 9, emphasis added).

Since you cannot do that from above. You can develop ideas from above and then say to the stakeholders: well, we have this idea, and we actually want to go that way. We have discussed this with the provincial council and now we want to work it out with you to see how it can be realised (interviewee 2, emphasis added).

The final continuity we would raise refers to the use of certain metaphors and terminology with regard to the framing of agriculture (MET). The origins of the province have consistently permeated the discussion on agricultural development over time. From its ‘functional design’, characterised by the ‘well thought-out allotment’ of land and ‘strong entrepreneurial spirit’ during the earlier years to the cherishing and experiencing of the ‘qualities of the landscape’ in more recent years. Nevertheless, two storylines remain consistent: the framing of the agricultural sector as the backbone of the Flevoland landscape, and the persisting desire to serve as a leading example of modern agricultural entrepreneurship and innovation, thereby further perpetuating its pioneering status. As such, the importance of the agricultural sector in Flevoland, whether as a sector in its own right or as part of the rural area, is embedded in its history and identity and therefore continues to shape its future development. As one policymaker put it: ‘You won’t have to further develop the [Flevoland] countryside at all if you no longer have agriculture’ (interviewee 6).

Discussion and conclusion

In this study, we applied an explorative approach to investigate the development of the provincial government of Flevoland’s perspectives on sustainability in the agricultural sector. As such, it does not claim to encompass the entire spectrum of stakeholder perspectives, beliefs, and motivations, nor does it consider the impact of sustainability measures on practice. However, by applying an interpretive historical approach, we were able to uncover the continuities and shifts in perspectives by interrogating the concepts and rhetoric employed and the assumptions that were made. We did so by focusing on five elements: (1) conceptualisation of key concepts (CON), (2) assumptions about social-ecological relationships (S-ER), (3) assumptions about environmental values (EV), (4) assumptions about structure and agency (SA), and (5) key metaphors and other rhetorical devices (MET), facilitating a deeper understanding of the perspectives of a regional governmental organisation on sustainability.

Our analysis reveals that the Province’s perspectives on sustainability have evolved gradually over time, slowly adapting to incorporate, often novel, ideas that correspond with broader political and public discussions. This pattern aligns with the path-dependency literature (Steinmo, Citation2003; Stone, Citation2012; West et al., Citation2020), suggesting that, at least during the period under consideration, the province of Flevoland has embodied a shared perspective on sustainability and built upon this existing framework when confronted with new challenges.

Despite this general evolution of perspectives, the analysis revealed disparities in the presence and emphasis of the elements. S-ER and EV evolved from being instrumentally and economically oriented towards a focus on ecological quality and value. Moreover, as knowledge of environmental issues and sustainability grew, the interconnections between society and the environment were increasingly recognised (S-ER). This resulted in the increased use of spatial approaches, wherein the agricultural sector assumed a serving rather than a leading role. The emphasis became less on the economic development of the sector and more on the role of agriculture in the broader domain of environmental and social issues (CON). These shifts revolve around the centralisation of nature in sustainability narratives and align with broader policy themes and discourse changes in European and national contexts that have been previously described by several authors (e.g. Buijs et al., Citation2022; Daugbjerg & Swinbank, Citation2016; Erjavec & Erjavec, Citation2015; Citation2020; van Lieshout et al., Citation2013).

Social sustainability, although steadily acknowledged over the decades, has often been approached with a narrow view. By prioritising knowledge development and exchange, cooperation, and networking, the province has underscored social issues within the business realm of agriculture, portraying farmers as entrepreneurs rather than farms being the personal domain of farmers. This approach overlooks the multifaceted roles that farmers play within their communities and the myriad personal and societal challenges that they encounter.

Incorporating social sustainability, however, often comes with challenges, especially with regard to public policy (Boström, Citation2012). Conceptual ambiguity (Åhman, Citation2013; Janker et al., Citation2019; Vallance et al., Citation2011), its particular understanding in regard to specific contexts (Eizenberg & Jabareen, Citation2017; Littig & Grießler, Citation2005), or the highly normative questions it tends to address regarding, for example, social structures, values, and perceptions (Dijk et al., Citation2017; Janker & Mann, Citation2020; Littig & Grießler, Citation2005) tend to make it more difficult to measure than environmental and economic aspects. Since formal modes of knowledge production tend to excel at producing factual knowledge of and insights into the world, they do not always consider how people engage with and understand the world (Bradbury et al., Citation2019; West et al., Citation2020). As a result, and in line with observations made by Ly and Cope (Citation2023) a pattern has emerged within the Province’s perspectives where social sustainability is addressed only with regard to physical goals, overlooking the intangible aspects of a community.

These challenges are further illuminated by the continuities we found regarding assumptions about structure and agency (SA) and the conceptualisation of sustainability (CON). Throughout all the periods studied, the Province has consistently valued and encouraged farmers to take responsibility and initiative in sustainability endeavours and generate new ideas. Yet, it has also remained abstract in its conceptualisation of what sustainability means and which aspects it includes, leaving room for diverse interpretations and approaches. While this can foster creativity and innovation, overly divergent ideas can highlight disagreements that easily lead to controversy and deadlock (Abson et al., Citation2017; Van Eeten, Citation1999).

This is further illustrated by the Province’s ongoing struggle to implement concrete measures, despite recurring discussions surrounding the need for clear targets and measurable objectives. Previous research by Mandryk et al. (Citation2015) found similar challenges, stating that too much uncertainty and fragmentation of stakeholders’ interests in Flevoland renders the implementation of adaptation strategies extremely difficult. Ultimately, this can serve as a significant institutional constraint in Flevoland’s agricultural sector and can likely continue to serve as barriers to transformation unless these aspects are better understood and addressed (Berg, Citation2020; Mandryk et al., Citation2015).

To conclude, we have been able to reveal how the Province of Flevoland’s perspectives on sustainability have gradually evolved to incorporate ideas that align with broader political and public discussions, centralising ecological sustainability, while struggling to effectively incorporate social sustainability. This highlights the importance of understanding the underlying perspectives and values within Flevoland’s policy landscape and demonstrates the evolving nature of regional policy decision-making processes.

We contribute to the existing literature with the construction of a framework encompassing the elements necessary for analysing the (shifting) perspectives of sustainability in agricultural policy. We recognise that the results are context-specific and may vary over time. Along with our interpretive approach, this makes it challenging to compare findings between different studies. However, the framework has proven effective in analysing different perspectives and can be applied and further tested in different contexts around the world.

Moreover, further research is recommended to comprehend the full spectrum of sustainability challenges in the agricultural sector in Flevoland, particularly with regard to social sustainability. In addition, to provide insights into the differences and similarities between policy perspectives and on-the-ground realities, it is imperative to gain a better understanding of farmers’ perspectives, which requires an understanding of ‘inner worlds’, such as values and thoughts, and addressing topics such as place attachment and identity (Grenni et al., Citation2020; Horlings, Citation2015; Ives et al., Citation2020). For the Province of Flevoland, this would lead to the challenge of, first, clarifying its stance on the meaning of sustainability in the context of their region and, second, creating opportunities for dialogue with stakeholders to foster mutual understanding and engagement, thereby reducing confusion and establishing a solid foundation for discussing sustainability challenges.

Ultimately, questioning, studying and discussing implicit or unknown assumptions can help policymakers and stakeholders develop more integrated, contextually relevant and effective policy measures that are crucial to enforcing the change necessary for sustainability challenges in Flevoland and beyond its borders.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee Social Sciences of Radboud University (reference no. ECSW-LT-202303013013344).

AppendixC_Interview_guideline.docx

Download MS Word (28.1 KB)AppendixB_codebook_documentanalysis_revised.xlsx

Download MS Excel (13 KB)AppendixA_fullcorpus_revised.docx

Download MS Word (17.3 KB)Disclosure statement

In accordance with Taylor & Francis policy and my ethical obligation as a researcher, I am reporting that I have an affiliation with a company that may be affected by the research reported in the enclosed paper. I have disclosed those interests fully to Taylor & Francis, and I have in place an approved plan for managing any potential conflicts arising from this affiliation.

Notes

1 This a very brief and simplified account of Flevoland’s history. For a more detailed account of the selection procedure, see van Lieshout et al. (Citation2013). Van Dissel (Citation1991) provides a more detailed account of the reclamation project of the IJsselmeerpolders.

2 The term ‘polderpionier’ was strictly speaking reserved for those who had worked at the organisation that oversaw the reclamation of the Flevoland Polders for at least two years prior to August 1945. Nowadays, the term is popularly used when referring to the area’s first generation of inhabitants (Van der Maas, Citation2014).

3 Our analysis consists of 26 documents published between 1986 and 2022. The publication of documents was not evenly distributed across all years. The gaps between the phases result from gaps in the publication of relevant documents.

References

- Abson, D. J., Fischer, J., Leventon, J., Newig, J., Schomerus, T., Vilsmaier, U., von Wehrden, H., Abernethy, P., Ives, C. D., Jager, N. W., & Lang, D. J. (2017). Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio, 46(1), 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0800-y

- Åhman, H. (2013). Social sustainability – society at the intersection of development and maintenance. Local Environment, 18(10), 1153–1166. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2013.788480

- Altheide, D., Coyle, M., DeVriese, K., & Schneider, C. (2008). Emergent Qualitative Document Analysis. In S. N. Hesse-Biber, & P. Leavy (Eds.), Handbook of emergent methods (pp. 127–151). Guilford Press.

- Arias-Arévalo, P., Martín-López, B., & Gómez-Baggethun, E. (2017). Exploring intrinsic, instrumental, and relational values for sustainable management of social-ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 22(4). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09812-220443

- Barret, F. J., Thomas, G. F., & Hocevar, S. P. (1995). The central role of discourse in large-scale change: A social construction perspective. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 31(3), 352–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886395313007

- Béland, D., & Cox, R. H. (Eds.). (2011). Introduction: Ideas and politics. In Ideas and politics in social science research (pp. 3–20). https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199736430.001.0001

- Berg, C. (2020). Sustainable action: Overcoming the barriers. Routledge.

- Biggs, R., Vos, A. d., Preiser, R., Clements, H., Maciejewski, K., & Schlüter, M. (2022). The Routledge Handbook of Research Methods for Social-Ecological Systems. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003021339

- Binder, C. R., Feola, G., & Steinberger, J. K. (2010). Considering the normative, systemic and procedural dimensions in indicator-based sustainability assessments in agriculture. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 30(2), 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2009.06.002

- Boström, M. (2012). A missing pillar? Challenges in theorizing and practicing social sustainability: Introduction to the special issue. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 8(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2012.11908080

- Bradbury, H., Waddel, S., O’brien, K., Apgar, M., Teehankee, B., Fazey, I., Waddell, S., O’ Brien, K., Apgar, M., Teehankee, B., & Fazey, I. (2019). A call to Action Research for Transformations: The times demand it. Action Research, 17(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750319829633

- Browne, J., Coffey, B., Cook, K., Meiklejohn, S., & Palermo, C. (2019). A guide to policy analysis as a research method. Health Promotion International, 34(5), 1032–1044. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/day052

- Buijs, A., Kamphorst, D., Mattijssen, T., van Dam, R., Kuindersma, W., & Bouwma, I. (2022). Policy discourses for reconnecting nature with society: The search for societal engagement in Dutch nature conservation policies. Land Use Policy, 114, 105965. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105965

- Burssens, D. (2007). Hoe evident is evidence-based? Alert, 33(3), 52–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03057285

- Cameron, L., & Maslen, R. (2010). Metaphor analysis. Research practice in applied linguistics, social sciences and the humanities. Equinox publishing.

- Camp, E. (2019). Perspectives and Frames in Pursuit of Ultimate Understanding. In S. R. Grimm (Ed.), Varieties of Understanding: New perspectives from philosophy, psychology, and theology (17–46). Oxford University Press.

- CBS. (2023). Regionale Kerncijfers Nederland. Retrieved 29 September 2023, from https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/70072ned/table?dl=922F5

- Chan, K. M. A., Balvanera, P., Benessaiah, K., Chapman, M., Díaz, S., Gómez-Baggethun, E., Gould, R., Hannahs, N., Jax, K., Klain, S., Luck, G. W., Martín-López, B., Muraca, B., Norton, B., Ott, K., Pascual, U., Satterfield, T., Tadaki, M., Taggart, J., & Turner, N. (2016). Why protect nature? Rethinking values and the environment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(6), 1462–1465. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1525002113

- Chapman, M., Satterfield, T., & Chan, K. M. A. (2019). When value conflicts are barriers: Can relational values help explain farmer participation in conservation incentive programs? Land Use Policy, 82, 464–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.11.017

- Cook, S. D. N., & Wagenaar, H. (2012). Navigating the eternally unfolding present: Toward an epistemology of practice. American Review of Public Administration, 42(1), 3–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074011407404

- Darnhofer, I., Lamine, C., Strauss, A., & Navarrete, M. (2016). The resilience of family farms: Towards a relational approach. Journal of Rural Studies, 44, 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.01.013

- Daugbjerg, C., & Swinbank, A. (2016). Three decades of policy layering and politically sustainable reform in the European Union’s Agricultural Policy. Governance, 29(2), 265–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12171

- Dépelteau, F., & Powell, C. (2013). Applying relational sociology. Relations, networks and society. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Desiderio, E., García-Herrero, L., Hall, D., Segrè, A., & Vittuari, M. (2022). Social sustainability tools and indicators for the food supply chain: A systematic literature review. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 30, 527–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.12.015

- Dijk, M., de Kraker, J., van Zeijl-Rozema, A., van Lente, H., Beumer, C., Beemsterboer, S., & Valkering, P. (2017). Sustainability assessment as problem structuring: Three typical ways. Sustainability Science, 12(2), 305–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-016-0417-x

- Dryzek, J. S. (2022). The politics of the earth. Environmental discourses (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Eizenberg, E., & Jabareen, Y. (2017). Social sustainability: A new conceptual framework. Sustainability, 9(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9010068

- Emekci, S. (2021). Understanding the meanings of sustainability: Historical roots, current perspectives, future directions. ICA EAST 21. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357449622.

- Erjavec, K., & Erjavec, E. (2015). ‘Greening the CAP’ – Just a fashionable justification? A discourse analysis of the 2014-2020 CAP reform documents. Food Policy, 51(2015), 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.12.006

- Erjavec, K., & Erjavec, E. (2020). The noble or sour wine: European Commission’s competing discourses on the main CAP reforms. Sociologia Ruralis, 60(3), 661–679. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12300

- Erlandson, D. A., Harris, E. L., Skipper, B. L., & Allen, S. D. (1993). Doing naturalistic inquiry. A guide to methods. SAGE Publications.

- Fischer, F., & Forester, J. (1993). The argumentative turn in policy analysis and planning. Duke University Press.

- Fujii, L. A. (2018). Interviewing in Social Science. A relational approach. Routledge.

- Galdeano-Gómez, E., Aznar-Sánchez, J. A., Pérez-Mesa, J. C., & Piedra-Muñoz, L. (2017). Exploring synergies among agricultural sustainability dimensions: An empirical study on farming system in Almería (Southeast Spain). Ecological Economics, 140, 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.05.001

- Gavin, F. J. (2020). Thinking historically: A guide for policy. In A. Wenger, U. Jasper, & M. D. Cavelty (Eds.), The politics and science of prevision (1st ed., pp. 73–88). Routledge.

- Gonzalez-Martinez, A. R., Jongeneel, R., Kros, H., Lesschen, J. P., de Vries, M., Reijs, J., & Verhoog, D. (2021). Aligning agricultural production and environmental regulation: An integrated assessment of the Netherlands. Land Use Policy, 105(105388), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105388

- Greener, I. (2002). Theorising path-dependency: How does history come to matter in organisations? Management Decision, 40(6), 614–619. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740210434007

- Greenhalgh, T., & Russel, J. (2009). Evidence based policymaking: A critique. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 52(2), 304–318. https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.0.0085

- Grenni, S., Soini, K., & Horlings, L. G. (2020). The inner dimension of sustainability transformation: How sense of place and values can support sustainable place-shaping. Sustainability Science, 15(2), 411–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00743-3

- Hollander, A. (2013). Tegen beter weten in. De geschiedenis van de biologische landbouw en voeding in Nederland (1880-2001) [Doctoral dissertation, Utrecht University]. Utrecht University Repository. https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/240439

- Horlings, L. G. (2015). The inner dimension of sustainability: Personal and cultural values. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 14, 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2015.06.006

- Hulme, M. (2009). Why we disagree about climate change: Understanding controversy, inaction and opportunity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ives, C. D., Freeth, R., & Fischer, J. (2020). Inside-out sustainability: The neglect of inner worlds. Ambio, 49(1), 208–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-019-01187-w

- Janker, J., & Mann, S. (2020). Understanding the social dimension of sustainability in agriculture : A critical review of sustainability assessment tools. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 22(3), 1671–1691. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-018-0282-0

- Janker, J., Mann, S., & Rist, S. (2018). What is sustainable agriculture? Critical analysis of the international political discourse. Sustainability, 10(12), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10124707

- Janker, J., Mann, S., & Rist, S. (2019). Social sustainability in agriculture – A system-based framework. Journal of Rural Studies, 65, 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.12.010

- Jongeneel, R., & Gonzalez-Martinez, A. (2021). Climate change and agriculture: An integrated Dutch perspective. EuroChoices, 20(2), 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/1746-692X.12327

- Jukema, G., Ramaekers, P., & Berkhout, P. (2020). De Nederlandse agrarische sector in internationaal verband. Wageningen Economic Research en Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, Report 2020-001.

- Kuhlman, T., & Farrington, J. (2010). What is sustainability? Sustainability, 2(11), 3436–3448. https://doi.org/10.3390/su2113436

- Latruffe, L., Diazabakana, A., Bockstaller, C., Desjeux, Y., Finn, J., Kelly, E., Ryan, M., & Uthes, S. (2016). Measurement of sustainability in agriculture: A review of indicators. Studies in Agricultural Economics, 118(3), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.7896/j.1624

- Lejano, R. P. (2019). Relationality and social-ecological systems: Going beyond or behind sustainability and resilience. Sustainability, 11(10), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102760

- Littig, B., & Grießler, E. (2005). Social sustainability: A catchword between political pragmatism and social theory. International Journal of Sustainable Development, 8(1–2), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijsd.2005.007375

- Lune, H., & Berg, B. L. (2017). Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences (9th ed.). Pearson.

- Ly, A. M., & Cope, M. R. (2023). New conceptual model of social sustainability: Review from past concepts and ideas. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(7), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20075350

- Mandryk, M., Reidsma, P., Kartikasari, K., van Ittersum, M., & Arts, B. (2015). Institutional constraints for adaptive capacity to climate change in Flevoland’s agriculture. Environmental Science and Policy, 48, 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.01.001

- Manhoudt, A. (1998). Agrarisch natuurbeheer: Een overzicht van ontwikkelingen en knelpunten in bet beleid. Landbouwuniversiteit Wageningen. WUR eDepot. https://edepot.wur.nl/180467

- McCarthy, J., Meredith, D., & Bonnin, C. (2023). ‘You have to keep it going’: Relational values and social sustainability in upland agriculture. Sociologia Ruralis, 63(3), 588–610. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12402

- Ministerie van Cultuur, Recreatie en Maatschappelijk werk. (1975). Nota betreffende de relatie landbouw en natuur- en landschapsbehoud. Gemeenschappelijke uitgangspunten voor het beleid inzake de uit een oogpunt van natuur- en landschapsbehoud waardevolle agrarische cultuurlandschappen [memorandum]. Den Haag.

- Ministerie van Landbouw Natuurbeheer en Visserij. (1990a). Natuurbeleidsplan. Den Haag.

- Ministerie van Landbouw Natuurbeheer en Visserij. (1990b). Structuurnota Landbouw. Den Haag.

- Ministerie van Landbouw, Natuur en Voedselkwaliteit. (2018). Landbouw, Natuur en voedsel: Waardevol en verbonden. Nederland als koploper in kringlooplandbouw. Den Haag. https://open.overheid.nl/documenten/ronl-db1252eb-89e3-452c-9c2d-9fa9398e5dcc/pdf

- Muradian, R., & Pascual, U. (2018). A typology of elementary forms of human-nature relations: A contribution to the valuation debate. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 35, 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2018.10.014

- Naito, R., Zhao, J., & Chan, K. M. A. (2022). An integrative framework for transformative social change: A case in global wildlife trade. Sustainability Science, 17(1), 171–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-021-01081-z

- NOS.nl. (2023, June 2023). Landbouwakkoord lag voor het grijpen, waarom ging het toch mis? NOS. https://nos.nl/artikel/2479960-landbouwakkoord-lag-voor-het-grijpen-waarom-ging-het-toch-mis

- Parmentier-Cajaiba, A., & Cajaiba-Santana, G. (2020). Visual maps for process research: Displaying the invisible. Management, 23(4), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.37725/mgmt.v23i4.4501

- Paul, K. T. (2009). Food safety: A matter of taste? Food safety policy in England, Germany, the Netherlands, and at the Level of the European Union [Doctoral dissertation, University of Amsterdam]. UvA-DARE. https://hdl.handle.net/11245/1.310355

- Purvis, B., Mao, Y., & Robinson, D. (2019). Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustainability Science, 14(3), 681–695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0627-5

- Sachs, J. D. (2015). The age of sustainable development. Columbia University Press.

- Schoon, M., & Van Der Leeuw, S. (2015). The shift toward social-ecological systems perspectives: Insights into the human-nature relationship. Natures Sciences Societies, 23(2), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1051/nss/2015034

- Schwartz-Shea, P., & Yanow, D. (2014). Interpretive research design. Concepts and Processes. Routledge.

- Slätmo, E., Fischer, K., & Röös, E. (2017). The Framing of Sustainability in Sustainability Assessment Frameworks for Agriculture. Sociologia Ruralis, 57(3), 378–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12156

- Steinmo, S. (2003). The evolution of policy ideas: Tax policy in the 20th century. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 5(2), 206–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-856x.00104

- Stone, D. (2012). Policy paradox: The art of political decision making (3rd ed.). Norton & Company.

- Suddaby, R., Elsbach, K. D., Greenwood, R., Meyer, J. W., & Zilber, T. B. (2010). Organizations and their institutional environments – Bringing meaning, values, and culture back in. Introduction to the Special Research Forum. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6), 1234–1240. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2266086

- Swinkels, M. (2020). How ideas matter in public policy: A review of concepts, mechanisms, and methods. International Review of Public Policy, 2(3), 281–316. https://doi.org/10.4000/irpp.1343

- Trouw. (2023, June 21). Landbouwakkoord geklapt, verschillen tussen kabinet en boeren bleken onoverbrugbaar. Trouw. https://www.trouw.nl/duurzaamheid-economie/landbouwakkoord-geklapt-verschillen-tussen-kabinet-en-boeren-bleken-onoverbrugbaar~b34071ec/.

- Vallance, S., Perkins, H. C., & Dixon, J. E. (2011). What is social sustainability? A clarification of concepts. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 42(3), 342–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.01.002

- Van den Born, R. J. G., Arts, B., Admiraal, J., Beringer, A., Knights, P., Molinario, E., Horvat, K. P., Porras-Gomez, C., Smrekar, A., Soethe, N., Vivero-Pol, J. L., Ganzevoort, W., Bonaiuto, M., Knippenberg, L., & De Groot, W. T. (2018). The missing pillar: Eudemonic values in the justification of nature conservation. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 61(5–6), 841–856. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2017.1342612

- Van der Maas, D. (2014). Verleden boven water. Erfgoed, identiteit en binding in de IJsselmeerpolders [Doctoral dissertation, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam]. VU Research portal. https://hdl.handle.net/1871/53722

- Van Dissel, A. C. M. (1991). 59 jaar eigengereide doeners in Flevoland, Noordoostpolder en Wieringermeer. Walburg Pers.

- Van Eeten, M. J. G. (1999). ‘Dialogues of the deaf’ on science in policy controversies. Science and Public Policy, 26(3), 185–192. https://doi.org/10.3152/147154399781782491

- van Lieshout, M., Dewulf, A., Aarts, N., & Termeer, C. (2013). Framing scale increase in Dutch agricultural policy 1950–2012. NJAS – Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 64–65(1), 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2013.02.001

- Venema, G., & Verhoog, D. (2023). Inzichten in de omvang van het Agrocluster in de provincie Flevoland. Wageningen Economic Research, Report 2023-051. https://edepot.wur.nl/632059

- Vriend, E. (2022). Het nieuwe land. Atlas Contact.

- Wageningen University & Research. (2018, 18 september). Landbouwvisie Kabinet biedt wenkend perspectief voor circulaire en natuurinclusieve landbouw. Retrieved 29 September 2023, from https://www.wur.nl/nl/nieuws/Landbouwvisie-Kabinet-biedt-wenkend-perspectief-voor-circulaire-en-natuurinclusieve-landbouw-.htm

- Walker, B., Carpenter, S., Anderies, J., Abel, N., Cumming, G., Janssen, M., Lebel, L., Norberg, J., Peterson, G. D., & Pritchard, R. (2002). Resilience management in social-ecological systems: A working hypothesis for a participatory approach. Ecology and Society, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.5751/es-00356-060114

- Walsh, Z., Böhme, J., & Wamsler, C. (2021). Towards a relational paradigm in sustainability research, practice, and education. Ambio, 50(1), 74–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-020-01322-y

- WCED. (1987). Our Common Future: Report of the world commission on environment and development. United Nations General Assembly document A/42/427.

- West, S., Haider, L. J., Stålhammar, S., & Woroniecki, S. (2020). A relational turn for sustainability science? Relational thinking, leverage points and transformations. Ecosystems and People, 16(1), 304–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2020.1814417

- Zhu, L., & Oude Lansink, A. (2022). Dynamic sustainable productivity growth of Dutch dairy farming. PLoS ONE, 17(2), e0264410. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264410