ABSTRACT

This article analyses the representation of the climate crisis and urban imaginaries in post-2011 Arabic science fiction (SF), arguing that Arabic SF, and its cross-genre of critical dystopian fiction, intersects with global climate fiction (cli-fi), while maintaining a horizon for hope. It compares two graphic novels written by authors of Egyptian origins, Aḥmad Nājī's Istikhdām al-Ḥayāt (2014; Using Life, 2017) and Ganzeer's English-language The Solar Grid (2016-2020), with two short stories authored by Iraq-born authors, “al-Mutakallim” (“The Worker”) by Ḍiyāʾ Jubaylī; and “Ḥadāʾīq Bābil” (“Gardens of Babylon”) by Ḥasan Blāsim, included in the collection al-ʿIrāq + 100 (2017; Iraq +100, 2016). Through the four works, future apocalyptic urban scenarios are imagined, linked to climate change, city mega-projects, and oil scarcity. Illuminating the unseen violence perpetrated by colonial forces and ruling elites, these visions prefigure the global reach of the climate catastrophe and contribute to understandings of Nixon's “slow violence” and Heise's “eco-cosmopolitanism”.

IntroductionFootnote1

Science fiction (hence SF), and particularly its cross-genre of dystopian fiction, has undergone a boom in Arabic literature in the last decades.Footnote2 Examples abound across the Arab region, not only in literature, but in film, TV series, and comics, from Aḥmad Khālid Tawfīq’s best-selling Yūtūbiyā (2008; Utopia, 2012) to Ibrāhīm Naṣrallāh’s IPAF-winning Ḥarb al-Kalb al-Thāniya (2017, The Second War of the Dogs) to Lārīsā Sansūr’s sci-fi film trilogy (A Space Exodus, 2009; Nation Estate, 2012; In the Future, They Ate from the Finest Porcelain, 2015). Focussing on seminal Arabic works published between 1965 and 1992, Ian Campbell has theorised the historical origins of this turn, arguing that Arabic SF “takes a genre borrowed directly from the West, roots it in the Arabic cultural and literary heritage and creates works that are both recognizably SF and recognizably Arabic literature.”Footnote3 Other scholars, such as Ada Barbaro, author of the first book dedicated to the genre, La Fantascienza nella Letteratura Araba (2013, Science Fiction in Arabic Literature), Jörg Matthias Determann, and Nat Muller have instead demonstrated that this body of Arabic SF takes inspiration from a rich history of SF and fantasy rooted in, and inherent to, the region, and thus “expands Eurowestern SF and changes it.”Footnote4 When it comes to contemporary SF/dystopian novels, Pepe and Guth’s edited volume Arabic Literature in the Posthuman Age (2019) dedicates a section to SF, and most of the chapters in the section show that Arab authors have adopted the dystopian sub-trend to reflect on future outcomes of the current political reality in the Arab region.Footnote5

While this focus on local political events is enriching, it has obscured the fact that these works also engage with other global challenges such as the current climate crisis, designating the threat of highly dangerous, irreversible changes to the global climate. Returning to the examples mentioned above, Naṣrallāh’s Ḥarb al-Kalb al-Thāniya starts with an environmental catastrophe manifesting itself through the shortening of daytime and changes in seasonal patterns, impacting agriculture, and human and non-human populations. This leads to the adoption of cloning technologies, which raises important ethical dilemmas. Likewise, Tawfīq’s Yūtūbiyā portrays the economic and ecological disaster brought by fossil fuel combustion: petroleum has been substituted by a cheaper substitute, “birūyl,” leading to a collapse of the Egyptian economy. Both works alternate dystopian environmental catastrophes and green utopian solutions achieved through genetic engineering and renewable energy.

In recent years, scholars such as Andrew Milner, J.R. Burgmann, and Ursula Heise have argued that climate fiction (hence, cli-fi), a body of narrative works broadly defined by their thematic focus on climate change, is central to much of the dystopian, catastrophic fiction published in European languages in the last two decades.Footnote6 Hence, it should be regarded as a subgenre of SF that intersects with its dystopian and utopian trends.Footnote7 In their 2011 overview of the genre, Adam Trexler and Adeline Johns-Putra suggest that most of this cli-fi originates in North America, Britain, and Australia,Footnote8 though, in a later study, Johns-Putra points to an increasing number published worldwide between 2011 and 2016.Footnote9 In parallel, most literary criticism of the genre focusses on English-language works. Although the Arabic counterparts of cli-fi – “adab taghayyur al-manākh” (lit.: “literature of climate change”),Footnote10 “al-adab al-bīʾī” (lit.: “environmental literature”),Footnote11 or the transliterated “klāymat fikshun”Footnote12 – have appeared sporadically on the cultural press, mostly referring to translated works, the presence of climate change as a theme in contemporary Arabic production, or the relation between (critical) dystopian fiction and climate change in Arabic literature needs further study.

There is broad agreement that the consequences of climate change will be severe and, in some cases, even pose an existential threat in the Middle East region, and that substantial efforts towards mitigation and adaptation are needed.Footnote13 Harmful consequences – such as a long-term drought in Syria – are already visible. Several countries, such as Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), have experienced unprecedented heatwaves, and increasing temperatures may render parts of the region “uninhabitable” by the end of the century.Footnote14 In Egypt, weather fluctuations are negatively affecting agricultural production and contributing to the inflated prices of fruit and vegetables.Footnote15 Also, land use will change due to flooding from the sea level rising, seawater intrusion, and secondary salinization. Water resources may be affected due to global warming and decreases in precipitation.Footnote16

Iraq on the other hand, has been named the fifth-most vulnerable country to climate breakdown, affected by soaring temperatures, insufficient and diminishing rainfall, intensified droughts and water scarcity, frequent sand and dust storms, and flooding. Without preparation and planning, the scale of environmental change is likely to be devastating and may force Iraqis to relocate in order to survive. Climate migration is already a reality in Iraq, but as environmental changes intensify, displacement is likely to increase exponentially.Footnote17

However, despite such warnings, many national and urban agendas in Arab countries are slow to address these issues in any serious or meaningful way. It is true that all Arab governments have ratified the 2015 COP21 Paris Agreement (2021). They have also all endorsed the commitment of the UN-Habitat New Urban Agenda, with its twofold understanding of sustainability, comprised of environmental preservation and social inclusion. However, at the state level, it is hard to find strategies explicitly focusing on sustainability, let alone concrete policies and projects to implement these strategies. The Arab Spring revolutions represented the opportunity for many non-democratic or autocratic regimes to postpone these global, far-reaching ecological concerns and instead focus on restoring order on the ground.Footnote18

In the meantime, Arab authors have not been indifferent to the current environmental crisis. Over the last decades, they have turned to fiction to express their apprehensions about climatic changes and imagine its possible outcomes. Ada Barbaro identifies the novel Jughrāfiyat al-mā’ (2009) by the prolific Yemeni writer ʿAbd al Nāṣir Mujallī, as an early example of ecological SF.Footnote19 Tetz Rooke also identifies the presence of this theme in a number of SF novels, such as Yūtūbiyā by Aḥmad Khālid Tawfīq (2008), Kawkab al-Ghabā’ (2010, The Planet of Stupidity) by Nūḥ al-Aswānī, and al-Iskandarya 2050 by Ṣubḥī Faḥmāwy (2010).Footnote20 Annie Webster has studied the same two short stories from Iraq +100 (Ḍiyāʾ Jubaylī’s “The Worker” and Ḥasan Blāsim’s “The Gardens of Babylon”) through the pre-Islamic poetic tradition of the aṭlāl (which can be translated as “remains” or “ruins”), and argued that they express a state of “solastalgia,” expressive of the existential distress caused by environmental changes.Footnote21

This article initiates a conversation around contemporary Arabic SF as cli-fi by studying four works published in the last decades: the novel Istikhdām al-Ḥayāh (2014; Using Life, 2017) by Egyptian author Aḥmad Nājī, illustrated by Ayman al-Zurqānī; The Solar Grid by Egyptian artist and writer Ganzeer; and the two short stories, “al-Mutakallim” (2017; “The Worker,” 2016) and “Ḥadāʾīq Bābil” (2017; “The Gardens of Babylon,” 2016) written respectively by Iraqi writers Diyāʾ al-Jubaylī and Ḥasan Blāsim. Set in the future and depicting advanced use of science and technology, all constitute works of SF. Their pessimistic visions further mark them as dystopic. In addition, climate change sets the plot in motion in each, marking them as cli-fi.Footnote22 More specifically, they imagine how climatic changes will manifest in cities of the future while offering glimpses into the decadent cities of the present, ranging from Cairo to Baghdad and Basra.

Undoubtedly, the four works also differ in significant ways. Istikhdām al-Ḥayāh, by the US-based Aḥmad Nājī, is a graphic novel, depicting Cairo after the “Tsunami of the desert” (tsunāmī al-ṣaḥrāʾ), a series of earthquakes and a sandstorm that have reduced Egypt and the rest of the world to rubble. The Solar Grid is a graphic novel published in seven instalments (so far) and written in English between 2016 and 2023 by US-based artist Ganzeer. In it, the earth is drowned by a flood, and most of its population is forced to migrate to the Moon and Mars. In contrast, in “Ḥadāʾīq Bābil,” Ḥasan Blāsim imagines a future Baghdad destroyed by desertification and a series of sandstorms that have rendered the Mesopotamian region uninhabitable. In the same collection, “al-Mutakallim” by Diyāʿ Jubaylī describes Basra ruled by a wealthy shaykh following the exhaustion of oil and natural resources in the region. In both, climate crisis is linked to the burning of oil, bringing both within the remit of petrofiction, too.Footnote23

Such bleak urban scenarios have a long tradition in Arabic, rendered all the more relevant as one of the terms used in Arabic to define “dystopia” is “al-madīna al-fāsida” (the corrupted city), as the antonym of “al-madīna al-fāḍila” (the ideal city), used by philosopher al-Fārābī (872–950) to indicate “the perfect state,” or “utopia.”Footnote24 A focus on the “urban” is also timely, reflecting on the urban mega projects initiated by Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and other national governments (such as the New Capital in Egypt, and NEOM in Saudi Arabia) in the last decade. These cities are advertised as sustainable, smart, and green, and presented as ways to attract foreign investment, generate professional opportunities, and instill a worldly lifestyle; but they reflect the authoritarian nature of the governments behind them, as both their planning and financing have excluded citizens from participating, and forcibly removed thousands from their homes, without adequate compensation.Footnote25 Most importantly, the current model of urban expansion in the region points to an economic pattern that is extractive rather than circular. Urban expansion leads to consumption, production, and intensive use of water by the construction sector. It is followed by increased energy demand, in addition to the creation of road networks and accompanying infrastructure. In sum, it is unsustainable and reinforces spatial and environmental inequalities.Footnote26

While previous studies of urban landscapes in literature have focused on the social and political reality of the city,Footnote27 I consider environmental concerns, such as weather transformations, urban planning, pollution, waste disposal, and traffic congestion. My analysis is inspired by what Michael Bennett and David W. Teague theorize as “urban ecocriticism,” shifting from a focus on Romantic ideas of nature to awareness of different, equally valuable, natures, in the city and other humanized environments.Footnote28 In this sense, the article aims at complementing previous ecocritical studies of Arabic literature that have mostly tackled forms of “nature writing” in canonical works of Arabic prose and poetry.Footnote29

Attending to what Erin James calls “a sensitivity to the literary structures and devices that we use to communicate representations of the physical environment to each other via narratives,”Footnote30 the following sections compare literature from Egypt and Iraq to highlight how fiction engages with climate change as a global challenge rooted in specific locations. Adeline Johns-Putra’s “environmental care,”Footnote31 Rob Nixon’s “slow violence,”Footnote32 and Ursula Heise’s “eco-cosmopolitanism”Footnote33 are used to argue that the four authors use dystopian cli-fi to shed light on the unseen violence perpetrated by colonial forces and local ruling elites in their places of origin yet foreshadowing the global reach of the imminent climate catastrophe. The article hypothesizes that these four works participate to different degrees in the global trend of critical dystopia theorized by Baccolini and Moylan in 2003, as they describe “a non-existent society that is worse than contemporary society, but that normally includes one utopian enclave or holds out hope that the dystopia can be overcome and replaced by a utopia.”Footnote34 More specifically, Moylan and Baccolini argue that what maintains the utopian impulse, or critical perspective, within the work is its resistance to closure, which may be achieved formally by an intensification of the practice of genre-blurring, by open endings, or by inscribing space with political opposition.Footnote35 Combing critical dystopia with environmental themes and urban scenarios, I interpret these works as cli-fi, pointing the reader to the imminent climatic challenge and yet creating social hope within the text.

Egypt: environmental collapse between the desert and Nile

“Which future? We are in it now, and it bores me to death,” affirms Bassām, the middle-aged protagonist narrator of Nājī’s Istikhdām al-Hāyāh, who is one of the few survivors of the nakba , a term originally connected to the 1948 Palestinian catastrophe and here reimagined as an environmental disaster that destroys Egypt and the rest of the world in the 2050s, causing an enormous loss of human lives and financial goods, along with an eternally unfulfilled sense of belonging among the citizens that reinhabit the land.Footnote36 Initially, the cause of the apocalypse remains unclear. Alluding to Islamic eschatology, according to which natural catastrophes could be interpreted as signs of the coming of the Day of Judgment (yawm al-qiyāmah),Footnote37 the narrator describes it as the effect of “Divine rage. A curse from the heavens. The Lord had decided to give the Egyptians a sequel to the Seven Plagues.”Footnote38 Later, it is revealed that climate change was the main cause, set in motion by the secret “Society of Urbanists,” mostly composed of foreigners, who poison the Nile with doomsday humanoid-fish to divert the river from its trajectory, and make space for a futuristic capital city.

Before Cairo is destroyed and relocated, the book follows the everyday life of Bassām in the immediate aftermath of the 2011 uprisings, while he is hired by the Society to produce a documentary about the city. In these sections, the urban challenges of living in Cairo occupy a major space in the narration. The inhabitants of post-2011 Cairo must tolerate unbearable weather conditions and urban deterioration, alongside social and political problems. The novel describes characters subjected to hot and humid temperatures to the point that they become drenched in sweat and struggle to breathe. The air is so hot that Bassām almost burns his skin while sitting in a minivan in traffic. Piling garbage is another issue. Bassām describes “the nauseating stench of waste from dump trucks and pig farms.”Footnote39 Traffic is also a constant reality, or “the normal state of things.”Footnote40 At one point, after being stuck in traffic for hours, Bassām comments: “Welcome to the hell that is Cairo, where life is one long wait, and the smell of trash and assorted animal dung hangs about all the time and everywhere.”Footnote41 The air, too, is rotten, causing incurable sickness in certain districts, where it is too hazardous to build. The urban deterioration, of traffic, heat, and waste, is little exaggeration of Cairo’s contemporary reality, and recurs in other futuristic Egyptian fiction.Footnote42 However, in Istikhdām al-Ḥayāh, it also anticipates the inevitable catastrophe brought by climate change. These signs of deterioration prompt the Society to demolish Cairo and rebuild the architecturally more efficient “6th October” city as the new capital, whose name recalls one of the Egyptian satellite cities currently located in the Egyptian desert.

This imagined future capital also lies in the middle of the desert, a clear allusion to the new Egyptian mega project launched in 2015. Reproducing a trope from global dystopic fiction, Nājī depicts the future capital as ruled by a totalitarian, capitalist society, composed mainly of foreign corporations. Citizens have electronic chips implanted in their bodies that keep them traceable and connected to the rest of the world. Environmental problems are solved with the help of science and technology: machines clean pollution from the air; unsanitary chicken farms that were kept on rooftops have been replaced by factory-produced chickens. As the catastrophe is global, Nājī imagines this society taking over the entire planet, destroying national borders and reshaping geographies, while a hybrid of Chinese, French, Arabic and English becomes the lingua franca.

Writing from the future, Bassām reflects on the environmental disaster. He criticizes the new generation of artists living in post-apocalyptic Egypt, their obsession with “green” (akhḍar), and their regret for not having tried to save the environment before the catastrophe. For him, climate change was inevitable:

If you ask me, nature was never not angry. Climate change isn't the exception, it's the rule – without it, the human race and all other species on this planet wouldn't have existed. And another thing: nature isn't just green. The desert, with its range of yellows and reds, is a fundamental part of it as well. This whole idea of “fighting yellowism” under the pretence of appeasing the great green goddess is therefore nothing but a savage transgression against the natural order of things.

But who'd listen? These nature fanatics can be real pricks.

Even now, a full twenty years later, we haven't managed to grasp the true scale of the disaster.Footnote43

واقع الأمر أن الطبيعة ليست حالة ساكنة وتغيرها وتبدل ظروفها المناخية والجغرافية هو الأمر الطبيعي، ولولا التبدلات المناخية تلك ما كان الجنس البشري وغيره من الأجناس ليظهر على سطح هذه الكوكب. واقع الأمر أن الطبيعة أيضًا ليست خضراء. فالصحراء برمالها الصفراء وأحيانا الحمراء في بعض المناطق الجغرافية هي جزء أساسي من الطبيعة، ومحاربة اللون الأصفر لصالح اللون الأخضر تحت زعم خدمة إله الطبيعة الأخضر هو تضليل بيّن واعتداء وحشي على الطبيعة.

لكن نقول لمين؟ أنصار البيئة دايما معرّصين

وحتى الآن وبعد عشرين عامًا لم نستوعب حجم الفاجعة.Footnote44

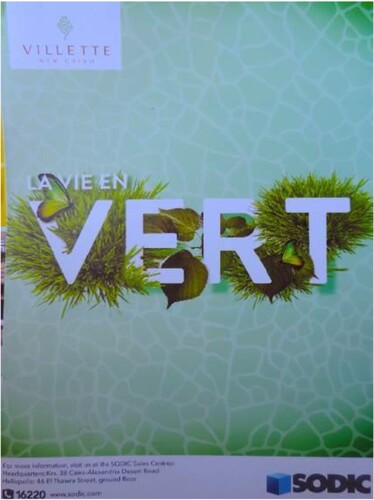

Figure 1. Advertisement by a real estate company in Egypt, retrieved from Abaza, “Cairo: Personal Reflections on Enduring Daily Life,” 2016, 234.

Anthropogenic “greenings” of the Egyptian environment represent what Rob Nixon has seminally theorised as “slow violence,” describing violence that occurs "gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all." According to Nixon, slow violence can be found embedded within the "slowly unfolding environmental catastrophes" of long-term pollution, climate change or nuclear fallout. But it can also describe kinds of harm that affect individuals and communities at a pace too slow to assign blame, and whose perpetrators are often beyond the reach of prosecution. Nixon, however, assigns an important function to “environmental activist writers” from post-colonial societies who shed light on this harm. In Istikhdām, Bassām is this voice. He does not have the capacity to halt urban, anthropogenic transformations, but, unlike other characters, is able to interpret future realities within the context of historical environmental violence, and thus openly criticize the Society’s plan with his bitter humor.

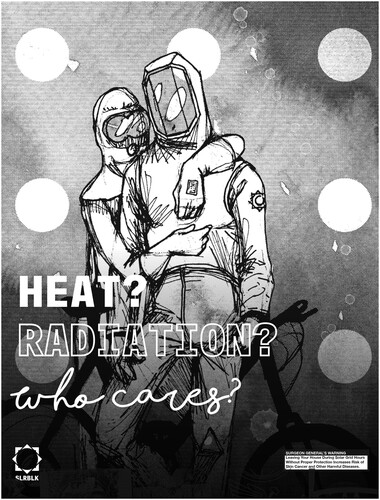

Capitalistic exploitation of nature, global climate change, and political authoritarianism are also explored in Ganzeer’s The Solar Grid. Gaining international fame following the 2011 Egyptian Revolution, thanks to his artwork that criticized the SCAF, the Military Council which took power in 2011, Ganzeer left Egypt in 2014 after receiving explicit accusations of being affiliated to the Muslim Brotherhood. From there he published The Solar Grid in instalments between 2016 and 2023. Written mostly in English, with occasional Arabic, it tells the story of the world after being destroyed by a climate crisis that takes the form of a flood. The global population who are affluent enough leave Earth and relocate to the Moon and Mars, exposing inequalities in race and gender. Like the foreign corporation imagined by Nājī, Ganzeer imagines an Arab billionaire scientist, Sharif Algebri, establishing a New World Order Alliance that capitalizes on the catastrophe through technology. He implements the Solar Grid project (al-qubba al-shamsiyyā), a network of satellites that surrounds the planet, absorbing energy from the sun and applying heat to wet places to dry them out and reduce the level of water that submerges the land. However, Algebri’s intent is far from a benign rescue of the “wretched of the Earth.”Footnote49 His plan is to invest this solar energy in solar-powered factories that produce goods for Mars, turning the Earth into a factory and junkyard for the inhabitants of other planets. On future Earth, there is no night-time: as the sun sets, the solar grid automatically turns on, and turns off as soon as the sun rises again, causing serious health damage for the population. Algebri’s capitalistic endeavor is visually rendered in the novel through advertisements of his commercial projects, promoting “solar protective suits” through the catchphrase “Heat? Radiation? Who Cares?,” which paraphrases sceptical and dismissive claims around the climate crisis for profit-making ().Footnote50 Yet several characters also resist: a whistle-blower who tries to stop Algebri’s project in 474 AF (After the Flood) by secretly unveiling to international media Algebri’s project to steal water from the Earth; two children who try to sabotage the Solar Grid project in 949 AF; and, before that, a young art student from Cairo whose artistic posters exhort the population to “resist the Solar Grid” (qawwamū al-qubbah al-shamsiyyah), including symbols derived from Ancient Egyptian and Islamic civilizations.Footnote51 By inserting a fictional avatar of himself in the narrative, Ganzeer connects his own attempt to “#resistdystopia” (a hashtag that recurs in the novel) with future attempts. In this sense, his characters play the same role as Bassām, mirroring Nājī in his adamant criticism of the New Capital and sharing autobiographical details with him (both author a blog with the same pseudonym, Bīsū, and have lived in 6th of October city). In addition, just as Istikhdām al-Ḥayāh oscillates between 2011 and the 2050s, The Solar Grid is arranged in different temporalities, constellated around the flood, and rendered with different graphic techniques. In 9 AF, when the solar grid has not yet been built, and the earth is still flooded, scenes are rendered with a lot of ink, evoking water and humidity. In 474 AF, the solar grid has been built, and the lines are much clearer, with a stark white and black line that renders the dry atmosphere. Other chapters take place thousands of years later, on Mars, where parts of the Earth’s population establish a direct democracy with the help of AI. These are the only sequences in the novel that are reproduced in color, mainly yellow and blue, to mimic a digital, mediated reality.Footnote52 Posters, graffiti, flyers, adverts, and text messages are also used to recreate the urban setting. As Dominic Davies argues in his analyses of the graphic novel, these “urban textual ephemerals” function both as a background for the story, but also contain important narrative clues, prompting us to read the novel as if walking through a modern metropolis as we assemble and interpret them.Footnote53

Ganzeer has stated that the climate crisis was a means through which to address political, racial, and economic concerns on a global level, while also driven by factors specific to his Egyptian background, and most notably the massive anthropogenic transformation wrought by the Aswan Dam.Footnote54 In this sense, the novel embodies Ursula K. Heise’s “eco-cosmopolitanism,” describing how ecological narratives convey “a narrative architecture that is able to accommodate a global system with local stories.”Footnote55 The Solar Grid’s cosmopolitan nature is evident in Ganzeer’s use of English, mixed with Arabic, coupled with Japanese manga techniques; a succession of visual clues often rendered through facial expressions rather than dialogues. The global extent of the crisis is imagined through Algebry’s capitalist and colonial project, which goes beyond the Earth to reach the Moon and Mars. However, Ganzeer’s sense of Egypt is also clear. When a TV presenter dares to problematize Algebry’s projects, pointing to the health risks posed by the grid and the exploitation of water resources, Algebry starts to swear in Egyptian colloquial Arabic. “Losing it on television is bad enough. Losing it on television in Arabic, now, that’s … ” admits his secretary, hinting at the Islamophobic discourse attached to Arabic in the West.Footnote56 Finally, a scene portraying the arrest of the young artist takes place outside the Cairo High Court, familiar to Egyptian readers, and portrayed in realistic detail, despite being set in the future, and submerged by rain and water.

The same eco-cosmopolitanism animates Istikhdām al-Ḥayāh, where narration zooms in and out of Cairo, showing the interconnectedness of places, and imagining the city as a foreshadowing of wider global catastrophe. The novel’s first two pages map precise locations in Cairo that have been transformed (Zamalek, Maadi, Giza), later panning out to the globe, then returning to the city of 6th October. The intersection between the local and global can also be seen in the characters that inhabit the novel; from specific references to popular singers and actresses Samīra Saʿīd and Umm Kulthūm, to the Egypt-born American post-modern philosopher Ihāb Ḥassan, to fictional super-heroes like Babrīka.

Iraq: insights into a post-Oil future

While Istikhdām al-Ḥayāh and the Solar Grid deal with floods, and the anthropogenic transformation of desert and Nile, the Iraqi stories focus on oil resources in Baghdad and Basra. Iraq +100 (2016), in which both appear, is a collection of short stories commissioned by the UK-based publishing house Comma Press and edited by Ḥasan Blāsim. The English version of the collection came out before the Arabic, entitled al-ʿIrāq + 100: qiṣaṣ fanṭāziyah wa-khayyāl ʿilmī baʿd miʾat ʿāmm min al-iḥtilāl al-amrīkī (2017, Iraq +100: Fantastic Stories and SF 100 Years After American Occupation). In his introduction, Blāsim categorizes the book as SF, suggesting that this type of literature never flourished in Arabic because of a lack of more general scientific progress in the region, alongside political and religious censorship.Footnote57 He explains that imagining the future means writing about “a life that is almost unknown, without authors relying directly on their own experience or their personal reading of their past or the present.”Footnote58 Yet, both Blāsim and Jubaylī envision the future based equally on personal experience and history. The very fact that the volume takes 2003 as its starting-point emphasizes its rootedness in contemporary realities.

Just like the Egyptian novels, Blāsim’s “Ḥadāʾīq Bābil” oscillates between two timelines, narrated by separate voices. One belongs to a translator living before the climate disaster, presumably in post-2014, as Iraq is ruled by a terrorist Islamic state. The other is a graphic designer living in post-2103, who has been hired by the government to produce a videogame (luʿbah qiṣaṣiyya) about life before the apocalypse. The two voices remain unnamed and are almost indiscernible (though one is rendered in italics), merging past, present and future. Only at the novel’s end do they become more clearly distinguished from one another.

Through the graphic designer’s voice, we learn that Baghdad has been destroyed by climate change and the exhaustion of oil resources. During the initial sandstorms, several international governments try to save the city, primarily to secure its oil wells, until Chinese-designed and implemented “dome cities” (qubāb ʿamlāqa) transform Baghdad into a heaven for digital creators. Life in the domes seems almost adequate, according to the narrator, who appreciates the country’s ruler, the Queen of Babylon (malikat Bābil), because she grants her citizens creative freedom. In addition, Chinese colonizers offer all kinds of social services, from Chinese citizenship to health, education, and sex hotels, while technology provides solutions to climatic challenges. Yet, social inequality remains. An Iranian-made train transports water from Northern and Central Europe to Mesopotamia, but, while some have enough “e-quotas” to fill their fountains and swimming pools, citizens in poor areas receive hardly a drop. Through Sara, a friend of the game developer, we learn that the One World Committee (lajnat ʿālam wāḥid) is trying to establish a space dictatorship on Mars. Old Baghdad is a desert area, where masks protect against burning temperatures and sandstorms.

Further cracks emerge in the idyll. The narrator’s job is to design a videogame based on a story written by a “classic” writer (kātib klāssīkī ) from pre-apocalypse Iraq, who shares many autobiographical elements with Blāsim. However, despite being granted complete freedom to design the games as he chooses, he is overcome with a boredom that echoes that of Bassām in Istikhdām al-Ḥayāh. To find inspiration, he consumes a hallucinogenic insect from Brazil, allowing him to merge the video-game experience with the classic writer’s literary world, the translator living in 2014 (the second narrator), and his cat, blurring the story’s temporalities and locations, as well as the limits between “virtual” and “reality,” human and non-human characters, and, ultimately, questioning the reliability of the narrating voices. While Blāsim intends the story as SF, there are many hints at contemporary reality: American invasion, linked to resource exploitation, continued by local elites; the ascent of Chinese authoritarian capitalism – “the Chimerican age” – in which China has joined and overextended America as a global force in the Global South.Footnote59

In 2014, we encounter the translator in his garden, inhabited by orange trees and sparrows and illuminated by sunlight. These warm colors and fresh scents constitute the background for a conversation between the narrator and his father about a terrifying reality beyond the garden walls. The father confesses to his son that he has long been involved in plotting a terrorist attack against the oil pipeline, protesting the government’s plans to implement new ones in the city’s historical ruins. On a more universal level, the dialogue between the translator and his father, linking the collapse of the natural environment to violence and the devastation of human relationships, could be interpreted in light of Johns-Putra’s concept of “parenthood as posterity,” meaning that the child is constructed both as an object of care and as the future inheritor of the planet.Footnote60 The father’s confession and his courageous efforts to remember the past attempt to inscribe the crisis in a long chain of obligations, and to link parental care to the possibility of a better future. The same care exists between the video gamer and his friend Sara. Through the hallucinatory trip facilitated by Sara, the video gamer finds out that the translator is his ancestor, thus establishing a historical line between the world after the climate crisis and the 2003 oil-driven conflicts in Iraq.

While the other texts discussed so far oscillate between future and recent past, Jubaylī’s “al-Mutakallim” is post-apocalyptic, depicting Basra immediately after the exhaustion of oil, uranium, mercury, solar power, and even bronze artefacts. This leads to a series of disasters, documented by the “council of advisors in the field of history” (ʿaṣabat al-khubarāʾ fī majāl al-tārīkh), including massacres, famine, epidemics, extreme poverty, and human trafficking. Here too, the story is told by two different voices and can be divided into two parts. The first part is told by a wealthy shaykh ruling Basra in 2103, the last of a long dynasty of religious leaders in the city since the previous century. The shaykh addresses the citizens of Basra in a monologue in which he dismisses the effects of the tragedy by comparing it to the much bigger – in his view – historical catastrophes that occurred in the West, such as the Black Death in Europe and the Holocaust, among others. The second part, is, however, told by a statue, who, unlike its bronze counterparts, is made of concrete, and thus cannot be dissolved to extract energy, but rather is shipped to a foreign museum. The Arabic title, “al-Mutakallim,” means “the Speaker,” alluding to both the story’s narrators, while the English translation, “The Worker,” refers only to the statue. As readers, we get to “hear” the shaykh’s voice first from the isolated room where he is sitting, remote from events; then in the second part, buzzing through the speakers, and it contrasts with the post-apocalyptic scenario depicted by the statue. Here too, like “Ḥadāʾīq Bābil,” the story plays with precise references to Iraqi historical and urban reality. The Worker’s statue is located in Basra’s main square, where it was erected in the 1970s to mark the International Day of Workers, and where it remains as a communist symbol.Footnote61 The presence of statues in Iraq also refers to Ṣaddām Ḥussain’s obsession with creating statues of himself, forcibly removed by the American troops upon their arrival in Iraq and later attacked by local populations.Footnote62

Despite being located in Basra and Baghdad, both stories from Iraq +100 link local crisis to global imagination. The world comes to Iraq through Chinese colonization and technologies, and the commodification of global goods (from drugs to water trains), but also Iraq’s local catastrophe is compared to similar tragedies taking place in other parts of the world. Jubaylī’s Basra and Blāsim’s Baghdad reflect their apprehensions of the cities’ slow death from pollution and exploitation. Jubaylī has explicitly linked the 2019 protests in Basra to the Iraqi youth’s preoccupation with the city’s environmental degradation:

Some major oil companies have invested in Basra’s oil fields, yet the level of bribery involved is unmatched around the globe. Despite all the local development projects promised in the original contracts – and all the claims by chief negotiator and former oil minister Hussain al-Shahristani – we don’t even see efforts to combat the fumes and smoke that pour out of the oil wells. Today, Basra suffers a slow death from the pollution and poison that flow from the industry that was supposed to be its saviour.Footnote63

The two authors use historical references to highlight this slow violence: the Queen of Mesopotamia orders the video-game writer to re-enact a story by the classic writer, as a means of celebrating the splendid future under the domes, contrasting it with the violent past. The shaykh asks the council of historians to retrieve documents of historical catastrophes to contrast them with, and thus minimize, the contemporary catastrophe. And yet, in both stories, the main characters also adopt history as an element of salvation from the dystopic future. In his hallucinating dream, the video gamer discovers his connection to the translator and classic author.Footnote65 In “al-Mutakallim,” the worker’s statue finds itself piled together with many other statues in the museum, among which one child, while visiting, recognizes the “dictator,” Ṣaddām Ḥussain. “Did they find a nuclear bomb (al-qunbulah al-nawawiyyah) in his mouth,” the child asks the guide. “You should ask your great-grandfather (jaddak at-thānī),”Footnote66 he is answered, hinting at the raging controversy over Iraq’s possession of weapons of mass destruction, which was used to justified the US invasion.Footnote67 Both narrators refer to their grandfather’s generations (the authors’ own generation) as complicit perpetrators of anthropogenic slow violence. By bringing history and the present together, they emphazise the brevity of the current fossil-fuel interregnum in human history, showing instead that it will throw a long shadow into the future, along with concomitant lethal effects on the populations of countries where oil has been most plentiful.

According to the literary scholars Moylan and Baccolini, if despair is the condition of the citizen of dystopia, knowledge and awareness are those of the protagonists of the “critical dystopia.” The recovery of memory and history is an important element for the survival of hope, as it leads to a more open and critical condition. If information about the past is strictly controlled and manipulated by those in command, history gives the dystopian citizen a powerful instrument of resistance.Footnote68 While petrol, a resource central to both stories, is subterranean, politically opaque, rife with secret concessions and backroom deals, the two stories contrast it with the realm of the grove and the non-human – trees, cats and drug insects in Blāsim, and statues in Jubaylī’s story – which act as “bioregional and historical stakeholders, as palpable markers of contested memory, as standard bearers of sustainable life and equally of cultural dignity.”Footnote69

Conclusion: critical hope in Arabic cli-fi

The works analyzed in this article speak about an age and a region that is facing a double calamity: the economic cliff edge of oil’s diminishing tides, particularly for lower social classes; and climate change, exacerbated by oil extraction and combustion and urban mega-projects. Despite being set in the future, and focusing on urban environments, they depict the climate crisis as a contemporary reality, manifested in water scarcity, floods, and heatwaves. Through the overlapping aesthetics of cli fi, SF and dystopian fiction, the texts place the climate crisis at different points in time and play with temporalities that oscillate between the distant and recent past, and the future. In The Solar Grid, the flood remains undated and yet tangible, hinting that it might occur any time, and will change the world forever. In Istikhdam al-Ḥayāh, the environmental nakba takes place in the 2050s yet the date is left undefined, as a means of forcing the reader to actively calculate the catastrophe’s temporal span. In the stories from al-ʿIrāq + 100, the narration takes place in 2103, one hundred years after the Invasion of Iraq, in a far-distant future.

The authors link their local scenarios, Cairo, Baghdad, and Basra, with the rest of the world, using environmental crisis to connect the local and global. The urban scenarios they depict take inspiration from current reality, whether in unsustainable living conditions, pollution, traffic, or heat waves, as well as urban mega-projects, in which Arab governments and foreign investors co-operate to potentially disastrous effect. The authors also share a common vision: humanity will once again survive climatic changes, as it has historically done. However, through characters such as Algebri in The Solar Grid, Bābrīkā in Istikhdam al-Ḥayāh, the Queen of Mesopotamia in “Ḥadāʾīq Bābil,” and the shaykh in “al-Mutakallim,” the authors warn us that dictators and corporate capitalists will inevitably profit from the apocalypse, providing technical solutions while stripping the population of freedom and dignity.

Possibility for hope is embodied by characters that question, silently observe, or actively resist: from Bassām in Istikhdam al-Ḥayāh, who casts light on the history of climate change in Egypt by delving into the archive, to the video-gamer who silently observes the ruins of BaghdadFootnote70 and connects the current climate crisis to years of war and violence linked to oil exploitation. The Statue of Basra, who collects dead bodies at night, and finally, the journalist, the artist and the boys who oppose the Solar Grid’s project also dramatize different degrees of resistance. While some actively resist the crisis, like the young artist in The Solar Grid, others are observers, or, at most, recorders, of crisis, suggesting the inability for individuals to alter global processes, and implying a more ambiguous role for literary authors. The multimedia and fragmented structure of these works (especially the juxtaposition of visuals and text in the graphic novels and their open endings), contribute to their critical nature. These four works show that climate fiction in Arabic remains in the realm of SF, and interlaces with the genre of critical dystopia, a type of fiction that projects pessimistic scenarios and yet maintains a horizon of hope, or “at least invite readings that do.”Footnote71 Nājī, Ganzeer, Blāsim and Jubaylī use dystopian fiction to raise awareness around the local and global dimensions of the climate crisis, anchoring their narratives in a sense of place, yet communicating their global concerns, born of lives between the Arab world, the US, and Europe. Given that some of these works, the two stories in Iraq +100 and The Solar Grid, have appeared first in English, and that their authors reside mostly abroad, these works have gained more international than local attention though undoubtedly they will inspire future generations of activists and writers from the region.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 A shorter version of this article has been published for MECAM Papers, available in English, French and Arabic. See “Environment and Climate Change in Contemporary Arabic Dystopian Fiction”. MECAM Papers (2) in English, 2022. http://doi.org/10.25673/92260; “Environnement et changement climatique dans la fiction dystopique arabe contemporaine”. MECAM Papers (2) in French, translated by Amel Guizani, http://doi.org/10.25673/92262; “Azmat al-manākh fī adab al-distūbyā al-ʿarabī al-muʿaṣīr”, MECAM Papers (2) in Arabic, translated by Amel Guizani and Tamer Fathy, http://doi.org/10.25673/92263. I would like to thank the editor Charis Olszok and the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on the initial version of this paper.

2 For an historical overview of the genre in Arabic, see Snir, “The Emergence of Science Fiction in Arabic Literature”; Barbaro, La fantascienza nella letteratura araba; Campbell, Arabic Science Fiction; Ayed, La littérature d'anticipation dystopique et l'expression de la crise.

3 Campbell, Arabic Science Fiction, 21.

4 Muller, Lost Futurities, 16. See also: Determann, Islam, Science Fiction and Extraterrestrial Life.

5 Paniconi, “Ḍarīḥ Abī by Ṭāriq Imām”; Pepe, “Aḥmad Nājī’s Istikhdām al-Ḥayāh”; Milich, “The Politics of Terror”; Said, “Dystopianizing the Revolution”. See also Murphy, “Science Fiction and the Arab Spring”; Chiti, “A Dark Comedy”; Alter, “Middle Eastern Writers Find Refuge in the Dystopian Novel”.

6 Milner, “Changing the Climate”. Milner and Burgmann, Science Fiction and Climate Change; Heise, Sense of Place and Sense of Planet.

7 Glass, “The Rise of Cli-Fi”.

8 Trexler and Johns-Putra, “Climate change in literature and literary criticism”, 186.

9 Johns-Putra, “Climate change in literature and literary studies”, 4.

10 Ṣubḥ, “Adab taghayyur al-manākh … iṣdārāt ṭalīʿiyya li-thīmah mustaqbaliyyah”.

11 Al-Rajīb, “Al-Adab al-bīʿī”.

12 Ghālī, “Klāymat fikshun: nawʿ adabī jadīd”.

13 Verner, “Adaptation to a Changing Climate in the Arab Countries”.

14 Lelieveld et al.,“Strongly increasing heat extremes in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) in the 21st century”.

15 Arafat, “Vegetable Prices Soar as Crop Yields Suffer from Cold Wave”.

16 Mahmoud, “Impact of Climate Change on the Agricultural Sector in Egypt”.

17 IOM, Migration, Environment and Climate Change in Iraq, 6.

18 Verdeil, “Arab Sustainable Urbanism: Worlding Strategies, Local Struggles”, 36.

19 Barbaro, “Science Fiction in Arabic Was Not Born All of a Sudden”.

20 Rooke, “The Planet of Stupidity”, 112.

21 Webster, “Ruins of the Future”, 381.

22 Goodbody and Johns-Putra, Cli-Fi: A Companion, 2

23 Szeman, “Introduction to Focus: Petrofictions”, 3.

24 ʿAqīl, “Adab al-mudun al-fāsida yajtāḥ al-riwaya al-ʿarabiyya”.

25 Verdeil, “Arab Sustainable Urbanism: Worlding Strategies, Local Struggles”, 36.

26 Deboulet and Mansour, “Introduction”, 13.

27 See: Hermes and Head (eds.), The City in Arabic Literature: Classical and Modern Perspectives; Mehrez (ed.), The Literary Life of Cairo: One Hundred Years in the Heart of the City.

28 Bennett and Teague, The Nature of Cities, 9.

29 Some examples include Sinno, “The Greening of Modern Arabic Literature”; Ramsay, “Breaking the Silence of Nature”; Ghazoul, “Greening in Contemporary Arabic Literature”.

30 James, The Storyworld Accord, 23.

31 Johns-Putra, Climate Change and the Contemporary Novel, 140.

32 Nixon, Slow Violence and The Environmentalism of the Poor.

33 Heise, Sense of Place and Sense of Planet.

34 Moylan and Baccolini, Dark Horizons, 7.

35 Ibid, 7.

36 “Ayy mustaqbal? Naḥnu fīhi alān, wa-kam ashʿur bi-l-sāʾm minhu”. Nājī, Istikhdām al-Ḥayāh, 35, my translation.

37 Lawson, “Duality, Opposition and Typology in the Qur’an,” 23-49.

38 Naji and al-Zorqany, Using Life, 2.

39 Naji and al-Zorqany, Using Life, 38. The original text reads: “rāʾiḥat al-nifāyāt wa-l-rawth al-qādima min maqālib al-nifaya wa mazāriʿ al-khanāzīr tuṣībunī bi-l-ghathayān”, Nājī, Istikhdām al-Ḥayah, 50.

40 Naji and al-Zorqany, Using Life, 179. “amma dākhil al-madīna fa-qad kāna al-izdiḥām wa-l-intiẓār humā al-īqāʿ al-tabīʿī li-l-ḥayāh”, Nājī, Istikhdām al-Ḥayah, 204.

41 Naji and al-Zorqany, Using Life, 38-39. “Marḥaban bi-kum fī jaḥīm al-qāhira, ḥaythu al-ḥayāh kulluhā intiẓār, wa-rāʾiḥat al-zibāla wa rawth al-ḥayawanāt bi-anwāʿihā dāʾiman fī kull makān”, Nājī, Istikhdām al-Ḥayah, 50.

42 For example, Muḥammad Rabīʿ’s ʿUtarid features a character who functions as a garbage collector; Naʿil Al-Tūkhī’s novel Nisāʾ al-Karantīnā opens and closes with the description of a dog rummaging through garbage.

43 Naji and al-Zorqany, Using Life, 21

44 Nājī, Istikhdām al-Ḥayāh, 34.

45 Naji and al-Zorqany, Using Life, 22. “Huwa al-māḍī yughayyir ashkālahu”, Nājī, Istikhdām al-Ḥayah, 35.

46 Davis, “Imperialism, Orientalism, and the Environment in the Middle East History”, 7. See also Sims, Egypt’s Desert Dreams, and Mikhail, Nature and Empire in Ottoman Egypt.

47 Sims, “Greater Cairo and Greenhouse Gas Emissions”, 12.

48 An advertisement from another Egyptian real estate, Agyad Multi, recites: “Enjoy the luxury of a full-service residential community away from the noise and bustle of the capital. Located in the heart of vast green spaces, fresh air, and sunshine, the Agadir Garden City Compound means calm and peacefulness, in perfect harmony with nature combined with architectural beauty, uniting beauty and creativity with the highest standards of luxury. Special service and security, as well as maintenance and cleaning services, are provided for every unit separately, ensuring enjoyment, comfort, and tranquillity” (my emphasis). Quoted in Abaza, “Cairo: Personal Reflections”, 234. See also: Abotera and Ashoub, “Billboard Spaces in Egypt” and Guth, “Gated Communities / Compounds”.

49 Ganzeer, The Solar Grid, v. 1, 4-5.

50 Ganzeer, The Solar Grid, v. 1, 39.

51 Ganzeer, The Solar Grid, v. 4, 6. On his Instagram account, Ganzeer clarifies that the drawing of the young female artist is based on a mural painted by the Egyptian artist Ammar abo Bakr, which is in turn based on a photograph of Hisham Rizk, a young artist from Cairo who died in unclear circumstances in 2014 after having disappeared for a week. Interestingly, the reported cause of death was: “Drowning in the Nile” (21 February 2023). As a review of the novel in the sci-fi magazine Strange Horizon acknowledges, “The Solar Grid is dense with influence and reference” (Fahmy, The Solar Grid by Ganzeer).

52 Ganzeer, “The Global Comics”.

53 Davies, “Contingent Futures and the Time of Crisis”, 166.

54 Batty, “From Revolutionary Art to Dystopian Comics”.

55 Heise, Sense of Place and Sense of Planet, 61.

56 Ganzeer, The Solar Grid, v. 2, 41

57 Blāsim, “Muqaddima” to al-ʿIrāq +100, 12.

58 Blāsim, “Muqaddima” to al-ʿIrāq +100, 10.

59 The same political anxiety about the increasing presence of China in the global political scene also recurs in Ganzeer’s The Solar Grid, where the graphic narration is interrupted by an article published in the future Global Guardian published in 474 AF, with the headline: “America: China’s Apology is Not enough”, 59. In Nājī’s Istikhdām al-Ḥāyāh, likewise, Chinese is a language widely spoken in the New Capital.

60 Johns-Putra, Climate Change and the Contemporary Novel, 4.

61 Jubayli, “The Worker”, 80.

62 Tunzelmann, “The toppling of Saddam’s statue: how the US military made a myth”.

63 Jubayli, “Pollution and corruption are choking the life out of Basra”.

64 Ross, “The political economy of the resource curse”.

65 Blāsim, “Ḥadāʾīq Bābil”, 58.

66 Jubaylī, “al-Mutakallim”, 217.

67 Leffler, Confronting Saddam Hussein, 15.

68 Moylan and Baccolini, Dark Horizons, 115.

69 Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, 79.

70 Webster, “Ruins of the Future”, 390.

71 Baccolini and Moylan, Dark Horizons, 7.

Bibliography

- Abaza, Mona. “Cairo: Personal reflections on Enduring Daily Life.” Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies 16 (2017): 234–52. doi:10.5617/jais.4750.

- Abotera, Mohamad, and Ashoub Safa. “Billboard Space in Egypt: Reproducing Nature and Dominating Spaces of Representation.” The Urban Transcripts Journal 3, no. 1 (2017). Accessed February 20, 2023. https://journal.urbantranscripts.org/article/billboard-space-egypt-reproducing-nature-dominating-spaces-representation-mohamad-abotera-safa-ashoub/.

- Al-Rajīb, Walīd. “Al-Adab al-Biʿī.” [The Literature of the Environment.] Alrai-media, November 29, 2019. Accessed February 10, 2022. https://www.alraimedia.com/article/869859/%D9%85%D9%82%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%AA/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%AF%D8%A8-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A8%D9%8A%D8%A6%D9%8A.

- Al-Tūkhī, Naʿil. Nisāʾ al-Karāntīnā. Cairo: Dār al-Mīrīt, 2013. (Women of Karantina, Transl. by Robin Moger. Cairo: AUC Press, 2015).

- Alter, Alexandra. “Middle Eastern Writers Find Refuge in the Dystopian Novel.” The New York Times, May 29, 2016. Accessed June 30, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/30/books/middle-eastern-writers-find-refuge-in-the-dystopian-novel.html.

- ʿAqīl, Ḥanān. “Adab al-mudun al-fāsida yajtāḥ al-riwāyah al-ʿarabiyyah,” al-ʿAraby, February 2, 2017. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://alarab.co.uk/أدب-المدن-الفاسدة-يجتاح-الرواية-العربية.

- Arafat, Nada. “Vegetable Prices Soar as Crop Yields Suffer from Cold Wave,” Mada Masr, 1 February, 2022. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://www.madamasr.com/en/2022/02/01/feature/economy/vegetable-prices-soar-as-crop-yields-suffer-from-cold-wave/.

- Ayed, Kawthar. La littérature d'anticipation dystopique et l'expression de la crise. Aix-en-Provence: Éditions Universitaires Européennes, 2019.

- Barbaro, Ada. “Science Fiction in Arabic: ‘It Was Not Born All of a Sudden’” interview with ArabLit Quarterly, 2013. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://arablit.org/2013/09/30/science-fiction-in-arabic-it-was-not-born-all-of-a-sudden/.

- Barbaro, Ada. La fantascienza nella letteratura araba. Rome: Carocci Editori, 2013.

- Batty, David. “From Revolutionary Art to Dystopian Comics: Ganzeer on Snowden, Censorship and Global Warming.” The Guardian, July 20, 2016. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/jul/20/ganzeers-graphic-novel-future-dystopia-recent-history-egypt-the-solar-girl.

- Bennett, Michael, and David W. Teague. The Nature of Cities: Ecocriticism and Urban Environments. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1999.

- Blasim, Hassan. “The Gardens of Babylon.” In Iraq + 100: Short Stories from a Century After the Invasion, Translated by Jonathan Wright, 11–34. Manchester: Comma Press, 2016.

- Blāsim, Ḥasan. “Ḥadāʾīq Bābil.” In al-ʿIrāq +100: qiṣaṣ fanṭāziyah wa-khayyāl ʿilmī baʿd miʾat ʿāmm min al-iḥtilāl al-amrīkī, edited by T. Hasan Blāsim, 35–60. Bruxelles: Dār Alkā, 2017.

- Blāsim, Ḥasan. “Muqaddima.” In al-῾Irāq +100: qiṣaṣ fanṭāziyah wa-khayyāl ʿilmī baʿd miʾat ʿāmm min al-iḥtilāl al-amrīkī, edited by T. Hasan Blāsim, 9–14. Bruxelles: Dār Alkā, 2017.

- Campbell, Ian. Arabic Science Fiction. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

- Chiti, Elena. “A Dark Comedy: Perceptions of the Egyptian Present between Reality and Fiction.” Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies 16 (2017): 273–289. doi:10.5617/jais.4752.

- Davies, Dominic. “Contingent Futures and the Time of Crisis: Ganzeer’s Transmedial Narrative Art.” Literary Geographies 8, no. 2 (2022): 154–174.

- Davis, Diana K. “Imperialism, Orientalism, and the Environment in the Middle East: History, Policy, Power, and Practice.” In Environmental Imaginaries of the Middle East and North Africa, edited by Diana K. Davis, and Edmund Burke, 1–22. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2011.

- Deboulet, Agnès, and Waleed Mansour. “Introduction. Cities and Urban Regions: Central Actors in the Climate Crisis.” In Middle Eastern Cities in a Time of Climate Crisis, edited by Agnès Deboulet, and Waleed Mansour, 3–19. Le Caire: CEDEJ - Égypte/Soudan, 2022. <http://books.openedition.org/cedej/8544>.

- Determann, Jörg Matthias. Islam, Science Fiction and Extraterrestrial Life: The Culture of Astrobiology in the Muslim World. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020.

- Fahmy, Hazem. “The Solar Grid by Ganzeer,” Strange Horizons, Fund Drive 2021, http://strangehorizons.com/non-fiction/the-solar-grid-by-ganzeer/, (accessed June 20, 2023).

- Ganzeer. From Tahrir to "The Solar Grid," Global Comics Series, The Ohio State University Libraries. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sdAHhLTH5gw.

- Ganzeer. The Solar Grid, vol. 1-7. Brooklyn: Radix Media, 2016-2023.

- Ghālī, Dana. “Klāymat Fikshun: Nawʿ Adabī Jadīd.” [Climate Fiction: A New Literary Genre.] al-Faisal, December 26, 2016. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://www.alfaisalmag.com/?p=4022.

- Ghazoul, Ferial. “Greening in Contemporary Arabic Literature: The Transformation of Mythic Motifs in Postcolonial Discourse.” In The Future of Postcolonial Studies, edited by Chantal Zabus, 117–129. New York: Routledge, 2015.

- Glass, Rodge. “Global Warming: The Rise of Cli-fi.” The Guardian, May 31, 2013. Accessed February 2, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/may/31/global-warning-rise-cli-fi.

- Goodbody, Axel, and Adeline Johns-Putra. Cli-Fi: A Companion. Oxford: Peter Lang Publishing Group, 2018.

- Guth, Stephan. “Gated Communities / Compounds: An Array of Egyptian and Tunisian Lifeworlds in 2016.” Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies 21, no. 3 (2021). doi:10.5617/jais.9505.

- Heise, Ursula K. Sense of Place and Sense of Planet: The Environmental Imagination of the Global. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Hermes, Nizar F. and Head, Gretchen (eds.), The City in Arabic Literature: Classical and Modern Perspectives. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

- IOM. Migration, Environment and Climate Change in Iraq, 2022. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://environmentalmigration.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1411/files/documents/Migration%2C%20Environment%20and%20Climate%20Change%20in%20Iraq.pdf.

- James, Erin. The Storyworld Accord: Econarratology and Postcolonial Narratives. Frontiers of Narrative. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015.

- Johns-Putra, Adeline. “Climate Change in Literature and Literary Studies: From cli-fi, Climate Change Theater and Ecopoetry to Ecocriticism and Climate Change Criticism.” WIRES Climate Change 7, no. 2 (2016): 266–282. doi:10.1002/wcc.385.

- Johns-Putra, Adeline. Climate Change and the Contemporary Novel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Jubaili, Diaa. “Pollution and Corruption are Choking the Life Out of Basra,” The Guardian, September 13. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/sep/13/pollution-corruption-choking-life-out-of-basra.

- Jubaili, Diaa. “The Worker.” In Transl. Andrew Leber. In Iraq + 100: Short Stories from a Century After the Invasion, edited by Hassan Blasim, 61–80. Manchester: Comma Press, 2016.

- Jubaylī, Diyāʾ. “al-Mutakallim.” In al-ʿIrāq +100: qiṣaṣ fanṭāziyah wa-khayyāl ʿilmī baʿd miʾat ʿāmm min al-iḥtilāl al-amrīkī, edited by T. Hasan Blāsim, 195–220. Bruxelles: Dār Alkā, 2017.

- Lawson, Todd. “Duality, Opposition and Typology in the Qur'an: The Apocalyptic Substrate.” Journal of Qur'anic Studies 10, no. 2 (2008): 23–49.

- Leffler, Melvyn. Confronting Saddam Hussein: George W. Bush and the Invasion of Iraq. Oxford University Press, 2023.

- Lelieveld, J., Y. Proestos, P. Hadjinicolaou, et al. “Strongly Increasing Heat Extremes in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) in the 21st Century.” Climatic Change 137 (2016): 245–260. doi:10.1007/s10584-016-1665-6.

- Mahmoud, Sayed. “The Impact of Climate Change on Agriculture and Adaptation Mechanisms: The Case of Egypt.” Review of Applied Socio-Economic Research 23, no. 1 (2022): 119–33. doi:10.54609/reader.v23i1.133.

- Mehrez, Samia, ed. The Literary Life of Cairo: One Hundred Years in the Heart of the City. American University in Cairo Press, 2011.

- Mikhail, Alan. Nature and Empire in Ottoman Egypt. Cambridge: Cambridge University press, 2011.

- Milich, Stephan. “The Politics of Terror and Traumatization: State Violence and Dehumanization in Basma ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz’s al-Ṭābūr.” In Arabic Literature in the Posthuman Age, edited by Stephan Guth, and Teresa Pepe, 145–165. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz and Verlag, 2019.

- Milner, Andrew. “Changing the Climate: The Politics of Dystopia.” Continuum 23, no. 6 (2009): 827–838. doi:10.1080/10304310903294754.

- Milner, Andrew, and James R. Burgmann. Science Fiction and Climate Change: A Sociological Approach. Liverpool University Press, 2023.

- Moylan, Thomas, and Raffaella Baccolini. Dark Horizons: Science Fiction and the Dystopian Imagination. London and New York: Routledge, 2003.

- Muller, Nathalie. Lost Futurities: Science Fiction in Contemporary Art from the Middle East. Doctoral Thesis. Birmingham City University, 2022.

- Murphy, Sinéad. “Science Fiction and the Arab Spring: The Critical Dystopia in Contemporary Egyptian Fiction.” Strange Horizons 30, 2017. Accessed June 20, 2023. http://strangehorizons.com/non-fiction/science-fiction-and-the-arab-spring-the-critical-dystopia-in-contemporary-egyptian-fiction/.

- Nājī, Aḥmad. Istikhdām al-Ḥayāh. Cairo: Dar al-Tanwīr, 2014.

- Naji, Ahmad, and Ayman Al-Zorqany. Using Life. Translated by Ben Koerber. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2017.

- Naṣrallāh, Ibrāhīm. Ḥarb al-Kalb al-Thāniya. Beirut: Dār alʿarabiyyah li-l-ʿulūm wa an-nashirūn, 2017.

- Nixon, Rob. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011.

- Paniconi, Maria-Elena. “Ḍarīḥ Abī by Ṭāriq Imām: Dystopia and Fantasy-Folklore.” In Arabic Literature in the Posthuman Age, edited by Stephan Guth, and Teresa Pepe, 165–178. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz and Verlag, 2019.

- Pepe, Teresa. “Ahmed Naji’s Istikhdām al-ḥayāh (Using Life, 2015) as Critical Dystopia.” In Arabic Literature in the Posthuman Age, edited by Stephan Guth, and Teresa Pepe, 179–192. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz and Verlag, 2019.

- Rabiʿ, Muḥammad. ʿUtarid. Cairo: Dar al-Tanwir, 2015. (Otared, transl. by Robin Moger, Hoopoe, 2016).

- Ramsay, Gail. “Breaking the Silence of Nature in an Arabic Novel: Nazif al-Hajar by Ibrahim al-Kawni.” In From Tur Abdin to Hadramawt: Semitic Studies: Festschrift in Honour of Bo Isaksson on the occation of his retirement, Tal Davidovich, Ablahad Lahdo, edited by Torkel Lindquist, 149–172. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2015.

- Rooke, Tetz. “The Planet of Stupidity. Environmental Themes in Arabic Speculative Fiction.” In New Geographies: Texts and Contexts in Modern Arabic Literature, edited by Roger Allen, Parilla Fernandéz, and Tetz Rooke, 99–114. Madrid: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, 2018.

- Ross, Michael L. “The Political Economy of the Resource Curse.” World Politics 51, no. 2 (1999): 297–322.

- Said, Walaa. “Dystopianizing the ‘Revolution’: Mohammed Rabie’s Otared (2014).” In Arabic Literature in the Posthuman Age, edited by Stephan Guth, and Teresa Pepe, 193–210. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz and Verlag, 2019.

- Sansūr, Lārīsā [Sansour, Larissa] Space Exodus, 2009.

- Sansūr, Lārīsā [Sansour, Larissa]. Nation Estate, 2012.

- Sansūr, Lārisā, and Lind Søren. In the Future They Ate from the Finest Porcelain, 2015.

- Sims, David. Egypt’s Desert Dreams. Cairo: AUC Press, 2018.

- Sims, David. “Greater Cairo and Greenhouse Gas Emissions.” In Middle Eastern Cities in a Time of Climate Crisis, edited by Agnès Deboulet, and Waleed Mansour, 23–34. Le Caire: CEDEJ - Égypte/Soudan, 2022. http://books.openedition.org/cedej/8554.

- Sinno, Nadine A. “The Greening of Modern Arabic Literature: An Ecological Interpretation of Two Contemporary Arabic Novels.” Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 20, no. 1 (2013): 125–143. doi:10.1093/isle/ist013.

- Snir, Reuven. “The Emergence of Science Fiction in Arabic Literature.” Der Islam 77, no. 2 (2000): 263–85.

- Ṣubḥ, Fātin. “Adab Taghayyur al-Manākh … Iṣdārāt Ṭaliʿiyyah li-Thīmah Mustaqbaliyyah.” [Climate Change Fiction … Avant-garde Publications on a Futuristic Theme.] al-Bayān, July 21, 2018. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://www.albayan.ae/five-senses/mirrors/2018-07-21-1.3319503.

- Szeman, Imre. “Introduction to Focus: Petrofictions.” American Book Review 33 (2012): 3. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/480500.

- Tawfiq, Ahmed Khaled. Utopia. Translated by Chip Rossetti. Doha: Bloomsbury Qatar Foundation, 2012.

- Tawfīq, Aḥmad Khālid. Yūtūbiyā. Cairo: Dār Mirit, 2008.

- Trexler, Adam. Anthropocene Fictions: The Novel in a Time of Climate Change. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2015.

- Trexler, Adam, and Adeline Johns-Putra. “Climate Change in Literature and Literary Criticism.” WIREs Climate Change 2, no. 2 (2011): 185–200. doi:10.1002/wcc.105.

- Tunzelmann, Alex von. “The Toppling of Saddam’s Statue: How the US Military Made a Myth.” The Guardian, 2021. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jul/08/toppling-saddam-hussein-statue-iraq-us-victory-myth.

- Verdeil, Eric. “Arab Sustainable Urbanism: Worlding Strategies, Local Struggles.” Middle East - Topics & Arguments 12, no. 1 (2019): 35–42. doi:10.17192/meta.2019.12.7935.

- Verner, Dorte. “Adaptation to a Changing Climate in the Arab Countries: A Case for Adaptation Governance and Leadership in Building Climate Resilience.” In MENA Development Report. Washington: World Bank, 2012.

- Webster, Annie. “Ruins of the Future: On the Possibility of Life in the Aṭlāl.” Comparative Critical Studies 19, no. 3 (2022): 381–398.