ABSTRACT

This article aims to investigate how written and spoken texts can be translated, or resemiotized, in different semiotic modes in a multimodal museum space. The inclusion and exclusion of certain semiotic resources in the museum space is further discussed through the process of de/recontextualization. The data were collected from a bilingual exhibition in the Opium War Museum in Dongguan, China. The two research questions are: (1) How have the semiotic resources of the exhibition been translated from one form into another? and (2) Why were certain semiotic resources chosen over others in this exhibition? The findings illustrate how source texts can be resemiotized, and ultimately reveal how the diplomatic discourse on “China’s foreign friends” seems to motivate the process of de/recontextualization in the Opium War Museum.

The exhibitive function of translations

As part of the move away from text-bound linguistic approaches to translation, multimodal translation studies began to emerge in the late 1990s as a strain of research to investigate how translated texts interact with other semiotic modes in multimedia texts; its focus was primarily on audiovisual translation but has gradually expanded to include other types of multimodal events. Multimodality can be defined as “the use of several semiotic methods in the design of a semiotic product or event” (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2001, 20). The museum exhibition as a multimodal event can include, for example, visual semiotics such as the building itself, three-dimensional objects and two-dimensional images; verbal semiotics such as object labels, leaflets and audio guides; and audio semiotics such as music and sound installations. In multimodal analyses, researchers identify how different semiotic modes are combined and interact with each other to co-construct meaning. A semiotic mode can be understood as “a socially and culturally shaped resource for making meaning” (Bezemer and Kress Citation2008, 6). A semiotic approach to translation has helped expand our thinking in various ways. Most importantly, understanding that language alone cannot construct meaning requires the translation researcher to bring other semiotic modes into the discussion, and this view of text as a meaningful multimodal whole challenges some long established (and debated) concepts in translation studies, such as equivalence and translation shifts. If language is only one component in the co-construction of the meaning(s) of a multimodal event, then a comparative translation analysis that focuses on the verbal mode alone will fail to capture any changes that occur on other modal levels in the transfer from source to target (con)text. This understanding forces the translation researcher to reconsider the relationship between the source text (ST) and the target text (TT) in light of the intermodal relationships they create with other semiotic resources.

As a much newer strand in research on multimodal translation studies, work on museum translation shows not only that translated texts interact with other semiotics in an exhibition space, including visual, audio, gestural, etc., but also that they can function as a form of visual semiotics that contribute to meaning construction in multimodal spaces like museums (Neather Citation2008, Citation2012; Liao Citation2018a). Liao (Citation2018b, 48) further proposes that the exhibitive function is one of the crucial roles that translations perform in a multilingual museum space. While previous studies on written texts in museum exhibitions tend to regard them as an interpretive tool to help visitors better understand the accompanying visual displays, this study argues that in museums, written texts can also be presented as material objects for users to view; or, as will be shown later, they may not be intended for reading at all. One example that illustrates the exhibitive function of translation can be found in the “Temporary Centre for Translation” museum exhibition, held in the New Museum in New York in 2014. In this exhibition, the translated texts were not there to facilitate an understanding of the accompanying exhibit but were intended to be viewed as objects in their own right.

This article holds the view that, in museums, all written texts, whether translated or not, are on display in the three-dimensional space just like any other material object. Written texts are physically present; they can be viewed and are therefore on exhibit themselves. Furthermore, just as any other artifact in an exhibition must undergo an institutional process of selection (what is to be included) and design (how is it to be displayed) before entering the exhibition space, so too do translations. Therefore, a discussion on translation in museums that focuses only on linguistic content fails to capture their function as an inseparable component of an exhibition.

An emphasis on language as the only component of translation excludes other potentially meaningful discussions of translation activities that take place in much more visually dominated, intercultural events, such as museum exhibitions. Therefore, in the next section, I would like to extend the discussion from how texts are translated to how a text (understood as a multimodal sign) may be exhibited as a translation, while focusing on which semiotic elements of the ST are chosen to be translated and why. Specifically, this study aims to answer two questions: (1) How have semiotics been translated from one resource into another in the museum space? (2) Why are some semiotics chosen over others to do certain things for a museum exhibition? The first question draws on the theoretical concept of resemiotization (Iedema Citation2003) to examine exhibition units with STs that were originally produced as printed texts in their source context, but were then presented, or resemiotized, in a creative combination of different semiotic modes in the museum space. The second question engages with the discussion of de/recontextualization (Ferguson Citation1996, 176) in museum studies to discuss why some STs were selected and others were excluded in this exhibition.

This case study is based on the permanent exhibition in the Opium War Museum in Dongguan, China. The exhibitions in this museum consist of an exciting combination of modes—object labels, text panels, audio guides, subtitling, and the use of wax figures as part of the displays. In this regard, this multimodal exhibitive space provides rich data for the multimodal analysis of translations in museums.

A semiotic framework for translations and museums

To further pursue the question of how translations are displayed in museum exhibitions, the semiotic reading of translation proposed by Kaindl (Citation2020, 58) becomes a useful point of reference: translation is to be understood as “a conventionalised cultural interaction in which a mediator transfers texts in terms of mode, medium, and genre across semiotic and cultural barriers for a new target audience”. This definition moves away from the fixation on linguistic equivalence between the ST and the TT and addresses multiple modes of realization. The material dimension of different semiotic modes is what is often neglected in translation studies when the meaning of languages is discussed but not their material “affordances” (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2001). Affordance refers to what a mode can potentially express and represent because of its material features and its conventional uses in a social-historical context (Jewitt and Henriksen Citation2016, 148). For example, a handwritten document copied and placed inside a display case will carry a different meaning than one typed on a computer, laser-printed, framed in an acrylic cover, and exhibited as a wall panel, even though their linguistic content may be the same. Littau (Citation2016, 93) also challenges the “print-minded assumption” that is prevalent in translation studies and highlights the fact that translations are remediated and negotiated between media with different material affordances. Materiality is a particularly prominent feature for museum texts; as Blunden (Citation2016, 1) contends, the “museum remains in essence a place that offers an experience of material culture that is physical, sensory, visceral, emotional, even spiritual”. In other words, the language product in a museum is not only for visitors to read, but also to see, to feel and even to touch.

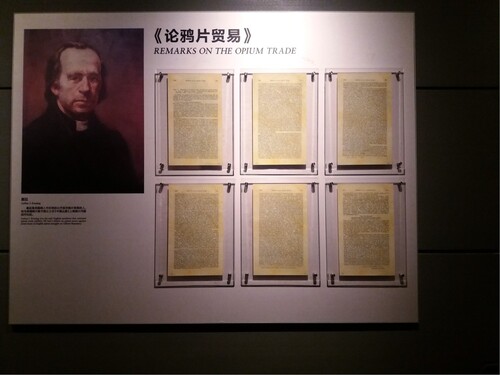

This semiotic reading of translation with its emphasis on materiality can be illustrated by an example of a wall panel in the data collected from the Opium War Museum ().

This panel will be discussed in more detail later, but for the moment it will suffice to describe the components of the panel as follows: a name, a portrait of a Western figure, a short description in Chinese and in English about this person, the title of the document in Chinese and in English, and six pages of a yellowed document in English only. Based on a conventional reading of the spatial arrangement of verbal and visual information, the name can be presumed to refer to the person in the painting; the title provided in English, Remarks on the Opium Trade, likely refers to the document; and the person in the portrait is inferred to be the author of the document. This wall panel does not include a written Chinese translation of the document. Chinese visitors’ access to this essay in English is mediated by their reading of the conventional arrangement of this wall panel. From a linguistic perspective, this English essay is not translated into Chinese. However, based on Kaindl’s (Citation2020) definition, this wall panel represents a translation event as a conventionalized cultural interaction (museum exhibitions on foreign subjects), where the mediator (curator) transfers a source text (the English essay Remarks on the Opium Trade) to a new target audience (Chinese-speaking visitors to this museum) via a combination of the verbal mode (the written interpretation in the text panel) and the visual mode (the image of the author), while the digital reproduction of the six pages of essay can be considered visual and verbal at the same time. It is not possible to judge how “equivalent” the ST is to the TT, but from a semiotic perspective, Kress (Citation2020, 24) argues that in some senses we can see the translation as conveying the same meaning, albeit “expressed—made materially evident—in another of that society’s modes and its affordances”. This process of realizing the same meaning in different material realizations has been discussed more specifically under the term resemiotization (Iedema Citation2003; O’Halloran Citation2011), as mentioned above, which “takes place within the unfolding multimodal discourse itself (as the discourse shifts between different resources) and across different contexts as social practices unfold” (O’Halloran Citation2011, 126). This process usually involves using different semiotic resources in a new context. O’Halloran argues that resemiotization usually results in “metaphorical expressions of meaning” (Citation2011, 126) in unfolding discourses. For example, information about participants, processes, and circumstances in the original linguistic configuration may be resemiotized as visual entities. As can be observed in , the participant (assumed author) is configured by means of images, and the circumstances (historicity) are configured through the materiality of the yellowed paper and old type fonts.

In the present data set, most of the translation is realized in wall panels (as in ), where a combination of semiotic resources is arranged side by side. These wall panels represent the conventional type of verbal-visual interaction observed by Bateman (Citation2014, 18), where “the texts and the images [are both] visually instantiated and intentionally co-present within a joint composition which is two-dimensional and static”. However, other instances of three-dimensional semiotic resources will also feature in the discussions below.

The second research question focuses on the selection of material resources and the design of exhibition spaces. Kaindl’s definition of semiotics highlights the conventionality expected by a community of users. Museums, as a specific type of professional and social community, tend to be highly conventionalized spaces in which the representation and display of artifacts serve a purpose. While museums used to be regarded as warehouses of collection, exhibitions in modern museums now usually construct their narrative through a rigorous process of de/recontextualization (Ferguson Citation1996), whereby material objects leave their original context (are decontextualized) and enter the space of the museums (are recontextualized). Interestingly, in museum studies, some scholars refer to this movement as a process of translation (e.g. Bal Citation2006). Based on a perhaps now outdated metaphor in translation studies, Bal compares the process of selecting exhibition objects to going through a conduit; to travelling through a channel of time, space, language, image, form, and meaning, etc., and entering “the other side of a division or difference” (Citation2006, 536). Also based on a perhaps narrow view of translation activity, Bal argues that while objects are translated into the exhibition space, parts of their meanings may be lost or left behind, just as translations are always impoverished compared to the original. The motivations and decision-making behind this process of translation – that decides which exhibits to enter and which to leave out – have drawn much attention from museum scholars. Ferguson (Citation1996, 178) contends that museum exhibitions are a highly “strategic system of representations”, with the goal of best utilizing all resources, including architecture, wall colours, written labels, and restricted admissions. To answer how and why certain semiotic resources are used in the process of resemiotization, Ferguson (Citation1996) offers two possible approaches. The first is to look at retrieving other possible utterances from multiple voices, i.e. to explore other possible ways of presenting or interpreting the exhibition objects. The second approach is to relate an exhibition “to a larger history – to its contemporary place within the actions of groups and individuals and their changing situations within an already established context” (Ferguson Citation1996, 184). In other words, we need to understand the social and historical context in which the museum organizes the exhibitions, as well as the views held at local, national, or international levels. These two approaches will be addressed in the analysis later. The next section, on the introduction of the Opium War Museum, will also offer some insight into the historical context and the contemporary ideology of the exhibitions.

The Opium War Museum

The Opium War Museum was established in 1957. It memorializes Lin Zexu (1785-1850), a patriotic government official of the Qing dynasty of China, whose opposition to the opium trade eventually led to the First Opium War, also known as the First Anglo-Chinese War. In 1839, Lin confiscated and dumped about one million kilogrammes of opium on the beach at Humen, where the museum is now located. This incident triggered the First Opium War, which marked the beginning of the period known as the “Century of Humiliation” in Chinese history – a period considered as ending with the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

Museum scholars have stated that the main functions of memorial museums are to deal with issues surrounding culpability, the punishment of perpetrators, and truth and reconciliation (Williams Citation2007, 20–21). However, as the Opium War Museum was established in 1957, shortly after the end of the “Century of Humiliation”, its significance has been narrated and re-narrated to serve different political purposes. The aims of these successive re-narrations are reflected in changes to the museum’s name: it started as the “Lin Zexu Memorial Museum”, then changed to the “Humen People’s Anti-British Memorial Museum” in 1972, before reverting to the “Humen Lin Zexu Memorial Museum” in 1985. For administrative purposes, also in 1985, the Humen Lin Zexu Memorial Museum was merged with Weiyuan Fort and the site where Lin Zexu destroyed the dumped opium under the name of the Opium War Museum.

The exhibitions in this museum today serve several purposes. The most obvious is related to the use of the museum as a site for patriotic education – it is listed as one of the “One Hundred National Patriotism Education Base Models” in China. In the “Museum Introduction” on the museum’s English-language website (Opium War Museum Citation2022), it states that “For years, with the correct leadership and continuous support of superior director department, Opium War Museum insists on […] working hard for cultural relic protection and making the best use of historical material to hold patriotism education activities” [sic]. The museum has transformed the two Opium Wars into an occasion for the general celebration of Chinese nationalism, rather than focusing specifically on the historic war against the British. In addition to its patriotic discourse, the museum also serves as a “National Anti-drug Educational Base”, with exhibitions on the adverse effects of opium use. This museum is a clear example of how memorial museums are often narrated and re-narrated to serve different political discourses because they are “especially politically useful in the way they concretize and distill an event” (Williams Citation2007, 128).

The data for this study were collected from the three-storey Lin Zexu Memorial Hall. The first floor begins by presenting medical and pharmacological knowledge about the ingredients of opium and its impact on human beings, before moving to the historical background of the British Empire (mainly the East Indian Company) and the threat to the Qing dynasty in the nineteenth century from the imperialist Western powers. The second floor focuses on the conflict between Britain and China around the use and trade of opium and on Lin Zexu’s anti-opium campaign. The third floor concludes with the aftermath of the failure of Lin’s campaign, including his exile to Northwest China, the legalization of the opium trade, and, ultimately, the British government’s agreement in 1907 to sign a treaty to eliminate opium exports to China.

The primary language in the museum is Mandarin Chinese. In the bilingual panels of this exhibition, the Chinese texts are placed above their English translations. A pilot study was conducted with thirty randomly selected Chinese and English text panels and object labels in the exhibition, with the hypothesis that perhaps a pattern of ideological shifts could be observed moving from Chinese to English; for example, perhaps some anti-British or anti-Western comments featured in the Chinese texts in this “base of patriotism” would have been moderated for international tourists. However, despite the conflict being discussed, a comparison between the Chinese ST and the English TT suggests no obvious patterns of translation shifts on ideological positions. Instead, the TT sticks closely to the ST, without significant deviations, except perhaps that the quality of English may vary. This initial finding seems to suggest that the conflicting Chinese and British historical points of view may not have had much impact on the process of translation.

However, a closer look at the exhibition reveals another layer of translation activity: many of the Chinese wall panels and labels incorporate content from historical texts originally written in other languages, mainly in English. In some cases, the ST, that is, the original historical document, is also on display (as shown in ), and if not, other relevant information is often indicated to museum visitors, such as the ST author, a photo of the ST book cover, or some illustrations from the ST. This translation practice in the museum’s exhibition exemplifies how translation can function on the level of semiotic mode and across different material affordances, and in doing so, demonstrates the process of resemiotization, as discussed above. It is against this background that this article examines how the ST material in English has been resemiotized into different modes in the Opium War Museum.

Resemiotization

This section addresses the first research question: How have semiotics been translated from one mode to another in the museum space? As indicated above, it was observed in the pilot study that the ST material, i.e. printed texts, were translated into the exhibition using a combination of different semiotic resources, such as the physical presence of the English ST, images of ST writers and of original book covers and illustrations. The presence of English words, the pictures, and the wax figures of Western people are all visual semiotics that remind visitors that these texts were originally produced in a different language. Below are three examples of translation using a combination of different semiotic resources.

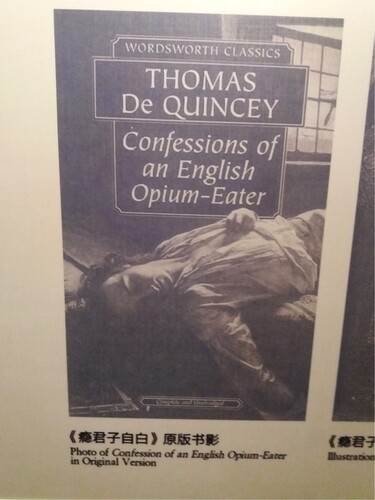

is a digital image reproduction of the book cover of Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821), which is an autobiography by the English author Thomas De Quincey about his addiction to opium. The caption of the image states that this is a photo of the original version of the book.

Figure 2. Book Cover of Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (photo taken by the author; cover reproduced with the kind permission of Wordsworth Editions).

This digital reproduction is part of a panel presented in the “Anti-Opium Campaign” exhibition area, on the second floor of the museum. Similar to discussed earlier, this image is presented along with other visual and verbal semiotics in the conventional presentational style of a wall panel, including a reproduced portrait of the author, a written introduction to the author and the book, and two other digital reproductions of illustrations from the book. To the visitors who engage with the panel, it is clear that the book referred to in the text was originally written in a language other than Chinese as a result of the visual presentation of the ST author, the reproduction of the book’s cover and images, and a brief written introduction to the ST author, as well as the information that this essay was originally published in London Magazine in 1821.

The materialities of digital reproductions as “intangible, reproducible and transmissible” (Kenderdine and Yip Citation2009, 274) and the connection between the replicas and the originals have been much debated in museum and heritage studies (Benjamin Citation1936/Citation1968; Witcomb Citation2010). However, with the advancement of technology and for practical reasons (e.g. loss of the original), digital replicas have become common in museum exhibitions and they function to establish a link with the original. Kenderdine and Yip (Citation2009, 276) argue that in the absence of the original, the authority of the original can be established with “the availability and accessibility of its high-fidelity copies.” O’Callaghan (Citation2020, 75) also argues that replicas can form a part of the complex networks in in which authenticity is generated – authenticity can be understood as “an object’s quality of being real, truthful and genuine” (72). Therefore, considering the conventional approach of using digital reproductions in museums, this reproduced digital image in , presented alongside written texts and other visual objects, functions not only to inform the visitors what this book looks like, but it also serves as evidence to support the existence of the original semiotic resource in the ST context; that is, an essay against the Opium Trade produced in nineteenth-century Britain.

, as presented earlier, demonstrates a different way of signalling to visitors the evidential status of the source material. This wall panel displays a six-page English essay under the title of “Remarks on the Opium Trade”, with the visual presence of and a caption relating to Arthur S. Keating on the left side of the panel. The caption states: “Arthur S. Keating was the only English merchant that criticized opium trade publicly. He had a debate on opium issues against James Innes, an English Opium smuggler in Chinese Repository”.

In terms of the material resources used in this wall panel, the papers that seem to have yellowed with age and are printed with an old-style typeface to encourage visitors imagine them as historical objects. In this wall panel, only a text written in English is exhibited; there is no written translation in Chinese. It may be argued that, for the majority of visitors who are Chinese and do not speak English, these six pages of English text simply perform an exhibitive function, and not any linguistic function – that is, they are to be seen and to be felt, but not to be read. As discussed earlier, this example illustrates how the linguistic resources in the ST are resemiotized into various aspects of the ST, including the participants (the visual image), the circumstances (a sense of history as realized through the affordances of paper material and type fonts), and the written texts in English, which can be regarded as visual symbols to prompt the Chinese readers to feel that they are reading or viewing materials that were originally produced for and in a different language context.

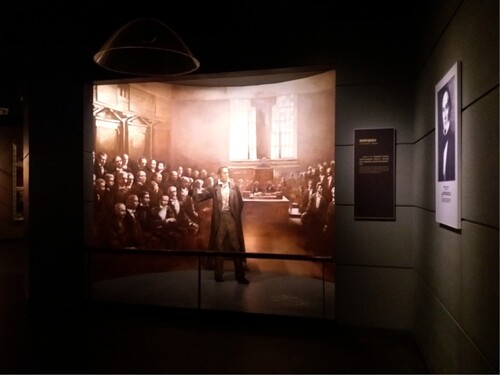

Three-dimensional semiotic resources are also used in the process of resemiotization. One device that gives voice to the ST author can be seen in . This three-dimensional wax figure standing in front of a picture of a British parliamentary debate is introduced in an adjacent written wall panel as William Ewart Gladstone. The following biographical information is also present: “An English Liberal statesman. Before the opium war, as the Tory party member, he fought against the foreign policy of the British government, and condemned the opium trade”. When visitors move closer to the figure, a sensor is triggered and Gladstone starts to “speak” in Chinese via a recorded speech. This foreign scene – the British parliament and a Victorian politician – visually conveys to visitors that the speech was originally given in a different language for a different audience, and visitors are invited to observe this communication between the ST speaker and the audience.

The examples discussed in this section illustrate different ways of resemiotizing the source material: by physically showing the ST as a material object, or by presenting the ST author in visual images or as a wax figure. These semiotic resources, although in different modes and media, all seem to perform the persuasive function of communicating (digitally, at least) how authentic the ST materials are. The institutional and historical context influencing the choice of ST materials will be explored in the next section, but here it can be argued that the choices around which semiotic resources to use in the process of translation are not random, and that most of these semiotic resources have conventionally been used in museum exhibitions to support the (digitally generated) authenticity of the exhibition materials.

De/recontextualization

Although authenticity is highlighted in this museum by combining different semiotic resources, observant visitors may well notice that most of the English source material that was chosen for presentation in this museum condemns opium, criticizes the war as immoral and unjustified, and highly praises Lin Zexu’s political achievements. It seems that translations from foreign language sources play a more important role than Chinese sources in criticizing the British in this museum. In the first exhibition area on the second floor, “Anti-Opium Campaigns”, there are five quotations from British writers, three from American writers, but none from a Chinese source. There, the presence of a “foreign voice” is also highlighted in the translated English content of a thematic panel that notes: “In face of flood of opium, some righteous foreigners launch campaign against opium trade. In the Qing Dynasty, a national wide debate on opium problems was ongoing. Opium ban became a mainstream viewpoint gradually” [sic]. In this text panel, the campaign launched by the “righteous foreigners” is mentioned before the nationwide campaign in China. This section features anti-opium opinions proposed by Westerners, including those on the text panels illustrated in , , and . In contrast, Chinese voices are only presented when visitors enter the next exhibition area, “Measures of banning opium-trade in the Qing Dynasty”; but instead of incorporating any subjective individual voices, this area features more factual descriptions of what measures were taken by the Qing government to ban the opium trade and opium smoking.

As discussed above, in museums, all exhibition materials are selected and staged following a rigorous process of de/recontextualization. In this case study, although different semiotic modes have been used to encourage the visitors to believe in the authenticity of the ST material, it can be observed that several layers of selection were involved. First, it seems that foreigners’ voices supporting Chinese stances were chosen over those that expressed opposition. Second, if we explore other possible utterances from the multiple voices that can be discerned in the displayed artifacts, it can be found that the museum has a clear ideological position in guiding the visitors to perceive the exhibition in a preferred way.

shows how that ideological position plays out in the presentation of the book Confessions of an English Opium-Eater by De Quincey which has been decontextualized from its original context as a published book for English readers in the nineteenth century, and recontextualized in a Chinese museum exhibition to serve the purpose of showing that opium damaged human beings and was resisted not only in China but also in Britain. The dark tones of the digitally reproduced book cover and the frightening scenes from the book reinforce the expression of those ideas. However, despite being used as evidence here to support anti-opium discourse, the book’s author perhaps adopted a more nuanced approach to opium use: “de Quincey disavowed regret almost entirely, arguing that “infirmity and misery do not of necessity, imply guilt”” (Washington Monthly, March 12, 2014), while Ford (Citation2007, 229) also notes that “De Quincey liked his opium”. On the one hand, the resemiotization of the ST sends a strong message to museum visitors by foregrounding the reliability and authenticity of the source material and by emphasizing the theme of anti-opium in this exhibition. On the other, the interpretation of the ST material is only one possible voice from “the labyrinth of possible utterances from multiple voices and complex cultures” (Ferguson Citation1996, 184) associated with this ST material.

A similar process of de/recontextualization can also be found in . This panel, with six pages of essay on remarks on the opium trade with an accompanying name and image of a Western man, is presented as a digital reproduction of an authentic object in support of the idea that some foreigners supported the Chinese government. Since the ST material is not translated into written texts in Chinese, museum visitors can only access the ST through a combination of images and the Chinese caption about the person in the image, which states that Arthur S. Keating was the only English merchant to criticize the opium trade publicly. As argued in the previous section, the image of the author and the presence of the pages function as evidence to support the existence of this multimodal event in the ST context: a righteous British merchant who criticizes his own people and government. However, while the museum presents Keating as an opponent of Opium Trade, multiple representations of Keating also exist. French (Citation2009, 18), for example, describes Keating as “the Register’s hot-blooded Irish-born editor who was a staunch and rather zealous supporter of the opium trade”. From amongst various evaluations of Keating, this museum chose to present him as the righteous friend of the Chinese who spoke out against the opium trade, in keeping with the theme of the exhibition and to the exclusion of other potential representations.

In fact, one intriguing thing about the wall panels based on English source material is that the English texts presented below the Chinese texts are all back translations from the Chinese texts, rather than direct quotations from the original English document. , as discussed above, shows a speech being delivered by a wax figure of the British politician Gladstone in a dramatic setting. The three-dimensional semiotic resource helps to make the exhibition content seem authoritative and convincing. The speech is delivered in spoken Chinese, but an oral English version is also available on the English audio guide. A comparison of the English audio guide in the museum and the original speech delivered by Gladstone suggests that the former, even though seemingly recorded by a native speaker of English, is a back translation from the Chinese text. Below are two short passages that show the difference between them:

They gave you notice to abandon your contraband trade. When they found you would not do so, they had the right to drive you from their coasts on account of your obstinacy in persisting with this infamous and atrocious traffic … justice, in my opinion, is with them. (Pease Citation1880)

The Qing government have warned you to stop the opium trade, but you won’t, thus they have the right to expel you from their coastline, since you stubbornly persist in this immoral and brutal opium trade. In my point view, Chinese has justice on their side. (Audio guide)

Overall, the four examples presented above suggest that, underneath the metaphorical function of reliability and authenticity, the ST material has been de/recontextualized in order to be integrated into the institutional discourse of this museum. This article argues that there seems to be an interesting parallel between the observed exhibition strategy and a shift in Chinese diplomatic strategy away from an unwelcoming and strictly controlling approach to foreigners and towards an emphasis on friendship (youhou guanxi) and foreign friends (waiguo pengyou) (Brady Citation2000, 943). Brady further nuances what has changed under the Deng Xiaoping era:

In the early years of the Mao era, the domestic economy required the workforce to unite behind the CCP government; so anti-foreign feeling was manipulated to bring disparate forces together. In the China of Deng Xiaoping and after, the domestic economy requires a docile, moderately-educated population capable of working for low wages for foreign investors, yet still mindful of the difference between “insiders” and “outsiders”; hence the government promotes positive propaganda about the role of foreigners in China’s economic transformation at the same time as incessant, pernicious propaganda on the past and present wrongs done against China by foreign countries. (Citation2000, 962)

Conclusion

This article begins by recognizing that translations perform exhibitive functions in museums, that is, they are to be viewed rather than simply be read. The data collected from the museum exhibition also exemplify instances of translations that do not fit the linguistic-oriented definition of translation, and therefore semiotics has been brought into the discussion. By viewing translation through the lens of semiotics – or more precisely, through the concept of resemiotization – this article has examined translation practices in a selected museum exhibition as realizations of a carefully chosen combination of semiotic resources. This study recognizes that museums are often highly conventionalized and visual spaces in which emphasis is placed on meanings realized through material properties and, therefore, argues that the materiality of translations should be discussed in the same way that other material objects are discussed in museums. The examples analysed in this article illustrate how the STs, originally printed texts or live speeches, have been resemiotized and exhibited in museums through selected semiotic resources, such as the visual presentation of the ST authors (in digital image reproductions; as wax figures) and the reproduced book covers. Components of the ST can also be emphasized or de-emphasized through conventional generic arrangements (e.g. wall panels and verbal-image juxtaposition). This semiotic lens allows us to explore more deeply how translations feature in our daily activity and play a role in intercultural encounters such as in museums. Museums may be specialized visual spaces, but in other less purposefully built spaces, such as multilingual urban spaces (streets, shops, etc.), translations also often feature as visual representations of intercultural encounters. This article thus paves the way for further exploration of how translations are exhibited and viewed in other multilingual and multimodal spaces.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Min-Hsiu Liao

Min-Hsiu Liao is Assistant Professor at Centre for Translation & Interpreting Studies in Scotland (CTISS), Heriot-Watt University, where she teaches English-Chinese translation and interpreting. Her main research interests focus on multimodal translation in museums and heritage sites, and interaction between text producer and receiver. She is a member of the IATIS training committee.

References

- Bal, Mieke. 2006. “Exposing the Public.” In A Companion to Museum Studies, edited by Sharon Macdonald, 525–542. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Bateman, John. 2014. Text and Image: A Critical Introduction to to the Visual/Verbal Divide. London: Routledge.

- Benjamin, Walter. 1936. /1968. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” In Illuminations, Edited by Hannah Arendt, Translated by Harry Zohn, 217–252. New York: Schocken Books.

- Bezemer, Jeff, and Gunther Kress. 2008. “Writing in Multimodal Texts.” Written Communication 25 (2): 166–195.

- Blunden, Jennifer. 2016. “The Language with Displayed Art(Efacts): Linguistic and Sociological Perspectives on Meaning, Accessibility and Knowledge-Building in Museum Exhibitions.” (Unpublished PhD Thesis). University of Technology Sydney.

- Brady, Anne-Marie. 2000. “‘Treat Insiders and Outsiders Differently’: The Use and Control of Foreigners in the PRC.” The China Quarterly 164: 943–964.

- Ferguson, Bruce W. 1996. “Exhibition Rhetorics: Material Speech and Utter Sense.” In Thinking About Exhibitions, edited by Bruce W. Ferguson, Reesa Greenberg, and Sandy Nairne, 175–190. London: Routledge.

- Ford, Natalie. 2007. “Beyond Opium: De Quincey’s Range of Reveries.” The Cambridge Quarterly 36 (3): 229–249.

- French, Paul. 2009. Through the Looking Glass: China’s Foreign Journalists from Opium Wars to Mao. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Jewitt, Carey, and Berit Henriksen. 2016. “Social Semiotic Multimodality.” In Handbuch Sprache im Multimodalen Kontext, edited by Nina-Maria Klug, and Hartmut Stöckl, 145–164. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Iedema, Rick. 2003. “Multimodality, Resemiotization: Extending the Analysis of Discourse as Multi-Semiotic Practice.” Visual Communication 2 (1): 29–57.

- Kaindl, Klaus. 2020. “A Theoretical Framework for a Multimodal Conception of Translation.” In Translation and Multimodality: Beyond Words, edited by Monica Boria, Ángeles Carreres, María Noriega-Sánchez, and Marcus Tomalin, 49–70. London: Routledge.

- Kenderdine, Sarah, and Andrew Yip. 2009. “The Proliferation of Aura: Facsimiles, Authenticity and Digital Objects.” In The Routledge Handbook of Museums, Media and Communication, edited by Kirsten Drotner, Vince Dziekan, Ross Parry, and Kim Christian Schrøder, 274–289. London: Routledge.

- Kress, Gunther. 2020. “Transposing Meaning: Translation in a Multimodal Semiotic Landscape.” In Translation and Multimodality: Beyond Words, edited by Monica Boria, Ángeles Carreres, María Noriega-Sánchez, and Marcus Tomalin, 24–48. London: Routledge.

- Kress, Gunther, and Theo van Leeuwen. 2001. Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication. London: Hodder Arnold.

- Liao, Min-Hsiu. 2018a. “Translating Multimodal Texts in Space: A Case Study of St Mungo Museum of Religious Life and Art.” Linguistica Antverpiensia 17: 84–98.

- Liao, Min-Hsiu. 2018b. “Museums and Creative Industries: The Contribution of Translation Studies.” Journal of Specialised Translation 29: 45–62.

- Littau, Karin. 2016. “Translation and the Materialities of Communication.” Translation Studies 9 (1): 82–96.

- Liu, Cun-kuan. 1985. “Bao Ling Lun Lin Zexu [John Bowring’s Comments on Lin Zexu].” Jin Dai Shi Yan Jiu [Study of Modern History 6: 241–242.

- Liu, Cun-kuan. 2001. “Qian Tan Wai Guo Ren Dui Lin Zexu de Ren Shi [A Study on Lin Zexu in the Hearts of Foreign People].” Journal of Beijing University of Technology 1 (1): 71–73.

- Neather, Robert. 2008. “ Translating Tea: On the Semiotics of Interlingual Practice in the Hong Kong Museum of Tea Ware” Meta 53 (1): 218–240.

- Neather, Robert. 2012. “Intertextuality, Translation, and the Semiotics of Museum Presentation: The Case of Bilingual Texts in Chinese Museums.” Semiotica 192: 197–218.

- O’Callaghan, Daniel. 2020. “Is That Authentic? Towards an Understanding of the Authenticity of Digital Replicas.” St Anne’s Academic Review 10: 70–80.

- O’Halloran, K. L. 2011. “Multimodal Discourse Analysis.” In Bloomsbury Companion to Discourse Analysis, edited by Ken Hyland, and Brian Paltridge, 120–137. London: Bloomsbury.

- Opium War Museum. 2022. Museum Introduction. The Opium War Museum. Accessed 14 June, 2022. http://www.ypzz.cn/en/f/view2-bwg-profile?p = 99a722660d2c4cbe9fffc9279a845227-99a722660d2c4cbe9fffc9279a845227.

- Pease, Joseph. 1880. The Opium Traffic between India and China. The Debate in the House of Commons on Mr. J. W. Peases’s motion, Friday, June 4, 1880. [Hansard]. (Vol 252). https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1880-06-04/debates/b53a59e8-4235-47f9-beec-31da92fdfbf4/TheOpiumTrade—Observations.

- Williams, Paul. 2007. Memorial Museums: The Global Rush to Commemorate Atrocities. Oxford: Berg.

- Witcomb, Andrea. 2010. “The Materiality of Virtual Technologies: A New Approach to Thinking About the Impact of Multimedia in Museums.” In Theorizing Digital Cultural Heritage: A Critical Discourse, edited by Fiona Cameron, and Sarah Kenderdine, 35–48. Cambridge: MIT Press.