?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This article focuses on the introduction of a new function for translation in a changing context of formal language learning in the Madras Presidency in nineteenth-century south India. Amongst this region’s multiple languages, the article considers language examination papers, examiners’ feedback, and preparatory materials in Hindustani, Tamil and Telugu to reconstruct two developments in relation to translation: first, translation as pedagogy, introduced as a key mechanism in the instruction and examination of languages, increased and made visible the scope of translation beyond the literary context. Second, competition based on translation abilities across diverging professions in the colonial domain promoted greater awareness of the changing distinctions between different language registers and varieties within languages. Paying attention to translation pedagogy undertaken for non-literary purposes is thus important in expanding current understandings of how translation evolved and functioned in colonial South India.

Introduction

Thomas Trautmann, in his introduction to The Madras School of Orientalism, calls for further engagement with the multiple projects of language learning, comparative philology and development of print that characterized scholarly activities at the College of Fort St. George (henceforth FSG) in early nineteenth-century Madras in south India: “This book is intended as an invitation to further research. … [on] topics the book was not able to include” (Citation2009, 21). This article responds to Trautmann’s “hope that others will extend the beginning that we have made” (6) by focusing on translation as a pedagogical tool. Building on his previous thesis (Citation2006) that Francis Whyte Ellis first developed the “Dravidian proof”Footnote1 within the scholarly networks of leading Indian and European scholars at Madras’s FSG, Trautmann’s stimulating edited volume (Citation2009) examines a range of changes in language learning, textual cultures and writing practices in South India across Tamil, Telugu, Sanskrit, Arabic, and Hindustani. Here, Trautmann and others convincingly demonstrate that a new grammar-oriented language teaching and learning programme developed at FSG, introducing significant transformation in these language cultures. The presence of translation, translators, and translated works is frequently alluded to which feature as implicit threads that run through several chapters, but translation is not foregrounded or critically analysed as a key mechanism by which languages were taught, learnt and examined for the first time. This article sets out to investigate the function of translation that underpinned the new focus on grammar in the Madras Presidency.Footnote2 Its aim therefore does not lie in examining translations as end products, or in comparing translations with source texts or other translations to arrive at an authentic and uncorrupted “original” text or to serve philological study. Instead, its intention is to draw attention to a new use for translation as an effective mechanism in a changing language-learning environment, where it functioned as a tool to gauge not just language proficiency across multiple language registers but also to evaluate an individual’s competency in various professional routes available in colonial south India. Candidates’ ability to translate introduced new measures of competencies along various career paths. This focus on an aspect of the cultural history of translation opens up current discussions on translation in India, where predominantly literary translation alone is critically engaged with when studying translation.

The principal languages of this region were Sanskrit, a classical language, associated with north India and commonly referred to in south India as vaṭamoḻi (or northern language) and two regional languages of south India, Tamil and TeluguFootnote3 which dominated FSG scholarly activities in this period. While languages were not traditionally acquired through translation in south India, it became the dominant mechanism for language instruction, examination and systems of rewards from this period. There has been some recent scholarly interest in bilingual education introduced in the colonial period (Sridhar and Mishra Citation2017; Sengupta Citation2018; Vennela and Smith Citation2019) but none take the role of translation into account in their analyses.

This article examines translation’s function as a pedagogical tool in serving different colonial fields – administrative, military, educational and missionary – from the early nineteenth century onwards. Bernard Cohn’s (Citation1996, 16–56) “language as command” argument highlighted that the appropriation of Indian languages worked to present the British as rulers of India, where language teaching aids and manuals successfully constructed “the image of the Englishman in India as the one who commands, who knows how to give orders and how to keep the natives in their proper place in the order of things through practical, not classical, knowledge” (41). Cohn notes further that since “all languages had a grammar, the commentaries on Indian languages could be turned into tools to enable the sahibs to communicate their commands and gather information” (53). As mentioned earlier, Trautmann (Citation2009), other authors contributing to his volume (including Venkatachalapathy and Raman) and Mantena (Citation2005) develop this argument in relation to Tamil and Telugu philology, specifically colonial re-workings of grammars with a range of evidence drawn from or associated with FSG. While there is no doubt that a command over the grammatical structures of Indian languages did indeed play a crucial part in conceptualizing language as command for the British in India, this article argues that this specialist knowledge of language grammars was repeatedly tested and proven through translation. As I will elaborate later, this introduced new contexts where translation could be deployed and therefore presented a new function for translation in a multilingual context. Moreover, while the ability to translate accurately across languages served as a means for primarily testing their knowledge of specific languages, more importantly, translation presumed to be an “objective” pedagogical tool was used to ascertain the suitability of candidates as competent civil servants, teachers, surgeons, missionaries and church ordinands. Once translation was widely mobilized as a pedagogical tool, it was available not only to the British but also to Indians who wished to progress along similar career paths, as we shall see from the evidence relating to language teachers and church ordinands.

Transitions in language learning

Before investigating the introduction of translation in language learning from the early nineteenth century, it would be appropriate to consider if and to what extent translation had played a part until then within the south Indian educational system. Curiously – since this appears to be an anomaly in the multilingual context of south India – translation did not traditionally function as a pedagogical tool in language learning. Evidence found so far indicates that languages were learnt through immersive methods. The typical pattern of language learning amongst the literati was that the high-caste (e.g. brahmin or vellala) boy learnt the more colloquial registers of the vernacular, let us say Tamil or Telugu, at home until he was seven or eight. He was then sent off to the local tiṇṇaippaḷḷikkūṭam (school run by a single teacher), a Saivite mutt (monastery) or for one-to-one lessons with a pundit (scholar) to learn Sanskrit and/or literary registers of Tamil or Telugu. From the pundit, he learnt to memorize entire texts (starting with verse lexicons, then grammars, and finally tackling literary or sacred texts) and repeat them orally with the correct pronunciations, inflections, and intonations. A significant component of study was memorizing generative rules, which lead to the formation of a correctly inflected word. When it came to writing these texts down, he would use the Nagari or Grantha script to write the Sanskrit text.Footnote4 Vocabulary would not always be a problem, either, because each vernacular language, including Tamil and Telugu, had incorporated modified Sanskrit words. The main challenge might have been the grammar: both inflection and syntax. But the pundit would have addressed this issue. Current evidence suggests that students were not expected to “translate” between a known and newly acquired language but treated each language, Sanskrit, Tamil or Telugu, as separate.Footnote5 This system maintained diglossia by offering intensive training to young scholars in reading, reciting, and composing in the literary registers of either language. Equally, distinction was maintained between the colloquial, domestic registers of languages learnt at home and the high literary registers of the same languages learnt from the pundit. The resultant diglossia continued well into the nineteenth century within the Madras Presidency. Satthianadhan (Citation1894) when reconstructing the history of education in the Madras Presidency finds the British Collector of Bellary, A. D. Campbell’s report on indigenous schools at the end of the eighteenth century “most valuable information”. Campbell comments on the levels of diglossia between books in verse used in Telugu and Canarese schools in the District and the distinctly different “dialect” used in conversation or business:

The alphabets of the two dialects are the same, and he who reads one, can read, but not understand the other also. The natives therefore read these (to them unintelligible) books, to acquire the power of reading letters in the common dialects of business, but the poetical is quite different from the prose dialect which they speak and write. (in Satthianadhan 1894, 4)

Nevertheless, despite the number of scholar-teachers well versed in more than one language and its registers, and presumably able to teach their students new languages through translation, it appears as if translation in much of south India was not conceptualized as a tool for the effective teaching and learning of languages. Hartmut Scharfe points out that

Sanskrit grammatical terminology was used generously by some Tamil grammarians. But even there, in the presence of authors with bilingual competence, there is no evidence of instruction in the other language; the native Tamil speaker, if he happened to be a brahmin, would have learned Sanskrit in his early school years, probably by the direct methods, i.e. by listening and imitating. (Citation2002, 311)

In the subcontinent, pundits, grammarians and poets had not emphasized translation processes or products in terms of equivalence or accuracy to a source text. Instead, translation was conceptualized rather loosely as one amongst a diversity of literary practices that drew on a range of existing textual traditions across languages offering opportunities to display poetic genius. Tellingly, while Sascha Ebeling draws attention to the composite workings of text memorization, modes of composition and the public performance of texts as essential components of a “poet’s ability to compose verses himself or to comment on other poets’ works” (Citation2010, 85), he does not refer to translation as one of these practices. However, more fluid forms of literary translations did exist, responding to and repeating “initiating texts” (Israel Citation2019, 396), “re-accenting and possibly multi-accenting” texts (Orsini Citation2018, 63) but not always theorized or critically commented on in terms of whether equivalence is or ought to be achieved across languages. This is despite strict and elaborate grammatical rules on how to incorporate individual words from languages perceived as extraneous (for instance, Sanskrit into Tamil). An exception lies with the key Tamil grammar, , from the third century BCE where unusually translation is listed in a discussion on how different textual categories relate. Nirmal Selvamony (Citation2014, 178) points out that the

distinguishes two categories of texts, where the secondary texts (vaḻinūl) – ranging from compilation, exposition, elaboration, synopsis and, significant for the discussion here, translation (moḻipeyarttal) – are meant to be “based on the primary” (mutaṉūl) textual category. Selvamony argues that although there are no clear instructions regarding faithfulness, there is an expectation for secondary texts to be read in close relation to primary texts. However, since sharper distinctions are not drawn between translation and other forms of engaging with texts, there is space for a fluctuating range of textual engagements with primary texts. Multilingual poets did not translate to always faithfully imitate for a new linguistic community but instead to extend their literary repertoire. Here the relationship between texts is multi-directional and polyvalent rather than linear,Footnote6 with few accompanying instructions on how to theorize this relationship. Hence, it is possible to argue that texts initiated long, multilingual, multi-textual and multi-modal repetitions (including performances through dance or oral re-tellings, paintings and friezes) of a theme or narrative which were not exact or equivalent copies, and as Brian Hatcher (Citation2017) maintains regarding the Bengali context, blurred lines between commentary, imitation and translation.

However, this largely adaptable approach to translation in literary contexts was to change in south India from at least the late eighteenth century. One of several factors for this change can be attributed to alterations introduced in the way languages began to be taught within colonial institutions from the late eighteenth-century onwards. For translation to work as the rendering of “equivalences”, Lisa Mitchell (Citation2005) has argued, languages had to be considered at least in theory “equal” and “parallel”. Mitchell (Citation2005, Citation2009) contends that until the nineteenth century specific languages in south India were associated with particular functions, tasks and social spaces (ranging from the ritual, courtly, judicial, to poet’s conventions, domestic or the marketplace).Footnote7 This changed by the early twentieth century to a conceptualization of several equal languages, where “anything that could be said in one language could be said equally effectively (if not as elegantly) in any other language” (Mitchell Citation2009, 160). Far from translations being experienced as new retellings of stories or topics already known to an audience, English colonial officials saw translation as a way to convey information not yet known to a new audience (182). Languages, Mitchell (Citation2009) concludes, came to be understood as discrete and autonomous, parallel objects of knowledge, divorced from context and content, and as independent mediums which had important repercussions in developing linguistic identities in twentieth-century south India.

The comparative, philological study of Indian languages undertaken by European scholars promoted such interest in translating across languages and grammatical structures in earnest. Trautmann (Citation2006, Citation2009) has argued the importance of this new focus on grammar and philological study in the development of the idea of “the Dravidian proof”.Footnote8 Tamil or Telugu grammars, prescribing strict grammatical rules for usage, had not traditionally been utilized for primary language learning, but used by established scholars (Mitchell Citation2009), or were memorized to cultivate memory rather than to cultivate languages and largely to “facilitate verse composition” (Raman Citation2012, 114–115). There was a significant change at FSG where instead, “[l]anguage study at the College was strongly oriented toward grammar, so that the head masters taught Sanskrit, Tamil, Telugu, and English grammar to the Indian students” (Trautmann Citation2009, 9) aspiring to train as language teachers, which shaped their own teaching of civil servants:

In many ways the Dravidian proof, to which they contributed, was the coming together, in colonial Madras, of Indian, vyakarana-based grammatical knowledge of, at a minimum, Sanskrit, Tamil and Telugu, and the historical orientation of the European language analysis of the day. (9)

Translating on the career path

The notion that a good working knowledge of at least one of the languages of India was important for British officers, civil servants and missionaries was advanced in several contexts, including sometimes as a matter of policy, which for instance led to the institution of FSG. In the history of Christian missions, learning Indian languages to translate and function effectively in the southern regions had an even longer history, with Jesuits learning Tamil and Sanskrit from the sixteenth century (Zupanov Citation2005), and with German Lutheran and British Protestant missionaries learning Tamil from the early eighteenth century for the purpose of translating (Israel Citation2011). This interest widens to other fields from the early nineteenth century. Trautmann (Citation2006, Citation2009) has argued that the activities of FSG set the groundwork for learning south Indian languages, eventually leading to the establishing of a “Madras School of Orientalism” that presented an incipient challenge to the Calcutta School, and which was later fully developed into a Dravidian linguistics by Robert Caldwell (Citation1856). Several scholars focussing on the College’s significant role in developing Tamil philology and print history in this period have likewise examined the intellectual and cultural importance of the College’s Tamil headmasters and scholars, focusing on their social and ideological profiles (Venkatachalapathy Citation2009), that they were in a position to decide which texts to teach British scholars and civil servants (Ebeling Citation2009, 236), and which ones to edit, translate and print (Blackburn Citation2003; Rajesh Citation2011, Citation2013). While they all draw attention to the translation activities that the Tamil scholars engaged in, their interest lies primarily in how translation furthered Tamil philology, Tamil textual and print histories and indigenous knowledge construction. Taking this scholarship as its point of departure, this article contends that the pursuit of commensurability through academic translation exercises and testing not only introduced different ways of learning Indian languages but also instrumentalized translation for new pedagogical purposes, advancing new measures of competencies in a changing world, and ultimately promoted the problematic notion of translation as equivalent rather than fluid transfer.

Preparing for civil service

As Trautmann (Citation2006, Citation2009) has shown, the Court of Directors of the East India Company, then governing significant territories in south India, decided in the early 1800s that British officers arriving in India should gain competent knowledge of at least two Indian languages in order to be able to function effectively in the India Civil Service. For this purpose, FSG was set up in 1812 in Madras following the model of the College of Fort William established in Calcutta in 1800. Founded by Francis Ellis of the Madras Civil Service, the college was set up to train East India Company officials in “native languages”. There was increasing emphasis at the turn of the century on the study of Indian languages at these first government collegesFootnote9 established in India from the early nineteenth century onwards as primarily language-training institutions for fresh batches of British civil servants.

While each junior civil servant was expected to choose to study one of several regional languages (Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, Kannada or Marathi) and one trans-regional language, either Sanskrit, Hindustani, Persian or Arabic (Appendix Citation1833, 537) in the early years of the College there are several references to the inability of the College Board to appoint what they term “competent teachers” amongst the pundits. Amongst “other defects in the present system of studying the native languages”, was listed “the want of elementary books in the native dialects … [and] the want of competent teachers in all the languages”.Footnote10 Given the enormous importance ascribed to Civil Servants’ acquiring Indian languages, it is surprising that the College did not invest further in appointing competent teaching staff. Trautmann argues that

[t]his general lack of competence was due to poor pay and the uncertainty of employment … The prospect of continuing to earn … [a] small pay was inversely proportional to their exertions in teaching, for when the students became proficient in the language, the teachers were dismissed and their pay came to an end. (Citation2006, 124)

Despite these several misgivings regarding the competence of native pundits to teach languages using translation methods and Trautmann’s (Citation2006, 125) argument that “the institution that the Government had created for language instruction was virtually useless”, one can only assume that there were at least a handful of pundits who did succeed in both teaching through translation and in translating textbooks. After all, we would not have records from 1813 onwards of British junior civil servants successfully passing language exams based on translation exercises had it not been for the ability of some pundits at least to transition to these new teaching methods. Besides, their growing translation and printing activities in the decades immediately after the founding of the College, for which there is firmer evidence (Blackburn Citation2003), belies the claims of the “incompetent” pundit. Apart from teaching languages at the College, the pundits translated or composed bilingual texts in the various languages taught. Satthianadhan (Citation1894, 37) offers us evidence from the records made available to him by the Director of Public Education of what was expected of teachers at the College: “Among the duties proposed for the vernacular superintendent was the preparation and supervision of translations of approved English works into the vernacular languages, and of the publication of an improved series of vernacular books”. This will have introduced the translation of texts for practical purposes as part of a new grammar-translation engagement with language learning.

Published examination results of the FSG from 1814 onwards (in Examination Results (ER) Citation1814–Citation17) and up to at least 1845 show not only which languages students were taught each year but that they were required to demonstrate their expertise in the languages of their choice through their ability to translate. Junior civil servants were expected to be able to translate from the Sanskrit or Hindustani and a regional language such as Tamil or Telugu into English and vice versa. In final examinations they were meant to complete exercises in translation in both directions and were set oral exercises to interpret between languages: “In the Tamil examination, we directed the conversation of the students to a variety of subjects either connected with the Revenue and Judicial systems of administration of India, or having reference to common dealings and familiar intercourse with the Natives” (ER 1815, 9). It appears from examiner comments that while colloquial registers and dialects were accepted during oral examinations (in response to the observed diglossia in social interactions), more formal and literary styles were expected of written translations. Further, in the study of a second language, “it is required … that the scholar should be able to read and translate papers of moderate difficulty, and generally that he should be competent to transact in it public business” (ER 1817, 36). It appears that translation exercises continued to feature in Civil Service examinations for much of the nineteenth century.

From detailed reports on candidates taking language examinations at FSG, we can reconstruct the significance translation held as a primary tool for testing language acquisition. Year upon year from 1813 onwards, published bi-annual examination results remark on approximately twenty officer’s ability to translate. This includes written translation exercises in both directions between an Indian language paired with English, as well as oral translation exercises. For instance, “Mr Harrington has so mastered the principles of Tamil … as will enable him to communicate freely with natives of all degrees of learning, and largely to avail himself in his future official life of every source of information that may offer to his enquiries” (ER 1815, 28). Oral translation exercises required extempore responses. In the examiners’ remarks, there is a noticeable tension between the expectation of fluent, idiomatic translation and a demonstration of the translated text’s “closeness” to the set text. In most cases, it is those who translate with both “ease and correctness” who are accorded the greatest accolade. A Mr Edward Bannerman “made an uncommonly rapid advancement in Tamil” in the 1817 examination, which is evidenced in his

translation of a difficult Tamil paper into English … generally very accurate; the sense of a few words only, and those not of frequent use, having been misunderstood. His version into Tamil was very creditable, and in conversation, he was fluent, idiomatic and correct in no ordinary degree (ER 1817, 37–38)

The translations undertaken, written or oral, were expected to be both accurate and idiomatic, without any reflection on the apparent contradiction in such expectations, although now more than familiar to the scholarly debate within the modern discipline of translation studies. However, it is important to note that the category “idiomatic” recurring in the evaluation of translation at FSG, indicates an expectation that examinees recognize differences between written and oral registers within each language, as well as respond in the correct register suited to specific hypothetical scenarios they were set. While one candidate was able to interpret “with ease and fluency the most difficult Cutchery paper”, another could converse “on all common subjects” but was found to be “deficient in technical terms and idiomatic expressions” (ER 1815, 12). “Idiomatic translation” was thus a category mobilized to check officers’ ability to match specific language registers to specific contexts of use.

Preparing for military service

Military officers too were required to demonstrate a knowledge of Indian languages through translation competence since they commanded multilingual regiments comprising Indian soldiers. Crowell (Citation1990, 264–265) points out that although by 1837, language qualifications had become “mandatory for staff employment”, with language textbooks provided free of charge by FSG and a munshi appointed by each regiment, it is almost impossible to judge the “effectiveness of this language study”. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that like civil servants, officers and surgeons in the Madras military establishment were expected to prepare for examinations in the trans-regional Hindustani and were tested by means of translation: they were to be trained in translating between vernacular languages and dialects both in writing and in extempore spoken “orders”. Edward Cox’s training manual, The Regimental Moonshi (Citation1847, henceforth Moonshi), intended primarily for instruction in the Madras Presidency, is a bilingual text enumerating a variety of hypothetical scenarios that an army commanding or medical officer may find himself in. It is worth noting that the Hindustani term munshiFootnote11 which refers to the traditional figure of the language scribe (of lower social status than the scholar-teacher) is replaced here by a translation manual entrusted with the task of training British officers. Cox (Citation1847, iii–iv) starts with a set of regulations that clearly state the importance of learning Indian languages for civil, military and medical officers and indicates that the “course of Examination for each Class” involves translation: “Translating from Hindoostanee, Tamil, or Teloogoo, into English, in writing … plainly written and of easy style” as well as “translating extemporally [sic.] any paragraph from the Sections of Standing Orders noted in the margin”. Officers preparing for examinations would have had to navigate different scripts to translate phrases between the two languages, although this is not commented on.

The 84-page long Part I of the Moonshi starts with a series of imperatives that an officer may throw at his Indian subordinates in a variety of putative circumstances. Some sixty-three pages with parallel Hindustani (in Arabic script) and English lines read like a catechism, set questions followed by set responses, from everyday conversational exchanges involving ordering of meals, shopping, discussion of the character of an underling, to imaginary medical examination interviews. Part II of the Moonshi, comprising templates for letter-writing and a manual for field and platoon exercises, appears only in Hindustani in Arabic script, with the occasional footnote in English. Presumably by this stage the student will have mastered sufficient Hindustani to read the Arabic script, needing only culturally relevant explanations in footnotes. The text marks with an asterisk all military “commands” (for instance, “fire”, “advance”) that were always to be given only in English, although presented here in the Arabic script, in keeping with the rest of the text. The presence of these English command words in the Hindustani text hierarchically distinguish the role and status of each language in the military context. The Moonshi ends with a 35-page bilingual “vocabulary of words in common use”, arranged in the English alphabetical order. Each English entry is offered a Hindustani equivalent in Roman and Arabic scripts, and in many cases, several Hindustani synonyms. Examinees would thus have had to negotiate multiple languages, scripts and registers when preparing for this one language exam. This bilingual textbook, incorporating multiple scripts demonstrates the significance of the role written and oral translation came to play in identifying the right register of command over various categories of “natives” – domestic servants, sepoys and medical patients.

Preparing for missionary service

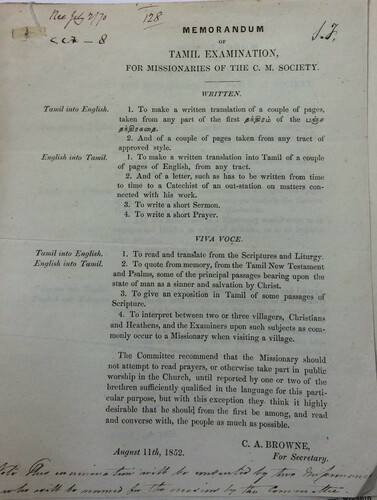

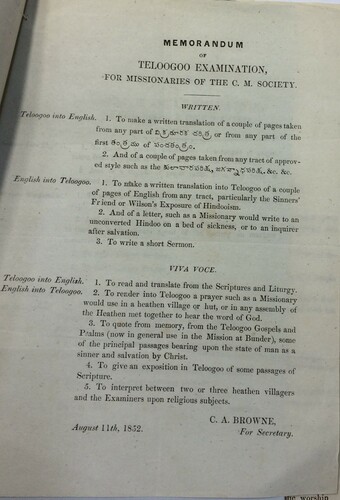

The Church Missionary Society (CMS) archives reveal that translation exercises were also integral to language examinations conducted for both its missionaries and ordinands. Examination papers in Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam and Hindustani, uncannily parallel the Civil Service examinations, including written and viva voce categories. Candidates for the missionary examination were typically expected to translate portions of the Bible, tracts, prayers, sermon, and letters to catechists (see ).Footnote12

Figure 1. Memorandum of Tamil Examination, for missionaries of the Church Missionary Society (1852) comprising written and viva voce translation in both directions (CMS Archives, Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham, CMS/B/OMS/C/I2/O 206/724).

Figure 2. Memorandum of Teloogoo Examination, for missionaries of the Church Missionary Society (1852) comprising written and viva voce translation in both directions (CMS Archives, Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham, CMS/B/OMS/C/I2/O 206/724).

Figure 3. Memorandum of Malayalim [sic] Examination, for missionaries of the Church Missionary Society (1855) comprising written and viva voce translation in both directions (CMS Archives, Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham, CMS/B/OMS/C/I2/O 206/724).

![Figure 3. Memorandum of Malayalim [sic] Examination, for missionaries of the Church Missionary Society (1855) comprising written and viva voce translation in both directions (CMS Archives, Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham, CMS/B/OMS/C/I2/O 206/724).](/cms/asset/89af4f10-ee28-4643-8a8e-73f9976f3d1a/rtrs_a_1922308_f0003_oc.jpg)

A notification dated October 1862 states that aspiring chaplains in the Madras Presidency wishing to work with the Church of England or Established Church of Scotland were required to pass language examinations by proving their familiarity with both written and spoken registers of the languages they had studied through written translation exercises and spoken dialogue with examiners and “with one or more natives”.Footnote13 The Tamil (1852) and Malayalam (1855) examination papers clearly state that while it was desirable for missionaries to “converse with” people in everyday settings, they should not attempt to participate in public worship in church or read prayers “until reported by one or two of the brethren sufficiently qualified in the language for this particular purpose”.Footnote14 The presence of colloquial registers of Tamil in the translated Bible had already been a source of embarrassment and conflict since the late eighteenth century (Israel Citation2011). Here again, we glimpse an effort to keep lower, “improper” registers of languages out of formal ritual settings, to lend Christian worship appropriate gravitas. Candidates were meant to indicate through their selection of fitting language registers and idioms for preaching and in conversation, how they would distinguish between “Christian” and “Heathen” natives, thus nuancing their linguistic interactions further. These instructions strongly echo FSG committee recommendations for junior civil servant and Cox’s rationale for preparing a manual for military officers and surgeons discussed in the previous sections.

The CMS archives also contain entire examination scripts of six Indian ordinands from the Bombay Presidency.Footnote15 Apart from being tested on church history, the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England, the church catechism, Prayer Book, and St. Paul’s epistles in Greek, ordinands were expected to translate from Greek into English, and English hymns, sermons and letters into Marathi and vice versa.Footnote16 Although similar examples of ordinands taking examinations in the Madras Presidency have not yet come to light, it is likely that CMS will have developed a uniform policy for Indians wishing to be ordained in all the territories it was active in, including nineteenth-century Madras Presidency. Translation once again features as a key mechanism by which Indian candidates too are assessed in their suitability as ordinands. Such intensive training given to Indian ordinands in translating different types of Christian literature suggests that the perception in CMS circles at least was that true knowledge of the new faith and its scriptures could best be acquired through the process of translating them. Commenting on the Bombay Presidency, Veena Naregal (Citation2018, 198) has argued that translation was fundamental in setting up social sciences in the Indian university system:

Translation … formed the very basis of the instructional method adopted for the other disciplines as well. Translation and colonial pedagogy thus worked through producing persistent slippage between what was sought to be taught, the language through which it was to be transmitted, and the new learning skills/subjectivity to be inculcated.

Translation rewards

Civil servants who passed language examinations with credit could look forward to a number of awards that were granted, from monetary prizes, to lucrative posts in the Company’s Public, Judicial and Revenue Departments as well as to high profile promotions within the Indian Civil Service. The “Proclamation” of the College (May 1, 1812) stated:

A reward of 1,000 pagodas will be granted to every student whom the Board of Superintendence may report as having acquired a competent knowledge of Sanscrit, or as being qualified to transact public business, without the aid of an interpreter, in any one of these languages, viz. Tamil, Teloogoo, Canari, or Malayalim. (Appendix Citation1833, 606)

… their translations exhibit an intimate acquaintance with the structure and idiom of these languages, in which they converse with great propriety and correctness on any subject. We beg leave to report them qualified for employment in the public service; and in recommending them to the favourable consideration of the Government, we submit that each of them has made good his claim to the honorary donation of 1000 Pagodas. (ER, 1817, 42)

Besides civil servants, military officers and chaplains too were offered pecuniary rewards: “Every Chaplain … who may pass a satisfactory examination in two of the languages abovementioned … shall receive an honorary reward of Rupees 1,000.”Footnote19 There was an important rationale underlying this system of rewards and penalties. Colonial policy was based on the conviction that an ability to converse directly with Indians and being “qualified to transact public business without any aid from an interpreter in one language” (Appendix Citation1833, 538) across various professions was essential for the transaction of any business, civil, military or spiritual. This policy may have been further fostered by the belief that Indians were incapable of conceptually understanding faithfulness in translation, made incompetent translators or worse, were untrustworthy interpreters who deliberately sabotaged source texts and the translation process.

Conclusion

How can we interpret these different language examination materials that relied so heavily on the efficacy of the translation process? Tejaswani Niranjana (Citation1999, 21) highlighted translation as “a significant technology of colonial domination” through her deconstruction of hegemonic colonial translations. This article opens up the colonial domination argument by detailing the instrumentalization of translation in South India’s multilingual context in the first half of the nineteenth century, and the multiple repercussions this had. Despite a complex multilingual cultural history, which had entailed translation across multiple languages, genres and writing traditions, the ability to translate had not featured until then in south India as an important criterion by which to learn languages or to measure competence in any professional field, including the literary. Authors of what we may now consider translations were celebrated foremost as poets rather than translators. On the one hand, Trautmann (Citation2001, 379) has argued that interaction between European and Indian scholars began a “conversation between Indian and European traditions of studying language” and that it was a “site of a breakthrough moment” in philology, “for India had a tradition of language study that was far in advance of that of Europe, and had reached an astonishing state of sophistication very early on”. On the other, the development of the “grammar-translation” approach in language teaching in nineteenth-century Britain is well-documented in most histories of language teaching.Footnote20 The coming together of these two approaches to studying languages in early-nineteenth century Madras introduced a new function for translation in south India that had held little currency until then.

Comparing the previous Islamicate knowledge system of the Mughals with that of the British colonial system, Blain Auer (Citation2018, 44) draws “a contrast between translation as transmission of knowledge and translation as standardization and language study”, with the latter, in his opinion, working in the service of nationalism and colonialism. At first glance, the effects of British colonial use of translation does seem preoccupied merely with standardization and language study, but a fuller consideration of primary sources reveals debates and policies put in place for a much deeper engagement with translation as transmission of knowledge. Cohn (Citation1996), Trautmann (Citation2009) and others have shown that language-learning at this point was portrayed as the foundation on which effective governance of Indians was erected but as this article has argued, the principal mode of demonstrating that mastery of Indian languages was through translation. Venkatachalapathy (Citation2009, 119) has made the case that it is “a grasp of the structure of language, as exemplified in grammar, which transforms ‘the command of language into the language of command’” but his analysis, and Cohn’s (Citation1996) earlier argument, can be extended to include the ability to translate as a mechanism that proved in practical and visible terms the ability of civil servants or military officers to transform “command of language” into the “language of command”. Civil servants, military officers and surgeons were ranked according to their ability to translate between languages and their ability to distinguish between language registers within a language. The evaluation of these officers’ ability to govern depended, amongst other factors, on their ability to translate accurately and idiomatically, paying careful attention to differences in register and dialect. Equally, when missionaries and ordinands displayed expertise in translating accurately, that is, in distinguishing between the written and spoken or between various language registers, they did not prove translation competence as much as their ability as church ministers to effectively govern their parishioners’ spiritual lives.

Translation as a formal pedagogical tool for learning languages, serving to effectively teach and examine candidates in a variety of fields of knowledge – from language acquisition for administrative purposes to training for effective communication in the military, medical or missionary fields – had important consequences in south India. Whatever the present debate on the efficacy of translation in language learning, in early-nineteenth-century British territories of South India, there was apparently little uncertainty in imperial circles at least regarding its value as a pedagogical tool in learning new languages and as a testing mechanism in language examinations. None of the documents recording examination results comment critically on the efficacy of translation as a transparent testing mechanism. The ability to translate was promoted unreflexively as an “objective” and “neutral” tool, serving to separate those who could translate “accurately” and “idiomatically” from those who could not, to measure competency in a number of professions unrelated to literary writing. Importantly, in all three instances, candidates were expected to successfully translate texts and interpret spoken dialogue, proving their ability to distinguish between written and spoken registers. Despite no established standards for measuring either accuracy or idiomatic choice or proof that translating between a language pair did indeed produce effective colonial administrators, military officers or church ministers, translation was perceived as offering a deceptively transparent, practical and powerful mechanism by which young men, British and Indian, could be selected and progress within new structures of powerful colonial institutions. Although no evaluation of translation as an effective measure was conducted, and as has been shown so far, expectations of accuracy remained entangled with more fluid forms of translation, it was the notion of translation as faithful transfer of meaning that was emphasized and popularized in south India from then on.

In a period characterized by rapid linguistic change in south India, translation served to refract languages along a vertical continuum within each language, as much as facilitate moves across languages increasingly perceived as “parallel” along a horizontal axis. Translation as pedagogy functioned to clarify and maintain distinctions between the various registers, introducing new ways of navigating a social order that was by this time mutating in its multilingual make-up in response to wider cultural changes. The ability to select an appropriate register in each Indian language, matched with suitable vocabulary to distinguish between written (the high literary), administrative (the humble “cutcherry”), church ritual (new but respectable prose and verse) and spoken (the colloquial oral) registers brought a self-conscious pragmatism to translation in a variety of professional fields that elide the current scholarly preoccupation with aesthetic considerations of high-value poetry in “fluid” translation. Rather than arguing that pre-colonial fluid or creative conceptualizations of translations changed to “faithful translation”, this article highlights the importance of studying the fluctuating functions of translation over time. Paying attention to translation undertaken for non-literary purposes is important in expanding present understandings of how translation has historically functioned in South Asia and to what extent it served to maintain, intermingle or challenge linguistic registers and varieties. Further, such instances of translation in cultural history also have the potential to contribute to more nuanced insights into changing perceptions of the role of translation in language-learning beyond South Asia. One avenue for further exploration is to investigate whether translation-based assessment regimes of language learning that were elaborated and tested in relation to South Asian languages impacted attitudes to translation in language-learning and testing in imperial Britain from the late nineteenth-century onwards. However, a study of such “blow-back” effects is best undertaken on another occasion.

Acknowledgements

I thank the two anonymous peer reviewers for their comments, the article is more focused as a result. I also thank Piotr Blumczynski for his comments and careful editing of the article. I am grateful to colleagues who have given feedback at seminar presentations and to friends A. R. Venkatachalapahy, Nirmal Selvamony and Sharada Nair for reading earlier drafts of this article. However, I remain solely responsible for any errors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Hephzibah Israel

Hephzibah Israel is senior lecturer in translation studies, University of Edinburgh. She researches translation and religion, literary translation and translation practice in South Asia. She is the author of Religious Transactions in Colonial South India (2011). She has guest edited (with Matthias Frenz) the special issue of Religion, on “Religion and translation” (2019) and (with John Zavos) a special section on Indian traditions of life writing and religious conversion, “Narratives of Transformation” (2018) for South Asia. She is series editor of the newly launched book series, Routledge Critical Studies in Religion and Translation.

Notes

1 Trautmann (Citation1999, Citation2006) first proposed and developed the overarching term “Dravidian proof” to denote Ellis’ scholarship on and argument that the languages of south India were historically related to each other as a distinct language family not derived from Sanskrit as had until then been believed by eighteenth-century, Calcutta-based Orientalist scholars.

2 An administrative sub-division or province of British India that included much of south India, with the emerging port “city” of Madras as its winter capital.

3 Both are regional languages with long literary traditions. They have distinct scripts and largely different grammars and vocabulary. Centuries of co-existing with Sanskrit however meant that there had been a fair amount of mutual transfer.

4 Except that in the Tamil context, Sanskrit needs extra characters that are not used in Tamil and Tamil uses some characters that are not used in Sanskrit.

5 I thank Dermot Killingley for confirming this.

6 Bassnett and Trivedi (Citation1999) use the image of the “banyan tree” to characterize such multivalent relations between texts.

7 See Vatuk (Citation2009) for languages used by the Tamil Muslim community; and Mitchell (Citation2005, Citation2009) for the Telugu context.

8 See also Venkatachalapathy, Ebeling and Raman in Trautmann (Citation2009).

9 In 1806, an East India College was set up in Haileybury with the intention of offering training to prospective candidates in “Oriental languages” as part of their education in Britain before they travelled to India. When the College of Fort St. George was set up six years later, Haileybury continued to function in parallel.

10 Letter from Madras, 10th January 1812. In Appendix Citation1833, 603.

11 For a detailed analysis of the nature and changing status of the munshi in south India, please see Raman (Citation2012).

12 Memorandum of Tamil Examination for Missionaries of the C. M. Society (1852), Memorandum of Teloogoo Examination for Missionaries of the C. M. Society (1852) and Memorandum of Malayalim Examination for Missionaries of the C. M. Society 1855, CMS/B/OMS/C/I2/O 206/723.

13 Rules for the Examination of Chaplains (Citation1870, 284).

14 Ibid.

15 An administrative subdivision of British India located in Western India, with Bombay as its capital.

16 Examination papers of six Indian catechists in training, dated October 1850. Unpublished manuscript. CMS archives, University of Birmingham, CMS/C I3 061 346 E.

17 “We entirely concur in the propriety of the Rule proposed by your president that no Servant of the Company shall be appointed to the Offices of a Collector or judge until he is reported by a Committee, which we trust will be strict in its examinations, to have made a proficiency in one at least of the Native Languages” (Madras Despatches, Citation1805, IOR/E/4/896).

18 Examination Results, December 1814; Proclamation by the Madras Government, 1st May, 1812 in Appendix 1833, 606–607.

19 Rules for the Examination of Chaplains (Citation1870, 285).

20 For a comprehensive overview of the main recent research, see McLelland (Citation2018).

References

- Appendix to the Report from the Select Committee of the House of Commons on the Affairs of the East India Company. 16th August 1832, and Minutes of Evidence. Vol. 1. Report from the Select committee on the affairs of the East India Company: With Minutes of Evidence in Six Parts, and an Appendix and Index to Each. 1833. London: Printed by order of The Honourable Court of Directors by J. L. Cox and Son.

- Auer, Blain. 2018. “Political Advice, Translation, and Empire in South Asia Author(s).” Journal of the American Oriental Society 138 (1): 29–72.

- Bannerman, E. 1828. “College Examination, College of Fort St. George.” The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British India and its Dependencies XXV: 232–233. London: Parbury, Allen & Company.

- Bassnett, Susan, and Harish Trivedi. (1999) 2002. “Introduction: Of Colonies, Cannibals and Vernaculars.” In Postcolonial Translation: Theory and Practice, edited by Susan Bassnett and Harish Trivedi, 1–18. London: Routledge.

- Blackburn, Stuart. 2003. Print, Folklore, and Nationalism in Colonial South India. New Delhi: Permanent Black.

- Caldwell, Robert. 1856. A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian or South-Indian Family of Languages. London: Truner & Co.

- Cohn, Bernard. 1996. “The Language of Command and the Command of Language.” In Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge: The British in India. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Cox, Edward Thomas. 1847. The Regimental Moonshi: Being a Course of Reading of in Hindustani, Designed to Assist Officers and Assistant Surgeons on the Madras Establishment Preparing for the Examination Ordered by Government, [With an appendix]. London: Wm. H. Allen & Company. Electronic resource on Archive.org.

- Crowell, Lorenzo M. 1990. “Military Professionalism in a Colonial Context: The Madras Army, Circa 1832.” Modern Asian Studies 24 (2): 249–273.

- Ebeling, Sascha. 2009. “The College of Fort St. George and the Transformation of Tamil Philology During the Nineteenth Century.” In The Madras School of Orientalism. Producing Knowledge in Colonial South India, edited by Thomas Trautmann, 233–260. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Ebeling, Sascha. 2010. Colonizing the Realm of Words: The Transformation of Tamil Literature in Nineteenth-Century South India. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Examination Results, 1814–17. College of Fort St. George (Madras, India), Madras: College of Fort St. George. WEB Resource. Accessed 14 April 2021. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=Q49eAAAAcAAJ&pg=GBS.PP7.

- Extract from the Rules of the College of Fort St. George, and for the Superintendence of Public Instruction: Passed by the Honourable the Governor in Council, 13th July 1827 – Madras, 1st August 1827. 1833. In Appendix to the Report from the Select Committee of the House of Commons on the Affairs of the East India Company, 16th August 1832, and Minutes of Evidence, 536–539. London: The Honourable Court of Directors.

- Hatcher, Brian A. 2017. “Translation in the Zone of the Dubash: Colonial Mediations of Anuvada.” The Journal of Asian Studies 76 (1): 107–134.

- Israel, Hephzibah. 2011. Religious Transactions in Colonial South India: Language, Translation and the Making of Protestant Identity. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Israel, Hephzibah. 2019. “Translation, Conversion and the Containment of Proliferation.” Religion 49 (3): 388–412.

- Madras Despatches. British Library, Public 23 October–19 November 1805, IOR/E/4/896.

- Mantena, Rama Sundari. 2005. “Vernacular Futures: Colonial Philology and the Idea of History in Nineteenth-Century South India.” The Indian Economic and Social History Review 42 (4): 513–534.

- McLelland, Nicola. 2018. “The History of Language Learning and Teaching in Britain.” The Language Learning Journal 46 (1): 6–16.

- Memorandum of Tamil Examination, for Missionaries of the C.M. Society (1852); Memorandum of Teloogoo Examination, for Missionaries of the C.M. Society (1852); Memorandum of Malayalim Examination, for Missionaries of the C.M. Society (1855) in Outlines of Courses in Tamil, Hindustani and Malayalam Examinations for CMS Missionaries, CMS Archives, Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham, CMS/B/OMS/C/I2/O 206/724.

- “Miscellaneous. College of Fort St. George.” The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British India and its Dependencies, XVII, 200–201. London: Kingsbury, Parbury & Allen. 1824.

- Mitchell, Lisa. 2005. “Parallel Languages, Parallel Cultures: Language as a New Foundation for the Reorganisation of Knowledge and Practice in Southern India.” The Indian Economic and Social History Review 42 (4): 445–467.

- Mitchell, Lisa. 2009. Language, Emotion and Politics in South India: The Making of a Mother Tongue. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Narayana Rao, Velcheru. 2004. “Print and Prose: Pandits, Karanams, and the East India Company in the Making of Modern Telugu.” In India’s Literary History: Essays on the Nineteenth Century, edited by Stuart Blackburn and Vasudha Dalmia, 146–166. New Delhi: Permanent Black.

- Narayana Rao, Velcheru. 2016. Text and Tradition in South India. New Delhi: Permanent Black.

- Naregal, Veena. 2018. “Translation and the Indian Social Sciences.” In A Multilingual Nation: Translation and Language Dynamic in India, edited by Rita Kothari, 196–221. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Niranjana, Tejaswini. 1999. Siting Translation: History, Post-structuralism, and the Colonial Context. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Orsini, Francesca. 2018. “Na Hindu Na Turk: Shared Languages, Accents, and Located Meanings.” In A Multilingual Nation: Translation and Language Dynamic in India, edited by Rita Kothari, 50–69. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Percival, Rev. P. Letter dated 16, February 1857, “Letter from Professor of Sanscrit and Vernacular Literature, Presidency College; to H. Fortey Esq., B.A. Acting Principal of the Presidency College,” 319–321. In Appendix C, Correspondence Relating to the Education Despatch of 19 July 1854, in Parliamentary Papers. 1859: sess. 2: v. 24: pt. 2. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044106491665?urlappend=%3Bseq=336.

- “Proclamation by the Madras Government, 1st May, 1812,” William Thackeray, 1833. In Appendix to the Report from the Select Committee of the House of Commons on the Affairs of the East-India Company, 16th August 1832, and Minutes of Evidence, 606–607. London: Printed by Order of The Honourable Court of Directors by J. L. Cox and Son.

- Rajesh, V. 2011. “Patrons and Networks of Patronage in the Publication of Tamil Classics, c. 1800–1920.” Social Scientist 39 (3/4): 64–91.

- Rajesh, V. 2013. Manuscripts, Memory and History: Classical Tamil Literature in Colonial India. New Delhi: Cambridge University Press India.

- Raman, Bhavani. 2012. Document Raj: Writing and Scribes in Early Colonial South India. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Rules for the Examination of Chaplains and Assistant Chaplains in the Native Languages. 1870. CMS archives, Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham, CMS/B/OMS/C/I2/O 206/723 [print], 284–285.

- Satthianadhan, S. 1894. History of Education in the Madras Presidency. Madras: Srinivasa, Varadachari & Company.

- Scharfe, Hartmut. 2002. Education in Ancient India. Leiden: Brill.

- Selvamony, Nirmal. 2014. “Authorship in the Light of Tinai.” In Culture and Media: Ecocritical Explorations, edited by Rayson K. Alex, S. Susan Deborah, and P. S. Sachindev, 170–188. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Sengupta, Papia. 2018. Language as Identity in Colonial India Policies and Politics. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sridhar, M., and Sunita Mishra. 2017. Language Policy and Education in India: Documents, Contexts and Debates. London: Routledge.

- Trautmann, Thomas. 1999. “Hullabaloo About Telugu.” South Asia Research 19 (1): 53–70.

- Trautmann, Thomas. 2001. “Dr Johnson and the Pandits: Imagining the Perfect Dictionary in Colonial Madras.” The Indian Economic and Social History Review 38 (4): 375–397.

- Trautmann, Thomas. 2006. Languages and Nations: The Dravidian Proof in Colonial Madras. Berkeley: University of California.

- Trautmann, Thomas. 2009. The Madras School of Orientalism: Producing Knowledge in Colonial South India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Truschke, Audrey. 2012. “Defining the Other: An Intellectual History of Sanskrit Lexicons and Grammars of Persian.” Journal of Indian Philosophy 40 (6): 635–668.

- Vatuk, Sylvia. 2009. “Islamic Learning at the College of Fort St George in Nineteenth-century Madras.” In The Madras School of Orientalism. Producing Knowledge in Colonial South India, edited by Thomas Trautmann, 48–73. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Venkatachalapathy, A. R. 2009. “Tamil Pandits at the College of Fort St. George.” In The Madras School of Orientalism. Producing Knowledge in Colonial South India, edited by Thomas Trautmann, 113–125. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Vennela, R., and Richard Smith. 2019. “Bilingual English Teaching in Colonial India: The Case of John Murdoch’s Work in Madras Presidency, 1855–1875.” Language & History 62 (2): 96–118.

- Županov, Ines G. 2005. Missionary Tropics: The Catholic Frontier in India (16th-17th Centuries). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.