ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to provide an overview on the current state of research on primary school teachers’ beliefs concerning multilingualism; 1,785 articles were detected and 31 of these articles were included in the corpus. We employed a scoping review methodology to explore primary school teachers’ beliefs on multilingualism. Nearly half of the corpus studies were published in the last three years, and more than half of the included studies were carried out using qualitative research methods. The results show that the researchers did not meet on common ground regarding the concept of beliefs and handled the concept of beliefs on multilingualism diversely. The findings from the analyzed studies show that the teachers’ beliefs on multilingualism can be grouped in three different categories as rejecting, moderate, and supporting beliefs. The analysis results highlight the currently prominent role of research on teachers’ beliefs on multilingualism. Also, the high amount of qualitative research conducted on the topic suggests that continuing along the lines of qualitative approaches to encounter the challenge of social desirability in researching teacher beliefs can be beneficial. Based on the results of this review, the authors suggest a characterisation of the term ‘teacher beliefs’.

1. Introduction

The aim of primary school education is to prepare children appropriately for self-determined and active participation and involvement in a society that is expected to struggle with continuously changing challenges. In such an increasingly multilingual world, dealing with multilingualism, and more specifically, migration-related multilingualism can be perceived as a phenomenon that contributes to the complexity of teachers’ professional actions. In recent years, teacher beliefs have been attributed a key role in research on teacher training and teacher professionalisation (Lundberg & Brandt, Citation2023). On an overall view, what can be said on the qualities of teacher’s beliefs prevailing among primary school teachers on dealing with multilingualism in class?

The diversity of studies on teacher beliefs across different disciplines has made the research landscape complex and confusing. Also, the theoretical developments in competence-based teacher professionalisation theory may be one reason why research on teacher beliefs became more and more prevalent in the last decade.

In this context, the main purpose of this scoping review is to provide an overview of the existing literature on primary school teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism, clarify the concepts of ‘multilingualism’ and ‘teachers’ beliefs’, and summarise their main findings.

This article reveals the existing literature and gaps in the field for further research. Therefore, we think that this review will contribute to the development of the research field on teacher professionalisation.

We aim at answering the following research questions:

What are the characteristics of the studies included in this scoping review?

How are primary school teachers’ beliefs on multilingualism conceptualised in the relevant literature?

How are the beliefs of primary school teachers shaped in these studies?

In order to answer the first research question, we analyzed the main characteristics of the articles included in this review, such as year, methodology and country of publication. To answer of second research question, we explored how the main concepts, related to the topic, beliefs, teacher beliefs, and multilingualism, are conceptualised. Finally, we analyzed the available quantitative and qualitative findings to answer the third research question. Based on the analysis results, the paper suggests conceptual clarification by recommending a working definition for teacher beliefs.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Conceptualising teacher beliefs

Pajares (Citation1992) defined the term beliefs as a ‘messy concept’ by pointing to differences in the understanding of the term as well as in the empirical data collection and operationalisation of beliefs. In addition, there are discipline-specific tendencies in the use of different conceptualizations. The conceptual diversity is reflected in the variety of terms employed across different discourses. In international literature, mainly the terms teacher beliefs, teacher views, teacher attitudes, teacher perspectives, teacher opinions, teacher orientations, teacher viewpoints, approaches to teaching, conceptions of teaching, pedagogical content beliefs, and educational beliefs are used (Knudsen et al., Citation2021; Pajares, Citation1992; Rokeach, Citation1972; Staub & Stern, Citation2002; Youngs & Youngs, Citation2001). Among this range, the term ‘beliefs’ has gained common and multidisciplinary acceptance.

In terms of competence theory, beliefs can be described as a component of professional action competence of teachers (Baumert & Kunter, Citation2006). Beliefs are understood as self-normative, individual and are characterised (in contrast to knowledge) by emotional content (Dohrmann, Citation2021). It is assumed that the concept is highly stable, not easily shaken (Weiß, Citation2019), and that once acquired, job-related beliefs provide behavioural security. Moreover, there is consensus that the different beliefs are part of an individual's ‘beliefs system’ (Pajares, Citation1992) and comprise beliefs facets that could contradict and be hierarchical to each other (Läge & McCombie, Citation2015).

It is postulated that a person's value-based and correspondingly deeply held beliefs are distinguishable from situational competences, which encompass perception, interpretation, and decision-making skills as modelled in the competency model developed by Blömeke et al. (Citation2015, p. 7). Although non-behavioural beliefs are considered to guide action at a general level, whether they become effective in the teacher's behaviour depends on the specific situation (Buehl & Beck, Citation2014).

In summary, it can be stated that the term beliefs is often used as a container term for the minds of individuals and often equated with a variety of constructs (attitudes, subjective theories, values) (Hachfeld & Syring, Citation2020, p. 661). According to Skott (Citation2014, pp. 18–20), there is agreement on four core aspects regarding the concept of beliefs: they (1) are individual mental constructs that are subjectively true for the respective person; (2) consist of interwoven cognitive and affective parts; (3) are characterised by temporal and context-independent stability, only changeable by social practices that are experienced as meaningful; (4) influence the way teachers perceive and interpret their everyday life.

2.2. Conceptualising multilingualism

Multilingualism is the rule, not the exception in today's world (Tracy et al., Citation2014), and it is independent from social classes, societal backgrounds, and age groups (Grosjean, Citation2020, p. 13). What is understood by multilingualism in the current discourse? Three aspects can be highlighted in this regard:

Multilingualism can be described according to three different levels: societal, institutional, and individual. Especially the individual level of multilingual children in class as well as institution-related multilingualism have a strong relation to classroom teaching in primary schools (Montanari & Panagiotopoulou, Citation2019, p. 15). Despite different terms, in most definitions, there is a subdivision with reference to the individual, the community, and a sub-sector or institution.

Also, the concept of lifeworld multilingualism – coined almost 20 years ago (Gogolin, Citation2005) – describes the language abilities of individuals who grow up and live with more than one language. Accordingly, Clyne (Citation2017) describes multilingualism as the use of more than one language in daily life. According to the state-of-art, the focus is on everyday use of languages, not on the type or amount of linguistic resources.

The individual life world multilingualism of students can manifest itself in two different forms: internal and external multilingualism. Thereby, internal multilingualism describes different language varieties such as dialects or different language registers of an individual within one language. External multilingualism describes the variety of individual languages – i.e. different first languages and foreign languages spoken by a person. Thus, according to Wandruszka's (Citation1979) understanding of multilingualism, all children (including children who are supposedly growing up monolingual) experience linguistic differences. This broad understanding of multilingualism sharpens the view of children's different linguistic and educational prerequisites and leads to the conclusion that all children can be addressed as ‘multilinguals’.

2.3. Teachers’ beliefs on multilingualism

Considering the education of children, who are the builders of the future, teachers’ beliefs are of great importance. Based on the outlined theoretical understanding, it appears insufficient to describe beliefs with only two poles – positive and negative. Beliefs encompass far more complex underlying structures, as discussed by Bromme et al. (Citation2010). Therefore, data collected and studies conducted on teacher beliefs are crucial. Lundberg and Brandt (2022) argue that at a time when societies are increasingly globalised and migration flows are intensifying, it is important to use different methodologies (qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods) to better understand teacher beliefs about multilingualism.

Social desirability can be identified as the main obstacle in the empirical approach to understand teachers’ beliefs. Direct approaches using questionnaires or guided interviews give rise to concerns related to social desirability, as teachers may shy away to voice their individual beliefs when the research focus is obvious and strongly directed (Pohlmann-Rother et al., Citation2023).

How does teacher training influence pre-service teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism? A study from Schroedler et al. (Citation2023) showed a significant increase in the mean average scores of pre-service teachers before and after completing a compulsory module on multilingualism. While a quantitative study by Brandt et al. (Citation2024) suggests pre-service teachers hold positive beliefs about multilingual learners, the results also show a significant gap in their knowledge of educational linguistics. Notably, the study emphasises the need for teachers themselves to develop a strong foundation in this field. This knowledge is crucial for designing effective lessons that support multilingual learners in their continuous and systematic language development. In an experimental study for pre-service teachers, Fischer and Lahmann (Citation2020) show the positive impact of the linguistically sensitive teaching course on the participants’ beliefs on multilingualism and on their value of multilingualism.

Multilingualism is the norm; the fact that we have very heterogeneous and linguistically diverse classrooms underlines the importance of research on teacher beliefs on multilingualism. It can be assumed that in-service teachers have more hands-on experiences than pre-service teacher and, thus, also experiences with multilingual children. Yet, we know that it is especially the subjective evaluation of and not the amount of the experiences with multilingual students that have significant influence on the beliefs of primary school teachers (Pohlmann-Rother et al., Citation2023).

Current results from the questionnaire survey ‘BLUME I’ (Beliefs of Primary School Teachers on Multilingualism)Footnote1 show that factors, particularly those related to the amount of pre-service training and to the breadth of the content in in-service trainings in which teachers participated, shape the teachers’ beliefs. Also, the evaluation of the teachers’ experiences with multilingual students in class play a key role (Lange & Pohlmann-Rother, Citation2020; Lange et al., Citation2023b; Pohlmann-Rother et al., Citation2023). These factors shape the teachers’ beliefs on multilingualism towards more supportive or more rejecting beliefs. Supportive beliefs mean that teachers are facilitators in integrating the family languages of the students into teaching and see the multilingual competences of students as potential resources. In the qualitative interview study with language teachers, Haukås (Citation2016) finds that teachers see multilingualism not only as positive for learners, but also as a tool to support students to identify linguistic connections between languages.

2.4. Research focus of the review

The focus of this scoping review is on primary school teachers. Primary schools are often described as ‘schools for all children’. Primary school classes are characterised by a mostly unselected group of children – encompassing children with a wide range in e.g. cognitive skills, learning requirements and family backgrounds (Kluczniok et al., Citation2011). Primary school teachers can surely expect to encounter students who speak different languages in class, especially if a broad understanding of multilingualism is assumed according to which all students are multilingual. Primary school teachers are responsible for carrying out the teaching process in the languages in the curriculum. However, teachers have the freedom to create learning spaces in class that include the family languages of the students and are basically supported by the curriculum. The Minister of Education and the Arts in Germany, for example, explicitly refers to multilingualism as a resource, recommending the recognition and utilisation of this resource to foster the language development of primary school children (KMK, Citation2019).

All in all, an increased research interest seems to have arisen in recent years, focusing on teachers’ beliefs on multilingualism (Camenzuli et al., Citation2023; Lundberg & Brandt, 2023; Pohlmann-Rother et al., Citation2023). Therefore, there is a lack of clarity about how beliefs, teacher beliefs, multilingualism, and teachers’ beliefs on multilingualism are conceptualised in current studies. Furthermore, the review offers a comprehensive summary of the results of the studies included in the corpus.

3. Method: scoping review

Since scoping review and systematic review are often confused, the differences are outlined as follows (Brien et al., Citation2010; Pham et al., Citation2014). A scoping review is developed with the aim to map the current literature on a topic (Arksey & O'Malley, Citation2005). Scoping reviews are often used to comprehensively examine the key concepts (what terms are used and how are they understood) and how they are related to a specific research area (Anderson et al., Citation2008; Arksey & O'Malley, Citation2005; Munn et al., Citation2018). With a systematic review, the findings on a particular research area are examined in detail by synthesising or analyzing (meta-analysis) the findings within the framework of an open question (Bearman et al., Citation2015; Green et al., Citation2006; Munn et al., Citation2018; Pham et al., Citation2014). Therefore, scoping reviews can be precursors to systematic reviews as, with them, the groundwork can be laid to determine whether it is necessary and meaningful to conduct a full systematic review on a topic (Arksey & O'Malley, Citation2005; Munn et al., Citation2018).

The methodology of the current study is based on the scoping review stages outlined by Arksey and O'Malley (Citation2005). Arksey and O'Malley (Citation2005) suggest that when conducting a scoping review, the following five stages should be followed: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) selecting studies, (4) presenting the data in graphical or tabular form, and (5) collating, summarising, and reporting the results.

Accordingly, the first step of a scoping review is to formulate the research questions. The authors held regular weekly meetings from August 2022 until the end of February 2023 for this research. In the first meeting for this research, the purpose of the study and the research questions were defined.

The second stage is to identify the existing, relevant studies in the literature. Therefore, an extensive online search was conducted between August 10th and November 23rd in 2022. Consequently, studies published after this date were not included in the study. The databases Web of Science, Scopus, Eric and Doaj were utilised in this search. Also, the https://www.tandfonline.com/-website was manually searched through. The terms ‘primary school teachers’ beliefs’, ‘multilingualism beliefs in primary classroom’, ‘teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism’ and ‘teachers’ beliefs’ were used in the search. As a result, titles and abstracts of 1,785 identified articles were read.

The third step is to decide on the studies to be included in the review. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were identified for that and are presented in .

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria covered in the study.

The aforementioned criteria were established to enhance the research's quality, conduct in-depth analyses, priorities up-to-date information, ensure accessibility, and obtain data relevant to the research focus.

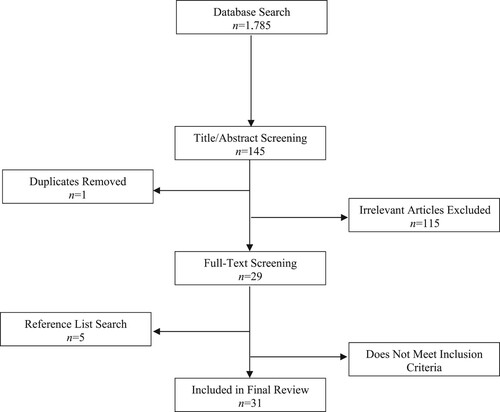

Based on the criteria in the table, the titles and abstracts of 1,785 studies were checked one by one. Subsequently, 145 studies that seemed suitable for the subject and purpose of the study were downloaded. Following this, the authors meticulously read these 145 individual pieces of research. Of these, 29 articles were chosen for analysis based on the study's purpose. The researchers used the bibliography search technique to re-scan these 29 papers to make sure that no publications were missed. As a result of this scanning, five additional articles were included in the study. In the meeting held by the authors in November 2022, three studies were decided to be excluded, because they did not fully meet all the set criteria. In addition, while eight studies included in the analysis (e.g. Gorter & Arocena, Citation2020; Hammer et al., Citation2018; Rodríguez-Izquierdo et al., Citation2020) were found to have collected data from both primary school teachers and from teachers in secondary schools; these were also included in the analysis. As a result, the corpus for the scoping review encompasses 31 articles. The following flowchart (see ) depicts the selection process of the study.

According to the fourth step (Arksey & O'Malley, Citation2005), the authors should present the data in graphs or tables. In order to present the data in a holistic way, it was decided to present the characteristics of the studies with graphs and the results of the analysis of the target concepts and research findings in form of figures.

The final stage of the scoping review is to compile, summarise, and report the results of the research focusing on the research questions. After completing the analyses, the researchers independently read the candidate articles several times, from beginning to end, to identify the main results presented in the following chapter.

3.1. Analysis of included articles

To answer the research questions and to characterise the empirical research on primary school teachers’ multilingualism beliefs, 31 selected studies were subjected to both descriptive and content analyses (Mayring, Citation2019, september). The descriptive analysis identified the country, year and methodological approach of the research. On the other hand, the concepts of ‘beliefs’, ‘teachers’ beliefs’, ‘multilingualism’ and ‘beliefs about multilingualism’ and the topic of multilingualism beliefs of primary school teachers were inductively analyzed by using content analysis. It is important to note that the categorisation of articles is qualitative and, therefore, influenced by our understanding and interpretation of the content, which may represent a potential limitation of the study's results.

4. Empirical results

Following, the results of the analyses of the identified 31 articles on the beliefs on multilingualism from primary school teachers are presented.

4.1. Characteristics of the studies

The researchers identified a total of 31 articles on the multilingualism-related beliefs of in-service primary school teachers. Basic information’s about these articles are presented in the graphs below.

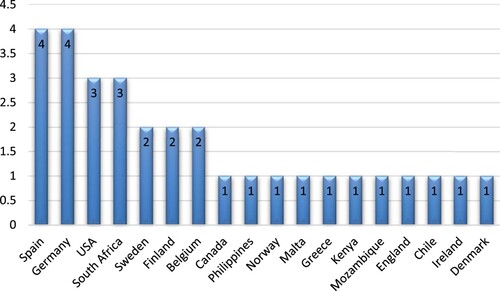

When analysed according to the national context of the research (Graph 1), it was found that the contexts of the studies were Spain (4), Germany (4), USA and South Africa (3), Sweden, Finland and Belgium (2), Malta, England, Canada, Philippines, Norway, Greece, Kenya, Mozambique, Chile, Ireland and Denmark (1). The author of two studies in Sweden was Lundberg, and two studies in Belgium were published by Van Der Wildt et al. Researchers from South Africa, Philippines, Kenya, and Mozambique discussed internal multilingualism, while other researchers discussed external multilingualism. Hammer et al. (Citation2018) compared the multilingualism-related beliefs of primary school teachers in Germany and in the USA, while Arocena Egaña et al. (Citation2015) compared the beliefs on multilingualism of teachers in Spain and in the Netherlands. Except for these two studies, the data collection is limited to the contexts mentioned above.

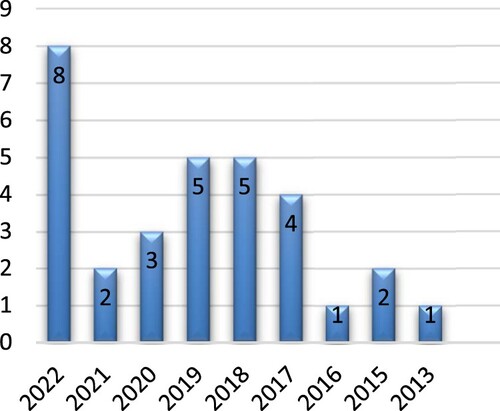

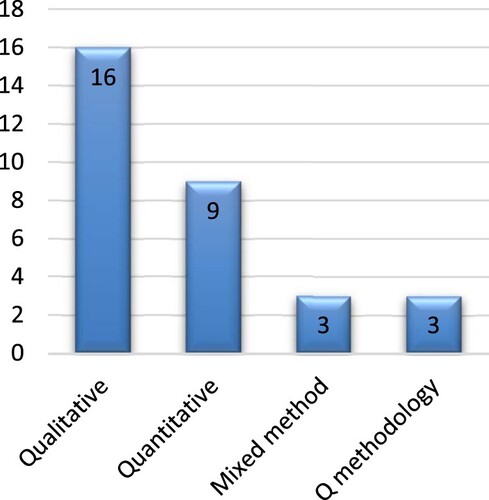

Regarding the identified studies, almost half of the studies (n = 13; 48%) were published within the last three years (see Graph 2). This result reveals that the research interest in multilingualism-related beliefs of primary school teachers on an international level has increased within the period of the last ten years (inclusion criteria: 2012–2022). More than half of the studies included in the scoping review are qualitative research studies (n = 16); the rest use a quantitative research approach (n = 9) (see Graph 3). Studies in which the Q- and mixed-methods were used (n = 3) have only a marginal share. Qualitative research was conducted based on interview studies (n = 16) (e.g. Omidire & Ayob, Citation2022), ethnographic approaches (n = 4) (e.g. Fredricks & Warriner, Citation2016), case studies (n = 4) (e.g. Terra, Citation2021), interviews with supporting observations (n = 3), and focus group studies (n = 3) (Gartziarena & Villabona, Citation2022). Quantitative research was carried out using causal and relational survey models. Different scales and questionnaires were developed and used in quantitative studies. Of particular interest for future research are the scales presented by Gorter and Arocena (Citation2020) and Krulatz et al. (Citation2024), both of which are published open access.

In our corpus, there is one experimental study on the multilingualism beliefs of classroom teachers (et al., Citation2017a). In this study, 27 model primary schools were selected in which teachers used a multilingualism-related tool in class. In the analysis of the three mixed-method studies, it is notable that in these studies questionnaires were used to collect quantitative data, and descriptive analysis methods were adopted for data analyses. For the qualitative data collection, Norro (Citation2021) and Toledo et al. (Citation2022) conducted semi-structured interviews, while Gartziarena and Villabona (Citation2022) conducted focus group discussions. Only little information is offered on the detailed mixed method-procedures. As to the three Q-methodology studies (Camenzuli et al., Citation2023; Lundberg, Citation2019a; Lundberg, Citation2019b), the Q-sets used for the studies are replicas.

4.2. Theoretical conceptualizations

Within the framework of the second question of this study, the aim was to analyze how ‘beliefs,’ ‘teachers’ beliefs,’ ‘multilingualism,’ and ‘beliefs on multilingualism’ were conceptualised in the studies of the corpus.

4.2.1. Beliefs and teacher beliefs

The analysis of the articles included in the scoping review showed that the authors explained the concept of beliefs and teachers’ beliefs in 19 of 31 studies (n = 19). In more than one-third of the studies (n = 12), the concept was not clarified. Overall, the researchers preferred to define teachers’ beliefs, a more specific concept, rather than beliefs in their studies.

Lundberg (Citation2019b) defined the concept of beliefs as an individual's self-judgment about the truth or falsity of a premise. Pohlmann-Rother et al. (Citation2023) stated that beliefs could be characterised by cognitive as well as by emotional and implicit content. According to Arocena Egaña et al. (Citation2015) and Norro (Citation2021), beliefs are implicit propositions that a person assumes to be true, resistant to change, and capable of influencing one’s action. Hammer et al. (Citation2018) defined beliefs as individuals’ perceptions of knowledge and as making sense of the world. Rodríguez-Izquierdo et al. (Citation2020) stated that beliefs are the opinions, attitudes, concepts, tendencies, and perceptions that an individual has about an object, person, or group.

As for the concept of teachers’ beliefs, the analyses revealed that the researchers discussed this concept in detail. Lundberg (Citation2019b) explained teachers’ beliefs as their attitudes towards schooling, teaching, learning and students in relation to education. However, he also stated that beliefs affect pedagogical decisions and are resistant to change. Gartziarena and Villabona (Citation2022) and Norro (Citation2021) described teachers’ beliefs as their cognition and stated that these beliefs affect their teaching practices. Similarly, Knudsen et al. (Citation2021), Krulatz et al. (Citation2024), and Omidire and Ayob (Citation2022) – while associating the concept of beliefs with ‘cognition’ – broadly stated that beliefs are what teachers think and know. Farrell and Guz (Citation2019) defined the teachers’ implicit, often unconsciously held assumptions about students, classrooms, and academic material to be taught. Arocena Egaña et al. (Citation2015), Pohlmann-Rother et al. (Citation2023), Terra (Citation2021), and et al. (Citation2017b) defined the concept of teacher beliefs as the way teachers perceive their daily lives, influencing and interpreting their classroom behaviour. Farrell and Guz (Citation2019), and Rodríguez-Izquierdo et al. (Citation2020) defined teachers’ beliefs as their implicit assumptions, perceptions, and attitudes about students, classrooms, and academic materials.

4.2.2. Multilingualism and beliefs on multilingualism

While analysing the included articles, we also examined the concepts of multilingualism and beliefs on multilingualism. As a result of our analysis, it was observed that most of the authors (n = 25) did not explain the concept of ‘multilingualism’ and did not outline what they meant with multilingualism. Camenzuli et al. (Citation2023), for example, stated that the concept of multilingualism can’t be fully understood theoretically due to its complexity. Some authors (n = 6) explained what they meant by ‘multilingualism’. For example, Björklund (Citation2013), Gartziarena and Villabona (Citation2022), Lundberg (Citation2019a), and Omidire and Ayob (Citation2022) explained multilingualism as the ability to acquire at least a second language and use these languages to communicate effectively. Lundberg (Citation2019a) referred to migrant children as multilingual learners in his study. On the other hand, Pohlmann-Rother et al. (Citation2023) consider the term ‘multilingualism’ as a wider concept encompassing ‘internal’ and ‘external’ multilingualism.

When the related articles were analysed, it was seen that authors tried to clarify the concept of multilingualism-related beliefs. Lundberg (Citation2019a) refers to the concept as teachers’ understanding and pedagogical thinking about multilingualism and multilingual learners. Alisaari et al. (Citation2019), Hammer et al. (Citation2018) and Putjata and Koster (Citation2023) explained that the teachers believe that all students can learn and take responsibility for this process. Gartziarena and Villabona (Citation2022) considered the term as teachers’ encouragement of minority students to use and develop their family language. Camenzuli et al. (Citation2023) defined it as the teachers’ understanding of multilingualism and awareness of multilingual educational environments. Knudsen et al. (Citation2021) define the related concept as the teachers’ acceptance of the cognitive benefits of being multilingual.

In addition, also the languages in which the researchers addressed the concept of multilingualism-related beliefs were examined. Within the scope of the analysis, it was found that mostly the analysed research focused on multilingualism-related beliefs relating to minority languages (n = 16, e.g. Basque), lesser studies addressed majority languages (n = 8, e.g. English, French, and Spanish) and local languages (n = 7, e.g. African local languages) (see ).

Table 2. The concept of multilingualism belief according to language context.

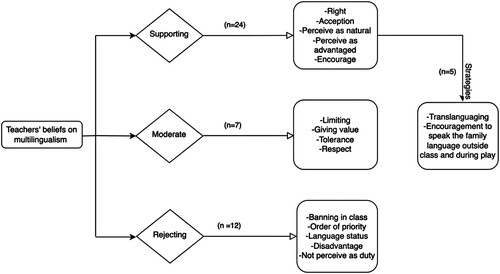

4.3. Describing the beliefs of primary school teachers on multilingualism

With the aim to answer the question on how the beliefs are shaped in the corpus articles, the findings of the studies included in the scoping review were analyzed (). The aim of this analysis was to condensate the results reported in the corpus studies. Overarching is the differentiation of the teachers’ beliefs into supporting (n = 24), moderate (n = 7), and rejecting (n = 12) beliefs on multilingualism. There are particularly more studies with results that predominantly show supporting beliefs of the teachers. The results also highlight moderate positions, and one-third of the studies refer to results on rejecting teacher beliefs.

The analyses also revealed strategies for the inclusion and development of multilingualism in teaching (n = 5). According to the analysed results of the studies in the corpus, supporting multilingualism in teaching is an important issue (Higgins & Ponte, Citation2017; Lundberg, Citation2019b; Oduor, Citation2015; Putjata & Koster, Citation2023), as it can provide personal and social advantages for the individual, such as developing a broader vocabulary and gaining socio-economic benefits in terms of future jobs (Arocena Egaña et al., Citation2015; Camenzuli et al., Citation2023; Farrell & Guz, Citation2019). Some of the studies outline that multilingual learners have a natural right to learn their family languages (Björklund, Citation2013; Dlugaj & Fürstenau, Citation2019; Norro, Citation2021).

Some studies found that teachers also have moderate beliefs on multilingualism, meaning that teachers expressed tolerance towards multilingualism (et al., Citation2017a; et al., Citation2017b) and respect for their students’ heritage languages (Cunningham, Citation2019). According to Dlugaj and Fürstenau (Citation2019), teachers think that it is necessary to encourage children to speak in their family language (e.g. in lunch clubs for language groups, using buddy systems and multilingual books). Such moderate teacher beliefs relate to encouraging children speaking in their family language, which is considered normal and natural in class (Dlugaj & Fürstenau, Citation2019). The results of the studies indicating rejecting beliefs on multilingualism in the classroom are associated with perceiving multilingualism as a barrier to learning the language of instruction (Hammer et al., Citation2018; Putjata & Koster, Citation2023; Rodríguez-Izquierdo et al., Citation2020; Terra, Citation2021). According to Oduor (Citation2015), teachers consider multilingual education or language support of children outside their scope of action and tasks. According to the results of some of these studies, prohibiting students from speaking their family language in class (Alisaari et al., Citation2019; Hammer et al., Citation2018) is found to contribute to the learning of the language of instruction (Fredricks & Warriner, Citation2016).

As for strategies to develop multilingualism, translanguaging (Camenzuli et al., Citation2023; Lundberg, Citation2019b; Omidire & Ayob, Citation2022) was found to be at the forefront. When the studies were analyzed in detail, it was determined that the translanguaging strategies mentioned by the authors are story telling and answering questions in class in the family language (Omidire & Ayob, Citation2022). Labeling various strategies as ‘translanguage strategies’ suggests that the subject is only addressed at a rather basic level. In addition, encouraging the use of the family language in free time (Cunningham, Citation2019; Lundberg, Citation2019a; Wallen & Kelly-Holmes, Citation2017) was highlighted in the publications. In the relevant articles, translanguaging as a strategy is presented in abbreviated form and only described as didactic approach, with which it is assumed that languages in their practical use do not represent units that can be clearly separated from each other but are networked and used strategically and flexibly by multilingual speakers (Camenzuli et al., Citation2023; Lundberg, Citation2019a; Wallen & Kelly-Holmes, Citation2017). Translanguaging can also be understood as a linguistic theory describing the language repertoire of multilingual speakers (Otheguy et al., Citation2015); this broader understanding is not addressed in the studies under review.

5. Summary of the results and discussion

The aim of this scoping review was to provide an overview of the current state of research on primary school teachers’ beliefs on multilingualism. For this purpose, three different research questions were sought to be answered. The first research question was posed to identify the characteristics of the 31 articles included in the current study.

Brice (Citation2015) stated that over half of the world's population speaks more than one language. In addition, the OECD (Citation2021) ‘international migration database’ shows that the migration population has increased in recent years. In 2021, OECD countries received 4.8 million new permanent migrants, an increase of 22 percent compared to 2020. Therefore, there is an increase in the number of students who speak more than one language in the classrooms, and this may have also influenced the rising awareness of multilingual classroom realities in educational research. The increase in research, a key finding of this scoping review, indicates a growing awareness of the urgency to acknowledge multilingualism as the norm in schools.

If taken seriously, the implications require a comprehensive reconsideration of all aspects related to teaching, including language-sensitive teaching materials, textbooks, classroom interaction, parent engagement, and language-fair testing.

Almost half of the studies were conducted by researchers from Germany, Spain, the USA, and South Africa. Regarding the context of South Africa, it can be said that there are many local languages in that region (Maseko, Citation2022). Spain is also multilingual, with 41 percent of the population living in officially bilingual areas (Lasagabaster, Citation2017). Regarding other countries, Germany, Spain, and the USA share a common characteristic of experiencing intensive immigration (OECD, Citation2021). These global migration and refugee movements have significantly impacted individuals’ everyday contact with multilingualism.

Interestingly, there are many qualitative studies among the studies. This can be interpreted as a development towards the insight that qualitative approaches are better suited to tackle the big problem of social desirability in research on teacher beliefs. Three studies were conducted using Q-methodology, which is relatively new in the field of educational science. According to Brown (Citation1993), Q-methodology aims to describe people's perspectives, ideas, beliefs, and attitudes subjectively and systematically in scientific research. Q-methodology is emerging within the discipline of psychology and into the social sciences as a method in which the strengths of quantitative and qualitative approaches can be combined.

In the framework of the second research question, we also examined how the terms beliefs, teachers’ beliefs, multilingualism, and multilingualism-related beliefs were conceptualised in the analysed studies. In the analyses, it was found that researchers preferred to define the concept of ‘teachers’ belief’, rather than the concept of ‘belief’. Moreover, most researchers did not clarify their understanding of belief; those who described their concept of beliefs did not converge on common ground, thus revealing a high variety of concepts. This result confirms the theoretically outlined disparities within the interdisciplinary beliefs discourses. As a common ground in the analysed publications, two key aspects can be highlighted. When defining the concept of teachers’ beliefs, two common issues are clarified by the authors. The first aspect is the reference to cognition (e.g. Calafato, Citation2019; Gartziarena & Villabona, Citation2022; Norro, Citation2021; Knudsen et al., Citation2021; Krulatz et al., Citation2024). The second aspect is that beliefs are underlined by most authors by referring to their key role for teacher behaviour in class (Farrell & Guz, Citation2019; Pohlmann-Rother et al., Citation2023; Terra, Citation2021; Özcan, Citation2022; Zembylas, Citation2005). Based on the results of this review and further considerations, the authors suggest the following characterisation of the term ‘teacher beliefs’:

‘Teacher beliefs as self-normative and subjective knowledge, organized in an overarching beliefs system of a person, which holds a set of beliefs facets that may complement, overlap, or conflict with each other. Beliefs facets encompass cognitive and emotional-affective aspects, and their stable character can be formed and developed in teacher training.’

Also, regarding the concept of teacher beliefs on multilingualism, it has been observed that researchers understand this concept differently. For example, the authors attributed to the concept meanings related to potential resources, teacher responsibility, awareness, pedagogical approach, and cognitive utility.

Song (Citation2014) reported that the concept of teacher beliefs on multilingualism has been used and defined in a variety of ways. The present results underline this finding. Therefore, it can be said that researchers generally understand and address the issue differently from each other.

In the present study, we also examined the concept of beliefs on multilingualism according to the status of the languages addressed in the corpus studies. It was found that more than half of the papers included in the scoping review addressed multilingualism in the context of minority languages, while the others addressed multilingualism in the context of major and local languages.

In order to answer the third research question, the examination focused on how teacher beliefs on multilingualism are shaped. For this purpose, the findings of the studies were analysed in detail. To illustrate the framework of the results, we presented the teachers’ beliefs on multilingualism in three overarching categories as ‘supporting’, ‘moderate’ and ‘rejecting’ (). In the included studies, it was found that the authors presented various strategies to deal with multilingualism, among which translanguaging was particularly frequently mentioned.

For example, in his interviews with teachers, Haukås (Citation2016) found that although teachers saw multilingualism as an asset for their own language learning, they could not identify a clear advantage of multilingualism for their students. In Makalela's (Citation2015) experimental study, the results were significant in favour of the group using translanguaging strategies. The study's findings demonstrate that the experimental classes employment of translanguaging strategies benefited the students’ affective and social development as well as their comprehension of the subject matter.

6. Limitations and further research

As this research is a scoping review study, inclusion and exclusion criteria were adopted for this study, and thereby, the selection of the corpus studies is limited to these criteria. The following suggestions can be stated as ideas for the selection for further reviews: (1) Only peer-reviewed articles written in English were included in the study. A follow-up study could involve studies written in different languages to counteract the language publication bias prevailing in academia. (2) This research is limited to studies indexed in ERIC, Web of Science, Scopus and Doaj databases. Researchers who are interested in the subject could further examine the studies in national databases of countries with a high number of local languages or countries with high numbers of immigrants. (3) With a competence-theoretical perspective, the relationship between the amount and the intensity of the teachers’ participation in training opportunities could be of further interest. This aspect and the beliefs of in-service and pre-service teachers on multilingualism are synthesised in detail in a systematic review currently prepared by the authors. (4) As a result of the scoping review, it was found that researchers used different scales and questionnaires to measure teachers’ beliefs on multilingualism. Therefore, it can be said that there is need for well-organised scales, which are valid, reliable, and objective. (5) As a result of our examination, we found only one experimental study on the subject. Experimental studies can be carried out to determine the factors that affect the teachers’ beliefs on multilingualism. Experimental research serves as a potent instrument in comprehending cause-and-effect connections, permitting us to manipulate variables and observe their effects. This is essential to understand how different factors related to teachers’ beliefs on multilingualism influence the results of a study.

The results of this scoping review can also be interpreted as an inventory to describe possible methodical and methodological approaches suited to empirically capture teacher beliefs. Currently, strong efforts are undertaken in the research study BLUME (Primary School Teacher Beliefs on Multilingualism) – conducted at the Technical University of Chemnitz and funded by the German Research Foundation – to develop innovative methodical and methodological approaches to identify the full picture of primary school teachers’ beliefs on multilingualism. The qualitative approach, utilising teaching situations as a stimulus for the interview situation with teachers, as well as methods of ‘loud thinking,’ were developed to enable uncovering the multifaceted picture of teachers’ beliefs on multilingualism (Lange et al., Citation2023, Citation2024).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The BLUME-study focusses on the Beliefs of Primary School Teachers on Multilingualism (Project Leader: Dr. Sarah Désirée Lange) is financed by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and conducted at the technical University of Chemnitz (Germany).

References

- Alisaari, J., Heikkola, L. M., Commins, N., & Acquah, E. O. (2019). Monolingual ideologies confronting multilingual realities. Finnish teachers’ beliefs about linguistic diversity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 80, 48–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.01.003

- Anderson, S., Allen, P., Peckham, S., & Goodwin, N. (2008). Asking the right questions: Scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Health Research Policy and Systems, 6(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-6-7

- Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Arocena Egaña, E., Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2015). Teachers’ beliefs in multilingual education in the Basque country and in Friesland. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 3(2), 169–193. https://doi.org/10.1075/jicb.3.2.01aro

- Barrenechea, I. (2018). What about elementary level teachers: A closer look at the intersection between standardization and multilingualism. Global Education Review, 5(2), 203–222. https://ger.mercy.edu/index.php/ger/article/view/380.

- Baumert, J., & Kunter, M. (2006). Stichwort: Professionelle Kompetenz von Lehrkräften. Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft, 9(4), 469–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-006-0165-2

- Bearman, M., Palermo, C., Allen, L. M., & Williams, B. (2015). Learning empathy through simulation. Simulation in Healthcare: The Journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare, 10(5), 308–319. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0000000000000113

- Björklund, M. (2013). Multilingualism and multiculturalism in the Swedish-medium primary school classroom in Finland—Some teacher views. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 6(1), 117–136. https://www.iejee.com/index.php/IEJEE/article/view/36.

- Blömeke, S., Gustafsson, J.-E., & Shavelson, R. J. (2015). Beyond dichotomies. Zeitschrift Für Psychologie, 223(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000194

- Brandt, H., Ehmke, T., Kuhl, P., & Leutner, D. (2024). Pre-service teachers’ ability to identify academic language features: The role of language-related opportunities to learn, and professional beliefs about linguistically responsive teaching. Language Awareness, 70–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2023.2193409

- Brice, A. E. (2015). Multilingual language development. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (pp. 57–64). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.23126-7.

- Brien, S. E., Lorenzetti, D. L., Lewis, S., Kennedy, J., & Ghali, W. A. (2010). Overview of a formal scoping review on health system report cards. Implementation Science, 5(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-2

- Bromme, R., Pieschl, S., & Stahl, E. (2010). Epistemological beliefs are standards for adaptive learning: A functional theory about epistemological beliefs and metacognition. Metacognition and Learning, 5(1), 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-009-9053-5

- Brown, S. R. (1993). A primer on Q methodology. Operant Subjectivity, 16(3/4), 91–138.

- Buehl, M. M., & Beck, J. S. (2014). International handbook of research on teachers' beliefs. International Handbook of Research on Teachers’ Beliefs, 1, 66–82. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203108437

- Calafato, R. (2019). The non-native speaker teacher as proficient multilingual: A critical review of research from 2009–2018. Lingua. International Review of General Linguistics. Revue internationale De Linguistique Generale, 227, 102700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2019.06.001

- Calafato, R. (2021). “I'm a salesman and my client is China”: Language learning motivation, multicultural attitudes, and multilingualism among university students in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. System, 103, 102645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102645

- Camenzuli, R., Lundberg, A., & Gauci, P. (2023). Collective teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism in Maltese primary education. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 379–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2022.2114787

- Clyne, M. (2017). Multilingualism. In F. Coulmas (Ed.), The Handbook of Sociolinguistics (pp. 301–314). Blackwell Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405166256.ch18.

- Cunningham, C. (2019). ‘The inappropriateness of language’: Discourses of power and control over languages beyond English in primary schools. Language and Education, 33(4), 285–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2018.1545787

- Da Costa Cabral, I. (2021). From discourses about language-in-education policy to language practices in the classroom—A linguistic ethnographic study of a multi-scalar nature in Timor-Leste. Language Policy, 20(1), 27–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-020-09563-z

- Dlugaj, J., & Fürstenau, S. (2019). Does the use of migrant languages in German primary schools transform language orders? Findings from ethnographic classroom investigations. Ethnography and Education, 14(3), 328–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457823.2019.1582348

- Dohrmann, J. (2021). Überzeugungen von Lehrkräften. Ihre Bedeutung für das pädagogische Handeln und die Lernergebnisse in den Fächern Englisch und Mathematik. Waxmann. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:22498

- European Commission. (2007). Final Report: High-Level Group on Multilingualism. European Communities. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/b0a1339f-f181-4de5-abd3-130180f177c7.

- Farrell, T. S. C., & Guz, M. (2019). "If I wanted to survive I had to use it": The power of teacher beliefs on classroom practices. TESL-EJ, 22(4), https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1204614.

- Fischer, N., & Lahmann, C. (2020). Pre-service teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism in school: An evaluation of a course concept for introducing linguistically responsive teaching. Language Awareness, 29(2), 114–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2020.1737706

- Fredricks, D. E., & Warriner, S. D. (2016). “We speak English in here and English only!”: Teacher and ELL youth perspectives on restrictive language education. Bilingual Research Journal, 39(3-4), 309–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2016.1230565

- Gartziarena, M., & Villabona, N. (2022). Teachers’ beliefs on multilingualism in the Basque Country: Basque at the core of multilingual education. System, 105, 102749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2022.102749

- Gogolin, I. (2005). Erziehungsziel Mehrsprachigkeit. In C. Rohner (Hrg.), Erziehungsziel Mehrsprachigkeit. Diagnose von Sprachentwicklung und Förderung von Deutsch als Zweitsprache (pp. 13–24). Juventa Verlag. file:///Users/schulpaedagogik/Downloads/10.1515_infodaf-2007-2-378.pdf

- Gorter, D., & Arocena, E. (2020). Teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism in a course on translanguaging. System, 92, 102272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102272

- Green, B. N., Johnson, C. D., & Adams, A. (2006). Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: Secrets of the trade. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 5(3), 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60142-6

- Grosjean, F. (2020). Individuelle Zwei- und Mehrsprachigkeit. In I. Gogolin, A. Hansen, S. McMonagle, & D. Rauch (Eds.), Handbuch Mehrsprachigkeit und Bildung (pp. 13–22). Springer VS. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007978-3-658-20285-9_2.

- Hachfeld, A., & Syring, M. (2020). Stichwort: Überzeugungen von Lehrkräften im Kontext migrationsbezogener Heterogenität. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 23(4), 659–684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-020-00957-7

- Hammer, S., Viesca, K., Ehmke, T., & Heinz, B. (2018). Teachers’ beliefs concerning teaching multilingual learners: A cross-cultural comparison between the US and Germany. Department of Teaching, Learning and Teacher Education.

- Harden, K., Punjabi, M., & Fernandez, M. (2022). Influences on teachers’ use of the prescribed language of instruction: Evidence from four language groups in the Philippines. Education Quarterly Reviews, 5(1), https://doi.org/10.31014/aior.1993.05.01.460

- Haukås, Å. (2016). Teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism and a multilingual pedagogical approach. International Journal of Multilingualism, 13(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2015.1041960

- Higgins, C., & Ponte, E. (2017). Legitimating multilingual teacher identities in the mainstream classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 101(S1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12372

- Kluczniok, K., Große, C., & Roßbach, H. G. (2011). Heterogene Lerngruppen in der Grundschule. Handbuch Grundschulpädagogik und Grundschuldidaktik, 180.), https://fis.uni-bamberg.de/handle/uniba/11533.

- KMK. (2019). Bildungssprachliche Kompetenzen in der deutschen Sprache stärken. https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/Dateien/veroeffentlichungen_beschluesse/2019/2019_12_05-Beschluss-Bildungssprachl-Kompetenzen.pdf.

- Knudsen, H. B. S., Donau, P. S., Mifsud, L., Papadopoulos, C., Dockrell, T. C., & E, J. (2021). Multilingual classrooms—Danish teachers’ practices, beliefs and attitudes. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 65(5), 767–782. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2020.1754903

- Krulatz, A., Christison, M., Lorenz, E., & Sevinç, Y. (2024). The impact of teacher professional development on teacher cognition and multilingual teaching practices. International Journal of Multilingualism, 711–727. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2022.2107648

- Läge, D., & Mccombie, G. (2015). Berufsbezogene Lehrerüberzeugungen als pädagogische Bezugssysteme erfassen: Ein Vergleich von angehenden und berufstätigen Lehrpersonen der verschiedenen Schulstufen in der Schweiz. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 61(1), 118–143. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:15273

- Lange, S. D., Huxel, K., Then, D., & Pohlmann-Rother, S. (2023a). "ich glaub, ich würd’s nicht sofort unterbinden" – Zum didaktischen Umgang mit Mehrsprachigkeit aus Sicht von Grundschullehrkräften. In M. David-Erb, I. Corvacho del Toro, & E. Hack-Cengizalp (Hrsg.), Mehrsprachigkeit und Bildungspraxis (pp. 103–121). wbv Media, S.

- Lange, S. D., Lilla, N., & Kluczniok, K. (2023b). Language usage and its relationship with cultural beliefs – Origin-related multilingualism as a potential resource of primary school teachers? Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Language, 3(1), 32–49. https://www.jssal.com/index.php/jssal/article/view/92.

- Lange, S. D., & Pohlmann-Rother, S. (2020). Überzeugungen von Grundschullehrkräften zum Umgang mit nicht-deutschen Erstsprachen im Unterricht. Zeitschrift für Bildungsforschung, 10(1), 43–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s35834-020-00265-4

- Lange, S. D., Alhallak, Z., & Plohmer, A. (2024). Sprachbezogene Diskriminierung als soziale Krise – Linguizistische Alltagspraktiken und deren Legitimierungen in der Grundschule. Zeitschrift für Grundschulforschung. Heft 2.

- Lasagabaster, D. (2017). Language learning motivation and language attitudes in multilingual Spain from an international perspective. The Modern Language Journal, 101(3), 583–596. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12414

- Lundberg, A. (2019). Teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism: Findings from Q method research. Current Issues in Language Planning, 20(3), 266–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2018.1495373

- Lundberg, A. (2019). Teachers’ viewpoints about an educational reform concerning multilingualism in German-speaking Switzerland. Learning and Instruction, 64), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101244

- Lundberg, A., & Brandt, H. (2023). Teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism: novel findings and methodological advancements: introduction to special issue. International Journal of Multilingualism, 20(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2022.2160726

- Makalela, L. (2015). Moving out of linguistic boxes: The effects of translanguaging strategies for multilingual classrooms. Language and Education, 29(3), 200–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2014.994524

- Maseko, B. (2022). Translanguaging and minoritised language revitalisation in multilingual classrooms: Examining teachers’ agency. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 40(2), 162–176. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073614.2022.2040370

- Mayring, P. (2019, September). Qualitative content analysis: Demarcation, varieties, developments. In Forum: Qualitative Social Research (Vol. 20). Freie Universität Berlin. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-20.3.3343.

- Mitits, L. (2018). Multilingual students in Greek schools: Teachers’ views and teaching practices. Journal of Education and e-Learning Research, 5(1), 28–36. https://doi.org/10.20448/journal.509.2018.51.28.36

- Montanari, E., & Panagiotopoulou, J. A. (2019). Mehrsprachigkeit und Bildung in Kitas und Schulen: Eine Einführung. utb GmbH. https://doi.org/10.36198/9783838551401

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Evaluating screening approaches for hepatocellular carcinoma in a cohort of HCV related cirrhosis patients from the Veteran’s Affairs Health Care System. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0458-6

- Norro, S. (2021). Namibian teachers’ beliefs about medium of instruction and language education policy implementation. Language Matters, 52(3), 45–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/10228195.2021.1951334

- Oduor, J. A. (2015). Towards a practical proposal for multilingualism in education in Kenya. Multilingual Education, 5(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13616-014-0015-0

- OECD. (2021). International migration database, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=MIG.

- Omidire, M. F., & Ayob, S. (2022). The utilisation of translanguaging for learning and teaching in multilingual primary classrooms. Multilingua, 41(1), 105–129. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2020-0072

- Otheguy, R., García, O., & Wallis, R. (2015). Clarifying translanguaging and deconstructing named languages: A perspective from linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review, 6(3), 281–307. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2015-0014

- Özcan, A. (2022). Secondary students’ metaphors for learning English. Journal of Research in Social Sciences and Language, 2(2), 118–131. https://www.jssal.com/index.php/jssal/article/view/79.

- Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Educational Research, 62(3), 307–332. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543062003307

- Pham, M. T., Rajić, A., Greig, J. D., Sargeant, J. M., Papadopoulos, A., & McEwen, S. A. (2014). A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Research synthesis methods, 5(4), 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1123

- Pohlmann-Rother, S., Lange, S. D., Zapfe, L., & Then, D. (2023). Supportive primary teacher beliefs towards multilingualism through teacher training and professional practice. Language and Education, 212–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2021.2001494

- Putjata, G., & Koster, D. (2023). ‘It is okay if you speak another language, but … ’: Language hierarchies in mono- and bilingual school teachers’ beliefs. International Journal of Multilingualism, 891–911. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2021.1953503

- Rodríguez-Izquierdo, R. M., Falcón, I. G., & Permisán, C. G. (2020). Teacher beliefs and approaches to linguistic diversity. Spanish as a second language in the inclusion of immigrant students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 90, 103035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103035

- Rokeach, M. (1972). Beliefs, attitudes and values: A theory of organization and change. Jossey-Bass. http://eduq.info/xmlui/handle/11515/11480.

- Schroedler, T., Rosner-Blumenthal, H., & Böning, C. (2023). A mixed-methods approach to analysing interdependencies and predictors of pre-service teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism. International Journal of Multilingualism, 20(1), 11–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2022.2125975

- Skott, J. (2014). The promises, problems, and prospects of research on teachers’ beliefs. In H. Fives (Ed.), International handbook of research on teachers’ beliefs (pp. 13–29). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203108437

- Song, S. Y. (2014). Teachers’ beliefs about language learning and teaching. In M. Bigelow, & J. Ennser-Kananen (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of educational linguistics (pp. 263–275). Routledge. file:///Users/schulpaedagogik/Downloads/10.4324_9781315797748_previewpdf.pdf

- Staub, F. C., & Stern, E. (2002). The nature of teachers’ pedagogical content beliefs matters for students’ achievement gains: Quasi-experimental evidence from elementary mathematics. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(2), 344–355. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.94.2.344

- Terra, S. E. L. (2021). Bilingual education in Mozambique: A case-study on educational policy, teacher beliefs, and implemented practices. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 24(1), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1441803

- Toledo, G., Lizasoain, A., & Cerda, K. (2022). Preservice and inservice teachers’ language ideologies about non-Spanish-speaking students and multilingualism in Chilean classrooms. Journal of Teacher Education and Educators, 11(1), 83–104. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/jtee/issue/69772/1054963

- Tracy, R., et al. (2014). Mehrsprachigkeit. Vom Störfall zum Glücksfall. In M. Krifka, J. Blaszczak, A. Leßmöllmann, A. Meinunger, B. Stiebels, & R. Tracy (Eds.), Das mehrsprachige Klassenzimmer (pp. 13–33). Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-34315-5_2

- Van Der Wildt, A., Van Avermaet, P., & Van Houtte, M. (2017). Multilingual school population: Ensuring school belonging by tolerating multilingualism. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 20(7), 868–882. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2015.1125846

- Van Der Wildt, A., Van Avermaet, P., & Van Houtte, M. (2017). Opening up towards children’s languages: Enhancing teachers’ tolerant practices towards multilingualism. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 28(1), 136–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2016.1252406

- Wallen, M., & Kelly-Holmes, H. (2017). Developing language awareness for teachers of emergent bilingual learners using dialogic inquiry. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 20(3), 314–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2015.1051506

- Wandruszka, M. (1979). Die Mehrsprachigkeit des Menschen. Piper.

- Weiß, S. (2019). Berufsbezogene Überzeugungen von Lehrerinnen und Lehrern. In E. Kiel, B. Herzig, & U. Maier (Eds.), Handbuch Unterrichten an allgemeinbildenden Schulen (pp. 156–163). Julius Klinkhardt. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kurt-Reusser/publication/281727467_Berufsbezogene_Uberzeugungen_von_Lehrerinnen_und_Lehrern/links/568a33c408ae1e63f1fbadea/Berufsbezogene-Ueberzeugungen-von-Lehrerinnen-und-Lehrern.pdf.

- Youngs, C. S., & YoungsJrG. A. (2001). Predictors of mainstream teachers’ attitudes toward ESL students. Tesol Quarterly, 35(1), 97–120. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587861

- Zembylas, M. (2005). Beyond teacher cognition and teacher beliefs: The value of the ethnography of emotions in teaching. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 18(4), 465–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518390500137642