ABSTRACT

Translation has recently become a flourishing activity on the Web 2.0. Translations generated by “users” in various online scenarios have attracted growing interest from translation studies scholars. Along with the number of publications that mention “user-generated”, “crowdsourced”, or “community-based” translation grew the number of terms in play. While for some distinct forms of translation the terms seem to be firmly established (e.g. “fansubbing”), the discussion about how to label the top-level concepts of this field is not over yet. To further this discussion, this article undertakes a terminological analysis of the conceptual characteristics emerging from the relevant literature. The analysis shows that the top-level concepts are of a prototypical kind. The article then discusses the terms used for the top-level concepts with regard to motivation and presents a concept diagram that positions these concepts among other translation concepts.

Terminological modelling of processes

The success of the Web 2.0 has opened up a number of new possibilities to engage in translation and translation-related activities in a wide range of areas of communication, both for the traditional translation community and the general public, that is, for every “user” on the web. In translation studies, a plethora of terms to refer to these new forms of translation have appeared. While terms seem to be firmly established for some distinct forms of translation (e.g. “fansubbing” for the subtitling done by individual fans or fan groups), there is still no consensus about how to label the top-level concepts of this field. To tackle this issue, in this article I propose to take a terminological approach. Given the title of this special issue, I use *social translation* as a placeholder for designating the top-level concept.

Terminological analysis is concept-oriented (for a comprehensive overview of the theoretical and methodological issues in terminology addressed in this article, see Arntz, Picht, and Schmitz Citation2014). In terminology, a concept is a unit of knowledge created by a unique combination of characteristics which usually represents a multitude of objects in our thinking and communication. An object may be anything that can be perceived or conceived of. An object may be material, like the translation we bought in a bookstore, it may be immaterial like the act of translating, or it may be imaginary like the Babel fish in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. To describe or define concepts in terminology work, it is a prerequisite to identify their characteristics. Characteristics are also essential for understanding how the concepts in a field (like translation studies) relate to each other and for structuring concepts into concept systems. Types of characteristics are used as subdivision criteria (e.g. “machine translation”, “machine-aided human translation”, and “human translation” are concepts distinguished by employing “technology used” as the subdivision criterion). Pilke (Citation2002) describes the formation of scientific concepts as a process of selecting field-specific characteristics. She rightly points out “that a field-specific concept does not exist until there is a description, i.e. after the abstract characteristics have been realised within a subject filed”. Such a description does not need to be a definition: “Even a consensus on the intension of the concept within the field can be sufficient for specialised communication” (Pilke Citation2002, 16).

For the purpose of his article, I look at “translation” not as a concept representing artefacts, but as a “dynamic concept”, that is as a concept representing actions, processes, and the like. Pilke suggests six classes of characteristics that constitute the concepts of action: agent, intention, method, circumstances, location and time (Citation2002, 15). Nuopponen (Citation2007) takes up from there and distinguishes agent, object, instrument, way of doing, purpose, result, location, and phases as aspects to be considered for the analysis of dynamic concepts. In this article, I use Nuopponen’s typology to map the characteristics addressed in the literature on *social translation* in order to describe the intension of this concept and discuss the terms proposed and/or used as its designation with respect to general principles of term formation.

When it comes to coining new terms the following points should be considered (Arntz, Picht, and Schmitz Citation2014, 115–117). The term should be motivated or transparent, i.e. the semantics of the words and morphemes in use should reflect essential characteristics of the concept. This helps recipients understand the term, even though the concept might be unknown to them. At the same time, the term should be as linguistically economic (short) as possible. It is easy to see that these recommendations stand in conflict with each other. The longer the term (the more words are used), the easier it is to convey essential characteristics of the concept, and the easier it is to understand it. However, the longer the term, the greater the risk that it will be inconvenient to use. Another major aspect to take into account in this respect is the intended audience. Finally, newly coined terms should not already be in use for the designation of another concept.

In this article, I present the result of my analysis of characteristics of *social translation*. The focus of the following section is on the conceptual level, i.e. on the characteristics. I will specifically point out characteristics that serve as the motivational base for terms that are currently in use in the field. Other issues of term coinage will be addressed later.

Mapping conceptual characteristics

Characteristics related to agents

When discussing translation, a wide range of agents may be relevant: source text author, commissioner, translator, and target audience, various intermediaries, editors, managers; more agents could be added to the equation. For this article, I identified four agents: source text author, commissioner, translator, and target audience. Other agents (e.g. crowd or community manager) might have to be added depending on further development of the concepts in play. Based on the sources used for this study I do not consider them essential characteristics of the top-level concept.

In the context of *social translation*, the main interest is on the translator. In *social translation* this agent is constituted by a group of people: the so called “users”. As Michael Cronin eloquently puts it, “[i]mplicit in such a representation of translation is a move away from the monadic subject of traditional translation agency – Jerome alone in the desert – to a pluri-subjectivity of interaction” (Citation2010, 5).

The two types of groups of “users” that are most often mentioned are “crowd” and “community”. The distinction between “crowd” and “community” is not always easy to make. A first indicator is the group’s openness. The groups in question can be more or less open (cf. Mesipuu Citation2012). “Crowd”, especially “the crowd”, quite often seems to refer to the totality of web users, implying an infinite openness. “Crowds” and “communities” are formed by “users”. “Users” always means users of the internet. Translators in the crowd typically form a “rather large and undefined pool of people” (Fernández Costales Citation2012, 122); O’Hagan (Citation2009, 97; Citation2011, 11) talks about “unspecified” and “self-selected” individuals. In the case of communities, the shared mission, worldviews, and expertise in special fields of knowledge (be it software, video games, an area of fandom, or a political cause) may lead to some sort of typical user profile. This may be even true in “crowd” contexts, as pointed out by Anastasiou and Gupta (Citation2011, 638). Thus, in terms of qualities (assets) that users bring to the table, one deals with a continuum ranging from totally unspecified to specified sets of qualities. This will be discussed further later on.

Another subdivision criterion is the overall purpose of the group. Mitchell, Roturier, and O’Brien (Citation2013) see community-based work (in that case post-editing of machine translation output) as an activity in support of an overall purpose pursued by a group that is essentially non-translational in nature. Example: an online community dedicated to the development of a certain software package translates the software’s documentation. In contrast to that, in the case of “crowd post-editing” the overall purpose is translational. Example: a group is formed for proofreading machine translation output. After the tasks are completed, such a group would be discontinued, whereas in the first case the group would usually go on pursuing the development and promotion of the software. The other way to distinguish “crowd” from “community” builds on who initiates the translation process: O’Hagan (Citation2009) differentiates unsolicited from solicited translation. Unsolicited translation is typical of existing communities where the need for translation arises as a side effect of the group’s activities. Solicited translation typically becomes a task taken on by a crowd, not a community. Other authors share this distinction: a “call” (Jiménez Crespo Citation2017, 18), or an “open call” (Wasala et al. Citation2012, 15) is needed, and if answered, the call leads to the birth of a crowd to which the translation task can be crowdsourced. In my opinion, the two ways of distinction yield the same results. The advantage of Jiménez Crespo’s approach is that in most cases it will probably be easier to determine whether there is/was a call or not than to determine the scope of a community’s purpose(s).

The size of the group appears to be another indicator. Probably the most frequent attribute used in this respect is “large” or “very large”. Examples range from small four-digit figures in the case of the Haitian disaster aid initiative “Project 4636” (Munro Citation2010) to tens of thousands of volunteer translators working for the TED translation project (Jiménez Crespo Citation2017, 57). Although these numbers point in a clear direction concerning the meaning of “large”, there is no definite minimum of participants, but groups labelled “crowd” can be expected to be much larger than groups called “community”. In addition, the total size of the group offers no indication as to the number of group members that actually participate in the translation of a particular unit of translation (see also the discussion below).

The characteristics “crowd” and “community” form the motivational base for the coining of the terms “crowd-sourced translation” (McDonough Dolmaya Citation2012; Perrino Citation2009; Zaidan and Callison-Burch Citation2011), “crowdsourcing translation” (Anastasiou and Gupta Citation2011) “translation crowdsourcing” (Jiménez Crespo Citation2016, Citation2017), “community translation” (Morera, Aouad, and Collins Citation2012; O’Hagan Citation2011); “community-based translation” (Anastasiou and Gupta Citation2011); “community post-editing” (Mitchell, O’Brien, and Roturier Citation2014); “community-based post-editing” (Mitchell, Roturier, and O’Brien Citation2013).

Let us now turn to the “users” and potential user profiles: a characteristic repeatedly addressed is the users’ translational expertise. Against the background of what has just been said about asset profiles, participants may lack any kind of translational experience, any expertise: they may be experienced translators, maybe even professional translators; they may be untrained in translation, still in training, or fully trained but with limited experience. Various authors state that a user’s lack of translational expertise can be compensated by her/his expertise in the field of knowledge relevant to a specific translation (O’Hagan Citation2009, 99). Based on the literature, this seems to be especially relevant in software-related domains and in the context of video games.

In terms of their legal and economic relation to the commissioner of a translation (if there is one), users can be considered regular contractors, less privileged “turkers” (a neologism derived from “Amazon Mechanical Turk”, a commercial platform for crowd-sourcing human intelligence tasks), or volunteers. They are “not employees or workers along a company’s value chain” (La Fuente Citation2015, 211). Essential characteristics of the concept “volunteer” are the lack of obligation to perform the activity (Anastasiou and Gupta Citation2011), in positive terms the “free will to perform translation work which is not remunerated”, and the intention to act “to the benefit of others” (Olohan Citation2013, 19). The latter characteristic distinguishes volunteers from fans. Most authors seem to agree on the total lack of remuneration as a characteristic of volunteer work, for some “low payment” is not an obstacle (Anastasiou and Gupta Citation2011, 638).

In terms of their social function, users may act as translators, as communicative mediators. Depending on their relation to the product, they may become “prosumers” (O’Hagan Citation2009, 99). The users’ emotional relation to both the object and the result of translation determines her/his profile as a “fan”. Being a fan is essential for the formation of the concepts “fansubbing” (fans produce and share subtitled versions of movies or TV programmes), “scanlation” (fans produce and share translations of comics and graphic novels, which often need to be scanned first), and “romhacking” (fans produce and share localized versions of commercial video games, what usually involves hacking the game’s source code, which is stored in a “Read Only Memory” format), which form the most prominent types of fan translation. In the case of “fansubbing” (Díaz Cintas and Muñoz Sánchez Citation2006), being a fan also forms the motivational base for the coining of the term. Finally, the characteristic “user” motivates the term “user-generated translation”.

In the literature on *social translation*, the agent “target audience” (or members thereof) receives little attention. There is one aspect that sticks out, though: when translators become “prosumers”, they simultaneously become members of the target audience. Cronin points out that this accumulation of roles paves the way for a new model of translation: in his words (Citation2010, 4), the traditional model is a “production-oriented model of externality”. In the context of *social translation*, where the audience is no longer just a passive consumer but produces “their own self-representation as a target audience”, then “a consumer-oriented model of internality” comes to the fore (4). This is most evident in the case of fan translation, where translation is done by fans for fans (O’Hagan Citation2009) or new fans that might be gained. This new model also applies to cases like the Facebook translation project or communities supporting, e.g. open source software. It applies to wherever *social translation* “provides an opportunity for user communities to participate in shaping the linguistic and cultural distribution of the products they use” (Mesipuu Citation2012, 34). It does not, in my opinion, apply to settings where *social translation* is used in support of political, social, or educational agendas (e.g. TED translation project), or human aid initiatives. In these scenarios the “users” produce translations primarily for a target audience that they are not part of. “Target audience” here is to be understood as the target audience implied when translating. It is not about who actually uses (reads) the translation. The question is: who is the translation for? Is it for the translators and their group peers (Facebook) or is it for others (TED project)?

The agent translation commissioner is reflected in various notions of the “initiator” responsible for the “call”. The initiator is typically of corporate or institutional nature; however, it can also be an individual (La Fuente Citation2015, 211). The existence of a “call” and therefore of a commissioner is the delimiting characteristic for distinguishing “crowd-sourced translation” from “community translation”. In “community translation”, the “initiator” is the “community” itself. Therefore, in that case, the roles of commissioner, translator, and target audience converge in one single role, adding weight to the internality of this translation model.

Characteristics related to objects

In *social translation*, the characteristics of the object of the translation process are not different from those in traditional forms of translation. So, basically anything that may be translated in general can also become the object of *social translation* (for a comprehensive overview of the most common objects, see Jiménez Crespo Citation2017). The objects of *social translation* are typically chunks of discourse that may differ in size and textual qualities, may be mono-modal or multi-modal, may be self-contained and independent texts or belong to a larger set of texts (cf. Kageura et al. Citation2011; Morera Mesa, Collins, and Filip Citation2013, 4). Comics and videogames constitute objects of the process that, in their turn, are essential characteristics in the formation of the concepts “scanlation” and “romhacking”. In the case of post-editing, the object is the output of a machine translated text, i.e. a translation.

Characteristics related to instruments

When it comes to *social translation*, translation technology is an important topic. Fernández Costales discusses “translation teamware systems and collaborative translation environments … being designed and developed in order to allow people to work together in large translation projects” (Citation2012, 121). As the possibilities of new internet technologies paved the way to the rise of crowdsourcing (Howe Citation2006), the birth of *social translation* would not have been possible without the “open, participatory, and interactive nature of the Web 2.0” (Jiménez Crespo Citation2017, 1). Consequently, authors present the use of Web 2.0 technology as an essential characteristic of *social translation*: “Web 2.0 harnesses the potential of the internet in a more collaborative and peer-to-peer manner with emphasis on social interaction” (Anastasiou and Gupta Citation2011, 637). The technology used has to enable not only the management of translation projects but also this multidirectional interaction among the users. Some authors stress that platforms for *social translation* should “enable users to carry out translation efficiently and work collaboratively, as well as improve their translation competence” (Kageura et al. Citation2011, 50).

The general design of platforms for *social translation* depends on its orientation towards crowds or communities and on the workflows that need to be implemented. From a platform designer’s perspective, the determinacy of the expected source material (clearly defined sets of documents vs. unpredictable individual documents) may be taken into account for the design of the platform’s workflows (cf. Bey, Kageura, and Boitet Citation2005, 2). Issues that need to be tackled are user management, document management, versioning, multilingual support, group users, and user space(s) (Bey, Kageura, and Boitet Citation2006). In any case, both crowds and communities need management and control (Ray and Kelly Citation2011). Whether these functions are taken care of by someone from outside the crowd or by members of the community, the platform has to provide adequate functionalities in that respect. Kageura et al. (Citation2011, 50) describe a translation platform that they developed, which may serve as an example of such functionalities: “definition of groups and projects, within which users can share documents, user-registered reference resources, translation tasks and communications; … communication by means of message exchange and a bulletin board; … comparative display of different translation versions”. The definition of groups is an important aspect of translation project management. The possibility to share reference sources is a means of quality management, as is the comparative display of various different translations, which is helpful for assessing and choosing translations. The “message exchange” and “bulletin board” functionalities facilitate social interaction.

Social interaction in the context of social media uses various means of communication. In terms of the semiotic mode, communication may be text-based, audiovisual, and include emoticons. In terms of the number of participants, communication may happen one-on-one or in groups, which in turn can be open or closed; in terms of directness or real-time-ness, possible solutions include messages, chat rooms, and forums. Different platforms allow for varying types of translational interaction: writing translations, assessing translations by choosing from preselected options (e.g. like/dislike, ranking), commenting and editing translations. The intensity of interaction during translation will depend considerably on the working mode of the users. Users may work in groups or as individuals, and may work on individual self-contained translation units or units that are parts of larger sets (Kageura et al. Citation2011, 53). The platform needs to cater to the needs arising from the different working modes.

Platforms for *social translation* may include various tools in the translation workflow, such as machine translation, translation memories, dictionaries, and terminological databases. Platforms may integrate established resources that are available on the web. They may provide their users with tools to build up such resources on their own.

Characteristics related to ways of doing

“Social media” form the motivational base for the coining of the term “social translation”. Fernández Costales describes the context in which the various forms of *social translation* took shape as “a new scenario characterized by the speed of communications and the complexity of having a higher number of agents interacting with each other” (Citation2012, 116). Thus, what distinguishes *social translation* is the tempo of communication related to the process, e.g. the possibility of instant reaction, the lack, or negligibility, of time lags between the production and the reception of messages, and the fact that communication is generally multilateral. In addition to communication, *social translation* entails “collaboration” among users. The results of each instance of collaboration are also available in real-time to the group. “Collaboration”, one might argue, comprises “communication” or should not be seen separately. It is, however, my impression that not all acts of communication in *social translation* scenarios will be related to the translation tasks. In any case, “collaboration” is, in my estimation, the most frequent feature that comes up in the descriptions of individual cases of *social translation*, as well as in conceptual definitions. It forms the motivational base for the coining of the terms “collaborative translation” (Austermühl Citation2011; Fernández Costales Citation2013; Shimohata et al. Citation2001), “online collaborative translation” (Bey, Kageura, and Boitet Citation2006; Declerq Citation2014; Jiménez Crespo Citation2017), and “CT3”, i.e. “community, crowdsourced and collaborative translation” (DePalma and Kelly Citation2008).

Before going into what kinds of activities fall into the extension of the concept “collaboration”, let us look at what characterizes social media activities: “sharing” seems to be key. Users share objects they have created or authored (texts, pictures, videos), information (about objects, about acts of communication, and about virtually anything), and assessments (the classic like/dislike and its variants as well as comments). In addition to sharing there is also verbal conversation and users employ a mix of modes to encode their messages. In *social translation*, users share, of course, translations they authored, but they also share knowledge (world knowledge, linguistic knowledge, knowledge of translation strategies, knowledge about knowledge resources), exchange knowledge resources (glossaries, translation memories), use resources and translation aids provided by the translation platform, and contribute to the development of these tools, i.e. create or co-create such resources. Users assess translations using simple binary voting or more elaborate ranking mechanisms that the platforms provide. Adding an alternative translation is authoring and assessing at the same time, as a new proposal implicitly expresses dissatisfaction with existing translations. Translation assessment can also take a more traditional shape: users may verbalize their comments or start conversations about translations (Anastasiou and Gupta Citation2011, 641). Conversations related to translation might cover not only the assessment of specific translations, but also issues like translation problems and translation strategies in general, the users’ views on translation, and of course, issues related to the management of individual translation projects. Conversations about non-translational issues may concern technical issues that come up when using the platform, or, especially in community settings, the non-translational goals and views shared by the group; or they might just satisfy the need for social interaction between users of the group. Even seemingly pointless conversations might be important to the functioning of the group: they potentially contribute to upholding a community spirit that can be essential for the survival of a community translation project.

The intensity of user interaction differs greatly from case to case, whereby participation is by no means distributed equally among users: Anastasiou and Gupta (Citation2011, 641) refer to a study according to which “90% are ‘lurkers’ who never contribute, whereas 9% contribute a little and 1% of users account for all the action”. Munro (Citation2010, 4) also stresses the importance of individual commitment: “The most active translators still working after several weeks were, overwhelmingly, also those who had been the most active in the chat-room shortly after launch”.

Collaborative authoring of an individual translation can take different shapes: depending on the design of the translation platform, i.e. the workflow templates it provides for decision-making processes, a translation unit may be jointly evaluated, edited, and finalized by group members, including the translation unit’s author. This may happen in a manner resembling traditional forms of collaboration in the real world (exchange of feedback, presentation of arguments), or translated units may simply become the object of a voting or ranking process with no conversation among group members at all. These processes follow elaborate workflows that determine the ways decisions can go (Morera Mesa, Collins, and Filip Citation2013; Morera, Aouad, and Collins Citation2012). Having said all this, it should be noted that translations that come out of a *social translation* process may very well not be co-authored at all, but the work of a single translator.

Decisions made by the group are decisions on choices offered by the platform. No matter which way designers go to ensure that the group’s values and intentions prevail, it is the designers’ conception thereof that ultimately determines possible outcomes. This applies especially to technologies used in crowd contexts, but, in my view, to team-management solutions used in community scenarios as well. In some way, the *social translation* platform appears as the user’s actual interaction partner. Jiménez Crespo argues that in crowd contexts the “locus of control resides outside the community, within the initiating organization” (Citation2017, 15), whereas in community contexts the locus of control stays within the community. Translation teamware systems are usually designed not by the groups themselves. Even if it is safe to argue that communities have much more control over their own activities than crowds, the control exercised by the technology itself should not be underestimated.

Characteristics related to purpose

Characteristics related to purpose fall into two large groups: purposes of the *social translation* process as a whole and users’ motivations. In terms of the overall purpose of the process, *social translation* can serve two purposes: to cover users’ needs or respond to external, third-party demands. The latter evolve either in the course of the generation of economic value or in the course of solving social problems. A prototypical example of *social translation* in the service of generation of economic value would be the integration of crowd-sourced translation into the portfolio of professional language service providers. The Facebook translation project also falls into this category, because it aims at improving the product in order to gain new users and strengthen ties with subscribed users. Typical examples of *social translation* in the service of solving social problems are translation projects that assist human-aid activities like “Project 4636”, or the TED translation project. *Social translation* driven by users’ needs comprises all types of fan translation and translation projects that are part of open source software projects.

The motivation of users may be intrinsic or extrinsic or of mixed nature. Extrinsic motivators are payment or the expectation to build up cultural and social capital that may become useful at a later point. Intrinsic motivation is linked to non-material benefits that users may obtain from their commitment: helping people in need, supporting a good cause, being part of a community that shares one’s own interests or values, building up cultural, social, and symbolic capital in such a community, searching for a way of creative self-expression, experiencing the activity as recreational, etc. (Fernández Costales Citation2012; Olohan Citation2013; De Wille Citation2014; Jiménez Crespo Citation2015, 64; La Fuente Citation2015).

Characteristics related to results

The creation of subtitles is an essential characteristic in the formation of the concept “fansubbing”. Aside from that, similar to what has been said about characteristics related to the object, there is not much to elaborate on concerning characteristics related to the result of the translation process. A characteristic repeatedly addressed in the literature is the quality of the product, often in combination with the users’ levels of translational expertise. The quality of the translations produced in the course of *social translation* can vary from poor to high (cf. Jiménez Crespo Citation2017, 3). In addition to the translation, the translation process may produce by-products, for example in the form of language resources (Wasala et al. Citation2012, 15).

Characteristics related to location

One could argue that for *social translation*, the question of location in time and space plays virtually no role at all, since *social translation* takes place in a virtual space. However, *social translation* is inconceivable without the internet in its current form. The virtual space the internet creates is accessible in the real world from anywhere, at any time. Following this line of argument, “ubiquity” (Cronin Citation2010, 3; Jiménez Crespo Citation2017, 25) is to be considered an essential characteristic of *social translation*.

Characteristics related to phases

In the context of *social translation*, the phases of the translation process are reflected in the workflows implemented in the translation platforms used for crowdsourcing translation or in community translation scenarios. The workflows define the sequence of operations that can/have to be carried out by the platform and its users. These workflows can differ on several levels. Jiménez Crespo, in his comprehensive book on crowdsourcing and collaborative translation, refers to a typology of “translation crowdsourcing” drawn up by Aram Morera-Mesa, who distinguishes four types of workflows (Jiménez Crespo Citation2017, 32): “colony translations” (users produce multiple alternative translations for the same translation unit, which are then run through a selection process), “wiki translations” (as in Wikipedia, users can add and edit entries), “translation for engagement” (selection of translations is done by voting), and “crowd translation-edit-publish” (single-author translation of the entire text), where community interaction seems to set in only after the translation is completed (“at website level”).

The observation that in *social translation* it is often no longer obvious who authored, co-authored, edited, or published a translation, has led to speculations about the near end of the traditional translate–edit–publish scheme in general (cf. O’Hagan Citation2011, 17). Publications about workflows give a general idea of the designs of translation platforms (Bey, Kageura, and Boitet Citation2006; Kageura et al. Citation2011; Shimohata et al. Citation2001), and some even give a glimpse into selected workflow details (Morera Mesa, Collins, and Filip Citation2013). In my impression, the traditional phases are still present. They have changed in dimensions, of course. The “editing” is still clearly visible in the “Wiki” and “crowd translation-edit-publish” approaches, and probably even more so in workflows for community scenarios. In the “colony translation” and the “translation for engagement” approaches, the “editing” has been replaced by selecting, voting, and/or ranking mechanisms with or without human interaction. However, the main function of the editing phase, i.e. quality control, is still there. Finally, whatever path a translation unit takes in such a workflow, eventually it gets to the point where it is published.

Interestingly, the motivational base for coining the terms “romhacking” and “scanlation” is found in phases that might be considered pre-process, i.e. the breach of source code protection of videogames and the digitization of printed comic editions. These steps need to be completed before the actual translation process can begin.

Discussion

It was possible to identify a field-specific consensus (Pilke Citation2002, 16) on the concept *social translation* by identifying essential characteristics in the eight classes proposed by Nuopponen (Citation2007): agents, object, instruments, ways of doing, purpose, results, location, and phases. The characteristics can most easily be found in definitions, definition-like text segments, and, more often, “hidden” in the text. Therefore, identifying characteristics is to a large part an act of text interpretation (cf. Hebenstreit Citation2007). Generally, the authors in this field are not consistent in granularity and exhaustiveness when describing their concepts or aspects thereof.

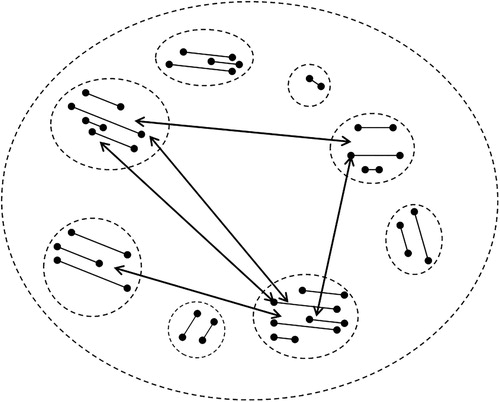

Let us start with some general observations: the characteristics related to agents, instruments, and ways of doing receive more attention than the characteristics related to the other aspects of the process. Most of these characteristics constitute concepts in themselves (e.g. collaboration). They form bundles of differing size, the contents of which are determined by the author defining the concept or, more often, elaborating on the concept while using it in her/his writing. These characteristics are typically not definite, but rather scalable in nature (e.g. size of crowds, determinacy of user profiles, functionalities implemented in the platform software, intensity, and quality of collaboration). As a result, the concepts have blurry boundaries and a prototype structure. illustrates the structure of such concepts: the concept’s characteristics fluctuate in a continuum of possibilities, depicted by lines with filled circles on both ends that represent the poles delimiting the continuum. The number of characteristics as well as the size of the ellipse grouping them signifies the relevance that an individual class of characteristics has in the conceptualization of a specific author. The double-ended arrows indicate that there are conceptual relations linking a characteristic with one or more other characteristics. Depending on the type of *social translation*, different relations come to the fore. In the case of “scanlation”, for example, the relation between agent and object is quite different from the relation between agent and object found in “crowdsourced translation”. In my view, translation studies concepts differ not only on the level of the selection of characteristics but also on the level of intra-conceptual relations between these characteristics.

To constitute a genuine subordinate concept of the concept of translation, *social translation* needs to have at least one characteristic in its intension (its specific set of characteristics) that differentiates it from translation (its generic concept) and other types of translation (its coordinate concepts). There are three classes of characteristics that play a dominant role in the literature: agent (the user), way of doing (collaborativeness), and instrument (social media technology). They can be used as the subdivision criterion on the generic level. Choosing a subdivision criterion is always, to some extent, a question of perspective, interests, maybe even ideology. In other words, this is not a simple issue of right or wrong. In my view, the subdivision criterion should be “instrument”, or, more specifically, “technology”, making “social media technology” the differentiating characteristic of *social translation*. One might argue that “users” and “collaborativeness” enjoy a greater status in the literature on *social translation* and that more of the already established terms have their motivational base in these characteristics. However, the concept of “users” would not exist if it were not for social media. They would still be real humans, of course, but not virtual “users” with the qualities ascribed to users of the Web 2.0. Thus, from a terminological point of view, “users” and “collaborativeness” are not independent characteristics, they depend on “social media technology”.

Terms proposed and/or in use for designating the concept *social translation* include “collaborative translation”, “online collaborative translation”, “CT3” or “community, crowdsourced and collaborative translation”, “social translation”, and “user-generated translation”. In terms of motivation, “community, crowdsourced and collaborative translation” sticks out. It reflects two types of user groups as well as collaboration as the way of doing. At the same time, the term is extremely unhandy. Its short form, “CT3”, may have a strong appeal to people with a deeper knowledge about what is happening on the web and who can appreciate the term’s formal qualities that reflect naming conventions in the field (e.g. W3C). To outsiders it will be a riddle, and non-natives will wonder how to pronounce the term. The term “collaborative translation” was also coined with existing Web 2.0 term formation patterns in mind (cf. collaborative tools, collaborative writing, collaborative learning, and collaborative enterprise). Without such a background, translation studies scholars might raise their eyebrows: since when is collaboration something unusual for translation practice? Then again, once they realize what it is about, why should translational collaboration be limited to the internet? The slightly longer term “online collaborative translation” will appear clearer to people not so knowledgeable about Web 2.0; a Web 2.0 native might consider it a tautology. Once it is clear what “collaboration” entails in the world of crowdsourcing (e.g. shrunk translation units, voting, selecting), one might feel misled by the expectations the term evokes (working together). “Social translation” is, again, a case of a term that follows word formation patterns in the world of the Web 2.0. Web 2.0 illiterate translation studies scholars will most probably relate the term to areas of public service translation (cf. Jiménez Crespo Citation2017, 27; O’Hagan Citation2011, 11–12). Because it is potentially misleading, I would advise against using this term. Jiménez Crespo (Citation2017, 28) considers “user-generated translation” the “most generic term”; I do not agree. It does not relate to a concept that would be higher up in the conceptual hierarchy, it just addresses a different aspect of the concept *social translation*. The term’s motivation is linked to the agent of the process whereas “collaborative translation” and “online collaborative translation” find their motivation in the way of doing. “Web 2.0 translation” (Austermühl Citation2011, 15) is the only term I found that is clearly motivated by technology, i.e. the subdivision criterion that I propose on the top level of the concept system. However, the dominant word formation patterns in translation studies might suggest that the Web 2.0 is the object of translation, not a means to perform translation. As a translation studies scholar I would favour terms that facilitate an immediate basic understanding across boundaries between various branches of translation studies. As a terminologist, I recommend that a term reflect the delimiting characteristic of the concept it refers to. I would, therefore, like to propose “social-media-driven translation” as the term for the concept *social translation*. It is motivated by the technology used, i.e. the main differentiating characteristic that distinguishes *social translation* from its generic concept “translation”. The word “driven” refers to the powerful dynamics that are intrinsic to social media and signifies that “social media” are more than just a medium. And last, but not least, “social-media-driven translation” reflects the “technological turn” in translation studies (Cronin Citation2010, 1; Declerq Citation2014, 38; Fernández Costales Citation2012, 118–120; O’Hagan Citation2013).

On the next level, I propose to use the type of “user group” as the subdivision criterion. The type of user group is determined by a complex set of characteristics as exemplified in (this matrix is not meant to be comprehensive). It is my impression that the conceptual boundaries between “crowd” and “community” are fuzzy, and new hybrid forms may surface at any moment in this highly dynamic field. Jiménez Crespo’s (Citation2017) choice for a subdivision criterion (namely, the existence of an open call) might very well work for the multitude of examples that exist so far, but it might be obsolete in short time. Just consider: what could keep a crowd that answers to a call from turning into a community?

Table 1. Proposed set of characteristics of translation performed by a crowd vs. by a community.

Terms for designating translation in and by a crowd should contain the word “crowd”: “crowdsourced translation” and “translation crowdsourcing” are equally motivated in that respect. What is different is the perspective of determination. In “crowdsourced translation”, it is translation that is determined by the agent and the instrument. In “translation crowdsourcing”, a crowdsourcing process is determined by the object of this process. The former term is in line with term formation patterns in translation studies (human translation, machine translation) and conveys a translation studies perspective. The latter points to two characteristics: that the locus of control lies outside of the crowd and that the purpose of the action is translational. It conveys a general process management perspective. The different perspectives become more apparent when combining the two terms with other translation studies terms: “norms in crowdsourced translation” or “strategies in crowdsourced translation” vs. “norms in translation crowdsourcing” or “strategies in translation crowdsourcing”. I opt for the translation studies perspective.

Terms for designating translation in online community scenarios should contain the word “community”. This leaves us with three equally motivated terms: “community translation”, “community-based translation”, and “community-driven translation”. “Community translation” is already in use as a term in the context of public service translation, and is therefore not recommendable for labelling a new concept in a related field. While “community-based translation” might still point towards public service settings, “community-driven translation” seems to be used in social-media-driven translation contexts only. Therefore, I would recommend this term for designating translation in online community scenarios.

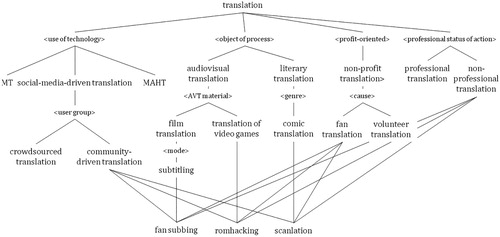

Concepts subordinate to “crowdsourced translation” or “community-driven translation” are concepts formed by means of conceptual conjunction, i.e. they have more than one generic concept. In other words, the concepts “community-driven translation”, “fan translation”, “non-professional translation”, and “subtitling” combine their conceptual intensions to form the shared subordinate concept “fansubbing”. The same applies to the concepts “romhacking” and “scanlation”. They are, in my view, forms of non-professional translation, because they are non-solicited and typically involve legally questionable or even illegal activities, and thus do not comply with the ethics of professional conduct.

shows a concept diagram, i.e. a graphic representation of the concept system discussed in this article. The types of characteristics being used as subdivision criteria are set between angle brackets.

To conclude, I would like to turn to a question asked in the call for this special issue: “Are terms like social, crowdsourced, user-generated, community and volunteer translation synonymous?” My, probably dissatisfying, answer is a counter-question: “Synonyms for the designation of which concept, in what kind of research context, and when?” From a descriptive point of view, such questions can only be answered separately for individual publications. According to Austermühl (Citation2011, 15), all of these terms have been used somewhere to designate “social-media-driven translation”. Over the past years, the distinction between “crowd” and “community” has gained ground (cf. Jiménez Crespo Citation2017). Therefore, it should be less likely to find the term “crowdsourced translation” in “community-driven translation” contexts in newer publications. However, that is a hypothesis that needs to be tested. From a prescriptive point of view of term selection, against the background of this analysis, only “user-generated translation” could serve as a synonym of “social-media-driven translation”. Furthermore, concepts change over time, be it as a reflection of change in the world of objects, or as a change in the way of understanding these objects. Terms do not always reflect such changes. Translation activities in the real or virtual world are usually instances of established translation concepts or combinations (e.g. conjunctions) thereof. Not every new phenomenon gets to be labelled with its own term, as in the case of fansubbing, romhacking, or scanlation. Community-driven volunteer translation, for example, does not have an established term yet. It is up to the communities of researchers and users whether it will some day. As I hope this article has shown, terminological analysis promotes a deeper understanding of conceptual structures and term formation patterns in the relevant fields, and is a helpful method for making informed decisions on the choice of terms.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Gernot Hebenstreit holds a doctoral degree in translation studies and is working as a researcher at the Institute of Translation Studies of the University of Graz (Austria). He is a member of the technical committee on terminology and language resources at Austrian Standards ASI and of ISO TC 37. Areas of teaching include translation theory, terminology theory and management, information technologies and translation. Research interests comprise terminology theory, methods of information modelling, translation theory, translation ethics, and multimodal translation.

ORCID

Gernot Hebenstreit http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8694-7451

References

- Anastasiou, Dimitra, and Rajat Gupta. 2011. “Comparison of Crowdsourcing Translation with Machine Translation.” Journal of Information Science 37 (6): 637–659. doi: 10.1177/0165551511418760

- Arntz, Reiner, Heribert Picht, and Klaus-Dirk Schmitz. 2014. Einführung in die Terminologiearbeit. 7th ed. Hildesheim: Olms.

- Austermühl, Frank. 2011. “On Clouds and Crowds: Current Developments in Translation Technology.” T21N, 1–25. https://www.t21n.com/homepage/articles/T21N-2011-07-Austermuehl.pdf.

- Bey, Youcef, Kyo Kageura, and Christian Boitet. 2005. “A Framework for Data Management for the Online Volunteer Translators’ Aid System QRLex.” In Proceedings of PACLIC 19, the 19th Asia-Pacific Conference on Language, Information and Computation. https://aclweb.org/anthology/Y/Y05/Y05-1005.pdf.

- Bey, Youcef, Kyo Kageura, and Christian Boitet. 2006. “The TRANSBey Prototype: An Online Collaborative Wiki-Based CAT Environment for Volunteer Translators.” In Third International Workshop on Language Resources for Translation Work, Research & Training (LR4Trans-III), edited by Elia Yuste, 49–54. Paris: ELRA. http://www.lrec-conf.org/proceedings/lrec2006/workshops/W17/proceedingsLR4TransIIIey.pdf.

- Cronin, Michael. 2010. “The Translation Crowd.” Revista Tradumàtica 8: 1–7.

- Declerq, Christophe. 2014. “Crowd, Cloud and Automation in the Translation Education Community.” Cultus 7: 37–56. https://www.cultusjournal.com/files/Archives/declercq_4_p.pdf.

- DePalma, Donald A., and Nataly Kelly. 2008. Translation of, by, and For the People: How User-Translated Content Projects Work in Real Life. Lowell: Common Sense Advisory.

- De Wille, Tabea. 2014. “Competence and Motivation in Volunteer Translators: The Example of Translation Commons.” MA diss., University of Limerick. https://hdl.handle.net/10344/4440

- Díaz Cintas, Jorge, and Pablo Muñoz Sánchez. 2006. “Fansubs: Audiovisual Translation in an Amateur Environment.” JoSTrans 6: 37–52. https://www.jostrans.org/issue06/art_diaz_munoz.pdf.

- Fernández Costales, Alberto. 2012. “Collaborative Translation Revisited: Exploring the Rationale and the Motivation for Volunteer Translation.” Forum 10 (1): 115–142. doi: 10.1075/forum.10.1.06fer

- Fernández Costales, Alberto. 2013. “Crowdsourcing and Collaborative Translation: Mass Phenomena or Silent Threat to Translation Studies?” Hermēneus 15: 85–110. https://www5.uva.es/hermeneus/hermeneus/15/arti03_15.pdf.

- Hebenstreit, Gernot. 2007. “Defining Patterns in Translation Studies: Revisiting Two Classics of German Translationswissenschaft.” Target 19 (2): 197–215. doi: 10.1075/target.19.2.03heb

- Howe, Jeff. 2006. “The Rise of Crowdsourcing.” Wired (June). https://www.wired.com/2006/06/crowds/.

- Jiménez Crespo, Miguel A. 2015. “Volunteer and Collaborative Translation.” In Researching Translation and Interpreting, edited by Claudia V. Angelelli, and Brian J. Baer, 58–70. London: Routledge.

- Jiménez Crespo, Miguel A. 2016. “Mobile Apps and Translation Crowdsourcing: The Next Frontier in the Evolution of Translation.” Revista Tradumàtica 14: 75–84. doi: 10.5565/rev/tradumatica.167

- Jiménez Crespo, Miguel A. 2017. Crowdsourcing and Online Collaborative Translations: Expanding the Limits of Translation Studies. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Kageura, Kyo, Takeshi Abekawa, Masao Utiyama, and Miori Sagara. 2011. “Has Translation Gone Online and Collaborative? An Experience from Minna No Hon’yaku.” Linguistica Antverpiensia 10: 47–72. https://lans-tts.uantwerpen.be/index.php/LANS-TTS/article/download/280/178.

- La Fuente, Lidia C. D. 2015. “Motivation to Collaboration in TED Open Translation Project.” International Journal of Web Based Communities 11 (2): 210–229. doi: 10.1504/IJWBC.2015.068542

- McDonough Dolmaya, Julie. 2012. “Analyzing the Crowdsourcing Model and Its Impact on Public Perceptions of Translation.” The Translator 18 (2): 167–191. doi: 10.1080/13556509.2012.10799507

- Mesipuu, Marit. 2012. “Translation Crowdsourcing and User-Translator Motivation at Facebook and Skype.” Translation Spaces 1 (1): 33–53. doi: 10.1075/ts.1.03mes

- Mitchell, Linda, Sharon O’Brien, and Johann Roturier. 2014. “Quality Evaluation in Community Post-Editing.” Machine Translation 28 (3–4): 237–262. doi: 10.1007/s10590-014-9160-1

- Mitchell, Linda, Johann Roturier, and Sharon O’Brien. 2013. “Community-Based Post-Editing of Machine-Translated Content: Monolingual vs. Bilingual.” In Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Post-Editing Technology and Practice (WPTP-2), edited by Sharon O’Brien, Michel Simard, and Lucia Specia, 35–43. http://www.mt-archive.info/10/MTS-2013-W2-Mitchell.pdf.

- Morera, Aram, Lamine Aouad, and John J. Collins. 2012. “Assessing Support for Community Workflows in Localisation.” In Business Process Management Workshop (BPD 2011): Revised Selected Papers, edited by Florian Daniel, Kamel Barkaoui, and Schahram Dustdar, 195–206. Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing (Internet) Vol. 99. Heidelberg: Springer.

- Morera Mesa, Aram, John J. Collins, and David Filip. 2013. “Selected Crowdsourced Translation Practices.” In Proceedings of ASLIB Translating and the Computer 34. https://www.mt-archive.info/10/Aslib-2013-Morera-Mesa.pdf.

- Munro, Robert. 2010. “Crowdsourced Translation for Emergency Response in Haiti: The Global Collaboration of Local Knowledge.” In Proceedings of AMTA 2010 The Ninth Conference of the Association for Machine Translation in the Americas, 1–4. http://www.mt-archive.info/10/AMTA-2010-Munro.pdf.

- Nuopponen, Anita. 2007. “Terminological Modelling of Processes: An Experiment.” In Indeterminacy in Terminology and LSP, edited by Bassey E. Antia, Christer Lauren, and Carolina Popp, 199–213. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- O’Hagan, Minako. 2009. “Evolution of User-Generated Translation: Fansubs, Translation Hacking and Crowdsourcing.” The Journal of Internationalization and Localization 1 (4): 94–121. doi: 10.1075/jial.1.04hag

- O’Hagan, Minako. 2011. “Community Translation: Translation as a Social Activity and Its Possible Consequences in the Advent of Web 2.0 and Beyond.” Linguistica Antverpiensia 10: 11–23. https://lans-tts.uantwerpen.be/index.php/LANS-TTS/article/download/275/173.

- O’Hagan, Minako. 2013. “The Impact of New Technologies on Translation Studies: A Technological Turn?” In The Routledge Handbook of Translation Studies, edited by Carmen Millán and Francesca Bartrina, 503–518. London: Routledge.

- Olohan, Maeve. 2013. “Why Do You Translate? Motivation to Volunteer and TED Translation.” Translation Studies 7 (1): 17–33. doi: 10.1080/14781700.2013.781952

- Perrino, Saverio. 2009. “User-Generated Translation: The Future of Translation in a Web 2.0 Environment.” JoSTrans 12: 55–78. https://www.jostrans.org/issue12/art_perrino.php.

- Pilke, Nina. 2002. “The Concept and the Object in Terminology Science.” IITF Journal 13 (1–2): 7–26.

- Ray, Rebecca, and Nataly Kelly. 2011. “Crowdsourced Translation: Best Practices for Implementation.” https://insights.csa-research.com/reportaction/1317/Marketing.

- Shimohata, Sayori, Mihoko Kitamura, Tatsuya Sukehiro, and Toshiki Murata. 2001. “Collaborative Translation Environment on the Web.” In MT Summit VIII: Machine Translation in the Information Age Santiago de Compostela, Spain 18–22 September 2001, edited by Bente Maegaard. http://www.mt-archive.info/MTS-2001-Shimohata.pdf.

- Wasala, Asanka, Reinhard Schaler, Ruvan Weerasinghe, and Chris Exton. 2012. “Collaboratively Building Language Resources While Localising the Web.” In Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on the People’s Web Meets NLP, ACL 2012, edited by Iryna Gurevych, Nicoletta Calzolari Zamorani, and Jungi Kim, 15–19. https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/W12-4003.

- Zaidan, Omar Z., and Chris Callison-Burch. 2011. “Crowdsourcing Translation: Professional Quality from Non-Professionals.” In Proceedings of the 49th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies. Volume 1: Long Papers, 1220–1229. https://cs.jhu.edu/~ozaidan/papers/Zaidan-CCB_turk-trans_acl2011.pdf.