?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The multidisciplinary fields of public administration (PA), public policy sciences (PP), and nonprofit studies (Nonprofit) contribute in different ways to interdisciplinary knowledge integration in public affairs. At the field and topic level, we examine the variety and coherence of the disciplinary knowledge that each field draws upon when conducting research. Our analyses focus on citations from articles published between 2009–2020 in PA, PP, and Nonprofit journals indexed in Web of Science (n = 991,627). The contributions of each field are shaped by their distinct disciplinary origins. PA is more insular than PP and Nonprofit, in part due to its need to adopt new paradigms because of rapid, substantial shifts in public administration practice. Although Nonprofit achieves relatively more interdisciplinary knowledge integration, public affairs is heavily influenced by knowledge integration in PP. We identify variation in interdisciplinary knowledge integration across research topics and discuss possible explanations for the observed patterns.

Academic knowledge integration is essential for innovation and problem-solving, especially in applied fields of study like public affairs (National Academies, Citation2005). Knowledge integration is the meaningful combination of theories, concepts, methods, and ideas from two or more areas of research (Rafols & Meyer, Citation2010). Recently, scholars and journal editors have called for more attention to knowledge integration in public affairs that considers that contributions of nonprofit studies (Nonprofit), public administration (PA) and public policy sciences (PP) (LePere-Schloop & Nesbit, Citation2022). A greater understanding of knowledge integration in and across PA, PP, and Nonprofit can clarify the contributions of each field to public affairs, help orient doctoral students to the field, and identify areas where greater knowledge integration can take place.

Although PA, PP and Nonprofit are each multidisciplinary fields,Footnote1 meaning they draw on a variety of disciplinary knowledge, they have distinct disciplinary origins. Broadly, PA and PP have stronger roots in political science and are influenced by management and economics, respectively (Ascher, Citation1986; Guy, Citation2003). Nonprofit is historically grounded in sociology and social work with more recent influence from public administration (Mirabella & Wish, Citation2000; Smith, Citation2003). Their divergent disciplinary origins suggests that PA, PP, and Nonprofit might make different contributions to interdisciplinary knowledge integration in public affairs.

This study addresses two research questions: (1) How do the fields of PA, PP, and Nonprofit journals each contribute to interdisciplinary knowledge integration in public affairs? (2) How do patterns of interdisciplinary knowledge integration vary across topics of mutual interest at the nexus of PA/PPFootnote2 and Nonprofit? We draw on a conceptual framework and bibliometric methods from the science of science, and recently published public affairs research. Specifically, we use Rafols and Meyer’s (Citation2010) framework for assessing interdisciplinary knowledge integration, a typology of research topics at the nexus of PA/PP and Nonprofit developed by LePere-Schloop and Nesbit (Citation2022), and bibliometric techniques to analyze citations from articles published in the three core nonprofit journals and forty-two “Public Administration” journals indexed in the Web of Science database (n = 991,627).

Previous research has attempted to provide a disciplinary perspective on PA, PP and Nonprofit research, but in a limited way. While all three fields publish bibliometric studies assessing their respective field (e.g. Adams et al., Citation2016; Kumar et al., Citation2020; Ma & Konrath, Citation2018), few of these articles consider the most cited academic disciplines. This is an important omission because attending to disciplinary contributions to PA, PP and Nonprofit facilitates more intentional and systematic interdisciplinary knowledge integration in each respective field, and public affairs overall. Additionally, it can help students and early career scholars to understand how different disciplines contribute to public affairs scholarship and to ascertain how their own research fits within that amalgamation of perspectives.Footnote3 This will aid these scholars as they learn how to effectively communicate and contribute within the multidisciplinary public affairs space. Finally, findings from this study can be used to reflect and dialogue on how disciplinary training and norms shape understandings of methodology and epistemology, which in turn influences peer evaluation processes and public affairs scholarship—in both positive and negative ways.

Interdisciplinary knowledge integration

PA, PP, and Nonprofit are all multidisciplinary fields. Multidisciplinarity occurs when multiple disciplines contribute to knowledge in an area or field, but their contributions to scholarship are largely independent of each other. Interdisciplinarity means that there is knowledge integration across the multiple contributing disciplines, meaning that the contributions from scholars in different disciplines are interdependent.

Interdisciplinary knowledge integration is research that combines the perspectives, concepts, theories, methods, or information from two or more bodies of knowledge with the aim of advancing fundamental understanding (Rafols & Meyer, Citation2010). While research typically makes small, incremental gains in knowledge, the aim of knowledge integration is much greater. Knowledge integration fundamentally alters and shifts predominant paradigms within an area of knowledge be combining insights across disciplines. Knowledge integration is prized because it harnesses the potential of true interdisciplinarity and advances scientific innovation and breakthroughs (National Academies, Citation2005; Porter et al., Citation2006; Rafols & Meyer, Citation2010).

This begs the question of how to measure interdisciplinary knowledge integration. We do so using a framework proposed by Rafols and Meyer (Citation2010), which uses two primary measures—disciplinary diversity and citation network coherence. These measures have been used in a variety of bibliometric studies and widely accepted in the study of knowledge productions and integration (Morillo et al., Citation2003; Moya-Anegón et al., Citation2004, Citation2007; Porter et al., Citation2006; van Raan & van Leeuwen, Citation2002).

Rafols and Meyer define disciplinary diversity as the “number, balance, and degree of difference between the bodies of knowledge concerned” (Rafols & Meyer, Citation2010, p. 4). When research cites from a variety of disciplines, it broadens the foundation of knowledge upon which it is built. This increases the likelihood that the research is making substantial breakthroughs rather than incremental gains, as is typical for research produced within one discipline.

The second part of the Rafols and Meyer framework is network coherence. They define citation network coherence as “the extent that specific topics, concepts, tools, data, etc. used in the research process are related” (Rafols & Meyer, Citation2010, p. 4). Citation network coherence captures the extent to which a corpus of articles is citing the same research, which suggests that articles in the corpus share a common foundation of knowledge. High citation network coherence it likely to occur within an insulated area of research, such as within a specific discipline, or in areas of study with more disciplinary diversity coupled with a strong record of knowledge integration. Low citation network coherence means that a corpus does not share a strong foundation of knowledge but has the potential to do so.

Rafols and Meyer’s (Citation2010) framework puts these two concepts together into a 2 × 2 typology to describe the level of relative knowledge integration. Following prior work by LePere-Schloop and Nesbit (Citation2022), we adapt this typology as shown in .

shows four different relative knowledge integration scenarios across corpora of articles. Corpora with low disciplinary diversity and citation network coherence has the potential for knowledge integration within a single field. Corpora with low disciplinary diversity and high citation network coherence has achieved knowledge integration within a single field. Corpora with high disciplinary diversity and low citation network coherence has potential for interdisciplinary knowledge integration. Finally, corpora with high disciplinary diversity and high citation network coherence have achieved interdisciplinary knowledge integration. We use this typology to assess relative interdisciplinary knowledge integration at the field level (PA, PP, and Nonprofit respectively) and across topics of mutual interest to the fields as identified by LePere-Schloop and Nesbit (Citation2022).

Disciplinary origins and connections between PA, PP, and Nonprofit

The fields of PA, PP, and Nonprofit have intertwined over time so that each now contributes to public affairs scholarship, however, the distinct disciplinary origins of each field may shape the disciplinary knowledge it draws on to conduct research. PA has its roots in political science, a discipline dedicated to “the study of the nature and source of [social power] constraints and the techniques for the use of social power within those constraints” (Goodin & Klingemann, Citation1998). In the late 1800s and early 1900s, scholars advocated for understanding the administrative nature of public institutions separate from their political direction and control (Goodnow, Citation1900; White, Citation1948; Wilson, Citation1887). In 1939, the American Society for Public Administration emerged from the membership ranks of the American Political Science Association (Guy, Citation2003). Although PA continually reflects upon and revisits its relationship with political science (Guy, Citation2003; Kim, Citation2021; Rosenbloom, Citation2008; Tahmasebi & Musavi, Citation2011; Whicker et al., Citation1993), it is a multidisciplinary field that pulls theoretical and empirical insights from many different disciplines (Brewer, Citation1999; Nesbit et al., Citation2011; Raadschelders & Lee, Citation2011; Vigoda-Gadot, Citation2002; Wright, Citation2011). While PA is sometimes described as having an “identity crisis” (Denhardt, Citation1981; Ostrom, Citation2008; Zalmanovitch, Citation2014)—because major shifts in practice lead to re-conceptualizations of the field’s core tenets (Farazmand, Citation2012)—it is nonetheless a growing and robust field of study (Corley & Sabharwal, Citation2010; Raadschelders & Lee, Citation2011).

PP emerged as a distinct field of study at the same time and for many of the same reasons as PA. Woodrow Wilson’s call to focus on the administration of public agencies, not just their political dictates (Wilson, Citation1887), coincided with calls from prominent scholars across disciplines for behavioral research focused on individual decision-making and action (Ascher, Citation1986). Political scientists like Harold Lasswell and Charles Merriam applied a behavioralist focus to the study of politics, democracy, and aspects of social and economic welfare (Ascher, Citation1986). In the 1950s, Lasswell and others codified their behavioralist approach to public policy research as the “policy sciences” (Ascher, Citation1986). Policy sciences (PP) emerged as recognizable multidisciplinary field with a shared behavioralist and individual decision-making orientation to policy. Political support for data-driven decision-making in the 1960s lead to the establishment of academic programs and schools of public policy (Allison, Citation2006). In the 1970s and 80s, associations, research conferences, and journals focusing on public policy emerged, further solidifying PP as a distinct scholarly area (Chaudhuri, Citation2016). Many of these institutions also had a connection to PA, including the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management. PA and PP continue to share a close relationship due to their overlapping and complementary areas of research.

Nonprofit was more multidisciplinary at birth. Scholars from sociology, political science, social work, history, anthropology, psychology, and religion came together to form the Association of Voluntary Action Scholars (AVAS) in 1971 (Smith, Citation2003). While AVAS was a multidisciplinary space, sociology and social work were the best represented disciplines, and AVAS scholars focused on “voluntary action studies” (Bushouse et al., Citation2023). AVAS’ efforts to increase membership coincided with several historical events (e.g. Filer Commission, Tax Reform Act of 1968) that drew more attention to the nonprofit sector, particularly from policy makers and public administrators. In 1989, AVAS changed its name to the Association for Research on Nonprofit Organizations and Voluntary Action (ARNOVA) to attract scholars who were interested in studying formal nonprofits (Bushouse et al., Citation2023; Smith, Citation2003). The shift in focus from voluntary action to formal organizations in nonprofit studies coincided with the cooptation of the subfield of sociology of organizations by business schools in the 1990s (Besio et al., Citation2020; King, Citation2017). As scholarly interest in the nonprofit sector grew, university programs and academic centers started to proliferate (Mirabella, Citation2007; Mirabella et al., Citation2019; Soskis, Citation2020), leading to debates about the best place to locate nonprofit programs among the three most popular contenders—business, public administration, and social work (O’Neill & Young, Citation1988). Several prominent scholars argued in favor of locating Nonprofit within PA programs due to goal similarities between the two fields of study and the need for nonprofit and public managers to regularly interact and collaborate with each other (Cyert, Citation1988; Salamon, Citation1998; Young, Citation1999). By 2006, 47% of nonprofit programs were housed with PA programs (Mirabella, Citation2007; Mirabella & Wish, Citation2000). As a result, scholars with PA and PP backgrounds and training were teaching courses in nonprofit management and scholars conducting Nonprofit research were pursuing tenure inside of PA, PP and public affairs programs. Thus, the disciplinary composition of Nonprofit shifted from its origins in sociology and social work.

While PA, PP and Nonprofit have different disciplinary origins, each of the three fields contributes to public affairs scholarship. This raises the question of how the origins of each respective field shapes the multidisciplinary knowledge it draws on to contribute to public affairs, and the extent to which each field achieves interdisciplinary knowledge integration.

Disciplinary contributions to PA, PP, and Nonprofit

To better understand which disciplines Nonprofit, PA, and PP draw on to conduct research, we briefly review pertinent bibliometric studies from each field. A growing number of bibliometric studies focus on specific topics of research and are not pertinent to this review. We focus on bibliometric studies that seek to assess research at the field-level, and that consider the disciplinary knowledge used in PA, PP or Nonprofit research.

Several bibliometric studies seek to provide a portrait of PA (Abdolhamid et al., Citation2023; Kumar et al., Citation2020; Ni et al., Citation2017; Raadschelders & Lee, Citation2011; Vogel, Citation2014; Vogel & Hattke, Citation2022; Wright, Citation2011; Wright et al., Citation2004; Zuo et al., Citation2019). However, many of these studies do not consider academic discipline in their analysis (Abdolhamid et al., Citation2023; Kumar et al., Citation2020; Raadschelders & Lee, Citation2011; Vogel, Citation2014; Zuo et al., Citation2019). Because of this, we only consider three bibliometric studies of PA research. We therefore consider only the three bibliometric studies of PA research (summarized in Supplemental Appendix A). Based on these three studies, we expect articles in PA journals to frequently cite other PA journals, and political science, management, law, economics, and sociology journals. Based on these three studies, we expect articles in PA journals to frequently cite other PA journals, and political science, management, law, economics, and sociology journals.

Another handful of bibliometric studies focus on PP (Adams et al., Citation2014, Citation2016; Goyal, Citation2017; Nafi’ah et al., Citation2021). After excluding articles that do not consider academic discipline (Nafi’ah et al., Citation2021), we focus on three articles (summarized in Supplemental Appendix B). Based on these bibliometric studies, we expect articles in PP journals to cite economics, political science, public administration, and multidisciplinary journals.

Finally, we consider bibliometric analyses of Nonprofit research (Allison et al., Citation2007; Brudney & Durden, Citation1993; Bushouse & Sowa, Citation2012; Evans, Citation2022; Jackson et al., Citation2014; LePere-Schloop & Nesbit, Citation2023; Ma & Konrath, Citation2018; Shier & Handy, Citation2014) Several of these studies do not address which academic disciplines contribute to Nonprofit research (Bushouse & Sowa, Citation2012; Evans, Citation2022; Kang et al., Citation2021; Ma & Konrath, Citation2018). The remaining articles (summarized in Supplemental Appendix C) suggest several disciplines that contribute to Nonprofit. We expect that articles in Nonprofit journals will frequently cite sociology, social work, political science, management, PA, PP, and education journals.

Based on this review, across all public affairs journals we expect to see more citations of journals from political science, management, and economics journals.

Data and methods

We address our research questions by analyzing bibliographic data on articles published between 2009–2020 in Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly (NVSQ), Nonprofit Management and Leadership (NML), Voluntas, and the forty-two PA and PP journals classified as “Public Administration” in the Web of Science (WoS) source index. We use WoS data for our analysis because this publisher-independent bibliographic database is well-maintained and employs rigorous journal indexing standards (Clarivate, Citation2021). Using the WoS database means that multiple public affairs journals that were not indexed in WoS are excluded from our analysis including Journal of Nonprofit and Public Affairs, Voluntary Sector Quarterly. However, by drawing on WoS data we can focus our analysis on citations of the most impactful journals across disciplines.

provides an overview of our data and methods, which we briefly describe here (see Supplemental Appendices D-F for a thorough break down). After downloading bibliographic data from WOS, we used VOSviewer (Van Eck & Waltman, Citation2010) to visualize multiple journal co-citation networks with clusters. We used R (R Core Team, Citation2020) to analyze cluster membership. We then used a variety of R packages- notably Bibliometrix (Aria & Cuccurullo, Citation2017), StringR (Wickham, Citation2019), and ggplot2 (Wickham, Citation2020)- to extract, classify and analyze cited journals and citations from the WoS data.

Table 1. Summary of research questions, data, and methods used for analyses.

We classify journals by discipline because disciplinary knowledge integration is the focus of our study. While disciplinary classification may not fully capture the diversity of research traditions engaged in knowledge production in a journal, it is a common approach in bibliometric studies of knowledge production and integration (Rafols & Meyer, Citation2010). To classify journals by discipline, we used the Science-Metrix (Citation2021)Footnote4 journal classification system, developed by clustering multiple classification systems (including WoS) to provide a three-tiered (domain, field, subfield), mutually-exclusive journal discipline taxonomy (Archambault et al., Citation2011). To streamline our findings, we consolidated some classifications (see Supplemental Appendix G). Since PA, PP, and Nonprofit are not subfields in the Science-Metrix typology, we followed LePere-Schloop and Nesbit (Citation2022) in classifying journals to the three fields. We also drew upon LePere-Schloop and Nesbit’s (Citation2022) taxonomy of research categories at the nexus of PA/PP and Nonprofit3 to examine citations across a subset of “cross-citing” articles (PA and PP articles that cited at least one Nonprofit journal and vice-versa).

Our analyses focused on classified WoS journal citations from articles published in public affairs journals (n = 991,627) and cross-citing articles (n = 110,167). We examined the distribution of disciplinary journal citations across articles in PA, PP, and Nonprofit journals respectively, and the most frequently cited disciplines across cross-citing articles by research category. We also used the Rafols and Meyer’s (Citation2010) typology to visualize and assess relative interdisciplinary knowledge integration for articles published between 2009–2020 across fields and research categories. We operationalized disciplinary diversity using Shannon’s index, where pi is the proportion of citations across a given set of articles that cite a journal from field i:

Results

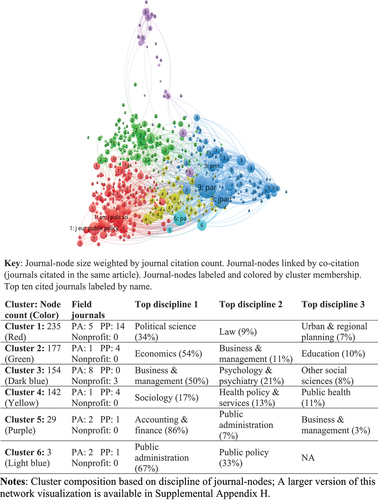

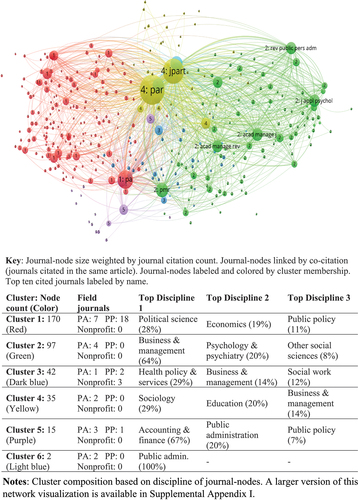

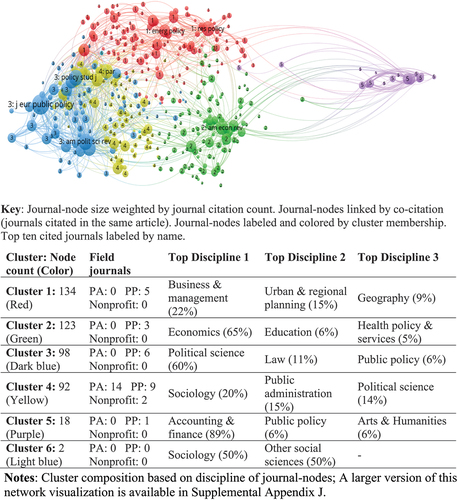

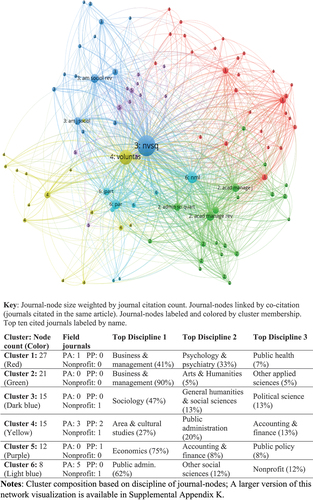

Our first set of results consider interdisciplinary knowledge integration in public affairs and the respective contributions of PA, PP, and Nonprofit. are visualizations of journal co-citation networks based on all articles published in public affairs journals, and then PA, PP, and Nonprofit journals respectively. Journal co-citation networks are helpful for understanding which disciplines/journals are cited across a group of articles, and which disciplines/journals are frequently cited together.

Each co-citation network is visualized in the same manner. Each node is a journal that was cited at least eighty times across the collection of articles used for the analysis. Node size is weighted by the number of times a journal was cited. Two journal nodes are linked if both journals were cited by the same article. The color and number of each node indicates its’ cluster membership; journal-nodes in the same cluster were more frequently cited together. If a co-citation network contains several clusters with balanced proportions of journals from multiple disciplines (e.g., equal proportions of PA, political science, and economics journals), this is an early indication of interdisciplinary knowledge integration. If a co-citation network contains clusters that are each dominated by one discipline, this suggests a lower interdisciplinary knowledge integration. Each co-citation network figure includes a table summarizing information about clusters in the network including the number of journals contained in each cluster and their breakdown by field (PA, PP, or Nonprofit), and the top three disciplines cited by journals in the cluster. We also provide a narrative description of key findings for each journal co-citation network below.

For example, presents the journal co-citation network based on an analysis of articles published in all public affairs journals (PA, PP, and Nonprofit). The ten most frequently cited journals have the largest nodes and are labeled by name. We see that the PAR (Public Administration Review) and JPART (Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory) nodes are both relatively large, meaning that these journals were frequently cited. We also see that PAR and JPART share a thicker connection and belong to the same cluster, meaning that they were frequently cited together. The table below shows the size of each cluster and its’ composition based on the three most prominent disciplines of journal-nodes in the cluster. JPART and PAR belong to cluster 3, which contains 154 journal-nodes that are primarily distributed across three disciplines business & management (54%), psychology and psychiatry (21%), and other social sciences (8%). We now discuss each co-citation network in turn.

The public affairs journal co-citation network presented in (and Supplemental Appendix H) suggests that, overall, public affairs cites a variety of disciplinary journals. This network is dominated by clusters 1 through 4, each of which is composed of a diverse set of journal-nodes from different disciplines. Clusters 1 and 4 are the most diverse and balanced, given that the most prominent discipline in each cluster accounts for less than forty percent of the journal-nodes. Clusters 2 and 3 are less diverse and balanced, dominated respectively by economics journals (54%) and business and management journals (50%). The final two clusters, 5 and 6, are smaller and overwhelmingly dominated by accounting and finance (86%) and PA (67%) respectively, suggesting that some public affairs research engages with focused traditions of disciplinary knowledge. The top ten most cited journals are primarily distributed across cluster 1 containing that most cited PP journals, and cluster 3 with the most cited PA journals and NVSQ. This suggests that PA and PP make distinct contributions to public affairs and that the contribution of Nonprofit may align with that of PA. Overall, these findings conform to expectations based on the disciplinary diversity apparent in our review of previous bibliometric studies and the history of the respective fields that comprise public affairs. We next examine PA, PP, and Nonprofit in turn.

An examination of the journal co-citation network in (and Supplemental Appendix I) suggests that, while articles published in PA journals most frequently cite PA and business & management journals, the field may be achieving some degree of interdisciplinary knowledge integration. First, while clusters 4 and 6 are small in terms of journal-node membership size, they each contain some of the most frequently cited journals (all of which are PA journals) such that these clusters dominate the network. For example, cluster 4 contain PAR and JPART, by far the largest (most cited) journal-nodes in the network. Cluster 2, one of the largest clusters in the network, which contains several of the top ten most cited journal-nodes, is dominated by business & management journals (64%). Clusters 1 and 3, while different in size, are similar in that they are relatively diverse and balanced in terms of journal-node discipline. Finally, cluster 4 is dominated by a single discipline: accounting & finance. It is also interesting to note that none of the top ten cited journals in the PA co-citation network are PP or Nonprofit journals. As anticipated based on our literature section, articles published in PA journals draw upon knowledge from business & management, political science, economics, and sociology—although they primarily cite PA and business & management journals. Somewhat surprisingly, PA journals cite disciplinary journals outside of public affairs more frequently than PP or Nonprofit journals.

An inspection of the PP journal co-citation network in (and Supplemental Appendix J) suggests a contrasting set of findings. While two clusters, 1 and 4, are relatively diverse and balanced in terms of journal-node discipline, the other four are dominated by journals from a single discipline: cluster 2 by economics (65%), cluster 3 by political science (60%), cluster 5 by accounting & finance (89%) and cluster 6 by sociology (50%) respectively. However, unlike the PA network, the top ten cited journals in the PP network are more evenly distributed across different clusters, and no single journal dominates the network. Overall, this suggests that, while sub-streams of research in PP journals primarily draw on disciplinary knowledge from either economics, political science, accounting & finance, or sociology, on the whole PP may be achieving higher levels of interdisciplinary knowledge integration than PA. These findings align with our literature section, which suggested that articles published in PP journals would frequently cite PA, political science, economics, management, psychology, and hard sciences journals.

Finally, the Nonprofit journal co-citation network presented in (and Supplemental Appendix K) suggests that the field draws on diverse disciplinary knowledge and that individual Nonprofit journals may play distinct roles in integrating this knowledge. Three of the six clusters in this network are dominated by journals from a single discipline: cluster 2 by business & management (90%), cluster 5 by economics (75%), and cluster 6 by PA journals 62%). The other three clusters (1, 3, and 4) are balanced across multiple disciplines. Like the PP network, the top ten cited journals are evenly distributed across different clusters, however, like the PA network, the network is dominated by two field journals: NVSQ and Voluntas. Also interesting is the fact that NVSQ, NML & Voluntas, each belong to a different cluster: NVSQ is often cited with sociology, general, and political science journals; NML is often cited with PA, other social science, and nonprofit journals; and Voluntas is often cited with area & cultural studies, PA, and accounting & finance journals. Overall, this suggests that articles in Nonprofit journals are drawing on a variety of disciplinary knowledge—particularly from business & management, sociology, economics, and PA—and that each Nonprofit journals is playing a distinct role in integrating interdisciplinary knowledge. Again, these findings align with our literature section, although social work journals are not well represented despite the important role that social work played in establishing the Nonprofit field.

To further clarify the contribution of each field to interdisciplinary knowledge integration in public affairs, we next examine , a series of bar charts presenting the overall disciplinary breakdown of journal citations from articles published in Nonprofit, PA, and PP journals respectively. The first bar graph shows that across articles published in Nonprofit journals, 22% of journal citations are Nonprofit, 20% are business & management, 8% are sociology or psychology & psychiatry respectively, 7% are public administration, 6% are economics, 5% are political science, and journals from each other discipline are cited less than 5% of the time. This suggests that Nonprofit draws on diverse disciplinary knowledge in a balanced manner. The middle bar graph shows that across articles published in PA journals, 39% of journal citations are PA, 17% are business & management, 8% are political science, 6% are economics, 5% are public policy, and journals from each other discipline are cited less than 5% of the time. These findings suggest that articles published in PA journals draw heavily on PA knowledge and, to a more limited extent, knowledge from a handful of outside disciplines. Finally, the third bar graph shows that across articles published in PP journals, 19% of journal citations are political science, 18% are public policy, 14% are economics, 6% are accounting & finance, 6% are public administration, and journals from each other discipline are cited less than 5% of the time. In contrast to PA, these findings suggest that PP draws on knowledge from a wider set of disciplines and does so in a more balanced manner. Overall, these findings align with those related to earlier examinations of co-citation networks for each field.

Figure 6. Percent of citations by discipline across articles published in PA, PP, and Nonprofit journals between 2009–2020.

Our final results at the field-level are presented in , which follows Rafols and Meyer (Citation2010) to examine relative knowledge integration by considering whether citation network coherence and cited journal diversity for articles in each field are above or below the standardized mean. The first column in the table lists each field. The second and third columns indicate whether articles classified to that category have citation network coherence and cited journal diversity above or below the standardized mean. The final column presents the quadrant the research category maps into, indicating its relative interdisciplinary knowledge integration. Overall, PP has more cited journal diversity than Nonprofit and PA, but lower citation network coherence than the other fields. PP draws on knowledge from a diverse set of disciplines, perhaps because of the wide variety of policy domains in PP research, but has a relatively weak foundation of shared knowledge, perhaps because PP research is often driven by empirical more than theoretical concerns. In contrast, PA has a stronger foundation of shared knowledge (citation network coherence) relative to PP but draws on knowledge from a less diverse set of disciplines. This suggests that PA is more internally focused relative to the two other fields. With above average citation network coherence and cited journal diversity, Nonprofit has a stronger record of interdisciplinary knowledge integration relative to PA and PP, which suggests that articles in Nonprofit journals share a knowledge foundation while drawing on knowledge from a variety of disciplines. Finally, public affairs overall aligns closely with PP, in that both have above average cited journal diversity but below average citation network coherence, suggesting potential for interdisciplinary knowledge integration. As a robustness check, we conducted a similar analysis over three five-year increments (see Supplemental Appendix L). The stability of our findings suggest that the three fields achieve different levels of relative interdisciplinary knowledge integration, and that that PP plays a leading role in shaping interdisciplinary knowledge integration in public affairs.

The next set of results address our second search question by considering disciplinary journal citation patterns and interdisciplinary knowledge integration in research on topics of mutual interest to the three fields. These analyses focus on the subset of cross-citing articles from our full WoS dataset. Recent work by LePere-Schloop and Nesbit (Citation2022) classified this subset of articles using a taxonomy of research categories at the nexus of PA, PP and Nonprofit. We leverage this taxonomy to examine interdisciplinary knowledge integration across the research categories in the taxonomy.

We first examine the disciplinary distribution of journals cited across articles in each research category as presented in the first three columns of . The first column in the table lists the research categories identified by LePere-Schloop and Nesbit (Citation2022) in order of most to least frequently occurring in our dataset. The second column indicates the total number of articles classified to this category and their breakdown by journal field. The third column presents the breakdown of cited journal discipline across articles in each category.

Table 2. Research categories at the PA/PP-Nonprofit nexus with article count, dominant field, and top four cited disciplines.

An examination of suggests several trends across research categories. Across all fifteen categories, Nonprofit journals are among the top four disciplines cited. PA journals are also among the top four disciplines cited across all categories but one: Philanthropy and charitable giving. In contrast, PP is only in the top four cited disciplines for three categories - Public policy & governance, Public service provision, and State of research and teaching. These results make sense given the inclusion criteria for this subset of articles. Given that Smith (Citation2003) recounted that scholars from sociology, political science, social work, history, anthropology, psychology, and religion came together to form ARNOVA, we might expect to find these disciplines well represented in . However, only sociology, political science, and psychology are consistently represented. Sociology is in the top four cited disciplines for four categories (5, 8, 12, and 13), psychology & psychiatry for three (1, 9, and 10), and political science for two (3 and 13). Economics is well represented in as among the top four cited disciplines in four categories (7, 10, 11, and 14), and business & management is among the top four disciplines cited across all but two categories (3 and 13). Overall, this suggests variation in the disciplinary knowledge drawn upon for public affairs research in these fifteen categories. Scholars publishing in public affairs journals tend to cite sociology journals when conducting research at the organizational/mezzo and macro-level, and psychology & psychiatry journals when doing micro-level research. Business & management, economics, and political science journals are not closely associated with particular levels of analysis but rather relevant topical areas.

Finally, presents our findings on relative interdisciplinary knowledge integration across the fifteen research categories (also see Supplemental Appendix L that presents a visualization like ). The first column in the table lists research categories from most to least frequent, while the second indicates the dominant field for each category based on article counts. The third and fourth columns indicate whether articles classified to that category have citation network coherence and cited journal diversity above or below the standardized mean. The final column presents the quadrant the research category maps into, indicating its relative interdisciplinary knowledge integration. Relative to other research categories, Volunteering and Philanthropy and charitable giving achieve relatively high interdisciplinary knowledge integration because they have citation network coherence and cited journal diversity above the mean. It is interesting to note that both categories are at the micro-level of analysis. Six research categories have below average citation network coherence but above average cited journal diversity, indicating potential for interdisciplinary knowledge integration: Organizational performance, accountability, and transparency; Public policy & governance; Civil society; Sector relations and distinctions; and Civic engagement and political participation. These research categories tend focus on phenomena at the mezzo, macro, or multi-levels of analysis. A robustness check confirmed the stability of these findings over three five-year increments (see Supplemental Appendix M). Together, the results presented in Figure 8 and suggest that public affairs scholars are achieving different levels of interdisciplinary knowledge integration depending on their area of research, and that they have an opportunity to further interdisciplinary knowledge integration by identifying and consistently citing a core of foundational work relevant to their area of research.

Table 3. Relative interdisciplinary knowledge integration by category in the PA/PP-Nonprofit nexus from 2009–2020.

Discussion

In this article, we have sought to answer two research questions. Our first question was: How do the fields of PA, PP, and Nonprofit each contribute to interdisciplinary knowledge integration in public affairs? We find different patterns of disciplinary journal citation and interdisciplinary knowledge integration across the three fields. Nonprofit achieves more interdisciplinary knowledge integration relative to PA, PP, and public affairs overall. PP is well-positioned for greater knowledge integration; it cites diverse journals but shares a smaller foundation of knowledge across articles. PA is more insular than either Nonprofit or PP. Both cited disciplinary diversity and network coherence are relatively low within PA journals. Overall, public affairs is positioned for greater interdisciplinary knowledge integration, and is heavily influenced by knowledge integration in PP.

The historical backgrounds of these three fields help to explain these differences in relative interdisciplinary knowledge integration. First, it is not surprising that Nonprofit has greater knowledge integration because it was multidisciplinary from the outset. ARNOVA was created by scholars from multiple disciplines (Smith, Citation2003). While Nonprofit has developed a close alliance with public affairs over time due to the placement of Nonprofit programs (Mirabella, Citation2007; Mirabella & Wish, Citation2000), it has remained strongly multidisciplinary. Additionally, Nonprofit is a younger, smaller field than both PA and PP. Fewer Nonprofit journals have been indexed in the Web of Science. The relative size of Nonprofit might lower barriers to creating a shared foundation of knowledge, resulting in greater interdisciplinary knowledge integration.

PA and PP, on the other hand, originated as subfields of political science, to which both fields have maintained a close connection (Ascher, Citation1986; Guy, Citation2003; Rosenbloom, Citation2008). As PP has grown, it has become increasingly multidisciplinary due to its behavioralist focus on public policy—an interest shared by multiple disciplines (Ascher, Citation1986). The sheer number and variety of policy topics (e.g. environmental policy, social policy) also pushes PP toward multidisciplinary. This topical diversity, however, might also account for the lower network coherence in PP relative to Nonprofit. While PP overall might have lower citation network coherence, individual policy areas could exhibit greater coherence because scholars working within the same topic area are more likely to share a foundation of knowledge. Another potential explanation for PP’s lower network coherence could be its close ties with economics (14.34% of citations). Economists focus on proving the credibility of their estimates of causal impacts and their theory-building focuses on strong statistical models. This may result in lower citation network coherence because studies in PP are less concerned with building a foundation of abstract theoretical work.

PA has remained more insular than PP, although it is still a multidisciplinary field. One reason for this insularity is that PA has had to work hard to build itself as a field and to establish a cogent identity. Throughout its history, PA has had to grapple with an “identity crisis” due to several shifts in the dominant paradigm of the field, particularly regarding the role of public agencies vis-à-vis the political apparatus and the public (Denhardt, Citation1981; Ostrom, Citation2008; Hafer, Citation2016; Zalmanovitch, Citation2014). These shifting paradigms are often driven by or accompany major re-conceptualizations of PA’s core tenets due to significant changes in the political environment and public administration practice (Farazmand, Citation2012). These paradigm shifts have made it difficult for PA to build greater citation network coherence and disciplinary diversity due to the need to re-build consensus around a dominant paradigm, which makes it difficult to sustain the normal science boom of research in a discipline’s life cycle (Kuhn, Citation1970). This likely accounts for the lower network coherence and disciplinary diversity of PA relative to PP and Nonprofit.

Our second research question was: (2) How do patterns of interdisciplinary knowledge integration vary across topics of mutual interest at the nexus of PA/PP and Nonprofit? We find that research on Volunteering and Philanthropy and charitable giving have the most interdisciplinary knowledge integration of all categories in the PA/PP-Nonprofit nexus. We propose two explanations.

First, research on these categories may have greater interdisciplinary knowledge integration because the phenomena of volunteering and charitable giving are prevalent actions that occur in many organizational and geographical contexts (Musick & Wilson, Citation2007). Because of their ubiquity, many disciplines develop questions about these phenomena and theoretical perspectives about how and why they occur. For example, public affairs is interested in volunteering because it occurs in public and nonprofit organizations (Brudney & Yoon, Citation2021) and because many public policies are designed to support and grow volunteerism (Nesbit & Brudney, Citation2013). Psychologists are interested in volunteers’ motivations (Clary & Snyder, Citation1999). Sociologists seek to understand how social institutions both shape and are shaped by volunteering (Wilson & Musick, Citation1997). Economists seek to understand volunteering by exploring the costs and benefits of unpaid labor (Handy & Srinivasan, Citation2004). Other disciplines have their own unique perspectives to help explain why and how people volunteer and how volunteering impacts individuals, organizations, and communities. These phenomena lend themselves to multidisciplinary inquiry, leading to cited discipline diversity.

Second, the study of these phenomena emerged in a multidisciplinary space. Scholars from various disciplines founded ARNOVA in part because of their shared interest in voluntary action, like volunteering and charitable giving (Smith, Citation2003). We assert that this created a need and venue for establishing a shared interdisciplinary understanding of these phenomena, leading to citation network coherence. Because they were coming together in one association, early scholars of voluntary action were aware of academic work produced outside their home discipline. These scholars worked to build a shared foundation of knowledge to engage across disciplinary boundaries, clarifying definitions and developing an understanding of how their discipline informed their work relative to other disciplinary perspectives. As such, citation network coherence was crucial for moving forward. We assert that that coherence has carried over into the current academic research on these topics.

While it is interesting that both Volunteering and Philanthropy and charitable giving are micro-level phenomena, we assert that there is no single explanation (e.g., level of analysis) which drives interdisciplinary knowledge integration across these categories. The trajectory to interdisciplinary knowledge integration seems to depend on multiple factors, including the disciplinary origins of the topic, the size and age of the field, the field’s own historical development, and the nature of the topic itself. Still, we believe that scholars can use these insights to reflect more critically upon the level of knowledge integration within their research focus area and how it might relate to the factors listed above.

For example, a PA scholar studying Public service provision can recognize that achieving citation network coherence in this area is quite a feat given the re-conceptualizations of public service provision inherent in the New Public Management and New Public Governance paradigm shifts (Farazmand, Citation2012; Hood, Citation1991; Osborne, Citation2006). These paradigm shifts within the practitioner realm may have led to an “identity crisis” among PA scholars (Denhardt, Citation1981; Ostrom, Citation2008; Zalmanovitch, Citation2014), but through their tight connections to the world of practice, PA scholars have maintained relevance by quickly shifting their research paradigms accordingly.

The same PA scholar can also recognize opportunities to broaden their perspective in productive ways. Disciplinary diversity within Public service provision articles is relatively low, because this work primarily cites PA journals. PA scholars’ research on Public service provision could be more robust and practically relevant when better integrated with relevant Nonprofit research. For example, Nonprofit research has shown that government contracting can alter nonprofit organizations’ activities, lead to mission drift, and/or be affected by voluntary failure (Brooks, Citation2000; Chavesc et al., Citation2004; Lu & Zhao, Citation2019; Salamon, Citation1987). PA scholars’ research on Public service provision could be more robust and practically relevant when better integrated with relevant Nonprofit research. We encourage scholars to thoughtfully reflect on whether their own research could benefit from inviting in greater disciplinary diversity.

Together, our results suggest that PA, PP, and Nonprofit play distinct roles in interdisciplinary knowledge integration in public affairs. Their differing historical trajectories account for some differences in the relative level of knowledge integration across the three fields. However, bibliometric methods open up opportunities for public affairs scholars to engage in systematic critical self-reflection grounded in empirical research. Scholars can now use bibliometric studies, like this one, to start conversations about where each field could and should be heading and how PA, PP, and Nonprofit scholars can work more collaboratively to build interdisciplinary public affairs knowledge. This greater knowledge integration can not only lead to major gains in academic knowledge, but could also have profound impacts on practice as well—thus meeting the primary goals of interdisciplinarity (National Academies, Citation2005).

We see particular relevance of this study for doctoral students and early career scholars. First, a descriptive portrait of the contributions of different disciplines to the study of public affairs helps students to see how the research they read—and ultimately how their own research—fits within the larger body of public affairs scholarship. This will help doctoral students to make more informed choices about the knowledge bases they want to specialize in and how they can direct their research to make a stronger contribution. Second, because public affairs is a multidisciplinary field, students and early career scholars need to learn how to communicate effectively across disciplinary boundaries—and our results help students to know where those boundaries are and which disciplines dominate the study of particular topics. Third, our results are a springboard for conversations about the different assumptions and epistemological skews embedded in each discipline and how those perspectives then influence and shape public affairs scholarship—in both positive and negative ways. Within that understanding, public affairs scholars can be more intention about knowledge integration to help overcome the blind spots and limitations of any one disciplinary perspective.

Our study also raises a potential concern about one or more disciplines becoming dominant in either PA, PP, Nonprofit, or public affairs broadly. Scholars serve as gatekeepers to future knowledge in their roles as journal editors and peer reviewers. The danger is that the disciplinary training and norms of reviewers are applied inflexibly rather than reflexively in peer reviews of manuscripts, tenure packages, etc. Reviewers can sometimes be unnecessarily (and even unfairly) harsh when they encounter theories, methods, or epistemologies that are unfamiliar or marginalized in their discipline. It is not uncommon for reviewers to apply criteria that are inappropriate, such as when a quantitative scholar applies the criteria of validity, reliability, replicability to an interpretive study (Schwartz-Shea & Yanow, Citation2013). Herein lies the problem. When a multidisciplinary space is dominated by one or more disciplines, it can quickly become an academic arena that is unfriendly toward and unaccepting of other disciplines, and unfamiliar approaches to research. We argue that if public affairs scholars desire to maintain this space as a robust multidisciplinary discipline and realize its’ potential for interdisciplinary knowledge integration, they must actively educate themselves about relevant but unfamiliar theories, methodologies, and epistemologies, especially those less prominent in their home discipline. To that end, articles and special issues designed to foster theoretical, methodological, and epistemological inclusivity (e.g. Coule et al., Citation2020; Wessels, Citation2023) are critical to interdisciplinary knowledge integration in public affairs. Future bibliometric research could also play a valuable role in understanding the extent to which public affairs research draw on different methodologies and epistemologies, and the extent to which this knowledge is integrated over time.

We acknowledge that our results are biased toward perspectives from the Global North. Our sample is based on journals that are indexed in the Web of Science, which has historically been dominated by journals housed in institutions in the Global North. In the past twenty years, WoS has changed their editorial policy to include more regional journals from around the world, which resulted in adding 1,600 regional journals to WoS 2005 and 2010—almost half of the newly indexed journals (Larsen & Von Ins, Citation2010; Michels & Schmoch, Citation2012; Testa, Citation2011). We applaud WoS for this effort. We also acknowledge the difficulties of developing a truly global perspective using only English-language journal publications. Future research can help to illuminate the academic contributions of the Global South to the nexus of PA, PP, and Nonprofit.

Conclusion

We argue that a close investigation of the relative contributions of PA, PP, and Nonprofit can help scholars to understand public affairs more broadly. The first contribution of our study is to provide a descriptive portrait of how PA, PP, and Nonprofit contribute in different ways to the study of public affairs based on their disciplinary origins. Our second contribution is to show the relative interdisciplinary knowledge integration at the field-level. Finally, we examine and compare the disciplines scholars in these three fields draw upon to investigate specific research topics. These analyses can help all public affairs scholars to be more intentional about searching for and both using and valuing knowledge foreign to their home disciplines. There are many simple steps that scholars can take—as authors, reviewers, and editors—to increase knowledge integration (see LePere-Schloop & Nesbit, Citation2022 for several suggested strategies s). This will help to maintain public affairs as a strong multidisciplinary field of study and will enable greater knowledge integration that can shift scholars’ paradigm in ways that enhance public servants’ ability to solve complex public problems.

Supplemental Appendices and Slide Deck

Download Zip (5.6 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2024.2349477.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Megan LePere-Schloop

Megan LePere-Schloop, Ph.D. is an assistant professor of public and nonprofit management in the John Glenn College of Public Affairs at the Ohio State University. Her research focuses on community philanthropic foundations, sexual harassment in fundraising, and knowledge production in the fields of public affairs and organization studies. In 2020, she was honored to receive the OSU Alumni Award for Distinguished Teaching.

Rebecca Nesbit

Rebecca Nesbit, Ph.D. is an associate professor of nonprofit management in the Department of Public Administration and Policy at the University of Georgia. Dr. Nesbit’s research explores issues pertaining to volunteer programs, volunteers’ characteristics and motivations, and volunteer management in public and nonprofit organizations.

Notes

1. Throughout this manuscript we use “field” to denote a multi-disciplinary area of study (e.g., public affairs, PA, PP, Nonprofit) and “discipline” to denote a traditionally singular area of the academy (e.g., political science, sociology, psychology).

2. We follow the terminology of LePere-Schloop and Nesbit (Citation2022) since we draw on their typology of research topics at the nexus of PA/PP and Nonprofit for this study.

3. This manuscript has an accompanying teaching note and slide desk to facilitate discussion in public affairs doctoral courses.

4. Numerous public scientific agencies, including the U.S. National Science Foundation rely on this taxonomy for bibliometric analysis (Science-Metrix, Citation2021).

References

- Abdolhamid, M., Abdolhoseinzadeh, M., Esmaeili Givi, M., Saberi, M. K., Mirezati, S. Z., & Amiri, M. R. (2023). Bibliometric analysis of global scientific research on public administration: 1923–2020. International Journal of Information Science and Management (IJISM), 21(1), 75–96.

- Adams, W. C., Infeld, D. L., Minnichelli, L. F., & Ruddell, M. W. (2014). Policy journal trends and tensions: JPAM and PSJ. Policy Studies Journal, 42(S1), S118–S137. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12051

- Adams, W. C., Lind Infeld, D., Wikrent, K. L., & Bintou Cisse, O. (2016). Network bibliometrics of public policy journals. Policy Studies Journal, 44(S1), S133–S151. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12149

- Allison, G. (2006). Emergence of schools of public policy: Reflections from a founding dean. In R. E. Goodin, M. Moran, & M. Rein (Eds.), The oxford handbook of public policy (pp. 58–79). Oxford University Press.

- Allison, L., Chen, X., Flanigan, S. T., Keyes-Williams, J., Vasavada, T. S., & Saidel, J. R. (2007). Toward doctoral education in nonprofit and philanthropic studies. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 36(4_suppl), 51S–63S. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764007305054

- Archambault, É., Beauchesne, O. H., & Caruso, J. (2011). Towards a multilingual, comprehensive and open scientific journal ontology. In Proceedings of the 13th international conference of the international society for scientometrics and informetrics (Vol. 13. pp. 66–77).

- Aria, M., & Cuccurullo, C. (2017). Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. Journal of Informetrics, 11(4), 959–975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2017.08.007

- Ascher, W. (1986). The evolution of the policy sciences: Understanding the rise and avoiding the fall. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 5(2), 365–373. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.4050050212

- Besio, C., du Gay, P., & Serrano Velarde, K. (2020). Disappearing organization? Reshaping the sociology of organizations. Current Sociology, 68(4), 411–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392120907613

- Brewer, G. D. (1999). The challenges of Interdisciplinarity. Policy Sciences, 32(4), 327–337. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004706019826

- Brooks, A. C. (2000). Is there a dark side to government support for nonprofits? Public Administration Review, 60(3), 211–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-3352.00081

- Brudney, J. L., & Durden, T. K. (1993). Twenty years of the journal of voluntary action Research/Nonprofit and voluntary sector quarterly: An assessment of past trends and future directions. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 22(3), 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764093223004

- Brudney, J. L., & Yoon, N. (2021). Don’t you want my help? Volunteer involvement and management in local government. The American Review of Public Administration, 51(5), 331–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/02750740211002343

- Bushouse, B. K., & Sowa, J. E. (2012). Producing knowledge for practice: Assessing NVSQ 2000–2010. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(3), 497–513. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764011422116

- Bushouse, B. K., Witkowski, G. R., & Abramson, A. J. (2023). A history of ARNOVA at fifty. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 52(1_suppl), 29S–67S. https://doi.org/10.1177/08997640221138262

- Chaudhuri, A. (2016). Policy studies, policymaking, and knowledge-driven governance. Economic and Political Weekly, 51(23), 59–68.

- Chavesc, M., Stephens, L., & Galaskiewicz, J. (2004). Does government funding suppress nonprofits’ political activity? American Sociological Review, 69(2), 292–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240406900207

- Clarivate. (2021). Web of science journal evaluation process and selection criteria. Web of Science Group. https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/journal-evaluation-process-and-selection-criteria/

- Clary, E. G., & Snyder, M. (1999). The motivations to volunteer: Theoretical and practical considerations. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8(5), 156–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00037

- Corley, E. A., & Sabharwal, M. (2010). Scholarly collaboration and productivity patterns in public administration: Analysing recent trends. Public Administration, 88(3), 627–648. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2010.01830.x.

- Coule, T. M., Dodge, J., & Eikenberry, A. M. (2020). Toward a typology of critical nonprofit studies: A literature review. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 51(3), 478–506. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764020919807

- Cyert, R. M. (1988). The place of nonprofit management programs in higher education. In M. O’Neill, & D. R. Young (Eds.), Educating Managers of Nonprofit Organizations (pp. 33–50). Praeger Publishers.

- Denhardt, R. B. (1981). Toward a critical theory of public organization. Public Administration Review, 41(6), 628–635. https://doi.org/10.2307/975738

- Evans, M. D. (2022). Nonprofit journals publication patterns: Visibility or invisibility of gender? VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-022-00470-x

- Farazmand, A. (2012). The future of public administration: Challenges and opportunities—A critical perspective. Administration & Society, 44(4), 487–517. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399712452658

- Goodin, R. E., & Klingemann, H.-D. (1998). A new handbook of political science. Oxford University Press.

- Goodnow, F. J. (1900). Politics and administration: A study in government. Macmillan.

- Goyal, N. (2017). A “review” of policy sciences: Bibliometric analysis of authors, references, and topics during 1970–2017. Policy Sciences, 50(4), 527–537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-017-9300-6

- Guy, M. E. (2003). Ties that bind: The link between public administration and political science. The Journal of Politics, 65(3), 641–655. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2508.00205

- Hafer, J. A. (2016). Public administration’s identity crisis and the emerging approach that may alleviate it. Hatfield Graduate Journal of Public Affairs, 1(1), 6.

- Handy, F., & Srinivasan, N. (2004). Valuing volunteers: An economic evaluation of the net benefits of hospital volunteers. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 33(1), 28–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764003260961

- Hood, C. (1991). A public management for all seasons? Public Administration, 69(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.1991.tb00779.x

- Jackson, S. K., Guerrero, S., & Appe, S. (2014). The state of nonprofit and philanthropic studies doctoral education. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 43(5), 795–811. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764014549056

- Kang, C. H., Baek, Y. M., & Kim, E. H.-J. (2021). Half a century of NVSQ: Thematic stability across years and editors. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 51(3), 658–679. https://doi.org/10.1177/08997640211017676

- Kim, Y. (2021). Searching for newness in management paradigms: An analysis of intellectual history in U.S. public administration. The American Review of Public Administration, 51(2), 79–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074020956678

- King, B. G. (2017). The relevance of organizational sociology. Contemporary Sociology, 46(2), 131–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094306117692563

- Kuhn, T. (1970). The nature of scientific revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago, 197.

- Kumar, S., Pandey, N., & Haldar, A. (2020). Twenty years of Public Management Review (PMR): A bibliometric overview. Public Management Review, 22(12), 1876–1896. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1721122

- Larsen, P., & Von Ins, M. (2010). The rate of growth in scientific publication and the decline in coverage provided by science citation index. Scientometrics, 84(3), 575–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-010-0202-z

- LePere-Schloop, M., & Nesbit, R. (2022). The nexus of public administration, public policy, and nonprofit studies: An empirical mapping of research topics and knowledge integration. Public Administration Review, 83(3), 486–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13587

- LePere-Schloop, M., & Nesbit, R. (2023). Disciplinary contributions to nonprofit studies: A 20-year empirical mapping of journals publishing Nonprofit research and journal citations by nonprofit scholars. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 52(1_suppl), 68S–101S. https://doi.org/10.1177/08997640221119728

- Lu, J., & Zhao, J. (2019). Does government funding make nonprofits administratively inefficient? Revisiting the link. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 48(6), 1143–1161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764019859435

- Ma, J., & Konrath, S. (2018). A century of nonprofit studies: Scaling the knowledge of the field. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 29(6), 1139–1158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-018-00057-5

- Michels, C., & Schmoch, U. (2012). The growth of science and database coverage. Scientometrics, 93(3), 831–846. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-012-0732-7

- Mirabella, R. M. (2007). University-based educational programs in nonprofit management and philanthropic studies: A 10-year review and projections of future trends. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 36(4_suppl), 11S–27S. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764007305051

- Mirabella, R. M., Hoffman, T., Teo, T. K., & McDonald, M. (2019). The evolution of nonprofit management and philanthropic studies in the United States: Are we now a disciplinary field? Journal of Nonprofit Education and Leadership, 9(1). https://search.proquest.com/openview/859c4bd0d529a0489b7e40a128859395/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2037378&casa_token=3dhkWc2cmkgAAAAA:0RoA-vsp076KuEYeo5BYIjcbhhKIaH_uXc4IWRprTT8L0SBKbdbooxr0VAbG_d_G9S0YQd6lDQ

- Mirabella, R. M., & Wish, N. B. (2000). The “Best place” debate: A comparison of graduate education programs for nonprofit managers. Public Administration Review, 60(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-3352.00082

- Morillo, F., Bordons, M., & Gómez, I. (2003). Interdisciplinarity in science: A tentative typology of disciplines and research areas. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 54(13), 1237–1249. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.10326

- Moya-Anegón, F., Vargas-Quesada, B., Chinchilla-Rodríguez, Z., Corera-Álvarez, E., Munoz-Fernández, F. J., & Herrero-Solana, V. (2007). Visualizing the marrow of science. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(14), 2167–2179. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20683

- Moya-Anegón, F., Vargas-Quesada, B., Herrero-Solana, V., Chinchilla-Rodríguez, Z., Corera-Álvarez, E., & Munoz-Fernández, F. J. (2004). A new technique for building maps of large scientific domains based on the cocitation of classes and categories. Scientometrics, 61(1), 129–145. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SCIE.0000037368.31217.34

- Musick, M. A., & Wilson, J. (2007). Volunteers: A social profile. Indiana University Press.

- Nafi’ah, B. A., Roziqin, A., Suhermanto, D. F., & Fajrina, A. N. (2021). The policy studies journal: A bibliometric and mapping study from 2015–2020. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal), 5881. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/5881

- National Academies. (2005). Facilitating interdisciplinary research. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11153

- Nesbit, R., & Brudney, J. L. (2013). Projections and policies for volunteer programs: The implications of the serve America act for volunteer diversity and management. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 24(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21080

- Nesbit, R., Moulton, S., Robinson, S., Smith, C., DeHart-Davis, L., Feeney, M. K., Gazley, B., & Hou, Y. (2011). Wrestling with intellectual diversity in public administration: Avoiding disconnectedness and fragmentation while seeking rigor, depth, and relevance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 21(Supplement 1), i13–i28. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muq062

- Ni, C., Sugimoto, C. R., & Robbin, A. (2017). Examining the evolution of the field of public administration through a bibliometric analysis of public administration review. Public Administration Review, 77(4), 496–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12737

- O’Neill, M., & Young, D. R. (Eds.). (1988). Educating managers of Nonprofit organizations. Praeger Publishers.

- Osborne, S. P. (2006). The new public governance? 1. Taylor & Francis.

- Ostrom, V. (2008). The intellectual crisis in American public administration. University of Alabama Press.

- Porter, A. L., Roessner, J. D., Cohen, A. S., & Perreault, M. (2006). Interdisciplinary research: Meaning, metrics and nurture. Research Evaluation, 15(3), 187–196. https://doi.org/10.3152/147154406781775841

- R Core Team. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing [ Computer software]. http://www.R-project.org/

- Raadschelders, J. C. N., & Lee, K.-H. (2011). Trends in the study of public administration: Empirical and qualitative observations from public administration review, 2000–2009. Public Administration Review, 71(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02303.x

- Rafols, I., & Meyer, M. (2010). Diversity and network coherence as indicators of interdisciplinarity: Case studies in bionanoscience. Scientometrics, 82(2), 263–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-009-0041-y

- Rosenbloom, D. (2008). The Politics–administration dichotomy in U.S. Historical context. Public Administration Review, 68(1), 57–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00836.x

- Salamon, L. M. (1987). Of market failure, voluntary failure, and third-party government: Toward a theory of government-nonprofit relations in the modern welfare state. Journal of Voluntary Action Research, 16(1–2), 29–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/089976408701600104

- Salamon, L. M. (1998). Nonprofit management education: A field whose time has passed? In M. O’Neill & K. Fletcher (Eds.), Nonprofit management Education: U.S. And world perspectives (pp. 137–145). Greenwood Publishing Company.

- Schwartz-Shea, P., & Yanow, D. (2013). Interpretive research design: Concepts and processes. Routledge.

- Science-Metrix. (2021). News. https://science-metrix.com/?q=en/news&page=5

- Shier, M. L., & Handy, F. (2014). Research trends in nonprofit graduate studies: A growing interdisciplinary field. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 43(5), 812–831. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764014548279

- Smith, D. H. (2003). A history of ARNOVA. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 32(3), 458–472. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764003254841

- Soskis, B. (2020). A history of associational life and the Nonprofit sector in the United States. In W. W. Powell & P. Bromley (Eds.), The nonprofit sector: A research handbook (3rd ed. pp. 23–80). Stanford University Press.

- Tahmasebi, R., & Musavi, S. M. M. (2011). Politics-administration dichotomy: A century debate. Administration & Public Management Review, 17, 130–143.

- Testa, J. (2011). The globalization of web of science: 2005–2010. Thomson Reuters. http://wokinfo.com/media/pdf/globalwos-essay

- Van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2010). Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics, 84(2), 523–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3

- van Raan, A. F. J., & van Leeuwen, T. N. (2002). Assessment of the scientific basis of interdisciplinary, applied research: Application of bibliometric methods in nutrition and food research. Research Policy, 31(4), 611–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(01)00129-9

- Vigoda-Gadot, E. (2002). Public administration: An interdisciplinary critical analysis. CRC Press.

- Vogel, R. (2014). What happened to the public organization? A bibliometric analysis of public administration and organization studies. The American Review of Public Administration, 44(4), 383–408. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074012470867

- Vogel, R., & Hattke, F. (2022). A century of public administration: Traveling through time and topics. Public Administration, 100(1), 17–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12831

- Wessels, J. S. (2023). Meaningful knowledge about public administration: Epistemological and methodological antecedents. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 45(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/10841806.2022.2158633

- Whicker, M. L., Olshfski, D., & Strickland, R. A. (1993). The troublesome cleft: Public administration and political science. Public Administration Review, 53(6), 531–541. https://doi.org/10.2307/977363

- White, L. D. (1948). Introduction to the study of public administration. Macmillan

- Wickham, H. (2019). R package “stringr” (1.4.0) [ Computer software]. http://stringr.tidyverse.org, https://github.com/tidyverse/stringr

- Wickham, H. (2020). R package “ggplot2” (3.3.3) [ Computer software]. https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org, https://github.com/tidyverse/ggplot2

- Wilson, J., & Musick, M. (1997). Who cares? Toward an integrated theory of volunteer work. American Sociological Review, 62(5), 694–713. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657355

- Wilson, W. (1887). The study of administration. Political Science Quarterly, 2(2), 197–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/2139277

- Wright, B. E. (2011). Public administration as an interdisciplinary field: Assessing its relationship with the fields of Law, management, and political science. Public Administration Review, 71(1), 96–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02310.x

- Wright, B. E., Manigault, L. J., & Black, T. R. (2004). Quantitative research measurement in public administration: An assessment of journal publications. Administration & Society, 35(6), 747–764. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399703257266

- Young, D. (1999). Nonprofit management studies in the United States: Current developments and future prospects. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 5(1), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.1999.12022049

- Zalmanovitch, Y. (2014). Don’t reinvent the wheel: The search for an identity for public administration. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 80(4), 808–826. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852314533456

- Zuo, Z., Qian, H., & Zhao, K. (2019). Understanding the field of public affairs through the lens of ranked Ph. D. programs in the United States. Policy Studies Journal, 47(S1), S159–S180. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12322

Appendix

Teaching Note

Target Audience: Doctoral students in public affairs or related field.

Learning Objectives

Students will explain interdisciplinary knowledge integration and why it is important

Students will describe the mix of disciplines contributing to public affairs scholarship and the configuration of disciplines producing scholarship across fifteen key topical areas

Students will evaluate the implications this research has for the future of public affairs scholarship

Teaching Plan

The instructor can assign this article as pre-reading for class or share the accompanying slides with the primary findings as part of a course lecture.

The instructor can lead the class in a discussion of the article. The discussion can focus on three areas—basic understanding of the article, the larger implications of the results, and application of the article to their own research/work.

Discussion Questions (to assess understanding of the article):

What is knowledge integration? Why is knowledge integration helpful or important?

See slides 2-5

“Occurs when knowledge (e.g. theories, concepts, methods, ideas) from two research fields are combined in meaningful ways.”

“Valuable because leads to greater innovation which advances science faster and can be applied to solve complex problems.”

What is citation network coherence indicating? What is cited journal diversity indicating? Why is it important to consider both citation network coherence and cited journal diversity when assessing interdisciplinary knowledge integration?

When authors cite the same work, they are drawing on a foundation of shared knowledge. Citation network coherence is a way to measure that shared foundation of knowledge.

When authors cite journals from different disciplines, they are drawing on a wider range of perspectives, insights, and understandings.

Interdisciplinary knowledge integration is about bringing together different knowledge (cited journal diversity) in a coherent and meaningful way (citation network coherence).

Which field (PA, PP, or Nonprofit) has the most interdisciplinary knowledge integration? Which one has the least? How do the authors explain these results?

See slide 15

Nonprofit studies has above average citation network coherence and cited journal diversity, and higher interdisciplinary knowledge integration that PA and PP.

PA has below average citation network coherence and cited journal diversity, and lower interdisciplinary knowledge integration that PP and Nonprofit.

Nonprofit was more multidisciplinary from its inception, which possibly explains why it has more interdisciplinary knowledge integration

Which disciplines are most cited in public affairs scholarship? How does this vary by field?

See slides 6-14

Business and Management, Political Science, and Economics are the most cited disciplines.

Articles in Nonprofit journals often cite Business and Management and Psychology journals, PA journals often cite Political Science and Business and Management journals, PP journals frequently cite Political Science and Economic journals.

Discussion Questions (to explore implications of the article’s results):

How is knowledge integration different in a multidisciplinary field like public affairs compared to a traditional discipline?

What are the potential barriers to interdisciplinary knowledge integration, particularly in a multidisciplinary field?

How might the disciplinary training and background of a scholar affect what kind of research questions, methods, and epistemologies they value? How might this affect the way they evaluate research with questions, methods, and epistemologies that are unfamiliar to their discipline?

How can a multidisciplinary field like pubic affairs help break down barriers to interdisciplinary knowledge integration?