ABSTRACT

This paper explores the experiences of transnational women educators, who lead in education institutions in globally imbricated home and host schooling contexts, focusing on how they negotiate glass ceilings and borders in their work and their life choices. The purpose is to extend scholarship on women in educational leadership, which is often framed as a binary of national and international scales, thereby omitting large numbers of educators who work and exist transnationally. Women continue to represent a large portion of the education profession globally, whose roots and routes criss-cross over national borders defining them in the process as transnational. Yet there remains a dearth of research addressing their experiences as transnational women educators, and in educational leadership positions in particular. This study uses narratives of transnational women to explore the professional life and personal reflections of six women who have worked across diverse school leadership roles. The findings of the study highlight the simultaneity of women’s lives and leadership practice across borders, and indicates scope for further research to move beyond binarised understandings of space.

Introduction

Education systems in most countries, especially at the level of schooling, are dominated by women’s labour. The assumption that follows is that these women are largely nationals, with deep roots in national cultures, and strong national identities. Whilst this might reflect a large percentage of women in any country, there is also a significant number who are explicitly or implicitly transnational, either working in international schools, moving backward and forward across national borders as a result of roots in several locations, following career trajectories that take in a number of countries, or simply have multiple ethnicities as a result of family biographies. Transnational women educators live and work across borders and boundaries of national education systems, and specifically in this study as women leaders in schools, enabling a mobility of leadership practice across globalising contexts. Yet enquiring into their roots and routes, and the implications of this transnationality for understanding their experiences and practices as educators more generally, and leaders in particular, is less well explored.

This paper aims to tell the story of transnational women educators as leaders living and working here and there, sharing experiences of roots and routes (Gilroy Citation1993; Vertovec Citation1999). Against the backdrop of globalisation, this exploratory case study considers the following research question:

• How do transnational women, as educators and individuals, experience simultaneity in their practice of educational leadership as they move across borders?

Discussion of the extant literature on globalisation and transnationalism provides a context for the work of women, drawing on metaphors of obstructions like glass ceilings and borders, and the implied fragility and risk of such metaphors in globalised settings. This leads to the conceptual framework, which marries the seminal ideas of women’s practice in educational leadership (Grogan and Shakeshaft Citation2011) with the social field theory of transnationalism, and its distinguishing moment and movement between being and belonging as transnationals (Levitt and Schiller Citation2004). The research design of the case study is discussed, detailing the participants in the case study, and outlining the reflexive thematic analysis used to generate findings. The six women in this case study are referred to using pseudonyms, and direct quotes from semi-structured interviews support the key themes of the findings. In the discussion, key themes are identified which remain consistent with some of the previously established ways in which women leaders express purpose in educational settings. However, findings also articulate new considerations which add to the literature; of adventure and resistance to fragile positions that women embrace as pathways to defining their own sense of being and belonging.

Globalisation and transnationalism in education

In this section, I provide a broader context which now shapes education as a sector, education institutions, and educators as actors. I begin by observing that education has continued to evolve within the larger socio-economic and cultural patterns of globalisation (Sum Citation2019; Sum Citation2021; Spring Citation2008). As the ideology of education as a pathway to economic development has gained traction, nations have aspired to increasingly global agendas (Michelsen and Wells Citation2017; UNESCO Citation2015). Global policy has led to increased pressures on national systems, and in some cases, limited government investment has motivated and nurtured the input of non-state actors and their involvement in education (Sum Citation2022; Steer et al. Citation2015). Increasingly, the gap in provision has led to entrepreneurial ventures into the private school sector (Sum Citation2021). The proliferation of such ventures in low- and middle-income countries, and models such as elite schools with international campuses, have fed a dynamic market of educational mobility (Ball Citation2012). This mobility, of educational philosophy, practice and people, across evolving and porous models of systems has created transnational educators yet to be fully explored and considered in extant literature on educational leadership.

Furthermore, globalised policies and opportunities have led to the privileging of certain forms of transnationalism in education. Transnational definitions are often related to commercial enterprise or migratory ideas. For multi-national corporations, transnationalism seeks to encapsulate processes, operations and delivery across national boundaries. This idea is replicated in the Higher Education (HE) sector, keen to meet student demand in distant geographies. Accordingly, transnational education (TNE) has been defined as all learning opportunities and programmes which involve learners in a country different from the provider institution (UNESCO/Council of Europe Citation2000). Over the previous decade, we have witnessed a rapid exporting of such education programmes from Western nations into developing economies (Adick Citation2018). Much of the discourse on TNE remains tied to the model of the institute as in its country of origin, here, with education commodified for delivery in host nations, there. While some consideration has been given to the HE experiences of educators involved in the delivery of TNE, the focus has remained on the nature of the exported programme from one country to another (Adick Citation2018). The lens is largely nationalistic, even while we are witness to the international mobilities implied in the practice of educators, or as Gilroy captured in the idea of being rooted at the expense of ignoring routes (Gilroy Citation1993).

In this regard, the application of transnationalism in the field of migratory studies has been more expansive. Schiller, Basch, and Blanc-Szanton (Citation1992) recognised that ‘to conceptualize transnationalism we must bring to the study of migration a global perspective’ (19). In later work, Levitt and Schiller (Citation2004) call for a broader analytical lens in order to understand ‘migrants are often embedded in multi-layers, multi-sited transnational social fields’ (1003) and the simultaneity of lives lived both here and there. This approach to transnationalism seeks to challenge the concept of society as a construct of tight national boundaries that frames and contains education activity and the labour of educators. As Levitt and Schiller (Citation2004) also note, ‘assimilation and enduring transnational ties are not incompatible’ (1003) because ‘the nation-state container view of society does not capture, adequately or automatically, the complex interconnectedness of contemporary reality’ (1006). This study seeks to address the relationship between these ideas of globalisation, transnationalism and the work of women educators, with a particular focus on their roles and experiences in educational leadership across borders.

Women in leadership, fragile metaphors and framing the study

Whilst globalisation has expanded many commercial opportunities, the wider literature has established the ongoing lag in opportunities for women to step into leadership roles (Adler Citation2007; Brunner and Grogan Citation2005; Coleman Citation1996; Citation2010). Regardless of whether this is in relation to expatriate postings (Vance and Paik Citation2001; Werhane Citation2007), domestic educational settings (Arar and Oplatka Citation2016; Blackmore Citation2008), or specifically in education leadership (Moreau, Osgood, and Halsall Citation2007; Shakeshaft Citation1989; Vella Citation2022), the gap persists. The theme, of women in educational leadership, has generated special issues in academic journals focused on a global perspective of practice from different nations (Sherman Citation2010), and as a larger conversation on the development of identity (Murakami and Törnsen Citation2017). Most recently, Martínez, Molina-López, and Mateos de Cabo (Citation2021) identified that while over two-thirds of educators are female, women represent the minority of principal class. The notion of supply and demand in a profession that is weighted towards women, harks back to Coleman’s (Citation1996) original argument that gender stereotypes exist as long as representation of women remains limited. We have come to identify such challenges of opportunity and appointment as the glass ceiling into senior roles for women (Werhane Citation2007). The step into leadership for women is exacerbated by defining women’s transition into leadership as transparent but bounded, through visible but seemingly unattainable glass ceilings (Coleman Citation2010), across glass walls (Cubillo and Brown Citation2003) or on the edge of glass cliffs (Peterson Citation2016). These many glass metaphors reflect what Martínez, Molina-López, and Mateos de Cabo (Citation2021) refer to as the demand-side perspective or ‘structures and practices in education [that] overtly or subtly discriminate against women in the selection for leadership positions’ (865). It marks the vulnerability of women who step up to lead against structural fragilities that are not guaranteed to support. Studies have identified, that women are likely to internalise the lower numbers of female leaders as the lack of necessary skills, and expertise, amongst women to secure leadership roles (Moreau, Osgood, and Halsall Citation2007), or what may be interpreted as the supply-side approach (Martínez, Molina-López, and Mateos de Cabo Citation2021).

These metaphors, applied to women educators are simultaneously constrictive and dangerous. The fragility of glass seems to indicate a tipping point of risk. Women take on leadership with seemingly greater inherent risk. Research has focused on localised experiences of women in educational leadership roles, by districts or countries, and often at the intersection of race and culture (Arar and Oplatka Citation2016; Blackmore Citation2008; Brunner and Grogan Citation2005). Yet as argued in the opening of this paper, this does not account for the work of women in educational leadership positions across nation-state borders. In a globalising world, we need to understand the constructs of transnationalism and its relationship to education through the stories of such women who lead, and whose leadership work takes them across national borders whilst at the same time framed by fragile metaphors of glass walls, ceilings and cliffs. This study seeks to extend the consideration of women in educational leadership by addressing the context beyond nation-state experiences. The narratives informing this paper differ in that the women continue to live and work transnationally, stepping in and out of leadership roles as their work continues to shift and evolve. They are transnational educational leaders, and their practice exists here and there. Their stories introduce us to the ways in which women enact their choices to work and live transnationally – beyond glass borders – and asks us to consider that our ideas of education, and those who lead it, as contained and compared to other container nation states, may not be sufficient to reflect the diversity of work and choices being made by women educators.

To explore these issues, I combine the framing of women’s practice in educational leadership with a social field perspective of transnationalism as a conceptual framework for exploring the experiences of the women leaders who continue to work across borders. Grogan and Shakeshaft (Citation2011) provide five core dimensions of leadership as evidenced in the work of women. These are identified as:

• Relational leadership which refers to the practices that seek to accomplish goals through and with others rather than relying on hierarchical notions of power.

• Leadership for learning that focuses on implementing and championing initiatives for learning improvements, staff development, innovation and creative instructional approaches.

• Leadership for social justice that is driven by a sense of purpose in choosing to be in the field of education to challenge the inequity and improve the lives of children.

• Spiritual leadership recognising that women draw strength and resilience from their sense of an interconnected life, modelling and inspiring others to be agents of change.

• Balanced leadership reflecting the inspiration of strong female role models, often mothers, that influence women’s practice of securing their home obligations in order to be able to balance their work responsibilities.

These dimensions of women’s practice of leadership reflect the need for a purpose grounded in pupil outcomes, and secured through organisational improvement. Leithwood (Citation2007) defines this as leadership constituted of direction and influence. In the practice of women’s leadership, Grogan and Shakeshaft’s (Citation2011) model highlights social justice as directional to influencing those within schooling communities to work in more collaborative ways towards improving children’s opportunities. These practices are considered for the ways in which transnationalism is evident in the work and lives of the women leading education in this study, and whose stories are elaborated below. Levitt and Schiller (Citation2004) ‘propose a view of society and social membership based on a concept of social field that distinguishes between ways of being and ways of belonging’ (1008). A social field approach to transnationalism provides a means to consider the ‘set of multiple interlocking networks of social relationships through which ideas, practices and resources are equally exchanged, organised and transformed’ (Levitt and Schiller Citation2004, 1009). Applying a social field perspective to transnationalism also brings transparency to the ways in which individuals may or may not belong, highlighting the nuances in their sense of embeddedness as they relocate to work here and there, and possibly back to here or another there beyond. Social fields include various levels of institutions and experiences which an individual may be embedded in, yet choose not to identify with, resulting in being part of something but not belonging. Alternatively, belonging ‘refers to the practices that signal or enact an identity which demonstrates a conscious connection … not symbolic but concrete, visible actions’ (Levitt and Schiller Citation2004, 1010). The intersection of women’s leadership and the ways of being and belonging provide the framework for this exploration of narratives shared by women.

Research methods

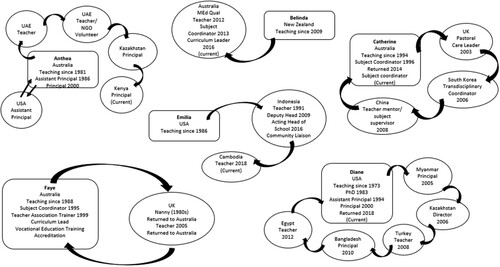

As a qualitative study of transnational women who have worked, and continue to work, in educational leadership across a range of roles and contexts both at home and away, the study recognises that leadership is not the sole remit of titleholders, such as principals or vice-principals. Rather that leadership is that process of influence which is present in many aspects of school work (Blackmore Citation2008). This includes roles such as school principals, assistant principals, alongside the leadership practice of curriculum or programme coordinators, and teacher mentors to newly qualified teachers. Underscored by Grogan and Shakeshaft’s (Citation2011) model discussed in the preceding section, women’s leadership in schools is the practice of seeking to transform educational opportunities for children through collaborative and socially just ways. Participants were purposively sampled to identify women who sustain their work in education leadership across nation-state borders. Initial invitations led to a snowball sampling through the informal network of women, resulting in six women sharing their stories and time for this study. Narrative inquiry was used to explore participants stories of being and belonging transnationally. Data collection began with the CVs of each participant and an online survey with open-ended questions. These initial data were used in collaboration with each participant to co-construct the narratives of their work experiences to date. captures a visual profile of each participant’s transnational experiences expressed through their CVs and in their narratives. It demonstrates the diversity of these work and life choices for the women in the study. In the example of Belinda, the move from here (New Zealand) to there (Australia) appears one way, but her narrative maintains this as a current and not permanent state. By contrast, Anthea’s mapping reflects her narrative that the nature of work she is currently engaged in is not available in the Australian context and she has no plans to return. This is different again from Faye’s transnational experience, which has seen her work in the UK (Scotland and England) and Australia at various times across her professional journey.

Through this relational work of narrative construction, participants were able to express the cultural, social and institutional stories of their experiences (Clandinin and Rosiek Citation2019), recognising that each woman leads a storied life and tells their story in turn (Connelly and Clandinin Citation1990). Furthermore, Clandinin (Citation2006) reminds us that narrative inquiry is a three-dimensional space of sociality, temporality and place, that ‘allows the possibility for understanding how the personal and social are entwined over time in their [participants’] lives’ (51). Co-constructing the narrative of here and there, provided participants with a temporally organised story to which they found they had more to add. These further contributions became semi-structured interviews where each woman narrated their views of leadership, experiences along their work life, challenges and opportunities of being and belonging across glass walls. All data from the interviews was transcribed and added to the analysis of narratives (Polkinghorne Citation1995). Paradigmatic analysis follows the reflexive thematic approach, as developed in the work of Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) and Clarke and Braun (Citation2013). Reflexive thematic analysis begins with data immersion for familiarisation and theory informed coding. Using the framework of women in leadership and transnational ways of being and belonging, data was coded to map and generate meaning in response to the research question. The preceding three steps are iterative and require further review of data for accuracy and coherence, before the story can be told with detailed consideration (Clarke and Braun Citation2013). Through this reflexive approach to thematic analysis, the five themes generated hold across the experiences shared and reflect the story of the data set. The findings and discussion presented below explore these key themes, with direct quotes from the participants’ narratives.

Findings and discussion

In distinguishing the practice of women in leadership, Grogan and Shakeshaft (Citation2011) captured the passion of women choosing to lead being for the purposes of change rather than as a means of attaining power. The findings here are consistent with these approaches of relational practice, leading for learning, leading for social justice, spiritual leadership, and balanced leadership. However, the findings illustrate key elements of practice across borders. Simultaneity of being and belonging through these transnational expressions of life and work were also evident.

Journey, growth and self-accountability

Strong relational aspects of leadership practice were evident in their journeys of personal and professional growth across borders, and in the ways in which the participants appeared to hold themselves accountable to others. Participants identified both personal development and professional growth in stepping into leadership roles (Moreau, Osgood, and Halsall Citation2007). Personal growth was reflected in the opportunities to question self, seek help and build self-efficacy. Young and McLeod (Citation2001) identified similar factors in the decision making of women to become administrators. For the transnational women in this study, across borders, these factors were often mirrored in professional confidence to know how to bring people together to work towards resolving challenges in schools. Anthea shared this rite of passage to confidence in her approach to leadership:

I am very much a people person and I’ve had the experiences which has affirmed to me that whilst when I first became a leader … you questioned how you should do things, how should you manage people, what should you say not say, be yourself, not be yourself. I guess I’m at the stage now where I’m really, really enjoying being who I am, having the experiences I’ve had to be at a point where I can be exactly who I am, the person I want to be in education – professionally and personally. (Anthea)

you have to have a really good picture of where you want to go and how you’re going to get there, but you need to have other people involved in your process as well to get you there.

rather than the big ideas, with everyday leadership if you’re not reflecting the good values of how you want students to be thought of and treated, or how you want other people to treat their jobs … I guess I think about that. (Belinda)

Lifelong learning and disposition to change

The drive to work in education was captured in narratives that expressed a philosophy and need to model lifelong learning, which in turn supported a disposition to adapt and thrive in change. Anthea expressed the philosophy ‘as someone who has always been a learner, somebody that wants to try experiences. I want to learn new things’. Seeking to learn new things at times led the women to arrive at destinations, ready to immerse in the adventure of the unknown, without shying away from the challenge. This came through in several instances, one of which is shared here from Belinda:

Probably should do more research [laugh] more research than I did. I mean I was awful … I landed in Australia and I found out when I went to a social studies conference that Australia doesn’t have a national curriculum [laugh]. It didn’t occur to me that you wouldn’t have the same curriculum over the same country. It was foreign, it was very difficult to come from a federal system and you don’t understand. (Belinda)

always go in with the experience of learning more. Yes, you’re partaking and giving knowledge away, but you also should be learning … learning from the institution, learning from other teachers because there’s a lot to learn.

no matter where you go in the world you’re still teaching and you’re still promoting education, but sometimes that’s done in a different way. The more you observe different situations the easier it is to fit into the situations. And also seeing needs. (Catherine)

Centring students in this way, through needs and learning, is recognised as core to women’s leadership in education and the ways in which they represent their values (Grogan and Shakeshaft Citation2011; Murakami and Törnsen Citation2017). Adaptability to new contexts, while retaining a core philosophy of lifelong learning, might well be viewed as contributing to the quality of relational leadership discussed earlier. However, it also appeared to serve as key strategic approach to being able to sustain a focus on learning and constructing leadership practice around this focus. It is consistent with the ways that extant literature has developed ideas of women in leadership, while illustrating how these transnational women have continued to make impactful change on diverse learning communities.

Gendered experiences of here and there

The response to the question of whether gender mattered in their work resulted in seemingly glib answers. However, as the narratives unfolded, it became apparent that gendered experiences impacted recruitment and selection, their relationships with school boards/owners, and expectations within the community. Some of these aspects are well considered in scholarship on women’s journey to school leadership in different districts in the US, and across individual country-based studies (Arar and Oplatka Citation2016; Brunner and Grogan Citation2005; Moreau, Osgood, and Halsall Citation2007; Murakami and Törnsen Citation2017). In the discussion of leading for learning, and reflections of being in classrooms and other collegial spaces, the narratives of these transnational women reinforce some of these patterns. For example, women constitute the greater majority of human resources across the profession (Brunner and Grogan Citation2005; Cubillo and Brown Citation2003; Shakeshaft Citation1989). Belinda identified that in her experiences, students were equally aware of this. She explained that the tendency of principals to be male influenced priorities because ‘I think their agenda impacts their leadership style … it was very kind of a very male leadership around’. Furthermore, when working in international spaces, Belinda reflected that socio-cultural influences impacted the ways in which some male students might approach female educators. An example of this experience and the follow-on with colleagues is reflected through this vignette:

I think occasionally I would have boys from some Middle Eastern cultures who would kind of be more persistent in an argument they had with me, than perhaps they would with a male. But I mean I’ve also had someone [colleague] argue with me that no it’s not the case, it’s because you were young, it’s not because you were female. (Belinda)

When I was a Special Ed teacher, I ran into some women who were administrators in my home town school district. They always said to me, oh you’re so talented, and I wondered “well, how did they get to be a principal or an administrator?”, because no local women were promoted. (Diane reflecting on her early experiences here in USA)

I think there’s definitely a discrimination in favour of men, and in a lot of times incompetent, personally not very mature men. That’s an overlay of a culture that sees white males as a source of income and security, and they could be from Britain, they could be from the US or Australia. (Diane sharing her experiences of securing a role there in South-East Asia)

because I was a woman they were already questioning the fact that I could do that. I think it’s very much … you can be a leader in primary school but you could never be a leader of the whole school. Pre-school or ELC that’s more the section that I think men or the community looks at as women can do that better. It was very difficult for me. (Emilia)

I think we women have to be strong in ourselves … and say no, I’m not going to be stepped over. What I have and what my opinion is, and what my qualities and what I want to say is important, and whilst you may not want to do it that way that’s fine, but you need to listen. We need to feel comfortable and confident enough to express what we need to say. (Anthea)

Advocating for teachers and students

Scholarship speaks to the ways in which women lead for social justice. This is characterised by practices that focus on institutional change, and driven by prioritising improvements in the lives of children (Grogan and Shakeshaft Citation2011). This study showed the practice for social justice framed in explicit efforts to advocate for teachers, and engagement in broader community-based challenges. Across borders, there was a consistent focus on supporting the professional learning of teachers. This was illustrated in narratives from principals and deputy principals such as Anthea and Diane. Sometimes, the task of teacher development was made more difficult by the fact that leaders ‘had inherited the staff that was hired by someone else, and none of them had had international experience’ (Diane). Other times, tensions arose from the resistance amongst parents and some teachers because ‘when you try to bring in standards for the teaching staff, parents were worried and so were some of the teachers that you were going to rock the boat too much’ (Diane). Diane spoke of her approach to professional learning by funding collaborative training experiences with other schools in the area. Anthea shared a different approach, where the school provided teacher training. The teachers who completed the training could be recruited by the school directly, or supported to work other schools in the region.

Beyond advocating for professional learning opportunities, especially in contexts of developing economies, the educators in this study were keenly aware of the privilege of being an international appointment. In such instances, the salary of the principal was considerably different from the salary of a locally appointed teacher. To this end, several noted that they worked with the school owners to continue to address the economic conditions of local staff. They championed additional funding for resources, salary reviews or engaged in dialogue with school owners to address conditions. When efforts to redress conditions went unheard, positions became untenable and the women made difficult and frustrating choices to leave. Anthea expressed this sense of injustice as:

the challenge there was more personal because I was watching different minority groups being treated really badly, and my value system is very strong so I couldn’t stay. (Anthea)

Beyond advocating for teachers, creating better opportunities for children, the women shared their commitment to support the broader community. Most often, these changes sought to improve local access to education, fund and set up community schools or challenge their own students to address social issues. For Catherine, one example was the work she led in developing the pastoral care model for students. She described it as ‘seeing a sort of a hole in the system and putting forward a plan … because the IB area was growing in the school and they had the curriculum side but they didn’t have the pastoral side’. Similarly, in Anthea’s most recent role, she described the way she worked with students in the school to address local challenges:

It’s about our students recognising that they are blessed, they are privileged in a lot of ways … not all but most. They have parents that work very hard and maybe they have a business, maybe they don’t. Maybe the parents are struggling as well, but to see what we can do that impacts on other children and other community and people makes their life a little bit better than what maybe they have. But it’s also about making it sustainable. (Anthea)

Being and belonging

The preceding findings point to the simultaneity across leadership work, and the ways in which this is intertwined with the personal choices of transnational women educators to be here or there, or here and not there. Levitt and Schiller (Citation2004) state that their social field perspective distinguishes between the ways of being and ways of belonging. In their relational practices of leadership amongst these women, the transnational lens showed that being was identified in the definitions of leadership. Consistently, this involved the leader to be an example, and be involved in action taken. In these descriptions and reflections of what it meant to be a leader, there was little sense of identity or connection. By contrast, working in schools where they experienced a sense of shared purpose with people, emotive language and exciting possibilities awoke. It spoke to the aspects of personal and professional growth that participants considered themselves to be journeying through, and indicated belonging was deeply rooted in the value placed on relational practice of working through and with people. Similarly, the simultaneity of leading learning was adaptable, with women being aware that practice did not always travel, transpose or settle comfortably for students and staff. This form of classroom acculturation provided examples of women in practice, but that the diversity of their own practice did not necessarily translate into belonging. Belonging in the leadership for learning was a more personalised and reflexive process of negotiating the role expectations of others with internal philosophies of lifelong learning, and knowing what, when and how to enact practice from the vast repertoire of experiences and expertise that these transnational women were travelling with. Furthermore, in leading for social justice, stepping into a range of contexts could be challenging but were not intimidating to the women. Instead, being in situations of cultural diversity, social and educational need and economic inequity, became opportunities that seem to beckon them on to leadership. Being in these schools and communities is initially the acting out of leadership, which perhaps is more reflective of the expectations of others. However, choosing to remain, identifying with the challenges and being able to implement strategies that address social injustice, are aligned with feeling a sense of belonging. Examples of gender-based prejudice and lack of willingness within the larger institution, become walls of lost opportunity. These walls instigate the call to mobility, with women continuing to relocate to other places to work. The key challenge of such mobility was the ways in which being transnational impacted their sense of belonging in family and close relationships.

Conclusions

Through the narratives of transnational women working in the globalised context of education, this study explored their perceptions of being here and there, and how this simultaneity manifested in their practice of educational leadership across borders. The metaphors of fragility identified in preceding scholarship sustain an imagery of risk. The transnational women educators in this study query this framing, and instead point to adventure, the sense of self-actualisation and dream fulfilment. This is an initial step to move our conversations of women in leadership beyond the fragile metaphors, to embrace the entirety of spirit, purpose, social justice and lifelong learning that is both the belonging of women in educational leadership, and the modelling for others to be. Social fields of schooling, colleagues, families and mentors are sustained across nation-state borders, but in that transnationalism, the women here have demonstrated the vision and determination to choose a pathway beyond contained and constrained policies and structures. The aim of this study was to enrich our considerations of how women continue to lead by considering that they have been building their own approaches to a transnational leadership practice which is both here and there. The women in this study do not appear to stare at glass ceilings or wait to be invited to perch on glass cliffs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adick, Christel. 2018. “Transnational Education in Schools, Universities, and Beyond: Definitions and Research Areas.” Transnational Social Review 8 (2): 124–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/21931674.2018.1463057.

- Adler, Nancy J. 2007. “One World: Women Leading and Managing Worldwide.” In Handbook on Women in Business and Management, edited by Diana Bilimoria and Sandy Kristin Piderit, 330–355. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- Arar, Khalid, and I. Izhar Oplatka. 2016. “Current Research on Arab Female Educational Leaders’ Career and Leadership.” In Challenges and Opportunities of Educational Leadership Research and Practice: The State of the Field and its Multiple Futures, edited by Bruce G. Barnett, Alan R. Shoho, and Alex J. Bowers, 87–115. Charlotte, USA: Information Age Publishing.

- Ball, S. J. 2012. Global Education Inc.: New Policy Networks and the Neoliberal Imaginary. London: Routledge.

- Blackmore, J. 2008. “Re/positioning Women in Educational Leadership: The Changing Social Relations and Politics of Gender in Australia.” In Women Leading Education across the Continents: Sharing the Spirit, Fanning the Flame, edited by Helen C. Sobehart, 73–83. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Education.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Brunner, C. Cryss, and Margaret Grogan. 2005. “Women Leading Systems: Latest Facts and Figures on Women and the Superintendency.” The School Administrator 62: 46–50.

- Clandinin, Jean D. 2006. “Narrative Inquiry: A Methodology for Studying Lived Experience.” Research Studies in Music Education 27 (1): 44–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X060270010301.

- Clandinin, Jean D., and Jerry Rosiek. 2019. “Borderland Spaces and Tensions.” In Journeys in Narrative Inquiry: The Selected Works of D. J. Clandinin, edited by D. Jean Clandinin. Milton: Taylor and Francis Group.

- Clarke, Victoria, and Virginia Braun. 2013. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Coleman, Marianne. 1996. “The Management Style of Female Headteachers.” Educational Management & Administration 24 (2): 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263211X96242005.

- Coleman, Isobel. 2010. “The Global Glass Ceiling: Why Empowering Women is Good for Business.” Foreign Affairs 89 (3): 13–21.

- Connelly, F. Michael, and D. Jean Clandinin. 1990. “Stories of Experience and Narrative Inquiry.” Educational Researcher 19 (5): 2–14. https://doi.org/10.2307/1176100.

- Cubillo, Leela, and Marie Brown. 2003. “Women into Educational Leadership and Management: International Differences?” Journal of Educational Administration 41 (3): 278–291. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230310474421.

- Gilroy, Paul. 1993. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. London: Verso.

- Grogan, Margaret, and Charol Shakeshaft. 2011. Women and Educational Leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Leithwood, Kenneth. 2007. “What We Know about Educational Leadership.” In Intelligent Leadership: Constructs for Thinking Education Leaders, edited by John M. Burger, Charles F. Webber, and Patricia Klinck, 41–66. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Levitt, Peggy, and Nina Glick Schiller. 2004. “Conceptualizing Simultaneity: A Transnational Social Field Perspective on Society.” International Migration Review 38 (3): 1002–1039. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2004.tb00227.x.

- Martínez, Miryam Martínez, Manuel M. Molina-López, and Ruth Mateos de Cabo. 2021. “Explaining the Gender Gap in School Principalship: A Tale of Two Sides.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 49 (6): 863–882. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143220918258.

- Michelsen, Gerd, and Peter J. Wells. 2017. A Decade of Progress on Education for Sustainable Development: Reflections from the UNESCO Chairs Programme. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

- Moreau, Marie-Pierre, Jayne Osgood, and Anna Halsall. 2007. “Making Sense of the Glass Ceiling in Schools: An Exploration of Women Teachers’ Discourses.” Gender and Education 19 (2): 237–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250601166092.

- Murakami, Elizabeth T., and Monika Törnsen. 2017. “Female Secondary School Principals: Equity in the Development of Professional Identities.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 45 (5): 806–824. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143217717273.

- Peterson, Helen. 2016. “Is Managing Academics “Women’s Work”? Exploring the Glass Cliff in Higher Education Management.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 44 (1): 112–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143214563897.

- Polkinghorne, Donald E. 1995. “Narrative Configuration in Qualitative Analysis.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 8 (1): 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951839950080103.

- Ruderman, Marian N. 2006. “Developing Women Leaders.” In Inspiring Leaders, edited by Ronald J. Burke and Cary Cooper, 320–341. London: Routledge.

- Schiller, Nina Glick, Linda Basch, and Cristina Blanc-Szanton. 1992. “Transnationalism: A New Analytic Framework for Understanding Migration.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 645 (1): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb33484.x.

- Shakeshaft, Charol. 1989. “The Gender Gap in Research in Educational Administration.” Educational Administration Quarterly 25 (4): 324–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X89025004002.

- Sherman, Whitney H. 2010. “Women’s Leadership across the Globe.” Journal of Educational Administration 48 (6), https://doi.org/10.1108/jea.2010.07448faa.001.

- Spring, Joel. 2008. “Research on Globalization and Education.” Review of Educational Research 78 (2): 330–363. http://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308317846.

- Steer, Liesbet, Julia Gillard, Emily Gustafsson-Wright, and Michael Latham. 2015. “Non-State Actors in Education in Developing Countries.” https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/102215-Non-State-Actors-in-Education-Framing-paper-Final.pdf.

- Sum, Nicola. 2019. Educational Leadership and Glocalisation: The Case of English Medium Schools in Bangladesh. PhD Thesis, Monash University.

- Sum, Nicola. 2021. “Glocalization: Issues and Strategies for School Leadership.” In The School Leadership Survival Guide: What to Do When Things Go Wrong, How To Learn from Mistakes, and Why You Should Prepare for The Worst, 117–130. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing.

- Sum, Nicola. 2022. “Teachers’ Perspectives of Implementing Foreign Curricula in Bangladesh: a Case Study in Change Management and Capacity Development in English Medium Schools.” In Globalization and Education: Teaching, Learning and Leading in the World Schoolhouse, 93–115. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing.

- UNESCO. 2015. Education for All 2000- 2015: Achievements and Challenges; EFA Global Monitoring Report 2015, 516.

- UNESCO/Council of Europe. 2000. “Code of Good Practice in the Provision of Transnational Education.” https://www.coe.int/en/web/higher-education-and-research/lisbon-recognition-convention.

- Vance, Charles M., and Yongsun Paik. 2001. “Where Do American Women Face their Biggest Obstacle to Expatriate Career Success? Back in their Own Backyard.” Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal 8 (3/4): 98–116. http://doi.org/10.1108/13527600110797308.

- Vella, Robert. 2022. “Leadership and Women: The Space between Us. Narrating the Stories of Senior Female Educational Leaders in Malta.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 50 (1): 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143220929034.

- Vertovec, Steven. 1999. “Conceiving and Researching Transnationalism.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 22 (2): 447–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/014198799329558.

- Werhane, Patricia H. 2007. “Women Leaders in a Globalized World.” Journal of Business Ethics 74: 425–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9516-z.

- Young, Michelle D., and Scott McLeod. 2001. “Flukes, Opportunities, and Planned Interventions: Factors Affecting Women’s Decisions to become School Administrators.” Educational Administration Quarterly 37 (4): 462–502. http://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X01374003.