ABSTRACT

The linguistic choices teachers and educators make in their spheres of influence depend on their own language experiences and how these have shaped their thinking. In this article, we draw on teacher beliefs, social activism and language socialisation perspectives to demonstrate the potential impact of the Multilingual Socialisation (M-SOC) tool. This theory-informed tool was designed to: (1) make visible multilingual practices where they exist; (2) establish a link between biographical experiences, actions and beliefs related to multilingual practices in education; and (3) expose educators less familiar with multilingualism in education to practical ideas, thus enabling reflection and inspiration. This is part of a potentially wider collective action project that has the aim of generating greater acceptance of multilingual practices in education. Here, we present and evaluate the first stage of the M-SOC project and a follow-on consultation phase and draw conclusions for future research. The quantitative and qualitative analyses of the first results (n = 81) from our ongoing data collection indicate that the M-SOC tool has a role to play as an effective theory-informed teacher development tool that is able to identify, inform and change teachers’ thinking and intentions regarding their classroom practices.

1. Introduction

In academic circles, interest in multilingualism in education has reached a critical mass in recent decades and is discussed under the umbrella of the multilingual turn (Conteh & Meier, Citation2014; May, Citation2014). However, this academic interest is not mirrored in practice where a monolingual mind-set continues as a widespread and arguably problematic organising principle in education (Cruickshank, Citation2014; Gajo, Citation2014; May, Citation2014, Citation2019; Ortega, Citation2014). Anecdotal evidence from educational contexts fills us with confidence, however, that multilingual practices in education may exist more widely than is often thought, or that educators may be interested in principle. This means that multilingual practices and interests are hard to quantify and may often go unnoticed by wider academic, professional or societal communities due to their dispersed and local nature.

In order to learn more about educator practices and interests, as well as to provide some guidance that may be helpful for teachers, we developed an online self-study tool that simultaneously acts as a research instrument. This tool is part of our multilingual socialisation in education (M-SOC) project and was designed to raise awareness and invite reflection. In this article, we present and evaluate the first stage of this ongoing project, namely the online M-SOC tool, which has three aims:

To gain an overview of practices and perceptions: make visible educators’ experiences, practices, interests and perceived challenges related to multilingual practices in education;

To generate educator awareness of practices and perceptions: enable reflection to inform and potentially transform teachers’ beliefs through sharing of dispersed local practices;

To identify and engage with educators in geographically dispersed contexts who share an interest in multilingual socialisation and multilingual classroom practices: learn about what educators do, and recruit participants for a follow-on project as part of a wider collective action campaign.

In order to present the M-SOC tool, related findings and an evaluation of its potential for collective action, we will first review literature about teacher beliefs, social activism theory and language/multilingual socialisation. We then go on to explain the methodology behind our on-line M-SOC tool (Meier & Wood, Citation2019), before we present initial findings and an evaluation of our tool. Our findings lead us to make recommendations about how the M-SOC tool can be used, and first responses to our follow-on consultation help us understand the desire for future collective action.

2. Literature review

In this section, we will first draw on literature related to teacher beliefs and factors that can inform and transform them. We then consider social activism theories to illustrate how societal and discursive change could in the long-term, be brought about through a project like ours. Finally, we draw on language socialisation perspectives as they informed the creation and development of the M-SOC tool.

2.1 Teacher beliefs

There is agreement in educational literature that teacher beliefs are strong indicators of what teachers do in classrooms (Egli Cuenat, Citation2007; Wokusch, Citation2008). Teacher beliefs are often stronger than theoretical knowledge (Woods, Citation2006). Thus, this area of educational study is highly relevant for our project. We found that factors that influence teacher beliefs include: their own learning experiences (Blömke et al., Citation2008; Uzum, Citation2017), often guided by monolingual norms (Le Pape Racine, Citation2007; Wokusch, Citation2008; Wokusch & Lys, Citation2007); and contextual circumstances (Uzum, Citation2017). Schedel and Bonvin (Citation2017) suggest that linguistic repertoires may also influence teacher’s mind-sets. In addition, teacher beliefs have been described as unconscious ‘filters’ that resist information that is incompatible with the existing framework of beliefs (Blömke et al., Citation2008).

We are aware that our mind-set as language teachers and teacher educators has been informed, and over time transformed, by our personal and professional linguistic experiences and our reflection on these, above all through academic study, research and our own migratory experiences. Indeed, research shows that language teachers can modify their beliefs when given an opportunity to reflect and gain consciousness of them (Cabré Rocafort, Citation2019), above all, as part of their teacher education (Müller et al., Citation2008) and through dialogue with researchers (Uzum, Citation2017). The M-SOC tool, that invites teachers to reflect on their experiences and beliefs, has similar potential as we will show below.

Lamb (Citation2018) showed that there may be another route to influence people’s beliefs, namely by including them as participants in research. Our study was consciously designed to make use of this ‘investigator effect’ and to enable theory-informed reflection, as part of our data collection.

The insights from teacher belief literature informed our project, insofar as the M-SOC tool contains statements related to the participants’ linguistic repertoire, experience, practice, interest in and scepticism towards multilingual socialisation in education, as well as perceived contextual challenges (see Meier & Wood, Citation2019 [survey for participants], and Meier & Wood, Citation2021 [survey in PDF format including all statements]).

2.2. Social activism perspective

Social activism perspectives focus on collective actions that shape how people in societies talk and think about the world and how this could be organised (Atkinson, Citation2017). Literature (e.g. Albaugh, Citation2014; Benson & Wong, Citation2019; Dmitrenko, Citation2017; Elsner, Citation2018; Gajo, Citation2014; May, Citation2019) and anecdotal evidence we have gathered as teachers and teacher educators suggest that there have been shifts in educational discourses towards greater acceptance of multilingual practices, albeit in a dispersed and localised manner. When enough people start to change something at grassroots level, social activism researcher Atkinson (Citation2017) refers to ‘shifts in meaning structures across society’ (p. 26). Researchers in the field of social activism (e.g. Atkinson, Citation2017; Welch & Yates, Citation2018) agree that shifts of meaning, and ensuing activities, may start out as isolated, latent or dispersed phenomena, which are a precondition for any joined-up social activism in the future. In order to turn dispersed collective action, or latent networks of people who do not know one another, into wider social activism or collective action, members need to find a joint voice (Welch & Yates, Citation2018). Based on this, the M-SOC tool has the aims of making visible dispersed multilingual practices and activities, while identifying potential participants who may want to find a joint voice and form part of a future M-SOC project. Through our project, we aim to generate more visible and concrete networks that can bring about social change in the longer term. This is based on Welch and Yates (Citation2018), who associate social change with joined-up networks, and on Ortega (Citation2014), who calls for collective action to challenge monolingual assumptions.

2.3. Language socialisation

‘Language is the central dimension of socialisation’ (Ganek et al., Citation2019, p. 140). Young people learn which languages, language varieties and styles play what role in which social situations. Language socialisation has been defined as ‘meaningful action that occurs routinely in everyday life, is widely shared by members of the group, has developed over time, and carries normative expectations about how it should be done’ (Moore, Citation2005, p. 72) and is based on prevailing ideologies (Duff & Talmy, Citation2011). Some argue that organising school and learning around the dominant standard language, such as English in the UK, alone amounts to institutionalised discrimination (Cummins, Citation2001; Gomolla & Radtke, Citation2007; Stanat & Christensen, Citation2006) and that it systematically disadvantages children with non-standard (e.g. a dialect) or non-dominant language backgrounds. Depending on a person’s socialisation and ensuing belief system, some members of societies may welcome linguistic diversity in education, while others may see this as a threat to learning and to society more widely (Baker, Citation2006). Often, however, people reproduce monolingual norms, as this is what they have experienced through their own language socialisation (Kubota & Lin, Citation2006), sometimes without even being aware of this. Ortega (Citation2014) views monolingual norms as amounting to ‘damaging deficit approaches [that] become unwittingly entrenched in many practices found in classrooms and schools’ (p. 36). Be this as it may, monolingual understandings have ‘prevented scholars from appreciating plurilingualism’ (Canagarajah & Liyanage, Citation2012, p. 50) as many consider other languages as a problem rather than as a resource (Young, Citation2014).

Duff (Citation1995) argues that there is a reciprocal relationship between what people do (language practices and social interaction) and how people think, behave and feel about what they do (domains of knowledge, beliefs, emotions, roles, identities and social representations). Indeed, Friedman (Citation2010) describes the powerful roles teachers play in the linguistic socialising process of students. She argues that teachers can perpetuate traditional practices, but they can also facilitate social change, depending on how they think and act. This idea was a starting point for our project, as one of our foci was the potential for transformation of teacher beliefs and practices, in other words how a change in teacher thinking and awareness may change what they do in the classroom.

2.4. Multilingual socialisation in education

There have been very few publications theorising multilingual socialisation, specifically. Based on a review of relevant literature, Meier (Citation2018) proposed that multilingual socialisation in education can be divided into five domains as follows.

Domain 1 – Creating a multilingual educational environment: the potential to make multilingualism visible and normalise the idea of multilingualism in wider educational environments. This can send the message that schools or other educational settings are designed for people with more than one language as legitimate members of the educational community.

Domain 2 – Developing awareness about languages, language ideologies and attitudes: practices that foster curiosity and reflection on different languages, including those used and learned in education, as well as those that do not form part of the curriculum. This can generate consciousness of how and when different languages are used and for what purposes. It also uncovers power dimensions related to languages.

Domain 3 – Making connections between languages in order to study form: supporting language study by building on prior meta-linguistic knowledge. This enables learners to compare and contrast different languages and gain awareness of any similarities and differences, thus developing a more integrated and cross-linguistic understanding of languages. This is based in the cognitive-linguistic tradition and relates to cross-linguistic learning strategies.

Domain 4 – Making connections between languages for real communication: using multiple languages for real communicative and interaction purposes to develop receptive (reading, listening) and productive (writing, speaking) fluency and automaticity. Learners can develop multilingual communicative strategies that help them make sense of spoken and written texts by using different languages and mixtures of languages they know.

Domain 5 – Multilingual approach to (self-)evaluation: supporting students to become aware of their developing linguistic repertoires, and help them interpret their bi- or multilingual achievements and see themselves, and the role they play in the language socialisation of learners, in a positive light. This is about gaining awareness and appreciation of one’s linguistic knowledge and abilities in a more holistic way, and preventing learners from seeing some of their languages as problems.

We took the statements Meier associated with these domains and adapted these for our M-SOC tool.

3. Developing the M-SOC tool

In this section, we explain how we developed the M-SOC tool and evaluated this based on the first batch of data collected. This is the first stage of our on-going M-SOC project.

3.1. M-SOC tool for data collection

The mainstay of the online M-SOC tool is a section that enables self-assessment of the linguistic repertoire based on the CEFR (Council of Europe, 2001) and 94 statements related to multilingual socialisation, divided into five domains, which have been adapted from Meier (Citation2018), as follows.

‘Display multilingual artefacts’. (Domain 1)

‘Encourage learners to find out about languages spoken in their community’. (Domain 2)

‘Make links between a new language and the learners’ other languages’. (Domain 3)

‘Create opportunities to use different languages’. (Domain 4)

‘Praise all curiosity about languages’. (Domain 5)

The M-SOC statements were formulated to collect standardised data, specifically multi-item scale data in a matrix format, as well as open-format data in the form of free-text comments. Guided by the literature in Section 2.4, the matrix response categories included the following dimensions:

I experienced this in my own education (own language socialisation)

I do this with my students (teacher practice)

I would be interested in trying this out (acceptance of idea, but not yet adopted)

This would be challenging in my current setting (recognised as contextual challenge)

I don’t believe this is helpful (potential theory filter, not relevant or appropriate)

Participants were asked to tick one or more response categories. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Exeter (Ref STF/17/18/08) and, after piloting, the survey was launched in its current form in Exeter in March 2019 (Meier & Wood, Citation2019). The survey including all 94 statements and dimensions (Meier & Wood, Citation2021) is publicly accessible through the IRIS Repository of Instruments Marsden et al. (Citation2016).

3.2. M-SOC tool for teacher development

Because of the survey’s nature as a reflective tool, we disseminated the M-SOC tool as a research and self-study tool suitable for teacher development. At the end of the unit, the participants are given the opportunity to print out their answers, with a list of online resources. We inserted a question at the end about what the participants learnt by engaging with the M-SOC tool, which yielded fascinating insights, as reported in Section 4.5. This had the purpose of highlighting any changes in awareness, beliefs or intentions to alter practices that may have occurred as a consequence. Furthermore, participants have the option to indicate if they are interested in the follow-up project. In Section 5, we explain in more detail how the M-SOC tool (Meier & Wood, Citation2019) can be used by educators and teacher educators as a teacher development tool, which will be available in the foreseeable future.

3.2. Recruitment of sample

We shared the link to the online M-SOC tool through our academic and teacher networks. These contacts were in turn invited to share the link with their teacher colleagues worldwide, using a snowball sampling technique. For the purpose of this project, we define ‘educators’ as teachers, tutors or lecturers at all levels and in all disciplines, including in pre-school, primary, lower and upper secondary schools, as well as undergraduate and postgraduate university and vocational lecturers/tutors, who work in state or independent institutions and who teach any subject.

At the time of writing, we had collected 81 responses. We treated this as a test sample, as it is largely, but not exclusively, made up of participants from our own networks, who tend to be familiar with multilingual theories and practices to varied degrees. Unfortunately, the M-SOC tool is available in English only at the moment, which may limit participation of more linguistically diverse educators.

4. Analysis and findings

We used quantitative and qualitative analyses to uncover emerging patterns and information, which allowed us to evaluate the M-SOC tool and relate our findings to theory.

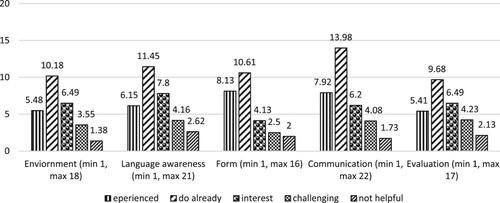

Using frequency calculations enabled us to describe the sample, in terms of the M-SOC statements most often selected per domain, as well as averages per domain and dimension. Each of the five M-SOC domains contains a number of statements. The responses were added up for each participant, using SPSS, based on which five average scores were calculated per domain (experienced, do already, interest, challenging, not helpful). The minimum score was 0 (no statement ticked), and the maximum scores were between 16 and 22 (all statements were ticked), as shown in .

In addition to descriptive analysis, we used these scores to calculate the statistical significance of correlations between dimensions to identify any patterns. We correlated dimensions within each domain, e.g. between what participants have experienced or do already in their classrooms. The strength of correlations is expressed by Pearson’s rho (r), and statistical significance by the p value, which indicates probability at 95% (*) and 99% (**) confidence levels.

The free-text responses were coded and rearranged thematically as suggested by Maguire and Delahunt (Citation2017). As can be seen in Section 4.5, these qualitative findings help interpret and illuminate the statistical findings, and above all raise new questions.

4.1. Description of the sample

We had data from 81 participants, of whom 53 completed the survey while others did not respond to all questions. We included all responses for analysis. This sample consists of 38 teachers/lecturers, 21 teacher educators, 3 trainee teachers, and 8 who work in ‘other’ contexts, such as in educational consultancy or in educational research (missing: 11). They reported that they work as modern foreign language teachers (n = 22), as second/additional language teachers (n = 19), and as subject teachers in social sciences (n = 3) and humanities (n = 2), IT and mathematics (n = 1), several subjects (n = 9) and ‘other’ (n = 14) which are mostly language-related subjects (missing: 11). The participants associated themselves with undergraduate (n = 12) and postgraduate (n = 16) university education, with secondary (n = 14) and (pre)primary (n = 17) school education, with vocational education 1, and other (n = 10) education-related work (missing: 11). The data collected showed that the snowballing method is able to reach colleagues globally, albeit with a UK bias: participants worked in the UK (n = 27), in Spain (n = 11), and others worked in 10 continental European countries (n = 21), in 3 Asian countries (n = 5), in the Middle East (n = 3), in the USA (n = 1) and in New Zealand (n = 2), again 11 were missing. Not surprisingly perhaps, their place of work is in many cases not an indication of origin, as participants had 27 different nationalities from different continents (missing: 11), including South America and Africa. This sample is very experienced, 11 participants had 0–5 years’ experience, eighteen 6–15 years, twenty-eight 16–25 years and twelve had more than 26 years of teaching experience (missing: 12). Regarding their linguistic repertoires, 67 out of 81 participants indicated that between them they can use 48 languages (missing: 14). Individually they can use between 1 and 13 (!) languages; on average each person can use 3.6 languages.

4.2. Statements most often selected

The statements selected most per dimension are shown in . The statement and dimensions ticked by more participants than any other was that participants have experienced in their own education that their educators were interested in their linguistic repertoires (n = 51). This statement was also the one most frequently selected in terms of what participants do with their own students (n = 22). The idea that most participants were interested in trying out was the use of multilingual ice-breakers (n = 32), followed by designing tasks with multilingual group outcomes (n = 29). As can be seen from , extracurricular activities in different languages were perceived as challenging by an equal number of participants (both n = 15). The idea that was perceived by the highest number of participants (n = 9) as not helpful was related to language rules in the classroom.

Table 1. Statements selected most per dimension and domain.

In the future, the ideas most often selected in the M-SOC tool could be developed into concrete activities, while challenges and less helpful ideas could be explored in more depth with educators in diverse settings to understand obstacles and limitations.

4.3. Average number of statements selected

We calculated the average frequency of dimensions per domain, as illustrated in , which enabled us to see patterns. We calculated this by adding up all scores per domain and dimension and then calculating the average score based on all participants. As expected, these averages suggest that multilingual practices exist – the dimension most often selected in all domains is that of what participants do already (average between 9.68 and 13.98). We also found that some ideas, but to a much smaller extent, were perceived as challenging (average between 3.55 and 4.16) and/or unhelpful (average between 1.38 and 2.62). The average of what participants experienced themselves (between 5.41 and 8.13 statements ticked) and of what they are interested in trying out (average between 4.13 and 7.8) are comparable but vary in each domain.

Correlation analysis, which we report next, shows to what extent these dimensions may be statistically related.

4.4. Correlation analysis

Informed by theory, we looked for correlations between what educators do in their practice and two other dimensions: what they have experienced themselves and the number of languages they can use.

Firstly, our analysis showed that there is a consistent and positive correlation between what participants say they do already with their students and what they have experienced in their own education. These correlations are consistent in all domains. We identified statistically significant correlations in three domains: language awareness r 0.415*, p .039, n = 25, approach to form r 0.774**, p .000, n = 22, and approach to communication r 0.429*, p .041*, n = 23. This means that the greater the extent to which teachers have experienced multilingual practices in their own education the greater the likelihood that they have adopted such practices in their own classrooms. These findings resonate strongly with previous research (Blömke et al., Citation2008; Le Pape Racine, Citation2007; Wokusch, Citation2008; Wokusch & Lys, Citation2007), as our findings confirm that biographical factors are indeed important in determining what teachers do in their classrooms. Given this consistent agreement, we can presume that the M-SOC tool is theoretically sound.

Secondly, our analysis revealed a positive correlation between what multilingual practices participants say they have adopted and the number of languages in their repertoire (number of languages they can use at any level). Again the correlations are consistent in all domains, and statistically significant correlations were found in two domains: language awareness r 0.334*, p .014, n = 53 and evaluation r 0.300*, p .031, n = 56. These results mean that the more languages a participant has in their linguistic repertoire, the more likely they are to adopt multilingual practices, or the opposite: the less languages a participant has the less likely they are to adopt multilingual practices. Therefore, our results strengthen Schedel and Bonvin’s (Citation2017) findings that personal linguistic repertoire might indeed influence readiness to use multilingual activities. The convergence of our findings with existing theory again supports reliability of the M-SOC tool, and supports the emerging theoretical base that language competences, or a lack of these, can influence teacher beliefs, and in all likelihood, their behaviour related to language socialisation in their sphere of influence.

Thirdly, there is also a statistically significant correlation between what participants have experienced and their linguistic repertoire r 0.328*, p .042, n = 39. This suggests that the more participants have experienced multilingual practices themselves, the greater the number of languages in their linguistic repertoire, or conversely, the more languages they were able to use, the more multilingual practices they experienced. This may not be surprising as learning environments that make languages visible may be more conducive to language learning. However, follow-on research will have to establish in what ways these dimensions are related, as responses from the M-SOC tool alone cannot provide such information.

4.5. Qualitative comments

We analysed the comments provided at the end of the survey, which aimed to: (1) establish what participants felt they had learnt by using the M-SOC tool, and (2) invite general comments related to the M-SOC tool. Out of the 81 participants, 44 responded to the question on what they had learnt, and 59 added general comments. We analysed these quotes thematically, which resulted in six themes (reported in Sections 4.5.1 to 4.5.6). These findings illuminate and deepen the quantitative findings and show potential ways forward for the next stages of the project.

4.5.1. Becoming aware of multilingual practices

Theme one shows that the M-SOC tool helped language and content teachers in different contexts to become more aware of their own multilingual experiences and of what they do already with their learners. The latter is powerfully illustrated by a UK social science tutor (No. 43): ‘As a bilingual teacher myself, I actually do quite a bit (until now subconsciously) to encourage language awareness and multilingualism awareness in my students’. This suggests the potential of this tool to inform teacher beliefs, by raising awareness of multilingual practices that had not been previously recognised as such. Follow-up research could deepen our understanding of how reflection with M-SOC may change teacher beliefs through gaining awareness, as is suggested by Cabré Rocafort (Citation2019), and illustrated by participant No 43.

4.5.2. Perception of challenges

Our analysis shows that the M-SOC tool is able to uncover perceptions related to challenges that participants associate with wider implementation of multilingual practices. For instance, a UK English teacher at a university in Sri Lanka (No 48) feels s/he would need support from management to make relevant changes, and that colleagues largely embrace monolingual norms. Along similar lines, an English teacher from a UK university (No 4) believes that: ‘In EAP and in TEFL I think there is a culture of “English Only!” that will take a lot to get past’. Findings such as these show that the spread of monolingual norms continue to be influential, as found by May (Citation2019) and Ortega (Citation2014), for instance. Furthermore, they suggest that any changes cannot be brought about by single teachers alone. Indeed, they strengthen the rationale for joining up dispersed educators, and enabling them to share experiences of how to deal with such situations.

4.5.3. Transformation of beliefs and intentions

The qualitative statements suggest that engaging with the M-SOC tool may lead to a change in teacher beliefs and thus in intentions to act. This potential for transformation is illustrated by a newly qualified primary teacher from the UK (No 36), who at the beginning of the survey commented ‘I feel stretched enough keeping up with the current demands’, thus expressing the view that multilingual practices were not feasible for a newly qualified teacher. Later on in the survey, the same teacher wrote:

Having moved further forward with the survey I have already established that a lot of these things can be done day-to-day without a huge amount of planning and perhaps I have made a mountain out of a mole hill in how to incorporate these ideas into lessons. I have already begun adapting a plan for tomorrow to include home language interaction and discussion! (Teacher No 36)

4.5.4. Teachers’ role in normalising multilingualism

Our thematic analysis showed that some teachers see it as their responsibility to transform the discourse in wider society by promoting multilingual thinking in their classrooms. The way some teachers have embraced this responsibility is illustrated by a comment offered by an Austrian English teacher (No 21): ‘I see it as my job as a teacher to help students expand and change their views about language, language use and themselves. In my experience, this is the best way to truly enjoy a language’. This theme resonates with Friedman’s (Citation2010) finding which highlights the important role teachers play in the linguistic socialisation of their learners and indirectly of the wider society, and in bringing about social change. While the teacher quoted here did not refer to wider society or social change explicitly, future research could explore to what extent linguistic socialisation in classrooms permeates to the wider society by influencing learner views.

4.5.5. Developing a sense of belonging

Our thematic analysis illustrates that the M-SOC tool may be useful to provide teachers in dispersed contexts with a sense that they are not alone, and that they belong to a greater group of people with an interest in multilingual practices. By becoming an M-SOC participant, educators report that they realised that they are not ‘alone in valuing multilingual approaches in the classroom’ as expressed by an English teacher from Sri Lanka (No 48). This reported sense of not being alone suggests that the M-SOC tool can generate a sense of belonging with other like-minded teachers, even if they do not know each other. We envisage our follow-on project to build on this by facilitating contact and collaboration between participants locally and globally who may thus be able to find a greater sense of belonging to a concrete group and a joint voice, as suggested by Welch and Yates (Citation2018).

5. Towards joined-up collective action

In this paper, we presented the first stage of our M-SOC project. This drew on teacher beliefs, social activism and multilingual socialisation perspectives to justify, develop and evaluate an online research and impact instrument we refer to as the M-SOC tool. In this section we summarise the potential of this tool, and report initial findings from our follow-on consultation to guide our next steps.

5.1. M-SOC as a theory-informed teacher development and impact tool

The online survey offers an opportunity for pre- or in-service self-study and teacher development. This can facilitate reflection on experience, practice, interest, challenges and scepticism related to multilingual socialisation. The M-SOC tool is a ready-made online resource that is available free of charge (Meier & Wood, Citation2019) and can be – and has been – used in workshops for pre-/in-service teacher development. Based on their particular interests, pre-service teachers could individually or jointly develop, trial and evaluate their ideas as part of their professional development and/or research. The statements included in the M-SOC tool are available as part of the downloadable instrument (Meier & Wood, Citation2021), for those who would like to see the statements without filling in the online survey, or who would like to fill this in off-line. The M-SOC tool in its current form will continue to be available online until at least 2024.

Furthermore, the M-SOC tool enables us to make visible, dispersed multilingual practices, and generate awareness of teacher beliefs by offering an opportunity for reflection. It has been shown to create direct impact by influencing the intentions of some or our participants. Upon completion of the M-SOC tool, a PDF with individual responses can be downloaded by participants and used for continuing professional development, or as inspiration to try out some of the ideas contained in one or more of the domains in the future.

5.2. Insights from a follow-on consultation

Alongside the first M-SOC stage we opened a consultative phase among M-SOC users in July 2020. Through this, we aimed to find out about any interest that may exist among colleagues to turn the dispersed awareness of multilingual socialisation in education into a more joined-up and collective one, as suggested by Welch and Yates (Citation2018). By September 2020, we had heard from eight participants who suggested that purposes of a network could include sharing experiences and resources, learning about theories, collaboration and networking, as well as campaigning and engaging in research, specifically making children and teachers’ voices heard and designing materials to create greater awareness. Indeed, a colleague from Norway suggested that we need to ‘come up with concrete pedagogical strategies that could be implemented, trialled, evaluated in the classroom context so it has some real world/classroom relevance’. Furthermore, a colleague from Barcelona recommends future projects to be composed of multi-stakeholder teams including schools, universities and policy makers. These latter points highlight limitations of our project: While this article makes educators’ voices heard, our project was not designed to include learner voices. Similarly, while the M-SOC survey attracted participants from schools, colleges and universities, it did not include policy makers. These are points that need to be taken into consideration in the next stages of the project. Our follow-on consultation further indicated that colleagues working in schools and colleges might see their scope of action inside their respective institutions, whereas colleagues working in universities may see their sphere of influence in education and the wider society, including policy. This, reinforces the point that multi-agency working, including all stakeholders of education, may be required to influence social reality and inspire social change.

5.3. Next steps: maximising the M-SOC potential

We have shown that engagement with the M-SOC tool challenged the beliefs of some of our participants. Moreover, we have shown that this experience is shared by a number of researchers and educators in their dispersed practices around the world. Furthermore, based on the evidence here presented, we argue that the M-SOC project has a role to play in longer-term social change that may go beyond education. This is of wider societal importance, as we feel young people ought to be socialised into a world where speakers of all languages are respected and valued as equals, and where multilingualism is seen as a resource and a unifying force, rather than as a threat and a problem.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks go to editors, friends and colleagues as well as peer reviewers for feedback on previous versions of this article, and to participants for engaging with the M-SOC tool and sharing the link with others.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Albaugh, E. (2014). State-building and multilingual education in Africa. Cambridge University Press.

- Atkinson, J. (2017). Journey into social activism: Qualitative approaches. Fordham University Press.

- Baker, C. (2006). Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism (4th ed.). Multilingual Matters.

- Benson, C., & Wong, K. M. (2019). Effectiveness of policy development and implementation of L1-based multilingual education in Cambodia. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 22(2), 250–265. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2017.1313191

- Blömke, S., Müller, C., Felbrich, A., & Kaiser, G. (2008). Entwicklung der erziehungswissenschaftlichen Überzeugungen in der Lehrerausbildung. In S. Blömke, G. Kaiser, & R. Lehmann (Eds.), Professionelle Kompetenz angehender Lehrerinnen und Lehrer (pp. 303–326). Waxmann.

- Cabré Rocafort, M. (2019). The development of plurilingual education through multimodal narrative reflection in teacher education: A case study of a pre-service teacher’s beliefs about language education. Canadian Modern Language Review, 75(1), 40–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.2017-0080

- Canagarajah, S., & Liyanage, I. (2012). Lessons from precolonial multilingualism. In M. Martin-Jones, A. Blackledge, & A. Creese (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of multilingualism (pp. 49–65). Routledge.

- Conteh, J., & Meier, G. (Eds.). (2014). The multilingual turn in languages education: Opportunities and challenges. Multilingual Matters.

- Cruickshank, K. (2014). Exploring the -lingual between bi and mono: Young people and their languages in an Australian context. In J. Conteh & G. Meier (Eds.), The multilingual turn in languages education: Opportunities and challenges (pp. 41–63). Multilingual Matters.

- Cummins, J. (2001). Language, power and pedagogy: Bilingual children in the crossfire. Multilingual Matters.

- Dmitrenko, V. (2017). Language learning strategies of multilingual adults learning additional languages. International Journal of Multilingualism, 14(1), 6–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2017.1258978

- Duff, P. (1995). An ethnography of communication in immersion classrooms in Hungary. TESOL Quarterly, 29(3), 505–537. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3588073

- Duff, P., & Talmy, S. (2011). Language socialization approaches to second language acquisition: Social, cultural, and linguistic development in additional languages. In D. Atkinson (Ed.), Alternative approaches to second language acquisition (pp. 95–116). Routledge.

- Egli Cuenat, M. (2007). Gezielte und koordinierte Erziehung zur Mehrsprachigkeit/Fremdsprachen in der Volksschule aus Sicht der EDK. PH-akzente, 1, 3–6.

- Elsner, D. (2018). CALL in multilingual settings. Multilingual Matters.

- Friedman, D. (2010). Becoming national: Classroom language socialization and policial identities in the age of globalization. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 30, 193–210. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/s0267190510000061

- Gajo, L. (2014). From normalization to didactization of multilingualism: European and Francophone research at the crossroads between linguistics and didactics. In J. Conteh & G. Meier (Eds.), The multilingual turn in languages education: Opportunities and challenges (pp. 113–131). Multilingual Matters.

- Ganek, H., Nixon, S., Smyth, R., & Eriks-Brophy, A. (2019). A cross-cultural mixed methods investigation of language socialization practices. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 24(2), 128–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/eny037

- Gomolla, M., & Radtke, F.-O. (2007). Instiutionelle Diskriminierung: Die Herstellung ethnischer Differenz in der Schule (2nd ed.). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Kubota, R., & Lin, A. (2006). Race and TESOL: Introduction to concepts and theories. TESOL Quarterly, 40(3), 471–493. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/40264540

- Lamb, M. (2018). When motivation research motivates: Issues in long-term empirical investigations. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 12(4), 357–370. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2016.1251438

- Le Pape Racine, C. (2007). Integrierte Sprachendidaktik – Immersion und das Paradoxe an ihrem Erfolg. Beiträge zur Lehrerinnen- und Lehrerbildung, 25(2), 156–167.

- Maguire, M., & Delahunt, B. (2017). Doing a thematic analysis: A practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. All Ireland Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 9(3), https://ojs.aishe.org/index.php/aishe-j/article/view/335/553

- Marsden, E., Mackey, A., & Plonsky, L. (2016). The IRIS Repository: Advancing research practice and methodology. In A. Mackey & E. Marsden (Eds.), Advancing methodology and practice: The IRIS repository of instruments for research into second languages (pp. 1–21). Routledge.

- May, S. (2014). The multilingual turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL and bilingual education. Routledge.

- May, S. (2019). Negotiating the multilingual turn in SLA. The Modern Language Journal, 103, 122–129. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12531

- Meier, G. (2018). Multilingual socialisation in education: Introducing the M-SOC approach. Language Education and Multilingualism. The Langscape Journal, 11, 103–125. https://edoc.hu-berlin.de/handle/18452/19672

- Meier, G., & Wood, A. (2019). International M-SOC self-study and research survey [access for survey participants]. https://exeterssis.eu.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_5jzUXG2OdYJWn6B

- Meier, G., & Wood, A. (2021). International M-SOC self-study unit and research survey [access to questionnaire in PDF format]. https://www.iris-database.org/iris/app/home/detail?id=york%3a939169&ref=search

- Moore, L. C. (2005). Language socialization. In A. Sujoldzic Section (Ed.), Encyclopedia of life support systems EOLSS. UNESCO.

- Müller, C., Felbrich, A., & Blömke, S. (2008). Schul- und professionstheoretische Überzeugungen. In S. Blömke, G. Kaiser, & R. Lehmann (Eds.), Professionelle Kompetenz angehender Lehrerinnen und Lehrer (pp. 277–302). Waxmann.

- Ortega, L. (2014). Ways forward for a bi/multilingual turn in SLA. In S. May (Ed.), The multilingual turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL and bilingual education (pp. 32–53). Routledge.

- Schedel, L. S., & Bonvin, A. (2017). “Je parle pas l’allemand. Mais je compare en français”: LehrerInnenperspektiven auf Sprachvergleiche. Zeitschrift für Interkulturellen Fremdsprachenunterricht, 22(2), 116–127.

- Stanat, P., & Christensen, G. (2006). Where immigrant students succeed: A comparative review of performance and engagement in PISA in 2003. https://www.pisa.oecd.org/dataoecd/1/57/36667942.doc

- Uzum, B. (2017). Uncovering the layers of foreign language teacher socialization: A qualitative case study of Fulbright language teaching assistants. Language Teaching Research, 21(2), 241–257. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168815614338

- Welch, D., & Yates, L. (2018). The practices of collective action: Practice theory, sustainability transitions and social change. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 48(3), 288–305. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jtsb.12168

- Wokusch, S. (2008). Didactique integrée des langues: la contribution de l’école au plurilinguisme des élèves. Babylonia, 1, 12–14.

- Wokusch, S., & Lys, I. (2007). Überlegungen zu einer integrativen Fremdsprachendidaktik. Beiträge zur Lehrerbildung, 25(2), 168–179.

- Woods, D. (2006). The social construction of beliefs in the language classroom. In P. Kalaja & A. M. Ferreira Barcelos (Eds.), Beliefs about SLA: New research approaches (pp. 201–230). Springer.

- Young, A. (2014). Looking through the language lens: Monolingual taint of plurilingual tint? In J. Conteh & G. Meier (Eds.), The multilingual turn in languages education: Opportunities and challenges (pp. 89–110). Multilingual Matters.