ABSTRACT

Educational activities using microblogging co-located with face-to-face communication might promote productive classroom interactions. However, much depends on how teachers design those activities. This article explores how the educational design of an activity that uses microblogging engages lower secondary school students in classroom interactions that are productive for learning. It presents a study of one teacher’s educational design in which students (aged 12–13) in a Norwegian classroom use microblogging to explore distinctions between facts and opinions. Moreover, the authors consider how the students pick up on the educational design. The findings show that an educational design involving microblogging can provide new possibilities to facilitate peer interactions by systematically enabling students to access more of their peers’ ideas, produce and discuss collective ideas and participate in exploratory talk. In particular, the use of hashtags proves suitable for facilitating peer interactions with the aim to develop students’ critical thinking.

Introduction

Recent studies indicate that microblogging has the potential to promote learning. Microblogging used in the classroom enables learners and instructors to instantly exchange ideas with each other (Gao et al., Citation2012; Ludvigsen et al., Citation2019; Preston et al., Citation2015). However, most of these studies report on higher education. Additionally, only a few studies assess the co-located use of microblogging and face-to-face interactions (Tang & Hew, Citation2017). In this article, we present and discuss the co-located use of microblogging in a classroom activity in which students from a Norwegian lower secondary class explore the distinction between facts and opinions. The activity involves a microblogging tool designed to support interactions through both oral and written communication.

As with other educational technologies, teachers must think about how to embed microblogging in a pedagogical approach for it to be productive for learning (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, Citation2018). Dialogic pedagogy is beneficial for classroom interaction and learning (Howe et al., Citation2019), and studies suggest that microblogging might provide valuable support to this pedagogical approach (Major et al., Citation2018; Rasmussen & Hagen, Citation2015). We understand dialogic pedagogy as an approach that promotes productive interactions. Broadly conceived, productive interactions can refer to interactions through which students and teachers construct knowledge and understanding, and try new ways of understanding by sharing ideas, challenging and listening to each other, building on each other’s ideas, elaborating, providing reasons and thinking together while aiming for specific educational goals (Mercer & Littleton, Citation2007). However, designing activities that promote productive interactions can be challenging. Classrooms are dynamic environments that increasingly depend on technology, and classroom activities need to be prepared for the unexpected; thus, both planning and improvisation are important parts of teachers’ work (Lund & Hauge, Citation2011).

Our focus in this article is the educational design of an activity using a microblogging tool called Talkwall. We consider the educational design to include the teacher’s planned activities and learning objectives, which are influenced by the wider context of the school and the plans and requirements of local and national curricula. Furthermore, the educational design includes the teacher’s enacted design, which takes place during the process of realising and developing learning intentions (deSousa & Rasmussen, Citation2019; Hauge et al., Citation2007).

We followed one teacher and her class of 23 lower secondary students at a school located in a large Norwegian city. The teacher and her students participated in a larger research project called Digitalised Dialogues Across the Curriculum (DiDiAC), which focuses on developing new classroom tools and practices, particularly collaboration and critical thinking skills (evaluating and integrating information, forming and justifying ideas, and communicating in and across knowledge domains). The lesson we studied for the purpose of this article addressed the central aims in the national Norwegian language curriculum and the Basic Skills Framework (Utdanningsdirektoratet, Citation2018). Notably, the focus of the lesson was to distinguish between facts and opinions and to listen to and build on each other’s ideas. These skills, especially student oral competencies, are closely connected to the development of critical thinking, which is now one of the overarching goals in the Norwegian core curriculum (Utdanningsdirektoratet, Citation2020), as recognised in several policy documents (e.g., Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Citation2018). Despite the need to develop critical thinking skills in education, few scholars have suggested specific ways for teachers to support this development in Norwegian students, especially younger students (Ferguson & Krange, Citation2020). Our aim is to address this challenge by investigating a lower secondary teacher’s lesson design and show how the students picked up on this.

Research questions

What characterises the teacher’s educational design of an activity that uses a microblogging tool?

How do the students pick up on the teacher’s educational design?

The educational use of microblogging in classrooms

Microblogging is the process of posting short messages in a shared digital environment for every participant to see. One well-known example is Twitter. When used as a collaborative virtual learning environment, microblogging has the potential to promote learning for two reasons: first, resources can be shared instantly among learners, and second, instructors can exchange ideas with students in a timely manner (Gao et al., Citation2012). This section’s literature review focuses on (1) the co-located use of microblogging in a classroom context and (2) how to use microblogging to promote oral dialogue. However, studies within higher education dominate the scholarly literature; thus, we include findings that may translate into a primary school context.

In one study, students in a Bachelor’s course used Twitter to share their reflections about personal learning and their ideas relating to the course materials (Preston et al., Citation2015). The students found that this reflection assignment helped them engage with the course material. In addition, viewing their peers’ reflections raised the students’ awareness of perspectives or content that they had missed. Also, Mercier et al. (Citation2015) found that instructors and students who were using Twitter in an undergraduate course gained insight into group discussion activities during class, thus ensuring that ideas emerging within group could enter whole-class conversations. This study found that using Twitter within classroom activities increased the amount of on-task talk, allowed instructors to redirect discussions during activities and provided the possibility of using the shared representation of tweets to direct the final conversation of the whole class, which allowed for more focused discussions. In another study where the online whiteboard Flinga.fi was used in a university lecture, students shared ideas and opinions through written posts and then subsequently justified, elaborated on and explained these perspectives (Ludvigsen et al., Citation2019). This study identified the potential to increase interactions among students and between students and lecturers, encourage creative knowledge processes through dialogue and create new, rich opportunities to reflect on concepts and developing arguments. An additional study showed that using a response system in combination with peer discussions engaged students, and the teacher could follow up on their answers, asking them to provide further reasons or explanations (Egelandsdal & Krumsvik, Citation2019). The teacher created tension between the students’ ideas and those of the discipline by engaging with the students’ answers (i.e. discussing different perspectives, relating ideas to one another or comparing and contrasting ideas). This can create opportunities for students to draw connections between their everyday views and those of the course, and to become more aware of different perspectives regarding a topic (Egelandsdal & Krumsvik, Citation2019). Meanwhile, using a microblogging tool called Socius, secondary high students from another study wrote short summaries that were displayed on a shared screen in the classroom (Rasmussen & Hagen, Citation2015). The study showed that this microblogging technology made students’ thinking visible to other participants and opened up new possibilities for engaging in classroom dialogues. Furthermore, it increased participation and seemed to bring the students’ and teachers’ different understandings of the topic closer together, as the teacher elaborated on whole-class discussions emerging from the students’ own work. More recent studies have also found the use of microblogging to mediate the uptake of student contributions (Omland & Rødnes, Citation2020) and to be productive in mediating and connecting learning activities, such as peer talks and whole-class conversations (Frøytlog & Rasmussen, Citation2020; Omland, Citation2021).

Finally, we consider technology beyond microblogging that can be used in a co-located manner to promote oral dialogue in classrooms. By using the Promising Ideas Tool, a Knowledge Forum (Scardamalia & Bereiter, Citation2006) extension, Grade 3 students selected promising ideas from their group’s written online discourse, then aggregated and displayed their selections to support collective decision making regarding the most promising directions for subsequent work (Chen et al., Citation2015). The selected ideas would become the focus of class discussions and subsequent knowledge‐building efforts. The study showed that elementary students achieved significantly greater knowledge advances than students who were not engaged in the identifying and judgement of promising ideas and discussions. In a final study, Grade 4 students used Knowledge Forum for three successive school years (Zhang et al., Citation2009). The researchers then analysed the students’ awareness of peer contributions as the students built their complementary contributions by referencing the ideas of others. Their distributed engagement emerged and extended the fixed student groups, supported by Knowledge Forum, connecting them to a broader network of students and ideas. This study ultimately suggested that a flexible and opportunistic collaboration framework can produce high-level collective cognitive responsibility and dynamic knowledge advancement.

Another type of technology that combines written and oral dialogue to promote productive interactions among students is the interactive whiteboard (IWB). An exploratory paper considered the IWB a dialogic space used for reflection, which may create opportunities for learners in primary schools to generate, modify and evaluate new ideas through multimodal interaction, along with talk (Hennessy, Citation2011). The author pointed to visible, dynamic and constantly evolving digitally represented knowledge artefacts (e.g., text, images or figures) on the IWB that constitute temporary records of activity. These are functioning as supportive resources for students’ emerging thoughts and ideas, rather than the finished products of the students’ discussions. In another study, students in primary classrooms collaborated in a variety of science activities using an IWB, and they could engage effectively in the collective learning experience, called the shared dynamic dialogic space (Kershner et al., Citation2010). The study suggested that the conditions for success, which need to be established in the classroom, include the children’s joint understanding of the task, their positive motivation and responsibility for learning, and their active support for each other. In Talk Factory, a software designed to model and represent exploratory talk on an IWB, teachers could evaluate and monitor the students' talk in relations to the class talk rules. This tool changed the nature of students’ dialogue and resulted in more exploratory talk (Kerawalla et al., Citation2013).

What emerges from these studies, first and foremost, is that microblogging technology can extend the possibilities for students to participate in both whole-class and group interactions. Furthermore, the possibility of combining short written messages with oral discussions can make students’ ideas visible, enabling them to travel more easily between whole-class and group conversations. As most microblogging studies have been conducted within higher education, less is known about how microblogging can be adopted in classrooms with younger students. As far as we know, there are no contemporary studies that investigate how teachers’ educational design of a particular microblogging activity intended to develop students’ critical thinking can support students as they engage in productive interactions. More focus on the value of the practices and practical procedures linking productive interactions and microblogging technology is necessary to encourage primary and lower secondary school teachers to adopt such practices (Mercer et al., Citation2019). Thus, we advance the research by investigating how one teacher embedded microblogging into her educational design to promote productive interactions within the larger context of developing her students’ critical thinking.

Educational design for productive interactions

When embedding microblogging in an educational design, it is crucial to use a clear pedagogical approach, with dialogic pedagogy proving especially valuable in this respect (Major et al., Citation2018). Dialogic pedagogy focuses on the ongoing process of interactive and recursive meaning making among participants, promoting talk as a powerful tool to foster students’ thinking, learning and problem-solving skills (Alexander, Citation2004; Wegerif et al., Citation2019). One specific kind of talk considered to have great educational value is exploratory talk (Barnes & Todd, Citation1977). This is talk in which all members are invited to contribute, and all relevant information is shared. Moreover, everyone’s ideas are respected and considered, and everyone is asked to make their reasons clear. In this type of talk, challenges and alternatives are made explicit and negotiated, and before making a decision, the participants seek to reach agreement. Implicit in exploratory talk is the development of critical thinking, which occurs because it makes thinking visible and offers exposure to different perspectives. Through exploratory talk, students can become involved in each other’s thinking as they develop their own (Littleton & Mercer, Citation2013).

To use language to generate productive interactions, students need explicit guidance and training. One strategy that ensures students are aware of appropriate ways to interact is developing ‘talk rules’ with them that highlight the principles of participating, reasoning, challenging ideas and collaboratively making decisions (Gillies, Citation2016; Mercer et al., Citation2004). The development of, and explicit focus on, talk rules promote both students’ and teachers’ awareness of what have been termed dialogic intentions in the lesson (Warwick et al., Citation2020). In addition to explicitly being taught, students benefit from practising these talk features through social interactions (Littleton & Mercer, Citation2013). Consequently, the activity itself needs to be carefully considered if the intent is to promote productive interactions; thus, one key point is to design an activity that includes a reason to talk together. Therefore, the design of the activity should require all students to contribute and share information, respect each other’s ideas, ensure the students have a shared understanding of the purpose of the activity and are aware of how to use talk appropriately (e.g., by explicitly focusing on talk rules). Hence, when embedding microblogging technology in dialogic pedagogy, teachers must determine how the tool can serve the educational goals and how to enact the relevant functions within the tool. We investigate this further in our article by focusing on how a teacher’s educational design was realised through and with technology when students explored the distinction between facts and opinions using a microblogging tool.

Method

Context of the study

The school involved is in the centre of a large Norwegian city, and the class consisted of 23 students (aged 12–13). The class participated in the design-based research project DiDiAC, focusing on how teachers can integrate the microblogging tool Talkwall into their practices to support student participation in productive interactions. The teacher was unfamiliar with microblogging for educational activities prior to this project, but she had previous experience with other digital tools. The students in the class had individual iPads and were familiar with using them both in the classroom and at home. The DiDiAC project included four introductory teacher–researcher workshops and collaborative planning meetings, during which teachers and researchers discussed how Talkwall could be embedded in learning activities. These discussions occurred prior to three observed lessons; after these lessons, the teachers and researchers discussed their experiences. During these meetings, the teachers and researchers also collaboratively explored the elements of the ‘Thinking Together’ approach (Mercer et al., Citation1999), such as developing talk rules and embedding Talkwall in an educational design to promote productive interactions. Thus, the teacher examined in this article was in the process of developing her thinking about dialogic pedagogy.

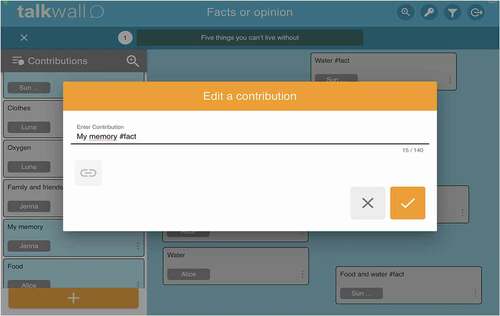

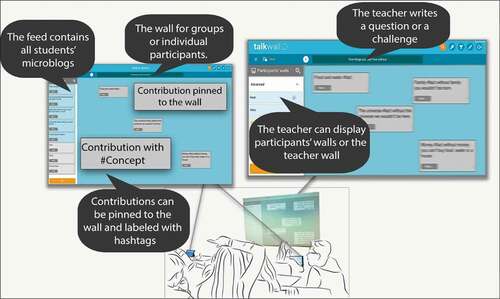

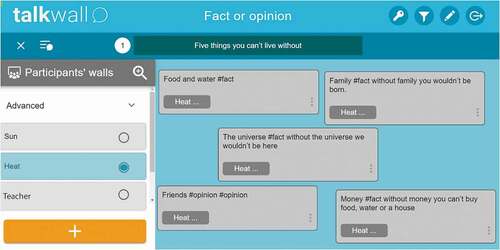

Talkwall () is designed to support co-located interactions through both oral and written communication, and it is specifically based on a research-based understanding of dialogic pedagogy as it is established in the Thinking Together approach (Mercer et al., Citation1999). Talkwall was developed through a 10-year co-design process, in which its design was adapted according to teacher experiences and feedback. In this article, we consider ‘bridging concepts’ (further elaborated in Smørdal et al., Citation2021) to inhabit a ‘middle ground’ between educational theory and teachers’ educational design. The following bridging concepts (listed below in italics) can help unveil and articulate untried design opportunities and connect theoretical concepts and dialogic pedagogy with the affordances of Talkwall

A contribution is a microblog or digital representation of an idea, presented as a short message with limited characters (140–500) that enhances, rather than replaces, oral dialogue.

The feed of microblogs provides a mutual awareness of all ideas contributed to Talkwall. The feed is shared on all participants’ devices and offers a means for students to share their contributions with their peers.

The wall allows microblogs to be promoted from within the feed and represents them on a spatially organised surface.

The space for the teacher provides access to all participants’ walls and enables the teacher to display any wall to the class.

Hashtags (#) can be added by the participants to contributions, for example, to follow select topics or organise different points of view. Both the teacher and students can filter the microblogs with the hashtags.

Figure 1. Talkwall representation of the student wall to the left and the teacher wall to the right. The figure shows contributions, or microblogs, that are selected from the feed and pinned to the wall.

During a lesson, a main Talkwall window is displayed at the front of the class on a projector or large screen and is usually controlled by the teacher. The students have their own individual or group walls that are accessible and controllable using any device with a web browser.

Data collection and analytical work

The lesson analysed for the purpose of this article was selected from the DiDiAC project dataset for two main reasons. First, the teacher embedded several functionalities in Talkwall in her educational design, such as the deliberate hashtagging of all contributions, which we did not see in any other lessons in our dataset. Second, Talkwall was used for two purposes: homework and lessons. During the entire lesson, Talkwall was also used for both whole-class and group interactions.

We consider the video-recorded classroom interactions (67 minutes of the whole class and 65 minutes focusing on one group) and the Talkwall blogs as our primary data. Field notes, one audio-recorded teacher–researcher meeting (40 minutes) and the teacher’s plan for the lesson supplemented and contextualised the primary data.

Studies addressing the sequential nature of the learning process (Rasmussen, Citation2012) emphasise learners’ interactions across situations. To show the role of technology in the classroom and investigate both how interactions are stimulated and what precedes them, there is a need to provide a narrative of the whole lesson (Kershner et al., Citation2020). Thus, our analysis involves two levels: the trajectory level and the interactional level. The levels of our analysis inform each other to provide insights on how knowledge and activities become relevant at specific times and stay relevant throughout an activity (deSousa & Rasmussen, Citation2019).

At the trajectory level, we characterised the teacher’s design of the learning activity and structured the lesson into sequences. Inspired by thematic analysis, we identified patterns within the data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). During the process of repeatedly viewing the video-recorded lesson, we described and categorised how the lesson unfolded over time. Here, we identified how the teacher planned and enacted the activities, including how she embedded Talkwall in the educational design.

We examined the teachers’ and students’ oral interactions and their interactions with Talkwall to determine how the teacher’s educational design fostered student engagement in productive interactions. The video recordings from the classroom were transcribed verbatim in Norwegian and translated into English for the present article. The Talkwall blogs were integrated into the transcript as well to determine the role of the written contributions in relation to the face-to-face interactions. More specifically, we analysed tabularised transcripts of video recordings, in which a select number of automatically logged Talkwall interactions were integrated based on their timestamps. The Talkwall interactions we considered were ‘create contribution’, ‘edit contribution’, ‘promote contribution’ and ‘teacher display group wall’. Together, the video recordings and the Talkwall log allowed us to investigate the dialogic characteristics of productive interactions and the role of Talkwall in these interactions.

The excerpts in the Results section were selected for their relation to the research questions. In particular, the excerpts illustrate the educational design of the Talkwall activity, describing how it was used to promote productive interactions and how it was picked up on by the students. The excerpts presented in the Results section include contributions in Talkwall, represented as simplified versions of how they appear on the students’ screens. In the article, the students and the teacher are anonymised, and we have followed appropriate research ethics and privacy guidelines (Norwegian Data Protection Services, Citationn.d.).

Limitations

This is a qualitative study intended to explore how to embed a microblogging tool in a lesson to engage students in productive interactions. However, by identifying some important aspects of the teachers’ educational design, we offer insight into the students’ interactions in situations that may support their development of dialogic skills, which in turn can support the development of their critical thinking.

Results

The teacher’s educational design

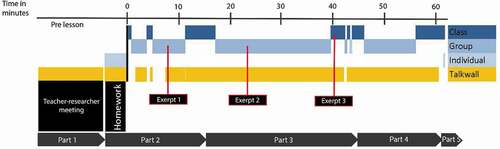

We begin by describing and analysing at the trajectory level what characterised the teacher’s educational design of the Talkwall activities. We have divided the activities into five main parts, as described in .

Figure 2. Representation of the educational design at the trajectory level. The teacher–researcher meeting was an unstructured planning meeting lasting approximately 40 minutes, and occurred a few days before the lesson. The lesson was 67 minutes long and alternated between group and whole-class activities, with a short individual activity at the end and an individual homework activity. Talkwall was actively used during most of the lesson.

Part one consisted of the teacher–researcher meeting. Talkwall was used during the meeting for demonstrations, and the Talkwall functionalities were discussed in relation to the planned subject-specific activity.

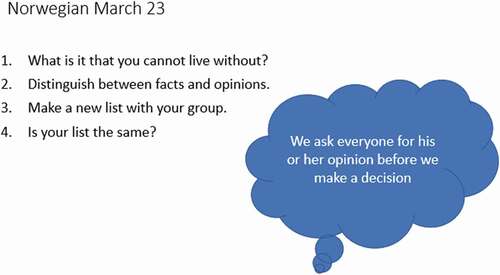

Part two started with a homework assignment in which the students contributed to Talkwall five things that they cannot live without. When the lesson began, the teacher introduced the lesson plan and the dialogic intention (). She reminded the students about the class talk rules (Appendix A1) and explicitly stated how the students could use the class talk rules in their discussions. The students were also provided with the sentence openers ‘Why did you choose that?’ and ‘Can you say more about that?’

Figure 3. Lesson plan with four main activities and the dialogic intention in the speech bubble (authors’ translation).

In part three, the teacher and students explored some differences between facts and opinions. Then the students were instructed to label all the Talkwall blogs in the feed as either #opinion or #fact. During this group activity, the teacher explicitly pointed out that the students must give reasons for their hashtags, and they must reach agreement as a group on their choice. They were also provided with a sentence opener that was visually displayed on the whiteboard: ‘Why is this a fact/opinion?’ The group activity was followed by a whole-class discussion using Talkwall.

In part four, the teacher introduced the activity, which was to make a new list of five things that each student cannot live without. The students had to reach an agreement within the group before promoting the new list of contributions to the group wall. Next, the students and the teacher discussed the new lists as a whole class using Talkwall. The last part was an individual reflective activity, ending with the students writing a new list and reflecting on whether they changed their minds.

To summarise, the learning activities involved both group and whole-class interactions using Talkwall. The teacher’s dialogic intention for the lesson was for all students to be asked their opinions and provide reasons for their answers. The Talkwall activities were designed to accomplish this intention.

The students’ uptake of the educational design

The students and the teacher used Talkwall throughout the lesson, which was highly interactive (as illustrated in ). The students individually contributed to Talkwall through their homework, and groups of students contributed during the lesson. They used several Talkwall functions; contributions were created, promoted, edited and moved from the feed to the wall, where they were spatially organised. Throughout the lesson, the teacher used the teacher space in Talkwall to select six of the nine group walls for display on the large wall to support whole-class discussions. Moreover, all microblogs were extended during the lesson with a hashtag.

The hashtagging activity in Talkwall required the students to read and discuss several of their peers’ contributions to decide whether to use the #fact and/or #opinion hashtags. We have selected three excerpts from different parts of the lesson to analyse this aspect of the students’ uptake of the educational design. The excerpts are translated from Norwegian by the authors and presented with standard punctuation. Double parentheses contain the analyst’s comments or descriptions and (.) indicates brief intervals or pauses between the end of a word and the beginning of the next.

Excerpt 1: ‘Why did you select money?’

This excerpt is from part two of the trajectory presented in . We focus on one group with two students, Alice and Leo. In the excerpt, Alice presents to Leo the five things that she has decided that she ‘cannot live without’. The iPad displays their group Talkwall, with Alice’s contributions in the feed.

Alice starts by listing her five things. Leo answers ‘okay’. The short pause and the fact that Alice turns to ask the teacher what they should do next indicate that this is the end of their conversation. The teacher then uses Talkwall to access Alice’s microblogs by scrolling the feed. She finds one of Alice’s microblogs – ‘Friends’ – and encourages the two students to provide reasons by saying, ‘So, why did you choose friends?’, referring to the sentence openers introduced earlier in the lesson. Alice picks this up, and in the remainder of the transcript we see that, not only does she give reasons for her arguments (turns 7 and 8), but Leo also follows up by requesting reasons (turn 9). Note that Leo uses the Talkwall feed in the same way as the teacher (in turn 4) by asking why Alice chose ‘money’. Alice answers by referring to another student’s contribution in the Talkwall feed – ‘Clothes’ – to support her argument, saying ‘without money you cannot buy clothes’.

This brief excerpt shows some important functions of microblogging. First, we see that the teacher can easily access the students’ contributions through Talkwall as she makes her rounds to support group work in the classroom. Second, when the students’ peer-group talk fades out (turns 2–3 and 9), access to Talkwall blogs in the feed seems to play an important role in prompting the students to talk and stay on task. Third, access to other students’ contributions in the feed brings new perspectives to the conversation and ensures that ideas are shared with the whole class. Important to note is that the students (supported by the talk rules, sentence openers and Talkwall) also challenge each other (turn 9) and attempt to make their reasons clear (turn 10), which are important features of exploratory talk.

Excerpt 2: #Fact or #opinion

We now turn to part three of the lesson, in which the activity requires the students to hashtag as many contributions as they can within the time provided. Alice and Leo need to agree on the hashtag before hashtagging the contributions. They read other students’ microblogs in the feed, starting from the top and scrolling through the first few. The iPad displaying Talkwall is placed between them, and both look at the contributions in the feed while Alice scrolls.

Alice scrolls the feed and comments on what she is reading. She points to ‘Water’ and ‘Food’ and states that these are ‘facts’. Leo nods. Without hashtagging these, she continues to scroll before she stops at the contribution ‘My memory’. The next exchange suggests that Leo does not think ‘My memory’ should be classified as a fact (turns 3 and 4). Alice, in what appears to be a surprised tone, turns to Leo and asks ‘No?’ Her invitation does not follow the conversation openers as in excerpt 1; rather, her question appears authentic. In what follows, Alice argues why you cannot live without your memory, while Leo, in what seems to be a humorous tone or an attempt to save face, challenges and argues against her. In turn 12, after a few moments of silence, Leo says ‘oh’. In turn 14, we see that Alice invites Leo to conclude that they should label the contribution with #fact.

This excerpt demonstrates that the feed, which includes all groups’ contributions, exposes the students to more alternatives and different perspectives. We see that when ‘My memory’ arises in the feed, which was a contribution made by another student, Alice and Leo discuss both fact and opinion before reaching an agreement. The design of the activity is central to how the students interact, both within the group and in the whole class. The interaction with other students’ ideas is embedded in the design of the hashtag activity, which encourages the students in the group to engage with all other students’ contributions. Additionally, the design of the activity encourages the students to agree on a joint decision; to support this goal, the teacher instructed the students to give reasons for their answers (part 3). The hashtag activity in Talkwall also distributes the students’ ideas/judgements about whether the contribution is a fact or opinion to the rest of the class. Importantly, this activity prompts students to distinguish between facts and opinions. In this case, we see that the distinction is not clear-cut for these young students. Making distinctions and providing reasons are important to critical thinking. A simple task, such as the one we exemplify, might prove an entry point for making more advanced distinctions and backing them up with reasons later.

Excerpt 3: ‘Did you all agree?’

This excerpt is from part three of the lesson. The whole class turns their attention to the whiteboard in front of the classroom. The teacher, standing before them, presents the participants’ walls. As we examine excerpt 3, we see that she selects and displays one group wall () to the whole class.

Figure 5. A representation of the group wall, particularly the group ‘Heat’. On their wall, they have pinned and hashtagged five microblogs.

The excerpt starts with the teacher asking Ron to share with the class the discussion he had with his group. Alex, from another group, eagerly interrupts, but is stopped. Ron gives the reason for why he and his group labelled family as ‘fact’, saying, ‘Without a family you would not have been born.’ The teacher presses on, asking if the group managed to reach an agreement. Building on each other’s utterances in turns 7, 8 and 9, Sarah and Liam argue that family should have been hashtagged as ‘opinion’. In turn 11, the teacher selects Alex to elaborate further on why he thinks family ‘is an opinion’.

The excerpt demonstrates how contributions from one group are picked up and function as visual support for whole-class discussions. The teacher space in Talkwall provides the teacher access to the participants’ walls. This enables the teacher to distribute the results from the group discussions and initiate a whole-class discussion based on the group talk, aided by visual support from Talkwall. In addition, we see that she presses on and directly asks about the groups’ previous discussion. We also see that Alex, who was not part of this group, eagerly elaborates on his stance. The visual support enables focused discussion, providing the students a shared or collective space for class dialogue (Wegerif et al., Citation2019).

The design of this activity ensured that all the students participated in and contributed to the group during the whole-class discussions. As such, the students’ thinking was shared and travelled via the ‘feed’, the Talkwall contributions and the oral dialogue. By displaying the groups’ walls with microblogs and hashtags to the whole class, the students’ participation in the group extended into the whole-class discussion, despite the fact that they did not directly contribute to the whole-class discussion. This means that even those who did not participate orally did so through the written contributions that they produced during group discussions or homework assignments.

Further, the group discussions became more permanent, as the students used Talkwall to document their work. Doing so seemed to make the group discussions more targeted and focused, as we demonstrated in the first example, because the students had access to a pool of their peers’ ideas. Moreover, Talkwall seems to support the teacher in using strategies that promote exploratory talk (Mercer & Littleton, Citation2007).

As we have seen, Talkwall and what we consider bridging concepts made possible an educational design that enabled (1) all students to contribute and share their ideas and (2) all students’ opinions and ideas to be considered, exposing the students to different perspectives. Moreover, the educational design, infused with dialogic pedagogy, promoted exploratory talk and enabled students to challenge each other, ask everyone to clarify their reasons and reach agreements as a group. These are important aspects in the development of critical thinking.

Discussion

We now relate the analysis of the teacher’s educational design and the students’ uptake of this design to the key themes that emerged from our analysis.

Permanence – the written and oral co-constitute

We observed that the educational design, in particular the #fact and #opinion labelling activity, encouraged the students to interact and think critically about their peers’ ideas. Embedding Talkwall in this activity visualised the ideas of others over time, representing these ideas in the feed and enabling them to be edited. We believe that the permanence of the contributions and the fact that the contributions are tangible and available for selection and organisation on the wall made them available to other students to build upon. The permanence of the contributions enabled the students to have more focused discussions as well (Mercier et al., Citation2015). Previous studies report similar results for students engaged in the identifying and judgement of their peers’ ideas and referencing the ideas of others using Knowledge Forum (Chen et al., Citation2015; Zhang et al., Citation2009). In the educational design, the distinction between facts and opinions was not clear-cut and relied on everyday concepts. Hence, the students were given the opportunity to practise the elements of exploratory talk in an authentic context (Mercer et al., Citation2019). Other studies regard this type of educational design as useful when teachers wish to undertake dialogic pedagogy and enhance interactions productive to learning (Mercer et al., Citation1999).

Try out ideas safely

The educational design in this study encouraged students to discuss and agree as a group before deciding on the wording of the contribution that would be shared in the whole-class discussion. This design was also accompanied by the ‘talk rules’ about joint decision making (Mercer et al., Citation2019) that were co-developed in the class and explicitly referenced by the teacher. We also observed that the teacher’s educational design gave students time to try out their ideas in small groups before sharing their written ideas, which can make participation in whole-class interactions more available to all students.

Concurrency – multiple participation options

Writing a contribution in Talkwall can be done concurrently; hence, students can contribute their answers without being interrupted or while waiting for their turn, which gives them time to reply with thoughtful responses. This can contribute to more equal participation than is attainable through face-to-face, whole-class discussions alone (Frøytlog & Rasmussen, Citation2020; Omland, Citation2021).

Teacher awareness

Embedding Talkwall in the activity allowed the teacher to direct the whole-class discussions in a way that enhanced elaboration, built on the groups’ discussions and mediated the uptake of student contributions (Mercier et al., Citation2015; Omland & Rødnes, Citation2020). For example, when the students’ contributions were displayed on the wall, there was often a need for more thorough explanations because of the short format. A typical strategy for this teacher, when considering the students’ contributions on the group walls, was to ask follow-up questions such as ‘Can you say more about that?’ or ‘Did you all agree on this?’ These questions seemed very natural to ask in the context of the whole-class discussions involving Talkwall. This indicates that using microblogging within the context of dialogic pedagogy and in combination with face-to-face communication can support teachers’ work in facilitating student efforts when they practise taking part in exploratory talk (Mercer et al., Citation2019).

Wall talking

Talkwall is a microblogging tool that also has IWB properties, such as being a ‘shared dynamic dialogic space’ (Kershner et al., Citation2010) and a focal point for learners’ emerging thinking (Hennessy, Citation2011). The educational design made use of the two representational means in Talkwall, the feed and the wall, to assist the students’ talk and their collective understanding, to provide access to other ideas that extend the discussions beyond the groups, and to support the students as they deepened the discussion by challenging ideas presented in the feed. The teacher used these representational means by displaying either the teacher wall or one of the group walls on the classroom’s large screen to focus the entire class’s attention. We observed that sharing written contributions between groups widened the dialogic space by providing access to more ideas and different perspectives. Moreover, as the lesson design encouraged the students to select other ideas and label them with hashtags, the dialogic space deepened as they questioned and challenged the ideas of other groups (Cook et al., Citation2019; Warwick et al., Citation2020).

Conclusion

The findings from this study show that educational design involving microblogging can provide new possibilities for peer interactions by systematically enabling students to (1) access more of their peers’ ideas; (2) produce and discuss collective ideas; and 3) contribute to and participate in exploratory talk. In particular, the creative use of hashtags proved a suitable mechanism for facilitating peer interactions that promote critical thinking. The contributions, the feed, the wall, the space for the teacher and the hashtags, all termed bridging concepts (Smørdal et al., Citation2021), were key elements of the educational design, intended to enable the students to explore the distinction between facts and opinions, and to promote exploratory talk. Educational research has shown that engagement in dialogue can stimulate contrasting ideas, support students in focusing on the most relevant issues in information sources and provide them examples of the skills that underlie critical thinking (e.g., Ferguson & Bubikova-Moan, Citation2019). Our research, which empirically investigated the teacher’s educational design and the students’ uptake – in which participants are encouraged to engage critically yet constructively with each other’s ideas – suggests that peer-group interactions can be developed to improve students’ critical thinking. Designing educational activities to use digital technology can engage young students in activities that are known to foster critical thinking skills. We argue for dialogic pedagogy as a way of increasing learning opportunities (e.g., Howe & Abedin, Citation2013). As our study demonstrates, the students practised several skills that are known to be educationally productive for learning, including asking questions, giving reasons, providing evidence and elaborating on others’ ideas in activities enabled by digital technology.

Ethical approval statement

This research was reported to and evaluated by the Norwegian Data Protection Services [NSD number 48,130].

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the teachers and students who participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anja Amundrud

Anja Amundrud is a doctoral research fellow at the Department of Education, University of Oslo. She has a background as a primary school teacher, and her PhD research focus is on teaching and learning with new technologies. Amundrud is also interested in the design and development of digital resources.

Ole Smørdal

Ole Smørdal is a researcher at the Department of Education, University of Oslo. His background is in computer science. He has long experience in the intersection between design, education and computer science. He has specialised in research that is based on practice partnerships and adopts design-based and participatory methods in such collaborations.

Ingvill Rasmussen

Ingvill Rasmussen is Professor at the Department of Education, University of Oslo. Her background is educational psychology, and her research focus is on talk and collaboration and how digital technologies transform learning practices. Rasmussen designs digital tools in collaboration with teachers and technology developers to support learning in formal schooling.

References

- Alexander, R. J. (2004). Dialogic Teaching (York: Dialogos).

- Barnes, D., & Todd, F. (1977). Communication and learning in small groups. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Chen, B., Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (2015). Advancing knowledge‐building discourse through judgments of promising ideas. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 10(4), 345–366. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-015-9225-z

- Cook, V., Warwick, P., Vrikki, M., Major, L., & Wegerif, R. (2019). Developing material-dialogic space in geography learning and teaching: Combining a dialogic pedagogy with the use of a microblogging tool. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 31, 217–231. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2018.12.005

- deSousa, F., & Rasmussen, I. (2019). Productive disciplinary engagement and videogames. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 14(3–4), 99–116. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18261/.1891-943x-2019-03-04-02

- Egelandsdal, K., & Krumsvik, R. J. (2019). Clicker interventions at university lectures and the feedback gap. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 14(1–2), 70–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18261/.1891-943x-2019-01-02-06

- Ferguson, L. E., & Bubikova-Moan, J. (2019). Argumentation as a pathway to critical thinking. In B. Garssen, D. Godden, G. R. Mitchell, & J. H. M. Wagemans (Eds.), Proceedings of the Ninth Conference of the International Society for the Study of Argumentation (pp. 352–362). Sic Sat.

- Ferguson, L. E., & Krange, I. (2020). Hvordan fremme kritisk tenkning i grunnskolen? [How to promote critical thinking in primary school?]. Norsk Pedagogisk Tidsskrift, 104(2), 194–205. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18261/.1504-2987-2020-02-09

- Frøytlog, J. I. J., & Rasmussen, I. (2020). The distribution and productivity of whole-class dialogues: Exploring the potential of microblogging. International Journal of Educational Research, 99, 101501. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.101501

- Gao, F., Luo, T., & Zhang, K. (2012). Tweeting for learning: A critical analysis of research on microblogging in education published in 2008–2011. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(5), 783–801. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2012.01357.x

- Gillies, R. M. (2016). Cooperative learning: Review of research and practice. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 41(3), 3. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2016v41n3.3

- Hauge, T. E., Lund, A., & Vestøl, J. M. (2007). Undervisning i endring: IKT, aktivitet, design [Teaching in transformation: ICT, activity, design]. Abstrakt forlag.

- Hennessy, S. (2011). The role of digital artefacts on the interactive whiteboard in supporting classroom dialogue. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 27(6), 463–489. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2011.00416.x

- Howe, C., & Abedin, M. (2013). Classroom dialogue: A systematic review across four decades of research. Cambridge Journal of Education, 43(3), 325–356. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2013.786024

- Howe, C., Hennessy, S., Mercer, N., Vrikki, M., & Wheatley, L. (2019). Teacher–student dialogue during classroom teaching: Does it really impact on student outcomes? Journal of the Learning Sciences, 28(4–5), 462–512. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2019.1573730

- Kerawalla, L., Petrou, M., & Scanlon, E. (2013). Talk factory: Supporting “exploratory talk” around an interactive whiteboard in primary school science plenaries. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 22(1), 89–102. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2012.745049

- Kershner, R., Hennessy, S., Wegerif, R., & Ahmed, A. (2020). Research methods for educational dialogue. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Kershner, R., Mercer, N., Warwick, P., & Kleine Staarman, J. (2010). Can the interactive whiteboard support young children’s collaborative communication and thinking in classroom science activities? International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 5(4), 359–383. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-010-9096-2

- Littleton, K., & Mercer, N. (2013). Interthinking: Putting talk to work. Routledge.

- Ludvigsen, K., Ness, I. J., & Timmis, S. (2019). Writing on the wall: How the use of technology can open dialogical spaces in lectures. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 34, 100559. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2019.02.007

- Lund, A., & Hauge, T. E. (2011). Designs for teaching and learning in technology-rich learning environments. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 6(4), 258–272. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18261/1891-943X-2011-04-05

- Major, L., Warwick, P., Rasmussen, I., Ludvigsen, S., & Cook, V. (2018). Classroom dialogue and digital technologies: A scoping review. Education and Information Technologies, 23(5), 1995–2028. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-018-9701-y

- Mercer, N., Dawes, L., Wegerif, R., & Sams, C. (2004). Reasoning as a scientist: Ways of helping children to use language to learn science. British Educational Research Journal, 30(3), 359–377. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920410001689689

- Mercer, N., Hennessy, S., & Warwick, P. (2019). Dialogue, thinking together and digital technology in the classroom: Some educational implications of a continuing line of inquiry. International Journal of Educational Research, 97, 187–199. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2017.08.007

- Mercer, N., & Littleton, K. (2007). Dialogue and the development of children’s thinking: A sociocultural approach. Routledge.

- Mercer, N., Wegerif, R., & Dawes, L. (1999). Children’s talk and the development of reasoning in the classroom. British Educational Research Journal, 25(1), 95–111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192990250107

- Mercier, E., Rattray, J., & Lavery, J. (2015). Twitter in the collaborative classroom: Micro-blogging for in-class collaborative discussions. International Journal of Social Media and Interactive Learning Environments, 3(2), 83–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSMILE.2015.070764

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2018). How people learn II: Learners, contexts, and cultures. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17226/24783

- Norwegian Data Protection Services. (n.d.). Norsk senter for forskningsdata. NSD. https://nsd.no

- Omland, M., & Rødnes, K. A. (2020). Building agency through technology-aided dialogic teaching. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 26, 100406. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2020.100406

- Omland, M. (2021). Technology-aided meaning-making across participation structures: Interruptions, interthinking and synthesising. International Journal of Educational Research, 109, 101842. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2021.101842

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2018). The future of education and skills education 2030. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/about/documents/E2030%20Position%20Paper%20(05.04.2018).pdf

- Preston, J. P., Jakubiec, B. A., Jones, J., & Earl, R. (2015). Twitter in a Bachelor of Education course: Student experiences. LEARNing Landscapes, 8(2), 301–317. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.36510/learnland.v8i2.710

- Rasmussen, I., & Hagen, Å. (2015). Facilitating students’ individual and collective knowledge construction through microblogs. International Journal of Educational Research, 72 (1), 149–161. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2015.04.014

- Rasmussen, I. (2012). Trajectories of participation: Temporality and learning. In N. M. Seel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the sciences of learning Part 20/T. (pp. s3334–s3337). Springer.

- Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (2006). Knowledge building: Theory, pedagogy, and technology. In K. Sawyer (Ed.), Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 97–118). Cambridge University Press.

- Smørdal, O., Rasmussen, I., & Major, L. (2021). Supporting classroom dialogue through developing the Talkwall microblogging tool: Considering emerging concepts that bridge theory, practice and design. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy 16(2), 50-64 . https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18261/.1891-943x-2021-02-02

- Tang, Y., & Hew, K. F. (2017). Using Twitter for education. Beneficial or a waste of time? Computers & Education, 106, 97–118. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.12.004

- Utdanningsdirektoratet. (2018, November 26). Hva er fagfornyelsen? [What is the new Norwegian Curriculum?]. Utdanningsdirektoratet. https://www.udir.no/laring-og-trivsel/lareplanverket/fagfornyelsen/nye-lareplaner-i-skolen

- Utdanningsdirektoratet. (2020). Overordnet del – Verdier og prinsipper for grunnopplæringen [Norwegian Curriculum – Norms and guidelines]. Utdanningsdirektoratet. https://www.udir.no/lk20/overordnet-del/

- Warwick, P., Cook, V., Vrikki, M., Major, L., & Rasmussen, I. (2020). Realising “dialogic intentions” when working with a microblogging tool in secondary school classrooms. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 24, 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2019.100376

- Wegerif, R., Mercer, N., & Major, L. (2019). Introduction to the Routledge international handbook of research on dialogic education. In N. Mercer, L. Major, & R. Wegerif (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of research on dialogic education (pp. 1–8). Routledge.

- Zhang, J., Scardamalia, M., Reeve, R., & Messina, R. (2009). Designs for collective cognitive responsibility in knowledge-building communities. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 18(1), 7–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10508400802581676

Appendix A1.

Talk rules

Original (Norwegian)

Jeg har respekt for andres meninger.

Jeg er forberedt på å forandre mening, det viser at jeg lytter til gode argumenter.

Jeg stiller spørsmål ved forklaringer jeg ikke synes er gode nok.

Alle skal bli spurt om hva de mener.

Jeg ser og lytter til personen som snakker.

Gruppen diskuterer alle alternativer før de bestemmer seg.

English translation

Show respect for others’ opinions.

Prepare to change your mind, which means that you are listening to good arguments.

Ask questions if you think someone’s explanations are not good enough.

Ask everyone for their opinion.

Look at and listen to the person who is talking.

The group discusses all alternatives before making a decision.