ABSTRACT

Background

Introducing medical students to the concept of Cultural Humility, we devised a teaching initiative for students to consider how power manifests through the use of language in clinical communication, with a focus on General Practice. Cultural Humility is a pedagogical framework, introduced by Tervalon and Murray-Garcia, to address what they consider as the limitations of the Cultural Competence model.

Approach

Our teaching initiative specifically focused on power in clinical communication, both oral consultations and written notes. The session was delivered to third-year medical students during their first ‘clinical’ year, where they regularly witness and are involved in clinical communication across primary and secondary care placements. Ethical approval was in place to analyse students’ reflections on the session.

Evaluation

Students who attended engaged well. They evaluated the session positively as increasing their awareness of the power of clinical language in negatively stereotyping and dehumanising patients. They demonstrated Cultural Humility in their reflections of the unintentional harm of clinical language commonly used for the doctor–patient relationship. However, most striking for us, and where our learning as educators lies, was the low attendance at the session, despite our attempts to underline clinical relevance and importance for development as future doctors.

Implications

This article offers a framework for educators interested in Cultural Humility. The implications of this initiative are how (or how not) to develop and deliver training in this space. More consideration is required as educators, including around our own language, as to how to engage students to think around the complex topic of power.

Background

Health profession educators strive to create curricula which reflect the increasing diversity of populations and support students to approach patients in an open and holistic manner. Educators have drawn on well-known models such as Cultural Competence [Citation1], to help students develop their cultural knowledge, skills and attitudes to care for patients from diverse backgrounds. Critiques of the Cultural Competence model have emerged over time. These include the concern that the focus in Cultural Competence becomes about ‘Culture’ in a static way that downplays the link with social justice or equality [Citation2,Citation3]. In addition, there is a critique around describing it as a ‘competency’, about having adequate knowledge or skills merely to tick off learning outcomes, as an end point [Citation3]. Cultural Humility is an alternative pedagogical framework, introduced by Tervalon and Murray-Garcia [Citation4], aiming to address perceived limitations of the Cultural Competence model. They envision Cultural Humility as ‘a process that requires humility as individuals continually engage in self-reflection and self-critique as lifelong learners and reflective practitioners. It is a process that requires humility in how physicians bring into check the power imbalances that exist in the dynamics of physician-patient communication by using patient-focused interviewing and care. And it is a process that requires humility to develop and maintain mutually respectful partnerships with communities on behalf of individual patients in the context of community-based clinical and advocacy training models’. (p. 118). Tervalon and Murray-Garcia describe the four components of the Cultural Humility model which include ‘Self-reflection and the Lifelong Learner Model’ and ‘Patient-focused interviewing and care’. Their focus on power imbalances and on the model as a lifelong learning process help address some of the concerns around Cultural Competence.

Within the authorship of this article, we as practising general practitioners (GPs) and sociologist were interested in designing an initiative to introduce medical students to Cultural Humility. Through our experience as clinicians and educators, we chose to focus on ‘Patient-focused interviewing and care’. Tervalon and Murray-Garcia describe the tenets of this aspect of Cultural Humility as being less authoritative and more enabling for patients as they decide what role if any culture plays in what they want to discuss [Citation4]. As they advocate for a specific focus on language with the patient as the expert, we chose to address power imbalances in the doctor–patient relationship, by reflecting on power through the use of language in clinical relationships. To do so, we draw on Foucault’s [Citation5] definition of power as existing between people ‘rooted in the system of social networks’, where communication is a means of acting upon another person. In this article, we reflect on our experiences as educators and our reflective analysis around what we learned through the process. We discuss our surprise at the lack of uptake of our initiative by students; how it failed and why this might have been the case. We provide some suggestions for educators willing to address the important but uncomfortable concept of power with students.

Approach

The intended learning outcomes for this initiative centred on the power of language in clinical communication with the intention of empowering students to question norms in communication. In planning this initiative, our first surprise was the lack of published material reporting educational initiatives that explicitly addressed power with students. Perhaps, we should have considered this an early warning of entering difficult territory. We drew on an article by Cox and Fritz [Citation6] titled, ‘Presenting complaint: use of language that disempowers patients’, to devise the initiative, focusing on language as a vehicle to discuss power. Cox and Fritz suggest how commonly used phrases in both oral and written communication can result in language that 1) belittles patients, e.g. patient denies chest pain, 2) language that emphasises patients as passive or childlike, e.g. sending patients home and 3) language that blames patients, e.g. poorly controlled diabetic [Citation5]. To emphasise these points in clinical contexts within our initiative, we created a mock GP consultation and a hospital ‘clerk in’. Our teaching initiative was targeted at Year Three medical students within our institution, where students participate in clinical placements in both general practice and hospital settings. While our practice orientation is very much general practice, we deliberately chose to mirror examples that our learners may have encountered across the breadth of their placements. During our (45 min) session, we tasked students with identifying and feeding back examples of language that could belittle, blame or portray patients as passive.

is the script of a mock consultation between a GP and a patient, following receipt of a blood result which indicates that the patient has a high cholesterol level. The doctor begins by asking the patient what their complaint is, as an example of belittling language. The doctor explains their intention to ‘take a history off you’, before going on to suggest that there is food the patient is not allowed and tutting at the end of consultation, all examples of language in use which puts the patient in a passive position. Finally, considering the language that blames, the doctor suggests that patients should use their money to instead buy healthy food.

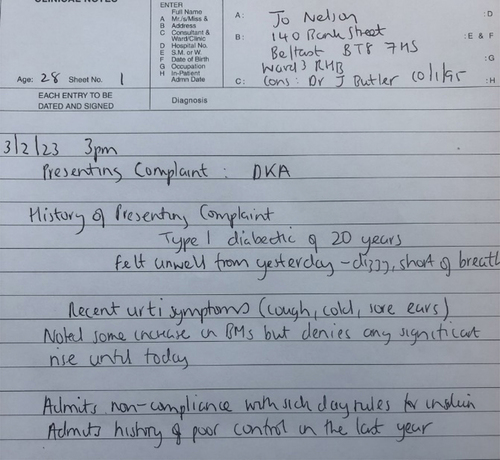

is the mock hospital clerk-in for a patient admitted with the emergency condition Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA). We simulated how a doctor writing the clerk-in uses the convention of HPC (history of presenting complaint) and talks of how the patient ‘denies’ certain symptoms, both evidence of belittling language. With regard to passive language, the doctor writes how the patient admits non-compliance with insulin, with additional blaming language such as how their diabetic control is poor.

During the plenary of the initiative, we brought together the observations the students made on these mock clinical encounters, encouraging them to reflect on these as examples of the power that a clinician holds in clinical communication with patients, both written and oral. At the end of the session, we drew on the table of suggested changes in terminology within the article, to arm students with alternatives to try in their clinical communication [Citation5]. The initiative was delivered online (as per the module plan) on a voluntary basis for Year Three medical students, in their first ‘clinical’ year, where they regularly witness and are involved in clinical communication. As stated above, whilst the intended learning outcomes centred on the power of language in clinical communication with the intention of empowering students to question norms in communication, what we consider below highlights some of the unintended outcomes of the session.

Evaluation

Around 300, third-year students were invited to this teaching initiative live online. Our evaluation of the initiative was a (voluntary) feedback form, beginning with student demographics and asking for qualitative thoughts on the initiative, what surprised them about it and what they would do differently on clinical placement as a result of their engagement.

Surprisingly to us, only around 15 attended live (although others are likely to have watched the recorded version at a later point). Students who attended engaged well, readily identifying potentially problematic language and were willing to share their thoughts on it. A small number of students (four) filled in the voluntary feedback form, reflecting positively on the session. Half of these students identified as male and half female, three were aged 21 suggesting they were undergraduates and one 26, suggesting they were postgraduate. Their qualitative feedback was encouraging, detailing the importance of the topic and its relevance to patient-centred care. One reflected, ‘I think being conscious of the language we use is incredibly important … Encouraging staff to reflect on their language choices allows us to challenge the connotations or perceptions associated with turns of phrase that are common both in medicine and in everyday conversation’. When asked about what surprised them in the session, they reflected on, ‘how often language may be unintentionally hurtful to patients’, committing in the future to be more careful with ‘the language I use, both written and verbal’. The views and commitments of these interested students reflected their increasing awareness of the unintentional harm choice of language can cause, professional development very much consistent with the Cultural Humility ethos.

However, as educators, the unintended learning for us in developing and running this initiative was how it failed in terms of very low uptake. Whilst we recognise the enthusiasm of the students who attended and contributed, the fact that only around 5% of the year group chose to attend synchronously is perturbing. We reflect that our focus during the initiative to promote the clinical relevance and importance for professional development (something that in our experience usually guarantees good attendance) had not worked. Students did not choose to attend despite our experience of students requesting teaching which is culturally sensitive. We recognise that other factors will have contributed to this, not least the virtual delivery of potentially challenging material. The fact that the session was recorded afforded other students the opportunity to watch asynchronously. A precedent for asynchronous engagement had been established throughout much of the Year Three ‘whole year group’ teaching around various topics. This may have inhibited student willingness to engage with the real-time session. We also reflected that perhaps this session was timed too early in our curriculum, around six months into clinical placements. Students may perhaps only become aware of the power at play once they feel more comfortable with the more ‘clinical’ aspects of consultations. We surmise that our ‘power failure’ in developing this initiative lay in our assumption that students would inherently appreciate how ubiquitous power is in clinical workplaces and why a focus on power is crucial as they develop as doctors. Might it be the case that for students, such uncomfortable and potentially dangerous discussions were simply avoided? The small proportion of students who chose to attend was arguably already those with a burgeoning awareness of the power of power. Medical students have so much to learn that they inevitably focus on what will be assessed. Our ‘power-driven’ framing of the session might have seemed minimally relevant to assessment-oriented students.

Implications

Our intention was to develop a session to help students engage with and reflect on power dynamics and how they play out when healthcare professionals interact with patients, both in oral and written communication. However, what we reflect on as educators and what we feel is useful for us to share with others interested in developing similar initiatives, is that we have more preliminary, formative work to do with students before many are in a position to understand what power dynamics are, their implications, and what they might look like in clinical practice. We also have work to do in how we frame and promote such initiatives. Whilst some self-selected students appeared to see power as important and indeed engaged well in the session, many of the intended audience, probably for a variety of reasons, chose not to attend. Reflecting on assessment-oriented learning, perhaps embedding our initiative or others like it in clinical communication teaching (as opposed to a standalone session) might have been more successful.

In this article, we offer a framework for those interested in teaching around power, as something currently lacking in health profession education literature. The additional learning in this initiative for those interested in further developing teaching which aligns with Cultural Humility, and what we plan to do differently in subsequent iterations, is to consider how to engage students in thinking around the topic of power and in how to maximise their attendance at sessions concerning it. Turning the Cultural Humility lens on ourselves, we must reflect on the language we used to promote this initiative and the clinical application. Perhaps, students were exerting their own power by not attending. We advocate for fellow health profession educators to learn from our power failure. We encourage colleagues to grasp the earth wire in other uncomfortable aspects of educating for person centred and Culturally Humble health professionals. We cannot assume students’ understanding of the relevance of power and its complexities or indeed their comfort or discomfort with it. As educators, we must consider how best to frame and situate teaching around challenging topics such as power.

Ethical approval

The Medicine, Health and Life Sciences Research Ethics Committee of Queen’s University Belfast approved this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the students who took part in the initiative and those who filled in the evaluation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Cross TL, Bazron BJ, Denis KW, et al. Towards a culturally competent system of care: a monograph on effective services for minority children who are severely emotionally disturbed. (WA); 1989. [accessed 2023 November 14]. https://spu.edu/-/media/academics/school-of-education/Cultural-Diversity/Towards-a-Culturally-Competent-System-of-Care-Abridged.ashx

- Kumagai AK, Lypson ML. Beyond cultural competence: critical consciousness, social justice, and multicultural education. Acad Med. 2009 June;84(6):782–787. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a42398

- Wear D. Insurgent multiculturalism: rethinking how and why we teach culture in medical education. Acad Med. 2003;78(6):549–554. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200306000-00002

- Tervalon M, Murray-García J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998;9(2):117–125. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0233

- Foucault M. Afterword: the subject and power. In: Dreyfus H Rainbow P, editors. Michel Foucault: beyond structuralism and hermeneutics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1982. p. 208–226.

- Cox C, Fritz Z. Presenting complaint: use of language that disempowers patients. Brit Med J. 2022;377:e066720. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-066720