ABSTRACT

Adapting the propositions and concepts of ethnolinguistic identity theory, the present paper examined the interactive effects of identification with English, interlanguage boundary, and the perceived ethnolinguistic vitality of English on mobilising efforts towards English, and competitive efforts against English as a third language among young Swedish-speaking Finns (N = 299). The question is how individuals who already have access to two languages position themselves towards English, and how their disposition towards English relates to identification with the local languages. The data was collected in two Swedish-language secondary schools and analyzed with moderated moderation analysis. The results indicated that the combined effect of identification, interlanguage boundary and English vitality predicted mobilising efforts towards English but not competitive efforts against English. In addition, identification with the majority language Finnish had an impact on both mobilising and competitive efforts, in a way that higher identification with Finnish decreased mobilising efforts and increased competitive efforts against English, while identification with the minority language Swedish did not have an impact on either strategy.

Introduction

For many people around the world, English is a second language (L2) or a third language (L3), acquired through education or due to historical or geopolitical reasons (Cenoz & Jessner, Citation2000). This has changed the linguistic make-up of entire societies, as well as influenced the competence of individuals, according to Hoffman (Citation2000):

From a macrolinguistic point of view we can see the spread of English resulting in a form of societal bilingualism (or multilingualism in communities which are already bilingual), as an ever-increasing number of people use it as a vehicle of communication, not only with native speakers of English but also as a lingua franca in their own contacts with speakers of other languages. (Hoffman, Citation2000, p. 2)

Finland is a typical case, in that English is present on many levels in society, for example in media, education and in work environments (Leppänen & Nikula, Citation2008). It is studied as an L2 or L3 language in schools, and according to some definitions, all Finns can be considered bilingual or multilingual. As in many countries, it is frequently used in business contexts, since ‘English serves as a vehicle for participation in the global economy’ as Spring (Citation2007, p. 64) puts it, and to an increasing extent in service contexts, bars and restaurants, especially in the larger cities (Taavitsainen & Pahta, Citation2003). English is also the lingua franca in academia, even though Heimonen and Ylönen (Citation2017, p. 80) show that 75% of employees in universities in Finland feel that there are reasons to use other languages than English in professional contexts.

This increased use of English can be perceived as a threat to the national languages of the country, Finnish and Swedish, and has caused language professionals to advocate for language planning measures, in order to safeguard the national languages. The current government has responded to this plea and started a project to renew their strategy for the national languages (Finnish government, Citation2020).

Research has addressed various consequences of the advancement and spread of English, but less attention has been paid to how English as a foreign language is perceived as part of individuals’ linguistic identities (but see, Vincze & Joyce, Citation2017; Vincze & Moring, Citation2018). Naturally, the rise of English has important implications in predominantly monolingual contexts, where English can be considered a second language, but the implications are even more interesting in bilingual scenes, where English can be regarded as a third language. The question raised by this study is how individuals who already have access to two languages position themselves towards English, and how their disposition towards English relates to identification with the local languages.

The language situation in Finland

Officially, Finland is a bilingual country, with the national languages Finnish and Swedish, and the Sami languages having a special status. Finnish is the dominant language, with about 4.8 M speakers in 2020. The number of registered Swedish speakers was ca 288,000 (5.2%, total pop. 5,533,793), and the registered Sami speakers were about 2000 (Statistics Finland, Citation2021a). Nevertheless, in practice, Finland is a multilingual country, with about 433,000 inhabitants registered with a foreign language in 2020. Of these, the largest language group is Russian speakers (ca 84,000), followed by Estonian (ca 50,000), Arabic (ca 34,000) and English (ca 23,000) (Statistics Finland, Citation2021b).

In spite of the increasing multilingualism, official Finland mainly recognises the two national languages in laws, regulations and official services. The constitution and the Language Act (6.6.2003/423) regulate the use of Finnish and Swedish in for example government and municipal institutions, the juridical system, official information and the military. Due to its strong status in the legislation, Swedish speakers have extensive rights to service in Swedish, even though this might not always hold up in practice.

Swedish in Finland is often referred to as a minority language, even though it is a national language with the same legal status as the majority language Finnish. However, Swedish is spoken by a minority, and is in many aspects comparable to other minority languages in Europe. As previously mentioned, the number of registered Swedish speakers is about 290,000, but the number of people with knowledge of Swedish is much higher. In Finland, a person can register only one mother tongue, which means that a significant amount of people are registered as Finnish speakers, but still speak Swedish. They may be bilingual by birth or have married into a bilingual family. It is difficult to get absolute numbers on the home languages, but Saarela (Citation2021, p. 42) shows that about one third of the adult Swedish-speakers have a Finnish-speaking partner. In addition, two thirds of the children in Finnish-Swedish bilingual families are registered as Swedish speakers, meaning that for one third the registered mother tongue is Finnish, even though they most likely also speak Swedish (Saarela, Citation2021, p. 45). On some level though, all Finns know both Finnish and Swedish, since the national languages are compulsory subjects in schools.

Mostly, Swedish speakers are located along the western and southern coastline, with historically tight connections to Sweden. With the exception for the Åland islands, most of the municipalities are bilingual. However, the language situation differs considerably between different areas. Larger cities, like the capital Helsinki and for example Turku, are multilingual, but dominated by Finnish. In these areas, a majority of the Swedish speakers are bilingual. In rural areas or smaller towns, on the other hand, Swedish may be the local majority language and the number of bilinguals is much smaller (Saarela, Citation2021, p. 43).

One crucial factor for maintaining the Swedish language vitality in Finland is the school system. The language of instruction is either Finnish or Swedish, and it is possible to attend schools on all levels in Swedish, from basic education to the university level. As previously mentioned, both national languages are compulsory subjects in the curriculum (Kumpulainen, Citation2018; see also Björklund & Suni, Citation2000). In Finnish schools, most students study Swedish from the sixth grade, whereas in many Swedish schools Finnish is studied already from the first grade, by nearly 90% of the pupils (Finnish National Agency for Education, Citation2019). The attitudes towards Swedish among the Finnish-speaking population vary, and some argue that learning Swedish in school steals time away from other languages, for example English. According to Halonen et al. (Citation2015, p. 9), Swedish can be seen as a window towards Scandinavia or as a ‘historical relic which enjoys undeserved privileges’. They conclude:

Language disputes have occurred every now and then: the representatives of the Swedish-speakers tend to appeal to the constitutional principle of equality when defending the status quo; much of the political elite defends the adopted language policy line; and some Finnish nationalists and populists call for the removal of the equality between the languages and the teaching of Swedish as an obligatory language. (Halonen et al., Citation2015, p. 9)

Even though scholars raise concerns about the dominance of English, its popularity is evident. Both Finnish and Swedish pupils study English in school, and it is the single most popular foreign language. Hence, most adolescents in Finland have at least basic language skills in three languages (Finnish National Agency for Education, Citation2019). Regrettably, for an increasing number of students English is also the only foreign language studied (beside the second national language) and the interest for other foreign languages has diminished. According to the Finnish National Agency for Education (Citation2019), the popularity of English is partly due to its status in global communication, and ‘the narrowing language repertoire of Finns has become a matter of concern’ (p. 1).

English is also the dominant digital language (Peterson, Citation2019; Stenberg-Sirén, Citation2020; Vincze & Joyce, Citation2017; Vincze & Moring, Citation2018) and an inseparable part of especially young people’s lives, according to Peterson (Citation2019):

In fact, this ease with English makes some of these younger speakers a bit difficult to classify in terms of their status with English; they are usually not mother-tongue speakers because they haven’t grown up speaking English at home. At the same time, they are not really foreign speakers of English either, as English imbues their daily existence and has done so for nearly their entire life. Many have reached a level of proficiency that equates to nativeness. (Peterson, Citation2019, p. 6)

In this study, we focus on the linguistic trio Swedish, Finnish and English, and how adolescents position themselves towards the three languages. In general, Swedish-speaking people have a higher proficiency in Finnish than Finnish-speaking people in Swedish. Therefore, we conducted the study among Swedish-speaking adolescents living in the bilingual (multilingual) capital region.

The present study

Ethnolinguistic identity theory (ELIT) (e.g. Giles & Johnson, Citation1987; Reid et al., Citation2004) asserts that identity management depends on an interplay of some contextual factors. Specifically, when people identify strongly with their ingroup relative to the outgroup, perceive the boundaries between their ingroup and the outgroup to be hard (i.e. it is difficult to switch linguistic group membership) and perceive the vitality of the ingroup language to be high compared to that of the outgroup, they typically strive to strengthen the social position of their ingroup, if necessary, even via direct confrontation with the outgroup. This strategy is called ethnolinguistic competition.

On the other hand, when individuals identify weakly with their ingroup relative to the outgroup, perceive that the boundaries between their ingroup and outgroup are soft (i.e. switching ethnolinguistic group membership is possible), and perceive the vitality of the ingroup language to be low compared to that of the outgroup, they attempt to leave their ingroup and join the outgroup. This strategy is called ethnolinguistic mobility. Finally, a third strategy, ethnolinguistic creativity can occur in cases where ingroup identities are strong, boundaries are hard and the relative vitality of the ingroup is perceived to be moderate.

The focus of the present study is to address how individuals living in a bilingual society perceive English as a third language and how they manage their disposition towards English in such a linguistic triad. Although our starting point is to contextualise this question within the framework of ELIT, it is vital to note that some accommodation and modifications are necessary. On the one hand, ethnolinguistic identity theory, and its core, social identity theory (SIT) (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979, Citation1986), tends to locate identity management typically in a dichotomised intergroup context, where a single ingroup is contrasted with a single outgroup. Clearly, approaching contexts with more than two languages (Swedish, Finnish and English) is less straightforward from this theoretical angle. In addition, as English is spoken in many different countries, cultures and contexts, it is not possible to define a sole speaking community, which can be considered as a meaningful linguistic outgroup. On the other hand, identification according to SIT is generally defined as group memberships, whereas identity management as intentions to manage group memberships to reach a more positive self-esteem, which makes ELIT a good theoretical starting point. Consequently, while we build upon ELIT to examine individuals’ disposition towards English as a third language, we take considerable liberty when using some of the concepts of the theory. Instead of referring to mobility and competition as identity management strategies, which describe managing one’s disposition regarding group membership (e.g. the linguistic ingroup(s)), we refer rather to disposition towards English, with mobilising efforts towards English describing the intention to promote and enhance the advancement of English. In a similar vein, by competitive efforts against English we mean the intention to block and hinder the advancement of English. Finally, replacing intergroup boundary, which has been widely used to assess how difficult it is to shift group membership, we introduce the concept of interlanguage boundary to gauge how difficult it is to shift language.

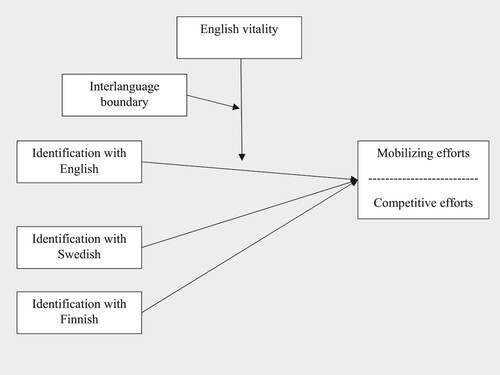

Against this background, the focus of the present study is on the combined effect of linguistic identification, interlanguage boundary and ethnolinguistic vitality on mobilising efforts towards English, and competitive efforts against English. In particular, we expect that strong identification with English, the perception of high English vitality and soft boundaries (i.e. the easiness of a shift towards English) will predict mobilising efforts, that is, the motivation to enhance and promote the advancement of English. Simultaneously, we expect that weak identification with English, the perception of low English vitality and hard boundaries (i.e. the difficulty of a shift towards English) will lead to competitive efforts, that is, the motivation to block and hinder the advancement of English. Additionally and importantly, we examine how these effects depend on identification with the national languages of the country, Swedish and Finnish. The conceptual model we test is depicted in .

Figure 1. The conceptual model (for schematic presentation of the model, see Hayes, Citation2017, p. 331).

Method

Participants

As noted above, we examine the disposition towards English among young Swedish-speaking Finns. Self-administered questionnaire data was collected in two Swedish-language secondary schools in southern Finland (N = 299). Research permission had been granted from the two municipalities in question, and participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous. In addition, information about the study including contact information to one of the researchers (Vincze) was sent to the parents. Since the participants were over the age of 15, the study was conducted in schools, and the answers to the questionnaire were completely anonymous, no separate approval from the University of Helsinki’s ethics board was required. About 60% of the participants were female, 39% male and 1% other. The average age was approximately 17 years (M = 16.98, SD = .83).

Measures

Disposition towards English. Mobilising and competitive efforts were measured with items concerning English on both an individual and a societal level. To assess mobilising efforts towards English, three 5-point items were developed (e.g. ‘I would like to use English as my first language in all my life’; ‘I would be happy if English was introduced as an official language in Finland’). Competitive efforts against English were also measured with three items (e.g. ‘Finland should invest more in its own language to withstand global English’; ‘Finland should reduce the influence of English in the country to preserve its own language’). Higher scores indicated greater endorsement of the given disposition towards English. The reliability of the measures of both mobilising efforts (α = .78) and competitive efforts (α = .64) was acceptable.

Ethnolinguistic identification. Identification with English, Swedish and Finnish was assessed with four 5-point items, respectively. The items were selected in order to measure analogous aspects of ethnolinguistic identification and the four items were the same for all three languages. Concerning English, items were e.g. ‘English is an important part of my identity’ and ‘I have a lot in common with English speakers’. Higher scores mean higher identification with the given language. The reliability of the scales was good (for English α = .83, for Swedish α = .82 and for Finnish α = .88).

English vitality. The perceived vitality of English was measured with seven 7-point items from the subjective vitality questionnaire (Bourhis et al., Citation1981). The items were selected with the situation of English in Finland in mind so that they assessed meaningful aspects of the social strength of English in a, by default, non-English-speaking context. Sample items were ‘How highly regarded is English in Finland?’; ‘How well-represented is English in the media in Finland?’ and ‘How well-represented is English in the business life in Finland?’ Higher scores demonstrate higher perceived vitality. The reliability of the measure was acceptable (α = .65).

Interlanguage boundary. A single 5-point item was used to assess the hardness/softness of the interlanguage boundary (‘In principle, it would not be difficult for Finns to shift language to English’).

Results

A one-way within subjects’ analysis of variance demonstrated that participants identified most highly with Swedish (M = 4.25, SD = .68), next with Finnish (M = 3.34, SD = .94), and least with English (M = 2.83, SD = .87), F(2, 552) = 231.35, p < .001, η2 = 46. All pairwise comparisons were statistically significant (p < .001).

Means, standard deviations and correlations for the study variables are presented in . Most importantly, competitive efforts against English were significantly related only to identification with Finnish and to mobilising efforts towards English but not to identification with English, English vitality or interlanguage boundary. At the same time, mobilising efforts towards English were significantly related to identification with Finnish, identification with English and interlanguage boundary but not to English vitality. Remarkably, identification with English was significantly and positively related to identification with Swedish but not related to identification with Finnish.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations and zero-order correlations among study variables.

The model was tested by means of a moderated moderation using Mplus 8.4 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998−Citation2019). Mobilising efforts and competitive efforts were dependent variables, identification with English, English vitality and interlanguage boundary were entered as independent variables, whereas identification with Finnish was added as a control variable. As identification with Swedish was not significantly related to either dependent variable, it was not included in the model. The model was saturated; the fit for the baseline model was significant, χ2(17) = 146.73, p < .001.

With respect to competitive efforts against English, the model explained 9% of the variance in the dependent variable, R2 = .09. Neither the main effects, nor the two-way or the three-way interactions were significant. The only significant predictor was identification with Finnish, B = .23, p < .001, indicating that higher identification with Finnish increases competitive efforts.

With respect to mobilising efforts, the model explained 35% of the variance in the dependent variable, R2 = .35. Identification with English had a significant main effect, B = .50, p < .001, showing that stronger identification with English leads to greater endorsement in mobilising efforts towards English. Interlanguage boundary was marginally significant, B = .10, p = .054, suggesting that those who perceive the boundary to be softer endorse mobilising efforts more. English vitality was not significant, B = -.09, p = .08. None of the two-way interactions were statistically significant, but the three-way interaction was significant, B = .09, p < .05. In addition, identification with Finnish had a significant impact, B = -.19, p < .001, demonstrating that higher identification with Finnish decreases mobilising efforts.

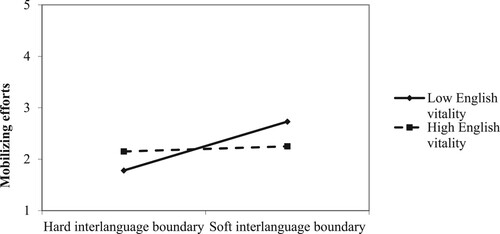

To further elaborate on the significant three-way interaction, the data was mean split based on identification with English, and subgroup analyses were performed among low English identifiers and high English identifiers. Among high English identifiers, the interaction between vitality and interlanguage boundary was not statistically significant, B = .14, p = .21; in addition, neither vitality nor boundary had significant main effects on mobilising efforts. However, the interaction between vitality and interlanguage boundary was significant among low English identifiers, B = .20, p < .05. This two-way interaction is depicted in . As can be seen, when English vitality is perceived to be high, boundary has no effect on mobilising efforts towards English, B = .03, p = .69. This means that for individuals, who do not identify strongly with English but find that English vitality is high, the mobilising efforts are independent of how hard the interlanguage boundary is perceived to be. However, when English vitality is perceived to be low, those who perceive the boundaries to be soft appear more likely to endorse mobilising efforts than those who perceive the boundary to be hard, B = .32, p < .01.

Discussion

Adapting the concepts of ethnolinguistic identity theory, the present paper examined the interactive effects of identification with English, interlanguage boundaries, and the perceived ethnolinguistic vitality of English on competitive efforts against English and mobilising efforts towards English, among young Swedish-speaking Finns. The effects were contrasted to identification with the national majority language Finnish and the less spoken national language Swedish.

The results provided mixed support for our expectations. Competitive efforts against English (i.e. the intention to block and hinder the advancement of English) were not affected by identification with English, interlanguage boundary or the perceived vitality of English in Finland. Instead, competitive efforts were a sole consequence of identification with Finnish: participants who identified stronger with Finnish were more engaged to stop English and enhance the position of the national languages against English.

Concerning mobilising efforts towards English (i.e. the intention to promote and enhance the advancement of English), the pattern of findings seems to fit more smoothly with the assumptions in ELIT. Indeed, mobilising efforts were based on an interplay between identification with English, the perceived vitality of English and interlanguage boundary. Among high English identifiers, mobilising efforts did not depend on vitality or interlanguage boundary, whereas among low English identifiers, interlanguage boundary predicted mobilising efforts only among those who perceived the vitality of English to be low. That said, the results suggest that among low English identifiers it suffices one additional condition to be met, a perception of high English vitality or soft interlanguage boundary, for individuals to engage in mobilising efforts. Furthermore, and of note, identification with Finnish was also an important predictor of mobilising efforts: participants who identified stronger with Finnish were less engaged to support the advancement of English.

Taken together, the findings presented here have several implications. Mobilising efforts towards English were significantly related to several of the measured variables, while competitive efforts against English were significantly related only to identification with Finnish. Our results indicate that greater endorsement in mobilising efforts towards English is related to a stronger identification with English and, to a lesser extent, to the perception that the boundary between languages is soft rather than hard. As mobilising efforts were measured as a positive attitude towards the use of English on both an individual and a societal level, these results seem to support earlier studies showing that identification with a language is strongly associated with the use of that language. However, it has also been found that a positive attitude towards a language and the use of that language does not necessarily correlate with identification with the language (for a discussion on the relationship between identity and language see e.g. Henning-Lindblom & Liebkind, Citation2007). According to the present study, mobilising efforts among low English identifiers were found only if the respondents found the vitality of English to be high, or the group boundary to be soft. This in turn could be interpreted more as a will to promote English because of the perception of the language’s strong position in society, rather than as something related to the respondent’s linguistic identity.

Whereas mobilising efforts towards English were related to several of the measured variables, competitive efforts against English were significantly related only to identification with Finnish. In other words, the measured variables in relation to English could not explain the competitive efforts and did not support our expectations. This result suggests that it is not the disposition towards English per se that is connected to a more negative view on English, but instead the identification with the national majority language Finnish. The correlation between the competitive efforts and identification with the minority language Swedish was not significant, meaning that the identification with the majority language is in a crucial position in this regard. Since the model does not explicitly explain this result, it is something that needs to be studied further. We find there is a need for deeper exploration of these language group identifications, especially the Finnish and the English ones, to gain a greater understanding of to what extent they are seen as additive and multiple or perhaps in some way seen as subtractive by the respondents. Are there for example differences in the core values associated with these different identities, which make them in some way perceived as oppositional?

However, one can perhaps assume that high identification with the majority language Finnish may indicate a higher level of integration and connectedness in a society that mainly functions in Finnish, and therefore predicts a willingness to resist the influence of English, whereas people with low identification with Finnish might be more open to the world language English. As previously noted, identification with English was not related to identification with Finnish, whereas it was significantly and positively related to identification with Swedish. For young people who identify mainly with Swedish, English might seem like a way out – out of the country or out of complex communication contexts with majority speakers – and they might therefore be more welcoming towards English in Finland. There are reported examples of Swedish speakers and Finnish speakers using English in communication with each other (Stenberg-Sirén, Citation2020), which of course bilinguals have no need for. Swedish and English are also typologically closer to each other, sharing many features, and studies show that Swedish-speaking Finns have a more positive attitude towards English loan words, compared to Finnish speakers (Mattfolk, Citation2005). Furthermore, the Swedish-speaking population has a history of being internationally orientated, having a three times higher international migration rate than the Finnish-speaking population (Saarela & Finnäs, Citation2013).

The suggestion of an opposition between the local majority language Finnish and the global language English is intriguing. When living in a bilingual society you are used to having several languages around you, and actively opposing a language might seem farfetched. In addition, English is everywhere all the time, in education, the media, the linguistic landscapes, business, academia, and in social interaction with people not speaking the national languages. In other words, even though one might see the risks of English ‘taking over’, the idea of opposing it might seem futile. One must also consider the general attitudes towards language acquisition, where being competent in several languages is considered a virtue. Why is it then that the competitive efforts could be seen at all, and why are they in connection to a strong identification with Finnish? One possible explanation might be that the general societal discussion about the threat of English has mainly taken place in Finnish-language media, for example in the largest Finnish newspaper Helsingin Sanomat (Hiilamo & Paakkanen, Citation2018). This is the first time in modern times that Finnish is potentially threatened by another language in certain contexts (Finnish language board, Citation2018), whereas Swedish, as the less spoken national language, is constantly overshadowed by Finnish. Another explanation might be the perceived association between language and a sense of nationalism (e.g. Blommaert & Verschueren, Citation1992), and that those respondents who identify stronger with Finnish perhaps therefore have a more negative view on English. Those who identify with both national languages might not see the need for English, in a way that those who do not identify strongly with Finnish might.

Considering the positive correlation between identification with Swedish and English, and the correlation between identification with Finnish and competitive efforts towards English, perhaps English actually can be considered a threat – not to Swedish, but to Finnish. This could be a sign of the two opposing processes of grouping and contrasting in identity negotiation (Ehala, Citation2017, p. 130−133), as Swedish speakers choose between two majority language groups. In other words, Finnish and English seem to fit better into the traditional ingroup language versus outgroup language opposites, than the distinction between Swedish and English. In consequence, for minority language speakers, association with one majority language might seem enough. Ehala (Citation2010, p. 208) states: ‘In a sense, the stronger, more prestigious, more powerful and more culturally attractive the outgroup is perceived to be in comparison with the ingroup, the stronger the motivation to be associated with the outgroup’. The same comparison can be made between two different outgroups, who are both in a strong position in comparison with the ingroup. In this case, those who identify strongly with Finnish show resistance towards English, whereas those who do not identify strongly with the national majority language might feel more inclined towards the world language English. In this sense, three really is a crowd.

We acknowledge that the paper at hand has some shortcomings and limitations. Although we believe that the reconceptualisation of identity management strategies (mobility and competition) and intergroup boundary for the purposes of the particular research was beneficial, these are new concepts that need to be tested and validated. Relatedly, while we carefully selected items from the subjective vitality questionnaire to measure the vitality of English in Finland, we did not assess the vitality of Swedish and Finnish. In fact, we believe that the vitality of the three languages cannot be assessed using the same scale, since their positions in the country are so different. However, in going forward with this line of study, it would be important to include relevant and meaningful measurements of the vitality of the national languages as well. Finally, the use of a student sample, admittedly, limits the generalisability of the findings. Young people typically use English extensively via social media and they may have a closer relationship with English than the older generations. It is likely that different conclusions could be drawn if the research was conducted within another age group. Similarly, we would probably reach a different outcome, if the study was conducted in rural areas with a higher share of Swedish-speaking people.

Notwithstanding these drawbacks, we hope the findings presented here are valuable and thought-provoking. The advance of global English has been a common phenomenon around the world. Therefore, it would be worthwhile to situate the questions advanced here in other countries and cultures to examine the consequences of linguistic globalisation for the retention of national languages and linguistic diversity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Björklund, S., & Suni, I. (2000). The role of English as L3 in a Swedish immersion programme in Finland: Impacts on language teaching and language relations. In J. Cenoz, & U. Jessner (Eds.), English in Europe: The Acquisition of a third language (pp. 198–221). Multilingual Matters.

- Blommaert, J., & Verschueren, J. (1992). The role of language in European nationalist ideologies. Pragmatics, 2(3), 355−375. https://doi.org/10.1075/prag.2.3.13blo

- Bourhis, R. Y., Giles, H., & Rosenthal, D. (1981). Notes on the construction of a ‘subjective vitality questionnaire’ for ethnolinguistic groups. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 2(2), 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.1981.9994047

- Cenoz, J., & Jessner, U. (2000). English in Europe: The Acquisition of a third language. Multilingual Matters.

- Ehala, M. (2010). Ethnolinguistic vitality and intergroup processes. Multilingua, 29(2), 203–221. https://doi.org/10.1515/mult.2010.009

- Ehala, M. (2017). Signs of identity. Routledge.

- Finnish government. (2020). https://valtioneuvosto.fi/sv/-/1410853/oikeusministerio-kutsuu-mukaan-uuden-kansalliskielistrategian-valmistelutyohon

- Finnish language board. (2018). Finland urgently needs a national language policy program (author’s translation). Statement from the Finnish language board 26.10.2018. https://www.kotus.fi/ohjeet/suomen_kielen_lautakunnan_suosituksia/kannanotot/suomi_tarvitsee_pikaisesti_kansallisen_kielipoliittisen_ohjelman

- Finnish National Agency for Education. (2019). Facts express, 1c/2019. Retrieved August 9, 2021, from https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/factsexpress1c_2019.pdf

- Giles, H., & Johnson, P. (1987). Ethnolinguistic identity theory: A social psychological approach to language maintenance. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 1987(68), 69–100. https://doi-org.libproxy.helsinki.fi/10.1515/ijsl.1987.68.69

- Halonen, M., Ihalainen, P., & Saarinen, T. (2015). Diverse discourses in time and space: Historical, discourse analytical and ethnographic approaches to multi-sited language policy discourse. In M. Halonen, P. Ihalainen, & T. Saarinen (Eds.), Language policies in Finland and Sweden. Interdisciplinary and multi-sited comparisons (pp. 3–26). Multilingual Matters.

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis, second edition: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications.

- Heimonen, E., & Ylönen, S. (2017). Monikielisyys vai “English only”? Yliopistojen henkilökunnan asenteet eri kielten käyttöä kohtaan akateemisessa ympäristössä. In S. Latomaa, E. Luukka, & N. Lilja (Eds.), Kielitietoisuus eri-arvoistuvassa yhteiskunnassa – language awareness in an increasingly unequal society (pp. 72–91). AFinLAn vuosikirja.

- Henning-Lindblom, A., & Liebkind, K. (2007). Objective ethnolinguistic vitality and identity among Swedish-speaking youth. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 2007(187-188), 161–183. https://doi-org.libproxy.helsinki.fi/10.1515/IJSL.2007.054

- Hiilamo, E.-A., & Paakkanen, M. (2018). Poikkeuksellinen kannanotto: “Suomen ja ruotsin kielen asema uhattuna”. (Exceptional statement: “The position of Finnish and Swedish threatened”, author’s translation). Helsingin Sanomat. https://www.hs.fi/kulttuuri/art-2000005877448.html

- Hoffman, C. (2000). The spread of English and the growth of multilingualism with English in Europe. In J. Cenoz, & U. Jessner (Eds.), English in Europe: The Acquisition of a third language (pp. 1–21). Multilingual Matters.

- Kumpulainen, T. (2018). Key Figures on Early Childhood and Basic Education in Finland. Finnish National Agency for Education. Reports and surveys 2018:3. https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/key-figures-on-early-childhood-and-basic-education-in-finland.pdf

- Leppänen, S., & Nikula, T. (2008). Johdanto. In S. Leppänen, T. Nikula, & L. Kääntä (Eds.), Kolmas kotimainen − lähikuvia englannin käytöstä suomessa, (pp. 9–40). Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden Seura.

- Mattfolk, L. (2005). Investigating attitudes to ʻordinary spoken language': Reliability and subjective understandings. In T. Kristiansen, P. Garrett, & N. Coupland (Eds.), Subjective processes in language variation and change (pp. 171–191). Acta Linguistica Hafniensia 37. Reitzel.

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998−2019). Mplus user’s guide. Eighth edition. Muthén & Muthén.

- Peterson, E. (2019). Making sense of “Bad English": An introduction to language attitudes and ideologies. Taylor & Francis Group (Routledge).

- Reid, S. A., Giles, H., & Abrams, J. R. (2004). A social identity model of media usage and effects. Zeitschrift für Medienpsychologie, 16(N.F. 4), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1026/1617-6383.16.1.17

- Saarela, J. (2021). Finlandssvenskarna 2021 – en statistisk rapport. Svenska Finlands Folkting. Retrieved 11 August, 2021, from https://folktinget.fi/Site/Data/1597/Files/Finlandssvenskarna%202021_statistisk%20rapport_Folktinget_KLAR.pdf

- Saarela, J., & Finnäs, F. (2013). The international family migration of Swedish-speaking Finns: The role of spousal education. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 39(3), 391–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2013.733860

- Spring, J. (2007). The triumph of the industrial-consumer paradigm and English as the global language. International Multilingual Research Journal, 1(2), 61–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313150701489655

- Statistics Finland. (2021a). Population according to language 1980–2020. Updated 31.3.2021. Retrieved 17 May, 2021, from https://www.stat.fi/til/vaerak/2020/vaerak_2020_2021-03-31_tau_002_en.html

- Statistics Finland. (2021b). Foreign-language speakers. Retrieved 11 August, 2021, from https://www.stat.fi/tup/maahanmuutto/maahanmuuttajat-vaestossa/vieraskieliset_en.html

- Stenberg-Sirén, J. (2020). Svenska, finska, engelska – komplement eller alternativ? (Swedish, Finnish, English – complement or alternative? Author’s translation). Magmarapport 1/2020. http://magma.fi/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/magma1_2020_webb-1.pdf

- Taavitsainen, I., & Pahta, P. (2003). English in Finland: Globalisation, language awareness and questions of identity. English Today, 19(4), 3. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266078403004024

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin, & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole.

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behaviour. In S. Worchel, & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Nelson Hall.

- Vincze, L., & Joyce, N. (2018). Online contact, face-to-face contact, and multi-lingualism: Young Swedish-speaking Finns develop trilingual identities. Communication Studies, 69(1), 85–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2017.1413410

- Vincze, L., & Moring, T. (2017). Trilingual internet use, identity, and acculturation among young minority language speakers: Some data from transylvania and Finland. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, European and Regional Studies, 12(1), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1515/auseur-2017-0010