ABSTRACT

Bilingual subject instruction, designed to facilitate the acquisition of the Norwegian language, is a support class aimed at immigrant students in primary and lower secondary Norwegian schools. This study delves into the beliefs of two Polish-Norwegian bilingual teachers regarding multilingualism in this instructional context and the factors influencing their decisions on incorporating students’ prior linguistic knowledge. Utilizing a narrative approach, the analysis of interviews reveals that both teachers perceive multilingualism as valuable for learning support and students’ social engagement. Individual variations emerge in how these teachers employ multilingual resources, reflecting a connection between their beliefs, experiences, and reported pedagogical decisions.

Introduction

The linguistic landscape in Norway is characterized by its richness and diversity, encompassing two official languages (Norwegian and Sámi), a plethora of dialects, and officially recognized national minority languages. Furthermore, it boasts a multitude of languages spoken by the population, including children and adolescents hailing from immigrant background. In addition to immigrants from neighboring countries like Denmark and Sweden, the list of migrants is prominently populated by residents originating from Poland, Lithuania, Eritrea, Somalia, Iraq, and Syria (Statistics Norway, Citation2023a). School students are often recipients of language instruction programmes at the primary and lower secondary school level that are designed to ease their way into Norwegian, the main language of education. Students’ rights in Norwegian schools are regulated by the Norwegian Education Act (Citation1998). Section 2-8 of the Act refers specifically to “language minorities” and states that students with a home language other than Norwegian or Sámi are entitled to adapted education in the Norwegian language until their proficiency has reached a level sufficient for them to attend mainstream schooling. In addition, these students also have the right to receive mother tongue tutoring, bilingual subject teaching, or both, if deemed necessary (Norwegian Education Act, Citation1998). The guidelines in the policy are formulated in a vague and ambivalent manner. Terms such as “sufficiently proficient” and “if necessary” are not explained further and are thus open to interpretation. Furthermore, there is no existing curriculum or framework specifically designed for bilingual subject instruction, in contrast to curricula addressing basic Norwegian instruction and mother tongue courses. An evaluation of Norwegian language support classes shows significant differences in how schools prioritize and facilitate the Act’s provisions for their students and uncovers the need for clearer guidelines for school boards in the face of the hazy requirements for content and organization in the current policy document (Rambøll Management, Citation2016). However, one might argue that the heterogenous group of immigrant students with limited skills in Norwegian benefits from the open formulation of this policy, which allows schools to offer language support classes that are tailored to their students’ situations. In theory, this would mean that teachers are free to draw on the individual linguistic resources the students bring into the classroom, ensuring that all students are given instruction that encompasses their varied multilingual experiences. In this article, we seek to shed light on what the main interpreters of the Education Act – the teachers – think about a multilingual pedagogy within bilingual subject instruction (henceforth BSI).

Recent findings show that language teachers in Norwegian schools are often positive about multilingualism, yet few report actively promoting multilingual practices, and they do not automatically conclude that multilingualism is an asset for their students (Calafato, Citation2020; Haukås, Citation2016; Lorenz et al., Citation2021). In addition, teachers are often hesitant to include other languages in their teaching if they feel that they lack knowledge in those languages or are accustomed to a linguistically and culturally homogenous classroom (De Angelis, Citation2011; Otwinowska, Citation2014). Several studies additionally report possessing advanced metalinguistic knowledge as a decisive factor for teachers to successfully implement a multilingual approach (Calafato, Citation2021; Otwinowska, Citation2017). Research has revealed the value of students’ existing language knowledge for learning additional languages (see Hirosh & Degani, Citation2018 for an extensive review), as they employ learning strategies gained through previous language learning experiences, drawing on existing language knowledge. However, the initiative to promote and apply a multilingual approach lies to a big extent with the teacher, where their experiences and beliefs play a decisive role (Calafato, Citation2019; Lasagabaster & Huguet, Citation2007). BSI, as the title of this support class implies, fundamentally involves the use of more than one language, yet the question remains what guides teachers in their pedagogical choices, and how they position themselves in the multilingual teaching context. The main findings we present in this paper discuss how the teachers interpret their role and how the existing policy, that is Section 2-8 of the Norwegian Education Act, influences their understanding of space for multilingual practices.

This study investigates the personal narratives of two teachers of Polish heritage engaged in Norwegian-Polish BSI who were interviewed to explore their beliefs concerning multilingualism, their strategies for integrating students’ home language into their teaching routines, and the practicality and desirability of harnessing the students’ entire linguistic repertoires in their pedagogical approaches. The following research questions were formed:

What characterizes the teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism in bilingual subject instruction? What influences the teachers’ pedagogical decisions concerning the integration of the students’ previous language knowledge in their reported teaching practice?

The objective is to gain detailed knowledge about the beliefs of bilingual teachers, who thus far have been underrepresented in recent publications. We also aim to contribute to the qualitative research on beliefs amongst second language teachers in the Nordic context, where most studies have been quantitative (Kulbrandstad et al., Citation2020). The terms multilingualism and multilingual are applied to describe the “dynamic and integrated knowledge and/or use of more than one language or variety” (Vikøy & Haukås, Citation2023, p. 2), while the term bilingual is used solely to refer to the support offer of bilingual subject teaching. The teachers participating in this study are identified as multilingual language teachers, because they employ “multiple languages in the diverse domains that comprise their life” (Calafato, Citation2022, p. 8). In the discussion below, we use the term home language to refer to students’ first language to avoid discrepancies between terms. However, we adhere to the terminology employed by the teachers in their accounts when presenting the research findings. To begin, we introduce key terminology pertaining to the field of multilingual education and teachers’ beliefs and provide an overview of studies focused on the teacher’s perspective in language teaching. We will then describe the narrative approach and the study’s participants. Subsequently, we present our findings, which are followed by a concluding discussion.

Multilingualism in education: Teachers’ beliefs on multilingual pedagogy

Exploring teachers’ beliefs about their approach to multilingual pedagogy requires a deeper understanding of how to identify and operationalize the concept of multilingualism. In education, native-like proficiency has been used as an implicit norm for second language learning, meaning that the language competence of multilingual students is compared with the competence of their monolingual peers and assessed by the same standards of achievement. Alternative approaches prefer to view the individual who knows more than one language as a competent language user rather than a deficient monolingual (Cook, Citation2012). The rejection of monolingual conceptualizations of language use and empowering linguistic minorities is referred to as the multilingual turn (May, Citation2014) and highlights the heterogenous nature of the resources involved in communication (Cenoz & Gorter, Citation2019). Multilingual education refers to the use of two or more languages in schools where multilingualism or multiliteracy is on the agenda, either as part of the official curriculum or in complementary classes (Cenoz & Gorter, Citation2015), an approach which can also be applied to the language support classes described in Section 2-8 of the Norwegian Education Act. Multilingual pedagogical approaches leverage insights from research on multilingualism. According to Haukås (Citation2016), it is necessary that language teachers are familiar with recent research to adopt a multilingual pedagogical approach. In the following, we introduce several key concepts.

The cognitive concept of linguistic multicompetence (Cook, Citation1991; Citation2016) recognizes that all languages within a person’s repertoire are related and therefore affect the whole mind, rather than a single language. Calafato (Citation2019) suggests that multicompetence implies that non-native speaker teachers (such as the bilingual teachers in this study) possess explicit knowledge of the target language (Norwegian). This enables them to engage students in deeper exploration of linguistic works through a comparative approach to cultural and linguistic insights, making them “model teacher candidates for the implementation of multilingual initiatives” (Calafato, Citation2019, p. 2). Delving further into the academic context, Cummins’ theory of common underlying proficiency (CUP) (Citation2021) emphasizes the interrelatedness of languages in a learner’s mind. This interconnectedness makes it possible to transfer skills, strategies, and knowledge across languages, making CUP an important concept for guiding teachers’ actions in utilizing the linguistic resources available in the teaching context and their understanding of how multilingualism influences their students. In terms of dynamic multilingual practices, the concept of translanguaging (García & Wei, Citation2014) refers to multilinguals’ use of all their available linguistic resources to create meaning in communication and to an approach to language pedagogy that affirms and leverages students’ diverse language practices in teaching and learning (Vogel & García, Citation2017). In the bilingual teaching context, teachers have the potential to engage in translingual practices, drawing upon their own linguistic resources as well as those of their students, to effectively negotiate meaning and impart subject knowledge. In addition to their pedagogical role, multilingual teaching practices aim to influence students’ perception that they can utilize their linguistic resources without limitation. Haukås (Citation2016) points to the teachers’ role in inspiring their learners to develop a multilingual identity. A multilingual pedagogy has the potential to strengthen the student’s multilingual identity and empower those with limited proficiency in the instructional language. Cummins (Citation2000, Citation2021) defines the term empowerment as “the collaborative creation of power” (Citation2021, p. 61) and explains that empowering classroom contexts can support students making their voices heard and respected, thereby expanding their opportunities for investment in future identities (Norton & Kramsch, Citation2013).

Studying teachers’ beliefs in multilingual education gives the researcher the possibility to understand the teachers’ conceptualization of a multilingual pedagogical approach. In the broadest terms, teachers’ beliefs can be described as different aspects of their thinking, attitudes, and experiences about a specific topic. The term has been defined in a multitude of ways and spans over different dimensions (e.g., implicit and explicit nature, stability over time or relation to knowledge) (Fives & Buehl, Citation2012). In the present study, teachers’ beliefs refer to their explicit (voiced) beliefs on language, language learning, and language teaching, and focus on the dynamic nature of beliefs as precursors to action, which serve as a filter for interpreting knowledge and guiding the teachers’ practices (Fives & Buehl, Citation2012). According to Burns et al. (Citation2015), the act of teaching combines classroom actions, interactions, routines, and behaviors that are accessible through observations, with private mental work-planning, evaluating, reacting, and deciding that can only be indirectly observed by researchers (p. 585). In line with Borg (Citation2011), a teacher’s beliefs cannot be true or false but must be seen as representations of his or her cognition about language learning and teaching shaped through previous experiences. Following Alisaari et al. (Citation2019), we presuppose that teachers’ beliefs include ideologies, policies, and perceptions about teaching and learning, which in turn have consequences for classroom activities and serves as a filter for teachers’ understanding of the world.

In terms of narrative research, there is an increasing focus on exploring language teachers’ classroom and school experiences through narrative forms of action and practitioner research (Barkhuizen, Citation2015). This allows for the exploration of the subjective aspects of second language teaching, as they are revealed through stories in which the storyteller articulates their lived experiences, beliefs, and emotions (Golden et al., Citation2021) and are consequently interpreted as active and fluid conceptions by the researcher (Barkhuizen, Citation2015). Several recent studies have investigated teacher beliefs and perceptions about multilingualism and/or translanguaging. This research has dealt with teachers in various settings, such as classes in the language of education (Iversen, Citation2019; Lindholm, Citation2020; Vikøy & Haukås, Citation2023), additional language education (Calafato, Citation2020, Citation2021; Haukås, Citation2016; Lorenz et al., Citation2021; Tishakov & Tsagari, Citation2022), and general teaching contexts (Lundberg, Citation2019). No studies have specifically addressed multilingualism in a bilingual research context in the Nordic region, a gap which this study aims to fill. The findings of existing studies show that teachers are generally positive toward multilingualism (Alisaari et al., Citation2019; Haukås, Citation2016), but that this belief is not necessarily reflected in their practices, as they acted in favor of the majority language (Burner & Carlsen, Citation2019; Haukås, Citation2016). The teachers’ own background and experience with multilingualism had a generally positive impact on their attitudes toward learner languages and employing them in their practices (Alisaari et al., Citation2019; Vikøy & Haukås, Citation2023). Nevertheless, many studies show that teachers adopt a cautious outlook on multilingual practices, a finding that can be directly linked to the teachers’ limited knowledge about the approach (Tishakov & Tsagari, Citation2022). This article contributes to the field of teacher beliefs about multilingualism in language support classes through a narrative approach, offering insights into the beliefs of teachers specifically involved in bilingual subject instruction and how these educators interpret the scope for their actions within the existing policy framework.

Methodology

The data in this study originate from a larger doctoral study on multilingual pedagogy in bilingual subject instruction in Norwegian schools. The study draws on semi-structured interviews as the data collection method. Two teachers were invited to participate in the study based on convenience, as the first author, being of Polish heritage, sought to recruit bilingual teachers with a similar background. The recruitment criteria were the teachers’ involvement in Norwegian-Polish subject instruction in the Norwegian lower secondary school sector, in accordance with Section 2-8 of the Norwegian Education Act. The teachers were found and recruited through direct contact with the municipality which the institutions that employed the teacher belonged to. There is no official registry of the total count of bilingual teachers in the country. However, as of 2023, there were 8309 students enrolled in BSI classes nationwide (Statistics Norway, Citation2023b). The two teachers who accepted the invitation were the sole Polish-Norwegian bilingual teachers in their respective municipality. The interviews constitute one component of the data set for the overarching doctoral study, which includes observational data and audio recordings spanning a period of time.

Participants and data collection

The teachers are Polish bilingual subject teachers (Norwegian: tospråklige faglærere) who work for different schools in two municipalities in Norway. Their primary task is to convey instruction in one or more subjects in both Norwegian and the student’s home language or another language mastered by the student (Nasjonalt senter for flerkulturell opplæring, Citation2021). They primarily work with students with Polish as their home language but have also been involved in different forms of adapted instruction in Norwegian during their careers. The teachers’ main responsibilities revolve around conducting one-on-one tutoring sessions with students that have been deemed eligible for BSI classes by the municipality, in accordance with Section 2-8 of the Norwegian Education Act (Citation1998). This number of students fluctuates from year to year, necessitating travel between schools to accommodate their students at their respective institutions. While the duration and frequency of the classes depend on individual circumstances, the typical tutoring commitment per student usually involves 1–2 sessions per week, each lasting 1–2 hours. There are also differences in the students’ ages and backgrounds, affecting their language repertoires and forcing the teachers to be flexible. Both teachers interviewed in this study arrived in Norway following Poland’s EU membership in 2004. They acquired Norwegian language proficiency through formal courses and immersion in everyday life. Both teachers completed teacher education courses but lacked practical or theoretical experience in multilingual education prior to becoming involved in BSI. They did, however, have experience as multilingual users themselves (see ). Additionally, they did not receive specific instruction or courses from the municipality before commencing their roles as bilingual teachers. The following participant descriptions are based on how the teachers recounted their work experiences in the interviews. Both participant names are pseudonyms.

Table 1. Teacher profiles.

Ewa, a certified teacher, relocated to Norway from Poland in the mid-2000s. She is an experienced math teacher, but her introduction to bilingual instruction occurred in Norway, when she answered the demand for Polish-Norwegian teachers in primary and lower secondary schools within several municipalities in her local area. Ewa says teaching is her vocation and that she thrives in the job, even though it was, in her words, a struggle in the first two years due to her being relatively new to the Norwegian language. Ewa plans on continuing bilingual teaching and widening the target group to students other linguistic and cultural backgrounds.

Piotr holds a pedagogical degree from Poland but describes his start in bilingual education as a coincidence. While pursuing a different career, he was asked by an acquaintance employed in the school system to take on a part-time position as a bilingual teacher at a local school, marking his initial practical pedagogical experience. The post grew over time, and for the last eight years, Piotr has been active as a full-time bilingual teacher in two municipalities. Piotr plans on continuing his teaching career until retirement, as it is less physically strenuous than his previous job.

presents the teachers’ reported work experience, additional information about their backgrounds, and the duration of the interviews.

The interview questions were classified into five main topics: (1) biographical information about the teachers, (2) the premises of bilingual subject instruction and the teachers’ practices, (3) language choices in the classroom, (4) multilingualism and translanguaging, and (5) cooperation with students. Since neither of the interviewed teachers possessed formal qualifications in multilingual education, the interviewer avoided using theoretical terminology and instead used everyday language, such as “mixing languages” in place of “translanguaging.” The choice of the language for interaction holds significant ethical implications, affecting both the researcher-participant interaction and the outcomes of the study (Calafato, Citation2022). As shown in , the teachers themselves are multilingual individuals, however the first author conducted the interviews in Polish, her own and the teachers’ dominant language, to facilitate the collection of personal narratives (see Golden et al., Citation2021). Translingual practices occurred when referring to terminology from the Norwegian school domain, by both participants and researcher. The practice led to an unconstricted conversation with emphasis on the content. Both conversations were recorded through a dictaphone app which sent the recordings directly to an encrypted data collection site. All extracts from the interviews presented in this article have been translated into English by the researcher who collected the data, proficient in both Polish and English. This was done to minimize the risk of misinterpretation and inaccuracy, thereby preserving the validity of the data (Schembri & Jahić Jašić, Citation2022). Instances where translation could have led to ambiguities were discussed with the second author.

Analysis – A narrative approach

Each interview was recorded and transcribed with participant consent. In the analysis, we based ourselves on narratives as tools of interpretation (De Fina et al., Citation2006) and on the concept of narrative knowledging (Barkhuizen, Citation2015). It can be described as a process of “meaning-making, learning, and knowledge construction” (p. 97) which takes place in a narrative research project and encompasses the process of making sense of an experience through narrating, analyzing the narrative and reporting on it through research. This definition suggests the involvement of various participants in the research process, such as the narrator and researcher, and places emphasis on the collaborative essence of the narrative research. The teachers’ narratives in this study unfolded in response to the researcher’s interview questions, further underscoring the collaborative aspect of the research. Our primary focus was however on the stories shared by the teachers during the interviews, where they recounted real-life situations from their teaching practice and explained their interpretations of the scenarios, shaping the overarching narrative. Narratives are particularly effective for “displaying human existence as situated action” (Polkinghorne, Citation1995, p. 5) emphasizing the aim not to communicate one objective truth, but instead to convey an individual’s perspective and how they position themselves within the worlds they describe (Golden et al., Citation2021). In addition to functioning as an analytical approach, the teachers’ narratives play a crucial role in negotiating their understanding of their position as bilingual educators and articulating their beliefs regarding their practice, comprising convictions, concerns, and aspirations. The analysis of the teachers’ narratives followed a thematic approach, inspired by Polkinghorne’s (1995) analysis of narratives and seeked to identify “common themes or conceptual manifestations among the stories collected as data” (p. 13). We analyzed interview transcriptions to uncover recurring themes by examining the teachers’ experiences and reflections on language within teaching situations, both in theoretical musings and reported practices. The themes that emerged through this approach were subsequently organized into three broader categories for the purposes of deeper interpretation and analysis (see Barkhuizen, Citation2015) and further analyzed using the model for connections between beliefs, ideologies, and reported actions (Alisaari et al., Citation2019).

Findings

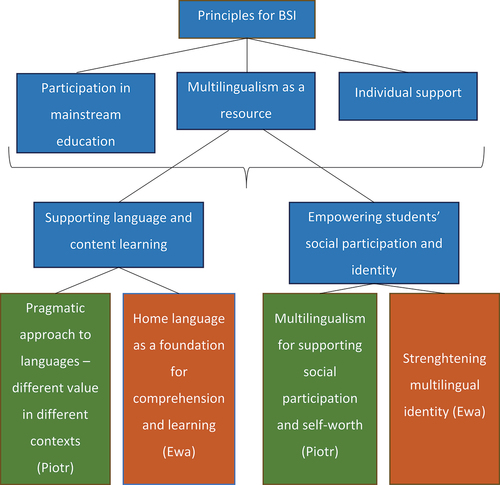

The analysis is presented in two stages: in the first stage (section 4.1) we shortly present the principles for the use of multilingual resources in BSI, as described by the two teachers. In the second stage (sections 4.2 and 4.3) we present the teachers’ narratives regarding the use of the students’ linguistic resources across two overarching categories: (1) multilingualism as a support in language and content learning, and (2) multilingualism as an empowerment tool for building social bonds and strengthening identity. The summarized findings are presented in .

Principles for multilingual practices in BSI

Through the interviews, three key elements for BSI emerged as foundational principles for the teachers’ actions. Firstly, both Ewa and Piotr voiced a belief that multilingualism is an asset for students. Their narratives reflected a positive stance toward multilingual individuals, viewing a person who knows two or more languages as multilingual by default. Despite lacking formal training or specific guidance in multilingual pedagogy, both Ewa and Piotr’s beliefs and reported practices resonate with many of the concepts outlined in the wake of the multilingual turn (May, Citation2014), which will be furthered explored in the subsequent sections.

The second belief that shaped the teachers’ approach and laid a foundation for their classes is the primary objective of BSI: to support students of Polish background in achieving proficiency Norwegian that enables them to transition to mainstream education as quickly as possible. Despite being initially hired based on their knowledge of Polish, neither Piotr nor Ewa identify as mother tongue teachers, emphasizing the bilingual nature of the classes they are responsible for. As previously mentioned, mother tongue teaching is another form of adapted instruction in Norwegian under Section 2-8 of the Education Act. Piotr says that he never really was a “typical mother tongue teacher” since all his students have required urgent help in understanding Norwegian and adapting to the Norwegian school environment. Ewa has the same view on the overall objective of the classes; however, she emphasizes the role of the home language in the learning process, stating, “I want them [the students] to learn Norwegian through Polish.” This nuance highlights the first difference in their language ideologies and perceptions, a divergence further explored in subsequent findings. Additionally, both teachers stress the importance of close cooperation with colleagues responsible for mainstream education, underscoring their orientation toward policy alignment. Piotr takes pride in his effective teamwork with other teachers, considering it of vital importance for preparing his students for mainstream instruction. In his classes, the primary focus is on vocabulary acquisition and discussion around relevant concepts with older students, and on enhancing reading comprehension with the younger ones. Ewa also tailors her classes to align with the students’ regular schedules, taking into consideration announced tests and other subject-related tasks and to prepare the material accordingly. She places strong emphasis on collaboration with fellow teachers, even though she finds it challenging, especially due to her involvement in multiple schools. Vocabulary learning is a consistent feature in her classes, but many other aspects depend on individual student needs.

This leads us to the third cornerstone for BSI classes: individualized support. Both teachers perceive BSI as a flexible program tailored to the individual needs and language proficiency of each student, rather than adhering to a one-size-fits-all approach. This finding underscores what perception about teaching and learning within BSI shapes the teachers’ choice of classroom activities and language use. Through their narratives, Ewa and Piotr highlight the diverse backgrounds and language abilities of their students. The key principles outlined for BSI underscore the need for dynamic practices in response to changing circumstances, placing significant demands on the teachers who lack a specific curriculum to follow. In the following section, we delve deeper into the teachers’ narratives, unpacking their beliefs about implementing multilingualism as an instructional tool within the learning context.

Multilingualism as a learning support

While both teachers share the same perspective regarding the primary goal of BSI, which is students learning Norwegian, their beliefs about the role of Polish as a support in learning diverge. Piotr’s main objective is to support his students in excelling in the mainstream classroom by utilizing their home language and “making use of” their multilingualism. Piotr’s choice of language in class is influenced by the individual student. Polish is employed when the student faces challenges in understanding Norwegian and needs assistance in content learning. However, if a student is proficient in Norwegian, the classes mainly occur in that language. Piotr explains his practice in the following excerpt:

If I have, for instance, a sixth grader who has been to Norwegian school since first grade, then he is good enough, so that many things - we speak in Norwegian, we read in Norwegian. If we perchance stumble upon something difficult, then I explain it in Polish, or translate one word. He is raised here, so sometimes it happens that translating doesn’t help him, right, to Polish. Because in turn his Polish vocabulary is very poor, because it’s very subject-based, so sometimes I end up explaining even more. But with younger children, or those who are new, then obviously Polish has to be the main language.

In describing his approach, Piotr notes that the students’ home language may not always serve as an aid, especially when the student has spent their entire academic life in a Norwegian school. In different parts of his narrative, Piotr characterizes some of his students as “strong in Polish,” further contributing to the realization that despite being their home language, Polish may not necessarily be their dominant or most readily accessible language. This reflection highlights the teacher’s practical stance on using multilingualism as a support and underscores that the primary objective in Piotr’s BSI classes is to facilitate the student’s integration into the mainstream classroom.

Ewa, on the other hand, speaks mainly Polish in class, considering the home language a foundation for all learning. Regardless of the student’s proficiency in Norwegian, they are required to comprehend the topic in Polish as well. Ewa characterizes her approach as not solely centered on translation and providing vocabulary related to the topic but also on fostering a comprehension of complex subjects. She gives an example in the following excerpt:

So if she [the student] had the topic of law and order, not an easy topic, judiciary matters and those relating to the accused, all that vocabulary, she can’t even explain this accurately in Polish, let alone in a foreign language, so here we first discussed the topic in Polish because it’s a bit stupid to read only in Norwegian right away and discuss something she has no idea about.

Through this story, Ewa portrays Polish as more than merely a support system for understanding; she sees it as a fundamental cornerstone for knowledge. In her opinion, students should grasp the topic in Polish before delving into it in the second language, emphasizing however that this is often a parallel process. Ewa’s reasoning is consistent with the concept of multicompetence (Cook, Citation1991, Citation2016) as she recognizes the interrelatedness of various languages within a user’s repertoire (Cummins, Citation2021). Her belief underscores her awareness that the student’s languages influence each other. She leverages the transferability of skills between the languages of multilingual speakers in her classes, benefiting students’ understanding of second language and subject content. Despite her emphasis on the significance of preserving the home language, ultimately the goal of Ewa’s BSI classes is to enable students to function effectively in the mainstream classroom. She asserts that “in a Norwegian school, students should speak and write in Norwegian.”

While rooted in different approaches to the home language, BSI classes under the guidance of Ewa and Piotr can be described as fundamentally multilingual. Neither teacher deems it feasible, nor desirable, to strictly enforce a one-language-only policy during their teaching. In fact, both teachers find that the practice of utilizing the total linguistic repertoire can be beneficial. Piotr voices his perceptions about teaching and learning through multilingual resources in the classroom, sharing stories about colleagues intentionally mixing Norwegian and English to teach English as a foreign language. He concludes that his own choice of classroom activities is effective, pointing out the proficiency of Norwegian students in English – a skill he considers valuable in the contemporary world. His contemplation extends to Polish, as illustrated in the excerpt below:

But can Polish be as important here? Hmm, probably not in speech, but surely in understanding. The child probably gets a wider picture of the world if they struggle with finding the Norwegian word but know the Polish one, so they surely have a broader understanding of the world, for sure.

In this reflection Piotr acknowledges the mutual effects that languages have on each other within a person’s repertoire. By recognizing the connection between Norwegian and Polish in shaping the students’ worldview, he demonstrates beliefs aligned with the principles of linguistic multicompetence (Cook, Citation2016) and CUP-theory (Cummins, Citation2021), despite not explicitly referencing any theoretical concept. Nevertheless, he questions the effectiveness of using Polish in the mainstream classroom, reinforcing his rather pragmatic stance on the societal value of languages. Despite his doubts, in other parts of his narrative, Piotr recognizes the naturalness of language mixing in contexts where all participants are proficient in the language. He explicitly identifies BSI classes or the interview with the researcher as natural settings for translanguaging to support learning and achieve effective communication.

Ewa is aware that she actively alternates between Polish and Norwegian during classes, emphasizing the inseparability of the two languages. She characterizes this practice as inherent in the bilingual teaching setting, yet she sets a boundary by refraining from mixing languages at the sentence level. Ewa favors responses to questions posed in Polish to be answered in Polish, and the same principle applies to questions in Norwegian. She provides further elaboration on this topic in the following excerpt:

But for instance, when it comes to understanding the topic, if a student mixes languages because they forgot, or they didn’t learn the word, then if they say it in the other language then at least I know they understand it, right? So, it shows understanding. However, then I am also aware that we have to put some more effort into learning the word in Norwegian, or the other way around.

In her reflection, Ewa once again underscores the interconnected nature of the student’s repertoire, emphasizing that what she hears is an expression of fundamental understanding. Ewa supports the strategy of mediating learning by employing both Polish and Norwegian to ensure students’ comprehension of the topic, endorsing translanguaging as a pedagogical approach. Her belief is driven by the goal to prepare students for classes in Norwegian while maintaining a solid Polish base. In contrast, Piotr’s beliefs about multilingual pedagogy lean toward a practical response, addressing immediate needs without ideologically focusing on honing the home language. Nevertheless, both teachers view multilingualism as a resource beyond its practical appliance in language learning. They extend their narrative to discuss the broader meanings of multilingualism in social relations and its significance in shaping identity.

Multilingualism as an empowerment tool – Building social bonds and strengthening identity

Although both Piotr and Ewa underscore the importance of BSI in assisting the students to navigate the mainstream classroom, they view it as part of their duty to help the student “find themselves” and “existFootnote1” within the new school environment. The social aspect is visible in both teachers’ narratives as they not only describe their actions within language and subject tutoring but also emphasize the importance of the students’ social integration and feeling of empowerment in the mainstream classroom. Piotr explains:

The social part is as important, because the child, thanks to my help, often manages to find themselves better at school, understands what is going on. I also help solve small conflicts, through explanation and conversation. (…) There was one shy boy, one of my first students, so in the beginning of the class we decided to set up an interview. We wrote 5 simple questions and invited the other [Norwegian] students one by one, he asked them questions and tried to understand what they were saying, and this was the first step. So, I think the social bit is also important.

Through this story, Piotr elaborates on how he, as a bilingual teacher, deliberately chooses to use Polish to aid students in understanding and subsequently navigating new social settings. He interprets his role as a mediator in student relations, considering it an aspect of his responsibilities as a bilingual teacher. Implicitly, he recognizes his capacity to empower students who are new at school and may not yet be proficient the instructional language. Piotr acknowledges the advantage of using Polish to clarify situations where a “lack of understanding leads to conflict,” incidents that arose due to misinterpretations by newly arrived Polish students. Yet, concerning the students’ use of Polish for further strengthening social bonds, Piotr characterizes it as more of a novelty – employed to teach peers simple (and often inelegant) words rather than serving as a valuable resource for creating social bonds. He suggests that multilingualism might have a more practical social aspect if it involves languages such as German or English, as it provides “extra practice for Norwegian students in their free time.” Piotr’s ideological approach can be characterized as community-oriented, as he considers the practical use of languages important for the common good and advantages, further contributing to his pragmatic perspective on multilingualism in school. A recurring theme in his stories is his perspective that Polish is considered less useful compared to languages like English, implying an instrumental hierarchy of languages. Nonetheless, he also finds examples from his practice illustrating how leveraging cultural knowledge and building on the student’s experiences can empower the student, as depicted in the excerpt below:

It doesn’t happen so often with Polish, but I once had a student who needed a lot of help, so during Christmas we prepared a presentation about Polish traditions for the rest of the class. The fact that he could stand in front of the whole class and talk about Polish traditions in his weak Norwegian, but still Norwegian, made him grow several inches. So, to boost his self-worth, and I have to say that everybody was listening with their eyes wide open.

In this reflection, Piotr evaluates his own practices as a bilingual teacher, acknowledging their efficacy in making the student’s voice heard and respected (Cummins, Citation2021). Piotr envisions a teacher who, by recognizing and explicitly building on these resources, not only enhances the child’s self-worth but also elevates their “value” within the group. He concludes his discussion by emphasizing significant individual differences in approaches between schools and notes, “If it was in reality like it is on paper, that it [multilingualism] is a value in itself, then it would be perfect, but it’s not always the case.”

Ewa recognizes the practical significance of knowing and using languages present in the curriculum, but, contrary to Piotr’s belief, broadens this perspective to include other minority languages in her discussion of the social value of multilingualism, as illustrated in the following excerpt:

I think that it [multilingualism] is an advantage for the class or other people. Students can make themselves seen during English classes or talk to other students. They use different languages during breaks; sometimes you hear Norwegian, sometimes even a few Polish words. (…) I also hear English. But really, the students like to learn new languages, and it doesn’t only concern words that are vulgar, if I can put it that way.

Beyond the overall positive attitude toward other languages amongst students, Ewa underscores the significance of asserting one’s presence in the classroom. This, she describes, is essential in her teaching – to ensure the student’s active presence within the mainstream classroom. Her approach can be considered individual-oriented, with a primary focus on strengthening the student’s multilingual identity. Ewa often emphasizes that fostering the students’ multilingual resources extends beyond academic support and social bond building. She chooses to uphold Polish cultural roots and identity elements, which is present in her actions within BSI classes aimed at affirming and enhancing students’ feeling of belonging. Ewa explains:

It’s really important with a national identity and a cultural base. (…) If we don’t hone it then later the child reaches a point where they are scared to speak in their mother tongue in the hallway. (…) Especially in primary school one must put emphasis on it, because after a while the student thinks oh, everybody speaks Norwegian here, but I speak in this weird language. (…) I always try to make my student feel appreciated that he knows another language, not only English and Norwegian.

By quoting and amplifying the student’s voice, Ewa directs attention to prevailing ideologies and challenges the monolingual discourse that perpetuates feelings of shame and fear of exclusion associated with knowing and using a minoritized language. She points to her role in empowering the student by affirming the linguistic resources they possess and further elaborates on the teachers’ significance in actively promoting the students’ home languages to “forge a bond with the language and cultivate a sense of identity as a full-fledged member of society,” opening opportunities for investing in future identities (Norton & Kramsch, Citation2013). Ewa expresses a belief that the same practice should be implemented in the mainstream classroom, ensuring the student’s presence, and conveying a message that nobody denies their resources and heritage. Simultaneously, Ewa is aware that the students must know Norwegian to be able to fully participate in the mainstream classroom.

Despite a different focus on the empowering potential of multilingual resources, Ewa and Piotr share the belief that all teachers have the potential to play a crucial role in shaping a narrative around the student’s linguistic and cultural resources as valuable assets. The study’s findings are outlined in , where blue indicates shared beliefs between Ewa and Piotr, and green and orange emphasize different beliefs between the two.

Concluding discussion

In this article we have examined what characterizes two bilingual teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism in bilingual subject instruction, along with factors influencing their pedagogical decisions regarding the incorporation of the students’ prior language knowledge into their teaching practices. Through an analysis of the teachers’ narratives on multilingual pedagogy in BSI, we offer insight into how Ewa and Piotr position themselves in their roles as teachers and implement multilingualism as a supportive tool for learning, as well as its role in empowering their students. The analysis reveals that, despite expressing positive beliefs about the general value of multilingualism, the teachers operate from different ideologies on how and when multilingual resources should be drawn on. Piotr embodies a pragmatic and slightly instrumental approach, prioritizing languages that provide students with distinct academic and social advantages due to their status in school (such as Norwegian, English, and German) over the students’ home language, Polish. Nonetheless, Piotr acknowledges Polish as a resource in facilitating the transition into mainstream education, particularly for newly arrived students.

Perhaps resulting from her deeply ingrained teacher identity and extensive experience, which extends back to her home country, Ewa actively nurtures Polish in her practice, taking on an extra role of a home language educator. This is driven by a belief that Polish carries significant cultural value and serves as a foundational element for knowledge and understanding, irrespective of the students’ proficiency level in Norwegian. Despite the important role attributed to her and her students’ home language, Ewa additionally expresses a belief that could be seen as contributing to a monolingual bias in education (Cook, Citation2012) when she emphasizes the importance of students’ knowledge of Norwegian in Norwegian schools. However, this viewpoint should be discussed in the context of her role as a bilingual teacher within BSI. Both Ewa and Piotr emphasize that the primary objective of these classes is to prepare students for mainstream education, where Norwegian is predominant, a notion supported by Section 2-8 of the Education Act. This priority points to the teacher’s policy orientations as part of their beliefs, as well as presents BSI as a different “realm” adjacent to the mainstream context, where teachers who perceive multilingualism as an asset can engage in creative multilingual solutions. Concurrently, both teachers primarily prioritize the language aspect of the classes, with subject preparation somewhat assigned to a secondary role, indicating that Piotr and Ewa predominantly perceive themselves as language instructors.

Both Ewa and Piotr advocate for multilingual pedagogy in their distinctive ways, recognizing the importance of affirming their students’ complex linguistic resources and voicing the significance of prior languages for the development of other languages and subject knowledge, through a line of reasoning that can be connected to the theory of multicompetence (Cook, Citation1991, Citation2016) and Cummins’ CUP-theory (Citation2021). The bilingual teachers highlight that their classes serve as spaces where students can use their linguistic resources for better understanding and enhanced progress. This perspective aligns with the concept of translanguaging (García & Wei, Citation2014), emphasizing the significance of multiple linguistic resources for meaning making and communication. The beliefs related to these concepts of multilingual pedagogy were implicitly referenced by the teachers, suggesting that non-native speaker teachers, equipped with multicompetence and explicit knowledge of the target language (Calafato, Citation2019) possess an inherent capacity to implement multilingual pedagogy. The narratives presented in this study underscore the significant role of the educators in operationalizing and conveying attitudes toward multilingualism. Ewa and Piotr, through their stories, emerge as role models for their students – a bridge between home language and culture and the reality of mainstream school. Although this study does not explicitly address aspects of the teachers’ identity, the beliefs and reported practices suggest that they embody a multilingual identity. By reinforcing the students’ home language to aid in subject comprehension and assist them in navigating the social dynamics of the school, the teachers each contribute, in their unique way, to the notion that being multilingual is a source of pride. The cultivation of a multilingual identity among students starts with the teachers (Haukås, Citation2016).

The initial hypothesis in this study addressed the potential advantages of openly formulated guidelines of Section 2-8 of the Education Act for a heterogenous group of students with different needs and challenges. A key element emphasized in the outline of the principles for BSI under the guidance of Piotr and Ewa is their adaptability and commitment to tailoring their approach to each individual student. Freed from rigid guidelines, the teachers have the liberty to choose their pedagogical approach. However, it is important to recognize that other teachers involved in Norwegian support classes may not interpret the openly policy with the same positive stance on multilingualism, while Piotr and Ewa’s inherently positive beliefs on multilingualism may have influenced their participation in this study. Recent studies in the Norwegian context indicate that positive beliefs about multilingualism do not necessarily translate into multilingual practices (Calafato, Citation2020; Haukås, 206; Lorenz et al., Citation2021). This suggests that there is a need for clearer policy guidelines explicitly advocating for multilingual education to ensure that the value of prior linguistic and cultural knowledge is not overlooked. Moreover, establishing a clear framework plan or creating a curriculum specifically outlining the objectives for the class could strengthen the advantage of including multilingual resources in BSI.

The findings of this study cannot be generalized to reflect the beliefs of a larger population of bilingual teachers as it is based on perspectives of only two individuals. Furthermore, the study examines only the teachers’ reported practices through their narrative accounts, lacking additional data sources to broaden the understanding of how their pedagogical strategies manifest in practice. To enhance the reliability of the findings, further research involving a larger sample of BSI teachers, preferably from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds, is recommended. Further research into successful teacher practices in increasingly multilingual teaching contexts is also needed to comprehend the costs and benefits associated with the ongoing multilingual turn. Recent studies indicate challenges in adequately preparing future teachers for cultural and linguistic diversity in Norwegian classrooms (Iversen, Citation2019, Citation2020; Randen et al., Citation2015), whilst experienced teachers tend to maintain monolingual practices, despite positive beliefs about multilingualism gained in professional development workshops (Lorenz et al., Citation2021). Further exploration of the intricate relationship between teachers’ beliefs and corresponding practices would offer a deeper understanding of this dynamic.

This study addresses a gap in Nordic research by examining multilingual pedagogy in the context of bilingual subject instruction. The findings contribute to our understanding of how teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism influence their pedagogical decisions, considering their expressed ideologies, policy orientations and perceptions of teaching and learning (Alisaari et al., Citation2019). The implications of this study extend to teacher educators, educational institutions, and policy makers. The findings highlight individual differences between bilingual teachers involved in classes guided by an openly articulated policy document, without the necessity for formal multilingual education. As previously mentioned, a more precise formulation of the framework for BSI could prevent the neglect of multilingual resources. Regarding teachers’ professional development, bilingual teachers would benefit from a deeper understanding of the connection between teaching language and content, as well as the inherent advantages of utilizing students’ full linguistic repertoire in preparation for mainstream education. Extending beyond the immediate context of language support classes, teacher education programs and institutions should prioritize formal training for both pre-service and in-service educators in teaching within multilingual contexts. Multilingualism is present in nearly all schools in the Norwegian (and other) contexts in the 21st century, rendering even basic knowledge of multilingual research concepts indispensable for all educators.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Agnieszka Moraczewska

Agnieszka Moraczewska is a PhD candidate at Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences. Her research interests include second language learning and teaching and multilingual education. Moraczewska is currently working on her doctoral study which concerns multilingualism as a multi-competence in bilingual subject instruction in the Norwegian school sector. E-mail: [email protected]

Gunhild Tveit Randen

Gunhild Tveit Randen is Associate Professor of Norwegian language at Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences, where she teaches and conducts research in language and literacy. Her research interests include metalinguistic awareness, bilingual literacy, and language assessment. E-mail: [email protected]

Notes

1. Polish: zaistnieć, to mark the start of existing as a subject in the classroom context.

References

- Alisaari, J., Heikkola, L. M., Commins, N., & Acquah, E. O. (2019). Monolingual ideologies confronting multilingual realities: Finnish teachers’ beliefs about linguistic diversity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 80, 48–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.01.003

- Barkhuizen, G. (2015). Narrative knowledging in second language teaching and learning contexts. In The handbook of narrative analysis (pp. 97–115). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118458204.ch5

- Borg, S. (2011). The impact of in-service teacher education on language teachers’ beliefs. System, an International Journal of Educational Technology and Applied Linguistics, 39(3), 370–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2011.07.009

- Burner, T., & Carlsen, C. (2019). Teacher qualifications, perceptions and practices concerning multilingualism at a school for newly arrived students in Norway. International Journal of Multilingualism, 19(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2019.1631317

- Burns, A., Freeman, D., & Edwards, E. (2015). Theorizing and studying the language‐teaching mind: Mapping research on language teacher cognition. The Modern Language Journal, 99(3), 585–601. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12245

- Calafato, R. (2019). The non-native speaker teacher as proficient multilingual: A critical review of research from 2009–2018. Lingua, 227, 227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2019.06.001

- Calafato, R. (2020). Language teacher multilingualism in Norway and Russia: Identity and beliefs. European Journal of Education, 55(4), 602–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12418

- Calafato, R. (2021). “I feel like it’s giving me a lot as a language teacher to be a learner myself”: Factors affecting the implementation of a multilingual pedagogy as reported by teachers of diverse languages. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 11(4), 579–606. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2021.11.4.5

- Calafato, R. (2022). Fidelity to participants when researching multilingual language teachers: A systematic review. Review of Education, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3344

- Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2015). Towards a holistic approach in the study of multilingual education. In J. Cenoz & D. Gorter (Eds.), Multilingual education: Between language learning and translanguaging (pp. 1–15). Cambridge University Press.

- Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2019). Multilingualism, translanguaging, and minority languages in SLA. The Modern Language Journal, 103(S1), 130–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12529

- Cook, V. (1991). The poverty-of-the-stimulus argument and multicompetence. Second Language Research, 7(2), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/026765839100700203

- Cook, V. (2012). Multi-competence and the native speaker. In C. A. Chappelle (Ed.), The encyclopedia of applied linguistics. (pp. 764–769). Lowa State University Digital Repositor.

- Cook, V. (2016). Premises of multi-competence. In V. Cook & L. Wei (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of linguistic multi-competence (pp. 1–25). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107425965.00

- Cummins, J. (2000). Language, power and pedagogy: Bilingual children in the crossfire. Multilingual Matters.

- Cummins, J. (2021). Rethinking the education of multilingual learners: A critical analysis of theoretical concepts. Multilingual Matters.

- De Angelis, G. (2011). Teachers’ beliefs about the role of prior language knowledge in learning and how these influence teaching practices. International Journal of Multilingualism, 8(3), 216–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2011.560669

- De Fina, A., Schiffrin, D., & Bamberg, M. (Eds.). (2006). Discourse and identity. Cambridge University Press.

- Fives, H., & Buehl, M. M. (2012). Spring cleaning for the “messy” construct of teachers’ beliefs: What are they? Which have been examined? What can they tell us? In K. R. Harris, S. Graham, & T. Urdan (Eds.), APA educational psychology handbook. Vol 2. Individual differences and cultural and Contextual Factors AmericanPsychologicalAssociation. (pp. 471–499). https://doi.org/10.1037/13274-019

- García, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Golden, A., Steien, G. B., & Tonne, I. (2021). Narrativ metode i andrespråksforskning [Narrative method in second language research]. NOA – norsk som andrespråk, 37(1–2), 133–155. https://hdl.handle.net/11250/2827461

- Haukås, Å. (2016). Teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism and a multilingual pedagogical approach. International Journal of Multilingualism, 13(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2015.1041960

- Hirosh, Z., & Degani, T. (2018). Direct and indirect effects of multilingualism on novel language learning: An integrative review. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 25(3), 892–916. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-017-1315-7

- Iversen, J. Y. (2019). Negotiating language ideologies: Pre-service teachers’ perspectives on multilingual practices in mainstream education. International Journal of Multilingualism, 18(3), 421–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2019.1612903

- Iversen, J. Y. (2020). Pre-service teachers’ translanguaging during field placement in multilingual, mainstream classrooms in Norway. Language and Education, 34(1), 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2019.1682599

- Kulbrandstad, L. I., Egeland, B. L., Nordanger, M., & Olin-Scheller, C. (2020). Forskning på andrespråkslæreres oppfatninger [Research on second language teachers’ beliefs]. NOA – norsk som andrespråk, 16(2), 5–20. http://ojs.novus.no/index.php/NOA/article/view/1885

- Lasagabaster, D., & Huguet, A. (2007). Multilingualism in European Bilingual Contexts: Language use and attitudes. Multilingual Matters.

- Lindholm, A. (2020). Svensklärares uppfattningar om flerspråkighet: en intervjustudie [Swedish teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism: An interview study]. NOA – norsk som andrespråk, 2(18), 83–100. http://ojs.novus.no/index.php/NOA/article/view/1889/1864

- Lorenz, E., Krulatz, A., & Torgersen, E. N. (2021). Embracing linguistic and cultural diversity in multilingual EAL classrooms: The impact of professional development on teacher beliefs and practice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 105, 103428. Article 103428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103428

- Lundberg, A. (2019). Teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism: Findings from Q method research. Current Issues in Language Planning, 20(3), 266–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2018.1495373

- May, S. (2014). Disciplinary divides, knowledge construction and the multilingual turn. In S. May (Ed.), The multilingual turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL and bilingual education (pp. 7–31). Routledge.

- Nasjonalt senter for flerkulturell opplæring. (2021). Særskilt språkopplæring. [Adapted Language Instruction]. https://nafo.oslomet.no/grunnskole/saerskilt-sprakopplaering/

- Norton, B., & Kramsch, C. (2013). Identity and language learning: Extending the conversation (2nd ed.). Multilingual Matters.

- Norwegian Education Act. (1998). Opplæringslova. Lov om grunnskolen og den videregåande opplæringa [Education law. Law about primary school and upper secondary education]. https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1998-07-17-61

- Otwinowska, A. (2014). Does multilingualism influence plurilingual awareness of Polish teachers of English? International Journal of Multilingualism, 11(1), 97–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2013.820730

- Otwinowska, A. (2017). English teachers’ language awareness: Away with the monolingual bias? Language Awareness, 26(4), 304–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2017.1409752

- Polkinghorne, D. E. (1995). Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 8(1), 5–23.

- Rambøll Management. (2016). Evaluering av særskilt språkopplæring og innføringstilbud [The Evaluation of the Special Language Tuition and Introduction Offer]. https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/tall-og-forskning/forskningsrapporter/evaluering-av-sarskilt-sprakopplaring-2016.pdf

- Randen, G. T., Danbolt, A. M. V., & Palm, K. (2015). Refleksjoner om Flerspråklighet og Språklig Mangfold i Lærerutdanningen [Reflections on multilingualism and linguistic diversity in teacher education]. In M. Lindmoe, G. T. Randen, T.-A. Skrefsrud, & S. Østberg (Eds.), Refleksjon & Relevans. Språklig og Kulturelt Mangfold i Lærerutdanningene [Reflection & relevance: Linguistic and cultural diversity in teacher education programmes] (pp. 65–94). Oplandske Bokforlag.

- Schembri, N., & Jahić Jašić, A. (2022). Ethical issues in multilingual research situations: A focus on interview-based research. Research Ethics Review, 18(3), 210–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/17470161221085857

- Statistics Norway. (2023a). Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents. https://www.ssb.no/befolkning/innvandrere/statistikk/innvandrere-og-norskfodte-med-innvandrerforeldre

- Statistics Norway. (2023b). Pupils in primary and lower secondary school. Pupils with native language training, Bilingual Education or Adapted Education 2008-2023. https://www.ssb.no/statbank/table/07523/tableViewLayout1/

- Tishakov, T., & Tsagari, D. (2022). Language beliefs of english teachers in norway: Trajectories in transition? Languages, 7(2), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020141

- Vikøy, A., & Haukås, Å. (2023). Norwegian L1 teachers’ beliefs about a multilingual approach in increasingly diverse classrooms. International Journal of Multilingualism, 20(3), 912–931. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2021.1961779

- Vogel, S., & García, O. (2017). Translanguaging. In G. W. Noblit (Ed.), Oxford research encyclopedia of education (pp. 1–22). CUNY Academic Works. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.181

Appendix

Transcription system

-- Self-interrupted speech

(…) Part of the speech removed

[] Researchers’ clarification