ABSTRACT

Social movement scholars often want their research to make a difference beyond the academy. Readers will either read reports directly or they will read reviews that aggregate findings across a number of reports. In either case, readers must find reports to be credible before they will take their findings seriously. While it is not possible to predict the indicators of credibility used by individual, direct readers, formal systems of review do explicate indicators that determine whether a report will be recognized as credible for review. One such indicator, also relevant to pre-publication peer review, is methodological transparency: the extent to which readers are able to detect how research was done and why that made sense. This paper tests published primary research articles on and for social movements in Latin America for compliance with a generous interpretation of methodological transparency. We find that, for the most part, articles are not methodologically transparent. If transparency matters to social movement scholars, the research community may wish to formalize discussions of what aspects of research should be reported and how those reports should be structured.

Academics have engaged in research on and with social movements, often to support those movements’ objectives, for at least a generation (e.g. Gutierrez & Lipman, Citation2016; Smith, Citation1990). These scholars have discussed a number of methodological challenges such as those attending the use of memoirs as data (Marche, Citation2015); the effect of engagement on critical reflexivity (e.g. Petray, Citation2012); and the impact of analytic conveniences, such as the naturalization of the individual as the unit of analysis, on researchers’ ability to detect and discuss mechanisms of oppression (Fine, Citation1989). The implications of deliberate academic activism for research ethics, as manifest for example in community-based participatory research, are well discussed (e.g. Cordner, Ciplet, Brown, & Morello-Frosch, Citation2012). Stepping back a bit, the universities we constitute have been argued, themselves, to be functional to the structural inequalities that attract engaged scholarship (Meyerhoff & Thompsett, Citation2017), and all representations made by outsiders may be found to be inescapably violent as such truth making is necessarily extractive (Luchies, Citation2015). These discussions have produced a number of recommendations for practice such as those found in militant ethnography (Apoifis, Citation2017).

While a great deal has been contributed to discussions surrounding primary research, we have found far less on the review of studies of social movements. Review, which determines both publication and reuse, treats the reports of studies as primary data. Serious readers will look beyond conclusions and check if a report is transparent: does it contain a discussion adequate to allow a reader to understand how research was undertaken and why it makes sense? For this essay we decided to borrow expectations of transparency that are used within systematic review as adapted for low-consensus qualitative inquiry. While systematic review sits at the pinnacle of the well-critiqued hierarchy of knowledge, and its adoption in the social sciences carries traces of an unfortunate scientism (Bannister, Citation1987; Hayek, Citation1942), the features it looks for in reports are relevant as they are consistent with the requirements for meaningful review by peers and for careful integration into the plans of donors, of non-governmental organizations of governments and other scholars. In addition, adaptations of systematic review are increasingly common in the social sciences and its use is encouraged in the study of social movements (e.g. McAdam, Tarrow, & Tilly, Citation2001) so the expectations of systematic review may increasingly determine whose voices are recognized.

Transparency, as operationalized in this essay, is not the same thing as methodological quality. The formal quality assessment tools used to examine qualitative research, some analogue of which we hope informs both peer review and use of findings in supporting decision making, tend to mix transparency with tests of internal coherence and quality (e.g. those suggested by Carroll, Booth, & Lloyd-Jones, Citation2012; Dixon-Woods et al., Citation2006; Dixon-Woods, Shaw, Agarwal, & Smith, Citation2004; Fossey, Harvey, McDermott, & Davidson, Citation2002; Kmet, Lee, & Cook, Citation2004; Pawson, Boaz, Grayson, Long, & Barnes, Citation2003; Spencer, Ritchie, Lewis, & Dillon, Citation2003; Tong, Flemming, McInnes, Oliver, & Craig, Citation2012). For our study we only asked if published reports are transparent.

Consistent with the expectations of reviewers in the social sciences, in our study transparency begins with the ability to find in a report of primary research ‘…sufficient detail of the research question, design, and methods to allow an assessment’ (Popay & Williams, Citation1998:35). Carlsen and Glenton (Citation2011) state that ‘transparency and accountability are key elements in any research report, not least in qualitative studies. Thorough reporting of methods allows readers to assess the quality and relevance of research findings’ (p. 1). Seale (Citation1999) called this auditing and, expressing a sentiment that acknowledges the complexities of qualitative research, notes that researchers should provide ‘a methodologically self-critical account of how the research was done’ (p. 468). Similarly acknowledging the reality of qualitative field work, Tracy (Citation2010) states that ‘transparent research is marked by disclosure of the study’s challenges and unexpected twists and turns and revelation of the ways research foci transformed over time’ (p. 842).

In the next sections, we present methods and results of a systematic review of transparency in a corpus of articles reporting on empirical inquiries with respect to social movements in Latin America. We provide a concise discussion of our assessment of transparency of these research reports, followed by some conclusions and recommendations for future reporting. The full study with its underlying data are, of course, available for review.

Methods

Sampling

Our study examined research conducted in Latin America. This thematic focus was determined entirely by the interest of the first author: he wished to understand how research is done so that he could do better research. While we have no reason to anticipate significant differences, we did not test if the transparency of reports of research on social movements in Latin America differs from those undertaken in other regions. We retrieved accessible English and Spanish articles reporting primary research on, and at times with, Latin American social movements through a search executed in ISI Web of Science. presents the search syntax as it was inserted, with no time limit set, on 16 January 2013, in ISI Web of Science.Footnote1 This search string returned all articles in English or Spanish in the social sciences on social movements in Latin America from at least 1975 to the present. We chose to search ISI indexed journals as our expectation was this would bias our sample towards more transparent reporting of methodological details. The search syntax identified 549 related articles of which 510 were English and 39 were Spanish.

Table 1. Search syntax.

We then examined the titles, abstracts and keywords of the articles identified in our search. We retained articles for further study when they met all of the following conditions:

1. Articles had to be available through the Wageningen University Library.

2. Articles needed to be on social movement(s) located in Latin America, yet not exclusively as articles that made a comparison of a movement in a Latin American country with one in another continent where also included. A definition of ‘social movement’ was not pre-defined. An article could, for example, be included when ‘urban movement’, ‘peasant movement’ or ‘student movement’ appeared in the keywords, abstract or title.

3. Articles needed to report primary social science research.Footnote2

4. Articles needed to be written in the English or Spanish language.

A total 219 articles passed the initial screen based on abstract, keywords, and title. Articles were then imported in random order into Atlas.ti and every tenth was gathered into the first batch and subjected to complete analysis. In order to reduce the possibility of order effects, reports were examined in parallel: the first question was asked of all reports before proceeding to the second question. Once the first batch was completed we then pulled and examined the second batch of articles. The time allotted for analysis permitted us to examine a total of 64 articles. traces what happened to these articles during the review.

Measuring transparency

In this study transparency begins with the ability to find in a report of primary research ‘sufficient detail of the research question, design, and methods to allow an assessment’ (Popay & Williams, Citation1998:35) which is appropriate, as argued by Carlsen and Glenton (Citation2011). We operationalized transparency as presence and structure.

Presence

A transparent article supplies a description of the research process sufficient to allow readers to understand what the researcher did. In this review a transparent article is one that supplies all of the following:

1. A clear indication of what the article is about archetypically (but not necessarily) expressed as one or more central research questions

2. Any mention at all of how data was actually gathered, as this is required for the reader to make contextually appropriate judgments regarding the suitability of the quality and types of data.

3. Some discussion of sampling, since readers need to be able to understand the logic behind and limitations of sampling with respect to the research question. If the author noted, for example, that they ‘talked to movement leaders’ that would not be recognized in this study as adequate, but the addition of any justification for that selection (e.g. their knowledge) or mechanism for selection (e.g. peer referral) would trigger recognition as explicit mention of the sampling process.

4. Any mention of a sample size, or a number of individuals who provided information, for each data collection method, whether statistically or theoretically justified, as sample sizes are one factor that determines both data quality and generalizability of findings. For this essay, a paper was recognized as having adequate mention of sample size even when the author did not provide any justification.

5. Mention, and ideally some description, of the analysis methods used, as analysis methods certainly inform how results should be interpreted. In this essay mere mention of, for example, ‘grounded theory’ would be recognized as explicit mention of an analysis method.

6. One or more conclusions, since empirical research should report something.

7. An account of limitations, as readers need to understand what may have shaped results. For this review, discussion of limitations could either be any mention of (1) instrument effects such as consideration of how the identity of the researcher may alter responses, or (2) concern that readers not make inferences based on a fallacy, e.g., ecological fallacy (making conclusions about individuals based on study of groups), atomistic fallacy (assuming that individual causal relations predict group) (Diez Roux, Citation2002), reverse ecological fallacy (making conclusions about a group based on study of an individual) (Hofstede, Citation2002), and so on.

shows the operationalization of the seven aspects of transparency just mentioned.

Table 2. Indicators for transparency of research report.

Structure

In addition to containing relevant information, an article should structure presentation of this information in a manner that allows a reader to make appropriate distinctions and links in order to, for example, identify the extent to which findings arise from theory rather than evidence. We decided that it was not appropriate to set standards in advance as ‘the absence of a standard format for reporting qualitative research makes it difficult for even the methodologically sophisticated reader to assess the validity of a qualitative study’ (Knafl & Howard, Citation1984, p. 17). These variations make detection of standard data across studies more time consuming than in quantitative inquiry where norms, such as distinctions between results and discussion, are more standardized (Sandelowski & Barroso, Citation2003). That said, interpretation of a single article requires reliable and valid detection of all relevant data in that article and the ability to see inter-relationships between these data. In examining structure we followed the framework suggested by Spencer et al. who argued that articles should have a ‘structure and signposting that usefully guide the reader through the commentary’ (Citation2003, p. 14). A ‘useful guide’ was further operationalized as the ability to detect (transparency) and to distinguish between process (i.e. theory, method, and data), findings and implications.

In order to test for structure, we coded for discrete presence, threading, and sequence. Discrete presence was operationalized as the proportion of a document (POD), a percentage of body text, dedicated to the discussion of the research question, methods, conclusions, and implications. We coded proportions simply for purposes of identification and comparison of attention given to different aspects of the research process in its report. As we found in our initial review that discussion of methods may be scattered through an article, we identified and concatenated all discontinuous fragments. Threading was operationalized as the ability to link individual questions through research methods to conclusions. As we will discuss in more detail below, a decision with respect to threading was deferred as that decision requires prior identification of research questions, data collection methods, and conclusions. Sequence was operationalized as the first shown locations of research questions, data collection methods, and conclusions. Again, a standard was not set for a specific sequence, yet it was seen as a rough indication of importance given to three components of transparency.

As the reviewed articles reported primary empirical research, our expectation was that some portion of the articles would be dedicated to methods, that it would be possible to see links between questions, methods and conclusions and, finally, that the logical sequence of question-methods-conclusion would predominate. As such, and remembering that we were working with rather relaxed operationalisations of terms like ‘research question’, for our purposes a well-structured article met the following criteria:

1. The body text contains at least one research question, one data collection method, and one conclusion (e.g. badly structured articles have data collection methods supplied in footnotes, research questions supplied in abstracts or no research questions at all).

2. The research question(s), data collection method(s) and conclusion(s) are clearly linked (e.g. a specific piece of reported data is relevant to both a specific research question and an identifiable conclusion that, in turn, answers its respective research question).

3. Theory is distinguishable from data, data from results, results from conclusions, and conclusions from implications (if any were discussed). This allows for the ability to see whether conclusions were based on the empirical data collected.

An article was categorized as unstructured if it failed to satisfy criteria two and three. It was categorized as moderately structured if it failed to meet the third criterion. Structured articles would satisfy all three criteria.

Instruments

We converted operationalisations of both transparency and structure into a form for assessing transparency and structure (FATS) that was tested on a subset, improved, and then applied to all sampled reports of primary research on Latin American social movements. The form was developed in a survey format that included categorization on an article level (e.g., ‘structuredness’; unstructured, moderately structured, structured) and on the level of individual research questions, data collection methods, conclusions, and limitations (e.g., ‘type of data collection method’; unstructured or structured interviews, participant or non-participant observation, document review, unclear).

During development of our data extraction form, we found that analytically relevant information often appeared only in footnotes and, as such, we decided to extend data extraction to footnotes. In addition, we have attempted to include other criteria in FATS, such as the unit of analysis and level of analysis, that are perhaps more relevant to the area of social movement research (Klandermans & Staggenborg, Citation2002, p. xv).

During development we encountered serious problems with inter-rater reliability when we tried to use binary coding. In these cases, we either created a ‘loose’ interpretation or we dropped the attempt to code entirely. The code ‘research question’ exemplifies our use of ‘loose’ interpretations. During instrument development we could not find a binary structure that would reliably code statements such as ‘this article opens with a summary of the historical antecedents to the San Marcos–Condebamba Valley mobilization, before proceeding to analyze the movement’s strategy and tactics, internal organization, the problems activists encountered and moves made to surmount these’ (Taylor, Citation2011). In this case, the text of the author could plausibly be re-written as ‘what are the historical antecedents reported to…?’ and ‘what were the movement’s strategy and tactics…?’ In order to accommodate the many instances where we found it possible to infer from the text the data we were trying to recognize (in this case a research question), we created an intermediate ‘loose’ interpretation whose express purpose was to allow us to code as present any indication that the topic to be coded for was considered by the researchers. In choosing to make such inferences we traded the problem of researchers’ subjective understanding of appropriate reporting formats for our own subjective understanding of their reports. In this case we decided that it was appropriate to do our utmost to recognize a report as adequate as it was not reasonable to assume that the authors of these reports have internalized narrow operationalisations of transparency formed within an entirely different research community.

Measurement

All of the articles in each batch of ten were first coded for ‘proportion of document’. Second, all the identifiable research questions were coded. Third, all the identifiable data collection-, sampling-, and analysis methods were coded. Fourth, all the identifiable conclusions and limitations were coded. Finally, the study design and the degree of structuredness was coded on an article level. When FATS was applied to all ten articles, the next ten articles were selected. The data was exported from Atlas.ti into SPSS for descriptive analyses.

Findings

Description of reviewed articles

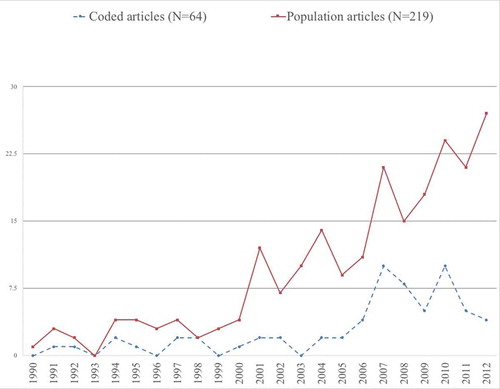

Following academic publication trends, primary research publications on social movements in Latin America increased significantly throughout the last decade, as depicted in .

Articles to which the complete data extraction form was applied appeared in a total of 40 journals. Of these 64 articles, 3 were in Spanish. Most reviewed papers were published in Latin American Perspectives (8 of 64). The reviewed articles had a mean of 0.54 citations per year (with standard deviation 0.60). With regards to the research designs used; almost three-quarters of the articles (47 of 64) used a case study design; almost a quarter of the articles used a cross-sectional design (15 of 64), and two articles used a longitudinal design.

Transparency

summarizes findings with respect to transparency.

provides an overview of the number of the seven aspects of transparency that could be found in each article reviewed. This figure presents two readings of transparency. The first ‘reliable’ reading requires text in the reviewed article whose clarity supports reliable identification (i.e. counts the total number of ‘clear’ and ‘present’ indicators). The second ‘charitable’ reading required considerable inference on the part of the reviewer and, as such, makes generous assumptions with respect to the research done to accommodate, perhaps, variations in the culture of reporting.

Structure

Three articles were well structured and hence met all three criteria in our operationalization of structuredness. Two-thirds of the articles (42 of 64) were unstructured, that is, it was impossible to detect and link research questions with data collection methods and conclusions. In almost half of the articles (30 of 64), it was not possible to detect the influence of the empirical data gathered on the conclusion reached. Almost one-third of the articles (19 of 64) were moderately structured. Data collection methods were presented in footnotes in about a quarter (13 of 64) of the articles. In almost half of the articles (29 of 64) less than 1% of the body text relates to the methods used (data collection plus sampling plus analysis).

Discussion

Over the last generation, social movements have figured prominently in a number of Latin American debates concerned with social and economic development. Social movement research that underpins these debates is a growing, heterogeneous, interdisciplinary field that has brought about cross-fertilization of scholars from numerous disciplines (Della Porta, Citation2014; Klandermans & Staggenborg, Citation2002). This field of research has ‘favored the development of methodological pluralism’ (Della Porta, Citation2014, p. 1), or as Klandermans and Staggenborg put it, there is an ‘absence of methodological dogmatism’ (Citation2002, p. xii).

In each of the past three decades, elaborate methodological introductions and updates on social movement research have appeared (Della Porta, Citation2014; Diani & Eyerman, Citation1992; Klandermans & Staggenborg, Citation2002). At the same time, there continues to be some degree of lamenting that few broader discussions exist of research methods beyond specific ones (Della Porta, Citation2014; Klandermans & Staggenborg, Citation2002).

Each of these debates requires that reports of research on social movements are transparent. From the perspective of expectations now institutionalized within the social sciences, the articles on Latin American social movement included in this review were rarely transparent and less frequently structured. Even allowing loose identification of key components, only three of the 64 articles reviewed provided the information that a serious reader would require for even minimal interpretation and inconsistencies within the sample examined would undermine structured aggregation.

Conclusion

The articles we randomly drew from research on social movements in Latin America are, for the most part, not methodologically interpretable. As such, careful examination of methods cannot be what informs peer review nor can it be what guides their recognition in decision support. Further, it is not clear that this research, whose declared purpose is often to support social movements, will be included in more systematic reviews of evidence as one consistent feature of these reviews is that their authors examine methods.

Implications

If authors of research on social movements want their perspectives to support a methodological reading, then the community may wish to formalize discussions around what aspects of research should to be reported and how those reports should be structured. The objective, here, would not be to generate any version of the quality assessment checklists derided by qualitative researchers. Rather, the purpose would be to encourage careful discussion of reporting adequacy to support forms of review that are deliberately constituted to fit the characteristics of social movement studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sven Da Silva

Sven da Silva is a PhD student at Wageningen University. He specializes in the pertinence of a variety of social and political theories on the topic of how global transformations are experienced in people’s livelihoods in the Latin American region.

Peter A. Tamás

Peter Tamás supports researchers’ development and testing of methods for qualitative fieldwork and analysis and he is testing the extent to which it is possible to extend the principles underlying systematic review to interdisciplinary studies of the socio-ecological systems implicated in climate change.

Jarl K. Kampen

Jarl Kampen earned his Phd in the Social Sciences by writing a thesis on ‘The analysis and interpretation of models for ordinal association’. During the past fifteen years he continuously engaged in fundamental and applied research in a variety of research settings (both academic and non-academic), and specialised in the field of general research methodology with a predilection for multidisciplinary research settings.

Notes

2. This was one of the reasons to conduct the search within ISI Web of Science. In contrast to for example Scopus, ISI offers the possibility to search in the Social Science Index.

References

- Apoifis, N. (2017). Fieldwork in a furnace: Anarchists, anti-authoritarians and militant ethnography. Qualitative Research, 17(1), 3–19.

- Bannister, R. C. (1987). Sociology and scientism: The American quest for objectivity, 1880–1940. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Carlsen, B., & Glenton, C. (2011). What about N? A methodological study of sample-size reporting in focus group studies. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11, 26.

- Carroll, C., Booth, A., & Lloyd-Jones, M. (2012). Should we exclude inadequately reported studies from qualitative systematic reviews? an evaluation of sensitivity analyses in two case study reviews. Qualitative Health Research, 22(10), 1425–1434.

- Cordner, A., Ciplet, D., Brown, P., & Morello-Frosch, R. (2012). Reflexive research ethics for environmental health and justice: Academics and movement building. Social Movement Studies, 11(2), 161–176.

- Della Porta, D. (2014). Methodological practices in social movement research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Diani, M., & Eyerman, R. (1992). Studying collective action. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Diez Roux, A. V. (2002). A glossary for multilevel analysis. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 56(8), 588–594.

- Dixon-Woods, M., Cavers, D., Agarwal, S., Annandale, E., Arthur, A., Harvey, J., … Smith, L. (2006). Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 6(35), 1–13.

- Dixon-Woods, M., Shaw, R. L., Agarwal, S., & Smith, J. A. (2004). The problem of appraising qualitative research. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 13(3), 223–225.

- Fine, M. (1989). The politics of research and activism: Violence against women. Gender & Society, 3(4), 549–558.

- Fossey, E., Harvey, C., McDermott, F., & Davidson, L. (2002). Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36(6), 717–732.

- Gutierrez, R. R., & Lipman, P. (2016). Toward social movement activist research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 29(10), 1241–1254.

- Hayek, F. A. (1942). Scientism and the study of society. Part I. Economica, 9(35), 267–291.

- Hofstede, G. (2002). The pitfalls of cross‐national survey research: A reply to the article by Spector et al. on the psychometric properties of the Hofstede values survey module 1994. Applied Psychology, 51(1), 170–173.

- Klandermans, B., & Staggenborg, S. (2002). Methods of social movement research (Vol. 16). Minneapolis: University Of Minnesota Press.

- Kmet, L. M., Lee, R. C., & Cook, L. S. (2004). Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields: Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research.

- Knafl, K. A., & Howard, M. J. (1984). Interpreting and reporting qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 7(1), 17–24.

- Luchies, T. (2015). Towards an insurrectionary power/knowledge: Movement-relevance, anti-oppression, prefiguration. Social Movement Studies, 14(5), 523–538.

- Marche, G. (2015). Memoirs of gay militancy: A methodological challenge. Social Movement Studies, 14(3), 270–290.

- McAdam, D., Tarrow, S., & Tilly, C. (2001). Dynamics of contention. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Meyerhoff, E., & Thompsett, F. (2017). Decolonizing study: Free universities in more-than-humanist accompliceships with Indigenous movements. The Journal of Environmental Education, 48(4), 234–247.

- Pawson, R., Boaz, A., Grayson, L., Long, A., & Barnes, C. (2003). Types and quality of knowledge in social care. Social Care Institute for Excellence.

- Petray, T. L. (2012). A walk in the park: Political emotions and ethnographic vacillation in activist research. Qualitative Research, 12(5), 554–564.

- Popay, J., & Williams, G. (1998). Qualitative research and evidence-based healthcare. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 91(35), 32–37.

- Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2003). Classifying the findings in qualitative studies. Qualitative Health Research, 13(7), 905–923.

- Seale, C. (1999). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 5(4), 465–478.

- Smith, G. W. (1990). Political activist as ethnographer. Social Problems, 37(4), 629–648.

- Spencer, L., Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., & Dillon, L. (2003). Quality in qualitative evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence. Government Chief Social Researcher’s Office, London: Cabinet Office.

- Taylor, L. (2011). Environmentalism and social protest: The contemporary anti-mining mobilization in the province of San Marcos and the Condebamba valley, Peru. Journal of Agrarian Change, 11(3), 420–439.

- Tong, A., Flemming, K., McInnes, E., Oliver, S., & Craig, J. (2012). Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12(181), 1–8.

- Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851.