ABSTRACT

The recent literature on intermediaries in urban sustainability transitions has studied their role as a translator between innovative niches and incumbent regimes. In urban sustainability transitions, intermediaries from both civil society and public institutions seek to bridge diverging world views and communicate innovative lessons learned back to the incumbent regime. How these intermediaries are embedded in local governance contexts and how the political dynamics inherent to urban sustainability transitions play out remains a research gap. As these transitions require political consensus-building, we explore the interaction between Transition Town Initiatives (TTIs) as niche intermediaries seeking to transform society from below, and regime-based transition intermediaries operating from above. In a comparative study of four German cities, we analyse why and how niche and regime intermediaries build partnerships for urban transitions towards sustainability. While Transition Town Hannover and Bluepingu in Nuremberg have successfully established partnerships with the municipalities, Transition Town Göttingen and Transition Town Kassel have struggled in their efforts to do so. These differences can be explained by the interactions between structural conditions, political priorities and institution-building, as well as the proficiency of transition intermediaries.

1. Introduction

As socio-ecological challenges like resource scarcity, climate change and the financial crisis raise growing concern, the transition town movement emerged as a grassroots movement in the UK in 2006 to promote a transition towards sustainability from the bottom-up. It aims to counter the traditional development pathway of economic growth, consumerism and resource depletion by instead focussing on post-growth, sufficiency and resource protection (Feola & Nunes, Citation2014; Frantzeskaki et al., Citation2016; Henfrey & Kenrick, Citation2017; Hopkins, Citation2013; Kenis & Mathijs, Citation2014; Leach et al., Citation2013; Maschkowski & Wanner, Citation2014). Being a socio-ecological movement, the transition town movement seeks to develop socio-ecological innovations such as urban gardening, repair cafés, models for the sharing and circular economy, or local currencies to promote resilience and sufficiency. It defines local communities as the key locus for transformative change, viewing them as the places where both the sources of environmental degradation and solutions for environmental protection are to be found. In seeking to rebuild and transform cities, transition town initiatives (henceforth: TTIs) act not just as intermediaries between social-ecological initiatives but also between civil society and local governments.

In the literature on sustainability transitions, the role of such intermediaries has received increasing scholarly attention (Kivimaa, Boon, et al., Citation2019). Scholars have analysed intermediaries as systemic intermediaries, which form building blocks for innovation systems (van Lente et al., Citation2003, Citation2011, Citation2020), and sought to integrate intermediary functions in the Technological Innovation System (TIS) framework (Lukkarinen et al., Citation2018). Investigations into the role of intermediaries in niche development have shown how they connect local experiments with global niches and contribute to diffusing grassroots innovations through replication, up-scaling and translation (Boyer, Citation2018; Geels & Deuten, Citation2006; Hargreaves et al., Citation2013). The notion of innovation intermediaries is rooted in management studies, specifically the concept of knowledge brokers (Hargadon, Citation2002). Various authors have attempted to bridge these concepts of innovation intermediaries in order to explain how actors and platforms facilitate transitions in particular domains such as housing (Martiskainen & Kivimaa, Citation2018).

Sustainability transitions ‘are deeply and unavoidably political’ (Patterson et al., Citation2017, p. 2), because they challenge existing values and socio-economic positions (Castán Broto, Citation2017; Ehnert, Kern, et al., Citation2018; Köhler et al., Citation2019; Meadowcroft, Citation2009, Citation2011; Miller & Levenda, Citation2017; Shove & Walker, Citation2007). Consequently, Patterson et al. argue that governance and politics should be placed at the centre of research on sustainability transitions (Citation2017). However, how transition intermediaries are embedded in local governance contexts and how the political dynamics inherent to urban sustainability transitions play out remains a research gap (Kivimaa, Boon, et al., Citation2019, p. 1073). In light of the political nature of transitions, it is to be explored how intermediaries pave the way for change by advancing sustainability discourses, configuring and aligning the perspectives and interests of actors, and mediating tensions. Defined by their ‘in-betweenness’ (Moss, Citation2011, p. 18), it is to be studied how intermediaries build bridges between innovative niches and established regimes. This should provide a basis for reflecting on how the roles and functions of intermediaries contribute to transition mechanisms like up-scaling, partnering and embedding, and improve the understanding of transition dynamics.

Previous studies have elaborated the role of intermediaries in the context of multi-level governance, where they connect and translate between different governance levels (Beveridge & Guy, Citation2009). Scholars have analysed how intermediaries shape urban-rural relationships (Kovach & Kristof, Citation2009) and how they act as translators between scientists, policymakers and spatial planners (Scott & Harvey, Citation2016). In particular, Mignon and Kanda developed a typology of intermediaries to explicate their relevance for policy design (Mignon & Kanda, Citation2018).

A literature on intermediaries in urban sustainability transitions is gradually emerging. It shows how local intermediaries develop visions for sustainable cities and translate these visions to local actors (Hamann & April, Citation2013; Hodson & Marvin, Citation2009, Citation2010, Citation2011, Citation2012; Hodson et al., Citation2013). These intermediaries are facilitators of social learning processes, thereby engendering transformative change (Wolfram, Citation2019). The literature also elaborates how local authorities act as regime-based transition intermediaries (henceforth: regime intermediaries), promoting sustainability transitions within established institutions and introducing innovative governance approaches such as urban experimentation (Fudge et al., Citation2016; Mukhtar-Landgren et al., Citation2019; Sovacool et al., Citation2020). Hodson et al. framed these roles and functions as ‘urban intermediary governance’ (Citation2013).

In urban politics, the complexities of modern societal problems have increased the interdependence of local governments and non-state actors. This has led to a shift from hierarchical government to multi-layered governance involving a plurality of public and private actors (Castán Broto, Citation2017; Hajer et al., Citation2015; Khan, Citation2013; Lowndes, Citation2009). Governance alters the role of state authorities, who become moderators and facilitators in addition to their traditional roles of regulators and implementers (Castán Broto, Citation2017; Geels et al., Citation2019; Khan, Citation2013). Against this backdrop, networks and partnerships have gained in importance. This raises the question of how such partnerships emerge. In this study, we explore the interaction between TTIs as niche intermediaries seeking to transform society from below, and regime-based transition intermediaries operating from above. We compare the dynamics of their collaboration in four German cities: Hannover, Nuremberg, Göttingen and Kassel.

Here we wish to illustrate the embeddedness of these niche and regime intermediaries in local governance settings. The research questions pursued in this comparative study are the following:

Why and how do niche and regime intermediaries build partnerships for urban transitions towards sustainability?

How do local governance settings support or hinder the collaboration between TTIs and local governments?

In the theory section, we outline conceptions of transition intermediaries and introduce an integrative perspective on intermediaries and the building of partnerships. Subsequently, we describe the comparative case study design and present the empirical evidence on the building of partnerships for urban transitions. Adopting a multi-causal approach, we discuss how urban contexts, the interaction between intermediaries and the roles of individuals account for the different dynamics in the four cities. We conclude by proposing avenues for future research.

2. Transition intermediaries and the building of partnerships for urban sustainability transitions

As pointed out by Smith, transformative dynamics arise from contradictions within the incumbent regime (Citation2007). These tensions can lead to a search for new solutions to existing problems, often triggering conflicts between change agents and incumbent actors seeking to preserve the status quo. Transformative change requires a translation between these innovative ideas and established practices, as well as between the different logics of action of state and non-state actors. Therefore, transition intermediaries play a key role as networkers, translators and conflict mediators. By bridging different worldviews, translation can help to mediate conflicts between change agents and incumbents.

In transition research, there is no agreed definition on what constitutes an intermediary (Kivimaa, Boon, et al., Citation2019; Moss et al., Citation2011). Following a relational understanding, intermediaries are not defined by their institutional form but through the relations, they are embedded in. In the context of transition research, they are referred to as ‘transition intermediaries’ as they develop visions to transform socio-technical systems and establish networks of change agents (Kivimaa, Boon, et al., Citation2019; Marvin et al., Citation2011). We define these intermediaries not as neutral brokers but as co-creators of knowledge: They do not transfer knowledge in a neutral manner, but shape and broaden knowledge in the process of translation and mediation (Geels & Deuten, Citation2006; Hodson et al., Citation2013; Matschoss & Heiskanen, Citation2017; Medd & Marvin, Citation2008; Moss et al., Citation2011; Smith et al., Citation2016). They can be state or non-state actors as well as individuals or organisations (Fischer & Newig, Citation2016; Hargreaves et al., Citation2013; Kivimaa & Martiskainen, Citation2018).

Reviewing the literature on intermediaries in sustainability transitions, Kivimaa, Boon, et al. (Citation2019) find that most studies of intermediaries are grounded in the multi-level perspective (MLP) and strategic niche management (SNM) rather than the concepts of technological innovation systems or transition management. The MLP captures the transformation of socio-technical systems through the alignment and re-alignment of three levels: niches as micro-level spaces in which innovations emerge, regimes as incumbent and relatively stable technologies, practices and institutions, and landscapes as developments in the exogenous environment (Geels, Citation2005; Rip & Kemp, Citation1998). Kivimaa, Boon, et al. (Citation2019) therefore build on niches and regimes as defining concepts when developing their typology of transition intermediaries. They distinguish between systemic intermediaries, regime-based transition intermediaries, niche intermediaries, process intermediaries and user intermediaries. These intermediaries promote transitions on two levels: the creation of niches that alter the mainstream and the destabilising and dismantling of incumbent regimes (Kivimaa, Citation2014; Matschoss & Heiskanen, Citation2017). In our study of partnerships between TTIs and municipalities, we focus on niche intermediaries and regime-based transition intermediaries:

Regime-based transition intermediaries (henceforth: regime intermediaries) are linked to incumbent socio-technical regimes through institutions or interests (Berkvist & Söderholm, Citation2011; Hodson et al., Citation2013; Parag & Janda, Citation2014; Polzin et al., Citation2016; Sovacool et al., Citation2020). They are given a specific mandate to promote change towards sustainability by dominant regime actors. In other words, they are officially empowered to transform the regime. Transition intermediaries can act either as revolutionaries or reformers. While revolutionaries endorse political activism, reformers pursue fundamental change through incremental steps (Hargreaves et al., Citation2013). Regime intermediaries typically tend more towards a reformist approach. Given their in-depth knowledge of complex policy environments, they have a pivotal role in translating new frameworks and disruptive policies into established institutions (Fischer & Guy, Citation2009; Moss, Citation2009). These regime intermediaries can be government agencies, business networks or professional associations. They might be organisations like agencies, organisational units like administrative departments or individuals like mayors or public officials. For example, the Greater Manchester Climate Change Agency, mandated to foster transitions towards a low-carbon society, acted as an intermediary between national and sub-national actors (Hodson & Marvin, Citation2012). In Finland, the government-owned energy company Motiva supported the collaboration between renewable energy associations and heat entrepreneurs (Kivimaa, Citation2014).

Niche intermediaries experiment within a particular niche (Geels & Deuten, Citation2006; Hamann & April, Citation2013; Hargreaves et al., Citation2013; Martiskainen, Citation2017; Seyfang et al., Citation2014; Smith et al., Citation2016). They act as an intermediary between the particular niche and the established regime. Niche intermediaries seek to aggregate knowledge and resources while providing a shared infrastructure for like-minded projects (Geels & Deuten, Citation2006). Further, they support learning by sharing lessons learned and guide the development of new niches (Hargreaves et al., Citation2013). Examples of niche intermediaries are the UK community energy initiatives (Seyfang et al., Citation2014). In urban agriculture, the Brighton and Hove Food Partnership (UK) advocated for resource allocation and land for communal growing activities (White & Stirling, Citation2013).

In sustainability transitions research, different roles and activities of transition intermediaries in niche development are outlined. They build on earlier research on boundary work and boundary spanning (Aldrich & Herker, Citation1977; Fennell & Alexander, Citation1987; Jerneck & Olsson, Citation2011), which describes boundary spanners as ‘knowledgeable information brokers’, ‘well-connected bridge builders’ or ‘flexible organisational navigators’ (Miller, Citation2009). Focusing on systemic intermediaries, van Lente et al. discern three main roles and functions of intermediaries (Citation2003, Citation2011, Citation2020):

the articulation of options and demand by raising awareness of possible futures and supporting strategy development

the alignment of actors and possibilities by strengthening the linkages between the elements of an innovation system, building networks and facilitating interfaces

the support of learning processes by fostering feedback mechanisms and stimulating experiments.

Following the idea of SNM, whereby intermediaries connect local projects and initiatives with the building of a global niche for transitions (Geels & Deuten, Citation2006), Hargreaves et al. (Citation2013) characterise their roles as the aggregation of knowledge from diverse sources, the creation of a shared institutional infrastructure, the coordination and framing of local-level action, and the brokering and managing of partnerships. In a similar vein, Kivimaa (Citation2014) depicts these roles as articulating expectations and visions to advance sustainability aims, building social networks to configure and align interests, and facilitating learning processes to gather knowledge and generate new insights. Moss et al. structure the diverse roles and activities of intermediaries as ‘(1) bridge-builders, mediators, go-betweens, or brokers, facilitating dialogues, resolving conflicts, or building partnerships, (2) “info-mediaries”, disseminating information, offering training, and providing technical support, (3) advocates, lobbyists, campaigners, gatekeepers, or image-makers, fighting for particular causes, and (4) commercial pioneers, innovators, and “eco-preneurs”’ (Citation2009, p. 22). Building on these conceptions, we propose the following roles and functions of transition intermediaries:

Envisioning and articulating needs and expectations for change: articulating needs, expectations and requirements for change; developing a wider vision of the transformation of society; advancing sustainability and alternative discourses on development pathways; translating a vision to local stakeholders

Aggregating knowledge and facilitating learning processes: generating and disseminating knowledge; aggregating knowledge from diverse sources and local projects, and sharing the lessons learned; encouraging processes of learning and experimenting by enhancing feedback mechanisms and learning-by-doing; providing education and training

Creating a shared institutional infrastructure: creating an institutional infrastructure and support by connecting local projects; providing a repository or forum for the storage and exchange of knowledge between local projects; introducing new markets for innovative products and services

Framing and coordinating local-level activities: identifying common challenges encountered across local projects; coordinating and framing subsequent local action by sharing this knowledge

Networking, building partnerships, aligning interests and resolving conflicts: building networks, facilitating dialogue, resolving conflicts and brokering agreement; aligning actors and their interests; building trust; building bridges through the translation between public, private and civil society actors

Advocating change and mobilising support: advocating political reform; mobilising interests and support; lobbying and campaigning; navigating complex and changing policy environments and identifying windows of opportunity.

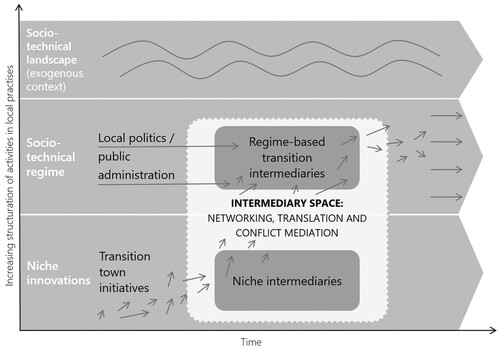

Both the TTIs and representatives of local politics and administrations can act as intermediaries between public, private and civil society actors. TTIs are defined as niche intermediaries who aim to develop sustainable niches within local communities. They seek to expand niches through experimentation, to aggregate and transfer knowledge, to establish collective infrastructures for social-ecological initiatives, to coordinate their activities and establish partnerships with local governments. In a similar vein, agents within local politics and public administrations can act as regime intermediaries. While they have an official mandate to initiate and accelerate sustainability transitions, they are often affiliated to the established regime. This intermediary space, bridging niche and regime intermediaries, is depicted in .

Figure 1. The research subject of the interaction between niche and regime-based transition intermediaries in the intermediary space.

Studying transition intermediaries in urban transitions, we seek to show how they are embedded in local structural and institutional contexts. We, therefore, integrate these governance settings in our conceptual framework to explain the emergence of partnerships between niche and regime intermediaries. The dynamics of urban governance have been studied from a structural (the macro-level), an institutional (the meso-level) and an agency perspective (the micro-level) (DiGaetano & Strom, Citation2003). While each of these perspectives is of explanatory value, they fail to account for the complex dynamics of urban governance. Various authors have shown how structures, institutions and agents co-constitute one another (DiGaetano & Strom, Citation2003; Giddens, Citation1984; Lowndes, Citation2009; Schmidt, Citation2008). While agents are embedded within and shaped by structural and institutional contexts, they can also reflect upon, redefine and reshape these structures and institutions. DiGaetano and Strom have argued that only an integrative framework is able to capture the relationships between structures, institutions and agents, and thus create a holistic picture of urban governance (Citation2003).

Structural approaches define political life by the distribution of material resources. They illustrate how social and economic relations influence political processes. Institutional approaches, on the other hand, view institutions as central components of political life (Peters, Citation2005). These institutions can be both formal and informal in nature. As some scholars have pointed out, informal conventions can be just as important as formal constitutions in shaping political processes (DiGaetano & Strom, Citation2003; Lowndes, Citation2009). The new institutionalism, which arose in the 1980s, argues that values, symbols and beliefs give meaning to political life (March & Olsen, Citation1984, Citation1989). These are captured in the notion of political culture. Agency approaches study ‘how and why individuals act as they do’ and how these actions affect policymaking (DiGaetano & Strom, Citation2003, p. 362). Adopting this integrative perspective, we study structures as urban contexts, institutional relationships as interactions between intermediaries and agency as the roles of individuals, and explore their interactions in the building of partnerships between niche and regime intermediaries.

3. Research methodology

3.1. The comparative case study design

The form of our comparative case study is an ‘embedded multiple-case design’ (Yin, Citation2009). The cities are the cases and the transition intermediaries the ‘embedded units of analysis’. Both the cases and the units of analysis are embedded in a multi-level governance context. As we are studying niche and regime intermediaries in four German cities, this multi-level governance context is the same in all four cases, whereas the local governance settings vary. The selection of the cases was based on theoretical sampling (Eisenhardt, Citation1989). We conducted desktop research, reviewing websites and reports by TTIs, and scoping interviews with members of the German Transition Network and several TTIs to gain information on their activities and partnerships with municipalities. Based on these scoping interviews, we selected the four cases.

All TTIs share the vision of building resilient and sustainable cities and shifting lifestyles from consumerism to sustainability. Within the cities, the TTIs create niches to develop socio-ecological innovations, make sustainable development pathways visible and advance alternative discourses. With their emerging novelties, they challenge established regimes as the dominant socio-technical configuration within cities. The municipalities form part of these dominant and stable institutions, routines and cultures (see ).

Seeking to compare diverse types, we chose two TTIs which have created a high bottom-up dynamic and have successfully established partnerships with their municipalities, and two TTIs which have also created a bottom-up dynamic but struggled to establish such partnerships. The first two are Transition Town Hannover (TT Hannover) and Bluepingu in Nuremberg, while the second two are Transition Town Göttingen (TT Göttingen) and Transition Town Kassel (TT Kassel) (see Appendix 1). In Hannover, sustainable development is a political priority of the city council, which officially resolved to implement the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2016. Founded in 2010 and developing a broad range of initiatives and projects, TT Hannover has become an established cooperation partner of the City of Hannover. Similar to Hannover, sustainable development is a priority for the City of Nuremberg. It has been awarded as Sustainable Metropolis in 2016. Furthermore, an ecological business sector has emerged in Nuremberg over the past two decades. Due to its political advocacy and its strong commitment, Bluepingu (founded in 2008) has become an established partner of the City of Nuremberg. In contrast, the City of Göttingen focuses its action on sustainable development mainly on climate protection. Formed in 2010, TT Göttingen primarily seeks to advance its own projects and cooperates with the City of Göttingen only to a limited extent. In Kassel, there is no strong vote for sustainable development in the city council as the Green Party remains junior partner in the governing coalition with the social democrats. Moreover, a phase of austerity politics between 2012 and 2017 considerably limited the municipality’s room to manoeuvre. TT Kassel was officially founded in 2011. As the Edible City evolved into the strongest initiative among its projects, it also developed the strongest partnership with the City of Kassel. While TT Kassel seeks to strengthen the cooperation with the municipality, it often encounters difficulties.

3.2. Methods of data collection and analysis

Following the idea of triangulation, we combined several methods of data collection (Denzin, Citation1970). In order to map the local governance contexts, we conducted desk research and document analysis. Subsequently, we conducted semi-structured interviews with three groups of interviewees: members of the TTIs, local politicians and public officials, as well as cooperation partners or external observers of TTIs (see Appendix 2). Deriving qualitative categories from the conceptual framework, we applied qualitative content analysis to process the interview data (Mayring, Citation2003). These qualitative categories included the ways of thinking, doing and organising of niche and regime intermediaries:

culture (ways of thinking): normative frames and values; visions for future urban development

practice (ways of doing): political activism versus an incremental, reform-oriented approach; societal change from below versus societal change from above; political advocacy versus an apolitical approach; hierarchical, top-down steering versus a participatory, bottom-up approach; experimentation versus risk aversion

structure (ways of organising): flexible and informal versus formal; departmentalised versus horizontal, cross-domain structures

The roles of intermediaries were captured through first-order and second-order learning, the creation of common infrastructures, the coordination of activities, networking, translation and conflict mediation, and advocating for change. After analysing each case (the within-case analysis), we proceeded with the cross-case analysis, searching for cross-case patterns.

4. Building partnerships for urban sustainability transitions

In analysing the interactions of TTIs with the municipalities of Hannover, Nuremberg, Göttingen and Kassel, we aim to explore why and how partnerships are established to advance urban sustainability transitions. Following the argument of DiGaetano and Strom, we adopt an integrative perspective (Citation2003). Building on the explanatory factors of urban contexts, interactions between intermediaries and roles of individuals, we intend to elucidate how intermediaries are embedded in local structural and institutional contexts and which roles they adopt in facilitating local partnerships.

4.1. Hannover: dialogue and contestation

Founded in 2010, TT Hannover has developed a broad range of activities and projects addressing themes such as energy, urban agriculture, education, housing or fair trade. Due to this strong commitment, it has become a cooperation partner of the City of Hannover.

4.1.1. Urban context

Hannover, which is the capital of Lower Saxony, has a population of about 533,000. After previously undergoing a process of economic restructuring from heavy industry to the service sector, a phase accompanied by unemployment, the city’s local economy has recovered in recent years (HN-5).

4.1.2. Interactions between intermediaries

In their quest to build partnerships and transform society, both TT Hannover (as a niche intermediary) and local politicians or public officials (as regime intermediaries) are confronted with diverging value orientations and have to align different actors and interests. Specifically, this is the conflict between growth and consumerism as dominant frames of contemporary society, on the one hand, and the paradigm change towards post-growth and sufficiency envisioned by the TTIs (HN-2; HN-4; HN-6), on the other. The impact of these different value orientations is exemplified in the domain of mobility in Hannover. Here, the frame of a car-friendly city clashes with that of a car-free city. The ideal of the car-friendly city is inscribed in the city’s current mobility infrastructure, creating path dependencies that are difficult to overcome. The planning of urban mobility infrastructure is a subject of policymaking, so that both TT Hannover and the municipality require political backing to alter these infrastructures. Currently, the issue of mobility is highly politicised, with car-drivers, cyclists and pedestrians arguing around the redistribution of public space (HN-5). TT Hannover seeks to encourage learning and experimentation with cargo bikes and bike-sharing projects to facilitate learning-by-doing while avoiding the conflicts surrounding the breakdown of the old regime and the redistribution of space.

In building a partnership, TT Hannover and the municipality face the challenge of translating between different informal conventions and logics of appropriateness. These are the logics of innovativeness and informality versus conformity and formality. While the municipal authorities seek to preserve established institutions and implement existing regulations, TT Hannover wishes to challenge and change these very institutions. Therefore, the risk aversion of the public administration is seen to clash with the experimentation and innovativeness of the TTI (HN-1; HN-4; HN-6; HN-7; HN-8).

Furthermore, there is a problem of translating between the technical specialisation of the public administration and the horizontal themes of sustainability, which are promoted by TT Hannover. Inherent to this specialisation is the tension between expertise and effectiveness (Dimitrov et al., Citation2006). On the one hand, public administrations have to make well-founded, expert-based decisions, while on the other they have to ensure effective decision-making. This narrow technical focus makes it difficult for TT Hannover to fit horizontal themes into specialised departments. Against this backdrop, the institutionalisation of a regime intermediary for sustainable urban development provides an important entry point for TT Hannover. Here we can highlight the Agenda 21 Office set up by the municipality in 1996, and subsequently expanded into an Agenda 21 and Sustainability Office in 2013 (HN-7). Previously affiliated with the environmental department, it is now a horizontal unit. By adopting multiple intermediary roles, it facilitates cooperation between TT Hannover and the municipality. By developing a reporting system on urban sustainable development for the city administration, it aggregates knowledge on sustainability in various local domains. By organising various dialogue forums such as an agenda plenum or a volunteer network, it creates a shared institutional infrastructure to facilitate the knowledge exchange between local initiatives, helps to frame and coordinate local-level activities and build new partnerships. These dialogue forums provide a space for civil society initiatives to envision and explore alternative policy pathways to transform society (HN-4; HN-6; HN-7).

The economic and environmental departments provide institutional support by maintaining a fund for local initiatives, which supports TT Hannover with annual funding (HN-1; HN-4; HN-7). This funding is not project-based but institutional, supporting the initiative with financial help for staff and rents. This reduces the pressure of ‘projectification’, whereby civil society initiatives have to constantly seek new funding (Borgström et al., Citation2016; Ehnert, Frantzeskaki, et al., Citation2018; Seyfang & Smith, Citation2007).

4.1.3. Roles of individuals

TT Hannover deliberately adopts a constructive attitude, striving to find solutions to environmental and social challenges (HN-1; HN-4). This constructive approach enables it to act as a translator and mediator between civil society and public institutions. By implementing sustainable projects, TT Hannover aims to make alternative options visible (envisioning) and facilitate learning processes by translating abstract visions of sustainable communities into tangible solutions (HN-2). In so doing, it wishes to avoid overwhelming the municipality with abstract conceptions of systemic change and instead translates its normative ideals into visible action. In a similar vein, it supports learning by adapting its mode of public communication, rejecting the cognitive level of environmental awareness (second-order learning) to speak to the practical level of sustainable doing (first-order learning). By experimenting with novel ideas, it seeks to illustrate sustainable lifestyles. These experiments are communicated via visualisation and haptic techniques (Seyfang & Haxeltine, Citation2012; HN-4). Examples are projects for sustainable urban agriculture, sustainable transport through cargo bikes or sustainable housing in eco-efficient quarters.

The spiritus movens of TT Hannover is its initiator. Being a person with a strategic view of the transformation of society at large, he articulates visions and expectations of change, and seeks to advocate reform and mobilise political support (HN-4; HN-7). Speaking the languages of different actors, he is particularly suited to the role of mediator and translator, bridging and aligning different actors and their interests. Given his academic background, he is highly proficient in the acquisition of institutional support and project funding (HN-3; HN-7), helping TT Hannover raise considerable external funds, for instance from the National Climate Initiative of the federal environment ministry (HN-1; HN-4; HN-7). This has enabled TT Hannover to expand its activities and become acknowledged as a legitimate partner by the municipality.

TT Hannover is a strong political advocate, navigating the complex policy environment to identify windows of opportunity to integrate and implement its projects and mobilise support from political parties or public officials (HN-1). Its members participate in thematic dialogue forums run by the municipality, airing their views on sustainable urban planning and related subjects. Referring to the approach of transition management, TT Hannover seeks to build heterogeneous and diverse arenas in order to reach out to society and mobilise wider support (HN-1; HN-6). For example, it organises round tables to discuss its projects such as Sufi.ZEN, a school of sufficiency, or an eco-village, striving to integrate citizens, politicians and public officials in the conception and implementation.

This bottom-up action of TT Hannover as niche intermediary is met with top-down support from local politicians as regime intermediaries. These forces are embedded in a context of multi-level governance. Both niche and regime intermediaries act as intermediaries between these governance levels, creating an impetus for local change. The multiple governance levels define normative principles and provide funding schemes for sustainable urban development. By translating and implementing these objectives in local communities, niche and regime intermediaries frame and coordinate local action. Normative principles are, for example, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) introduced by the United Nations in the agenda ‘Transforming our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’ in 2015. Defining sustainable development as a political priority, the city council of Hannover officially resolved to implement the SDGs in 2016. The council has been run as a coalition of Social Democrats (SPD), the Greens and Liberals (FDP) since 2016.

Given its political support for sustainable development, the City of Hannover received the German Sustainability Award in 2018. The fact that it developed an own policy programme on urban agriculture in 2017 created an entry point for TT Hannover to establish a strong partnership and facilitate dialogue with the municipality to foster urban gardening and the Edible City (HN-1; HN-4; HN-5).

The interaction between institutional contexts and agency is revealed by the manner in which regime intermediaries help to make sense of these policy environments and mobilise political support by directing the regulatory authority and resources of municipalities towards sustainable development. In Hannover, the politician Hans Mönninghoff from the Green Party, who previously headed the city’s environmental department (1989–2013) and economic department (2005–2013), is just such a regime intermediary and political advocate. He paved the way for TT Hannover to collaborate with the municipality and, in particular, to receive institutional funding from the municipality’s fund for civil society initiatives (HN-1; HN-4). He has also supported the initiative’s idea to build an ecovillage to promote sufficiency. This process shows how the regulatory context of urban planning underpins the agency of niche and regime intermediaries. As the envisioned ecovillage project is large in scale, it requires permission and planning assistance from the municipality. Initially, the idea for this unfamiliar and experimental form of living was met with great scepticism by politicians and public officials (HN-1; HN-4). The founder of TT Hannover and the politician Hans Mönninghoff collaborated closely in order to secure municipal support through mobilising allies and campaigning. Together they drafted a concept for the ecovillage, presenting it at public roundtables where it was welcomed by citizens. Finally, they persuaded leading politicians of the project’s merits, and were able to locate a site for the ecovillage in the district of Kronsberg.

4.2. Nuremberg: a closely-knit partnership

Bluepingu, the TTI of Nuremberg, was founded in 2008, thus predating the emergence of the German Transition Network in 2010. It actively promotes themes such as sharing, sustainable consumption and urban agriculture. Due to its political advocacy, Bluepingu has become a well-respected partner of the City of Nuremberg.

4.2.1. Urban context

The Bavarian city of Nuremberg has about 512,000 inhabitants. Over the past decades, it has undergone a process of economic restructuring from industrial production to the service sector (NG-4; NG-5). In particular, an ecological business sector has emerged in Nuremberg, exemplified by BIOFACH, the world’s leading trade fair for organic food, which the city has hosted since 1999 (NG-3; NG-6).

4.2.2. Interactions between intermediaries

Similar to TT Hannover, Bluepingu seeks to promote visions of sustainable and resilient cities (envisioning) and is confronted by conflicting values, namely growth and consumerism versus sustainability and sufficiency, in its quest to build partnerships and transform society (NG-1; NG-4). As in Hannover, the issue of mobility is highly politicised, with car-drivers, cyclists and pedestrians pursuing conflicting aims (NG-2; NG-5). Bluepingu thus seeks to encourage learning and experimentation with cargo bikes and bike sharing in order to translate ideas of sustainable mobility into practice while avoiding the conflicts around the redistribution of public space.

In its interaction with the public administration, Bluepingu also has to bridge the two logics of innovativeness and informality versus conformity and formality. It aligns actors and translates between their logics of action by mediating between its own holistic perspective on sustainability and the technical specialisation of administrative departments. However, with a consensus-seeking culture and a tradition of citizen participation, Nuremberg is somewhat different to the other studied cities (NG-2; NG-4; NG-5). This culture originates in the notion of ‘socio-culture’ introduced by Hermann Glaser, who headed the municipal department of culture and education between 1964 and 1990. The idea of socio-culture is to promote a broad conception of participation, whereby public authorities are expected to establish close links with the citizenry (NG-5). This culture of openness and participation informs the actions of municipal institutions and supports their role as networkers and bridge-builders. For instance, the city has established multiple dialogue forums on fair trade, urban agriculture or biodiversity, facilitating dialogue and the building of partnerships, and enabling Bluepingu to participate in political debates (NG-1; NG-2; NG-6).

Moreover, the Agenda 21 Office (established in 1997 as part of the environmental department) acts as a regime intermediary. It adopts multiple roles, especially networking and building partnerships, framing and coordinating local activities, and creating a shared institutional infrastructure and institutional support for civil society initiatives. It thus organises regular forums on sustainable urban development to promote exchange between politicians, public officials and volunteers (NG-2; NG-3). Further, the office also maintains a fund offering project-based grants to initiatives, of which Bluepingu is a beneficiary (NG-1).

Reflecting Nuremberg’s participatory culture, its institutional setting of urban planning provides many formats for citizen participation. Of particular importance are decentral structures for citizen participation such as working groups for city districts or bureaus for individual quarters, which serve as points of contact for Bluepingu’s projects within particular neighbourhoods and facilitate cooperation (NG-4). One official of the urban planning office (Stadtplanungsamt) acts as an intermediary to these decentral working groups, closing the loop between central and decentral institutions.

4.2.3. Roles of individuals

The driving force behind Bluepingu is its initiator, who promotes a strategic view on societal change and seeks to advance alternative discourses on sustainability. As a strong political advocate, he proactively approaches the municipality (NG-1; NG-2; NG-6). With an academic background, he is proficient in acquiring project funding and creating institutional support. Moreover, he is able to speak the language of diverse actors and, thereby, to align actors and their perspectives.

Similar to TT Hannover, Bluepingu advocates a constructive approach, seeking to contribute to transformative change through action. It aims to translate its abstract visions of change into specific solutions and projects and foster learning processes (NG-1; NG-2; NG-4; NG-6). Against this backdrop, Bluepingu strives to facilitate dialogue and the building of partnerships by viewing the municipality, not as an adversary but a partner, while also differentiating between institutions and individuals. It acknowledges that many individual politicians and public officials support sustainability, whereas political-administrative structures impose cumbersome procedures (NG-1; NG-2; NG-6). This constructive approach helps it in setting up cross-sector collaborations and mediating tensions between actors.

The political advocacy of Bluepingu is supported by the local government, which defines sustainability as a political priority and received the German Sustainability Award in 2016. Nuremberg is governed by a grand coalition of Social Democrats (SPD) and Christian Conservatives (CSU). Referring to the UN agenda ‘Transforming our World’, in 2015, the City of Nuremberg adopted the SDGs as guiding principles for its reporting scheme on sustainable development. Individual regime intermediaries seek to promote this development. Both the head of the environmental department, Peter Pluschke from the Green Party, as well as individual public officials within the department are working to advance sustainability aims and projects such as the EcoMetropolis, the Climate Protection Concept or the reporting scheme on sustainable development (NG-2; NG-6).

In particular, the EcoMetropolis project, which promotes ecological agriculture and local food provision, is strongly supported by the city council and the mayor Ulrich Maly, who are advocating reform and mobilising support (NG-3; NG-4; NG-6). The dynamic development of EcoMetropolis is reinforced by the advocacy of ecological entrepreneurs as well as the historical legacy of urban agriculture in Nuremberg. For example, the Knoblauchsland (the Land of Garlic) is an historical cropland within the confines of the city, making agriculture an established subject of urban policymaking (NG-1; NG-6). Hosting the BIOFACH organic trade fair, ecological entrepreneurs seek to establish organic food and production as a trademark of Nuremberg. Simultaneously, they are lobbying the city council to expand the EcoMetropolis (NG-3; NG-6). Cooperation between the municipal departments, local entrepreneurs and Bluepingu is coordinated by the environmental department through the working group EcoMetropolis (NG-1; NG-3; NG-6). In addition, Bluepingu established a local food council in 2018 (NG-2; NG-3; NG-6). Both working groups support networking and frame and coordinate local activities. Nuremberg’s TTI, however, has struggled to convince the agency in charge of urban green spaces (Servicebetrieb Öffentlicher Raum) to turn public green spaces into ‘edible spaces’. Aiming to secure municipal cooperation and agreement to the idea of the Edible City in public spaces, Bluepingu sought to facilitate learning processes and the sharing of lessons learned by organising an excursion to the Edible City of Andernach. It further encouraged experimentation with local pilot projects for edible spaces (NG-1; NG-2; NG-3; NG-4). This site visit and experimentation can be interpreted as a form of conflict mediation and framing of local action, enabling Bluepingu to explicate the idea of an Edible City. Navigating the policy environment and advocating change, Bluepingu has also attempted to exploit Nuremberg’s application to become the European Capital of Culture 2025 as a window of opportunity to integrate the idea of an Edible City.

The City of Nuremberg interprets the Capital of Culture as a comprehensive process of urban development, specifically to explore what the city of the twenty-first century should be and how transition can be promoted through art and culture (NG-5). The municipal authorities set up a dedicated office for the application process, functioning as a regime intermediary. This establishment of an intermediary office, along with the clear political commitment to a broad understanding of urban development, provided an entry point for Bluepingu. As a key figure, the founder of Bluepingu approached the office to explore avenues for cooperation and building partnerships. As a result, Bluepingu has participated in the open call for the Capital of Culture, proposing the idea of the Edible City, also organising an open air festival for artists and initiatives, the so-called ‘Kulturhauptstädtla’, in summer 2019 in order to show that a transition implies a change in culture. The festival was to make visions of a sustainable future visible (envisioning) and stimulate learning, knowledge exchange and experimenting.

While Hannover, Göttingen and Nuremberg are designated Fair Trade Towns, Bluepingu is the only TTI to have initiated the process of joining the network of Fair Trade Towns. This political advocacy can be directly attributed to its initiator, who has defined fair trade as one of Bluepingu’s priorities. Referring to Nuremberg’s prominent history as the location for the famous post-WWII criminal trials and a city of human rights, he argued that the city should become a Fair Trade Town (NG-1). Bluepingu seeks to mobilise support and advocate change by founding a working group on fair trade with the Agenda 21 Office, by establishing a partnership with the Fair Trade Shops of Nuremberg and by trying to expand the idea of the Fair Trade Town into a Fair Metropolitan Region (NG-1; NG-2; NG-3).

4.3. Göttingen: cautious partners

TT Göttingen was founded in 2010. Its projects focus on sharing, health, repairing, urban agriculture, education and inner transition. Primarily seeking to advance its own projects, TT Göttingen only cooperates with the City of Göttingen to a limited extent.

4.3.1. Urban context

Located in the state of Lower Saxony, Göttingen has a population of approximately 119,000. Given its relatively small population, it has retained the character of a university city with a comparatively younger demography. The economy of Göttingen is characterised by a strong service sector and high-tech industry.

4.3.2. Interactions between intermediaries

Similar to the other examined TTIs, TT Göttingen has to mediate the conflict between the dominant frames of growth and consumerism versus its own ideals of sustainability and sufficiency (envisioning) as it seeks to build new partnerships (GT-5; GT-6). In so doing, it acts as a bridge-builder and translator between conformist, formal public administrations and innovative, informal grassroots initiatives (GT-2; GT-4; GT-5; GT-6).

Unlike the other discussed cities, the City of Göttingen has not established a Local Agenda 21 Office. After drawing up a masterplan on climate protection, it set up the Climate Protection and Energy Unit as a horizontal unit, translating and facilitating cooperation between civil society and administrative departments (GT-4; GT-5). The municipality also introduced an advisory council on climate protection to aggregate and disseminate knowledge and enhance feedback mechanisms, with which TT Göttingen is involved (GT-1; GT-4; GT-5; GT-6).

4.3.3. Roles of individuals

TT Göttingen shares the self-conception of the other TTIs in adopting a constructive attitude and seeking to proactively transform society (GT-2). In particular, it aims to translate the vision of a transition town into concrete local projects in order to support envisioning and learning processes (GT-1; GT-2; GT-6). However, perhaps due to the lack of a guiding figure, TT Göttingen is hesitant about acting as a political advocate. In contrast to the other TTIs, the primary focus of TT Göttingen is on running its own projects rather than seeking cooperation with the municipality (GT-2). It does so only if official permissions are required for the implementation of its projects. Due to the multitude of other socio-ecological initiatives in the city, which already function as political advocates and mobilise political support, it is less important for TT Göttingen to engage in political advocacy.

Compared with TT Hannover and Bluepingu, the members of TT Göttingen struggle to create institutional support as they are less proficient in raising external funding. However, they succeeded in gaining funding for their Terra Preta project (2017–2019) from the National Climate Initiative of the federal environment ministry.

The city council is governed by a coalition of the Social Democratic and Green Parties. Even though the council promotes sustainable policies such as fair trade or the divestment movement (GT-4),Footnote1 TT Göttingen has been unable to find individual regime intermediaries within the municipality to support its aims and establish collaborations. Similar to the other TTIs, TT Göttingen mostly collaborates with the municipality in the promotion of urban gardening. While its members work together with the municipal office for urban green spaces (Fachdienst Grünflächen) to locate potential spaces for urban gardens, TT Göttingen does not pursue the wider agenda of the Edible City (GT-1; GT-3).

4.4. Kassel: a constant search for new avenues of cooperation

Originating in the city’s cultural scene, TT Kassel ran its first projects as part of the documenta exhibition of contemporary art in 2007. It was officially founded in 2011. Today its various projects address diverse themes including urban agriculture, sustainable business models, repairing or sharing. When the Edible City evolved into the most prominent initiative of TT Kassel, this resulted in a strong level of cooperation with the City of Kassel. TT Kassel often encounters difficulties in its constant search for new avenues of cooperation with the municipality.

4.4.1. Urban context

Located in the state of Hesse, Kassel has a population of about 199,000. It is a city of culture, for example hosting the prestigious documenta art exhibition every five years. During the post-war division of Germany, Kassel found itself close to the GDR border. As a result, the city suffered poor economic development and went on to accumulate considerable debt. From 2012 to 2017, the municipal authorities were required to hand over fiscal matters to the state government of Hesse, thereby reducing its debt but leaving it little financial leeway and forcing it to focus on mandatory tasks (KL-3; KL-4; KL-5; KL-6). In the years following Germany’s reunification, the city underwent a process of restructuring and industrial renewal.

4.4.2. Interactions between intermediaries

In introducing discourses on sustainable development pathways and building partnerships, TT Kassel is confronted with the same conflict in values, namely contemporary consumerism versus envisioned sustainability, as the other TTIs (KL-4). In regard to mobility, for instance, its vision of a car-free city challenges the ideal of a car-friendly city (KL-4; KL-6). As in the other discussed cities, public institutions and civil society initiatives are defined by contrasting logics of conformity and innovativeness (KL-2; KL-4; KL-6).

While TT Kassel seeks to establish partnerships with the municipality, it encounters considerable challenges and prolonged decision-making processes within the local administration. These can be attributed to structural constraints arising from the financial problems of the period 2012–2017 as well as the political setting. The city council is governed by a coalition of the SPD and Green Parties. As the Greens are the junior partner in this coalition, there is no strong voice for sustainable development in the city council (KL-4; KL-5). While a Local Agenda 21 Office was founded in 2003, this plays only a marginal role (KL-6). Instead, the so-called Office of the Future (established in 2008 and dissolved in 2018) adopted the role of intermediary, facilitating a dialogue and cooperation. While not enjoying an official mandate to promote sustainable development, this office was responsible for citizen participation, and helped TT Kassel establish contacts with the local administration (KL-2).

The strongest instance of cooperation between TT Kassel and the municipality has evolved between the Edible City project, an initiative of the TTI, and the environmental agency (Umwelt- und Gartenamt). TT Kassel struggled for several years to establish this partnership, beginning with an art project at the documenta exhibition of 2007 as well as guerrilla gardening on public green spaces to demonstrate the idea of urban agriculture and encourage experimenting and learning-by-doing. This illustrates how the TTI originated in Kassel’s cultural scene and used the documenta as a focal point to connect its idea of an Edible City to local discourses and identities. It has now developed a modus operandi with the environmental agency on the planting of edible plants on public green spaces (KL-1; KL-2; KL-5; KL-6). The environmental agency has also adopted the role of a knowledgeable information broker, providing guidance, supporting capacity-building and helping TT Kassel with funding applications, for instance for the National Climate Initiative of the federal environment ministry (KL-1; KL-6). Yet due to the politics of austerity in the period 2012–2017, the environmental agency has found it difficult to hire sufficient staff and develop suitable organisational structures for environmental protection, thereby hindering cooperation with TT Kassel (KL-6). Recently, TT Kassel has been trying to set up a round table on the Edible City with the municipality to support the building of partnerships and coordinate local-level activities. However, this process has stagnated due to the administration’s lack of resources (KL-2).

The so-called ‘citizen councils’ of each city district, which are the decentralised institutions to encourage citizen participation, support cooperation with the municipality by offering TT Kassel funding for its planting campaigns (KL-1). This cooperation with the citizen councils has developed such a momentum that the councils proactively approach the TTI to offer it their support and build new networks.

4.4.3. Roles of individuals

Being its driving force, the founder of TT Kassel develops strategic visions for sustainable and resilient cities (envisioning) and, speaking the language of different actors, acts as a mediator and moderator (KL-1; KL-4). The intermediary role of TT Kassel is supported by its constructive attitude:

[…] we are not against something, but for something. (KL-4)

TT Kassel acts as a strong political advocate (KL-1; KL-2; KL-6). It tries to initiate dialogue forums such as the ‘earth forums’ and ‘frametalks’ developed by the academic and artist Shelley Sacks to support processes of envisioning and learning, and facilitate a dialogue and build consensus between local citizens and the municipality (KL-1). This once again illustrates how TT Kassel seeks to translate its vision of a sustainable city to local citizens by linking it to the context of Kassel as a city of culture. However, TT Kassel has been unable to find individual regime intermediaries within the municipality to support it in building partnerships.

The members of TT Kassel have little experience in applying for external funds and struggle to gain institutional support (KL-3). The project ‘Climate Protection in the East of Kassel’ (2018–2020), funded by the National Climate Initiative, is its first to receive substantial financial support (KL-2). This has helped motivate the municipality to acknowledge TT Kassel as a legitimate partner.

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison of the four cities

Our aim in this comparative study of the interaction between niche and regime intermediaries is to contribute to the debate on intermediaries in urban sustainability transitions. In order to study niche and regime intermediaries as an element of ‘urban intermediary governance’ (Hodson et al., Citation2013), we compared the dynamics of partnership-building for urban transitions towards sustainability in Hannover, Nuremberg, Göttingen and Kassel.

Disparities in the level of cooperation between TTIs and the municipalities can be explained by an integrative framework, which elucidates the interactions between the macro-level of urban contexts, the meso-level of interactions between intermediaries and the micro-level of roles of individuals. At the macro-level, the urban contexts are found to vary. For instance, Kassel faces far more challenging structural conditions than the other three cities. In light of the recent financial squeeze, this municipality has been forced to focus on mandatory tasks and has had little additional capacity to cooperate with civil society initiatives. This underlines the importance of the institutional setting and the German regulatory framework, whereby sustainable urban development is not defined as a mandatory task of the municipalities but remains a voluntary measure.

At the meso-level of interactions between intermediaries, local communities are embedded in a multi-level governance context, opening up opportunities for local transition intermediaries. The UN’s SDGs provide an important reference for the political advocacy of transition intermediaries, while external funding schemes enable TTIs to experiment with sustainable innovations. The TTIs act as mediators and translators between these multiple governance levels by emulating novel approaches and adapting these to local contexts.

The cities differ in the extent of political support for sustainable development, the institutionalisation of regime intermediaries and the participatory culture. Where there is a political willingness to support sustainable urban development, the considerable authority and resources of the municipalities can be redirected accordingly. In contrast to Göttingen and Kassel, the municipal authorities of Hannover and Nuremberg endorse sustainable development, resulting in both receiving the German Sustainability Award. Further, there is widespread political support for an ecological, urban agriculture in Hannover and Nuremberg, which have both developed their own agricultural policies. This has engendered strong partnerships between the TTIs and the municipalities in both cities. In Nuremberg, the dynamic development of the EcoMetropolis is reinforced by local ecological entrepreneurs.

However, we note differences between policy domains and the scale of projects, depending on whether they belong to the public or private sphere. The political support of the city council is a necessary condition for change in some domains as well as for large-scale projects, whereas it is useful but not essential in other domains and for small-scale projects. This can be illustrated by measures in favour of urban agriculture and mobility. For example, while the TTIs can set up urban gardens on private property and fund them solely by private means, they must cooperate with the municipality if the aim is to establish an Edible City on public green spaces. Similarly, while the TTIs can build up a new regime of sustainable mobility by experimenting with cargo bikes or repair shops, the municipalities have authority over the planning of mobility infrastructure. Hence, a breakdown of the old regime and a redistribution of space between car-drivers, cyclists and pedestrians can only be achieved through political advocacy.

Differences in the level of political support for sustainability are reflected in the institutionalisation of regime intermediaries. While the municipal authorities of Hannover and Nuremberg established a regime intermediary by means of an Agenda 21 Office, and introduced an internal coordination mechanism through the reporting scheme on sustainability, the administrations of Göttingen and Kassel are organised differently. Specifically, the City of Göttingen set up a Climate and Energy Unit rather than a Local Agenda 21 Office. While the Local Agenda 21 plays only a marginal role in Kassel, the former Office of the Future (2008–2018) acted as an intermediary between TT Kassel and the municipality. This, however, was not an organisational unit for sustainable development but to encourage citizen participation.

A comparison of local institutions reveals further differences between the participatory cultures and instruments that have evolved in the cities. These are more firmly established in Hannover and Nuremberg than in Göttingen or Kassel. Of the four cities, Nuremberg stands out for its tradition of citizen participation and consensus-seeking culture. The manifold dialogue forums and participatory processes of the municipality provide important entry points for Bluepingu.

At the micro-level, the individual roles of transition intermediaries in the TTIs, as well as, the municipalities are important. While the transition intermediaries of TT Hannover and Bluepingu are highly proficient in instrumentalising external funding structures, TT Göttingen and TT Kassel struggle with the acquisition of funding. This proficiency and knowledge of funding structures explain the effectiveness of the TTIs. Similarly, regime intermediaries seeking to initiate transformative change from above can be found in all four municipalities. Yet due to the beneficial political (meso-level) and structural setting (macro-level), they create a higher impact in Hannover and Nuremberg than in Göttingen and Kassel.

5.2. Reflections on intermediaries and urban sustainability transitions

The findings of our comparative case study provide insights on the roles of transition intermediaries, the politics of urban sustainability transitions and the contextualisation of the roles and activities of intermediaries in local governance settings, and the significance of regime intermediaries and the reconfiguration of regimes from within. We have shown the relevance and contribution of transition intermediaries by outlining the roles and functions they adopt in building partnerships for urban transitions. These findings confirm that transition intermediaries perform a heterogeneity of roles (Kanda et al., Citation2020; Kivimaa, Boon, et al., Citation2019). This study of transition intermediaries, following an agency perspective, can inform and complement the study of transition mechanisms, following a process perspective. In the literature on sustainability transitions, these mechanisms have been originally defined as deepening, broadening and scaling up (van den Bosch & Rotmans, Citation2008; van den Bosch-Ohlenschlager, Citation2010). These conceptions of transition mechanisms have been refined and expanded by several scholars. Building on the study of sustainability transitions, urban governance and transformative agency, up-scaling, replicating, partnering, instrumentalising and embedding have been defined as mechanisms for promoting sustainability transitions in urban contexts (Ehnert, Frantzeskaki, et al., Citation2018; Frantzeskaki et al., Citation2017; Gorissen et al., Citation2018). Informed by organisational change science, the transitions mechanisms of energising, learning-by-doing, the logic of attraction, the bandwagon effect, coupling and robustness have been developed (Termeer & Dewulf, Citation2019; Termeer & Metze, Citation2019).

As our findings illustrate, transition intermediaries can promote sustainability transitions by facilitating these mechanisms in multiple ways (see ). By envisioning alternative development pathways, transition intermediaries can encourage reflection on other belief systems. By articulating local needs and expectations, they can give local actors a voice and empower them. By encouraging experimentation and learning-by-doing, intermediaries can make impacts visible and accessible to actors and raise their commitment. With these functions, intermediaries support the mechanism of energising. By promoting learning-by-doing, intermediaries encourage reflection on experiences gained and feedback received through experimenting.

Table 1. Transition mechanisms and transition intermediaries.

The processes of replicating and up-scaling, and the bandwagon effect are supported by the roles of intermediaries in aggregating knowledge, framing and coordinating local-level activities, and building networks. By acting as knowledgeable information brokers, intermediaries help to aggregate and share the lessons learned from local projects and initiatives across actors, communities and governance levels. Knowledge on common challenges encountered and the effects of local interventions on transition dynamics helps in guiding subsequent action in other communities. Moreover, they support replicating and up-scaling by providing education and advice to other actors and initiatives.

By facilitating the building of networks and partnerships and aligning interests, intermediaries foster partnering. By setting up shared institutional infrastructures, they support cooperation and the complementing of resources to create synergies between local projects. By mobilising support and using opportunities provided by the multi-level governance context, intermediaries facilitate instrumentalising. In a similar vein, they support the coupling of policy issues and political priorities, embedding and robustness by advocating for change and policy renewal. By translating the vision of a sustainable city to local contexts and combining it with local societal needs and discourses, intermediaries create linkages with other local policy priorities to mobilise support and embed new socio-technical configurations through institutional change.

We have addressed the research gap on the politics surrounding transition intermediaries (Kivimaa et al., Citation2020; Kivimaa, Boon, et al., Citation2019) by placing them in their urban governance contexts and illustrating their role in cities as the places where political struggles inherent in sustainability transitions will surface (Castán Broto, Citation2017). While the empirical findings show the potential of TTIs as creative hubs and correctives to local governments, they also caution against exaggerating the transformative potential of niche intermediaries (Marvin et al., Citation2011). As TTIs are embedded in local governance contexts, they are reliant on political priorities, prevalent ideological frames and funding from public institutions or businesses; in other words, they are sustained by the incumbents of the regime (Fischer & Guy, Citation2009; Hodson & Marvin, Citation2012; Horne & Dalton, Citation2014; Kivimaa, Citation2014; Moore et al., Citation2012). As our findings indicate, TTIs seek to create a new regime of sustainability but are hesitant about breaking down the old regime of unsustainability. It is far easier to find political agreement on establishing sustainable niches (in addition to the existing regime) than to face political conflict when trying to dismantle the old regime. This underlines the fragility and uncertainty of the action of intermediaries (Marvin et al., Citation2011).

We have shown the importance of niche and regime intermediaries in building partnerships between civil society and municipalities. Our empirical findings corroborate the claim that only an ecology of diverse transition intermediaries can overcome the fundamental challenge posed by sustainability transitions (Kivimaa, Boon, et al., Citation2019). While the action of TTIs is necessary, it is not sufficient. Evidently, two transformative pathways must be utilised for urban transitions to succeed: change from below by civil society and change from above by local governments. Innovative approaches to urban governance make use of both niche and regime intermediaries. Niche intermediaries have more freedom, independence and creativity to think out of the box. In contrast, regime intermediaries have the technical knowledge and familiarity with political and administrative processes to formulate and implement political concepts and projects. Owing to this expertise, they know how to translate innovative ideas into established institutions. These findings underline the importance of reconfiguring regimes from within, which is also described as ‘reconfigurational transformation’ (Sovacool et al., Citation2020, p. 15). While transitions towards sustainability challenge incumbent regimes, these incumbents also seek ‘to survive the evolutionary process of transition by having a stake in change and in so doing are already significantly shaping change’ (Sovacool et al., Citation2020, p. 15). This elucidates the engagement of regime intermediaries and their central role in defining new transformative governance structures (Kivimaa, Boon, et al., Citation2019).

6. Conclusion

In this comparative study of partnerships for urban sustainability transitions, we have sought to link the debate on transition intermediaries to the debate on the governance and politics of sustainability transitions. By comparing transition intermediaries in four cities, we have provided insights on the importance of intermediaries in transitions by building bridges between niches and regimes, and translating and aligning the interests of innovators and incumbents. We have elaborated how these intermediaries facilitate transition mechanisms. We have elucidated the politics of urban sustainability transitions by illustrating the contextualisation of transition intermediaries in different urban governance settings. We have further shown the significance of regime intermediaries and of reconfiguring regimes from within.

These findings have several implications for practice. Given the essential role of intermediaries, they should be institutionalised by providing long-term financial support and organisational stability (Hodson & Marvin, Citation2010; Kanda et al., Citation2020; Kivimaa, Boon, et al., Citation2019). However, this relates not only to financial resources, but it is equally important to give regime intermediaries an official mandate to advance transitions. They can be established in local public administrations in a twofold manner: by introducing intermediary offices or agencies with a mandate to coordinate between administrative departments and agencies (horizontal coordination), and by introducing designated appointees for sustainability within administrative departments and agencies (e.g. appointee for sustainable energy, mobility, green infrastructure and urban agriculture). These professional mediators and facilitators could adapt the creative techniques applied by TTIs like frame talks, earth forums or role plays to translate between the perspectives of public, private and civil society actors and build trust. Institutional change by establishing a reporting scheme for urban sustainable development creates transparency on the activities of the municipality vis-à-vis civil society and fosters communication and cooperation within the public administration. While TTIs experiment with novel projects and practices, they have to engage in political advocacy to integrate these socio-ecological innovations in urban policies. Regime intermediaries should therefore provide professional guidance on how to navigate the local policy environment, explaining the functioning of city councils and public administrations, and facilitating the access to political decision-making. Politicians should support a mix of intermediaries adopting multiple roles (Kanda et al., Citation2020), because niche and regime intermediaries complement each other and change from below should be combined with change from above.

The limits of the adopted comparative research design point to avenues for future research. We have compared, on the one hand, two cities enjoying strong political support for sustainability and TTIs driven by highly-proficient niche intermediaries with, on the other hand, two cities displaying weaker political support for sustainability and TTIs whose change agents are less proficient. In an alternative research design, highly professionalised TTIs could be studied in a local setting with little political support for sustainability in order to explore the extent to which change can be promoted from below. Conversely, municipalities with strong political backing for sustainability but lacking niche intermediaries from civil society could be analysed to explore the potentials and challenges of change from above.

All four cities we studied are in the pre-development phase of a transition. However, the roles and functions of intermediaries may alter during the transition process (Kivimaa, Hyysalo, et al., Citation2019). In future research, cities in different phases of a transition – the pre-development, take-off, acceleration and stabilisation phase – could be examined to create insights on the changes in intermediary roles. Moreover, adopting the perspective of polycentric governance, the roles of transition intermediaries – both niche and regime intermediaries – in multi-level governance systems could be studied in more depth to illuminate how they connect different governance levels and geographical places (Kivimaa, Boon, et al., Citation2019; Kivimaa & Martiskainen, Citation2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of our respondents for giving up their valuable time to engage in interviews and a workshop to make this research possible. We thank Andreas Blum and two anonymous reviewers for comments and constructive critique on earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on the contributors

Franziska Ehnert studies urban transitions towards sustainability. She analyses how they can be governed, exploring governance instruments to initiate, accelerate and consolidate transitions in urban settings. By examining participatory governance for urban transitions, she seeks to study new forms of governance to empower citizens to co-create their cities and local communities. She earned her PhD in political science from the University of Potsdam, Germany.

Markus Egermann is geographer and planner by training. He is head of the research area Transformative Capacities at the Leibniz Institute of Ecological Urban and Regional Development (Dresden, Germany). His research addresses transformative change, transition theory and transition governance. He explores new ways of producing knowledge in transdisciplinary and transformative research settings like real world laboratories and transition experiments.

Anna Betsch studied Human Geography (BSc) and Resource Analysis & Management (MSc) at the University of Göttingen, completing her degree with a Master thesis on alternative food networks in Germany. During her time as a research assistant at University Göttingen, she worked on a DFG funded project on sustainable food consumption practices of middle class consumers in Bengalore, India. As a researcher at Leibniz Institute of Ecological Urban and Regional Development, Anna studied social innovations as well as transition town initiatives. She specialises in grassroots innovation for sustainable cities and currently works for a Dresden-based NGO that is active within the wider movement of maker-spaces, grassroots innovation and sustainable urban development.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

References

- Aldrich, H., & Herker, D. (1977). Boundary spanning roles and organization structure. Academy of Management Review, 2(2), 217–230. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1977.4409044