ABSTRACT

This study argues that the common good, besides organizational performance, should be the final goal of organizational learning. However, the organisational learning literature lacks conceptual tools that allow scholars to understand and measure the common good at the ecosystem level as a final goal of organisational learning. Further, the literature has not yet investigated the specific organisational capabilities that are key to pursuing the common good, and lacks conceptual tools to explain the dynamics linking organisational learning, organisational performance, and the common good. We illustrate how these gaps can be addressed by cross-fertilising the literature on organisational knowledge with other viable and intertwining research streams—namely, literature on the commons, adaptive co-management and organisational fields. We argue that the resulting model of organisational learning paves the way for interesting innovations in theory and practice.

1. Introduction

What is the final goal of organisational learning and knowledge management? Many might answer: that organisations survive and thrive. And why is it important that organisations survive and thrive? Only because organisations are indispensable to serve the interests of some stakeholders? An alternative answer is possible: it is because organisations are social mechanisms with irreplaceable capacities to address societal problems and contribute to the common good (Ferraro, Etzion, & Gehman, Citation2015; George, Howard-Grenville, Joshi, & Tihanyi, Citation2016). Even if, regrettably, some organisations jeopardise or disrupt the common good (for example, through pollution), all human abilities to protect and regenerate the common good have an organisational basis (Hollensbe, Wookey, Hickey, & George, Citation2014; Stephan, Patterson, Kelly, & Mair, Citation2016). Therefore, one could argue that the common good, besides organisational performance, should be the real final goal of organisational learning and all knowledge-related research and practice areas, such as knowledge management and the learning organisation approach.

Nevertheless, the common good as a final expected consequence of organisational learning has remained under-investigated that far. Most researchers concentrate on firm performance variables (Carlucci & Schiuma, Citation2006), such as market share or stakeholder satisfaction, to assess the final expected outcome of organisational learning (Crossan, Maurer, & White, Citation2011). Some scholars are actually interested in the impact of organisational learning on the common good, for example in terms of system sustainability; however, these scholars usually leverage firm-level capabilities (such as the compliance to environmental laws) as proxies of the common good, without questioning whether these firm-level capabilities are really effective proxies of the common good or the system’s sustainability (Benn, Edwards, & Angus-Leppan, Citation2013). Scholars increasingly leverage institutional theories (Jyothibabu, Farooq, & Pradhan, Citation2010; Panagiotakopoulos, Espinosa, & Walker, Citation2016) or the stakeholder theory (Desai, Citation2018) to investigate the consequences of organisational learning. These theories may seem more compatible with the pursuit of the common good than the mainstream resource-based view approach (Quairel-Lanoizelée, Citation2011), but actually both the institutional and the stakeholder theory explain organisational performance (through legitimacy and stakeholder satisfaction), while remaining neutral about the real system-level consequences of complying with institutional and stakeholder pressures.

These difficulties in addressing the issue of the system-level consequences of organisational knowledge are raising growing unease in the scholarly community. Many researchers feel that overlooking the common good in organisational learning and knowledge management results in making the organisation “a beautiful canary in a coal mine”, that is, a sadly effective sensor of any decrease in the mine’s air quality, according to Dumay’s (Citation2013) effective metaphor. Scholarly awareness is growing that no matter how healthy and successful an organisation can become by leveraging its knowledge assets, if the system that the organisation depends upon is fragile (Smith, Citation2012).

Many interesting studies are providing interesting and innovative ideas on how the literature on organisational learning should and could address such a relevant issue. Starting from different backgrounds, these studies converge in suggesting that the management of organisational knowledge can better contribute to the common good if it leverages network-level coproduction processes (Benn et al., Citation2013; Schuttenberg & Guth, Citation2015), evidence-based decision making (Lalor & Hickey, Citation2014) and a participatory approach coupled with decentralised and distributed experimentation (Ferraro et al., Citation2015). An evolutionary approach that values organisational resilience (Bond, Morrison-Saunders, Gunn, Pope, & Retief, Citation2015; Kayes, Citation2015), as well as the organisation’s embeddedness in its social and institutional environment, is increasingly advocated (Lam, Citation2000; Vergne & Durand, Citation2011).

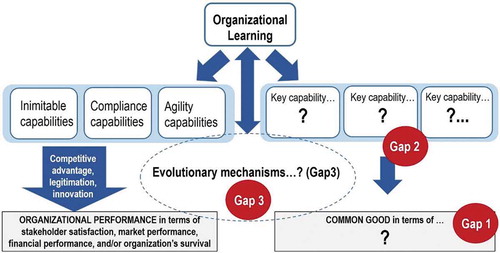

This article contributes to these efforts by conducting an analysis of the state-of-the-art in the organisational learning literature, and by identifying three gaps that, in our opinion, hinder the organisational learning community from developing a robust theory of the link between organisational learning and the common good. These three gaps are:

The organisational learning literature lacks conceptual tools allowing scholars to understand and measure the common good at the ecosystem level as a final goal of organisational learning;

The organisational learning literature has not investigated yet what specific organisational capabilities are key to pursuing the common good, and why;

The organisational learning literature lacks conceptual tools to explain the dynamics linking organisational learning, organisational performance, and the common good.

To contribute to addressing these three gaps, this article proposes to cross-fertilise the studies on organisational learning with conceptual tools borrowed from three literature streams that, although highly compatible and strongly intertwining with each other, have not been leveraged yet to address organisational learning research. These three literature streams are those on the commons and common resources (rooted in economics and political sciences) (Dietz, Ostrom, & Stern, Citation2003; Ostrom, Citation1990), on the adaptive co-management of social-ecological systems (SES) (rooted in ecosystem and resilience studies) (Plummer & Armitage, Citation2007), and on organisational fields (rooted in social studies and institutional theories) (Davis & Marquis, Citation2005; Furnari, Citation2016; Wooten & Hoffman, Citation2008).

The cross-fertilisation conducted in this study results in an original model of socially embedded, multi-level, adaptive organisational learning for the common good. The proposed model addresses the three gaps identified above and opens up some interesting possible research paths.

2. Background: three gaps in the organisational learning literature

2.1. State-of-the-art overview: organisational learning enables competitive advantage, legitimacy, and innovation, thus resulting in organisational performance

A relevant part of the literature on organisational learning is rooted in the knowledge-based view of the firm (Grant, Citation1996; Spender & Grant, Citation1996). Therefore, many publications in the organisational learning field are based on the idea that what makes learning and knowledge valuable to firms is their irreplaceable role in developing heterogeneous and inimitable capabilities for sustained competitive advantage (Barley, Treem, & Kuhn, Citation2018). The intellectual capital (Marr, Schiuma, & Neely, Citation2004) and knowledge management (Baskerville & Dulipovici, Citation2006) bodies of knowledge share the same roots. Under this theoretical perspective, effective organisational learning and knowledge management both result in enhanced inimitability and then firm performance, in terms of superior rents and/or market share (Hislop, Bosua, & Helms, Citation2018; Lopez, Salazar, & De Castro, Citation2006; Santos-Vijande, Lòpez-Sànchez, & Trespalacios, Citation2012).

Other authors mention improved compliance with operational excellence standards, laws, and/or stakeholders’ expectations as a key outcome of organisational learning. Compliance with operational excellence standards is often measured in terms of product and/or process quality (Miner & Mezias, Citation1996) and is often linked to a routine-based view of learning. Compliance with laws and norms (for example, environmental laws) is viewed as a source of legitimacy and then firm survival, in the light of the neo-institutional theory (Jyothibabu et al., Citation2010; Panagiotakopoulos et al., Citation2016). Compliance with stakeholders’ expectations is also sometimes cited as a positive effect of organisational learning, that leads to firm performance through legitimacy (Desai, Citation2018) or, again, through competitive advantage (Jones, Harrison, & Felps, Citation2018), consistently with the recent convergence of (instrumental) stakeholder theory and the resource-based view of the firm (Barney, Citation2018).

Further, several authors also concentrate on the importance of organisational learning and knowledge in order to develop organisational agility. In the face of today’s turbulent business environments, legitimacy and competitive advantage soon become insufficient unless the organisation is capable to innovate its products, processes, or strategy (Crossan & Berdrow, Citation2003). In this light, agility, rather than (or beside) inimitability and compliance, is the key capability to be developed (Argote & Miron-Spektor, Citation2011). Firms must continuously adapt to their ever-changing environments, and to do so, a close collaboration between knowledge management and organisational learning efforts is advocated as essential (Bennet & Bennet, Citation2004). This view converges with the viable literature on dynamic capabilities (Zollo & Winter, Citation2002).

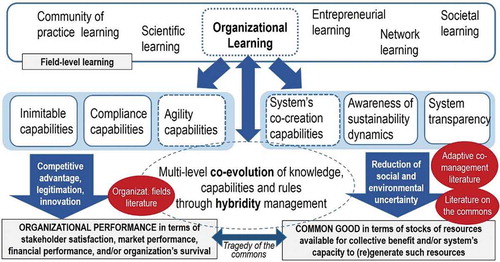

Overall, then, the literature suggests that organisational learning enables the development of inimitable capabilities, compliance capabilities, and agility capabilities, which in turn result in competitive advantage, legitimacy, and innovation: the keys to achieving firm performance, according to the mainstream theories in the management literature. This state-of-the-art is synthesised in the left part of . Based on this mental model, organisational learning scholars have dedicated significant efforts in understanding the learning processes that are expected to result in the capabilities and improvements in organisational performance synthesised in .

Figure 1. The consequences of organisational learning. Main findings of the extant literature (left) and research gaps identified by this study (right). Source: Authors

Typically, the organisational learning literature identifies three levels at which learning takes place: individual, group and organisation (Crossan, Lane, & White, Citation1999). Sometimes, a further level of analysis (inter-organisational network or organisational population) is introduced (Miner & Mezias, Citation1996). Part of the literature is devoted to studying specific learning processes and/or specific levels of analysis, such as the creation of new organisational routines (Zollo & Winter, Citation2002).

On the other hand, a significant part of the literature investigates organisational learning processes through polarised concepts, such as routine-based learning versus interpretation-based learning (Grandori, Kogut, Grandori, & Kogut, Citation2002), single-loop learning versus double-loop learning (Argyris, Citation2002), explicit versus tacit knowledge (Lam, Citation2000), exploitative versus explorative learning (Lavie, Stettner, & Tushman, Citation2010; Miner & Mezias, Citation1996), knowledge integration versus knowledge differentiation (Barley et al., Citation2018).

This polarisation is not surprising, for at least two reasons. On the one side, the literature on organisational learning is rooted in theoretical views of the organisation (such as the resource-based view, neo-institutionalism, stakeholder theory) that are significantly different or even frankly opposing. On the other side, a growing body of studies identifies oscillation between two opposing poles (Boumgarden, Nickerson, & Zenger, Citation2012) and dual tuning (George & Zhou, Citation2007) as a key mechanism of (organisational) learning, consistently with the recent development of the studies on organisational paradoxes (Andriopoulos & Lewis, Citation2010; Ricciardi, Zardini, & Rossignoli, Citation2016; Smith & Lewis, Citation2011). Therefore, the academic fight between, say, single-loop and double-loop learning (Argyris, Citation2002) corresponds to an oscillation or paradoxical co-existence that may be beneficial in the world of practice.

Other streams in the organisational learning literature investigate the key linear paths of learning in organisations. For example, Crossan et al. (Citation1999) model organisational learning as made up of four processes: intuiting, interpreting, integrating, and institutionalising. Argote and Miron-Spektor (Citation2011), on the other hand, identify three processes: knowledge creation, retention, and transfer.

Whilst the expected, optimal path of organisational learning has attracted a lot of scholarly attention, poor organisational learning has been much less investigated. In most cases, “poor organisational learning” is implicitly conceptualised as “lack of good/expected organisational learning”: for example, failure in correctly storing information in digital databases. However, some pioneering studies such as those on competency traps (Levitt & March, Citation1988) suggest that counter-productive learning cycles have their own dynamics that depend not only from opportunism or power games but also from bounded rationality or, in evolutionary terms, ecosystem rationality (Gigerenzer, Citation2001).

The existing scales of organisational learning (Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, Citation2011; Jyothibabu et al., Citation2010; Lloria & Moreno-Luzon, Citation2014) only partially reflect the research streams and theoretical views synthesised above. This is not surprising: a comprehensive understanding of organisational learning is extremely difficult to achieve (Easterby-Smith, Citation1997), let alone to operationalise.

2.2. Gaps to be addressed for an ecosystem theory of organisational learning

In their authoritative reflection, Crossan et al. (Citation2011) conclude that we still lack a robust theory of organisational learning, and suggest that an evolutionary ontology could provide the conceptual tools to develop such a theory. We take on this challenge and argue that an evolutionary approach of organisational learning implies to investigate the consequences of multi-level learning processes not only for the organisation, but also for the ecosystem (with its social, technological, and environmental components) that provides the organisation with the resources it depends upon (Aldrich & Ruef, Citation2006). This is a promising research path that we suggest could be taken by addressing three main and intertwining gaps, briefly synthesised below.

Gap 1: The organisational learning literature lacks conceptual tools allowing scholars to understand and measure the common good at the ecosystem level as a final goal of organisational learning. Several interesting studies and special issues (see for example Smith, Citation2012) have been published that focus on how organisational learning impacts the common good, for example in terms of social and environmental sustainability; however, in these studies the common good is assessed through mere formative measures (Diamantopoulos & Siguaw, Citation2006), such as compliance to existing environmental laws, that are simply borrowed from the traditional, firm-centric approach to organisational learning, and may be considered possible and partial antecedents, rather than proxies of actual common good, just as if they are possible and partial antecedents, rather than proxies of firm performance (see ). Compliance with institutional or stakeholder expectations is a (possible) means to achieve the common good, but it is not the common good (Wijen, Citation2014). In other words, the organisational learning literature lacks variables to measure the common good like sales, profits or customer satisfaction measure organisational performance in the left side of .

A recent and very interesting stream is focusing on the common good as a key organisational purpose (Hollensbe et al., Citation2014), and investigates how organisational learning changes when entrepreneurs/managers consider the pursuit of the greater good as a key value when making decisions (Mirvis, Herrera, Googins, & Albareda, Citation2016; O’Brien, Citation2009). This line of research advocates moral, humanistic principles for shaping organisational theory and practice, criticises an excessively technocratic approach to evaluation and accounting (Frémeaux, Puyou, & Michelson, Citation2018), and also demonstrates that competitive advantage can be unnecessary to explain the contribution of organisational learning to organisational survival: for example, non-profit organisations survive through legitimacy, social connectedness, and goodwill, which must then become the main goals of organisational learning (Moldavanova & Goerdel, Citation2018). This research stream is extremely interesting; however, it focuses on the pursuit of the common good as moral motivation, and does not provide tools to measure the common good as an expected outcome or impact.

Gap 2: The organisational learning literature has not investigated yet what specific organisational capabilities are key to pursuing the common good, and why. The organisational learning literature is investigating how the three key capabilities listed in (inimitable capabilities, compliance capabilities, and agility capabilities) can contribute also to the common good, besides organisational performance (Benn et al., Citation2013). We argue that these efforts are of great interest, but tend to overlook the “dark side” of the inimitability-compliance-agility paths leading to competitive advantage, legitimacy, and innovation. A firm’s inimitable capabilities may contribute to economic viability and prosperity, provided that the business ecosystem is based on fair, sustainability-oriented competition (Porter & Kramer, Citation2006). Compliance capabilities can contribute to safety, public health and social and environmental sustainability, provided that laws, norms, standards and social expectations promote technologies and behaviours that really maximise the common good (Wijen, Citation2014). Agility capabilities can contribute to sustainability transformations through adaptive, continuous innovation, provided that those innovations that threaten the common good are identified and stopped on time (Etzion, Gehman, Ferraro, & Avidan, Citation2017). Outside such boundary conditions, the (knowledge-based) pursuit of competitive advantage may negatively impact the common good.

Can organisational learning develop relevant “antibodies” to this “dark side” of competitive advantage, legitimacy, and innovation? We argue that the key capabilities that the organisational learning literature has so far identified as the goals of organisational learning are important but probably not sufficient to explain how organisational learning can concretely contribute to the common good.

Gap 3: The organisational learning literature lacks conceptual tools to explain the dynamics linking organisational learning, organisational performance, and the common good. The organisational learning literature is converging on the idea that an evolutionary approach is necessary to explain the possible positive and negative links between organisational learning and organisational performance, on the one side, and the common good, on the other side (Aldrich & Ruef, Citation2006; Crossan et al., Citation2011; Nelson & Winter, Citation2002; Pourdehnad & Smith, Citation2012; Zollo, Cennamo, & Neumann, Citation2013). A similar trend is observable in the knowledge management literature (Cheng, Niu, & Niu, Citation2014; Ford, Myrden, & Jones, Citation2015; Labedz, Cavaleri, & Berry, Citation2011; Manning & von Hagen, Citation2010; Parent, Roy, & St-Jacques, Citation2007; Sherif, Citation2006). In this light, adaptive learning needs to consider not only feedbacks from the markets, like in the traditional strategic management literature, but also from the value chain, local communities, governmental bodies, communities of practice, social movements, and particularly from all those actors that may represent next generations’ needs and rights. In some cases (such as family businesses with strong cross-generational vision and territorial rooting), these knowledge dynamics are more spontaneously hosted within the organisation’s boundaries; however, in most cases new conceptual tools are needed to understand how the dynamics and knowledge flows that occur beyond the organisation’s boundaries intertwine with organisational learning (Argote & Miron-Spektor, Citation2011; Barley et al., Citation2018; Lee & Cole, Citation2003; Nicolletti, Lutti, Souza, & Pagotto, Citation2019).

In fact, the mainstream management theories that organisational learning research usually leverages (that is, the resource-based view of the firm, neo-institutionalism, and stakeholder theory) provide important explanations to the frequent failures of organisational learning in contributing to the common good, but are poorly equipped to explain why organisational learning, by intertwining with network- or societal-level learning, is sometimes actually successful in enhancing the common good.

According to the resource-based view of the firm, if a firm develops a capability that can be relevant for the common good (for example, a new best practice for environmental sustainability) but also provides competitive advantage (for example, by improving firm image), that firm is unlikely to share such valuable capability with competitors, and therefore the positive system-level impact of the learning process, despite its potential, will be negligible (Quairel-Lanoizelée, Citation2011).

According to the neo-institutional theory, organisations are likely to adopt those practices that they are socially expected to adopt, independently from these practices’ actual impact on the common good. This is because what organisations really pursuit is legitimacy, and they tend to passively comply (often through façade practices) with what is expected by existing institutions, rather than contributing to inject more intelligence into such societal expectations for the common good. Therefore, also the neo-institutional theory does not really allow to be optimistic about the contribution of organisational learning to a positive evolution towards higher levels of the common good.

According to the stakeholder theory, organisations seek to satisfy those stakeholders that are perceived as more powerful and more legitimate than others, and that vehemently and effectively advocate their interests as the most urgent and important. In this vein, the influence of each stakeholder on the organisation’s decisions and behaviours is independent of the degree to which each stakeholder’s claim is actually beneficial (or not) to the common good. Therefore, also the stakeholder theory provides good explanations of why organisational learning is not likely to result in higher levels of the common good, but is poorly equipped to explain how and under what conditions the evolutionary dynamics enabled by organisational learning may actually have a positive impact on the common good.

The three gaps described above are synthesised in .

3. Addressing gap 1 by leveraging the literature on the commons and systems thinking: common resources and resource-generating systems

The broadening interdisciplinary debate on common goods has resulted in an interestingly wider range of the possible interpretations of the “common good” concept (Hess, Citation2008). The vocabulary of common goods is evolving and is being enriched with different and complementary meanings.

In its most traditional and widespread sense, a common good is a resource that is available for collective use: for example, fish from a certain marine area, the refreshing shadow from the neighbourhood park, wood from the forest, water from fountains, contents from Wikipedia. In this broad sense, therefore, the common good is any resource that can be used by the community.

This traditional view of common goods is strongly rooted in legal studies and has led to a distinction between real, proper common goods and public goods. In a legal-economic context, the common goods are generally defined as goods that are available for collective use but “rivalrous”, i.e. goods which, if used, are no longer available to others, as in the case of sea fish (Rose & Roset, Citation1986). Instead, in legal contexts public goodsFootnote1 are defined as goods that are available for collective use but not “rivalrous”: therefore, the use of public goods (differently form common goods) does not prejudice the possibility of (subsequent) use by others, as in the case of the security guaranteed by the police or the contents of Wikipedia (Cornes & Sandler, Citation1996). This distinction between common goods and public goods is very frequent in economic and legal jargon. For those who think of common goods in these terms, the main concern is the management and enforcement of the rights of use, in order to prevent the over-exploitation threat (Ostrom, Citation1990).

However, if we consider common resources from an administration and management perspective, rather than from a legal perspective, the focus shifts from the resource as such to the characteristics that make that resource valuable. From this point of view, the real common good is not sea fish as such, but rather its abundance and quality; the common good is not the neighbourhood park as such, but rather its cleanliness, usability and pleasantness; the common good is not the contents of Wikipedia as such, but rather their quality and their level of updating. For maintaining and developing these characteristics, the mere fact that users refrain from common resource overexploitation is often insufficient: innovation and coordinated action may be needed, and this may imply much more complex organisation and management issues (Ferraro et al., Citation2015).

In other words, if the focus shifts from the mere availability to the quality and value of the common resource, just protecting the resource from over-exploitation through effective rights of use may be insufficient. Problems, let alone solutions, may be far from self-evident, and original, ever-evolving activity systems are often needed for actively developing and maintaining the desired characteristics of the common resource (Adams, Brockington, Dyson, & Vira, Citation2003).

In this perspective, we can define a common good as a resource that is available for collective use by a community, and whose value and availability can only be maintained and/or developed through the collaboration of the beneficiaries themselves. This broader view stems from the discovery that “predatory” abuse or overuse (which is the main concern of the traditional legal approach to common goods) is only one of the ways in which a common resource can lose its value. Beneficiaries’ neglect, lethargy, mistakes, sabotage or disorganisation can also destroy the value of the common good (Cantino, Devalle, Cortese, Ricciardi, & Longo, Citation2017). For example, Wikipedia content is not vulnerable to overuse: rather, it is vulnerable to the possible neglect and lack of collaboration of its beneficiaries-authors (Hess, Citation2008). From this perspective, what defines the fragility of the common good is not only its possible “rivalry”, that is, the fact that it is vulnerable to consumption, but, more generally, its vulnerability to the behaviour (misuse, neglect, mistakes, disorganisation, sabotage) of the beneficiaries themselves. If Wikipedia users stop contributing to the construction of quality content, the encyclopaedia will be less and less useful; similarly, if fishermen take too much fish, each fishing trip will give fewer and smaller fish. In this sense, because of their vulnerability to the behaviour of the beneficiaries, the contents of Wikipedia are common resources (just like the fish of the sea), even if Wikipedia contents are not rivalrous, and then the traditional economic-legal perspective would rather define them as public goods (Hess, Citation2008).

A similar evolution towards a broader meaning has also occurred for the concept of “commons” (Dietz et al., Citation2003; Ostrom, Citation1990). A commons, in the Anglo-Saxon tradition, is a portion of territory from which a certain community can take resources: for example, a marine area where people can fish, a forest where people can get wood or chestnuts, a pasture where people can graze their cattle. Therefore, according to the economic-legal tradition, a commons is a portion of territory whose rights of use (and often also the property rights) belong to a certain community (Hardin, Citation1968).

From an administration and management perspective, however, the focus shifts from the area as such to the characteristics that make that area valuable. In this light, the key feature of a commons is its ability to generate and regenerate valuable resources that are available for collective use by a community (Cantino et al., Citation2017). For example, a pasture has a certain capacity to regenerate grass; a marine area has a certain capacity to regenerate fish. This logical step allows us to understand that the fragility of common goods is not only direct (for example, if a fisherman fills his nets, he has physically removed fish from the sea), but also, and more importantly, indirect (removing fish from the sea lowers the regenerative capacity of the ecosystem, because it disturbs reproduction processes and the food chain). In other words, the so-called “tragedy of the commons” often occurs when the regenerative capacity of the system is damaged beyond a certain critical threshold, so that the system irreversibly collapses (Walker et al., Citation2004). What really matters, therefore, is to understand, maintain and develop the regenerative capacity of the system: to do so, property rights and rights of use, even if effectively enforced, are often insufficient, because an active role of the beneficiaries may be needed (beyond the mere refraining from overexploitation).

From this point of view, the commons are not only areas with collective drawing rights, but, more generally, integrated ecosystems (with ecological, social, economic and technological components) capable of (re)generating common resources, i.e. resources available for the benefit of a community (Armitage et al., Citation2008). For example, Wikipedia is an integrated ecosystem made up of a vast network of people, enabled by technology and social rules of participation, which is able to (re)generate an important common good, namely the contents of the online encyclopaedia (Viégas, Wattenberg, & McKeon, Citation2007). The Torre Guaceto marine area is an integrated ecosystem formed by a natural environment, an institutional context, the culture of the local community, the competences of a group of scientists, the technologies and rules adopted by the fishermen, which is able to (re)generate many common goods, such as fish, tourist attractiveness and biodiversity (Cantino et al., Citation2017). From the point of view of the management of common goods, both the Wikipedia ecosystem and the Torre Guaceto ecosystem are commons, although the two systems are radically different as for legal ownership and rights of use.

The literature on the commons is rooted in system thinking and system dynamics, which are being increasingly advocated as excellent approaches to both sustainability-driven innovation (Bolton & Hannon, Citation2016) and organisational learning, learning organisation and knowledge management issues (Easterby-Smith, Citation1997; Senge & Sterman, Citation1992).

We argue that this new emerging view offers a valuable two-dimension definition of the common good, which can be viewed as (1) resources available for collective benefit, and (2) system’s capacity to (re)generate such resources. The two dimensions are measurable by leveraging a system dynamics approach (Pejic-Bach & Ceric, Citation2007). In the light of systems thinking and the system dynamics approach, the impact of organisational learning and can be operationalised as (1) change in stocks of common resources (inflows and/or outflows) that can be measured in the short term, and (2) change in the system’s capacity to (re)generate common resources: this capacity can be measured or forecasted thanks to system dynamics analyses. This possible definition of the common good is synthesised in (right, bottom).

4. Addressing gap 2 by leveraging the adaptive co-management literature: system sustainability awareness, co-creation, and transparency as key capabilities

If we define the common good in terms of common resource stocks and system’s capability to (re)generate such stocks, what are the key capabilities that can be developed thanks to organisational learning, and that can specifically contribute to such common good?

Interesting ideas to answer this question can be borrowed from outside the business and management literature. The stream of studies on social-ecological systems (SES) resilience (Armitage, Marschke, & Plummer, Citation2008; Berkes, Citation2009; Plummer et al., Citation2012; Brian Walker et al., Citation2004; Wyborn, Citation2015) has been developed by scholars with life science and system dynamics backgrounds, who realised that natural ecosystems cannot be understood separately from the economic, cultural, social and technological systems that interact with the natural ecosystem under study. For example, the social-ecological system of a marine area includes not only the natural ecosystem but also the social system that draws resources from the marine area, with actors such as fishing and tourism enterprises (Cantino et al., Citation2017). In today’s complex systems, the social mechanisms identified by Ostrom such as self-organisation, democratic participation and horizontal accountability under nested institutions are important, but insufficient to prevent the impending tragedy of the commons (Dietz et al., Citation2003). In fact, in most cases, the system’s actors (including policy-makers and scientists) have only a partial understanding of the real dynamics of the system (Cundill & Fabricius, Citation2009; Plummer et al., Citation2012). Therefore, the adaptive co-management approach suggests that fighting environmental and social uncertainty is the most important strategy to pursuit SES resilience, that is, SES’s sustained capability to (re)generate valuable common resources.

Environmental uncertainty occurs when people think that there is no reliable way to know how a certain social-ecological system is behaving and what is really going to happen. For example, people may think that there is no reliable knowledge about climate change. Environmental (perceived) uncertainty discourages sustainability-oriented efforts and provides people with reasons (or excuses) to keep behaving as usual or according to their perceived short-term convenience (Wijen, Citation2014). Environmental uncertainty is particularly dangerous if it involves ignorance or insufficient awareness about the system’s critical thresholds. In those cases, environmental uncertainty may lead to cross tipping points after which the negative dynamics irreversibly lead to system collapse, as happened, for example, on Easter Island. Therefore, we argue that awareness of sustainability dynamics is the first key capability that organisational learning should target in order to significantly improve the organisation’s contribution to the common good.

Social uncertainty, on the other hand, occurs when people think that it is unlikely that the others’ real behaviour about the common resources will come out. For example, people may think that it is impossible to know if each household actually and carefully differentiates waste. Social uncertainty discourages sustainability-oriented behaviours both directly and indirectly: on the one hand, people think that opportunists will not be punished and co-operators will not be rewarded or socially praised; on the other hand, people think that in such situation (almost) all the others will behave opportunistically. As a consequence, people think that making efforts to cooperate would have no significant impact on the system’s sustainability. In other words, social uncertainty results in a negative self-fulfiling prophecy about the common good. This mechanism is exacerbated by environmental uncertainty, but unfortunately it works also in the absence of environmental uncertainty: for example, social uncertainty can discourage differentiated waste collection even if people have no doubts about the potential positive impact of this solution. Social uncertainty is considered the key and basic mechanism of the tragedy of the commons (Ostrom, Citation1990). Therefore, we argue that system-level transparency on actors’ behaviours is the second key capability that organisational learning should target in order to significantly improve the organisation’s contribution to the common good.

The literature on adaptive co-management has the great merit of highlighting that, in today’s complex and ever-changing scenario, social uncertainty cannot be addressed unless also environmental uncertainty is addressed in an integrated fashion. Besides, the adaptive co-management literature has highlighted that the reduction of environmental uncertainty cannot be successfully achieved through a top-down process, from scientists to decision-makers and then citizens, because (a) scientists lack the knowledge resources that are maintained by other actors, such as local communities; and (b) people tend to reject the claims (and subsequent rules) that challenge their usual beliefs, habits, and perceived needs, while coming from a community (such as the scientific community) that people perceive as “alien”. For these reasons, the adaptive co-management approach suggests that each relevant social-ecological system develops its own network of collaborative learning, made up by scientists, government people, business people, and representatives of the local communities. The adaptive co-management approach recommends that these multi-level learning networks be orchestrated by a bridging organisation committed to transforming SES learning into decisions, and (since decisions result in possibly unpredicted consequences that provide new valuable information on the system) vice versa (Berkes, Citation2009). All of the organisations that can use and/or contribute to (re)generate a certain social-ecological system’s resources are expected to participate in SES adaptive co-management. This bottom-up participation requires specific cooperation and coordination capabilities that can only be developed through specific and multi-level organisational learning processes. Thus, we argue that the system’s adaptive co-creation is the third key capability that organisational learning should target in order to significantly improve the organisation’s contribution to the common good. synthesises this model that identifies the system’s co-creation capabilities, awareness of sustainability dynamics, and system transparency as the three key capabilities for the common good.

5. Addressing gap 3 by leveraging the literature on organisational fields: the multi-level co-evolution of knowledge, capabilities, and rules

As argued above in the Background section, the three mainstream theories that scholars usually leverage to explain phenomena relating with organisational learning (the resource-based view, neo-institutionalism, and stakeholder theory) are actually poorly equipped to shed light on the possible positive influence that organisational learning can have on the common good. On the other hand, SES studies have so far adopted a normative approach, thus often suffering from a partial understanding of the complex social phenomena that actually influence institutional dynamism (Brown, Farrelly, & Loorbach, Citation2013).

Not surprisingly, a robust theory of how organisational learning and knowledge can contribute to both organisational performance and the common good through positive evolutionary processes is increasingly perceived as much-needed (Crossan et al., Citation2011; Sherif, Citation2006).

We argue that the body of knowledge on organisational fields and institutional logics (Furnari, Citation2016) could provide effective conceptual tools to address such need.

Like neo-institutionalism, the theory of organisational fields and institutional logics assumes that people and organisations are highly embedded social actors whose behaviours largely depend on the need to gain and maintain social bonds and legitimacy. However, differently from the neo-institutionalist view, the organisational field view claims that social actors (including organisations) can play an active role in the transformation of the rules they are immersed in (Davis & Marquis, Citation2005).

The rules (values, norms, laws, technological standards, traditions etc.) shaping society are clustered around key societal institutions, such as the market, the family, or the bureaucratic State. These systems of internally consistent laws, norms, values, standards and beliefs are called institutional logics. The organisational field is the relational space an organisation is immersed in, and is much more complex than a market or a sector, because it is populated by several different and sometimes conflicting societal-level logics, such as the market logic, the bureaucratic logic, the social inclusion logic, the environmental logic, etcetera. Also local logics exist, around specific communities, network or organisations. Logics are essential in that they allow a sufficiently shared understanding of what happens and what should happen.

In the light of this theoretical view, knowledge becomes active at the societal level when it is “embedded” in an institutional logic, which transforms that knowledge into shared beliefs and rules. The (perceived) consequences of such beliefs and rules are then observed and evaluated, in the light of the carrying logic and the rival ones, and leveraged for shaping further learning processes. This co-evolution of knowledge and rules is at the heart of the evolutionary understanding of learning that the organisational field view enables.

When different logics coexist, this often results in ideological polarisation and conflict between people following different logics. These conflicts are sometimes mirrored by rival middle-range theories in economics and management (Davis & Marquis, Citation2005): for example, the resource-based view is consistent with the market logic, whilst the neo-institutional theory is consistent with the bureaucratic logic, which is often represented as a “rival” of the resource-based view (Quairel-Lanoizelée, Citation2011).

However, growing evidence suggests that organisations are powerful mechanisms for creatively integrating and hybridising divergent or even conflicting logics (Jay, Citation2013). For example, a microcredit company is typically based on both the banking logic, the market logic and the social inclusion logic (Battilana & Dorado, Citation2010). In all these cases, the organisation lives in a hybrid organisational field, and maintaining its hybrid identity is its key challenge (Mair, Mayer, & Lutz, Citation2015). To address such challenge, an individual or group or organisation or network can serve as an “institutional entrepreneur”, that seeks to change the system of social expectations and technological standards that shape organisational choices and behaviours (Garud, Hardy, & Maguire, Citation2007; Royston Greenwood, Diaz, Li, & Lorente, Citation2010; Venkataraman, Vermeulen, Raaijmakers, & Mair, Citation2016). The processes of knowledge creation, selection, retention and sharing are strongly influenced by such dynamics. In the light of the organisational fields view, learning is not only about creating knowledge: it is about changing the world through new beliefs and new rules (Smets, Morris, & Greenwood, Citation2012). In fact, as the studies on the commons and adaptive co-management have highlighted, knowledge can be useless or even counter-productive unless embedded in an adaptive institutional context: for example, in the absence of nested institutions and enforcement capabilities, even system-level transparency can become counter-productive, by showing people that opportunist behaviours are not hindered nor punished (Armitage et al., Citation2008).

In this light, learning is strictly intertwined with coordinated action and identity, not only at the team or organisation level, but also at the network and field levels (Davis & Marquis, Citation2005; Kogut & Zander, Citation1996). Organisational learning cannot be understood in isolation, since its processes are intertwined with those of community learning, scientific learning, network learning, and more generally, social learning (Coudel, Tonneau, & Rey-Valette, Citation2011), that innervate the organisational field . Therefore, the multi-level co-evolution of knowledge/capabilities and values/rules can be considered a possible key mechanism linking organisational learning to organisational performance, on the one side, and the common good, on the other side, as depicted in .

6. Discussion and conclusions: towards commons-oriented, system-level knowledge management and organisational learning

synthesises how, in our opinion, a cross-fertilisation of organisational learning research with the literatures on the commons, adaptive co-management of SES and organisational fields could provide useful conceptual tools to investigate the relationship between organisational learning and the common good.

The proposed model addresses Gap 1 (mainly through a cross-fertilisation with the literature on the commons and systems thinking) and proposes that the common good is measurable in terms of resource stocks and social-ecological system capacities. This operationalisation of the common good allows scholars to measure the common good as performance variable, separately from the organisational capabilities that (are expected to) contribute to such performance. This distinction between capability and performance is very important and overcomes the long-standing difficulties of measuring the common good with variables that actually express organisational capabilities (e.g., compliance with environmental norms) and therefore cannot measure those capabilities’ expected consequences. In traditional organisational learning research, a clear distinction between the capability that organisational learning is expected to enable (e.g., the capability to develop an inimitable new product) and firm performance (e.g., profits) has been key to the viability of the research stream, and we argue that a similar clear distinction between organisational capability and performance was necessary also to investigate the “common good side” of the organisational learning contributions.

Further, the proposed model addresses Gap 2 (mainly through the cross-fertilisation with the literature on the adaptive co-management of SES) and identifies three further “key target capabilities” for organisational learning: system’s co-creation capabilities, awareness of sustainability dynamics, and system transparency. Notably, these are system-level capabilities, that is, capabilities that are not developed by and within the organisation in isolation, but by and throughout the whole social-ecological system that (re)generates the common resources that are relevant to the organisation. From the point of view of classical economics, the idea that organisational learning should target capabilities that blossom also outside the organisational boundaries may sound absurd. However, the organisation’s dependence on common resources, the often collaborative nature of successful innovation, and the importance of common good-related legitimacy suggest that also system-level capabilities be considered as strategic. The three capabilities listed on the right side of complement the three more traditional capabilities listed on the left side (i.e., inimitability, compliance, and agility). Relevant direct and indirect crossed-media effects between the two groups of capabilities and the two types of expected outcomes are possible. For example, a compliance capability (e.g., the capability to comply with environmental norms) typically impacts also the common good, even if compliance is an organisational-level capability; sustainability awareness (e.g., awareness on the consequences of waste) often impacts also firm performance, even if it is a system-level capability. The two groups of capabilities identified by the model may also influence each other: for example, the system’s transparency may increase the firm’s compliance capabilities (especially if nested institutions and effective social control are in action at the organisational field level). In the proposed model, a particularly close relationship exists between agility, which is an organisational-level capability, and co-creation, which is a system-level capability: a positive interplay between these two nested capabilities (included in twin dotted boxes in ) is the engine of the dynamic multi-level evolution that is needed to transform learning into an adaptive process. This view is consistent with some recent and authoritative studies on the role of organisations in enabling sustainability transformations (Ferraro et al., Citation2015; Fjeldstad, Snow, Raymond, & Lettl, Citation2012; George et al., Citation2016; George, Mcgahan, & Prabhu, Citation2012).

Finally, the proposed model addresses Gap 3 (mainly through the cross-fertilisation with the literature on organisational fields) by suggesting that the evolutionary process of knowledge creation/variation, selection, and retention, cannot be understood by limiting the analysis at the organisational level, because the organisational dynamics that influence knowledge evolution are multi-level and also involve scientific learning, entrepreneurial learning, community learning, etcetera (Bolton & Hannon, Citation2016). The concept of institutional logic allows scholars to conceptualise organisational learning as a process that changes not only knowledge and capabilities, but also rules, and then social relationships (Beckert, Citation2010). This continuous co-evolution of knowledge, capabilities, and rules occurs in the organisational field, that is, a field of socio-cultural forces that include, but are not limited to, market forces, as well as social movements, technological standards, local traditions, laws, norms, etcetera.

We argue that the proposed model allows us to view the path from organisational learning to the common good not as opposed to, but rather as strictly intertwined with the more investigated and more traditional path from organisational learning to organisational performance.

We also suggest that the model proposed by this article may pave the way for new interesting paths in organisational learning and knowledge management research and practice.

First, scales and/or other measurement instruments could be usefully developed for the variables identified in the model synthesised in . Some of these variables, such as the system’s capacity to (re)generate common resources, cannot be measured directly (for example through a questionnaire), therefore require specific studies (based on system dynamics) to identify the key variables and mathematical relationships between variables that can allow the operationalisation of the construct (Meadows, Citation2009). These studies would provide a solid basis to take the scholarly community’s understanding of the consequences of organisational learning to the next level.

Second, the model invites scholars to investigate under what conditions and through what processes (e.g., the process of ecosystem rationality) (Gigerenzer, Citation2001) organisational learning results in the development of the six key capabilities identified in .

Third, it is important to investigate under what conditions and through what processes the six key capabilities and their interplay result in virtuous or vicious evolutionary dynamics (e.g., competency traps) (Levitt & March, Citation1988) that affect organisational performance and the common good.

Fourth, the model displayed in allows us to understand organisational learning as a key mechanism for organisation- and system-level resilience. This means that a possible convergence could be explored between studies on organisational learning and those on risk management.

Lastly, the results of the research streams listed above could provide useful tools for developing new and innovative solutions for practice, especially in the knowledge management domain (Labedz et al., Citation2011). A multi-level approach to knowledge management that links groups, organisations, institutions, networks, and communities could leverage the emerging power of big data and pervasive digitalisation for the common good. This approach is not intended to replace traditional firm-level knowledge management practices, but to enrich and integrate them into system-level, “smart,” and possibly participatory data flows (Cundill & Fabricius, Citation2009; Estrella, Citation2000; Nam & Pardo, Citation2011) that may multiply the usefulness of organisational learning and knowledge management practices.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. The concept of “public good” has a further, different meaning in evolutionary biology and the game theory literature. In that context, a “public good” is a consequence of an individually costly act that benefits all group members (Frank, Citation2010). The economic concept of “positive externality” (i.e., a consequence of an economic transaction that benefits third parties who are not involved in the transaction and do not pay for the benefit) is similar to the game-theory concept of public good.

References

- Adams, W. M., Brockington, D., Dyson, J., & Vira, B. (2003). Managing tragedies: Understanding conflict over common pool resources. Science, 302(5652), 1915–1916.

- Aldrich, H. E., & Ruef, M. (2006). Organizations evolving (second edition). London: Sage.

- Andriopoulos, C., & Lewis, M. W. (2010). Managing innovation paradoxes: Ambidexterity lessons from leading product design companies. Long Range Planning, 43(1), 104–122.

- Argote, L., & Miron-Spektor, E. (2011). Organizational learning: From experience to knowledge. Organization Science, 22(5), 1123–1137.

- Argyris, C. (2002). Double-loop learning, teaching, and research. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 1(2), 206–218.

- Armitage, D., Marschke, M., & Plummer, R. (2008). Adaptive co-management and the paradox of learning. Global Environmental Change, 18(1), 86–98.

- Barley, W. C., Treem, J. W., & Kuhn, T. (2018). Valuing multiple trajectories of knowledge: A critical review and agenda for knowledge management research. Academy of Management Annals, 12(1), 278–317.

- Barney, J. B. (2018). Why resource-based theory’s model of profit appropriation must incorporate a stakeholder perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 39(13), 3305–3325.

- Baskerville, R., & Dulipovici, A. (2006). The theoretical foundations of knowledge management. Knowledge Management Research and Practice, 4(2), 83–105.

- Battilana, J., & Dorado, S. (2010). Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6), 1419–1440.

- Beckert, J. (2010). How do fields change? the interrelations of institutions, networks, and cognition in the dynamics of markets. Organization Studies, 31(5), 605–627.

- Benn, S., Edwards, M., & Angus-Leppan, T. (2013). Organizational learning and the sustainability community of practice: The role of boundary objects. Organization and Environment, 26(2), 184–202.

- Bennet, A., & Bennet, D. (2004). The partnership between organizational learning and knowledge management. In C. Holsapple. (Ed.), Handbook of kowledge management 1 (pp. 439–455). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-24746-3

- Berkes, F. (2009). Evolution of co-management: Role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. Journal of Environmental Management, 90(5), 1692–1702.

- Bolton, R., & Hannon, M. (2016). Governing sustainability transitions through business model innovation: Towards a systems understanding. Research Policy, 45(9), 1731–1742.

- Bond, A., Morrison-Saunders, A., Gunn, J. A. E., Pope, J., & Retief, F. (2015). Managing uncertainty, ambiguity and ignorance in impact assessment by embedding evolutionary resilience, participatory modelling and adaptive management. Journal of Environmental Management, 151, 97–104.

- Boumgarden, P., Nickerson, J., & Zenger, T. R. (2012). Sailing into the wind: Exploring the relationships among ambidexterity, vacillation, and organizational performance. Strategic Management Journal, 33, 587–610.

- Brown, R. R., Farrelly, M. A., & Loorbach, D. A. (2013). Actors working the institutions in sustainability transitions: The case of Melbourne’s stormwater management. Global Environmental Change, 23(4), 701–718.

- Cantino, V., Devalle, A., Cortese, D., Ricciardi, F., & Longo, M. (2017). Place-based network organizations and embedded entrepreneurial learning: Emerging paths to sustainability. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research, 23(3), 504–523.

- Carlucci, D., & Schiuma, G. (2006). Knowledge asset value spiral: Linking knowledge assets to company’s performance. Knowledge and Process Management, 13(1), 35–46.

- Cheng, H., Niu, M.-S., & Niu, K.-H. (2014). Industrial cluster involvement, organizational learning, and organizational adaptation: An exploratory study in high technology industrial districts. Journal of Knowledge Management, 18(5), 971–990.

- Cornes, R., & Sandler, T. (1996). The theory of externalities, public goods, and club goods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Coudel, E., Tonneau, J.-P., & Rey-Valette, H. (2011). Diverse approaches to learning in rural and development studies: Review of the literature from the perspective of action learning. Knowledge Management Research and Practice, 9(2), 120–135.

- Crossan, M. M., & Berdrow, I. (2003). Organizational learning and strategic renewal. Strategic Management Journal, 24(11), 1087–1105.

- Crossan, M. M., Lane, H. W., & White, R. E. (1999). An organizational learning framework: From intuition to institution. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 522–537. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-0033247585&partnerID=40&md5=a71792eb027073f867ffb275a7a1e589

- Crossan, M. M., Maurer, C., & White, R. (2011). Reflections on the 2009 AMR decade award: Do we have a theory of organizational learning? Academy of Management Review, 36(3), 446–460.

- Cundill, G., & Fabricius, C. (2009). Monitoring in adaptive co-management: Toward a learning based approach. Journal of Environmental Management, 90(11), 3205–3211.

- Davis, G. F., & Marquis, C. (2005). Prospects for organization theory in the early twenty-first century: Institutional fields and mechanisms. Organization Science, 16(4), 332–343.

- Desai, V. M. (2018). Collaborative stakeholder engagement: An integration between theories of organizational legitimacy and learning. Academy of Management Journal, 61(1), 220–244.

- Diamantopoulos, A., & Siguaw, J. A. (2006). Formative versus reflective indicators in organizational measure development: A comparison and empirical illustration. British Journal of Management, 17(4), 263–282.

- Dietz, T., Ostrom, E., & Stern, P. C. (2003). The struggle to govern the commons. Science, 302(5652), 1907–1912.

- Dumay, J. (2013). The third stage of IC: Towards a new IC future and beyond. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 14(1), 5–9.

- Easterby-Smith, M. (1997). Disciplines of organizational learning: Contributions and critiques. Human Relations, 50(9), 1085–1113. Retrieved from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-0039378039&partnerID=40&md5=f1292726b6c266988e7664dc7102c3dc

- Estrella, M. (Ed.). (2000). Learning from change: Issues and experiences in participatory monitoring and evaluation. Ottawa: ITDG Publisher.

- Etzion, D., Gehman, J., Ferraro, F., & Avidan, M. (2017). Unleashing sustainability transformations through robust action. Journal of Cleaner Production, 140, 167–178.

- Ferraro, F., Etzion, D., & Gehman, J. (2015). Tackling grand challenges pragmatically: Robust action revisited. Organization Studies, 36(3), 363–390.

- Fjeldstad, O. D., Snow, C. C., Raymond, E. M., & Lettl, C. (2012). The architecture of collaboration. Strategic Management Journal, 33(6), 734–750.

- Ford, D., Myrden, S. E., & Jones, T. D. (2015). Understanding “disengagement from knowledge sharing”: Engagement theory versus adaptive cost theory. Journal of Knowledge Management, 19(3), 476–496.

- Frank, S. A. (2010). A general model of the public goods dilemma. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 23(6), 1245–1250.

- Frémeaux, S., Puyou, F.-R., & Michelson, G. (2018). Beyond accountants as technocrats: A common good perspective. Critical Perspectives on Accounting. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CPA.2018.07.003

- Furnari, S. (2016). Institutional fields as linked arenas: Inter-field resource dependence, institutional work and institutional change. Human Relations, 69(3), 551–580.

- Garud, R., Hardy, C., & Maguire, S. (2007). Institutional entrepreneurship as embedded agency: An introduction to the special issue. Organization Studies, 28(7), 957–969.

- George, G., Howard-Grenville, J., Joshi, A., & Tihanyi, L. (2016). Understanding and tackling societal grand challenges through management research. Academy of Management Journal, 59(6), 1880–1895.

- George, G., Mcgahan, A. M., & Prabhu, J. (2012). Innovation for inclusive growth : Towards a theoretical framework and a research agenda. Journal of Mangement Studies, 49(4), 661–683.

- George, J. M., & Zhou, J. (2007). Dual tuning in a supportive context: Joint contributions of positive mood, negative mood, and supervisory behaviors to employee creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 50(3), 605–622.

- Gigerenzer, G. (2001). The adaptive toolbox. In G. Gigerenzer, & R. Selton (Eds.), Bounded rationality: The adaptive toolbox (pp. 37–50). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Grandori, A., Kogut, B., Grandori, A., & Kogut, B. (2002). Dialogue on organization and knowledge. Organization Science, 13(3), 224–231.

- Grant, R. (1996). Toward a knoweldge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17(Winter Special Issue), 109–122.

- Greenwood, R., Diaz, A. M., Li, S. X., & Lorente, J. C. (2010). The multiplicity of institutional logics and the heterogeneity of organizational responses. Organization Science, 21(2), 521–539.

- Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons. Science, 162(3859), 1243–1248.

- Hess, C. (2008). Mapping the New Commons. In Governing shared resources: Conneting local experience to global challenges. The twelfth biennial conference of the international association for the study of the commons (pp. 1–76). doi:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1356835

- Hislop, D., Bosua, R., & Helms, R. (2018). Knowledge management in organizations: A critical introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hollensbe, E., Wookey, C., Hickey, L., & George, G. (2014). Organizations with purpose. Academy of Management Journal, 57(5), 1227–1234.

- Jay, J. (2013). Navigating paradox as a mechanism of change and innovation in hybrid organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 56(1), 137–159.

- Jiménez-Jiménez, D., & Sanz-Valle, R. (2011). Innovation, organizational learning, and performance. Journal of Business Research, 64(4), 408–417.

- Jones, T. M., Harrison, J. S., & Felps, W. (2018). How applying instrumental stakeholder theory can provide sustainable competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review, 43(3), 371–391.

- Jyothibabu, C., Farooq, A., & Pradhan, B. B. (2010). An integrated scale for measuring an organizational learning system. Learning Organization, 17(4), 303–327.

- Kayes, D. C. (2015). Organizational resilience: How learning sustains organizations in crisis, disaster, and breakdown. Oxford, USA: Oxford University Press.

- Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1996). What firms do? Coordination, identity, learning. Organization Science, 7(5), 502–518.

- Labedz, C. S., Cavaleri, S. A., & Berry, G. R. (2011). Interactive knowledge management: Putting pragmatic policy planning in place. Journal of Knowledge Management, 15(4), 551–567.

- Lalor, B. M., & Hickey, G. M. (2014). Strengthening the role of science in the environmental decision-making processes of executive government. Organization and Environment, 27(2), 161–180.

- Lam, A. (2000). Tacit knowledge, organizational learning and societal institutions: An integrated framework. Organization Studies, 21(3), 487–513. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-0010101822&partnerID=40&md5=13e49c5046e9527e05d7435fd0bc17a2

- Lavie, D., Stettner, U., & Tushman, M. L. (2010). Exploration and exploitation within and across organizations. Academy of Management Annals, 4(1), 109–155.

- Lee, G. K., & Cole, R. E. (2003). From a firm-based to a community-based model of knowledge creation: The case of the linux kernel development. Organization Science, 14(6), 633–755. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-0942278801&partnerID=40&md5=eb4343226dcb392d1028711c01798707

- Levitt, B., & March, J. (1988). Organizational Learning. Annual Review of Sociology, 14(1), 319–338.

- Lloria, M. B., & Moreno-Luzon, M. D. (2014). Organizational learning: Proposal of an integrative scale and research instrument. Journal of Business Research, 67(5), 692–697.

- Lopez, J. E. N., Salazar, E. A., & De Castro, G. M. (2006). Organizational capital as competitive advantage of the firm. Journal Of Intellectual Capital, 7(3), 324–337.

- Mair, J., Mayer, J., & Lutz, E. (2015). Navigating institutional plurality : Organizational governance in hybrid organizations. Organization Studies, 36(6), 713–739.

- Manning, S., & von Hagen, O. (2010). Linking local experiments to global standards: How project networks promote global institution-building. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 26(4), 398–416.

- Marr, B., Schiuma, G., & Neely, A. (2004). Intellectual capital–Defining key performance indicators for organizational knowledge assets. Business Process Management Journal, 10(5), 551–569.

- Meadows, D. H. (2009). Thinking in Systems. London: Sterling.

- Miner, A. S., & Mezias, S. J. (1996). Ugly duckling no more: past and futures of organizational learning research. Organization Science, 7(1), 88–99. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-0642345252&partnerID=40&md5=b4aa10693c3bd30a765e1ed264981803

- Mirvis, P., Herrera, M. E. B., Googins, B., & Albareda, L. (2016). Corporate social innovation: How firms learn to innovate for the greater good. Journal of Business Research, 69(11), 5014–5021.

- Moldavanova, A., & Goerdel, H. T. (2018). Understanding the puzzle of organizational sustainability: Toward a conceptual framework of organizational social connectedness and sustainability. Public Management Review, 20(1), 55–81.

- Nam, T., & Pardo, T. A. (2011, June). Conceptualizing smart city with dimensions of technology, people, and institutions. The Proceedings of the 12th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research Conceptualizing, College Park, MD, USA (pp. 282–291).

- Nelson, R. R., & Winter, S. G. (2002). Evolutionary theorizing in economics. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(2), 23–46.

- Nicolletti, M., Lutti, N., Souza, R., & Pagotto, L. (2019). Social and organizational learning in the adaptation to the process of climate change: The case of a Brazilian thermoplastic resins and petrochemical company. Journal of Cleaner Production, 226, 748–758.

- O’Brien, T. (2009). Reconsidering the common good in a business context. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(1), 25–37.

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Panagiotakopoulos, P. D., Espinosa, A., & Walker, J. (2016). Sustainability management: Insights from the viable system model. Journal of Cleaner Production, 113, 792–806.

- Parent, R., Roy, M., & St-Jacques, D. (2007). A systems-based dynamic knowledge transfer capacity model. Journal of Knowledge Management, 11(6), 81–93.

- Pejic-Bach, M., & Ceric, V. (2007). Developing system dynamics with step-by-step approach. Journal of Information and Organizational Sciences, 31(1), 171–185.

- Plummer, R., Crona, B., Armitage, D. R., Olsson, P., Tengö, M., & Yudina, O. (2012). Adaptive comanagement: A Systematic review and analysis. Ecology and Society, 17(3), 11. Retrieved from http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol17/iss3/art11/#methodologic5

- Plummer, R., & Armitage, D. (2007). A resilience-based framework for evaluating adaptive co-management: Linking ecology, economics and society in a complex world. Ecological Economics, 61(1), 62–74.

- Porter, M., & Kramer, M. R. (2006). Making the case for the competitive advantage of corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 78–92.

- Pourdehnad, J., & Smith, P. A. C. (2012). Sustainability, organizational learning, and lessons learned from aviation. The Learning Organization, 19(1), 77–86.

- Quairel-Lanoizelée, F. (2011). Are competition and corporate social responsibility compatible? The myth of sustainable competitive advantage. Society and Business Review, 6(1), 77–98.

- Ricciardi, F., Zardini, A., & Rossignoli, C. (2016). Organizational dynamism and adaptive business model innovation: The triple paradox configuration. Journal of Business Research, 69(11), 5487–5493.

- Rose, C. M., & Roset, C. (1986). The comedy of the commons : commerce, custom, and inherently public property. The University of Chicago Law Review, 53(3), 711–781. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/fss_papers/1828

- Santos-Vijande, M. L., Lòpez-Sànchez, J. A., & Trespalacios, J. A. (2012). How organizational learning affects a firm’s flexibility, competitive strategy, and performance. Journal of Business Research, 65(8), 1079–1089.

- Schuttenberg, H. Z., & Guth, H. K. (2015). Seeking our shared wisdom : A framework for understanding knowledge coproduction and coproductive capacities. Ecology and Society, 20(1), 1–15.

- Senge, P. M., & Sterman, J. D. (1992). Systems thinking and organizational learning: Acting locally and thinking globally in the organization of the future. European Journal of Operational Research, 59(1), 137–150.

- Sherif, K. (2006). An adaptive strategy for managing knowledge in organizations. Journal of Knowledge Management, 10(4), 72–80.

- Smets, M., Morris, T., & Greenwood, R. (2012). From practice to field: A multilevel model of practice-driven institutional change. Academy of Management Journal, 55(4), 877–904.

- Smith, P. A. C. (2012). The importance of organizational learning for organizational sustainability. The Learning Organization, 19(1), 4–10.

- Smith, W. K., & Lewis, M. W. (2011). Toward a theory of paradox: A dynamic equilibrium model of organizing. Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 381–403.

- Spender, J.-C., & Grant, R. M. (1996). Knowledge and the firm: Overview. Strategic Management Journal, 17(SUPPL.WINTER), 5–9. Retrieved from: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-3142609449&partnerID=40&md5=44191a5446add8136d4fa9ab0373982c

- Stephan, U., Patterson, M., Kelly, C., & Mair, J. (2016). Organizations driving positive social change : A review and an integrative framework of change processes. Journal of Management, 42(5), 1250–1281.

- Venkataraman, H., Vermeulen, P., Raaijmakers, A., & Mair, J. (2016). Market meets community: institutional logics as strategic resources for development work. Organization Studies, 37(5), 709–733.

- Vergne, J.-P., & Durand, R. (2011). The path of most persistence: An evolutionary perspective on path dependence and dynamic capabilities. Organization Studies, 32(3), 365–382.

- Viégas, F. B., Wattenberg, M., & McKeon, M. M. (2007). The Hidden Order of Wikipedia. In Online Communities and Social Computing (pp. 445–454). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-73257-0_49

- Walker, B., Holling, C. S., Carpenter, R. C., Kinzig, A., Carpenter, S. R., & Kinzig, A. (2004). Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social-ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 9(2), 5–25.

- Wijen, F. (2014). Means versus ends in opaque institutional fields: Trading off compliance and achievement in sustainability standard adoption. Academy of Management Review, 39(3), 302–323.

- Wooten, M., & Hoffman, A. J. (2008). Organizational fields: Past, present, and future. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, R. Suddaby, & K. Sahlin (Eds.), Handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 130–147). Sage Publications. doi:https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849200387

- Wyborn, C. (2015). Co-productive governance: A relational framework for adaptive governance. Global Environmental Change, 30, 56–67.

- Zollo, M., & Winter, S. G. (2002). Deliberate Learning and the Evolution of Dynamic Capabilities. Organization Science, 13(February2015), 339–351. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-0036014175&partnerID=40&md5=21dc1635bc5eb8e1560fd4a9c469e75a

- Zollo, M., Cennamo, C., & Neumann, K. (2013). Beyond what and why: Understanding organizational evolution towards sustainable enterprise models. Organization and Environment, 26(3), 241–259.