ABSTRACT

With climate change litigation (CCL) being increasingly used by climate activists, its consequences for public discourses on climate change warrants attention. Considering CCL as public campaigning tool, this study presents a quantitative and qualitative analysis of national media coverage on three CCL cases in the Netherlands focusing on individual claims of key actors (N = 1,394). Discerning generic and issue-specific frames, this study compares general modes of justifications mobilized by different actors and specific arguments made within these normative views. Findings show that climate activists were largely successful in determining the dominant normative perspectives and the majority of issue-specific arguments of defendants were prompted by activists’ arguments. A strong focus on ecological and civic arguments, such as the responsibility for current and future generations, spurs public legitimacy while discussing solutions involved a greater variety of viewpoints which led to higher levels of controversy. The findings indicate that a separation of responsibility and solutions discourses may facilitate public legitimacy and hence benefit the goals of climate activists.

Climate activists worldwide increasingly initiate lawsuits against governments and corporations to enforce and accelerate political and corporate climate action (Setzer & Byrnes, Citation2019). A growing body of research on climate change litigation (CCL) signifies its relevance. However, assessments of the actual impact of climate litigation are scarce (McCormick et al., Citation2018; Setzer & Vanhala, Citation2019). Specifically, an assessment of indirect influences outside the courtroom is needed to deepen our understanding of the role that litigation can play in enhancing climate action (Setzer & Byrnes, Citation2019; Setzer & Vanhala, Citation2019). While legal and political scholars have begun to study direct influences on law, regulation, and policymaking (McCormick et al., Citation2018; Peel & Osofsky, Citation2013), there is limited knowledge on how CCL affects public awareness and related societal norms and values. Lawsuits and judgements concerning moral or normative questions, such as climate change, can be assumed to spur public debates in the media and may contribute to controversies about climate mitigation actions and attached responsibilities. Even cases that are unsuccessful in court may cause such indirect effects (Peel & Osofsky, Citation2013) by contributing to public meaning construction and national media discourses about climate change.

Previous research has considered CCL as focusing event and revealed bottom-up agenda-setting effects (Wonneberger & Vliegenthart, Citation2021): Media attention for climate litigation has been shown to trigger media and political attention for climate policies. However, little is known about how CCL is represented in the media and how it is debated among relevant actors. This is why the current study focusses on the content of climate litigation discourses. Building on theories of social movement frames and legitimacy maintenance (Boltanski & Thévenot, Citation2006; Patriotta et al., Citation2011; Snow et al., Citation2019), this study analyses and compares media discourses about three recent and distinct CCL cases in the Netherlands. In 2019, the environmental organization Urgenda won a trial enforcing the Dutch government to reduce national greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 25% until 2020. Milieudefensie, the Dutch Friends of the Earth (FoE), in contrast, has from 2016 to 2019 unsuccessfully sued the Dutch state for not acting effectively against air pollution. Finally, FoE won a lawsuit against the multinational Royal Dutch Shell in 2021 resulting in a legal obligation of the company to lower their emission levels by 45% until 2030. All three cases triggered public controversies about the responsibilities for climate actions. Moreover, these cases include different types of CCL (against the government versus a large corporation; directly addressing climate change versus the more narrowly defined case of air pollution, see Peel & Osofsky, Citation2013). With the Netherlands as national context and similar time frames, the socio-political context of the cases is held constant.

The goal of this study is to understand to what extent the environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs) initiating these three CCL cases were successful in framing the surrounding public discussions. More specifically, CCL is considered a campaigning device that can help to overcome indexing (Bennett, Citation2016), that is, the focus on elite actors in the media coverage on climate change (Tschötschel et al., Citation2020). A framework is developed discerning and integrating generic and issue-specific frames (Brüggemann & D’Angelo, Citation2018). Generic frames are defined as modes of justification that reflect the normative perspectives of actors’ arguments (Baden & Springer, Citation2017; Boltanski & Thévenot, Citation2006). On an issue-specific level, diagnostic and prognostic arguments made within these normative perspectives are discerned (Snow et al., Citation2019). This framework is applied to a quantitative and qualitative content analysis of actor claims in the media coverage. In addition to contributing to the framing literature, this study confirms the success of climate activists in using CCL as public campaigning tool and identifies facilitating mechanisms.

Media attention for climate change litigation

In addition to being a legal instrument, litigation initiated by members of the climate movement, oftentimes environmental non-governmental organizations (ENGOs), can be considered as campaigning tool that is (also) deployed to achieve public campaigning goals via media attention and public engagement (Chewinski & Corrigall-Brown, Citation2020; Smith, Citation2004). Typically, movement actors are considered to struggle for public or media attention while this attention at the same time is vital for their goals (Gamson & Wolfsfeld, Citation1993; Vliegenthart & Walgrave, Citation2012). Common barriers that explain challenges in creating media attention include journalistic gatekeeping or the focus on news values favoring elite actors and issues (Hilgartner & Bosk, Citation1988). In addition, the protest paradigm describes how media coverage contributes to de-legitimizing movements via the use of episodic as opposed to thematic frames and a focus on official resources (Hertog & McLeod, Citation1995; Rauch et al., Citation2007). However, more recently, a stronger ideological affinity or alignment between movements and media has been found to lower the impact of the protest paradigm (Kim & Shahin, Citation2020; Shoemaker & Reese, Citation2013). In the context of climate change, indeed, the media environment seems to be more favorable for climate activists and movements given that climate change journalists tend to follow the scientific consensus on climate change (Brüggemann & Engesser, Citation2017; Schmid-Petri et al., Citation2017). While media discourses on climate change increasingly shift from controversies about causes and consequences to controversies about solutions, research still finds that journalistic representations of these discussions are strongly focused on elite political actors (Rice et al., Citation2018; Tschötschel et al., Citation2020). This selective focus on the political debate has been coined as indexing (Bennett, Citation2016). In the climate change context, the indexing hypothesis suggests that journalistic gatekeeping concerning the issues and viewpoints covered prioritizes political actors over climate activists, citizens, and other less institutionalized actors (Schmid-Petri et al., Citation2017; Tschötschel et al., Citation2020). Hence, the success of CCL as public campaigning tool does to some extent depend on the ability of a litigation case to garner media attention and, moreover, on the extent to which media coverage about a case reflects the viewpoints of initiating ENGOs.

Framing climate change litigation

Viewpoints and related norms and values are reflected by the frames that are used in public discourses (Lueck et al., Citation2016; Tewksbury & Scheufele, Citation2009). Frames can focus on rather abstract questions of responsibilities or – along with general shifts observed in climate change news coverage (Schmid-Petri et al., Citation2017; Tschötschel et al., Citation2020) – may shift public attention toward the design and implementation of specific policies or toward legal questions. Analyzing the frames represented by the actors involved in CCL (environmental organizations, politicians, experts, citizens) allows to assess the full range of relevant normative viewpoints and, hence, the potential scope of indirect influences of CCL. While frames that capture an emphasis on specific problem definitions, causal explanations, treatment recommendations, and moral evaluations are oftentimes used to study distinct viewpoints, the way frames are conceptualized varies tremendously (D’Angelo, Citation2018). Following the call to synthesize the concepts of issue-specific and generic frames (Brüggemann & D’Angelo, Citation2018), this study considers two different levels of frames. First, generic frames – similar to master frames often applied in the social movement context – are comparable across issues and research studies (Carroll & Ratner, Citation1996; Walter & Ophir, Citation2019). Second, issue-specific frames gauge more specific nuances in the emphasis of problem definitions, causal explanations, treatment recommendations, and moral evaluations related to an issue by different actors (Brüggemann & D’Angelo, Citation2018; Walter & Ophir, Citation2019).

Generic frames: modes of justification

While aiming to gain resonance and public legitimacy for their viewpoints, movements remain in constant competition with oftentimes more dominant positions of elite actors (Vliegenthart & Walgrave, Citation2012). It is thus vital to not just focus on movement frames but to compare all represented positions. While master frames often take a movement-centered perspective (Carroll & Ratner, Citation1996), approaching generic frames as based on interpretative repertoires offers a comprehensive manner of discerning distinct evaluative standards or normative perspectives (Baden & Springer, Citation2017). To identify central logics of evaluation that are tied to distinct worldviews, Baden and Springer (Citation2017) follow Boltanski and Thévenot’s (1999, Citation2006) theory of justification that proposes seven distinct rationales that actors apply to justify their arguments in public discourses (Lafaye et al., Citation1993). These seven rationales are civic, economic, ecological, domestic, functional, popular, and inspired (Baden & Springer, Citation2017; Boltanski & Thévenot, Citation2006). Each of these rationales – or common worlds – is tied to a social realm, presumes a specific definition of the common good, and applies certain modes of evaluation. Common worlds can thus be understood as normative principles that are inherent to specific institutional environments (Patriotta et al., Citation2011). The civic world, for instance, relates to the political environment that represents values, such as legal, official, governance, authority, or civil rights. The common good from this perspective is thriving toward a functioning collective as opposed to any individualistic goals (Boltanski & Thévenot, Citation2006, pp. 185–193). The ecological world, in contrast, focusses on biospheric or self-transcendent values and sustainability. The main aim is to preserve healthy ecosystems and entails a long-term orientation (Lafaye et al., Citation1993).

Actors are considered to be guided by their institutional environment in how they justify their viewpoints in public controversies and, accordingly, might disagree about the normative principles that should be applied (Baden & Springer, Citation2017; Patriotta et al., Citation2011). An ENGO may, for instance, be expected to present arguments that draw on the ecological world while judges would respond using a civic rationale. Politicians to this end form a special group of actors as they represent different societal interests within the political (hence civic) system and may thus combine rationales fitting to their party line with civic justifications (Patriotta et al., Citation2011).

Issue-specific frames: problems, solutions, and responsibilities

Following theories on social movement frames, the discursive success of litigation as public campaigning tool largely dependents on the extent to which a movement can make use of litigation as an issue to define problems, propose solutions, and assign responsibilities (Benford & Snow, Citation2000; Snow & Benford, Citation1988). These elements are reflected by the distinction of diagnostic and prognostic frames which is often used to analyze movement success (Jacobs et al., Citation2021; Snow et al., Citation2019). Studying diagnostic frames in the context of CCL, can help to understand to what extent an initiating ENGO is able to overcome indexing (Bennett, Citation2016) and capitalize on the public attention for a court case to define the nature of the underlying problem, such as inadequate national climate policies or insufficient plans of a cooperation to reduce emission levels. Moreover, diagnostic frames include communicated responsibilities, such as governmental or corporate responsibilities for climate change mitigation. Prognostic frames, in contrast, reveal which solutions are proposed including specific actions as well as references to actors held responsible for solving the problem (Jacobs et al., Citation2021).

CCL discourses as legitimacy test

Following a neo-institutional approach, Patriotta et al. (Citation2011) have conceptualized public controversies as legitimacy tests. A controversy emerges when the social status quo is disrupted leading to the questioning of the legitimacy of previously either unquestioned or agreed upon assumptions. Consequently, a controversy unfolds during which various actors negotiate the diagnostic and prognostic aspects of the problem (Jacobs et al., Citation2021) and mobilize different modes of justification (Baden & Springer, Citation2017). Legitimacy is reinstated once actors reach agreements on adequate definitions and solutions (Hein & Chaudhri, Citation2019). Negotiations may result in a new equilibrium and legitimacy with a dominant mode of justification (Patriotta et al., Citation2011). Alternatively, a compromise may be reached by tolerating different modes of justification. Such a composite arrangement is more fragile, and a new controversy may be triggered more easily (Boltanski & Thévenot, Citation2006).

In sum, the present study discerns two levels of frames that actors utilize in public discourses. The issue-specific level discerns diagnostic frames that include a problem definition and/or diagnostic responsibility attributions and prognostic frames that include solutions and/or prognostic responsibility attributions. The generic level captures the underlying normative rationales that are applied to justify causes and solutions of a problem and related responsibilities. These levels thus build on one another. Hence, we can assume that the generic modes of justification render certain diagnostic and prognostic frames more plausible. Building on the assumption that CCL may help to overcome indexing, this framework is used to study the following research question:

To what extent are ENGOs successful in framing public discussions about climate change litigation?

Research context: CCL in the Netherlands

As a response to high national GHG emissions and lacking political actions, the Dutch environmental foundation Urgenda sued the government in 2013 for violating its responsibility to protect citizens from negative consequences of climate change. While Urgenda demanded a reduction of emissions by 40% until 2020, in 2015 the court ruled that emissions had to be reduced by 25% until 2020. The Dutch Supreme Court confirmed this verdict in 2019.

In 2016, FoE sued the Dutch government aiming for stricter measures against air pollution. Similar to the Urgenda case, the indictment held the government responsible for protecting citizens from detrimental effects of air pollution. FoE won an emergency proceeding in 2017 and the government was ordered to ensure that EU standards are met. In the same year, however, the court ruled against FoE in the regular case in which FoE demanded even higher standards. FoE appealed this ruling unsuccessfully.

Finally, FoE initiated a case against the Dutch Royal Shell in 2018. Supported by other environmental organizations and about 17,000 citizens as co-plaintiffs, this lawsuit aimed at holding the company responsible for the negative consequences of their GHG emissions and enforcing emission reduction. In 2021, the court ruled that Shell had to reduce its emissions by 45% by 2030. In contrast to the air pollution case, both the Urgenda and the Shell case were considered landmark rulings receiving international attention and inspiring other CCL.

Method

A manual quantitative and qualitative content analysis of the media coverage about the three CCL cases was conducted. Articles published in five large national newspapers were collected via Nexis Uni for the period from October 2012 to September 2019. The newspapers ranged from politically left leaning, to politically neutral and more conservative (Trouw, de Volkskrant, Algemeen Dagblad/AD, NCR, De Telegraaf). The time period covered key phases of each litigation case, that is, the initial public announcements by the ENGOs to initiate a lawsuit, the indictment, court hearings, and judgments. Note, however, that at the end of data collection the cases were in different stages: Urgenda vs state was still awaiting the final judgement by the supreme court. For FoE vs state the final judgement had been made and for FoE vs Shell only the initial court verdict was included. For each case the article selection focused on four weeks prior and past major events. A keyword search including the organizations and several synonyms for court and lawsuit (Table 1A, supplemental material) resulted in a sample of 1,011 articles (Urgenda vs state: 585; FoE vs state: 149; FoE vs Shell: 277).

The analytic approach matched the distinct role and interrelation of generic and issue-specific frames. Modes of justification as generic frames were deductively coded with a quantitative content analysis. While diagnostic and prognostic frames were included as categories in this step, these were then further analyzed qualitatively to inductively derive the most relevant issue-specific frames that fall within the different modes of justification.

Codebook, coding units, and measures

Based on an initial qualitative assessment of a sub-sample of the coverage of key events per case, a codebook was developed for the manual coding process. Issue relevance – the presence of an explicit link to one of the three court cases – was coded on the article level. The main coding units were actor claims within articles. A claim represented a statement of one or several sentences displaying opinions or actions related to litigation by one or several actors. The codebook included categories for actors and the two frame levels (see Table 2A, supplemental material, for an overview). For all actor and frame categories multiple categories could be coded per claim.

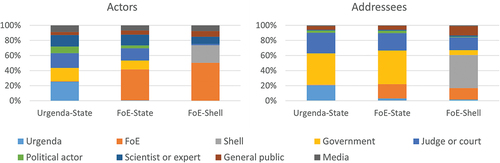

Actors and addressees

All claims were assigned to actors. Secondary actors mentioned within a claim were coded as addressees. In addition to specific actors involved in the litigation cases (e.g., Urgenda, FoE, Shell) more generic codes grouped distinct types of actors and addressees, including: other NGOs, corporations, political actors, judges, scientists and other experts, the general public, and media actors.

Frames

For the generic level, the modes of justifications applied by one or several actors were coded. The coding of the seven distinct rationales (ecological, civic, domestic, economic, functional, popular, inspired) was based on semantic markers established by previous research (Boltanski & Thévenot, Citation2006; Patriotta et al., Citation2011). During the initial qualitative assessment, markers that were specifically linked to CCL and the three cases were added. On the issue-specific level, a claim could include diagnostic and/or prognostic elements. A diagnostic frame was coded if actors addressed the character of a problem and/or related responsibilities. A prognostic frame was coded if actors proposed solutions to a problem, possibly linking to specific actions and responsibilities.

Coding procedure and analysis

The coding was conducted in Atlas.ti. First, issue relevance was coded. Next, claims were identified and coded for relevant articles. Formal characteristics of the articles were downloaded from Nexis Uni and later linked to the data. Three coders were trained, including several test rounds during which additional explanations and examples were added to the codebook. A pretest was conducted in three steps. First, a sub-sample of 30 articles was used to test the coding of article relevance (Krippendorff’s Alpha: .78). Second, 30 relevant articles were used to test claim identification (Krippendorff’s Alpha: .73). Third, 72 claims were identified in these 30 articles and used to test the remaining substantial variables. The resulting intercoder reliability was acceptable for the most frequently occurring actor and frame types ranging from .75 to 1.00. Two actor categories (other NGOs, other companies) that appeared rarely had lower scores and were excluded from the analysis.

After the manual coding, the analysis proceeded in two steps. First, the quantitative data were analyzed including a comparison of key actors and their frames across the three cases. Second, focusing on responsibility attributions and solutions, claims that included the most frequently observed combinations of actors and frame dimensions were analyzed qualitatively to further specify the nature of the issue-specific frames. To this end, open coding was conducted during which diagnostic and prognostic elements were labeled. Intermediate discussions ensured the consistency of coding across time and cases. During a second round of coding, these labels were summarized in a table for each case (Table 3A-5A, supplemental material) and then further condensed resulting in the overview presented in .

Table 1. Main issue-specific diagnostic and prognostic frames used by ENGOs and defendants.

Results

Key actors

The coding of relevance resulted in a final sample of 510 articles (Urgenda vs state: 337; FoE vs state: 76; FoE vs Shell: 97) and a total of 1,394 actor claims that were coded. The media coverage appeared relatively focused on the main actors, that is, the initiating ENGOs, defendants, and courts or judges (). Being the most prominent active actors, the viewpoints of Urgenda and FoE were most prominent. Urgenda’s appearance as actor (24% of case-related claims) was lower compared to FoE (air pollution: 39%, Shell: 51%). With 59% (Government in Urgenda case) and 65% (Shell), the defendants received the most prominent role as addressees. Shell was the most actively engaged defendant (23%). The government displayed a slightly more active role in the Urgenda case (17%) compared to the second case led by FoE (11% of all claims). Courts and judges ranked third as key actors (Urgenda case: 19%, air pollution: 15%, Shell: 2%) and as addressees (Urgenda: 39%, air pollution: 33%, Shell: 25%). The general public, often referred to as co-plaintiffs or supporters of the lawsuits, was with 18% addressed most often in the Shell case. Finally, scientists and experts received similar levels of attention as actors in all three cases ranging from 10–15%.

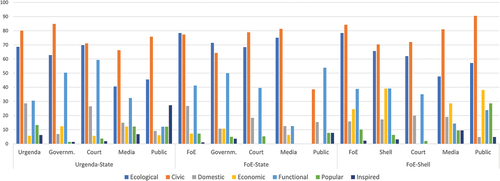

Generic frames: modes of justifications

Across cases and actors, civic and ecological arguments were consistently most prominent and, hence, represented the most central common worlds for all three debates (). Naturally, the context of lawsuits evoked civic considerations while the climate and pollution context elicited ecological rationales. For example, the most relevant diagnostic frame brought forward by Urgenda focused on citizen rights by arguing that inadequate mitigation policies violate constitutional and human rights of current and future citizens. Collective welfare thus presented a key value for the evaluation of governmental and corporate action. Urgency was emphasized by referring to an inevitable increase of crises and conflict when climate change progresses which included ecological and civic aspects. Other common worlds frequently referred to in the debates bringing in, most prominently, domestic, functional, and economic considerations. References to public support resulted in a substantial presence of the popular frame. The inspired frame was least prominent.

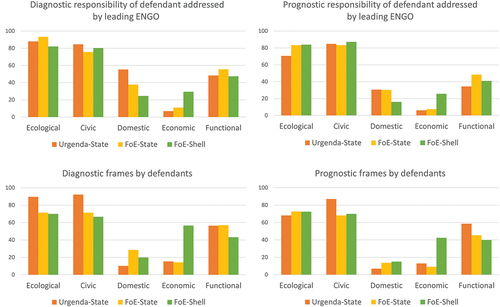

Issue-specific responsibility claims

To zoom in on how responsibilities were discussed, I compared the issue-specific frames used by the plaintiffs when they addressed the defendants and by the defendants in their responses. provides an overview of the proportions of the five main modes of justification per case, actor, and issue-specific frame type. Across cases, the claims made by both the plaintiffs and defendants were strongly oriented on the main ecological and civic arguments brought forward in court and responses to those. Noticeable differences, however, occurred in how additional modes of justifications were used and in the arguments on the issue-specific level. While the quantitative analysis did not reveal substantial changes of time, the qualitative analysis revealed a number of changes in the main arguments on the issue-specific level ().

Figure 3. Modes of justification per case, actor, and type of issue-specific frame (in percent, N = 1,394 claims).

Urgenda vs state

As described above, the prevailing ecological and civic claims reflected the main arguments of Urgenda, diagnostically, referring to inadequate governmental action and, prognostically, demanding governmental responsibility and action. The proposed main course of action thereby evoked a functional justification by proposing specific levels of emission reduction, i.e., a reduction of 40% of national GHG emissions until 2020. In addition, Urgenda mobilized domestic arguments by emphasizing the important role of the country in acting on climate change or the consequences for Dutch citizens:

‘History teaches us that sometimes citizens need protection against their own government, he [Roger Cox, lawyer Urgenda] says. […] The scientific consensus is that the Netherlands as well will end up in a scenario of worldwide food scarcity and higher chances of severe floods’.

While the government responded evoking almost equal levels of ecological, civic, and functional arguments, governmental actors avoided domestic rationales but used functional and economic considerations more frequently. The government emphasized their limited capacity to act, frequently drawing on economic reasons such as high costs. While there was, for example, an increasing support for closing coal-fired power stations in the parliament, the government kept on repelling this option:

‘Especially, VVDer Kamp [minister of economic affairs] thinks that closing new power stations is destruction of capital. […] It is obvious that the energy company will hand in a billions claim in case of a forced closing’.

Moreover, the government combined economic and functional considerations to emphasize the limited impact of national measures on a global level:

‘[…] then the attorney of the state argued that the sky-high costs are not in proportion to the gains, namely, a decrease in temperature that is so small that it can only be perceived on a model basis (0.000045 fewer degrees of warming)’.

Hence, these main counter arguments were strongly aligned to market-liberal political views of the government at the time. In addition, a more general civic argument was made objecting the legitimacy of climate litigation: ‘Member of parliament Remco Dijkstra: “The judge must not sit on the chair of politics”’ (AD, 08/2015).

FoE vs state

Comparable to the Urgenda case, FoE appealed to the ecological and the civic world by claiming that the government holds a responsibility to protect its citizens from harmful consequences of air pollution (diagnostic) and must act to recreate a healthier environment (prognostic). Their arguments, however, included a slightly stronger emphasis on functional aspects, mainly due to diagnostic descriptions of air pollution levels and prognostic references to health standards of the EU or the World Health Organization. Additionally, domestic arguments formed an important aspect of the plaintiff’s rationale: ‘Thousands of Dutch people die prematurely, and ten-thousands get sick because of the polluted air they breeze’ (Trouw, 8/2016).

The government, again, responded with ecological, civic, and functional arguments. Unlike in the Urgenda case, also domestic arguments were part of the government’s response (here linked to an economic and popular rationale):

‘The Netherlands cannot immediately comply with the directions on clean air. Especially, in big cities this would lead to draconic measures with severe consequences for the economy for which there is no support among the population’.

This example shows how representatives of the government declared their responsibility for clean air as subordinated to economic considerations and the public interest. This lack of governmental responsibility was used by multiple actors including FoE, experts, and political actors to legitimate the court case:

‘Stepping to the Dutch judge may help to give a feeling of urgency to the government so that, to begin with, a polluting measure such as the increase of maximum speed to 130 kilometers goes off the table’.

The judgement in December 2017 confirmed the government’s responsibility to reduce air pollution but stated that the current national plan is sufficient. This was used as a civic argument by the government to counter the legitimacy of the case.

FoE vs Shell

In the third case, Shell was held responsible by FoE diagnostically by playing an important role in causing anthropogenic climate change. Consequently, FoE demanded from the court to render the company legally responsible to actively contribute to climate change mitigation by lowering their emissions by 45% until 2030 compared to 2010 and achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. Compared to the two cases against the government, functional and economic considerations played a more important role in the plaintiff’s arguments, in addition to domestic aspects.

Shell defended its position by applying the four most prevailing types of justification (ecological, civic, economic functional) but fewer domestic arguments. While FoE referred to the powerful position of the Dutch-based company, Shell emphasized its limited power to change dynamics of demand and supply on the global market, also referring to the tragedy of the commons:

“[…] the case lacks a legal basis because Shell did not sign the Paris Agreement. For this is an agreement between countries. […] If Shell restricts its production, ‘another company steps into the breach’“.

FoE emphasized the diagnostic responsibility of Shell stating that the company actively suppressed information for a long time and influenced public and political opinion in favor of the company’s business interests. In defense, Shell emphasized its ongoing efforts toward a more sustainable business. FoE, however, countered that ‘Shell mainly tries to cut a dash with distant future promises’ (Trouw, 02/2021).

Again, references to the general public occurred frequently fulfilling a different function for the plaintiff and defendant. FoE often referred to the more than 17,000 co-plaintiffs lending legitimacy to the case. Shell – considerably less often – attempted to marginalize this public support by stressing their overall positive reputation or labeling supporters as small minority. Moreover, FoE gave the responsibility of Shell a global dimension by expanding it to citizens world-wide:

‘Milieudefensie tried to demonstrate that Shell as large energy enterprise carries at least equal responsibility for dangerous climate change as nation-states. Shell […] acts therefore unjust if it does not protect citizens world-wide against this danger’.

Shell, in contrast, emphasized the societal responsibility of the company by framing their oil business as response to consumer and market demands. Herewith, Shell transferred the responsibility for action and change to consumers and to governments rendering climate change thus primarily a civic and political problem. The company’s societal responsibility was further supported by legal and scientific arguments stating that the company complies to existing laws or climate scientists agreeing that society still depends on fossil fuels.

Issue-specific solution claims

In addition to discussing diagnostic and prognostic aspects of responsibility, the prognostic frames revealed how solutions were proposed and debated. The following sections discuss interrelations of responsibility and solution discourses for each case.

Urgenda vs state

The most striking change on the issue-specific level was identified here. The discussion in parallel to the court case remained on a relatively abstract level focusing on general goals and responsibilities, such as emission reduction or protecting citizens. Only after the initial verdict, Urgenda jointly with 700 organizations published a list of 40, and later 54, measures that could be taken by the government to effectively reduce national emission levels (Urgenda, Citation2020). This list appeared on the political and media agenda when the government and parliament debated on how to reach the target that was set by the so-called Urgenda judgment. Thus, responding to both the judgement and Urgenda’s specific recommendations, the prognostic, civic arguments of the government changed from criticizing litigation to discussing solutions (see ): ‘According to premier Rutte, a sturdy package of measures is necessary’ (Telegraaf, 1/2019).

FoE vs state

FoE brought specific solutions into the debate at an early point, which explains the higher share of functional arguments. They demanded from the government to develop an air quality plan and made suggestions like lowering the maximum speed on highways. This discussion at times included rather technical aspects:

“So is air pollution in the Netherlands not only measured but also calculated. And this system is not very precise. Knol [FoE]: ‘To be sure of clean air the government needs to take measures to arrive well below the yearly norm for clean air’“.

Other actors, such as journalists and experts joined the debate about suitable solutions to fulfill the norms: ‘To get the air quality straight quickly, rigorous measures are needed. Closing city highways or shutting down intensive cattle farming’ (Trouw, 24 April 2017). While there was no disagreement about the main litigation aim of reducing air pollution, the proposed measures evoked critical responses from various actors who mobilized a variety of rationales to justify their positions like emphasizing that ‘the man on the street will have to pay’ (Telegraaf, 4/2018).

In contrast to the Urgenda case, thus, the main target, responsibilities, and solutions were discussed in parallel. This led to a less focused debate, specifically, on solutions because it was still not settled to what extent the state could, in fact, be held responsible and which extent of action was needed. The solutions discussion became even less constructive when the court judgement undermined the urgency for stricter measures: ‘Different from the short procedure the judge now says: the government has a plan, its implementation may take a while’ (Trouw, 12/2017).

FoE vs Shell

While FoE strongly focused on the responsibility aspects in the case against Shell, specific solutions were primarily brought up by the defendant to emphasize that the company cannot be held responsible for climate mitigation:

‘If Milieudefensie does not agree with the CO2 emissions as consequence of selling gas at petrol stations of Shell, the environmental organization should knock on the government’s door. It is the legislator within whose framework Shell is allowed to pomp and trade, argues Shell’.

A position frequently represented by Shell was that the company stands behind the Paris Agreement and specific solutions like transforming the energy system. However, due to its limited influence and scope of action and principles of the free-market system, Shell cannot be held accountable or forced to act without corresponding legislation and changes of consumer demands. Accordingly, Shell was very reluctant in responding to the courts verdict in May 2021 which demanded Shell to reduce its emissions in line with the indictment.

Discussion and conclusions

This study considered climate change litigation against national governments and corporations as a public campaigning tool that can intensify public controversies about mitigation-related responsibilities and solutions. By contributing to the normative and moral dimension of climate change discourses, the discourses about litigation cases represented in the media can be understood as indirect influences of CCL (Peel & Osofsky, Citation2013). Discerning modes of justifications as generic frames (Baden & Springer, Citation2017; Patriotta et al., Citation2011) and diagnostic and prognostic issue-specific frames (Jacobs et al., Citation2021; Snow et al., Citation2019), I have suggested that the discursive success of litigation is influenced by the resonance that frames on both levels communicated by ENGOs receive (Boltanski & Thévenot, Citation2006; Hein & Chaudhri, Citation2019). Comparing actor claims represented in the media coverage about three CCL cases in the Netherlands revealed that the initiating ENGOs were to a large extent successful in setting the overall tone of the discourse by seemingly influencing the main modes of justification, hence, the generic frames, applied across key actors. With a strong focus on civic and ecological arguments, the ENGOs introduced normative arguments that were hard to object by the defendants. While previous research has identified dynamics of frame negotiations resulting in alignment across actors (Patriotta et al., Citation2011; van der Meer et al., Citation2014), the studied discourses on CCL showed a strong and consistent dominance of movement frames on the generic level.

Examining the issue-specific arguments revealed that the defendants not only responded largely in agreement with the modes of justifications mobilized by the ENGOs, but that their arguments also presented direct responses as opposed to bringing in new angles into the debate. Looking at the interrelation between the generic and issue-specific level, in all three cases the defendants have connected the initial ecological and civic arguments with economic and functional considerations to reject responsibility. Either by referring to disproportionate costs or detrimental consequences for the economy (government) or the dominance of market mechanisms (Shell), market-liberal arguments were applied to argue that taking up responsibility was not feasible. In addition, arguments about the limited impact of an individual country or company on a global scale made use of functional considerations in the sense that they included technical and numerical assessments. By shifting the debate to different modes of justification, the defendants and other actors created disagreement on a higher level, that is, on the question of what common worth (e.g., public health or welfare vs. economic welfare or effectiveness) should be used as overarching aim in the debate (Baden & Springer, Citation2017; Patriotta et al., Citation2011). However, given that the main focus remained on ecological and civic rationales, these issue-specific counterarguments were not successful in changing the main focus of the discourse. Hence, the ENGOs continued owning the issue throughout the discourses (Kleinnijenhuis & Walter, Citation2014) and, hence, indexing was not a prominent mechanism for these litigation debates (Schmid-Petri et al., Citation2017; Tschötschel et al., Citation2020).

While these findings indicate that CCL discourses can stimulate public attributions of treatment responsibility (Post et al., Citation2019), the interrelations between responsibility discourses and solutions discourses seem to matter as underlined by the most striking temporal changes identified in the analysis (see ). In the Urgenda case, the liberal government initially defended its view of limited possibilities to take further and more rigorous action to reduce emissions more drastically, for example, referring to high costs of closing coal-fired power stations. However, only after the first verdict Urgenda engaged in the solutions discourse with the publication of possible measures. An additional report by the Dutch audit office about possible responses to the Urgenda judgement, further pushed the government to initiate adequate policies and regulations. Similarly, in the Shell case FoE refrained from specific recommendations about how the company should adjust its business. The public discourse on the air pollution case, in contrast, was more strongly oriented toward possible solutions and involved consequences from the start including possible constraints and costs for citizens or industry. Hence, economic and functional justifications dominated these critical voices, possibly distracting from ecological and civic responsibility questions. The three cases studied here thus indicate that it might be an effective strategy for ENGOs to separate the two discourses. Focusing on responsibilities first and postponing a more detailed discussion of solutions until a sufficient level of public agreement has been reached on the question of responsibility, ideally supported by a court verdict, may help to increase public legitimacy of both responsibilities and solutions. While this is a relevant insight given the general shift of climate change discourses away from problem-centric to solution-focused discussions (Post et al., Citation2019; Tschötschel et al., Citation2020), further research is needed to assess if such a mechanism applies in other contexts.

Notably, research has been criticized for focusing too much on high-profile cases that are successful in court and draw national and international attention while the lion’s share of CCL are routine cases of a smaller scope in addition to a growing number of cases in the Global South (Setzer & Byrnes, Citation2019). Indeed, a major difference between the three CCL cases analyzed here can be attributed to the success yielded in court with judgements in favor of the plaintiff in the cases of Urgenda and Shell versus a merely partial success in the initial short procedure in the air pollution case. The findings suggest that a clear court decision on climate responsibilities reduces public controversy on this matter and gives room for a more focused debate on possible solutions. Hence, court success is a major factor for the effectiveness of CCL as a public campaigning tool. In addition to possible detrimental effects of unsuccessful cases, such as hindering policy reforms or supporting the exploitation of natural resources (Setzer & Vanhala, Citation2019), detrimental indirect consequences can be added as these seem to be less successful in garnering public legitimacy.

Considering the role of CCL within the recent spectrum of climate change activism, it can be argued that the different form of engagement requested from citizens by supporting CCL as co-plaintiff may help to attract different target groups compared to, for instance, the movement of younger people or public civil disobedience (de Moor et al., Citation2021). While this can contribute to broader societal mobilization, the frequent references to public support found in this study show that this form of individual activism, typically done in the private sphere at a home computer, translates into publicly visible engagement. Moreover, while addressing concrete actors, especially national governments, is common in recent forms of activism, CCL can be considered to play a decisive role in pushing governments and corporations toward specific climate action as opposed to solely emphasizing their responsibility to act (de Moor et al., Citation2021; Evensen, Citation2019). CCL thus ads to the diversity of formats used in public climate activism. In addition to direct effects yielded via court judgements, this study shows that litigation creates visibility and resonance for the climate movement via media discourses with a specific focus on solutions and related responsibilities.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (368.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2023.2270919.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anke Wonneberger

Anke Wonneberger is an associate professor in Corporate Communication at the Amsterdam School of Communication Research (ASCoR), University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Her research topics include strategic communication of non-profit organizations and environmental communication with a focus on public discourses about environmental issues.

References

- Baden, C., & Springer, N. (2017). Conceptualizing viewpoint diversity in news discourse. Journalism, 18(2), 176–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884915605028

- Benford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 611–639. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611

- Bennett, W. L. (2016). News: The politics of illusion. University of Chicago Press.

- Boltanski, L., & Thévenot, L. (1999). The sociology of critical capacity. European Journal of Social Theory, 2(3), 359–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/136843199002003010

- Boltanski, L., & Thévenot, L. (2006). On justification: Economies of worth (Vol. 27). Princeton University Press.

- Brüggemann, M., & D’Angelo, P. (2018). Defragmenting news framing research: Reconciling generic and issue-specific frames. In P. D’Angelo (Ed.), Doing news framing analysis II (pp. 90–111). Routledge .

- Brüggemann, M., & Engesser, S. (2017). Beyond false balance: How interpretive journalism shapes media coverage of climate change. Global Environmental Change, 42, 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.11.004

- Carroll, W. K., & Ratner, R. S. (1996). Master framing and cross-movement networking in contemporary social movements. The Sociological Quarterly, 37(4), 601–625. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.1996.tb01755.x

- Chewinski, M., & Corrigall-Brown, C. (2020). Channeling advocacy? Assessing how funding source shapes the strategies of environmental organizations. Social Movement Studies, 19(2), 222–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2019.1631153

- D’Angelo, P. (2018). Doing news framing analysis II: Empirical and theoretical perspectives. Routledge.

- de Moor, J., de Vydt, M., Uba, K., & Wahlström, M. (2021). New kids on the block: Taking stock of the recent cycle of climate activism. Social Movement Studies, 20(5), 619–625. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2020.1836617

- Evensen, D. (2019). The rhetorical limitations of the #FridaysForFuture movement. Nature Climate Change, 9(6), 428–430. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0481-1

- Gamson, W., & Wolfsfeld, G. (1993). Movements and media as interacting systems. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 528(1), 114–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716293528001009

- Hein, J. E., & Chaudhri, V. (2019). Delegitimizing the enemy: Framing, tactical innovation, and blunders in the battle for the Arctic. Social Movement Studies, 18(2), 171–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2018.1555750

- Hertog, J. K., & McLeod, D. M. (1995). Anarchists wreak havoc in downtown Minneapolis: A multi-level study of media coverage of radical protest. Journalism and Mass Communication Monographs,151, 1–48.

- Hilgartner, S., & Bosk, C. L. (1988). The rise and fall of social problems: A public arenas model. American Journal of Sociology, 94(1), 53–78. https://doi.org/10.1086/228951

- Jacobs, S. H. J., Wonneberger, A., & Hellsten, I. (2021). Evaluating social countermarketing success: Resonance of framing strategies in online food quality debates. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 26(1), 221–238. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-01-2020-0011

- Kim, K., & Shahin, S. (2020). Ideological parallelism: Toward a transnational understanding of the protest paradigm. Social Movement Studies, 19(4), 391–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2019.1681956

- Kleinnijenhuis, J., & Walter, A. S. (2014). News, discussion, and associative issue ownership: Instability at the micro level versus stability at the macro level. The International Journal of Press/politics, 19(2), 226–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161213520043

- Lafaye, C., Thévenot, L., & Thevenot, L. (1993). Une justification écologique? Conflits dans l’aménagement de la nature. Revue Française de Sociologie, 34(4), 495–524. https://doi.org/10.2307/3321928

- Lueck, J., Wozniak, A., & Wessler, H. (2016). Networks of coproduction: How journalists and environmental NGOs create common interpretations of the UN climate change conferences. The International Journal of Press/politics, 21(1), 25–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161215612204

- McCormick, S., Glicksman, R. L., Simmens, S. J., Paddock, L., Kim, D., & Whited, B. (2018). Strategies in and outcomes of climate change litigation in the United States. Nature Climate Change, 8(9), 829–833. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0240-8

- Patriotta, G., Gond, J. P., & Schultz, F. (2011). Maintaining legitimacy: Controversies, orders of worth, and public justifications. Journal of Management Studies, 48(8), 1804–1836. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00990.x

- Peel, J., & Osofsky, H. M. (2013). Climate change litigation’s regulatory pathways: A comparative analysis of the United States and Australia. Law & Policy, 35(3), 150–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/lapo.12003

- Post, S., Kleinen von Königslöw, K., & Schäfer, M. S. (2019). Between guilt and obligation: Debating the responsibility for climate change and climate politics in the media. Environmental Communication, 13(6), 723–739. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2018.1446037

- Rauch, J., Chitrapu, S., Eastman, S. T., Evans, J. C., Paine, C., & Mwesige, P. (2007). From Seattle 1999 to New York 2004: A Longitudinal analysis of journalistic framing of the movement for Democratic Globalization. Social Movement Studies, 6(2), 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742830701497244

- Rice, R. E., Gustafson, A., & Hoffman, Z. (2018). Frequent but accurate: A closer look at uncertainty and opinion divergence in climate change print news. Environmental Communication, 12(3), 301–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2018.1430046

- Schmid-Petri, H., Adam, S., Schmucki, I., & Häussler, T. (2017). A changing climate of skepticism: The factors shaping climate change coverage in the US press. Public Understanding of Science, 26(4), 498–513. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662515612276

- Setzer, J., & Byrnes, R. (2019). Global trends in climate change litigation: 2019 snapshot. Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment. https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/publication/global-trends-in-climate-change-litigation-2019-snapshot/

- Setzer, J., & Vanhala, L. C. (2019). Climate change litigation: A review of research on courts and litigants in climate governance. WIREs Climate Change, 10(3), e580. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.580

- Shoemaker, P. J., & Reese, S. D. (2013). Mediating the message in the 21st century: A media sociology perspective. Routledge.

- Smith, M. (2004). Questioning heteronormativity: Lesbian and gay challenges to education practice in British Columbia, Canada. Social Movement Studies, 3(2), 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/1474283042000266092

- Snow, D., & Benford, R. (1988). Ideology, frame resonance, and participant mobilization. International Social Movement Research, 1(1), 197–219.

- Snow, D. A., Vliegenthart, R., & Ketelaars, P. (2019). In Snow, D. A., Soule, S. A., Kriesi, H., McCammon, H. J. (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Social Movements (2nd ed., pp. 392–410). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119168577.ch22.

- Tewksbury, D., & Scheufele, D. A. (2009). News framing theory and research. In Bryant, J., Oliver, M. B. Media effects. Advances in theory and research (pp. 17–33). Routledge.

- Tschötschel, R., Schuck, A., & Wonneberger, A. (2020). Patterns of controversy and consensus in German, Canadian, and US online news on climate change. Global Environmental Change, 60, 101957. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.101957

- Urgenda.(2020). 54 puntenplan: naar 25% CO2 reductie in 2020 [54 steps plan: toward 25% CO2 reduction in 2020]. https://www.urgenda.nl/themas/klimaat-en-energie/40-puntenplan/

- van der Meer, T. G. L. A., Verhoeven, P., Beentjes, H., & Vliegenthart, R. (2014). When frames align: The interplay between PR, news media, and the public in times of crisis. Public Relations Review, 40(5), 751–761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2014.07.008

- Vliegenthart, R., & Walgrave, S. (2012). The interdependency of mass media and social movements. In Semetko, H. A., Scammell, M. (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of political communication (pp. 387–398). Sage Publications.

- Walter, D., & Ophir, Y. (2019). News frame analysis: An inductive mixed-method computational approach. Communication Methods and Measures, 13(4), 248–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2019.1639145

- Wonneberger, A., & Vliegenthart, R. (2021). Agenda-setting effects of climate change litigation: Interrelations across issue levels, media, and politics in the case of urgenda against the Dutch government. Environmental Communication, 15(5), 699–714. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2021.1889633