?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Engaged students desire to do well, while course instructors endeavor to create a course environment that will achieve long-term mastery of the subject and student success in the classroom and beyond. Despite the effort put forth by both parties, the result is sometimes less favorable than expected. Studies have shown that people tend to overestimate their own abilities (“overconfidence”). When students are overconfident it leads them to believe that they know more than they actually do and consequently study less, while basing their expectations on what grade they would like to achieve, all of which further serves to compound the problem. There is no reason to believe that this does not also apply to real estate students. Indeed, using data from three different universities the authors seek to determine whether real estate students, both undergraduate and graduate, are able to accurately self-evaluate their own ability, both relative to their own performance, and vis-à-vis what they believed that the class average would be. We seek to determine if 1) students can properly self-assess their ability as measured by performance, 2) if any overconfidence exists relative to their expectations compared to their estimation of their peers, and 3) if overconfidence does exist, are there specific factors that influence them such as gender. The results presented in this paper are useful for a real estate instructor to manage expectations and provide a better learning environment.

Introduction

Each semester across the globeFootnote1, faculty in real estate prepare their courses with great consideration, diligently crafting lessons and assessments in a way that they feel will most effectively result in optimal student learning and long-term mastery of the subject. Within real estate education tracks at conferences, there are sessions on topics such as curriculum, learning outcomes and assessments, accounting for different learning styles, teaching critical thinking, and active learningFootnote2. The presence of these sessions reflects the desire to understand how to best promote comprehension and application of a topic in order to prepare students for a successful future. Further, numerous papers have been written on real estate education, from where it has been to where it is going, with work highlighting optimal and innovative pedagogy throughout. Despite all of this time and effort, instructors are not immune to common refrains from students saying things such as ‘I thought that I understood the material, why did I not do well on that exam?’ or ‘I’m an A student! I don’t get Cs!’ or ‘But I worked really hard, so I should have gotten a better grade!’ This is distressing and frustrating to both student and instructor alike, as it highlights a divide between expectation and outcome. This disconnect is further reflected in the opinion of employers that academic intuitions are not adequately preparing students with the skills required for them to be successful within their organizations. This employability issue has been researched by, for example, Hart Research Associates (Citation2015) and Mourshed et al. (Citation2012). Why is this incongruence occurring? With all of the educational research conducted, training of faculty in optimal teaching techniques, the preparation, time, and effort spent by said faculty, combined with students taking classes in subjects that they profess to have an interest in, success should be all but guaranteed for nearly every engaged student; is there something that we, as educators, are missing? The authors of this paper believe that there is, and that the issue is related to students’ own aptitude in effectively self-assessing their abilities, the resultant levels of overconfidence when this aptitude is lacking, and its impact on how students prepare for assessments. Indeed, while confidence, or feeling sure about one’s abilities, is a trait to be lauded, a reduced ability to effectively calibrateFootnote3 can lead to overconfidence, or the belief that you are better at something than you actually are. Thus, students who believe in their level of knowledge is sufficient to achieve a desired outcome on an exam, and is superior to that of their classmates, spend less time reviewing the material. Whereas those students who are insecure in their level of knowledge, or understand what they need to spend more time studying, tend to study more efficiently.

Although the topic of student overconfidence and the ability to self-assess has been widely examined, it has typically been undertaken in an experimental setting, or over a specific semester or class. This paper is the first to address this topic specifically targeting students with an interest in the study of real estate. Additionally, upon analyzing the relevant literature, to our knowledge it is the first to involve more than two universities across multiple courses, though predominantly real estate focused, over multiple years. And while we do not currently cover the effectiveness of specific solutions or pedagogical adjustments intended to help rectify this effect in this paper, the identification of this occurrence, and its prevalence among real estate students, will help generate awareness among instructors so that they might better manage expectations, and develop means to help students more accuratelyFootnote4 self-assess within the framework of their individual courses.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: The next section will provide a general overview of the literature in the area of real estate education followed by a more in-depth analysis of selected works pertaining to student overconfidence and self-assessment. This is followed by sections addressing data and methodology, descriptive statistics, and results. Finally, we will conclude with general remarks along with research-based pedagogical suggestions regarding ways instructors can help minimize student overconfidence in their courses.

Literature Review

Within the study of real estate, educational research has not only mirrored the overall higher-educational concerns about learning, skills, and employability, see for example Hoxley et al. (Citation2011), Poon (Citation2012), and Poon (2014). Other papers have explored the optimization of individual courses, examining the best ways to engage students and promote deep learning and subject matter retention, see for example Anderson et al. (Citation2000), Butler et al. (Citation1998), Charles (Citation2016), Palm and Pauli (Citation2018), and Raftery et al. (Citation2001), which are most closely aligned to the issues of learning observed in this study. Many of the active learning suggestions found in these papers incorporate the concepts expressed in papers such as that of Bjork et al. (Citation2013), whereby a student who is active in the process of learning is the most efficient in retaining information.

The Impact of Poor Metacognitive Ability on Study Habits and Learning Outcomes

Interestingly, Bjork et al. (Citation2013) points out that due to metacognitive illusions (false beliefs about how one learns or remembers best), and a lack of ability of most students to accurately self-assess their own performance, students often believe that bad learning strategies are good, and that good ones are bad, the echoes of which are found in the student feedback responses in Raftery et al. (Citation2001). The authors, using a sample of 3rd year real estate students in Hong Kong, discussed the introduction of problem-based learning into the curriculum, a common theme across the above papers as well. Although students’ responses stated that while they had found problem-based learning useful and a good tool, 70 percent also said that it increased their workload. Further, the authors themselves stated that they were not convinced that the students had truly been persuaded of the benefits of such learning. Therefore, despite having achieved a demonstrated and acknowledged deeper level of learning, consistent with Bjork et al. (Citation2013), students would perceive the added work as inefficient and revert to more traditional, ineffective, methods of study.

Looking at U.S. undergraduate students, Dunlosky and Rawson (Citation2012) find that absolute accuracy of students’ judgements is crucial for effective learning. Students make judgements on how to study based on these self-assessments, and the authors found that those who thought that they knew the material well, but in actuality did not (overconfidence), stopped studying sooner, had lower levels of retention, and ultimately did not meet the assessed learning objectives. Bjork et al. (Citation2013) similarly found that once students believe that they know something, a belief typically resulting from traditionally employed but inefficient study methods, they cease to study it, which is usually too soon.

Further, how students elect to study is related less to empirical assessments, such as past performance, but rather to a current judgement of knowledge, regardless of the presence of flawed awareness and understanding of one’s own thought process (metacognition) and subsequent judgements of learning (Metcalfe & Finn, Citation2008). Indeed, students may not distinguish between knowledge and effort, as measured through hours studied. In equating the two, students who study for longer periods of time have a greater expectation of performance regardless of their actual mastery of the subject, see for example Nowell and Alston (Citation2007), Bandiera et al. (Citation2015), and Nelson and Leonesio (Citation1988). If students are unaware of what they do not know, believe that they know more than they do, and base their studying habits around these flawed assessments, then how can they get the most out of their educations? Indeed, it would seem that these areas of research indicate that there are still questions regarding how to achieve the goals associated with deep learning and successful student outcomes. Thus, in discussing the literature related to inaccurate self-assessment and overconfidence, we identify an additional impact on optimal learning that should be considered by faculty in their assessments.

The literature on student self-regulated learning drills down into this area further, addressing the ability to accurately know how well one is doing at any given task. This ability is most frequently mentioned in literature as related to metacognition, self-assessment, or self-awareness. Indeed, the finding that students, or anyone else for that matter, evaluate themselves more favorably relative to others is not a new one. This better-than-average effect has been a fundamental concept in social psychology, and has been widely studied since the 1980s. The better-than-average effect represents the unrealistically positive view people have of themselves and their abilities However, with the work of Kruger & Dunning, this effect was catapulted into the awareness of the general public with their findings that ‘when people are incompetent in the strategies they adopt to achieve success and satisfaction, they suffer a dual burden: Not only do they reach erroneous conclusions and make unfortunate choices, but their incompetence robs them of the ability to realize it. They are left with the impression that they are doing just fine.’ (Kruger & Dunning, Citation1999 p.1121). Interestingly, the miscalibration of one’s ability is not limited to those lacking in skill or intelligence. Indeed, being aware of what there is yet to know resulted in skilled students underestimating their abilities. They were aware of how much they did not know and therefore they were more likely to discount what they did know. This is commonly referred to as the below-average effect.

Course Types and Their Impact on Students’ Metacognitive Accuracy

Boud and Falchikov (Citation1989) and Falchikov and Boud (Citation1989) examine the factors that are commonly included in research related to student self-assessment resulting in a critical analysis and a meta-analysis, respectively, of work that had examined student self-assessment. Overall, they found that in different situations, people over or under estimated themselves (though they do note that the choice of statistics used in individual studies influenced results), with the better academic performers tending toward underrating, and the academically weaker students tending toward overrating, their abilities as expected. This will be discussed in greater detail below. They found that well-designed courses resulted in better self-assessment, as did those in the broad subjects of science (hypothesized to be a function of the unambiguous nature of assessments). Results related to gender were inconclusive, but relative to age, the authors found that it was the level of the course rather than the age of the participants that mattered. College seniors taking introductory classes fared no better at self-assessment in those courses, but students in upper-level courses (also presumably seniors) were more able to reliably self-assess.

Relative to the concept of the ambiguity of assessments, the work of Moreland et al. (Citation1981) sought to determine if the cause of poor performers’ inability to effectively assess resulted from a lack of understanding relative to the criteria on which they were being graded. Thus, students were given the grading criteria, and asked to use it to assess the expected grades on exam essays, as well as the essays of their peers. They found that while all students were relatively accurate in the assessment of their peers, the poor performers in the class were generally unable to apply the same assessment criteria to their own work, thinking that they did a much better job on their essays than they actually did. Those authors hypothesized that poor-performers are more likely to be surprised by their grade because of their lack of ability to effectively self-assess, and their responses to such feedback would tend to reflect ‘blame’ on external factors such as task difficulty, or instructor, rather than internal factors such as ability or effort. This externality of blame was likewise identified in Karnilowicz (Citation2012).

Similarly, Nowell and Alston (Citation2007) found that ambiguity in not only assessments, but final outcomes also contribute to student grade expectations among American economics students. Courses that had exams weighted more heavily than other assessments reduced the students’ level of overconfidence, and an instructor’s willingness to ‘curve’ grades, which could be seen as an external factor to poor-performers, resulted in increased levels of student overconfidence. Interestingly, the authors also found the instructor’s rating also significantly influenced overconfidence, as the higher the students’ grade expectations were, the better that instructor’s anonymous student evaluations were. However, it is not just the external relationship between instructor evaluations and higher anticipations of grades that influences overconfidence, it is also the desire of the student themselves.

Wishful Thinking and Student Performance Expectations

In looking at the impact of wishful thinking on grade expectations Serra and DeMarree (Citation2016) had students report desired and expected grades for both the final exam and the course overall either before, or directly after the exam, or separately over the course of all four exams. While students’ post-exam assessment was more accurate than their predictions, their assessments still strongly related to their desired grades. The authors noted no improvement when assessing over time. Rather, their stated grade desired decreased over time, which still drove the predicted result. Saenz et al. (Citation2017) replicated and further expanded on this work. Using four studies over six exams they demonstrated the biases inherent in grade prediction with “ideal” and “minimum acceptable” predictions having a greater impact on expected outcomes than rational determinants such as attendance, study habits/preparation, and/or prior performance. However, they also found that engaging in a lecture-based ‘intervention’, consisting of education on overconfidence bias, the pitfalls of using motivational goals to form predictions, and their own previous prediction relative to their performance, improved the accuracy of predictions.

Conversely, we identify the impact of expected grades on achieved grades with Ballard and Johnson (Citation2005) demonstrating the self-diminishment bias. Using four sections of a U.S. microeconomics course, the authors surveyed students on a variety of factors relevant to academic aptitude, while also asking students to predict the course grade they expected to achieve. While all students overestimated their final course grade by roughly the same amount, women expected their grade to be lower than the men by one-fourth of a letter grade. After controlling for variables such as mathematical ability, family background, and academic experience, it was found that this initial lower expectation was largely self-fulfilling, resulting in lower overall grades, though no improvement in calibration. They also note that their findings reflect those previously identified in the U.S., U.K., and Canadian studies.

The Gender and Age/Experience Influence on Self-Assessment

Looking further at gender, Grimes (Citation2002), provided introductory economics students a total of three instruments of self-assessment: One 48 hours prior to the exam, one on the day of the exam, and one immediately after the exam. Each of these instruments asked students how they expected to do, or did, on the exam. They found that women, though still overconfident, were better at revising their final expectations of performance over the three instruments than the men. However, they also found that in students’ overall overestimation of performance, gender was not a significant factor. Conversely, Nowell and Alston (Citation2007) found men to be 9 percent more likely to overestimate their grade than women.

Grimes (Citation2002), contrary to Falchikov and Boud (Citation1989), did find that age tempered overconfidence, with older students in the introductory course being less overconfident. However, Nowell and Alston (Citation2007) found results in-line with the meta-analysis whereby they looked at two courses, introductory economics and quantitative analytics, and asked students to predict their final grades relative to their respective course, and found that students in the economics course were far more overconfident than the upper-level analytics class regardless of age.

These variables, age versus level of the course, tie into the concept of domain familiarity, or previous exposure to the subject matter. Research has found that previous knowledge of or prior exposure to a subject, results in greater levels of overconfidence regarding ability in that subject, see for example Ballard and Johnson (Citation2005), Dinsmore and Parkinson (Citation2013), and Grimes (2002). This domain familiarity tends to be used by students to determine what to study. Indeed, Shanks and Serra (Citation2014) found that students spent more time studying lesser-known topics, and the least time on topics that they perceived to know well, the combination of which resulted in an overall lower assessment performance. This is interesting, given the basic premise of metacognition whereby novices, or those with less aptitude in a certain area of study, are less likely to possess metacognitive accuracy, although they can, at least to some degree, develop their metacognitive ability for self-assessment, see for example Burson et al. (Citation2006), Karnilowicz (Citation2012), Kennedy et al. (Citation2002), Kruger and Dunning (Citation1999), Miller and Geraci (Citation2011), and Zell and Krizan (Citation2014). However, the findings of Boud et al. (Citation2015) disagree with this premise, finding that there was no improvement in calibration for low-performing students over time. Regardless, it would appear that while students may be able to improve their accuracy in determining their level of knowledge, this does not necessarily mean that they get better at the underlying subject or skill. Further, it would appear as though it is primarily those who are less skilled that can be taught to improve their levels of self-awareness.

Indeed, Kennedy et al. (Citation2002) asked U.S business and sociology students, both graduate and undergraduate, drawn from two schools, to estimate their performance on exams immediately after completion. Results were divided into quartiles, with the lowest performing quartile continuously overestimating their performance, and by far greater margins than the higher performers. As noted above, these margins decreased over time, likely through the iterative feedback process of multiple exams, and allowed them to exhibit somewhat more accurate self-assessments. However, whereas the high performing quartile was mixed regarding overestimation, they did not get better at self-assessment over time. Though this might seem contradictory to domain familiarity, whereby one might think that as a student progressed through courses they would become more overconfident in their abilities, the authors indicate that while all students exhibit overconfidence in general, higher-achievers, or those most likely to advance in a particular area of study, are more likely to know what they don’t know, tempering the overconfidence effect in those classes.

The Prevalence of Metacognitive Errors

Similar to the results in all studies,Footnote5 Händel and Dresel (Citation2018), using a sample of German undergraduate education students, found that students at all levels have metacognitive weaknesses. Indeed, this raises the question as to whether students who are less able to accurately self-assess, make up the bulk of these studies. Kruger (Citation1999), found the results to be task dependent, with lower performers more overconfident on easier tasks, but less overconfident on harder ones. Overall, Kennedy et al. (Citation2002) found that when the mean percentile for task performance dropped below 50 percent, the lower performers were better at estimating than the high performers. Further, Burson et al. (Citation2006), building on this work by giving a quiz to volunteers, and asking both how many questions out of 20 they thought they got correct, and the percentile rank they thought that they would fall into in relation to their peers in the study, found that everyone at all skill levels are subject to similar degrees of error. Where there was a difference in estimating, the highest performers underestimated and the lowest performers overestimated, cancelling each other out, calibrating at about 50 percent.

Data and Methodology

Based on the relevant literature analyzed above, in examining the performance of a selection of students choosing to study real estate, either as an elective or as part of a dedicated degree, the authors sought to test three specific hypotheses related to student’s ability to accurately self-assess, or calibrate:

Students of real estate consistently fail to effectively self-assess their performance on any given exam.

Students of real estate consistently fail to effectively self-assess their own abilities relative to the abilities of their peers.

In the presence of miscalibration, there are factors such as age/experience or gender that impact both the level of individual overconfidence and the ability to correctly assess performance relative to their peers.

Subjects in this study came from three different universities: Texas A&M University–College Station, The George Washington University, and the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign in academic years 2016/17 and 2017/18, in real estate courses taught by two different instructors of two different genders. Given that the study reflects students with an interest in real estate studies, and that it is commonly accepted in the literature that distortions of performance holds, regardless of institution, level, or instruction, see for example Moreland et al. (Citation1981) and Kennedy et al. (Citation2002), the decision was made not to include school attended or instructor as a variable. Both graduate and undergraduate courses were included, with graduate courses serving as a proxy for age and experienceFootnote6. The scope of this study is to help identify the potential presence of poor student self-assessment in the classroom, with the aim of assisting instructors at all levels optimize student learning through increased awareness of the problem. Unfortunately, FERPAFootnote7 made it impossible for the authors to record potentially sensitive variables such as GPA, standardized college entrance exam scores, race, mathematical ability, and family background, which have been examined as potentially predictive factors regarding student overconfidence. On the other hand, the authors are able to use student information that is known from classroom presence, namely gender identification and the general age/course level associated with the students.Footnote8 In addition, of these potential variables, only FERPA-protected GPA and performance on standardized entrance exams are found to have a statistical significance on predicting overconfidence. Nevertheless, due to data-inaccessibility these two variables are not considered in this study.

Although this study examines students who voluntarily select real estate as a course of study, either as an elective in a non-specific major, or as a requirement for a real estate specific degree, the authors also collected data from one required, non-real estate, business course as a comparison, namely Financial Management and Markets. In order to control for grading subjectivity as addressed in Falchikov and Boud (Citation1989), as well as working to decrease overconfidence through task objectivity per Zell and and Krizan (2014), all exam questions were quantitative, objective, and unable to be subject to bias by the instructor. Though the authors acknowledge that other forms of assessment are frequently employed by instructors, and were also utilized in these classes, the existing body of research suggests that classes mostly use exams and other less ambiguous assessment mechanisms, see for example Falchikov and Boud (Citation1989), Karnilowicz (Citation2012), and Nowell and Alston (Citation2007). Hence the authors elected to utilize this form of assessment that is least associated with overconfidence.

The total number of exams considered in our study was 1,093, with a gender breakdown of 380 exams taken by female students, 713 exams taken by male students, 889 exams taken by undergraduate students, and 204 exams taken by graduate students. Each individual exam is a single data point given that, as noted above, research has shown that without specific intervention students are unlikely to improve metacognitive ability, and that the impact of prior exams on future self-evaluation is not a strong or consistent component of estimation, see for example Saenz et al. (Citation2017). Furthermore, since courses varied in the number of exams given (2–3), the study was not focused on the ability of students to self-assess over time and therefore did not track specific students, and some students would omit data in one or all of the questions asked, resulting in an unusable datapoint. Omissions were assumed unintentional based on the typical responses of students upon their discovering that they had not participatedFootnote9. No student in our sample opted out of participation in the study. Students received extra credit based on their assessment of their expected score, though they were asked to provide responses to all questions.

All exams had the following message on the first page of their exam:

Extra Credit Opportunity: What percentage score, out of 100%, do you think you will get on this exam? If you are within one percent either way, you will get 5% extra credit on this exam. Please note that if you do not answer the second question you will not receive the extra credit even if you correctly estimated your own percentage score.

Expected Percentage Score: __________

Expected Average Percentage Score for the Class as a Whole: ________

Did you answer the above before_____ or after____ you completed the exam?

Check here___if you do not want the above information used anonymously for the purposes of academic research.

As stated, students had the opportunity to earn an additional 5 percent extra credit on each exam by correctly assessing their grade. The authors allowed some standard level of error with respect to the self-assessment of students. From the beginning, the authors anticipated gathering these data over a period of years. Consequently, to be consistent across time and since it was known that the sample size was going to be quite large, the range around the 95% confidence interval would be rounded to ± 1. Thus, students were allowed ± 1 from their response to get the extra credit. For example, if a student wrote that they had earned a score of 90, they would get the extra credit if their grade reflected a score of between 89 and 91. The amount of extra credit, as well as the allowed margins of error, was determined from trial and error in semesters previous to this study.Footnote10 The question whether the student answered the questions before or after the exam was also added later, after observing that some students were estimating their grade prior to taking the exam. This behavior reflects the “wishful thinking” and expectation behavior identified by Serra and DeMarree (Citation2016). Although not specifically examined in this paper due to its small sample size, the inclusion of this question will be used to evaluate the accuracy of student estimations of performance that are based upon their desired outcome, thus prior to the exam, versus the accuracy of students who based their self-assessment ex-post. None of the populations shown in Exhibit 1 are normally distributed, nor are the variances equal, rendering the traditional t-test inappropriate. As such, we employ a nonparametric sign test, similar to one used by Clayson (Citation2005).

The result of the sign test reflects the probability that the values of one population, in this case the predicted grade, is larger than the values of a second population that is paired with the first, which is the earned grade in this study. In generic terms, we use the following one-tailed test:

where p is the probability that X will be smaller than or equal to Y. For example, in the first hypothesis X would be the predicted grade, and Y would be the earned grade. Each paired observation received either a “-” or a “+“, depending on whether X is smaller than or equal to Y or Y is larger than X, respectively.Footnote11 The original hypotheses can now be stated in terms of a testable null hypothesis: P(X ≤ Y) is equal to P(Y > X) and both are equal to 0.5. This results in a left-handed-tailed test:

Thus, the testable null hypothesis was that the probability of a predicted grade being less than the earned grade is at least 50%. If that was not the case, we rejected the null hypothesis finding that students did, indeed, consistently overestimate their expected performance on a given exam as expected. The results of these tests are summarized in Exhibit 5.

Descriptive Statistics

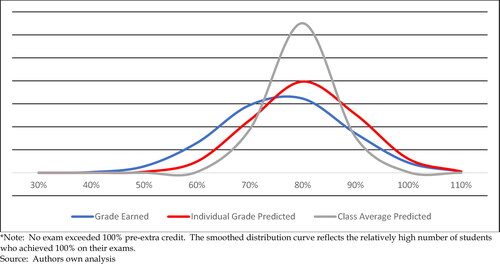

The distribution of the sample is shown in Exhibit 1, where the blue distribution reflects the each of the grades earned across all exams, with an average of 76 percent and a standard deviation of 11.8, the red distribution represents students’ predicted individual grades for all exams with an average of 81 percent and a standard deviation of 10, and the grey distribution reflects the students’ predicted class average on each exam, with an average of 80 percent with a standard deviation of 6.

Exhibit 2 provides an overview of the data collected for this study. The gender makeup per class skews toward male, with only the Spring, 2017 undergraduate real estate finance class achieving something close to gender parity. Additionally, the percentage of students who received the extra credit on any given exam ranges from 0 percent to a high of nearly 30 percent.

Exhibit 2. Sample Data Per Course and Per Exam.

Analyzing the performance of all students, as evidenced from the data in Exhibit 3, we see that the average exam score was 76.3 percent. Though not shown, 0.8 percent of students scored a perfect 100 percent which, as can be seen in Exhibit 1, affected the smoothing of the distribution curve for earned scores. Additionally, though not shown, there was no significant difference in the average earned scores based on the faculty instructing. The average expected grade on the exams was slightly higher, in keeping with our hypotheses. The average estimate for overall class performance was only slightly lower than individual performance at 80 percent. Overall, students were able to accurately self-assess and earn the extra credit on 13.5 percent of all exams. It should be noted, however, that based on the eligibility for earning the extra credit, a student may still overestimate their performance and earn the extra credit.

Exhibit 3. Descriptive Statistics for All Exams.

Looking at Exhibit 4, the groups were then compared to their peers, such as undergrads relative to undergrads, given that the groups themselves made up very different proportions of the overall sample. Surprisingly, graduate students were less likely to get the extra credit, despite that previous research has shown that upper-level students are less likely to be overconfident. It could be that although these were graduate level courses, the material was still relatively unknown to the students. The finding that age has no relationship with ability to self-assess is in line with results found in Falchikov and Boud (Citation1989) and Nowell and Alston (Citation2007), though contrary to Grimes (2002). Indeed, given that the percent of graduate students’ exams that show overestimation of grades is roughly the same as the undergrad exams, we might assume that there is either domain familiarity bias or that the material is still at the introductory, albeit graduate introductory, level for students; or both. In all, roughly two thirds of exams showed student overestimation of their grades relative to their actual performance. When looking at the performance within peer groups (males to males, grads to grads, etc.), these numbers are consistent. However, as expected, those exams taken by males were more likely to show overestimation of their performance and that exams taken by females were less likely to reflect overestimation of their performance. Interestingly, it appears that the exams taken by students in the general business class were more likely to overestimate their performance, though the authors do note that this was a single class, and constitutes only 11 percent of the sample. Looking at Exhibit 4 it is interesting to note that for all groups students were less likely to overestimate their performance relative to their peers than they were their own performance, which is consistent with the results found by Merkle and Weber (Citation2011). They posit that this result was either based on the central tendency bias, or the theory proposed by Thaler and Sunstein (Citation2008) who suggest that students are too modest to state that they are better than their peers, even when they believe that they are.

Exhibit 4. Descriptive Statistics of All Exams Relative to Students’ Peer Group.

Though not shown, the number of exams whereby students based their judgement of learning on the aforementioned “wishful thinking” or desired grade, as evidenced by their stating that they made their estimate prior to taking the exam, was a small sample, making up less than 4 percent of total exams. Of these, only 2 of these exams received the extra credit. Interestingly, not all students were consistent with the timing of their self-assessments, with some students switching between pre- and post-exam over the course. This reflects the general tenor of the existing body of literature demonstrating that students base their metacognitive decisions on imperfect information rather than an accurate assessment of their abilities.

Results

Analyzing the results shown in Exhibit 5, it is clear that although both males and females overestimate their own grades, exams taken by females show more skill in self-assessment than ones taken by males. Indeed, the absolute differences in the summary statistics presented in Exhibit 4 reinforce this point. The number of exams taken by males, as a percentage of their peer group, that show overestimation of their expected grades are clearly higher than those taken by females who took any given exam, namely 67 percent versus 59 percent. This is in line with Ballard and Johnson (Citation2005) and nearly identical to the findings of Nowell and Alston (Citation2007). Age or experience seems to matter given that although both graduate students and undergraduate students overestimate their grades, the younger and more inexperienced undergraduate students exhibit poorer self-assessment skills. Indeed, this again leads the authors to believe that it is likely domain familiarity that is affecting graduate students rather than the course level. Looking, too, at the comparison between the students who have chosen a real estate course versus students engaged in a required business class, it appears that students engaged in real estate studies are relatively less adept at self-assessments, though both groups overestimated.

Exhibit 5. Results of Student Exam Performance Relative to Self and Peer Estimations.

When looking at the results for students vis-à-vis their peers, as measured by their estimate of the class average, we find similar results with some exceptions. First, although all students significantly overestimate their performance relative to their peers, the Z-test scores for exams taken by males and females separately is nearly identical. It seems that students have a better sense of their relative standing in the class than their assessment of their own capabilities. This supports the hypothesis by Clayson (Citation2005) that students have a common subjective level of performance and compare their own performance against that level. Nevertheless, on average, students believe that they are above average, except graduate real estate students and non-real estate students. Both of these results are in contrast to those reported by Kennedy et al. (Citation2002), who found no discernable difference across disciplines or between graduate and undergraduate students. Regarding the latter, we note the possibility, as expressed by Karnilowicz (Citation2012) that high achievers might self-diminish in order to be more positively rated by others, as we would assume that those students who have qualified for graduate school would classify as high-achievers. Additionally, our results could also reflect the work of Burson et al. (Citation2006) who find that high-performers, though no better calibrated for self-assessment, are more sensitive to where they stand relative to others. Though it can be considered that though the majority of class sizes were within a similar range, the larger size of the undergraduate class may have inhibited knowledge-sharing, or differently stated: The larger size of the undergraduate class may result in less transparency when it comes to class averages. This has not been controlled for in previous studies and would therefore be of interest for future research. With regards to the results of the student exams of the general business class, the authors were somewhat surprised by the results. These students were not shown to overestimate their own abilities relative to their peers, though they consistently overestimated their own abilities. Again, the authors note that the population of non-real estate students in this sample is small since only one non-real estate class was included, hence more work would need to be done using a larger sample, or compare different fields of study, e.g. Marketing or General Business versus Real Estate. This should show whether the results found here regarding self-assessment versus peer assessment, as well as the results relative to the degree to which overconfidence occurs, are consistent.

Conclusions

As with all students, real estate students are not very adept in the area of self-assessment and, indeed, it would appear that those interested in this area of study are even less skilled in metacognition and judgements of learning than their general business cohorts. On average, the exams of female students reflected more skill in estimating their own grades, and exhibited lower levels of overall overconfidence. Interestingly, whereas graduate student’s exams were less likely to reflect overconfidence in their self-assessments, they were also the group least likely to accurately self-assess and achieve the extra credit. Any overconfidence exhibited by these students might be related to domain familiarity. Additionally, if we assume that those who qualify for graduate school are high-performers, it is likely that all effects are tempered by the presence of the below-average effect given that research has shown that high-performers also possess a general lack of metacognitive skill. Interestingly, all students are somewhat more astute when it comes to judging their performance vis-à-vis their peers, exhibiting lower levels of miscalibration in that regard. However, of all the categories, graduate students were the most attuned to their abilities relative to those of their classmates. Overall, however, it does appear as though students who choose to take real estate classes have a high degree of overconfidence, and a lower facility for engaging in accurate self-assessment in these classes.

There is another conclusion that we can draw from this work: Most students are essentially constantly disappointed by their grades. This must be an unremitting source of stress for students who believe that they know more than they actually do, who base studying strategies on biased judgements of learning that often result in the amount of time spent studying not necessarily reflected in their outcomes, and for those whom their professed area of interest might not be compatible with their abilities. This is also wearing on instructors who base the entirety of their teaching life working to help students achieve long-term learning and positive outcomes, and experience a sense of failure when this is not accomplished. Furthermore, instructors are also the ones who bear the personal and professional consequences of students with low subject skill and poor metacognitive abilities. These students will likely seek to deal with their disappointment through negative feedback and poor faculty evaluations because they are cognitively unable to understand that their own actions are responsible for their low scores.

To help alleviate these problems, it is imperative to adjust student expectations and position students to be good stewards of their own learning. Kennedy et al. (Citation2002) note that the more overconfident students are, the less likely they are to undertake studying measures that would soften the impact of error. Thus, it is important that we as educators work to reduce overconfidence in the classroom. Consequently, a suggested course improvement is that a professor should ask the students upon taking their first exam to estimate their own grade and the class average. Based on the results presented in this paper, it is safe to predict that most students will overestimate their own performance, both relative to their actual performance on the exam and the estimated and real class average. When returning the first exam, the instructor should also discuss the results of the grade estimation. An example is given in Exhibit 6 below.

Exhibit 6. Template for Instructor Discussion of Performance/Estimation.

There are enough data in this table for each student to self-identify especially if the instructor has returned the exams on which the estimates are recorded. A student is now confronted with how much s/he overestimated her/his own performance. What also should be pointed out is when students thought they performed better than the class average but in reality, performed worse. For example, students 4 and 5 thought that they performed better than the average but in reality, they performed worse. The situation for Student 5 is even worse, because s/he underestimated the true performance of her/his classmates, i.e. 79% class average estimate versus a real class average of 81%. By discussing this after the first exam the students hopefully will adjust their expectations and the instructor can help those students who overestimated their performance to adopt more effective study techniques. This is an example of what Saenz et al. (Citation2017) term an intervention, whereby students are made aware of their previous bias in self-assessment, and educating them on why it is harmful, helping to decrease overconfidence levels on the next exam.

In addition, the literature points to a number of pedagogical suggestions, understanding that one size will not fit all, to try to help students become sophisticated learners who are more accurate in their self-assessment. First and foremost, Bjork et al. (Citation2013) recommend instructors to make students more active participants in the learning process. Many of the real estate education articles cited above relate specifically to this idea, namely that when students are encouraged to interpret, connect, and interrelate information, it will be more easily imprinted on our memories. Such learners also understand that our minds do not simply ‘replay’ information once known. Instead, the practiced ability to recall information is as much of a key feature to learning as the knowledge itself. Hence, instructors should engage in the use of techniques that both relate new concepts to known anchors as well as those that require students to repeatedly access and apply concepts. This should result in students becoming more confident in accurately gaging what they actually have retained and what they should study more. Indeed, frequent assessments such as homework, assignments, quizzes and exams are key to spacing out studying for all topics and providing feedback, with Kennedy et al. (Citation2002) suggesting frequent testing as a good strategy. It should be noted, however, that when it comes to different types of assessments throughout the course, Boud et al. (Citation2015) found that the multiple assessment types that are used in order to accommodate different learning strategies actually makes it more difficult for students to calibrate. Indeed, Nowell and Alston (Citation2007) have found that courses that have exams more highly weighted reduce overconfidence. In addition, instructors should promote the use of self-testing as a means to study rather than a means of assessment, which is advocated by Bjork et al. (Citation2013) and Dunlosky and Rawson (Citation2012).

Though if one is going to engage in other forms of assessment, Falchikov and Boud (Citation1989), Karnilowicz (Citation2012), and Kennedy et al. (Citation2002) all advocate for the use of non-ambiguous assignments, with clear expectations and grading rubrics.

Kennedy et al. (Citation2002) strongly advocates for the use of feedback, and suggests that possible effective methods would be in the form of either feedback in the form of discussions between peers or student to professor, or in the case of alternative assignments, those which allow for submission with feedback over multiple drafts of papers. However, while Bandiera et al. (Citation2015) also advocates for the use of feedback they also include the caveat that states that feedback most benefits those who are already capable; thus, it has less of an effect on poor-performers.

Finally, with regards to reading, it might help to minimize or eliminate the use of ‘key terms’. Though the placement of definitions and key terms at the ends of chapters seems like an efficient aid to learning, Dunlosky and Rawson (Citation2012) have found that it actually promotes bias as students base their judgments of learning on term familiarity rather than an actual understanding of the meaning of the terms at a conceptual level. Thus, they believe that they know the definition of something simply because they recognize the term but are unable to effectively recall it at will.

In conclusion, as the authors have noted, there appears to be no single mechanism for addressing the ability for students to accurately self-assess, and reduce the overconfidence that is detrimental to student learning. However, we also believe that in being aware of this effect, educators can work to minimize uncertainty whenever possible, and have a greater level of understanding of what is occurring among their students.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Andrea Halpern (Bucknell University) and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and feedback.

Notes

1 This global focus reflects the consistency of research results in this area regardless of nationality studied. Within the works cited, samples reflect students in Australia (Boud et al., 2015; Karnilowicz, 2012), Germany (Händel & Dresel, 2018; Merkle & Weber, 2011; Pieschl, 2009), Hong Kong (Raftery et al, 2001), the United Kingdom (Bandiera, 2015; Poon, 2012, 2014), and the United States (all other works, with some results reflecting previous literature from other countries not mentioned or cited here. See Ballard & Johnson, 2005 as an example).

2 Some examples from the American Real Estate Society (ARES) Annual Conferences include: Global Real Estate Education Around the World: Curriculum Comparison and Learning Experiences; Sustainable Real Estate in the Curriculum; Learning Outcomes and Assessment of Real Estate Courses; The Importance of Teaching: Engaging Different Learning Styles; Experiential Learning: The What, How and Why, Effective Case Studies; Using Competitions, Technology and Professional Associations in the Classroom; Global Competency for Students, How to Teach Critical Thinking?

3 The term “calibration” is commonly used in metacognition research to describe how well individuals are able to understand what they do or do not know. Per Garavalia & Gredler, (2003) as cited in Pieschl (2009, P.4), it is the “extent of congruence between students’ estimates of their capabilities [metacognitive judgement] and their actual performance [criterion task]”

4 Social psychologists, such as in the seminal work of Kruger and Dunning (Citation1999), use the term “competent” to describe the ability to be consistently accurate in one’s judgement, and “incompetent” to describe one who is prone to be incorrect in one’s judgement. Based on the potentially provocative nature of those terms, the authors have chosen to utilize ‘accuracy’ and ‘ability’ to convey the same information throughout this paper.

5 The authors did not find any papers that did not contain results identifying metacognitive errors in self-assessment.

6 The use of graduate courses as a proxy for age/experience reflected the student demographic for each class. Non-traditional students were not identifiable at the undergraduate level with predominantly, if not exclusively, traditional college-aged students. Graduate-level classes were predominantly specialized real estate classes taken later in a program. This proxy is consistent with the age differentials found in existing literature, such as high school versus college, and/or lower versus upper-level courses to denote age and/or experience, see for example Falchikov and Boud (Citation1989) and Grimes (Citation2002) or graduate versus undergraduate students in Kennedy et al. (Citation2002).

7 In the United States, the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) protects the privacy of student education records, and cannot be accessed without obtaining a legal waiver from the student. Under certain conditions, such data may be accessible for the purposes of research. However, it would not be available to individual instructors without the consent of each individual student.

8 Even if instructors would have asked the students to self-report these variables, research has shown that students experience memory distortion when self-reporting GPA and standardized exam scores, resulting in an inaccurate data, see for example Shepperd (1993).

9 There were a total of 26 exams where students did not provide a response to the extra credit, and no exams where the student elected not to participate in the study. Additionally, no single student had more than one exam removed from the sample for an omitted response.

10 An incentive greater than 5 percent resulted in students purposefully skewing their responses down so that the extra credit would compensate for a lower than expected grade, which was more valuable to them than aiming for a higher grade. Asking for an exact statement of their earned grade was deemed too daunting and disincentivized responses. Creating a larger margin of error with a lower incentive allowed for many more students receiving extra credit without improving the accuracy or numbers of responses.

11 When a student correctly estimated their exam grade, within the 1 percent margin in each direction as described in the data, the paired observation was not removed from the data set used in the test; rather, they were pooled together with those who underestimated their grade.

12 There are various reasons why the number of students vary across exams: 1) Not all students attempted to earn the extra credit, 2) Students dropped the class, 3) Students missed an exam, opting to forego it in exchange for another assessment.

13 This exam was optional based on previous exam scores, with students being allowed to drop the lowest of their three exams i.e. if you were happy with your two previous exam scores, then you could not take the last exam and that score of 0 would be dropped. It was considered that if we assumed that all students who were low-performers and poor at accurate self-assessment would opt to take Exam III, it might skew our results. However, an examination of previous exams revealed that a nearly equal number of students who previously earned the extra credit who took Exam III as those who did not. Finally, not all low-performers opted to take the exam, and not all high-performers opted out of the exam. The latter is consistent with high achievers wanting the option to improve their overall grade. Given the fact that the number of those who did not take Exam III comprised only about 2 percent of the overall sample, as well as the inclusion of exams of students who subsequently dropped the course, or other exams of those students who either opted out or forgot to participate in a specific exam, excluding this specific exam would be inconsistent with all other measures, and this decision was in-line with the work of Miller and Geraci (Citation2011).

References

- Anderson, R., Loviscek, A., & Webb, J. (2000). Problem-based learning in real estate education. Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 3(1), 35–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/10835547.2000.12091568

- Ballard, C., & Johnson, M. (2005). Gender, expectations, and grades in introductory microeconomics at a US university. Feminist Economics, 11(1), 95–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354570042000332560

- Bandiera, O., Larcinese, V., & Rasul, I. (2015). Blissful ignorance? A natural experiment on the effect of feedback on students' performance. Labour Economics, 34, 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2015.02.002

- Bjork, R. A., Dunlosky, J., & Kornell, N. (2013). Self-regulated learning: Beliefs, techniques, and illusions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 417–444.

- Boud, D., & Falchikov, N. (1989). Quantitative studies of student self-assessment in higher education: A critical analysis of findings. Higher Education, 18(5), 529–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00138746

- Boud, D., Lawson, R., & Thompson, D. G. (2015). The calibration of student judgement through self-assessment: Disruptive effects of assessment patterns. Higher Education Research & Development, 34(1), 45–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2014.934328

- Burson, K. A., Larrick, R. P., & Klayman, J. (2006). Skilled or unskilled, but still unaware of it: How perceptions of difficulty drive miscalibration in relative comparisons. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.60

- Butler, J., Guntermann, K., & Wolverton, M. (1998). Integrating the real estate curriculum. Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 1(1), 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/10835547.1998.12091554

- Charles, S. L. (2016). Graduate real estate education: The ULI Hines student competition as a pedagogical tool. Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 19(2), 149–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/10835547.2016.12091763

- Clayson, D. E. (2005). Performance overconfidence: Metacognitive effects or misplaced student expectations? Journal of Marketing Education, 27(2), 122–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475304273525

- Dinsmore, D. L., & Parkinson, M. M. (2013). What are confidence judgments made of? Students' explanations for their confidence ratings and what that means for calibration. Learning and Instruction, 24, 4–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2012.06.001

- Dunlosky, J., & Rawson, K. A. (2012). Overconfidence produces underachievement: Inaccurate self evaluations undermine students’ learning and retention. Learning and Instruction, 22(4), 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2011.08.003

- Falchikov, N., & Boud, D. (1989). Student self-assessment in higher education: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 59(4), 395–430. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543059004395

- Grimes, P. W. (2002). The overconfident principles of economics student: An examination of a metacognitive skill. The Journal of Economic Education, 33(1), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220480209596121

- Händel, M., & Dresel, M. (2018). Confidence in performance judgment accuracy: The unskilled and unaware effect revisited. Metacognition and Learning, 13(3), 265–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-018-9185-6

- Hart Research Associates. (2015). Falling short? College learning and career success: Selected findings from online surveys of employers and college students conducted on behalf of the Association of American Colleges & Universities.

- Hoxley, M., Poon, J., & Fuchs, W. (2011). Real estate employability: Differing perceptions of graduates from undergraduate and postgraduate courses. Journal of European Real Estate Research, 4(3), 243–258. https://doi.org/10.1108/17539261111183434

- Karnilowicz, W. (2012). A comparison of self-assessment and tutor assessment of undergraduate psychology students. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 40(4), 591. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2012.40.4.591

- Kennedy, E. J., Lawton, L., & Plumlee, E. L. (2002). Blissful ignorance: The problem of unrecognized incompetence and academic performance. Journal of Marketing Education, 24(3), 243–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475302238047

- Kruger, J. (1999). Lake Wobegon be gone! The "below-average effect" and the egocentric nature of comparative ability judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(2), 221. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.2.221

- Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121.

- Merkle, C., & Weber, M. (2011). True overconfidence: The inability of rational information processing to account for apparent overconfidence. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 116(2), 262–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2011.07.004

- Metcalfe, J., & Finn, B. (2008). Evidence that judgments of learning are causally related to study choice. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 15(1), 174–179. https://doi.org/10.3758/pbr.15.1.174

- Miller, T. M., & Geraci, L. (2011). Unskilled but aware: Reinterpreting overconfidence in low-performing students. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 37(2), 502.

- Moreland, R., Miller, J., & Laucka, F. (1981). Academic achievement and self-evaluations of academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 73(3), 335. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.73.3.335

- Mourshed, M., Farrell, D., & Barton, D. (2012). Education to employment: Designing a system that works. McKinsey & Company.

- Nelson, T. O., & Leonesio, R. J. (1988). Allocation of self-paced study time and the "labor-in-vain effect" . Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 14(4), 676.

- Nowell, C., & Alston, R. M. (2007). I thought I got an A! Overconfidence across the economics curriculum. The Journal of Economic Education, 38(2), 131–142. https://doi.org/10.3200/JECE.38.2.131-142

- Palm, P., & Pauli, K. S. (2018). Bridging the gap in real estate education: Higher-order learning and industry incorporation. Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 21(1), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/10835547.2018.12091777

- Pieschl, S. (2009). Metacognitive calibration—An extended conceptualization and potential applications. Metacognition and Learning, 4(1), 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-008-9030-4

- Poon, J. (2012). Real estate graduates’ employability skills: The perspective of human resource managers of surveying firms. Property Management, 30(5), 416–434. https://doi.org/10.1108/02637471211273392

- Poon, J. (2014). Do real estate courses sufficiently develop graduates’ employability skills? Perspectives from multiple stakeholders. Education + Training, 56(6), 562–581. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-06-2013-0074

- Raftery, J. J., Cheung, A. A., Chiang, Y. H., Yeung, S. C., & Ma, F. M. (2001). The student experience of problem-based learning in real estate studies. Further case studies of improving teaching and learning from the action learning project, Hong Kong, Action Learning Project,

- Saenz, G. D., Geraci, L., Miller, T. M., & Tirso, R. (2017). Metacognition in the classroom: The association between students' exam predictions and their desired grades. Consciousness and Cognition, 51, 125–139.

- Serra, M. J., & DeMarree, K. G. (2016). Unskilled and unaware in the classroom: College students' desired grades predict their biased grade predictions. Memory & Cognition, 44(7), 1127–1137. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-016-0624-9

- Shanks, L. L., & Serra, M. J. (2014). Domain familiarity as a cue for judgments of learning. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 21(2), 445–453. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-013-0513-1

- Shepperd, J. A. (1993). Student derogation of the Scholastic Aptitude Test: Biases in perceptions and presentations of College Board scores. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 14(4), 455–473. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp1404_5

- Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. HeinOnline.

- Zell, E., & Krizan, Z. (2014). Do people have insight into their abilities? A metasynthesis. Perspectives on Psychological Science : a Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 9(2), 111–125.