ABSTRACT

Green infrastructure (GI) research has grown in prominence as planners, politicians and environmental specialists have promoted its socio-economic and ecological value in urban environments. However, as the pace of growth has continued so has the exploration of how GI can mitigate the impacts of poor air and water quality, promote improved quality of place and support economic prosperity. Unfortunately, investments can be undermined by weak organisational understandings of the financial and societal value of GI. Consequently, we identify a historical reluctance by decision-makers and developers to support GI, partially based on the outdated appreciation of economic-ecological value compared to other built infrastructure. To examine how cities respond this paper discusses GI as a ‘boundary object’ aligning divergent understandings of the ongoing challenges and responsibility for GI funding. Using an examination of public, private and environment sector practice in London (UK), the paper argues that opportunities exist to align alternative funding mechanisms using ‘GI’ to promote cooperation between economically and socio-ecologically focussed stakeholders.

Introduction

Green Infrastructure (GI) planning in London has been positioned within policy and practice debates as holding a significant value in promoting the city economically, socio-culturally and ecologically. As a city comprising approximately 49% green/blue space, London is considered to be one of the world’s greenest, and GI is situated as a core component of its socio-cultural, economic and ecological value (Mell, Citation2016). London’s GI includes the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, the portfolio of Royal Parks, and London’s waterways, which are all examples of high quality GI being used to ‘sell’ London to residents and investors (Mayor of London, Citation2021). London is not alone in utilising GI to promote itself as a green and liveable city. New York has used GI, i.e. Central Park and the New York Green Infrastructure Plan to promote itself as a more resilient city (Meerow, Citation2020; New York Environmental Protection, Citation2010), whilst the Singaporean government has made extensive use of the city’s greening efforts to illustrate the links between economic growth and ecologically sensitive urban design (Tan et al., Citation2013). Moreover, the Siemens AG (Citation2011) Green City Index illustrates the added-value of developing high quality and multi-functional urban landscape in promoting liveability.

However, the functionality of London’s GI is being compromised, as it attempts to meet housing, transportation and employment needs, which can require the conversion of GI into built infrastructure (Mayor of London, Citation2016). Although common to many cities, especially those in the USA, China and India, land values make the financial rationale for investing in GI challenging compared to ‘grey’ infrastructure. Furthermore, London’s blend on historic and contemporary infrastructure, comparable to New York, adds a layer of complexity to development debates. However, evidence arguing that London’s GI is worth £91 billion per annum to its economy has helped to locate GI in comparable discussions of other infrastructure (Greater London Authority et al., Citation2017). Those tasked with developing GI in London: the Greater London Authority (GLA), the city’s local government units, as well as the environment sector and communities have drawn on this research arguing for investment in GI. Unfortunately, the complexity of the existing financial mechanisms used to deliver GI has failed to identify sustainable funding streams. Additionality, the lack of a definitive platform aligning public-private investment agendas needs to be navigated by stakeholders in London, and internationally.

To address the divergence in financial interpretations the following debates contemporary approaches to GI funding in London. Drawing on stakeholder representations from public, private and community/environmental organisations, the paper examines the socio-economic, ecological and political factors influencing GI financing. London’s GI advocates have been at the forefront of innovations in partnership working, design and management providing scope to examine the successes achieved to date. By reflecting on what stakeholders fund we discuss why and how this differs between organisations, and offer an analysis of the variability of GI funding located within an urban context where financial innovation, stakeholder engagement, and the delivery of GI are prominent. Although this process is visible in many cities, we position GI in London as a front runner in terms of its advocacy and delivery providing transposable examples to other cities. Moreover, examining this process from a multi-sector perspective presents a contemporaneous understanding of the funding landscape, the challenges of changing praxis, and proposals for a continuity in delivery that can be applied in other locations, i.e. GI knowledge brokering via the Town & Country Planning Association Planning for Environment and Resource eFficiency project in European Cities and Towns (PERFECT), which worked with local government partners to assess best-practice for GI investment (Hudeková et al., Citation2019).

To achieve these aims the paper is structured as follows. First, the nuance of GI funding changes are outlined, this is followed by an introduction to GI as a ‘boundary object’, which is used to frame multi-stakeholder discussions. The paper’s methodology is then presented before analysing current funding practices. The paper concludes with a reflection on the alternative funding opportunities available to GI advocates to support landscape enhancement.

Establishing the context of GI investment

Attempts to balance divergent understandings of economic growth and ecological protection are grounded in a confluence of political, economic, socio-cultural and environmental influences (Anguelovski et al., Citation2018). They are framed via assessments of the trade-offs associated with developing more sustainable forms of urban planning – an area of planning often overlooked (Campbell, Citation1996). Where socio-economic and political factors align with environmental thinking it can facilitate innovation in GI investment (Davies & Lafortezza, Citation2017). However, the variability of delivery within the UK, and internationally, has limited continuity between stakeholders regarding the ‘economic’ value of GI. Attempts to align desirable outcomes for public, private and community/environmental stakeholders has proven difficult, and requires further examination of the approaches, motivations and resources needed to facilitate GI interventions (Hislop et al., Citation2019; Meerow, Citation2020). In practice this has led to a mechanisation of planning, where metrics and benchmarks are considered essential in persuading decision-makers, especially in the private sector, to invest (Calvert et al., Citation2018). However, an analysis of the ‘multiple benefits of green infrastructure projects now provides a rationale for a significant increase in funding … [and] the rationale for the diversification of the sources of funding’ (Howard, Citation2020, p. 3).

Within this discussion, and this paper, ‘Green infrastructure’ is presented as London’s ‘network of parks, green spaces, trees and other features such as green roofs’ (Mayor of London, Citation2014, p. 17). GI supports human and environmental systems and is framed as being critical to delivering sustainable urban growth. Investment in GI can deliver multi-functional socio-economic and ecological benefits to a range of communities via a network of green/blue spaces. It promotes connectivity between people and the environment supporting access to nature as part of process of environmental education, interaction and stewardship. Effective GI implementation should be integrated into policy with the same level of political support as other socio-economic and grey/built infrastructure (Mell, Citation2016). However, although a cannon of research supports this assessment of what GI is, we position it as lacking a fixed disciplinary acceptance, which on occasions leads to a failure to integrate ecological knowledge within praxis (Mell & Clement, Citation2020). This limits the development of a coherent agenda for GI in many cities, as policy mandates continue to address urban and environmental development unequally (Nesta, Citation2016). It also illustrates the complex negotiation needed between Local Planning Authorities (LPA), the development sector, and communities in order to establish balance between economic and socio-ecological agendas.

Cities including Berlin (Lachmund, Citation2013), Philadelphia (Philadelphia Water Department, Citation2011), and Singapore (Tan et al., Citation2013) have started to address the disparity in the provision of green and built infrastructure from a more holistic perspective. In these locations, responses to climate change can be seen as driving the use of GI (Meerow, Citation2020). Moreover, a growing literature argues that the financial returns of ‘greener’ development, can be considered as a significant influence on funding (Siemens AG, Citation2011). However, we continue to witness the conversion of GI for housing and commercial infrastructure, as these activities explicitly support economic growth agendas despite its impacts on environmental functionality.

GI funding has historically drawn from a range of public, environmental, private and community sources facilitating investment in green and open spaces (). We can argue that this mirrors the diversity of approaches used in urban planning but has limited the establishment of a universal approach to GI development. Consequently, engagement with myriad GI typologies, investment at different scales, and diverse leadership from the public, private, environmental and community sectors have all placed limitations on implementation (Calvert et al., Citation2018). Consequently, GI financing has struggled to identify sustainable funding streams even when delivered through collaborative practice. The complexity of GI funding increased post-2010 in the UK when central government funding decreased as part of a national austerity mandate (Mell, Citation2020). Although this mirrors a wider contraction of infrastructure funding for social services, i.e. libraries and social care, we argue that non-statutory local government provision was subject to more significant cuts due to a lack of legal protection, i.e. 50% of the core LPA budget was lost between 2010 and 2015 in Liverpool. It is clear that as a consequence LPAs have been forced to make difficult decisions regarding the ongoing provision of social and environment services (Mell, Citation2018).

LPAs in the UK raised significant concerns over long term provision of GI due to disproportionate funding cuts, i.e. approximately 90% in Newcastle (Mell, Citation2020). A subsequent discussion emerged within academic and practitioner research reflecting on how LPAs and other advocates have transitioned to alternative funding mechanisms. As with other areas of service provision, i.e. health, GI advocates have engaged in a diverse examination of options associated with private sector funding, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), environmental grants, alternative management contracts, and Community Asset Transfers (Nesta, Citation2016). In addition, there is a groundswell of discussion assessing the potential of Park Trust models (Liverpool City Council, Citation2016), endowments, sponsorship, and precepts on new developments to fund GI, i.e. in Atlanta for the BeltLine project (Tempany & Armour, Citation2020).

As the range of funding mechanisms increases, it is important to integrate an understanding of scale and the variation of GI type that can be delivered (see ). Utilising a scalar perspective provides scope to align strategic GI mandates, i.e. flood management, with localised provision, i.e. parklets, green walls or street trees to deliver socio-economic and ecological benefits. All of which can be delivered via public or private means, and move beyond simplistic discussions of GI as being predominately public parks (Koc et al., Citation2017). Although a significant proportion of GI investment is focussed at the site/local scale, especially in London, there is an explicit understanding that locates these practices within a wider network perspective (Hansen & Pauleit, Citation2014). To achieve this in London the GLA has worked extensively with public, private and environmental stakeholders to ensure GI is planned locally by LPAs and as part of an all-London GI network. Such a multi-scaled approach ensured that issues of climate change, flood management, biodiversity enhancement, and access to GI have been debated at a number of scales. GI projects are therefore considered as key components of a hierarchy of spaces that includes site, street, neighbourhood, district and city-scale interventions (Mayor of London, Citation2018).

Table 1. Common GI typologies (developed from Mell & Whitten, Citation2021).

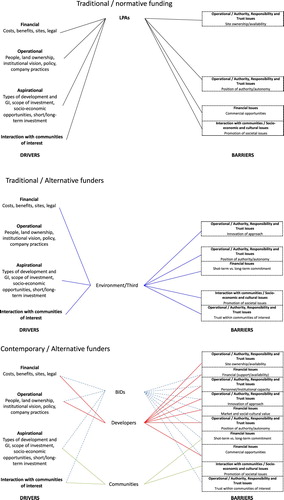

At each of these scales three distinctive groups of stakeholder can be identified as supporting GI funding ():

Traditional/normative funders,

Traditional alternatives, and

Contemporary alternatives: Business Improvement Districts (BIDs), transport and infrastructure providers and developers.

However, due to austerity traditional financing mechanisms have been challenged and a growing variability is visible in who provides financial support for GI. To understand the role of public, private, environment and community actors in GI funding requires further exploration. The attention shift away from LPAs raises questions regarding the responsibility placed on public bodies to manage assets if public spaces are increasingly used for commercial activities (Smith, Citation2017). Moreover, consideration of the ways in which the private sector utilise sustainable drainage or street trees to increase property prices or green walls/roofs to support corporate sustainability targets is also needed. Commercialisation opportunities are therefore not the sole purview of LPAs but are relevant to all GI organisations. The breadth of options available suggests that a more refined approach to GI funding is needed but remains dependent on stakeholder understanding of GI type and benefits.

Green infrastructure as a boundary object

To understand the complexity of funding arguments requires a contextualisation of how GI is situated within planning discourses (Reimer & Rusche, Citation2019). As noted above, an established literature outlines a grounded set of principles for GI, articulating connectivity, access to nature, and the delivery of socio-economic-ecological multi-functionality to multiple stakeholders (Mell, Citation2016). However, although GI advocates adhere to these principles, there remains variability in how non-environment specialists engage with them. To examine variations in funding, we propose GI as a boundary object. Baggio et al. (Citation2015) described a boundary object as a concept shared between disciplines but interpretated differently by each. Thus, GI can be positioned as being adaptable to built, natural and engineering disciplinary needs with the flexibility of a boundary object facilitating stakeholder collaboration beyond established practices (Garmendia et al., Citation2016). When considered as a boundary object GI promotes multi-partner dialogue based on alternative interpretations. Such a loosely defined approach can lack rigour in its facilitation of stakeholder communication limiting knowledge transfer due to competing disciplinary silos (Koc et al., Citation2017). However, locating GI as a boundary object allows different terminology, as well as methods to be ‘borrowed’ between disciplines, leading to more grounded approaches being used in practice (Dornelles et al., Citation2020). We can also argue that GI has been positioned effectively at a confluence of planning discourses engaging developers, real estate, environment and planning specialists enabling ‘plausible solutions to complex environmental situations’ to be found via the delivery of principles GI whilst maintaining organisational practices (Brand & Jax, Citation2007; Dornelles et al., Citation2020, p. 2).

Situating GI as a boundary objective allows this paper to examine its mobility by different natural and built environment stakeholders. This is framed within a discussion of GI funding transcending siloed thinking to facilitate a collective engagement with alternative disciplinary understandings (Baggio et al., Citation2015). Within this framing, the economics of GI provides continuity between policy and delivery, as organisations are able to reflect upon the interrelationships between the costs and benefits of investment. The perceived rigidity of existing financial models provides a further reason to view GI as a boundary object (Heink & Kowarik, Citation2010), as within development debates environmental practices are viewed as malleable in their response to ecological influences compared to the permeance of economic thinking. Considerations of GI as a boundary object thus enables an exploration of practice promoting a more nuanced appreciation of its financial values.

Greening London: development versus landscape management in London

London’s population is predicted to exceed 10 million by 2036. To meet the needs of expansion it is proposed that one million new homes are needed (Mayor of London, Citation2017). Running in parallel is a need to ensure that London’s ecological resource base is not compromised through conversion to built infrastructure. Development narratives in London could, as a consequence, be depicted as binary, focussing simplistically on economic growth or environmental protection (Mayor of London, Citation2018). Despite extensive evidence establishing the societal, economic and ecological benefits of GI there remains reluctance from some built environment professionals to engage with these discussions (Payne & Barker, Citation2015). Such hesitancy has its foundations in siloed disciplinary mentalities, the perceived irrationality of development refusals by LPAs, disputed economic evidence supporting GI, and greater economic viability in delivering housing. Raco et al. (Citation2019, p. 1073) noted though that investors need to be appreciative of the range of policy and planning regulations ‘to develop over time a deep, nuanced understanding and working knowledge of the characteristics, preferences and practices underpinning development’. Moreover, countering viability arguments Vivid Economics and Barton Willmore (Citation2020) proposed that an estimated return of £100 per £1 spent on landscape enhancement balancing the lack of economic uncertainty associated with environmental investment. However, to establish a supportive investment environment requires LPAs, and other stakeholders, to consider the range of GI benefits and align them with social housing provision, public health programmes, and climate change adaptation – key planning issues in London (Mayor of London, Citation2021).

It is within this policy/practice space that the GLA has worked to align divergent public, private, environmental and community understandings of GI. Over an extended period, the GLA has acted as the coordinating body of GI planning due to their position as facilitators of strategic thinking and as policy advocates at the borough/LPA scale. Through this coordination role, and as custodians of the London Plan (Mayor of London, Citation2021), they have been able to liaise with stakeholders from across the public-private interface to support commercial, as well as societal gains from GI. However, it needs to be recognised that the GLA has fewer legal powers to deliver GI than LPAs, and therefore act as a conduit for knowledge exchange bridging divergent views of development. London’s governance structures thus place greater emphasis on LPAs to develop policy aligned with GLA objectives, whilst continuing to address local development needs (Raco et al., Citation2018).

Due to the complexity of this process, the timeframes associated with the accrual of GI benefits can also be problematic. Returns on GI investment are considered long-term, and remain part of the rationale of underinvestment from developers (Raco et al., Citation2019). In practice this has restricted the budgeting of the LPAs for GI, as financial support needs to be programmed with a level of certainty (Mell, Citation2020). Consequently, a single approach to public, private or community-led investment is unlikely to meet the longer-term requirements of GI funding; a more nuanced appreciation of the diversity of financial support is therefore needed. Moreover, UK government has argued for a commercialisation of GI prompting successive London Mayors to commodify London’s environment enabling commentators to utilise GI as a ‘selling point’ for investors (Mayor of London, Citation2018).

Methodology

London has been an innovator in aligning public, private and community approaches to GI funding. This has, and continues to be, supported by a strong advocacy arena with LPAs, the environment and development sectors, and local communities being activity engaged in GI development. Consequently, investment in GI in London provides valuable insights into how alternative funding mechanisms can address tensions between policy and practice. London’s high land values provide an additional rationale for examination. If GI can address the complexity of cost–benefit analysis in London then these practices can be applied elsewhere. London also illustrates how different LPAs, environment and development sector organisations are investing in GI, which is important when ‘landscape’ is not a statutory service with legal protection.

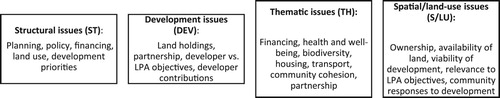

To evaluate GI funding in London a series of expert interviews were conducted (January–April 2018). Facilitated by the Greater London Authority (GLA), who acted as a gatekeeper, the research engaged developers (Interviews D1-2), environmental and thirdFootnote1/charity organisations (ENV1-8), Business Improvement Districts (BIDs)Footnote2 (Interviews BID1-4), and the public sector (LPA/PS1-5) (). Nineteen participants were interviewed based on their project and strategic decision-making experience. All held a professional understanding of the benefits of GI and were considered knowledgeable about traditional/normative funding mechanisms, as well as contemporary developer and community/third sector options. Semi-structured interviews were conducted focussing on policy, delivery, financing arrangements and organisational engagement with local communities, businesses and delivery partners. Interviews were analysed via a thematic analysis of core themes derived from the research literature. presents the thematic structure of the analysis. Questions were aligned with the practices of each stakeholder focussing on the influence of policy, delivery and organisational considerations of the economic value of GI. Further questions focussing on the perceived returns on investment, and engagement with multi-sector stakeholders were embedded in all interviews. Analysis was triangulated through cross-referencing of interview commentary, discussions with the GLA and reflections of policy/practice documentation produced by interviewee organisations.

Table 2. Stakeholder participant list.

The paper acknowledges that the gatekeeping role of the GLA frames it with a partial engagement with the wider community of government, planning, development and environment stakeholders located within London. However, no instances of respondents suggesting that the GLA held an overt influence over their use of GI were reported. Although GLA assistance installs a ‘pro-GI’ discourse within the commentary, each participant discussed their organisational transition towards this view. Participant reflections identified political, ecological and economic factors that both limited and supported their use of GI. Although this presented predominately supportive response for GI it also illustrated examples where the engagement with GI was the culmination of a longer-term evaluative process. The paper also queries whether a wider set of respondents drawn from natural and built environment stakeholders not engaged with GI delivery would have been able to provide detailed evidence of its financing, delivery or management. Moreover, the participants engaged were drawn from cross-section of key stakeholders engaged with the provision of GI in London, and were knowledgeable about alternative funding mechanism, barriers to GI investment and their delivery in practice.

Results and analysis

The following sections highlight the complementarity and complexity of financing focussed on the structural, thematic and spatial/land-use issues associated with GI investment. Through an analysis of funding mechanisms drawn from across the public–private–environment sectors the following examines contrasting approaches identifying best-practice, as illustrated by one LPA official (LPA/PS5):

All LPA funding for GI has been reduced in London, and all open space managers would say they have less money. But the level of cuts is variable and depends on the priorities of each LPAs … and there is no model, no guidance actually, even from central government because its non-statutory.

LPA/public sector

LPAs and public sector bodies across London have been subject to variable funding cuts depending on the demographic, development and asset portfolios of each organisation.Footnote3 The range of reductions has led to an increased diversity in management, as stated by LPA/PS5:

Ultimately there is no imperative [for LPAs] to provide that money [for GI], it’s local decision-making and local prioritisation, and that’s why you end up with squeezed points where LPA has to say its divesting itself of an asset because there is insufficient money to maintain it.

An area of ongoing discussion was the promotion of knowledge exchange in aligning the economic benefits of GI with specific policy mandates. It was reported that explicit LPA acknowledgement is needed linking investment in GI with payback timescales and cost–benefit analysis. As LPA/PS4 stated:

Economically developments tend to outperform when they have GI than when they don’t. It’s kind of a no brainer from a financial perspective, and [has] a lot of social benefits, obviously. Across the board [GI] is a very sensible approach and something that needs to be part of every single project. We’re also looking to codify the intention and aspiration of what we want to achieve, and are embedding that in our business models so that everything we bring forward does have GI, and does have a way to viably fund it and manage it in the long-term.

Business Improvement District (BIDS)

BIDS are increasingly important GI delivery advocates acting as conduits between businesses, residents and LPAs (BID1; BID2; BID3; BID4). Due to their position as representatives of the business community they hold a strategic position in GI investment. By situating themselves at the interface of local and city-scale environmental discussions, BIDs can work more effectively with local businesses and the GLA to embed flexibility in the planning of GI compared to LPAs (BID1). Moreover, BIDs consider themselves as negotiators and educators of the business community, as well as proposers of innovation in landscape enhancement (BID1; BID2; BID3; BID4). However, in some BIDs GI is not supported by the whole business community, as subscribers do not acknowledge its added economic value (BID4). Consequently, BIDs continually engage stakeholders to align individual economic considerations with the benefits delivered by GI. The success of each BID in promoting GI reflects their long-term engagement with the business community installing them as trustworthy ‘custodians’ of change (BID1; BID2; BID3; BID4). This includes the directing of projects with businesses, and managing dialogue with landowners, i.e. Transport for London (TfL), and the GLA (BID2; BID3).

A further function of each BID has been to disseminate the added value of GI investment through discussions of economic uplift and the growing ‘visibility’ of businesses due street scene improvements. BIDs, therefore, hold a key communication role in the long-term abatement of landscape enhancement costs to the business sector (BID3). To achieve this, BIDs have employed a flexible approach for project funding, securing support from the GLA, developers, business subscriptions, and the increasingly from CSR. However, a note of caution was raised by BID2 and BID3, as BIDs are subject to election/re-election by subscribers every five years, and therefore need to continue to facilitate investment that meet business expectations. Thus, promoting GI has become a longer-term goal enabling BIDs to liaise with businesses over an extended timeframe. In the BIDs engaged within this work, this process had become easier as communication of the economic evidence for GI has been aligned with local businesses aspirations, i.e. additional footfall promoting economic growth. GI was, therefore, less contentious within re-election ballots, as BIDs had successfully allayed concerns regarding economic uplift from investment leading to the delivery of street trees, community orchards, parklets and innovative ‘Metal Box Gardens’ (BID2; BID3).

Developers

The ways in which developers engage with GI varies depending on their asset portfolio and strategic objectives, with ‘high-end’ developers being able to experiment with new approaches, i.e. GI, due to their financial security. Both DEV1 and DEV2 were delivering investments of high market value, and acknowledged that they had a greater financial security to invest in GI compared to volume house builders or smaller companies. Moreover, to DEV1 and DEV2 the provision of GI mirrors the integration of the place-making agenda in practice, as it improves the market value of their ‘product’. This goes beyond ‘greenwashing’, i.e. the provision of limited planting, and embeds high-quality landscape design principles undertaken by in-house or contracted ecological consultancies in developments (DEV2). D1 articulated this stating:

[There is] no point just putting in grass, [we] need to put in right kind of species, hedges, wildflower planting as well. This is where our business is trying to go … linking it to people and buildings and nature, interweave the three of them. (DEV1)

[We’re] quite happy to give [GI] a go … its easy on a big job to lose the costs, as if [a green wall] is up for two years then the publicity for the scheme [means it] was a positive thing to do for the community to get some recognition … and the number of people who will stand outside and take photographs of it and Instagram it. What it’s done is raise the profile of the building, but also the commercial aspect from managing noise control, insulation [of] the noise, and from the eco-perspective. The data is inconclusive about [improving] air quality but we’re finding the amount of flora and fauna in terms of new birds [nesting], strawberries growing in there, spiders, all the good stuff you want to hear about. That was up for two years and we just got on and did it really, there was an acceptance internally to just do it. (DEV2)

The inclusion of GI in development was also linked to environmentally focussed planning policy, and a pre-empting of calls for developer contributions in the form of S106 payments. Thus, DEV1 and DEV2 both considered investment in GI as a mechanism to gain planning consent by meeting local policy requirements through the integration of landscape design principles into developments. This was deemed important, as both LPA and GLA policy requires investment in environmental enhancement as part of their development objectives. Designing GI into investments as a core principle enabled DEV1 and DEV2 to present their developments as being of higher ecological quality meeting air quality, biodiversity and GI requirements, which may otherwise have been demanded to gain planning permission. Such practices are now being integrated into their long-term strategies setting a pathway to deliver GI. This illustrates a process of strategic thinking by developers who view the provision of a higher proportion of GI than required as potentially eliciting more positive reactions from LPAs regarding planning applications (DEV2).

GI is thus being contextualised as an added marketing tool, a ‘wow factor’, that increases the visibility of their product to clients. This is supported by increased interaction between developers, ecologists and landscape architects to ensure multi-functionality is integrated into development (DEV1; DEV2). Developers also recognise the benefits to using innovation, i.e. ‘living wall’ construction hoardings, as a mechanism to limit the impacts of development on local environmental quality. DEV1 and DEV2 also stressed that investment in GI has to be context-specific providing benefits for local business, residents and the developer, as well as meeting a site’s environmental needs.

Environment/third sector

Environmental/third sector participants provided a more diverse commentary on the changes to funding mechanisms, and the growing role of partnerships with private, community and industry organisations in addressing funding cuts. These comments illustrated the precarious nature of funding but also a growing willingness to align practice with a number of socio-economic and ecological agendas to aid GI development. This was raised by ENVS1 who noted that although London is often discussed as a homogenous entity, its division into thirty-three administrative areas adds complexity to funding, as each LPA responds to local socio-cultural, environmental and development priorities. This limits the utility of an overarching approach to funding unless specific programmes led (and funded) by the GLA are developed. Bespoke practices built on stakeholder relationships delivering long-term improvement were therefore seen as more sustainable than singular funding streams.

The key drivers of these discussions were issues of tenure, capacity, capital/revenue funding, the role of CSR and innovation in project funding. All were inter-connected and should be considered holistically raising questions regarding how environmental organisations manage this process to facilitate investment. One commentator stated that they were ‘actively involved [in GI provision but were] hanging a little bit by the skin of our teeth and asking: where will the money come from?’ (ENVS5). This meant they were rethinking their delivery capacity due to staff turnover, non-renewal of Service Level Agreement (SLAs) and a loss of organisational knowledge. This was seen in other organisations:

Each London borough is different. It often depends on the ‘colour’Footnote4 of the borough … their engagement with our kind of work is very different but you have to unpick why some people see the longer-term value in our work, and others don’t. (ENVS2)

The type of funding generated was also noted as driving what form of GI could be implemented. ENVS1 and ENVS2 reported that capital funding was more frequently available, however, many partners were reluctant to invest if revenue for maintenance was excluded. The latter was deemed elusive, as most funding would not support management. However, as the added socio-economic benefits of GI were reported to businesses, there was a growing understanding that maintenance was central to GI functionality. Consequently, a number of developers and utilities companies were working with environmental organisations to create partnerships including capital and revenue payments (ENVS3, ENVS5). The role of social housing providers, infrastructure projects and innovative tariffs on development, i.e. precepts supporting parks around the Olympic Park, could therefore be extended to supplement financial contributions from development (ENVS6; ENVS7). In addition, the integration of health benefits via engagement with medical practitioners, schools, communities, and food growing organisations was highlighted as being critical in aligning policy with funding (ENVS1; ENVS4; ENVS8). This had led to payments for landscape enhancement and maintenance associated with school yards, parks and housing estates from developers and the NHS (supported by LPA match-funding) (ENVS7). Moreover, employees from corporations were becoming increasingly engaged with environmental projects via CSR schemes, which were viewed as an important mechanism supporting longer-term engagement with GI (ENVS2, ENVS3, ENVS5).

CSR was the most frequently reported alternative funding utilised by environmental organisations to support GI. The benefits of CSR were deemed to be two-fold: first, projects benefitted from people working with environmental teams to improve GI quality, whilst secondly:

The benefits they [corporate workers] actually get out of the day is feeling they’ve done good, and therefore less about the impact they’ve had, but they need to see an impact … but the main impact they’re probably getting out of that day is the fact that the staff come back feeling that they did a good thing. (ENVS3)

Where funding was allocated environmental organisations used CSR to leverage additional funds. This was amplified when larger organisations engaged, as their peers recognised the positive feedback CSR was generating (ENVS5). However, ENVS2 noted that:

Volunteering is not free, [but] it can be very effective. What makes is most effective is the other benefits – the well-being, the cohesion, rather than the outputs. Volunteering can be light on its feet, it can react very quickly, it can influence, it can make big changes, it can empower people, but invariably it requires someone to keep pushing it forward.

perceived need to take a more business orientated view that asks businesses to reflect on what they can do with and for the environment, i.e. green asset management, London wide nature/environment projects and/or sponsorship. (ENVS2)

Discussion

Due to the variation in the benefits that GI delivers stakeholders have utilised a suite of economic, socio-cultural and ecological perspectives to support implementation. Although the scale, focus and tenure of these investments varies, a number of cross-cutting themes can be identified situating GI as a boundary object generating inter-organisational working. These are supported through discussions of the economic uplift associated with GI noted by developers who argued that the financial returns of investment bridge viability issues and allay the reluctance to deliver environmental projects (Neal, Citation2013). Analysis of the added-value associated with GI investment by public and private stakeholders illustrates a growing willingness to engage with the breadth of its benefits, even where they fall outside normative funding models. The evolving role of developers, CSR, and the growth of multi-stakeholder partnerships support this proposition. For commercial enterprises, the additional economic value of GI on-site or via CSR/branding have been prominent factors supporting a transition to development that is inclusive of GI in contrast to traditional approaches (Payne & Barker, Citation2015). BIDS meanwhile have promoted GI investment via aesthetic, ecological and socio-economic improvements.

The growing economic evidence base, successful CSR and targeted campaigns have been critical in addressing the divergent approaches to GI investment between public and private stakeholders, especially where positive outcomes, i.e. receiving planning permission are seen. Notwithstanding this, the impact of austerity on LPA GI funding should not be underestimated (Lowndes & Gardner, Citation2016). Consequently, LPAs in London have been required to reduce services or leverage funding from developer contributions, sponsorships or event revenue. The traditional mechanisms used to fund GI are thus becoming increasingly limited following government-imposed planning reforms and changes in developer obligations (Mell, Citation2018, Citation2020). Each of these approaches to public and/or private funding are unsatisfactory when viewed independently, however when they are considered as a collective suite of financial options they can be used to facilitate cross-organisational working and project delivery due to the promotion of economic returns. Thus, although stakeholder representation in this paper draw on a different sets of benefits to support engagement with GI we can suggest that there is a willingness to collaborate when appraisals of its wider benefits become common place.

(a–c) illustrates the drivers and barriers discussed by the three GI stakeholder groups: normative/traditional, traditional/alternative and contemporary/alternative of . (a–c) proposes that the main drivers of GI investment relate to institutional, partnership, and aspirational issues. These factors were common to all groups along with ongoing discussions of the financial value of GI. This suggests that the aspirations of delivering high quality GI could act as a conduit, i.e. the boundary object, allowing stakeholders to counterbalance the constraints of investment within their disciplinary boundaries, i.e. those associated with institutional capacity or current practice (Baggio et al., Citation2015; Brand & Jax, Citation2007). Due to the recurrence of partnerships as a driver of GI innovation, we propose that investment in environmental enhancement is being used to frame discussions of more detailed ecological and urban design by providing a multi-partner space supporting stakeholder dialogue. This suggests that a more detailed analysis of the operational issues associated with GI development can be made where collaborative partnerships, alternative investment types, and an alignment of the commercial and social benefits associated with GI are examined (Mell & Clement, Citation2020).

Figure 3. (a–c) Drivers and barriers of GI funding in London. Note: (a–c) illustrates the complexity in GI decision-making in London with the drivers of investment influencing development choices, whilst the barriers constraining delivery. Each part of Figure 3 highlights the variability of factors influencing these choices supporting the view that stakeholders engage with GI, and its funding from alternative perspectives.

(a–c) also highlights ongoing barriers to investment. For traditional/normative funders the key barriers were site ownership, authority of the LPA to deliver investment, limitations in commercial/revenue returns, and the need to meet community needs, each of which map onto the literature as core issues limiting GI investment (Mell, Citation2020). For the environment/third sector (traditional/alternatives funders), the limitations expand to include project innovation, long-term funding commitments, and trust between stakeholders. The latter being critical to the formation of sustainable relationships which have faced additional challenges due to austerity. These issues also illustrate the added complexity of applying for funding, as unlike LPAs, the environment sector is more innovative in their ability to secure financial support.

Contemporary/alternative funders are, however, the most varied in terms of barriers to investment, as they remain conscious of institutional, financial and personnel capacity constraints when debating GI. Furthermore, these discussions are shaped by market forces raising concerns over the economic returns on investment for GI. The commentary presented above though signposts a willingness to engage with GI via collaboration and innovation (in capital and revenue spend) where evidence of economic returns can be identified. Thus, although CSR and branding may be prominent in leveraging engagement with GI, the economic ‘bottom line’ retains a critical position in commercial investment (Future of London and Rocket Science, Citation2016).

The barriers to investment presented should not though be considered as permeant limitations. Alternatively, they can be viewed as opportunities for stakeholders to exchange knowledge of co-funding and project delivery at a range of scales. The presentation of GI as a boundary object working to facilitate multi-stakeholder dialogue could therefore provide a more effective platform to align policy-practice-funding discourses for development (Garmendia et al., Citation2016).

Framing investment in GI as a boundary object provides an opportunity to evaluate how stakeholders situate understanding within wider financing discussions. The commentary presented above suggests stakeholders from the public and private sector are locating GI within policies and development programmes supporting their decision-making with economic evidence (Mayor of London, Citation2016). Within the literature, the positioning of GI within strategic thinking is highlighted as significant, as it establishes the framework needed to align the concept with action (Hislop et al., Citation2019). Moreover, commentary in London suggests that the suite of funding options should be seen as a positive, albeit with caveats:

CSR isn’t the panacea for all ills, but it is opening up a lot more [opportunities for investment in GI] … I wouldn’t necessarily say it’s a bleak picture out there, because I think there are still funds, there are still partners that want to fund [GI] … we’ll ride the storm but not without the impact its already had on streamlining the team and you have to make sure there is enough work. (ENVS5)

One significant aspect of this debate is the acknowledgement that a mosaic of funding mechanism is needed to meet the costs of GI (Vandermeulen et al., Citation2011). Approaching financing from a broader perspective reduces dependency of a single source providing organisations with opportunities to proactively develop public, private and environmental/community collaborations (Mell, Citation2018). Such an approach could be linked to strategic policy promoting, for example, climate change adaptation in Philadelphia (Philadelphia Water Department, Citation2011), and can be used to shape political support. Moreover, the diversification of funding portfolios for strategic development helps establish a validity for GI by locating it within wider infrastructure debates.

In addition, there has been a foregrounding of BIDS as significant advocates in funding GI. By acting as conduits for the business community, BIDs hold a position of trust or ‘GI champions’ within development debates (Jones & Somper, Citation2014). BIDs in London have thus extending their economic remit to establish GI as a comparable resource to grey infrastructure enabling the aesthetic and ecological quality of the physical environment to be prioritised, although benefits remain localised (De Magalhães, Citation2012). BIDS are potentially positioned as holding greater prominence compared to CSR due to their directed organisational tenure within their respective communities. Furthermore, it is unclear whether CSR illustrates a transition to more sustainable practice or a ‘greenwashing’ to meet sustainability targets. BIDs, however, are committed to support their business communities and use GI as a strategic mechanism to promote growth.

The analysis presented in this paper illustrates the complex yet complimentary set of options available to fund GI. These reflect ‘traditional normative’ funders but place greater emphasis on ‘traditional alternatives’ and ‘contemporary alternatives’ to meet shortfalls. This reinforces elements of the research literature which considers Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) and community/environment sector-led funding as being as important as traditional approaches (Neal, Citation2013). The ability of these alternatives to address variation in LPA and government funding remains challenging and is undermining GI delivery in some locations. London, however, is presented as being more adaptable due to the expertise embedded within its natural and built environment professionals (Mayor of London, Citation2016). Practitioners in Paris, Milan and Berlin have engaged with a comparable transition illustrating the benefits of multi-stakeholder partnerships (Davies & Lafortezza, Citation2017; Lachmund, Citation2013; Mell, Citation2016).

It would, however, be remiss to suggest that the development of a consensus between stakeholders in support of GI has been straightforward. As noted, concerns related to economic viability, timescales, and long-term management all remain. However, as GI has become established in London via GLA policy, practice-based evidence, and the economic analysis of developers, we can identify a confluence of agreement regarding the benefits of investing in GI. This has, in effect, positioned GI as a boundary object that stakeholders have coalesced around. To achieve this stakeholders have promoted the added-value that GI can deliver in diverse development situations addressing financial short-termism and a lack of knowledge through cross-sectoral discussions.

This is not coincidental but reflective of a wider engagement with GI in London, as stakeholders have generated an appreciation of economic uplift, societal betterment, and climatic improvements. Additional evidence is therefore needed to ensure that the three funder groups discussed continue to work collaboratively to address sectoral shortfalls. This reinforces the pressure placed on LPAs, landowners and developers to maximise their returns on investment (Matthews et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, not all LPAs in London have substantial land holdings suitable for development, and therefore require bespoke financial arrangements that engage potential stakeholders (Mell, Citation2020). This is critical, as no single funding stream was considered sustainable in perpetuity, and thus a suite of options would be more resilient to change. Evidence from other European cities (see Davies & Lafortezza, Citation2017) highlight comparable challenges, however, it was suggested that the growing consensus of support for GI in London is a reaction to knowledge sharing promoting GI within strategic and project-based development activities. This, as discussed above, was considered part of a longer term strategy to meet institutional objectives and ensure GI delivery (De Magalhães, Citation2012; Firehock, Citation2015). Thus, a quid pro quo of trade-offs is evident whereby alternative funders have bridged existing approaches to meet their needs whilst ensuring institutional support can be maintained (Campbell, Citation1996). Analysis also suggests that GI has gained prominence due to its ability to deliver higher economic returns with the evidence of Vivid Economics and Barton Willmore (Citation2020) and Grosvenor’s (Citation2015) Living Cities agenda showing a successful alignment of economic value with arguments ‘selling’ environmental to investors.

Conclusion

A multi-faceted approach to investment in GI engaging issues of infrastructure development, access to nature, and reactions to climate change is increasingly visible in London. Stakeholders should though be aware that a homogenous approach to GI investment is not viable in London, the wider UK or internationally. Alternatively, there is a need to consider GI as offering multiple benefits to London’s environment, its economy and its population. However, stakeholders from across the natural and built environment need to effectively communicate these messages by working across disciplinary boundaries. Engaging with the evidence base examining the economic value of GI holds an important role in this process and can act as a bridge between stakeholders. Evidence alone will not shift the focus of development to GI. Although the GLA seems best placed to drive this agenda their lack of authority to deliver change requires them to generate support from LPAs, environmental groups, and developers to ensure that the economic, socio-cultural and ecological benefits of GI are delivered. Moreover, by accepting that traditional and traditional alternative funding streams can, and should, be aligned with contemporary alternatives, a more resilient suite of options that proactively address issues of project focus, scale, and economic return become attainable.

Acknowledgements

All data collection conforms to University of Manchester ethical approval regulations including approval via its Ethical Approval Decision-Making Tool. All participants gave informed consent, via anonymised reporting, to be used in public forums/publications. Names/organisations have been anonymised accordingly.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ian Mell

Ian Mell is a Reader in Environmental & Landscape Planning at the University of Manchester. His research focusses on the intersection of policy, practice and funding for Green Infrastructure. This examines the role of alternative funders, forms of urban greening, and policy evaluations in the development of more sustainable urban locations in the UK and internationally. His work has been funded by the EU Horizon 2020 Programme, Defra, Natural England and the Newton Fund.

Notes

1 The third sector refers to organisations comprising non-governmental and non-profit organizations including charities, volunteer groups and cooperatives.

2 Business Improvement Districts (BIDs) are a vehicle for coordinating business-led responses to the needs of a defined area/geographical boundary, and are funded via mandatory business subscriptions. Each BID is established via a ballot and are subject to renewal every five years. London has 51 BIDs split between those with a high-street/town centre focus (N:44) and those focussing on industrial areas (N:7). The first BID in London was established in 2005 and the most recent was established in 2016. BIDs in London receive an average of £24.9 million total income from their business levies, work with over 61,000 companies (with 905,000+ employees). Although limited in size their roles include promoting promotion dialogues between local businesses, the GLA/LPAs and other organisations to enhance economic, social and environmental opportunities (Future of London and Rocket Science Citation2016). This mediation role is critical to the success of BIDs, as act as conduits between the strategic objectives of the GLA and LPAs, and the delivery of economic opportunity for local businesses.

3 London comprises 33 administrative bodies all of whom hold various land holdings, capital/revenue reserves and have different socio-economic profiles.

4 Colour in this instance refers to the political allegiance of each borough. Those considered blue would be controlled by the centre-right Conservative party and those labelled red the centre-left/left Labour party.

References

- Anguelovski, I., Connolly, J. J. T., Masip, L., & Pearsall, H. (2018). Assessing green gentrification in historically disenfranchised neighborhoods: A longitudinal and spatial analysis of Barcelona. Urban Geography, 39(3), 458–491. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2017.1349987

- Baggio, J. A., Brown, K., & Hellebrandt, D. (2015). Boundary object or bridging concept? A citation network analysis of resilience. Ecology and Society, 20(2), 2. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07484-200202

- Brand, F., & Jax, K. (2007). Focusing the meaning(s) of resilience: Resilience as a descriptive concept and a boundary object. Ecology and Society, 12(1), 23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-02029-120123

- Calvert, T., Sinnett, D., Smith, N., Jerome, G., Burgess, S., & King, L. (2018, October 20). Setting the standard for green infrastructure: The need for, and features of, a benchmark in England. Planning Practice and Research. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2018.1531580

- Campbell, S. (1996). Green Cities, Growing Cities, Just Cities?: Urban Planning and the Contradictions of Sustainable Development. Journal of the American Planning Association, 62(3), 296–312.

- Davies, C., & Lafortezza, R. (2017). Urban green infrastructure in Europe: Is greenspace planning and policy compliant? Land Use Policy, 69, 93–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.08.018

- De Magalhães, C. (2012). Business Improvement Districts and the recession: Implications for public realm governance and management in England. Progress in Planning, 77(4), 143–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2012.03.002

- Dornelles, A. Z., Boyd, E., Nunes, R. J., Asquith, M., Boonstra, W. J., Delabre, I., Denney, J. M., Grimm, V., Jentsch, A., Nicholas, K. A., & Schröter, M. (2020). Towards a bridging concept for undesirable resilience in social-ecological systems. Global Sustainability, 3, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2020.15

- Firehock, K. (2015). Strategic green infrastructure planning: A multi-scale approach. Island Press.

- Future of London, & Rocket Science. (2016). The evolution of London’s business improvement districts.

- Garmendia, E., Apostolopoulou, E., Adams, W. M., & Bormpoudakis, D. (2016). Biodiversity and green infrastructure in Europe: Boundary object or ecological trap? Land Use Policy, 56, 315–319. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.04.003

- Greater London Authority, The National Trust, & Heritage Lottery Fund. (2017). Natural capital account for public green space in London. https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/11015viv_natural_capital_account_for_london_v7_full_vis.pdf

- Grosvenor. (2015). Living cities: Our approach in practice.

- Hansen, R., & Pauleit, S. (2014). From multifunctionality to multiple ecosystem services? A conceptual framework for multifunctionality in green infrastructure planning for urban areas. Ambio, 43(4), 516–529. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-014-0510-2

- Heink, U., & Kowarik, I. (2010). What are indicators? On the definition of indicators in ecology and environmental planning. Ecological Indicators, 10(3), 584–593. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2009.09.009

- Hislop, M., Scott, A. J., & Corbett, A. (2019). What does good green infrastructure planning policy look like? Developing and testing a policy assessment tool within Central Scotland UK. Planning Theory & Practice, 20(5), 633–655. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2019.1678667.

- Howard, B. (2020). Investment finance for green infrastructure – PERFECT expert paper 6.

- Hudeková, Z., Mederly, P., & Tóth, A. (2019). Green infrastructure – guide for the municipalities. Karlova Ves Municipality.

- Jones, S., & Somper, C. (2014). The role of green infrastructure in climate change adaptation in London. The Geographical Journal, 180(2), 191–196. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12059

- Koc, C. B., Osmond, P., & Peters, A. (2017). Towards a comprehensive green infrastructure typology: A systematic review of approaches, methods and typologies. Urban Ecosystems, 20(1), 15–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-016-0578-5

- Lachmund, J. (2013). Greening Berlin: The co-production of science, politics, and urban nature. MIT Press.

- Liverpool City Council. (2016). Strategic green and open spaces review board: Final report.

- Lowndes, V., & Gardner, A. (2016). Local governance under the conservatives: Super-austerity, devolution and the ‘smarter state’. Local Government Studies, 42(3), 357–375. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2016.1150837

- Matthews, T., Lo, A. Y., & Byrne, J. A. (2015). Reconceptualizing green infrastructure for climate change adaptation: Barriers to adoption and drivers for uptake by spatial planners. Landscape and Urban Planning, 138, 155–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.02.010

- Mayor of London. (2014). London infrastructure plan 2050: A consultation.

- Mayor of London. (2016). The London plan – the spatial development strategy for London consolidated with alterations since 2011. https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/the_london_plan_2016_jan_2017_fix.pdf

- Mayor of London. (2017). Market assessment: Part of the London plan evidence base.

- Mayor of London. (2018). London environment strategy.

- Mayor of London. (2021). The London plan: The strategic development strategy for greater London, March 2021.

- Meerow, S. (2020). The politics of multifunctional green infrastructure planning in New York City. Cities, 100, Article 102621. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102621

- Mell, I. (2018). Financing the future of green infrastructure planning: Alternatives and opportunities in the UK. Landscape Research, 43(6), 751–768. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2017.1390079

- Mell, I. (2020). The impact of austerity on funding green infrastructure: A DPSIR evaluation of the Liverpool green & open space Review (LG&OSR), UK. Land Use Policy, 91, Article 104284. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104284

- Mell, I. C. (2016). Global green infrastructure: Lessons for successful policy-making, investment and management. Routledge.

- Mell, I., & Clement, S. (2020). Progressing green infrastructure planning: Understanding its scalar, temporal, geo-spatial and disciplinary evolution. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 38(6), 449–463. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2019.1617517

- Mell, I., & Whitten, M. (2021). Access to nature in a post Covid-19 world: Opportunities for green infrastructure financing, distribution and equitability in urban planning. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1527. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041527

- Neal, P. (2013). Rethinking parks: Exploring new business models for parks in the 21st century. Nesta.

- Nesta. (2016). Learning to rethink parks.

- New York City Environmental Protection. (2010). NYC green infrastructure plan: A sustainable strategy for clean waterways.

- Payne, S., & Barker, A. (2015). Implementing green infrastructure through residential development in the UK. In D. Sinnett, N. Smith, & S. Burgess (Eds.), Handbook on green infrastructure: Planning, design and implementation (pp. 375–394). Edward Elgar.

- Philadelphia Water Department. (2011). Green city, clean waters: The city of Philadelphia’s program for combined sewer overflow control.

- Raco, M., Durrant, D., & Livingstone, N. (2018). Slow cities, urban politics and the temporalities of planning: Lessons from London. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 36(7), 1176–1194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654418775105

- Raco, M., Livingstone, N., & Durrant, D. (2019). Seeing like an investor: Urban development planning, financialisation, and investors’ perceptions of London as an investment space. European Planning Studies, 27(6), 1064–1082. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1598019

- Reimer, M., & Rusche, K. (2019). Green infrastructure under pressure. A global narrative between regional vision and local implementation. European Planning Studies, 27(8), 1542–1563. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1591346.

- Siemens AG. (2011). Asian green city index: Assessing the environmental performance of Asia’s major cities.

- Smith, A. (2017). Animation or Denigration? Using Urban Public Spaces as Event Venues. Event Management, 21(5), 609–619.

- Tan, P. Y., Wang, J., & Sia, A. (2013). Perspectives on five decades of the urban greening of Singapore. Cities, 32, 24–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2013.02.001

- Tempany, A., & Armour, T. (2020). Nature of the city: Green infrastructure from the ground up. RIBA Publishing.

- Vandermeulen, V., Verspecht, A., Vermeire, B., Van Huylenbroeck, G., & Gellynck, X. (2011). The use of economic valuation to create public support for green infrastructure investments in urban areas. Landscape and Urban Planning, 103(2), 198–206. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.07.010

- Vivid Economics, & Barton Willmore. (2020). Levelling up and building back better through urban green infrastructure: An investment options appraisal. Commissioned by the National Trust on behalf of the partners of the future parks accelerator. National Trust.