Abstract

Lean is often considered as a collection of tools and practices that can be used to achieve superior operational and financial performance. However, there is consensus nowadays that the use of Lean tools and practices is a minimum, but not sufficient condition for successful Lean implementations for which a culture of continuous improvement (CI) and Lean leadership are also necessary. Though a positive connection is made in literature between Lean leadership and the transformational, servant and empowering leadership styles, empirical evidence is scarce. In this paper, we explore the relationships between these upper management leadership styles and Lean. Survey data of 199 responses from Dutch organisations shows that Lean sponsorship and improvement stimulation by higher management is indeed positively related to Lean, though improvement stimulation is particularly related to a culture of CI. Servant leadership is negatively related to the use of Lean tools and empowered leadership is positively related to the use of Lean tools. No relationships are found between the contemporary leadership styles and Lean practices.

1. Introduction

Lean management evolved from a mutually reinforcing set of ‘best practices’ to create world class operations (Schonberger, Citation2007). These practices include (i) just-in-time (JIT) to reduce setup time, create flow and pull-based workload control (Cagliano, Caniato, & Spina, Citation2006; Cua, McKone, & Schroeder, Citation2001), (ii) total quality management (TQM) to prevent quality problems and rework (Flynn, Sakakibara, & Schroeder, Citation1995; Narasimhan, Swink, & Kim, Citation2006) and (iii) human resource development (HRM) to involve and empower employees amongst others (Sakakibara, Flynn, Schroeder, & Morris, Citation1997).

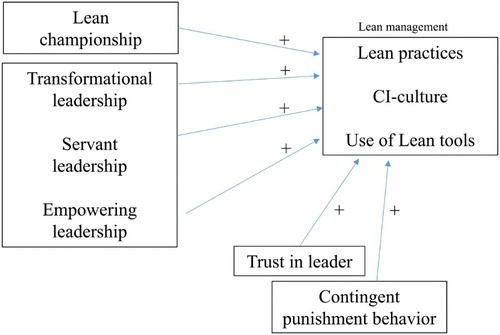

Although Lean was initially considered to be a collection of tools and practices, nowadays there is widespread agreement that particularly the socio-cultural aspects of Lean, including the leadership style, determine the success of a Lean implementation (Mann, Citation2009; Spear & Bowen, Citation1999). Nevertheless, there has been little empirical work which considers linkages between specific types of leadership and Lean (Lam, O'Donnell, & Robertson, Citation2015), though transformational leadership (TL) (Laohavichien, Fredendall, & Cantrell, Citation2011; Sosik & Dionne, Citation1997) and empowering leadership (EL) (Shah & Ward, Citation2003) are associated with Lean leadership, since empowerment, training and coaching are important HRM-practices of Lean. Servant leadership (SL) has also been associated with Lean as it aims to empower and develop employees by providing direction and promoting employee responsibility and teamwork (van Dierendonck, Citation2011; Yoshida, Sendjaya, Hirst, & Cooper, Citation2014), which are key aspects of Lean leadership (Browning & Heath, Citation2009). Besides leadership style, management commitment and corresponding visible management actions also influence the success of Lean implementation (McLachlin, Citation1997), including (i) management as a sponsor of Lean and (ii) improvement stimulation (IS) by management. There is little empirical work that tests the impact of these management actions and behaviours on Lean implementation (Choi & Liker, Citation1995). With this paper, we contribute to the extant literature on Lean by examining both the impact of said management actions and the type of leadership (i.e. transformational, servant and EL) of upper management on Lean, measured by a coherent bundle of Lean practices (Shah & Ward, Citation2003; 2007), the use of operational Lean tools (Belekoukias, Garza-Reyes, & Kumar, Citation2014) and the presence of a culture of continuous improvement (CI) (Liker & Morgan, Citation2006).

The rest of the paper is organised as follows: Section 2 presents a brief review of the relevant literature on Lean management and leadership. The research model and hypotheses are presented in Section 3. Data, variables and research method to validate the research model are discussed in Section 4 and the statistical results are described in Section 5. Discussion of the findings and the implications for practice and (future) research are given in Section 6.

2. Literature review and research model

2.1. Lean management

Lean is generally associated with the elimination of waste commonly held by firms as excess inventory or excess capacity (machine and human capacity) to buffer for variability in customer demand, value streams and processing time (de Treville & Antonakis, Citation2006; Hopp & Spearman, Citation2004). Waste reduction is typically accomplished through the reduction of dysfunctional variability and non-value-added activities with the help of various operational instruments and tools to (i) specify value in terms of the customer (kano-analysis: Lin, Yang, Chan, & Sheu, Citation2010; Ward, Liker, Cristiano, & Sobek, Citation1995), (ii) map the value stream – and eliminate non-value-added tasks (e.g. value stream mapping: Tyagi, Choudhary, Cai, & Yang, Citation2015), (iii) create continuous, single-piece flow wherever possible; (iv) only flow a product when a customer pulls it (with the help of a kanban system or a two-bin system for instance: Landry & Beaulieu, Citation2010) and (v) seek perfection through CI (Spear & Bowen, Citation1999; Womack & Jones, Citation1996; Womack, Jones, & Roos, Citation1990). Mann (Citation2009, p. 15) states, however, that ‘implementing tools represents at most 20 percent of the effort in Lean transformations. The other 80 percent of the effort is expended on changing leaders’ practices and behaviors, and ultimately their mindset’. As a consequence, Lean requires Lean leadership and a flexible, dedicated and engaged work force, which in turn require firms to simultaneously effectively manage their social and technical systems (Shah & Ward, Citation2007). Lean also requires an infrastructure with associated Lean tools, instruments and practices to facilitate a culture of CI (Oliver, Delbridge, Jones, & Lowe, Citation1994). Having a culture of CI is related to the level of professionalism with respect to the use of tactical Lean practices (as an infrastructure) and operational Lean tools, as Lean models and tools provide an efficient and effective method for solving problems (Wu & Chen, Citation2006). The presence of a CI-culture implies the commitment to continuously improving the operational organisation, processes and corresponding infrastructure. A culture of CI also implies the continuous development and ultimately perfection of tools and practices used (Bessant, Caffyn, & Gallagher, Citation2001). Having a CI-culture ensures that more use is made of different Lean tools (Wu & Chen, Citation2006). This view was adopted by Karlsson and Åhlström (Citation1996) and Shah and Ward (Citation2003) in their quest to operationalise Lean by means of Lean principles, practices and tools especially because researchers had already empirically measured just in time (McLachlin, Citation1997; Sakakibara, Flynn, & Schroeder, Citation1993) and TQM (Dean & Bowen, Citation1994; Sitkin, Sutcliffe, & Schroeder, Citation1994) or a combination of JIT and TQM (Flynn et al., Citation1995) by means of practices. Shah and Ward (Citation2007) identifies 10 Lean practices or infrastructural capabilities, including involved customers, supplier feedback, developing suppliers, JIT-delivery capability, flow production capability, pull-control capability, setup reduction capability, controlled processes, productive maintenance and involved employees. Lean is also measured by the extent to which an organisation uses operational Lean tools such as value stream mapping (Tyagi et al., Citation2015).

2.2. Lean leadership

Lean leadership is a set of leadership competencies, practices and behaviours to successfully implement and exploit a Lean manufacturing system (Poksinska, Swartling, & Drotz, Citation2013), including promotion of employee responsibility, employee empowerment, provision of training, promotion of teamwork and team-based problem-solving (Bodek, Citation2008; Cua et al., Citation2001; McLachlin, Citation1997); see . Worley and Doolen (Citation2006) stated that management must particularly create organisational interest in Lean by means of visioning the Lean organisation (Cua et al., Citation2001), and must clearly communicate both the objective of Lean and the required change to everyone within the organisation (Laohavichien et al., Citation2011). Also, the management behaviours collaboration, consultation, ingratiation, inspirational appeals and rational persuasion are significant and strong predictors of employee commitment to CI initiatives (Lam et al., Citation2015). Hence, employee involvement, coaching and developing others, and fostering a culture of trust and respect for staff are important socio-cultural characteristics of Lean leadership (Zu, Robbins, & Fredendall, Citation2010). In contrast, important analytical technical characteristics of Lean leadership include: having high expectations and setting ambitious goals (Linderman et al., Citation2006), management by facts and the utilisation of objective data (Choi & Eboch, Citation1998), timely feedback and information-sharing (Waldman, Citation1993). The management actions and behaviour of Lean leadership are clearly paradoxical in nature (Choi & Eboch, Citation1998; Lewis, Andriopoulos, & Smith, Citation2014) as it incorporates technical aspects such as management on facts, analysis and adhering to the standard operating procedure for the sake of efficiency and effectiveness on the one hand and social, follower-related aspects such as promotion of employee responsibility, empowerment and collaboration to facilitate creativity and stimulate innovation on the other hand (Spear & Bowen, Citation1999). It simultaneously requires the leader to meticulously act and manage consistently and to stand back and empower employees to facilitate creativity and CI. As a consequence, management actions and behaviours of Lean managers are both practice- and performance-focused (and to a certain extent demonstrate self-enhancement behaviour) and others-focused (or even self-transcendent). Based on a brief literature review discussed in this section, we distilled 10 frequently cited management actions and behaviours associated with Lean leadership (see ).

Table 1. Lean leadership behaviour and SL/TL/EL-factors.

2.3. Types of leadership

2.3.1. Transformational leadership

TL is a style of leadership in which the leader identifies the needed change, creates a vision to guide the change through inspiration and executes the change with the commitment of the members of the group. Transformational leaders motivate followers to perform beyond expectations by transforming followers’ attitudes, beliefs and values as opposed to simply gaining compliance (Bass, Citation1991). Typical factors of TL are (1) vision (i.e. the expression of an idealised picture of the future), (2) inspirational communication (i.e. the expression of positive and encouraging messages about the organisation, and statements that build motivation and confidence, (3) intellectual stimulation (i.e. enhancing employees’ interest in and awareness of problems, and increasing their ability to think about problems in new ways), (4) supportive leadership (i.e. expressing concern for followers and taking account of their individual needs) and (5) personal recognition (i.e. the provision of rewards such as praise and acknowledgement of effort for achievement of specified goals) (Rafferty & Griffin, Citation2004).

A transformational leader sets ambitious organisational goals and subsequently encourages and inspires followers to perform beyond expectations to achieve these goals and uses rewards and praise to motivate followers to go the extra mile (Yukl, Citation1989). A transformational leader also serves as a motivating role model (Bass, Citation1991) and communicates a stimulating vision of the desired end-state of the organisation to enhance followers’ work motivation (Shamir, House, & Arthur, Citation1993). TL is therefore likely to result in growth, independence and empowerment of followers (Avolio, Bass, & Jung, Citation1999). An empowered follower is self-motivated and believes in his or her ability to cope and perform successfully, leading to increased innovative performance (Jung, Chow, & Wu, Citation2003) and financial performance (Barling, Weber, & Kelloway, Citation1996).

2.3.2. Servant leadership

SL is also demonstrated by empowering and developing people. It is a style of leadership in which the leader is genuinely concerned with followers (GreenLeaf, Citation1977) aiming to develop followers their fullest potential by putting explicit emphasis on their needs (Stone, Russell, & Patterson, Citation2004). Indeed, the literature on SL advocates that servant leaders must primarily meet the needs of others from a genuine and thorough understanding of their abilities, needs, desires, goals and potential (GreenLeaf, Citation1977) in order to assist and facilitate them to achieve their potential (Liden, Wayne, Zhao, & Henderson, Citation2008). Servant leaders do not see employees as followers but as equals. They empower and develop people; they show humility, are authentic, accept people for who they are, provide direction and are stewards who work for the good of the whole (van Dierendonck, Citation2011). Hence, typical factors of SL are (van Dierendonck, Citation2011; van Dierendonck & Nuijten, Citation2011): (i) empowerment (i.e. encourage a proactive, self-confident attitude among followers that gives them a sense of personal power), (ii) standing back (i.e. retreating into the background, giving priority to the interests of others first, and offering the necessary support and credits when a task has successfully been accomplished; van Dierendonck & Nuijten, Citation2011), (iii) humility (i.e. acknowledging the leader’s own limitations and therefore actively seeking the contributions of others in order to overcome those limitations), (iv) accountability by providing direction (i.e. holding people accountable for performance within their control), (v) authenticity (i.e. expressing oneself in ways that are consistent with inner thoughts and feelings) and (vi) stewardship (i.e. the willingness to take responsibility for the larger institution and to go for service instead of control and self-interest). Other operational definitions of SL use similar factors (Liden et al., Citation2008; Sendjaya & Cooper, Citation2011). SL leads to higher team performance (Schaubroeck, Lam, & Peng, Citation2011), creativity and innovative performance (Yoshida et al., Citation2014) and higher firm performance (Peterson, Galvin, & Lange, Citation2012).

SL theory has both similarities and differences with other leadership theories. TL and SL both express concern for followers and take account of their individual needs (Stone et al., Citation2004). The main difference is that servant leaders are genuinely concerned with followers (GreenLeaf, Citation1977). Empowerment is an important factor of both TL and SL behaviour, but also has many similarities with the notion of EL (Pearce & Sims Jr, Citation2002). A specific leadership factor may therefore be attributed to different types of leadership. Transforming influence, for instance, is a factor of both SL and EL.

2.3.3. Empowering leadership

Empowering as a distinctive type of leadership focuses on influencing others by developing and empowering follower self-leadership capabilities (Conger, Citation1989). It is essentially about encouraging participative decision-making, sharing information and the coaching and mentoring of individuals for increased innovative performance (Konczak, Stelly, & Trusty, Citation2000). Typical factors of EL are (see for instance Arnold, Arad, Rhoades, & Drasgow, Citation2000): (i) leading by example (refers to a set of behaviours that show the leader’s commitment to his or her own work as well as the work of his/her team members), (ii) coaching (refers to a set of behaviours that educate team members and help them to become self-reliant and competent), (iii) encouraging (refers to a set of behaviours that promote high performance), (iv) participative decision-making (refers to a leader’s use of team members’ information and input in making decisions), (v) informing (refers to the leader’s dissemination of company-wide information, such as mission and philosophy, as well as other important information), (vi) showing concern (refers to a collection of behaviours that demonstrate a general regard for team members’ well-being) and (vii) interacting with the team (refers to behaviours that are important when interfacing with the team as a whole).

3. Hypotheses

CI is an important part of Lean management (Huang, Rode, & Schroeder, Citation2011). CI is defined as the systematic effort to seek out and apply new ways of doing work, that is, actively and repeatedly making process improvements (Anand, Ward, Tatikonda, & Schilling, Citation2009). It can hence be viewed in terms of (a) the never-ending reciprocal relationship between process and product/service improvement and increased efficiency and effectiveness, (b) the constant enhancement of customer satisfaction by teamwork, high expectations and open communication with employees, customers and suppliers and (c) management by fact and the use of objective data for analysing/improving processes (Choi & Eboch, Citation1998; Sosik & Dionne, Citation1997). Lean is therefore associated with leadership that facilitates and stimulates the continuous initiation and execution of improvement initiatives and coordination of change projects (Choo, Linderman, & Schroeder, Citation2007; Wu & Chen, Citation2006). We therefore have the following hypothesis:

H1: IS by management is positively related to Lean.

Senior management as sponsors of Lean plays a central role in Lean management to bridge a critical divide: the gap between the use of Lean tools and Lean thinking, that is, principles and practices (Kanning & Bergmann, Citation2009). Management’s praise of Lean is an important prerequisite for successful Lean (Poksinska et al., Citation2013). Indeed, demonstrable top leadership commitment and sponsorship is necessary for the successful implementation of JIT manufacturing (McLachlin, Citation1997), quality improvement efforts (Waldman, Citation1993), Six Sigma (Linderman et al., Citation2006; Linderman, Schroeder, Zaheer, & Choo, Citation2003) and the promotion of improvement models and tools to build a CI-capability (Wu & Chen, Citation2006). Upper management serving as a Lean sponsor has a genuine interest in operational issues and has a certain level of perseverance and is not easily put off by setbacks. After all, for many, the implementation of Lean means a new way of working and a different behaviour. Various barriers must be overcome to reach a situation where the entire organisation continually pursues perfection (Spear & Bowen, Citation1999; Womack & Jones, Citation1996). In fact, when implementing Lean things may occasionally go wrong, something may not go according to plan or improvements may be disappointing; senior management must not give up too easily or put employees under pressure, instead it must take the organisation in tow, give stability and confidence and provide possible solutions (Noone, Namasivayam, & Spitler Tomlinson, Citation2010). Hence, we have the following hypothesis:

H2: Lean sponsorship by management is positively related to Lean.

Empowerment of employees is an important leadership behaviour to stimulate the use operational Lean tools and to perpetuate the development of Lean practices. Indeed, employee empowerment is widely touted as the defining factor of Lean production (Jones, Latham, & Betta, Citation2013); it is an important HR practice of Lean (Shah & Ward, Citation2003) and involves the increase of capabilities, responsibilities, formal authority and involvement of broadly skilled employees in problem-solving, participative decision-making and CI (Vidal, Citation2007). Lean requires that ‘workers must have both a conceptual grasp of the production process and the analytical skills to identify the root cause of problems’ so that they may ‘identify and resolve problems as they appear on the line’ (MacDuffie, Citation1997). Management in a Lean organisation, therefore, inform employees about the arguments why the organisation has adopted Lean, about the current performance and future expectations and about the implications for all involved (Spear & Bowen, Citation1999). Lean leaders are therefore empowering leaders since they encourage employees to adhere to the principles, practices and methods of Lean. They show their commitment to Lean through active involvement and participation. Lean leaders train and coach employees in the adequate use of Lean tools, let them participate in CI projects and they encourage employees to come up with improvement suggestions (Poksinska et al., Citation2013). Lean leaders listen to their followers, weigh up the arguments of all workers and take their interests into account. Indeed, consensus decision-making is one of the most widely employed empowerment actions in Lean production systems (Jones et al., Citation2013). We therefore hypothesise that EL is positively related to both the implementation of Lean practices and the use of Lean tools.

H3: EL is positively related to Lean.

Empowerment requires managers to share information and knowledge that enables employees to contribute optimally to organisational performance (Ford & Fottler, Citation1995). Indeed, the degree to which leaders value participation and teamwork, and information-sharing, will be directly related to their communication behaviours about the importance of teamwork and as such will foster an organisational culture of openness and information-sharing across levels, which is essential for TQM (Lakshman, Citation2006) and Lean (Netland et al., Citation2015). With respect to skill development, Wellins, Byham, and Wilson (Citation1991) described the manager’s role as facilitating and supporting rather than directing and controlling, with a significant proportion of the leader’s time spent on securing appropriate training to ensure that employees develop the skills needed to support empowerment efforts. Lean leaders demonstrate SL behaviour such as promotion of employee responsibility and collaboration to facilitate creativity and stimulate innovation (Spear & Bowen, Citation1999). They also empower and develop employees and provide direction by means of visioning True North (Noone et al., Citation2010). Respect for people is another factor of SL that is also a key principle of Lean (Liker, Citation2004). Given its emphasis on the needs and welfare of followers, SL should encourage a positive social climate in which followers feel accepted and respected. By paying tribute to the workforce at the operational level, Lean leadership is similar to SL (Poksinska et al., Citation2013). We therefore hypothesise that SL is related to Lean.

H4: SL is positively related to Lean.

Sosik and Dionne (Citation1997) hypothesised that TL concurs with Deming’s behaviour factors, but did not provide empirical evidence. Laohavichien et al. (Citation2011) empirically evaluated leadership and quality management practices and found that two factors of TL and one factor of transactional leadership influence quality management practices. Also Jung et al. (Citation2003) found a direct and positive link between a TL style and organisational innovation and in particular with both empowerment and an innovation-supporting organisational climate. Lean leaders aim to support their teams rather than control them (Sosik & Dionne, Citation1997), resulting in higher worker effectiveness and employee creativity due to leader inspirational motivation (Hirst, van Dick, & van Knippenberg, Citation2009). The components of Lean leadership such as empowering employees, participation in goal achievement, and focus on learning and personal responsibility are important aspects of TL (Poksinska et al., Citation2013). We therefore have the following hypothesis:

H5: TL is positively related to Lean.

To sum up, we have a research model as illustrated in .

4. Methodology

4.1. Data collection

The data for this research was collected from participants of various courses and master classes in Operational Excellence at a Dutch business school during the period 2012/2013. Participants were predominantly middle managers. We employed a web-based survey approach that participants were asked to fill out before they attended the class, with the explicit remark that we would use the results anonymously during the course. An estimated 80% of the participants filled out the questionnaire, resulting in 205 questionnaires, of which 199 were useful for research. The respondents averaged 8.5 years of work experience with their current organisation (see ). Non-response bias was evaluated by testing responses of 21 non-informants for significant differences during the courses (e.g. Mentzer & Flint, Citation1997), where they were asked to respond verbally to five substantive items related to key constructs of the whole survey. There were no significant differences (p < .05) in responses to any item, leading to the conclusion that non-response bias was not a problem.

Table 2. Profile of survey respondents.

4.2. Measures, scale development and purification

Though CI is an important part of Lean (Schonberger, Citation2007), it is seldom included in operational definitions of Lean, but is instead often studied as a separate construct (Bessant & Francis, Citation1999; Peng et al., Citation2008). Generally researchers operationalise Lean as either a bundle of Lean practices (Azadegan, Patel, Zangoueinezhad, & Linderman, Citation2013; Flynn et al., Citation1995; Shah & Ward, Citation2007) or as a set of operational Lean tools (Belekoukias et al., Citation2014; Karlsson & Åhlström, Citation1996; Rivera & Chen, Citation2007). To operationalise Lean, we account for the use of operational Lean tools, Lean practices and a culture of CI. To increase the generalisability and applicability of our research, we adapted the familiar operationalisation of Shah and Ward (Citation2007) as a measure of infrastructural Lean practices for both manufacturing and services industries. The final scale includes visual management (VM), pull (Pull), good housekeeping (GH), setup reduction (SR) and flow (Flow). The constructs supplier feedback, JIT-delivery and supplier development were omitted from the scale due to low values of Cronbach’s alpha. Items were estimated through respondents’ perceptual evaluation on a 5-point Likert scale. The response categories for each item were anchored by 1 (strongly disagree) and 5 (strongly agree): see Appendix A1. We evaluated the uni-dimensionality, reliability and convergent validity of each scale in this research using confirmatory factor analysis in the software package AMOS 22. The final second order measurement model of Lean practices fits the data well (Browne & Cudeck, Citation1992): χ2 = 95,715, df = 60, p = .002, CFI = .962, IFI = .963, TLI/NNFI = .994, NFI = .908, RMSEA = .055 (see Table A1). We operationalised ‘Use of Lean tools’ using scales for visual management tools (VMT), pull-control tools (PCT), Kaizen improvement tools (KIT) and root-cause analysis tools (RCT). The final second order measurement model of use of Lean tools fits the data well: χ2 = 32,682, df = 31, p = .384, CFI = .997, IFI = .997, TLI/NNFI = .994, NFI = .943 and RMSEA = .017; see Table A2. CI-culture (Cronbach alpha = 0.75) is operationalised using items from Huang et al. (Citation2011). Subsequently we constructed an aggregate Lean scale based on the variables Lean practices, use of Lean tools and CI-culture that has a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.87.

The constructs Lean sponsorship (LS) (Cronbach alpha = 0.67) and IS by management (Cronbach alpha = 0.78) are operationalised using items from Cua et al. (Citation2001), Douglas and Judge (Citation2001) and Flynn, Schroeder, and Flynn (Citation1999). The measurement model with these two constructs fits the data sufficiently: χ2 = 24,064, df = 13, p = .031, CFI = .964, IFI = .966, TLI/NNFI = .922, NFI = .928 and RMSEA = .070; (see Table A4).

With respect to the type of leadership, we measured the perceived leadership style of upper management. TL was measured using the five-factor model of Rafferty and Griffin (Citation2004) and includes the factors vision, inspirational communication, intellectual stimulation, supportive leadership and personal recognition. The final first-order measurement model of TL sufficiently fits the data: χ2 = 132,262, df = 67, p = .000, CFI = .948, IFI = .950, TLI/NNFI = .919, NFI = .903 and RMSEA = .070; see Table A5. SL was operationalised using the operationalisation of van Dierendonck and Nuijten (Citation2011). The final first-order measurement model including the factors empowerment, humility and standing back fits the data well: χ2 = 115,138, df = 62, p = .000, CFI = .956, IFI = .957, TLI/NNFI = .936, NFI = .912 and RMSEA = .066 (see Table A6). EL was measured using the Empowering Leadership Questionnaire (ELQ) of Arnold et al. (Citation2000) with the factors coaching, informing, leading by example, showing concern/interacting with the team and participative decision-making. The final measurement model of EL fits the data well: χ2 = 125,418, df = 45, p = .000, CFI = .950, IFI = .952, TLI/NNFI = .923, NFI = .912, RMSEA = .075); see Table A7. Finally, we measured the constructs contingent punishment behaviour (Podsakoff, Todor, Grover, & Huber, Citation1984) and trust in/loyalty to the Leader (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Moorman, & Fetter, Citation1990) to test for possible alternative explanations for the variance in the dependent variables (see Tables A8 and A9). Descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s alpha and correlation matrix for all constructs are presented in . Cronbach’s alpha exceeds 0.65 for all constructs, which indicates satisfactory reliability (Cronbach, Citation1951).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix with Cronbach’s alpha on the diagonal.

4.3. Control variables and common method bias

In this research we used respondent’s hierarchical position, education and tenure within the organisation and organisation size as control variables. Size for instance was measured by the number of employees (logarithmised); smaller organisations typically have fewer resources for the implementation of process improvement initiatives or supply chain management practices (Cao & Zhang, Citation2011). However, we found no significant relationship (p < .05) between the control variables and the constructs in the statistical models used. Procedural methods were applied to minimise the potential for common method bias since both the independent and dependent measures were obtained from the same source (Podsakoff & Organ, Citation1986). We ensured our sample included mid- to senior-level managers with significant levels of relevant knowledge, which tends to mitigate single source bias (Mitchell, Citation1985). Common method bias was also reduced by separating the dependent and independent variable items over the length of the survey instrument and by assuring participants that their individual responses would be kept anonymous (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Citation2003). A statistical approach for assessing whether common method bias exists is Harman’s one-factor test (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). All variables were entered into an unrotated exploratory factor analysis to test whether the majority of the variance can be explained by a single factor, but this was not the case. We therefore conclude that the tests of reliability, validity, overall model fit and common method bias provide adequate support of the appropriateness of the constructs.

5. Results

To test the proposed hypotheses, we performed multiple hierarchical regression analyses. First we regressed the control variables, the leadership styles and management behaviour for CI on the aggregate Lean construct. The variance inflation factors (VIFs) for all variables are lower than the rule-of-thumb cut-off criterion of 10 (Craney & Surles, Citation2002) and also the correlations presented in are smaller than the cut-off criterion of 0.90 for collinearity problems. Model 3 in shows the main effects referring to Hypotheses 1–5. This model shows that empowered leadership (EL) is positively related (b = 0.61, p < .1) and SL is negatively related (b = −0.55, p < .1) to Lean. TL has no significant impact on the aggregate variable Lean. LS (b = 0.31, p < .01) and IS (b = 0.33, p < .05) by management are positively related to Lean.

Table 4. Results of hierarchical regression analysis for aggregate Lean construct.

Since LS and IS by management are stronger predictors for Lean than the type of leadership, we also conducted hierarchical regression analyses for the single Lean constructs separately (i.e. CI-culture, Lean practices and use of Lean tools); see model 3 in for the results. The type of leadership (i.e. SL, EL and TL) is not related to CI-culture; only the extent of IS by management is significantly related to CI-culture (b = 0.82, p < .001).

Table 5. Results of hierarchical regression analysis for CI-culture, Lean practices and use of Lean tools.

The leadership styles are not related to the level of Lean practices (see model c in ). However, LS by management is positively related to Lean practices (b = 0.22, p < .05). In contrast, EL (b = 0.92, p < .05) is positively related and SL (b = −0.99, p < .05) is negatively related to the use of Lean tools. LS by management positively impacts the use of Lean tools (b = 0.42, p < .001).

The results from the regression analyses for use of Lean tools give reason to explore the influence of individual leadership characteristics on the use of Lean tools. We therefore regressed the control variables, all individual leadership factors and the variables LS and IS by management on the use of Lean tools (see ).

Table 6. Results of hierarchical regression analysis of Lean tools.

The factors standing back (b = −0.47, p < .01) and humility (b = −0.46, p < .1) of the SL scale, and intellectual stimulation (b = −0.45, p < .1) of the TL scale are negatively related to the use of Lean tools. Informing (b = 0.67, p < .001) and showing concern (b = 0.41, p < .01) of the EL scale are positively related to use of Lean tools. In addition, we find LS by management (b = 0.38, p < .001) and having a CI-culture (b = 0.33, p < .1) to be positively related to the use of Lean tools.

6. Discussion

6.1. Conclusions

Top management sponsorship, demonstrable commitment, active involvement and IS are frequently cited as important leadership behaviours for Lean management (Mann, Citation2009; Worley & Doolen, Citation2006). Indeed, in literature a positive connection is made between Lean leadership and contemporary leadership styles such as TL (Dean & Bowen, Citation1994; McLachlin, Citation1997; Sosik & Dionne, Citation1997) and SL (Poksinska et al., Citation2013) but empirical evidence is often lacking. Based on a sample of 199 respondents, this study shows that LS and IS by higher management is indeed positively related to Lean, though IS is particularly related to the presence of a CI-culture. SL as a leadership style of higher management is negatively related to the use of Lean tools but not related to the level of Lean practices or to the presence of a CI-culture, while EL is positively related to the use of Lean tools. No relations are found between the contemporary leadership styles and Lean practices. This concurs with the findings of Laohavichien et al. (Citation2011) that the interactions of TL style with infrastructure and core practices are not significant. Considering the individual leadership factors we found that three individual factors (i.e. standing back, humility and intellectual stimulation) are negatively related to the use of Lean tools, and two individual factors (i.e. informing and showing concern) are positively related to the use of Lean tools (see ).

Table 7. Direct effects testing results.

6.2. Implications

This research shows that senior management must not hold back from Lean initiatives but actively promote and stimulate the use of Lean tools to continuously improve processes and activities. Top management must continue their efforts promoting the reason and purpose of Lean, explaining the True North of the Lean-organisation and stressing the importance to build and strengthen Lean capabilities and practices as a type of Lean infrastructure. Senior management must also inform staff about the expectations and consequences of implementing Lean and take the time to address any concerns about or resistance to Lean and the inevitable change; it is important that senior management shows concern for similar issues.

This result does not imply that SL and TL are unrelated to Lean leadership as Lean requires different Lean leadership behaviour on different hierarchical levels (Mann, Citation2009). This concurs with Lakshman (Citation2006) that involvement and participation of managers and employees at all levels are important to the successful management of quality in organisations. Lean leadership at the supervisory level and thus leader behaviours of supervisors or lower level managers are probably more people-oriented and others-focused to stimulate participation and teamwork, promote employee responsibility by showing trust in people then senior management. The paradoxical nature of Lean leadership (i.e. technical aspects versus the social, follower-related aspects) will apparently be balanced among various hierarchical levels by means of spatial separation (Poole & Van de Ven, Citation1989).

6.3. Limitations and future research

Like any research, this study also has its limitations. First, we studied Lean leadership behaviour of senior management with the help of data comprising various types of respondents of various organisations. Although the scales in this study are sufficiently reliable, future research could set up an experiment in which the difference is being studied in leadership behaviour between two or more groups of Lean adopters (given various Lean implementation stages) versus a group of non-adopters. This also offers the opportunity to investigate differences in leadership at different hierarchical levels. Second, we do not have all possible factors of SL and EL included in the study. Sendjaya and Cooper (Citation2011), for example, have proposed slightly different factors as a scale for SL than we used in this study. Since there is no ultimate consensus on the appropriate factors to measure each type of leadership, future research could involve alternative factors of servant, transformational and EL.

One of the primary cultural features associated with leadership is power distance (Swierczek, Citation1991). Strong, decisive leaders are expected in high power distance cultures, with less decisive leaders perceived as weak and ineffectual (Blunt, Citation1988). Future research could include such cultural factors as possible mediating factors. In addition, although this study associates the theories of transformational, servant and EL with Lean leadership, this paper did not address the underlying influence processes (Yukl, Citation1989) impacting Lean leadership nor is the relationship of the leader’s behaviour to various stages of Lean implementation examined. Future research could resolve this issue.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Anand, G., Ward, P. T., Tatikonda, M. V., & Schilling, D. A. (2009). Dynamic capabilities through continuous improvement infrastructure. Journal of Operations Management, 27(6), 444–461. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2009.02.002

- Arnold, J. A., Arad, S., Rhoades, J. A., & Drasgow, F. (2000). The empowering leadership questionnaire: The construction and validation of a new scale for measuring leader behaviors. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(3), 249–269.

- Avolio, B. J., Bass, B. M., & Jung, D. I. (1999). Re-examining the components of transformational and transactional leadership using the Multifactor Leadership. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 72(4), 441–462. doi:10.1348/096317999166789

- Azadegan, A., Patel, P. C., Zangoueinezhad, A., & Linderman, K. (2013). The effect of environmental complexity and environmental dynamism on lean practices. Journal of Operations Management, 31(4), 193–212. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2013.03.002

- Barling, J., Weber, T., & Kelloway, E. K. (1996). Effects of transformational leadership training on attitudinal and financial outcomes: A field experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(6), 827–832.

- Bass, B. M. (1991). From transactional to transformational leadership: Learning to share the vision. Organizational Dynamics, 18(3), 19–31.

- Belekoukias, I., Garza-Reyes, J. A., & Kumar, V. (2014). The impact of lean methods and tools on the operational performance of manufacturing organisations. International Journal of Production Research, 52(18), 5346–5366. doi:10.1080/00207543.2014.903348

- Bessant, J., Caffyn, S., & Gallagher, M. (2001). An evolutionary model of continuous improvement behaviour. Technovation, 21(2), 67–77. doi:10.1016/S0166-4972(00)00023-7

- Bessant, J., & Francis, D. (1999). Developing strategic continuous improvement capability. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 19(11), 1106–1119. doi:10.1108/01443579910291032

- Blunt, P. (1988). Cultural consequences for organization change in a Southeast Asian state: Brunei. The Academy of Management Executive, 2(3), 235–240. doi:10.5465/AME.1988.4277262

- Bodek, N. (2008). Leadership is critical to Lean. Manufacturing Engineering, 140(3), 145–154.

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21(2), 230–258. doi:10.1177/0049124192021002005

- Browning, T. R., & Heath, R. D. (2009). Reconceptualizing the effects of lean on production costs with evidence from the F-22 program. Journal of Operations Management, 27(1), 23–44. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2008.03.009

- Cagliano, R., Caniato, F., & Spina, G. (2006). The linkage between supply chain integration and manufacturing improvement programmes. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 26(3), 282–299. doi:10.1108/01443570610646201

- Cao, M., & Zhang, Q. (2011). Supply chain collaboration: Impact on collaborative advantage and firm performance. Journal of Operations Management, 29(3), 163–180. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2010.12.008

- Choi, T. Y., & Eboch, K. (1998). The TQM paradox: Relations among TQM practices, plant performance, and customer satisfaction. Journal of Operations Management, 17(1), 59–75. doi:10.1016/S0272-6963(98)00031-X

- Choi, T. Y., & Liker, J. K. (1995). Bringing Japanese continuous improvement approaches to US manufacturing: The roles of process orientation and communications. Decision Sciences, 26(5), 589–620. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5915.1995.tb01442.x

- Choo, A. S., Linderman, K. W., & Schroeder, R. G. (2007). Method and context perspectives on learning and knowledge creation in quality management. Journal of Operations Management, 25(4), 918–931. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2006.08.002

- Conger, J. A. (1989). Leadership: The art of empowering others. The Academy of Management Executive, 3(1), 17–24.

- Craney, T. A., & Surles, J. G. (2002). Model-dependent variance inflation factor cutoff values. Quality Engineering, 14(3), 391–403. doi:10.1081/QEN-120001878

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334.

- Cua, K. O., McKone, K. E., & Schroeder, R. G. (2001). Relationships between implementation of TQM, JIT, and TPM and manufacturing performance. Journal of Operations Management, 19(6), 675–694. doi:10.1016/S0272-6963(01)00066-3

- Dahlgaard, J. J., Pettersen, J., & Dahlgaard-Park, S. M. (2011). Quality and lean health care: A system for assessing and improving the health of healthcare organisations. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 22(6), 673–689. doi:10.1080/14783363.2011.580651

- Dean, J. W., & Bowen, D. E. (1994). Management theory and total quality: improving research and practice through theory development. Academy of Management Review, 19(3), 392–418.

- van Dierendonck, D. (2011). Servant leadership: A review and synthesis. Journal of Management, 37(4), 1228–1261. doi:10.1177/0149206310380462

- van Dierendonck, D., & Nuijten, I. (2011). The servant leadership survey: Development and validation of a multidimensional measure. Journal of Business and Psychology, 26(3), 249–267. doi:10.1007/s10869-010-9194-1

- Done, A., Voss, C., & Rytter, N. G. (2011). Best practice interventions: Short-term impact and long-term outcomes. Journal of Operations Management, 29(5), 500–513. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2010.11.007

- Douglas, T. J., & Judge, W. Q. (2001). Total quality management implementation and competitive advantage: The role of structural control and exploration. Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), 158–169.

- Flynn, B. B., Sakakibara, S., & Schroeder, R. G. (1995). Relationship between JIT and TQM: Practices and performance. The Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1325–1360. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/256860

- Flynn, B. B., Schroeder, R. G., & Flynn, E. J. (1999). World class manufacturing: an investigation of Hayes and Wheelwright’s foundation. Journal of Operations Management, 17(3), 249–269. doi:10.1016/S0272-6963(98)00050-3

- Flynn, B. B., & Flynn, E. J. (2004). An exploratory study of the nature of cumulative capabilities. Journal of Operations Management, 22(5), 439–457. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2004.03.002

- Ford, R. C., & Fottler, M. D. (1995). Empowerment: A matter of degree. The Academy of Management Executive, 9(3), 21–29.

- GreenLeaf, R. K. (1977). Servant leadership. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press.

- Hirst, G., van Dick, R., & van Knippenberg, D. (2009). A social identity perspective on leadership and employee creativity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(7), 963–982. doi:10.1002/job.600

- Hopp, W. J., & Spearman, M. L. (2004). To pull or not to pull: What is the question? Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 6(2), 133–148. doi:10.1287/msom.1030.0028

- Huang, X., Rode, J. C., & Schroeder, R. G. (2011). Organizational structure and continuous improvement and learning: Moderating effects of cultural endorsement of participative leadership. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(9), 1103–1120. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41309753

- Jones, R., Latham, J., & Betta, M. (2013). Creating the illusion of employee empowerment: Lean production in the international automobile industry. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(8), 1629–1645. doi:10.1080/09585192.2012.725081

- Jung, D. I., Chow, C., & Wu, A. (2003). The role of transformational leadership in enhancing organizational innovation: Hypotheses and some preliminary findings. The Leadership Quarterly, 14(4–5), 525–544. doi:10.1016/S1048-9843(03)00050-X

- Kanning, U. P., & Bergmann, N. (2009). Predictors of customer satisfaction: Testing the classical paradigms. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 19(4), 377–390. doi:10.1108/09604520910971511

- Karlsson, C., & Åhlström, P. (1996). Assessing changes towards lean production. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 16(2), 24–41. doi:10.1108/01443579610109820

- Konczak, L. J., Stelly, D. J., & Trusty, M. L. (2000). Defining and measuring empowering leader behaviors: Development of an upward feedback instrument. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 60(2), 301–313. doi:10.1177/00131640021970420

- Lakshman, C. (2006). A theory of leadership for quality: Lessons from TQM for leadership theory. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 17(1), 41–60. doi:10.1080/14783360500249729

- Lam, M., O’Donnell, M., & Robertson, D. (2015). Achieving employee commitment for continuous improvement initiatives. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 35(2), 201–215. doi:10.1108/IJOPM-03-2013-0134

- Landry, S., & Beaulieu, M. (2010). Achieving lean healthcare by combining the two-bin kanban replenishment system with RFID technology. International Journal of Health Management and Information, 1(1), 85–98.

- Laohavichien, T., Fredendall, L. D., & Cantrell, R. S. (2011). Leadership and quality management practices in Thailand. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 31(10), 1048–1070. doi:10.1108/01443571111172426

- Lewis, M. W., Andriopoulos, C., & Smith, W. K. (2014). Paradoxical leadership to enable strategic. Agility California Management Review, 56(3), 58–77.

- Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Zhao, H., & Henderson, D. (2008). Servant leadership: Development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. The Leadership Quarterly, 19(2), 161–177. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.01.006

- Liker, J. K. (2004). Toyota way: 14 management principles from the World’s greatest manufacturer. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Liker, J. K., & Morgan, J. M. (2006). The Toyota way in services: The case of lean product development. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 20(2), 5–20.

- Lin, S. P., Yang, C. L., Chan, Y. H., & Sheu, C. (2010). Refining Kano’s ‘quality attributes–satisfaction’ model: A moderated regression approach. International Journal of Production Economics, 126(2), 255–263.

- Linderman, K., Schroeder, R. G., & Choo, A. S. (2006). Six Sigma: The role of goals in improvement teams. Journal of Operations Management, 24(6), 779–790. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2005.08.005

- Linderman, K., Schroeder, R. G., Zaheer, S., & Choo, A. S. (2003). Six Sigma: A goal-theoretic perspective. Journal of Operations Management, 21(2), 193–203. doi:10.1016/S0272-6963(02)00087-6

- MacDuffie, J. P. (1997). The road to “root cause”: Shop-floor problem-solving at three auto assembly plants. Management Science, 43(4), 479–502.

- Mann, D. (2009). The missing link: Lean leadership. Frontiers of Health Services Management, 26(1), 15–26.

- McLachlin, R. (1997). Management initiatives and just-in-time manufacturing. Journal of Operations Management, 15(4), 271–292. doi:10.1016/S0272-6963(97)00010-7

- Mentzer, J. T., & Flint, D. J. (1997). Validity in logistics research. Journal of Business Logistics, 18(1), 199–216.

- Mitchell, T. R. (1985). An evaluation of the validity of correlational research conducted in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 10(2), 192–205.

- Narasimhan, R., Swink, M., & Kim, S. W. (2006). Disentangling leanness and agility: An empirical investigation. Journal of Operations Management, 24(5), 440–457. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2005.11.011

- Netland, T. H., Schloetzer, J. D., & Ferdows, K. (2015). Implementing corporate lean programs: The effect of management control practices. Journal of Operations Management, 36, 90–102. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2015.03.005

- Noone, B. M., Namasivayam, K., & Spitler Tomlinson, H. (2010). Examining the application of Six Sigma in the service exchange. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 20(3), 273–293. doi:10.1108/09604521011041989

- Oliver, N., Delbridge, R., Jones, D., & Lowe, J. (1994). World class manufacturing: Further evidence in the lean production debate. British Journal of Management, 5(s1), S53–S63. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8551.1994.tb00130.x

- Pearce, C. L., & Sims Jr, H. P. (2002). Vertical versus shared leadership as predictors of the effectiveness of change management teams: An examination of aversive, directive, transactional, transformational, and empowering leader behaviors. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 6(2), 172–197.

- Peng, D. X., Schroeder, R. G., & Shah, R. (2008). Linking routines to operations capabilities: A new perspective. Journal of Operations Management, 26(6), 730–748. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2007.11.001

- Peterson, S. J., Galvin, B. M., & Lange, D. (2012). CEO servant leadership: Exploring executive characteristics and firm performance. Personnel Psychology, 65(3), 565–596.

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Moorman, R. H., & Fetter, R. (1990). Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 1(2), 107–142.

- Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531–544. doi:10.1177/014920638601200408

- Podsakoff, P. M., Todor, W. D., Grover, R. A., & Huber, V. L. (1984). Situational moderators of leader reward and punishment behaviors: Fact or fiction? Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 34(1), 21–63.

- Poksinska, B., Swartling, D., & Drotz, E. (2013). The daily work of Lean leaders – Lessons from manufacturing and healthcare. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 24(7–8), 886–898. doi:10.1080/14783363.2013.791098

- Poole, M. S., & Van de Ven, A. H. (1989). Using paradox to build management and organization theories. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 562–578.

- Rafferty, A. E., & Griffin, M. A. (2004). Dimensions of transformational leadership: Conceptual and empirical extensions. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(3), 329–354. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2004.02.009

- Rivera, L., & Chen, F. F. (2007). Measuring the impact of lean tools on the cost–time investment of a product using cost–time profiles. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing, 23(6), 684–689. doi:10.1016/j.rcim.2007.02.013

- Sakakibara, S., Flynn, B. B., & Schroeder, R. G. (1993). A framework and measurement instrument for just-in-time manufacturing. Production and Operations Management, 2(3), 177–194. doi:10.1111/j.1937-5956.1993.tb00097.x

- Sakakibara, S., Flynn, B. B., Schroeder, R. G., & Morris, W. T. (1997). The impact of Just-in-time manufacturing and its infrastructure on manufacturing performance. Management Science, 43(9), 1246–1257. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2634636

- Schaubroeck, J., Lam, S. S., & Peng, A. C. (2011). Cognition-based and affect-based trust as mediators of leader behavior influences on team performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(4), 863–871.

- Schonberger, R. J. (2007). Japanese production management: An evolution—with mixed success. Journal of Operations Management, 25(2), 403–419. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2006.04.003

- Sendjaya, S., & Cooper, B. (2011). Servant leadership behaviour scale: A hierarchical model and test of construct validity. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 20(3), 416–436. doi:10.1080/13594321003590549

- Shah, R., & Ward, P. T. (2003). Lean manufacturing: Context, practice bundles, and performance. Journal of Operations Management, 21(2), 129–149. doi:10.1016/S0272-6963(02)00108-0

- Shah, R., & Ward, P. T. (2007). Defining and developing measures of lean production. Journal of Operations Management, 25(4), 785–805. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2007.01.019

- Shamir, B., House, R. J., & Arthur, M. B. (1993). The motivational effects of charismatic leadership: A self-concept based theory. Organization Science, 4(4), 577–594.

- Sitkin, S. B., Sutcliffe, K. M., & Schroeder, R. G. (1994). Distinguishing control from learning in total quality management: A contingency perspective. The Academy of Management Review, 19(3), 537–564. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/258938

- Sosik, J., & Dionne, S. (1997). Leadership styles and Deming’s behavior factors. Journal of Business and Psychology, 11(4), 447–462. doi:10.1007/BF02195891

- Spear, S. J., & Bowen, H. K. (1999). Decoding the DNA of the Toyota production system. Harvard Business Review, 77(5), 96–108.

- Stone, A. G., Russell, R. F., & Patterson, K. (2004). Transformational versus servant leadership: A difference in leader focus. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 25(4), 349–361. doi:10.1108/01437730410538671

- Swierczek, F. W. (1991). Leadership and culture: Comparing Asian managers. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 12(7), 3–10.

- de Treville, S., & Antonakis, J. (2006). Could lean production job design be intrinsically motivating? Contextual, configurational, and levels-of-analysis issues. Journal of Operations Management, 24(2), 99–123. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2005.04.001

- Tyagi, S., Choudhary, A., Cai, X., & Yang, K. (2015). Value stream mapping to reduce the lead-time of a product development process. International Journal of Production Economics, 160, 202–212. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2014.11.002

- Vidal, M. (2007). Lean production, worker empowerment, and job satisfaction: A qualitative analysis and critique. Critical Sociology, 33(1–2), 247–278.

- Waldman, D. A. (1993). A theoretical consideration of leadership and total quality management. The Leadership Quarterly, 4(1), 65–79. doi:10.1016/1048-9843(93)90004-D

- Ward, A., Liker, J. K., Cristiano, J. J., & Sobek, D. K., II. (1995). The second Toyota paradox: How delaying decisions can make better cars faster. Sloan management review, 36(3), 43–61.

- Wellins, R. S., Byham, W. C., & Wilson, J. M. (1991). Empowered teams. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Womack, J. P., & Jones, D. T. (1996). Lean thinking: Banish waste and create wealth in your corporation. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Womack, J. P., Jones, D. T., & Roos, D. (1990). Machine that changed the world. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Worley, J. M., & Doolen, T. L. (2006). The role of communication and management support in a lean manufacturing implementation null. Management Decision, 44(2), 228–245. doi:10.1108/00251740610650210

- Wu, C. W., & Chen, C. L. (2006). An integrated structural model toward successful continuous improvement activity. Technovation, 26(5–6), 697–707. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2005.05.002

- Yoshida, D. T., Sendjaya, S., Hirst, G., & Cooper, B. (2014). Does servant leadership foster creativity and innovation? A multi-level mediation study of identification and prototypicality. Journal of Business Research, 67(7), 1395–1404. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.08.013

- Yukl, G. (1989). Managerial leadership: A review of theory and research. Journal of Management, 15(2), 251–289.

- Zu, X., Robbins, T. L., & Fredendall, L. D. (2010). Mapping the critical links between organizational culture and TQM/Six Sigma practices. International Journal of Production Economics, 123(1), 86–106. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2009.07.009

Appendix 1. Survey items and sources, reliability results and item statistics

A1. Lean practices – adapted from Shah and Ward (Citation2007)

Setup reduction (SR)

Range: strongly disagree – strongly agree (5-point Likert scale)

In this business unit (location, department) …

SR1 employees are trained to reduce setup time.

SR2 we have a structured method to reduce setup time.

SR3 we continuously try to reduce setup time.

Visual management (VM)

Range: strongly disagree – strongly agree (5-point Likert scale)

In this business unit (location, department) …

VM1 signs, symbols and lines are used to indicate how processes run, where material deliveries take place, what the walking paths are and where stock locations are.

VM2 a visual control system is present at the workplace that provides information about the production, quality and / or backlog.

VM3 information screens (that can been seen by everyone) are present that show performances (daily or weekly performance).

VM4 up-to-date work instructions are present in any workplace and visualised by using characters (symbols), photos and procedures – not included in the final scale because of low factor loading.

Pull

Range: strongly disagree – strongly agree (5-point Likert scale)

In this business unit (location, department) …

PC1 we have a method to keep the work in progress in the primary processes low and evenly (so that work flow and peaks are avoided) – not included in the final scale because of low factor loading.

PC2 we work with pull-control, in which production is initiated from a real customer order.

PC3 we use a pull-control system.

PC4 work at a particular machine/workstation is triggered by a pull-signal from a subsequent machine/workstation.

Good housekeeping (GH)

Range: strongly disagree – strongly agree (5-point Likert scale)

In this business unit (location, department) …

GH1 all employees are familiar with the 5S method.

GH2 for every workstation/workplace it is made clear what resources and tools are needed and what is actually ‘unnecessary’ to have present at the workplace – not included in the final scale because of low factor loading.

GH3 everyone in the organization knows why 5S has been introduced and applied.

GH4 all ‘unnecessary’ items removed (such as unused tools, rejected materials or scrap, personal materials, outdated information) – not included in the final scale because of low factor loading.

Flow

Range: strongly disagree – strongly agree (5-point Likert scale)

In this business unit (location, department) …

Flow1 resources and/or workstations are grouped in such a way that each product family can be produced in a continuous flow – not included in the final scale because of low factor loading.

Flow2 products and/or services are grouped by routing and/or similar process steps.

Flow3 products and/or services are grouped according similar activities and actions to produce the products and/or services.

Table A1. Reliability and item statistics for second order measurement model of Lean practices (χ2 = 95,715, df = 60, p = .002, CFI = .962, IFI = .963, TLI/NNFI = .994, NFI = .908, RMSEA = .055).

A2. Use of Lean tools

Range: 5-point Likert scale and the answering option ‘Do not know’: 1 – No, not at all, 2 – Yes, but only rarely, 3 – Yes, occasionally, 4 – Yes, on a regular basis, 5 – Yes, extensively

In this business unit (location, department) we make use of …

Visual management tools

VMT1 glass walls and/or white boards with performance indicators.

VMT2 value stream maps on the shop floor and/or within the office.

VMT3 visual quality control charts – not included in the final scale because of low factor loading.

Pull-control tools

PCT1 kanban cards (system).

PCT2 two-bin cards (system).

PCT3 takt times.

Kaizen improvement tools

KIT1 PDCA improvement cycle

KIT2 large kaizen events (kaizen improvement sessions that take longer than 1 day).

KIT3 small kaizen bubbles (improvement sessions that take no longer than 1 day).

Root-cause analysis tools

RCT1 Fish-bone diagram (cause-and-effect diagrams).

RCT2 5Why’s method.

Table A2. Reliability and item statistics for second order measurement model of use of Lean tools (χ2 = 32.682, df = 31, p = .384, CFI = .997, IFI = .997, TLI/NNFI = .994, NFI = .943, RMSEA = .017).

CI-culture – adapted from Huang et al. (Citation2011)

Range: strongly disagree – strongly agree (5-point Likert scale)

CI1 Management is actively engaged in CI.

CI2 There is a culture of CI.

CI3 CI is an important value that characterises our culture.

Table A3. Reliability and item statistics CI-culture.

A3. LS and IS by upper management

LS – adapted from Flynn et al. (Citation1999) and Douglas and Judge (Citation2001).

Range: strongly disagree – strongly agree (5-point Likert scale)

LS1 Upper management is a true ambassador of Operational Excellence/Lean management.

LS2 Upper management shows championship to implement Operational Excellence/Lean management.

LS3 Upper management advocates the use of the principles of Lean management.

IS – adapted from Flynn et al. (Citation1999)

Range: strongly disagree – strongly agree (5-point Likert scale)

IS1 We receive timely feedback from management as we put forward ideas for improvement.

IS2 Bringing forward suggestions for improvement is actively encouraged by management.

IS3 Direct staff is actively involved in minor improvements.

IS4 Higher management actively encourages employees to continuously improve their work.

IS5 Direct staff is actively involved in major improvement projects (consisting of several improvement workshops).

Table A4. Reliability and item statistics for first-order measurement model of LS and IS by upper management (χ2 = 24,064, df = 13, p = .031, CFI = .964, IFI = .966, TLI/NNFI = .922, NFI = .928, RMSEA = .070).

A4. Transformational leadership (TL) – Rafferty and Griffin (Citation2004)

TL: Vision

Range: strongly disagree – strongly agree (5-point Likert scale)

TLV1 Upper management has a long-term vision.

TLV2 Upper management has a clear sense of where he/she wants our organization to be in 5 years.

TLV3 Upper management has a clear understanding of where we are going with our organization.

TLV4 Upper management has no idea where the organization is going (R) – not included in the final scale because of low factor loading.

TL: Inspiring communication

Range: strongly disagree – strongly agree (5-point Likert scale)

TLIC1 Upper management says things that make employees proud to be a part of this organization.

TLIC2 Upper management encourages people to see changing environments as situations full of opportunities.

TL: Intellectual stimulation

Range: strongly disagree – strongly agree (5-point Likert scale)

TLIS1 Upper management has challenged me to rethink some of my basic assumptions about my work.

TLIS2 Upper management has ideas that have forced me to rethink some things that I have never questioned before.

TLIS3 Upper management challenges me to think about old problems in new ways.

TL: Supportive leadership

Range: strongly disagree – strongly agree (5-point Likert scale)

TLS1 Upper management behaves in a manner which is considerate of my personal needs.

TLS2 Upper management sees that the interests of employees are given due consideration.

TLS3 Upper management considers my personal feelings before acting.

TL: Personal recognition

Range: strongly disagree – strongly agree (5-point Likert scale)

TLP1 Upper management commends me when I do a better than average job.

TLP2 Upper management personally compliments me when I do outstanding work.

TLP3 Upper management acknowledges improvement in my quality of work.

Table A5. Reliability and item statistics for first-order measurement model of TL (χ2 = 132.262, df = 67, p = .000, CFI = .948, IFI = .950, TLI/NNFI = .919, NFI = .903, RMSEA = .070).

A5. Servant leadership (SL) – van Dierendonck and Nuijten (Citation2011)

SL: Empowerment

Range: strongly disagree – strongly agree (5-point Likert scale)

SLE1 Upper management gives us the information to do our work well.

SLE2 Upper management gives us the authority to take decisions which make work easier.

SLE3 Upper management encourages us to use our talents.

SLE4 Upper management helps me to further develop myself.

SLE5 Upper management enables us to solve problems instead of just telling us what to do – not included in the final scale because of low factor loading.

SLE6 Upper management offers abundant opportunities to learn new skills.

SL: Humility

Range: strongly disagree – strongly agree (5-point Likert scale)

SLH1 Upper management learns from the different views and opinions of others.

SLH2 Upper management learns from criticism.

SLH3 Upper management is open about their limitations and weaknesses.

SLH4 If people express criticism, upper management tries to learn from it.

SLH5 Upper management is prepared to express their feelings.

SLH6 Upper management admits mistakes.

SL: Standing back

Range: strongly disagree – strongly agree (5-point Likert scale)

SLS1 Upper management appears to enjoy subordinate’s success more than their own success.

SLS2 Upper management stays in the background and gives credits to others.

Table A6. Reliability and item statistics for first-order measurement model of SL (χ2 = 115.138, df = 62, p = .000, CFI = .956, IFI = .957, TLI/NNFI = .936, NFI = .912, RMSEA = .066).

A6. Empowering leadership (EL) – Arnold et al. (Citation2000)

EL: Informing

Range: strongly disagree – strongly agree (5-point Likert scale)

ELI1 Upper management clearly explains company decisions.

ELI2 Upper management clearly explains company goals.

ELI3 Upper management explains rules and expectations.

ELI4 Upper management explains decisions and actions.

EL: Leading by example

Range: strongly disagree – strongly agree (5-point Likert scale)

ELL1 Upper management sets a good example how to behave.

ELL2 Upper management leads by example.

EL: Participative decision-making

Range: strongly disagree – strongly agree (5-point Likert scale)

ELP1 Upper management encourages employees to express ideas/suggestions.

ELP2 Upper management listens to ideas and suggestions from subordinates.

ELP3 Upper management gives all employees a chance to voice their opinions.

ELP4 Upper management considers ideas from employees even when they disagree.

EL: Showing concern/interacting with the team

Range: strongly disagree – strongly agree (5-point Likert scale)

ELS1 Upper management takes the time to discuss subordinate’s concerns patiently.

ELS2 Upper management stays in touch and gets along with all his/her subordinates.

ELS3 Upper management finds time to chat with employees.

Table A7. Reliability and item statistics for first-order measurement model of SL (χ2 = 125.418, df = 45, p = .000, CFI = .950, IFI = .952, TLI/NNFI = .923, NFI = .912, RMSEA = .075).

A7. Contingent punishment behavior – Podsakoff et al. (Citation1984)

Range: strongly disagree – strongly agree (5-point Likert scale)

CPB1 Upper management shows displeasure when work is below acceptable standards.

CPB2 Upper management lets us quickly know when performance is poorly.

CPB3 Upper management would reprimand subordinates if the work was below standard.

CPB4 When my work is not up to par, my manager points it out to me.

Table A8. Reliability and item statistics for first-order measurement model of contingent punishment behavior (χ2 = 8.431, df = 2, p = .015, CFI = .982, IFI = .982, TLI/NNFI = .908, NFI = .977, RMSEA = .127).

A8. Trust in/loyalty to the leader – Podsakoff et al. (Citation1990)

Range: strongly disagree – strongly agree (5-point Likert scale)

TLL1 I feel quite confident that upper management will always try to treat me fairly.

TLL2 I have complete faith in the integrity of upper management.

TLL3 I have a clear sense of loyalty toward upper management.

TLL4 I would support upper management in almost any situation – not included in the final scale because of low factor loading.