Abstract

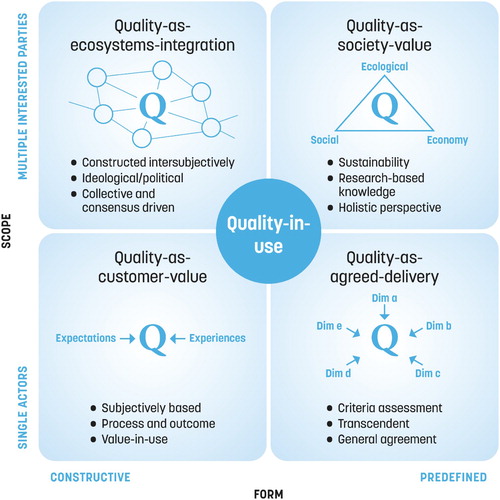

The concept of quality accommodates a range of perspectives. Over the years, various conceptual definitions of quality have reflected the evolution and trends marking the history and development of quality management. The current and widely accepted understanding of the concept of quality focuses on customer-centric notions, where meeting or preferably exceeding customer needs and expectations defines quality. However, societal drivers such as sustainability and digitalisation require a perspective on quality that is inclusive of a broader range of stakeholders to serve current and future societal needs. The purpose of this paper is to elaborate on the concept of quality as practiced and extend this understanding in a framework designed to include objective and subjective aspects from a broad range of stakeholders. An integrated conceptual framework offering expanded views on the foundations for defining the meaning of quality is suggested. This framework is centred around the notion of quality-in-use, which offers a way to guide and enhance the actual practices of Quality Management. It incorporates two dimensions for understanding quality; form, which covers the constructive or predefined dimension and scope, which covers the single actor or multi-interested parties dimension. Four major perspectives on quality-in-use are presented: Quality-as-customer-value, Quality-as-agreed-delivery, Quality-as-ecosystems-integration, and Quality-as-society-values.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Quality is a multi-faceted and intangible construct (Charantimath, Citation2011; Zhang, Citation2001) that has been subject to many interpretations and perspectives in our everyday life, in academia, as well as in industry and the public domain. In industry, most organisations have well-established quality departments (Sousa & Voss, Citation2002), but the method of organising quality work for best results is still being questioned. These questions are about the need for a separate quality profession (Waddell & Mallen, Citation2001), the quality practices that best influence business results (Gremyr et al., Citation2019), and competencies that the quality practitioners need to have (Martin et al., Citation2019; Ponsignon et al., Citation2019). All of these questions relate to the definition of quality and its meaning.

This paper addresses the different meanings of quality in Quality Management and the evolution of meanings over time. Quality Management has its roots in the manufacturing industry that has changed significantly in the last century, especially regarding the role of the customer. Moreover, new concepts and approaches related to Quality Management have been proposed over the years. They have impacted the notion of quality regarding the dominant principles and practices. It is also evident that society, in which organisations exist, changes, and poses demands such as sustainability and digitalisation. This influences the operationalisation of quality.

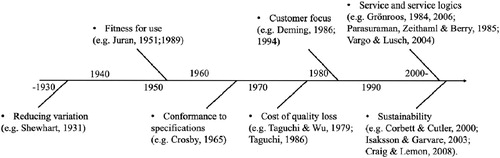

Different meanings have been assigned to the concept of quality over time, e.g. in the views of the customers (Lengnick-Hall, Citation1996). During the pioneering days of Quality Management, conformance and the significance of reducing variation in manufacturing processes were key features when defining quality (e.g. Shewhart, Citation1931; Wadsworth et al., Citation2001). However, Shewhart (Citation1931) noted the subjective side of quality, and Juran and Godfrey (Citation1998; Juran, Citation1989) emphasised this with a customer-oriented definition of quality as ‘fitness for use’ (Citation1998, p. 4.20). This approach was further elaborated by Deming (Citation1986) explicitly addressing the customer when defining that ‘quality should be aimed at the needs of the customer, present and future’ (p.5). Deming (e.g. Citation1986) and Juran (e.g. Juran & Godfrey, Citation1998) thus pioneered a perspective of quality as being required by customers, which was extended later to the idea of service quality (Grönroos, Citation1984). More recent research on Quality Management, incorporating sustainability perspectives, highlights a need for a broader understanding of customer roles, also considering other stakeholder perspectives (e.g. Corbett & Cutler, Citation2000; Craig & Lemon, Citation2008; Isaksson & Garvare, Citation2003).

A variety of approaches to Quality Management have been developed in practice and academia, which in turn have influenced the meanings and practices of quality. Examples of approaches that have influenced the area of Quality Management are Six Sigma and Lean, both with roots in industrial practices (Dahlgaard Park & Dahlgaard, Citation2006). An example of the differences between the two approaches is; Six Sigma mainly focuses on project-based, radical improvements, whereas Lean mainly focuses on process-based, continuous improvements (Assarlind et al., Citation2013). This has consequences for how quality is perceived. Six Sigma is defined as ‘an organised, parallel-meso structure to reduce variation in organisational processes by using improvement specialists, a structured method, and performance metrics to achieve strategic objectives’ (Schroeder et al., Citation2008, p. 540). Emphasis is on the improvement specialists that works in a specific project structure with a specific method evaluated by measurable results. Lean, however, focuses on process and flow efficiency, the latter being the percentage of the total lead time in production that is used for value-adding activities (Modig & Åhlström, Citation2012). Focusing on the processes leads to an emphasis on the involvement of the employees directly working in the process (Marin-Garcia & Bonavia, Citation2015) rather than on a separate organisation of improvement specialists (Schroeder et al., Citation2008).

Moving to the influence from society, the meaning of quality and the focus of Quality Management is affected as the organisations’ priorities are altered e.g. by sustainability concerns and digitalisation efforts. First, as to the influence of sustainability, Taguchi and Wu (Citation1979) highlighted that considerations of quality should include not only the function of the product but also possible negative effects on society. A key challenge for sustainability efforts in organisations is to make sustainability considerations a natural part of daily work (Luttropp & Lagerstedt, Citation2006; Maxwell & Van der Vorst, Citation2003). Here, Quality Management has been identified as a suitable infrastructure for the integration of sustainability considerations. Examples of ways suggested to integrate sustainability in quality work are the use of methods such as Quality Function Deployment (Sakao, Citation2004) and Robust Design Methodology (Gremyr et al., Citation2014), or the use of integrated management systems (Siva et al., Citation2016). Besides academia, national organisations such as the Swedish Institute for Quality have also suggested integrated approaches such as Quality 5.0 (SIQ, Citation2020) emphasising the inclusion of a broader range of stakeholders than the customer in shaping the meaning of quality. Second, digitalisation has influenced society and organisations on all levels, from generating new types of jobs to allowing for digital tools as support in day-to-day activities (Parviainen et al., Citation2017). Examples of the influences of digitalisation include access to big data in analysis and improvement activities (Gölzer & Fritzsche, Citation2017), new competencies needed to establish close collaborations with IT function (Ponsignon et al., Citation2019), and new types of feedback channels from customers (Birch-Jensen et al., Citation2020). There have also been new approaches established concerning digitalisation, such as Quality 4.0 (Küpper et al., Citation2019; Sony et al., Citation2020).

In response to the many changes and influences on Quality Management outlined above, a need for more contextualised (Sousa & Voss, Citation2002) and emergent views (Anttila & Jussila, Citation2017; Backström, Citation2017; Fundin et al., Citation2017) on quality have been argued. The purpose of this paper is therefore to elaborate on the concept of quality as practiced and extend this understanding in a framework designed to include objective and subjective aspects from a broad range of stakeholders. By developing a heuristic framework that can be further explored in empirical studies, this paper aims for a conceptual contribution in terms of detailing and describing as well as relating (MacInnis, Citation2011) the different meanings of quality to other core concepts.. A short revisit of key research on the concept of quality is presented in a classical overview after this introduction. A conceptual framework of multiple perspectives on quality is then presented from the overview, before concluding the paper with a discussion and conclusions.

2. The many meanings of quality, a historical overview

Walter A. Shewhart (Citation1931), focused on the manufacturing firm’s perspective and identified process variability and the significance of reducing variation as key features of quality (Wadsworth et al., Citation2001). Crosby (Citation1965) adopted a production-oriented view by defining quality as conformance to specifications, i.e. the specified targets and tolerances determined by the product designers (e.g. ‘Zero defects’). Within the production-oriented view, the dominating perspective in Quality Management has been customer focus (e.g. Deming, Citation1986, Citation1994; Garvin, Citation1988; Juran, Citation1989; Juran & Godfrey, Citation1998). Customer focus and customer orientation are key constructs in various attempts at conceptualising Quality Management (e.g. Dean & Bowen, Citation1994; Evans & Lindsay, Citation2011; Prajogo & McDermott, Citation2005; Sousa & Voss, Citation2001, Citation2002). During the last decade, the goods-dominating perspective of customer-focused production has also been complemented by research on service production and service logic. Research on service quality has been established since early 1980, introducing service-oriented dimensions of quality (e.g. Parasuraman et al., Citation1985), thus complementing the dimensions set up for manufactured goods (e.g. Garvin, Citation1984).

A notable contribution targeting service quality and its definition within service research was made by Grönroos (Citation1984). He described quality as having both technical and functional dimensions. Technical quality refers to the tangible aspects, what the customer receives. In contrast, functional quality refers to the intangible aspects or how the customer experiences a product (goods and or services). Technical quality can thus be described objectively, while functional quality is purely subjective (Grönroos, Citation1984). Furthermore, service researchers also emphasised customers as co-creators of customer value (e.g. Vargo & Lusch, Citation2004, Citation2015, Citation2016), or even as the sole creators of value (e.g. Grönroos, Citation2006, Citation2008, Citation2011).

Taguchi and Wu (Citation1979) and Taguchi (Citation1986) were early in elevating a societal macro-perspective on quality when defining quality loss as ‘the loss a product causes to society after being shipped, other than any losses caused by its intrinsic functions’ (p.1). This describes a notion of quality as resulting in consequences and, thus, as evidenced. In the 1990s, the consequences of climate change and environmental issues were also impacting the field of Quality Management. In this sense, quality can also be described as being evidenced. Environmental aspects linked to quality (e.g. Borri & Boccaletti, Citation1995) and sustainability (both environmental, financial, and social) have evolved into essential features in quality research (e.g. Corbett & Cutler, Citation2000; Craig & Lemon, Citation2008; Isaksson & Garvare, Citation2003). Recently, sustainability has often been integrated in quality management systems such as ISO 9001 (ISO, Citation2015) and in business excellence models (e.g. American Society for Quality [ASQ], Citation2015; The Swedish Institute for Quality [SIQ], Citation2018) .

3. Towards an updated framework for the many meanings of quality

3.1. Objective and subjective dimensions of quality

Shewhart (Citation1931) is recognised as being the first to describe both subjective and objective aspects of quality. However, similar notions are echoed by Garvin (Citation1984) and Juran (Citation1989). In Garvin’s (Citation1984) elaboration on ‘product quality’, he proposes five approaches to defining the multi-dimensional construct of quality. Following Garvin’s (Citation1984) definitions, it is possible to discriminate two different and dominating assessment perspectives; quality defined as being guided by a primary subjective or objective assessment. In this paper, it is argued that discerning between objective and subjective perspectives on quality offers a constructive approach towards the understanding of the meaning of quality.

Objective assessments can be described as context-independent and transcendent, i.e. as an absolute and universally recognisable ‘image variable’ (Zhang, Citation2001) independent of any context. For example, certain brands (e.g. Rolls-Royce cars, Patek Philippe wristwatches, and Martin guitars) and certain artists or art (e.g. Picasso, Shakespeare, and Bach) represent images of timeless and superior quality. Within Quality Management, proponents of the objective view of quality include theorists who describe such context-independent and transcendent variables for defining quality (e.g. Garvin, Citation1984, Citation1988). The theorists who adopt a more product-based view (e.g. Taguchi, Citation1986), where the design (often experimentally developed) of the product is primarily guided by an effort to maximise the inherent quality of the particular product.

Subjective quality, however, can be described as context-dependent and reliant on particular and varied needs, desires, and perceptions on usefulness. Within Quality Management, a customer dependent perspective can be argued to have adhered to the subjective dimension (e.g. Crosby, Citation1965; Deming, Citation1986; Juran & Godfrey, Citation1998) where product specifications are meaningless unless they emanate from the needs or requirements of customers. The advent of a service logic approach, focusing on customer or user co-creation, has embraced the customer view, also lending service quality to the subjective dimension of quality (e.g. Grönroos, Citation2006; Parasuraman et al., Citation1985; Vargo & Lusch, Citation2015). outlines differences of subjective and objective assessment between the approaches proposed by Garvin (Citation1984) together with literature examples.

Table 1. Objective and subjective assessments on quality with literature examples.

3.2. Parties of interest: stakeholders, arbiters, and beneficiaries of quality?

Lengnick-Hall (Citation1996) emphasised that customer roles are diverse. This study attempts to extend her input-focused and output-focused view on customer roles by incorporating an extended stakeholder perspective in Quality Management (e.g. Bergquist et al., Citation2006; Foley, Citation2005; Foster & Jonker, Citation2003; Radder, Citation1998). The traditional view on the customer as the primary beneficiary and ultimate arbiter of quality (Lengnick-Hall, Citation1996) is thus challenged. New meanings of quality necessitate a broader and more nuanced view on what constitutes value and benefits for customers and or other stakeholders. A proposed method to extend the traditional customer-focused view is to discern between direct and indirect beneficiaries of quality by determining the meaning of quality using the micro – (or individual parties) and macro-level (or collective parties) stakeholder concepts (see ). Micro-level conceptions of quality include both subjective, context-dependent (e.g. Deming, Citation1986; Grönroos, Citation1984, Citation2006, Citation2008, Citation2011; Juran & Godfrey, Citation1998; Citation1989) as well as objective, context-independent approaches to quality (e.g. Garvin, Citation1984).

Table 2. Quality parties of interest, individual and collective scopes.

Regarding macro-level or collective conceptions of quality, it can be argued that manufacturing-based and production-based views (e.g. Crosby, Citation1965; Taguchi, Citation1986) emphasise wider groups of customers and stakeholders. In the case of Crosby (Citation1965), his ‘cost of quality’ approach expresses a collective rather than individual notion of customers and their requirements. Taguchi (Citation1986), and the proponents of sustainability as a component of Quality Management (e.g. Corbett & Cutler, Citation2000; Craig & Lemon, Citation2008; Isaksson & Garvare, Citation2003) elevate quality concerns even further to the societal level.

3.3. A proposed analytical framework for understanding quality

Based on the previous overview and outline of subjective and objective dimensions as well as individual and collective dimensions, this paper proposes a framework to be utilised in understanding the many faces of quality. The proposed framework incorporates two dimensions for understanding principle meanings of quality; the subjective and the objective assessment dimension and the individual and or societal (multi-actor) dimension.

The concept of quality has over time been defined in many ways. Lately, the dominant view of quality as a subjective experience emanating from the customer has been exposed to critique and challenged by stakeholder and society perspectives. Inherent in this type of critique is that something valuable for a single customer may be very critical and detrimental for society. Likewise, many services in the public domain need to consider quality from many different stakeholders, for instance, in the case of criminal justice, where the criminals and victims have presumably very different views. Another dilemma is the distinction between quality inherent and or predefined in relation to a customer’s subjective views. For instance, a cheap wristwatch may be perceived to have better quality than a Swiss-made watch if a customer judges quality mainly based on price. The basis for this logic is that the customer is the sole judge of quality, and nothing else matters. Consistent with these dilemmas in understanding the meanings of quality, we support the following ideas:

The most useful definition of quality is dependent on the context. Different contexts may yield very different meanings of quality, for instance, private goods manufacturing companies, private service organisations, healthcare, and public services are contexts with potentially different views on what quality is.

Definitions of quality often encourage the use of one perspective. Consequently, there is a risk of compartmentalisation of perspectives that do not enrich each other, and finally, a risk for not fully understanding what it means to work with quality in practice.

We address the shortcomings of current notions of quality by suggesting a broader, holistic perspective. Using the aspects mentioned above as a departure for further analysis, we separate the concept of quality into two dimensions.

Scope: Separating between focus on a single actor or multiple interested parties, i.e. between an individual and collective customer and/or relevant stakeholder views on quality. The definition of quality operates at many levels, including the individual, the organisation, stakeholders, and society at large. Our classification highlights distinctions between (a) the relational aspects of the product and or customer, and (b) the relations and interactions among several actors that may have a stake in the product.

Form: Distinguishing between constructive views and views based on predefined criteria. The definition of quality can be separated regarding either an objective view linked to predefined criteria for quality, or a subjective view constructed by the involved actors, for instance, the individual customer who is experiencing the product.

The two dimensions generate four different forms of quality showed in .

3.3.1. Quality-as-customer-value

Many practitioners and scholars have adopted the view of quality as a function of the subjective experience from the customer’s expectations and experiences of using the product. This perspective highlights that quality is based on the following aspects:

Subjectively based on the experiences of customers and end-users of a product

Process and outcome, i.e. both functional and technical qualities of the product

Value-in-use, i.e. that value determined in use.

Examples of quality-as-customer-value include goods and services with a high level of variation in individual customer needs and perceptions of value. An example illustrating the meaning of such quality could be everyday consumer goods such as mobile phones. From a customer perspective, the quality of a mobile phone, such as the design and usability, is to a high extent, subjectively defined from the perceived value the customer experiences in using the mobile phone. The level of quality is therefore, to a high degree, subjectively defined by how well the individual customer expectations are matched.

3.3.2. Quality-as-agreed-delivery

The quality of a product may, from the aspect of quality-as-agreed-delivery, be determined based either on various standards from production or on end customer requirements. Quality-as-agreed-delivery is formed by several different dimensions and aspects that, a priori, characterises the product and are recognised by the actors depending on the quality. By contrast to a more constructive view on what forms quality, agreed-delivery is based on predefined quality criteria that, in advance, seeks to establish if a product is of adequate quality or not. Important aspects are:

Criteria assessment to ensure compliance to agreements

Transcendent, i.e. representing absolute and ‘innate excellence’ (Garvin, Citation1984) quality dimensions.

General agreement of what represents good quality based on requirements and expected performance that are universally recognised and established.

Examples of quality-as-agreed-delivery often relate to goods or services adhering to common and established quality standards. Examples illustrating the meaning of such quality may include high grade steel products in engineering or construction business where components must adhere to specific quality criteria in order to comply to e.g. safety regulations. Everyday examples of quality-as-agreed-delivery could include food products (e.g. freshness of meat, vegetables and dairy products) or public sector services for citizens (e.g. quality regulations in the provision of health and social services) or the established understandings that jewellery in 18 carat gold is considered to be of higher quality than 10 carat gold.

3.3.3. Quality-as-ecosystems-integration

A multitude of interested parties surround an organisation, that is, persons or other organisations that are affected by, or have an interest in, the organisation’s outcomes, positive or negative. Quality-as-ecosystems-integration consists of the web of interactions within which actors integrate resources and create value. Quality is constructed among the actors within the system intersubjectively and is driven by shared ideals.

Constructed intersubjectively in groups of stakeholders

Ideological, in the sense that specific values have been institutionalised within the ecosystem (e.g. quality in guitars perceived as high quality within the ecosystem of blues guitarists differ from the neoclassical hard rock fellows)

Collective and consensus-driven in terms of the meaning assigned to quality

Examples of quality-as-ecosystems-integration include group-based subjective notions of quality pertaining to similar goods or services. For instance, there is a difference between groups in society in the perception of quality aspects pertaining to cars and car quality. The group of stakeholders/customers advocating the need for Sport Utility Vehicles (SUV) differ from the group of stakeholders/customers advocating the need for Supermini cars or Subcompact cars. Market segmentation can be argued to be a result of intersubjective, group based and constructively formed notions of what represents good quality. The same group-based notions also apply to a wide spectrum of other consumer/customer areas such as collecting (e.g. fine art, furniture, wristwatches etc.), sports and interior decoration. Quality-as ecosystem-integration can thus be manifested through social community groups e.g. Facebook groups. Such manifestations of quality-as-ecosystem-integration may include a wide variation of ever-changing group-based and constructively formed notions of what represents value and quality that continuously evolve and differ between groups within any particular area.

3.3.4. Quality-as-society-values

The societal perspective of quality incorporates the values of sustainability. In contrast with the Quality-as-ecosystems-integration, the social perspective is broader and includes actors that not necessarily have a direct relationship with the product in focus. The pressing challenge for societies and humanity is making it progressively into many organisations’ agendas. The quality aspects are ultimately derived from research and facts and are not dependent on particular subjective group and/or actor needs. Thus, quality is not subjectively constructed, but rather objectively extracted from facts-based knowledge founded in research. As such, the definition of Quality-as-society-values is subordinated to predefined and objectively established research-based knowledge. The drivers of what constitutes quality stem from an urge to realise that economic, social, and environmental sustainability often go hand in hand. The following aspects are central to this perspective:

Sustainability as a key concern in all practices

Research-based knowledge as a basis for what constitutes quality

Holistic perspective on what quality is and how it impacts various stakeholder

Examples of Quality-as-society-values can include the performance of combustion engines pertaining to carbon dioxide and nitrogen emission rates, the availability of health and social services to all citizens on equal terms, that the quality in engineering and construction products do not compromise the safety and security of tenants or other stakeholders or that the production of goods and services does not harm or endanger the employees or other stakeholders directly, or indirectly affected by the production.

3.3.5. Quality-in-use

The interplay of different perspectives gives a comprehensive understanding of working with quality. A qualifier in our pursuit is that we assume a pragmatic view, denoted Quality-in-use. Thus, quality has many different meanings that need to be considered depending on the particular context in which value and needs of customers and stakeholder must be addressed. Therefore, the scope and form of quality differ depending on whether single actors (or groups of single actors) or multiple interested parties are in focus and whether the meaning of quality is subjectively constructed or objectively predefined. This doesn’t mean that all definitions of quality could or even should take into account all the different perspectives in every instance, but rather for the arbiters of quality to be open for alternatives and creative synthesis that might be beneficial for an organisation’s struggle to create better and more targeted meanings of quality. Indeed, when analysing quality using the proposed framework, there will likely be conflicts and contradictions that suppliers must recognise and reflect upon in order to satisfy needs and values beyond traditional conceptions of customers and stakeholders. Therefore, we draw upon the proposition by Van de Ven and Poole (Citation1995) in that different perspectives in a framework for understanding a certain phenomenon (be it change, quality or any other crucial phenomena) might be integrated if they provide alternative views of the same phenomena without eliminating each other. Thus, the framework we are suggesting should be viewed as complementary in terms of the four forms of quality proposed, hopefully leading to better explanatory power and understanding of the meaning of quality.

4. Discussion and concluding remarks

The purpose of this conceptual paper was to elaborate on the concept of quality as practiced and extend this understanding in a framework designed to include objective and subjective aspects from a broad range of stakeholders. What are the motives of this exercise? Is there a need for new perspectives on quality? The paper witnesses, for instance, the problems in defining quality within public services where service providers need to balance the value experienced by the beneficiary with the professionals’ understanding of quality, and public values of quality that goes beyond any individual who is using the service. Moreover, private organisations’ experiences that their highly regarded products of high quality nevertheless cause negative environmental consequences, which also calls for a new approach to what constitutes quality.

Considering the arguments presented in this paper and the contemporary challenges, for example, in the area of sustainability, we propose the following four perspectives on the many meanings of quality: Quality-as-customer-value, Quality-as-agreed-delivery, Quality-as-ecosystems-integration, and Quality-as-society-values. The point of the paper is not that there is a need for a new definition but that we need to consider many different angles and that quality-in-use may enhance the actual practices of Quality Management. One benefit of applying a framework that displays multiple ways of viewing quality is that it both points to areas where quality and sustainability might be mutually supportive, but at the same time makes trade-offs and conflicts visible so that they can be managed in a good way. Having a broadened perspective of who the customer is – moving from individual to collective – and viewing Quality-as-society-value can help identify aspects that are critical for either environmental or social sustainability. Having identified this, a second step can be to have discussions on characteristics to be included in product or service specifications, hence Quality-as-agreed-delivery; a discussion that can include reflections on how specifications can include aspects that are beneficial for sustainability. Thus, Quality-in-use for goods and services is based on considerations of both single actors (individual perspective) and multiple interesting parties (collective perspective). Another example of how Quality-in-use is shaped is if Quality-as-customer value is challenged and contrasted with Quality-as-ecosystem-integration. Taking the example of mobile phones a sole focus on Quality-as-customer value might lead to a decision on rapid introductions of new models, whereas a simultaneous discussion on Quality-as-ecosystem-integration could point to groups of environmentally aware customers that might be willing to replace frequent model changes for updates of their existing phones that can enhance and add functionality without replacing eco-hazardous hardware (e.g. earth metals in mobile phones).

The managerial implications of the proposed framework are based on a desire to aid in the understanding of current, and future roles of quality practitioners (Elg et al., Citation2011; Waddell & Mallen, Citation2001), as well as the competencies (Martin et al., Citation2019; Ponsignon et al., Citation2019) required in these roles. As an example, the scope dimension opens for discussions on competencies needed to work with quality improvements that supports increased value for buyers and users but at the same time minimised environmental impact. Such discussions might also aid in organising quality work, either in a way that integrates quality and environmental sustainability in one organisation, or in two separate but collaborating organisations (Siva et al., Citation2018).

Regarding theoretical implications, this paper revisits and focuses on aspects of Quality Management such as criticality of the subjective side of quality (Shewhart, Citation1931), and the need to consider the impact of quality loss in terms of societal damage (Taguchi & Wu, Citation1979). These are aspects that have been proposed long time ago, but that sometimes are forgotten in a time where sustainability challenges make them more topical than ever. Aligned with sustainability considerations the framework puts focus on a need to expand the view on customers to include multiple customer roles (Lengnick-Hall, Citation1996), as well as stakeholders (Isaksson & Garvare, Citation2003) including the society and our natural environment. Being a conceptual paper, this paper could be seen as one step in theorisation on the concept of quality in relation to its scope, form, and relation to sustainability.

A limitation of this paper lies in its conceptual nature, aiming to detail, describe, and relate (MacInnis, Citation2011) quality to two key dimensions in a conceptual framework that would naturally benefit from exploration in empirical studies. On a general level, a survey study of how quality practitioners view quality in terms of its inherent meaning would be an avenue for future research. Pursuing such a study would also entail operationalising the proposed framework into a survey instrument, which could be of use for research purposes as well as for assessment of Quality Management practice. Moving to the four specific forms of quality proposed in , another research avenue would be case studies focusing each of these forms and relating them to their impact on environmental, economic, and social sustainability. Such studies would benefit both academia and practice by supporting the field of quality to further enhance its contributions to sustainability development.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express gratitude for the support from HELIX Competence Centre at Linköping University, and the Area of Advance Production at Chalmers University of Technology.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Anttila, J., & Jussila, K. (2017). Understanding quality -conceptualization of the fundamental concepts of quality. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 9(3/4), 251–268. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQSS-03-2017-0020

- ASQ (2015). Guide to the quality body of knowledge (QBOK) Version 2.0.

- Assarlind, M., Gremyr, I., & Bäckman, K. (2013). Multi-faceted views on a Lean Six Sigma application. International Journal of Quality and Reliability Management, 30(4), 387–402. https://doi.org/10.1108/02656711211190855

- Backström, T. (2017). Solving the quality dilemma: Emergent quality management. In T. Backström, A. Fundin, & P. E. Johansson (Eds.), Innovative quality improvements in operations. Introducing emergent quality Management (pp. 151–167). Springer.

- Bergquist, B., Garvare, R., & Klefsjö, B. (2006). Quality management for tomorrow. In K. Foley, D. Hensler, & J. Jonker (Eds.), Quality management and organizational excellence: Oxymorons, empty boxes or significant contributions to management thought and practice (pp. 253–286). Standards Australia International Ltd.

- Birch-Jensen, A., Gremyr, I., & Halldórsson, Á. (2020). Digitally connected services: Improvements through customer-initiated feedback. European Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2020.03.008

- Borri, F., & Boccaletti, G. (1995). From total quality management to total quality environmental management. The TQM Magazine, 7(5), 38–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/09544789510098614

- Charantimath, P. M. (2011). Total quality management. Dorling Kindersley, Pearson.

- Corbett, L. M., & Cutler, D. J. (2000). Environmental management systems in the New Zealand plastics industry. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 20(2), 204–224. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570010304260

- Craig, J. H., & Lemon, M. (2008). Perceptions and reality in quality and environmental management systems: A research survey in China and Poland. The TQM Journal, 20(3), 196–208. https://doi.org/10.1108/17542730810867227

- Crosby, P. (1965). Cutting the cost of quality. Industrial Education Institute.

- Dahlgaard Park, S. M., & Dahlgaard, J. J. (2006). Lean production, six sigma quality, TQM and company culture. The TQM Magazine, 18(3), 263–281. https://doi.org/10.1108/09544780610659998

- Dean, J. W., & Bowen, D. E. (1994). Management theory and total quality: Improving research and practice through theory development. Academy of Management Review, 19(3), 392–418. https://doi.org/10.2307/258933

- Deming, W. E. (1986). Out of the crisis. The MIT Press.

- Deming, W. E. (1994). The new economics. The MIT Press.

- Elg, M., Gremyr, I., Hellström, A., & Witell, L. (2011). The role of quality managers in contemporary organisations. Total Quality Management, 22(8), 795–806. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2011.593899

- Evans, J. R., & Lindsay, W. M. (2011). Managing for quality and performance excellence (9th ed.). South-Western Educational.

- Foley, K.J., & Standards Australia International. (2005). Meta-management: A stakeholder/quality management approach to whole-of-enterprise management. Standards Australia.

- Foster, D., & Jonker, J. (2003). Third generation quality management: The role of stakeholders in integrating business into society. Managerial Auditing Journal, 18(4), 323–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686900310474334

- Fundin, A., Bergman, B., & Elg, M. (2017). The quality dilemma: Combining development and Stability. In T. Backström, A. Fundin, & P. E. Johansson (Eds.), Innovative quality improvements in operations. Introducing emergent quality management (pp. 9–33). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55985-8_2

- Garvin, D. A. (1984). What does ‘product quality’ really mean? MIT Sloan Management Review, 26(1), 25–43.

- Garvin, D. A. (1988). Managing quality. Free Press.

- Gölzer, P., & Fritzsche, A. (2017). Data-driven operations management: Organisational implications of the digital transformation in industrial practice. Production Planning & Control, 28(1), 1332–1343. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2017.1375148

- Gremyr, I., Elg, M., Hellström, A., Martin, J., & Witell, L. (2019). The roles of quality departments and their influence on business results. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2019.1643713

- Gremyr, I., Siva, V., Raharjo, H., & Goh, T. N. (2014). Adapting the robust design methodology to support sustainable product development. Journal of Cleaner Production, 79(Sep), 231–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.05.018

- Grönroos, C. (1984). A service quality model and its marketing implications. European Journal of Marketing, 18(4), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000004784

- Grönroos, C. (2006). Adopting a service logic for marketing. Marketing Theory, 6(3), 317–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593106066794

- Grönroos, C. (2008). Service logic revisited: Who creates value? And who co-creates? European Business Review, 20(4), 298–314. https://doi.org/10.1108/09555340810886585

- Grönroos, C. (2011). Value co-creation in service logic: A critical analysis. Marketing Theory, 11(39), 279–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593111408177

- Isaksson, R., & Garvare, R. (2003). Measuring sustainable development using process models. Management Auditing Journal, 18(8), 649–656. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686900310495142

- ISO. (2015). ISO 9001:2015: Quality management systems – requirements.

- Juran, J. M. (1989). Juran on leadership for quality. McGraw-Hill.

- Juran, J. M., & Godfrey, A. B. (1998). Juran’s quality handbook (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Küpper, D., Knizek, C., Ryeson, D., & Noecker, J. (2019). Quality 4.0 takes more than technology. https://www.bcg.com/publications/2019/quality-4.0-takes-more-than-technology.aspx

- Lengnick-Hall, C. A. (1996). Customer contributions to quality: A different view of the customer-oriented firm. The Academy of Management Review, 21(3), 791–824.

- Luttropp, C., & Lagerstedt, J. (2006). Ecodesign and the ten golden rules: Generic advice for merging environmental aspects into product development. Journal of Cleaner Production, 14(15-16), 1396–1408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2005.11.022

- MacInnis, D. J. (2011). A framework for conceptual contributions in marketing. Journal of Marketing, 75(4), 136–154. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.75.4.136

- Marin-Garcia, J. A., & Bonavia, T. (2015). Relationship between employee involvement and lean manufacturing and its effect on performance in a rigid continuous process industry. International Journal of Production Research, 53(11), 3260–3275. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2014.975852

- Martin, J., Elg, M., Gremyr, I., & Wallo, A. (2019). Towards a quality management competence framework: Exploring needed competencies in quality management. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2019.1576516

- Maxwell, D., & Van der Vorst, R. (2003). Developing sustainable products and services. Journal of Cleaner Production, 11(8), 883–895. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-6526(02)00164-6

- Modig, N., & Åhlström, P. (2012). This is lean. Resolving the efficiency paradox. Rheologica Publishing.

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1985). A conceptual model of service quality and Its implications for future research. Journal of Marketing, 49(4), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251430

- Parviainen, P., Tihinen, M., Kääriäinen, J., & Teppola, S. (2017). Tackling the digitalisation challenge: How to benefit from digitalisation in practice. International Journal of Information Systems and Project Management, 5(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.12821/ijispm050104

- Ponsignon, F., Kleinhans, S., & Bressolles, G. (2019). The contribution of quality management to an organisation’s digital transformation: A qualitative study. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 30(sup 1), 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2019.1665770

- Prajogo, D. I., & McDermott, C. M. (2005). The relationship between total quality management practices and organisational culture. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 25(11), 1101–1122. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570510626916

- Radder, L. (1998). Stakeholder delight: The next step in TQM. The TQM Magazine, 10(4), 276–280.

- Sakao, T. (2004, September). Analysis of the characteristics of QFDE and LCA for Eco design support. Paper presented at the Electronics Goes Green Conference, 2004, Berlin.

- Schroeder, R. G., Linderman, K., Liedtke, C., & Choo, A. S. (2008). Six Sigma: Definition and underlying theory. Journal of Operations Management, 26(4), 536–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2007.06.007

- Shewhart, W. A. (1931). Economic control of quality and manufactured product. Van Nostrand.

- SIQ. (2018). SIQ Management model.

- SIQ. (2020). https://forum.siq.se/den-femte-kvalitetsvagen/

- Siva, V., Gremyr, I., Bergqvist, B., Garvare, R., Zobel, T., & Isaksson, R. (2016). The support of quality management to sustainable development: A literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 13(2), 148–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.01.020

- Siva, V., Gremyr, I., & Halldórsson, Á. (2018). Organising sustainability competencies through quality management: Integration or specialisation. Sustainability, 10(5), 1326. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10051326

- Sony, M., Antony, J., & Douglas, J. A. (2020). Essential ingredients for the implementation of quality 4.0. The TQM Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-12-2019-0275

- Sousa, R., & Voss, C. A. (2001). Quality management: Universal or context dependent? Production and Operations Management Journal, 10(4), 383–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1937-5956.2001.tb00083.x

- Sousa, R., & Voss, C. A. (2002). Quality management re-visited: A reflective review and agenda for future research. Journal of Operations Management, 20(1), 91–109.

- Taguchi, G. (1986). Introduction to quality engineering: Designing quality. Asian Productivity Organization. https://doi.org/10.1002/qre.4680040216

- Taguchi, G., & Wu, Y. (1979). Introduction to off-line quality control. Central Japan Quality Control Association.

- Van de Ven, A. H., & Poole, M. S. (1995). Explaining development and change in organisations. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 510–540. https://doi.org/10.2307/258786

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.68.1.1.24036

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2015). Service dominant logic- premises, perspectives, possibilities. Cambridge University Press.

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2016). Institutions and axioms: An extension and update of service-dominant logic. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-015-0456-3

- Waddell, D., & Mallen, D. (2001). Quality managers: Beyond 2000? Total Quality Management, 12(3), 373–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/09544120120034519

- Wadsworth, H. W., Stephens, K. S., & Godfrey, A. B. (2001). Modern methods for quality control and improvement. John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Zhang, Q. (2001). Quality dimensions, perspectives and practices. A Mapping Analysis. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 18(7), 708–721. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000005777