ABSTRACT

Choreographer William Forsythe calls the work Duo a ‘project’—reflecting the piece’s long history of vicissitudes from 1996 to the present. We attempt to visualize continuity and change over several iterations of Duo, spanning a period of 20 years. Our methods involved graphical and statistical approaches to performance video annotation, considering seven videos acquired from Forsythe’s private archive. Collaboration with Duo dancers was critical to develop this choreographic knowledge. The duet Duo was chosen to focus on annotation of partnering, choreographic structure, and interpretation; the case study furthermore enabled review of annotation methods from Forsythe’s Synchronous Objects for One Flat Thing, reproduced (Forsythe et al. 2009) and built upon prior research of entrainment in Duo (Waterhouse, Watts, and Bläsing 2014). Studying a choreography longitudinally, with close regard of the performers’ testimonies and digital traces, the problem required innovative methods. For this article, we focus on how annotation was used within this project. We outline our particular interdisciplinary approach, merging perspectives from dance studies, praxeology and creative coding. We present the language and concepts of annotation chosen, technical tools used for annotating, procedures of annotation analysis, and conclusions of the research. Thereby we present novel visualizations of choreographic process.

1. Introduction

‘I gave that cue’ explained dancer Jill Johnson while reviewing an archival video of herself dancing the piece Duo by choreographer William Forsythe (Johnson Citation2018). Though the digitized video was grainy, made during Duo’s premier in the Ballett Frankfurt on January 20, 1996, Johnson could still decipher the pixelated moves of herself and her partner. Gathering and critically reflecting upon Duo dancers’ testimonies, the research project reported upon in this article presents a longitudinal examination of one choreography’s vicissitudes over two decades of interpretation. Using empirical methods to reconstruct the dancers’ practice, this study merges a dance studies perspective with a practice informed or praxeological approach to choreographic knowledge aligned with the ‘practice turn’ (Schatzki, Cetina, and Savigny Citation2006; Klein Citation2015; Reckwitz Citation2003). Interested in the broad question—What is choreography?—we adapt a practice informed approach, asking: How is Duo enacted by the dancers in practice, and how might this change over time? We also consider reflectively: How do we, as researches, enact and build understanding of Duo's choreography through our methods and tools?

The Duo ‘project’, as Forsythe calls it, and our motivation for studying this history are introduced in the adjoining pages (Forsythe Citation2019). The case study was chosen for many reasons, including the opportunity to focus on the intricacies of partner interaction and the piece’s fascinating history of reconstruction and renewal (). Aware that our methodology of performance video annotation would not only uncover organization, but produce knowledge based on looking from the present into the past, we aim to make our methods and findings comprehensible. We advocate generally for the incorporation of annotation methods in dance studies as a tool for performance analysis, and also explore the potential of graphical and statistical analysis of these markings to visualize choreographic process.

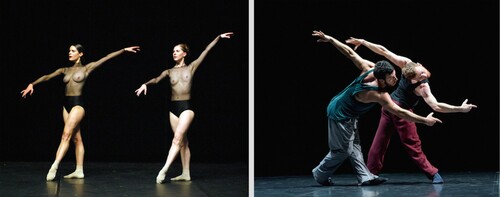

Figure 1. The Duo Project by William Forsythe. (left) Duo with dancers Allison Brown and Jill Johnson in 2003 © Jack Vartoogian/FrontRowPhotos. (right) DUO2015 with dancers Riley Watts and Brigel Gjoka © Bill Cooper.

1.1. Introducing the Duo project and scholarship

The theater is quiet. Two dancers stand in the dark space. Their partnering is light and agile, demonstrating a precise practice of steps and mutual sensitivity to time. The dancers move through positions evocative of ballet lines, breathing and sensing one another without ever touching. Between 1996 and 2018 the short duet described here, the Duo project, has been performed by dancers of Ballett Frankfurt and The Forsythe Company over 148 times in 19 countries by 11 dancers, to different scores by composer Thom Willems. Performed by female dancers in Ballett Frankfurt from 1996 to 2004, the duet was learned by male dancers in The Forsythe Company in 2012, but they performed the work only twice. When Forsythe was invited to include a short piece in ballerina Sylvie Guillem’s farewell world tour in 2015, he chose to substantially revise the Ballett Frankfurt version of Duo for these male performers, which he retitled DUO2015. Forsythe again adapted the piece for these dancers in 2018 for the touring program A Quiet Evening of Dance; it was retitled Dialogue (DUO2015).Footnote1 Forsythe explained: ‘I wanted to get [Duo] out there because it is an unusual use of ballet. All the movements are based on the classical vocabulary.’ He added further: ‘My goal is to make people see ballet better, that’s always been my goal’ (Crompton Citation2018).

The research undertaken here looks in greater detail at Forsythe and the dancers’ penchant for adapting choreography—finding out how choreography remains inventive and adheres organization that can be passed on from dancer to dancer. We also engage with Forsythe’s interest to develop the capacity to ‘see’ order manifest in choreography, and the choreographer’s previous work using digital technology and video performance archives to do so.

The Duo project has become a focus within the Forsythe scholarship owing both to the growing emphasis laid by Forsythe upon the piece in his touring repertoire since 2015, as well as the scholarly work of author and former Forsythe dancer Elizabeth Waterhouse (Waterhouse, Watts, and Bläsing Citation2014; Waterhouse Citation2017, Citation2018, Citation2020, Citationforthcoming). As the only piece that spans all three phases of Forsythe’s institutional operation (in Ballett Frankfurt, The Forsythe Company, and thereafter) the example of Duo is a very interesting case study for exploring the longstanding development and contextual factors that influenced Forsythe’s work. It also offers an example that richly complements Forsythe's own published discourse on improvisation of the individual body (Forsythe and ZKM Karlsruhe Citation1999/Citation2003) and counterpunctal methods of choreographing multiple bodies (Forsythe et al. Citation2009). This background research and how we further build upon it, is specified in Section 2.

How does a choreography emerge over time, and what constitutes its flexibility and order? Initially, the authors of this article (and some Duo dancers) saw drastic change between the Ballett Frankfurt and The Forsythe Company versions of Duo: seeing gendered performance, variance in the theatrical elements such as costume, music, and setting, variability in the movement style and also differences in the quality and relationship between performers. Interestingly, some Duo dancers found the essence of the choreography not so tied to these elements, but in a common heritage of creative and relational movement. One dancer advocated:

There aren’t eras in this work. Only ongoing explorations that continually connect the infinite possibilities of the ideas within it. It’s so clear that these experiences are all mapped onto each other, in concentric circles and networks of shared embodied ideas across time. (Johnson Citation2020)

Recognizing there is not a penultimate understanding of Duo, and that the dancers and choreographer each held valid perspectives, we aimed to systematically and critically examine the traces left of Duo as well as the dancers’ accounts of their labour.Footnote2

In summary, this article presents what could be learned about Duo using digital annotation to review archival performance videos and how we attempted this. The article highlights the team’s research background (Section 2), our hypotheses and questions about the case study (Section 3), the video sources studied (Section 4), the annotation concepts (Section 5), and the procedures for making and analyzing annotations (Sections 5 and 6). For the sake of brevity, we exclude literature review on the subject of Forsythe’s work, choreography, and praxeology, as well as a full account of our interview methodology—interested readers can find this elsewhere (Waterhouse Citationforthcoming). We end with our conclusions about change and continuity in Forsythe’s choreography Duo (Section 7).

2. Team and research background

2.1. Team

The technical team for collaboration on the Duo annotation (Florian Jenett, Monika Hager, and Mark Coniglio) all possessed hybrid backgrounds in art and programming.Footnote3 Jenett brought to the project the software system of Piecemaker and MoSys, digital tools developed for the ‘Motion Bank’ project to document, annotate and publish dance data and knowledge. Coniglio added his expertise as the creator of the software Isadora. Hager contributed her competence with Matlab and statistical modelling. The research architecture developed for performance video annotation provided an important component of Waterhouse’s mixed methods dissertation research (Waterhouse Citationforthcoming).

2.2. Synchronous Objects for One Flat Thing, reproduced

The website Synchronous Objects for One Flat Thing, reproduced (hereafter Synchronous Objects) (Forsythe et al. Citation2009) visualizes the choreographic attributes of Forsythe’s stage piece One Flat Thing, reproduced (2000): a complex instance of counterpoint in which a group of dancers maneuver deftly around a grid of 16 tables, performing ‘an almost mathematical construction of complexity’ (Sulcas Citation2011, 15). This precedent for digital annotation and data visualization of Forsythe’s choreography offered initial terminology for analyzing Duo, as well as methodology and a best practice example of interdisciplinary collaboration. We drew upon both of these, Waterhouse having participated in the project as a dancer consultant.

Synchronous Objects took direction from Forsythe’s research questions: ‘What else might this dance look like?’ and ‘What else, besides the body, might physical thinking look like?’ (Shaw Citation2011, 208; see also Manning Citation2013, 99–110). The intent was to convey the principles organizing and order manifest in choreography (Groves, Shaw, and DeLahunta Citation2007), what Forsythe foregrounded in his concept of counterpoint. Through collaboration, the team classified the principle of counterpoint manifested in the case study as three interlocking systems: movement, cues, and alignments. Thereby, Forsythe evolved his thinking about counterpoint from the provisional definition of ‘kinds of alignments in time’ (Sulcas Citation2011, 15) to counterpoint as: ‘a field of action in which the intermittent and irregular coincidence of attributes between organizational elements produces an ordered interplay’ (Forsythe and Shaw Citation2009).

The team’s annotation process involved many sorts of video markup: from videos of dancers talking-through and pointing-at video recordings, to transferring and codifying this data within an elaborate spreadsheet, before rendering animations upon the performance video. Rather than choosing to visualize individually authored annotations, such as Forsythe’s or animator Maria Palazzi’s observations, through conversations between Forsythe, the dancers and animators, the visualizations grew to conjoin many people’s understanding about the dance. To make these processes of building knowledge transparent, the team documented their working methods extensively, providing videos online to describe how they came to their understanding. They thereby presented a very rich archive of performance knowledge.

Though the duet Duo is less complex than the group dance One Flat Thing, reproduced, Duo foregrounds the nuance and intimacy of persons moving in counterpoint—a dance of relation—where relation is not an after effect of bringing two people together, but an intensive and constitutive component of practice (Leach and deLahunta Citation2017; Manning Citation2009; Waterhouse Citationforthcoming). Movements and relations are by their nature spread, multipart and changing. They may be difficult to reconstruct and categorize, as they merge perception, sociality, and intensity. Part of the challenge of the Duo research project was to find terminology and methodology to interpret Duo’s relational enactment. Another aim was to extend what had been addressed in Synchronous Objects, to look longitudinally and comparatively across a different work’s history.

Modeling Duo’s choreography involved not just understanding what took place one evening in performance, but also what can go wrong, and what else might have happened. This ‘logic of practice’ (Bourdieu Citation1980/1990; Klein Citation2015) we ventured, could be better viewed through study of multiple performances. We kept in mind the potential of Duo as a reserve of renewable ideas and inspiration, remembering, as Brian Massumi has written: ‘Reality is not fundamentally objective. Before and after it becomes an object, it is an inexhaustible reserve of surprise. The real is the snowballing process that makes a certainty of change’ (Massumi Citation2002, 214).

2.3. Entrainment in Duo

Duo foregrounds the dancers’ sustained attention to coordinated rhythmical motion and sound production, or entrainment—a term used by Forsythe and some dancers to describe their practice (Waterhouse, Watts, and Bläsing Citation2014; Waterhouse Citation2017, Citation2018). Previous research of the case study of Forsythe’s Duo focused on the perspective of dancer Riley Watts during his period learning and dancing Duo in 2012-2013 (Waterhouse, Watts, and Bläsing Citation2014). As a dance performed conversationally without orientation to a musical pulse, Duo was found to contradict prior scientific understanding of entrainment in dance, which had defined entrainment as the capacity to ‘move in time with an audio pulse’ (Schachner Citation2013, 243). Rather, the practice of ‘mutual entrainment’ was central to the dancers’ process of learning to dance Duo—entrainment understood as the coordinated and rhythmical interplay of motion and sound production by the two performers, as they enacted the choreographic progression of movements and breath. In the Ballett Frankfurt version of Duo, the dancers entrained mutually to one another in a shared musical atmosphere of live piano and electric strings by composer Thom Willems.

Duo’s co-motion involved a common ‘breath song’, learned implicitly while moving and practiced in pairs (Waterhouse, Watts, and Bläsing Citation2014, 10). Not only spending ample rehearsal time focusing on the vocal and kinaesthetic perception of being in-sync, the dancers learned to enjoy the flexibility and elasticity of their entrainment, what they described as being musical, playful, and inventive with one another. Watts told about how he holistically grew to have an intimate perception of his partner through hours spent in co-movement—engendering friendship, care, and affection. From initial analysis of video excerpts from two gala performances in 2013, it was found that this version of Duo involved many components of entrainment in the scientific literature: unison, turn-taking, complementary action, cues, and alignments. It was unclear, however, to what extent entrainment factored into earlier performances, and whether other dancers’ testimonies (including Watts’ partner) would offer new perspectives.

2.4. Ethnographic study of Duo

Waterhouse’s dissertation research on the dancers’ practice of Duo provided a reservoir of testimony, which we used to develop our model of the project’s longitudinal change. This involved interviews with nearly all Duo dancers (in particular Allison Brown, Riley Watts, Brigel Gjoka, Regina van Berkel, Jill Johnson, and Roberta Mosca) sustained over the course of three years (2015–2018), as well as interviews with the choreographer, composer, other dancers, and support personnel. Waterhouse’s history and embodied knowledge as a Forsythe dancer provided indispensable to these conversations. Yet, there were obvious limitations to the format of a sit-down interview for learning about the dancers’ practice. Four methods were developed: studio sessions in which Waterhouse practiced Duo together with the dancers, one teaching session in which Waterhouse observed a pair transmit the choreography to students, talk-through sessions in which the dancers commented upon archival performance videos, and data-review sessions assessing the annotation data highlighted in this paper. All of these were taped with an audio and/or video recorder, transcribed and supplemented with Waterhouse’s fieldwork notes. How these interfaced in our annotations is clarified in Section 5.1.

3. Hypotheses and questions

To study change and continuity in the choreography of Duo longitudinally, we focused on three clusters of questions and hypotheses, centering on the topics of the different versions of Duo, the variability of the work, and the role of entrainment therein.

Versions: Based upon Waterhouse’s ethnographic fieldwork with the dancers and preliminary study of the archival videos of performances, we had observed two primary choreographic structures of Duo (i.e. the Ballett Frankfurt version performed from 1996 to 2004 and the DUO2015 version since 2015), with an intermediary version in 2013. Through video annotation, we aimed to become more precise about how these two versions related (i.e. the extent to which they shared common movement, or approaches to interpretation, etc.).

Variability: Waterhouse’s fieldwork suggested that while Duo was variable, aspects endured that constituted the choreography specifically. We predicted that performances would change, or adapt, as new dancers entered and partnerships adjusted. We expected that the interpretive practice might transform between Ballett Frankfurt and The Forsythe Company. It seemed that the progression of Duo over time was not a linear evolution; rather, the choreography lived and breathed with the changing dancers that moved it.

Entrainment: A third hypothesis was that modes of entrainment featured strongly in Duo’s composition (Waterhouse, Watts, and Bläsing Citation2014). This is because mutual entrainment, or the sustained attunement to synchronize or rhythmically relate motion and sound production in the setting of dancing, permeated the dancers’ testimonies of their practice. We predicted that in addition to observing cues and alignments in Duo, the following matrix of entrainment modes would apply: unison, turn-taking, concurrent motion, solos, and breaks. We were uncertain what proportions these modes would take, and the extent to which they would vary longitudinally. We aimed to use annotations to explore this further.

4. Sources studied

The performance video archive for this study was drawn from the extensive records made by Forsythe for Ballett Frankfurt and The Forsythe Company, which included 37 archival videos of Duo performances.Footnote4 Dance scholars Tamara Tomic-Vajagic and Christina Thurner have presented balanced analysis noting the profit of video analysis as well as critical review of how traces may misrepresent performance—through the quality of the recording, the camera’s specific gaze upon the event and the absence of live and contextual cues (Tomic-Vajagic Citation2012, 73–76; Thurner Citation2015). One benefit of video performance analysis for our purposes was triangulation, that is, for comparing the changing appearance of the choreography shifting over time with the dancers’ memories of their embodied experience.

The count of 37 performances was however too large a sample to be annotated completely as the procedures were labour intensive.Footnote5 Therefore, a cross section of archival videos named key performances of Duo was selected spanning the history of the piece longitudinally: from 1996, 1997, 2000, 2003, 2013, 2015, and 2016 (see ). These key performances were not chosen to reflect the set of best or ideal performances of Duo. Rather they were selected to explore the diversity of the piece, by spanning its history in a representative manner. The criteria for selection were: (i) to foreground the artists who have danced Duo most frequently (ii) to follow these performers’ entry into the piece and maturation (iii) to capture the variation of the choreographic structure and the range of Duo performances within different theatrical settings, and (iv) to select videos of the highest quality possible.Footnote6 Duo dancers Allison Brown and Riley Watts aided in selection based upon these criteria.

Table 1. Key performances of Duo.

5. Annotation

5.1. Annotation approach and procedures

Our annotation scheme focused on three categories of markings: (1) movement material, (2) entrainment modes, and (3) transitions. This system was developed based upon dancer interviews, the precedent of Synchronous Objects, as well as movement analysis principles drawn from Rudolf von Laban’s Effort Theory (Laban and Lawrence Citation1947; Maletic Citation2005). The main difference between our approach and that of Synchronous Objects is that we foreground entrainment in Duo as a means of sustaining alignment, and thereby look more broadly at timing transitions, rather than isolating all of these as cues (see ). Thus, while counterpoint is an overarching concept within Forsythe’s oeuvre, we recognize that it manifests specifically within each piece, warranting adjustment of annotation parameters.

Table 2. Annotation categories: Duo research in comparison to Synchronous Objects.

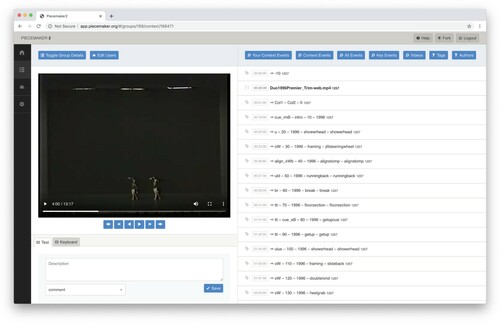

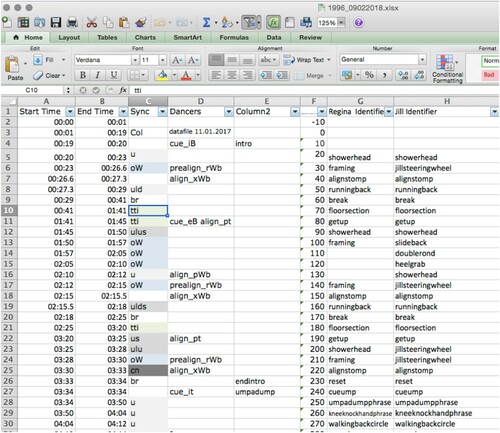

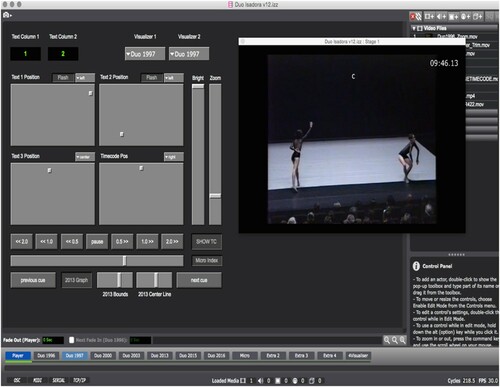

The annotation procedures began with talk-through interviews reviewing the key performances with the dancers. Based upon these interviews, Waterhouse then used Microsoft Excel to chronologically make protocols of the key performances using her evolving encoding system of counterpunctal categories (see ). This data was then imported into a software program called Isadora, which was programed to conveniently display the annotation on the video in realtime, to further analyze and error check the markings (see ). To compare markings across key performances, up to four key performances could be played synchronously in one viewer. The data was also imported into Piecemaker 2, which allowed for searching and filtering by features (i.e. to show all instances of cues, or all examples of unison, see ).

Figure 2. Screenshot showing annotation data for the 1996 key performance in Microsoft Excel. Columns A and B record the duration markings of the video; column C the category of entrainment; column D the transitions; Column E sectional markings; Column F the movement material identifier; Columns G and H reiterate informal names for the movement material of the left and right dancers respectfully, drawn from Waterhouse and the dancers’ lingo.

Figure 3. Isadora visualizer showing the 1997 key performance, timecode and annotation of ‘c’ for concurrent motion.

Piecemaker is a software for realtime video annotation emerging from The Forsythe Company’s documentation and dance-making practice (Rittershaus et al. Citation2019, editorial this issue). In its annotation interface, Piecemaker displays time-based annotations alongside the videos that they are related to. This list not only acts as a protocol of the annotations taken, it also allows the user to navigate the video by linking to the exact times in the video that the annotation relates to. A tagging system additionally gives filtering possibilities to be able to focus on specific aspects of the annotations and hence the material that is being examined. The seven Excel files produced by Waterhouse, which contained about 160–180 entries each, were imported to Piecemaker 2 for review and refinement. This information was added to create an overall Duo recordings research archive of 133 recordings (of performances, rehearsals and closely related pieces).

These ways of viewing, comparing and synchronizing enabled refinement of the system of annotation categories—yielding a complex taxonomy of concepts (see Section 5.2, see Supplemental data). Trouble points in the data were then targeting through a series of data-review interviews with the dancers. Our work analyzing and improving this data is still in progress and available online.Footnote8

5.2. Annotation categories: a model of counterpoint

5.2.1. Categories of entrainment

In Duo, we observed both movement alignment and rhythmic structuring of movement-breaks. In our model, we defined counterpoint (in Duo) as the general set of permutations of two dancers performing movement and movement-breaks rhythmically in relation to one another (i.e. at the same time). We defined movement and movement-breaks as follows:

Movement – a motion or series of motionsFootnote9

Movement-break – the opposite of movement, such as a duration of inertia, holding a pose, resting, taking a break, or otherwise not performing motion. Importantly, the dancer might not rest in the sense of recuperate, as some still-acts may be strenuous to hold.

We found that the rhythmical organization of movement and movement-breaks in Duo was structured according to mutual entrainment. We defined five modes:

Unison – partners performing the same movement synchronously

Concurrent motion – partners performing different or related movement at the same time, while attuning to one another’s rhythmsFootnote10

Solo – one dancer moves, while the other takes a movement-break or frames the foregrounded mover

Movement-break (defined above)

Intermittent motion/turn-taking – partners perform intermittent movement (i.e. alternating movement and rest) taking-turns. These movements may be identical, related or different.

Other – a mode not fitting the above categoriesFootnote11

For the purpose of assessing the validity of how well these categories apply to Duo, the additional category named other was included. This enabled Waterhouse to mark instances of the choreography that did not fall into the categories named above.

5.2.2. Subcategories of entrainment modes

Unison in Duo was rich with subtleties and nuance. To analyze this, we worked unconventionally with the Laban model of four fundamental motion factors, to address how dancers collectively (not individually) attended to the primary motion factors of space, weight, time, and flow (see Maletic Citation2005, in particular, 9–10). To this, we added the factor of symmetry: that dancers may be in alignment, but perform movements with opposite or related parts of their bodies. Subcategories of unison were defined as follows:

Flow – when two dancers perform flowing movement in unison side-by-side, their movement emphasizes the flow of the dyad

Space – when the dancers perform the same movements but face different directions there is spatial development of unison

Time – when identical sequences are offset in time they become a canon, the simplest form of concurrent motion

Weight – unison emphasizing lightness or strength

Symmetry – when dancers perform the same movements but with different sides of their bodies (for example, one using the right arm and the other the left)

Other – a mode not fitting the above categories

Even more complex entrainment can result from attention to two Laban Motion Factors. Of the myriad of combinations possible, the following were detected in Duo:

When weight and space are combined, unison with change of level up or down.

When weight and time are combined, unison modulated by falling.

When symmetry and time are combined, a canon with mirror symmetry.

When space and symmetry are combined, unison with mirror symmetry and spatial development.

When flow and time are combined, accented phrasing is produced, or counterpoint actions emphasizing rhythm.

When body, space, and time are combined, a canon with mirror symmetry performed not facing the audience.

Solos in Duo also showed nuance, necessitating addition of the subcategory solos with framing. This occurs when the soloist’s partner improvises minimal movements framing the soloist.

5.2.3. Movement material

The choreographic structure of Duo involves a prescribed sequence of interactions, including elements of structured improvisation. To study the longitudinal changes of this sequence, the movement material of the first performance was parsed into small units (between 1 and 10 seconds) and annotated. The analysis yielded 116 building blocks containing both movement and movement-breaks.Footnote12 The subsequent key performances were then annotated chronologically, noting the changes to the existing building blocks and additional elements. This enabled tracking of the genesis of the original elements and the addition of new material chronologically.

Sequence changes took the form of insertions, removals, repeats, scrambles, variations or complex remaking (see ). Examples of movement variation in Duo took place when some but not all attributes of the original movement were reproduced, such as performing just the legs or arms, or choosing to change the phrasing extensively. To identify these required Waterhouse to learn the movement from the dancers and to comparatively view performances.

Table 3. Sequence Changes to a Hypothetical Sequence of Building Blocks ABCDE.

5.2.4. Movement transformation

Watching the key performance from 2015, dancer Riley Watts noted the flexibility of the choreography. Referencing one instance in the archival video he noted: ‘Those were always, like playful moments that were improvised. We’re just playing with where it comes from. Like expansions on the material.’ At another point, he cautions, ‘We never transformed that’ defining an Alignment which stayed more regular (Watts Citation2017). In response to these subtleties, we also annotated the dancers’ practical approach to interpreting the prescribed sequences in each performance—subtleties of how they enacted the choreography. We named these properties of movement transformation. Relying upon dancer interviews, the following subtypes were defined:

Set – A planned sequence of movements/steps that the performer(s) reproduce as accurately as possible in performance.

Modified – A sequence in which one movement/step is briefly altered while preserving the sequence order (i.e. a change made to adjust one aspect of the movement form). This involved an occasional impromptu change to save balance and planned modification based on injury. These did not affect entrainment between partners and were usually made by one dancer.

Adapted – A sequence in which many seconds of movements/steps are adjusted while preserving the sequence order (i.e. changing the movement facing, dynamic, scale, body parts, fragmentation, etc.). Apart from adaptation of solo material, these required interactive negotiation.

Improvised – Invention of movement based upon a task, or an open improvisation inventing movement (i.e. without a task or a sequence referent).

Each building block was assessed according to the above scheme individually for each dancer and annotated appropriately.

5.2.5. Transitions: cues, prompts, Alignments

Transitions between modes of entrainment are important parts of the choreographic structure of Duo, and we relied on dancer interviews, such as the one cited in our title, to catalog these elements. Three forms of transitions were noted: cues, prompts, Alignment (designated with a capital A). These are outlined further below.

Cue. This term is used by Forsythe and the dancers to describe timing signals: usually practiced strategies of communicating timing information in order to start moving together. Cues interweave practice, communication, action and ethics. Many, but not all, cues are perceivable to a public. To discern these transitions, we relied heavily upon the talk-through and data-review interviews with the dancers.

Along with annotating when the cues took place, we also recorded their different mediums: audible breath, stomps, vocalized short phrases and movement itself. We also observed how they varied in their ‘leadingfollowing’, that is, who attunes to whom, or whether the attunement is mutual or hierarchical (drawing on terminology from Erin Manning, see Lepecki Citation2013, 34.). In the annotation of cues in Duo, it was found that cues may be doubled, or have more than one medium, for example, a cue that is both an inhale of breath and a movement cue. It was also possible that two cues are given at the same time by both partners. The annotation system was flexible enough to encode these complex instances. Ambiguous cues were also marked, such as vocal cues in which the speaker could not be identified.

Prompt. This term is one that Waterhouse developed for when the dancers spoke to each other on stage. Statements intended for one’s partner and not the audience, prompts were sequence reminders (such as ‘New Beginning’ ‘First’ ‘Snakedress’) and even supportive words (such as ‘Almost There!’). They were often said while doing, as opposed to causally before, reinforcing alignment.

Alignment. Practices of aligning are known to be a ‘fundamental principle of Forsythe’s work.’ According to dance scholar Roslyn Sulcas, they are ‘one of the ways that complex – even chaotic – activities on stage are rendered subtly comprehensible’ (Sulcas Citation2011, 15). Forsythe has described Alignments as ‘moments when the dancers’ movements echo one another in shape, direction, or dynamic’ (Sulcas Citation2011, 15). In Synchronous Objects, they are sometimes referenced as ‘sync-ups’. This is defined as ‘short instances of synchronization between dancers in which their actions share some, but not necessarily all, attributes. Manifested as analogous shapes, related timings, or corresponding directional flows...’ (Forsythe and Shaw Citation2009). In our practice-informed focus on Alignment, we explored in greater depth how Duo dancers accomplished these moments of movement synchronization. We defined Alignment as a specific transitionary instance of movement that helps the dancers to bind their time and transition entrainment modes: for example, when the Duo dancers are performing different movements and then arrive in the same pose, this is recognized as an Alignment. Differently than cues and prompts, which are typically audible communication, Alignments are movements or poses in which the dancers negotiated their timing. A ‘good’ Alignment, the dancers noted was often surprising; when it was unexpected to the dancers they believed it would also be surprising to the audience. This shows how modulating the audience’s attention was a part of the dancers’ performance logic.

Subcategories of Alignments were cataloged. Alignments took the form of identical or related poses, performing the same or related movements, or stomping the floor rhythmically. Their partner relation varied: sometimes they were achieved together; other times one dancer would take lead. It was found that for certain tricky Alignments, pre-Alignments were built into the choreography—key information preceding an Alignment, used to synchronize the action. Pre-Alignments thus reflected the dancers learning and strategizing to perform the choreography well. Our annotation terms distinguished all of these.

6. Analysis: statistics and visualization

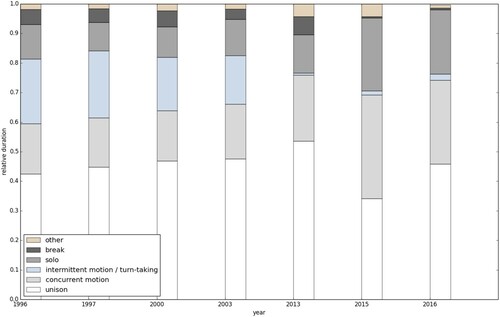

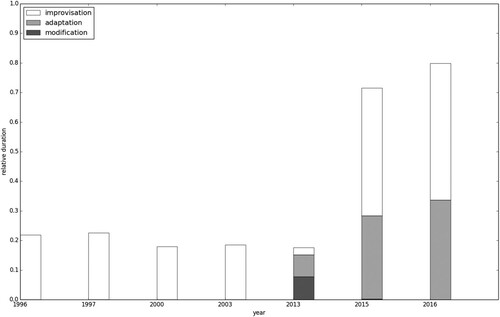

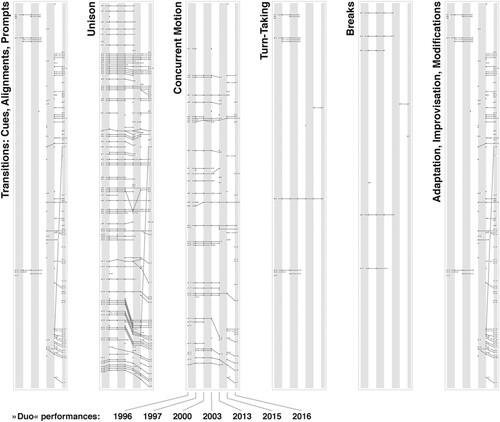

Two approaches were used to analyze the annotation data. First, employing a statistical approach, the data was mined to compute the cumulative duration for each annotation category’s markings and graph this information (i.e. to answer ‘How much unison was there?’ or ‘How many cues?’). This also enabled study of the relative proportions of each annotation focus longitudinally (i.e. ‘What percentage of the performance was in unison?’). We gained from this an overview of change and continuity, without exploring the specificities of precisely what elements or sections endured (see , and and ).

Table 4. Duration of key performances (seconds).

Table 5. Modes of Entrainment (%) of Duo key performances.

Table 6. Count of cues, Alignments and prompts of Duo key performances.

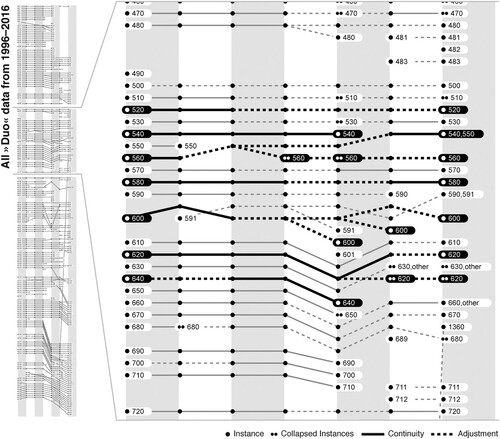

The second approach focused on the continuity of key performances, looking graphically at the (dis)continuity of markings ( and , for an enlarged version see https://duo.motionbank.org/). In these figures, the horizontal axis shows the progression of Duo key performances longitudinally. The vertical axis shows the movement building blocks (numbered dots), from the beginning of the Duo (top) to the end (bottom). Some of these instances have been extended in the choreography leading to multiple annotations. These have been collapsed in the graph (double dots). The horizontal lines were added to render continuities (solid line), adjustments (dashed line), and omissions in the order of these elements visible. An adjustment was defined as when a movement element or transition was repeated with variation—such as a unison section being changed to concurrent motion, or such a cue transforming who gave it. Note, the time scale is not preserved in this rendering (i.e. pertaining to the duration of the segment), just a sequential relation (order). Through filtering the information based on category, it was possible to show the degree of continuity of performances as discussed in the following section.

7. Conclusions

7.1. On Duo

Versions. The analysis confirmed that despite some dancers’ testimony to the contrary, structurally the authors of this paper observed two predominant versions of Duo, the Ballett Frankfurt version (1996–2004) and the DUO2015 version (2015–2016), with the reconstruction in 2013 serving as an intermediary. The dancers’ testimonies suggest that the gap between these versions did not correspond to the gendered differences of a male and female version, but rather to the personal style of each dyad, and the varying contexts in which these short works were performed.

Variability. Change in Duo varied in degree and kind. The small changes within performance took place, in part because of their liveness—as Duo dancer Jill Johnson explained, how the structure will ‘play out on any given night, is never the same’ (Johnson Citation2018). One significant aspect of Duo’s variability was the dancers’ changing interpretation practice. The amount of flexible (i.e. not set material) in Duo increased longitudinally from approximately 20%, to almost 80% (see ). In DUO2015, when the dancers referenced a sequence, there was interpretive freedom to transform the movement sequence—changing level, facing, style, and dynamic. Generally, these findings are understood to reflect differences between approaches to choreography in Ballett Frankfurt and The Forsythe Company. In the latter, the dancers were less frequently performing set material and more often engaging in relational improvisation involving realtime composition of alignment (i.e. different than Ballett Frankfurt procedures archived in Forsythe’s Improvisation Technologies) (Forsythe and ZKM Karlsruhe Citation1999/Citation2003).

Another aspect of change in Duo was the choreographer’s explicit structural revisions of the choreography. The proportions of entrainment modes are quite stable in the Ballett Frankfurt version between 1996–2003 (see and ). They change in 2013 when Forsythe cuts the introduction section. They shift again in 2015 when Forsythe edits Duo for the touring program, Sylvie Guillem: Life in Progress. For DUO2015 a new introduction to the piece is made, and many solos are added, lengthening the work (see ). The dancers performed the piece more frequently than any other dancers before them (in 52 cities internationally between April and December 2015) developing a fluency of partnering that enabled cues and transitions to become minimal and specific to their partnership (see and ). They also toured without Forsythe, allowing for the piece’s emergence to follow their interpretation practice before an audience and agency in self-directed rehearsal. Overall, the Duo project thus points to different conditions and phases, in which the choreographer and performers shape a work’s manifestation in dialogue with one another.

Entrainment. The model of counterpoint based upon alignment as entrainment modes had a strong fit to the Duo performances, with only between 1% and 4% of the material laying outside this matrix (see and ). The annotation process suggested the rhythms within entrainment to be pair specific, shifting as new dancers entered the work and established via consensus.

The proportions of entrainment modes were found to vary between versions, with more changes in entrainment modes and less pure unison in DUO2015 than in the Ballett Frankfurt version of Duo (i.e. greater complexity in the structure of entrainment). Possibly this reflects the influence of Synchronous Objects (2009), which enabled Forsythe to look at variations of kinds of alignment, and take more interest in ‘intermittent and irregular coincidence’ (Forsythe and Shaw Citation2009). It may also stem from Forsythe’s tendency to increase the complexity and speed of his choreographies as he comes to understand them, in order to refresh and break his own expectations.

The movement-breaks are also an interesting point of focus. In the Ballett Frankfurt version of Duo, movement-breaks are frequently structural lulls after the dancers descend to the floor. In the 2013 key performance, they take the forms of resetting position and shorter rests in standing (such as in 2013 when the dancers casually catch their breath while folded over with their hands on their knees). In the 2015 key performance, there is only one break in which the performers stand outside the light. These movement-breaks reflect the general shifts within aesthetics of contemporary dance since the 1990s, in which still-acts and rupture have come to play an important role (Brandstetter Citation2000; Schellow Citation2016 in particular 154–163). The structure of DUO2015 also generally presents the performers as more self-aware in its coding and frame-shifts, allowing for the dancers to play with their status as performers.

Continuity and Change. A filter system based on the tags that were generated during import into Piecemaker allowed us to look at specific aspects of change and continuity (see and ). Sections of Alignment and unison exhibit the most continuity throughout all seven key performances, meaning that these are the elements that have remained most consistent and constitutive over the course of the piece’s history. This corresponded with the dancers’ testimonies of their rehearsal practice, which emphasized reviewing material in unison. Concurrent motion shows a similar amount before and after 2013, but there are fewer connections running across this year. As we confirmed with the statistical analysis, turn-taking and breaks emerge mostly in the Ballett Frankfurt performances before 2013; also, adaption, improvisation and modifications show up in high numbers in the late performances from 2013 onwards. This adds to the understanding that practicing unison is the central component to the choreography, even as the complexity of the of counterpunctal structure and degree to which the dancers improvise within this structure increase over time.

One of the most surprising findings was that throughout the different versions of Duo project, the pairs still essentially reference a commonly agreed upon sequence of interactions with their partner—one that has been passed down from pair to pair. This makes Duo across its history much more about negotiation and agreement upon a shared movement sequence than previously expected. In other words, an important aspect of the choreography itself is how the dyads agree through rehearsal to interpret unison sections and timing choices together. In performance, this is reflected in how pairs use signals to communicate and modulate their attunement. Though some strategies of signaling were passed on from pair to pair, these also vary, pertaining to each pair’s communication and practiced tactics.

Thus even though the choreography of Duo and DUO2015 versions appear and sound differently (i.e. with different staging elements, gendered pairs, as well as movement aspects such as phrasing, emphasis on ballet technique, rhythm, and style of breathing-movement), the dancers are in fact referring much of the same, inherited unison movement sequence and Alignments. Interviews also confirmed that the dancers share a great deal of common information about the movement. This shows that the partners’ processing of choreography (i.e. interpreting what they have inherited) is a significant part of the development of the work.

7.2. Generally

The statistical and graphical analysis of annotation, as well as the process of making the annotations themselves, provided an unprecedented inspection of a choreography’s longitudinal history, showing Duo’s vicissitudes of (dis)continuity. Through detailed study of the changing manifestations of one piece, we aimed to understand how and why a piece of performance emerges over time. The study helped thereby to produce an important overview of a choreography: in contrast to concepts of choreography foregrounding that which results from explicit planning of the dancers’ movement by the choreographer and culminating in ephemeral performance, this enabled development of the argument that the choreography of Duo is a complex and emergent nexus of people, im/material practices, contexts, and relations (Waterhouse Citationforthcoming).

The research into Duo presented here shows how annotation as method can support the study of such complex inherent relations. Here, annotation based on dancer interviews and other previously annotated material (Synchronous Objects) helped shape a model of change. This model became manifested and further refined through the annotation of seven key performances, forming a vocabulary of change. Being translated into other forms this set of annotations also became a bridging tool between disciplines in this project and the basis of further exploration. Finally, it helped communicate aspects of change in Duo as can be seen in the graphs included in this paper.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (72.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Elizabeth Waterhouse

Dr. Elizabeth Waterhouse is a dancer and postdoc at the Institute of Theatre Studies at the University of Bern where she is part of the research project “Auto_Bio_Graphy as Performance” funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation. Her research as a dance scholar focuses on choreographic practices and aesthetics, ethnographic and oral history methodology, as well as digital techniques for research and documentation of dance practices. Waterhouse danced from 2004–2012 in Ballett Frankfurt/The Forsythe Company. In 2019, she was awarded a PhD in dance studies from the University of Bern/Hochschule der Künste Bern.

Florian Jenett

Florian Jenett is a Professor for Media Informatics / Digital Design in the Design Department of the Hochschule Mainz – University of Applied Sciences in Germany. He also co-directs the Motion Bank at Hochschule Mainz.

Monika Hager

Dr. Monika Hager completed her PhD in elementary particle physics in 2019 at the Institute for Theoretical Physics in Bern. She is an independent researcher in acoustic monitoring and sonification and works part-time as a high school teacher for physics.

Mark Coniglio

Mark Coniglio is a media artist, composer, and programmer. He is recognized as a pioneer in the integration of live performance and interactive digital technology. With choreographer Dawn Stoppiello he is co-founder of Troika Ranch, a New York City based performance group that integrates music, dance, theater and interactive digital media in its performance works. He is also the creator of Isadora®, a flexible media manipulation tool that provides interactive control over digital video and sound.

Notes

1 Both tours, Sylvie Guillem: Life in Progress and A Quiet Evening of Dance, were produced by Sadlers Well’s Theatre of London.

2 The theoretical debates on the difficulties of obtaining knowledge of tacit skills and practical understanding are beyond our scope here. From a basic performance studies approach, we were aware of the ‘inescapable transformation’ that happens to performance in writing (Phelan Citation1993/Citation2006, p.148); from a praxeological one, were also concerned with the potential to ‘destroy’ studies of practice through ‘instruments of objectification’ (Bourdieu Citation1980/1990, p. 11). Sociologist John Law takes a stance similar to ours, advocating that, ‘methods, their rules, and even more methods’ practices, not only describe but also help to produce the reality that they understand’ (Law Citation2004, 5).

3 Our research was conducted within two interdisciplinary projects: ‘Motion Together’ (Free University of Berlin/Bielefeld University/Hochschule Mainz) and ‘Dancing Together’ (University of Bern/Hochschule der Künste Bern) supported by the Volkswagen Foundation and the SNSF respectively.

4 These were unedited videos made by Forsythe’s team for the purpose of internal documentation, not edited dance films.

5 These annotations relied on Waterhouse’s expertise as a Forsythe dancer and could not be automated or distributed to assistants.

6 It is possible that this key performance selection overemphasizes change, through its criteria. For example, the key video from 2016, which was a performance in a church, has been criticized by Forsythe as a very specific and unusual setting, and not representative of the project. Yet, Watts found the performance video important to his performance history and Waterhouse had seen the performance live—warranting its inclusion. Had the annotation process not been concluded in early 2018, a video of Dialogue (DUO2015) from the Quiet Evening of Dance tour would have been important to consider.

7 The performers estimate this was a performance in the UK in summer 2015.

9 We use the terms movement and motion interchangeably in this article.

10 Forsythe and the dancers call this ‘counterpoint.’ Since they also describe the overall compositional practice within Duo counterpoint, we chose to differentiate terms: we use counterpoint in this article as the name for the overall compositional system, and concurrent motion to designate rhythmically related motion.

11 More generally, rhythms superimposed by chance (i.e. without the dancers’ shared rhythmical interaction) is a feature of some of Forsythe’s choreographies. This would have been classified as other had it occurred in Duo.

12 For our purposes, it was not necessary to divided the sequence into singular movements—chunks or short phrases sufficed. Initially Waterhouse annotated the building blocks using a consistent labeling scheme that mixed the dancers’ and her own terms (like ‘goldfinger’ and ‘umpadump’). These are shown in , Columns G and H. In the end, this was supplemented with numerical identifiers, as shown in and .

References

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1980/1990. In The Logic of Practice, translated by Richard Nice. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Brandstetter, Gabriele. 2000. “Still/Motion. Zur Postmoderne im Tanztheater.” In Bewegung im Blick. Beiträge einer theaterwissenschaftlichen Bewegungsforschung, edited by Claudia Jeschke and Hans-Peter Bayerdörfer, 122–136. Berlin: Vorwerk 8.

- Crompton, Sara. 2018. “A Different Focus.” In Performance Program. William Forsythe: A Quiet Evening of Dance. London: Sadler’s Wells Theater.

- Forsythe, William, and ZKM Karlsruhe 1999/2003. Improvisation Technologies: A Tool for the Analytical Dance Eye. DVD-ROM and Informational booklet. ZKM Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie Karlsruhe, Deutsches Tanzarchiv Köln SK Stiftung Kultur. Ostfildern: Hatja Cantz Verlag.

- Forsythe, William. 2019. Interview with Elizabeth Waterhouse on January 30, 2019.

- Forsythe, William, Maria Palazzi, Norah Zuniga Shaw, and Scott deLahunta. 2009. “Synchronous Objects for One Flat Thing, reproduced.” The Forsythe Company and The Ohio State University, http://synchronousobjects.osu.edu. Accessed December 15, 2020.

- Forsythe, William, and Norah Zuniga Shaw. 2009. “Introduction: The Dance.” Blog for the website Synchronous Objects for One Flat Thing, reproduced. The Ohio State University. https://synchronousobjects.osu.edu/blog/introductory-essays-for-synchronous-objects/index.html. Accessed July 15, 2020.

- Groves, Rebecca, Norah Zuniga Shaw, and Scott DeLahunta. 2007. “Talking About Scores: William Forsythe’s Vision for a New Form of Dance Literature.” In Knowledge in Motion: Perspectives of Artistic Research in Dance, edited by Sabine Gehm, Pirkko Husemann, and Katharina von Wilcke, 91–100. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- Johnson, Jill. 2018. Skype interview with Elizabeth Waterhouse on June 28, 2018.

- Johnson, Jill. 2020. Email to Elizabeth Waterhouse on September 12, 2020.

- Klein, Gabriele. 2015. “Die Logik der Praxis: Methodologische Aspekte einer praxeologischen Produktionsanalyse am Beispiel Das Frühlingsopfer von Pina Bausch.” In Methoden der Tanzwissenschaft: Modellanalysen zu Pina Bauschs “Le Sacre Du Printemps”, 2nd ed., edited by Gabriele Brandstetter and Gabriele Klein, 123–142. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- Laban, Rudolf von, and F. C. Lawrence. 1947/1974. Effort: Economy of Human Movement. London: Macdonald & Evans.

- Law, John. 2004. After Method: Mess in Social Science Research. London: Routledge.

- Leach, James, and Scott deLahunta. 2017. “Dance Becoming Knowledge: Designing a Digital ‘Body’.” Leonardo 50 (5): 461–467.

- Lepecki, André. 2013. “From Partaking to Initiating: Leadingfollowing as Dance’s (a-Personal) Political Singularity.” In Dance, Politics & Co-Immunity, edited by Gerald Siegmund and Stefan Hölscher, 21–38. Zürich: Diaphanes.

- Maletic, Vera. 2005. Dance Dynamics: Effort and Phrasing. Columbus, OH: Grade A Notes.

- Manning, Erin. 2009. Relationscapes: Movement, Art, Philosophy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Manning, Erin. 2013. Always More Than One: Individuation's Dance. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Massumi, Brian. 2002. Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Phelan, Peggy. 1993/2006. Unmarked: The Politics of Performance. London: Routledge.

- Reckwitz, Andreas. 2003 August. “Grundelemente einer Theorie sozialer Praktiken: Eine sozialtheoretische Perspektive.” Zeitschrift für Soziologie 32 (4): 282–301.

- Rittershaus, David, Anton Koch, Scott deLahunta, and Florian Jenett. 2019. “Recording Effect: A Case Study in Technical, Practical and Critical Perspectives on Dance Data Creation.” Proceedings of International Conference on Dance Data, Cognition and Multimodal Communication. Universidade Nova de Lisboa (in progress).

- Schachner, Adena. 2013. “The Origins of Human and Avian Auditory-Motor Entrainment.” Nova Acta Leopoldina NF 111 (380): 243–253.

- Schatzki, Theodore R, Karin Knorr Cetina, and Eike von Savigny, editors. 2006. The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory. London: Routledge.

- Schellow, Constanze. 2016. Diskurs-Choreographien: zur Produktivität des “Nicht” für die Zeitgenössische Tanzwissenschaft. Munich: epodium.

- Shaw, Nora Zuniga. 2011. “Synchronous Objects, Choreographic Objects, and the Translation of Dancing Ideas.” In Emerging Bodies: The Performance of Worldmaking in Dance and Choreography, edited by Gabriele Klein and Sandra Noeth, 207–222. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1wxt9q.18. Accessed July 28, 2020.

- Sulcas, Roslyn. 2011. “Watching the Ballett Frankfurt, 1988–2009.” In William Forsythe and the Practice of Choreography, edited by Steven Spier, 4–19. New York: Routledge.

- Thurner, Christina. 2015. “Prekäre Physische Zone: Reflexionen Zur Aufführungsanalyse Von Pina Bauschs Le Sacre Du Printemps.” In Methoden der Tanzwissenschaft: Modellanalysen zu Pina Bauschs “Le Sacre Du Printemps”, 2nd ed., edited by Gabriele Brandstetter and Gabriele Klein, 53–64. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- Tomic-Vajagic, Tamara. 2012. “The Dancer’s Contribution: Performing Plotless Choreography in the Leotard Ballets of George Balanchine and William Forsythe.” Dissertation. University of Roehampton.

- Waterhouse, Elizabeth 2017. “Entrainment und das zeitgenössische Ballett von William Forsythe” (“Entrainment and the Contemporary Ballets of William Forsythe”). Trans. Christoph Nöthlings. In DE/SYNCHRONISIEREN? Leben im Plural, edited by Gabriele Brandstetter, Kai van Eikels, and Anne Schuh, 197–219. Hannover: Wehrhahn Verlag.

- Waterhouse, Elizabeth. 2018. “In-Sync: Entrainment in Dance.” In The Neurocognition of Dance: Mind, Movement and Motor Skills. 2nd ed., edited by Bettina Bläsing, Martin Puttke, and Thomas Schack, 55–75. New York: Routledge.

- Waterhouse, Elizabeth. 2020. “As Duo: Thinking with Dance.” In Practical Aesthetics, edited by Bernd Herzogenrath, 183–194. London: Bloomsbury.

- Waterhouse, Elizabeth. Forthcoming. Processing Choreography: Thinking with William Forsythe’s “Duo”. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

- Waterhouse, Elizabeth, Riley Watts, and Bettina Bläsing. 2014. “Doing Duo – a Case Study of Entrainment in William Forsythe’s Choreography Duo.” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 8 (812): 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00812.

- Watts, Riley. 2017. Interview with Elizabeth Waterhouse on January 11, 2017.