1. Background

Overweight and obesity (O&O) are medical conditions, defined as abnormal or excessive body-fat accumulation. According to the world obesity atlas 2023 [Citation1], 988 million people representing 14% of the world population were obese in 2020 alone. Thereby, O&O are known as a major risk factor for health. The possible assumed or proven health consequences of O&O are manifold and cover among others the medical areas of cardiology, endocrinology, oncology, neurology, rheumatology, orthopedics, dermatology, or gastroenterology.

The direct and indirect costs associated with the disease burden resulting from O&O are tremendous. In a recent study, Okunogbe et al. [Citation2] estimated the costs attributable to O&O for 161 countries in 2019 and projected these costs up to 2060. The estimated total costs for the year 2019 were 1,879 billion US-$ corresponding to 2.19% of the global GDP. They occurred mostly in high-income countries (71%) and primarily as indirect costs (68%). Using current trends, Okunogbe et al. projected the share in global GDP to rise up to 3.29% in 2060. Unsurprisingly, O&O are popular research fields for cost-of-illness studies (COI). For example, in a recent systematic review, Kent et al. [Citation3] identified 75 COI that analyzed health care costs associated with O&O in primary study data, which represents a massive body of evidence on the costs of illness resulting from O&O.

2. Measures of overweight and obesity

To estimate the costs of O&O, a quantifiable definition of O&O is required first. The current standard used by the WHO and also most scientists is the ‘Body Mass Index’ or BMI, which is calculated from body height and weight. Overweight is defined as a BMI between 25 and 30 and obesity as a BMI larger than 30, albeit for Asian populations a BMI between 23 and 25 is suggested to define overweight and a BMI larger than 25 to define obesity. BMI is easy to assess, reliable and supported by a large body of literature. However, BMI is also criticized, for example for not strictly referring to body-fat. A very muscular person can be identified as obese as well, although having only little body-fat. Furthermore, BMI does not reflect the distribution of body-fat over the body. There is evidence that body-fat distribution also plays a separate role as risk factor for health [Citation4]. In particular, abdominal fat is considered to be associated with increased risk for morbidity and mortality [Citation5]. As a consequence, alternative measures like waist circumference (WC), waist-to-hip ratio (WTHip) or waist-to-height ratio (WTHeight) or combinations of these measures with BMI have been proposed. Also for the alternative measures cutoff values for Asian populations differ from those defined for Caucasians.

How relevant are these alternative measures? A quick PubMed-search (conducted on 28 February 2023) using ‘BMI,’ ‘waist circumference,’ ‘waist-to-hip’ and ‘waist-to-height’ as search terms revealed the following results: BMI 189,531 results (80.0%), waist circumference 37,439 results (15.8%), waist-to-hip 7,295 results (3.1%) and waist-to-height 2.751 results (1.2%). So 4 out of 5 studies were based on BMI. Regarding COI, BMI is even more prominent in defining O&O. Preparing this editorial, I conducted a brief literature-search in PubMed of COI for O&O for years following 2010 onwards, in which I could not identify even one COI using another measure than BMI to define O&O. I have not searched alternative databases, since COI are usually published in journals listed in PUBMED. But, even if there are publications not listed in PubMed, I would expect these publications to be such rare that results should not be systematically different.

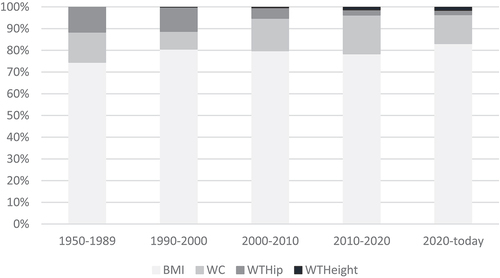

For the question asked in the title of the editorial, the development of the frequency distribution of the single measures over time is of course of more relevance than the distribution alone. shows the shares of different O&O measures from my quick PubMed-search for different periods since 1950. Interestingly, the share of results for ‘BMI’ remains almost constantly at about 80% although the total number of studies increased dramatically from 545 in the period 1950–1989 to 125,638 in the period 2010–2020. If at all, the share of BMI is minimally increasing over time. Only within the group of alternative measures, we can see changes over time. Whilst ‘waist circumference’ and ‘waist-to-hip’ can be found at almost equal shares in the period 1950–1989, the share of ‘waist circumference’ stands for more than 80% of all search results for alternative measures from 2010 until today.

Of course, one cannot precisely infer the relevance of BMI from just looking at the number of PubMed search results, in particular because quantity tells nothing about quality or content. But how often a measure is mentioned in a publication should be a roughly fair proxy for the use and application of a measure over time, in particular relative to other measures.

3. Measures of overweight and obesity in the 21st century

If one simply extrapolates the numbers from the last 70 years of research shown in to the rest of the 21st century, the question asked in the title of this editorial is very simple to answer: BMI will remain the primary measure to define O&O and hence it will remain the most relevant (if not only) measure used to conduct COI for O&O. And I personally think that there are some good arguments that this is indeed a realistic scenario.

The basis of this argumentation is the fact that – at least so far – the evidence for alternative measures does not show that they are clearly superior to BMI in general. Measures of O&O can be compared in different ways. One possibility is to analyze the diagnostic abilities to identify persons that are obese (as measured by a gold standard technique like imaging). For example, Sommer et al. [Citation6] conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis on the diagnostic performance of different tools to determine obesity and found no evidence that WTHip or WTHeight are superior to BMI or WC. Comparing the pooled estimates for BMI and WC, their findings indicated a slightly better (worse) sensitivity (specificity) of WC, but the difference was not striking. Another possibility to compare measures of O&O is to analyze the association with morbidity. For example, Lichtenauer et al. [Citation7] conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis on the association of BMI, WC and WTHeight with cardiovascular diseases in adults. They found that all measures were associated with different cardiovascular diseases, but it was not possible to judge the relative strength of measures based on the available evidence in the literature. These were only two examples of studies showing the difficulties to demonstrate clear superiority of alternative measures for O&O. Given this lack, BMI can easily play out its strengths.

First, there is a simple practical issue: BMI is very easy to assess. Ask yourself: Do you know your height? Do you know your weight? If you can answer both question with ‘yes,’ you can calculate your BMI. Now ask yourself: do you know your waist circumference? If your answer is ‘no,’ you cannot calculate any of the alternatives measures without additional measurement. Scientists of course should not just choose the easy way, but often enough they do – which favors BMI.

Second, there is a psychological element. It is known that humans have a natural preference for conformity. I suppose this also holds for many scientists – although it should not. So if alternative measures are not clearly superior to BMI and BMI is so easy to estimate, why not just use BMI as everybody else does likewise? One could speculate that this may be of particular relevance for ‘2nd line’ science like e.g. research on the costs of health effects of O&O (compared to e.g. research on the effects of O&O on health), which might explain why I was not able to find any COI using an alternative measure of O&O.

Third – and maybe most important – BMI can rely on massive network effects due to its dominance over the last decades. The body of evidence using BMI is such large and studies, reviews or even meta-analysis are available for so many research questions when using BMI, but not for the alternatives, that this body of knowledge is massively self-producing new research questions using BMI rather than the alternatives. The third argument also plays an important role in particular for top-down COI. Whilst bottom-up COI are empirical studies that can easily choose a preferred measure of O&O, the character of a top-down COI is that of a modeling approach that critically relies on the availability of data on O&O prevalence and relative risks for single diseases. This dependency exposes the use of BMI to a phenomenon called ‘technological log-in.’ Technological log-in describes a situation where the transition from a certain technology (BMI) to another technology (e.g. WTHip) comes with such high costs that the existing technology is maintained even if the new technology would be superior. If one would for example aim to use WTHip to estimate top-down costs of O&O, this scientist would need data on O&O prevalence and relative-risks for all relevant diseases using WTHip-categories. As long as these data are not available in a quality comparable to the data available when using BMI, top-down COI will most likely continue to be dominated by BMI. Moreover, as long as more research is conducted using BMI rather than alternatives (see , the relative advance of BMI will remain, even if the absolute evidence for alternative measures increases.

4. Expert opinion

Let me summarize. Despite legitimate critics, BMI is still the dominant measure to quantify O&O and so far the only relevant measure used to define O&O in COI. Following the arguments stated above, it seems unlikely that this will change in the near future. In order to switch over to an alternative measure of O&O, much more evidence showing clear advantages of this measure would be necessary. For this purpose, the scientific community should consent about the criteria to define superiority of one measure about another. In my opinion, the association with health outcomes should be of primary importance. So far, studies analyzing associations of O&O with health outcomes often refer to mortality, but in my opinion, it would be desirable to shift this focus to morbidity to address clinical relevance for the living. However, it might turn out that although different measures show good psychometric properties to predict mortality or morbidity, the differences between measures are only marginal – or least too small to be clinically relevant and statistically significant. A possible way to strengthen the evidence for alternative measures might be to measure and report multiple measures of O&O in COI and other publications, e.g. on O&O as risk factor for morbidity.

Of course, evidence as well as preferences of scientists can change rapidly, but given where we stand now, I suppose that BMI will – with a high probability – remain the dominant criterion for COI of O&O in the 21st century.

Declaration of interest

The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Obesity Federation. World Obesity Atlas 2023. https://dataworldobesityorg/publications/?cat=19.

- Okunogbe A, Nugent R, Spencer G, et al. Economic impacts of overweight and obesity: current and future estimates for 161 countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7(9):e009773. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-009773

- Kent S, Fusco F, Gray A, et al. Body mass index and healthcare costs: a systematic literature review of individual participant data studies. Obes Rev. 2017;18(8):869–879. doi: 10.1111/obr.12560

- Britton KA, Massaro JM, Murabito JM, et al. Body fat distribution, incident cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all-cause mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(10):921–925. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.06.027

- Kuk JL, Katzmarzyk PT, Nichaman MZ, et al. Visceral fat is an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in men. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14(2):336–341. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.43

- Sommer I, Teufer B, Szelag M, et al. The performance of anthropometric tools to determine obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):12699. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-69498-7

- Lichtenauer M, Wheatley SD, Martyn-St James M, et al. Efficacy of anthropometric measures for identifying cardiovascular disease risk in adolescents: review and meta-analysis. Minerva Pediatr. 2018;70(4):371–382. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4946.18.05175-7