ABSTRACT

This article discusses the digital transformation of higher education in Egypt as distance education was abruptly implemented in early 2020. For eight months after that, 38,784 media items were crowdsourced reflecting spontaneous opinions, expectations, sentiments and experiences with the new digital learning. This random sample was drawn from digitised and online news articles, TV and radio programmes, and social media posts by students, parents, academics, education experts and media professionals who represented the media and public opinion. This article recommends the people-process-technology framework for the digital transformation of higher education based on previous research and digital archival research findings. It highlights its components and integrated approach, and discusses its implementation in Egypt and developing countries. Moreover, the framework will be the foundation for further research in higher education’s digital transformation, operations, human resources and information technology.

Introduction

Educational technologies and the social, physical, psychological and pedagogical contexts in which learning occurs changed abruptly as the COVID-19 pandemic forced the closure of universities in early 2020. The digital transformation to distance learning affected student achievement and attitudes. The pandemic caused disruption that left students and teachers suffering, particularly in developing countries, struggling, hurrying and hoping to catch up.

A literature review showed that many studies had produced lists of factors impacting the digital transformation of higher education without a guiding framework (García-Morales et al., Citation2021; Maltese, Citation2018; Marks et al., Citation2021). This article introduces the people-process-technology (PPT) framework used by the information and communication technology industry to transform organisations digitally (Marquez et al., Citation2013).

After reviewing the literature in light of the PPT framework, this study used digital archival research to listen to and glean stakeholders’ expectations, frustrations and aspirations in the digital transformation of higher education in Egypt themed along the people-process-technology perspectives. Then the article discusses the inevitable implementation of digital transformation in higher education in light of the stakeholders’ opinions and guided by the PPT framework.

Digital transformation in higher education

Digital transformation (DT) in higher education has been thoroughly deliberated and articulated in the literature. DT is fundamentally about change and involves people, processes, strategies, structures and competitive dynamics (Rodrigues, Citation2017). DT goes well beyond the de-materialisation of processes, encompassing new technologies (cloud, social media, mobile and big data analytics) to promote new services and re-define business models and innovative interactions with its users (Faria & Nóvoa, Citation2020). The DT of the university education system should have a broader focus and must include the modernisation of IT architecture management, which could contribute to structuring innovation efforts in education (Kaminskyi et al., Citation2018).

The developments in modernising the educational system with information and communication technologies and applied process thinking principles attempt to capture and model interrelated activities required to integrate digital technologies in teaching, learning and organisational practices (Fleaca, Citation2011). DT is an accelerated evolution. It is also a revolution because of its radical and structural implications for people and infrastructure, entailing new educational and business models (Gama, Citation2018). Sandhu (Citation2018, p. 295) defined digital business transformation as ‘the adaptation of business processes, procedures, and policies to harness the opportunities created by digital technologies and their impact on society, work, and future trends’.

In their systematic review, Benavides et al. (Citation2020) concluded that the social (people), organisational (process) and technological perspectives dominated the literature between 2016 and 2020. They believed it is an emerging field, and none of the DTs found in higher education propositions have been developed in a holistic dimension. They call for further research efforts to help universities understand DT and face the prevailing challenges.

Digital transformation in developing countries

We reviewed the literature to appreciate the challenges facing the digital transformation of universities in developing countries themed along Benavides et al’s. (Citation2020) proposed social (people), organisational (process) and technological perspectives.

First, the social perspective, with issues related to the motivation of the people in the system to accept the change needed and acquire the skills, knowledge and abilities to benefit from it. After the sudden shift from face-to-face to online distance learning in a private university in Egypt owing to the COVID-19 lockdown, students with learning difficulties were deprived of some support services on-campus (El Said & Mandl, Citation2021). Students and faculty members adopted social media sites during the pandemic to sustain formal academic communication in public higher education in Egypt (Sobaih et al., Citation2020). Students used social media, e.g. Facebook, WhatsApp and YouTube, to build an online community and support each other. In contrast, faculty members focused exclusively on teaching and learning, and some used free communication platforms such as Google Classroom and Zoom (Sobaih et al., Citation2020). Faculty members believed that the course design, instructor quality, assessment techniques, technology, e-learning platforms and students’ attitudes are the main challenges facing the proper implementation of online education (El Kayaly et al., Citation2020).

Lassoued et al. (Citation2020) investigated the obstacles to quality in distance learning imposed by COVID-19 across four Arab countries (Algeria, Egypt, Palestine and Iraq). They indicated that both professors and students faced self-imposed obstacles and pedagogical, technical and financial or organisational obstacles. The pandemic had pushed African universities to train academic staff on online instructional materials and tools to deliver remote learning (Muftahu, Citation2020). Pakistani students reported that lack of face-to-face interaction with instructors, response time and absence of traditional classroom socialisation were the main issues that impaired online learning (Adnan & Anwar, Citation2020).

From a global perspective, a large-scale study investigated the perception of 30,383 university students from 62 developed and developing countries, including Egypt, about the impacts of the first wave of the COVID-19 crisis on various aspects of their lives (Aristovnik et al., Citation2020). This study revealed that students were most satisfied with the support of teaching staff and their universities’ public relations. Still, deficient computer skills and a higher workload prevented them from perceiving their improved performance in the new teaching system.

Second, the process issues related to the readiness of the organisational and educational system for digital transformation. Focusing on the online admission process during COVID-19 of 16 randomly selected national and private universities in Egypt indicated that universities’ websites must be more informative, clear, accurate and updated (Abd El Halim & Beshir, Citation2020). While all professors favoured online exams, most students complained about the weak mechanisms for receiving student petitions and reviewing the perceived unfair grading of online exams (El Said & Mandl, Citation2021). Another study highlighted the importance of developing policies, programmes and education contingency measures to address future pandemics and support sustainable learning (Muftahu, Citation2020).

In Nigeria, the pandemic resulted in the pausing of international education, disruption of the academic calendar, suspension of examinations, cancellation of conferences, creation of a teaching and learning gap, shortage of staffing in the educational institutions and cuts in the budget of higher education (Jacob et al., Citation2020). In Pakistan, Mahmood (Citation2021) suggested the new remote online learning process could be enhanced by integrating feedback from students, offering flexible teaching and assessment policies, sharing resources before the class, recording online lectures and getting support from teaching assistants.

And finally, there were technology issues related to availability, capacity and cost. Most Bangali students reported a lack of technological infrastructure, high cost and low speed of the internet, financial family issues and mental pressure on the students as the main hindrances to online education (Ramij & Sultana, Citation2020). In the Philippines, researchers using qualitative phenomenological research concluded that the main challenges experienced in remote learning were poor to no internet access, financial constraints, no technological devices, and affective or emotional support, all of which contributed to the interrupted learning engagement (Alvarez, Citation2020; Schwartzman, Citation2020). In Ukraine, as an example of a developing European country, the main advantage of the online transition was time efficiency, while internet connection and technical problems were the main problems. The lecturers were partially satisfied but showed low acceptance of online education (Bakhmat et al., Citation2021).

An overview of the literature shows that the issues raised all over the developing nations addressed three perspectives. First, there were people issues related to the motivation of the participants in the system to accept the change needed and acquire the skills, knowledge and abilities to benefit from it. Second, there were the process issues related to the readiness of the organisational and educational system for digital transformation. And finally, there were issues related to technology availability, capacity and cost.

Research questions

Like many other developing nations, Egypt was unprepared for the coronavirus pandemic and its implications for higher education. The government pushed to provide the universities with the needed technology and leverage the relatively improved information and communication infrastructure. There is a long way to go for Egypt and other developing nations to be ready to provide their university students with effective and efficient distance education.

Technology is not the only hurdle, but the university management system and processes may prove to be an equally formidable challenge. The current processes were designed and practised for traditional education, with well-established policies for students and faculty physical attendance, testing and assessments, presentations and extracurricular activities. All the policies, procedures and practices must be re-engineered to accommodate the digital distance learning paradigm shift.

Nonetheless, the people in the system who have to acquire new skill sets, mindsets and behaviours are the most challenging and difficult to change. Urgency helps change management (Kotter, Citation2008), but it is not enough when the transformation is so deep, changing everything down to the profound underpinnings. The sense of insecurity is very high when the roots are shaken and jobs are at stake. And without the buy-in of the people, nothing will change.

As Martínez Guillem and Briziarelli (Citation2020, p. 368) put it, ‘future research in communication and education will have to address the potentially huge implications of this crisis, consistently monitoring the emerging discourses and practices around online and other forms of education’. Our research investigated the media and public opinion about the transformation from on-campus to online higher education from March to October 2020 during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Egypt. Three research questions can be posed from the perspectives of different stakeholders:

RQ1.

How ready were the people in the Egyptian universities to implement distance learning technologies?

RQ2.

How ready were the processes in the Egyptian universities to implement distance learning technologies?

RQ3.

How ready were the technologies in the Egyptian universities to implement distance learning?

Methodology

We used digital archival research (Kim, Citation2022) to listen to, interpret and analyse the spontaneous opinions, sentiments, expectations and experiences with the new digital learning system suddenly imposed on higher education in Egypt. The sampling frame of this study is the active real-time database of Acumen Media Intelligence (https://acumen.me/), which monitors 2500 TV and radio channels in the Middle East and another 2350 globally, 58,000 social media and news sites and 2500 publications, 60% of which are print only. The study timeframe was from 1 March to 31 October 2020.

A large random sample representing the media and public opinion was drawn over 245 days from digitised and online news articles, TV and radio programmes, and public social media posts by students, parents, academics, education experts and media professionals. Following Stryker et al. (Citation2006), we used the recall and precision test for our search string. For our recall, we used ‘distance education in Egypt’ as the broad search criterion likely to capture all relevant items in the database. A built-in artificial intelligence protocol was used to assess the relevance of the captured items, and we used a cut-off value of 95% relevance. The selected items were then classified into two categories based on their source. On the one hand were opinions of media professionals and education experts, and on the other hand, posts on social media (Facebook, Twitter and YouTube) and educational platforms by students, academics and parents.

The database has a feature that allowed us to randomly select 20% of the opinions of media professionals and education experts and 15% of the posts on social media and educational platforms in the eight months. We also monitored the repercussions of remote stakeholders in the regional and global media. This random sample produced 38,784 media items reacting to the transformation from on-campus to distance education, including digitised and online news articles, TV and radio programmes, and social media posts. reports the sample sources breakdown media-wise and geographically.

Table 1. Sample sources breakdown by media and geography.

The logic for looking globally is that more than 10 million Egyptians live abroad, with roughly seven million in Arab countries. These Egyptians remitted 31.5 billion dollars to Egypt in 2021 (Ahramonline, Citation2022), with a good percentage of them working in university and school education. Their sons and daughters return to Egypt for affordable college education. All this makes them important stakeholders to listen to. Not all the global opinions were by Egyptians, but by definition, stakeholders are all those who have an interest in or an influence on the phenomenon of the study.

The study monitored the debate for 245 days with engagement from all stakeholders. The study focused on direct stakeholders (students, academics and parents). The study also perused the media for responses from specialised groups (education experts and media professionals). The study presented the interests of different groups and stakeholders to gauge their reactions to this deliberation and their suggestions to embrace this transformation and improve its delivery. After eight months, new suggestions and arguments for or against the new system were rare; according to a random scan by Acumen professional team, it was time to stop monitoring and start analysing and writing up the findings.

Our sampling frame and selection technique observed the three main themes of archival research ethics – (1) interpretation, (2) harms and benefits, and (3) the politics of archives and politicisation of research (Sobaih et al., Citation2020). The questions of ethical interpretation of archival documents were not acute because our research was more observatory than interpretive. The only context we used was the stakeholders’ classification as academic, student and so on. We hardly interpreted meanings but used minimum paraphrasing to have proper syntax. The randomly selected texts were simple public comments and opinions published by their source. The anonymity of all the opinions reported bypassed the question of harms and benefits. In all the cases, even with media or educational experts, statements were reported anonymously, almost verbatim. Finally, there were hardly any politicised sources.

The shift from traditional higher education to distance education requires organisational and digital transformation. We used digital transformation as a lens to examine our data. We needed a theoretical foundation to guide our analysis (Lacy et al., Citation2015), and we used the IBM model for the digital transformation of organisations. Ramakrishnan and Testani (Citation2011) showed IBM how people, process and technology are the three elements of a successful organisational transformation. Their wisdom continued to inspire Del Rowe (Citation2017), who defined digital transformation as ‘the investment in people and technology to drive a business that is prepared to grow, adapt, scale, and change into the foreseeable future’.

Verina and Titko (Citation2019) defined and empirically tested the three categories based on the citation of a senior director and head of digital commerce platform transformation at Dell EMC, Sarika Puri. Puri stated that ‘people, process and technology need to be aligned’ for a digital transformation to be successful. We chose people, process and technology to be the deductive themes of our content analysis.

Results

The results of our study reflected the opinions of the different stakeholders. All the opinions and suggestions were first observed, classified and represented as key opinions without redundancy. We opted to respect the original wording of the source to restore the intended meaning, although wordsmithing may improve readability. The opinions concerning the people’s perspective will be presented first, followed by process, then technology.

Opinions about the people and distance education in the Egyptian universities

Academics asserted that many faculty members over 50 years of age are not comfortable dealing with the internet. The biggest challenge is hands-on training, especially with specialisations incompatible with distance learning techniques. There is a need to prepare professors and students for this educational style. They continued to stress the necessity of training and motivating faculty staff and the assisting body to use e-learning programmes and pursue e-learning methods instead of traditional methods.

Academics also stressed the importance of on-campus attendance for acculturation, weighing on experiences and achieving constructive interaction between students and faculty. Distance education experience during the study interruption period showed that recorded lectures are more useful than live broadcasts, especially with poor internet coverage. Academics believed that distance education was accepted and vital in undergraduate and postgraduate in some subjects but not feasible in others.

Students noted that they were not pre-trained in using educational platforms and taking online exams. The technological illiteracy of some students was the only obstacle to benefiting from distance education. Students explained that the objections to online studies or exams were out of fear of new things. Some students also reported that the family environment was distracting and did not allow much focus. But they also acknowledged that the world is changing, and that they must adapt to it.

Parents noted that distance education reduced the financial burden on the family.

Education experts asserted that university life was very different from distance education experience. Despite the advantages, they believed distance education deprived university students of the most crucial experience in their after-school life. Yet, it forced them to acquire new skills to cope with life’s various complexities.

Media professionals believed that distance education is not a fad. It began in some European and American universities in the late 1970s when professors sent different teaching materials to their students by mail. Those materials included books, tapes and videos. During the pandemic, distance learning meant that students would not be deprived of education and could continue their lessons at home or away from the university. They believe most universities were not ready to teach remotely but had to accommodate students afraid of infection.

Opinions about the process and distance education in the Egyptian universities

Academics noted that some students and faculty were apathetic about following up on lectures and practical lessons. In their opinion, universities should provide software programs accredited by the Ministry for Higher Education for interactive communication between students and faculty staff as an alternative to Zoom. They also noted they missed human contact with students and appropriate mechanisms to follow their performance and comprehension.

Academics believed there were no rigorous policies, processes and procedures for conducting and evaluating online exams. They hoped the next academic year would witness a significant development in the educational process needed and used. They believed that the method closest to implementation is hybrid or blended education, allocating part of the educational process through standard methods and the other via the internet.

Academics said that distance education defied time and space. Students could register, access and review lectures anytime, anywhere, reducing the need to construct more physical classrooms.

Students claimed that online teaching is not suited for academic programmes in which students must master practical or clinical skills. They noted that studying humanities and social sciences does not require campus attendance. They stressed that they need to benefit from the advantages of electronic platforms to develop all forms of educational services provided to students on the internet without relying on social networking.

Education experts claimed Egypt would witness a fundamental shift in the education system in the coming years. Some faculty members disagreed with distance education because they were not prepared to record and send lectures online. In contrast, other faculty scanned books and memos without explanatory notes. Still others tried to hand over online instruction to younger colleagues.

Media professionals highlighted the need for universities to have the right to choose their teaching models within a framework of quality. Universities should also choose the evaluation system for their students within the framework of declared rules without interference from other universities or the state. They insisted that students must be involved in evaluating the distance education experience. Lectures could be uploaded on CDs and safely distributed to students who cannot pay for the internet. The Egyptian E-University has made pioneering steps in distance education, and students have been accustomed to it. It is an experience that other universities can emulate.

Opinions about the technology and distance education in the Egyptian universities

Academics believed that private universities were more technologically capable of providing distance education. Professors used free Zoom and similar apps unsuitable for all courses and did not accommodate large classes, especially in overcrowded colleges.

Academics asserted that information and telecommunication infrastructure were still incapable of serving such technological transformation. Egypt was not ready to deliver online education to students in Upper Egypt and remote places where students suffer from weak information technology and telecommunication infrastructure, they claim.

Academics recommended establishing virtual laboratories for hard science faculties in line with international universities, providing internet services to students and providing professors with electronic evaluation systems and software.

Education experts believed digitalising education was part of the Egyptian state’s plan to automate all government services. This plan required preparing the information infrastructure. Technological transformation dictated directing future investments to develop information and communication infrastructures rather than constructing concrete buildings. The university buildings will become a venue for students to meet each other.

Media professionals are concerned that suddenly, universities found that the only way to teach was ‘remotely’ on online platforms. They believed universities and the Ministry of Higher Education should create educational platforms for faculty and staff to remotely record and broadcast lectures to students. Introducing the distance education process will maximise the benefit of the internet and occupy students with meaningful activities.

However, media professionals noted that some students could not pay for the internet and suffered from accessing their lessons. Moreover, the interaction between the professors and students died without interactive technologies. So media professionals proposed searching for interactive programmes that allowed students to communicate with their professors, take tests and correct them in their presence, i.e. positive remote interaction between the professor and the student.

They said:

We must bear in mind that this system is chosen by the world and is irreversible after COVID-19. The necessity of seeking non-traditional solutions based on more modern teaching and learning methods and more sophisticated information technologies is an inevitable approach if we want to make this a quality shift and improve the performance of the higher education system.

Discussion

Matching the results of Crawford et al. (Citation2020), opinions reported in this study about the main hindrances to fully fledged online learning stressed the lack of proper networks and storage capacity needed in major state universities in Egypt admitting large numbers of students. Resonating with Aristovnik et al. (Citation2020), another negative opinion reported in this study by some students is their deficient computer skills, preventing them from perceiving their improved performance in the new learning system.

Another important issue is copyright infringement, as unprepared and uninformed faculty upload digitised books and chapters without clearing the copyrights properly. Maxwell and McCain (Citation1997) discussed licensing arrangements and modification of fair use as two recommendations to balance the creators’ right to know and share.

Other insights reported in our study added and contributed to the reviewed literature. For example, academics in our sample stressed the importance of on-campus attendance for acculturation, weighing on experiences and achieving constructive interaction between students and faculty. Education experts in our sample supported that point of view. Media professionals added the need for interactive software that allows students to communicate with their professors, take tests and correct them in the professor’s presence. Some older faculty hedged the technology by handing over online instruction to more tech-savvy younger colleagues. While some students also reported that the family environment was distracting and did not allow for much focus, parents noted that distance education reduces the financial burden on the family.

The people-process-technology framework

The digital transformation (DT) research of higher education is gaining momentum as the coronavirus pandemic pushes policymakers and universities to move faster towards DT (Abad Segura et al., Citation2020; Bond et al., Citation2018; García-Peñalvo, Citation2021; Jackson, Citation2019; Mikheev et al., Citation2021; Xiao, Citation2019). Several papers discussed DT, but with a limited sample of students, professors and occasionally other stakeholders. The breadth of the data collected and the coverage of direct and indirect stakeholders, such as media professionals, encouraged us to venture further and propose a general framework for implementing DT in higher education.

This discussion builds on the previous research, our research findings, and on Ramakrishnan and Testani (Citation2011) and PWC (Citation2020) to guide the implementation of the people-process-technology framework in in the Egyptian case and highlight its components and integrated approach.

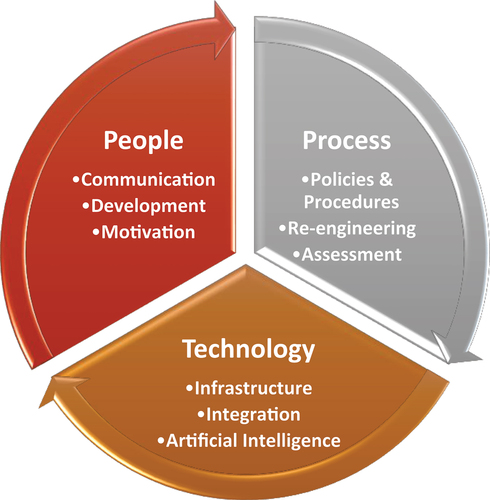

Figure 1. The people-process-technology (PPT) framework for the implementation of digital transformation of higher education (developed by the author based on the findings from PWC, Citation2020; Ramakrishnan & Testani, Citation2011).

People

Higher education is about transferring knowledge from credible scientific sources by academic professors to willing and able students. The human aspects of teaching and learning and the wider perspective of mentoring and apprenticeship are at the core of higher education (Jackson, Citation2019). Our findings suggest that digital transformation will not succeed without keen attention to communication, development and motivation of people in the system.

Communication is key to understanding and addressing people’s fears as digital transformation is implemented (Sobaih et al., Citation2020). Failing to uproot and address those fears effectively will build resistance to change that can thwart the process. Older professors resist learning new pedagogies and technologies and need coaching, motivation and support. Administrators should also be well informed of their modified roles in supporting faculty and students who often turn to them for answers. Some students must be informed about how the transformed system works and its implication for assignments, assessments and interaction (Lassoued et al., Citation2020).

Development is needed beyond the training of faculty, staff and students. Training is focused on learning skills, but it is critical to develop a new mindset in this transformation, capable of imagining a better way of doing things (Carvalho et al., Citation2022). Universities undergo several maturity levels (Marks et al., Citation2021) during the transformation as the technology gets understood, tried, implemented, integrated and leveraged. Patience is important to monitor the progress and maturity of the organisation and take effective actions to address deviations and issues promptly.

Motivation to embrace the transformation needs management reinforcement. While some students, younger professors and staff may be excited by the change, older professors and staff less versed in technology will resist the transformation and only see its dark side. Incentives need to be instigated and communicated well. Management should be creative, relevant and agile in motivating everyone in the system (Rodrigues, Citation2017). The students’ socialisation and the interactive nature of the mentoring and educational process should be enhanced, not just maintained.

Process

The stakeholders voiced many concerns about the incompatibility of the policies and process of the current system with the distance learning imperative. We believe digital transformation requires reconfiguring the university’s policies and procedures, re-engineering the managerial and educational processes, and restructuring the performance assessments for everyone.

Policies and procedures are intended to set the modus operandi of the university. In essence, the DT is a paradigm shift, requiring profound revision of the policies and procedures to reflect and require the needed change. The higher expectations of efficiency and effectiveness will not be realised by upholding the practice but by changing it. The new priorities dictate tuning the policies, tweaking the procedures and ensuring all stakeholders are informed and enthused (Rodrigues, Citation2017).

Process re-engineering is inevitable, given the digital transformation’s deep impact on every aspect of the educational and managerial processes. Technology reconfigures how knowledge is accumulated, accessed, argued, assimilated and augmented (Armistead & Meakins, Citation2002). The new learning paradigm calls for rethinking all the organisational processes to manage the student-faculty-administration engagements. Documenting and disseminating amended processes are continuous and essential (PWC, Citation2020).

Performance assessment has to stress the ability to embrace the transformation and leverage it to deliver impressive performance. The assessment should include technology and how well it serves its purpose of delivering a higher quality of education effectively and efficiently. It should include the staff and how well they support the faculty and students to cope, perform and excel within the new system (Jackson, Citation2019). New assessment criteria and methods should be developed and practised, and associated rewards should be awarded promptly and visibly (Carvalho et al., Citation2022).

Technology

Our findings noted the universities and the nation’s technology infrastructure deficiency and discussed the symptoms rather than the solutions. We believe digital transformation entails implementing information and communication technologies to deliver higher education more efficiently and effectively. This implementation requires an infrastructure of hardware, software, and networks to support implementation. DT mandates integrating the educational and managerial systems and all the information within to create a seamless operating ecosystem with appropriate accessibility for all stakeholders. Then comes an additional layer of artificial intelligence where the machines learn to add value through their analytical power and capacity to process big data for insights (PWC, Citation2020).

Infrastructure decisions involve difficult trade-offs between prudent spending and setting the stage for future expansion. The DT triggers needs and demands more automation and resources to compete in the new realm it creates. Before long, the infrastructure could not support the ambitions of the users for more utilities, versatility and sophistication (García-Morales et al., Citation2021). Modular designs and continuous upgrades are temporary solutions, but visionary planning is the ultimate answer.

Integration decisions require experience and expertise in selecting the best software configuration to automate organisational and educational operations. Trade-offs between ease of use and sophistication, and one-time and sequential implementation, are difficult (García-Morales et al., Citation2021). Training everyone and providing user support are needed to achieve a smooth deployment. Faculty, students and administrators must all appreciate, realise and enjoy the potential of DT (PWC, Citation2020).

Artificial intelligence promises to exploit the information and big data in the system to garner insights and foresight to inspire planning, leverage pedagogy, empower research and engage all stakeholders. AI is not just another utility in the system. It is the gate to a new educational realm where machines and human minds play in concord to contribute to science, create intelligence and shape the future (PWC, Citation2020).

Conclusion

Studying a phenomenon such as digital transformation in higher education, we focused on the challenges facing the implementation of DT. Our purpose was to garner all the signals from the literature and the media to develop profound insights into the people, process and technology framework for the application and long-term operation of digital transformation of higher education in developing countries.

The stakeholders’ opinions and the literature review converged on the people-process-technology perspectives as a guiding framework to guide the implementation of digital transformation in universities. Our discussion showed that our literature review and findings are aligned with Ramakrishnan and Testani’s (Citation2011) PPT framework. PWC (Citation2020) underscores some key factors in the framework that must be contemplated in digital transformations.

Limitations and future research

We focused on the stakeholders’ feedback in the literature review or our research design. There is mounting literature about the application of digital transformation in higher education. We cited some key articles but did not include those focused only on the phenomenon’s engineering, information technology and connectivity aspects.

We also focused on empirical research about Egypt and developing countries in Africa, Asia and Europe. There are many other American and European studies, but they did not have the same challenges or low level of readiness for the transformation in developing countries.

Another limitation is the vast amount of media items identified by the keyword search over eight months on such a hot topic. We followed Stryker et al’s. (Citation2006) recommendations, took a random sample using the AI capabilities of the Acumen database and applied the recall and precision method. We had to glean the main message from tens of thousands of media items; then we had to further merge these messages without allowing our opinion to leak in. This process cannot be perfect, but the purpose was to get a qualitative understanding of the phenomenon rather than precisely measuring any variable. We approached the data with a brainstorming mindset, respecting all messages without weighing their logic, prominence, recurrence or source credibility.

We believe our framework will be the foundation for many studies in digital learning transformation, operations, human resources and information technology. We have identified many issues under the three themes of people, process and technology worthy of operationalisation and measurement. The phenomenon is still young and will continue to take shape for decades. The technology is moving fast, and the competition between the universities for students, donors and faculty will accelerate the process further. University graduates’ employers are transforming their businesses to survive or thrive.

The business world is the ultimate client for university graduates, offering jobs and pay. The new economy demands better informed and trained graduates, more intellectual, resourceful, motivated, and adept at applying technology. The digital transformation of higher education is a prerequisite to preparing students for a future that isn’t what it used to be (Riding & Graves, Citation1937).

Acknowledgments

Acumen Media Intelligence contributed access to their archives and AI capabilities in addition to the time and dedication of their expert staff to support this research. Without their support, this research would not have been possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ahmed Taher

Ahmed Taher has taught marketing at The University of Georgia, Offenburg University in Germany, and The American University in Cairo since 1991. He holds a BSc in Civil Engineering, an MBA from the Ohio State University and a PhD from the University of Georgia. He won the Excellence in Teaching Award from the University of Georgia in 1995 and the AUC in 2005–06. Dr Taher has published about 25 articles and five books.

References

- Abad Segura, E., González-Zamar, M. D., Infante-Moro, J. C., & Ruipérez García, G. (2020). Sustainable management of digital transformation in higher education: Global research trends. Sustainability, 12(5), 2107. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052107

- Abd El Halim, H., & Beshir, S. (2020). Assessing the experience of universities’ online admission in Egypt: An experiment conducted during the COVID-19. Journal International Journal of African and Asian Studies (JAAS), 69(43–56). https://doi.org/10.7176/JAAS/69-06

- Adnan, M., & Anwar, K. (2020). Online learning amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Students’ perspectives. Journal of Pedagogical Sociology and Psychology, 2(1), 45–51. https://doi.org/10.33902/JPSP.2020261309

- Ahramonline. (2022, March 14). https://english.ahram.org.eg/News/462825.aspx.

- Alvarez, A., Jr. (2020). The phenomenon of learning at a distance through emergency remote teaching amidst the pandemic crisis. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), 144–153. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3881529

- Aristovnik, A., Keržič, D., Ravšelj, D., Tomaževič, N., & Umek, L. (2020). Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the life of higher education students: A global perspective. Sustainability, 12(20), 8438. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208438

- Armistead, C., & Meakins, M. (2002). A framework for practicing knowledge management. Long Range Planning, 35(1), 49–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-6301(02)00017-1

- Bakhmat, L., Babakina, O., & Belmaz, Y. (2021, March 1). Assessing online education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey of lecturers in Ukraine. Journal of Physics, 1840(1), 012050. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1840/1/012050

- Benavides, L. M. C., Tamayo Arias, J. A., Arango Serna, M. D., Branch Bedoya, J. W., & Burgos, D. (2020). Digital transformation in higher education institutions: A systematic literature review. Sensors, 20(11), 3291. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20113291

- Bond, M., Marín, V. I., Dolch, C., Bedenlier, S., & Zawacki-Richter, O. (2018). Digital transformation in German higher education: Student and teacher perceptions and usage of digital media. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 15(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-018-0130-1

- Carvalho, A., Alves, H., & Leitão, J. (2022). What research tells us about leadership styles, digital transformation and performance in state higher education? International Journal of Educational Management, 36(2), 218–232. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-11-2020-0514

- Crawford, J., Butler-Henderson, K., Rudolph, J., Malkawi, B., Glowatz, M., Burton, R., Magni, P., & Lam, S. (2020). COVID-19: 20 countries’ higher education intra-period digital pedagogy responses. Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching, 3(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.37074/jalt.2020.3.1.7

- Del Rowe, S. (2017). Digital transformation needs to happen: The clock is ticking for companies that have been unwilling to embrace change. CRM Magazine, 21(10). https://www.destinationcrm.com/Articles/Editorial/Magazine-Features/Digital-Transformation-Needs-to-Happen-Now-120789.aspx

- El Kayaly, D., Hazem, N., & Fahim, I. (2020). Online teaching at Egyptian private universities during COVID 19: Lessons Learned. In 2020 Sixth International Conference on e-learning (econf), Cairo, Egypt (pp. 22–27). IEEE. ID: covidwho-1196277.

- El Said, G. R., & Mandl, T. (2021). How did the COVID-19 pandemic affect higher education learning experience? An empirical investigation of learners’ academic performance at a university in a developing country. Advances in Human-Computer Interaction, 2021, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6649524

- Faria, J. A., & Nóvoa, H. (2020). Digital transformation at the university of Porto. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Exploring Services Science, 5–7 February. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56925-3_24

- Fleaca, E. (2011). Embedding digital teaching and learning practices in the modernization of higher education institutions. In Proceedings of the SGEM2017 International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference: SGEM, 20–25 June. https://doi.org/10.5593/sgem2017/54/S22.006

- Gama, J. A. P. (2018). Intelligent educational dual architecture for university digital transformation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), 3–6 October, pp. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1109/FIE.2018.8658844

- García-Morales, V. J., Garrido-Moreno, A., & Martín-Rojas, R. (2021). The transformation of higher education after the COVID disruption: Emerging challenges in an online learning scenario. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 616059. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.616059

- García-Peñalvo, F. J. (2021). Avoiding the dark side of digital transformation in teaching. An institutional reference framework for e-learning in higher education. Sustainability, 13(4), 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042023

- Jackson, N. C. (2019). Managing for competency with innovation change in higher education: Examining the pitfalls and pivots of digital transformation. Business Horizons, 62(6), 761–772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2019.08.002

- Jacob, O. N., Abigeal, I., & Lydia, A. E. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on the higher institutions development in Nigeria. Electronic Research Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 2(2), 126–135. http://www.eresearchjournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/0.-Impact-of-COVID.pdf

- Kaminskyi, O. Y., Yereshko, J., & Kyrychenko, S. O. (2018). Digital transformation of university education in Ukraine: Trajectories of development in the conditions of new technological and economic order. Information Technologies and Learning Tools, 64(2), 128–137. https://doi.org/10.33407/itlt.v64i2.2083

- Kim, D. S. (2022). Taming abundance: Doing digital archival research. PS: Political Science & Politics, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/S104909652100192X

- Kotter, J. P. (2008). A sense of urgency. Harvard Business Press.

- Lacy, S., Watson, B. R., Riffe, D., & Lovejoy, J. (2015). Issues and best practices in content analysis. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 92(4), 791–811. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699015607338

- Lassoued, Z., Alhendawi, M., & Bashitialshaaer, R. (2020). An exploratory study of the obstacles for achieving quality in distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education Sciences, 10(9), 232. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10090232

- Mahmood, S. (2021). Instructional strategies for online teaching in COVID-19 pandemic. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 3(1), 199–203. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.218

- Maltese, V. (2018). Digital transformation challenges for universities: Ensuring information consistency across digital services. Cataloging & Classification Quarterly, 56(7), 592–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639374.2018.1504847

- Marks, A., Al-Ali, M., Atassi, R., Elkishk, A. A., & Rezgui, Y. (2021). Digital transformation in higher education: Maturity and challenges post COVID-19. In International Conference on Information Technology & Systems (pp. 53–70). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68285-9_6

- Marquez, J., Villanueva, J., Solarte, Z., & Garcia, A. (2013). Advances in information systems and technologies. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, 206(115), 201–212.

- Martínez Guillem, S., & Briziarelli, M. (2020). Against gig academia: Connectivity, disem-bodiment, and struggle in online education. Communication Education, 69(3), 356–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2020.1769848

- Maxwell, L., & McCain, T. A. (1997). Gateway or gatekeeper: The implications of copyright and digitalization on education. Communication Education, 46(3), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634529709379087

- Mikheev, A., Serkina, Y., & Vasyaev, A. (2021). Current trends in the digital transformation of higher education institutions in Russia. Education and Information Technologies, 26(4), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10467-6

- Muftahu, M. (2020). Higher education and COVID-19 pandemic: Matters arising and the challenges of sustaining academic programs in developing African universities. International Journal of Educational Research Review, 5(4), 417–423. https://doi.org/10.24331/ijere.776470

- PWC. (2020). Transforming higher education – The digital university. PwC. https://www.pwc.co.uk/government-public-sector/education/assets/transforming-higher-education.pdf

- Ramakrishnan, S., & Testani, M. (2011). People, process, technology three elements for a successful organizational transformation. IBM path forward to business transformation. IBM Centre for Learning and Development, 1–21. www.iise.org/Details.aspx?id=24456

- Ramij, M., & Sultana, A. (2020). Preparedness of online classes in developing countries amid COVID-19 outbreak: A perspective from Bangladesh. Afin. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3638718

- Riding, L., & Graves, R. (1937). From a private correspondence on reality. Epilogue, 3(Spring), 107–130.

- Rodrigues, L. S. (2017). Challenges of digital transformation in higher education institutions: A brief discussion. In Proceedings of the 30th International Business Information Management Association Conference, IBIMA 2017—Vision 2020: Sustainable Economic Development, Innovation Management, and Global Growth, 8–9 November.

- Sandhu, G. (2018). The role of academic libraries in the digital transformation of the universities. In Proceedings of the 2018 5th International Symposium on Emerging Trends and Technologies in Libraries and Information Services (ETTLIS), 21–23 February, pp. 292–296. https://doi.org/10.1109/ETTLIS.2018.8485258

- Schwartzman, R. (2020). Performing pandemic pedagogy. Communication Education, 69(4), 502–517. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2020.1804602

- Sobaih, A. E. E., Hasanein, A. M., & Abu Elnasr, A. E. (2020). Responses to COVID-19 in higher education: Social media usage for sustaining formal academic communication in developing countries. Sustainability, 12(16), 6520. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12166520

- Stryker, J. E., Wray, R. J., Hornik, R. C., & Yanovitzky, I. (2006). Validation of database search terms for content analysis: The case of cancer news coverage. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 83(2), 413–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900608300212

- Verina, N., & Titko, J. (2019, May). Digital transformation: Conceptual framework. In Proc. of the Int. Scientific Conference ‘Contemporary Issues in Business, Management and Economics Engineering’2019’, Vilnius, Lithuania (pp. 9–10). https://doi.org/10.3846/cibmee.2019.073

- Xiao, J. (2019). Digital transformation in higher education: Critiquing the five-year development plans (2016–2020) of 75 Chinese universities. Distance Education, 40(4), 515–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2019.1680272