Abstract

The purpose of this exploratory case study is to analyze the role of relational motivation for high-performing real estate brokers in Sweden. The concept of relational motivation, or relatedness, is explored through both affective and calculative commitment. The data in this study come from in-depth interviews with real estate brokers. The results show that the brokers are committed to their clients, in an affective and a calculative way. All of the participants expressed signs of being emotionally involved in their customer relations, often in terms of genuine interest in, and caring for, their clients. The existence of relatedness toward customers in a brokerage context contributes to the discussion on what motivates high-performing real estate brokers. By viewing relatedness as a trigger to engage in more customer relationships, the intrinsic motivation can be seen as a strong antecedent to individual performance.

Introduction

The possible causes of high individual performance in the brokerage industry have been widely studied (see Davenport, Citation2018; Johnson et al., Citation1988; Larsen, Citation1991). Although previous studies have linked various personal characteristics, such as education, experience, effort, extraversion, and conscientiousness, to performance (Benjamin et al., Citation2000; Johnson et al., Citation1988; Waller & Jubran, Citation2012; Warr et al., Citation2005), a relatively high proportion of the variation in broker performance remains unexplained (Davenport, Citation2018; Larsen, Citation1991). This study addresses this gap by exploring relational motivation among high-performing solo self-employed entrepreneurs (SSEs) in the real estate brokerage industry. Relational motivation is explored through a self-determination theory (SDT) perspective and emphasizes how interpersonal business relations (i.e., brokers and customers) either support or undermine the fulfillment of basic psychological needs (competence, relatedness, and autonomy) and how motivational orientation derived from such need fulfillment are maintained or transformed as a function of experiences within business relationships (La Guardia & Patrick, Citation2008).

In a high customer-interaction industry such as a real estate brokerage (Seiler et al., Citation2006), SSEs are dependent on their personality and skills (Martin & Munneke, Citation2010) to establish and maintain vital, preferably long-lasting customer relations (Love et al., Citation2011). Positive customer relations are necessary for their link to referrals (Seiler et al., Citation2006) and other positive financial outcomes (Carter & Zabkar, Citation2009), which in turn have a positive effect on SSE persistence (Schummer et al., Citation2019). Therefore, it makes sense that brokers who enjoy and are motivated by working with people might be more persistent. Hence, persistence within a brokerage not only depends on the ability to survive financially (Boles et al., 2012), but also on the individual motivation to engage in and develop positive customer relationships. However, motivation among entrepreneurs is an underresearched area (Carsrud & Brännback, Citation2011).

Customers generally prefer warm and personal relationships with brokers, mainly due to the amount of trust given to the broker and the amount of emotion and money connected to their homes (Salzman & Zwinkels, Citation2017). Hence, several questions connected to the underresearched relational perspective of service providers/brokers (Dalela et al., Citation2018) arise; for instance, do brokers prefer and are they motivated by service relationships or encounters (Gutek et al., Citation1999)? In other words, is commercial friendship mutually beneficial financially and emotionally (Rosenbaum, Citation2009)? Healthy and positive relations are necessary because they help fulfill the need of relatedness (Deci & Ryan, Citation2014). Relatedness is a vital part of the SDT of human motivation and is defined as a basic psychological need, focused on the necessity of healthy relationships and belongingness throughout life; it ranges from parental to work relationships (Deci & Ryan, Citation2014).

The impact on positive outcomes such as individual well-being is usually larger when it comes from relatedness to parents, than from relations with work-related persons such as customers (i.e., commercial friendships, Banerji et al., Citation2019), coworkers, or one’s own employees. This does not, however, diminish the importance of all types of relations, as all relations might help fulfill psychological needs and increase well-being (Weinstein & De Haan, Citation2014). However, SSEs are generally not seen as being primarily motivated by relatedness, due to the lack of one’s own employees (Schummer et al., Citation2019). Nevertheless, the fact that brokers depend on positive and long-lasting commercial friendships serves as a practical and theoretical foundation when exploring whether motivation is the missing link between intention and action, as put forward by Carsrud and Brännback (Citation2011).

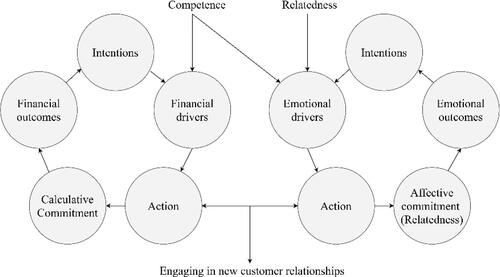

This study views calculative commitment toward customers as part of financial motivation, and it sees affective commitment toward customers as a proxy for relatedness with those customers (Rosenbaum, Citation2009). Calculative commitment is defined as a rational, task-orientated economic calculation (Gilliland & Bello, Citation2002). Whereas affective commitment is rooted in attachment (Bansal et al., Citation2004; Fullerton, Citation2003; Gruen et al., Citation2000) and positive affect (Fullerton, Citation2005) within trust- and friendship-based relationships (Price & Arnould, Citation1999). This means that both types of commitment might increase an SSE’s intentions to act in the future and eventually cause action (i.e., engaging in new customer relationships) derived from increased motivation. To our knowledge, previous studies among brokers or SSEs have not explored emotional attachment toward customers, and therefore not the possible connection between emotional attachment toward customers and motivation.

The purpose of this study is to explore the existence of relatedness between solo self-employed brokers and their customers. Special focus will be given to the following research question: What kind of relationships do brokers prefer with their customers?

Previous Studies

Motivation to Become an SSE in a Swedish Context

Previous studies have used the terms real estate broker and real estate agent almost interchangeably, as the preferred choice of label is dependent on context and legal framework (cf. Larsen et al., Citation2008; Ingram & Yelowitz, Citation2019). For example, some studies view agents as self-employed professionals who run their own firm or are operating as independent contractors (Giustiziero, Citation2020; Ingram & Yelowitz, Citation2019), while other studies describe brokers as owners of real estate agencies (Teixeira, Citation1998). On the other hand, some studies see agents as either self-employed or wage-employed, and the owner of the firm as an entrepreneur (e.g., Verheul et al., Citation2002). Some scholars argue that self-employment and entrepreneurship are the same (e.g., Millán et al., Citation2013) in terms of occupational choice. A more recent study by Ingram and Yelowitz (Citation2019) concludes that a majority of all real estate agents in the United States are independent contractors or self-employed within their firm, highlighting opportunities for entrepreneurship within the industry. One explanation for the differences in definition and usage of agent, broker, or entrepreneur is arguably the consequences of national laws, culture, and occupational norms.

Participants in this study were wage-employed brokers, yet their wages came solely out of their own commissions. These financial conditions are more similar to being an entrepreneur compared to being wage-employed. Hence, Swedish brokers are not easily defined as self-employed (entrepreneurs) or wage-employed.

In previous studies, entrepreneurs without personnel are sometimes described as solo self-employed, and sometimes as self-employed without personnel. Brokers are not described as neither of these axioms in previous studies, yet there are clear similarities between Swedish brokers and entrepreneurs without personnel, which will be more thoroughly described under next heading. This study makes no distinction between solo self-employed and self-employed without personnel. Solo self-employed will be used as an axiom for both. Henceforward, this study argues and defines Swedish brokers/participants as hybrids with strong similarities to solo self-employed. As previous studies have not considered or defined employed brokers as SSEs, a description of the SSE environment and why employed Swedish brokersFootnote1 are considered as SSEs is necessary.

People have various motives for becoming entrepreneurs (Schummer et al., Citation2019) and they pursue entrepreneurship for deeply idiosyncratic reasons (Wiklund et al., Citation2019a). However, previous studies have shown that individuals are attracted to self-employment because of greater independence, more autonomy, and higher expected earnings compared with what typical employment offers (Taylor, Citation1996). In nonpecuniary terms, research has found a consistently high level of job satisfaction and well-being among the self-employed (Benz & Frey, Citation2008a,Citationb; Blanchflower, Citation2000). The level of “attractiveness” (i.e., free choice) of self-employment, however, is influenced, whether in being pulled and seeing opportunities or in being pushed out of necessity, by entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurial motives are therefore sometimes categorized in terms of: i1) “push” and “pull” factors (Kautonen et al., Citation2010; Kirkwood, Citation2009); or 2) necessity- and opportunity-driven entrepreneurs (Conen et al., Citation2016; de Vries et al., Citation2019).

The number of solo self-employed entrepreneurs is increasing in Europe, and pull factors are more prevalent than push factors (Conen et al., Citation2016; GEM, 2019/Citation2020). This study makes no distinction between these different descriptions of entrepreneurship, which means that opportunity- and necessity-driven entrepreneurs will be used as an axiom for both ways of describing the motivational background for becoming an entrepreneur. Becoming an SSE in Sweden is most likely a free choice due to: 1) other job opportunities; 2) the possibility for higher education without fees; i3) an acceptable business climate and infrastructure; and 4) the perception, for 8 out of 10 persons in Sweden, of good opportunities to start a business, which is a crucial first step in the entrepreneurial journey (GEM, 2019/Citation2020).

Entrepreneurial Endeavors Among Employed Brokers

There is no commonly accepted unifying definition of entrepreneurship, and scholars use the term flexibly for their own research purposes (Wiklund et al., Citation2019b). Entrepreneurship involves the initiation, engagement, and performance of entrepreneurial endeavors embedded in environmental conditions, where an entrepreneurial endeavor is the investment of resources (i.e., cognitive, behavioral, financial, or other resources) to pursue (by exploration or exploitation) a potential opportunity (Shepherd et al., Citation2019). Brokers working solely on contingency are investing resources, foremost their time, in the almost never-ending pursuit of new clients. This stands in contrast to employed salespersons with fixed or semifixed salaries, where time spent with a potential customer always leads to an income. Swedish brokers are highly educatedFootnote2 compared with U.S. brokers regardless of the state they work in (Ingram & Yelowitz, Citation2019), which could be seen as a high threshold for becoming an entrepreneur (GEM, 2019/Citation2020). This also has strong parallels to the discussion in Shepherd et al. (Citation2019) about entrepreneurs investing cognitive and financial resources. Another perspective on education, in addition to resource usage, is described by Kara and Petrescu (Citation2018) as competence motivation such as the desire for self-achievement, accomplishment, creativity, and innovation (Marques et al., Citation2013).

Brokers are highly dependent on their own personality, skills, and motivation (Larsen et al., Citation2008; Love et al., Citation2011) to establish, maintain, and develop the positive customer relationships that are needed to survive financially (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994; Yinger, Citation1981). Shane and Venkataraman (Citation2000) define entrepreneurship as the identification and exploitation of business opportunities within the individual-opportunity nexus. Alternatively, as explained by Nuttin (Citation1984), motivation is shaped in the individual-environment context. When one views new customer relationships within a brokerage as opportunities that are possible to achieve based on one’s individual skills and motivation, another resemblance between brokers and entrepreneurs is revealed. Most Swedish brokers are employed but, nonetheless, generally work solely on commission and do not work fixed hours (Mäklarsamfundet, 2020a), which also means flexible personal time (Waller & Jubran, Citation2012).

Previous studies indicate that individuals’ desires for freedom, control, and flexibility in the use of their personal time are considered primary reasons for starting a business or becoming self-employed (Annink et al., Citation2016; Carter et al., Citation2003; Zhang & Schøtt, Citation2017). By law, Swedish brokers are accountable for the entire real estate transaction, meaning that no lawyers or other brokers are necessary (Maklarsamfundet, 2020b; SFS 2011:666). Arguably, these circumstances and working conditions are probably more suited (a higher person job fit) to individuals who are motivated by working with people (Donavan et al., 2004) and who prefer autonomy in the form of performance-based income and flexible working hours.

To summarize, the working conditions for Swedish brokers highly resemble the settings of SSEs. The similarities can be found in financial uncertainty, high workload (Müller, Citation2015; Waller & Jubran, Citation2012), no fixed working hours (Uy et al., Citation2013; Waller & Jubran, Citation2012), and dependency on personality and one’s own initiatives (Love et al., Citation2011; Schummer et al., Citation2019). Based on this line of reasoning, participants are seen as opportunity-driven SSEs. The fact that people become entrepreneurs based on free will and the drive for opportunities is important to understand when trying to untangle different types of motivation due to a higher likelihood of entrepreneurship being intrinsically motivated (Schummer et al., Citation2019). Previous research has indicated that people who are solo self-employed and self-employed with personnel have different motives for starting and running a business (Parker, Citation2004). However, de Vries et al. (Citation2019) argue that motivation depends on the context. Hence, this study uses an entrepreneurial solo self-employed motivational perspective when analyzing employed brokers.

Relational Benefits Seen Through Calculative and Affective Commitment

Within brokerage, there are interactions between customers and brokers (Seiler et al., Citation2006; Yavas, Citation1994). These interactions vary in time and intensity from service encounters to possible service relationships (Gutek et al., Citation1999), and are sometimes called “moments of truth” in marketing and management because customers are using and possibly evaluating the service at the same time (Groth et al., Citation2019). The necessity to create trust toward oneself is therefore of utmost importance for service providers such as brokers (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994). Commitment is, according to Morgan and Hunt (Citation1994), influenced by its benefits. The trust gained is important for financial survival and, therefore, is a financial benefit for the broker.

Gilliland and Bello (Citation2002) emphasize that “calculative commitment” is the result of opportunistic rather than passive behavior. Hence, it is plausible that brokers are calculative with regard to their behavior to gain trust. Morgan and Hunt (Citation1994) describe commitment as a unidimensional construct. However, a more recent study by Berghäll (Citation2003) resulted in a two-dimensional model of commitment. Berghäll (Citation2003) labels the conscious layer of relationship “calculative commitment,” while the preconscious feeling-like evaluation of a relationship was labeled “emotional commitment.” Other scholars have used “affective commitment” instead of emotional commitment when describing the same phenomena (see Gilliland & Bello, Citation2002; Gruen et al., Citation2000). Previous studies using affective commitment have often focused on customer development of an emotional attachment to the relationship (Fullerton, Citation2005) that is rooted in shared values (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994). However, commitment in the context of a commercial relationship has been defined by Moorman et al. (Citation1992, p. 316) as “an enduring desire to maintain a valued relationship.” This study emphasizes that it takes two to tango, meaning that it takes at least two individuals for a relationship to occur and survive. Hence, given a dyadic perspective on commitment (Lydon et al., Citation1997), if an enduring desire (Moorman et al., Citation1992) is compulsory for commitment to flourish, then the relational benefits are as necessary for brokers to explore as for customers. The relational benefits for brokers might be financial, as previously stated; however, there might also be emotional benefits derived from affective commitment toward customers as indicated in Rosenbaum’s (Citation2009) study on mutually beneficial commercial friendships in a service setting. Previous studies argue that there is a correlation between calculative and affective commitment, depending on the empirical setting (Davis-Sramek et al., 2009; Staal Wästlund & Kronholm, 2017). However, this study does not focus on the correlation per se, yet emphasizes the existence of affective commitment in a brokerage setting.

Relatedness Towards Customers

The existence of affective commitment in a commercial relationship is relevant because affective commitment could cause or increase intrinsic motivation by attaining relatedness. As previous studies have indicated, intrinsic motivation is a powerful or predictor of well-being, performance, and job satisfaction (Deci & Ryan, Citation2014).

Relatedness toward customers might serve as a motivational force triggering brokers to engage, as that motivation could increase the extent of action (Carsrud & Brännback, Citation2011) in new customer relationships. However, to our knowledge previous studies have not explored relatedness toward customers from a motivational perspective in a brokerage setting. Relatedness is one of three basic psychological needs that, according to SDT, are critical for optimal human functioning and well-being (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000). Self-determination theory argues that some level of close personal relationships not only is desirable, but also is essential for optimal human functioning and well-being because relationships are what satisfy the need for relatedness (Deci & Ryan, Citation2014). Relatedness goes beyond close personal relationships (Weinstein & De Haan, Citation2014), as it includes connections to others in one’s social sphere, caring for others, and having a sense of belonging to valued groups or organizations. Weinstein and De Haan (Citation2014) stipulate that social environments provide relatedness and needed support when one relates to others in an open and authentic fashion.

The work-related social environment for an SSE in the brokerage industry consists largely of customers. Customers are an essential group for brokers, due to their financial importance. However, customers also might be a valued group because affective commitment could lead to relatedness, which in turn leads to favorable outcomes such as well-being. Hence, affective commitment toward customers is used as a theoretical proxy for relatedness in this study.

Methodology

An Explorative Case Study

This study is rooted in practice and focuses on a context-specific problem: the existence of relatedness among SSEs in the brokerage industry. This focus ought to have, according to Weick (Citation1992) and Bansal et al. (2018), a qualitative inductive research approach. Another rationale for using a qualitative approach in this study is to provide participants with the opportunity to freely express themselves in their own words, thus enabling researchers to closely capture each individual’s subjective experiences and interpretations (Gioia et al., Citation2012; Graebner et al., Citation2012). This study therefore uses a blended inductive and deductive process (i.e., the abductive approach), which is quite common in social science research (Graebner et al., Citation2012; Kovács & Spens, Citation2005). Bitektine (Citation2008) and Yin (Citation2003) claim that researchers using a qualitative research approach sometimes let the theoretical framework from the literature guide their research before collecting data. The usage of transferal theoretical frameworks in abductive studies is underscored as a major distinguisher between abductive and inductive/deductive studies (Dubois & Gadde, Citation2002). The theoretical framework in this study emanates from self-determination theory and was used to create the interview questions (see ).

Table 1. Theories, papers, and examples of interview questions.

The participants in this study were all employees within the same organization, which made it possible to conduct a single case study. Henry and Foss (Citation2015) argue that an especially valuable dimension of the case approach to research is that the particular phenomenon under investigation is not isolated from its context; rather, it is of specific interest precisely because it is directly related to its context.

In this study, we argue that the possible existence of relatedness toward customers is partly explained by the specific context brokers and their customers’ experience. However, participants served as an example of a more general phenomenon presumably applicable in a broader context. This specific case and the participants (i.e., only the highest performers) were chosen to limit extraneous variation and sharpen external validity. The focus was on theoretically useful stories that replicated or extended the theory by filling in conceptual categories (Eisenhardt, Citation1989).

Previously, single case studies have been used to support variance-based theorizing (Bansal et al., 2018) by comparing current understanding with insights from relevant theories. These variance-based approaches tend to follow a positivist paradigm in that other researchers can assess the validity of the theory and constructs by applying them to other empirical settings (Bansal et al., 2018). However, the theories and definitions that were used in this study have a variety of definitions such as the concept of entrepreneurship and relatedness as a motivational factor among SSEs. Definitions are important, as they are needed for the proposed relationships to transcend a specific context (Eisenhardt, Citation1989). The goal of this study was therefore to explore these relationships, and this approach is in line with the studies by Ragin and Becker (Citation1992) and Eisenhardt (Citation1989). The exploration of motivation as a possible antecedent of preferable outcomes, such as well-being and entrepreneurial financial sustainability, is more connected to understanding than to construct development (Gioia et al., Citation2012). However, the results from this study could be used to further develop theory and constructs by replicating the study in a different entrepreneurial occupational context.

In the seminal work by Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985), it is argued that it is possible and necessary to increase the trustworthiness of a qualitative study by replacing the traditional concepts of validity and reliability with credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. The need for more qualitative case studies of higher quality appears to be particularly vital with regard to research on entrepreneurship (Henry & Foss, Citation2015). This study follows Lincoln and Guba’s (Citation1985) recommendations to increase trustworthiness using different methods (see .

Table 2. Methods used for increasing trustworthiness.

Interviews and Selection of Participants

In this study, semistructured interviews with nine top-performing real estate brokers (see ) were conducted in 2018 online using Zoom, which is a recordable videoconference tool. The interviews lasted between 35 and 50 minutes, and 9 interviews were recorded and later transcribed verbatim. The participants were all employed brokers at one of Sweden’s largest real estate brokerage firms, with a market share of approximately 25%. The focal firm was selected due to its size and its management’s willingness to assist and contribute in different ways such as providing actual sales data for the individual real estate brokers (see . The selection of the participants within the firm was based on that individual sales data. Based on actual sales data, 27 possible participants (15 women and 12 men) were selected. Out of these, 9 were willing to participate (see ). Some of the possible participants did not answer at all to the invitation and some of them declined due to time issues.

Table 3. Sample data, and sales numbers in year 2018.

These 9 participants were placed, based on total commission and compared to all 27 possible participants, at places 1, 2, 7, 8, 9, 10, 17, 24, and 27 (see ). Notable is that more women than men participated. Hence, a gender bias is possible. However, this was an explorative study that did not aim to be representative. The participants were informed before the interviews that the overall theme of the interviews was “customer relationships.”

Interview Questions

The interviews were focused on the relationships between brokers and customers (see the Appendix). As a consequence, the collected data did not focus on all three psychological needs in the SDT of SSEs. Swedish brokers, as previously mentioned, have a strong resemblance to traditional SSEs. Gutek et al. (Citation1999) stipulate that there is a distinction between service encounters and service relationships that can be found by asking customers whether they say “a doctor or my doctor” when referring to their doctor. The interview questions were based on Gutek’s (Citation1999) paper to define the service interaction and to explore what kinds of relationships brokers prefer to have with their customers. Rosenbaum (Citation2009) argues and illustrates that there is an interdependence between service providers and their customers regarding the exchange of intrinsic support and extrinsic financial incentives. The interview questions in this study were based on papers by Rosenbaum (Citation2009) and Dalela et al. (Citation2018) and were constructed to explore differences in commitment toward customers – in other words, whether they were affective or calculative. Deci and Ryan (Citation2000) and Weinstein and De Haan (Citation2014) discuss and argue for the necessity of fulfilling the need for relatedness to increase well-being and the embedded correlation between intrinsic motivation and relatedness. The interview questions based on Deci and Ryan (Citation2000), and Weinstein and Haan (Citation2014) focus on relatedness. However, some questions were more general – such as “What motivates you as a broker?” – and opened the door for answers correlated to all three basic psychological needs of SDT.

The Coding Process

The first step after transcribing the interviews was to organize all of the answers related to each question. The interviews were then thematically analyzed according to service relationships or encounters, commitment, and relatedness (as shown in ). A thematic analysis is a method for recognizing patterns in the data, during which emerging themes become the categories for analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, Citation2006). The coding process for this study followed Pearse’s (Citation2019) guidelines for deductive thematic analysis, mainly due to the theoretical themes. The theoretical themes were primarily used as a framework for the analytic process, meaning that the themes that emerged from the data were analyzed as well as the themes that had the most important consequences for the theoretical framework.

During the second phase of the coding process, the data were analyzed from a slightly different perspective. Instead of following the theoretical framework as in the first phase , the second phase analyzed the data according to emerging themes. These emerging themes were: 1) the type of relationship; 2) the preferred relationship; 3) the outcomes of the preferred relationship; and 4) background questions such as age, family, and brokerage experience. The analysis of the data according to emerging themes had some similarities to the conceptual model of motivation. This means that the emerging themes were chronological with respect to the interactions with a customer; that is, the preferred relationships and the outcomes of those preferred relationships.

In the third and final phase of the analysis, it became clear that some questions and answers could fit with more than one theme, regardless of whether a theme was driven by theory as in the first phase or emerging as in the second phase. As a consequence, the data were rearranged according to the theoretical framework used in the first phase with the alteration that participants’ answers guided the placement under different theoretical themes.

Empirical Findings

Service Relationships or Service Encounters?

Almost all (eight out of nine) participants said “my customer” when referring to their customers. One participant thought for a while and then said that she usually said “my customer.” The same participant was the only one who mentioned that “our office,” “our coworkers,” and so forth, had joint customers. Responses were usually (seven out of nine) given immediately. A majority of participants believed that their customers often sought a more personal and warmer relationship with them and that customers believed they had a warmer and more personal relationship than a broker’s own opinion of the relationship. All participants preferred warmer, more personal relationships with their customers rather than colder, more neutral relationships. A phrase commonly used when participants were talking about their preferred relationships with customers was “warm, yet professional.”

The participants were asked to sort their customer base according to what kind of relationship they felt they had with their customers in the categories of warm, neutral, or cold. Not all participants provided results in specific numbers; the ones who did claimed that 80%–90% were warm, 20% were neutral, and 0%–10% were cold. The main reason specified for preferring warmer relations was that it made work more easygoing and enjoyable. The participants were also asked to evaluate how much of their business was derived from returning customers and recommendations. Again, not all of the participants answered in specific numbers. Among the seven out of nine who did, returning customers and recommendations were estimated to be 45%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 95%, and 95% of their business.Footnote3

When participants discussed whether there were differences in interactions with customers when comparing previous jobs with their current brokerage position, a slightly incoherent picture appeared in that one participant argued that brokerage did not differ that much,Footnote4 yet another participantFootnote5 argued that brokerage was much more personal, as you get so close to the customer when entering their homes and gaining their trust. Brokerage was often discussed by participants in terms of helping customers solve problems. Three participants said that they often became a kind of psychologist due to entering customers’ lives during times of personal crises such as divorce, separation, or death, as highlighted by the quote below:

You really enter their personal sphere.

One participant argued that it might have been easier for customers to talk to their broker because they were outsiders and not involved in potential personal conflicts. Hence, the business settings and context for the interaction with customers were often affected by crises in customers’ lives. Brokers preferred warmer relationships, referring to customers as “my customers,” and were pleased that a majority of their customers were returning customers. This sums up the research question as initially presented.

Motivation

The participants’ answers to “What motivates you as a broker?” are presented in . When evaluating the results derived from , the focus was on the most frequently used motivational factors.

Table 4. “What motivates you as a broker?”.

Terms such as personal development and competition were often used together when participants discussed driving forces within the brokerage industry. Participants often spoke about selling more, becoming more efficient, and developing a better reputation through satisfied customers when they discussed personal development. Competitiveness was not primarily directed toward other brokers but, rather, participants mainly strived to improve their own previous results. All participants stated that listings and rewards (categorized as competition in ) for high achievers were a driving force in themselves. These statements might seem contradictory. However, participants often accentuate that making fewer sales than in the previous period was upsetting, whereas selling fewer properties than other brokers was not mentioned at all during interviews. Working with customers was described as a fundamental and overall positive part of brokerage by all participants.

Notably, 4 of the 29 motives specified by brokers indicated that working with customers was a motivational factor, and 2 of the 29 motives indicated that sales in itself was a motivational factor. The participants (2 of 9) who were motivated by sales were also motivated by either meeting and working with people or kicks/competition.

To have a commission-based salary and make money were not commonly used together. When referring to commission-based salary, participants often used the words “ability” and “impact/influence” in a positive manner. Making money was stated in a more neutral manner and was repeatedly used when participants were describing occupational hygiene factors such as the ability to control and schedule one’s days. The possibility to work from home and having flexible hours to make one’s own schedule was often mentioned throughout the interviews in a positive, yet neutral, manner. However, this was not mentioned when discussing motivational factors. Notably, motivation was discussed under more than one question such as in the results presented above.

Calculative Commitment

All participants stipulated throughout the interviews that positive customer relations were of the utmost importance in becoming a financially successful broker. The necessity of positive customer relations to financial gains was frequently found in participants’ statements. Positive customer relations were often used together with words or expressions such as returning customers, good reputation, and recommendations. However, some participants discussed customer relations in a more neutral manner; for example, one and that he wanted to foster this relation in the future. Another participant said that customer relations could be rewarding and nurturing, as others could be draining. Participants displayed a wide range of views or opinions as well as feelings related to customer relations; one broker put it this way:

You can come from a meeting quite euphoric and be very happy. Or you come out feeling like you want to resign and start working at a grocery store or something like that instead.

It is noteworthy that the responses to the question, “Are customer relations important to you?” were generally not answered in terms of the same financial outcomes as for the question, “How do you view customer relations?” For example, instead of using financial outcomes, participants were more likely to use words and phrases such as personal, disappointed, satisfied, and it’s in my nature to have good relations with people. One of the participants elaborated on this aspect:

After working 8.5 years as a broker, I can still get very upset if a customer feels that I have let them down. It is buried somewhere deep inside that you don´t want to disappoint or upset people.

The same participant elaborated on the above quote and explained that she spent much time keeping in touch with customers, primarily buyers, after transactions had been finalized. She said that the reason for doing this was mainly for her own sake because it made her feel good when she knew that customers were satisfied. The second reason for keeping in touch with customers was because it might lead to more business and recommendations. The shift in priority between keeping in touch or receiving more business as being most important to her was also noteworthy. Hence, a follow-up question was asked: “Is there an emotional and financial outcome derived from customer relations?” to which she responded, “Yes, exactly, in two ways, partly for my own sake and partly for increasing sales since that is what we want to do.”

When participants discussed whether their view of customer relations had changed over the years, they generally described some sort of shift that took place after being a broker for a couple of years. In the beginning of their careers, the focus was more on actual sales and building a customer base. As time went by, their views on customer relations sometimes changed; for example, one participant used the phrase “out of benevolence” when discussing a shift in his perceptions of customer relations. Some participants (four out of nine) explained that they had developed a network consisting of previous customers. These networks were not discussed in terms of financial outcomes such as existing customers providing recommendations to potential customers. Instead, these networks were described as more personal; for example, one of the participant’s dog was walked by a customer, and one participant hired a customer to redo a a bathroom.

Affective Commitment

There were, as mentioned, financial incentives in the participants’ answers associated with customer relations. However, some participants’ answers revealed a complexity regarding their commitment to customers, which means that most participants found it easy to be open and personal with customers, yet most of them were not driving for or pushing commitment; rather, they were mirroring customers’ levels of openness. Other statements from participants were more reflective concerning emotional incentives and outcomes (i.e., affective commitment toward customers). One of the participants discussed this:

The more we talk about it, the more I understand that I enjoy customer relations on a personal level also, now that we sit and talk about it, I realize that the customer relationship itself drives me.

The above quote was somewhat significant for most participants, as it highlighted the result that participants were generally not as aware of their emotional connections to their customers or what positive or negative effect those relations might have on them. These results were more interesting when compared with the motivational factors presented in . However, during some of the interviews, the participants reflected not only on the necessity of customer relations, but also on the upsides and downsides of being personal with customers, as highlighted by this quotation:

This is not an ordinary job. If you do not realize that, you will not last very long. You have to like these specific customer relations and seeing them as having an extended value.

Several participants mentioned boundaries when talking about personal interactions with customers, in that customers were more than welcome to share personal information, but there was no need for brokers to discuss their own personal lives with customers. Other participants did not appear to have the same boundaries, describing themselves as open books who told their customers everything. Calculative and affective commitment were often visible at the same time when participants talked about customer relations. Time was often discussed as a restraining factor, in regard to increasing performance and in terms of the necessity to be professional toward customers for efficiency. All of the participants showed signs of being emotionally involved in their customer relations. To be involved was often expressed as interest or caring. However, the amount of interest and caring toward customers varied among participants.

Relatedness

Before presenting the results connected to relatedness, it is useful to summarize the previous results, as relatedness is embedded in them in that participants: 1) preferred warmer relationships; 2) believed that customers preferred warmer relationships; 3) believed that customers thought the relationship was warmer than the brokers did; 4) perceived the business setting for the brokerage as extensively influenced by customers’ emotions correlated with, for example, money, births, deaths, and separations; and 5) showed signs of both calculative and affective commitment. None of the participants expressed problems or hesitation about being personal with customers. In contrast, participants generally liked it; for example:

I’m doing it out of free will. Ím not forced to say anything about myself and it does not bother me at all, it’s the exact opposite.

One participant said that being personal was good because it built trust. Trust was not a topic derived directly from interview questions; rather, the participants discussed trust gained from customers as a necessity for brokerage (i.e., a hygiene factor). However, two participants talked about the trust gained from customers as a motivational factor in itself. Becoming friends with customers was discussed in various interview questions. Participants were generally reluctant to become close friends with customers. The reasons for not engaging in friendships were often argued to be decreased professionalism, lack of time, and a desire to separate work and private life. However, many participants had former customers who had become friends or customers who they got together with casually for lunch or coffee. The participants were generally affected by their customer relations. However, what affected them and to what extent varied, meaning that some participants were more affected by good customer relationships compared to bad ones, and vice versa. Affective commitment was seen as a proxy for relatedness in this study. However, some participants talked about their relationships with customers in a more profound and complex way; for example:

I really care about my customers- I’ve sat and cried with them, I really feel for them.

Analysis

Service Relationships or Service Encounters?

The necessity of having positive and long-lasting customer relationships was frequently mentioned, which is in line with previous studies (Carter & Zabkar, Citation2009; Seiler et al., Citation2006). Preferring warm and personal relationships and saying “my customer” indicates a service relationship (Gutek et al., Citation1999). According to the participants, customers also preferred warmer and more personal relationships, which is also in line with previous studies (Rosenbaum, Citation2009; Salzman & Zwinkels, Citation2017). There were similarities – that is, financial and emotional benefits – between the brokers’ descriptions of preferred customer relations and Rosenbaum’s (Citation2009) illustration of interdependence between service providers and customers.

The participants painted a picture of a service landscape for brokers that involved large amounts of money as well as emotions, which is in line with previous studies (Salzman & Zwinkels, Citation2017). However, participants also talked about entering their customers’ personal spheres, helping them, and acting as lay psychologists. This was not as visible in previous studies conducted among SSEs in the brokerage business (Banerji et al., Citation2019). Both participants and Weinstein and De Haan (Citation2014) used the expression “personal sphere”; however, they approached the expression differently. The participants used it primarily to describe the service landscape, whereas Weinstein and De Haan (Citation2014) used it mainly when describing having someone in your sphere and valuing their opinions. Arguably, both ways of using the expression point to a possible closeness between individuals. Hence, participants’ use of the expression strengthens the argument of service relationships regardless of whether they were a consequence of the service landscape or of preferred relationships.

Motivation

The purpose of this study was not to explore all motivational factors among high-performing brokers. However, analyzing the answers to the general question “What motivates you as a broker?” revealed that striving for fulfillment of the basic psychological needs for competence, relatedness, and autonomy were all visible and motivational forces for high-performing brokers (see ). Joy, to work in sales, and kicks were seen as intrinsic motivation, yet were not easily sorted under competence, relatedness, or autonomy, all of which were seen and analyzed as intrinsic motivation.

Table 5. Motivational factors for high-performing real estate brokers.

To develop, compete, and favor a commission-based salary were seen as internal and external validation of competence. This means that evolving through learning how to sell more and competing against oneself were examples of internal validation of competence. Winning sales contests and increasing one’s salary were examples of external validation of competence. Favoring a commission-based salary was also seen as an expression of being motivated by autonomy. To be intrinsically motivated by working with customers was primarily seen as connected to relatedness (Weinstein & De Haan, Citation2014).

Working with customers was a stronger motivator than working in sales and making money, which is interesting as it arguably relates to motivation to engage in new customer relationships; that is, increasing intentions to act (Carsrud & Brännback, Citation2011). The somewhat neutral, yet positive, tone participants used when talking about, for instance, flexible hours, might indicate that autonomy was seen more as an occupational hygiene factor than as a motivational factor in itself. Notable also is what participants did not talk about when discussing the motivational factors within the brokerage. A topic such as leadership was not mentioned at all during the interviews, and other brokers or assistants were not mentioned when discussing motivational factors and were seldom mentioned during the rest of the interview. This strengthens the previous discussion that Swedish brokers have many similarities with solo entrepreneurs who have no employees.

Calculative Commitment

The participants were aware of the financial gains stemming from customer relationships. Their awareness of financial gains was visible through calculative commitment, which is in line with previous studies (see Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994) that argue that commitment is influenced by its benefits, and Gilliland and Bello (Citation2002) who emphasize that calculative commitment is the result of opportunistic behavior. The participants were, hence, arguably triggered by financial motives to engage in new customer relationships (Carsrud & Brännback, Citation2011).

Interacting with customers was generally perceived as both draining and rewarding regardless of the type and intensity of the calculative commitment. Hence, the service landscape for the brokerage might affect brokers (e.g., well-being) regardless of the possible intermediation from their levels of calculative and affective commitment toward customers. Another influencing factor on commitment, in addition to the service landscape, was how changes in participants’ perceptions of customer relations have evolved over time. The change was from a more pragmatic, unidimensional, necessity-based focus – as described by Morgan and Hunt (Citation1994) – to a two-dimensional commitment construct (see Gilliland & Bello, Citation2002) that included a better understanding and respect for customers and finding joy in the relationship in itself.

Affective Commitment

The participants often defined themselves as social and described customer relations by using phrases such as feeling happy, extended value, amazing, fun, and personal; some even argued customer relations to be a driving force for becoming a broker. The presence of emotions connected to customers was arguably an antecedent of various amounts of emotional attachment to the relationship, as stipulated by Fullerton (Citation2005), who argues that emotional attachment is an antecedent of affective commitment.

To be driven by warm customer relations and seeing them as having “extended value,” as argued by one participant, were arguably indicative that intentions, actions, and consequences derived from customer relations might involve something more than calculative commitment. To be driven by customer relations could therefore be seen as positively influencing one’s intentions to engage in new customer relations due to increased motivation. Based on the arguments put forward in Weinstein and De Haan (Citation2014) – that all relationships matter when striving for relatedness – both types of commitment are seen as potential indicators of motivation as a catalyst between intentions and action (Carsrud & Brännback, Citation2011). Another reflection, based on the line of reasoning above (and all participants being top performers), is the correlation between a mutually beneficial relationship (Rosenbaum, Citation2009) and high individual performance. The meaning of this is that a higher level of affective commitment, in combination with high calculative commitment, might be an antecedent of individual performance. The different types of commitment might be triggered by different motives and connected to different psychological needs; for example, relatedness or competence (Decci & Ryan, 2000). Hence, the results of this study indicated that high two-dimensional commitment might help explain individual performance in the brokerage business beyond other factors such as education, experience, effort, extraversion, and conscientiousness (Benjamin et al., Citation2000; Davenport, Citation2018; Johnson et al., Citation1988; Warr et al., Citation2005).

Relatedness

The participants were aware of the need to be personal with customers, and none of them had problems being personal – they even favored it. Then, arguably, there was a match between customer preferences, service landscape conditions, and participants’ own preferences; that is, a high person-job fit (Donavan et al., 2004) among participants. This match went beyond calculative commitment and also included affective commitment toward customers, as some participants reported a two-directional stream of emotions, including caring for and crying with customers (i.e., relatedness). Arguably, these situations normally require commitment and trust (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994) from both parties for them to occur; that is, a dyadic perspective on commitment (Lydon et al., Citation1997). To be driven by gained trust, as reported by a participant, is interesting, as gained trust might be a motivational factor correlated to both competence and relatedness (Decci & Ryan, 2000). This means that gained trust not only is an antecedent or necessity of relatedness, but also might be an antecedent of the intention to engage (Carsrud & Brännback, Citation2011) in a new customer relationship.

A part of being affected by the negative judgments that came from customer relations were their critical nature; that is, you are not competent (as competence was a strong motivational factor for the participants). Several participants described being personally affected by disappointed customers. The existence of relatedness toward customers among SSEs in the brokerage is interesting as: 1) customers were generally not seen as a source of relatedness in previous studies; 2) relatedness could affect well-being through intrinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan, Citation2014); 3) previous studies among SSEs have not seen relatedness as an important motivational factor (Schummer et al., Citation2019); and 4) increased performance through customer satisfaction increases entrepreneurial endurance (Schummer et al., Citation2019).

Theoretical Contributions

On the one hand, Gilliland and Bello (Citation2002) emphasize that calculative commitment is the result of opportunistic behavior. Morgan and Hunt (Citation1994), on the other hand, argue that commitment is influenced by its benefits. These two lines of reasoning are not contradictory from a motivational perspective, but rather complementary (see ).

Figure 1. Motivation to interact with customers seen through the basic needs of competence and relatedness.

Calculative and affective commitment are a consequence of brokers’ actions toward and engagement in new customer relationships, as shown in . The financial outcomes and intentions that lead to a financial driver (motivation) have been well established in previous studies. However, emotional outcomes and intentions leading to an emotional drive to engage in new customer relations have not been as prevalent in previous research. Therefore, not only does commitment need to be seen as a two-dimensional or bidirectional construct, but it is also necessary to explore how it correlates to action through financial or emotional motivation from the perspective of the service provider. It is necessary to fully answer the question in Carsrud and Brännback (Citation2011) of whether motivation is the missing link between intention and action. To be motivated by customer relations is somewhat complex, as motivation correlates to different antecedents (calculative/affective commitment) and outcomes (performance/persistence and well-being). On a level of higher abstraction, different antecedents and outcomes are debatably derived from different individual needs for relatedness, competence, and autonomy grounded in variation in personality traits.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to explore the possible existence of relatedness toward customers among high-performing real estate brokers. The study shows that relatedness toward customers, as seen through affective commitment, truly exists.

The existence of relatedness is arguably a consequence partly derived from the service and emotional landscape (i.e., large sums of money, customers’ life situations and feelings) and partly derived from relational preferences among high-performing brokers and their customers (i.e., a mutually beneficial service relationship). To our knowledge, this study is the first that emphasizes brokers’ emotional connection to customers and argues that it affects motivation. To prefer service relationships and be driven by affective commitment and relatedness toward customers is interesting as it: 1) might help to further explore whether motivation is what triggers intention into action and engagement in new customer relationships; and 2) might be an indicator of a higher person-job fit seen through performance, well-being, and outermost persistence and sustainability.

Due to the small sample size, correlations between relatedness and outcomes such as individual performance and well-being are impossible to measure. However, as all participants were high performers, future studies could examine whether there is a positive correlation between performance and relatedness toward customers using a larger sample size. Another area for future research is how personality traits influence types of commitment and motivation, as this study indicates that time as a broker influences relational motivation.

Notes

1 Brokerage as a function or occupation is highly regulated through different laws in Sweden. The Swedish occupational system for brokerage differs from the U.S. system as the Swedish system does not consist of agents and brokers. A Swedish broker is more similar to a U.S. broker then a U.S. real estate agent because Swedish brokers are licensed to sell properties, own their own real estate firm, and draft or oversee signing of legal documents. However, most Swedish brokers are employed by a firm, which makes them very different from U.S. brokers.

2 The respondents (Swedish SSEs registered as real estate brokers) are by law required to undertake circa two years of university studies within the real estate domain to be registered as real estate brokers.

3 Participants with the lowest levels of returning customers and recommendations (45; 50%) were also the ones with the shortest time as brokers. Arguably, the longer you work, the higher is the possibility for more returning customers.

4 Participant had previously been employed as a salesperson at an electronics store.

5 Participant had previously been employed at several organizations as a salesperson in a business-to-business setting.

References

- Annink, A., Den Dulk, L., & Amorós, J. E. (2016). Different strokes for different folks? The impact of heterogeneity in work characteristics and country contexts on work-life balance among the self-employed. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 22(6), 880–902. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-04-2016-0127

- Banerji, D., Singh, R., & Mishra, P. (2019). Friendships in marketing: A taxonomy and future research directions. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 10, 223–243. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13162-019-00153-9

- Bansal, H. S., Irving, P. G., & Taylor, S. F. (2004). A three-component model of customer to service providers. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(3), 234–250. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070304263332

- Bansal, P. T., Smith, W. K., & Vaara, E. (2018). New ways of seeing through qualitative research. Academy of Management Journal, 61(4), 1189–1195. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2018.4004

- Benjamin, J. D., Jud, G. D., & Sirmans, G. S. (2000). What do we know about real estate brokerage? Journal of Real Estate Research, 20(1–2), 5. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=buh&AN=3611258&site=ehost-live&custid=s3912055 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10835547.2000.12091034

- Benz, M., & Frey, B. S. (2008a). Being independent is a great thing: Subjective evaluations of self-employment and hierarchy. Economica, 75(298), 362–383. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.2007.00594.x

- Benz, M., & Frey, B. S. (2008b). The value of doing what you like: Evidence from the self-employed in 23 countries. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 68(3–4), 445–455. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2006.10.014

- Berghäll, S. (2003). Developing and testing a two-dimensional concept of commitment: Explaining the relationships perceptions of an individual in a marketing dyad [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Helsinki, Department of forest economics, Publication 10.

- Bitektine, A. (2008). Prospective case study design: Qualitative method for deductive theory testing. Organizational Research Methods, 11(1), 160–180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106292900

- Blanchflower, D. G. (2000). Self-employment in OECD countries. Labour Economics, 7, 471–505. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0927-5371(00)00011-7

- Boles, J. S., Dudley, G. W., Onyemah, V., Rouziès, D., & Weeks, W. A. (2012). Sales force turnover and retention: A research agenda. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 32(1), 131–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/PSS0885-3134320111

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Carsrud, A., & Brännback, M. (2011). Entrepreneurial motivations: What do we still need to know? Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 9–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2010.00312.x

- Carter, N. M., Gartner, W. B., Shaver, K. G., & Gatewood, E. J. (2003). The career reasons of nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18, 13–39.

- Carter, B., & Zabkar, V. (2009). Antecedents and consequences of commitment in marketing research services: The client’s perspective. Industrial Marketing Management, 38(7), 785–797. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2007.10.004

- Conen, W., Schippers, J., & Buschoff, K. S. (2016). Self-employed without personnel between freedom and insecurity. Work, Employment and Society, 18(2), 321–348. https:// https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017200404277205, 136.

- Dalela, V., Givan, A. M., Vivek, S. D., & Banerji, K. (2018). The employee’s perspective of customer relationships: A typology. Journal of Services Research, 18(2), 37–54. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=buh&AN=134680910&site=ehost-live&custid=s3912055

- Davenport, L. (2018). Home sales success and personality types: Is there a connection? Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 21(1), 29–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10835547.2018.12091776

- Davis-Sramek, B., Droge, C., Mentzer, J. T., & Myers, M. B. (2009). Creating commitment and loyalty behavior among retailers: What are the roles of service quality and satisfaction? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 37(4), 440–454. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-009-0148-y

- de Vries, N., Liebregts, W., & van Stel, A. (2019). Explaining entrepreneurial performance of solo self-employed from a motivational perspective. Small Business Economics, 55, 447–460. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00244-8

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2014). Autonomy and need satisfaction in close relationships: Relationships motivation theory. In N. Weinstein (Eds.), Human motivation and interpersonal relationships (pp. 53–77). Springer.

- Donavan, D. T., Brown, T. J., & Mowen, J. C. (2004, January). Internal benefits of service worker-customer orientation: Job satisfaction, commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Marketing, 68, 128–146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.68.1.128.24034

- Dubois, A., & Gadde, L.-E. (2002). Systematic combining: An abductive approach to case research. Journal of Business Research, 55(7), 553–560. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(00)00195-8

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. The Academy of Management Review, 14, 532–550. [Database] https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/258557

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107

- Fullerton, G. (2003). When does commitment lead to loyalty? Journal of Service Research, 5(4), 333–344. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670503005004005

- Fullerton, G. (2005). The impact of brand commitment on loyalty to retail service brands. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences de L'administration, 22(2), 97–110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1936-4490.2005.tb00712.x

- GEM. (2019/2020). GEM global report. Retrieved March 28, 2020 from http://www.gemconsortium.org.

- Gilliland, D. I., & Bello, D. C. (2002). Two sides to attitudinal commitment: The effect of calculative and loyalty commitment on enforcement mechanisms in distribution channels. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30(1), 24–43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/03079450094306

- Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2012). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151

- Giustiziero, G. (2020). Is the division of labor limited by the extent of the market? Opportunity cost theory with evidence from the real estate brokerage industry. Strategic Management Journal, 2021, 1–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3249

- Graebner, M. E., Martin, J. A., & Roundy, P. T. (2012). Qualitative data: Cooking without a recipe. Strategic Organization, 10(3), 276–284. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127012452821

- Groth, M., Wu, Y., Nguyen, H., & Johnson, A. (2019). The moment of truth: A Review, synthesis, and research agenda for the customer service experience. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 6(1), 89–113. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012218-015056

- Gruen, T. W., Summers, J. O., & Acito, F. (2000). Relationship marketing activities, commitment, and membership behaviors in professional associations. Journal of Marketing, 64(3), 34–49. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.64.3.34.18030

- Gutek, B. A., Bhappu, A. D., Liao-Troth, M. A., & Cherry, B. (1999). Distinguishing between service relationships and encounters. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(2), 218–233. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.84.2.218

- Henry, C., & Foss, L. (2015). Case sensitive? A review of the literature on the use of case method in entrepreneurship research. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 21(3), 389–409. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-03-2014-0054

- Ingram, S. J., & Yelowitz, A. (2019). Real estate agent dynamism and licensing entry barriers. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 10, 156–176. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JEPP-07-2019-0063

- Johnson, J. M., Nourse, H. O., & Day, E. (1988). Factors related to the selection of a real estate agency or agent. Journal of Real Estate Research, 3(2), 109. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=buh&AN=4479389&site=ehost-live&custid=s3912055 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10835547.1988.12090558

- Kara, A., & Petrescu, M. (2018). Self-employment and its relationship to subjective well-being. International Review of Entrepreneurship, 16(1), 115–140.

- Kautonen, T., Down, S., Welter, F., Vainio, P., Palmroos, J., Althoff, K., & Kolb, S. (2010). Involuntary self‐employment as a public policy issue: A cross‐country European review. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 16(2), 112–129. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/13552551011027002

- Kirkwood, J. (2009). Motivational factors in a push‐pull theory of entrepreneurship. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 24(5), 346–364. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/17542410910968805

- Kovács, G., & Spens, K. M. (2005). Abductive reasoning in logistics research. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 35(2), 132–144. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09600030510590318

- La Guardia, J. G., & Patrick, H. (2008). Self-determination theory as a fundamental theory of close relationships. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 49, 201–209. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012760

- Larsen, J. E. (1991). Leading residential real estate sales agents and market performance. Journal of Real Estate Research, 6(2), 241. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&db=buh&AN=4475388&site=ehost-live&custid=s3912055

- Larsen, J. E., Coleman, J. W., & Gulas, C. S. (2008). Using public perception to investigate real estate brokerage promotional outlet effectiveness. Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 11(2), 159– 178. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10835547.2009.12091645

- Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage.

- Love, P. E. D., Goh, Y. M., Hogg, K., Robson, S., & Irani, Z. (2011). Burnout and sense of coherence among residential real estate brokers. Safety Science, 49(10), 1297–1308. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2011.04.009

- Lydon, J., Pierce, T., & O’Regan, S. (1997). Coping with moral commitment to long-distance dating relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(1), 104–113. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.1.104

- Mäklarsamfundet. (2020a, September 8). Fakta och nyckeltal 2018. https://www.maklarsamfundet.se/media-opinion-analyser-och-rapporter/fakta-nyckeltal-om-fastighetsmaklarbranschen-2018

- Mäklarsamfundet. (2020b, September 8). Fakta och nyckeltal 2019. https://www.maklarsamfundet.se/media-opinion-analyser-och-rapporter/fakta-nyckeltal-2019-fastighetsmaklarbranschen-i-siffror

- Marques, C. S. E., Ferreira, J. J. M., Ferreira, F. A. F., & Lages, M. F. S. (2013). Entrepreneurial orientation and motivation to start up a business: Evidence from the health service industry. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 9(1), 77–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-012-0243-2

- Martin, R. W., & Munneke, H. J. (2010). Real estate brokerage earnings: The role of choice of compensation scheme. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 41(4), 369–389. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-009-9174-2

- Millán, J. M., Hessels, J., Thurik, R., & Aguado, R. (2013). Determinants of job satisfaction: A european comparison of self-employed and paid employees. Small Business Economics, 40(3), 651–670. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9380-1

- Moorman, C., Zaltman, G., & Deshpande, R. (1992). Relationship between providers and user of market research –the dynamics of trust within and between organizations. Journal of Marketing Research, 29, 314–328. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379202900303

- Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58, 20–38. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1252308

- Müller, G. F. (2015). Beruflishe selbständigheit [self-employment]. Ink. Moser (Ed.), Wirschaftspsychologie, Springer-lerbuch (pp. 343–359).Springer.

- NAR. (2020, September 8). Member profile. https://www.nar.realtor/research-and-statistics/research-reports/highlights-from-the-nar-member-profile#income

- Nuttin, J. (1984). Motivation, planning and action. Leuven University Press and Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Parker, S. C. (2004). The Economics of self-employment and entrepreneurship. Cambridge university press.

- Pearse, N. (2019). An illustration of a deductive pattern matching procedure in qualitative leadership research. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 17(3), 12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.34190/JBRM.17.3.004

- Price, L. L., & Arnould, E. J. (1999). Commercial friendships: Service provider-client relationships in context. Journal of Marketing, 63(October), 38–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1251973

- Ragin, C., & Becker, H. (1992). Casing and the process of social inquiry. In C. Ragin & H. Becker (Eds.), What is a case? Exploring the foundations of social inquiry (pp. 217–226). Cambridge University Press.

- Rosenbaum, M. S. (2009). Exploring commercial friendships from employees’ perspectives. Journal of Services Marketing, 23(1), 57–66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040910933101

- Salzman, D., & Zwinkels, R. C. J. (2017). Behavioral real estate. Journal of Real Estate Literature, 25(1), 77–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10835547.2017.12090455

- Schummer, S. E., Otto, K., Hünefeld, L., & Kottwitz, M. U. (2019). The role of need satisfaction for solo self-employed individuals’ vs. employer entrepreneurs’ affective commitment towards their own businesses. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research, 9(1), 63. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-019-0190-2

- Seiler, V. L., Seiler, M. J., & Webb, J. R. (2006). Impact of homebuyer characteristics on service quality in real estate brokerage. International Real Estate Review, 9(1), 44–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.53383/100068

- SFS 2011:666. Fastighetsmäklarlag. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/fastighetsmaklarlag-2011666_sfs-2011-666.

- Shah, S. K., & Corley, K. G. (2006). Building better theory by bridging the quantitative–qualitative divide. Journal of Management Studies, 43(8), 1821–1835. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00662.x

- Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of Management Review, 25, 217–266.

- Shepherd, D. A., Wennberg, K., Suddaby, R., & Wiklund, J. (2019). What are we explaining? A review and agenda on initiating, engaging, performing, and contextualizing entrepreneurship. Journal of Management, 45(1), 159–196. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318799443

- Staal Wästerlund, D., & Kronholm, T. (2017). Family forest owners’ commitment to service providers and the effect of association membership on loyalty. Small-Scale Forestry, 16(2), 275–293. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11842-016-9359-5

- Taylor, M. (1996). Earnings, independence or unemployment: Why become self-employed? Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 58(2), 253–226. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0084.1996mp58002003x

- Teixeira, C. (1998). Cultural resources and ethnic entrepreneurship: A case study of the Portuguese real estate industry in Toronto. Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe Canadien, 42(3), 267–281. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.1998.tb01895.x

- Uy, M. A., Foo, M.-D., & Song, Z. (2013). Joint effects of prior start-up experience and coping strategies on entrepreneurs’ psychological well-being. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(5), 583–597. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.04.003

- Verheul, I., Risseeuw, P., & Bartelse, G. (2002). Gender differences in strategy and human resource management: The case of Dutch real estate brokerage. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 20(4), 443–476. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242602204004

- Waller, B. D., & Jubran, A. M. (2012). The impact of agent experience on the real estate transaction. Journal of Housing Research, 21(1), 67–82.

- Warr, P., Bartram, D., & Martin, T. (2005). Personality and sales performance: Situational variation and interactions between traits. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 13(1), 87–91. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0965-075X.2005.00302.x

- Weick, K. E. (1992). Agenda setting in organizational behavior: A theory-focused approach. Journal of Management Inquiry, 1, 171–182. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/105649269213001

- Weinstein, N., & De Haan, C. R. (2014). On the mutuality of human motivation and relationships. In N. Weinstein (Eds.), Human motivation and interpersonal relationships (pp. 3–27). Springer.

- Wiklund, J., Nikolaev, B., Shir, N., Foo, M.-D., & Bradley, S. (2019a). Entrepreneurship and well-being: Past, present, and future. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(4), 579–588. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2019.01.002

- Wiklund, J., Wright, M., & Zahra, S. A. (2019b). Conquering relevance: Entrepreneurship research’s grand challenge. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43(3), 419–436. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258718807478

- Yavas, A. (1994). Economics of brokerage: An overview. Journal of Real Estate Literature, 2, 169–195.

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Yinger, J. (1981). A search model of real estate broker behavior. American Economic Review, 71, 591–605.

- Zhang, C., & Schøtt, T. (2017). Young employees’ job-autonomy promoting intention to become entrepreneur: Embedded in gender and traditional versus modern culture. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 30(3), 357–373. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2017.081974

Appendix.

Interview Questions

Service Landscape for the Brokerage

Do you say my customer – or a customer?

How do you view customer relations?

How many of your customers would you say you have a warm, neutral, or cold relationship with?

How do you think your customers feel about you?

Is it common that customers become your friends?

Origin of Business Opportunities

From where do your business opportunities arrive?

Motivation

What drives/motivates you as a broker?

Are customer relations important to you and, if so, why?

How important is it for you to gain/receive trust?

Preferred Relationships

Which type of customer relation do you prefer: warm, neutral, or cold?

How do you feel about being personal with your customers?

Have your opinions about customer relations changed since starting to work?

Outcomes of Preferred Relationships

Do your customer relations affect you?

Is it common that your customers want to hang out with you privately?

Does a network among customers exist?