ABSTRACT

Background

Educational escape games have become more common, yet their effectiveness needs to be evaluated to establish whether or not they are a constructive pedagogical tool.

Aim

This study explored students’ experiences of a general practice (GP) based escape game to uncover whether it deserves a place in a medical school’s curriculum.

Design and Setting

A mixed methods case study within one Scottish Medical School.

Method

Data were collected during March 2020 via 32 video recordings of an Escape Room Game, combined with participant, post-game questionnaire analysis. Video footage was reviewed in an ethnographic manner and thematic analysis conducted.

Results

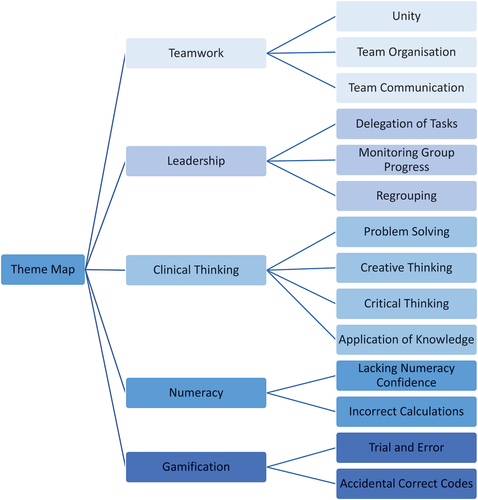

Fourteen team events constituting 718 minutes were analysed. From the footage, five themes with fourteen subthemes emerged. The five main themes were: teamwork, leadership, clinical thinking, numeracy, and gamification. From the student questionnaires (n = 131), it was reported that the GP escape room was predominantly an extremely positive educational experience.

Conclusion

Educational escape games appear invaluable in medical education. They can promote the growth of non-technical skills such as teamwork, leadership, and clinical thinking; all essential to working in a multidisciplinary team and enabling patient safety. Our participants struggled with numeracy in this high-pressured environment, this must be addressed to reduce potential mistakes made in the workplace. Results are supportive of educational escape games being worthy of a space within a medical school's curriculum. A GP-orientated escape room allows for early GP exposure from a different perspective, as well as equipping students with the skills to be successful in this field.

Introduction

This paper focuses on the experiences of medical students participating in an educational escape room set within a General Practice (GP) environment. The aim of the study was to determine whether educational escape rooms can serve as effective learning tools and deserve inclusion in a medical school curriculum. Escape rooms are interactive group activities where participants work together to solve puzzles and complete tasks within a set time frame, usually with the goal of escaping from the room [Citation1]. Current evidence suggests that this collaborative and enjoyable learning exercise can effectively teach and reinforce medical knowledge while developing essential non-technical skills required in healthcare [Citation2,Citation3].

The general practice speciality is increasingly struggling to attract doctors. Since 2005 the number of medical students primarily selecting this discipline, post-medical school, has been consistently decreasing [Citation4]. Possible factors contributing to this decline include the high pressures associated with the role, inadequate mentorship, limited research opportunities, and a relatively lower reputation compared to other medical specialities [Citation5]. Research shows that early exposure to GP during a student’s academic career significantly influences their decision to pursue the speciality [Citation4]. Therefore, our study becomes crucial in providing junior medical students with a different perspective on GP while developing essential skills required in the medical profession.

The evolving nature of education demands adaptable teaching methodologies, particularly in the medical field, where imparting important skills alongside foundational knowledge is vital [Citation2,Citation6]. The lack of these necessary abilities has been shown to have a negative impact on the working environment [Citation7]. Healthcare professionals are required to possess both clinical and non-clinical skills, with this research emphasising the importance of non-clinical skills such as teamwork and leadership [Citation8,Citation9]. Unlike teaching knowledge, which can be acquired through traditional methods, these skills are best learned through hands on practice. Thus, our study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of an educational escape room in developing these abilities and determining the game as suitable for inclusion in our medical school curriculum environment [Citation7].

Escape rooms with an educational focus are relatively new but increasingly popular teaching tools. The distinguishing feature of these rooms is that participants must achieve specific learning outcomes to succeed [Citation1]. The introduction of a GP escape room at the University of Dundee School of Medicine was a novel and unique experience for both students and tutors. In March 2020, during curriculum review opportunities, the piloting of this gamification [Citation10] process became possible. The primary research question being addressed was, what are the experiences of a GP Escape Game amongst second-year medical students at the University of Dundee?

Method

Design

Mixed methodology positioned this research as a type-2 case study [Citation11] of one singular context, that of Dundee Medical School, drawing on one cohort of year two medical students. To place this in context, Dundee Medical School and its curriculum normally follows a five-year degree with the first three years being predominantly pre-clinical, followed by the latter two years of clinical placements [Citation12]. This research seeks to align with mixed-methods reporting guidelines [Citation13].

Data collection

There were two embedded units of analysis [Citation11], namely: quantitative data gathered using participant questionnaires (Appendix 1) completed after the escape room experience, together with video ethnographic analysis [Citation14]. The participants enrolled in this case study were second-year medical students from the University of Dundee. The GP Escape Game was incorporated within the second-year curriculum during a Clinical Application of Scientific Principles (CLASP) week, focused on the GP speciality. A typical year group at the University of Dundee School of Medicine holds 150 students [Citation15]. However, due to absences, only 131 students participated in the study.

The research was developed aligning with guidelines set out via the University of Dundee Information Governance [Citation16], the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [Citation17], and the British Educational Research Association’s Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research [Citation18]. Before engaging in the GP escape game, students were provided with a participant information sheet. Within this document, it was made evident that the GP escape game experience would usually involve audio and video recordings, retained for research purposes. After familiarising themselves with the information students were invited to complete an informed consent form to participate. If students did not consent to the video and audio recordings, they were still able to take part in the game but the live video feed into the room was not recorded. The audio and video recordings are securely stored on cloud enabled University approved software named Yuja [Citation19].

GP escape room schema

The year group (n = 150) was divided into 32 teams ranging from 3 to 5 students. Each group would individually enter the GP escape room, which had been organised to resemble a ‘typical’ consultation room (see ). Further photos of the room can be viewed in Appendix 2.

The aim of the exercise was for the group to ‘escape’ from the room, by finding both a GP locum payment cheque and the key to open the door, within the allocated time, which begins once the facilitator locks the door behind the group. A poem (Appendix 3) is situated on the desk: within it clues were hidden that led to two separate pathways i.e. a dual, sequential pathways approach [Citation20]. One pathway was to find the key to unlock the door and the other to find the cheque. Both pathways contained riddles and patient cases (Appendix 4) that the group needed to solve to create codes. These codes could unlock padlocks situated in numerous locations around the room. Each padlock opened, presented more tasks and patient cases until eventually a cheque and the key to the door are found.

A camera was situated on the desk to record the room’s audio and video activities. A facilitator observed using the camera present and could contact the group, or vice-versa, to provide help by phone if needed. To complete the game the group must successfully unlock the door and escape the room with a cheque in hand. If the group are unsuccessful within the time frame the facilitator would enter the room to end the experience. The normal time limit applied was 60 minutes with a subsequent group debriefing and feedback.

Analysis

Data were primarily collected through observations via the form of video ethnography which is qualitative in nature [Citation21]. The recorded footage was transcribed, this presented some challenges [Citation22]. The presence of numerous individuals in the footage frequently resulted in multiple individuals speaking at once; more than one conversation often took place at the same time. Some individuals were found to be soft spoken which created difficulties in itself. The only way to address these complications were to watch and re-watch the footage, thus creating an in-depth immersion in the data [Citation21].

Supplementary to the video ethnography, quantitative data was gathered using participant questionnaires completed post escape room experience (Appendix 1). These questionnaires evaluated the teaching process, were anonymous, and contained no demographic details. The questionnaires provide insight into the participants’ estimations on the GP escape room learning experience and thus is a form of triangulation – the use of numerous techniques to gather data which in turn improves the validity of results [Citation23]. When a study involves transcripts, as this one does, it is beneficial for the participants to check the transcripts ensuring they are accurate [Citation24]. This was an aspect that was considered, however, due to time constraints and the sheer volume of participants in this study, participant checking was unfeasible.

From the observations of the audio and video recordings, codes were generated adopting a reflexive analytical approach [Citation25]. This process continued until data power was said to occur [Citation26], i.e. when no new information was gathered from the research, instead common themes frequently reappeared [Citation27]. Both researchers strived to adopt a reflexive stance throughout [Citation28]. One researcher (KM) was the primary facilitator of the majority of the escape room sessions including the pre- and post- participant briefings. The quantitative data was composed of ratings on a five-point Likert scale from very poor to excellent. Free text comments from sections 7–9 of the questionnaire (Appendix 1) provided supplementary triangulation to the thematic analysis.

Results

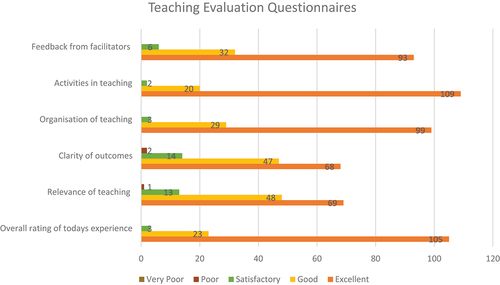

After observing fourteen teams’ attempts, totalling 718 minutes at the GP escape game, data power was satisfied [Citation26]. Questionnaires were completed by the 131 students, post escape room experience, evaluating several components of the delivered teaching. There were six areas the students were asked to rate on a five-point Likert scale from very poor to excellent. Collated results are shown in . Free text comments from sections 7–9 of the questionnaire provided supplementary triangulation to the thematic analysis.

Within these questionnaires, the students were also asked three questions which they could answer in their own words. When asked: ‘What were the most useful aspects of today’s teaching?’ 57 students answered it was a good form of revision, 51 students wrote teamwork, and 29 reported it was a fun way of learning. Further answers written include leadership (n = 2), working under pressure (n = 10), problem-solving (n = 10), application of knowledge (n = 5), communication (n = 3), and abstract thinking (n = 2).

When asked: ‘What were the least useful aspects of today’s teaching?’ the most common answer was that the patient cases were not relevant to their specific year group. However, it must be stated that only 7 out of the 131 students that took part said this. The final question asked: ‘What, if anything, would you change to improve today’s teaching?’. The leading answer was more time to tackle the escape room.

As displayed within , five themes emerged (teamwork, leadership, clinical thinking, numeracy, and gamification) each composed of sub-themes. Additional quotations, supporting the findings can be found in the online supplementary material where G=Group and p=Participant within that group.

Teamwork

Given the GP escape room was a team game, teamwork emerged as an evident theme, witnessed within every group’s attempt. The way in which the team interacted greatly influenced the group’s overall success. There were three predominant ways teamwork was displayed: unity, team organisation, and communication.

Unity between a team was demonstrated for example when participants used ‘we’, instead of ‘I’:

We’ve got a key! We’ve got a key!

G6/P4

From observations made, it was apparent that the most successful groups were well organised. Due to the content, the dual, sequential pathways, and the time constraints of the game, it appeared advantageous for the team to divide further, tackling both pathways simultaneously. Group organisation and division was recurrently observed and discussed:

So shall we split ourselves up into two groups then because they said there will be two pathways.

G12/P1

Additionally, teamwork was portrayed by the way in which a team communicated with one another. The following quote shows a student explaining matters to their peers, sharing their knowledge:

P4 ‘Look what we’ve got to do, one plus two, so five plus 13 times 17. No BODMAS needed’.

P1 ‘What’s BODMAS?’

P4 ‘It’s like when you’re doing the multiplication before you do the adding. Just do it in the order it’s given it to you’.

G7/P1&P4

Leadership

Alongside teamwork, components of leadership frequently appeared within the GP escape game. Despite the experience being a group effort, there were often occasions where certain individuals assumed a leadership role. Leadership was demonstrated by delegating tasks, monitoring group progression, and regrouping to evaluate the group’s endeavours.

In delegating tasks non-verbal communication included assigning team members to a portion of the room. In the discussions, a leading individual would allot tasks and effectively communicate with their group, uniting them towards attaining their shared goal:

Do you want to read through that and I’ll do this.

G6/P3

Alongside delegation, features of leadership were found by individuals monitoring their group’s progression. In several poignant example of leadership, individuals would conscientiously check in on their fellow teammate:

… how you getting on with those cases?

G6/P3

Additionally, leaders were found to motivate their team, encouraging the group to work to the best of their capabilities:

Guys we’re so close!

G8/P4

The GP escape game may be viewed as a challenging experience. As a group attempts to embark down a pathway, there are several opportunities for errors to be made. For this reason, it was important to reassess the situation and evaluate how and what they were doing. Thus, regrouping was viewed as representing a form of leadership:

Guys can we reconvene and think about what is going on?

G7/P5

Clinical thinking

The escape game was designed to imitate a clinical environment. Within this setting, the students were required to apply their knowledge and skill sets. Consequently, clinical thinking was a recurrent theme and appeared as: problem-solving, creative thinking, critical thinking, and the application of knowledge.

There was an abundance of problems within the escape room, resulting in problem solving emerging as a prominent theme. The first problem met was to identify the two pathways, one to find the key and the other to find the cheque, as displayed below:

So do you think it’s two separate lots of clues? One’s for the key and one for the cheque?

G9/P2

Individuals were found to be resourceful with their problem solving. Within the escape room, the team must distinguish between the available resources to identify what could be used to their advantage:

Oban, right where’s Oban? Oh, wait there’s a big map over here.

G8/P1

For each individual puzzle there may be several approaches for solving the conundrum, thus some individual creativity could be profitable. For example, there was an anagram of the word ‘CENTOR’ with one student’s intuitive approach to write the letters in a circle to aid in unravelling the anagram:

It’s better if you draw it in a circle, so then it gives your brain more time to look at it.

G1/P4

Additionally, following escape room gamification, there could be multiple misleading clues (distractors). A recurring example of a student’s critical thinking was to attempt to identify if a clue is real or fake:

P4 ‘We’ve got another key’.

P1 ‘It might be a fake one. It might be one, one of these ones to put you off’.

G8/P1&P4

As participants progressed through the pathways, there was a requirement to apply their clinical knowledge on a wide variety of topics. For example, the participants must understand how to treat asthma, read electrocardiograms (ECG), and select the correct laboratory bottles:

Oh wait well it says he’s using the inhaler correctly albeit five to six times daily so it must be salbutamol because you can’t use steroids five to six times a day.

G9/P2

P2 ‘Later on seek out Wood’s light to illuminate the truth’.

P4 ‘Okay Wood’s light that’s … for fungal skin infection’.

G10/P2&P4

Numeracy

Throughout the escape game the participants had to use mental arithmetic to create codes. The puzzles created required simple addition and multiplication, yet numeracy difficulties arose as a recurring theme.

The participants were all second-year medical students; therefore, they have proven themselves to be intelligent individuals with verified numeracy skills. Despite this, it was observed that many lacked confidence in their ability with maths:

So then we need to do 11 times 12 plus 9. I don’t know what 11 times 12 is.

G2/P3

Blue is 11, 44 by 11, I can’t do this anymore, how do you do this?

G4/P3

Alongside lacking confidence with mental arithmetic, many individuals provided incorrect solutions for the calculations:

P1 ‘So it’s 11 times 12 times 4 I think’.

P4 ‘12 times 4 is 36’.

G7/P1&P4

Gamification

The application of a game within an unusual context resulted in gamification appearing as a novel theme. Elements of gamification appeared when participants would attempt to guess the code combinations and when teams obtained correct code combinations from incorrect solutions.

It was noted that some participants would try to guess code combinations. Through trial and error, the participants could complete the game without meeting all of the intended learning outcomes:

Try 5, 0 but we’re not 100% about the last one, so we’ll just fiddle with it and see if you get it.

G7/P2

Alongside trial and error, some participants were found to form working codes from incorrect answers. As an example, one group managed to successfully get the code without attaining the correct patient diagnosis, which was a myocardial infarction (MI):

Okay apparently it was an MI. Haha we got it anyway we got it anyway.

G1/P4

Discussion

Summary

This study aimed to explore the experiences of second-year medical students at the University of Dundee participating in a General Practice (GP) Escape Game. Employing a case study methodology, observations were recorded through audio and video recordings of student groups engaging with the escape room, followed by video ethnography for analysis. Utilising Braun and Clarke’s [Citation25,Citation26] analytical processes, five themes emerged, emphasising the development of non-technical skills such as teamwork, leadership, and clinical thinking essential for effective healthcare practice. Additionally, quantitative data from student feedback questionnaires supplemented the findings, albeit tangential to the primary research question.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is in the contemporaneous explorations of medical student’s perceptions of escape room games, specific to the context of GP. Students have found this an enjoyable yet challenging experience. Gamification has led to opportunities to merge leadership with team working and clinical thinking. The trustworthiness of this data and its transferability to other GP educational environments has been considered from the outset, as well as the position of the researchers [Citation27–29].

One notable limitation encountered during the transcription process was the presence of simultaneous conversations, posing difficulties in capturing all content accurately despite extensive review of the footage. The study’s sample size represents another consideration [Citation30] as a limited number of observed groups may have restricted the breadth of findings. However, with 14 teams’ attempts observed, data power was achieved, enhancing the robustness of the study’s outcomes [Citation27].

Comparison with existing literature

The results highlighted the GP escape room as an effective educational tool, facilitating the practice of crucial non-technical skills vital for patient safety and professional success, aligning with previous literature emphasising the significance of these skills in healthcare settings [Citation2,Citation6]. Notably, the identification of numeracy challenges among participants underscores the importance of addressing this competency, crucial for accurate clinical decision-making, particularly in drug dosage calculations [Citation31].

Despite its gamified nature, the escape room experience proved to be highly enjoyable and beneficial, suggesting its potential integration into the medical school curriculum to enhance student preparedness and interest in general practice [Citation3]. This immersive learning experience could serve as a catalyst for fostering early exposure and interest in GP among medical students, offering a unique perspective and equipping them with essential skills for future success in healthcare practice.

Implications for research and practice

Further exploration in the realm of educational escape games, especially within medicine, holds significant promise [Citation1]. Future research avenues could involve assessing the experiences of senior medical students, such as those in their final year, with the GP escape game, potentially serving as a gauge for their medical competence and preparedness for graduation. Additionally, considering the suggestion in literature that escape games could serve as alternatives to traditional OSCE exams, investigations into their appropriateness as assessment tools could be fruitful. Exploring inter-professional dynamics by involving both medical and nursing students in escape game sessions could provide valuable insights. Moreover, given the unexpected challenges with numeracy skills, there is potential for research to delve into medical students’ numeracy proficiency, especially in high-pressure clinical environments. The breadth of research possibilities underscores the versatility and relevance of educational escape games in medical education.

With respect to future practice this study marks the initial stride in elucidating the role of educational escape games in the University of Dundee’s medical school, yielding promising results that advocate for the permanent integration of a GP escape game into the second-year curriculum. Additionally, there exists potential for broadening the utilisation of educational escape games across various year groups and thematic areas. Beyond medical education, the application of escape games could extend to interprofessional teaching scenarios, fostering stronger collaborative relationships between medical and nursing students that may translate into the professional realm.

Considering the research findings, it is evident that escape games hold potential for promoting ongoing learning and collaboration throughout a doctor’s career, serving as valuable tools for both revision and continual professional development.

Ethical approval

The University of Dundee – School of Medicine – SMED REC − 20/29.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (34 KB)Acknowledgments

Thanks are provided to the participants who contributed their time.

Disclosure statement

The educational concept was originally designed and implemented by KMcC. CW was supervised by KMcC to perform the analysis as part of a BMSc in Medical Education.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/14739879.2024.2364885

Additional information

Funding

References

- Veldkamp A, van de Grint L, M-CPJ K, et al. Escape education: a systematic review on escape rooms in education. Educ Res Rev. 2020 [cited 2024 1st March]31:100364. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100364

- Guckian J, Sridhar A, Meggitt SJ. Exploring the perspectives of dermatology undergraduates with an escape room game. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020;45(2):153–158. doi: 10.1111/ced.14039

- Guckian J, Eveson L, May H. The great escape? The rise of the escape room in medical education. Future Healthcare J. 2020;7(2):112–115. doi: 10.7861/fhj.2020-0032

- Marchand C, Peckham S. Addressing the crisis of GP recruitment and retention: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2017;67(657):e227–e237. doi: 10.3399/bjgp17X689929

- Barber S, Brettell R, Perera-Salazar R, et al. UK medical students’ attitudes towards their future careers and general practice: a cross-sectional survey and qualitative analysis of an oxford cohort. BMC Med Educ. [2018 Jul 4];18(1):160. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1197-z

- Rosenkrantz O, Jensen TW, Sarmasoglu S, et al. Priming healthcare students on the importance of non-technical skills in healthcare: how to setup a medical escape room game experience. Med Teach. [2019 Jul 23];11:1–8.

- Prozesky DR. Communication and effective teaching. Community eye health/International Centre for Eye Health. Community Eye Health. 2000;13(35):44–45.

- Gourbault LJ, Hopley EL, Finch F, et al. Non-technical skills for medical students: Validating the tools of the trade. Cureus. 2022 May;14(5):e24776. doi: 10.7759/cureus.24776

- Gordon LJ, Rees CE, Ker JS, et al. Leadership and followership in the healthcare workplace: exploring medical trainees’ experiences through narrative inquiry. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e008898. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008898

- Landers RN. Developing a theory of gamified learning: linking serious games and gamification of learning. Simulation & Gaming. 2014;45(6):752–768. doi: 10.1177/1046878114563660

- Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods. 5th ed. USA: Sage Publications; 2014.

- University of Dundee. Medicine MBChB. 2023 Available from: https://www.dundee.ac.uk/undergraduate/medicine

- O’Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. The quality of mixed methods studies in health services research. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2008 Apr;13(2):92–98. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2007.007074

- Elsey C, Challinor A, Monrouxe LV. Patients embodied and as-a-body within bedside teaching encounters: a video ethnographic study. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2017 [2017 03 1];22(1):123–146. doi: 10.1007/s10459-016-9688-3

- Davis MH. OSCE: the Dundee experience. Med Teach. 2003 May;25(3):255–261. doi: 10.1080/0142159031000100292

- University of Dundee. Information governance 2019 [ Available from: https://www.dundee.ac.uk/research/governance-policy/

- Of Dundee U. University of Dundee data protection policy. 2018 Available from: https://www.dundee.ac.uk/information-governance/data-protection

- British educational research association. Ethical guidelines for educational research. 2018 Available from: https://www.bera.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/BERA-Ethical-Guidelines-for-Educational-Research_4thEdn_2018.pdf

- Yuja. Yuja enterprise video platform 2019 Available from: https://www.yuja.com/

- Connelly L, Burbach BE, Kennedy C, et al. Escape room recruitment event: description and lessons learned. J Nurs Educ. [2018 Mar 1];57(3):184–187. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20180221-12

- Urquhart LM, Rees CE, Ker JS. Making sense of feedback experiences: a multi-school study of medical students’ narratives. Med Educ. 2014 Feb;48(2):189–203. doi: 10.1111/medu.12304

- Witcher CSG. Negotiating transcription as a relative insider: implications for rigor. Int J Qual Methods. 2010;9(2):122–132. doi: 10.1177/160940691000900201

- Heale R, Forbes D. Understanding triangulation in research. Evidence Based Nurs. 2013;16(4):98–98. doi: 10.1136/eb-2013-101494

- Hagens V, Dobrow MJ, Chafe R. Interviewee transcript review: Assessing the impact on qualitative research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009 [ cited 47 p.9(1):]. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-47

- Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis: a practical guide. 1st ed. Thousand Oak (CA): Sage; 2022.

- Braun V, Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research In Sport, Exercise And Health. 2021 [ cited 201-216 p.13(2):201–216. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

- Varpio L, Ajjawi R, Monrouxe LV, et al. Shedding the cobra effect: problematising thematic emergence, triangulation, saturation and member checking. Med Educ. 2017 Jan;51(1):40–50. doi: 10.1111/medu.13124

- Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research In Sport, Exercise And Health. 2019 [2019 08 8];11(4):589–597. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Korstjens I, Moser A. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pract. [2017 Dec 5];24(1):120–124. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375092

- Ross PT, Zaidi NLB. Limited by our limitations. Perspect Med Educ. 2019;8(4):261–264. doi: 10.1007/S40037-019-00530-X

- Williams B, Davis S. Maths anxiety and medication dosage calculation errors: a scoping review. Nurse Educ Pract. 2016;20:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2016.08.005