Abstract

This study uses a framework of a food safety management system-diagnostic instrument (FSMS-DI), for the assessment of the context of a Chinese edible oil manufacture through the view of a case study, and an evaluation of the performance of the FSMS of a Chinese edible oil company. The study includes a structured interview with the quality assurance manager. FSMS-DI is used to diagnose the core control and assurance activities, as well as the riskiness of context factors and output of the system. A factory tour is done to verify the information collected during the interview. The company is operating in a low to moderate risk context. The control activities are overall operating at an advanced level, while the assurance activities are at an average level. Although the food safety output of the FSMS is good, improvements are advised on the assurance activities to develop towards a more robust FSMS. This study gives an insight into the current situation of implemented FSMS in view of the context riskiness of the food business. Quantitative studies and further exploration of typical Chinese context characteristics may help food safety authorities, supporting (branch of industry) organisations, and food companies to advance towards a more effective food safety control in the food sector.

1. Introduction

In the last decade, several serious food scandals have occurred in China, such as contaminated milk and gutter oil (Lu & Wu, Citation2014; Xiu & Klein, Citation2010). In order to regain consumer trust in food safety, food manufacturers are now increasingly adopting quality assurance (QA) guidelines and standards, such as good manufacturing practices (GMP), hazard analysis critical control points (HACCP), British Retail Consortium (BRC), and ISO 22000 (Trienekens & Zuurbier, Citation2008), to establish their company-specific food safety management systems (FSMSs) (Luning & Marcelis, Citation2009; Luning et al., Citation2009). A FSMS is part of a quality management system aimed at controlling and assuring food safety (Luning & Marcelis, Citation2009). The performance of a FSMS depends on the control and assurance activities and on the system’s context riskiness (Kirezieva, Nanyunja, et al., Citation2013 Luning, Marcelis, et al., Citation2011). Not only the specific features of each food production system and the unique organisational context, but also the food supply chain and food safety governance characteristics can impact FSMS performance if not adapted to its context riskiness. Various tools have been developed to evaluate the performance of FSMSs (Jacxsens et al., Citation2009, Citation2010, Citation2011; Jasson, Jacxsens, Luning, Rajkovic, & Uyttendaele, Citation2010; Luning, Bango, Kussaga, Rovira, & Marcelis, Citation2008; Luning & Marcelis, Citation2009; Luning, Marcelis, et al., Citation2011). FSMSs can be assessed in view of the narrow and broad context of the systems (Kirezieva, Jacxsens, et al., Citation2015; Kirezieva, Nanyunja, et al., Citation2013; Luning, Marcelis, et al., Citation2011). Initially, the diagnostic tools were developed for the assessment of systems within the European context and General Food Law, but it was extended for measuring of FSMSs in non-European companies (see with an overview of empirical studies). Nevertheless, studies on FSMSs in the Chinese food sector are yet limited to factors affecting adoptions and implementations of food safety and quality standards (Bai, Ma, Yang, Zhao, & Gong, Citation2007; Jin, Zhou, & Ye, Citation2008; Zhou, Helen, & Liang, Citation2011). However, it is expected that the Chinese context (such as legal framework and organisational characteristics) is different and could have another impact on the design and long-term operation of implemented systems.

Table 1. Empirical studies of FSMS-DI (modified from Nanyunja et al., Citation2015).

This study uses the existing framework of FSMS-diagnostic instruments (DIs), for a first assessment of the context of the Chinese food industry through the view of a case study, and an evaluation of the performance of the FSMS of a Chinese edible oil company.

2. Materials and methods

The study started with a structured interview with the QA manager of a Chinese oil company to get an insight into the essential information about the company. An existing FSMS-DI was used to diagnose the levels of the core and assurance activities, as well as the riskiness of context factors, and the system output level. The instrument consists of indicators and for each indicator, different situational descriptions were made to enable the judgement of the actual performance and context riskiness. During the interview, the QA manager was asked to choose for each indicator which situation represented best the actual company situation. Additional discussions of practices or concepts that might affect the quality performance were encouraged. The interview was recorded under the permission of company A. The conversation was listened to by another researcher from our group to make sure there was no misunderstanding. The interview lasted about an hour. Following the interview, a factory tour was conducted to verify the collected information and assessment. Members of the QA team from every department joined the factory tour. During the tour of the laboratory, the QA team described the daily work of the laboratory and functions of the testing equipment, as well as files used to keep records.

2.1. Characterisation of the company

A private edible oil manufacturer (company A) has been selected for the case study. Founded in 1993, company A has its global business layout in Asia, Africa, South America, North America, and Europe. Needed by the international trade, it has certifications of ISO 9000, ISO 14001, and ISO 22000. Company A owns an area of 59,600 m2 and has a storage capacity of 220,000 tons. It has an oil and fat processing base with the largest capacity in China. It currently has the capacity to produce 700,000 tons of refined, bleached, and deodorised oil and 1.35 million tons of fractionated oil on an annual basis.

2.2. Principles of FSMS-DI

The general theory behind the FSMS-DI is the contingency theory. Contingency theory implies that an organisation should adapt its structure to the contextual situation to attain good performance (Sousa & Voss, Citation2008). In the contingency theory, three types of variables have been identified. Contextual (or contingency) variables represent situational characteristics usually exogenous to the organisation or manager. Response variables are the organisational or managerial actions taken in response to current or anticipated contingency factors. Performance variables are the dependent measures and represent specific aspects of effectiveness that are appropriate to evaluate the fit between contextual variables and response variables for the situation under consideration (Sousa & Voss, Citation2008).

Following the contingency theory, FSMS-DI includes three kinds of variables. The tool includes an assessment of the contextual situation with its variables (i.e. context factors) in terms of characteristics of the context that affect the decision-making during FSMS activities (Luning, Marcelis, et al., Citation2011). The response variables are represented by the systematic analysis of which activities (i.e. core control and assurance activities) are addressed within the company-specific FSMS and an assessment of the levels at which these activities are executed (Luning et al., Citation2008; Luning & Marcelis, Citation2009). The assessment of the performance variables (i.e. system output) is done through key food safety performance indicators (Jacxsens et al., Citation2010).

2.3. Framework of FSMS-DI

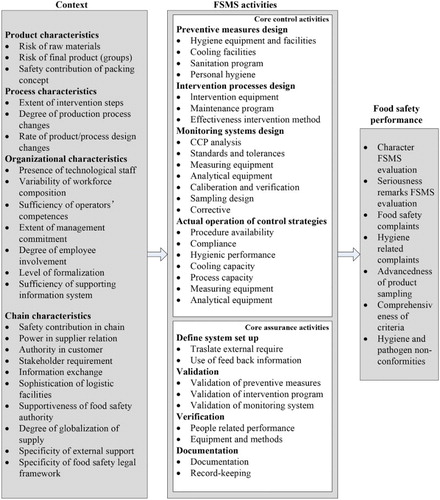

To diagnose the status of the FSMS, the relation between the context and the FSMS is described in terms of riskiness to decision-making within the FSMS. Differences in riskiness in the context have been described by using three criteria: uncertainty due to lack of information, ambiguity due to lack of understanding, and vulnerability due to sensitivity towards contamination in the product, process, or chain environment (Luning, Marcelis, et al., Citation2011).

The context indicators include product characteristics (3 indicators), process characteristics (3 indicators), organisation characteristics (7 indicators), and chain characteristics (10 indicators). For each context indicator, three levels have been defined, which represent low (score 1), moderate (score 2), or high (score 2) risk (Kirezieva, Nanyunja, et al., Citation2013; Luning, Marcelis, et al., Citation2011). The respondents were asked to choose the situation which best represented their company situation. A more risky context corresponds to more vulnerability to safety problems, ambiguity (i.e. lack of insight into underlying mechanisms), and uncertainty (i.e. lack of information), and requires more advanced control and assurance activities. Uncertainty can be reduced by adequate information and systematic methods; ambiguity, by scientific information; and vulnerability, by systematic methods and independent positions (Luning, Marcelis, et al., Citation2011). More advanced control and assurance activities are described as being based on scientific input, using company-specific information, structured analysis, procedure driven, and independent assurance (Luning et al., Citation2008, Citation2009; Sampers et al., Citation2010).

The FSMS activities include core control activities and assurance activities. Indicators of core control activities include design of preventive measures (four indicators), design of intervention processes (three indicators), design of monitoring systems (seven indicators), and operation of measures and systems (seven indicators). And indicators of core assurance activities include defining system set-up (two indicators), validation activities (three indicators), verification activities (two indicators), and documentation and record-keeping (two indicators). For each activity, FSMS-DI offers four levels. They are not applied (score 0), low level (score 1), basic level (score 2), average level (score 3), and advanced level (score 3). The FSMS performing on a higher level of activity is better able to achieve a safety outcome and will provide a better guarantee of a more effective and reliable FSMS (Luning et al., Citation2008, Citation2009).

The third part of FSMS-DI includes the assessment of the food safety output of the system. Indicators were divided into indicators to evaluate the external system (n = 4) and internal system (n = 3). For each indicator, four different levels were defined, representing absence (score 0), poor (score 1), moderate (score 2), and good (score 3) food safety output (Jacxsens et al., Citation2010). presents examples of indicators in FSMS-DI and descriptions of mechanisms and different levels.

Table 2. Examples of indicators from FSMS-DI (Kirezieva, Nanyunja, et al., Citation2013; Luning, Marcelis, et al., Citation2011).

Following the contingency theory, the concept behind the diagnostic tool is: if there is high context riskiness, then advanced FSMS activities are required to achieve a predictable and controllable output. The system output represents the probability of food safety failures, leading to adverse health effects. Structured information about the FSMS output through its key food safety performance indicators, according to very strict and specific criteria, will provide a better insight into the actual performance, because food safety hazards will be more systematically detected (Jasson et al., Citation2010). The assessment with the diagnostic tool provides an insight into the FSMS activities and system output in view of the context riskiness.

The framework of the FSMS-DI as used in this research includes the indicators from the original instrument (Luning, Marcelis, et al., Citation2011) and the more recent instrument that was adapted for the global context (Kirezieva, Nanyunja, et al., Citation2013) as presented in . Data were analysed with Microsoft Office Excel to make spider web diagrams to illustrate visually the scores for the separate indicators for FSMS activities, food safety output, and context factors.

Figure 1. Framework of FSMS-DI (combined from Kirezieva, Nanyunja, et al., Citation2013; Luning, Marcelis, et al., Citation2011).

3. Results and discussion

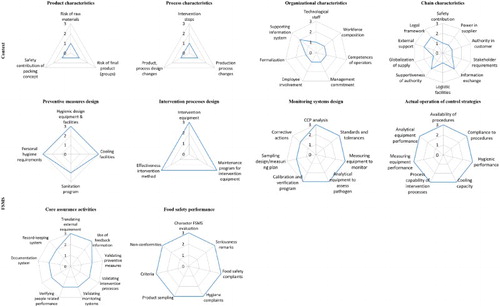

3.1. Context factors

shows that company A operates in a low to moderate risk context. Product characteristics, which imply the riskiness of the product itself, are at a low risk level. The raw material used is crude oil, which is imported from a certified palm farm where QAs (e.g. GAP) are mandatory. Before the crude oil enters the produce line, it is tested three times (when delivered to the factory, when entering the storage tank, and when entering the product line) to ensure that it meets the legal demands (e.g. GB/T 27320-2010). Moreover, due to the oil’s intrinsic properties, both the initial and the final palm oil are not susceptible to pathogens. The process of blow moulding the packing plastics is done inside the same factory within an integrated control system, which puts the score for the indicator ‘extent of safety contribution of packing concept’ at the low risk level.

Figure 2. Results of FSMS-DI in company A. A higher score in web diagram is associated with a higher, more sophisticated level of control and assurance activities, and a better system output. While a higher score is associated with a more risky level of context.

Process characteristics, which refer to the properties of the production process that may increase the chance of cross-contamination, are assigned as low risk level. This is because of the high modernisation of process design. Several critical process steps are designed in the continuous flow processes, such as 260 centigrade heat. A high degree of automation can be found during the changes between different volumes or distinctive products, and human-related interference is restricted. No major changes in the design of a produce or process are made in the recent two years.

Organisational characteristics, which give an insight into the ability to prevent safety problems, are generally in a low risk situation. Company A has low personnel turnover rate and no part-time workers, which decrease the chance of poor execution of people-related tasks. Besides, specific requirements on education background and working experience are required during recruitment. And training programmes would be carried out regularly. After years of implying FSMS, a high-level formalisation QA-based FSMS has already been set up and operated. An internal laboratory with qualified staff is established for regular test and analysis. All employees, including top manager, technological staff, and workforce, are trained to follow the FSMS’s instruction, and are willing to participate in the design and update of the FSMS. It is worth mentioning that the QA team includes people not only from the QA department, but also from other departments (i.e. sales department, R&D department, and human resource department). Integrating the QA team by breaking the walls between different departments helps the QA team gain insights of the performance of the FSMS.

However, a moderate risk level is assigned to sufficiency of the supporting information system. Company A has an advanced online information system; all information and data related to production are collected by the system, not specific for quality management. Besides, only authorised people (e.g. top managers) have access to the information system, which records information and data systematically. Operators who directly deal with the product line cannot reach the latest information and data. This may lead to information asymmetry in food safety decision.

Chain environment characteristics, which refer to the position of the manufacturer in the food chain and its relationship with stakeholders such as suppliers and controlling bodies, are in low to moderate risk level. Stakeholders of company A follow the national edible oil control requirements such as guo biao (GB), which stands for national standard. That assigns the severity of stakeholder requirements in low risk. Since company A occupies the core position of the edible oil supply chain, it has a strong impact on the final product safety. Therefore, company A is able to influence the FSMS of suppliers and customers to follow its FSMS. This illustrates the low risk level of safety contribution in chain position, the extent of power in supplier relationships, and the degree of authority in customer relationships.

The raw material suppliers are overseas farms, which is supposed to increase the risk level. However, those suppliers and company A are under the control of the same international enterprise. With the coordination of the enterprise, they follow the same regulations (e.g. GAP and ISO 22000). This keeps the risk of globalisation of the supply at a low level. The low risk score for the logistic facilities is the result of the management practices of the Chinese Customs Bonded Area, where company A locates in. Bonded Area is designed to provide companies which deal with international trade with assistance service on storage, tariff, and international shipping. Storage and shipping conditions are under strict control, which is in line with international codes.

However, moderate risk can be found in ‘supportiveness of food safety authority’, ‘specificity of external support’, and ‘specificity of food safety legal framework’. The ineffectiveness of the national food safety control system of China is responsible for such risk. According to one member of the QA team, company A, like other food companies in China, is facing lots of inspections, including regular check and spot-check. During inspections, sampling is legislation based, instead of risk based. After inspections, feedbacks are provided. However, follow-up activities (e.g. recheck) are absent. Compared to inspections, less support (e.g. subsidy) is received from regulators. Only a 40-hour training programme is provided every year, which lasts about one week. And scientific documents can only be accessed after payment. Despite the regulators’ best intentions, food safety legislation still needs improvements to become a solid basis for national food safety control. More support suited to local production conditions and a clear legal framework for coherent regulatory integration would be more helpful (Yasuda, Citation2015). Lack of follow-up activities and well-established legislation, and restricted access to experts or documentations may weaken the enforcement of inspection and put more requirements on the validation activities of the FSMS.

Moderate risk level can also be found in ‘information exchange in supply chain’, like what happened inside the company. Information will only be provided as required. This can be explained as the result of carefulness of top managers. They prefer to keep information within a limited group, instead of sharing with the supply chain. However, this may lead to delay in reaction when intervention activities (e.g. recall) are needed. Thus, more efforts need to be put on the documentations of assurance activities in the FSMS.

3.2. Core control activities

Control activities concern the ongoing process of evaluating the performance of both technological and human processes and taking corrective actions when necessary, including all strategies aimed at keeping the product and process conditions within acceptable safety limits (Luning et al., Citation2008).

shows the flow diagram of an edible oil produce. Taking the physical characteristics of an edible oil and the sophistication of the edible oil produce into consideration, the FSMS of the edible oil company relies heavily on the modernisation of procedure design and advance equipment. In our case, company A has all their equipment and facility, including cooling facilities, intervention equipment (e.g. filter), measuring equipment (e.g. pressure meter), and analytical equipment (e.g. laboratory equipment and supplies), modified and integrated for its specific food production characteristics in collaboration with equipment suppliers. This contributes to the advanced levels of equipment-related indicators.

Besides equipment-related indicators, advanced levels can also be found in other control activities. Standards and tolerances of processes are specially designed for company A’s situation, and are also in line with legislation and hygiene code. Maintenance and calibration for equipment and facilities are both designed based on regular test data, and records are kept by company A. Both analysis of CCP and effectiveness of the intervention method are based on scientific literature and the special situation of company A. Regular tests are conducted by external experts. Besides, company A is strictly following regulation from the local Food and Drug Administration, which is detailed and places strict demands on hygiene standards. This contributes to the advanced level of ‘hygiene equipment and facilities’ and ‘personal hygiene’. What is more, the actual operations of equipment and systems are all at the advanced level, which is confirmed by the factory tour and documentations.

However, the preventive activity ‘specificity of sanitation programme’ received score 2 (average level) because the sanitation programme is based on advices of suppliers. Although the suppliers advise different cleaning programmes to clean the equipment and ground, the actual hygiene performance of the whole plant, where those equipment operate, needs to be taken into consideration (Xiang, Citation2015). Thus, decisions based on a special procedure may lead the specificity of the sanitation programme to a more advanced level.

Score 2 (average level) was also given to monitoring activities ‘specificity of sampling design/measuring plan’ and ‘extent of corrective actions’. First, both the sampling and corrective actions are based on hygiene codes and legislation, and not on the statistical analysis of the situation in the own production process. Second, corrective actions based on legislation and guidelines may lack diversity and systematic analysis, which may lead to ineffectiveness of corrective actions. Since different deviations need different corrective actions, results of sampling and measuring can be used to detect the deviation, and then corrective actions will be performed to minimise the deviation and make sure the deviation is under control. Adjusting the sampling and corrective actions to different situations could lead to achieving a more advanced level.

3.3. Core assurance activities

Core assurance activities are activities that provide evidence and confidence to stakeholders that safety requirements will be met. It is assumed for assurance activities that a better activity level is better able to provide confidence that safety requirements will be met because better requirements are set on the system, its performance is better evaluated, and changes are better organised (Luning et al., Citation2009). Company A has ISO 22000-based FSMS certification in which assurance activities such as validation, verification, and documentation are mandatory. From , we can see that the core assurance activities are performing on average to advanced level.

The advanced level was assigned to defining system set-up (e.g. translating external requirement and systematic use of feedback information). It can be explained that the QA department regularly searches for new legislation and guidelines. After analysis of the potential changes in requirements from stakeholders, the QA department will follow the changes, update the FSMS regularly, and systematically document those updates. Meanwhile, the translation process incorporates the requirements from stakeholders when designing and modifying the FSMS. Thus, information derived from feedback is used in updating and modification of the FSMS.

Validation and verification are two very important core assurance activities in an FSMS, because the level of validation and verification activities gives credence to the control measures in place. However, average level is assigned to the validation activities and verification activities. Because both of them are operated by internal experts from the QA department of company A, not by the independent third-party experts. Since validation is obtaining evidence that the food safety control measures managed by the FSMS are capable of being effective, and verification confirms that food safety hazards are within identified acceptable levels and demonstrated conformity to planned arrangements, they become the basis for identifying the need for updating or improving the FSMS. Absence of third-party experts makes the evidence provided by validation and verification less convincing. A more scientific evidence-based, systematic, and independent validation and verification would improve the FSMSs of the companies in the long-term operation.

Score 2 (average level) was assigned for documentation and record-keeping, because the manufacturer keeps all the information and data collected from the produce line to the authorised people, such as top manager and QA manager. Sharing information and data with all workforce may eliminate the information asymmetry, and then lead to a more advanced level.

3.4. Performance

The food safety performance provides information about the output level of the FSMS. It is assumed that a better level is associated with a better system performance, which means that the likelihood of food safety problems is reduced (Jacxsens et al., Citation2010). As noticed in , company A scores 3 in all indicators, which can be illustrated as follows. On one hand, company A has certifications authorised by different parties, including national food safety regulation (e.g. GB) and independent third party (e.g. ISO 22000), which are needed by the international trade. Since company A strictly follows the requirements of national food safety regulation, no serious remark has been received. Although the complaint registration system receives some complaints from customers, none of them is hygiene related or safety related. For example, the recent complaint is about the size of letters on the label. On the other hand, inside the company, regular sampling is operated to test the raw material, final product, and environment, which is required by legislation and stakeholders. And results of the sampling test are explained according to legislation, requirements from stakeholders, and company A’s own criterion. And according to the non-conformities registration documents, there are no non-conformities in last three years, which indicates a good food safety performance.

Prior study finds out that both internal fit with the organisational structure and external fit with the environment affect performance (Zhang, Linderman, & Schroeder, Citation2012). In our case, some weak points of the FSMS can also be pointed out from the context view.

To begin with, it is obvious that the core assurance activities are not as advanced as the core control activities. Chain characteristics and organisational characteristics can be used to explain the differences. In the view of chain characteristics, some regulatory requirements strictly focus on control activities for ensuring food safety. For example, Food Safety Law (2015), the basic legislation for food safety control, provides a detailed description of control activities, which focus on food safety. Some supporting guidelines (e.g. Food Defense Plan GB/T 27320-2010) also provide specific descriptions for applications of control activities. As company A follows these requirements, technology-dependent control activities become the strong points, and managerial QA activities become weak points. In the view of organisational characteristics, it is also well recognised by managers that assurance activities take more time and money to implement, and they do not usually bring economic benefit to the company directly. According to one QA member, control activities are more close to produce. And to company, produce is the priority. Thus, control activities gain the commitment of managers, while assurance activities receive less attention. These explanations can also be used to illustrate similar situations observed in prior studies (Kirezieva, Luning, et al., Citation2015; Luning et al., Citation2015; Sampers, Toyofuku, Luning, Uyttendaele, & Jacxsens, Citation2012).

Meanwhile, the deficiency of documentation and record-keeping can also be explained through the view of organisational characteristics. As we mentioned, the manager of company A would like to keep produce information in a limited group, instead of sharing with all employees. That actually adds burden on information-related activities of the FSMS. Since employees have no access to latest data and information from production, they are not able to organise documentation or update data. Besides, without access to data and information, employees would depend more on experience, instead of science-based information (Luning et al., Citation2015). This may make validation and verification weak points in the long-term business operation. Providing access to produce information would support employees in quality systems to make informed and predictable decisions, reducing the chance on safety problems. That would contribute to a sustainable FSMS.

4. Conclusion

In this case study, we used an existing diagnostic tool to assess the performance of a FSMS in a Chinese edible oil manufacturer, as well as the context riskiness wherein the FSMS operates. The company operated in a low to moderate risk context; most of the control activities are at an advanced level, whereas the assurance activities are at an average level. This means that they are not tailored to the company-specific situation. Assurance activities are crucial for the long-term reliability of the performance of a FSMS, because they provide evidence and confidence that the system is effective and is working according to its design. Our following study will focus on the typical Chinese context characteristics that need to be further explored to get a deeper understanding of (context) factors that influence the food safety output of implemented systems in the Chinese food sector.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank company A for the participation. We would also like to thank Prof. Jens J. Dahlgaard, Prof. Su Mi Dahlgaard-Park, and Prof. Muhammad Asif for their valuable comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bai, L., Ma, C.-L., Yang, Y.-S., Zhao, S.-K., & Gong, S.-L. (2007). Implementation of HACCP system in China: A survey of food enterprises involved. Food Control, 18(9), 1108–1112. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2006.07.006

- Jacxsens, L., Kirezieva, K., Luning, P. A., Ingelrham, J., Diricks, H., & Uyttendaele, M. (2015). Measuring microbial food safety output and comparing self-checking systems of food business operators in Belgium. Food Control, 49, 59–69. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.09.004

- Jacxsens, L., Kussaga, J., Luning, P. A., Van der Spiegel, M., Devlieghere, F., & Uyttendaele, M. (2009). A microbial assessment scheme to measure microbial performance of food safety management systems. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 134(1–2), 113–125. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.02.018

- Jacxsens, L., Luning, P. A., Marcelis, W. J., van Boekel, T., Rovira, J., Oses, S.,, … Uyttendaele, M. (2011). Tools for the performance assessment and improvement of food safety management systems. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 22, S80–S89. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2011.02.008

- Jacxsens, L., Uyttendaele, M., Devlieghere, F., Rovira, J., Gomez, S., & Luning, P. A. (2010). Food safety performance indicators to benchmark food safety output of food safety management systems. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 141, S180–S187. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168160510002618 http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0168160510002618/1-s2.0-S0168160510002618-main.pdf?_tid=811560a8-5340-11e4-8fff-00000aab0f6b&acdnat=1413249903_4eec31225900eddb706d7ace76a50e72

- Jasson, V., Jacxsens, L., Luning, P., Rajkovic, A., & Uyttendaele, M. (2010). Alternative microbial methods: An overview and selection criteria. Food Microbiology, 27(6), 710–730. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0740002010000821 http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0740002010000821/1-s2.0-S0740002010000821-main.pdf?_tid=86e06d34-5340-11e4-b3e1-00000aab0f01&acdnat=1413249913_715a06b7062d84c8f07a56e02d0dc5e5

- Jin, S., Zhou, J., & Ye, J. (2008). Adoption of HACCP system in the Chinese food industry: A comparative analysis. Food Control, 19(8), 823–828. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2008.01.008

- Kirezieva, K., Jacxsens, L., Hagelaar, G. J. L. F., van Boekel, M. A. J. S., Uyttendaele, M., & Luning, P. A. (2015). Exploring the influence of context on food safety management: Case studies of leafy greens production in Europe. Food Policy, 51, 158–170. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2015.01.005

- Kirezieva, K., Jacxsens, L., Uyttendaele, M., Van Boekel, M. A. J. S., & Luning, P. A. (2013). Assessment of food safety management systems in the global fresh produce chain. Food Research International, 52(1), 230–242. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2013.03.023

- Kirezieva, K., Luning, P. A., Jacxsens, L., Allende, A., Johannessen, G. S., Tondo, E. C.,, … van Boekel, M. A. J. S. (2015). Factors affecting the status of food safety management systems in the global fresh produce chain. Food Control, 52, 85–97. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.12.030

- Kirezieva, K., Nanyunja, J., Jacxsens, L., van der Vorst, J. G. A. J., Uyttendaele, M., & Luning, P. A. (2013). Context factors affecting design and operation of food safety management systems in the fresh produce chain. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 32(2), 108–127. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2013.06.001

- Kussaga, J. B., Luning, P. A., Tiisekwa, B. P., & Jacxsens, L. (2014). Challenges in performance of food safety management systems: A case of fish processing companies in Tanzania. Journal of Food Protection®, 77(4), 621–630.

- Lahou, E., Jacxsens, L., Verbunt, E., & Uyttendaele, M. (2015). Evaluation of the food safety management system in a hospital food service operation toward Listeria monocytogenes. Food Control, 49, 75–84. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.10.020

- Lu, F., & Wu, X. (2014). China food safety hits the “gutter”. Food Control, 41, 134–138. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.01.019

- Luning, P. A., Bango, L., Kussaga, J., Rovira, J., & Marcelis, W. J. (2008). Comprehensive analysis and differentiated assessment of food safety control systems: A diagnostic instrument. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 19(10), 522–534. Retrieved from http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0924224408000794/1-s2.0-S0924224408000794-main.pdf?_tid=69099016-533f-11e4-9df8-00000aab0f6c&acdnat=1413249433_c41020da109eb181394785314fad4029

- Luning, P. A., Chinchilla, A. C., Jacxsens, L., Kirezieva, K., & Rovira, J. (2013). Performance of safety management systems in Spanish food service establishments in view of their context characteristics. Food Control, 30(1), 331–340. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2012.06.040

- Luning, P. A., Jacxsens, L., Rovira, J., Osés, S. M., Uyttendaele, M., & Marcelis, W. J. (2011). A concurrent diagnosis of microbiological food safety output and food safety management system performance: Cases from meat processing industries. Food Control, 22(3–4), 555–565. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2010.10.003

- Luning, P. A., Kirezieva, K., Hagelaar, G., Rovira, J., Uyttendaele, M., & Jacxsens, L. (2015). Performance assessment of food safety management systems in animal-based food companies in view of their context characteristics: A European study. Food Control, 49, 11–22. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.09.009

- Luning, P. A., & Marcelis, W. J. (2009). A food quality management research methodology integrating technological and managerial theories. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 20(1), 35–44. Retrieved from http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0924224408002446/1-s2.0-S0924224408002446-main.pdf?_tid=ad935b04-533f-11e4-ad17-00000aab0f6c&acdnat=1413249548_a84b744cf25f3161f0f8602d9f9d1e75

- Luning, P. A., Marcelis, W. J., Rovira, J., van Boekel, M. A. J. S., Uyttendaele, M., & Jacxsens, L. (2011). A tool to diagnose context riskiness in view of food safety activities and microbiological safety output. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 22, S67–S79. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2010.09.009

- Luning, P. A., Marcelis, W. J., Rovira, J., Van der Spiegel, M., Uyttendaele, M., & Jacxsens, L. (2009). Systematic assessment of core assurance activities in a company specific food safety management system. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 20(6–7), 300–312. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2009.03.003

- Nanyunja, J., Jacxsens, L., Kirezieva, K., Kaaya, A., Uyttendaele, M., & Luning, P. (2015). Assessing the status of food safety management systems for fresh produce production in east Africa: Evidence from certified green bean farms in Kenya and noncertified hot pepper farms in Uganda. Journal of Food Protection®, 78(6), 1081–1089.

- Onjong, H. A., Wangoh, J., & Njage, P. M. (2014). Semiquantitative analysis of gaps in microbiological performance of fish processing sector implementing current food safety management systems: A case study. Journal of Food Protection, 77(8), 1380–1389. doi:10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-13-511

- Osés, S. M., Luning, P. A., Jacxsens, L., Santillana, S., Jaime, I., & Rovira, J. (2012). Food safety management system performance in the lamb chain. Food Control, 25(2), 493–500. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2011.11.018

- de Quadros Rodrigues, R., Loiko, M. R., Minéia Daniel de Paula, C., Hessel, C. T., Jacxsens, L., Uyttendaele, M.,, … Tondo, E. C. (2014). Microbiological contamination linked to implementation of good agricultural practices in the production of organic lettuce in Southern Brazil. Food Control, 42, 152–164. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.01.043

- Sampers, I., Jacxsens, L., Luning, P. A., Marcelis, W. J., Dumoulin, A., & Uyttendaele, M. (2010). Performance of food safety management systems in poultry meat preparation processing plants in relation to Campylobacter spp. contamination. Journal of Food Protection®, 73(8), 1447–1457.

- Sampers, I., Toyofuku, H., Luning, P. A., Uyttendaele, M., & Jacxsens, L. (2012). Semi-quantitative study to evaluate the performance of a HACCP-based food safety management system in Japanese milk processing plants. Food Control, 23(1), 227–233. Retrieved from http://ac.els-cdn.com/S095671351100291X/1-s2.0-S095671351100291X-main.pdf?_tid=a23a8486-5343-11e4-8f74-00000aab0f27&acdnat=1413251247_ebc4ac4c91b5d445bcc78232856663d4

- Sawe, C. T., Onyango, C. M., & Njage, P. M. K. (2014). Current food safety management systems in fresh produce exporting industry are associated with lower performance due to context riskiness: Case study. Food Control, 40, 335–343. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.12.019

- Sousa, R., & Voss, C. (2008). Contingency research in operations management practices. Journal of Operations Management, 26(6), 697–713. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2008.06.001

- Trienekens, J., & Zuurbier, P. (2008). Quality and safety standards in the food industry, developments and challenges. International Journal of Production Economics, 113(1), 107–122. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S092552730700312X http://ac.els-cdn.com/S092552730700312X/1-s2.0-S092552730700312X-main.pdf?_tid=79d0dd1e-533f-11e4-aee5-00000aab0f01&acdnat=1413249462_c5988b53c6108e2238a652fd02e5dda8

- Xiang. (2015). Sichuan: The introduction of “Sichuan food production and quality and safety management practices”. China Food, (2), 50–50. (Published in Chinese)

- Xiu, C., & Klein, K. K. (2010). Melamine in milk products in China: Examining the factors that led to deliberate use of the contaminant. Food Policy, 35(5), 463–470. Retrieved from http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0306919210000540/1-s2.0-S0306919210000540-main.pdf?_tid=0696fd36-5341-11e4-b3e1-00000aab0f01&acdnat=1413250127_420895b37ce12939c4b1045aaff0aae8

- Yasuda, J. K. (2015). Why food safety fails in China: The politics of scale. The China Quarterly, 223, 745–769. doi:10.1017/s030574101500079x

- Zhang, D., Linderman, K., & Schroeder, R. G. (2012). The moderating role of contextual factors on quality management practices. Journal of Operations Management, 30(1–2), 12–23. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2011.05.001

- Zhou, J., Helen, J. H., & Liang, J. (2011). Implementation of food safety and quality standards: A case study of vegetable processing industry in Zhejiang, China. The Social Science Journal, 48(3), 543–552. doi:10.1016/j.soscij.2011.06.007