ABSTRACT

This article argues that the study of religious translation can greatly benefit from a material turn, that attention needs to be paid to the carriers and forms of religious translations, and that such an approach can ultimately add different understandings of the translation process and alternative readings of religious texts. Drawing on theories of material culture, it proposes engagement with the material structures, practices and spaces that accompany translations. The article explores the modalities of engagement with the religious translation and the values and meanings that are associated with the object. It suggests a consideration not merely of the translated object, but also its related entanglements and sensory engagements, situating the text within its associated practices, assemblages and networks. It furthermore proposes an empirical engagement with the object and an exploration of the variations in form which exist in the possible afterlives of texts.

Introduction

At first glance, the field of religious translation might seem rather unsuited to a study of materiality. With its spiritual concerns, religion could indeed be conceived as far removed from materiality, but this dichotomy is in fact more perceived than real. Religion as a communicative system needs an apparatus or carrier for the transmission of its ideas and tenets, with beliefs taking material form as they circulate through externally recognizable media. This article will argue that the study of religious translation can greatly benefit from a material turn, that attention needs to be paid to the carriers and forms of religious translations, and that such an approach can contribute to new engagements with translations. A focus on the medium and materiality of translation is particularly important for religious translations where the haptic has a special meaning, and where the sacred and the profane intertwine on multiple levels.Footnote1 In considering religious translation as a material act, reliant on tools, the article will discuss the importance of highlighting the mechanical and pragmatic aspects of producing and using translations. It will apply the methodologies of material culture to the study of religious translation, using its multi-layered conceptualization of objects to unpack aspects of religious translations which have hitherto received scant attention. There are many benefits to be gained from this perspective: the combination of interdisciplinary approaches related to material culture encompassing (but not limited to) anthropology, sociology, art history, cultural studies and book history can help translation scholars better grasp the totality of the translation and understand its relationality. The rich methodologies developed for the study of material culture are an important, but neglected, resource for translation scholars offering alternative engagements with translated texts. The benefit of addressing materiality is mutual to both translation studies and religious studies and can assist in understanding the embodiment, embedding and transformation of religion through translation.

The study of religious translation has broadened greatly in recent years from its strong textual tradition and a sustained focus on equivalence and translatability (DeJonge and Tietz Citation2015; Long Citation2005; Nida and Taber Citation1969), to wider conceptualisations of the interaction between translation and religion in conceptual terms, not least in relation to performativity, power structures and commensurability (Blumczynski and Gillespie Citation2016; Israel Citation2011, Citation2019). This article suggests that attention to the materiality of religious translation is now an important step that needs to be taken in order to unlock aspects of religious translations that are not always revealed by traditional approaches. Since Karin Littau’s publications underlining the significance of materiality in translation, there has been a renewed focus on the material channels of translation and the role of technologies, forms, media and networks in the creation of meaning (Coldiron Citation2015, Citation2016; Cronin Citation2013; Littau Citation2011, Citation2016; Mitchell Citation2010), thus raising awareness of the need to address these issues in relation to translation.

Religious studies have similarly become aware of the importance of materiality, with material religion now a fully-fledged branch of the field, along with the more established areas of philological studies of scriptures, and philosophical studies of cosmology and religious ontology (Morgan Citation2017, 272). Using a material analysis of objects and sites as primary evidence in the study of religion has become very diffuse, and since 2005 the Journal of Material Religion has argued that religion is “fundamentally material in practice” given that it is not something “one does with speech or reason alone, but with the body and the spaces it inhabits” (Editorial statement Citation2005, 5). Since then, various scholars have asserted that all religion has to be understood in relation to the media of its materiality (Engelke Citation2011) and that the interplay between religion and materiality is a fundamental part of the study of religion (Houtman and Meyer Citation2012; Matthews-Jones and Jones Citation2015; Morgan Citation2016, Citation2017).

Key proponents of material religion have set themselves the task of understanding “how religion happens materially” (Meyer et al. Citation2010) and what happens when objects become “saturated with religious meanings” (Morgan Citation2011). The precise duality between the sacred and the profane is a central question in the field, as attempts are made to understand how something perceived as transcendental can function in the realm of lived experience. Scholars have questioned how objects can be sacralized through rituals, modes of use, interpretations and meanings. Attention to the materiality of religious works enables, in the words of Colleen McDannell, a “scrambling of the sacred and the profane” (Citation1995, 4), with these terms no longer considered a dichotomy, along with spirit and matter, piety and commerce, but instead components of a religious assemblage. The material framework provides a mode of analysis for sacrality, with a specific focus on mediations, intersections and combinations. The material analysis of religion furthermore emphasizes the affects which link the spiritual and the material, examining how sacrality is experienced, how the senses are engaged, the ritual settings, the performative elements and the role of objects in linking collective practices of religion to individual experience. A broad understanding of sacrality underpins the approach in this article which does not confine itself to ethereal matters and the traditional sacred canon of texts at the core of many religions but instead looks at wider manifestations of sacrality in texts which are used for devotional and ritual practices. Religious texts are understood here as texts integral to the practices of a believing community, with the focus not on the status of the original (and associations with divinity), but rather on the purpose and role of these texts which can be read through their materiality.

This article will take the novel step of considering how and to what extent religious texts in translation can benefit from being considered in a material light: while studies of religious translations have often looked at language and content, here attention will be drawn to the necessity of also considering the medium, its technical properties, and the significance an object acquires from its form. It will question how translations articulate religion and sacrality, and how the seemingly profane nature of a material object can be imbued with sacred associations. Furthermore, I will examine the extent to which religious translations can offer insights into the material functioning of religion and how engagement with religious translation does not need to be removed from the lived experience. The interface between materiality and religious translation is thus a critical encounter, one where the practice of religion is embedded in religious props and where the transnational circulation of religious words is viewed not just at a linguistic, cultural or conceptual level but also at the material and medial level.

To consider religious translations as material expressions of faith, this article employs the methodologies of material culture which have been regularly used to discuss the religious field, but never the field of religious translations. In this context, it is necessary to consider the object and its related entanglements, with meaning not residing singularly in an object but also deriving from its circulation, use, haptic engagement, and affective connections (Meyer et al. Citation2010, 209). The critical notion of entanglement, most cogently argued by Ian Hodder (Citation2012), proposes that the linking of humans and things is a condition of being in the world. Through assemblages and networks, entities are entangled, often co-dependent and cannot be studied in isolation. The interest in materiality is therefore also an interest in relations and intersections, a questioning of the input of those who contribute to the creation, circulation and use of an object. Book history, which has intertwined very profitably with translation studies in recent years to focus on communication circuits,Footnote2 features here as a point of departure in studying the specificity of religious translations, with supplementary dimensions added from the study of material culture which emphasize practices, entanglements and object-determinism. Even though the present case study centres on a book, the application of materiality to religious translation should not be considered as confined to books. Indeed, the discussions are relevant for many elaborations of religious translations including, for example, those in new media, multimodal translations and non-textual iterations.Footnote3

Within the methodological framework, the aforementioned notion of assemblage is important: it is a concept and ontological framework first expressed as “agencement” in French by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in their book A Thousand Plateaus (Citation1988; Citation1980) and later developed into a theoretical approach by Manuel DeLanda (Citation2019). In analysing translations, the term can be productive as it helps to understand how entities are made up of relationships between component parts: an assemblage is understood to be formed of multiplicities and is, importantly, relational in nature. The component parts are productive, creating new realities and working together as a whole for a defined time. Assemblage thus provides a framework for analysing how fluidity and exchangeability enable multiple functionalities and mutable connectivities, elements that need to be taken into consideration when discussing a translation in a material light. The notion of assemblage is supplemented by Actor-Network Theory which questions how things, people and ideas are connected and assembled; a “sociology of association” (Latour Citation2005). These central elements of relationality, the interaction with a physical environment, and the interplay between humans and non-humans form key discussions in material culture and will be applied to translations to determine how this analytical framework can result in novel insights in the field.

Another key term in this article is “practice” which will be employed to examine how “material practice” interlinks with religious translations, and how rituals and practices contribute to meanings and relationships. Traditionally, issues of practice and material culture revolved around practices of production and consumption (Miller Citation1987). The notion has since expanded and now encompasses a wider understanding of how practice engages with an object, ranging from production and consumption, to gifting and identity construction, with multiple discussions on how people accumulate, value, touch, revere, exchange and keep objects (Hicks and Beaudry Citation2010). The ritualistic use of objects by religions provides important insights into material culture expressed through structured practices (Nugteren Citation2019). Practice can thus be considered as the social processes through which the material becomes part of the religious experience, and this article will examine how translation interacts with religious practices, not just in public rituals but also in domestic engagements with objects. Sensory encounters and phenomenological engagements with the translation process and product add further dimensions to the materiality and practices of translations, while the participatory and communicative functions of practice as well as the unstable, changing nature of practice over time also need to be addressed.

There are of course many different approaches to material culture, ranging from object-oriented to new materialism, and these approaches often diverge on understandings of the human-object nexus. Some argue that objects gain their meaning through their engagement with people, while others propose the importance of object-based agency.Footnote4 It is not, however, within the scope of this article to valorize one approach over another, but rather to suggest how these approaches that have been integrated into the “toolkit” (Prown Citation1982) of material culture scholars, could likewise be a useful addition to the toolkit of those who analyse translations. In order to examine how this toolkit might be utilized in relation to religious translations, this article will first consider the material geographies of one visual representation of religious translation, and, secondly, will apply various material culture analyses to a specific religious translation.

Images of materiality: St. Jerome in his study

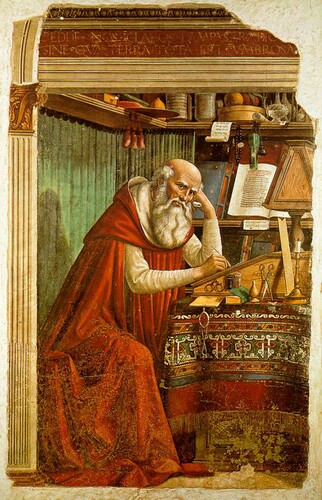

Visual depictions of the materiality of religious translation are an instructive point of departure for considerations of the interaction between translation, religion and objects. During the Renaissance, there was a vogue for paintings and engravings featuring one of the best-known figures in religious translation, St. Jerome, at work in his study. These artworks show the famous translator of the Bible surrounded by material objects related to the translation process. In Ghirlandaio’s fresco St. Jerome in his Study (1480), the saint is at work at his desk while in the midst of objects such as open books, a letter, reading glasses, inkwells, scissors and a candle holder (see ). There are two inkwells in the image, red for rubricating and black for writing, and the drops of ink near the inkwell point towards the immediacy of the work at hand. On the cartouches are Greek and Hebrew letters indicating the multilingualism of the activity.

Figure 1. Domenico Ghirlandaio, St. Jerome in his Study (1480), fresco, Church of San Salvatore di Ognissanti, Florence.

An analysis of this image reminds us of the physicality of the practice of translation and the materiality of textual production. It also reminds us of how the translator is part of a material world, where the medium interacts with the ideational. Recent work by Outi Paloposki and others has drawn attention to the translator’s desk, to the clutter that encroaches on their work: source text editions, dictionaries, reference works and previous translations in a variety of languages (Paloposki Citation2019). It is argued that these objects carry meaning and affect the way that translators think and work, thus impacting the translation process. Many other artistic representations of St. Jerome in his study from this era also signal the material practice of translating: for example, in a woodcut from the Malermi Bible of 1490, Jerome is seen using a rotating book wheel, a device where multiple books could be opened and rotated for consultation while the writer worked at his desk (Thornton Citation1998, 58). This object points to the use of multiple sources in the process of translating the Bible and highlights the need for constant and immediate references in multi-layered textual composition. Antonello da Messina’s St. Jerome in his Study (c. 1475) similarly depicts the translator at work surrounded by texts, many of them opened out for ease of consultation. Antonio da Fabriano’s painting of the same subject (1451) includes multiple texts and parchments on the saint’s desk, while also giving prominence to the saint’s hands involved in the physical process of writing and consulting. In many of the images, paper markers can be seen inserted into books for easy reference and a corpus of multilingual texts surrounds the translator for scholarly use, highlighting the philological activity of Jerome. The many items on and around St. Jerome’s desk remind us of the interaction between objects and the process of translation. These are the very tools and objects that make translation and communication possible; as Michael Cronin (Citation2003) and Karin Littau (Citation2016) remind us, without tools, translation does not exist.

These depictions of Jerome also highlight the perceived interplay between the material and the immaterial, the human and the divine in the creation of a religious translation. The images of Jerome feature the saint at work, generally in a moment of divine inspiration or contemplation. In the mingling of shafts of light and contemplative poses in the setting of a study, the act of translation comes across as an ethereal moment that is embedded in a workplace, replete with material objects which will give form to the translation. The imagery combines action and reflection, reason and faith, humanity and divinity, materiality and immateriality. Religious translation is conceptualized as an act of divine inspiration firmly based in a material world. The combination of the human and divine, the word made flesh, is a central tenet of Christianity and it is therefore unsurprising to see the combination of the material and the immaterial in images of Jerome. The translator is not merely a tool of divine will, an instrument channelling the word of God, he is actively engaged in materializing the religious message. He is a person who has to put in the hard graft to deal with multiple texts, languages and versions. This is an intertwined world with many components: as Allison Burkette observes, “Not only should the message and the media be considered discursive partners, the translator also is part of the same ongoing cycle of co-creation” (Citation2016, 320). The imagery of the religious translator at work reminds us that a focus on the materiality of translation is not to the exclusion of the human agent, instead, it is to place the human at the centre of a materialized reality.

The agency of translation thus needs to be viewed as distributed across “assemblages of subjects and objects, human and nonhuman actors” and human agency understood as entangled with the agency of materiality (Hazard Citation2018, 794). This is to acknowledge the human as the producer of the translated text, but also to recognize the entangled agency that enables textual production, where, for example, translators, printers, booksellers, paper and ink suppliers, authors of dictionaries and reference guides, are all part of this intertwined material world. Furthermore, it is to recognize the agency of things in themselves, which are not just bound in a constant subject-object dialectic, but instead impact on human translation practice. Much research in material culture has traditionally revolved around the study of human agents and their creation of, or interaction with, objects. In recent developments, however, there has been a tendency (evident also in Littau [Citation2011, Citation2016]) to return to the object itself and to discuss its own agentive nature, rather than merely seeing it as an extension of human activity. Termed “new materialism”, this approach argues that material things have a range of capacities that go beyond the human sense of knowing and that things must be considered in themselves, and not always positioned in relation to their impact on human concerns (Hazard Citation2013, 64). Scholars propose that things wield an agency that can shape human practice and culture (Fowler and Harris Citation2015) and attempt to tease out the implications of binding objects in a dialectic with humans. An application of this approach to the Ghirlandaio fresco acknowledges the role of the saint in the creation of the translation, but also asks how the tools he had at his disposal affected the translation he produced.

In analysing the image of the religious translator at work, it is also useful to take a step outside of the “frame” and to think of the artwork itself as a material object. The fresco was commissioned by the Vespucci family for the church of Ognissanti in Florence. The position of Ghirlandaio’s fresco within a public space in a church had a very performative function in respect of the visual politics of religious translation: it placed Jerome’s translation work in a vaunted and prominent position and reflected his popularity in the Renaissance (Simon Citation2019, 160–170). Indeed, Jerome’s expertise in Hebrew, Greek and Latin, his philological zeal and his reformist and challenging translation work appealed to the values of Renaissance humanism and resulted in public demonstrations of his valorization such as the Ghirlandaio fresco. The elements of the fresco which speak to these humanist values (including the multilingual volumes) are thus in dialogue with the external context of Renaissance Florence. Another important aspect of Ghirlandaio’s fresco is that it was created in tandem with, and located opposite, a fresco by Botticelli which depicted St. Augustine at work in his study.Footnote5 It is impossible to analyse the materiality of Ghirlandaio’s work without making reference to this companion piece as, in Latourian terms, they are an assemblage of component parts. The image of St. Jerome in his study is very much in conversation with that of St. Augustine, a man with whom he had a lively correspondence from ca. 394 to 419 AD. During this exchange of letters, the two men discussed Jerome’s translation of the Old Testament from Hebrew, with Augustine questioning departures from customary traditions of translation and asserting the authority of the Septuagint. In the correspondence, Jerome’s adherence to a philological methodology in his translation work created a debate on differing approaches to religious translation, and the discussions between the two Church Fathers can therefore be positioned at the foundation of Western translatology (Robinson Citation1992). The relationship between the two saints was closely connected with (and grounded in) translation, and the artistic works depicting the two men, individually at work in their studies, have been described by one art historian as being “so intimate that they illuminate each other” (Stapleford Citation1994, 69). The dialogue that existed between the two men in life thus continues in their artistic representations in the church of Ognissanti.Footnote6

Moving “outside the frame” to consider the material situation of the work effectively allows us to turn “from theology of pictures to an anthropology of visual practice representation” (Belting Citation2016, 235) and add additional layers to our understanding of the fresco. Although it is not within the scope of this article to fully explore the agentive function of the frescos in creating “assemblages of meaning” (Morgan Citation2018), the form and context of the image, with the intertwining of Renaissance and humanist ideas on translation and textual practice, must be acknowledged as participatory elements in the materiality of the image. The relationship of the Ghirlandaio fresco to Botticelli’s depiction of Augustine, to the church of Ognissanti, and to the context of Renaissance Florence therefore elaborates how the form of the image, its relationality and positioning are constituent elements of its material layers.

To return “within the frame” of Ghirlandaio’s fresco, the image is replete with objects including a cardinal’s hat, fruit, an hourglass, a necklace, a purse and vases. Is this fresco merely for art historians to analyse? Or does it also have something to say to translation scholars? In many of the images of Jerome at work, he is given the clothing and paraphernalia of a cardinal, even though he never held this position in the Catholic Church. Does posthumously conferring on Jerome the garb of cardinal add to our understanding of the value placed on religious translation in the Renaissance? The setting of the image of Jerome in a study, a private space filled with objects to support the translation activity, creates a relationship with the translated object and points to the material conditions of translation. The objects in Jerome’s study cannot of course be considered as historical documentation of how he worked, rather they point to the Renaissance conceptualization of a religious translator. Although some images of Jerome feature him working in the desert, leading an ascetic life (for example, Giovanni Bellini’s painting of the saint), most Renaissance artists preferred to depict him in his study. Was this because the act of translation could not be conceptualized as happening without material props? What does the positioning of the objects in the image tell of Renaissance attitudes to translation? Anne Coldiron has recently termed translation scenes and portrayals of translators as “paratextual visibility” (Citation2018), and these representations both materialize the translator and also spatialize the translation process, incorporating the “material environment of translation” which, in the words of Littau, is “a matter of micro-geographies, bringing together physical, social and mental spaces” (Citation2019, 369). Thinking of the religious translator and the religious text in material terms encourages us to consider the textual, scribal and physical strategies of religious translation and how these were conditioned by technology available to the writer, their spatial working environment and the geographies of their materialities.

Material entanglements

Moving from the geographies of a visual representation of translation, I will now use the example of a single religious publication to illustrate possible material readings of the translation and how such an approach can result in alternative engagements with the text. The text I have chosen is a translation from French into English by Mary Sadlier of Abbé Mathieu Orsini’s Life of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Mother of God which was published in America in 1872.Footnote7

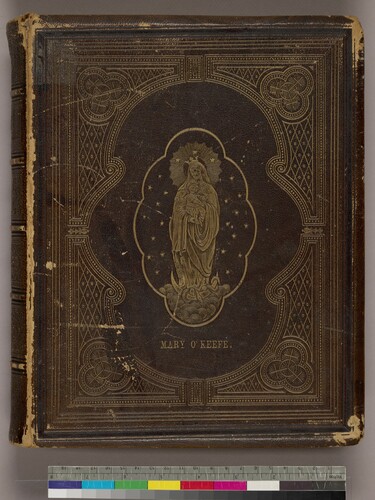

Within studies of material culture, one form of analysis focuses on the object as a thing in itself, highlighting its physical features, investigating elements such as structure, texture, age and so forth. Taking its lead from book historians who regularly examine the materiality of the text to further understandings of the book’s function and position in society, an object-centred analysis pays attention to the book in its totality, revealing important insights relating to paper, binding, typography, layout, finishing, ornamentation, images and print form. The 1872 Orsini translation published by D. & J. Sadlier was bound in leather in full calf over wooden boards with embossing in gilt of geometric design. It had a cameo of the Madonna with a child on the upper board and a Latin cross on the lower board. It had gilt paper edges, raised bands on the spine, text within a lined border, a colour illustration to the title page and also illustrations throughout the book.Footnote8 I will be discussing a copy of this translation which was personalized through a supra libros on the upper board of the leather with the owner’s name, Mary O’Keefe (see ). This refined book was clearly designed to be a prized, durable possession. The inscription on the exterior of the book transformed the mass-produced object into a unique personalized possession, opening up alternative meanings and uses for the translation. Questions about the book’s material appearance and constitution thus lead to expanded questions about interactions with the object, its function and the practices associated with its existence.

Figure 2. External cover of Life of the Blessed Virgin Mary (1872) personalized with the name Mary O’Keefe. Reproduced from the original held by the Department of Special Collections of the Hesburgh Libraries of the University of Notre Dame, Indiana, USA.

When studying a translation as an object, another layer of analysis must be added which involves a comparison between the materiality of the original text and that of the translated text. Are both printed in the same format? Has the finishing changed? Are the illustrations the same? Is it still targeted at the same reading public? The original French text by Orsini was published in France by Félix de Boisadam in 1837 and numbered over 700 pages. It had an attractive binding in half calf, tan, with raised bands, gilt and blind decoration to the spine; there was marbled paper to boards and blue speckled edges. Like the Sadlier translation, this text was materially packaged as a refined product, designed for durability and domestic use. Even when the text was translated into a new environment in America, it still bore the hallmarks of a high-end product. From a translation studies perspective, a material approach highlights the importance of considering changes in the physical form of the translated work and it is insightful to examine how the book is materially altered as part of its translational re-elaborations, how “transformissions” form part of its afterlives.Footnote9

The publication of the translation in such a deluxe edition provides additional information on the value and the use of the book, and the elaborate and expensive finishing made it an important physical object which could occupy a prized position in the home. The translation was more than just a religious work to be read; it also had a display function and a value linked to its personalization. As Jules Prown outlined (Citation1982), it is important to highlight the different levels of value that can be linked to material objects, ranging from the intrinsic value of the object to the value linked to the object’s function. For religious translations, this value is multi-layered, encompassing the physical value of an object, and also the spiritual and participatory value it derives from a concomitant religious community.

Practice, meaning and engagement

Through their use and associated practices, objects can gain meaning and value as they are charged intellectually and affectively, and framed within relational systems. The religious translation can be attributed meaning and sacred qualities, and it can also be positioned in a network of emotion and feeling that emerges from ritualistic or valued practices. How believers engage with the objects is as important as what the objects do in themselves, necessitating a focus on how the object is used and reused, cherished or lost, prized or forgotten. Indeed, Lynne Long has proposed that what makes a text holy is how people use it, the status they give it and the significance it has for them (Citation2005, 14). What people do with the object activates meanings and significations that do not primarily or exclusively reside in the object itself (Morgan Citation2008, 228). Material culture reminds us to examine not only the presence and circulation of objects but also the importance of the practices and rituals relating to the objects. To use Arjun Appadurai’s phrase, the “social life of things” is a natural and necessary consideration that stems from the interweaving of actors, makers, receivers in the creation, circulation and reception of things (Citation1986).

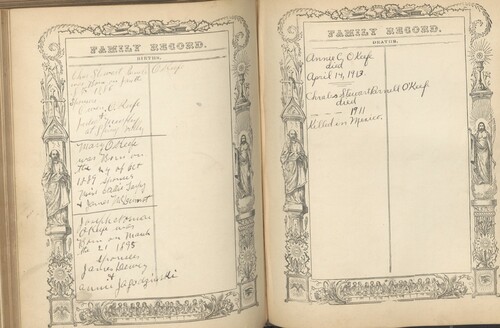

A religious translation can thus be seen as an object that creates meaning through its interaction with people, their practices and environments. When examining the object, the sensory experience of owning the text must also be considered: these were books to be held while praying, to be read in a domestic setting, to be placed in a prominent position in the household. The material dimensions of the object draw attention to the need to consider tactile significance: for example, the 1872 edition of the Sadlier translation contains pages inside the book that were left blank for family records; these included pages with headings for marriages, births, deaths and miscellaneous, and embellished religious borders surrounded the spaces for the lists (see ). The handwritten insertions in the text modified its existence and gave rise to added practices linked to the object. By memorializing family events within the pages of the book, it was no longer merely an object containing words to be read, instead, it was an object inviting haptic involvement. Although the attention of scholars is often drawn to the textual features of a book, the blank spaces are also significant. The inscription and memorializing of personal moments of Catholic ceremony within pages of the Life of the Blessed Virgin Mary left material traces of domestic life and ritual. The interplay of things and practices is an integral part of the complexity of the religious experience with profane objects obtaining sacred dimensions through their use in ritualized moments of religious activity. In this context, it is useful to think of how materiality encourages participatory practices where the physical cues and features of a text prompt an engagement that moves beyond the reading of words (Blatt Citation2018; Jenkins et al. Citation2013). The material traces in the Orsini translations show how, particularly for religious texts, interaction with the work can encompass textual engagement and also a participatory dimension of devotion and piety.

Community, identity and the object

Many scholars, drawing on approaches proposed by Appadurai (Citation1986), view objects as symbols or signs which reveal or signify underlying beliefs. It is also argued that the cultural values which are embedded in and transmitted by an object can provide insights into cultures and societies that produced and used the objects (Berger Citation2009). In this context, it is useful to question how religious translations contributed to the creation of meaning and identity for those within the religious group, and what the texts tell us about the culture that used them. The Life of the Blessed Virgin Mary (1872) was a French work translated by an Irishwoman and published in America, and as such is a product of the networks of global Catholicism. Ownership of this work was a marker of belonging to this wider community spread across geographical and linguistic borders; it was a badge of identification and a statement of religious consumerism and participation. The devotional works translated for the Catholic community in America can be seen as aids in forming a sense of identity, facilitating participation in the global flows of a transnational religion. Objects help people to individuate, differentiate, and identify, while allowing humans to situate themselves in space and time (Auslander Citation2005, 1019): the translation and circulation of The Life of the Blessed Virgin Mary enabled this process, with the translated book serving as a tangible trigger for creating meaning and identity.

Religion relies on material objects and practices to impact on and structure a sense of identity, to provide a tangible sensory experience of religious meaning. The phenomenological approach to religious material culture places much emphasis on the human sensory experience and the importance of things as part of the lived experience of humans (Morgan Citation2010). The study of material culture and religion demands a re-evaluation of objects and a recognition of their function in evoking emotion, attachment and identity. Many different meanings can converge in one object: a religious book can be viewed as a badge of identity, a transnational link, a status symbol, a family heirloom. With this pooling of significance in an object, it can encompass shared multiple and fluid meanings, often non-linear in nature, ranging from personal domestic meaning to objectified social meaning. The value of the religious translation gains additional significance when it is situated within a community which is shaped through its use of objects, practices and sensory experiences; shared devotional activities; rituals which inform the emotions that are attached to objects and bind people in their religious identities.

Materiality, empirical questions and assemblages

While the values and cultural significance embedded in objects are important, a material analysis also necessitates concerted attention to empirical questions such as How many copies of the translated work were in circulation? How many forms of this object existed? How unique was it? How did it come into existence? A brief analysis of WorldCat reveals that Abbé Orsini’s original text, La Vierge: histoire de la mère de Dieu appeared in at least seven editions between 1837 and 1842, and is held by fifteen WorldCat member libraries worldwide. In comparison, the English translation appeared in ninety-five editions between 1800 and 1986 and is held by 422 WorldCat member libraries worldwide.Footnote10 Although these figures relate only to WorldCat, they nonetheless give an empirical idea of how the translation had a different afterlife to that of the original with many different elaborations in new contexts.

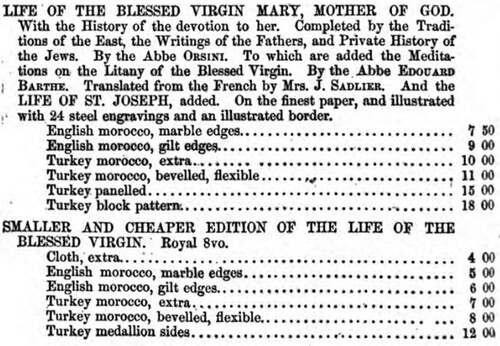

The variants of the afterlives of this work are not merely textual changes, they are also material re-elaborations or transmediations of the original book, encompassing a diversity of print and textual forms. Attention to these details of the book can tell us a great amount about how the text has been packaged for and used in the target culture. The study of religious translation must therefore take account of elements such as editions, print runs, packaging, prices, marketing and advertising. The actual translation of the Life of the Blessed Virgin Mary by Mary Sadlier did not change from the 1850s to the 1870s; however, in this period it was packaged and promoted in a variety of manners to attract additional readers. A study of the materiality of the text reveals the strategies used both to recruit readers and to impact the way the text was used. The Life of the Blessed Virgin Mary, for example, was offered to the public in many different formats, the copy that Mary O’Keefe owned and personalized was just one form of the text and there were many other options open to buyers with variations in finishes and prices as can be seen in advertisements for the book (see ). These reveal the different paths for the consumption of the translation and a variety of trajectories for the afterlives of the text. The diversity of publishing formats allowed for altered engagements with the object: small, cheap and portable versions could be held and used by a wide cross-section of the Catholic population, becoming domestic, personal objects; while deluxe editions could be displayed prominently and fulfil a more performative role.

Figure 4. Advertisement from the catalogue of D. & J. Sadlier, in Sadlier’s Catholic Almanac and Ordo, New York: D. & J. Sadlier, 1865, p. 4.

Bruno Latour’s Actor-Network Theory encourages us to pay attention to how objects relate to each other; how they gain meaning through proximity, and how they interact with their environment (Citation1996; Citation2005). For religious translations it is crucial that they are considered as embedded in a relational structure, and that the embodied effects of material culture are seen as networks or entanglements and not merely single objects. When analysing the Sadlier translation, it is therefore necessary that it is contextualized alongside the other objects with which it was sold and packaged. In the case of the Life of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the translation was not published on its own and was in fact bound together with other works: a translation by Sadlier of Meditation of the Litanies Blessed Virgin Mary by Abbé Edouard Barthe; a historical calendar of feasts of the Blessed Virgin, foundations and dedications of churches in honour of our Blessed Lady, and the litany of the Most Blessed Virgin, accompanied with meditations. The translation must be studied in dialogue with these other texts alongside which it was packaged. Rather than see an object as a single item or a standalone text, material culture encourages consideration of how the object is connected, produced and assembled and of how an examination of these aspects can reveal insights into different social experiences and models of circulation.

Publishers and sellers of religious translations in the nineteenth century did not just sell books, they also had a wide offering of religious objects such as prints, rosary beads and statues. For example, the catalogues of the Sadlier Company in America contained religious books and translations as part of a continuum of religious products both for domestic use and for public worship. Translated works were part of the material culture of nineteenth-century Catholicism, where church ornaments, pictures, vestments, building designs, rosary beads, music and church furniture circulated across national boundaries. During the changing patterns of domestic piety in this period, with greater emphasis on personal, standardized devotional practices, believers used printed aids and other props to attend to their devotional life as part of a ritualized process (Heimann Citation1995; Taves Citation1986). The value of the objects used in this context is much greater than their intrinsic value as they formed part of the ritualistic enactment of the religious devotion.

The study of material culture is often conceived as an inclusive practice where domestic and inconsequential objects share the stage with élite objects (Auslander Citation2005). In the context of religious translations, the focus on the material aspect helps move from élite institutional concerns to the mass production and consumption of religious texts, where meaning is not just confined to the text, but is also interactive, creating different forms of experience in the practices and use of objects. The analysis of the translated text and its materiality opens up the discussion of the values associated with that text. These values are multi-layered and can be linked to the object itself, to its function in a public or domestic setting, to its associated sacrality, and also to its links to a wider transnational community of believers. A study of the materiality of religious translations allows us to explore these layers of value by examining how they are embedded in or triggered by the object. As a religion communicates across languages, its practices are rooted in the material world, providing insights into identities, values and indices which are connected to this materiality of being.

Conclusion

Nowhere in this article have I discussed the translation strategies employed by Mary Sadlier in translating Orsini’s work; there is no mention of her faithfulness or otherwise to the original French text. There is also no discussion of the translator herself. This article has instead proposed that a material analysis of her published translation can offer different insights into the work than those provided by textual or biographical approaches. A material focus locates the object within its associated practices, assemblages and networks. To examine the materiality of religious translations is to examine their production, social function, aesthetic composition and consumption; for religious translations, materiality can provide a link between a text and its use in devotional practices. Isolating the text from the material culture that surrounds it disconnects the translation from the entanglement of social, institutional, and personal activities linked to the object. The benefits of this approach are multiple and not merely limited to insights relating to the translation brought about by a shift in focus from textuality to materiality. The study of religious translation in a material light can also provide insight into specific religions, illustrating how the religion itself is embodied, transformed and perpetuated by translation. The consideration of how religions deploy and respond to translations as material objects therefore can enhance both understandings of the translation itself and also how religious regimes of identity can be constructed through translation.Footnote11 The study of religious translation should therefore be accompanied by a study of the objects, spaces and practices surrounding the texts, and the act of translation itself considered, like St. Jerome in his study, as embedded in a material world.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anne O’Connor

Anne O’Connor is Senior Lecturer and Co-Director of the Emily Anderson Centre for Translation Research and Practice in the National University of Ireland, Galway. She is the author of Translation and Language in Nineteenth-Century Ireland: A European Perspective (2017) and is PI on the ERC-funded project Pietra: Religious Translation, the Catholic Church and Global Media: a study of the products and processes of multilingual dissemination.

Notes

1 Religious texts have been used haptically throughout history: one only needs to think of traditions surrounding the placing of hands on Bibles, and of making oaths while in physical contact with a religious text more broadly, to understand the centrality of this dimension. The focus in this article is on Christian texts and the broad focus on material translation in the Christian tradition is all the more appropriate given that in this religious tradition, the word “translate” has been used not just for the movement of words, but also the movement of relics and people.

2 For an overview of these intersections, see Colombo (Citation2019).

3 For a recent publication on how such a research approach could work in the field of digital religion, see Mandair (Citation2019).

4 For an overview of these approaches see, for example, Hazard (Citation2013), Hicks and Beaudry (Citation2010). See Saramifar (Citation2018) for an object-centred approach which calls for more agency to be attributed to the religious object.

5 The two works were originally even closer than their current positions: they were moved from the chancel to opposite walls in the nave of the church during the sixteenth century.

6 The interconnection is such that some have interpreted Botticelli’s work as a depiction of the moment when Augustine allegedly had a miraculous visitation from Jerome (Meiss Citation1970), an interpretation which has been subsequently challenged (Stapleford Citation1994). For more on visual representations of both Jerome and Augustine in this period, see Gill (Citation2012).

7 For analysis of cross-sections between the book history approach and translation studies, see Colombo, Ó Ciosáin, and O’Connor (Citation2019).

8 The first edition of this translation was published by D. & J. Sadlier, New York, in 1853, and a second edition of the text appeared in 1854. These publications coincided with the declaration of the Immaculate Conception and so were very topical in the world of Catholic publishing.

9 Coldiron has argued that transformission “asks us in particular to consider material textuality as a co-factor in translation, concomitant with verbal or linguistic factors” (Citation2019, 201). The notion of “transformission” and its applicability to early modern translations is elaborated in Belle and Hosington (Citation2019); Coldiron (Citation2019).

10 This is a rather reductive analysis of a messy afterlife of a text which existed in many languages, formats and editions, both in the original and in translation; the purpose here is merely to highlight different textual trajectories and possible quantitative implications in a material study of the translated text.

11 On how translations can contribute to construction of regimes of identity in religions, see Israel (Citation2019) and also the contributions to the Special Issue of Religion which that article introduces.

References

- Appadurai, Arjun. 1986. The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Auslander, Leora. 2005. “Beyond Words.” The American Historical Review 110 (4): 1015–1045.

- Belle, Marie-Alice, and Brenda M. Hosington. 2019. “Translation as ‘Transformission’ in Early Modern England and France.” Canadian Review of Comparative Literature/Revue Canadienne de Littérature Comparée 46 (2): 201–204.

- Belting, Hans. 2016. “Iconic Presence. Images in Religious Traditions.” Material Religion 12 (2): 235–237.

- Berger, Arthur Asa. 2009. What Objects Mean: An Introduction to Material Culture. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press.

- Blatt, Heather. 2018. Participatory Reading in Late-Medieval England. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Blumczynski, Piotr, and John Gillespie, eds. 2016. Translating Values: Evaluative Concepts in Translation. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Burkette, Allison. 2016. “Response by Burkette to ‘Translation and the Materialities Of Communication’.” Translation Studies 9 (3): 318–322.

- Coldiron, Anne E. B. 2015. Printers without Borders: Translation and Textuality in the Renaissance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Coldiron, Anne E. B. 2016. “Response by Coldiron to ‘Translation and the Materialities Of Communication’.” Translation Studies 9 (1): 96–102.

- Coldiron, Anne E. B. 2018. “The Translator’s Visibility in Early Printed Portray-Images and the Ambiguous Example of Margaret More Roper.” In Thresholds of Translation. Paratexts, Print, and Cultural Exchange in Early Modern Britain (1473–1660), edited by Marie-Alice Belle, and Brenda M. Hosington, 51–74. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Coldiron, Anne E. B. 2019. “Translation and Transformission; or, Early Modernity in Motion.” Canadian Review of Comparative Literature/Revue Canadienne de Littérature Comparée 46 (2): 205–216.

- Colombo, Alice. 2019. “Intersections between Translation And Book History: Reflections and New Directions.” Comparative Critical Studies 16 (2–3): 147–160.

- Colombo, Alice, Niall Ó Ciosáin, and Anne O’Connor. 2019. “Translation Meets Book History: Intersections. Special Issue.” Comparative Critical Studies 16: 2–3.

- Cronin, Michael. 2003. Translation and Globalization. London: Routledge.

- Cronin, Michael. 2013. Translation in the Digital Age. London: Routledge.

- DeJonge, Michael P., and Christiane Tietz. 2015. Translating Religion: What is Lost and Gained? London: Routledge.

- DeLanda, Manuel. 2019. A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 1980. Mille Plateaux. Paris: Editions de Minuit.

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 1988. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Editorial statement. 2005. “Introduction.” Material Religion 1 (1): 4–9.

- Engelke, Matthew. 2011. “Material Religion.” In The Cambridge Companion to Religious Studies, edited by Robert A. Orsi, 209–229. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fowler, Chris, and Oliver J. T. Harris. 2015. “Enduring Relations: Exploring a Paradox of New Materialism.” Journal of Material Culture 20 (2): 127–148.

- Gill, Meredith J. 2012. “Reformations: The Painted Interiors of Augustine and Jerome.” In Augustine Beyond the Book: Intermediality, Transmediality and Reception, edited by Karla Pollmann, and Meredith J. Gill, 59–94. Leiden: Brill.

- Hazard, Sonia. 2013. “The Material Turn in the Study of Religion.” Religion and Society 4 (1): 58–78.

- Hazard, Sonia. 2018. “Thing.” Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 16 (4): 792–800.

- Heimann, Mary. 1995. Catholic Devotion in Victorian England. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Hicks, Dan, and Mary C Beaudry. 2010. “Introduction: Material Culture Studies: A Reactionary View.” In The Oxford Handbook of Material Culture Studies, edited by Dan Hicks, and Mary C. Beaudry, 1–21. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hodder, Ian. 2012. Entangled: An Archaeology of the Relationships Between Humans and Things. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Houtman, Dick, and Birgit Meyer. 2012. Things: Religion and the Question of Materiality. New York: Fordham University.

- Israel, Hephzibah. 2011. Religious Transactions in Colonial South India: Language, Translation, and the Making of Protestant Identity. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Israel, Hephzibah. 2019. “Translation and Religion: Crafting Regimes of Identity.” Religion 49 (3): 323–342.

- Jenkins, Henry, Wyn Kelley, Katie Clinton, Jenna McWilliams, and Ricardo Pitts-Wiley. 2013. Reading in a Participatory Culture: Remixing Moby-Dick in the English Classroom. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Latour, Bruno. 1996. “On Actor-Network Theory: A Few Clarifications.” Soziale Welt 47 (4): 369–381.

- Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Littau, Karin. 2011. “First Steps towards a Media History of Translation.” Translation Studies 4 (3): 261–281.

- Littau, Karin. 2016. “Translation and the Materialities of Communication.” Translation Studies 9 (1): 82–96.

- Littau, Karin. 2019. “Afterword: Translation and the Histories and Geographies of the Book.” Comparative Critical Studies 16 (2-3): 365–374.

- Long, Lynne. 2005. Translation and Religion: Holy Untranslatable? Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Mandair, Arvind-Pal S. 2019. “Im/materialities: Translation Technologies & the (Dis)enchantment of Diasporic Life-Worlds.” Religion 49 (3): 413–438.

- Matthews-Jones, Lucinda, and Timothy Willem Jones. 2015. “Introduction: Materiality and Religious History.” In Material Religion in Modern Britain, edited by Timothy Willem Jones, and Lucina Matthews-Jones, 1–14, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- McDannell, Colleen. 1995. Material Christianity: Religion and Popular Culture in America. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Meiss, Millard. 1970. The Great Age of Fresco: Discoveries, Recoveries and Survivals. London: Phaidon.

- Meyer, Birgit, David Morgan, Crispin Paine, and S. Brent Plate. 2010. “The Origin and Mission of Material Religion.” Religion 40 (3): 207–211.

- Miller, Daniel. 1987. Material Culture and Mass Consumption, Social Archaeology. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Mitchell, Christine. 2010. “Translation and Materiality: The Paradox of Visible Translation.” Translating Media 30 (1): 23–29.

- Morgan, David. 2008. “The Materiality of Cultural Construction.” Material Religion 4 (2): 228–229.

- Morgan, David. 2010. Religion and Material Culture: The Matter of Belief. London: Routledge.

- Morgan, David. 2011. “Thing.” Material Religion 7 (1): 140–146.

- Morgan, David. 2016. “Materializing the Study of Religion.” Religion 46 (4): 640–643.

- Morgan, David. 2017. “Materiality.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Study of Religion, edited by Michael Stausberg, and Steven Engler, 271–289. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Morgan, David. 2018. Images at Work: The Material Culture of Enchantment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nida, Eugene A., and Charles R. Taber. 1969. The Theory and Practice of Translation. Leiden: Brill.

- Nugteren, Albertina. 2019. “Introduction to the Special Issue ‘Religion, Ritual, and Ritualistic Objects’.” Religions 10 (163): 1–13.

- Paloposki, Outi. 2019. “Tauchnitz for Translators. The Circulation of English-language Literature in Finland.” Comparative Critical Studies 16 (2–3): 161–179.

- Prown, Jules David. 1982. “Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method.” Winterthur Portfolio 17 (1): 1–19.

- Robinson, Douglas. 1992. “The Ascetic Foundations of Western Translatology: Jerome and Augustine.” Translation and Literature 1: 3–25.

- Saramifar, Younes. 2018. “Objects, Object-ness, and Shadows of Meanings: Carving Prayer Beads and Exploring Their Materiality alongside a Khaksari Sufi Murshid.” Material Religion 14 (3): 368–388.

- Simon, Sherry. 2019. Translation Sites: A Field Guide. London: Routledge.

- Stapleford, Richard. 1994. “Intellect and Intuition in Botticelli’s Saint Augustine.” The Art Bulletin 76 (1): 69–80.

- Taves, Ann. 1986. The Household of Faith: Roman Catholic Devotions in Mid-Nineteenth-Century America. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Thornton, Dora. 1998. The Scholar in His Study: Ownership and Experience in Renaissance Italy. Yale: Yale University Press.