ABSTRACT

The Biblical trope of a ‘land of milk and honey, abounding in corn, wine and oil and all material goods’ is found in medieval works describing the Holy Land and is common in crusading rhetoric. Do these statements, idyllic as they are, reflect the fact that agricultural production rates in the Levant were higher than those in contemporary Europe – and more specifically France, the original homeland of the majority of the European settlers? The article aims to cast a fresh look upon the detailed thirteenth-century account by the Venetian Marsilio Zorzi, to estimate whether crop yields achieved by local peasants were indeed higher than those attained in France, and comparable with other Mediterranean regions, around the same time. Rereading and analysing this account, together with other textual sources, as well as archaeological and palaeoclimatic data, reveals not only that thirteenth-century yields were just on a par with those attained in France, and lower compared with other Mediterranean regions around the same time, but also lower than in preceding centuries in the Levant. This was connected to larger eco-climatic changes in the region on the one hand, and to cultural and institutional factors on the other. Taken together, this paper’s analysis offers new insights into the motives that guided European immigrants settling in the Levant, the nature of their society and economy, and wider environmental changes in that region.

Magistro, collegae amicoque meo B.Z. Kedar / למורי, עמיתי וידידי ב"ז קדר

The present study exemplifies how a single (but quite unique) source conceals some vital hints and potentially provides answers to several big questions and long-standing debates related to the Frankish settlement in the Levant in particular, and to the economic history of the Middle East in general. The source in question is an entry on the state of a village of Betheron (in the Tyre hinterland) reported by Marsilio Zorzi, a Venetian bailo stationed at Acre between spring 1242 and spring 1244, and forming a part of his report on landed estates of the commune in the Tyre region. On the surface, the Betheron entry states, among other things, the quantities of sown and harvested crops. A deeper analysis, however, provides a unique glimpse into agricultural practices, structures and fortunes in the Frankish Levant. In particular, it sheds light onto the following ‘big’ questions, each of which, in turn, is linked to some ongoing debates:

How productive was agriculture in the Frankish Levant (c. 1099–1291)?

Was it equally or less productive than in the previous centuries?

What prompted European individuals to settle in the Frankish Levant?

How ‘colonial’ was Frankish settlement and how ‘capitalist’ was their agriculture (and by extension, their economy)?

The first question has been hardly touched upon by scholars. One exception is Joshua Prawer, who concluded (first in a 1952 article and then in his 1980 Crusader Institutions), on the basis of Zorzi’s report, that thirteenth-century grain yields in Syria-Palestine were approximately as in the Roman period, but lower than in the early twentieth century, and standing on a par with those in thirteenth-century England.Footnote1 The second question, deriving from the first one, is linked to a debate about the long-term economic decline of the Middle East – particularly, in the context of ‘Great Divergence’ between the ‘West’ and the ‘rest’. For some economic historians, such as Timur Kuran and Jared Rubin, it was not until the early modern period that the Middle East would start lagging behind western Europe – because of cultural and institutional factors.Footnote2 The agricultural foundations of the economic crisis and decline of the Middle East in the Mamluk period have been analysed by Elyahu Ashtor in 1977 and 1981.Footnote3 More recently, Ronnie Ellenblum delved into the environmental foundations of the crisis in his 2012 Collapse of the Eastern Mediterranean, where he identified a period of cold and dry climate dominating between c. 950 and 1072.Footnote4 Ellenblum’s arguments have not been accepted favourably by all.Footnote5 By contrast, the question of fitting the Frankish/Ayyubid period, an intermediate era between the Fatimid and Mamluk periods, into this context of long-term agricultural and economic decline has not been explored.

The fact that the Frankish/Ayyubid period has been left out is a great impediment to our understanding of the economic motives of European migrants, primarily from France, to come and settle in the Levant in the course of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. If there were indeed signs of an economic crisis and decline before the Frankish dominance, as suggested by Ellenblum, then how can we explain their migration and settlement? The old idea that Frankish immigrants to the Levant during the crusading era were invariably settling in towns and castles, perpetuated, most famously, by Joshua Prawer,Footnote6 has been long dismissed, on the basis of both textual and archaeological evidence, by Ronnie Ellenblum.Footnote7 Much less clear are economic motives of the same ‘Franks’ for immigration to and settlement in rural Levant. Given the agricultural nature of rural economies, it is tempting to think right away about local opportunities, not available back home: high grain yields, rich vineyards and exotic sugar cane plantations. Does European rural settlement reflect a temporary agricultural improvement during Frankish dominance? If, however, the situation was not better than in the previous century or two, studied by Ellenblum, then what practical factors would attract them to the Holy Land? Certainly, a religious sentiment and chivalric values guiding crusading leaders and nobility during the large-scale military campaigns, like the First Crusade, Footnote8 can hardly explain the motives of a Frankish burgess migrating in relatively peaceful times around, say, 1170 or 1210.

The latter question is strongly connected to the fourth question related to the nature of Frankish society in twelfth- and thirteenth-century Levant. Beginning with Emmanuel Guillaume Rey, Gaston Dodu, Claude Reignier Conder, Louis Madelin, René Grousset, Claude Cahen, and Joshua Prawer, the idea that Frankish settlers were the earliest European colonialists dominated for a long time in historiography and is still a commonly held view in popular and non-specialist perceptions.Footnote9 This ‘colonialist’ view has been ever since challenged, with some historians distancing themselves from it.Footnote10 One aspect left out in this debate is the nature of economic behaviour, decisions and strategies undertaken by Frankish migrants in the course of their settlement in the Levant. To appreciate that, it is important to consider these against other, later examples of European colonial economies in Asia and Africa. Such comparative analysis can reveal how ‘colonial’ was Frankish society and how ‘capitalist’ was their economy. Hopefully, these insights into these four big questions will lay some groundwork for future research.

Christian and Islamicate depictions of agricultural productivity in Syria-Palestine

Before delving into Zorzi’s report, it is instructive to look into textual depictions of agricultural productivity in Syria and Palestine by both West Christian and Islamicate authors. Perhaps no other Christian text reflects the idyllic perception of Holy Land, based on a dichotomy between poverty at home and riches beyond the sea, as clearly as the Clermont speech (27 November 1095) by Pope Urban II, carried amidst a bad crop failure and harsh subsistence crisis all over western and central Europe. According to Robert the Monk’s version of the speech, Urban allegedly depicted the Holy Land as a land which ‘floweth with milk and honey … fruitful above others, like another paradise of delight’ – in sharp contrast with France, whose land was ‘too narrow for [its] large population’ and having ‘scarcely food enough for its cultivators’.Footnote11 Given that this dichotomic trope is found only in Robert’s version of Urban’s speech, we cannot be certain if the pope said anything similar, or if those words were merely put into his mouth by the chronicler. We may nevertheless assume that they may reflect the expectations of departing crusaders. Importantly, these expectations were not only spiritual ones, imbued in Biblical and quasi-Messianic motifs, but also quite earthly, reflecting the burden that local French landlords and tenants had to bear as a result of a disastrous crop failure of 1095.Footnote12

Writing of the Frankish East, several authors provide some fanciful details on extraordinary high yields produced by local land. Thus, in his Chronicon, William of Tyre alleged that the region around Ascalon, lying uncultivated for fifty years, would produce a sixty-fold yield in the aftermath of the city’s conquest by the Franks in 1153.Footnote13 Nothing short of another Biblical trope, based on Matthew 13:8 (the Parable of the Sower), such a figure cannot be taken seriously given that even the most productive agricultural world regions, such as the Yangtze delta, parts of India, Sicily and Egypt, were yielding – in average years – about four times less that figure.Footnote14 Abbot Daniil the Pilgrim of Kiev, visiting the Holy Land in 1104–6, went even further, stating that farmers in the Jerusalem region would harvest 90 or 100 measures of wheat and barley for each sown measure.Footnote15 Elsewhere, Daniil commented on extraordinary soil fertility in the Hebron and Samaria regions.Footnote16 Ironically, those regions mentioned by Daniil must have, in reality, been among the most infertile ones in Frankish Palestine.Footnote17

This idea of high land fertility is echoed, albeit in much less fanciful manner, in other European pilgrims’ accounts. Thus, in his Libellus de locis sanctis (c. 1172), Dietrich (or, Theodericus) spoke about an abundance of grain and garden produce in the Judaean valley, and about the fertile soil of Samaria.Footnote18 Similarly, Wilbrand of Oldenburg, visiting Jerusalem in 1211–2, noted that local hills produced much wine, oil and wheat.Footnote19 Six or so years later, Thietmar, another German pilgrim, related that wheat grew in abundance on the plains of Moab.Footnote20 Burchard of Mount Sion’s Descriptio Terrae Sanctae, based on his travels across the Holy Land in 1283–5, describes the soil of the Holy Land as outstanding compared to all other lands, despite some arguments to the contrary, for it was very fertile in wheat, which grew virtually without human labour.Footnote21 That soil around Jerusalem was the best and most plentiful was claimed even in an Old Icelandic Biblical compilation known as Stjórn (c. 1300), relying, in turn, on earlier accounts of Icelandic pilgrims and European continental sources.Footnote22 The Biblical trope of a ‘land of milk and honey, abounding in corn, wine and oil and all material goods’ is found in several pilgrims’ works, including a travelogue of Philip of Savona, OFM (1285–9).Footnote23 Most relevantly for this study, William of Tyre spoke about a highly fertile terrain in and around Tyre, blessed with optimal soil, producing plentiful foodstuffs for its inhabitants.Footnote24

Intriguingly, these idyllic statements are echoed by Islamicate authors, particularly geographers, both before and during the Frankish period. Thus, Ibn al-Faqīh al-Hamadhānī (fl. 902), stated in a generalised manner that Palestine is both vast and rich land.Footnote25 In a much more detailed manner, al-Muqaddasī (945/6–91), outlining agricultural peculiarities of each region in Syria-Palestine, suggested that virtually all regions there were fertile and abundant in arable fields, olive trees, orchards and vineyards. Specifically, he painted Jerusalem as a blessed land of milk and honey.Footnote26 Similarly, Nāsir Khusraw, travelling in the region in 1047, noted the fruitfulness of different parts of the region, and indicated that the Jerusalem region was abundant in all different crops, despite being unirrigated and upland.Footnote27 The agricultural fruitfulness of Syria and Palestine is likewise commented upon in the anonymous Ḥudūd al-ʿĀlam (c. 982–3),Footnote28 as well as by al-Iṣṭakhrī (d. c. 957),Footnote29 al- Zayyāt (c. 960–1050),Footnote30 and al-Idrīsī (1100–65/6)Footnote31 Importantly, in Ṣūrat al-’Arḍh (977), Ibn Ḥawqal, while praising all districts in the region, stated that Palestine is the most fertile region of Syria, while Jerusalem is the most fertile region in Palestine, despite its topography.Footnote32 Ibn Ḥawqal’s ideas are repeated, at a much later period, by Abū al-Fidāʾ (1273–1331).Footnote33 Ibn al-ʿArabī (1076–1148), living in Jerusalem in 1093–6 (that is, on the eve of the crusader conquest), juxtaposed fruitful Palestine with his impoverished native al-Andalus.Footnote34 In other words, the perception of Syria-Palestine as a land of milk and honey and of Jerusalem (the holy city of all three Abrahamic religions) as an exceptionally fertile region was indeed shared by both Christian and Islamic authors.

Do these statements voiced by both Christian and Islamic writers, idyllic and exaggerated as they are, reflect the fact that agricultural production rates in the Levant were higher than those in contemporary Europe – and more specifically, France, the original homeland of the majority of Frankish settlers? To my best knowledge, the only hint of the level of agricultural productivity in Frankish Syria-Palestine is found in a report of Marsilio Zorzi,Footnote35 a Venetian bailo for the Levant stationed at Acre between spring 1242 and spring 1244.Footnote36 During his tenure, Zorzi produced a detailed account that recorded, in addition to Levantine properties of the Venetian commune, also adjacent estates belonging to other local lords.Footnote37 In total, Zorzi reported the state of affairs in 13 villages (casali), all in the Tyre region, recording, in a fairly meticulous detail, the names of local household heads, the size of their holdings, crops produced and rents owed. Of all 13 villages, however, the only quantifiable information on local crop yields derives from a single entry on the village (casale) Betheron (identified by Maurice Chéhab with Ḍahr Baitaruh = ضهر بيتروه, 33°14’11.91"N, 35°22’58.01"E; 20 km south-east of Tyre),Footnote38 held jointly by the commune and the archbishopric of Tyre.Footnote39

Zorzi’s report has been long known to historians, who used it primarily in conjunction with their studies of thirteenth-century Levantine demography.Footnote40 The only historian to have utilised its potential to shed light on agricultural production levels was Joshua Prawer.Footnote41 Unfortunately, Prawer’s calculations suffer from several faults, rendering them both inaccurate and unreliable. The present article aims to cast a fresh look upon Zorzi’s entry on Betheron to estimate crop yields achieved by local fallāḥīn in the thirteenth century and see if these were indeed higher than those attained in France and comparable with other Mediterranean regions, around the same time. Rereading and analysing this entry may, in turn, have implications for our understanding of motives that guided European immigrants settling in Frankish-controlled territories of the Levant and the very nature of their society.

Measuring arable productivity

Before delving into Zorzi’s report, it is important to note that there are several measures indicating land productivity and its change over time, utilised by economic historians – all expressed as crop yields. Arguably the single most basic measurement of agricultural performance is seed-ratio yields, that is, the number of grains harvested for each grain sown. Thus, if in a given year a wheat field produced, say, 400 quarters from 100 quarters sown in the previous year, the seed-ratio yield would be 4:1 (400 quarters harvested/100 quarters sown).

Although seed-ratio yields have been often used by economic historians as an indicator of agricultural performance, they provide a rather imperfect and abstract measure. Thus, they ignore some important variables, such as seeding densities, labour intensity rates and, most importantly, calorific values. To appreciate the real output levels, it is essential to deploy more direct measurements of agricultural productivity. One method, often used by economic historians, is per land-unit yields, which establish, on the most fundamental level, how much was produced (in weight or volume) on one unit of sown arable land (most commonly, bushels per acre or hectolitres per hectare).Footnote42

Although per-land-unit yields provide a good indication of food volume produced on each land unit, they still cannot be considered as a real measure of food production, owing to considerable variances in food energy value across different crops. Thus, one bushel of wheat yields about 3.6 times more calories than the same volume of legumes and about 1.2 times more than barley.Footnote43 Therefore, to get a much better idea of how much food is really produced on one land unit, I suggest using an alternative measure: calorific yields, calculated by converting the volume of each crop grown on one sown land unit into its approximate energy equivalents (in this instance: bushels harvested from one acre into kcals). Unlike other measures, calorific yields take into account calorific differences provided by different crops, and hence, show how much ready-to-be-processed food was produced on the same acre.

Seedcorn rates is yet another measure of agricultural performance. In essence, it is a relative proportion of harvest invested as seedcorn in the sowing season following the harvest season. For instance, if a peasant, having harvested 100 bushels of wheat, allocated 10 bushels of the same harvest for seeding, seedcorn rates would be 10 per cent. If, however, the same peasant invested 30 bushels from the same harvest of 100 bushels, then seeding rates would be 30 per cent. One advantage of seedcorn rates is that it reflects living standards and wealth of rural producers. In any pre-Industrial society, seed was an important form of capital investment, on a par with land, money, and labour. On the most basic level, the lower the seedcorn rates were, the more marketable surplus would remain at a peasant family’s disposal. Conversely, high seedcorn rates would endow it with little or no surplus.

On a deeper level, seedcorn rates reveal the potential of long-term economic performance across regions. The very existence of marketable surpluses on a household level hints that agricultural produce exceeded the calorific requirements of local producers, and that food supply could be distributed much beyond the local level. This would lead to a foundation and proliferation of food markets that would, in theory, release certain individuals and communities from the need to work the land, and allow them to specialise in and perform non-agricultural tasks. This would facilitate urbanisation and the division of labour (both between the town and the countryside and within the same towns) that it entails. This, in turn, would encourage the growth of complex and sophisticated economic systems, gearing towards developed business institutions, international trade, monopolistic competition, and proto-industrialisation.

Finally, we should also account for seeding density rates, as another indicator of agricultural performance. This measure is positively correlated with seedcorn rates and negatively correlated with crop yields, be they expressed as seed-ratio yields, or per-land-unit yields, or as calorific yields. Thus, crop producers from regions achieving high yields and investing small proportions of annual harvests in seedcorn would, as a rule of thumb, sow each land unit thinly, and hence practice labour-extensive sowing. By contrast, peasants from regions with lower crop yields and higher seedcorn rates would, invariably, sow densely, whereby practicing labour-intense sowing.

Arable productivity levels in the Tyre region, c. 1242

Where does thirteenth-century Tyre region stand, as far as the agricultural productivity indicators above are concerned? Our point of departure would be Zorzi’s statement that in Betheron (1) local tenants of the Venetian holding (rustici nostri) would seed annually 12 modii of wheat in an arable field and three modii of legumes on the fallow (garitus/terra macatica/terra frata);Footnote44 and (2) seeding rates stood, invariably across all villages, at 9 modii per carruca for grains (wheat and barley) and at one modius per carruca for legumes.Footnote45 In all instances, the modius unit in question was the kingdom of Jerusalem modius (modius regalis), rather than the Venetian modius.Footnote46

First, we need to determine a volume equivalent of one modius and an area equivalent of one carruca. In his Crusader Institutions, Joshua Prawer assumed incorrectly, following Rey, one modius to be 176 litres and one carruca to contain 35 hectares (∼86 acres).Footnote47 In reality, however, one crusader modius, as commonly used in Acre, was equal to 166.6 litres (or two Venetian stai), as indicated in two commercial manuals from Venice (an anonymous manual from c. 1270 and the so-called Zibaldone da Canal from the early fourteenth century).Footnote48 The equation of carruca with 35 hectares is an even bigger stretch: as Ronnie Ellenblum has shown, on the basis of archaeological evidence, the crusading carruca appears to be, more or less, on a par with its European counterpart, whose size would have been in the area of 3–4 hectares (∼7.5–10 acres).Footnote49

(1) Seeding density rates in thirteenth-century Tyre region

Any estimates of arable productivity should begin with the question of seeding density rates. Converting 12 modii of wheat annually sown by local tenants of Betheron into their volume equivalent, we arrive at almost 2,000 litres (at 166.6 litres per modius), equalling 20 hectolitres, or 55 bushels (one hectolitre = 2.75 bushels). If seeding rates stood at 9 modii per carruca for grains, then the total area of a wheat field within the Venetian part of the village, sown with 12 modii, would have been 1.3 carruce, equalling 4 or 5.3 hectares (= 9.9 or 13.2 acres), assuming one carruca equalling 3 or 4 hectares, as suggested by Ellenblum. Sowing 55 bushels on this area renders seeding rates of either 5.6 bushels per acre (55 bushels/9.9 acres) or 4.2 bushels per acre (55 bushels/13.2 acres). The latter estimate is undoubtedly closer to reality than the former: 5.6 bushels per acre appears to be an excessively high figure, not only for a comparatively fertile region around Tyre, but even to ‘Fringe’ Temperate North-European Zone (Scandinavia and Scotland), where seeding densities appear to have been among the highest and crop yields among the lowest in the world (ranging from 4 to 5 bushels per acre).Footnote50 Indeed, 4.2 bushels per acre would have been in line with seeding rates of 4.6 bushels per acre (= 4 hectolitres per hectare) in sixteenth-century Syria, as indicated in Ottoman tahrir defterleri.Footnote51 It should be noted that these figures are higher compared to seeding rates of about 3 bushels per acre and 2 bushels per acre achieved by Syrian fallāḥīn around, respectively, 1800 and 1900, reflecting a piecemeal shift to more extensive farming, owing to various agricultural improvements (primarily, the introduction of new crops and fertilising methods, as well as a switch from a two- to three-field system).Footnote52

Although seeding rates in the Tyre region appear to be excessively dense compared to both late-medieval Europe and late Ottoman Syria, they appear to be actually somewhat thinner than elsewhere in the Levant. In the Beirut region, local fallāḥīn were sowing each carruca with four ghiraras, equalling about 5 bushels per acre.Footnote53 In a 1257 charter, John of Ibelin, count of Jaffa and Ascalon, stated he would give the Hospitallers 600 carruce of land in the Ascalon region, if reconquered, with each carruca to be sown with four guarelles (equal to 12 modii), that it, approximately 5.6 bushels of grain per acre.Footnote54 Those regional variances may have been linked to regional population densities and, as argued below, to varying land quality and productivity. Intriguingly, this gap in seeding densities between Syria and Palestine continued well into the early twentieth century: at that point, Syrian fallāḥīn would sow at the rate of two bushels an acre, compared with 2.75 bushels in Palestine (that is, 1.38 times thinner).Footnote55

Conversely, legumes appear to have been seeded much more extensively, on a fallow portion of the village, if we follow Zorzi. Converting three modii of wheat annually sown by local tenants of Betheron into their volume equivalent, we arrive at 500 litres (at 166.6 litres per modius), equalling 5 hectolitres, or 13.7 bushels (with one hectolitre = 2.75 bushels). If seeding rates stood at just one modius per carruca for legumes, then the total area of a fallow field within the Venetian part of the village, sown with three modii, would have been about three carruce, equalling 9 or 12 hectares (= 22.2 or 29.7 acres), assuming one carruca equalling 3 or 4 hectares, as suggested by Ellenblum. Sowing 13.7 bushels per this area renders seeding rates of either 0.62 bushels per acre (13.7 bushels/22.2 acres) or 0.46 bushels per acre (13.7 bushels/29.7 acres). Those thin seeding rates of legumes reflect their high yields (see below) compared to wheat. Interestingly, during the Ottoman era, one witnesses a piecemeal intensification of legume seeding densities in Syria and Palestine – reaching about 3 bushels per acre towards the end of the nineteenth century.Footnote56 This development mirrors inversely the situation within the grain field, where, conversely, seeding densities would decrease, over time. There is no doubt that the two processes were inter-connected, with the intensification of legume cultivation contributing to the increase of soil nutrient via nitrogen restoring and resulting in higher grain yields and, hence, lower seeding densities within the latter sector.

(2) Seed ratio yields in thirteenth-century Frankish Tyre region

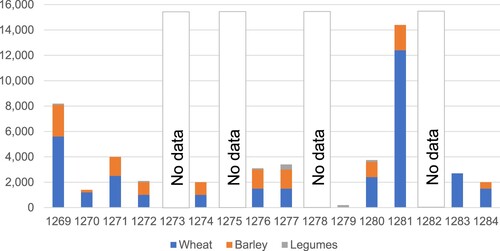

Having estimated seeding rates of grains, we may now attempt to establish approximate per land-unit yields, expressed, for the sake of convenience, in bushels per acre. Fortunately, Zorzi reported that out of the previous year’s wheat harvest (presumably early summer 1241 or 1242),Footnote57 the commune collected a third part of the wheat and legume (and legume-grain mixture) harvest, amounting to around 20 modii of wheat and 10 modii of wheat and legume and legume-grain mixture (de frumento in tercia parte iusta XX modia, et de leguminibus et alio blado iusta X modia). This implies a total harvest of about 60 modii of wheat and 30 modii of legumes and legume-grain mixture, with the remaining 40 modii and 20 modii being retained by local tenants.Footnote58 Hence, the harvest of about 60 modii in relation to 12 modii sown in the previous year implies a gross seed ratio yield of 5:1 (or a net yield of 4:1, assuming 48 modii of disposable harvest, net of 12 modii of seedcorn) for wheat. For legumes and legume-grain mixtures, the figures would be higher, standing at about 10:1 as a gross yield or 9:1 as a net yield (30 modii of the total harvest or 27 modii of a disposable harvest received from three modii sown) (see ). Our assumption here is that the 1241/2 harvest was an ‘average’ one for its times, rather than ‘good’ or ‘poor’. There is no evidence of any environmental or climatic crises in those years, leading to a subsistence crisis, let alone famine.Footnote59 However, as shown below, the period c. 1180–1260 is characterised by dry conditions, with the 1230s–50s particularly standing out (see ).

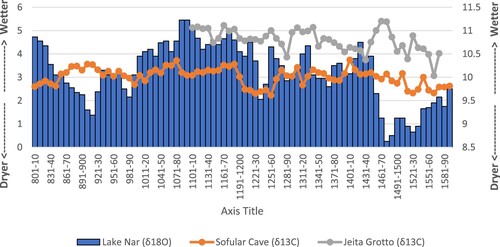

Figure 1. Precipitation levels, reflected in carbonate and oxygen data isotopes from Lake Nar (Turkey), Sofur Cave (Turkey) and Jeita Grotto (Lebanon).

Note: Left axis = Lake Nar values (0–6), Right axis = Sofular Cave and Jeita Grotto values (8.5–11.5).

Source: Jonathan R. Dean et al., ‘Eastern Mediterranean Hydroclimate over the Late Glacial and Holocene, Reconstructed from the Sediments of Nar Lake, Central Turkey, Using Stable Isotopes and Carbonate Mineralogy’, Quaternary Science Review 124 (2015): 162–74; Dominik Fleitmann et al., ‘Sofular Cave, Turkey 50KYr Stable Isotope Data’, https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/paleo-search/study/8637 (accessed August 2022); H. Cheng et al., ‘Jeita Cave, Lebanon 20,000 Year Speleothem Stable Isotope Data’, https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/paleo-search/study/20446 (accessed August 2022).

Table 1. Estimated sown densities, crop yields and seedcorn rates in thirteenth-century Tyre region.

(3) Per land-unit yields in thirteenth-century Frankish Tyre region

Seed ratio yields can, however, be a very misleading indicator, as they do not reflect the sheer quantities of grain produced and, by extension, their calorific values. The gross yield of 60 modii of wheat would imply about 275 bushels, while the net yield of 48 modii (harvest minus seedcorn) would make about 220 bushels. The respective figures for legumes and legume-grain mixtures would be around 137 and 124 bushels (equalling the gross yield of 30 modii and the net yield of 27 modii) As noted above, this amount had been harvested from 1.3 carruce, equalling presumably 5.3 hectares or 13.2 acres. If this is true, then Betheron fallāḥīn achieved, respectively, the gross and net yields of about 21 and 16.8 bushels per acre for wheat, and about 4.6 and 4.1 bushels per acre for legumes (see ).

(4) Seedcorn rates in thirteenth-century Frankish Tyre region

While crop yields constitute objective indicators and measures of agricultural performance, there is yet another important measure to be taken into account: seedcorn rates, that is the proportion of each year’s harvest invested in seeding. As noted above, unlike other methods, it provides a better indication of economic growth potential beyond the agricultural sector, as it reflects marketable surpluses beyond the calorific requirements of local producers. Assuming that the 1241/2 harvest reported by Zorzi was ‘average’, it appears that local seedcorn rates stood at about 20 per cent for wheat (12 out of 60 modii, amounting to about 4.2 bushels per acre) and 10 per cent for legumes (3 out of 30 modii, representing approximately 0.5 bushels per acre) (see ).

(5) Calorific yields in thirteenth-century Frankish Tyre region

The best indicator of land productivity, however, would be calorific yields, estimating the total amount of calories produced from one unit of land. To estimate that, we need to have an approximate idea of a relative share of each crop in the total sown acreage. Zorzi reported that the total size of the Venetian estate at Betheron was 5 carruce.Footnote60 Yet, the seeding densities and seedcorn he reported imply that about 1.3 carruce would be sown with wheat and a further three carruce with legumes, making it the total of about 4.3 carruce. What about the remaining 0.7 or so carruce? One possibility is that Zorzi under-reported crop production; indeed, surprisingly, Zorzi did not mention barley, another staple crop of Levantine fallāḥīn – although he clearly did note its cultivation, without specifying its extent, elsewhere in his account. For instance, he mentioned 20 carruce in Batiole (presumably, Batouliye = باتوليه, some 9 km south-east of Tyre; coordinates: 33°13’33"N, 35°15’29"E), with each carruca sown annually with 9 modii of grain (presumably, wheat) and barley, between them (quelibet caruca seminantur annuatim inter granum et ordeum novem modiis).Footnote61 Hence, the omission of a barley field at Betheron from Zorzi’s report, possibly corresponding to 0.7 or so carruce, remains a possibility. It is also possible that inter granum et ordeum meant that wheat and barley would have been sown on the same field in an alternate rotation, rather than together. Hence, when estimating the calorific yields per acre (see below), I have added barley, assuming similar seeding densities, but higher yields (about 20 per cent higher than wheat).Footnote62

Table 2. Estimated sown densities, crop yields and seedcorn rates in thirteenth-century Tyre region, Mediterranean regions and northern Europe.

To get a possible glimpse into a breakdown of sown acreage in late-medieval Tyre region, an analysis of cadastral surveys would be essential. Unfortunately, Mamluk surveys (rawks) for Syria from 1313–4 and 1317 and 1325 have all been lost.Footnote63 The closest thing in time would be sixteenth-century Ottoman tahrir defterleri. On the basis of the 1535 tahrir defter from the Bilād ash-Shām region, recording hundreds of villages in an area between Sidon and Tyre, it is possible to estimate a relative contribution of each crop in the region – once adjusting the figures slightly, to account for likely under-recording of legumes. It appears that wheat occupied about 70 per cent of all sown acreage, barley about 25 per cent, legumes and sesame about two per cent each, and red millet about one per cent.Footnote64 These figures do not square up Zorzi’s account, reporting two carruce for grains and three carruce for legumes, which yields an unlikely breakdown of 40 and 60 per cent for the two types of crops, respectively. This certainly looks suspicious: to my knowledge, there is no known instance, in any chronological or geographic context with existing data, for such a huge proportion of land devoted to legume cultivation. It is likely, therefore, that the three carruce sown with legumes and defined by Zorzi as ‘fallow’ (garitus/terra macatica/terra frata) had, in fact, been sown with cereals in the previous year and left fallow during the year of his inspection. That fallow would occupy a large proportion – about half – of all arable land is hardly surprising: such a situation prevailed in the Levant throughout the Ottoman period into the mid-twentieth century.Footnote65 Hence, assuming, still in an arbitrary manner, that the shares of other crops in the Tyre region were not much different in the Frankish period, we may now convert each bushel of crops into their calorific equivalent.

One bushel would yield around 87,000 kcal for wheat, about 71,000 kcal for barley, 24,000 for legumes, and 120,000 for sesame.Footnote66 Importantly, we have to account for losses incurred during harvesting and storage – estimated to be in the area of 10–15 per cent in pre-Industrial farming societies.Footnote67 Deducting (perhaps somewhat optimistically) 10 per cent for each crop, we arrive at about 78,000 kcal for wheat, 64,000 kcal for barley, 21,500 kcal for legumes and 107,500 kcal for sesame. Finally, assigning each crop its relative share in the sown total acreage, we may estimate the approximate calorific yields, standing at approximately 1.2 million kcal per acre, deriving from about 18.5 net bushels of ‘composite crops’ per acre ().

Agricultural productivity in Frankish Tyre region in a wider perspectiveFootnote68

How did Tyrian (and more generally, Levantine) fallāḥīn perform in comparison to their counterparts elsewhere in the world – and, more specifically, elsewhere in the Mediterranean world and northern Europe? , based on agricultural data and estimates from different regions, places agricultural production in the Tyre region into a wider context.

(1) Wider Mediterranean world

Again, any such discussion should begin with the question of seeding density rates. Seeding rates of wheat in thirteenth-century Syria appear to be higher, indeed much higher than elsewhere in the Mediterranean in general. It is possible to estimate, in a crude manner, that seeding density rates in fourteenth-century Iberia stood at about 2.1 bushels (1.8 for wheat and 2.4 for barley), while in central and northern Italy (with the exception of fertile Lombardy), they were around 2.2 bushels per acre around the same time. In Sicily and Egypt, they were only 1.8 and 1.5 bushels per acre, respectively. It appears that seeding density rates were inversely correlated with (1) land productivity and (2) landholding sizes. In the case of Spain, local peasant families held relatively large parcels of land (on average, 20–25 acres in Catalonia and 15 acres in Valencia).Footnote69 Egypt and Sicily, two bread baskets of the Mediterranean, were blessed with remarkably fertile soils, making them among the most productive agricultural regions in the world around 1300.Footnote70 By contrast, Syrian fallāḥīn were blessed with neither exceptionally productive soils, nor with large land plots. Although William of Tyre noted the exceptional fertility of soil around Tyre, his words, as we have seen, should be taken with a grain of salt. If anything, Tyrian soil may have been more fertile in comparison to other regions in the Frankish Levant (as will be suggested below) – but not elsewhere in the Mediterranean. The size of holdings of local fallāḥ households and their capacity to produce sufficient food for their members will be discussed below.

As far as legume seeding densities are concerned, they appear to be thinner than elsewhere in the Middle East or the wider Mediterranean world: normally, these would have been in the area of 2.5 bushels in Iberia, 1.5 bushels per acre in Sicily and just under one bushel in Egypt.Footnote71 Unless Zorzi supplied incorrect estimates, such discrepancy in seeding yields between Levantine peasants and their counterparts in the wider Mediterranean can only be explained by the possibility that Zorzi reported fallow that had been sown with grain the year before his inspection and that fallow would be planted much thinner than sown land.

Now to yields. Seed ratio yields were certainly higher in Egypt and Sicily, where local farmers managed to achieve the gross yields of ‘composite’ crops in the region of 16:1 and 13:1 (and about 15:1 and 12:1 for net yields),Footnote72 – indeed, much higher than the gross composite yields of about 5.2:1 (that is, a ‘weighted’ average taking into account a relative proportion of the acreage of wheat and legumes, yielding, respectively, the figures of 5:1 and 10:1) or the net composite yields of about 4.2:1, in the Tyre region. The latter figures were lower than composite crop yields of about 6:1 (gross) and 5:1 (net) achieved by Spanish farmers,Footnote73 but higher than those in most regions of northern and central Italy (with the exception of the more productive Lombardy), where local farmers seem to have attained the gross yields of only 4:1.Footnote74

In terms of calorific yields per acre, Tyre-region fallāḥīn appear to have performed quite well. With about 1.3 million kcal per acre deriving from 18.5 net bushels, they were not quite as successful as their Egyptian and Sicilian counterparts, both achieving about 1.4 million kcal from 21–22 net bushels, but certainly more advanced than Iberian farmers with about 0.71 million kcal from about 10.3 net bushels, and certainly much more advanced than north/central-Italian peasants (again, not accounting for the more productive region of Lombardy) with only 0.45 million kcals from about 6.6 net bushels.

Finally, in terms of seedcorn rates, Tyre region producers fared worse than Egyptian and Sicilian farmers (both achieving remarkably low figures of just 7–9 per cent), standing more on a par with Iberian farmers (about 17 per cent), and certainly boasting lower figures than most north- and central-Italian peasants (about 25 per cent).

(2) Northern Europe

What about northern Europe? The most obvious point of comparison would be France, the original home of the majority of European settlers in the crusader states. When talking about ‘France’ within the borders of Louis IX’s kingdom plus the region around Lille controlled by the counts of Flanders, we have to take into account regional differences in soil fertility, types of crops cultivated and agricultural techniques. Consequently, crop yields would vary from very high in the Lille region, where advanced Flemish cultivation methods were practiced, to low yield across the Atlantic coast and Breton uplands. Taking all the regions together and assigning each crop its approximate relative weight in the total sown acreage, we may estimate the seeding densities of about 2.5 bushels for both wheat and legumes. Seed-ratio yields would, naturally, vary a great deal from region to region, but an approximate composite figure of 5.4:1 for gross yields and 4.4:1 for net yields – marginally higher or comparably with those in the Tyre region – should not be too removed from reality. Because of thinner seeding rates, an average French acre rendered less than that in the Tyre region: about 10.7 net bushels equalling approximately 0.75 million kcal of composite crops. Seedcorn rates appear to have been in the region of about 19 per cent, comparable with the figures from the Tyre hinterland.Footnote75

Elsewhere in northern Europe – German-speaking territories and England – crop yields were considerably lower than in the Tyre region, with local producers extracting about half the calories from one sown acre, deriving from about 9 net bushels of composite crops. In terms of seedcorn rates, these would amount to about one-quarter (or slightly higher) of an average harvest.Footnote76 In a sharp contrast, much higher yields of about 18 net bushels rendering about 1.14 million kcal (that is, slightly less than in the Tyre region), were achieved by Flemish farmers. Unlike producers from both the Tyre area and other regions in northern Europe, Flemish peasants managed to get by with very low seedcorn rates, standing at no more than 10 per cent – thanks to their advanced technologies in fertilisation and field systems.Footnote77

(3) Does arable productivity in the Tyre region reflect the Frankish Levant?

Just as we used sixteenth-century Ottoman tahrir defterleri to establish an approximate breakdown of crop shares in the Tyre region, we should do the same for all arable regions of Syria-Palestine, in order to estimate crop yields and production levels there. On the basis of the 1535–6 defterleri from the Aleppo and Bilād ash-Shām regions, as well as the c. 1519, c. 1531, 1548, 1557 and 1596 defterleri from different regions of Palestine (Gaza, Nablus, and Jerusalem), together recording thousands of villages, it is possible to estimate that wheat occupied about half of all sown acreage, barley about 42 per cent, sorghum (durra), millet, legumes and sesame about two per cent each.Footnote78 It is unlikely that sorghum had been cultivated in the Tyre region around 1240; around the same time, it had been only recently introduced into Egypt, on a very small scale, as a staple food of the poorest. Indeed, a 1245 Ayyubid cadastre from the Faiyum region did not mention durra at all.Footnote79 Hence, it is unlikely that by the time of Zorzi’s report, the cultivation of this crop had spread into Syria-Palestine. Assuming, in a totally arbitrary manner, that the shares of other crops were not much different in the Frankish period, we may speculate that around the time of Zorzi’s report, an approximate ‘average’ proportion of the sown crops was 50 per cent for wheat, 43 per cent for barley, 3 per cent for legumes and 2 per cent for sesame and millet, respectively.

Now, we have to bear in mind that the Tyre region was among the most fertile ones in Syria-Palestine. Indeed, this agrees with William of Tyre’s comment on a remarkable soil fertility in and around Tyre.Footnote80 The fact that Tyre-region fallāḥīn in the Frankish period achieved higher yields than their counterparts elsewhere in Syria-Palestine is also hinted at in the fact that seeding densities around Tyre were about 1.2 times thinner than in the Beirut region and about 1.33 times thinner than in the Ascalon hinterland, as stated above. The comparative fertility of the Tyre region is noted by late-nineteenth and early twentieth-century observers, such as Leo Anderlind, Arthur Ruppin and Fritz Grobba. Taken together, these late reports reveal that on the eve of WWI, the Tyre and Damascus regions would achieve at least twice as high a yield as those in Palestine.Footnote81 In this sense, these regions were the most fertile ones, second only to the Hauran region, blessed with exceptional fertility thanks to natural lava deposits in soil. These gaps, however, could well be a product of a regional dimension of agricultural improvements in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, with Syrian agriculture growing faster than the Palestinian one – as indeed reflected in gaps in yields and seeding densities, reported by European observers. If that is the case, then back in the Frankish era, these regional gaps in yields were not nearly as pronounced and it is possible that the ‘average’ composite yields in Frankish and Ayyubid (and later Mamluk) Levant may have been perhaps 10–30 per cent below the Tyre region figures. establishes three hypothetical scenarios for average composite yields across all arable regions, in relation to the Tyre region estimates: (1) seed ratios were 10 per cent lower, but seeding densities were 10 per cent higher; (2) seed ratios were 20 per cent lower, but seeding densities were 20 per cent higher; (3) seed ratios were 30 per cent lower, but seeding densities were 30 per cent higher. According to these estimates, with seed-ratio yields between 3.7 and 4.8 and seeding densities between 5.1 and 4.3, bushels per acre and seed-ratio yields between 4.8 and 3.7, an ‘average’ Levantine fallāḥ would have achieved anywhere between 14 and 16.5 net bushels per acre, producing between about 0.9 and 1.1 million kcal per acre – investing between 21 and 27 per cent of annual harvests in seedcorn.

Table 3. Hypothetical sown densities, crop yields and seedcorn rates in thirteenth-century Syria-Palestine.

Even the lowest estimate, assuming that the Tyre region yields were about 30 per cent higher than elsewhere in Syria-Palestine, implies that local fallāḥīn extracted about 1.26 times more calories from one acre than French and Iberian peasants, about 1.60 times more than German and English farmers and twice as much as their Italian counterparts. Yet, it was achieved at a much higher labour cost. Incredibly dense seeding rates practiced by Levantine fallāḥīn meant that each acre had to be sown much more intensively than in Europe. Although there is no hint or evidence about labour productivity rates in medieval Levant, anthropological work from northern Jordan, conducted in the 1960s, has shown that an average local fallāḥ, still using traditional (pre-Industrial) methods of cultivation, was ploughing, on average, about 0.5 acres a day – slightly less than 0.6 acres per one man-day achieved by Greek farmers and 0.7 acres by Sicilian and south-Italian peasants in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.Footnote82 By contrast, an average English peasant around 1300 was ploughing about one acre a day – comparable with figures achieved by Prussian and Austrian farmers c.1800.Footnote83 The same work has also found that an average local fallāḥ would reap about two bushels of wheat per man-day – more than about 1.5 bushels done by a Greek farmer c.1900, but much less than 5 bushels done by an English peasant c. 1300.Footnote84

The comparatively low labour productivity rates in traditional Levantine agriculture were connected to both technological and environmental factors. Local fallāḥīn (and other crop producers in the Mediterranean and Red Sea regions) have been relying on the traditional man-pulled light plough, continuously prevalent in the Levant since the fifth century BCE, and on the sickle for reaping. By contrast, north-European peasants were using a heavy-wheeled plough driven by horse- or ox-teams, both faster and more powerful than the Mediterranean plough. In addition, we witness the first signs of a shift from sickle to scythe in England on the eve of the Black Death. No less important is a climatic factor: Levantine climate is considerably drier and hotter than in northern Europe. Even if ploughing in medieval Syria-Palestine started with the beginning of a rainy season in autumn,Footnote85 some October days can still be quite hot in that region. By contrast, harvesting occurs in hot days of May-June. This, in turn, may explain why agricultural work hours were shorter in the Levant and why labour productivity of local fallāḥīn was lower than that of north European peasants. Bearing this in mind, together with very thick seeding densities, we may safely conclude that even though one acre yielded more calories in Syria-Palestine than in most European regions, production costs of each calorie and, hence marginal costs of agricultural production in general, were higher – indeed considerably higher – in the former than the latter.

Going back to Urban II’s Clermont speech on 27 November 1095 (carried amidst a bad crop failure and a harsh subsistence crisis all over western and central Europe), one may ask if the pope promised his audience too much when he portrayed the Holy Land as a land which ‘floweth with milk and honey’, in contrast with France, depicted as poor and infertile?Footnote86 Yes and no – and much depending if Zorzi’s evidence from a single village from the Tyre hinterland indeed reflects a situation in a ‘normal’ year, and if our extrapolation of ‘average’ levels of Levantine productivity are not too far off. On the one hand, one acre in Frankish Syria-Palestine may have produced considerably more calories – between 1.3 and 1.6 times more – than in northern/central France. But such high calorific yields were not a result of high seed-ratio yields: as we have seen, the composite seed-ratio yields were about the same as in France. Rather, it was thanks to very high seeding densities within the grain sector, standing at 4–5 bushels per acre, and, consequently, very intense and potentially costly arable labour. Whether such high seeding densities were linked to small arable land plots of local fallāḥ households (possibly reduced as a consequence of the expansion of commercial viticulture and sugar-cane cultivation by Frankish lords as argued below), or to local agricultural customs remains to be studied. What is especially important is that in terms of seedcorn rates, both France and Syria exhibited similar figures, reflecting, at least in theory, the same potential for urbanisation, regional division of labour and long-term economic growth. Yet, as we know, both regions would march at a different economic pace and reach different economic heights during the so-called ‘Great Divergence’ of the early modern period.

Did Levantine fallāḥīn have enough land?

What do the arable production estimates above tell us about the capacity to provide food for local fallāḥ households? The information about the size of local landholdings is extremely scarce. In fact, our only glimpse into the topic is Zorzi’s report recording that local fallāḥ households held about two carruce of land (namely, about 6–8 hectares or 15–20 acres of land). At first, these figures appear to be large enough, on a par with the situation in Iberia. However, if family landholding size around Tyre reflects the situation elsewhere in Syria-Palestine, then why were local fallāḥīn sowing so densely, as far as wheat is concerned – indeed, twice as densely as their Iberian counterparts? One possibility is that some proportion (perhaps about half) of all their arable land was lying fallow each year – as indeed reflected in a large share devoted to fallow (garitus/terra macatica/terra frata), thinly sown with legumes. But another possibility is that local Muslim (and presumably East Syriac) nuclear families were larger than their Iberian Christian counterparts. Thus, the size of a late-medieval Catalan family has generally been assumed to have consisted of five people.Footnote87 Comparable information on family size of Levantine fallāḥīn is extremely scarce and inconclusive. On the one hand, according to Zorzi’s report, an average male household head had 2.2 sons, which, assuming the same number of daughters, translates into 4.4 children, rendering a family of about 6.4 souls (parents and 4.4 offspring).Footnote88 Some families may have been larger still: an average household of the Banu Qudāma tribe, fleeing from the Nablus region to Damascus between 1156 and 1173, consisted of about 7.5 souls on average.Footnote89 The idea that some local families may have been larger than their Christian counterparts in the western Mediterranean is reflected in sharīʿa court minutes from Aleppo for the period 1746–71, where an average deceased father had about 4.8 children.Footnote90

However, these examples may not be reflective at all. In the case of Banu Qudāma refugees, their tribe was headed by a Ḥanbali jurisconsult – undoubtedly a prominent and better-off individual – meaning that these families were anything but ‘average’ ones.Footnote91 After all, we do not know how many of the family heads practiced polygamy. In the mid-eighteenth century, Aleppo was still a wealthy city, engaged in long-distance trade with both Europe and other regions of the Ottoman Empire, and it was not until the 1760s–1770s that we see clear signs of the city’s economic decline.Footnote92 Moreover, large families in eighteenth-century Aleppo and, consequently, a demographic growth in Syria were a product of various technological and structural improvements in local agriculture, discussed above. Finally, some of Aleppo court entries indicate clearly that some of the surviving children were from previous marriages. Therefore, using these records could be something of a red herring.

A few surviving Mamluk-era demographic records may provide a better hint. Thus, evidence from late Mamluk Jerusalem, deriving from Ḥaram waqf inventories for the period AH 774–98 (1372/3–1395/6CE), that record possessions of local deceased, reveals a much smaller number of children per family: 2.7 on average.Footnote93 Similarly, usually three, and rarely more than four children per family were mentioned in waqf documents from the Damascus region on the eve of the Ottoman conquest in summer 1516.Footnote94 Unlike Zorzi’s account, waqfiyyas recorded children of both sexes and hence it is unlikely that they would massively, if at all, under-record the number of children. One explanation for such a low number of children is that in both contexts, that is late fourteenth-century Jerusalem and early sixteenth-century Damascus, there were recurrent plague outbreaks at different intervals.Footnote95 Likewise, late nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Ottoman Nüfūs registers, vilayet yearbooks (salname) and regional cadastres for Syria and Palestine suggest that an average household consisted of 5–6 people.Footnote96 Both Zorzi’s report and late Ottoman registers were compiled in plague-free periods, with the former some 100 years before the beginnings of the Second Plague Pandemic and with the latter some 40 years after the disappearance of the Second Plague from the Levant. Therefore, Zorzi’s figures, assuming to have reported only half of the children, may not be too far from reality, and local fallāḥ families were larger in size than their counterparts in Christian Iberia. In this case, the same 15–20 acres held by an average both Valencian and Tyre-region family may have been sufficient for the former but not for the latter – which may, in turn, explain the remarkably high seeding densities of wheat by Betheron fallāḥīn. As we shall argue later, the situation may have been compounded further by the expansion of vineyards and sugar cane plantations, leaving even less land for the cultivation of basic foodstuffs by local farmers. If anything, family size in the Tyre region may have been actually larger than elsewhere in the Frankish Levant – owing to favourable agricultural conditions, which may have produced higher yields than elsewhere, as suggested below.

Let us, in absence of additional data, stick to the estimate of 6.5 individuals per fallāḥ household and assume that such ‘average’ household would hold 15–20 (say, for the sake of convenience, 18) acres. It is unlikely, however, that the entire area of these holdings would be utilised for arable cultivation. At least some proportion would be occupied by buildings and, presumably, used as pasture for livestock. Hence, we may deduct, in an arbitrary manner, at least several acres – let us say, four. Of the remaining 14 or so acres, about half would, as argued above, be lying fallow each year (occasionally thinly sown with legumes, thus producing very little), leaving about 7 acres, sown with grains, yielding collectively about 8.4 m kcal, net of spoilage, a year (about 1.2 m kcal per acre). These amounts would equal about 23,000 unprocessed kcal per day, or about 20,000 processed kcal per day (assuming that wheat milling, sieving and baking would entail a calorific loss of about 20 per cent, Footnote97 and that barley was converted into pottage, rather than baked or brewed). In this case, each household member would have been endowed with about 3,000 daily kcal. This appears to have been more than needed: as evidence from mid-seventeenth century Damascus indicates, bread would have contributed around 70 per cent to the total food intake of local workers, with the remainder made up of beef, fish, dairy, olives and vegetables.Footnote98 If the ratio was similar in thirteenth-century Syria, then local fallāḥīn would have, in theory, about daily 4,300 kcal per capita. These figures, however, are unrealistic: around 1300, an ‘average’ English peasant, suffering from rural congestion and low living standards, may have had twice as little to eat.Footnote99 Unlike England (and other parts of northern Europe), there is no evidence of overpopulation in the Frankish Levant, implying that local fallāḥīn would have been better fed than their English counterparts. But even assuming a per-capita consumption of 3,000 kcal – on a par with mid-eighteenth-century Damascenes – we still end up with a surplus. Hence, two mutually inclusive possibilities remain: (1) the proportion of sown land was smaller than assumed above; (2) fallāḥīn would market a non-negligible proportion of their annual grain harvests to neighbouring cities, towns and castles. The remits of the present paper do not allow to delve deeper into this question.

European exaggeration of crop yields: a ‘colonial’ fascination with exotic lands?

If seed ratio yields in the Frankish Levant were either on a par or lower than those in some regions of Europe, and if production was both slower and costlier, why, then, Frankish authors, such as William or Tyre, and European pilgrims, such as Daniil of Kiev or Burchard of Mount Sion, provide such fanciful and misleading descriptions of local yields and productivity? As we have seen, their statements are based on Biblical and quasi-Messianic tropes, reflecting partly their euphoric state of mind, in conjunction with their sojourn in the Holy Land. But in addition, these statements also reflect a fanciful European perception of far and exotic lands as rich in good land and plentiful in harvests. This excessive optimism was linked, at least in part, with the legend of Prester John, emerging in the early twelfth century. Thus, in a letter, fabricated c. 1165–70, most likely in Germany, the enigmatic king stated that his land flows with honey and abounds in milk, and that in a certain province Lord rains manna abundantly twice a week, feeding local communities.Footnote100 Recollecting his travels via central Asia into China (1271–5), Marco Polo talked about ‘a great abundance of crops and every kind of grain’ in the City of Cinguy (most likely, Chuzhou in eastern Anhui province),Footnote101 out of which Caramoran (Yellow River) flows into the land of Prester John.Footnote102 The ‘milk and honey’ trope is even found in Kirjalax Saga, an early fourteenth-century Old Norse fictional romance. Here, Kirialax, the main protagonist, and his companions, having sailed from the Holy Land for India, found honey dew on grass smeared in local fields.Footnote103

Similar descriptions full of superlative adjectives and unrealistically exaggerated numerals are found in later travelogues of European travellers to Asian and African lands during early-modern and colonial eras. Ethiopia – a land often associated by Europeans with Prester John – was perceived as a region of outstanding agricultural abundance. Some early nineteenth-century European visitors, including French Pierre Ferret and Joseph Galinier (early 1840s), Theophile Lefèbvre (1839–43), British Douglas Graham and Charles Beke, and German Wilhelm Eduard Rüppell (1830), commented on the remarkable abundance of local land produce. In particular, Beke alleged that local farmers achieved on average 100-to–150-fold yields, and sometimes as high as 400:1, while Rüppell reported sorghum yields of 2,000:1.Footnote104 In reality, grain yields in nineteenth-century Ethiopia seem to have been in the area of 10–20:1 and sometimes less.Footnote105 Similarly, Johann Wilhelm Müller, a Lutheran missionary visiting the kingdom of Fetu on the Gold Coast (today’s Ghana) in 1668, alleged that local yields of millet and maize stood at 100:1.Footnote106 Several Portuguese and Italian travellers, visiting west Africa between the late fifteenth and seventeenth centuries, recorded that local farmers would produce abundant harvest with a little labour, using their hoes.Footnote107 In reality, as evidence from Senegambia from 1820s–40s suggests, local composite crop yields were not higher than 40:1.Footnote108 In the same vein, Carsten Niebuhr, a Danish-German explorer travelling all over the Arabian peninsula in 1761–7, alleged that sorghum yield in the Yemenite highlands stood at 140:1, while in the Tihama region (the west coastline of the desert) they reached 200–400:1.Footnote109

The same fanciful perception was shared by European visitors to the Holy Land. Even William of Tyre, although a native of Jerusalem, was European through and through, showing very little to no sign of cultural assimilation into his native Levantine world, as evidenced by his very limited-to non-existent knowledge of the Arabic language (and indeed anti-Muslim bias).Footnote110 Rather, his views on Levantine agriculture was not different from those of contemporary European pilgrims to the Holy Land or, say, nineteenth-century travellers to Ethiopia. One may also add that as an individual standing at the very forefront of high politics of the kingdom of Jerusalem – serving as chancellor and archbishop of Tyre at the peak of his career – William was somewhat ‘detached’ from the realities of everyday life. It should be noted that unlike their Christian counterparts, Muslim writers, while widely commenting on land fertility of Syria-Palestine, avoided mentioning any fanciful figures related to crop yields and harvests.

Clearly, the same ‘colonial’ fascination of European writers and travellers with the fertility and riches of the Holy Land mirrors their fascination with spices. Here, too, spices were associated, in medieval European imagination, with heavenly lands, Paradise, situated in the distant, alluring, magnificent and – importantly – plentiful East.Footnote111 Again, this exotic commodity, highly regarded and valued in Europe, was linked to the kingdom of Prester John. Already in the fabricated letter of c. 1165–70, the king boasts about pepper grown in abundance in one of his provinces.Footnote112 The same association of Prester John with spices is found in other accounts, including that of John Mandeville (writing c. 1360), Bertrandon de la Broquière (travelling in the Holy Land in 1432–3 and writing in 1457), and Francisco Álvares (writing in 1526/7).Footnote113

Arable productivity in the Frankish Levant: a long-term deterioration?

While the discussion above may explain the idyllic depiction of local agricultural fertility by European observers, it surely does not explain similar narratives by Muslim authors both before and during the Frankish dominance. It should be borne in mind that the majority of Islamic geographers and travellers discussed earlier wrote in the pre-Frankish period, while later authors, such as al-Idrīsī and Abū al-Fidāʾ borrowed from their predecessors.Footnote114 Could it be that their narratives reflected an earlier and better reality compared with that of Zorzi?

Some Cairo Genizah documents may provide valuable hints. Fortunately, there are a number of Qaraite fragments discussing the state of arable fields in Palestine, at least three of which mention barley yields as estimated by local fallāḥīn, around the time of aviv (spring) harvest. According to one, the 1027 barley harvest in Gaza region yielded 6 qafīz from 0.5 qafīz, thus rendering the seed ratio of 12:1.Footnote115 According to a 1052 document from the same region, barley yields stood at 20:1 (deriving from 20 qafīz harvested in relation to just one qafīz sown in the previous year).Footnote116 Finally, an undated fragment from the first half of the eleventh century (whose provenance could not be determined) notes thirty qafīz harvested from two qafīz sown (thus, the yield ratio is 15:1).Footnote117 These figures are considerably higher (2.5–4 times) than those implied by Zorzi’s report. Even assuming that barley yields were usually higher than the wheat ones as some sources hint, the gap could not have been that wide.Footnote118 Although the Tyre region was, as we have seen, among the most fertile regions in Syria-Palestine, the Gaza hinterland may have been as fertile. The Franciscan Francesco Suriano, travelling in the Holy Land in 1481–4, described it as a region ‘most abundant in crops’.Footnote119 Remarkably, Meshullam of Voltera, an Italian-Jewish merchant, visiting the Holy Land at the same time (1481), noted Gaza as a ‘fine and fertile land’, rich in bread and wine.Footnote120 The Ottoman defterleri of c. 1519, c. 1531, 1548, 1557 and 1596 indicate that wheat occupied, roughly, half of all arable crop acreage in the region, with some villages sowing up to 70 per cent of their tilled land with wheat – indicating the fertility of the region’s soil.Footnote121 Finally, Anderlind (1886) estimated very high yields of both wheat and barley (anywhere between 5 and 30:1 and 20 and 120:1, respectively) in the Philistine Plain.Footnote122 The conundrum, however, becomes all the more difficult when we consider a seventh-century Greek papyrus from Nitzana/Nessana (south-west Negev), recording the wheat and barley yields of nearly 7:1 and 8.5:1.Footnote123 Unlike Gaza, the Negev is an arid desert region, where crop yields, even with the help of irrigation, could not have possibly been higher than those in the Tyre region.Footnote124

To appreciate why Zorzi’s figures do not square up with either the Genizah or the Nitzana/Nessana papyrus ones, it is essential to consider both climatic and anthropogenic factors. Let us start with the former. The eleventh-century climatic deterioration in the Eastern Mediterranean, leading to various demographic, socio-economic and political crises, has been studied in depth by Ronnie Ellenblum.Footnote125 Although textual references to dry conditions analysed by Ellenblum are at odds with the palaeoclimatic record deriving from isotope data from Sofular Cave (north-western Anatolia), suggesting the tenth through twelfth centuries as a somewhat humid period, isotopes from sediments in Lake Van (the Armenian highlands) indeed corroborates textual evidence.Footnote126 Moving on to the Frankish period, the isotopes from both Sofular Cave, coupled with those from Lake Nar (central Turkey) and speleothems from Jeita Grotto (about 20 km north-east of Beirut) all suggest the period of the 1230s–50s as pronouncedly dry, while Sofular Cave suggests a long-term dry period in the 1180s–1260s (). Given that Syria and Palestine (except the southern regions of the Dead Sea, Negev and Arabah) were relying on dry cultivation of arable crops, rather than irrigation (which was reserved for sugar cane and cotton plantations),Footnote127 prolonged dry spells could have some negative implications for crop yields. At the same time, if this change happened, it was anything but dramatic or extreme: between 1200 and 1260, I was unable to find any textual reference to any subsistence crisis in Syria-Palestine caused specifically by drought (as opposed to one caused by locust migration or earthquake, both recorded on several occasions in that period).Footnote128 Thus, the figures of the 1241/2 harvest may have been a product of a persistent dry reality of the early thirteenth century, rather than a short-term weather anomaly. In any event, the existing palaeoclimatic record for later-medieval Eastern Mediterranean in general and Syria-Palestine in particular is extremely scarce, allowing only very tentative insights into local climate conditions.

With all its unquestioned importance, Nature has never been a single cause of any historical phenomenon, simple or complex. It is essential, therefore, to consider anthropogenic factors triggering structural changes. Let us turn to non-grain sectors of agriculture in the Frankish period – which is the topic of the remaining part of the article. As we shall see, it was wine and sugar, rather than farinaceous crops that seem to have attracted European settlers, both lords and burgesses, because of their economic profits. In the course of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, vineyards and sugar cane plantations expanded considerably in both area and importance, at the expense of the shrinking arable sector. The under-investment and lack of interest in the arable sector is reflected in increasing reliance on grain imports from Sicily, south Italy and the Black Sea littoral. Is it possible that the same under-investment and lack of interest led to negligence and mismanagement of arable fields by Frankish producers, their tenants and farm workers? This would be in stark contrast with early eleventh-century Qaraite landowners, whose documents, cited and discussed above, reveal a remarkable attention to micro-management of local fields by agricultural workers, which included field inspection, evaluation and classification of different grain stalks, as well as estimation of pre-harvest crop yields.Footnote129 As some studies of late-medieval English agriculture have shown, efficient management and investment were the keys to improvements and high productivity – and the other way around.Footnote130

There is another factor to consider. The converse process of the piecemeal expansion of sugar cane plantations and vineyards and shrinkage of arable fields would imply that local fallāḥīn, with less land in hand, may have had to intensify their grain cultivation methods – as indeed reflected in high seeding densities. The possibility of boosting up yields by increased manuring may not have been an option, because of persistent deficiency of livestock – a sector separated from arable farming (unlike the mixed farming system of north-western Europe, whereby both arable and livestock husbandry are practiced on the same farms and are closely integrated into each other).Footnote131 Intensification would imply increasing workloads, decreasing efficiency and soil overexploitation, leading inevitably to diminishing returns. The only way to avoid poverty, overpopulation and socio-economic crises, according to Ester Boserup, is to develop agricultural improvements via technological innovationsFootnote132 – something that neither Frankish lords would nor local fallāḥīn could do. If such a sad reality prevailed in the thirteenth-century Levantine countryside, then it may echo a similar situation in northern Europe, where a sustained population growth in c. 1000–1300 led, with some notable exceptions of some regions like the Low Countries and east England, to intensification of agriculture, falling yields, declining living standards and ensuing economic crises some 50–80 years before the Black Death.Footnote133

Importantly, long-term decline in agricultural productivity in the pre-Industrial world is not something unheard of. Thus, c. 1300 Sicily, Egypt and India boasted considerably higher crop yields than they did c. 1800 or 1900.Footnote134 But no other region exemplifies this phenomenon as clearly as Mesopotamia. In the Early Dynastic Period (c. 2900–2350 BCE), local farmers, relying on irrigation and labour-intense cultivation, are reported to have achieved 84-fold barley yields. During the Old Babylonian (c. 2000–1600 BCE) period, the figures fell to 20:1, then to 9:1 and lower in fifteenth- and fourteenth-century BCE Nuzi (south-west of Kirkuk), while in the early nineteenth century, the yield of 6:1 was standard in Iraq.Footnote135 If our interpretation of patchy data is correct, then much the same process can be detected in the Levant in the period under study.

Colonial agriculture: vineyards and sugar cane plantations

While the perception of European pilgrims was exaggeratedly biased because of the combination of quasi-Messianic euphoria and ignorance of local conditions, the same thing cannot be said about the vast majority of Frankish immigrants to the Levant – both landlords and burgesses. The fact that many of them chose a long-term settlement (oftentimes spanning several generations) in a rural environment, meant that they knew and understood local agricultural conditions well – with neither illusion nor exaggeration. If Levantine crop yields were faring hardly better than back in France, what did, then, attract Frankish immigrants in the course of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries?

In 1095–6, a great multitude – tens of thousands – of Europeans left their homes to take part in what is known as the First Crusade. As we have seen, this movement occurred in the context of an agrarian crisis. Yet, with Jerusalem fallen to the crusading army on 15 July 1099, the vast majority of the First Crusade survivors opted to return home. Less than ten thousand – possibly as few as 5,000 Europeans, including perhaps 600 men-in-arms – stayed behind.Footnote136 Why did they not remain in the kingdom? On the one hand, it is possible that having fulfilled their ‘divine mission’, they felt no need to settle there, entrusting the state of affairs to the nascent Frankish elite. But it could also be that they simply got disillusioned with local agricultural opportunities, which were not better than those back home. The number of Frankish settlers grew – albeit slowly – and in the 1120s Fulcher of Chartres, did his best to encourage European migration to the Holy Land.Footnote137 In any event, the population did grow in the course of the twelfth century and by c. 1200, most available land seems to have been claimed by Frankish migrants, as indicated in some sources.Footnote138 What attracted these migrants to settle in the Levant – especially if crop yields were either already low or progressively deteriorating? Of course, we can theorise that sometimes crusading propaganda, depicting the idyllic conditions discussed above, did its trick and some Europeans fell for it, migrating to the Levant. But what attracted them to stay there, once they realised that local grain yields were not any better than back home? If economic factors were indeed a driving force, then local opportunities attracting new immigrants must have been lying within the non-grain sector – namely, viticulture and sugar cane cultivation.

One pronounced impact that the crusading conquest of the Levant had on local economies and landscapes was a drastic expansion of vineyards throughout the country. References to local vineyards are plentiful in both pilgrims’ accounts and charters.Footnote139 In particular, Syrian wine from the Lebanese coastal region was renowned for its excellent quality (and noted by several pilgrims, including Wilbrand of Oldenburg and Burchard of Mount Sion),Footnote140 and exported to Europe in large quantities. Ernoul’s chronicle narrates how Jerusalem burgesses would fill portable basins with abundant quantities of wine to be distributed, together with large quantities of bread, among local paupers, during Lent.Footnote141 When accompanying Louis IX in the Holy Land (May 1250-April 1254), Jean de Joinville purchased as many as 100 tuns (about 21,000 gallons = 95,550 litres) to keep the royal retinue going.Footnote142 Genoese merchants were exporting as many as ten tuns (about 2,100 gallons = 9,550 litres) of Syrian wine on a single ship from the port of Tripoli as late as 1302, that is thirteen years after its fall to the Mamluks.Footnote143 Such large volumes, exported in the early Mamluk era, certainly hint that viticulture must have been practiced on a large scale in the Frankish period, when the numbers of both domestic producers and consumers were undoubtedly much greater before the mass exodus of European settlers after the respective falls of Tripoli (1289) and Acre (1291). That wine trade was a profitable enterprise in the Frankish Levant is reflected in a 1153 royal charter related to the royal estate of Casal Imbert (near Acre). According to the charter, King Baldwin III imposed a rent of one-quarter on the fruit of the vineyards on local tenants, but granted them a tax-free privilege in wine trade in Acre.Footnote144

The reconquest of parts of the Holy Land by Saladin in the aftermath of the battle of Hattin (4 July 1187) resulted in a shrinkage of the scale of wine production, as some vineyards were destroyed by incoming Muslims lords, as indicated by Burchard of Mount Sion. Conversely, some Muslim landowners opted to continue wine production for consumption by their Christian neighbours. Intriguingly, both Burchard and Thietmar report that some Muslims would covertly drink wine, in defiance of their law.Footnote145 The fluctuations in viticultural economy are clearly reflected in the palynological record from coastal Syria, showing that Vitis cultivar accounted for about 7 per cent of the total pollen sample in the period c. 1100–1250, in contrast with about 3 per cent during the late Fatimid era and no cultivation during the Mamluk and Ottoman periods.Footnote146 It is clear, however, that the decline of wine production in Mamluk Syria was piecemeal rather than abrupt: as we have seen, Genoese merchants were still exporting Syrian wine from Tripoli thirteen years after its Mamluk conquest.Footnote147