ABSTRACT

Scholars observe an increased involvement of citizens in green space governance. This paper focuses on green self-governance, in which citizens play a major role in realizing, protecting and/or managing green space. While existing research on green self-governance focuses mostly on specific cases, we aim to contribute towards a large overview via an inventory of 264 green self-governance practices across The Netherlands. With this, we discuss the relevance of green self-governance for nature conservation and its relationship with authorities. In our analysis, we show that green self-governance practices are very diverse: they pursue a wide variety of physical and social objectives; employ a multitude of physical and political activities; involve different actors besides citizens; mobilize different internal and external funding sources; and are active within and outside of protected areas. While green self-governance can contribute towards protection and management of green space and towards social values, we highlight that this contribution is mostly of a local relevance. Most practices are small scale and objectives do not always match those of authorities. Although we speak of self-governance, authorities play an important role in many practices, for example, as financial donor, landowner or regulatory authority. In this, self-governance is often not completely ‘self’.

Abbreviations: PAA: Policy Arrangement Approach; NNN: National Nature Network; N2000: Natura 2000; NCOs: Nature Conservation Organizations; NGOs: Non-governmental organizations

1. Introduction

1.1. Green self-governance

Across the EU, the involvement of citizens in governance and management of green space has significantly increased over the last decades. Scholars across Europe have observed the involvement of citizens in the governance of urban green (e.g. Fors, Molin, Murphy, & Konijnendijk van den Bosch, Citation2015; Van der Jagt, Elands, Ambrose-Oji, Gerőházi, & Steen Møller, Citation2016), rural landscapes (e.g. Derkzen & Bock, Citation2009; Mattijssen, Behagel & Buijs, Citation2014) and protected nature reserves (e.g. Apostolopoulou et al., Citation2014; Beunen & de Vries, Citation2011). This growing involvement of citizens in green space governance can be seen in the light of a broader shift from government to governance. In this shift, traditional centralized decision-making has increasingly been complemented by governance processes involving a wide range of involved actors (Goodwin, Citation1998; Rhodes, Citation1996; Stoker, Citation1998), blurring the boundaries between public and private sectors (Stoker, Citation1998). Non-government actors involved in governance include businesses and NGOs, but also citizen groups and individual citizens (Goodwin, Citation1998; Moro, Citation2012). Through forms of co-production or co-governance, these actors often work together for the realization of common benefits (Bovaird, Citation2007; Mitlin, Citation2008).

In recent years, scholars have observed more emphasis on self-governance (Arnouts, van der Zouwen, & Arts, Citation2012; Sørensen & Triantafillou, Citation2009). This shift assumes that private actors (citizens, businesses and NGOs) become increasingly autonomous in governance issues, whereas state actors play a more facilitating role. In literature, the term self-governanceFootnote1 is used to describe a wide variety of governance arrangements where private actors take their own initiative to autonomously act and pursue public or collective objectives. In green space governance, this manifests in many bottom-up initiatives (see e.g. Apostolopoulou et al., Citation2014; Lawrence & Ambrose-Oji, Citation2015; Van der Jagt et al., Citation2016). We talk about green self-governance to discuss bottom-up green space initiatives from citizens, people who are involved in green self-governance in a non-professional role.

1.2. Problem statement

Many authorities recognize a potential for citizens to positively contribute to the governance and management of public green (Perkins, Citation2010; Rosol, Citation2010). Regularly, authorities actively aim to involve citizens in the delivery or co-production of green space management through co-governance or through supporting self-governance (Smith, Pereira, Hull, & Konijnendijk van den Bosch, Citation2014; Van der Jagt et al., Citation2016; Van Melik & Van Der Krabben, Citation2016). However, the responsibility for safeguarding policy goals on, for example, the realization of Natura 2000 still rests with authorities (Beunen & de Vries, Citation2011). It is also still up for debate how bottom-up citizen initiatives link up to centralized ecological networks that are emphasized in EU-policy. For authorities, the relationship of green self-governance with green space policy and management is therefore a relevant point of discussion (Buijs, Mattijssen, & Elands, Citation2016. On different levels of scale, the objectives of authorities and citizens regarding public green space might differ from one another. It is an important inquiry how the activities of citizens concerning public green might contribute (or not) to co-production in the realization of policy aims (Ten Cate, Dirkx, Hinssen, van Koppen, & Vader, Citation2013).

Besides, current debates on the role of citizens in governance often imply a notion of ‘active citizenship’ (Moro, Citation2012; van Dam, Duineveld, & During, Citation2015). These citizens are not seen as passive subjects of policy, but as actively pursuing their interests. The wide range of citizen initiatives that can be found all over Europe (Teles, Citation2012) demonstrates that a shift or trend from ‘citizenship’ to ‘active citizenship’ (Hoskins & Mascherini, Citation2009) is not only visible in political discourse, but also in bottom-up practices. Yet, there are also critical views in this regard. First of all, several researchers highlight that the actual transfer of responsibilities and decision-making power from governmental to non-governmental actors is rather limited compared to rhetoric on governance (Apostolopoulou et al., Citation2014; Shore, Citation2011). Secondly, critical scholars connotate the term active citizenship with a decline in public services offered by the state, arguing that this had led to an ‘instrumentalization’ of citizens who are expected by authorities to take over tasks from the state (Raco & Imrie, Citation2000; Verhoeven & Tonkens, Citation2013). Thirdly, the term active citizenship is associated with the exclusion of non-active citizens (Milana, Citation2008), leading to democratic questions about equal representation (Thuessen, Citation2010). Given the above views and debates, it is important to understand the role of public authorities in relation to green self-governance. While literature on self-governance assumes a somewhat autonomous and independent character of citizen initiatives (Arnouts et al., Citation2012; Van Dam, Eshuis, & Aarts, Citation2009), it is an important inquiry how independent citizens really are; if and how they have a relationship with authorities; and what role authorities play in relation to green self-governance.

Finally, although the involvement of citizens in green space governance has been described and analysed in several papers, a clear overview of the phenomenon of green self-governance and what it entails is lacking. Empirical evidence is rather scattered and often strongly focused on individual cases. An example of such a study describes how citizens have established a foundation to manage and restore cultural landscape elements in a rural area (van Dam, Salverda, & During, Citation2014). While such case studies on green self-governance provide useful in-depth insights, the existing body of literature lacks a broader (quantitative) overview and assessment of the phenomenon of green self-governance as a whole. There is a lack of a more general insight into, for example, what citizens aim to achieve with green self-governance; what activities they undertake to reach their objectives; how citizens organize and finance themselves; and which other actors are involved in green self-governance.

1.3. Research aims and scope

This paper addresses the knowledge gaps identified in the above: the contribution of green self-governance to nature conservation; the relationships of citizens with authorities in the context of green self-governance; and the lack of systematic empirical evidence on the phenomenon of green self-governance. It specifically focuses on forms of green space governance in which citizens play a major role: so-called ‘green self-governance’. We define this as ‘a specific form of governance in which citizens play a major role in realizing, protecting and/or managing green public space’. This major role means that citizens have a capacity to act somewhat independently from external forces and have an important role in deciding objectives and employing activities to reach these.

By studying a wide range of practices of green self-governance, we aim to contribute to more generalized insights into the phenomenon of green self-governance and the above knowledge gaps. Although we discuss green self-governance in a wider setting, our fieldwork, for practical reasons, focuses on the Netherlands. Although the Dutch governance of green space has a long history of top-down steering (Buijs, Mattijssen, & Arts, Citation2014; Van Melik & Van Der Krabben, Citation2016), nature policy in the Netherlands has rapidly changed in recent years (Buijs et al., Citation2014). This includes a decentralization of responsibilities to regional authorities and large budget cuts on nature conservation, which have reduced funding for green space management (ibid.). Simultaneously, a bigger emphasis on the roles and responsibilities of citizens in green space management arose (ibid.). There is currently more focus on local ownership (Buijs, Mattijssen, & Kamphorst, Citation2013) and active citizenship (van Dam et al., Citation2015) in the green domain. This puts green self-governance in the spotlight of current policy debates about nature conservation in The Netherlands.

The following research questions have been formulated:

To what extent do green self-governance practices contribute to the governance of green space?

To what extent do examples of green self-governance match debates about the changing relationship between governments and citizens?

2. Analytical framework for green self-governance practices

We treat individual initiatives of green self-governance as specific (local) practices. A group of citizens might organize themselves to create and manage green space in their neighbourhood in order to improve the amenity and social cohesion in the area; others might protest against the development of infrastructure in a protected reserve; and others might manage green cultural elements in the landscape and organize excursions for school children with the objective of preserving local cultural history. Such practices consist of an organized set of activities (Schatzki, Citation2002) and are linked to a certain vocabulary which provides a meaning to the practice (Røpke, Citation2009). A practice consists of multiple elements (such as a specific discourse, procedure or tool), but should be seen as a single entity (Reckwitz, Citation2002; Shove, Pantzar, & Watson, Citation2012).

In practices, there is room for agency and actors have an objective to act (Schatzki, Citation2010), but practices are also influenced by rules and resources (Giddens, Citation1984). In recognition of this, we employ an analytical framework influenced by the Policy Arrangement Approach (PAA, Arts & Leroy, Citation2006) in order to scrutinize relevant elements of green self-governance practices. The PAA has recently been employed in a number of studies discussing green self-governance (e.g. Buizer et al., Citation2015; Lawrence, De Vreese, Johnston, Konijnendijk van den Bosch & Sanesi, Citation2013; Van der Jagt et al., Citation2016). Building upon structuration theory (Giddens, Citation1984), this approach provides an analytical framework which is applicable in this field (Ayana, Vandenabeele, & Arts, Citation2015), while enabling the study of both agency and structure in governance processes (Arts & Leroy, Citation2006).

The PAA distinguishes four analytical dimensions that can be employed to study governance: discourse, actors, rules, and resources (Arts & Leroy, Citation2006, Van Tatenhove, Arts, & Leroy, Citation2000). However, while social reality is often understood as being constituted by human activity within the structure-agency duality (Schatzki, Citation2012), the PAA - originally developed to study policy arrangements, rather than governance practices - lacks an explicit focus on what actors actually do in the field in order to achieve their aims (Ayana et al., Citation2015). This research requires a more explicit focus on human activity in order to understand specific practices of green self-governance and their functioning. To explicitly address this, we add a fifth dimension to our analytical framework: activities.

Activities, as part of practices (Schatzki, Citation2012), are the actions undertaken by involved actors in order to realize the intended aims of green self-governance. The dimension of discourse encompasses interpretative schemes which are used by actors to give meaning to physical and social realities (Hajer, Citation1995). This includes an orientation towards ends (Schatzki, Citation1997) - an objective that motivates people to act. The actor-dimension refers to the individuals and organizations involved in governance. Rules determine the opportunities and barriers for actors to act in a governance process (Arts, Leroy, & van Tatenhove, Citation2006), while resources encompass attributes, skills, financial- and material resources that can be mobilized to achieve certain outcomes (ibid.).

3. Methodology

3.1. Data collection and analysis

In order to collect our data, we conducted a large inventory of green self-governance initiatives within the Netherlands. Multiple sources of data were used to collect and describe a large number of green self-governance initiatives: (i) existing scientific and non-scientific literature; (ii) contacts with experts in the field; (iii) an extensive web search with the use of several keywords; and (iv) a call on the internet and on social media, in which people were asked to inform the authors about green self-governance practices. In total, we collected 264 initiatives of green self-governance in this way.

The individual analysis of these initiatives consisted of two steps. First, all initiatives have been qualitatively described on their objectives, activities, involved actors, etc. In a second, quantitative step, categories were identified against which the initiatives were assessed (e.g. to ‘score’ which types of actors were actively involved in the initiatives). After completion of this individual analysis, an overall analysis was conducted in which the initiatives have been compared to each other, for example, to look at the percentage of initiatives receiving subsidies. With the use of cross-tabulations in SPSS, we have also scrutinized the relationships between different characteristics. We used a confidence interval of p = 0,05 to look for significant relationships and used Cramer’s V as a measure of association.

As a final step, we performed a further qualitative scrutiny of a subset of 50 initiatives, which includes an interview with a person directly involved in the initiative. This qualitative study was conducted in order to validate our research findings and to put some more flesh on the bones of our analysis (the results of this study are described in Mattijssen, Buijs, & Elands, Citationin press).

3.2. Criteria of analysis

summarizes the characteristics on the basis of which practices of green self-governance have been analysed. First of all, we describe the activities that citizens employ to reach their objectives. We see the objectives as an important form of discourse: they are strategically formulated, develop in social processes and are shared by citizens involved in an initiative. As part of our discourse analysis, we also look at what type of green space groups aim to realize or protect. In our analysis of actors, we look at the number of citizens involved, as well as the extent to which other actors are involved. For the dimension of rules, we identify whether the areas the groups were active in or focused on had a formal protected status under the Dutch National Nature Network (NNN) and/or under the European Natura 2000 network (N2000). For the dimension of resources, we study how groups are funded. A full list of the assessment categories (which we developed during the analysis of the inventory) can be found in Appendix .

Table 1. Criteria of analysis.

3.3. Representativeness and scope

The representativeness of this study is unclear. We cannot assess how our sample relates to the total population of green self-governance practices in the Netherlands as this population remains unknown. We consider it likely that our inventory is slightly biased towards well-documented and visible initiatives (see also Uitermark, Citation2015), as smaller and less visible initiatives are more difficult to find in our data sources. In this, our research is not unlike questionnaires with a non-response bias, where those who respond often do not fully match certain characteristics of the wider population (Søgaard, Selmer, Bjertness, & Thelle, Citation2004).

Given the nature and size of our sample, we do believe that findings can be generalized in order to contribute to debates (see also Heesen, Citation2014). The data which we collected is higher in number and broader in scope than of existing research so far. Even without presenting a statistical inference to a total population, the analysis which we present still offers a valuable contribution to debates (see also Grayson, Robins, & Pattison, Citation1997). After all, our research greatly improves available data on green self-governance. Considering the large size of our sample, it is unlikely that our findings are way off (Heesen, Citation2014). Even so, there are implications due to the uncertainties which we have pointed out. The figures which we present in our analysis should therefore be seen as an indication and treated with some margin of uncertainty.

4. Analysis

Our analysis of 264 practices of green self-governance in the Netherlands shows that there is a very large diversity among these initiatives. Foundation ‘neighbour creates nature’ collects money to purchase agricultural lands and converts them into publicly accessible nature. Volunteers in ‘butterfly garden Lewenborg’ have developed a brownfield into a flower-garden that is attractive to insects and especially to butterflies. The inhabitants from the Houtdreef street in the town of Varsseveld are developing a green infrastructure in their neighbourhood. The association ‘save De Kaloot’ has successfully protested against industrial development of a seaport on a historical beach area. Volunteers of nature association ‘The Meadow Thistle’ work in the landscape to conserve nature, landscape elements and the historical view of the area.

The 264 self-governance practices in our study highlight that green self-governance can be found almost everywhere in The Netherlands, in both rural and urban contexts. Some groups involve green spaces smaller than 50 m2 while others are concerned with areas spanning more than 100 hectares. While most do not manage such large areas, green self-governance is by far not always ‘street level’ in its scope.

Green self-governance is not just a recent, short-lived phenomenon either: about half of the groups had existed for more than 7 years at the time of study and around 25% has been established before 2000. Even so, some groups have ended their activities or are only temporary in scope while others have developed and often broadened over time. Green self-governance is very much a dynamic phenomenon as self-governance practices develop over time. Although these dynamics are not extensively covered in this paper, this is an important point to keep in mind.

4.1. Activities

Many groups in our study were engaged in some form of physical activity to protect or enhance green areas (). Such activities focused on management and maintenance of existing green, such as cleaning of waste, pollarding of willows or cutting of hedges; and on developing new green by, for example, planting trees or creating new green infrastructure through digging ditches.

Table 2. Types of activities of green self-governance (N = 259).

Half of the groups actively tried to influence spatial policy or management. This was done through protest activities such as collecting signatures, going to court, or organizing protest events (25%). Such protest was often aimed at policy plans by authorities and sometimes towards management plans or practices by nature conservation organizations. Yet, political activities related to deliberation and cooperation were more common (31%). This can include deliberation with municipalities, participation in spatial development processes, or an interactive development of plans in cooperation with other actors.

Activities related to education involved the organization of excursions or lectures, but also focused on facilitating people (often children) to discover nature and green space. Monitoring and research included inventories or censuses of the presence of certain species and mapping factors such as water levels. Such activities were rarely conducted in isolation. Only 4% of all groups was neither engaged in physical nor political activities, while 25% was engaged in both physical and political activities.

4.2. Discourse

In the narratives on the objectives of citizen groups, we find three broad categories: physical, social and economic objectives (), comprising several subcategories of objectives. Typical for most groups is the combination of multiple objectives, with 35% aiming to realize both social and physical objectives.

Table 3. Objectives of green self-governance initiatives (N = 248).

Almost all examples of green self-governance in our study pursued physical objectives aiming at tangible effects in the field. This often included the protection of nature in a broad sense, for example, protecting specific species or biodiversity in general, or creating new green spaces. Especially in rural areas, focus also was on cultural landscapes and cultural history, for example, maintaining hedges and pollard willows. Physical objectives also related to improvements in the field to facilitate (recreational) green for human use, including the improvement of scenery; creation of space for activities; provision of access to green or nature; and improvement of the direct living environment.

Next to physical objectives, many citizens groups also focused on social objectives. Most prominently this related to enhancing environmental awareness, a category of objectives which often corresponds with (educational) activities aimed at children. Social cohesion objectives were mostly mentioned in an urban context, aiming to bring people into contact with one another, or offering opportunities for underprivileged groups to enhance their social network. Economic objectives such as the provision of employment or of marketable services or products were rarely mentioned.

When looking at narratives and pictures concerning the type of green space on which initiatives focus, the largest category encompasses parks, public gardens and urban green, highlighting that green self-governance is not only focusing on ‘wild’ nature (). However, there are also many groups who focused on more ‘natural’ environments or on specific (families of) species, such as meadow birds or butterflies.

Table 4. Types of green space involved in green self-governance (N = 261).

4.3. Actors

The total number of citizens which was regularly involved in the activities of the citizens groups ranged from 2 to around 200, although usually below 50. These active volunteers were often supported by a broader group of people who incidentally participated or financially supported their activities. Still, our interviews show that many initiatives of green self-governance worry about continuing to bind (younger) volunteers towards the future, or are quite dependant om a small core of volunteers.

Although we speak about green self-governance, most initiatives involved professional actors such as municipalities, NGOs and businesses in the organization and carrying out of activities ().

Table 5. Actors actively involved in green self-governance (N = 218).

Many initiatives of green self-governance, at some point in time, have come into contact with authorities – who often became actively involved. Municipalities were by far the most intensively involved authorities: they supported initiatives in kind by aiding in management tasks, provided materials and advice, or provided land and/or accommodation. As municipalities are frequently also landowners, and because of formal rules or procedures, this involvement was often legally required to legitimize the activities of citizens.

The involvement of business actors often concern cooperation with farmers, for example in agricultural nature conservation, grazing of nature areas by cattle and hiking routes on farmland. There are also examples in which citizens, together with enterprises, such as desludging companies or construction companies, worked on the development of nature.

Our analysis also highlighted an involvement of a broad range of NGOs in many initiatives. This included environmental NGOs, but also NGOs not directly aimed at green space such as neighbourhood associations; sport clubs; health facilities; primary schools; historical societies; and many others. The involvement of large private and semi-public Nature Conservation Organizations (NCOs) was mostly visible in relatively large scale initiatives with a focus on nature protection. In these cases, cooperation was often rather intense. In urban areas or within city limits, involvement of NCOs in green self-governance was rare.

4.4. Rules

Although many groups in our study aimed to contribute towards the protection of nature, the majority (61%) was not active in formally protected nature reserves, either the Dutch Network of Protected Areas (NNN) or the overlapping but smaller European Network of Natura 2000 ().

Table 6. Percentage of self-governance initiatives active within protected areas (N = 214).

Although we did not categorize this at first, we observed several mechanisms of formalization during our analysis of the subset of 50 initiatives. Many initiatives had become a legal entity, usually a foundation or association, which respondents considered as necessary for the setting in which their groups operated (e.g. to be applicable for receiving subsidies). We also observed that, in order to formally permit citizen activities by authorities, formal arrangements were agreed upon. These include contractual agreements with involved parties, such as on the management or the lease of areas, or the design of a specific policy to (re)define the function of an area. Even so, we observed no formalization whatsoever in other groups.

4.5. Resources

The citizen groups often mobilized multiple sources of funding to cover their costs (). Annual budgets ranged from almost zero to over €50.000, and were generally bigger for groups physically active in relatively large areas.

Table 7. Sources of funding (N = 165).

Subsidies formed the most prominent source of income, usually provided by local or regional authorities. Especially in smaller initiatives, an investment of own financial resources by participating citizens was often visible. Some initiatives derived part of their resources from revenues generated by delivering services or products. These revenues usually provided a (small) supplemental form of income and were rarely an exclusive source of funding.

Even though there were often multiple sources of income, many of the people we interviewed worried about the long-term financial viability of their groups or stated that their income had declined over the years. Frequently, authorities were seen as an ‘unreliable’ partner in this respect, as the future of subsidies is often uncertain.

4.6. Relationships and cross-calculations

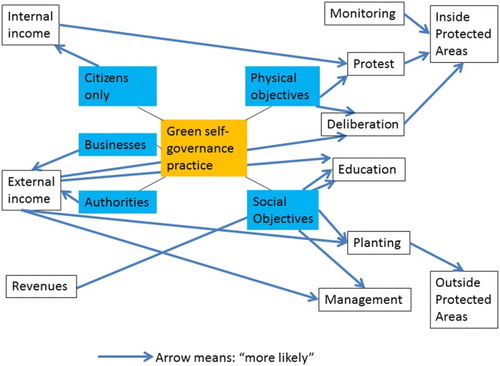

In order to gain more insight into the relevance of green self-governance for the governance of green space, we have looked at correlations between the objectives of green self-governance practices and the activities employed to reach these (). This table highlights several significant correlations. Interestingly, groups pursuing physical objectives are more likely to employ political activities – which are less likely to be employed for the realization of social objectives. Conversely, physical activities and education are more likely to be employed for the accomplishment of social objectives.

Table 8. Relation between objectives and activities.

Relevant for green space policy around protected areas is the type of activities that citizens employ within such reserves (). As this table shows, the protected status of an area is strongly associated with the type of activities that are employed. Citizen groups that are active within protected areas are less likely to engage in planting and the realization of new green, possibly because of regulations concerning this protected status. They are much more likely to engage in monitoring and political activities (including protest) within protected areas.

Table 9. Relation between activities and protected status.

The relationship between the involved actors in green self-governance and the resources that were mobilized is particularly relevant for discussions around the organization of governance and the changing relationships between involved actors - and what this means in a financial way (). This table shows that the type of income is highly associated with the involvement of specific actors. Perhaps not surprisingly, initiatives involving only citizens are much more dependent on internal income and less likely to have an external income. Initiatives with an active role for authorities and NGOs are more likely to receive external income. However, the involvement of both authorities and businesses decreases the likelihood of an internal income and thus seems to increase a reliance on external sources of funding.

Table 10. Relation between involved actors and resources.

We observed a number of significant correlations between the involved actors and the activities that were employed (). A positive correlation exists between deliberation activities and the involvement of authorities or NGOs, showing that such activities often successfully engage other actors in cooperation. The involvement of authorities and business actors is less likely to go together with protest activities, which is not a surprise given that protest activities were often aimed at either authorities or businesses. Initiatives involving authorities and NCOs are more likely to engage in management activities.

Table 11. Relation between involved actors and activities.

Also relevant in this context is the relationship between the type of activities in which groups are engaged and the sources of income which they collected (). In this, some correlations exists, especially when there is an external income. Initiatives engaged in management, planting, education and deliberation are more likely to have an external income. Initiatives engaged in protest are less likely to have an external income, but more likely to have an internal income.

Table 12. Relation between resources and activities.

– highlight important correlations between characteristics of green self-governance practices. This does not allow us to draw conclusions about causality, but it does show that, as the PAA suggests, it is likely that different dimensions of green self-governance have an influence on each other. This can have important implications for, for example, the governance of protected areas and the funding of green self-governance. In , we graphically show some of these ‘likely pathways’, highlighting that green self-governance practices with certain characteristics are more likely to show certain other characteristics.

5. Discussion

5.1. The scope of green self-governance

While existing case study research on green self-governance highlights important lessons, the systematic overview which we present in this paper is the first of its kind in English literature. With this, we contribute to a better generalized insight into the phenomenon of green self-governance and what it looks like in practice. Although we cannot make solid claims about the representativeness of our study, our research greatly improves available data on green self-governance and provides a better generalizing view than existing research.

Our data highlights several important characteristics of green self-governance practices. We illustrate that green self-governance involves a wide range of activities beyond the physical management of green space. Groups engaged in green self-governance often pursue multiple objectives and employ multiple activities to reach these, regularly combining both physical and social objectives and physical and political activities. We also show that many green self-governance practices involve a wide range of actors beyond citizens, often with an important role for authorities. Furthermore, we highlight several important funding mechanisms. The diversity highlighted in this study is in line with more general observations in governance debates, where it is often highlighted that current-day governance can be found in many different forms (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2001; Van Assche, Beunen, & Duineveld, Citation2014).

5.2. The green in green self-governance

Our analysis shows that citizens can contribute to realizing, managing and protecting green public space in many ways. In this light, it is important to discuss how citizens are involved in green self-governance and what implications this might have for authorities and their policies (Ten Cate et al., Citation2013). The objectives of green self-governance practices are an important indicator of their possible relevance for co-production of policy aims. These objectives highlight that almost all groups aim to realize physical effects, often related to nature protection and in rural areas also related to cultural landscapes. For authorities, this might offer opportunities regarding their policy. Our findings on the importance of social objectives link up with findings by Van der Jagt et al. (Citation2016), who identify the integration of social objectives and green space management as an important trend. Via green self-governance, there might thus also be possibilities for co-production of social policy objectives.

However, as van Dam et al. (Citation2015) and Buijs et al., (Citation2013) also show, we have to be aware that authorities and citizens might have conflicting objectives. Our findings underline that citizens might articulate different visions than authorities or even protest against certain policies, which regularly happened. For example, there can be tensions between objectives on realizing recreational facilities and protecting biodiversity or when citizens and authorities prefer different types of green space. Several scholars in Europe have highlighted disconnections between the goals of authorities and citizens in nature conservation (Apostolopoulou et al., Citation2014; Buijs, Citation2009; Paloniemi et al., Citation2015). Policy makers should therefore not assume that citizens and authorities will always have similar aims when discussing the potential of self-governance to contribute to the realization of nature conservation policy.

Considering the small scale of many initiatives, we should also be somewhat critical about the total contribution of green self-governance to the protection of green space at this point in time. Although certainly substantive, all initiatives of green self-governance will currently not add up to anywhere near the 700.000 hectares of nature managed by large NCOs and authorities in the Netherlands. Whilst practices of green self-governance have shown to realize significant effects on the local scale (Lawrence & Ambrose-Oji, Citation2015; Mattijssen et al., Citationin press), we should therefore not overestimate their contributions towards (inter)national policy goals and ecological networks. When we talk about co-production of policy objectives, we should also be aware that the large majority of the initiatives is not physically active within protected areas, which have a central place in nature conservation.

Following the above, we feel that policy makers should be careful about what they expect from citizens and their potential to contribute to the protection and management of green space. While policy discourses might place a strong emphasis on active citizenship in green space, authorities and large NCOs still retain an important position in nature conservation and green space protection. Citizens certainly play a relevant role and potentially realize important effects (Mattijssen et al., Citationin press). However, they generally do so on a different level of scale and their objectives will not always match with policy. In the current context of budget cuts and the withdrawing state in the Netherlands and many EU-countries, we want to stress that the contribution of citizens should be seen as additive towards existing public policy and management (Bovaird & Löffler, Citation2013). Citizens can certainly provide a valuable contribution next to traditional management. However, their activities should not be seen as a replacement for this, as public authorities retain an important role.

In this, the added value of self-governance for green space protection should mostly be seen on the local scale. On a national scale, the majority of initiatives is of relatively small relevance, even though some of them do contribute to the NNN or N2000. Locally, however, a lot of initiatives have a potential to realize a significant impact, if only by conserving or creating small patches of green. Green self-governance can be seen as local customized governance, where citizens often take up those tasks not covered by traditional actors, aid in the co-production of policy objectives on the local scale, or provide a critical view on plans or developments. In this, green self-governance can provide a valuable contribution to nature and landscape and a valuable addition to other forms of green space governance. However, we do not have any evidence that green self-governance is replacing existing management on a large scale.

5.3. The self in green self-governance

While some scholars and policy makers put an emphasis on the independence and autonomy of citizens in self-governance, we also highlight an involvement of many other actors: authorities, businesses, NCOs and NGOs all play roles in many green self-governance practices by contributing to activities or facilitating those. Most green self-governance initiatives appear to be at least somewhat embedded in existing governmental, societal and financial networks. In this, we observe that the boundaries between self-governance and co-governance are somewhat blurred – a lot of practices in our inventory do not fully fit either of these descriptions.

We see significant relationships between the involved actors and sources of income and between the protected status of areas and the activities that citizens employ. Of particular interest in this respect is the role of authorities. The involvement of local authorities is often important to formally legitimize local initiatives (Halloran & Magid, Citation2013). As authorities have the means to issue permits for allowing certain activities and are often the landowner of local green space, they can play both enabling and constraining roles (for more in-depth discussion of such mechanisms, see studies by Klein, Juhola, & Landauer, Citationin press; Mattijssen et al., Citationin press). Existing policy for protected areas is generally more strict, which might explain why there is much less physical activity by citizens in such areas.

Authorities also play an important role in the financing of green self-governance practices. Subsidies form a welcome and frequent source of income and can be seen as a strong indication that authorities support green self-governance initiatives. However, although the financial network of many groups is generally quite well-developed, this highlights that many green self-governance initiatives are financially dependent on authorities. Our cross-calculations highlight that there is less internal income when authorities and businesses are actively involved, further underlining this dependency. In this respect, it is not surprising that respondents in our interviews have identified a decline in subsidies as a major threat towards the continuity of their initiatives.

When discussing subsidies, we also have to be aware that these are often ‘labelled’ for a certain purpose and that initiatives often have to meet specific prerequisites in order to apply for subsidies, for example, being a legal person. Authorities seem to have a preference to deal with initiatives that have objectives corresponding to their own policy aims (van Dam et al., Citation2015), described as ‘cherry picking’ by Edelenbos (Citation2005). Initiatives that potentially contribute to these aims will be more likely to receive subsidies, while we see that initiatives engaged in protest are much less likely to do so. Yet, as has become clear in recent years, views of nature that live in society are sometimes broader than those embedded in policy. Following a previous crisis in nature policy in the Netherlands (Buijs et al., Citation2014), authorities would do well to also support alternative views and to listen to critical voices.

By supporting some initiatives and not supporting or even constraining others, authorities play an important role in green self-governance. This is not necessarily a bad thing. While some scholars are critical on the exclusion of non-active citizens in the debate on ‘active citizenship’ (Milana, Citation2008), authorities, in principle, should represent all citizens. Important to realize in this context is also that many citizens voluntarily choose to cooperate with authorities or established NGOs. Uitermark (Citation2015) argues that local initiatives are often initiated by people with strong professional and/or social networks. It is likely that citizens will use this social capital in their activities (Teles, Citation2012), and this might be beneficial for the accomplishment of their objectives. This is also a form of autonomy: when cooperation is not forced upon citizens, it might be an important strategy to actively seek cooperation – even if this means that citizens will have to broaden their scope or change their activities to do so. As other research shows, collaboration between citizens and authorities can lead to important mutual benefits (Klein et al., Citationin press; Kronenberg, Pietrzyk-Kaszyńska, Zbieg, & Zak, Citation2015).

6. Conclusions

Our study highlights a large diversity in green self-governance practices, showing that green self-governance is a broad phenomenon. With this study, we provide insights in this diversity and into some important characteristics of green self-governance initiatives. We also highlight correlations between many of the characteristics which we studied, showing that for example the involvement of certain actors has a significant influence on the objectives, activities and financial sources of green self-governance practices.

Our results indicate that green self-governance has a potential to contribute to the protection and management of green space and also to environmental education and social cohesion, among others. However, even if some green self-governance initiatives are active within protected areas, the contribution of green self-governance towards the realization of (inter)national policy goals is of a small scale, and we should be aware that citizens and authorities sometimes have different objectives. We argue that the added value of green self-governance should mostly be seen on the local level and as an addition to traditional management, rather than as a replacement.

Although we conclude that self-governance is often not completely ‘self’ in a literal sense, citizens have a major role in setting the objectives of initiatives and employing activities to reach these. However, many initiatives are dependent upon authorities when it comes to funding and regulations. By supporting some initiatives and constraining others, authorities play an important role in relation to green self-governance. However, collaboration between citizens and authorities is often voluntary and has a potential to produce mutual benefits.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all members from our advisory group and our commissioners for all their comments in various stages of this research project. We also owe our gratitude to all other experts who offered valuable advice or feedback or with whom preliminary results were discussed. A special thanks goes out to Marieke Meesters, who has conducted 21 interviews during our data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Thomas Mattijssen works as a researcher at Wageningen University Research, Forest and Nature Conservation Policy Group. His work focuses on the interactions between humans and their green environment, with a particular focus on the role of active citizenship in governance and management of green space.

Arjen Buijs works as a senior researcher at Wageningen University Research, Forest and Nature Conservation Policy Group and as a researcher at Wageningen Environmental Research. He is a trained sociologist who works in the field of socio-ecological interactions, with a specific focus on the role of citizens and self-organisation in nature conservation practices across Europe.

Birgit Elands works as an assistant professor at Wageningen University Research, Forest and Nature Conservation Policy Group. Her work focuses on human perceptions of the environment and on interactions between humans and physical green spaces, including topics such as recreation and cultural representations of nature.

Bas Arts is professor at Wageningen University Research, Forest and Nature Conservation Policy Group. His teaching and research focuses on international forest, biodiversity and climate change governance, local natural resource management and their interconnections (local-global nexus, multi-level governance).

ORCID

Thomas Mattijssen http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0822-4012

Arjen Buijs http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1683-6182

Birgit Elands http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0233-0751

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Other research describing forms of self-governance can also use the terms self-organisation, DIY-governance, bottom-up governance or citizen governance.

References

- Apostolopoulou, E., Bormpoudakis, D., Paloniemi, R., Cent, J., Grodzińska-Jurczak, M., Pietrzyk-Kaszyńska, A., & Pantis, J. D. (2014). Governance rescaling and the neoliberalization of nature: The case of biodiversity conservation in four EU countries. International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology, 21, 481–494. doi: 10.1080/13504509.2014.979904

- Arnouts, R., van der Zouwen, M., & Arts, B. (2012). Analysing governance modes and shifts – governance arrangements in Dutch nature policy. Forest Policy and Economics, 16, 43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2011.04.001

- Arts, B., & Leroy, P. (2006). Institutional dynamics in environmental governance (Vol. 1, pp. 1–294). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Arts, Bas, Leroy, Pieter, & van Tatenhove, Jan. (2006). Political modernisation and policy arrangements: A framework for understanding environmental policy change. Public organization review, 6(2), 93–106. doi: 10.1007/s11115-006-0001-4

- Ayana, A. N., Vandenabeele, N., & Arts, B. (2015). Performance of participatory forest management in Ethiopia: Institutional arrangement versus local practices. Critical Policy Studies, 11(6), 19–38.

- Beunen, R., & de Vries, J. R. (2011). The governance of Natura 2000 sites: The importance of initial choices in the organisation of planning processes. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 54, 1041–1059. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2010.549034

- Bovaird, T., & Löffler, E. (2013). From engagement to co-production: How users and communities contribute to public services. In V Pestoff, T Brandsen, & B Verschuere (Eds.), New public governance, the third sector and co-production (pp. 35–60). New York: Routledge.

- Bovaird, T. (2007). Beyond engagement and participation: User and community coproduction of public services. Public Administration Review, 67, 846–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00773.x

- Buijs, Arjen. (2009). Public natures: Social representations of nature and local practices (pp. 1–296). Wageningen, The Netherlands: Wageningen University.

- Buijs, A., Mattijssen, T., & Arts, B. (2014). “The man, the administration and the counter-discourse”: An analysis of the sudden turn in Dutch nature conservation policy. Land Use Policy, 38, 676–684. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.01.010

- Buijs, A. E., Mattijssen, T. J.M., & Elands, B. H.M. (2016). Betekenis groene burgerinitiatieven voor natuurbeheer. Landschap, 3, 132–141.

- Buijs, Arjen E., Mattijssen, Thomas J.M., & Kamphorst, Dana A. (2013). Framing: de strijd om het nieuwe natuurbeleidsverhaal. Landschap, 1, 32–41.

- Buijs, Arjen E., Mattijssen, Thomas J.M., & Kamphorst, Dana A. (2013). Framing: de strijd om het nieuwe natuurbeleidsverhaal. Landscap, 30(1), 32–41.

- Buizer, M., Elands, B. H. M., Mattijssen, T. J. M., van der Jagt, A., Ambrose-Oji, B., Geroházi, E., & Santos, E. (2015). The governance of urban green spaces in selected EU-cities, p. 97. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen.

- Derkzen, P., & Bock, B. (2009). Partnership and role perception, three case studies on the meaning of being a representative in rural partnerships. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 27, 75–89. doi: 10.1068/c0791b

- Edelenbos, J. (2005). Institutional implications of interactive governance: Insights from Dutch practice. Governance, 18, 111–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0491.2004.00268.x

- Fors, H., Molin, J. F., Murphy, M. A., & Konijnendijk van den Bosch, C. (2015). User participation in urban green spaces – for the people or the parks? Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 14(3), 722–734. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2015.05.007

- Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Goodwin, M. (1998). The governance of rural areas: Some emerging research issues and agendas. Journal of Rural Studies, 14, 5–12. doi: 10.1016/S0743-0167(97)00043-0

- Grayson, D., Robins, G., & Pattison, P. (1997). Evidence, inference, and the ‘rejection’ of the significance test. Australian Journal of Psychology, 49, 64–70. doi: 10.1080/00049539708259855

- Hajer, M. (1995). The politics of environmental discourse: Ecological modernization and the policy process. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 344 pp.

- Halloran, A., & Magid, J. (2013). The role of local government in promoting sustainable urban agriculture in Dar es Salaam and Copenhagen. Geografisk Tidsskrift-Danish Journal of Geography, 113, 121–132. doi: 10.1080/00167223.2013.848612

- Heesen, R. (2014). How much evidence should one collect? Philosophical Studies, 172, 2299–2313. doi: 10.1007/s11098-014-0411-z

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2001). Types of multi-level governance. European Online Integration Papers, 5, 1–24.

- Hoskins, B. L., & Mascherini, M. (2009). Measuring active citizenship through the development of a composite indicator. Social Indicators Research, 90, 459–488. doi: 10.1007/s11205-008-9271-2

- Klein, J., Juhola, S., & Landauer, M. (in press). Local authorities and the engagement of private actors in climate change adaptation. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy .

- Kronenberg, J., Pietrzyk-Kaszynska, A., Zbieg, A., & Zak, B. (2015). Wasting collaboration potential: A study in urban green space governance in a post-transition country. Environmental Science and Policy, 62, 69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2015.06.018

- Lawrence, A., & Ambrose-Oji, B. (2015). Beauty, friends, power, money: Navigating the impacts of community woodlands. Geographical Journal, 181, 268–279. doi: 10.1111/geoj.12094

- Lawrence, A., De Vreese, R., Johnston, M., Konijnendijk van den Bosch, C. C., & Sanesi, G. (2013). Urban forest governance: Towards a framework for comparing approaches. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, 12, 464–473. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2013.05.002

- Mattijssen, T. J. M., Behagel, J. H., & Buijs, A. E. (2014). How democratic innovations realise democratic goods. Two case studies of area committees in the Netherlands. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 58(6), 997–1014. doi:10.1080/09640568.2014.905460

- Mattijssen, T., Buijs, A., & Elands, B. (in press). Self-governance in nature conservation: From benefits to co-benefits of active citizenship. Journal for Nature Conservation.

- Mattijssen, T., Van der Jagt, S., Buijs, A., Elands, B., Erlwein, S., & Lafortezza, R. (in press). The long-term prospects of citizens managing urban green space: from place-making to place keeping? Urban Forestry and Urban Greening.

- Milana, M. (2008). Is the European (active) citizenship ideal fostering inclusion within the union? A critical review. European Journal of Education, 43, 207–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3435.2008.00344.x

- Mitlin, D. (2008). With and beyond the state – co-production as a route to political influence, power and transformation for grassroots organizations. Environment and Urbanization, 20, 339–360. doi: 10.1177/0956247808096117

- Moro, G. (2012). Citizens in Europe: Civic activism and the community democratic experiment (pp. 1–210). New York: Springer.

- Paloniemi, R., Apostolopoulou, E., Cent, J., Bormpoudakis, D., Scott, A., Grodzińska-Jurczak, M., … Pantis, J. D. (2015). Public participation and environmental justice in biodiversity governance in Finland, Greece, Poland and the UK. Environmental Policy and Governance, 25, 330–342. doi: 10.1002/eet.1672

- Perkins, H. A. (2010). Green spaces of self-interest within shared urban governance. Geography Compass, 4, 255–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-8198.2009.00308.x

- Raco, M., & Imrie, R. (2000). Governmentality and rights and responsibilities in urban policy. Environment and Planning A, 32, 2187–2204. doi: 10.1068/a3365

- Reckwitz, A. (2002). Toward a theory of social practices. A development in culturalist theorizing. European Journal of Social Theory, 5, 243–263. doi: 10.1177/13684310222225432

- Rhodes, R. A. W. (1996). The new governance: Governing without government. Political Studies, 44, 652–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb01747.x

- Rosol, M. (2010). Public participation in post-fordist urban green space governance: The case of community gardens in Berlin. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 34, 548–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00968.x

- Røpke, I. (2009). Theories of practice – new inspiration for ecological economic studies on consumption. Ecological Economics, 68, 2490–2497. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.05.015

- Schatzki, T. R. (1997). Practices and actions: A Wittgensteinian critique of Bourdieu and Giddens. Philosophy of the Social Sciences, 27, 283–308. doi: 10.1177/004839319702700301

- Schatzki, T. (2002). The site of the social. A philosophical account of the constitution of social life and change (pp. 1–296). University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Schatzki, T. (2010). The timespace of human activity: On performance, society, and history as indeterminate teleological events. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Schatzki, T. (2012). A primer on practices. In J. Higgs, R. Barnett, & S. Billett (Eds.), Practice-based education. Perspectives and strategies (pp. 13–27). Rotterdam: Sense.

- Shore, C. (2011). ‘European governance’ or governmentality? The European commission and the future of democratic government. European Law Journal, 17, 287–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0386.2011.00551.x

- Shove, E., Pantzar, M., & Watson, M. (2012). The dynamics of social practice: Everyday life and how it changes. London: Sage.

- Smith, H., Pereira, M., Hull, A., & Konijnendijk van den Bosch, C. 2014. The governance of open space: Decision-making around place-keeping, Place-Keeping: Open Space Management in Practice, pp. 52–75.

- Søgaard, A. J., Selmer, R., Bjertness, E., & Thelle, D. (2004). The Oslo health study: The impact of self-selection in a large, population-based survey. International Journal for Equity in Health. Article no. 3.

- Sørensen, E., & Triantafillou, P. (2009). The politics of self-governance (pp. 1–223). Farnham: Ashgate Publishing.

- Stoker, J. (1998). Governance as theory: Five propositions. International Social Science Journal, 50, 17–28. doi: 10.1111/1468-2451.00106

- Teles, F. (2012). Local governance, identity and social capital: A framework for administrative reform. Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management, 7, 20–34.

- Ten Cate, B., Dirkx, J., Hinssen, P., van Koppen, K., & Vader, J. (2013). Burgerinitiatieven zijn beter voor de natuur. Of niet? Wettelijke Onderzoekstaken Natuur & Milieu. Wageningen: Wageningen UR.

- Thuessen, A. A. (2010). Is LEADER Elitist or Inclusive? Composition of Danish LAG boards in the 2007-2013 Rural Development and Fisheries Programmes. Sociologica Ruralis, 50(1), 31–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9523.2009.00500.x

- Uitermark, J. (2015). Longing for Wikitopia: The study and politics of self-organisation. Urban Studies, 52, 2301–2312. doi: 10.1177/0042098015577334

- Van Assche, K., Beunen, R., & Duineveld, M. (2014). Governance and it’s categories. In K. Van Assche, R. Beunen, & M. Duineveld (Eds.), Evolutional governance theory: An introduction (pp. 65–78). New York, NY: Springer.

- van Dam, R., Duineveld, M., & During, R. (2015). Delineating active citizenship: The subjectification of citizens’ initiatives. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 17, 163–179. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2014.918502

- Van Dam, R., Eshuis, J., & Aarts, N. (2009). Transition starts with people: Self-organising communities ADM and golf residence Dronten, Transitions Towards Sustainable Agriculture and Food Chains in Peri-Urban Areas, pp. 81–92.

- van Dam, R., Salverda, I., & During, R. (2014). Strategies of citizens’ initiatives in the Netherlands: Connecting people and institutions. Critical Policy Studies, 323–339. doi: 10.1080/19460171.2013.857473

- Van der Jagt, A. P. N., Elands, B. H. M., Ambrose-Oji, B., Gerőházi, E., & Steen Møller, M. (2016). Participatory governance of urban green space: Trends and practices in the EU. Nordic Journal of Architectural Research, 28.

- Van Melik, R., & Van Der Krabben, E. (2016). Co-production of public space: Policy translations from New York City to the Netherlands. Town Planning Review, 87, 139–158. doi: 10.3828/tpr.2016.12

- van Tatenhove, J., Arts, B., & Leroy, P. (2000). Political modernisation and the environment. The renewal of environmental policy arrangements. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

- Verhoeven, I., & Tonkens, E. (2013). Talking active citizenship: Framing welfare state reform in England and the Netherlands. Social Policy and Society, 12, 415–426. doi: 10.1017/S1474746413000158