Abstract

Background

Comprehensive measures to evaluate the effectiveness of medical interventions in extremely preterm infants are lacking. Although length of stay is used as an indicator of overall health among preterm infants in clinical studies, it is confounded by nonmedical factors (e.g. parental readiness and availability of home nursing support).

Objectives

To develop the PREMature Infant Index (PREMII™), an electronic content-valid clinician-reported outcome measure for assessing functional status of extremely preterm infants (<28 weeks gestational age) serially over time in the neonatal intensive care unit. We report the development stages of the PREMII, including suggestions for scoring.

Methods

We developed the PREMII according to US Food and Drug Administration regulatory standards. Development included five stages: (1) literature review, (2) clinical expert interviews, (3) Delphi panel survey, (4) development of items/levels, and (5) cognitive interviews/usability testing. Scoring approaches were explored via an online clinician survey.

Results

Key factors reflective of functional status were identified by physicians and nurses during development of the PREMII, as were levels within each factor to assess functional status. The resulting PREMII evaluates eight infant health factors: respiratory support, oxygen administration, apnea, bradycardia, desaturation, thermoregulation, feeding, and weight gain, each scored with three to six gradations. Factor levels are standardized on a 0–100 scale; resultant scores are 0–100. No usability issues were identified. The online clinician survey identified optimal scoring methods to capture functional status at a given time point.

Conclusions

Our findings support the content validity and usability of the PREMII as a multifunction outcome measure to assess functional status over time in extremely preterm infants. Psychometric validation is ongoing.

Introduction

Survival of infants born extremely preterm, defined as birth at <28 weeks gestational age (GA) by the World Health Organization, and used interchangeably with extremely low gestational age newborn (ELGAN), has improved over time [Citation1,Citation2]. The majority of extremely preterm infants require intensive care in the neonatal period [Citation3], and survivors remain at risk of short- and long-term morbidities, such as intraventricular hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), chronic lung disease, and neurodevelopmental impairment [Citation4–7].

A challenge for this patient population is the lack of outcome measures to evaluate treatment effects in clinical studies, and clinical assessment tools that monitor how the neonates grow and mature over time. While length of stay (LOS) is often used as an outcome measure in clinical studies, LOS can be influenced by nonmedical factors such as parental readiness and availability of home nursing support [Citation8], and institutional variations in organization of care [Citation9], thus limiting the appropriateness of LOS as a measure of infant health and development and as an endpoint in clinical trials. Existing neonatal illness measures, developed primarily to predict mortality and morbidity, combine neonatal data shortly after admission to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) and not over time. For example, the Score for Neonatal Acute Physiology (SNAP) [Citation10] and SNAP Perinatal Extension version II (SNAPPE-II) collect infant data within 24 and 12 h of admission, respectively [Citation11], while the Clinical Risk Index for Babies (CRIB) [Citation12] and CRIB II collect data within 12 and 1 h of admission, respectively, to evaluate risk for mortality [Citation13].

The aim of this study was to develop a comprehensive content-valid clinician-reported outcome (ClinRO) measure, the PREMature Infant Index (PREMII™), to assess the functional status of extremely preterm infants (<28 weeks GA) over time in the NICU, for use in a phase 2 clinical trial. In the current article, we report on the development of the PREMII.

Materials and methods

Study design

Development of the PREMII followed US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulatory guidance for patient-reported outcome instruments [Citation14] – standards that apply to other clinical outcome assessment tools, including ClinROs. The PREMII development process (phase 1) consisted of five stages: (1) targeted literature review, (2) clinical expert interviews, (3) Delphi panel survey, (4) development of PREMII items and levels, and (5) cognitive interviews and usability testing of the electronic version. These stages were designed to provide evidence of content validity (i.e. relevance, clarity, and comprehensiveness) of the PREMII to measure accurately the clinical condition, specifically functional status as it changes over time, of the target population (i.e. extremely preterm infants). Additionally, an online clinician survey was conducted to explore potential approaches to scoring the PREMII.

Concept of interest

The concept of interest that the PREMII is designed to measure is functional status. Functional status is defined as an indicator of neonates’ overall health and development encompassing physical, physiological, and clinical status – specifically, what an infant can do and what support the infant requires, on a day-to-day basis, as a reflection of their overall health and development, which can be also considered as maturation over time. Functional status can be assessed with respect to eight key functional areas included in the PREMII (feeding, weight gain, thermoregulation, respiratory support, apnea, bradycardia, desaturation [ABD] events, and oxygen administration). The PREMII can measure functional status as it changes over time with the baby’s development.

The original target concept for the study was discharge readiness. However, evidence gathered from the literature review and clinical expert interviews highlighted challenges to standardizing assessment of physical readiness for discharge. These included variability in standards of neonatal care, home medical support, and proximity and availability of outpatient support. Therefore, the target concept evolved to functional status, which is independent of the health care system or home situation.

Stage 1: Targeted literature review

A targeted literature review was undertaken to identify relevant concepts for inclusion in the PREMII. We searched Embase, MEDLINE, and PubMed for English-language articles published from 2001 to 2015. The search strategy used search terms relevant to factors, attributes, and measures related to physical discharge readiness and LOS for extremely preterm infants (Supplementary Tables 1–2).

Stage 2: Clinical expert interviews

Telephone semistructured qualitative interviews were conducted. Criteria for inclusion included specialized training in neonatology, with ≥10 years of experience caring for preterm infants (). The interviews were designed to obtain feedback from clinicians on the physical factors infants need to achieve to be considered ready for NICU discharge, as identified by the literature review. See Supplementary Table S3 for an overview of the interview questions.

Table 1. Participant inclusion criteria for the PREMII development stages.

Stage 3: Delphi panel survey

The Delphi method is a structured communication technique that involves participants (in this case, a panel of experts) who answer a questionnaire in an iterative manner after being provided with an anonymized summary of group responses [Citation15]. Participants were asked to rate the relative importance of factors, identified through the literature review and clinical expert interviews, for the assessment of functional status on a scale of 0 (not at all important) to 5 (extremely important). Additionally, participants were asked to provide feedback on the definitions of the levels for each factor, as well as other important aspects related to the factors and level definitions. The levels for each factor were intended to reflect a scale of functional status from very poor to very good. The purpose was to build consensus on the most important factors for evaluation of a preterm infant’s functional status for inclusion in the PREMII, and to determine the importance of factors.

Stage 4: Development of PREMII items and levels

This stage refers to the drafting of the instrument, namely, the formulation of instructions, items or questions capturing each of the identified factors relevant in assessing infant functional status, and response options.

Stage 5: Cognitive interviews and usability testing of the electronic version

Note: cognitive interviews and the online clinician survey occurred in parallel.

Semistructured telephone interviews were conducted in two rounds. The purpose of the cognitive interviews was to assess the clarity of the instructions, items, and levels, as well as ease of completion of the instrument. Additionally, the interviews were designed to elicit any potential logistical difficulties with completing the instrument (e.g. due to nursing shift patterns, and differences in geographical or institutional NICU practices). Usability testing of the electronic version was undertaken via interviews to assess the ease of completion on an electronic device (e.g. a tablet device).

Online clinician survey

The online survey was developed to explore the most appropriate scoring method to capture accurately a preterm infant’s functional status at a given time point during their NICU stay.

The online survey included questions designed to explore the following: the best approach to calculate daily factor scores, the relative importance of each factor in rating an infant’s overall functional status, and the best approach to calculate a weekly summary score. The questions were based on sample infant profiles that were presented to respondents.

Daily factor scores

Participants were presented with example individual factor ratings for each shift over a 24-h period and asked for their opinion on the optimal method to calculate a daily factor score from the shift ratings from the following options: the “most frequent” score across shift scores provided over the 24-h evaluation period, the “numerical average” score across shift scores provided over the 24-h evaluation period, the “worst” (or “best”, as applicable) shift score during that period, the “most recent” shift score during that period, or “other” (with a request to provide details). Respondents were not asked for a preferred method for calculating a daily weight factor score, as weight is not measured repeatedly across shifts.

Relative importance in rating overall functional status

Participants were asked to rate the relative importance (on a scale of 1 [most important] to 8 [least important]) of each factor in rating an infant’s functional status; respondents were allowed to equally rate multiple factors. Respondents were presented with eight clinical examples of infants and their overall functional status scores over a 7-day period. The overall functional status scores were summarized as the infant’s most frequent, worst (or best), average, and today’s score, as well as the trend over the last 3 days ratings recorded over the 7-day evaluation period.

Weekly summary score

Respondents were asked to rate the weekly summary functional status of the infant (very poor, poor, moderate, good, very good). Additionally, they were asked to rate the importance of each rating approach.

The survey was developed in English and then translated into the following languages: Spanish (Spain, Latin America), French (France), German (Germany), Italian (Italy), Portuguese (Brazil), and Japanese (Japan). Translations met the requirements of the ISO 17100 standard.

Data analysis

Data are reported as descriptive statistics (n and percentage, mean, median). For the clinical expert interviews and cognitive interviews, data were analyzed using qualitative methods. For the online clinician survey, a linear regression analysis was performed to compare weekly summary PREMII scores (“most frequent”, “worst”, “average”, “today”, “trend [past three days]”) with the actual weekly scores provided by the respondents (“weekly summary functional status”) for the online infant profiles.

Results

Stage 1: Targeted literature review

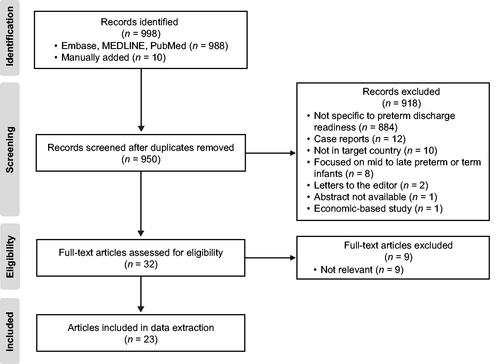

In total, 998 unique abstracts were identified, of which 48 duplicates were excluded. An additional 918 publications were excluded based on predefined exclusion criteria (). A total of 32 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, of which nine were excluded for lack of relevance. The remaining 23 articles were included in the analysis: 19 related to discharge readiness or LOS (original target concept) [Citation9,Citation16–33] (), three discussed instruments for assessing infant mortality/morbidity risk [Citation11,Citation17,Citation34] (Supplementary Table 4; one of these reported findings relevant to both LOS and instruments) [Citation17], and two reported national guidelines on the care of preterm/high-risk infants [Citation8,Citation35] (Supplementary Table 5). No measures specifically assessing physical readiness for discharge were identified. From the included literature, over one-half of the articles noted the infant’s cardiorespiratory stability and weight or ability to gain weight as key factors in determining discharge readiness or LOS ().

Figure 1. Literature identification and study selection process for publications included in the targeted literature review.

Table 2. The number of articles reporting physical and nonphysical factors related to discharge readiness or length of stay in the included studies (n = 19).

Stage 2: Clinical expert interviews

Four expert neonatologists (RMW [USA], MAT [United Kingdom], IH-P [Sweden], JH [USA]) participated (Supplementary Table 6). The findings were similar to those identified in the literature, namely, oral feeding ability, consistent weight gain, physical/physiological stability, respiratory stability (e.g. absence of apnea), and thermostability (capacity to maintain normal temperature; ). Additionally, two clinical experts noted retinopathy of prematurity (one each in relation to discharge readiness and LOS).

Table 3. Key factors influencing discharge from NICU identified by clinical expert interviews.

Stage 3: Delphi panel survey

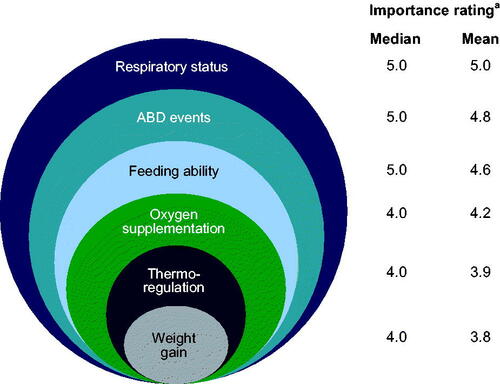

In total, 17 neonatologists participated in the Delphi panel survey (Supplementary Table 6). In order of importance, participants endorsed respiratory status, ABD events, feeding ability, oxygen supplementation, thermoregulation, and weight gain (). Retinopathy of prematurity was originally included but subsequently removed, as it was not considered to fall under the definition of functional status.

Figure 2. Factors important in the assessment of functional status in order of importance rating during Delphi panel survey. aFactors were rated on a scale of 0 (not at all important) to 5 (extremely important) and are listed in order of strength of endorsement (i.e. from highest mean importance rating to lowest). ABD: apnea, bradycardia, desaturation.

Feedback from the Delphi survey highlighted perceived differences in the relative importance of each ABD event in evaluating functional status, and underlined the need to separate ABD events into individual factors due to potential different underlying physiologic causes of events.

Stage 4: Development of the PREMII items and levels

The draft PREMII was developed based on the factors identified in the previous development stages, with further rounds of review by the four clinical experts to refine levels within each factor. Items included in the first version of the PREMII included weight gain, feeding ability, temperature, respiratory support, a single ABD item, and extent of oxygen supplementation.

Stage 5: Cognitive interviews and usability testing of the electronic version

The first round of interviews was completed by 23 physicians and nurses; the second round was completed by nine nurses (Supplementary Table 6). Each of the PREMII items’ levels underwent revisions based on findings from the interviews (). No issues relating to usability of the electronic version of the instrument were identified among the five nurses who participated in usability interviews.

Table 4. Participant feedback from rounds 1 and 2 of the cognitive interviews, and the subsequent revisions made to the PREMII following consultation with the clinical experts.

Online clinician survey

The online survey was completed by 201 pediatricians and neonatologists (Supplementary Table 6). The “numerical average” score across the 24-h evaluation period was the most frequently reported preferred method for calculating daily factor scores for each of the seven applicable factors (respiratory support, oxygen administration, apnea, bradycardia, desaturation, thermoregulation, and feeding; weight gain was excluded from this analysis because weight is not measured repeatedly across nursing shifts; Supplementary Figure 1). In calculating a weekly summary score, the “trend” score over the past 3 days and “today’s” score were most commonly reported to be most important in determining an infant’s overall functional status (53.0 and 34.7%, respectively), based on the previous 7-day period using hypothetical infant profiles. With regard to relative importance, on a scale of 1–8 (most to least important), respiratory support, apnea, and bradycardia were considered the most important of the eight factors (weight included in the assessment) in rating an infant’s functional status (Supplementary Figure 2). However, there was variability among physicians in terms of relative importance of the factors.

Finalization of instrument

The resulting PREMII comprises eight items capturing each of the identified relevant factors (respiratory support, oxygen administration, apnea, bradycardia, desaturation, thermoregulation, feeding, and weight gain), each scored on three to six levels, representing a scale of functional status ranging from very poor to very good (Appendix). The assessment is intended to be repeated over the course of a study to capture change. The intended frequency of administration of the PREMII during a Takeda-sponsored clinical trial is described here. The PREMII assessment will start ≥48 h after birth on the day the infant reaches the next postmenstrual age (PMA) week. For example, if the infant is born at 23 weeks + 4 days, PREMII assessment will begin at 24 weeks PMA, but if an infant is born at 23 weeks + 5 days, PREMII assessment will begin the following PMA week at 25 weeks PMA. In the clinical trial, the PREMII will be administered weekly until 32 weeks PMA and then daily until discharge or 40 weeks PMA, whichever is the earliest. The nurse primarily responsible for the infants’ care will score the PREMII on a tablet device near the end of each nursing shift. The PREMII captures a 24-h period and the number of PREMII assessments carried out during this time will depend on the duration of nursing shifts (e.g. 8 or 12 h). Formal training will be provided for PREMII users before using the tool.

Discussion

We developed the PREMII, a ClinRO with evidence of content validity, designed to measure treatment benefit in clinical trials by assessing the functional status of extremely preterm infants in the NICU. To our knowledge, the PREMII is the first comprehensive multifunction outcome measure developed to capture and measure health and development repeatedly in extremely preterm infants over time from birth until discharge from the NICU.

While illness severity scores are available for the purpose of predicting mortality and morbidity [Citation10–13], they primarily collect infant data within 24 h of admission to the NICU, and are not designed to assess the process of development and maturation over time. LOS is considered an important outcome measure in clinical studies; however, using LOS to assess treatment effect in neonatal studies can be challenging on account of factors not directly related to infant health that may influence time to discharge, such as parental readiness and organizational factors [Citation8,Citation9]. The PREMII includes eight infant health factors (respiratory support, oxygen administration, apnea, bradycardia, desaturation, thermoregulation, feeding, and weight gain), which will enable the assessment of functional status as an outcome measure in neonatal studies, thus providing a comprehensive approach to comparing groups of infants, for example, when examining the effects of treatments.

The development stages demonstrated that the PREMII adequately measures functional status in extremely preterm infants and therefore has good content validity, which is in accordance with US FDA regulatory standards for developing patient-reported outcome instruments [Citation14]. Development of the PREMII was guided by neonatologists and NICU nurses, who provided their opinions based on clinical experience. Through the Delphi approach, expert neonatologists reached consensus agreement on the factors for inclusion in the PREMII, and the importance of factors. An example of this was the consensus that respiratory status and the level of support required would adequately measure the severity of lung disease. Participants represented countries across a number of global regions, including North America, Europe, Latin America, and Asia-Pacific. This approach highlighted cultural differences in clinical practice across regions and aided the development of the PREMII to maximize applicability. Although designed for clinical trials, the PREMII could be used as a key performance indicator in NICUs, for benchmarking between sites/hospitals, or to adjust for illness severity as extremely preterm infants approach term equivalent age. The tool may even provide a structured approach to informing discharge readiness by providing the relevant data to inform discharge decision making. It should be noted, however, that the PREMII is not specifically intended to predict discharge readiness or LOS, but rather to assess functional status over time. Furthermore, although the PREMII was developed specifically for the population of extremely preterm infants (<28 weeks GA), it could be applied to infants born at other GA during their growth and development in the NICU as the factors for assessment will remain consistent.

There are limitations of the PREMII that should be considered. One is that local policies regarding neonatal care may differ (e.g. oxygen saturation limits), as well as definitions of what constitutes an event (e.g. apnea or bradycardia). The difficulty of controlling for differing standards of care and the potential for variability of practice across sites remain a challenge in clinical research. We standardized the factors and level ranges captured by PREMII items to the greatest extent by gaining consensus input from expert clinicians based on global considerations. Additionally, instructions and training are included in the PREMII instrument to minimize variation. A further consideration is the element of subjectivity in the clinician responses (e.g. “worst experience”). The development steps were designed to ensure appropriate and clear response options, to measure the abilities to respond using the response options, and consistency of interpretation across respondents. PREMII items and levels were developed with extensive clinical expert input and we expect a high degree of consistency in item interpretation; there remains, however, the possibility that interpretation may vary among clinicians. We acknowledge that some factors (e.g. feeding and weight gain) can be affected by various comorbidities, such as NEC; this will be further explored in a separate study (outlined below).

A separate real-world, prospective, psychometric validation study is underway to evaluate the psychometric properties of the PREMII for clinical application. Specifically, we will evaluate inter- and intrarater reliability, construct validity, criterion (i.e. predictive) validity, sensitivity to change, and responder definition. Comorbidities, especially those that impact nutrition such as NEC, will be captured in the study, and outcomes will be categorized. Additionally, the psychometric validation study will further explore the scoring of the PREMII and evaluate the optimal frequency of administration of PREMII in real-world clinical practice. The PREMII is designed for use from shortly after birth through discharge from the NICU; longer term validation (e.g. at 2 years of age) is challenging owing to variation in clinical practice and patient attrition over time.

In conclusion, the PREMII represents a ClinRO measure with well-supported content validity and usability to assess the functional status of extremely preterm infants serially over time in the NICU. It is hoped this unique tool will be suitable for use in neonatal clinical studies.

Statement of ethics

The authors have no ethical conflicts to disclose. Ethical approval was not required by the institutional review board because the study did not involve direct patient involvement or personal health information.

Ward_PREMII_Appendix.pdf

Download PDF (254.3 KB)Ward_PREMII_Supplementary_Material_20Feb2020.docx

Download MS Word (430.7 KB)Acknowledgments

Under direction of the authors, Rosalind Bonomally, MSc, of Excel Medical Affairs provided writing assistance for this publication. Editorial assistance in formatting, proofreading, and copyediting was provided by Excel Scientific Solutions. Shire, a member of the Takeda group of companies, provided funding to Excel Medical Affairs for support in writing and editing this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

Robert M. Ward, Mark A. Turner, Ingrid Hansen-Pupp, and Jason Higginson were paid consultants to Takeda in connection with this study (Mark A. Turner’s payment was received by his institution). Ingrid Hansen-Pupp also owns stock/stock options in Premalux AB. Magdalena Vanya, Emuella Flood, Ethan J. Schwartz, and Helen A. Doll are, or were, employees of ICON, who were paid consultants to Takeda in connection with this study. Adina Tocoian was an employee of Takeda at the time of the study. Alexandra Mangili, Norman Barton, and Sujata P. Sarta are employees of and own stock/stock options in Takeda. Robert M. Ward, Mark A. Turner, Ingrid Hansen-Pupp, and Jason Higginson participated as clinical experts in the clinical expert interviews.

Data availability statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its supplementary information files.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, et al. Trends in care practices, morbidity, and mortality of extremely preterm neonates, 1993–2012. JAMA. 2015;314(10):1039–1051.

- World Health Organization. Preterm birth: fact sheet n°363 2014. [cited 2017 Nov 16]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs363/en/.

- Blencowe H, Cousens S, Chou D, et al. Born too soon: the global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reprod Health. 2013;10(Suppl 1):S2.

- Moore T, Hennessy EM, Myles J, et al. Neurological and developmental outcome in extremely preterm children born in England in 1995 and 2006: the EPICure studies. BMJ. 2012;345:e7961.

- Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, et al. Neonatal outcomes of extremely preterm infants from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):443–456.

- Kuban KCK, Allred EN, O’Shea M, et al. An algorithm for identifying and classifying cerebral palsy in young children. J Pediatr. 2008;153(4):466–472.

- Ancel P-Y, Goffinet F, Kuhn P, et al. Survival and morbidity of preterm children born at 22 through 34 weeks’ gestation in France in 2011: results of the EPIPAGE-2 cohort study. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(3):230–238.

- Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Hospital discharge of the high-risk neonate. Pediatrics. 2008;122(5):1119–1126.

- Altman M, Vanpée M, Cnattingius S, et al. Moderately preterm infants and determinants of length of hospital stay. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2009;94(6):F414–F418.

- Richardson DK, Gray JE, McCormick MC, et al. Score for Neonatal Acute Physiology: a physiologic severity index for neonatal intensive care. Pediatrics. 1993;91(3):617–623.

- Richardson DK, Corcoran JD, Escobar GJ, et al. SNAP-II and SNAPPE-II: simplified newborn illness severity and mortality risk scores. J Pediatr. 2001;138(1):92–100.

- The International Neonatal Network. The CRIB (clinical risk index for babies) score: a tool for assessing initial neonatal risk and comparing performance of neonatal intensive care units. Lancet. 1993;342(8865):193–198.

- Parry G, Tucker J, Tarnow-Mordi W. CRIB II: an update of the clinical risk index for babies score. Lancet. 2003;361(9371):1789–1791.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims 2009; [cited 2017 Oct 3]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/77832/download.

- von der Gracht HA. Consensus measurement in Delphi studies. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2012;79(8):1525–1536.

- Barone G, Corsello M, Papacci P, et al. Feasibility of transferring intensive cared preterm infants from incubator to open crib at 1600 grams. Ital J Pediatr. 2014;40:41.

- Bender GJ, Koestler D, Ombao H, et al. Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: predictive models for length of stay. J Perinatol. 2013;33(2):147–153.

- Eichenwald EC, Blackwell M, Lloyd JS, et al. Inter-neonatal intensive care unit variation in discharge timing: influence of apnea and feeding management. Pediatrics. 2001;108(4):928–933.

- Gaal BJ, Blatz S, Dix J, et al. Discharge planning utilizing the discharge train: improved communication with families. Adv Neonatal Care. 2008;8(1):42–55.

- Hintz SR, Bann CM, Ambalavanan N, et al. Predicting time to hospital discharge for extremely preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):e146–e154.

- Jeremic A, Tan K. Predicting the length of stay for neonates using heart-rate Markov models. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2008;2008:2912–2915.

- Lee HC, Bennett MV, Schulman J, et al. Accounting for variation in length of NICU stay for extremely low birth weight infants. J Perinatol. 2013;33(11):872–876.

- Manktelow B, Draper ES, Field C, et al. Estimates of length of neonatal stay for very premature babies in the UK. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2010;95(4):F288–F292.

- Merritt TA, Pillers D, Prows SL. Early NICU discharge of very low birth weight infants: a critical review and analysis. Semin Neonatol. 2003;8(2):95–115.

- Picone S, Paolillo P, Franco F, et al. The appropriateness of early discharge of very low birth weight newborns. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24(supp 1):138–143.

- Seki K, Iwasaki S, An H, et al. Early discharge from a neonatal intensive care unit and rates of readmission. Pediatr Int. 2011;53(1):7–12.

- Temple MW, Lehmann CU, Fabbri D. Predicting discharge dates from the NICU using progress note data. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):e395–e405.

- Ye G, Jiang Z, Lu S, et al. Premature infants born after preterm premature rupture of membranes with 24–34 weeks of gestation: a study of factors influencing length of neonatal intensive care unit stay. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24(7):960–965.

- Berry MA, Shah PS, Brouillette RT, et al. Predictors of mortality and length of stay for neonates admitted to children’s hospital neonatal intensive care units. J Perinatol. 2008;28(4):297–302.

- Nankervis CA, Martin EM, Crane ML, et al. Implementation of a multidisciplinary guideline-driven approach to the care of the extremely premature infant improved hospital outcomes. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99(2):188–193.

- McGrath JM, Braescu AV. State of the science: feeding readiness in the preterm infant. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2004;18(4):353–368. quiz 369–370.

- Altman M, Vanpée M, Bendito A, et al. Shorter hospital stay for moderately preterm infants. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95(10):1228–1233.

- Cotten CM, Oh W, McDonald S, et al. . Prolonged hospital stay for extremely premature infants: risk factors, center differences, and the impact of mortality on selecting a best-performing center. J Perinatol. 2005;25(10):650–655.

- Robison M, Pirak C, Morrell C. Multidisciplinary discharge assessment of the medically and socially high-risk infant. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2000;13(4):67–86.

- Jefferies AL, Canadian Paediatric Society, Fetus and Newborn Committee. Going home: facilitating discharge of the preterm infant. Paediatr Child Health. 2014;19(1):31–42.