ABSTRACT

Calls continue for the decolonisation of higher education (HE). Based on internationalisation debates, a research team from Africa, Europe and Latin America reviewed published decolonisation voices. Using bibliometric analysis and a conceptual review of abstracts, the authors examined the drivers framing decolonisation in HE and identified the voices in those debates which involved the historically oppressed and those wishing to elicit change in these debates. The paper recognises the importance for decolonisation in education as the tensions explored by the authors often intersect through HE into other domains of the political, social, economic and culturally important areas for replication and change in society.

‘To centre otherness is to accept that no single voice speaks for us all’

Carol Azumah Dennis Citation2018

Introduction

The debate around decolonisation in Higher Education (HE) is topical and sometimes controversial (wa Thiong’o, Citation1994; Smith, Citation2013) engaging authors of different disciplines and driving a multi-layered discourse involving many stakeholders around the world. Furthermore, the concept of decolonisation has different meanings to different people in differing contexts, with dimensions that encapsulate political, economic, cultural, material and epistemic dimensions (Maldonado-Torres Citation2011). Others, such as Ibañez & Sandoval (Citation2015,103), view colonisation, particularly in education as ‘having multiple characterisations’. The political, philosophical and cultural dimensions of the term mean that it is enacted in many disciplines and teaching–learning spaces and most significantly belies a moral responsibility which the authors argue educators and learners are not always aware of.

The rationale for this article is rooted in a discussion about internationalisation between European, Latin American and African researchers around different understandings of decolonisation that took place in January 2020. This debate involved 2 different groups – one historically oppressed segment and the other that does not experience coloniality but wants to engage with the challenges. There are many other stakeholders in this discourse too – institutions, students, employers, etc. The Education field is undoubtedly the major arena for the debate on decolonisation, because the tension expressed here intersects through HE into the political, social, economic and cultural domains. The concerns about the role of curriculum, and the strategic place that the decolonisation debate has in HE are important for both theoretical and practical reasons.

Motivated by this conversation, the researchers have sought to explore contemporary discourse of decolonisation and its implications for understanding, teaching, internationalising and researching HE. We decided to write a series of papers articulating this conversation, with the present one focusing on identifying the demographics and geographic distribution of the authors in the area and how these criteria shape the debate, exploring the geographic provenance, representative focus and chronology of published articles.

This paper is an invitation to examine radical perspectives on how the discourse of decolonisation centres and how authors navigate the space.

Positioning

Firstly, we need to define our field of research. As a polysemic term,

Decolonisation can be broadly understood as an umbrella term for diverse efforts to resist the distinct but intertwined processes of colonisation and racialisation, to enact transformation and redress in reference to the historical and ongoing effects of these processes, and to create and keep alive modes of knowing, being, and relating that these processes seek to eradicate. (Stein & Andreotti Citation2016, 978–981)

Secondly, we have to engage with the obvious political, cultural and social enactments of decolonisation (Mbembe Citation2016; Carr & Thésée Citation2017) as well as the epistemic dimensions and practices that influence us all (Ferguson Citation2012; Zwane Citation2019; Andreotti et al. Citation2015). There is now widespread acknowledgement that colonisation and coloniality have a significant impact on HE practice and systems (Smith Citation2013; wa Thiong'o Citation1994; Mignolo Citation2012). Tensions remain around what to do about this as well as contending with the ‘guilt’ and politics (Johnson Citation2012; Fataar Citation2018), notions of white fragility (DiAngelo Citation2018) and powerlessness. These deeply embedded HE assemblages lead some to think that the best perhaps easiest option is to ‘move on and carry on’, because the complexities of addressing the damage of colonialty may upend the roots framings of knowleledge production in unhelpful ways. Many others believe resisting epistemic violence associated with colonisation, and more so coloniality, have a social justice element which cannot simply be ignored (Le Grange Citation2016; Ahmed Citation2000). The former is advocated by scholars from both former colonies and former colonisers (de Beer and Petersen Citation2016; Santos Citation2017), who argue that structural damage is so profound and colonised practices and norms, such as common language, laws and monetary systems so entrenched that countries, which experienced colonisation, find it less contentious adapting to the colonised mechanisms and circumstances (Heleta Citation2016; Richardson Citation2018; Vandeyar Citation2020). Some even argue that colonisation had its merits (sic) and recipients should be ‘grateful’, as did Gilley’s controversial ‘Case for Colonialism paper (we refuse here to dignify it with a citation – please see Taylor Citation2018; Oleksy Citation2018), for some context on the case of this paper and critical responses. This shows how overtly colonial arguments are still legitmated in academia and more widely to the point of achieving the dignity of publication and policy discourse, and consequently this area needs on-going scrutiny and critical self-examination.

This paper favours the social justice framing with respect to decolonisation, which requires ethical action to address on-going and persistent forms of coloniality in order to probe the construction of cognitive injustice across education systems, theories and processes (Santos Citation2014). This stance is typically recognised by the majority in HE (Fataar Citation2018) as the discourse integrated a strong emphasis on the cognitive dissonance of knowledge seeking and production which stifles delegitimised epistemologies from the formerly colonised internationalisation (Heleta Citation2016; de Wit Citation2018). However, a number of critics (Pashby and Andreotti Citation2016; Clifford and Montgomery Citation2017; de Wit Citation2018) demonstrate how internationalisation rather than supporting decolonisation actually perpetuates coloniality. A more transformative agenda (Zwane Citation2019) is called for, which authentically decentres (Angu Citation2018; Dennis Citation2018; Mwangi et al. Citation2018) the hegemony of western, Eurocentric epistemologies and creates a more robust multiplicity of knowledges.

Furthermore, there are more radical voices (Walton Citation2018) calling for the dismantling of subtle forms of coloniality, which do not transform practice, content or pedagogies; knowledge exchange which reinforces coloniality of being (Maldonado-Torres Citation2007) and research support which privileges those with power within former colonising countries (Vandeyar Citation2020).

Concerns and caveats

We acknowledge the difficulty of language from a disciplinary perspective, which silos and restricts our understanding and also as a cultural challenge that distorts meaning and sense making (Spolander, Garcia and Penalva Citation2016). The challenge of understanding, sense making, contextualisation and critiquing is complicated by our shorthand use of common words such as ‘colonisation’, ‘decolonisation’, ‘internationalisation’, ‘capitalist’ and so forth. Such words have taken on multilayered meaning with profound symbolic gestures which need to be explained and reexamined.

For example, Knight and de Wit (Citation2018) discuss the contested nature of the word internationalisation:

Who could have forecasted that internationalisation would transform from what has been traditionally considered a process based on values of cooperation, partnership, exchange, mutual benefits and capacity building to one that is increasingly characterised by competition, commercialisation, self-interest and status building?

In the complex mechanisms of political and economic influence on HE, leading to commercialisation and massification of the academy, such transformations have shifted the meaning of concepts.

Our location here reveals our relationships with the term and assemblages of colonialisation in itself an act of decolonisation (Denis Citation2018). Consideration must, therefore, be given to the arguments of critics such as Santos (Citation2014) that we consider epistemologies of the colonised, which have often been delegitimised through what he is called ‘epistemicide’. Moving away from the safety of an unmarked stance (Denis Citation2018), we use the epistemological dialogue of indigeneity to engage our political and cultural relationships with the terms we are using. We also appropriate decolonial discursive practices by acknowledging the multiplicity of ideas we have come across in our learning journeys (Madden Citation2014) and how these have framed our understanding of the terms. As such we recognise that decolonisation is often situated by many authors (Andreotti Citation2011; Mignolo Citation2012) at the nexus of neoliberalism, social justice, power, coloniality, inequality and the need for change.

Methodology

The study uses publications to interrogate the thematic discourse around decolonisation in Higher Education. The period of consideration was 1985–2020, covering the most recent generation since European colonial era began to wane in the 1960s. The articles are a useful and reliable means of examining how the publications have significantly expanded over the last 5 years and the themes that frame the development of the discourse in academic circles. Considering the pluralistic nature of decolonial writing, we acknowledge that a lot of rich data are available in non-academic publications, which our current study doesn’t capture. The research has focused on academic discourse which links to the co-production, validation and legitimisation of knowledge in Higher Education, as well as teaching and learning principles and associated pedagogy. Bibliometric analysis (Waltman and van Eck Citation2012) is used to examine the drivers behind the framing of decolonisation in HE. The metrics and terminology in this study have broad meaning and varied interpretation; accordingly, this paper focuses on the voices of the authors. This analysis leaves out the citation and supposed reach or impact of the articles. The bibliometric data informed a conceptual review of abstracts (Huberman and Miles Citation2002; Kennedy Citation2007). There are various bibliometric approaches (Bornmann and Marx Citation2013) that allow for the rich analysis of published material. Our bibliometric approach focused on author, institution publisher and abstract analysis, as well as keyword co-occurrence analysis.

Furthermore, the study uses a conceptual review to critically organise articles aligned to concepts or themes (Kennedy Citation2007), providing a narrative of the current understanding and examining how different perspectives may be justified. Conceptual reviews provide a critical snapshot of a topic or phenomena without interrogating detail as in meta analysis or systematic reviews. In this article we examine the discourse of decolonisation in HE from the assemblage of authors involved; the vignette explores the characterisations evident in the debate and patterns and embodiments displayed by the kinds of writers engaged in the topic.

Research question for this study:

Whose voices shape the discourse of decolonisation? Where are they geographically located and why does this matter?

The study was carried out in five distinct steps:

Step 1: Framing questions for the review

Step 2: Identifying relevant work

Step 3: Assessing the quality of studies

Step 4: Biblometric analysis of authors, keywords, journal publishers, etc.

Step 5: Analysing the themes

Framing questions for the review: This is essential to delineating the scope and boundaries of a study. There are many discourses around decolonisation, including political, economic, sociocultural and epistemological discourses. This review focuses on a specific, clear, unambiguous and structured question (Huberman and Miles Citation2002) around decolonisation discourse in HE. When the investigation began, it became apparent that the term decolonisation was widely used in the HE sector, thus slight modifications were made to the protocol, in order to precisely define the conceptualisation of decolonisation in HE. The boolean string was a combination of decolonisation and HE.

The study focuses on the research question above. Further study has been undertaken using discourse analysis to provide a systematic review of the data. The study does not include terminology related to the decolonisation discourse such as indigenousation, although we recognise the overlap of these discourses along with the importance in their differences and pluralism, likewise the shared economic and material basis of coloniality. The study focuses on English language publications only.

Identifying relevant work: The search for studies relating to the topic was extensive. Multiple resources were used to ensure a broad cross-section of relevant work was integrated. The selection criterion was strictly aligned with the review questions a priori. Explicit reasons for inclusion and exclusion were noted and justified. SCOPUS was used to capture all relevant work; this was triangulated with searches from EBSCO in England. Other databases returned too many irrelevant data because ‘decolonisation’ in medicine referred to populations receiving treatment for infections caused by bacterial colonies.

Assessing the quality of studies, the papers were carefully assessed for quality in line with the following criteria:

Robust methodology

Original study

Peer-reviewed publication

The biblometric analysis used statistical methods to categorise authors, institutions, publishers and key themes. First, a biblometric tabulation of the themes was undertaken for overall characteristics and quality; this included thematic categories, similarities, contexts and prominent differences. Simple statistical methods were used to provide the categorisations.

Interpreting the findings – The researchers examined the themes emerging from the data. Six researchers participated in the process. Analysis of content utilised central tendency measures (Bardin Citation1977) to demonstrate the key words used in the abstracts. The process captured 166 references. Ten of them were discarded, as irrelevant to the research question. The remaining 156 were triangulated with searches from EBSCO; however, this database did not present any relevant papers about our theme. The final list included 134 papers and 22 book chapters. The 22 book chapters were excluded, as inclusion criteria focused on peer-reviewed journal papers, these represented 80.7% of our Scopus list. Those 134 papers have been published in 96 different journals. The abstracts were read and relevant papers about decolonisation were selected.

The variables chosen that provided a reasonable and accessible profile of the authors were gender, geographical location of author, journal and year of publication.

Results and discussion

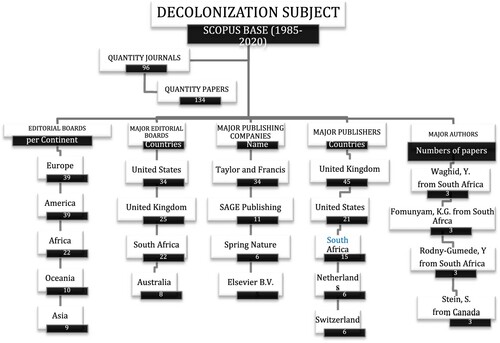

The bibliometric analysis showed the publications with respect to continent and country (where institution is located) of author, publisher and geographical headquarters of journal ().

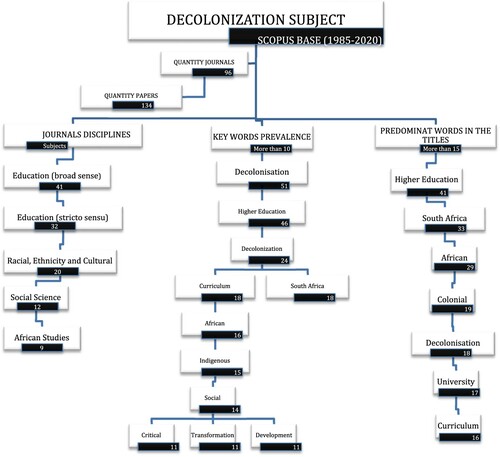

The analysis also revealed the area of education the articles focused on and key words in the abstract and titles ().

The findings were grouped into six (6) major themes which are discussed below.

Grassroots movements

#FeesMustFall appeared as Africa/African issues in this field. The students’ movement in South Africa started in 2015–2016, regarding the perceived slow pace of transformation within institutions of higher learning (Luescher, Loader and Mugume Citation2017; Heleta Citation2016). According to Jansen (Citation2019, p. 1), ‘the student protests starting in 2015 added a new term to the lexicon of South African universities: decolonisation’. It is clear, adds the author, the term decolonisation has been historically referred to anti-colonial struggles since the 1950s to signal continued efforts to find liberation from the legacy of colonialism. As Jansen argues, this is not a simple, negative process of ‘undoing’, as (1) historical processes can’t simply be ‘undone’ and (2) a simple subtractive approach might disrupt opportunities to appropriate and adapt elements of that legacy (e.g. existing infrastructure) towards liberatory processes.

Still, ‘[…] literally overnight, the word decolonisation rolled off the lips of activities, bannered everyday protests and initiated across mainly the formerly white campuses seminars, conferences and committees to determine meanings and methods for changing universities - their complexions, cultures and curricula’. This student’s movement in South Africa was important to raise several publications starting in 2016, as shown in Graphic 1.

See Graphic 1: Decolonisation plus High Education: publication by year

Majority of voices located in former colonies

There is a predominance of authors who publish from countries that were colonised. 52% of the authors come from institutions located on the African continent. These, in addition to authors from Asia and Oceania institutions, represent 65% of the total (Graphic 2). Although it cannot be said that the origin of the authors proves a critical perspective on colonisation, there is considerable volume of this debate in the colonised continents.

Of the 134 papers analysed, the authors are predominantly from South Africa (47.4%), followed by the United States (12.4%) and thirdly the United Kingdom (8.3%). But, in our field of inquiry linked to journals, the first paper from South Africa was published only in 2009, with the debate intensifying after 2015 (when the #feesmustfall movement started) (Fourie-Malherbe and Muller Citation2020).

See Graphic 2. Decolonisation authors per continent

See Graphic 3. Authors Institutions

Gender

Of all authors, 51% are women. If we look per each country, we see 54% of women authors in SA. Idahosa (Citation2019) that suggests the necessity for decolonised gender studies. We would like to highlight two issues: the gender oppression and the field that the authors are researching characterised per social reproduction in capitalist dynamic. It is, therefore, relevant that many of the publications touch on themes of intersectionality, particularly in a discipline such as education, which, while still perceived as strongly gendered, suffers from the same disproportions in its professoriate and international career pathways – say something about demographics (Kwiek and Roszka Citation2020). Also, as Manion and Sahal (Citation2019) highlight that ‘the very theme of decolonising research and practice in feminist education research locates this issues within a nexus of debates concerning how knowledge is produced, by who, on what topics, and for what purposes(s)’.

Of the 96 journals that published articles on decolonisation, 41 focus on the education area (30.6%). Of these, six focus on the Higher Education debate; three incorporate the ethnic–racial issue and gender issue. In addition to these areas, journals are linked to areas, such as Engineering (Technology), Health, Law, Arts, Linguistics, Theology, Information Sciences, Communication, etc.

Publishing journals

Among the journals that published the most papers on the theme Decolonisation, we have eight that published four articles each (Teaching in Higher Education, South African Journal of Psychology, South African Journal of Education, Perspectives in Education, International Journal of African Renaissance Studies, HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies, Education as Change, Higher Education Research and Development). Of these, five are strictly Education publications. The other three journals with four articles published on the topic are in the areas of Theology, Psychology and Studies on Africa Renaissance. The next tranche, publishing three articles apiece, are also Education editorials with one exception in the field of Geography. There are a total of five in this category.

Of the 13 journals that published the most on the topic (with four or three articles published) nine are major Education editorials, contributing 44 articles out of a total of 134 published in the Scopus database.

Although our research on SCOPUS has been based on the key words – Decolonisation and Higher Education – the theme Decolonisation has been widely connected with educational discussions. According to Stein and Andreotti (Citation2016, 978–981), decolonisation and education, especially Higher Education are a subject of significant interest in both social movements and scholarly critique across the globe due to ‘the central role of universities in social reproduction, and in the creation and legitimation of knowledge’.

However, our analysis reveals that the chief editors and significant number of the editorial team are largely based in former colonising countries. As such, the debate around the theme of colonisation expresses a reality that is not harmonious. Of the 96 journals, 45 are British and 21 are North American. The inclusion of six Dutch and six Swiss makes a total of 78, equivalent to 81.25% of the total of journals. The editorial staff of the journals also follows the same trend: of the 96, 59 have North American and British editors (61.45%). When we consider the Scopus list of active journals (2019), 48% of 25,185 journals are based in the UK and USA, respectively. In Scimago database, the result is 55% of the journals are UK and the USA. It means the prevalence of journals in this index databases published is in mainstream science, and the peripheral science is less visible for an international audience (Velho Citation1985; Almeida and Gracio Citation2018).

From an international perspective, the tension between different understandings and approaches to decolonisation and decoloniality is linked to the different perspectives and dimensions through which the phenomenon is experienced. This is the result of the not only colonisation process, but also the structure and mechanisms that react to and oppose the different ways coloniality expresses itself, depending on the specific context and histories. Moreover, decolonisation as a term is open to varying types of analysis, because at times it implies a theme that cannot be ignored in countries with a colonising past; this allows its meaning to become polysemic. Higher education as a system is seeking to shape the debate around decolonisation, thus other stakeholders and actors such as the state and groups in society are obliged to contend with the power of governments and their relationships with its agents.

Content

The locus of debate here centred on transformative learning experiences, mirroring the 7 elements in Carr and Thésée (Citation2017): pedagogy, lived experiences, curriculum, leadership, educational policy, epistemology and institutional culture.

The importance of this debate, regarding decolonisation and curricula, can be confirmed by 26 articles which discuss this area of knowledge and field of studies (corresponding to 19.4% of all articles). From the total, 20 present ‘curriculum’ as one of the keywords, and the other six present this field of studies in the title, but not in the keywords. The form and content of the curricula are at the heart of the dispute and it is very interesting to note the growth, in the second decade of this century, of this debate in South Africa. The curriculum is a strategic vehicle to affirm the actuality of this oppression process, or, on the other hand, to appease and reduce it to a mere schematism and the absence of alternative pedagogies.

The concept of curriculum discussed by the papers is related to curriculum reform based on the notion of Ubuntu-Currere (Hlatshwayo and Shawa Citation2020); the inclusion of Indigenous knowledges as an essential movement for the decolonisation of higher education institutions (Harvey and Russel-Mundine Citation2019); the deconstruction rather than the decolonisation of the neocolonial curriculum (McGregor and Park Citation2018). It argues for an inclusive curriculum, examination of genres of power and double consciousness to decolonise higher education (Janks Citation2019); and an imbizo approach (where questions are answered; concerns are heard and advice is taken) for the integration of African traditional health knowledge and practices into existing nursing curricula (Moeta et al. Citation2019). In addition, there is an emphasis on the implications of decolonisation for the Economics Teaching and Business Studies Teaching (EBST) curriculum (disciplinary/content knowledge) with the inclusion of African perspectives and the integration of economic and business history in the curriculum (America and Le Grange Citation2019). This includes students’ perspectives about decolonising the curriculum, but not advocating for the eradication of Western knowledge in the curriculum, but rather for decentring it (Meda Citation2020). Other ideas include, reconceptualisation of the undergraduate and postgraduate international law curricula (Nienaber Citation2018) and Africanising of curricula (Ally and August Citation2018).

The papers also discuss curriculum related to the impact of neoliberal agendas on curriculum through a postcolonial and decolonising lens (Gyamera and Burke Citation2018); issues of decolonisation and transformation of geography curricula at different universities in South Africa (Knight Citation2018); exploration of curriculum linked to decolonisation, social justice and agency (Angu Citation2018). Examination of the global education market demonstrates how HE builds new hierarchies of knowledge production that reverse prior decolonisation achievement, re-westernise higher education and stifle the criticality essential for political and social reform (Hall Citation2018). Decolonising educationalist education is embedded in a critical approach that aims to create counter hegemonic intellectual spaces which could support a change of praxis (Sathorar and Geduld Citation2018). Furthermore, authors such as Fomunyam and Teferra (Citation2017) support the notion that specific curriculum encounters offer a vital opportunity for the analysis of effectiveness and curriculum responsiveness in the decolonisation process. Others, including Chaka, Lephalala and Ngesi (Citation2018), propose that deparochialism and null curriculum concepts should be examined during decolonisation to ensure that it parochialises the English studies discipline. The decolonised education system is also seen a key process in denouncing repressive tendencies through curriculum decolonisation movements (Mutekwe Citation2017). This has enabled constructs of decolonisation and re-inhabitation to promote collective empowerment of the rural communities among the youth (Huffling, Carlone and Benavides Citation2017), ensuring the prominence of efforts to improve the decolonisation of university structures and cultures (Vorster and Quinn Citation2017). Luckett (Citation2016) argues that this provides a contestation of curriculum control, focusing particularly on decolonisation of Humanities and Social Sciences to include an African epistemic in the HE curricula (Higgs Citation2016). In South Africa, in particular, examination of how to validate indigenous African knowledge systems with equal legitimisation with respect to ways of knowing among the array of knowledge systems in the world is thoroughly articulated. Furthermore, the significance of archives in the decolonisation process of HE curricula in South Africa (Saurombe Citation2018), along with the conceptualisation of the Writing Lab’s participation in new forms of knowledge building, contributes to the creation of decolonised spaces and shifts in institutional culture (Muna et al. Citation2019).

The decolonisation, as applied to university curriculum, is a dispute about a ‘knowledge project’ (Jansen Citation2019). Reflecting about the curriculum as a field of dispute takes us to Apple (Citation2019), a critical theorist, for whom the curriculum is not a neutral and disinterested field of knowledge, but rather a mechanism of power: a mechanism of power with regard to which critical questions need to be asked. Why are some important and not others? Whose knowledge are they? What are the power relationships involved in the selection process that resulted in this curriculum? The authors in our study address these in many ways, focusing on the political and social entanglements of colonisation, coloniality and decolonisation. This also centres on knowledge production and power. As Jansen (Citation2019, 2) argues: ‘Who produces knowledge? What knowledge is produced and what knowledge is ‘left out’ are central questions of inquiry within the politics of knowledge’.

Most of the articles address how the transformation and decolonisation of higher education involve the issue of curriculum reform presenting proposals relating to a new concept of curriculum, for instance, as Ubuntu-Currere, to respond to context, democratic difference and cosmopolitan perspectives (Hlatshwayo and Shawa Citation2020). The prioritisation of theory and practice sensitive to the context is also essential to disrupt Western epistemic domination (Harvey and Russel-Mundine Citation2019) and some papers discuss curriculum decolonisation linked to social justice and agency in order to explore matrices of power, culture and knowledge (Angu Citation2018). Some papers present the curriculum renewal process happening in the university to disrupt various forms of oppression that are manifest in the composition of a colonised higher education in South Africa. The idea of plurality of voices is essential to provoke the creation of disciplinary and interdisciplinary spaces for curriculum engagement and sustainable education experience (Fomunyam and Teferra Citation2017). However, the discussion towards curriculum decolonisation in higher education is related only to some disciplinary field or only as a module thematic or topical component in a discipline, for instance, restricted to African literature or Africa writings (Chaka, Lephalala and Ngesi Citation2018).

The Western research training has made much progress in recent decades (Datta Citation2018). Stein and Andreotti (Citation2016) state the increasingly debate of decolonisation in HE is associated with the central role of universities in social reproduction, and in the creation and legitimation of knowledge.

Language/use of context

Analysing the key words, we identified that the highlighted: (Education – 87; Decolonizing/decolonization/decolonisation – 76; Higher – 45; South – 21; African – 20; indigenous – 19; Curriculum – 20). In the key words, we identified the word decolonisation was written using z and s, expressing the difference between American English (Decolonization) or British English (Decolonisation). Indigenous words (like Ubuntu, imbizo, uMakhulu) and native/indigenous issues appeared in the title, inviting us to use words that meanings put us facing questions as: Ubuntu (a quality that includes the essential human virtues; compassion and humanity).

Scopus prioritises the English language we identified authors from countries where English is not an official language i.e. Brazil (Portuguese), 4 from Italy, 5 from China and 1 from France.

Final thoughts and conclusion

Our explorations of the literature showed that the centre of debate is in the colonised continents, where the countries at the periphery of global capitalism are located. As an actual and relevant theme, the issue has been drawing attention of academics due to the challenges of twenty-first-century capitalism, particularly the deep crisis of inequality and power perpetuated by cycles of coloniality which are exacerbated at the periphery.

Exploring the literature, it became rapidly evident that any discussion around ‘decolonisation’ inevitably includes a conversation about its opposite – ‘colonisation’; – and both express a complex process imbricated within society as a whole, and in a vast plurality of forms (Dennis Citation2018). In addition to this dialectic – decolonisation and colonisation – the literature highlighted the relevance of the term coloniality, coined by Quijano (Citation1997) –defined as something that transcends the particularities of historical colonialism and that does not disappear with independence or decolonisation. Coloniality, being ‘the continuity of colonial forms of domination after the end of colonial administrations, produced by colonial cultures and structures in the modern/colonial capitalist/patriarchal world-system’ (Grosfoguel Citation2007, 219). Other broadly cited authors in the examined papers, for instance, Maldonado-Torres (Citation2007), view coloniality as a system which shapes how epistemic, material and aesthetic resources reproduce modernity’s colonial project through its organisation and dissemination of materials. As a result, discussions around decoloniality involve the on-going efforts to challenge coloniality, while the discourse of decolonisation has its roots in efforts during the colonial era that challenged imperialism by colonising countries (Mignolo Citation2011; Zembylas Citation2018).

Analysing the literature, it also became rapidly apparent that the majority of the authors and institutions are located in the African continent. In particular, the most recent wave of publications (2015 onwards) reflects an historical process emerging from key social movements like #FeesMustFall and #RhodesMustFall. These social movements started contesting the equality of access to HE together with the rising cost of fees in higher education, both having a major social justice component.

Moving beyond the centrality in the current literature of the above-mentioned South African political initiatives, it’s important to also highlight the plurality of various movements and struggles against coloniality; these are often not coherent or unanimous in scope, breadth or rational. The range of diverse views and voices is reasonably linked with the multiplicity populations, experiences and languages involved. Accordingly, the specific terminologies of decolonisation are pluralistic (and, it is important to highlight, sidestep what is often perceived to be a subtractive nature of decolonial discourse – leaving open a question as to what would occupy the void – see Jansen Citation2019).

These movements and demands adopted instead contextualised affirmative expressions of the struggle against coloniality, using plural labels that are reflective of local conditions and specific demands, such as indigeneity (Paradies Citation2006), indigenous rights and land rights (Xanthaki Citation2007), anti-imperialism (Gobat Citation2013), race and equality (Hutcheson et al. Citation2011), negritude (Wilder Citation2015).

While there is a definite overlap between many of these discourses, it’s also exceedingly important to highlight their differences and their pluralism, so as to not simplistically lump them together. Furthermore, it’s also necessary to understand the shared economic and material basis of coloniality, shaped by extractivism (Maldonado-Torres Citation2016), another recurring shared theme of the examined literature.

For this reason, it’s important to acknowledge how colonisation has an economic foundation that is maintained through the re-composition of this dependent relationship successively as a form of capitalism development, that is, uneven and combined (Lenin Citation2009; Leher and Vittoriao Citation2015). Education and, more generally, knowledge production (including research) play a pivotal role in this replication, highlighting the importance of this debate. With the discourse of decolonisation coming to the fore in this area, we have chosen to research this particular terminology, while acknowledging that it doesn’t provide full coverage of the above-mentioned struggles.

The formal research in Social and Human Science that is following this renewed wave of activism is still struggling to understand and question the realities of coloniality by asking why and what is ‘the best way to know’. Moving from and linking activism into academic discourse, the literature we explore points at a refutation of the idea that the only legitimate way of knowing is Euro-centric science, as expressed in one language and one geo-political perspective – the natively English-speaking core of the capitalism.

Following this insight, future studies will be oriented at more fully examining the plural trends and directions of the existing literature, and identifying gaps for both research and activism.

Limitations

The restrictions inherent in the database used present a number of limitations. Scopus is a database that concentrates on English journals. The results should explore other database in Spanish and Portuguese (for example). The search was performed in the United Kingdom, search engines can vary depending on where you are in the world. English is the predominant language of many journals, but African schools might also prefer to publish in indigenous languages for impact and to resist coloniality?

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) under Capes Print Grant [number 88881.311890/2018-01] and The British Council Capacity Building & Internationalisation for HE - Universities for the World Programme - Shaping global urban environments for today and tomorrow: Internationalisation of researcher development and doctoral provision in strategic Social Sciences research areas through a Brazil/UK collaboration.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahmed, S. 2000. Strange Encounters: Embodied Others in Post-Coloniality. New York and Abingdon: Routledge.

- Ally, Y., and J. August. 2018. “#Sciencemustfall and Africanising the Curriculum: Findings from an Online Interaction.” South African Journal of Psychology 48 (3): 351–359. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246318794829.

- Almeida, C. C. D., and M. C. Cabrini Grácio. 2018. “Citation of Articles in Journals of Information Science: an Analysis of Distribution in the Scopus Database.” XVIII Encontro Nacional de Pesquisa em Ciência da Informação –ENANCIB 2017.

- America, C., and L. Le Grange. 2019. “Decolonising the curriculum: Contextualising Economics and Business Studies Teaching.” Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe Jaargang 59 No. 1: Maart 2019. doi:https://doi.org/10.17159/2224-7912/2019/v59n1a7.

- Andreotti, V. 2011. “(Towards) Decoloniality and Diversality in Global Citizenship Education.” Globalisation, Societies and Education 9 (3–4): 381–397. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2011.605323.

- Andreotti, V. D. O., S. Stein, C. Ahenakew, and D. Hunt. 2015. “Mapping Interpretations of Decolonization in the Context of Higher Education.” Decolonization: Indigeneity Education & Society 4 (1): 21–40.

- Angu, P. 2018. “Disrupting Western Epistemic Hegemony in South African Universities: Curriculum Decolonisation, Social Justice, and Agency in Post-Apartheid South Africa.” The International Journal of Learner Diversity and Identities 25 (1–2). doi:https://doi.org/10.18848/2327-0128/CGP/v25i01/9-22.

- Apple, M. V. 2019. Ideology and Curriculum. New York and London: Routledge.

- Bardin, L. 1977. L'Analyse de Contenu. Paris: PUF.

- Bornmann, L., and W. Marx. 2013. “The Proposal of a Broadening of Perspective in Evaluative Bibliometrics By Complementing the Times Cited with A Cited Reference Analysis.” Journal of Informetrics 7 (1): 84–88. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2012.09.003.

- Carr, P. R., and G. Thésée. 2017. “Seeking Democracy Inside, and Outside, of Education: Re-conceptualizing Perceptions and Experiences Related to Democracy and Education.” Democracy and Education 25 (2), Article 4. Available at: https://democracyeducationjournal.org/home/vol25/iss2/4.

- Chaka, C., M. Lephalala, and N. Ngesi. 2018. “English Studies: Decolonisation, Deparochialising Knowledge and the Null Curriculum.” Perspectives in Education 35 (2): 208–229. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18820/2519593X/pie.v35i2.16.

- Clifford, V., and C. Montgomery. 2017. “Designing an Internationationalised Curriculum for Higher Education: Embracing the Local and the Global Citizen.” Higher Education Research & Development 36 (6): 1138–1151. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1296413.

- Datta, R. 2018. “Decolonizing both Researcher and Research and its Effectiveness in Indigenous Research.” Journal of Drug Education 14 (2): 81–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2190/DE.43.1.f. Accessed 11 September 2020.

- de Beer, J., and N. Petersen. 2016. “Decolonisation of the Science Curriculum: A Different Perspective (#Cookbook-Labs-Must-Fall).” Proceedings from ISTE international Conference on Mathematics, science and Technology education. towards Effective Teaching and Meaningful learning in Mathematics, science and Technology, UNISA, Pretoria, RSA. Retrieved from http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/22869/Josef%20de%20Be er%2c%20Neal%20Petersen.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y Accessed 11 September 2020.

- Dennis, C. A. 2018. “Decolonising Education: A Pedagogic Intervention.” In Decolonising the University, edited by G. K. Bhambra, K. Nişancioğlu, and D. Gebrial, 190–207. London: Pluto Press.

- de Wit, H. 2018. “The Bologna Process and the Wider World of Higher Education: The Cooperation Competition Paradox in a Period of Increased Nationalism.” In European Higher Education Area: The Impact of Past and Future Policies, edited by A. Curaj, L. Deca and R. Pricopie, 15–22. Berlin: Springer. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77407-7_2

- DiAngelo, R. 2018. White Fragility: Why It's so Hard for White People to Talk About Racism. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Fataar, A. 2018. “Editorial Decolonising Education in South Africa: Perspectives and Debates.” Educational Research for Social Change (ERSC) 7 (June 2018): vi–ix. ersc.nmmu.ac.za ISSN: 2221-4070.

- Ferguson, R. A. 2012. The Reorder of Things: The University and its Pedagogies of Minority Difference. Minneapolis, MN: Minneapolis University of Minnesota Press.

- Fomunyam, K. G., and D. Teferra. 2017. “Curriculum Responsiveness Within the Context of Decolonisation in South African Higher Education.” Perspectives in Education 35 (2): 196–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.18820/2519593X/pie.v35i2.15.

- Fourie-Malherbe, M., and A. Müller. 2020. “Student Protests and Higher Education Transformation: A South African Case Study.” In Universities as Political Institutions, 165–188. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill Sense.

- Gobat, M. 2013. “The Invention of Latin America: A Transnational History of Anti-Imperialism, Democracy, and Race.” The American Historical Review 118 (5): 1345–1375.

- Grosfoguel, R. 2007. “The Epistemic Decolonial Turn: Beyond Political-Economy Paradigms.” Cultural Studies 21 (2-3): 211–223.

- Gyamera, G. O., and P. J. Burke. 2018. “Neoliberalism and Curriculum in Higher Education: a Post-Colonial Analyses.” Teaching in Higher Education 23 (2): 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1414782.

- Hall, P. 2018. “The Global Education Market, Criticality, and the University Curriculum in the Overseas Campuses of Qatar and the United Arab Emirates.” International Journal of Critical Pedagogy 9 (1): 73–94.

- Harvey, A., and G. Russell-Mundine. 2019. “Decolonising the Curriculum: Using Graduate Qualities to Embed Indigenous Knowledges at the Academic Cultural Interface.” Teaching in Higher Education 24 (6): 789–808. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1508131.

- Heleta, S. 2016. “Decolonisation of Higher Education: Dismantling Epistemic Violence and Eurocentrism in South Africa.” Transformation in Higher Education 1 (1): a9. doi:https://doi.org/10.4102/the.v1i1.9.

- Higgs, P. 2016. “The African Renaissance and the Transformation of the Higher Education Curriculum in South Africa.” Africa Education Review 13 (1): 87–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2016.1186370.

- Hlatshwayo, M. N., and L. B. Shawa. 2020. “Towards a Critical re-Conceptualization of the Purpose of Higher Education: the Role of Ubuntu-Currere in Reimagining Teaching and Learning in South African Higher Education.” Higher Education Research & Development 39 (1): 26–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1670146.

- Huberman, M., and M. Miles. 2002. The Qualitative Researcher’s Companion. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Huffling, L. D., H. B. Carlone, and A. Benavides. 2017. “All Things Being Equal, Equality and Diversity in Careers Education, Information, Advice and Guidance.” Cultural Studies of Science Education 12: 33–43.

- Hutchinson, J., H. Rolfe, N. Moore, S. Bysshe, and K. Bentley. 2011. All Things Being Equal, Equality and Diversity in Careers Education, Information, Advice and Guidance. Manchester: Equality and Human Rights Commission.

- Ibañez, M., and G. Sandoval. 2015. “Reflections on Decolonization: an Alternative to the Traditional Classroom.” Enletawa Journal 8 (2): 103–123.

- Idahosa, G., O. Yacob-Haliso, and T. Falola. 2019. “Decolonizing the Curriculum on African Women and Gender Studies.” In The Palgrave Handbook of African Women’s Studies, edited by O. Yacob-Haliso and T. Falol, 1–18. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77030-7. Accessed 10 September 2020.

- Janks, H. 2019. “Decolonization of Higher Education in South Africa: Luke's Writing as Gift.” Curriculum Inquiry 49 (2): 230–241. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2019.1591922.

- Jansen, J. D. 2019. “Making Sense of Decolonisation in Universities.” In Decolonisation in Universities: the Politics of Knowledge, edited by J. D. Jansen, 1–12. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

- Johnson, R. 2012. “Justice and the Colonial Collision: Reflections on Stories of Intercultural Encounter in Law, Literature, Culture and Film.” Literature, Culture and Film 2012 (9): 68–96.

- Kennedy, M. M. 2007. “Defining a Literature.” Educational Researcher 36: 139–147. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X0729919710.3102/0013189X07299197.

- Knight, J. 2018. “Decolonizing and Transforming the Geography Undergraduate Curriculum in South Africa.” South African Geographical Journal 100 (3): 271–290. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03736245.2018.1449009.

- Knight, J., and H. De Wit. 2018. “Internationalization of Higher Education: Past and Future.” International Higher Education 95: 2–4.

- Kwiek, M., and W. Roszka. 2020. Gender Disparities in International Research Collaboration: A Large-Scale Bibliometric Study of 25,000 University Professors. Preprint available https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.00537. Accessed 09 September 2020.

- Le Grange, L. 2016. “Decolonising the University Curriculum: Leading Article.” South African Journal of Higher Education 30 (2): 1–12.

- Leher, R., and P. Vittoria. 2015. “Social Movements and Critical Pedagogy in Brazil: From the Origins of Popular Education to the Proposal of a Permanent Forum.” The Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies 13: 145–162, University of Northampton: School of Education, 2015.

- Lenin, V. I. 2009. The Development of Capitalism in Russia. Collected Works. Volume 3. Moscow: Progress Publishers. Digital Reprints.

- Luckett, K. 2016. “Curriculum Contestation in a Post-Colonial Context: a View from the South.” Teaching in Higher Education 21 (4): 415–428. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2016.1155547.

- Luescher, T., L. Loader, and T. Mugume. 2017. “# FeesMustFall: An Internet-age Student Movement in South Africa and the Case of the University of the Free State.” Politikon 44 (2): 231–245.

- Madden, B. 2014. “Coming Full Circle: White, Euro-Canadian Teachers’ Positioning, Understanding, Doing, Honouring, and Knowing in School-Based Aboriginal Education.” In Education 20 (1): 57–81.

- Maldonado-Torres, N. 2007. “On the Coloniality of Being: Contributions to the Development of a Concept.” Cultural Studies 21 (2-3): 240–270.

- Maldonado-Torres, N. 2011. “Thinking Through the Decolonial Turn: Post-Continental Interventions in Theory, Philosophy, and Critique — An Introduction.” Transmodernity: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World 1 (2).

- Maldonado-Torres, N. 2016. “Transdisciplinaridade e Decolonialidade.” Sociedade e Estado 31 (1): 75–97.

- Manion, C., and P. Shah. 2019. “Decolonizing Gender and Education Research: Unsettling and Recasting Feminist Knowledges, Power and Research Practices.” Gender and Education 31 (4): 445–451. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2019.1596392.

- Mbembe, A. J. 2016. “Decolonizing the University: New Directions.” Arts and Humanities in Higher Education 15 (1): 29–45.

- McGregor, R., and M. S. Park. 2018. Towards a deconstructed curriculum: rethinking higher education in the Global North, Teaching in Higher Education Special Issue: Experts, knowledge and criticality in the age of ‘alternative facts’: re-examining the contribution of higher education 24(3): 332-345.

- Meda, L. 2020. “Decolonising the Curriculum: Students’ Perspectives.” Journal Africa Education Review 17 (2): 88–103.

- Mignolo, W. 2011. The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Mignolo, W. 2012. Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges and Border Thinking. Princeton: Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/s0395264900039287. Accessed 1 September 2020.

- Moeta, M., R. S. Mogale, S. E. Mgolozeli, M. M. Moagi, V. Pema-Bhana, et al. 2019. “Integrating African Traditional Health Knowledge and Practices into Health Sciences Curricula in Higher Education: An Imbizo Approach.” International Journal of African Renaissance Studies – Multi,-Inter,-and Transdisciplinarity 14 (1): 67–82. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/18186874.2019.1635505.

- Muna, N., T. G. Hoosen, K. Moxley, and E. van Pletzen. 2019. “Establishing a Health Sciences Writing Centre in the Changing Landscape of South African Higher Education.” Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning 7 (1): 19–40.

- Mutekwe, E. 2017. “Unmasking the Ramifications of the Fees-Must-Fall-Conundrum in Higher Education Institutions in South Africa: A Critical Perspective.” Perspectives in Education 35 (2): 142–154.

- Mwangi, C. G., S. Latafat, S. Hammond, S. Kommers, S. Hanni, J. Berger, and G. Blanco-Ramirez. 2018. “Criticality in International Higher Education Research: a Critical Discourse Analysis of Higher Education Journals.” Higher Education 76: 1091–1107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0259-9.

- Nienaber, A. 2018. “Boundaries of the Episteme: Decolonising the International Law Curriculum.” Scrutiny2 23 (2-3): 20–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/18125441.2019.1621925.

- Oleksy, E. M. 2018. “A Critique of Bruce Gilley's” The Case for Colonialism.” The Downtown Review 5 (2): 3. https://protect-us.mimecast.com/s/q5RGC2kExEckWQ21inQ1NY?domain=engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu

- Paradies, Y. C. 2006. “Beyond Black and White: Essentialism, Hybridity and Indigeneity.” Journal of Sociology 42 (4): 355–367.

- Pashby, K., and V. Andreotti. 2016. “Ethical Internationalisation in Higher Education: Interfaces with International Development and Sustainability.” Environmental Education Research 22 (6): 771–787. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.1201789.

- Quijano, A. 1997. “Colonialidad del Poder, Cultura y Conocimiento en América Latina.” In Anuário Mariateguiano. Lima: Amatua. v. 9, n. 9: 117–131.

- Richardson, W. R. 2018. “Understanding Eurocentrism as a Structural Problem of Undone Science.” In Ed Decolonising the University, edited by G. K. Bhambra, K. Gebrial, and K. Nişancıoğlu, 231–248. London: Pluto Press.

- Santos, B. D. S. 2014. Epistemologies of the South. Justice against Epistemicide. Boulder/ London: Paradigm Publishers.

- Santos, B. D. S. 2017. Decolonizing the University: The Challenge of Deep Cognitive Justice. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars.

- Sathorar, H., and D. Geduld. 2018. “Towards Decolonising Teacher Education: Reimagining the Relationship Between Theory and Praxis.” South African Journal of Education 38 (4): 1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v38n4a1714.

- Saurombe, N. 2018. “Decolonising Higher Education Curricula in South Africa: Factoring In Archives Through Public Programming Initiatives.” Archival Science 18: 119–141. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-018-9289-4.

- Smith, L. T. 2013. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Zed Books Ltd.

- Spolander, G., M. L. T. Garcia, and C. Penalva. 2016. “Reflections and Challenges of International Social Work Research.” Critical and Radical Social Work 4 (2): 169–183. doi:https://doi.org/10.1332/204986016X14651166264273.

- Stein, S., and V. D. O. Andreotti. 2016. “Decolonization and Higher Education.” In Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory, edited by M. Peters. Singapore: Springer Science Business Media. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-532-7_479-1.

- Taylor, J. S. 2018. “The Case Against the Case for Colonialism.” International Journal of Applied Philosophy 32 (1): 19–32.

- Vandeyar, S. 2020. “Why Decolonising the South African University Curriculum Will Fail.” Teaching in Higher Education 25 (7): 783–796. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2019.1592149.

- Velho, M. L. 1985. “Como Medir a Ciência? Revista Brasileira de Tecnologia.” Brasília 16 (1): 35–41.

- Vorster, J.-A., and L. Quinn. 2017. “The “Decolonial Turn”: What Does it Mean for Academic Staff Development?” Education as Change 21 (1): 31–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2017/853.

- Waltman, L., and N. J. van Eck. 2012. “A new Methodology for Constructing a Publication-Level Classification System of Science.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 63 (12): 2378–2392. http://arxiv.org/abs/1203.0532.

- Walton, E. 2018. “Decolonising (Through) Inclusive Education?” Educational Research for Social Change (ERSC) 7 (Special Issue June): 31–44. ersc.nmmu.ac.za ISSN: 2221-4070.

- wa Thiong'o, N. 1994. Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. Oxford: James Currey Ltd.

- Wilder, G. 2015. Freedom Time: Negritude, Decolonization, and the Future of the World. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

- Xanthaki, A. 2007. Indigenous Rights and United Nations Standards: Self-determination, Culture and Land. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Zembylas, M. 2018. “Affect, Race, and White Discomfort in Schooling: Decolonial Strategies for ‘Pedagogies of Discomfort.” Ethics and Education 13 (1): 86–104.

- Zwane, D. 2019. “True Versus False Transformation: A Discussion of the Obstacles to Authentic Decolonisation at South African Universities.” International Journal of African Renaissance Studies – Multi-, Inter- and Transdisciplinarity 14 (1): 27–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/18186874.2019.1625713.