ABSTRACT

Personality traits have an impact on citizens’ political participation especially in relation to voting. However, we know little about how personality traits can influence people’s attitudes towards electoral clientelism. The latter is associated with voting in many societies and has been explained so far mainly through political, social and economic determinants. This article focuses on the psychological dimension and seeks to analyze how personality traits have an effect on citizens’acceptance of electoral clientelism. It distinguishes between three forms of clientelism: vote-buying, product provision and job promises. The statistical analysis uses the Big Five framework and individual-level data from an original survey conducted in Romania after the September 2020 local elections. The results show that only a small share of voters accept electoral clientelism.Conscientiousness, Extraversion and Agreeableness drive the acceptance of different forms of clientelism under specific circumstances.

Introduction

Personality traits often influence citizens’ political attitudes. The traits are relatively stable over time, shape attitudes and determine action in political participation, ideological positioning or political discussions (Mondak et al. Citation2010; Gerber et al. Citation2011; Ha and Lau Citation2015; Weinschenk and Dawes Citation2018). One of the most common ways to analyze personality traits is the Big Five framework, which gauges the essence of personality into five core traits developed throughout life. This framework provides a hierarchical model at the broadest level of abstraction (Bøggild et al. Citation2021) that is consistent across societies (Ha and Lau Citation2015). Much research covers the study of personality features that direct the individual’s dispositions and actions towards external stimuli. For example, in relation to politics, there is extensive literature discussing the effect of the Big Five on political participation or abiding the law (see the theory section), but we know very little about how personality traits could influence attitudes towards specific practices that include participation and law-abiding attitudes. Electoral clientelism is such a practice because it is an avenue of electoral mobilization through which political actors provide goods or preferential access to public services in return for electoral support (Stokes Citation2009); such a provision is usually condemned by law in democratic countries.

This article addresses this gap in the literature and analyzes the extent to which the Big Five personality traits can determine attitudes towards electoral clientelism. More precisely, it analyzes the effects of five personality traits (Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, and Openness to Experience) on the acceptance of electoral clientelism as a practice in the political system. Earlier research identifies several functions of electoral clientelism: a form of social exchange, a mobilizing instrument for political support, a way of keeping power, or a linkage mechanism for democratic accountability (Piattoni Citation2001; Wilkinson Citation2006; Cox et al. Citation2009). There is consensus in the literature about the existence of two major types of clientelism: positive and negative (Mares and Young Citation2019). Positive clientelism includes a wide range of actions from goods and money to preferential access to social benefits and jobs. Negative clientelism includes coercion and threat of punishment. This article focuses exclusively on positive clientelism because it is much more common in elections and people are usually exposed to its forms more than with negative clientelism. The article compares people’s attitudes towards three forms of positive clientelism: vote buying (money), food provision, and job promise.

The central argument of this paper is that those with extreme values for each of the five traits are more likely to accept all three forms of positive clientelism as practices in the political system of their country. Our theoretical framework suggests that this acceptance can be rooted in individual predispositions and personality traits. The analysis uses OLS regression and draws on individual-level data from an original nationwide survey conducted in Romania in the aftermath of the most recent local elections (September 2020). Romania is an appropriate case for analysis due to the documented use of electoral clientelism in its elections over time. Citizens are familiar with this practice and could form attitudes about it over a long period of time (see the section on research design).

The second section of the article reviews the literature, builds arguments that can connect personality traits and the acceptance of electoral clientelism, and formulates five testable hypotheses. The third section presents the research design with emphasis on the case selection, data source and variable measurement. Next, we provide background information about the selected case, clientelism and local elections. The fifth section presents the results of the statistical analysis and interpret them relative to the existing research and daily politics in the country. The conclusions summarize the key findings and discuss their implications for the broader field of study.

The big five and electoral clientelism

The Big Five framework brings together the following personality traits: Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, and Openness to Experience. This section formulates several arguments that link each of these to the acceptance of clientelism as a general practice in the domestic political system. In the absence of earlier studies about this topic, most of the theoretical underpinnings are inspired by the literature on personality traits and political participation – since clientelism is linked to voting – and by the literature covering attitudes towards rule-abiding, crime, equality, or justice. We have no theoretical reasons to expect that personality traits will favor the acceptance of a specific form of clientelism (vote buying, food provision or job promise).

People who score high on extraversion are outgoing, active and prefer to be around people. They have a pronounced engagement with the outside world and are action oriented. They enjoy being with people, participating in social gatherings, are full of energy, and thrive on excitement (McCabe and Fleeson Citation2012; Vaughan-Johnston et al. Citation2021). Extraversion leads people to respond favorably to engaging social and political activities. Extroverts attend campaign events and are assertive so they may enjoy advocating for their preferences in public. They often adhere to norms regarding social aspects of citizenship such as voting or being active in organizations (Dinesen, Nørgaard, and Klemmensen Citation2014). As a result of their active membership of communities or political parties, extroverts are likely to accept certain mobilization strategies. One of these strategies is electoral clientelism and extroverts’ acceptance of such a practice can be driven either by loyalty towards the organization or by their willingness to get gratification from outside.

In contrast, those who are low in extraversion (introverts) are reserved, prefer to be left alone or with few close friends, find it difficult to start a conversation and prefer solitude. These characteristics could make them reject the interactions with political actors, and thus have fewer opportunities of exposure to electoral clientelism. Moreover, the introverts are introspective, thoughtful, and self-reflective (Afshan, Askari, and Manickam Citation2015). They make their own decisions about choices without interference from external factors. Such individuals are characterized by internal locus of control and have high levels of self-confidence, which makes them less prone to commit or accept crimes compared to others (Terpstra, Rozell, and Robinson Citation1993). The introverts are unlikely to accept positive clientelistic exchanges in society also because they seek to remain independent, to have a choice of possibilities and get things their own way (Lasch Citation1991).

Agreeableness is a trait related to cooperation and altruism. People who are highly agreeable are tender-minded, straightforward, empathic, trustful, compliant, more cooperative and show prosocial behaviors (Costa and McCrae Citation1992; Power and Pluess Citation2015). Agreeable people wish to maintain an amicable social relationship and contribute to the community well-being (Gerber et al. Citation2011). Their emphasis on amicable relationships is likely to make these individuals more prone to consider electoral clientelism as an acceptable practice in society. This happens because highly agreeable people may consider the clientelistic exchange as a specific type of social relationship. This happens also because agreeable people are more naïve than the other citizens and may regard electoral clientelism as an appropriate mechanism to help those candidates or political parties offering the gift (Barasch, Levine, and Schweitzer Citation2016). Moreover, highly agreeable individuals tend to stay away from conflict (Weinschenk and Dawes Citation2018). Electoral competition involves a conflict on political issues and some polarization in society. Highly agreeable individuals may see clientelism as an acceptable practice to diminish this competition.

Less agreeable persons tend to be more competitive and conflictual (Stead and Fekken Citation2014), less empathic and more concerned with their own interests. Because they tend to be unmoved by other people`s perceptions and have the freedom to act in accordance with their views, they may be more reluctant to the acceptance of clientelism. Equally important, persons with low agreeableness do not support manipulative acts (like clientelism), preferring honest behaviors (Alalehto Citation2003).

Conscientiousness is characterized by competence, order and planning, dutifulness and deliberation, thoughtfulness, commitment, reliability, good self-control, and rule abiding (Costa and McCrae Citation1992; Power and Pluess Citation2015; Costantini, Saraulli, and Perugini Citation2020). Highly conscientiousness people are unlikely to accept electoral clientelism because they are moral and of good character (Bollich et al. Citation2016), and may see in elections as a way to maintain the accountability of the political system and to represent interests. Clientelism can alter this mechanism: if people vote in line with the gifts and promises they receive rather than according to their preferences and beliefs, then the basic principle of elections is compromised. Highly conscientious people usually follow the rules, norms and traditions (Jackson et al. Citation2010) and thus they condemn unlawful means of gaining votes.

Less conscientious individuals are impulsive, disorganized and have lower competence, which may all be conducive to the acceptance of electoral clientelism as a general practice. Their impulsiveness may push such people to accept many practices in society, including electoral clientelism, without thinking much about the consequences for the political system and society. Those with lower self-control seek immediate and easy gratification (Gottfredson and Hirschi Citation1990)which is often the avenue provided by clientelism in elections. Low self-control may be also associated with clientelism because it requires some degree of cooperation between the voter and the party, similar to what happens in the case of victims and perpetrators in crimes (Holtfreter, Reisig, and Pratt Citation2008). The lack of discipline is associated to economic crimes because the individuals with such a trait reject the norms in a society (Collins and Bagozzi Citation1999). The persons with low conscientiousness are likely to commit a crime because they have limited ability to handle situations in a systematic manner, and they depend on situations (Alalehto Citation2003). In the case of elections, low conscientious individuals may have low competence in assessing the political competition and they accept a clientelist exchange as a practice than can reduce the uncertainty in casting a vote.

Neuroticism is a trait characterized by sadness and the tendency to experience negative emotions. People with high levels of neuroticism are moody, emotional instable and anxious. Earlier studies show that highly neurotic citizens are not politically active and disregard social norms and conventions (Dawkins Citation2017). They may reject clientelism because it is associated to the political game towards which they have little interest or resent it. Highly neurotic individuals may develop negative feelings and emotional reactions when they get involved with the political element and will see others as threats (Dinesen, Nørgaard, and Klemmensen Citation2014). They may find clientelism as threatening – since it requires some interaction with political actors – that could trigger high levels of distress and hostility. Combined with their tendency to interpret ordinary situations as threatening, this feature makes them unlikely to accept electoral clientelism.

In contrast, individuals who score low in neuroticism are less reactive to stress, more emotionally stable and more optimistic (Power and Pluess Citation2015). Because they have a relatively stable mood and are even-tempered, they will not see politicians approaching them as threats and they will know how to deal with them. Emotionally stable individuals will show higher levels of participation in a broad range of political activities (Gerber et al. Citation2011), will vote while calmly consider and weigh any information they receive (Ha and Lau Citation2015). Clientelist exchanges will be accepted by emotionally stable individuals if the exchange works in their interest.

Openness to Experience is the positive valuation and appreciation of new experiences. Those with a high openness have creativity, imagination, high levels of self-efficacy, and broad interests. High openness favors political participation and community engagement (Gerber et al. Citation2011; Ha and Lau Citation2015; Weinschenk and Dawes Citation2018) because people with this trait like to be active, enjoy exchanging ideas, and enjoy new experiences. They take part in the electoral process because it means engaging with a variety of arguments, ideas and information. People who are open to experiences are more likely to accept electoral clientelism as a practice in society because the offer of goods and services during campaign may count as new experiences. Citizens who are open to experiences seek novelty and may be more willing to engage in risky behaviors (Cherry Citation2020; DiLima Citation2020), two features that apply to electoral clientelism. Open individuals may be excited by the idea to try new things and can disregard the implications of their actions (Lauriola and Weller Citation2018).

Those with low levels of openness are practical, traditional often rigid (Costa and McCrae Citation2013). They will find difficult to engage in new situations will pass up the opportunity to try new things. Because they prefer familiar routines and tend to be conventional, we expect that those with low levels of openness to experience will not accept clientelism since this practice is quite risky.

Following all these arguments in the literature, we expect that:

H1:

High Extraversion favors the acceptance of electoral clientelism

H2:

High Agreeableness favors the acceptance of electoral clientelism

H3:

Low Conscientiousness favors the acceptance of electoral clientelism

H4:

Low Neuroticism favors the acceptance of electoral clientelism

H5:

High Openness to Experience favors the acceptance of electoral clientelism

Control variables

In addition to personality traits, we control for five variables that could influence citizens’ acceptance of electoral clientelism: political interest, importance of elections, education, income and rural vs urban areas.Footnote1 First, the people with high interest in politics may be more inclined to perceive clientelism as rigging the electoral game and reject it. To them, clientelism can threaten the idea of political representation (Piattoni Citation2001). People who consider elections important are likely to follow a similar logic. They may see the elections as crucial for democracy, take them seriously and would reject clientelism as practices that interfere with citizens’ preferences (Corstange Citation2018). The highly educated individuals may understand better the negative implications of clientelist practices for society and are likely to reject them. In contrast, those with a low level of education will be tempted to accept clientelism because they do not know much about it, including its illegal character (Mizuno Citation2012).

Due to their limited access to resources, people with low income may be more prone to accept clientelism. To them the elections may represent an opportunity to supplement their income (Nichter Citation2008; Canare, Mendoza, and Lopez Citation2018). The acceptance of clientelism may also differ from rural to urban residents. Those living in rural areas may be more inclined to accept clientelism (Koter Citation2013; Cinar Citation2016). In these areas, compared to towns or cities, the clientelist chain is stronger. Individuals may consider the clientelist relationship as recognizing their personal needs and thus as legitimate.

Research design

To test the effects of personality traits on the acceptance of electoral clientelism, this article uses individual-level data from an original nationwide survey conducted in October 2020 in Romania. The country is an appropriate case for our analysis due to the documented use of electoral clientelism in its local, legislative and presidential elections over time (Gherghina and Volintiru Citation2017; Mares and Young Citation2019). Most parliamentary political parties engage regularly in electoral clientelism across the country, within and outside their electoral strongholds. The voters are exposed to the process either directly as recipients of clientelistic offers or indirectly by knowing someone who received clientelistic offers. The direct exposure to the process is usually documented in the media that report how the exchange takes place in various places (Gherghina Citation2013). The indirect exposure is gauged similarly by media reports but also by surveys. For example, more than 35% of the respondents to our survey answer that someone they know was offered money, food products or a job in exchange of their votes in the September 2020 elections. All these indicate a long-lasting presence of clientelism in the Romanian society, which makes the country suitable to investigate the impact of long-lasting personality traits.

The survey was launched online several days after the local elections and closed three weeks later. The timing of the survey was chosen to minimize respondents’ memory bias. According to the legislation, the campaign starts one month before the election date. All clientelistic exchanges occur during the campaign and a survey conducted immediately after elections can gauge their attitudes towards recent events. The local elections are of particular importance because there are two simultaneous races, played by different rules. On the one hand, voters directly elect the mayor according to a first-past-the-post system. On the other hand, the parties compete for seats in the local council according to a closed-list proportional representation system. These competitions motivate both candidates and parties to engage in clientelistic exchanges for different purposes.

The survey included 1,140 respondents and used a quota sampling method representative for the Romanian population regarding gender, education, medium of residence (rural vs. urban), and income.Footnote2 All the quotas were relative to the last official statistics available for the country – the 2011 census – and reflect key variables for the study of clientelism. Age was the fifth quota included in the initial sampling, but it was dropped due to the difficulty to get older participants; the sample is skewed towards younger age cohorts (e.g. the census population between 25 and 34 years is 14% and in our sample is 19%, the census population between 55 and 64 is 13% and in our sample is 6%). The respondents were not pre-selected. The online survey was distributed through messages on social media, discussion forums, or e-mails sent to associations. In addition, the survey was distributed to respondents that were part of a pool of available individuals, based on their participation to previous surveys conducted by authors’ institutions. The questionnaire was in Romanian and the average duration of completion was eight minutes. The non-probabilistic nature of the sample could generate potential participation bias. Those people interested in politics and actively engaged were more likely to complete the questionnaire (which is also reflected in Appendix 2). Also, the tech-savvy individuals were more likely to answer the survey than others. These variables were secondary to this analysis and when controlling for some of them the main effects still stand.

Measurement and method of analysis

The dependent variable of this study is the acceptance of electoral clientelism (Appendix 1). The latter includes several forms of exchanges that often go hand in hand. However, in this case, we go for three separate dependent variables that distinguish between the form of clientelistic exchanges: vote buying, products offer (food, feast) and job promise after election. The correlation between these three forms is positive, strong and statistically significant at the 0.01 level, but leaves room for meaningful analyses if we treat them separately. The correlation between vote buying and products offer is 0.81, between vote buying and job promise is 0.56, and between products offer and job promise is 0.66.

To assess personality traits, we use the Ten-Item Personality Inventory (Gosling, Rentfrow, and Swann Citation2003), which is a short version of the Big Five Questionnaire. The Inventory consists of ten items distributed along the Big Five personality dimensions: Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism and Openness to Experience. The pair of traits are: 1) Extraverted, enthusiastic; 2) Critical, quarrelsome; 3) Dependable, self-disciplined; 4) Anxious, easily upset; 5) Open to new experiences, complex; 6) Reserved, quiet; 7) Sympathetic, warm; 8) Disorganized, careless; 9) Calm, emotionally stable and 10) Conventional, uncreative. The scale scoring follows the procedures of the Ten-Item Personality Inventory and recodes five reverse scored items. It then groups them as follows (R stands for the reverse-coded items): Extraversion: 1, 6 R; Agreeableness: 2 R, 7; Conscientiousness; 3, 8 R; Neuroticism: 4 R, 9; Openness to Experiences: 5, 10 R. We then sum up the two items (the standard item and the recoded reverse-scored item) that make up each scale; this procedure gives the same results as the average used by Gosling, Rentfrow, and Swann (Citation2003).

The measurement for all the control variables is done according to questions that are common in many international surveys (Appendix 1). All control variables are measured on ordinal scales, which is not ideal for OLS regression especially when there is a low number of categories. Alternatively, we used dummy variables for controls to see if any differences occur in the effects. Since the results are very similar, we use the initial coding.

The descriptive statistics for all variables included in the analysis is presented in detail in Appendix 2. For all the variables, the ‘DK/NA’ answers are treated as missing values and are excluded from the analysis. The distribution of attitudes towards clientelism () is skewed towards the rejection of such a practice, which is in line with the observations in other countries (Gherghina, Saikkonen, and Bankov Citation2022). The analysis uses OLS regression with robust standard errors. Our dependent variable is measured on a Likert scale with 11 values, and we should ideally use ordinal logistic regression. However, the assumption of proportional odds is violated, and we could use only a generalized ordered logistic model. The latter is more difficult to interpret and present, but we used it as a robustness test for the main findings. An alternative could have been a binary logistic regression that distinguishes between complete rejection (value 0) and degrees of acceptance. A third alternative was to run regression for rare events with robust clustered standard errors. We ran all three alternative models, but since the results are similar with the OLS regression, we use this one for reasons related to simplicity. Our approach is in line with that in earlier studies (Gherghina, Saikkonen, and Bankov Citation2022). The test for multi-collinearity shows that the independent variables and controls are not highly correlated: the highest value of the correlation coefficient is 0.43 and the VIF values are lower than 1.29.

Clientelism and local elections in Romania

Romania is divided into 41 counties – of different size in terms of population and territory – plus the capital city Bucharest. Each county includes villages, towns and cities. The local elections are organized every four years for four different positions: two at the level of the locality (the mayor and the local council) and two at the county level (the president of the county council and the county council). The mayor and the president of the county council are elected according to a first-past-the post system, while the two councils – local and county – are elected using a closed-list proportional representation system. The Romanian party system in the last decades features two major and three minor political parties. The major competitors are the Social democratic Party (PSD) that won all but one of the popular votes in post-communist Romania and the National Liberal Party (PNL). The small competitors differ from one electoral cycle to another, the only one with continuous presence is the Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania (UDMR) (Marian Citation2018; Gherghina and Tap Citation2022).

One of the major problems in Romania is corruption. According to Transparency International Index, in 2020, Romania is the 69th least corrupt out of 180 countries. At the European level, Romania is the third most corrupt after Bulgaria and Hungary (Transparency International Citation2021). The corrupt context favors the existence of electoral clientelism (Roper Citation2002; Gherghina and Chiru Citation2012). Electoral clientelism has been often encountered in local elections in the last two decades irrespective of the parties in government. Until 2012, the provision of goods was widespread and not considered clientelism. After that, the government issued an emergency decree that allowed only for specific gifts with a value lower than 10 RON (approx. 2.5€): postcards, DVDs, pens, mugs, T-shirts, caps, capes and jackets with their electoral sign. Both candidate and voters who offer or receive anything apart from these gifts could go to prison for a period between six months and five years (Romanian Government Citation2012).

In 2016, the Campaign Finance Guide elaborated by the electoral authority put an end to any gifts. The document forbids electoral competitors from purchasing, offering, distributing or giving, directly or indirectly, pens, mugs, watches, T-shirts, jackets, raincoats, vests, hats, scarves, sacks, bags, umbrellas, buckets, lighters, matches, foodstuffs, alcoholic beverages, cigarettes and similar products (Permanent Electoral Authority Citation2016). In spite of these legislative provisions and strict limitations, the cases of clientelism continued to emerge in the 2020 local elections. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the election campaign took place in special conditions and the interaction between candidates and voters was limited. The local media reported many incidents of clientelism throughout the entire country. For example, one news report presented photographic evidence illustrating how a voter from a village in a Southern county received money from a car belonging to a local councilor (Mirea Citation2020). Another example was the provision of public feasts with food and alcoholic beverages in a village from a Northern county. Although the regulations during the pandemic did not allow for such events, a local party organization ignored them (Rotaru Citation2020).

Explaining the acceptance of clientelism

This section explains what favors the acceptance of positive clientelism among the Romanian voters. Prior to the analysis we provide a brief overview of electoral clientelism and local elections in Romania with emphasis on its use and legal provisions meant to limit this practice.

Analysis and results

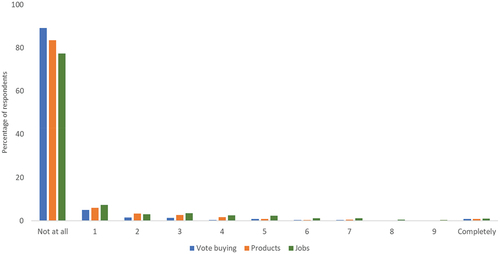

The distribution of respondents according to their acceptance of three forms of electoral clientelism () indicates limited variation. In general, a very large share of the respondents does not consider any of the three forms acceptable under any circumstances. Roughly 89% of the survey respondents do not consider vote buying acceptable at all and approximately 83% have the same attitude towards product offers from political parties and candidates. The percentage is somewhat lower for those who do not find jobs promise acceptable at all, but still over three quarters of the respondents (roughly 77%).

These high percentages have two important empirical and methodological implications. First, they indicate that electoral clientelism, despite its extensive use by political actors in the last two decades, has limited acceptance in society. The correlations between the three forms of electoral clientelism – briefly mentioned in the research design section – mean that those who reject one form will reject the others as well. Nevertheless, there is a difference in the extent to which vote-buying is rejected right away compared to job promises. The latter is the form of electoral clientelism with the highest values among the three forms for almost all values of the scale on which the acceptance is recorded. One possible explanation for which vote buying is not accepted at all by so many Romanians may be related to legal provisions, perceptions and the nature of the promised goods. The engagement in clientelistic exchanges of any sort is punished by law, this includes the citizens who receive them. However, receiving money is more likely to be associated with bribe and illegality when compared to getting food or a job promise. Receiving money is a material and immediate reward, a fact that can be checked. In contrast, at least in the mind of ordinary people, a job promise occurs in the future and it is more difficult to be checked or related to voting behavior.

Second, there is a methodological implication. Since the variation of the dependent variables is so small (especially for vote buying), the explanatory power of the independent and control variables will be limited. The size of effects will be small. This means we will interpret all those effects different from zero that are statistically significant.

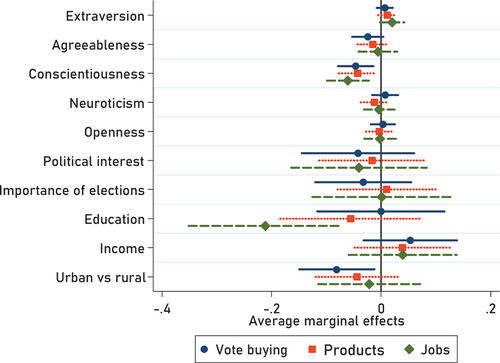

presents the marginal effects of the personality traits and control variables on the acceptance of electoral clientelism. We run three different models, for each mode of clientelism: vote buying, product offers and job promises. The regression coefficients are presented in detail in Appendix 3. We have also run three other models without the controls, but the results are very similar and for parsimony we keep only the complete models (with controls) in the paper. The explained variance of the statistical models is similar, but low mainly due to the limited variation on the dependent variables and high skewness. We tested for other predictor variables apart from personality traits, but the explanatory power continued to be small, which indicates that the structure of the data may be the problem rather than omitted variables bias. In spite of these limitations, the statistical analysis finds empirical support for some of the hypothesized effects, providing a detailed and nuanced picture.

The marginal effects indicate that low conscientiousness (H3) influences the acceptance of all three modes of electoral clientelism, statistically significant at the 0.01 level. This is in line with the arguments from the literature and shows that voters with lower levels of thoughtfulness, limited sense of duty, easy-going or who are less goal-oriented accept electoral clientelism. This effect is the strongest among the personality traits and the only one consistent across all three forms of clientelism. One possible explanation for which the low conscientious Romanian voters find electoral clientelism more acceptable refers to the socialization process. Electoral clientelism has been used extensively for at least two decades and voters may see it as a natural practice of the political game. Being easy-going and with a low sense of duty makes voters more prone to have such an approach.

There is some empirical evidence for the positive effect of Extraversion (H1) on the acceptance of job promises. Although quite small, it is statistically significant and supports the theoretical expectation. It does not appear to have an impact on the acceptance of vote buying. One possible explanation for this finding is that extrovert voters in Romania may find election campaigns appealing and enjoy the campaign activities because they prefer to company of people. In that sense, they understand elections as being important for community and the use of money as financial incentives for a vote may be unacceptable. However, when it comes to job promises, extroverted Romanian voters may consider them as rewards for the efforts and loyalty they displayed during the election campaign (Toma Citation2020).

Contrary to our theoretical expectations, voters with low levels of Agreeableness accept easily vote buying as a common practice in elections. The empirical evidence is not very strong, but it is statistically significant. One possible explanation for this finding is that the less agreeable individuals place their own concerns and issues above those of others. The provision of money for votes is at least partially in line with this approach. Some of these voters find the financial incentive acceptable because it addresses some of their immediate concerns. At the same time, the less agreeable individuals are usually more conflictual and is more difficult to establish long term relationship or a dialogue. This is one possible explanation for which when it comes to job promises, they are hostile and antagonistic. Jobs involve a much closer and longer-lasting relationship with the candidate that is difficult for a person with low levels of agreeableness to maintain (Yıldırım and Kitschelt Citation2020). They will generate conflicts much faster and will not agree to do things that run counter to their ideas and principles. They reject a job promise to a similar extent as the high agreeable individuals.

Neuroticism and Openness to Experience do not have a strong or significant effect on the acceptance of different forms of clientelism. Citizens who are emotionally unstable and moody reject clientelism as much as those citizens with a positive approach towards life. One possible explanation for the absence of an effect in the case of this trait is that clientelism is rarely related directly to emotions. It can trigger them under specific circumstances: for instance, a clientelistic offer from a candidate may drive rage among the supporters of an opponent. In practice, this is something that occurs in Romania quite often. For example, during the 2020 local elections, the local authorities charged 133 criminal acts and 137 contraventions, they wrote 88 fines amounting to over 122,000 RON, and applied 47 written warnings in counties all over Romania for irregularities on voting day (Citation2020). In general, the promise of a job may lead to positive feelings among those voters who learn about this possibility. However, none of these situations is associated with emotional stability and thus the impact of Neuroticism is unlikely to occur.

Among the control variables, education and the medium of residence have statistically significant effects for specific forms of clientelism. People who are poorly educated are likely to find acceptable the job promise by a candidate or political party. This is the strongest effect in the statistical models, but it is not noticeable for vote buying and product offers. This finding points out the vital role that education can play in diminishing the acceptance of electoral clientelism. People living in the rural areas and small urban areas accept vote-buying more than those living in medium or large urban areas. One possible explanation for this attitude is related to the fact that the interactions between candidates and voters are much more intense in rural areas. Voters are more familiar with the candidates and this favors their predisposition to accept gifts in exchange for votes. Moreover, the Romanians from the rural areas can accept clientelism for an economic reason. They usually have lower income than those living in urban areas, which is also confirmed by the correlation coefficient between these two variables in our survey (r = 0.19, statistically significant at the 0.01 level).

Political interest, the importance of elections and income do not influence the attitudes towards any form of positive electoral clientelism. Neither the generally disinterested Romanian citizens nor those who do not consider important the 2020 local elections are more prone to accept clientelism compared to the interested and informed citizens. The latter are relatively different groups of people as indicated by the medium value of the correlation coefficient between them (r = 0.43). As such, the acceptance of clientelism is not related to how much people follow politics and to the importance they associate to it. Income has no statistically significant effect on the acceptance of clientelism. Contrary to theoretical expectations, we find that people with a higher income are slightly more likely to accept any form of clientelism. These results nuance previous findings about how poor people are more susceptible to the use of clientelism (Stokes Citation2009; Nichter Citation2010; Pellicer et al. Citation2021). In terms of attitudes, the income makes no difference: people who are economically vulnerable are not more open to the idea of clientelism.

Conclusions

This article analyzed the extent to which extreme values on each of the Big Five personality traits can favor the acceptance of three forms of electoral clientelism: vote buying, products provision, and job promise. It uses individual-level data from a survey conducted in Romania in the aftermath of the 2020 local elections. The results show that only a small share of Romanians accept any of the three forms of clientelism. This self-reported attitude illustrates that very few citizens consider such a practice as acceptable although it has been used extensively by parties in the last two decades. In some instances, the low levels of Conscientiousness consistently increase the acceptance of all three forms of electoral clientelism. High Extraversion drives sometimes the acceptance of job promises, while in several occasions low Agreeableness favors the acceptance of vote-buying.

These findings have broader implications beyond the case study covered by this paper. On the one hand, this study shows that some personality traits can have an effect on attitudes related to clientelism. Previous research emphasizes how personality traits can influence political behavior (participation) and our results expands the remit of effects to the acceptance of a practice associated with voting. As such, personality matters both for what people do and for how they think about what is done. Future analyses seeking to explain attitudes towards clientelism can account for psychological traits. So far, these were widely neglected. The evidence provided in this article, although somewhat limited, points in the direction of important effects that deserve further exploration. Moreover, we show that people are sophisticated when expressing attitudes about electoral clientelism and differentiate between its forms. Two personality traits have an effect only on a form of clientelism and not on the other two. This may indicate that voters have a nuanced perception about the forms of clientelism and thus their inner triggers vary.

There are some limitations to this study such as the low variation of attitudes towards clientelism, data confined to a single case study, and weak explanatory potential of the statistical models. Further studies can address these limitations and test some of the observations made here. One possible avenue for research is the development of a standard questionnaire to be applied in several countries, including more attitudinal variables that can be tested against personality traits. This will increase the variation of psychological traits and of attitudes towards clientelism. A comparative approach would account for different political cultures and add complexity to the explanations. Another direction for research can investigate if personality traits have an indirect effect on the acceptance of clientelism. The results of our study provide limited support for a direct effect and thus it is worth investigating if the effects of personality are not mediated by other political attitudes such as political efficacy or social and political trust.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Apart from the controls included in the analysis, we had theoretical reasons to test for other variables with potential effect on citizens’ acceptance of clientelism: trust in political institutions, satisfaction with democracy, satisfaction with government performance, gender, area of residence (county), turnout in the 2020 local elections, party they voted for, or media exposure. To avoid overfitting, we excluded them from the analysis especially since they have neither strong nor statistically significant effects. Nevertheless, the online appendix includes the model with some of these supplementary controls (trust and satisfaction) to illustrate that the main effects hold when the model gets more complex.

2. This is the number of complete answers. There were almost 1,400 respondents who started the survey but dropped out at various questions.

References

- Afshan, A., I. Askari, and L. S. S. Manickam. 2015. “Shyness, Self-Construal, Extraversion–Introversion, Neuroticism, and Psychoticism: A Cross-Cultural Comparison Among College Students.” SAGE Open 5 (2): 215824401558755. doi:10.1177/2158244015587559.

- Alalehto, T. 2003. “Economic Crime: Does Personality Matter?” International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 47 (3): 335–355. doi:10.1177/0306624X03047003007.

- Barasch, A., E. E. Levine, and M. E. Schweitzer. 2016. “Bliss is Ignorance: How the Magnitude of Expressed Happiness Influences Perceived naiveté and Interpersonal Exploitation.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 137: 184–206. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2016.05.006.

- Bøggild, T., R. Campbell, N. Mk, P. Hh, and V. H. Ja. 2021. “Which Personality Fits Personalized Representation?” Party Politics 27 (2): 269–281. doi:10.1177/1354068819855703.

- Bollich, K. L., P. L. Hill, P. D. Harms, and J. J. Jackson. 2016. “When Friends’ and Society’s Expectations Collide: A Longitudinal Study of Moral Decision-Making and Personality Across College.” PLoS ONE 11 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0146716.

- Canare, T. A., R. U. Mendoza, and M. A. Lopez. 2018. “An Empirical Analysis of Vote Buying Among the Poor: Evidence from Elections in the Philippines.” South East Asia Research 26 (1): 58–84. doi:10.1177/0967828X17753420.

- Cherry, K. 2020. How Openness Affects Your Behavior, Very well mind.

- Cinar, K. 2016. “A Comparative Analysis of Clientelism in Greece, Spain, and Turkey: The Rural–Urban Divide.” Contemporary Politics 22 (1): 77–94. doi:10.1080/13569775.2015.1112952.

- Collins, J. M., and R. P. Bagozzi. 1999. “Testing the Equivalence of the Socialization Factor Structure for Criminals and Noncriminals.” Journal of Personality Assessment 72 (1): 68–73. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa7201_4.

- Corstange, D. 2018. “Clientelism in Competitive and Uncompetitive Elections.” Comparative political studies 51 (1): 76–104. doi:10.1177/0010414017695332.

- Costa, P. T., and R. R. McCrae. 1992. “Normal Personality Assessment in Clinical Practice: The NEO Personality Inventory.” Psychological Assessment 4 (1): 5–13. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.4.1.5.

- Costa, P. T., and R. R. McCrae. 2013. “The Five-Factor Model of Personality and Its Relevance to Personality Disorders.” The Science of Mental Health: Volume 7: Personality and Personality Disorder 6 (March 1991): 17–33.

- Costantini, G., D. Saraulli, and M. Perugini. 2020. “Uncovering the Motivational Core of Traits: The Case of Conscientiousness.” European Journal of Personality 34 (6): 1073–1094. doi:10.1002/per.2237.

- Cox, G. W. 2009. “Swing Voters, Core Voters, and Distributive Politics.” In Political Representation, edited by I. Shapiro, et al., 342–357. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dawkins, R. 2017. “Political Participation, Personality, and the Conditional Effect of Campaign Mobilization.” Electoral studies 45: 100–109. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2016.11.018.

- Digi 24. 2020. Incidente alegeri locale 2020.

- DiLima, R. K. 2020. Risky Behavior: The Roles of Depression, Openness to Experience, and Coping.

- Dinesen, P. T., A. S. Nørgaard, and R. Klemmensen. 2014. “The Civic Personality: Personality and Democratic Citizenship.” Political studies 62 (S1): 134–152. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.12094.

- Gerber, A. S., G. A. Huber, D. Doherty, C. M. Dowling, C. Raso, and S. E. Ha. 2011. “Personality Traits and Participation in Political Processes.” The Journal of Politics 73 (3): 692–706. doi:10.1017/S0022381611000399.

- Gherghina, S. 2013. “Going for a Safe Vote: Electoral Bribes in Post-Communist Romania.” Debatte: Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe 21 (2–3): 143–164. doi:10.1080/0965156X.2013.836859.

- Gherghina, S., and M. Chiru. 2012. “Taking the Short Route: Political Parties, Funding Regulations, and State Resources in Romania.” East European Politics & Societies 27 (1): 108–128. doi:10.1177/0888325412465003.

- Gherghina, S., I. Saikkonen, and P. Bankov. 2022. “Dissatisfied, Uninformed or Both? Democratic Satisfaction, Political Knowledge and the Acceptance of Clientelism in a New Democracy.” Democratization 29 (2): 211–231. doi:10.1080/13510347.2021.1947250.

- Gherghina, S., and P. Tap. 2022. “Buying Loyalty: Volatile Voters and Electoral Clientelism.” Politics.

- Gherghina, S., and P. Tap. 2022. “Buying Loyalty: Volatile Voters and Electoral ClientelismBuying Loyalty: Volatile Voters and Electoral Clientelism.” Sfera Politicii 26 (3–4): 70–82. Politics, no. online only. Marian, Claudiu

- Gherghina, S., and C. Volintiru. 2017. “A New Model of Clientelism: Political Parties, Public Resources, and Private Contributors.” European Political Science Review 9 (1): 115–137. doi:10.1017/S1755773915000326.

- Gosling, S. D., P. J. Rentfrow, and W. B. J. Swann. 2003. “A Very Brief Measure of the Big-Five Personality Domains.” Journal of Research in Personality 37 (6): 504–528. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1.

- Gottfredson, M. R., and T. Hirschi. 1990. A General Theory of Crime. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Ha, S. E., and R. R. Lau. 2015. “Personality Traits and Correct Voting.” American Politics Research 43 (6): 975–998. doi:10.1177/1532673X14568551.

- Holtfreter, K., M. D. Reisig, and T. C. Pratt. 2008. “Low self‐control, Routine Activities, and Fraud Victimization.” Criminology 46 (1): 189–220. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2008.00101.x.

- Jackson, J. J., D. Wood, T. Bogg, W. Ke, H. Pd, and R. Bw. 2010. “What Do Conscientious People Do? Development and Validation of the Behavioral Indicators of Conscientiousness (BIC).” Journal of Research in Personality 44 (4): 501–511. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2010.06.005.

- Koter, D. 2013. “Urban and Rural Voting Patterns in Senegal: The Spatial Aspects of Incumbency, C. 1978-2012.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 51 (4): 653–679. doi:10.1017/S0022278X13000621.

- Lasch, C. 1991. The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations. revis ed. London: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Lauriola, M., and J. Weller. 2018. “Personality and Risk: Beyond Daredevils-Risk Taking from a Temperament Perspective.” Psychological Perspectives on Risk and Risk Analysis: Theory, Models, and Applications. 3–36. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-92478-6_1#citeas

- Mares, I., and L. E. Young. 2019. Conditionality and Coercion: Electoral Clientelism in Eastern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Marian, C. 2018. “The Social Democrat Party and the Use of Political Marketing in the 2016 Elections in Romania.” Sfera Politicii 26 (3–4): 70–82.

- McCabe, K. O., and W. Fleeson. 2012. “What is Extraversion For? Integrating Trait and Motivational Perspectives and Identifying the Purpose of Extraversion.” Psychological Science 23 (12): 1498–1505. doi:10.1177/0956797612444904.

- Mirea, C. 2020. “Posibil caz de mita electorala la Sornicesti.” Olt-Alert. https://olt-alert.ro/2020/09/23/posibil-caz-de-mita-electorala-la-scornicesti-o-femeie-primeste-bani-de-la-liberali-fotovideo/

- Mizuno, B., and E. Lorena. 2012. “Does Everyone Have a Price? The Demand Side of Clientelism and Vote-Buying in an Emerging Democracy.” PhD Dissertation, Duke University.

- Mondak, J. J., H. Mv, D. Canache, S. Ma, and A. Mr. 2010. “Personality and Civic Engagement: An Integrative Framework for the Study of Trait Effects on Political Behavior.” The American Political Science Review 104 (1): 85–110. doi:10.1017/S0003055409990359.

- Nichter, S. 2008. “Vote Buying or Turnout Buying? Machine Politics and the Secret Ballot.” The American Political Science Review 102 (1): 19–31. doi:10.1017/S0003055408080106.

- Nichter, S. 2010. Politics and Poverty: Electoral Clientelism in Latin America. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. PhD Dissertation of UC Berkeley.

- Pellicer, M., E. Wegner, L. J. Benstead, and E. Lust. 2021. “Poor People’s Beliefs and the Dynamics of Clientelism.” Journal of Theoretical Politics 33 (3): 300–332. online first. doi:10.1177/09516298211003661.

- Permanent Electoral Authority. 2016. Ghidul finanţării campaniei electorale la alegerile locale din anul 2016. Available at: https://lege5.ro/Gratuit/geydmmbshezq/ghidul-finantarii-campaniei-electorale-la-alegerile-locale-din-anul-2016-din-18042016.

- Piattoni, S., edited by. 2001. Clientelism, Interests, and Democratic Representation: The European Experience in Historical and Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Power, R. A., and M. Pluess. 2015. “Heritability Estimates of the Big Five Personality Traits Based on Common Genetic Variants.” Translational Psychiatry 5(7): pp.e604–4. Nature Publishing Group, 10.1038/tp.2015.96

- Romanian Government. 2012. Emergency Decree 67/2012. Available at: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/142652.

- Roper, S. D. 2002. “The Influence of Romanian Campaign Finance Laws on Party System Development and Corruption.” Party Politics 8 (2): 175–192. doi:10.1177/1354068802008002002.

- Rotaru, V. 2020. ‘Mită electorală dată de PSD Iași, în campania pentru alegerile locale 2020’, BZI.ro, 1 September. Available at: https://www.bzi.ro/mita-electorala-data-de-psd-iasi-in-campania-pentru-alegerile-locale-2020-imagini-socante-cu-zeci-de-oameni-momiti-cu-mici-bautura-si-manele-in-plina-perioada-de-crestere-a-cazurilor-de-covid-19-4015915.

- Stead, R., and G. C. Fekken. 2014. “Agreeableness at the Core of the Dark Triad of Personality.” Individual Differences Research 12 (4–A): 131–141.

- Stokes, S. C. 2009. “Political Clientelism.” In The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Politics, edited by C. Boix and S. C. Stokes, 604–627. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Terpstra, D. E., E. J. Rozell, and R. K. Robinson. 1993. “The Influence of Personality and Demographic Variables on Ethical Decisions Related to Insider Trading.” The Journal of Psychology 127 (4): 375–389. doi:10.1080/00223980.1993.9915573.

- Toma, M. 2020. Candidatul PSD la o primărie din județul Arad și-a pus soția, mama, soacra și fina pe lista de consilieri: “Și la celelalte partide e la fel” Citeşte întreaga ştire: Candidatul PSD la o primărie din județul Arad și-a pus soția, mama, soacra și fina pe lis, Libertatea.

- Transparency International. 2021.

- Vaughan-Johnston, T. I., M. Ke, F. Lr, E. LE, and L. Wasylkiw. 2021. “Extraversion as a Moderator of the Efficacy of Self-Esteem Maintenance Strategies.” Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin 47 (1): 131–145. doi:10.1177/0146167220921713.

- Weinschenk, A. C., and C. T. Dawes. 2018. “Genes, Personality Traits, and the Sense of Civic Duty.” American Politics Research 46 (1): 47–76. doi:10.1177/1532673X17710760.

- Wilkinson, S. I. 2006 ‘Patrons, Clients, and Policies: Patterns of Democratic Accountability’, ( 2004).

- Yıldırım, K., and H. Kitschelt. 2020. “Analytical Perspectives on Varieties of Clientelism.” Democratization 27 (1): 20–43. doi:10.1080/13510347.2019.1641798.

Appendices Appendix 1.

Variable codebook

We use a slightly modified of the Ten-Item Personality Inventory that has a seven-point scale for answers. We use an 11-point scale to have it consistent with the acceptance of clientelism and other measures in the survey.