ABSTRACT

Educational actions that establish connections between language, culture, and power construct ideologies of languages and their speakers. The study of linguistic landscapes in education (i.e. schoolscapes) offers a lens to analyse the material manifestation of such ideologies. As a venture in participatory research, this paper investigates how young learners construct and represent their schoolscapes while documenting and interpreting them in video projects. We bring data from projects carried out with the Moldavian Csángó in Romania as well as Finnish and Swedish speaking Finns in Finland. In both cases, young people learning in multilingual educational contexts were engaged in video projects. In this way, the authors have introduced participants’ self-recorded videos to their research practice to gain materials which are less influenced by researchers. We present examples of traditional, i.e. one-angle-at-a-time and 360° videography projects and discuss their suitability for collaborative projects that investigate multilingual practices, including the use of minoritised languages. The qualitative analysis of grassroots literacy and oral interaction in the videos indicates that participatory projects offer considerable advances to schoolscape research in collaboratively studying the moment-to-moment nature of language practices and the related language ideologies in and across multilingual spaces.

1. Introduction

Our engagement with participatory research stems from sociolinguistic research exploring how people's language ideologies have been manifested in the linguistic landscapes of their (educational) surroundings. In our recent projects (e.g. Szabó & Troyer, Citation2017), we have turned towards participatory methods (see Bodó et al., Citation2022), where research is co-designed and conducted jointly with participants.

This methodological paper aims to share insights about good practices, challenges, and potentials of the use of videographic methods in participatory research with young learners in multilingual educational contexts. For the sake of contextual diversity and methodological robustness, we investigate two different empirical contexts. Our guiding analytical question is how young learners construct and represent schoolscapes they inhabit and use for learning while documenting and interpreting them in participatory videographic projects. We base our discussion on two projects in multilingual educational environments, which include the use of minoritised languages and contested vernaculars. Both projects followed the theoretical framework of schoolscape studies in combination with inclusive ethnography (e.g. Nind, Citation2014; Szabó & Troyer, Citation2017) and co-designed research (e.g. King et al., Citation2022) to formulate our research questions. Building shared interest with the partner institutions and participants, the collaboratively defined societal aim of these projects has been to develop learning environments that foster multilingualism. In this paper, we analyse two case studies to discuss how young learners’ self-recorded videos contributed to this societal aim and how the lessons learnt from the videography projects advance schoolscape studies. From the point of view of participatory research, we explore how co-created videos open space for participants’ needs to take part in meaningful activities, and researcher's aims to gain analysable data.

2. Understanding learning environments through a schoolscape lens

Educational actions that establish connections between language, culture, and power construct ideologies of national, minoritised and other languages, and their speakers (From, Citation2020a; cf. Brown, Citation2012). In this paper, we approach the material manifestation of such conceptualisations through the lens of schoolscape research which we define as a branch of linguistic landscape research in educational settings (Brown, Citation2005, Citation2012; Gorter & Cenoz, Citation2022; Krompák et al., Citation2022; Laihonen & Szabó, Citation2018).

Although practically any space can equally serve as a site of teaching and learning (cf. Malinowski et al., Citation2020; Niedt & Seals, Citation2021), custom-designed learning environments of institutionalised education, such as day-care, school and university premises as well as purposefully organised campus-external activities, deserve special attention in schoolscape studies (Krompák et al., Citation2022; Laihonen & Szabó, Citation2018). Investigating varied and functional uses of language in educational settings (Brown, Citation2005), and analysing the materiality of education with a multisensory approach, schoolscape studies follow two main directions that are often interlinked: (1) what affordances the environment offers for learning and (2) how people interpret and conceptualise the linguistic landscapes that they inhabit and use for learning (Gorter & Cenoz, Citation2022). To break down these into specific settings, schoolscape studies cover a variety of topics including the fostering of multilingualism and language revitalisation (Harris et al., Citation2022; Menken et al., Citation2018); material resources for bilingual and immersion education (Jakonen, Citation2018); temporality (Ayae & Savski, Citation2023; Brown, Citation2018) as well as the complexity and ecology of the linguistic landscapes of learning (Szabó & Dufva, Citation2021). This richness of topics is especially central for multilingual communities, including speakers of minoritised languages, because through constituting, reproducing, and transforming language ideologies (Brown, Citation2012), schoolscapes can encourage or discourage the use of certain languages. On the one hand, the display of signs containing texts in minoritised languages, or material references to marginalised cultures, contribute to the creation of comfortable and safe spaces (sometimes termed ‘shelters’, ‘oases’ or ‘nests’; cf. Brown, Citation2018) for the identity work and literacy practices of minoritised languages. On the other hand, ideological erasure makes marginalised languages and cultures invisible and constitute a hidden curriculum that emphasises linguistic homogenisation and the hegemony of a national language and culture (cf. Irvine & Gal, Citation2009). Further, schoolscape studies analyse communication in and through various media as well as spatial and temporal arrangements that manifest societal constructions of social difference, norms, competences, ownership, and boundaries in education, often pointing to disputed power relations and tensions of various groups of speakers (Brown, Citation2018; From, Citation2020a; Menken et al., Citation2018). Our objective in this paper is to investigate the emergence of such societal constructions by asking how young learners construct and represent schoolscapes they inhabit and use for learning while documenting and interpreting them in participatory videographic projects.

3. Exploring researcher and participant representations of the schoolscape through videographic methods

3.1. Review of methodologies

Considering the multisensory approach and the learner perspective as their points of departure, schoolscape studies offer a fertile ground for multimodal methodologies that explore and reflect on multilingual learning environments. Traditionally, visual methods have been used to generate multimodal data to minimise the impact that researchers have in shaping the data (e.g. Pitkänen-Huhta & Pietikäinen, Citation2016). Moreover, in visually oriented research projects, participants’ voices and agency are supposed to become foregrounded in the research narrative, too. For example, in his venture in Cultural Geography on children's experiences of place, Hart (Citation1979) involved children in various visual methods such as photographing, mapping and sandbox scale modelling of some chosen sites relevant for them. Faulstich Orellana (Citation1999) in turn studied photography and drawings by children in her ethnographic study of childhood in diverse communities. Further, Clark (Citation2010) applied visual ethnographic methods including children's drawings and photos in an intervention of learning environment design for early childhood education. Contributions in Christensen and James (Citation2017) demonstrate that visual methods in general and a wide range of digital technologies in particular have accelerated a shift in childhood research from research on children to research with children and ultimately towards research by children.

In several participatory projects, the engagement of participants has been achieved through co-designing the research process with them, as well as including their feedback and assessment of the project and its results (Facer & Enright, Citation2016). We argue that the use of digital technology further helps to engage the participants; however, the technicised fieldwork experience brings new challenges and calls for more critical ways to reflect on the processes of representing and analysing schoolscapes. We also acknowledge that participants often face constraints in their contribution as they act within a certain framework defined by the overall research interest set by researchers and they also need to navigate in the complexities of value choices and power dynamics of their respective institutions (e.g. Ozer et al., Citation2013).

Troyer and Szabó (Citation2017) set a framework of videographic methods in linguistic landscape studies, distinguishing between non-participatory and participatory approaches. In non-participatory videography, the researchers keep their attention on the landscape and use the footage to visually support their representation and interpretation of it. Participatory videography in turn shifts focus on the people inhabiting the linguistic landscape, including their actions and reactions to the environment.

Participatory videography can be either researcher- or participant-recorded, the latter giving space not only for the (verbal) reactions of participants but also for their ways of framing, capturing, and editing – in brief, visually representing the landscape. One of the benefits of videography is that it makes the temporal aspects of interaction-in-the-linguistic-landscape visible and thus makes processes of capturing and representing the landscape analysable (Troyer & Szabó, Citation2017). For example, Bradley and colleagues (Citation2018) investigated how elementary and secondary students combined photography, video and interviews to create their own representation and interpretation of the multilingual urban environment they inhabited. At the same time, the media the students produced offers rich documentation of their process of exploring and analysing the landscape through various stages and methods.

3.2. Our methodological pathway

In this section, we reflect on our own research paths to explicate our position in the field. We both arrive from an audio recording-centred tradition of applied Conversation Analysis (ten Have, Citation2004) in which social meaning making is mainly analysed as verbal interaction. Incorporating Linguistic Landscape analysis to our work, our understanding of social interaction has moved towards multimodal semiotics (e.g. Scollon & Wong Scollon, Citation2003); in this way, we analyse multimodal interaction in the linguistic landscape. Adapting walking-based interview methodologies such as the tourist guide technique (Szabó, Citation2015; Szabó & Troyer, Citation2017), Szabó co-explored the schoolscape together with research participants. This methodological solution made fieldwork a collaborative venture with people who inhabit schoolscapes and meant a shift from researcher-led projects in which researchers take and select photos and video excerpts to use them as triggers for interviews (e.g. Dressler, Citation2015; Harris et al., Citation2022). However, having learnt how significantly the researcher co-constructs the data during walking interview settings (Szabó & Troyer, Citation2017), we have introduced participants’ self-recorded videos to gain data to which researchers have not contributed directly during the recording process. This innovation was aimed at enhancing the development of participants’ awareness of their material environments. It was also thought to bring participants’ own video-mediated viewpoints to the multimodal research materials in a more direct and hence forceful manner. As the think-aloud method applied by De Wilde and colleagues (Citation2022) demonstrates, students construct their own representations of the linguistic landscape while exploring it. Thus, the research is built on participants’ footage, through which they pre-select certain objects and topics (and deselect others) for focus. Consequently, participants more significantly shape the analysis than in projects in which researchers (co-)produce data. At the same time, we recognise that participants produced video data upon our request in the framework of our research interests and in their given educational contexts, which restricted their choices. Further, their video recordings became data in the entextualisation practices of our research process in general and our ways of data representation in particular (cf. Park & Bucholtz, Citation2009).

3.3. Building participatory video projects with communities

Building on the above considerations, we investigate how two videographic data generation methods enable and/or constrain collaboration with participants in research on multilingual schoolscapes. That is, we discuss some of the challenges and possibilities of traditional videos that feature one angle on the site at a time as compared to 360° videos that offer a hemispheric view of the site and make it possible to choose among alternative angles from which to look at the site. We elaborate on two cases where young learners as participants in schoolscape projects self-recorded their project work. Through these cases, we discuss the role of videography in different technological and societal contexts; that is, we present traditional videography by Moldavian Csángó youth taking part in a Hungarian language revitalisation programme in Romania, and 360° videography by Finnish and Swedish speaking Finns studying in a co-located campus of two monolingual upper secondary schools with either Finnish or Swedish being their language of instruction in Finland.

The same overall design was applied in both contexts. We have conducted projects including short (between one week to one month) fieldwork periods with young people and their teachers, applying the principles of so-called rapid-focused ethnography (Ackerman et al., Citation2015). That is, we focused on specific activities during each period on site to further our ethnographic study (e.g. negotiating collaboration; generating data; facilitating student-led videographic projects, etc.). In collaboration with the involved institutions, we have jointly formulated the research focus, recruited key participants (volunteering young learners and teachers), and generated data by multiple mediated techniques during our visits.

We invited school communities to collaborate in strengthening awareness and deepening understanding of the importance of the physical environment in learning and teaching. Our goal was also to help teachers and learners conceptualise the schoolscape as a resource for multilingual educational purposes. Further, we have aimed at a renewal of data generation techniques to ensure an emic and collaborative understanding of the schoolscape. While negotiating the research agenda and methodological solutions with the involved school communities, we targeted mutually beneficial collaborative projects by

creating activities participants and their educational institutions and communities find meaningful and purposeful from their own perspectives;

gaining analysable data so that researchers get insights into participants’ views and practices according to project-specific research questions; and

developing videographic data generation methods in multilingualism and schoolscape research to keep up with emerging communicative practices and technological development.

In our projects, we asked young people to present their schools and neighbourhood through videos that they recorded and edited. With examples from projects using traditional (one angle at a time) and 360° (hemispheric) videos in multilingual schoolscapes in rural Romania (Romanian, Hungarian and other languages) and urban Finland (Finnish, Swedish and other languages), we discuss how co-created videos open space for participants’ needs to take part in meaningful activities, and researcher's aims to gain analysable data.

In the analysis, we focus on metalinguistic expressions that reflect on the schoolscapes and their reconstruction through the student projects. On the basis of our experience in Conversation Analysis (ten Have, Citation2004), we employ interactional discourse analysis (cf. Rampton, Citation2001), taking into account the interactional context of the metalanguage we analyse, too.

In both projects reported here, we worked with the communities as community-external researchers. In Moldavia, Laihonen has been educated and is affiliated with a university in Finland (educated in Finnish with Swedish as a second language), has learned Hungarian at adult age, and has been engaged in research on the multilingualisms of Hungarian speaking minorities for two decades. Carina Fazakas-Timaru worked as a local fieldworker for Laihonen. She is a Moldavian born researcher with a native level proficiency in the Csángó way of speaking, standard Hungarian and Romanian, too. In Finland, Szabó contributed as an immigrant researcher from Hungary, educated in Hungarian, representing a Finnish university, holding methodological and theoretical knowledge on the investigated phenomenon. Szabó operated mainly in English at the time of fieldwork and acquired high level Finnish proficiency later. Szabó's fellow fieldworker from a domestic university, Tuuli From was educated in Finland in Finnish with high acquired proficiency in Swedish as well. All mentioned researchers have worked extensively on educational matters with a focus on language policies and emerging bi- and multilingual pedagogies.

4. Results from the two case studies

In the following sections, we showcase various ways in which participants produced video footage in our projects, and we also offer means for their analysis. We begin with traditional, one-angle-at-a-time videos applied in the research of Laihonen and then turn to the 360° video technology as used in Szabó's research.

4.1. Case 1: iMovie project in a Moldavian Csángó Community

Laihonen's examples come from his recent work with members of a special minority, the Moldavian Csángós. The Moldavian Csángós are an ethnically and linguistically heterogeneous group of Roman Catholics in North-Eastern Romania. An estimated 40,000 persons, one-fourth of the Catholic population in Moldavia, are bilingual in Romanian and the ‘Csángó way of speaking’ (a contested variety of Hungarian; see Bodó et al., Citation2017). The Csángó communities are in the final stages of language shift. Since 2000 very few adults use the vernacular in communication with their children (see Laihonen et al., Citation2020). The ‘archaic’ Csángó language and culture have been defined of special value in Europe by the Council of Europe (see REC, Citation2001); however, Csángó has not been recognised as a language by general reference sources. ‘Csángó’ has most often been classified as an ‘ancient’, i.e. authentic (see Gal, Citation2017, p. 233) dialect of Hungarian. Csángó does not have activists claiming for autonomous status as a language or attempts to standardise the Csángó ‘language’ are not known (see Laihonen et al., Citation2020 for details).

In 2001, the Moldavian Csángós were officially recognised as a minority culture by the Council of Europe (see REC, Citation2001), and the same year the teaching of Hungarian was launched in Moldavia. An educational programme with the goal of teaching Hungarian mother tongue among the Csángó operated in 2020 in c. 30 villages with c. 2000 children (Laihonen et al., Citation2020). Laihonen's research project focuses on the Moldavian Csángó Educational Program, where the children's Hungarian is revitalised, and they receive formal instruction in Hungarian literacy.

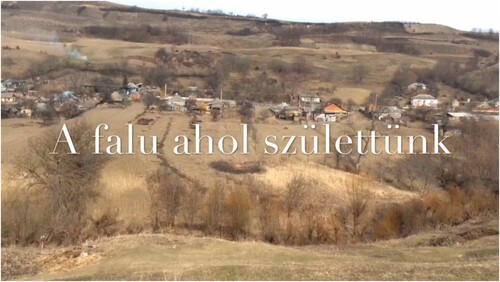

Our data is based on four one-month fieldwork trips by Laihonen and a local fieldworker Fazakas-Timaru in 2017–2019. In 2017, Laihonen co-designed different tasks with adolescents (aged 10–17) to document and reflect on their language practices. One of such tasks was making a video on their own village, using the iMovie application on iPads (). This task was completed in seven sites (villages), where 8–20 learners participated in this extracurricular project. They worked in groups and the project resulted in a total of 20 edited movies. Participation was voluntary, but practically almost all students of the Csángó Educational Program in that age group joined the project. In this task, the adolescents filmed significant places in the village together. Fazakas-Timaru instructed the adolescents on their own terms, using the Csángó way of speaking. The local fieldworker and Laihonen, and in some sites also the teacher(s), helped the adolescents during the recording with technical issues and could also ask them questions about the places. In the evening, the adolescents could take the iPad home, where they would record activities in connection with the Csángó culture. Typically, they interviewed their grandparents and recorded cooking, singing, and telling stories or prayers by their grandparents. The next day they edited an iMovie film (c. 10 min). At this stage, the adolescents were already working independently, and they were given a copy of their video as well, which they could then watch at home.

Figure 1. Capture of an adolescent-edited iMovie ‘A falu ahol születtünk’ (Hun. ‘The village where we were born’). An example of video editing: superimposed captions. © Laihonen, with research participants’ permission.

The whole task was a voluntary project for the adolescents, and they would often stay after the ordinary school hours to further edit their videos. The task was surprisingly easy to facilitate, it seemed as if the students were very eager to engage in a project using technology, which was known to all, but available for very few in the villages. According to feedback, the adolescents profited from the project in gaining more self-confidence in technology and using their own way of speaking (cf. csángósan beszélünk ‘we speak the Csángó way’; see Bodó et al., Citation2017 for a discussion).

In the videos, the oral narratives were mostly in the local vernacular, the captions varied. Sometimes the adolescents produced standard Hungarian expressions such as in : A falu ahol születtünk ‘the village where we were born’. In the same video there was a caption in a highly substandard and stigmatised form: kik vagyunk münk ‘who we are’. A Google search on the form brings one result, indicating the unlikeliness Hungarian standard speakers would use it in writing, whereas the standard form kik vagyunk mi brings over 200,000 occurrences.

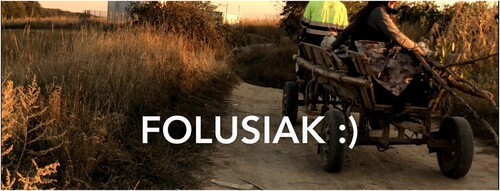

Similar examples are abundant in the data. Different local forms appear according to pronunciation instead of standardised orthography, for instance FOLUSIAK:) ‘villagers’ instead of the standardised Hungarian falusiak (). also illustrates the use of emoticons and capital letters, typical for less normative multimodal text genres.

Figure 2. Capture of an adolescent-edited iMovie, cropped screenshot (to preserve anonymity of people in the image). An example of a caption displaying orthography of Csángó grassroots literacy. © Laihonen, with research participants’ permission.

There are also lexical items that are used only by Csángós in Moldavia, not elsewhere in Hungarian-speaking communities, for example csáit fōz ‘make tea’, in which csái is the Csángó equivalent of standardised Hungarian tea (see ).

Figure 3. Capture of an adolescent-edited iMovie, cropped screenshot (to preserve anonymity of people in the image). An example of a caption displaying orthography and vocabulary of Csángó grassroots literacy. © Laihonen, with research participants’ permission.

In , we can also notice the replacement of the standard diacritic ő with ō, pointing perhaps to the unusuality of writing Csángó or Standard Hungarian digitally, since literacy is taught in Romanian in all schools in Moldavia. In this case, however, we rather see the replacement of the special character ő with ō, ő being perhaps unusual for the students to find in the iMovie character set. The characters ő or ō are not part of Romanian standard orthography, which the students could not use as a resource in this case.

In these examples, a grassroots idea of the ‘Csángó way of speaking’ (see Bodó et al., Citation2017) makes pragmatic multilanguaging (Pennycook & Makoni, Citation2020) ideology possible: there is no need to commit to a normative standardised version of a named language. In these captions, we can see a multilingual practice combining the Csángó way of speaking with the influence of the school spreading Romanian orthography and the Csángó Educational Program disseminating Standard Hungarian spelling and normative literacy practices.

We argue that such forms that Blommaert (Citation2007) has found typical for what he calls ‘grassroots literacy’, building on the whole language repertoire, can contribute to the legitimate performance of complex genres such as digital narratives in the local language, the Csángó way of speaking. In traditional educational settings, where Hungarian is seen as an ‘artifact tied to literacy and nationhood’ (Pennycook & Makoni, Citation2020, p. 79), students do not get that far, because they make too many ‘mistakes’, ‘mix’ registers and ‘violate’ language standards and ‘borders’ of named languages (e.g. in orthography). During the participatory videography projects, the adolescents also gained recognition of the Csángó culture in their families. Further, the project connected different generations of Csángós, as well as built a bridge between education and home. When Laihonen later visited the villages, the adolescents told him how they have proudly shown their products to parents and other family members.

In sum, co-producing iMovies solved different purposes. First, it created natural and motivated occasions for local Hungarian language use, connected different generations (e.g. adolescents interviewed their grandparents) as well as established a link between formal education and home (i.e. videos recorded at home are discussed in class). Second, it generated data for investigating linguistic identity, grassroots literacy (see Blommaert, Citation2007), concepts of space and learning environments as well as language practices. In this rural Northeast Romanian context, iPad and tablet were in general already known for the adolescents in 2017, but they were still very rare, e.g. one or two adolescents in the school might have possessed one. According to feedback, the use of an iPad and iMovie application proved to be very exciting and motivating for the adolescents, who thus did not seem to pay so much attention to normative expectations of language use and made use of their full linguistic repertoire both in speaking and writing. For the organisers of the language revitalisation programme, it provided a good example for creating a situation where Hungarian was used in a natural collaborative setting rather than in a formal instructional context.

4.2 Case 2: adapting 360° videography to the exploration of co-located Finnish and Swedish medium schools in Finland

Szabó's example comes from a 2017 fieldwork in Finnish and Swedish medium schools that share premises. Finland is a bilingual country with Finnish and Swedish as official languages. This bilingualism is manifested in two parallel tracks of education: a Finnish and a Swedish medium one (From, Citation2020a, pp. 38–42). The policy of language separation manifested in two parallel monolingual educational tracks has been considered as the way to shelter the lesser used national language, Swedish, from language shift to the language spoken by a numerical majority of inhabitants, Finnish. Although the monolingual habitus in both tracks of education is strong, the spatial arrangement of educational spaces has challenged language separation in some 40 co-located campuses in which a Finnish medium school and a Swedish medium school share a campus (From, Citation2020b). These so-called co-located schools are administratively autonomous institutions but share infrastructure that typically include the cafeteria, the P.E. hall as well as arts and technology workshops (From, Citation2020b; Laihonen & Szabó, Citation2023). In brief, co-located schools are two separate ‘monolingual’ schools with different languages of instruction, but share the same premises, thus co-located schools often collaborate and might organise shared courses and other activities across the official ‘language border’ (see From & Sahlström, Citation2017).

The ways how multilingual practices are manifested in everyday practices illuminates some paradoxes of Finnish educational language policies. In co-located schools, controversies arise due to the official language separation (see Gorter & Cenoz, Citation2017), which often leads to the strict compartmentalisation of languages. For instance, such compartmentalisation is operationalised in the chapter on bilingual education in the Finnish national core curriculum where the teacher is stated to have ‘a monolingual role in the group’ (FNAE, Citation2014, p. 154) and, consequently, the basic principle is formulated as follows: ‘as the language of instruction changes, so does the teacher’ (p. 154). In other words, in a conventional European setup such as the Finnish one, education is organised institutionally in a monolingual manner, even though the participants of education are often multilingual.

In a project involving two Finnish and Swedish medium co-located secondary school campuses in Ostrobothnia in Finland, institutionally ‘mixed’ student groups were recruited on a voluntary basis, through their teachers, to record campus sites significant to them with a 360° camera. This technological solution was chosen to investigate how the students would use the potential of the hemispheric view in 360° videography when capturing and thus visually representing their schoolscapes. We worked on two campuses. In both sites, the schools recruited one group each, consisting of four students, two from the Finnish medium and two from the Swedish medium institution. We did not receive detailed information about the language background of the students, except for their medium of instruction, which was either Swedish or Finnish. For convenience and anonymity, we use the Finnish and Swedish terms meaning ‘upper secondary school’, that is, Finnish Lukio and Swedish Gymnasium, when referring to the separate, but co-located, Finnish-medium and the Swedish-medium institutions, respectively.

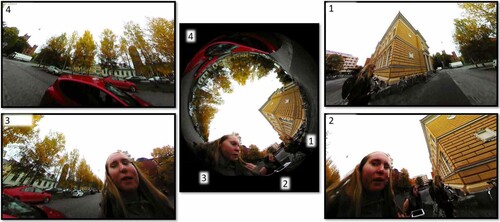

In the video project on both campuses, the researchers (From and Szabó) first introduced the students into the use of the 360° camera. The researchers emphasised that the students could record anything they find relevant for their campus life; they can, for example, go for a walk with the camera or interview their peers. In these demo sessions, the researchers used the terms multilingual environment (in English) and ‘co-located schools’ (Fin. kieliparikoulut; Swe. samlokaliserade skolor) when describing what could be presented in the video. After the demo session, the students were left on their own to design and carry out the recording. This resulted in approximately one hour of student-produced footage in total (for a published showcase of the videos, see From & Szabó, Citation2017). Student groups first had brief unsupervised discussions on project content and practicalities and then started working. One of the student groups chose to shoot their video in a classroom to stage a short scene of an English lesson. One of the students played the role of the teacher while the others were sitting at their desks, taking notes. Realising that the 360° camera captures both the front and back of the classroom, they decided to place the camera on a tripod in the middle of the classroom so that both the enacted teacher's and the enacted students’ faces would be seen in the recording. Through the organisation of the space, the division of activities and the exploitation of the technical opportunities of the 360° camera, they reconstructed a setting in which the ‘teacher’ was active (writing on the blackboard, speaking English), while the ‘students’ were passive (sitting still and writing).

Another group decided to walk with the 360° camera to produce a guided tour-like video (see Szabó & Troyer, Citation2017), which they also narrated. In the footage, there are no signs of any special attention to the full potential of 360° videography as all the students move together, facing the same direction. This use of a 360° camera in a ‘traditional’ way with one dominant angle was the choice of the students. The students used Finnish and Swedish to comment what they recorded, most typically according to the language of instruction of their institution. While walking through spaces allocated to Lukio or Gymnasium, they occasionally made critical remarks on the language separation manifested in spatial arrangements (e.g. in Excerpt 3). They also visited spaces that institutionally ‘belong’ to both institutions, e.g. the P.E. hall and the Arts classroom. They identified such spaces of shared infrastructure as ‘bilingual’ in their comments. The below examples demonstrate how the various spaces were conceptualised by the students during the walking tour through their interactional practices. We refer to the students by pseudonyms (Oona and Kalle for Lukio; Åsa and Britta for Gymnasium). We use abbreviations (L for Lukio and G for Gymnasium) in the excerpts when the students call their institutions informally by their shortened names.

The division of languages among the students according to respective institutions is especially observable in question-answer sequences. In Excerpt 1, the students negotiate where to walk and what to include in the video:

Excerpt 1

Oona mihin me mennään nyt?

Fin. ‘where are we going now?’

Åsa öö ganska gympasal?

Swe. ‘perhaps to the P.E. hall?’

Oona okei

Fin. ‘okey’

Excerpt 1 is a typical question–answer sequence between students from different languages of instruction institutions, where the students use their respective school languages. As observed by Szabó and Troyer (Citation2017), the handling of technology often influences the sequential organisation of interaction. In this walking tour, the students from Lukio held the camera (Kalle) and the voice recorder (Oona) which put them in the leading role in this conversation; that is, they often took a dominant role in question–answer pairs through initiation of a question (‘where are we going now?’) and evaluation of the response (‘okey’). It is obvious that all four students master both Finnish and Swedish, at least for the needs of this conversation, since the turns indicate understanding of previous turns and are aligned to the activities performed in them (e.g. answering a question). That is, while students reproduce the parallel monolingual norm of their respective institutions by sticking to the use of their affiliated language, they at the same time perform competence in both languages of the co-located campus. In Excerpt 2, the students discuss further places to visit.

Excerpt 2

Oona oota ny, ku mietin miss me ei vielä käyty

Fin. ‘wait a tick, I wonder where we haven't yet been’

Åsa på andra sidan

Swe. ‘on the other side’

Oona joo

Fin. ‘okey’

Excerpt 2 displays the practice of conceptualising the campus as having two sides (From, Citation2020b) according to the institution and, most importantly, language. As in Excerpt 1, the idea of two sides is shared by Oona, even though it is referred to in Swedish, indicating that this is a general principle of navigation in this campus. Referring to ‘sides’ serves as shorthands for expressions such as suomenkielinen puoli (Fin. ‘Finnish-speaking side’) and finska sidan (Swe. ‘Finnish side’) elsewhere in this walking tour conversation. The words toinen (Fin. ‘other’/‘second’) and andra (Swe. ‘other’/‘second’) rhyme with the subject called ‘the other/second national language’ (Fin. toinen kotimainen kieli, Swe. andra inhemska språk) which is compulsory for the speakers of national languages in the national core curriculum (i.e. Swedish for Finnish speakers and vice versa; FNAE, Citation2014: Chapter 13.4.2). Thus, we can say that discourses around the separation of languages and thus spaces to ‘ours’ and the ‘others’ are well aligned with the spirit of national language policies for education in Finland. Further, in this very walking tour, ‘the other side’ in some cases refers to a building, mainly associated with Gymnasium, which is located on the other side of the street. For example, shows students as they cross the street to get to a building of the campus which houses facilities used by both institutions.

Figure 4. Student-recorded mobile 360° video: different visual representations captured from various angles, using a 360° video viewer software (images 1–4). © Szabó and From, with research participants’ permission.

While the two ‘sides’ of the campus work as points of navigation in space, across institutions and languages in the walkthrough, in Excerpt 3, the students thematise a region of the campus, which is located in between the Finnish and Swedish ‘sides’:

Excerpt 3

Oona yhteisvessat

Fin. ‘shared toilets’

Kalle kyllä, yhteiset vessat, sekä G, että L pääsee tuonne kuselle

Fin. ‘yes, shared toilets, so that both G, and L too can go there to pee’

In this co-located campus, there was a corridor section with toilets which was not allocated to either ‘side’ by the students. In their discourses, it resided in the junction of two wings of the main building, one wing belonging to Lukio and the other to Gymnasium. In Excerpt 3, Oona and Kalle, perhaps pointing to the paradoxes of language and space separation, speak in an ionising stance, which is indicated by the use of colloquial expressions (e.g. ‘go for a pee’) while Åsa and Britta are chuckling in the background. Such distancing from taken-for-granted practices and ways of speaking is very rare in these student-recorded videos. In our previous investigation (e.g. Laihonen & Szabó, Citation2023) with traditional researcher-led methods, we documented more resistance to discourses of language separation disseminated and enforced by school personnel. Now, the students were assigned to record a short video presenting their campus, which resulted mostly in a rather unreflected recycling of mainstream discourses on co-located schools.

Next, we analyse students’ explicit reflection on the research situation and the research subject. Excerpt 4 shows a frequent sequence, which happened when the students entered a classroom. The students were instructed to ask for permission to record the video in each case they encountered people on their way and tell them to cover their faces if they do not wish to be recorded. As a part of this permission requesting sequence, they also described what they were doing:

Excerpt 4

Oona täällä tutkitaan siis niinku millast elämä on kaksikielisellä kampuksella

Fin. ‘so here we study how life goes on in a bilingual campus’

Kalle jep. ja koska meillä on tää nyt on tämmönen luokka, jota käyttää sekä G:n puoli, että

tota L:n puoli, niin nyt voi sitten piilottaa naamaansa nopeesti, ei me kauan täällä

viivy

Fin. ‘sure. and cause this is such a classroom that it's used both by G's side and L's

side, so you can now quickly hide your face, we won't stay here for long’

In explaining the situation, the students mention that they study a ‘bilingual campus’. It appears that instead of a ‘co-located’ campus, as used by researchers, the students refer to the two schools as a ‘bilingual’ campus. At the same time, they also mention that the classroom is used by both institutions (‘sides’), implying that the bilingualism on campus is meant as the parallel (i.e. separate) use of two languages. In a similar manner, Kalle later comments that ‘here is the gym, there both Swedish and Finnish speaking students have P.E.’ (Fin. tässä on liikkasali, tässä on sekä ruottin-, että suomenkieliset opiskelijat on täällä). That is, according to the students’ narrative, the students at both schools use parallelly (in time) the same spaces and languages, but they are discursively presented as fundamentally Swedish or Finnish speaking students.

In this video project, students worked in institutionally mixed groups, they could freely exchange their reflections, and work independently, not restricted or controlled by researchers. Thus, the video project has helped participants to co-construct a perspective from which to explore their own language practices and detect challenges. Further, videography has helped us build student-led bottom-up co-operation among co-located schools. That is, the project created meeting places, where two languages could be heard at the same time. Therefore, the students’ video projects had the potential to undermine the strict language separation and parallel monolingualism of the Finnish education system and help to transform it towards functional multilingualism. According to their feedback, the students found this activity a meaningful school project connecting languages with collaboration across language borders.

5. Discussion and conclusion

In this methodologically focused paper, to illuminate different variations of the use of participant-recorded videos suitable for different contexts, we have described two projects with multilingual communities in educational settings. While discussing our main findings, we acknowledge the limitations of a comparative approach due to the substantial differences in our contexts. Our two cases mirror different language policies and ideologies, different educational systems as well as participants’ dissimilar prior experience with the applied technologies. As a result, we avoid direct comparisons between the two projects.

The collaboratively defined societal aim of the projects presented in this paper has been to foster multilingualism. The project with the Moldavian Csángó aimed at creating safe environments for the youth who represent a non-dominant culture. It facilitated the literary use of the local minoritised vernacular by teenagers and established a link between formal education and home as well, to connect the generations through empowering the minoritised language users. In Finland, co-located schools as fundamentally multilingual environments constitute a potential asset for language learning. Previous research (e.g. From, Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Laihonen & Szabó, Citation2023) suggests that several barriers exist that may discourage interaction between students and teachers from the two co-located schools. In this project, we have engaged the students in creating a new meeting place and method for such interaction to emerge.

Our projects extend schoolscape research with participatory practices which offer considerable advances in collaboratively studying the moment-to-moment nature of language practices and the related language ideologies in and across multilingual spaces. In other words, this methodological orientation has allowed us to collaborate directly with participants and improve the language learning potential within their learning environments. The participatory video projects give an example of affordances to inquiry and activity-based learning by doing, which helps to elevate the ideological, institutional and linguistic barriers for the youth in multilingual and minoritised positions. We also found that the video-recorded materials enhanced the construction of learner-driven representations of space and language use, which in turn revealed emic perspectives on the schoolscape.

We find that both traditional and 360° videography make it possible for participants to immerse the viewer into a central observer position. In Laihonen’s ‘traditional’ videography project, the one-angle-at-time iMovies represented the perception of young learners as the researchers did not end up directly influencing the filming or editing. This was achieved by the user friendliness of the technology and software. A 360° camera was also experimented with in Moldavia; however, there it did not work out as expected: it was established that already iMovie and iPads represented cutting edge technology in that context and they were enough to draw the learners’ attention away from the normally constraining normativities of minoritised language use, especially literacy. In addition, the editing of the iMovies proved to be an exciting task for the Moldavian teenagers, making researcher influence minimal in that process. In both cases, it was surprisingly simple to facilitate the video projects, and the participants appeared eager in taking the project to their own directions.

Considering challenges, we acknowledge that the timeframe in our rapid focused ethnographic projects did not make it possible to go beyond the initial steps of a wider collaboration that could have covered several activities and involved a wider circle of educational stakeholders. A further participatory move would also be analysing the materials together. However, we see added value in the presented projects especially from the point of view of initiating interaction about the contested use of local language resources in the given communities. Further, we consider our participatory approach successful as it created meaningful and purposeful activities for participants, generated analysable data that showed how participants constructed and represented their inhabited linguistic landscapes in multimodal discourses as well as set up a methodological solution for the empowerment of the participants in language matters as well as in other much needed transportable skills connected to technology use in their contexts. As a next step, we consider how it would be worth establishing connections with artistic and creative fields in this type of inquiry (see Bradley et al., Citation2018).

Ethical statement

Szabó’s and Laihonen’s research plans used the guidelines and templates provided by the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity (TENK). In Szabó’s case, no separate statement from the Ethical Committee of the University of Jyväskylä was necessary. Laihonen’s research plan was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University of Jyväskylä on 8 March 2017.

Acknowledgements

We thank Carina Fazakas-Timaru for her contribution and assistance in Laihonen's case study. We also appreciate Tuuli From's substantial role in designing and implementing the fieldwork of Szabó's case study. Both authors wish to express their gratitude to Heini Lehtonen and Janne Saarikivi for their valuable comments and suggestions on a previous version of this paper, as well as to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback, which improved the paper in a significant manner.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ackerman, S., Gleason, N., & Gonzales, R. (2015). Using rapid ethnography to support the design and implementation of health information technologies. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 215, 14–17.

- Ayae, A., & Savski, K. (2023). Echoes of the past, hopes for the future: Examining temporalised schoolscapes in a minority region of Thailand. International Journal of Multilingualism. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2022.2164770

- Blommaert, J. (2007). Grassroots literacy. Working papers in language diversity 2. University of Jyväskylä.

- Bodó, C., Barabás, B., Fazakas, N., Gáspár, J., Jani-Demetriou, B., Laihonen, P., Lajos, V., & Szabó, G. (2022). Participation in sociolinguistic research. Language and Linguistics Compass, 16(4), e12451. https://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.12451.

- Bodó, C., Fazakas, N., & Heltai, J. I. (2017). Language revitalization, modernity, and the Csángó mode of speaking. Open Linguistics, 3(1), 327–341. https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2017-0016

- Bradley, J., Moore, E., Simpson, J., & Atkinson, L. (2018). Translanguaging space and creative activity: Theorising collaborative arts-based learning. Language and Intercultural Communication, 18(1), 54–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2017.1401120

- Brown, K. D. (2005). Estonian schoolscapes and the marginalization of regional identity in education. European Education, 37(3), 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/10564934.2005.11042390

- Brown, K. D. (2012). The linguistic landscape of educational spaces: Language revitalization and schools in southeastern Estonia. In H. F. Marten, D. Gorter, & L. van Mensel (Eds.), Minority languages in the linguistic landscape (pp. 281–298). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brown, K. D. (2018). Shifts and stability in schoolscapes: Diachronic considerations of southeastern Estonian schools. Linguistics and Education, 44, 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2017.10.007

- Christensen, P., & James, A. (2017). Research with children: Perspectives and practices. (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Clark, A. (2010). Transforming children’s spaces: Children’s and adults’ participation in designing learning environments. Routledge.

- De Wilde, J., Verhoene, J., Tondeur, J., & Van Praet, E. (2022). ‘Go in practice’: Linguistic landscape and outdoor learning. In E. Krompák, V. Fernández-Mallat, & S. Meyer (Eds.), Linguistic landscapes and educational spaces (pp. 214–231). Multilingual Matters.

- Dressler, R. (2015). Signgeist: Promoting bilingualism through the linguistic landscape of school signage. International Journal of Multilingualism, 12(1), 128–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2014.912282

- Facer, K., & Enright, B. (2016). Creating living knowledge. University of Bristol, AHRC Connected Communities.

- Faulstich Orellana, M. (1999). Space and place in an urban landscape: Learning from children’s views of their social worlds. Visual Sociology, 14(1), 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725869908583803

- FNAE = Finnish National Agency for Education. (2014). National core curriculum for basic education.

- From, T. (2020a). Speaking of space: An ethnographic study of language policy, spatiality and power in bilingual educational settings. Helsinki Studies in Education, 94. University of Helsinki.

- From, T. (2020b). ‘We are two languages here.’ The operation of language policies through spatial ideologies and practices in a co-located and a bilingual school. Multilingua, 39(6), 663–684. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2019-0008

- From, T., & Sahlström, F. (2017). Shared places, separate spaces: Constructing cultural spaces through two national languages in Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 61(4), 465–478. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2016.1147074

- From, T., & Szabó, T. P. (2017). Samlokaliserade skolor: Samarbete över språkgränser/Kieliparikoulut: Yhteistyötä yli kielirajojen/Co-located schools: Cooperation across language boundaries. Video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eBPrHP3f7wQ

- Gal, S. (2017). Visions and revisions of minority languages: Standardization and its dilemmas. In P. Lane & J. Costa (Eds.), Standardizing minority languages in the global periphery: Competing ideologies of authority and authenticity (pp. 223–242). Routledge.

- Gorter, D., & Cenoz, J. (2017). Language education policy and multilingual assessment. Language and Education, 31(3), 231–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2016.1261892

- Gorter, D., & Cenoz, J. (2022). Linguistic landscapes in educational contexts: An afterword. In E. Krompák, V. Fernández-Mallat, & S. Meyer (Eds.), Linguistic landscapes and educational spaces (pp. 277–290). Multilingual Matters.

- Harris, L., Cunningham, U., King, J., & Stirling, D. (2022). Landscape design for language revitalisation: Linguistic landscape in and beyond a Māori Immersion Early Childhood Centre. In E. Krompák, V. Fernández-Mallat, & S. Meyer (Eds.), Linguistic landscapes and educational spaces (pp. 55–76). Multilingual Matters.

- Hart, R. (1979). Children’s experience of place. Irvington.

- Irvine, J. T., & Gal, S. (2009). Language ideology and linguistic differentiation. In A. Duranti (Ed.), Linguistic anthropology. A reader (pp. 402–434). Wiley–Blackwell.

- Jakonen, T. (2018). The environment of a bilingual classroom as an interactional resource. Linguistics and Education, 44, 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2017.09.005

- King, P. T., Cormack, D., Edwards, R., Harris, R., & Paine, S. J. (2022). Co-design for indigenous and other children and young people from priority social groups: A systematic review. SSM – Population Health, 18, 101077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2022.101077

- Krompák, E., Fernández-Mallat, V., & Meyer, S. (2022). The symbolic value of educationscapes – Expanding the intersections between linguistic landscape and education. In E. Krompák, V. Fernández-Mallat, & S. Meyer (Eds.), Linguistic landscapes and educational spaces (pp. 1–28). Multilingual Matters.

- Laihonen, P., Bodó, C., Heltai, J. I., & Fazakas, N. (2020). The Moldavian Csángós: The Hungarian speaking linguistic minority in North-Eastern Romania. Linguistic Minorities in Europe Online. https://doi.org/10.1515/lme.12543347

- Laihonen, P., & Szabó, T. P. (2018). Studying the visual and material dimensions of education and learning. Linguistics and Education, 44, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2017.10.003

- Laihonen, P., & Szabó, T. P. (2023). Material change: The case of co-located schools. In J. Ennser-Kananen & T. Saarinen (Eds.), New materialist explorations into language education (pp. 93–110). Springer.

- Malinowski, D., Maxim, H. H., & Dubreil, S. (2020). Language teaching in the linguistic landscape: Mobilizing pedagogy in public space. Springer.

- Menken, K., Pérez Rosario, V., Alejandro, L., & Valerio, G. (2018). Increasing multilingualism in schoolscapes: New scenery and language education policies. Linguistic Landscape. An International Journal, 4(2), 101–127. https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.17024.men

- Niedt, G., & Seals, C. A. (2021). Linguistic landscapes beyond the language classroom. Bloomsbury.

- Nind, M. (2014). What is inclusive research? Bloomsbury.

- Ozer, E. J., Newlan, S., Douglas, L., & Hubbard, E. (2013). “Bounded” empowerment: Analyzing tensions in the practice of youth-led participatory research in urban public schools. American Journal of Community Psychology, 52(1-2), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-013-9573-7

- Park, J., & Bucholtz, M. (2009). Introduction. Public transcripts: Entextualization and linguistic representation in institutional contexts. Text & Talk - An Interdisciplinary Journal of Language, Discourse & Communication Studies, 29(5), 485–502. https://doi.org/10.1515/TEXT.2009.026

- Pennycook, A., & Makoni, S. (2020). Innovations and challenges in applied linguistics from the global south. Routledge.

- Pitkänen-Huhta, A., & Pietikäinen, S. (2016). Visual methods in researching language practices and language learning: Looking at, seeing, and designing language. In K. King, Y.-J. Lai, & S. May (Eds.), Research methods in language and education. Encyclopedia of language and education (pp. 1–13). Springer.

- Rampton, B. (2001). Critique in interaction. Critique of Anthropology, 21(1), 83–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308275X0102100105

- REC. (2001). Council of Europe. Parliamentary Assembly. Recommendation 1521. Csango minority culture in Romania. https://assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/Xref-XML2HTML-en.asp?fileid=16906&lang=en

- Scollon, R., & Wong Scollon, S. (2003). Discourses in place: Language in the material world. Routledge.

- Szabó, T. P. (2015). The management of diversity in schoolscapes: An analysis of hungarian practices. Apples – Journal of Applied Language Studies, 9(1), 23–51. https://doi.org/10.17011/apples/2015090102

- Szabó, T. P., & Dufva, H. (2021). University exchange students’ practices of learning Finnish: A language ecological approach to affordances in linguistic landscapes. In D. Malinowski, H. Maxim, & S. Dubreil (Eds.), Language teaching in the linguistic landscape (pp. 93–117). Springer.

- Szabó, T. P., & Troyer, R. A. (2017). Inclusive ethnographies: Beyond the binaries of observer and observed in linguistic landscape studies. Linguistic Landscape. An International Journal, 3(3), 306–326. https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.17008.sza

- ten Have, P. (2004). Understanding qualitative research and ethnomethodology. Sage.

- Troyer, R. A., & Szabó, T. P. (2017). Representation and videography in linguistic landscape studies. Linguistic Landscape. An International Journal, 3(1), 56–77. https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.3.1.03tro