Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether focusing on positive listening experiences improves hearing aid outcomes in experienced hearing aid users.

Design

The participants were randomised into a control or positive focus (PF) group. At the first laboratory visit, the Client-Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) questionnaire was administered followed by hearing aid fitting. The participants wore the hearing aids for three weeks. The PF group was asked to report their positive listening experiences via an app. During the third week, all the participants answered questionnaires related to hearing aid benefit and satisfaction. This was followed by the second laboratory visit where the COSI follow-up questionnaire was administered.

Study sample

Ten participants were included in the control and eleven in the PF group.

Results

Hearing aid outcome ratings were significantly better in the PF group in comparison to the control group. Further, COSI degree of change and the number of positive reports were positively correlated.

Conclusions

These results point to the importance of asking hearing aid users to focus on positive listening experiences and talk about them. The potential outcome is increased hearing aid benefit and satisfaction which could lead to more consistent use of the devices.

Introduction

A major problem of hearing loss treatment is that only a proportion of people who have hearing aids use them consistently. Dillon et al. (Citation2020) conducted an extensive survey demonstrating that 20% of hearing aid owners in Wales, UK do not use their hearing aids at all and 30% use them sporadically. Recent European Hearing Instrument Manufacturers Association (EHIMA) surveys showed similar trends, with 20–40% of hearing aid owners using their hearing aids less than four hours per day (EHIMA Citation2018-2022). Therefore, a number of investigations have focused on factors influencing hearing aid satisfaction and acceptance with the goal of contributing to the improvement of hearing aid outcomes (Jerram and Purdy Citation2001; Kim et al. Citation2022; Kochkin Citation2010; Meyer et al. Citation2014; Neeman et al. Citation2012; Wong, Hickson and McPherson Citation2009). These investigations all pointed to experienced benefit as the key driver of hearing aid use and satisfaction. As such, the focus should be placed on improving the perceived hearing aid benefit.

A growing body of evidence has indicated that the process of intervention and counselling can have important effects on hearing aid benefits, independent of the actual intervention itself (Bentler et al. Citation2003; Dawes et al. Citation2011, Citation2013; Rakita, Goy, and Singh Citation2022). Recently, Rakita, Joy, and Singh (Citation2022) showed that communication of a positive narrative about hearing aids before hearing aid fitting led to a better speech-in-noise performance on the QuickSIN as compared with the performance following the negative or neutral narrative conditions using the same pair of hearing aids. Similarly, in an earlier study, Dawes and colleagues (Citation2011) compared acoustically equivalent hearing aids labelled as either “new” or “conventional” and showed an effect favouring the “new” hearing aid on speech-in-noise performance as well as on subjective ratings of hearing aid performance. In a later study, the authors confirmed that these placebo effects are reliable (Dawes et al. Citation2013). Even before that, Bentler et al. (Citation2003) showed that individuals report more benefits from hearing aids when devices are described as consisting of “digital” technology rather than “analog” technology. All these studies show that non-audiological factors can influence hearing aid outcomes. The studies discuss their results in relation to the narratives we tell hearing aid users and the need to control for potential placebo effects in investigations involving hearing aids. However, there is also a potential benefit in the fact that such non-audiological factors affect hearing aid experiences.

What if hearing aid users are asked to focus on positive listening experiences in everyday life and talk about them? When encouraged to focus on positive listening experiences, hearing aid users may be more likely to realise in which situations hearing aids truly help them and consequently appreciate their hearing aids more. Without encouragement towards a positive focus, such benefits can be overshadowed by difficult experiences, which can negatively influence a person’s overall hearing aid satisfaction. This is the so-called “negativity bias” where a negative event is subjectively more potent and of higher salience than a positive event of equal objective magnitude (Rozin and Royzman Citation2001). A recent study showed that participants who learned to internalise beneficial experiences (repeatedly sustaining a focus on emotionally positive experiences) significantly improved cognitive resources, positive emotions, negative emotions, and total happiness (Hanson et al. Citation2021). The authors state that “repeatedly applying engagement factors to experiences of a particular psychological resource may help develop it as a trait, which in turn could foster more experiences of it and thus more opportunities to reinforce it, in a positive cycle.” In other words, internalising beneficial experiences has the potential to overcome the ‘negativity bias’. If this is true, then repeatedly focusing on positive listening experiences with hearing aids could lead to an increased number of such experiences and ultimately to a better overall hearing aid experience.

To date, there are no studies that specifically investigate how repeatedly focusing on positive listening experiences with hearing aids may affect hearing aid outcomes. However, a study where participants were asked to take daily pictures documenting real-world positive and negative hearing aid experiences indicated that there could be a relationship (Saunders et al. Citation2019). For example, one study participant stated that while she got her hearing aids to help with speech-in-noise situations, due to being in the study, she became aware of how much she enjoys the outdoor sounds as well. Consequently, she started using her hearing aids more consistently. Another participant reported that having spent time trying to understand where his hearing aids were and were not helpful, he realised that he should wear them all the time, rather than sporadically as he had been before participating in the study.

Hence, there is some indication that focusing on and talking about positive listening experiences with hearing aids can lead to an overall better hearing aid experience. The purpose of the current study was to investigate whether focusing on positive listening experiences in everyday life does indeed improve the perceived hearing aid benefit and satisfaction in experienced hearing aid users.

Methods

Ethical clearance for conducting the study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Capital Region of Denmark (case no. H-18056647). The study was not registered with a trial registry before commencing.

Study design

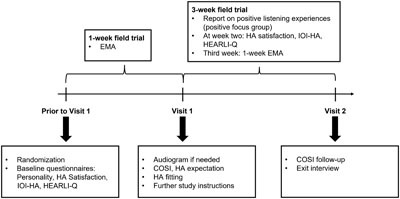

This was a randomised, single-blind, parallel-arm study. The participants were blinded to the true purpose of the study and the fact that they belonged to one of the two groups (Control or Positive Focus). All the participants were instructed that the purpose of the study was to learn more about hearing aid users’ experiences with hearing aids so that we can better understand the behaviour and needs of hearing aid users. The study flow is depicted in . Once the participants were randomised into the study, they were instructed to download and install the MyHearingExperience app (Lenox UG, Herrsching, Germany) which is available for iOS and Android. The study consisted of a one-week baseline period, a three-week post-fitting period and two laboratory visits. Each part of the experiment is described in detail below.

Participants

Ten participants were randomised into a Control group (64 ± 8 years of age, 7 males, 3 females) and eleven into a Positive Focus (PF) group (68 ± 7 years of age, 8 males, 3 females). An extra participant in the PF group was included. This was because one participant became sick after starting the trial and was replaced. But, once the original participant was healthy again, he contacted us to ask if he could rejoin the trial, and we permitted it. All the participants were experienced hearing aid users (≥1 year). Other inclusion criteria were: sensorineural hearing loss within the hearing aid’s fitting range, fluency in Danish, and being an experienced smartphone and app user. The exclusion criteria were: Severe cognitive impairment that would preclude the ability to perform the necessary tasks, inability for the participants to travel to the laboratory during the study period, and complex hearing disorders such as Ménière’s disease. The participants were recruited from a database of participants by conducting a search for the ones who matched the inclusion criteria and were not commited to other studies. The database randomises the order of the participants who fit these criteria, such that they are not alphabetically or numerically sorted. The participants were then contacted, starting from the first one on the list, until the desired sample size was reached. The participants were informed about the study orally and in writing. Before the trial commenced, the participants gave their informed consent in writing.

Baseline period

Each participant was provided with a unique study log-in code for the MyHearingExperience app via e-mail and instructed to fill out the following baseline questionnaires available in the app:

Big Five Inventory (BFI) Personality (John, Donahue, and Kentle Citation1991; John, Naumann, and Soto Citation2008) – 44-item inventory that measures an individual on the Big Five Factors (dimensions) of personality: extraversion vs introversion, agreeableness vs antagonism, conscientiousness vs lack of direction, neuroticism vs emotional stability, and openness vs closedness to experience. The English version of the questionnaire has high reliability and good external validity (Rammstedt and John Citation2007). The questionnaire was internally translated to Danish using the forward-backwards translation approach: three bi-lingual people independently translated the English BFI to Danish. Then, they compared the individual translations, discussed any discrepancies, and agreed on a common version. Two further bi-lingual people then individually translated the agreed-upon Danish questionnaire to English and compared their translations for any discrepancies before agreeing on the common version. Finally, the forward and backward translators met to compare the original English version of the BFI to the back-translated one and addressed any discrepancies that may have given rise to updates of the Danish version of the questionnaire. The Danish questionnaire resulting from this meeting was the final one, and the one used in the study.

A question about hearing aid satisfaction: How satisfied are you with your hearing aids? – Slider scale between 1 and 10 where 1 = not at all satisfied and 10 = extremely satisfied. The overall satisfaction question was asked to get an assessment of the overall subjective hearing aid experience that is not confined to specific scenarios.

International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids (IOI-HA) (Cox et al. Citation2000) -– a seven-item questionnaire evaluating the effectiveness of hearing aid treatment. The questionnaire is widely used in hearing research and its items are relevant for answering our primary research question. The data derived from the Danish IOI-HA holds general validity and reliability and is psychometrically comparable to data obtained from other validated translations (Jespersen, Bille, and Legarth Citation2014). As the IOI-HA items have high internal consistency (Jespersen, Bille, and Legarth. Citation2014), the combined score is calculated as the sum of the ratings of individual items to arrive at one value that is easy to interpret. Although this is in line with a number of published studies (Goy et al. Citation2018; Saunders et al. Citation2016; Wu et al. Citation2016), whether it is appropriate to sum up the individual IOI-HA items into one composite score is a matter of some debate (Leijon et al. Citation2021). Leijon et al. state that “…using only the conventional overall scales may lead to incorrect conclusions in some cases if the difference is small.” For the sake of comparison, we also report statistical analysis on the IOI-HA scores recoded from ordinal to interval as recommended by Leijon et al.

Hearing-Related Lifestyle Questionnaire (HEARLI-Q) (Lelic et al. Citation2022) – a questionnaire based on the Common Sound Scenarios (CoSS) framework (Wolters et al. Citation2016) to assess an individual’s hearing-related lifestyle. HEARLI-Q is the only existing questionnaire that assesses hearing-related lifestyle, hearing demands, hearing difficulties, and hearing aid satisfaction in everyday listening situations. The questionnaire includes 23 listening situations that respondents are asked to rate on four dimensions: frequency of occurrence, the importance to hear well, difficulty to hear, and hearing aid satisfaction. Based on the ratings of individual listening situations, four outcomes are derived: the richness of hearing-related lifestyle, hearing demand, hearing difficulty and hearing aid satisfaction. The questionnaire outcomes have excellent day-to-day reliability and good-to-excellent longer-term reliability (Lelic et al. Citation2022).

The day after the initial log-in to the MyHearingExperience app, the participants were prompted to answer an Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) questionnaire every two hours between 9:00 and 21:00 over seven days. The EMA questionnaire asked about location, listening task, hearing difficulty and hearing aid satisfaction. EMA allowed us to tap into momentary hearing aid satisfaction in various listening situations and is not subject to memory bias. The specific EMA questions and response alternatives are outlined in .

Table 1. EMA questions and response alternatives.

All the questions about hearing aid experience during the baseline period related to participants’ experience with their own hearing aids. The purpose of the baseline questionnaires was to compare the two groups at baseline to confirm that they were balanced across different parameters that can influence the experienced benefit and satisfaction with the study hearing aids. In case any imbalances were observed, they were controlled for in the analysis.

Visit 1

After the baseline period, the participants came for the first laboratory visit at WS Audiology in Lynge, Denmark. During this visit, a new audiogram was obtained if the one on file was older than one year. As hearing aid expectation has been shown to influence hearing aid outcomes (Ferguson, Woolley, and Munro Citation2016; Wong, Hickson, and McPherson Citation2003), the participants were asked about overall hearing aid expectation (Gatehouse Citation1994) before being fitted: “If you were to wear this hearing aid, how much do you think it would help with your hearing?” and response alternatives were “a) no real help at all; b) some help but not very much; c) a great help; d) I would expect this hearing aid to return my hearing to normal”.

Then the Client-Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) questionnaire (Dillon et al. Citation1997) was administered, where the participants were asked to identify up to five most critical situations where they would like to improve their hearing. For each COSI situation, the participants were asked to rate their hearing aid expectation with the same response alternatives as for the question about general hearing aid expectation.

Participants were then fitted with Widex MOMENT 440 receiver-in-canal (RIC) hearing aids by an experienced audiologist who did all the fittings for this study. The hearing aids were fitted to the participant’s hearing loss using Compass GPS (version 4.3). The fitting was performed according to the Widex recommendations for in-situ measurements, where the feedback test and Sensogram are conducted to account for the individual acoustic properties of the ear canal (Kuk Citation2012). Receivers and ear tips were selected based on the fitting software’s recommendation. Fine-tuning, if needed, was done based on the audiologist’s clinical experience, but the overall fine-tuning of gain was not permitted to exceed ± 6 dB and fine-tuning in specific frequency bands was not permitted to exceed ± 3 dB. This is within the limits of acceptable deviations from fit-to-target according to the British Society of Audiology (Citation2018). The default feature settings were used, and no special programs were added. The participants could use the MOMENT app for streaming. This app has an option for creating personalised programs, but the participants were instructed not to use the app for this purpose.

Following the fitting, further study instructions were given. All the participants were given a new unique log-in to the MyHearingExperience app, which included scheduling of the post-fitting questionnaires. All the participants were instructed to wear the study hearing aids for the next three weeks and told that they would be prompted by the app to answer questionnaires after two weeks. Additionally, the PF group was instructed to focus on positive listening experiences and report on them. They could report by clicking on the smiley emoticon (only visible to the PF group) in the app. The specific instruction was: “I am very interested to hear about situations where the study hearing aids are helping you. Please use the app to report every time you encounter a positive listening experience. These types of situations could, for example, be: great communication at a party, hearing the sounds of crickets in the forest, or other types of situations where your hearing is noticeably good. It could also be situations in which you notice the hearing aids are helping you and where you notice your hearing is better than before.” The positive reports were always self-initiated. Some participants in the PF group found it odd that they were not asked to report negative experiences. In such cases, we explained that in this particular study, we were interested to hear about the situations in which hearing aids were truly helping them.

The participants were given an opportunity to ask any questions before leaving the laboratory. Thereafter, the post-fitting field trial commenced.

The post-fitting field trial

During the three-week field trial, the PF group actively reported – via the MyHearingExperience app – each time they had a positive listening experience. After two weeks, all the participants were prompted by the app to answer the hearing aid satisfaction question, IOI-HA and HEARLI-Q.

The day after this prompt, the participants started a new EMA period. Again, they were prompted to answer the EMA questionnaire () every two hours between 9:00 and 21:00 for a period of one week. This EMA trial lasted for the final week of the post-fitting field trial.

The first questionnaires were administered at two-weeks post-fitting because this is an appropriate period for an experienced hearing aid user to get used to the sound of a new hearing aid and the goal was to test whether there is a relatively short-term effect of “positive focus” on hearing aid outcomes. The one-time questionnaires were administered prior to EMA period, such that these responses are not influenced by daily EMA reporting.

During the field trial, we checked online whether reports were coming in as expected. If a participant in the PF group did not report any positive experiences in three days, the audiologist followed up by calling the participant. The audiologist asked how it was going and why no positive reports had been given. Then, the participants were encouraged to pay attention to positive listening experiences. For participants in both groups, there was a follow-up if they did not answer the prompted questionnaires or if they only provided sporadic EMA reporting.

Visit 2

After the three-week field trial, the participants came for the second laboratory visit. During this visit, the follow-up COSI questionnaire was administered. The critical situations that participants indicated they would like to improve were revisited, and the participants were asked to rate the “degree of change” and “final ability” for each situation. The response alternatives defined by COSI for “degree of change” were: worse, no difference, slightly better, better, and much better; and for “final ability”: a person can hear hardly ever (10%), occasionally (25%), half the time (50%), most of the time (75%), and almost always (95%). Then, a semi-structured exit interview was conducted, during which the participants were asked about their general experiences with the trial. At the end of the visit, the participants returned the study hearing aids.

Data analysis

The study sample size was 21 participants. Power analyses were done prior to study initiation. Based on 1000 simulations of overall hearing aid satisfaction data with mean = 7.8 and standard deviation = 1.5, ten participants in each group would enable difference detection of two scale points with a power of approximately 80% using regression analysis. The mean and standard deviation were based on a pilot study where 20 experienced hearing aid users were asked to rate their satisfaction with hearing aids on a 10-point scale where 1=‘not at all satisfied’ and 10=‘extremely satisfied’.

The primary endpoint of the study was to evaluate whether focusing on positive listening experiences improves hearing aid outcomes, as evidenced by ratings of hearing aid satisfaction, IOI-HA, COSI degree of change and final ability. A secondary endpoint was to assess whether the hearing aid outcome scores are correlated to the number of positive reports submitted by the PF group.

Baseline data between the two groups were compared to ensure that the two groups were balanced. Age, hearing loss, BFI scores, HEARLI-Q outcomes, overall hearing aid satisfaction with own hearing aids, combined IOI-HA score, and EMA compliance were compared using ANOVA. The data subjected to ANOVA were visually inspected to ensure that they fit a normal distribution. If not, the ladder of powers was applied in order to transform the data into normally distributed. Gender and own hearing aid data (number of Widex hearing aid users) were compared using a test of proportions. Hearing aid experience was compared by the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. EMA data on location and listening task were compared using χ2 to check whether the distribution of responses was significantly different between the two groups. EMA data on hearing aid satisfaction were compared using mixed-effects linear regression with random effects on participant ID. Hearing aid expectations were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Any imbalances in baseline individual parameters were controlled for in the analysis of the post-fitting data.

Linear regression analyses were conducted to assess the effect of PF on overall hearing aid satisfaction, combined IOI-HA and hearing aid satisfaction on HEARLI-Q scale at two weeks. In addition to group (PF or control), HEARLI-Q hearing demand and HEARLI-Q hearing difficulty were included as covariates where HEARLI-Q satisfaction was the dependent variable. Hearing-related lifestyle was also part of the original model. However, due to a high variance inflation factor (VIF = 5.24), indicating high collinearity in the model, this variable was taken out. Hearing-related lifestyle is incorporated in hearing demand as the occurrence score is included in the calculation of hearing demand (Lelic et al. Citation2022).

Mixed-effects linear regression was conducted to assess the effect of PF on satisfaction on EMA scale during the third week. In addition to group (PF or control), hearing difficulty was included as a covariate in the model. Mixed-effects linear regression was also conducted to assess the effect of PF on COSI degree of change at three weeks. In addition to group (PF or control), hearing aid expectation for each critical situation was included as a covariate in the model.

For all the linear regression analyses, the residuals were visually inspected to ensure they fit an approximately normal distribution.

Mixed-effects ordered logistic regression was conducted to assess COSI final ability at three weeks. In addition to group (PF or control), hearing aid expectation for each critical situation was included as a covariate in the model. Ordered logistic regression was done in this case because data were highly skewed, and the responses were mainly clustered in the top three categories.

χ2 test was conducted on post-fitting EMA data collected during the third week to compare the distribution of location and listening task between the two groups.

For the PF group, Spearman’s correlation coefficients were calculated between each hearing aid outcome rating and the number of submitted positive reports during the three weeks to assess whether there is a relationship between the two variables. For EMA and COSI ratings, averages within participants were used for correlation analyses.

All the statistical analyses were done in Stata (v. 15, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

The two groups were comparable across most baseline characteristics, except for IOI-HA scores where the PF group scored higher than the control group (). Hence, when analysing the post-fitting IOI-HA outcomes, the baseline IOI-HA scores were controlled for.

Table 2. Comparison of baseline characteristics between the two groups.

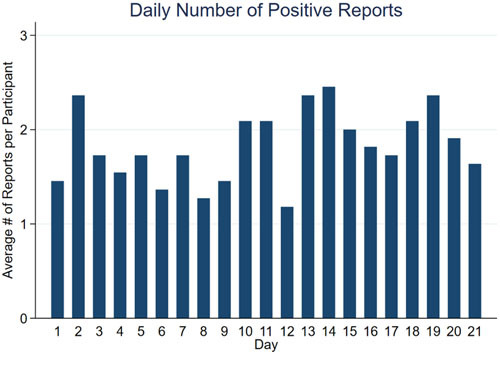

The participants in the PF group reported an average of 38 (range: 11–75) positive listening experiences over the three weeks. Follow-ups were only necessary in two cases due to participants’ misunderstanding that they should only report their positive listening experiences until the post-fitting questionnaires were prompted on day 14. The data showed no trend towards significant changes in the number of daily positive reports as the trial period progressed (see ). The types of positive listening experiences varied between reports and participants, but some examples are: “Watching TV with others. Hear everything”, “The forest sounds completely different. Interesting”, “Was down with garbage bags. Nice to hear the wind howling”, “Eating lunch with several. Separation of sounds is good”, “Many gathered in the club room. Prize giving for racing, speeches go through clearly and the background murmur is subdued”, “Door open. I can hear traffic and the rain”, “Walking around the zoo and talking to my husband. Better speech comprehension. There is some background talk but not disturbing”.

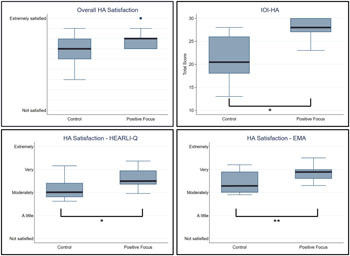

The four measures of hearing aid outcomes during the third week post fitting are shown in and the corresponding regression results are shown in . The overall hearing aid satisfaction was not significantly different between the two groups. IOI-HA scores remained significantly higher in the PF group after the analysis was controlled for the baseline IOI-HA scores. The satisfaction scores on the HEARLI-Q scale were significantly higher in the PF group when hearing demand and hearing difficulty were held constant. Hearing difficulty was also a significant contributor to hearing aid satisfaction, where less hearing difficulty was related to higher hearing aid satisfaction. When rating hearing aid satisfaction for the 23 listening situations on the HEARLI-Q scale, two participants in the control group and three in the PF group have indicated that they do not wear their hearing aids in the following situation: “Relaxing in a quiet room at home (for instance while reading or doing a crossword puzzle)”.

Figure 3. Two weeks post-fitting hearing aid outcome scores on the four scales. The EMA satisfaction ratings were averaged within each individual prior to box plot visualisation, in order to give each participant the same weight. The significant differences are indicated by *(p <.05) and **(p <.01).

Table 3. Regression analyses results.

The EMA compliance rate was on average 83% (SD: 18) in the control group and 74% (SD: 15) in the PF group. The control group provided satisfaction ratings in 91% of the group-total EMA reports and the PF group provided satisfaction ratings in 94% of the group-total EMA reports, that is, the participants reported they did not wear their hearing aids in the remaining situations. The reports where the hearing aids were not worn are attributed to nine participants in the control group (min: 1, max: 12 reports per participant) and five participants in the PF group (min: 1, max: 11 reports per participant). The type of situations where the hearing aids were not worn were similarly distributed between groups and majority of situations were in home environments during passive listening with little to no hearing difficulty (Supplemental Table 1). The satisfaction scores on the EMA scale were significantly higher in the PF group when hearing difficulty was held constant. As on the HEARLI-Q scale, hearing difficulty was a significant predictor of hearing aid satisfaction, where less hearing difficulty is related to higher hearing aid satisfaction. The distributions of location (χ2 (3, N = 21) = 6.2, P = 0.10) and listening task (χ2 (5, N = 21) = 7.3, P = 0.20) were similar between the two groups.

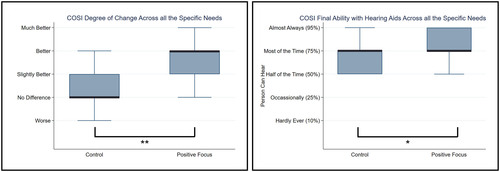

A median of four critical situations per participant were given for the COSI questionnaire at Visit 1. The most common specific needs for improvement were: “large gatherings” (12 participants − 6 in each group), “understanding TV/radio at normal volume” (12 participants − 6 in each group) and “family dinner” (7 participants − 4 in control, 3 in PF group). Otherwise, the critical situations varied between individuals. The COSI ratings from the second visit are shown in and the outcomes of the mixed-effects regression analyses are shown in . Both the degree of change and final ability were significantly higher in the PF group when hearing aid expectation for improvement in these situations was held constant. Hearing aid expectation for individual critical situations had no effect on any of the COSI outcomes.

Figure 4. COSI ratings at the second visit. The median of COSI ratings was calculated within each individual prior to box plot visualisation, in order to give each participant the same weight. The significant differences are indicated by *(p <.05) and **(p <.01).

Correlation analyses between the number of submitted positive experiences and hearing aid outcome ratings are shown in . There was a significant positive relationship between COSI degree of change and the number of submitted positive reports. In other words, participants who submitted more positive listening experiences tended to have higher degree of change ratings on the COSI scale. None of the other outcomes were correlated with the number of positive reports.

Table 4. Correlation analyses between the number of submitted positive experiences and hearing aid outcome ratings.

At the exit interview, when the participants were asked “How did it go with the trial?”, the participants in the control group talked about their general experience with the questionnaires, MyHearingExperience app, and the number of prompts. Six out of the eleven participants in the PF group, however, reflected on their positive experiences with hearing aids ().

Table 5. Participant responses to “How did it go with the trial?” at the exit interview.

Discussion

The results of the current study indicate that focusing on positive listening experiences improves the perceived hearing aid benefit and satisfaction in experienced hearing aid users, as evidenced by IOI-HA, HEARLI-Q, EMA and COSI questionnaires. These findings are in line with previous research that showed that non-audiological interventions can influence hearing aid outcomes (Bentler et al. Citation2003; Dawes, Hopkins, and Munro Citation2011, Citation2013; Rakita et al. Citation2022). In contrast to the earlier studies, rather than telling narratives about the hearing aid to affect the outcome, we asked the participants to repeatedly focus on specific hearing aid experiences (positive listening) in their everyday lives and report when they experienced such an event. The positive effect of this simple task is further evidenced at the exit interviews, when the participants were asked about their experience during the trial. The control group talked about the experiment itself, MyHearingExperience app, the prompts, and the questionnaires – not a single participant mentioned anything about the hearing aids. Majority of the participants in the PF group, on the other hand, talked about their pleasant experiences with the hearing aids. It seems that, by reporting their positive listening experiences, light was shed on the situations where hearing aids provide benefit, which in turn led to increased satisfaction and an overall enjoyable experience with hearing aids. If the experienced hearing aid benefit is a key driver for hearing aid satisfaction and acceptance (Jerram and Purdy Citation2001; Kim et al. Citation2022; Kochkin Citation2010; Meyer et al. Citation2014; Neeman et al. Citation2012; Wong, Hickson, and B. McPherson Citation2009), then asking hearing aid users to talk about their positive listening experiences could be one strategy to help achieve positive hearing aid outcomes.

Kirkwood (Citation2005) conducted a survey where 674 hearing aid dispensers were asked to share their views on factors determining a client’s satisfaction with hearing aids. Only 6% of the respondents reported hearing aids as the most important factor leading to a successful fitting. On the other hand, 39% reported counselling as the most crucial. Asking a hearing aid user to focus on positive listening experiences after hearing aid fitting and using these experiences as basis for dialogue at follow-up visits, could be a more focused part of the counselling process. This collaborative approach can help improve hearing aid acceptance. If the hearing aid user sticks to the task of wearing their hearing aids for the sake of reporting and working together with their hearing care professional, the process could facilitate hearing aid acclimatisation, potentially contributing to higher satisfaction (Neeman et al. Citation2012). Adherence to the task of focusing on positive listening experiences could also be an explanation for fewer participants in the PF group reporting EMA situations in which they did not wear their hearing aids. The positive reports can be submitted via an app as done in this study, or in a paper-pen diary. For a smartphone/smartwatch user, the convenience of an app solution is that it is easily accessible at any moment they wish to send a report and there is a sense of sharing the experience with someone while reporting. Sharing positive experiences has been shown to have a greater impact on positive emotion benefits such as happiness and life satisfaction, compared to simply writing these experiences down in a diary (Lambert et al. Citation2012).

We expected to see a positive relationship between the number of submitted positive reports and hearing aid outcome ratings, and we observed such a relationship with COSI degree of improvement. It is unclear whether the higher degree of improvement is due to greater reporting, or whether participants who are more satisfied report more frequently and hence have higher degree of improvement ratings. If the latter is true, one may expect correlations with ratings on the other scales to be affected as well. On the other hand, the significant correlation we observed is reasonable as the situations identified for COSI are the situations that are personally important for the participant to improve their hearing in. These are likely also the situations that regularly occur in the participant’s life and the ones where they looked for positive listening experiences with the study hearing aids.

Overall hearing aid satisfaction rating is the only outcome measure where there was no significant difference between the two groups. One explanation could be that it is not clearly defined what the participants should rate when rating overall satisfaction. Their interpretation of the question could vary greatly, and they could use different criteria when judging whether they are satisfied with the hearing aid (Wong, Hickson, and McPherson Citation2003). For example, participants might think about physical fit, streaming possibilities, sound quality, or something else when rating their overall satisfaction. In contrast, IOI-HA, HEARLI-Q, COSI and EMA all ask about hearing aid satisfaction or benefit in specific situations and the likelihood is higher that participants interpret these questions more similarly.

It can be argued that participants in the PF group scored higher on the measured hearing aid outcomes simply due to greater involvement through more interaction with the app (Ross Citation2020). However, the responses at the exit interview, where only the participants in the PF group talked about the hearing aids, would indicate that focusing on positive listening experiences did bring about awareness of hearing aid benefit that was not observed to the same extent in the control group. It can also be argued that due to being instructed to report only positive experiences, the participants in the PF group became conditioned to talk about the positive experiences. However, this is not mutually exclusive to having a better overall experience. Presumably, the way people answer questionnaires is reflective of their experience. When participants were asked to rate their experienced benefit and satisfaction with the study hearing aids, the PF group scored higher. This is exactly what the PF intervention aims to do: bring awareness to positive listening experiences by focusing on such experiences and in turn improve the overall hearing aid experience.

Focusing on positive listening experiences had a clear positive effect on hearing aid outcomes in this study. In terms of clinical implications, if hearing aid users are asked to focus on such experiences, to report them and talk about them, they may be more likely to realise in which situations the hearing aids are providing them with benefit. This in turn can lead to a better overall experience with the devices and a more consistent wear of devices. A secondary advantage of more satisfied hearing aid users is a possible “domino effect”. Hearing aid users who are satisfied with their devices are more likely to recommend them to their family and friends (Kochkin Citation2010) and this has the potential to lead to an increase in hearing aid uptake.

Here, we showed a relatively short-term effect of focusing on positive listening experiences on the perceived hearing aid benefit and satisfaction in a small sample of experienced hearing aid users. It should be noted the study participants were recruited from an in-house participant database, and they may not be representative of an average hearing aid user or a naïve study participant. The participants in this study could be more likely to adhere to the task of consistent self-initiated reporting of positive listening experiences. Even if that may be the case, the contrast between the two groups, if the PF group does adhere to the task, remains. The effect on long term outcomes in a larger sample, as well as hearing aid outcomes in first-time users/naïve study participants still needs to be explored. Currently, we are running a longitudinal study in first-time hearing aid users to investigate this.

Conclusion

The study showed that focusing on positive listening experiences improves the perceived hearing aid benefit and satisfaction in experienced hearing aid users. These results point to the importance of asking hearing aid users to focus on positive listening experiences and talk about them. This technique could be utilised in clinics to improve hearing aid users’ experience with hearing aids.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14.9 KB)Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Anja Kofoed Pedersen, Laura Winther Balling, Eline Borch Petersen and Marianne Sonne for translating the Big Five Inventory questionnaire to Danish. The authors further thank Laura Winther Balling for her valuable input on the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

All authors are employees of WS Audiology.

References

- Bentler, R. A., D. P. Niebuhr, T. A. Johnson, and G. A. Flamme. 2003. “Impact of digital labeling on outcome measures.” Ear and Hearing, 24 (3): 215–224. doi:10.1097/01.AUD.0000069228.46916.92.

- British Society of Audiology. 2018. Guidance on the verification of hearing devices using probe microphone measurements. http://www.thebsa.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Procedure-for-Processing-Documents.pdf

- Cox, R., M. Hyde, S. Gatehouse, W. Noble, H. Dillon, R. Bentler, D. Stephens, S. Arlinger, L. Beck, D. Wilkerson, et al. 2000. “Optimal outcome measures, research priorities, and international cooperation.” Ear and Hearing 21 (4 Suppl):106S–115S. doi:10.1097/00003446-200008001-00014.

- Dawes, P., R. Hopkins, and K. J. Munro. 2013. “Placebo effects in hearing-aid trials are reliable.” International Journal of Audiology 52 (7): 472–477. doi:10.3109/14992027.2013.783718.

- Dawes, P., S. Powell, and K. J. Munro. 2011. “The placebo effect and the influence of participant expectation on hearing aid trials.” Ear and Hearing 32 (6): 767–774. doi:10.1097/AUD.0b013e3182251a0e.

- Dillon, H., J. Day, S. Bant, and K. J. Munro. 2020. “Adoption, use and non-use of hearing aids: a robust estimate based on Welsh national survey statistics.” International Journal of Audiology 59 (8): 567–573. doi:10.1080/14992027.2020.1773550.

- Dillon, H., A. James, and J. Ginis. 1997. “Client oriented scale of improvement (COSI) and its relationship to several other measures of benefit and satisfaction provided by hearing aids.” Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 8 (1): 27–43.

- EHIMA 2018-2022. EuroTrak Country Market Surveys. https://www.ehima.com/surveys/

- Ferguson, M., A. Woolley, and K. J. Munro. 2016. “The impact of self-efficacy, expectations, and readiness on hearing aid outcomes.” International Journal of Audiology 55: S34–S41. doi:10.1080/14992027.2016.1177214.

- Gatehouse, S. 1994. “Components and determinants of hearing aid benefit.” Ear and Hearing 15 (1): 30–49. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199402000-00005.

- Goy, H., M. K. Pichora-Fuller, G. Singh, and F. A. Russo. 2018. “Hearing aids benefit recognition of words in emotional speech but not emotion identification.” Trends in Hearing 22: 2331216518801736. doi:10.1177/2331216518801736.

- Hanson, R., S. Shapiro, E. Hutton-Thamm, M. R. Hagerty, and S. K.p. 2021. “Learning to learn from positive experiences.” The Journal of Positive Psychology 18 (1): 142–153. doi:10.1080/17439760.2021.2006759.

- Jerram, J. C., and S. C. Purdy. 2001. “Technology, expectations, and adjustment to hearing loss: predictors of hearing aid outcome.” Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 12 (2): 64–79.

- Jespersen, C. T., M. Bille, and J. V. Legarth. 2014. “Psychometric properties of a revised Danish translation of the international outcome inventory for hearing aids (IOI-HA).” International Journal of Audiology 53 (5): 302–308. doi:10.3109/14992027.2013.874049.

- John, O. P., E. M. Donahue, and R. L. Kentle. 1991. The Big Five Inventory–Versions 4a and 54. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research.

- John, O. P., L. P. Naumann, and C. J. Soto. 2008. “Paradigm shift to the integrative Big Five trait taxonomy: history, measurement, and conceptual issues.” In O. P.John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 114–158). New York: Guildford Press.

- Kim, G., Y. S. Cho, H. M. Byun, H. Y. Seol, J. Lim, J. G. Park, and I. J. Moon. 2022. “Factors influencing hearing aid satisfaction in South Korea.” Yonsei Medical Journal, 63 (6): 570–577. doi:10.3349/ymj.2022.63.6.570.

- Kirkwood, D. H. 2005. “Dispenser surveyed on what leads to patient satisfaction.” The Hearing Journal 58 (4): 19–26. doi:10.1097/01.HJ.0000286603.76729.a2.

- Kochkin, S. 2010. “MarkeTrak VIII: consumer satisfaction with hearing aids is slowly increasing.” The Hearing Journal 63 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1097/01.HJ.0000366912.40173.76.

- Kuk, F. 2012. “In-situ thresholds for hearing aid fittings.” Hearing Review 19 (11): 26–30.

- Lambert, N. M., A. M. Gwinn, R. F. Baumeister, A. Strachman, I. J. Washburn, S. L. Gable, and F. D. Fincham. 2012. “A boost of positive affect: the perks of sharing positive experiences.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 30 (1): 24–43. doi:10.1177/0265407512449400.

- Leijon, A., H. Dillon, L. Hickson, M. Kinkel, S. E. Kramer, and P. Nordqvist. 2021. “Analysis of data from the international outcome inventory for hearing aids (IOI-HA) using Bayesian item response theory.” International Journal of Audiology 60 (2): 81–88. doi:10.1080/14992027.2020.1813338.

- Lelic, D., F. Wolters, P. Herrlin, and K. Smeds. 2022. “Assessment of hearing-related lifestyle based on the common sound scenarios framework.” American Journal of Audiology, 31 (4): 1299–1311. doi:10.1044/2022_AJA-22-00079.

- Meyer, C., L. Hickson, A. Khan, and D. Walker. 2014. “What is important for hearing aid satisfaction? Application of the expectancy-disconfirmation model.” Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 25 (7): 644–655. doi:10.3766/jaaa.25.7.3.

- Neeman, R. K., C. Muchnik, M. Hildesheimer, and Y. Henkin. 2012. “Hearing aid satisfaction and use in the advanced digital era.” The Laryngoscope 122 (9): 2029–2036. doi:10.1002/lary.23404.

- Rakita, L., H. Goy, and G. Singh. 2022. “Descriptions of hearing aids influence the experience of listening to hearing aids.” Ear and Hearing 43 (3): 785–793. doi:10.1097/AUD.0000000000001130.

- Rammstedt, B., and O. P. John. 2007. “Measuring personality in one minute or less: a 10-item short version of the big five inventory in English and German.” Journal of Research in Personality 41 (1): 203–212. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2006.02.001.

- Ross, F. 2020. “Hearing aid accompanying smartphone apps in hearing healthcare. A systematic review.” Applied Medical Informatics 42 (4): 189–199.

- Rozin, P., and E. B. Royzman. 2001. “Negativity bias, negativity dominance, and ontagion.” Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5 (4): 296–320. doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0504_2.

- Saunders, G. H., L. K. Dillard, M. T. Frederick, and S. C. Silverman. 2019. “Examining the utility of photovoice as an audiological counseling tool.” Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 30 (5): 406–416. doi:10.3766/jaaa.18034.

- Saunders, G. H., M. T. Frederick, S. C. Silverman, C. Nielsen, and A. Laplante-Levesque. 2016. “Health behavior theories as predictors of hearing-aid uptake and outcomes.” International Journal of Audiology 55 (Suppl 3): S59–S68. doi:10.3109/14992027.2016.1144240.

- Wolters, F., K. Smeds, E. Schmidt, E. K. Christensen, and C. Norup. 2016. “Common Sound Scenarios: a context-driven categorization of everyday sound environments for application in hearing-device research.” Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 27 (7): 527–540. doi:10.3766/jaaa.15105.

- Wong, L. L., L. Hickson, and B. McPherson. 2003. Hearing aid satisfaction: what does research from the past 20 years say? Trends in Hearing 7 (4): 117–161. doi:10.1177/108471380300700402.

- Wong, L. L. N., L. Hickson, and B. McPherson. 2009. “Satisfaction with hearing aids: a consumer research perspective.” International Journal of Audiology 48 (7): 405–427. doi:10.1080/14992020802716760.

- Wu, Y. H., H. C. Ho, S. H. Hsiao, R. B. Brummet, and O. Chipara. 2016. Predicting three-month and 12-month post-fitting real-world hearing-aid outcome using pre-fitting acceptable noise level (ANL). International Journal of Audiology 55 (5): 285–294. doi:10.3109/14992027.2015.1120892.