ABSTRACT

Studying the nexus of media and social movements is a growing subfield in both media and social movement studies. Although there is an increasing number of studies that criticize the overemphasis of the importance of media technologies for social movements, questions of non-use, technology push-back and media refusal as explicit political practice have received comparatively little attention. The article charts a typology of digital disconnection as political practice and site of struggle bringing emerging literatures on disconnection, i.e. forms of media technology non-use to the field of social movement studies and studies of civic engagement. Based on a theoretical matrix combining questions of power, collectivity and temporality, we distinguish between digital disconnection as repression, digital disconnection as resistance and digital disconnection as performance and life-style politics. The article discusses the three types of digital disconnection using current examples of protest and social movements that engage with practices of disconnection.

Abbreviations: AFA: Anti-Fascist Action; CHRI: Center for Human Rights in Iran; DDoS: Distributed Denial of Service

Sociologists of speed, such as Wajcman (Citation2015) and Rosa (Citation2013), emphasize that societies have been speeding up on different levels, ranging from the individual experience of hurried lives to the increased pace of social change and technological innovation. In this context, there have emerged both a trend towards practices of slowing down and a theoretical engagement with questions of disconnection from accelerated capitalism carving out alternative spaces and new forms of political engagement. Particularly, discussions of disconnection in the digital age are thriving to explain forms of resistance and push-backs against fast-paced, always-on digital societies (for an overview see Hesselberth, Citation2018). These studies suggest that disconnection can be conceptualized as tactics to navigate the current and increasingly complex digital media ecology (Light, Citation2014), as discourses or gestures towards disconnectivity that reinforce ideas of connectivity rather than providing alternatives (Hesselberth, Citation2018), or as a form of resistance against the temporality of fast capitalism (Barranquero, Citation2013; Pink, Citation2008). Especially the latter way of discussing disconnection as a form of resistance implicates that we should consider the politics of disconnection and hence why and how it matters for social movements.

Though the field of disconnection studies is fluid and constantly extended including studies on emerging industries capitalizing on the need to disconnect for health reasons (Fish, Citation2017; Kuntsman & Miyake, Citation2017; Sutton, Citation2017), there is currently no systematic conceptualization of the implications of disconnection for political practices and social movements. There are, however, important exceptions, including Portwood-Stacer’s (Citation2013) discussion of non-use of Facebook as an expression of lifestyle politics, and Casemajor et al.’s (Citation2015) theoretical conceptualization of non-participation and the analysis of abstinence across different contexts including abstinence from technology use (Mullaney, Citation2006). Disconnection as a form of political practice is however nothing new. There have been earlier, pre-digital forms of mobilization to disconnect. Drotner (Citation1999) discusses moral panics connected to new formats or media technologies. She reflects for example on mobilizations against vulgar literature in Britain of the 18th century. Similarly, film was perceived as a vulgar intruder and contaminator of the public sphere and different philanthropic groups started to campaign against further diffusion of cinema (Drotner, Citation1999). Syvertsen (Citation2017) reviews media refusal since the inception of modern mass media in the late 19th century until digital media today. Hence, rather than emphasizing the newness of push-back and media refusal as activism, we consider non-use and disconnection as pre-dating the digital age. This article extends these ongoing discussions by bringing studies of disconnection to the field of social movement studies to examine the implications and politics of disconnection for social movements with the aim of building a typology of disconnection as political practice.

There is a pressing need to establish a connection between these traditions, especially considering that contemporary research on digital activism has disproportionately centered on hyper-connected movements and their multiple uses of digital technologies. In general, current literature focusing on the dynamics between social movements and digital media has been concerned in explaining how activists are using digital media (Bennett & Segerberg, Citation2013; Earl & Kimport, Citation2011), while almost no attention has been devoted to scrutinizing how contemporary activists are deliberately choosing to disconnect from certain platforms, forging alternatives to the imperative of ubiquitous connectivity. The neglect of disconnection and non-participation in contemporary networked activism has had two main implications (Casemajor, Couture, Delfin, Goerzen, & Delfanti, Citation2015). First, it has drawn the attention of scholars to exploring more specifically the practices of social movements that are actively using digital technologies, neglecting contemporary movements that are less connected and less technologically innovative (but not necessarily less relevant). Second, many scholars have tended to take for granted the digital connectedness of contemporary movements, adopting new methodologies that rely on harvesting massive quantities of data from social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter. However, as Croeser and Highfield (Citation2015) have shown, one of the weaknesses of this kind of methodologies is that it obscures the negotiations and the tactical avoidance of social media by activists. In other words, studies on social movements and the media tend to focus on examining the digital traces and the patterns of those who are connected, but cannot tell us much on the choices, negotiations and tactics of those who decide to avoid, refuse and withdraw from digital connection.

The article – conceptual in its outline – provides an overview of current studies of disconnection, media refusal, push-back activism and media non-use. It brings these literatures in conversation with insights from social movements studies to discuss the political potential and consequences of digital disconnection and activism. More specifically, we develop a three-dimensional matrix of political practices including power, level of collectivity and temporality. Based on the matrix, we discuss three types of digital disconnection as political practice; namely disconnection as repression, disconnection as resistance and disconnection as lifestyle politics. We focus on digital disconnection that includes the refusal of social media, but moves beyond this side of media rejection to also include other digital platforms, tools and services. The article illustrates the three types with current empirical examples and conclude with a discussion of the relevance of disconnection and activism in the current digital media ecology and in the context of a dominant focus on hyper-connected social movements. In that context, it casts digital disconnection as a site of struggle, where resistance to connection is considered both as a political tactic by activists and their adversaries, as well as the goal around which activists and their adversaries organize and campaign.

Disconnection studies

While the field of non-usage research is still relatively nascent, there is a growing number of projects investigating specific aspects of disconnecting from media technologies. Within this emerging field of disconnection studies, several related terms are currently used to describe similar though slightly different practices. Hesselberth (Citation2018) suggests distinguishing between technology non-use, media resistance and media disruption. Media non-use is more closely related to the field of audience and reception studies and emerged in the context of studying media technology use (Hesselberth, Citation2018). Media non-use describes ‘individuals who intentionally and significantly limit their media use’ (Woodstock, Citation2014, p. 1983). While media refusal, media resistance and push-back in contrast include ‘negative actions and attitudes towards media [and] describe[s] a refusal to accept the way media operate and evolve’ (Syvertsen, Citation2017, p. 9). This form of refusal has collective components and goes beyond media non-use on the individual level. Media disruption discourses focus in contrast on strategies to shake-up hegemonic conceptualizations of media ecologies (Hesselberth, Citation2018).

Previous research can furthermore be divided in two major categories based on the degree of agency that actors encompass. The first category of research focuses on involuntary non-usage, i.e. cases when individuals may want to use a technology but out of social, economic or infrastructural reasons are excluded from access, for example research on digital divide (Selwyn, Citation2003). Here attention is drawn to broader social, cultural, historical, and political aspects of technology non-use, especially outside of the North American and European contexts. Another way to examine involuntary non-usage is to highlight the relationship between individual agency and power structures within society. In particular governmental and corporate interests that in many aspects determine the degree of use and non-use are examined. Non-use of technology may simply be impossible due to the transition into a technology-based society. For instance, Ribak and Rosenthal (Citation2015) consider smartphone resistance as an ongoing struggle between commercial strategies and resistance tactics, asking how long it is possible to resist considering the pressure to be available to the state and to the market. Hence, Ribak and Rosenthal engage with non-use stressing the ambivalence of voluntary and involuntary aspects of the possibility to choose to not use a certain technology.

The second category examines non-usage as a voluntary or intended avoidance of technology. Individual agency is thus emphasized. In the context of addiction, for example, worries about overuse are at the forefront. Media refusal becomes the ability to resist the temptation of using technology and regain self-control. Media resistance might also be seen as a deliberate political act, for example when non-use of social media manifests a form of political asceticism against the all-encompassing dominance of network culture (Karppi, Citation2011). Mejias (Citation2013) engages in Off the Network with strategies of disrupting the dominance of the idea of networked societies. The reasons for and practices of media resistance are manifold and deeply ingrained with everyday life (Woodstock, Citation2014). In contrast, Portwood-Stacer (Citation2013) discusses the political practice of leaving Facebook while Brubaker, Ananny, and Crawford (Citation2016) analyze the experience and personal consequences of suspending Grindr accounts – a popular dating platform. Considering disconnection with social networking sites (SNS), Light (Citation2014) slightly changes the angle and asks how forms of disconnection and non-use sustain the overall presence in and of commercial social media on the micro level. Strömbäck, Djerf-Pierre, and Shehata (Citation2013) focus instead exclusively on the non-usage of certain content, namely news content by specific social groups. Syvertsen (Citation2017) discusses similar practices of media refusal, skepticism, abstention and resistance, while providing a historical contextualization of media resistance as an everyday phenomenon (for a distinction between media resisters and media rejectors see Wyatt, Graham, & Terranova, Citation2002). Sutton (Citation2017) and Fish (Citation2017) examine disconnection in the form of digital detox camps advocating digital health and digital fasting to counter the perils of the fast paced always-on digital economy.

Another stream of studies engaging with voluntary disconnection considers forms of ‘old’ media usage. Skågeby (Citation2011) for example explores fast and slow music formats comparing tape cassettes with playlists. Thorén and Kitzmann (Citation2015) study forms of non-use and technology resistance by considering vintage and software instruments users in comparison. Both studies emphasize nostalgic aspects that are connected with the decision to reject certain technological innovations. Providing an extended reading of disconnection studies, Hesselberth (Citation2018) identifies problems both in commercial and academic discourses on disconnectivity. They reinforce the hegemony of being connected in information-based capitalism rather than establish fundamental alternatives, which she calls structuring paradox of discourses on disconnectivity.

A slightly different stream of research within media studies is inspired by design and media/technology theory. These studies show a growing interest in technological disconnect in form of glitches and technological failure that make certain media regimes visible (Krapp, Citation2011). Looking at technological glitches is here presented as an inspiration to imagine alternative designs and artistic expressions that allow for creative innovation within the digital cultural industry. Taking glitch and failure as a starting point, Sundén (Citation2016) develops a posthumanist vision of feminism as a set of technologies that are always already broken, incomplete and bound to failure. She argues that disconnection and glitch make the underlying and hidden machines that sustain our social relationships as well as categories visible.

These earlier approaches to disconnection share that they focus exclusively on practices of disconnection while dismissing other potentially interrelated practices. In contrast, we bring the literatures on disconnection in conversation with social movement studies to consider non-use in the context of other media and non-media related political practices (Treré, Citation2018). Hence, earlier studies of disconnection and media refusal advocate an understanding and perspective on media that is media-centric and can be compared to media activism that has media as an object to be revolutionized or reformed (e.g. the media reform movement, see for example Pickard, Citation2014). We suggest considering disconnection also in a non-media centric way, namely in relation to other political practices and in a non-single media manner (see for a critical discussion Treré, Citation2018). The typology developed here considers digital disconnection as part of activism that strategically employs and rejects media to further their political causes that might but not necessarily relate to media as objects.

Three-dimensional matrix of social movement studies

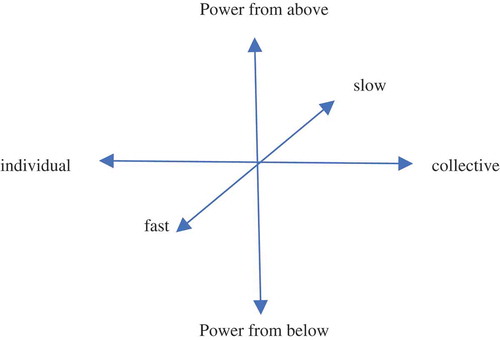

The following three-dimensional matrix summarizes central categories of social movement studies that have shaped the understanding of how social movements emerge and evolve over time (see ). The matrix is used later on to situate digital disconnection within social movements as political practice.

Power relations and social movements

One central aspect in the study of social movements is the question of power. Discussions have focused on power relations within social movements as well as in relation to other social and political institutions that might be addressed as part of the political struggle movements engage in. In terms of power relations within social movements, studies have focused on the role and emergence of hierarchies particularly when it comes to decision-making processes (Tarrow, Citation2011).

In general, social movements are considered as drivers of social change from below that are addressing political elites and authorities exercising political power in society. Sidney Tarrow argues that contentious politics emerge ‘when collective actors join forces in confrontation with elites, authorities, and opponents around their claims or the claims of those they claim to represent’ (Tarrow, Citation2011, p. 4). The potential for contentious politics evolves in relation to political opportunities that might foster or hinder the mobilisation of actions of people that are otherwise rather limited in their power. He argues ‘when their actions are based on dense social networks and effective connective structures and draw on legitimate, action-oriented cultural frames, they can sustain actions even in contact with powerful opponents. in such cases – and only in such cases – we can speak of the presence of a social movement’ (Tarrow, Citation2011, p. 16). For the mobilization of individuals to contribute to collective action is largely based on shared beliefs and identification as well as social networks that foster connective structures and suggest suitable forms of political action.

The question of power relations in and of social movements is hence crucially concerned with the question of agency (Treré, Citation2016). Power can be either exercises from above, e.g. by state bodies and institutions or from below, e.g. by individuals or social movements as grassroots organization that have to achieve political power through contentious politics. The question where power is situated and exercised is also crucial for disconnection as a form of political practice.

Collective versus individual aspects of social movements

Beyond the question of power, social movement studies have engaged with questions of individual versus collective aspects of political participation. Earlier approaches emphasizing rational choices to commit to collective causes have asked for the motivation of individual activists to contribute to collective action while risking prosecution and violence (free rider problem). This focus shifted in the 1970s and 1980s towards the question resource of social movements for mobilization. More particularly social movement scholars engaged with the question of how movements mobilize individuals to participate and which organizational forms allow for successful mobilization. This includes both human and social resources implying a broad understanding of resources referring to land, work and capital but also authority, social status and personal initiative (Eyerman & Jamison, Citation1991).

Over the time, these approaches were extended with cultural aspects of processes of identification and collective identity. Particularly symbolic expression became important to explain collective process of political participation. With the emergence of digital media, the field was extended with explorations of how collectivities are organized and mobilized through new media platforms (Treré, Citation2015; Della Porta, Andretta, Mosca, & Reiter, Citation2006; Gerbaudo, Citation2012; Kavada, Citation2015; Mercea, Citation2012; Uldam, Citation2010). These studies engaged with the question of how the collective agency of social movements, such as the global justice movement, environmental activism, or anti-austerity protests, has been enabled and reinforced through new media and the practices of collective identification they allow for. Treré (Citation2015), for example, engages with hashtags and viral images as expressions of collective identification with political causes and organizations in the context of digital media. ‘Social media, as a language and a terrain of identification’, Gerbaudo argues, ‘becomes a source of coherence as shared symbols, a centripetal focus of attention, which participants can turn to when looking for other people in the movement’ (Citation2013, p. 266).

However, particularly social media have been equalized with growing individualization of media practices and hence emphasizing the individual rather than collectives. Hartley’s concept of ‘do-it-yourself citizenship’ (Citation2010), for example, emphasizes television viewers’ agency. Such forms of political agency, van Zoonen, Visa, and Mihelja (Citation2010) argue are forms of ‘unlocated citizenship’, namely of citizenship not necessarily linked to established political institutions. Social media can form the space where such citizenship is fostered, in ways that are ‘self-actualizing’ rather than ‘dutiful’ (Bennett, Wells, & Rank, Citation2009). A major characteristic of such forms of action, according to Bennett is the emergence of the individual as an important catalyst of collective action through the mobilization of her social networks, itself enabled through the use of social media (Bennett, Citation2012, p. 22). Such networked action is an expression of ‘personalized politics’, as it is conducted across personal action frames, which embrace diversity and inclusion, lower the barriers of identification with the cause, and validate personal emotion (Bennett, Citation2012, pp. 22–23). In this context, ‘connective action’ is substituting ‘collective action’ in the public space (Bennett & Segerberg, Citation2013).

Temporality of social movements

Tarrow (Citation2011) has famously conceptualized protest cycles or cycles of contention that follow different intensities of mobilization and organization over time. These cycles and varying intensities of social movements are closely linked to the political opportunity structure. Besides periods of intense activism, there are phases of latency. Periods of slow development and latency are similarly crucial parts of social movements as high-paced periods of intense mobilization and rapid change. However, Tarrow’s concept of protest cycles assumes a linear temporal development of social movements. In contrast, ethnographic and phenomenological accounts often emphasize the multi-layered character of temporalities of civic engagement (Keightley, Citation2013). Postill (Citation2013), for example, develops a theory of multiple temporal layers of protest, which goes in hand with the very diverse media technologies used in the organizational process. He relies on Sewell’s conceptualization of historical sequences as temporally multi-layered social processes (for an overview on this approach also see Kaun, Citation2016). Consequently, he develops events, trends and routines as important categories that constitute a heterogeneity of protest time. While events refer to concentrated sequences of action that transform social structures; trends are less concentrated, but rather directional changes in social relations. Lastly routines are more or less stable schemata that reproduce social structures. Postill shows in his analysis of the Indignados movement in Spain that protests are made up of countless timelines that run parallel to each other. Similarly, Veronica Barassi (Citation2015) considers the multiplicity of protest time. In contrast to Postill, however, she concludes that even if protests are temporally multi-layered, activists always have to relate to a hegemonic perception of time. In information based, communicative capitalism this hegemonic perception of time is connected with speed, presentness and immediacy. The temporality of media practices that activists are navigating is essential not only for the possibility of protest, but also for the possibility of critique that is put forward by the protesters. Protest marks an accelerated temporality that is preceded by tedious preparations and organization for the activists. Protest in form of marches or protest camps establishes a new kind of temporality for those directly involved and those affected in their daily routines and flows (Kaun, Citation2016). Hence protesters are acting within a protest time that is related to a more general regime of temporality, or as Barassi (Citation2015) calls it, hegemonic perception of time. Mattoni and Treré (Citation2014) conceptualize the role of time for social movements around micro, meso and macro scales: on the micro level, they identify punctuated events that potentially transform the movement. The meso level temporality relates to cycles, tides and waves of mobilization that go beyond single events, but can be considered as concluded sequences. The macro level temporality concerns epochs of mobilization that are connected to a certain set or templates for mobilization and that are shared, for instance, within a generation of social movements. For the current typology, rather than being concerned with overall cycles of social movements, we focus on questions of temporality on the micro level concerning the particular speed – fast versus slow – that the specific practice of digital disconnection entails.

Types of political disconnection from digital technologies

Drawing on the three-dimensional matrix conceptualizing political activism and social movements, we develop a typology of disconnection or push-back activism. The three proposed types – digital disconnection as repression, digital disconnection as resistance and digital disconnection as performance – are characterized by specific configurations of the categories discussed above, namely power relations, temporality and level of collectivity (see ). We exemplify the suggested types with a number of current examples of disconnection activism.

Table 1. Overview of types of disconnection activism.

Digital disconnection as repression

Digital disconnection as repression is characterized by power from above, fast pace and a high level of collectivity. Power from above refers to the level of implementing disconnection, namely by states or elites in relation to populations that do not have similar access to force. The actions are implemented relatively fast and can be adjusted to changing contexts quickly. The disconnection practices have consequences on a collective level and address larger groups rather than individuals while potentially triggering collective reactions (contentious politics).

Howard et al. distinguish between different forms of shutdown practices. Firstly, they suggest there are complete network shutdowns causing a complete telecommunication blackout. Secondly, there specific site-oriented shutdowns addressing particular websites that have been identified as problematic. Thirdly, they suggest shutdowns take the shape of disconnecting specific individual users that have acquired a powerful role as node within a network. Lastly, shutdowns are exercised by proxy through internet service providers. As an example of the first form of shutdown, Gerbaudo (Citation2013) discusses the consequences of the total telecommunication blackout enforced by the Mubarak regime that was implemented in response to growing protest in the country. On 28 January 2011, the government blocked all internet access and only one ISP serving the stock exchange remained in place. Similarly, the Iranian government has recently been blocking internet access on mobile devices in response to growing protests against economic instability of the country. The shutdown of mobile internet occurred starting 30 December 2017 and included particularly the blocking of Instagram and Telegram (Center for Human Rights in Iran, Citation2018; Rao, Citation2018). However, not only these applications were blocked, but access to internet on mobile devices was slowed down considerably and completely cut off for at least half an hour according to the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI). Besides employing methods of partial and complete shutdowns in Iran, governments in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kashmir and Gabon have recently taken to similar measures to disrupt emerging political opposition and pulling the kill switch has been identified as growing and worrying trend on an international scale by commentators (Koebler, Citation2016; Neal, Citation2013).

An example for site-specific shutdown is the ban and raid of the Indymedia subsite linksunten in Germany. Identifying the site as being in conflict with German laws and ‘sowing hate against different opinions and representatives of the country’ the site was shut down in August 2017 by the Interior Ministry (Welle, Citation2017). Part of the justification of banning linksunten Indymedia was its classification as a political club rather than a media site, which reflects promises of cracking down on left-wing extremist groups by politicians in the aftermath of the G20 protests in Hamburg just seven weeks before.

These forms of disconnection take different shapes – on the one hand shutdown and on the other hand censorship – but share that they can lead to contentious politics and collective actions counter to the intentions of the political elites that were implementing them. For instance, Gerbaudo (Citation2013), shows how the kill switch turned into a suicide switch by alienating the internet-savvy middle class and making face-to-face meet ups necessary. Consequently, the blackout effectively drew people to Tahrir square instead from keeping them off the streets. This powerful reaction of Egyptian citizens to the digital blackout displays the ongoing significance of physical relationships within social movements, and strongly counteracts the image of contemporary activism as being increasingly relegated to an immaterial virtual sphere. The kill switch backlashed precisely because Egyptian authorities overestimated the revolutionary power of digital technologies for collective action in the short term, while at the same time underestimating the capacity of the people to concomitantly rely on offline connections and physical ties, and their will to take to the streets and the squares. Furthermore, as Gerbaudo shows, the sudden absence of any digital and mobile connection made activists aware of how much they were relying on networked media to carry out their protest actions, often in an excessive way. Thus, this digital deprivation had paradoxically the effect of making them focus on their more pressing daily needs, to regain a deeper sense of locality, and to concentrate their energy in the organization and coordination of the street protests in the hic et nunc. As Gerbaudo remarks,

The kill switch facilitated the development of a thick face-to-face experience that was crucial in sustaining collective action for several days in Tahrir Square and central Cairo, in which it did not seem to matter too much to people that they did not have internet connection or working mobile phones (Citation2013, p. 38).

This example clearly illustrates that disconnection as repression may engender unexpected practices of resistance that heavily exploit non-digital communications: shutting down the online realm can thus stimulate offline connections and protest. Other examples of disconnection as repression include the removal of websites and social media platforms that have particular relevance for activists. For instance, the Mexican website 1dmx.org was set up in the wake of a set of controversial protests held on 1 December 2012, against the inauguration of the new – now former – President of Mexico, Enrique Peña Nieto. For one year, the site served as a source of information, discussion and commentary from the point of view of the protesters. In particular, it included pictures, videos and testimony created by activists that documented the abuses committed by the police, and tried to counteract the official institutional narrative that was reassuring Mexican citizens that everything was going smoothly. As the anniversary of the protests approached, the site grew to include organized campaigns against proposed laws to criminalize protest in the country, as well as preparations to document the results of a memorial protest that was planned for 1 December 2013. On December 2nd, 2013, the site disappeared from the internet, since the United States host, GoDaddy (one of the largest companies in the world for providing online domains) suddenly suspended the domain without giving prior notice. The company told its owners that the site was taken down ‘as part of an ongoing law enforcement investigation’. The office in charge of this investigation was listed as ‘Special Agent Homeland Security Investigations, U.S. Embassy, Mexico City’ (the contact email pointed to ‘ice.dhs.gov’, implying that this agent was working as part of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement wing, who have been involved in domain name takedowns in the past). Following the legal pressures of the 1DMX website team that spurred an investigation, a complex intrigue emerged, showing that the United States Embassy in Mexico was used as a mere facade for the Mexican Government that in the end was the one responsible for the website takedown. While the website was eventually reactivated, its sudden removal had profound consequences on Mexican activist practices. Their energies had to be rechanneled on creating a mirror website, and on finding ways to regain possession over the obscured platform, by means of complex legal procedures (the Mexican legal system is renowned for its intricacy) and by publicly denouncing the dramatic takedown on social media, alternative media and newspapers. Thus, this act of digital removal perpetrated by the government heavily destabilized the consolidated routine of Mexican activism, and jeopardized the organization of future protests and mobilizations.

In line with the previous example, Uldam (Citation2016) has explored ‘silencing’, e.g. the taking down of critical and opposing websites or social media accounts as one strategy by corporations in the oil industry – more specifically BP and Shell – to manage mediated visibility. In that case, the power to disconnect is also exercised from above, however, not by the state but by corporate elites. However, as the Mexican 1DMX example illustrates, sometimes silencing of political antagonists can be more effectively achieved by a dangerous amalgamation of tech companies and governments.

Digital disconnection as resistance

Digital disconnection as resistance concerns practices of refusal to comply with specific political contexts and developments that are implemented by actors that are not part of the political elite and belong to grassroots organization. They share the temporality of relative slowness as disconnection as resistance concerns practices that are constantly negotiated depending on the technological development and political context. In that, they are never stable or finalized. We distinguish however between on the one hand practices of disconnection as resistance on an individual level, and on the other hand practices of disconnection as resistance on a collective level. Disconnection that is subsumed in this section concerns the use of tactics that force adversaries to disconnect, along with the (almost) completely eschewing of digital media and the partial disconnection from specific platforms as forms of political resistance.

In the previous section we analyzed how disconnection can be enforced from above as a form of repression, cyber-attacks such as the Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) show that forcible disconnection can also acquire the shape of an activist tactic. This tactic is employed by activists to target political adversaries seeking to make an online service unavailable to its intended users by disrupting services of a host connected to the internet, usually overwhelming it with traffic from multiple sources. A DDoS can cause the network to slow down, specific websites to be inaccessible, as well as the disconnection of a wireless or wired internet connection. This kind of attacks have been used both against symbols of neoliberal oppression such as corporate and multinational banks’ websites, as well as against independent media sites like PopVote in the 2014 Hong Kong protests (Olson, Citation2014). These forms of forced disconnection as activist tactic are fast paced and conducted by individuals or smaller networks of actors.

An example of disconnection as resistance against the commercial use of data produced in social media platforms (from below, slow and individualized) is data obfuscation. Brunton and Nissenbaum (Citation2011, Citation2015)) for instance have identified different forms of obfuscation as strategies to resist ubiquitous surveillance and data extraction in the network ecology. They argue that almost any form of mundane contact with digital media involves involuntary data extraction. In that context, they identify emerging forms of resistance through obfuscating data trace that are left while using digital media. Further, they present FaceCloak and TrackMeNot browser plugins as two examples that help users managing their data traces in social media or while surfing the internet more generally. FaceCloak provides you with the possibility to choose between keeping your information private through encryption and storage on a separate server or sharing them openly with Facebook. Additionally, FaceCloak generates fake information Facebook requires from you for your profile. In contrast TrackMeNot obfuscates web searches by adding ghost searches to your ‘real inquiries’. The plugin makes it harder for search engines to identify search patterns that are relevant for third parties (Brunton & Nissenbaum, Citation2011). In terms of temporality, these practices do not necessarily emphasize or foster slowness. Quite the opposite, they seem to promote faster online experiences by eliminating unnecessary noise, often in form of advertisement. However, the solutions are rather short-term as commercial platforms often quickly stop applications that run counter to their established business model of valorizing data traces. Hence, the applications have to be constantly adapted and changed. These forms of data obfuscation provide the individual users with possibilities to disconnect their data traces from commercial platforms, while still being able to use the platforms. However, the technological solutions need to be constantly updated and renegotiated depending on changes of the concerned digital platforms.

Other forms of disconnection as resistance share that they are ‘powered’ from below, and slow in their implementation and evolution. In contrast to data obfuscation and detox, they are however more collective in character. Furthermore, these practices constitute forms of complete disconnection from certain platforms or digital media formats. Andersson (Citation2016) explores forms of almost extensive non-participation in digital platforms of Swedish radical left groups. He argues that the groups disengage with digital media platforms in order to claim autonomy. Observing a sparse use of platforms such as YouTube and Facebook to disseminate political propaganda, Andersson argues that the media practices of radical left groups such as Anti-Fascist Action (AFA) and the Revolutionary Front follow the principle of ‘acting without being seen’, which collides with the affordances of connectivity and visibility of social media’ (Andersson, Citation2016, p. 60). However, the mode of completely eschewing digital media is rarely practiced. More common forms of resistance concern partial disconnection from specific platforms or specific practices within certain platforms. In contrast, Gehl (Citation2016) provides an ethnography of a dark web social networking site within which the users have implemented community standards that have been collectively negotiated. These standards include completely anonymity, full exclusion of child pornography and any commercial activities. Similarly, to strategies of obfuscation discussed above, the community aims to make use of the advantages of social networking sites, while disconnecting from specific features that are prevalent in commercial platforms, such as real name policy and commercial activities. However, in comparison to individualized forms of data obfuscation, dark web social networking sites are often developed as collective efforts within FOSS communities.Footnote1 Hence, they rather follow the spirit of alternative media than individualized forms of hiding data traces.

Furthermore, Anonymous practices of hacking could be situated within this realm of disconnection as resistance. Deseriis (Citation2013) argues that the main purpose of Anonymous – similar to the Luddites in the 19th century – is to attack specific machines. In the case of Anonymous, machines that restrict the access to information or information technologies. Although Anonymous is characterised by diversity of individual contributors and a radical openness that can be appropriated by individual and collective action, the name Anonymous functions as collective pseudonym: individuals align around a collective that is loose, but shares certain common forms of subjectification. This, Deseriis illustrates, brings different political struggles together discursively.

Digital disconnection as lifestyle politics

The third type of digital disconnection, refers to disconnection as performance or life style (Portwood-Stacer, Citation2013) and captures practices by actors from below rather than political elites. These are comparatively fast paced practices on the micro level and they are highly individualized.

One of the major examples illustrating this type of disconnection are practices of leaving certain social media platforms, for example Facebook. Deleting ones Facebook account has gained new traction in the aftermaths of the Cambridge Analytica scandal around misuse of Facebook data by third parties. Portwood-Stacer has earlier discussed practices of leaving Facebook as enacting and showing a political identity on an individual level rather than collective action. Although there are groups and initiatives around these practices of leaving, such as the Quit Facebook Day, the act and consequences are highly individualized and described as such. Portwood-Stacer (Citation2013) argues that this form of conspicuous non-consumption or media refusal constitutes a performative mode of resistance and is situated in the realm of consumer empowerment through which certain political ideas and identities are expressed in contrast to collective mobilizations. Karppi (Citation2011) analyzes artistic projects that play with ideas of non-use and disconnection from social media, e.g. the Facebook suicide machine, to create awareness of the platform’s ubiquity and biopolitical implications.

Similarly, digital detox camps, such as Camp Grounded in California or the Villa Insight in Sweden, are forms of disconnection as lifestyle, where the choice to participate or perform a digital detox offers a way to distinguish oneself from ‘ordinary’ users that uncritically consume digital media (Fish, Citation2017; Sutton, Citation2017). Another example of disconnecting as lifestyle politics is the data detox programme developed by the tactical technology collective (Tactical Technology Collective, Citation2017; Galer, Citation2017). The eight-day guide is supposed to help you firstly realize the extent to which you leave data trace and secondly, to detox and scale them down. Adapting the style and language of popular detox programmes, the initiative suggests ‘you’ll be well on your way to a healthier and more in-control digital self’ after concluding the eight steps. In contrast to the detox camps, this initiative has, however, no commercial interest. Interventions such as the Slow Media ManifestoFootnote2 that promotes more conscious ways of producing and consuming media also emphasize individual forms of disconnection (Rauch, Citation2011), and often emanate a certain nostalgia towards old/analogue media devices and formats. Hence, the political implications of media slowness and media refusal remain in the background, and social media abstinence is conceived as lifestyle choices through individual consumption, rather than forms of collective political action. This point is illustrated by Fish (Citation2017), when he compares today’s culture of digital rejection with the Free Speech movement of the 1960s at Berkeley, California. While the latter movement protested against the computer-readable punch cards in order to explicitly make a political point (basically: not to be dehumanized by being reduced to mere bits of digital information), our culture of technological rejection has lost this political resonance in favor of lifestyle consumerism. Thus, Fish argues, today’s culture of digital rejection does not look for social regulation, but only strive to gain individual balance, in line with the Mindful/New Age spirituality that pervades the Silicon Valley ethos. What is needed, Fish concludes, is instead to politicize detox retreats, using them as venues to build collective consciousness and mobilization efforts towards building – among other things – social regulation around social media overuse as the initiative of the Tactical Technology Collective suggests.

Another form of disconnection as lifestyle combines slowness and individualized ways to disconnect with a power perspective from above. We are here referring to attempts to introduce regulations to disconnect and re-establish boundaries between work and private life either on the governmental or corporate level that were developed in response to mobilizations against increased digital stress especially by trade unions. France, for example, introduced legislation banning emails after working hours. Similarly, in Germany there has even been a discourse on regulating work-related digital stress from a policy perspective. The German Federal Minister of Labour and Social Affairs Angela Nahles in November 2016 suggested to introduce regulations to reduce stress related to digitization. On the corporate level, large companies like Volkswagen, Daimler and BMW have introduced strict regulations of using communication devices for work-related tasks after working hours (Hesselberth, Citation2018). Although regulations here are introduced from above and concern larger groups, they address negative consequences related to digital media largely as individual problems that need individualized responses (for a similar analysis, see Hesselberth, Citation2018). Stress related to digital technologies in the work context is considered in isolation. This includes the idea to regulate the time when an individual worker is allowed to send or receive an email, rather than tackling the issue of work-related stress on a more structural level, including issues of job security or freelance work that enhances the precariousness of boundaries between work and private life, which might include problems related to digital technologies.

Discussion

The typology of disconnection activism presented here is based on a three-dimensional matrix that systematizes and puts in relation central categories developed within social movement studies. Bringing disconnection and social movement studies together in that way, we aim to chart a systematic discussion of how non-use and media refusal plays out as political practice. Typologies have the advantage to reduce complexity, allow for comparison and the study of relationships (Baily, Citation1994). Furthermore, typologies potentially provide criteria to explore empirical phenomena more in-depth as they identify similarities and differences between cases. However, there are of course problematic aspects of developing typologies. Typologies often remain descriptive and rarely provide explanations for certain phenomena. They also tend to reify theoretical assumptions that are hardly observable empirically. In that sense, they constitute static classifications (Baily, Citation1994). Although typologies are not without problems, we believe they are helpful in developing a systematic description and inventory of practices of media non-use that have been overlooked by research so far. The types of disconnection activism suggested here need however further empirical investigation and theoretical engagement.

Conclusion

While disconnection, media refusal and technology non-use represent phenomena that are not exclusively linked to digital media, they have gained new qualities and intensified, following the process of deep mediatization in the digital age (Couldry & Hepp, Citation2017). Practices of disconnection supposedly counter the hegemonic temporality of fast capitalism that is especially connected to the adoption and massive spread of social media platforms. In this article, we propose to consider push-back activism and media refusal as part of the media repertoire of social and protest movements. In contrast to early investigations of media practices in the context of political mobilization that largely ignored media refusal and push-back activism, we argue that media practices in complex media ecologies encompass both use and non-use of media. We believe that the dialogue we initiate in this article between disconnection studies and social movement studies, and the subsequent typology that originates from it, contributes to the literature in various ways.

First, it shows that if we want to understand social movements’ media practices holistically, we need to consider disconnection and non-use strategies in relation to forms of media engagement and use. As we argue, studies on digital activism have often taken for granted the connectedness of recent movements, privileging the exploration of highly networked and innovative case studies over the investigation of forms of contention that are not geared towards technologically mediation. We have also seen that this tendency has only been intensified by the increasing importance that big data methodologies are acquiring within this area of research.

Our study shows that we need to re-equilibrate the balance and start to pay serious attention to the negotiations, tactics and motives of those who decide to avoid, refuse and withdraw from digital connection and the relation of these disconnection practices to technology use. In an era where our attention is systematically exploited and competed for by tech conglomerates through increasingly sophisticated techniques, this issue acquires an even stronger political relevance. If we keep taking for granted that contemporary activism is inherently digitally networked and continue to mainly highlight media uses, we risk losing track of one of the most controversial aspect of today’s activism. Namely, that the corporate platforms on which protest is largely carried out have a deep interest in monetizing the time we devote to activism, and this is fundamentally altering the dynamics through which we are able to build our democracies, and imagine alternative political futures. Thus, it is precisely at activists’ continuous negotiations with social media platforms (selection, rejection, withdrawal, refusal, etc.) that we should look to understand the ambivalences and controversies inherent in contemporary activism.

Second, our typology is able to shed light on the different faces and changing contexts of media disconnection while drawing on established knowledge from social movement studies. While in some cases disconnection is imposed and enacted with the purpose of undermining activism, in others it is at the core of resistance from below and has a central political role to play in the context of activism. The typology of push-back activism is the first attempt to systematize practices of (digital) media non-use in the context of political practices and contentious politics. Future studies are needed to further explore nuances of disconnection types and investigates them in relation to hyper-connected cases.

The article makes the case against the normative implications and assumptions about connectivity as something inherently good and desirable that have dominated research of the nexus between media and movements. In that sense, the article contributes a perspective that questions the dominant ideology of connectivity of the digital society where disconnection is neglected as well as the overemphasis of hyper-connected social movements in the digital age.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers and the editors of the special issue for their constructive feedback that helped to considerably improve the article. Both the authors contributed equally to this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anne Kaun

Anne Kaun is Associate Professor at the Department for Media and Communication Studies at Södertörn University, Stockholm. Her research combines archival research with interviews and participant observation to better understand changes in how activists have used media technologies and how technologies shape activism in terms of temporality and space. She is currently developing her new project on prison media tracing the media practices and media work since the inception of the modern prison system. Anne currently serves as a chair of the ‘Communication and Democracy’ section of ECREA (European Communication Research and Education Association).

Emiliano Treré

Emiliano Treré is a lecturer at the School of Journalism, Media and Culture at Cardiff University, UK. He has researched and published extensively on the challenges, the opportunities and the myths of media technologies for social movements, activist collectives and political parties in Europe and Latin America. He is the author of Hybrid Media Activism: Ecologies, Imaginaries, Algorithms and the coeditor of Citizen Media and Practice: Currents, Connections, Critiques. Both volumes are forthcoming with Routledge. He serves as the vice-chair of the ‘Communication and Democracy’ section of ECREA (European Communication Research and Education Association).

Notes

1. FOSS communities promote free and open-source software as part of their political approach to software (Velkova, Citation2017).

2. The Slow Media Manifesto – a 14-point list of commandments of slowness – was published in 2010 by Benedikt Köhler, Sabria David and Jörg Blumtritt. It was shortly after discussed by several online news outlets such as the Huffington Post and Wired. Consequently, it was broadly discussed and translated into eight languages, see http://en.slow-media.net/manifesto.

References

- Andersson, L. (2016). No digital “Castles in the air”: Online non-participation and the radical left. Media and Communication, 4(4), 53–62.

- Baily, K. D. (1994). Typologies and taxonomies: An introduction to classification techniques. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Barassi, V. (2015). Social media, immediacy and the time for democracy: Critical reflections on social media as ‘Temporalizing practices’. In L. Dencik & O. Leistert (Eds.), Critical perspectives on social media and protest: Between control and emancipation (pp. 73–90). London, New York: Rowman and Littlefield International.

- Barranquero, A. (2013). Slow media. Comunicación, cambio social y sostenibilidad en la era del torrente mediático. Palabra clave, 16(2), 419–448.

- Bennett, L., & Segerberg, A. (2013). The logic of connective action. Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Bennett, L., Wells, C., & Rank, A. (2009). Young citizens and civic learning: Two paradigms of citizenship in the digital age. Citizenship Studies, 13(2), 105–120.

- Bennett, W. L. (2012). The personalization of politics: Political identity, social media, and changing patterns of participation. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 644(1), 20–39.

- Brubaker, J. R., Ananny, M., & Crawford, K. (2016). Departing glances: A sociotechnical account of ‘leaving’ Grindr. New Media & Society, 18(3), 373–390.

- Brunton, F., & Nissenbaum, H. (2011). Vernacular resistance to data collection and analysis: A political theory of obfuscation. First Monday, 16(5).

- Brunton, F., & Nissenbaum, H. (2015). Obfuscation: A user’s guide for privacy and protest. Boston: MIT Press.

- Casemajor, N., Couture, S., Delfin, M., Goerzen, M., & Delfanti, A. (2015). Non-participation in digital media. Toward a framework of mediated political action. Media, Culture & Society, 37, 850–866.

- Center for Human Rights in Iran. (2018). Iran’s severely disrupted internet during protests: “websites hardly open”.

- Couldry, N., & Hepp, A. (2017). The mediated construction of reality. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Croeser, S., & Highfield, T. (2015). Mapping movements–Social movement research and big data: Critiques and alternatives. In: Langlois, G, Redden, J. & Elmer, G. (Eds.), Compromised data: From social media to big data (pp. 173–202). New York, NY: Bloomsbury.

- Della Porta, D., Andretta, M., Mosca, L., & Reiter, H. (2006). Globalization from below. Transnational activits and protest networks. Minnesota, London: University of Minnesota Press.

- Deseriis, M. (2013). Is Anonymous a new form of Luddism? A comparative analysis of industrial machine breaking, computer hacking and related rhetorical strategies. Radical History Review, 2013(117), 33–48.

- Drotner, K. (1999). Dangerous media? Panic discourses and dilemmas of modernity. Paedagogica Historica, 35(3), 593–619.

- Earl, J., & Kimport, K. (2011). Digitally enabled social change: Activism in the internet age. Cambridge, London: Mit Press.

- Eyerman, R., & Jamison, A. (1991). Social movements: A cognitive approach. Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Fish, A. (2017). Technology retreats and the politics of social media. TripleC, 15(1), 355–369.

- Galer, S. S. (2017). The eight-day guide to a better digital life. BBC future.

- Gehl, R. (2016). Power/freedom on the dark web: A digital ethnography of the dark web social network. New Media and Society, 18(7), 1219–1235.

- Gerbaudo, P. (2012). Tweets and the streets. Social media and contemporary activism. London: Pluto Press.

- Gerbaudo, P. (2013). The ´kill switch’ as ‘suicide switch’: Mobilising side effects of Mubarak’s communication blackout. Westminster Papers, 9(2), 25–43.

- Hartley, J. (2010). Silly citizenship. Critical Discourse Studies, 7(4), 233–248.

- Hesselberth, P. (2018). Discourses on disconnectivity and the right to disconnect. New Media and Society, 20(5), 1994–2010.

- Karppi, T. (2011). Digital suicide and the politics of leaving facebook. Transformations, 2011(20), 1–18.

- Kaun, A. (2016). Crisis and critique: A brief history of media participation. London: ZedBooks.

- Kavada, A. (2015). Creating the collective: Social media, the occupy movement and its constitution as a collective actor. Information, Communication & Society, 18(8), 872–886.

- Keightley, E. (2013). From immediacy to intermediacy: The mediation of lived time. Time & Society, 22(1), 55–75.

- Koebler, J. (2016). Gabon is suffering the “worst communications suppression since the Arab spring”. Motherboard.

- Krapp, P. (2011). Noise channels: Glitch and error in digital culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Kuntsman, A., & Miyake, E. (2017). Paradoxes of digital dis/engagement: A pilot study (concept exploration). Leeds . Retrieved from http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/114806/1/Final-report-Digital-Disengagement-Kuntsman-Miyake.pdf

- Light, B. (2014). Disconnecting with social networking sites. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mattoni, A., & Treré, E. (2014). Media practices, mediation processes, and mediatization in the study of social movements. Communication Theory, 24(3), 252–271.

- Mejias, U. A. (2013). Off the network: Disrupting the digital world. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Mercea, D. (2012). Digital prefigurative participation: The entwinement of online communication and offline participation in protest events. New Media & Society, 14(1), 153–169.

- Mullaney, J. (2006). Everyone is NOT doing it. Abstinence and personal identity. Chicago, London: University of Chicago Press.

- Neal, M. (2013). Are governments getting trigger-happy with the internet kill switch? Motherboard.

- Olson, P. (2014). The largest cyber attack in history has been hitting hong kong sites. Forbes, November.

- Pickard, V. (2014). America’s battle for media democracy: The triumph of corporate libertarianism and the future of media reform. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Pink, S. (2008). Sense and sustainability: The case of the slow city movement. Local Environment, 13(2), 95–106.

- Portwood-Stacer, L. (2013). Media refusal and conspicuous non-consumption: The performative and political dimensions of Facebook abstention. New Media & Society, 15(7), 1041–1057.

- Postill, J. (2013). The multilinearity of protest: Understanding new social movements through their events, trends and routines. Melbourne. Retrieved from http://johnpostill.com/2013/10/19/the-multilinearity-of-protest/

- Rao, A. (2018). Iran is blocking the internet to shut down protests. Motherboard.

- Rauch, J. (2011). The origin of slow media: Early diffusion of a cultural innovation through popular and press discourse, 2002-2010. Transformations, 20, Retrieved from http://www.transformationsjournal.org/journal/issue_20/article_01.shtml.

- Ribak, R., & Rosenthal, M. (2015). Smartphone resistance as media ambivalence. First Monday, 20(11).

- Rosa, H. (2013). Social acceleration: A new theory of modernity. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Selwyn, N. (2003). Apart from technology: Understanding people’s non-use of information and communication technologies in everyday life. Technology in Society, 25(1), 99–116.

- Skågeby, J. (2011). Slow and fast music media: Comparing values of cassettes and playlists. Transformations, 2011(20), 1–17.

- Strömbäck, J., Djerf-Pierre, M., & Shehata, A. (2013). The dynamics of political interest and news media consumption: A longitudinal perspective. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 25(4), 414–435.

- Sundén, J. (2016). Glitch, genus, tillfälligt avbrott: Femininitet som trasighetens teknologi [Glitch, gender, temporary disconnection: Femininity as brokenness technology]. Lambda Nordica, 2016(1–2), 23–45.

- Sutton, T. (2017). Disconnect to reconnect: The food/technology metaphor in digital detoxing. First Monday, 22(6). doi:10.5210/fm.v22i6.7561

- Syvertsen, T. (2017). Media resistance: Protest, dislike, abstention. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tactical Technology Collective. (2017). The 8-Day Data Detox.

- Tarrow, S. (2011). Power in movement: Social movements and contentious politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Thorén, C., & Kitzmann, A. (2015). Replicants, imposters and the real deal: Issues of non-use and technology resistance in vintage and software instruments. First Monday, 20(11). doi:10.5210/fm.v20i11.6302

- Treré, E. (2015). Reclaiming, proclaiming, and maintaining collective identity in the# YoSoy132 movement in Mexico: An examination of digital frontstage and backstage activism through social media and instant messaging platforms. Information, Communication & Society, 18(8), 901–915.

- Treré, E. (2018). The sublime of digital activism: Hybrid media ecologies and the new grammar of protest. Journalism & Communication Monographs, 20(2), 137–148.

- Treré, E. (2016). The dark side of digital politics: Understanding the algorithmic manufacturing of consent and the hindering of online dissidence. IDS Bulletin, 47(1), 127–138.

- Uldam, J. (2010). Fickle Commitment. Fostering political engagement in ’the flighty world of online activism’. ( PhD Thesis), Copenhagen Business School, Copenhagen. ( 35.2010)

- Uldam, J. (2016). Corporate management of visibility and the fantasy of the post-political: Social media and surveillance. New Media & Society, 18(2), 201–219.

- van Zoonen, L., Visa, F., & Mihelja, S. (2010). Performing citizenship on YouTube: Activism, satire and online debate around the anti-Islam video Fitna. Critical Discourse Studies, 7(4), 249–262.

- Velkova, J. (2017). Media technologies in the making: User-driven software and infrastructures for computer graphics production (PhD dissertation). Huddinge. Retrieved from http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:sh:diva-33681.

- Wajcman, J. (2015). Pressed for time. The acceleration of life in digital capitalism. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Welle, D. (2017). Interior ministry shuts down, raids left-wing German Indymedia site.

- Woodstock, L. (2014). Media resistance: Opportunities for practice theory and new media research. International Journal of Communication, 8, 19.

- Wyatt, S., Graham, T., & Terranova, T. (2002). They came, they surfed, and they went back to the beach: Conceptualizing use and non-use of the Internet. In S. Woolgar (Ed.), Virtual society? Technology, cyberbole, reality (pp. 23–40). Oxford: Oxford University Press.