ABSTRACT

Organized denial has played an outsize role in frustrating U.S. climate progress. At the same time, a constellation of national security experts, think tanks and defense personnel have promoted a climate security frame for over a decade to advance climate action. This climate security coalition constructs credibility, serving as an implicit counterpoint to organized denial. A case study of two regions with large defense complexes and the climate security policy community reveals that credibility is constructed through two mechanisms: (1) individual climate security champions employ framing and communication tactics to persuade other decision-makers and (2) a coalition of these champions and other policy actors coordinate across levels of governance while bridging military and civilian realms. The climate security coalition accomplishes a form of multilevel governance, advancing adaptation through planning, policy, and consolidating resources. In this case, organized credibility helps to overcome ineffective framing and governmental fragmentation, two of the most persistent barriers to urban climate action. In addition to these concrete results, recognizing this non-environmental approach as an aspect of a credibility machine confers it power as an organizing strategy. This has potential to translate to other domains, further extending the constituency for climate action beyond the usual suspects.

Introduction

Powerful ‘denial machines’ that orchestrate the purported debate over climate change perpetuate inertia in the U.S. response to climate change (Dunlap & McCright, Citation2003; McCright & Dunlap, Citation2000; Mccright & Dunlap, Citation2011; Oreskes & Conway, Citation2010). This agenda gained greater influence with a denier’s attainment of the presidency in 2016 and subsequent reshaping of federal agencies (Hejny, Citation2018). In the face of this, one of the few bulwarks within the federal government was the Department of Defense (DoD), where planning and operations continued to respond to the risks of a changing climate (Eilperin et al., Citation2019; The Economist, Citation2018). The DoD is one organization within a larger constellation of experts, think tanks, politicians and media mobilizing a climate security agenda for adaptation in the U.S. While the climate security discourse has become prominent at the federal level, it also operates at the local level, particularly in defense communities.

This study interrogates whether the climate security coalition simply promotes an agenda, or whether it results in concrete progress on adaptation, overcoming common barriers. A relational case study of urban/military collaborations for adaptation in Hampton Roads, Virginia; San Diego, California; and the climate security policy community based in DC reveals that it has had impacts including forming multi-level collaborations, influencing senior decision-makers, developing policy and plans and securing resources. Two salient adaptation barriers are conceptualized as vectors for action, overcoming denial and fragmentation. This case study reveals some successful efforts in both areas. At the individual level, champions strategically mobilize the climate security frame and persuasive tactics to convince other decision-makers to identify with a climate security discourse. At the organizational level, these champions and other policy actors build a climate security coalition by developing new networks and institutions, leveraging inside knowledge, and formalizing programs.

This climate security coalition is an aspect of a ‘credibility machine,’ an implicit counterpoint to the power of organized denial. Recognizing organized credibility and understanding how it operates can help to harness support for climate action beyond the usual suspects, typically reliant on an environmental narrative. Additionally, the climate security coalition accomplishes a form of multilevel governance, building connections across sectors and levels of government and creating capacity to continually advocate and implement climate policy. Finally, there are potential pitfalls to increasing the influence of organized credibility. Like much adaptation work, the climate security project risks foregrounding adaptation over mitigation, high value assets over vulnerable populations, and sensational impacts over quotidian ones. However, climate security has proven to be a malleable frame, and so may be harnessed for not only concrete progress in the name of realpolitik, but progressive climate action.

Literature review: overcoming denial and fragmentation

In this study, framing and fragmentation, two of the key barriers to effective urban climate governance (Bierbaum et al., Citation2014; Hallegatte & Corfee-Morlot, Citation2011; Measham et al., Citation2011; Moser & Ekstrom, Citation2010; Oberlack, Citation2017; Shi, Citation2019) are the two most salient barriers to adaptation that surfaced through inductive analysis. These problems anchor the transdisciplinary literature review which draws from research in multilevel governance, environmental politics, social psychology and policy studies. Within extensive searches of literature on denial and fragmentation, the research reviewed here was selected based on its explanatory power with regard to the ascendance of policy networks within decision-making contexts. Some of the literature addresses other scientific ‘controversies’ in addition to climate, however, climate served as a filter because that literature alone is so extensive.

Overcoming denial

Climate skeptics have deliberately weaponized framing, or tailoring a message to resonate with existing narratives and ideologies. A climate denial machine, encompassing the coordinated effort of corporations, foundations, think tanks, media, and politicians has played a crucial role in blocking climate legislation in the U.S. by manufacturing and disseminating uncertainty and polarizing the issue (Dunlap & McCright, Citation2010, Citation2011; Oreskes & Conway, Citation2010). The climate change counter-movement has become persistent and deep-rooted (Almiron & Xifra, Citation2019; R. J. Brulle, Citation2014). Denial is not just about the social psychology of accepting (mis)information on an individual level, but about how coalitions link framing and organization to mobilize information for political ends. These coalitions enhance the legitimacy of a position by their existence (R. J. Brulle, Citation2019). Organized denial reflects partisan politics; conservatives had historically been opposed to environmental protection which they considered a threat to individual rights and the free market (Dunlap & McCright, Citation2003; McCright & Dunlap, Citation2000). Political orientation can be the most important predictor of climate change perceptions (Marquart-Pyatt et al., Citation2014; Mccright & Dunlap, Citation2011) and the gap between liberals and conservatives on this issue is continually widening (Hornsey & Fielding, Citation2020).

Research on overcoming denial is largely based on social psychology at the individual level and tends to focus on frames and communication tactics. Both issue frames and value frames have been examined for their impact on perceptions of climate messages and policy. It might be expected that conservative frames could combat skepticism, but a study of the effectiveness of alternative issue frames including national security, economic opportunity, faith-based stewardship and public health as a direct counterpoint to a denial frame revealed that issue framings had negligible impact (McCright et al., Citation2016). However, military delivery of a climate message may increase belief among both liberals and conservatives, suggesting an approach to increase bipartisan support (Bolsen et al., Citation2019). In the U.S. political context, climate security discourse may be necessary to put climate change on the federal agenda (Diez et al., Citation2016). Further, the military can play an important role in validating climate science, and by extension, action (Light, Citation2015).

Experiments in social psychology that emphasize the values underpinning conservative frames such as hierarchism and individualism, rather than partisan lines, reveal that framing can result in attitude shifts. Moral values that resonate with conservatives, such as loyalty to the U.S. and respect for authority, can be more effective than typical liberal environmental messages (Wolsko, Citation2017). Similarly, values such as a hierarchical worldview can be a stronger predictor of support for climate policy than political ideology or affiliation (Leiserowitz, Citation2006). Nimble persuasion can address the roots of skeptics’ rejection of science such as ideologies, social identities and vested interests, rather than their surface attitudes (Hornsey & Fielding, Citation2020). Culturally appropriate messages can help to debunk misinformation, while a focus on policies rather than climate attitudes can be more persuasive to an audience that rejects the human causes of climate change (Lewandowsky, Citation2021).

Beyond framing, researchers have examined persuasion tactics for overcoming denial. From this perspective, the message source, or messenger, is a tactic to be proactively deployed. Early research on climate gridlock showed that if ‘trusted sources’ deploy frames such as economic competitiveness and morality, this could help coalesce more diverse audiences around climate action (Nisbet, Citation2009). Because audiences differ by ‘what messengers are credible to them,’ messengers must be consistent with the framing and fit the context (Moser & Dilling, Citation2011, p. 166). Analysis of ‘in-group messengers,’ demonstrates that the source of the message can have a greater impact than the substance. Group membership can even be a ‘gateway consideration’ (Delorme et al., Citation2018, p. 17; Esposo et al., Citation2013; Hornsey & Fielding, Citation2020). The concept of latent ‘broker’ categories such as national security and religion, suggests how ‘climate brokers’ might effectively bridge partisan divides (Hoffman, Citation2011, Citation2015). A shared sense of identity between messenger and audience can bridge the science-policy gap more effectively than quality information, and leaders of successful research/policy partnerships may be able to actively mobilize this to unite unlikely allies (Mols et al., Citation2018).

Within communication research, the concept of credibility has received sustained attention. Credibility, or the believability of information, arises from two main factors, trustworthiness and expertise. In turn, cognitive authority is established based on credibility and influence. A cognitive authority is ‘an authority’ or a person or source whose opinions are taken more seriously than others. This is distinct from administrative authority or being ‘in authority.’ However, ambiguity between the two types of authority is common (Rieh, Citation2010). In some cases, this slippage amounts to a common logical fallacy, the ‘appeal to authority’ in which the fact of being in a position of authority stands in as a legitimation of expertise (Walton, Citation1997). However, it also serves as a reliable mental shortcut, a ‘trust heuristic,’ which facilitates decision-making for those who lack the relevant expert knowledge (Cummings, Citation2014).

One of the most widely supported ways to counter misinformation is through inoculation, or explaining away misinformation before conveying the correct information. Inoculation has largely been analysed in experimental settings, however, in practice, it can be accomplished with refutational teaching which raises and then immediately addresses misconceptions (Cook, Citation2019). In a similar vein, a ‘conversion narrative’ can have a greater impact than direct advocacy; giving insight into why decisions were made tends to create a more lasting attitude change about contested scientific issues (Lyons et al., Citation2019). However, the vast majority of these results were from experimental studies. Recognizing that facts, alternative and otherwise, form part of political narratives, methods of bridging partisan faultlines through authentic engagement need to be examined in actual political contexts where the divides remain vast, and must urgently be addressed (Fischer, Citation2019, Citation2020). In a ‘post-fact’ landscape, coordinated communication and political and institutional strategies connecting across multiple levels of governance may harness the capacity to overcome the organizational power of misinformation (Farrell et al., Citation2019).

Overcoming fragmentation

Cities are widely seen as important agents of change in the global climate arena (Romero-Lankao et al., Citation2018; Rosenzweig & Solecki, Citation2018; Watts, Citation2017), but they lack the capacity to effectively shift climate policy independently (Bulkeley et al., Citation2014; Bulkeley & Betsill, Citation2005; Frug & Barron, Citation2013). Cities face challenges to coordinating horizontally, including across jurisdictions within a region, and across sectors spanning the public and private sphere (Hughes, Citation2017; Shi, Citation2019). They also face challenges to vertical integration between cities and subnational and national entities (Gordon, Citation2018; Hughes, Citation2017; Hughes et al., Citation2018). Inadequate coordination between and across levels of governance is one of the major constraints of urban climate action (Bierbaum et al., Citation2014; Hallegatte & Corfee-Morlot, Citation2011; Shi, Citation2019).

To overcome these forms of fragmentation, urban actors have increasingly been producing and enrolling ‘new spheres of authority’ at ‘the boundaries of formal politics, in relations between state and nonstate actors, and between national and international politics’ (Betsill & Bulkeley, Citation2006, p. 150; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2003). Cities have been able to ‘scale up’ climate policies through horizontal learning between leading cities, typically through transnational networks, and vertical upscaling in which a local initiative influences either formal institutions or values at higher governance levels (Fuhr et al., Citation2018; van Doren et al., Citation2018). In the EU context, synergies between horizontal and vertical expansion result in ‘embedded upscaling’ which can further expand the influence of climate policy: ‘the expansion of local climate policies may even have a catalytic effect on higher levels of government’(Fuhr et al., Citation2018, p. 4). In the American context, this has taken a particular form, ‘boomerang federalism’ in which local actors mobilize in the absence of federal policy to secure approval for federal funding, expanding programs which then benefit other localities (Fisher, Citation2013). These moves are accomplished by coalitions which ‘need to be conceived as spanning different levels of governance’ (Bulkeley, Citation2000, p. 745).

Individual political champions tend to be a critical component of mobilizing these local efforts (Kalafatis & Lemos, Citation2017; Salon et al., Citation2014), but they operate within larger organizational entities. City networks are one of the more common forms of organization that achieve elements of horizontal coordination and vertical integration (Bansard et al., Citation2017; Bouteligier, Citation2013; Fünfgeld, Citation2015; Johnson et al., Citation2015; Lee, Citation2013). Studies of transnational and multiactor governance have highlighted the role of subnational governments, NGOs, and corporations operating in public, private, and hybrid network arrangements (Andonova et al., Citation2009; Newell et al., Citation2012), but more attention is necessary to loosely affiliated policy networks that operate within and across jurisdictions outside of formal city networks (Fuhr et al., Citation2018; Hughes, Citation2017; Schroeder et al., Citation2013).

The discourse coalition concept provides one way to understand the formation and effects of these loose networks that coalesce around a motivating policy problem and solutions. Unlike the advocacy coalition framework in which beliefs are described as relatively fixed and disseminated outward, the discourse coalition is predicated on an understanding of knowledge, beliefs and values as socially constructed and contested (Billig, Citation1997; M. A. Hajer, Citation1993). Discursive positions only exist in struggles with their counterpoints, and beliefs and values are continually constructed through interactions between actors and the practices they produce and reproduce (Bulkeley, Citation2000; Fischer, Citation2003; M. Hajer & Versteeg, Citation2005). Following Hajer whose framework has been operationalized in subsequent case studies, a discourse coalition comprises storylines, the actors who voice them, and the practices which are consistent with them; these coalitions may not only structure, but institutionalize discourse as it becomes hegemonic (Bulkeley, Citation2000).

Unlike formal networks in which actors recognize themselves to be part of an organization, a discourse coalition includes those who identify with and use a discourse though they may have no explicit affiliation (Rydin, Citation2021). Encompassing practices as much as narratives, ‘persuasive discourses can even in the face [of] entrenched social and material forces open new paths to action (Fischer, Citation2003, p. 91; M. Hajer & Versteeg, Citation2005).’ So discourse necessarily has effects, but interrogating the scope of urban climate action, questions arise about the extent to which coalitions deliver on an agenda through the institutionalization of discourse. Even when a coalition shapes discourse, as in the case of a ‘no regrets,’ storyline, it may not achieve institutionalization due to the relative power of a competing resource-based coalition (Bulkeley, Citation2000). When a discourse coalition does provide structure and legitimacy for an emerging policy concept, as in the case of soft, trans-boundary, planning spaces, it can be difficult to discern the consequences (Purkarthofer, Citation2018). Discourses of sustainability can be effectively wielded as an ‘inclusive umbrella’ to unite contentious actors and build a coalition, but result in the institutionalization of win-win solutions that shut down more critical openings toward transformative climate action (Acuto & Rayner, Citation2016; Tahvilzadeh et al., Citation2017). This type of closure suggests the risk of maladaptation, or simply shifting vulnerability in time or space (Juhola et al., Citation2016).

Investigating the climate security project in relation to common barriers to adaptation, the research is guided by the following questions: (1) Does the climate security coalition simply structure a discourse or does it institutionalize it, resulting in concrete planning and policy outcomes? (2) If so, what are the individual and organizational mechanisms involved in institutionalizing the discourse?

Methods: a relational case study

This research was undertaken through a relational case study (Burawoy, Citation1998; Flyvbjerg, Citation2006; Yin, Citation2013) of urban/military collaborations for adaptation planning in Hampton Roads, Virginia and San Diego, California in the context of the climate security policy community, based in DC. Examining how local and national agendas and practices influence policy at multiple levels and across local contexts is similar to a policy mobilities approach (Goh, Citation2020; McCann & Ward, Citation2012; Peck & Theodore, Citation2012).

Fieldwork in Washington, DC, Hampton Roads and San Diego in 2017 involved engaging with communities of practice to trace the evolution of influential norms, policies and practices. Data was collected through semi-structured interviews of local government, non-profit, academic, and military decision-makers (n = 97) and participant observation at conferences and meetings. The majority of the interviews were conducted in person, recorded, transcribed and coded. Interview responses and participant observation were triangulated with content analysis of policy documents and plans. A discourse analysis process, attending to discourses, subject positions and practices, also drawing from rhetorical analysis, informed the coding and synthesis of emerging findings (M. Hajer & Versteeg, Citation2005; Rydin, Citation2021; Sharp & Richardson, Citation2001).

Case selection

Several criteria informed the case selection of Hampton Roads and San Diego: size and number of defense installations, defense contribution to the regional economy, level of flood risk, existence of urban/military planning collaborations, and connection to national climate security policy discourse.

Hampton Roads

The Hampton Roads region at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay is home to the largest naval base in the world, Naval Station Norfolk, and fifteen additional defense installations. Defense spending plays a significant role in the regional economy, directly and indirectly accounting for approximately 40% of regional GDP (Clary & Grootendorst, Citation2013).

The mid-Atlantic region is a hot spot for sea level rise, and Norfolk already experiences ‘nuisance flooding’ which affects everyday life and military operations (Sweet & Marra, Citation2016). The main connection between the base and Norfolk, Hampton Boulevard, is regularly flooded, undermining operational continuity (Union of Concerned Scientists, Citation2016). Municipal and defense stakeholders have undertaken several joint planning processes including a Department of Defense Climate Change Preparedness and Resilience Regional Pilot from 2014 to 2016 (Office of the Under Secretary of Defense Acquisition Technology and Logistics, Citation2014; Steinhilber et al., Citation2016), and Joint Land Use Studies coordinated by the Hampton Roads Planning District Commission from 2017 to 2019 (HRPDC, Citation2016).

San Diego

Like Hampton Roads, San Diego County is home to a major agglomeration of defense installations. Naval Base San Diego is the largest on the West Coast. Defense spending in San Diego plays a significant role at 22% of regional GDP, second in the country (San Diego Economic Development Corporation, Citation2016; SDMAC, Citation2016; U.S. Department of Defense & Office of Economic Adjustment, Citation2015).

On average, the East and Gulf Coasts of the United States have higher rates of sea level rise than the West Coast. However, the southern California Coast has a high rate of sea level rise for the West Coast (Griggs et al., Citation2017). San Diego has experienced nuisance flooding in streets up to several miles inland during ‘King Tides’ as well as extensive road closures during major precipitation events. Scientists see this level of flooding, which is currently rare, as a harbinger of sea level rise to come (National Ocean Service et al., Citation2015).

In San Diego, urban/military collaboration has been more limited than in Hampton Roads. Regional institutions such as the San Diego Association of Governments and the San Diego Regional Climate Collaborative have facilitated some minor collaboration. The only substantive collaboration occurred with a 2018 Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) between the Unified Port of San Diego and the Navy to work cooperatively on sea level rise planning.

Washington, DC

DC is the center of gravity for U.S. climate security, home to organizations including the Center for Climate and Security, CNA (historically the Center for Naval Analyses), and the American Security Project. Interviews and participant observation with this community of practice illuminated the federal backdrop to regional case studies.

Limitations

The key limitation to external validity is the number of cases. Additional cases varying by flood vulnerability or degree of defense dependency would provide further insight into how climate security discourse is mobilized, potentially complicating the findings. Respondent sampling was limited through a focus on senior decision-makers, policy elites, and mid-level technocrats and access was somewhat dependent on personal relationships and networks. Respondents’ representations of themselves were likely shaped by the interviewer’s previous experience with built environment disciplines which may have led to assumptions of similar worldviews and a level of comfort in speaking. This was partially countered through extensive policy document and media analysis. However, no Freedom of Information Act requests were submitted because a respondent advised that these could be viewed as adversarial and therefore close doors. That material would provide additional insights, countering assumptions of mutual understanding in the interview material.

Results: the climate security coalition constructs credibility

The climate security coalition constructs credibility for climate action through two related mechanisms. (1) Individual climate security champions, who tend to be in senior decision-making roles, employ framing and communication tactics to persuade other decision-makers of the need for climate planning and action. (2) A climate security coalition comprised of these champions coordinates across scales and levels of governance while bridging military and civilian cultures. This coalition of defense professionals, think tanks, retired and active duty military personnel, media and funders coordinate on the premise that climate change is a national security threat, achieving planning and policy outcomes.

Climate security discourse: persuasive effects in practice

Case studies of urban/military adaptation planning in Hampton Roads, Virginia and San Diego, California both revealed how climate security champions enlisted a suite of tactics to persuade decision-makers, thereby expanding the climate constituency.

In some instances, high ranking military personnel had an influence on local momentum. In Hampton Roads, a retired rear admiral gave an address at a regional environmental forum in 2010, and this served as a turning point for local power-brokers. A former commanding officer of Naval Station Norfolk who also acts as a regional adaptation champion noted the dramatic impact:

... we had 450 people. A lot of them came just because he was a rear admiral and a lot of people assumed he'd be a climate change denier but he gave this incredible presentation, no holds barred, it is real, it is getting worse, it is caused by human beings and we damn well better do something about it. All of a sudden, locally, the business community, and a lot of people [who] will ignore environmental groups and tree huggers, ... couldn't ignore a navy rear admiral. That was a game changer.

Assuming the rear admiral would be a denier, the audience was at least partially right. As he would continue to do on his speaking circuit, he acknowledged that he had been a skeptic (Harper, Citation2010), but explained that the data had become too overwhelming. With this tactic, he employed a version of both refutational teaching and a conversion narrative, explaining how and why he had changed (Cook, Citation2019; Lyons et al., Citation2019). In his uniform, he embodied the institutional authority of the military, allowing that authority to reinforce his authority as a climate expert (Walton, Citation1997) and appealing to a hierarchical worldview (Jenkins-Smith et al., Citation2014). This was part of his explicit effort to align himself as a messenger with conservative-leaning audiences. He even avoided left-leaning audiences that might damage his credibility by association.

Similarly, the executive director of a local environmental non-profit and veteran of Capitol Hill sought to reach beyond the usual suspects. In 2014, he and other environmentalists organized a bipartisan regional summit on sea level rise. He contended that for military personnel, the bipartisan aspect was key to the legitimacy of the event. In turn, their presence lent the issue further credibility.

there were Democrats and Republicans there, so then it was not [a Democrat] running an agenda … the captains and colonels and flag officers that were there felt as though it was a legit forum … it was a bunch of flag officers saying, ‘Hey, we got a problem’ and they were in a room talking to other members of congress. There were 350 people in there who were from various sectors in the region so, that was one of those moments that sort of started to change things.

Once again, the military presence conveyed a form of authority that was persuasive to a broader spectrum of decision-makers (Bolsen et al., Citation2019; Walton, Citation1997). In these events, the effort to bridge partisan divides had a noticeable impact; in quotidian military/civilian interactions, a less explicit persuasion tactic unfolded. A community planning liaison officer at one of the bases in the region captured how the perception of DoD neutrality could be politically useful in community engagement.

It is important … for us to be able to look at, how do we be resilient from anything that may come our way, regardless of what the political climate is at the time. … in this position, I have to stay as neutral as possible, and I have to be able to accurately represent the federal government and the Department of Defense, and all the layers in between … We know there are things that need to be solved, and we are working with the community to do so. We're just doing it from the common sense ways we are allowed to.

Framing resilience as ‘common sense’ echoes the ‘common sense’ rejoinder to other hyper-partisan debates, such as gun control, in an attempt to render solutions uncontroversial. Focusing on policies rather than attitudes is a communication tactic documented to overcome denial (Lewandowsky, Citation2021). In Hampton Roads, managing quotidian planning conversations through the defense lens worked together with high profile efforts to defuse partisan tensions, creating a foundation for substantive planning in a region with partisan faultlines.

In the California political climate, far more conducive to aggressive climate planning, the defense lens also played an instrumental role. Champions in San Diego saw value in using the Navy to reach dismissive decision-makers. A port commissioner made the utility of Navy support explicit as he pursued, and ultimately achieved, a formal Port/Navy agreement to coordinate sea level rise planning:

If we’re successful, the role will be huge because the Navy is considered apolitical, people don’t view the Navy as having biases that are politically driven, they’re not suspect [sic] that this is a hoax, all of the skepticism that you hear, the Navy enjoys this immunity from that type of attack, having the Navy on board as a messenger and a validator is huge.

In further discussion, the commissioner conveyed, ‘Fortunately, I can point to you guys [the Navy] and say,’ ‘If they're thinking about it, we definitely need to be thinking about it.’ This implies that the Navy is defying expectations by considering climate change; this turn is related to the efficacy of a conversion narrative in challenging an audience’s assumptions to provoke more systematic thinking (Lyons et al., Citation2019). At the same time, the Navy’s attention suggests it is a serious matter. As in Hampton Roads, this enlists the mental shortcut of an ‘appeal to authority.’ Though this may be a logical fallacy, it can also be a reliable decision-making shortcut, a ‘trust heuristic’ (Cummings, Citation2014). When the recipient trusts the Navy, by extension, they trust naval positions on climate.

In addition to influencing regional climate politics, at the federal level, the national security frame has been important to overcoming partisan stalemates and supporting policy development. The executive director of the CNA Military Advisory Board noted that:

the national security frame has allowed us to have conversations on climate change that rise above the polarizing politics of climate policy. … This frame also allows more conservative policy makers to engage on this issue through the lens of national security … If climate change is viewed solely as an environmental issue, then it is difficult, if not impossible in today’s political arena, to foster bipartisan discussion.

A retired Brigadier General, engineering professor, and prominent climate security proponent noted a similar effect. When he and other climate security advocates approached Republican congressional staffers, they were surprisingly receptive to a message that joint adaptation was a sensible way to achieve military readiness. Experimental research has returned mixed results (Leiserowitz, Citation2006; McCright et al., Citation2016; Wolsko, Citation2017), but these reports suggest that in the field, in dynamic contexts, the climate security frame, coupled with a conversion narrative, refutational teaching, appeals to authority or a focus on pragmatic outcomes can influence conservative decision-makers.

The climate security coalition: coordination across levels

These framing and persuasion tactics provide a window into the work of climate security coalition-building at the level of individual interactions and events. In addition to this, champions and other policy actors have built a whole organizational infrastructure, opening doors and convening conversations based on the climate security premise. Operating on a set of compatible narratives, the discourse coalition coordinates across levels of government and the military and civilian spheres. Building up the climate security message, this coalition has (1) created new institutions and networks, (2) leveraged inside knowledge of civilian and military decision-making, and (3) formalized programs and agreements to achieve concrete planning and policy outcomes. This mobilization of resources is a potent example of how those with access to power build a coalition to enact a climate agenda even against substantial resistance.

Sherri Goodman, former Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Environmental Security laid the groundwork for the climate security coalition with simultaneous framing and organizational work. In the mid-2000s, several philanthropic foundations approached her to reframe climate change to overcome partisan rancor and a federal focus on counterterrorism. In response, she convened a Military Advisory Board of retired officers to guide a project analyzing the connections between climate risks and national security. Initially skeptical, they joined based on their longstanding relationship with Goodman and CNA’s reputation, and ultimately signed on to the report that declared climate change is a ‘threat multiplier,’ exacerbating existing instability (CNA Military Advisory Board, Citation2007). This concept gained traction in defense policy, the general defense lexicon and the media, making climate change more central to responsible risk assessment (Diez et al., Citation2016; Hoffman, Citation2015). Climate security proponents, journalists and filmmakers then turned this credibility within the defense establishment outward, leveraging the narrative of military climate action to influence external policy-makers and the public.

More recently, security experts formed the Center for Climate and Security (CCS) as a dedicated think tank. Similarly to CNA, they assembled an advisory board of retired officers and defense professionals which includes ties to all of the military services, philanthropies such as the David Rockefeller Fund and other research centers such as the Hoover Institution. Board members regularly testify before congress and meet with congress people behind the scenes, gaining these audiences based on the premise that climate change is a national security threat. As the coalition has grown, climate security discourse has gained legitimacy among power-brokers, enhancing additional access.

In addition, CCS has pursued a concerted outreach program to urban areas with a large military presence, holding public events on both coasts featuring a mix of national experts and local officials to discuss the common ground between installations and communities (CCS Staff, Citation2019). Even in places, such as the Carolinas, where local officials have been slow to discuss climate change, CCS has convened these conversations that lay the groundwork for planning. At the local level, in the Hampton Roads and San Diego regions, senior decision-makers regularly moved from military to civilian roles; at times they were able to leverage their inside knowledge to access data and decision-making frameworks that furthered civilian adaptation planning (Teicher, Citation2019).

In a more formal effort, a local delegation from Hampton Roads approached National Security Council connections to be included in a federal adaptation pilot project. Based on Navy involvement in incipient regional planning efforts, they campaigned for a slot in the ‘whole of government’ pilot; this increased the profile of the project with an apparent imprimatur from the White House. This also laid the groundwork for Joint Land Use Studies which for the first time officially recognized sea level rise as a form of encroachment on military bases. Operating on the rationale that flooding is a threat to the military mission, the American Flood Coalition has focused on specific policy to direct mission funds to off base adaptation. As a result, the Defense Access Roads (DAR) program has been amended to allow defense appropriations for flood damaged public roads (AFC staff, Citation2019). Similarly highlighting the defense risk, the Defense Community Infrastructure Program, a project managed by the Office of Local Defense Community Cooperation, now allows funding for a wide range of off-base infrastructure including resilience-focused projects (Association of Defense Communities, Citation2019).

Creating dedicated institutions, leveraging inside knowledge, and formalizing programs, the climate security coalition has not only constructed credibility around a climate agenda through persuading key decision-makers and audiences, but helped build policy and programs, institutionalizing adaptation under the banner of climate security. This unexpected and ongoing commitment to addressing climate change allowed for policy progress even against political headwinds, demonstrating the utility of unlikely allies in the climate fight. Complicating previous findings, as this coalition institutionalized a discourse, it delivered on an agenda, opening paths to reconstructive action (Bulkeley, Citation2000; Fischer, Citation2003; Purkarthofer, Citation2018; Tahvilzadeh et al., Citation2017).

Discussion: the climate security coalitions as a credibility machine

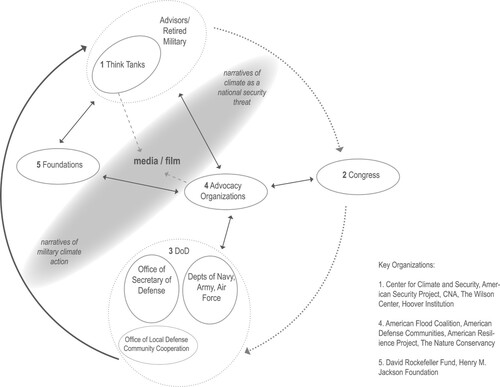

The climate security coalition, deliberately built and continually grown by champions, is an instance of a credibility machine, a counterpoint to the widely recognized denial machine. Organized credibility entails the same mechanisms at work in organized denial (Dunlap & McCright, Citation2011; Oreskes & Conway, Citation2010), involving relays between foundations, think tanks, defense personnel and media ().

Figure 1. The climate security coalition operates as a credibility machine, involving mechanisms similar to those in organized denial. Defense personnel, think tanks, foundations and media promote the agenda and put it to work.

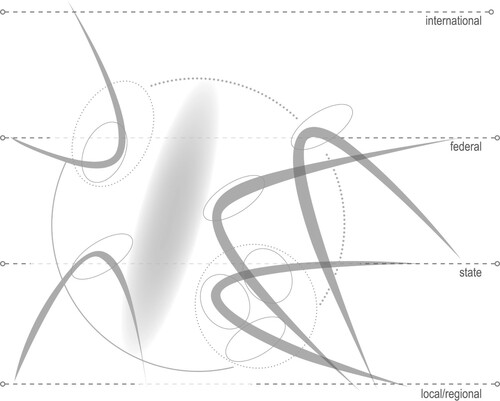

The climate security project has facilitated regional collaboration and directed federal resources toward local adaptation, demonstrating the efficacy of ‘boomerang federalism (Fisher, Citation2013).’ The upscaling that occurs in this case is more than a single relay. The climate security discourse coalesces through the work of individual champions who bridge military and civilian worlds and connect local and national levels of governance. As they speak to local problems and needs, they also interface with a national level policy community that adopts, translates and circulates the climate security message. As policy mobility literature predicts, these policy champions and communities converge on key messages, projects and approaches to address related problems (McCann & Ward, Citation2012; Peck & Theodore, Citation2012). With access to national networks, they effectively ameliorate governmental fragmentation through available channels. Within the relational network, the climate security discourse and organizing ricochet across levels and between localities in a form of ‘embedded upscaling’ (Fuhr et al., Citation2018). In other words, the operations of the climate security coalition illuminate how organized credibility acts as a form of multilevel governance (Betsill & Bulkeley, Citation2006; Bulkeley & Schroeder, Citation2012; Newell et al., Citation2012) ().

Figure 2. The climate security coalition mobilizes relationships, ideas and policies across levels of government. Multiple, overlapping instances of “boomerang federalism” achieve a form of “embedded upscaling” which results in multilevel coordination (Fisher, Citation2013; Fuhr et al., Citation2018).

This form of organized credibility proved to be of special value during a time of bald denial at the federal level. Climate security has been acknowledged as an effective frame to keep climate on the agenda (Diez et al., Citation2016). However, even with an administration committed to climate action, it retains value. The denial machine shows no sign of abating, simply shifting strategy (Brulle & Timmons, Citation2021). Discourse coalitions can employ different types of resources in bolstering a storyline. Success or failure in multiactor governance may draw from power rooted in authority, legitimacy and credibility (Newell et al., Citation2012, p. 379). ‘In this discursive struggle the credibility and acceptability of, and trust invested in, the storyline and the actors become significant’ (Bulkeley, Citation2000, p. 735). In this case, the persistent thread of credibility as a strategy illuminates how it can have power as an organizing framework (Farrell et al., Citation2019). In formal and informal policy discussions, forms of argumentation and persuasion which enroll credibility may contribute to the ascendance of a particular discourse (Hoffman, Citation2015; Moser, Citation2016; Moser & Dilling, Citation2011; Nisbet, Citation2009). As champions deploy climate security discourse and the climate security coalition coordinates across levels, their mechanisms demonstrate how authority and legitimacy for climate action can be reconstructed in an atmosphere of doubt and competing priorities.

The credibility machine is certainly not a panacea. The climate security project demonstrates some of its pitfalls. Climate security advocates represent the military as an ‘apolitical’ institution, but unquestionably enroll the military as a political tool to reach conservative audiences. They decouple climate change from an explicitly environmental message and by extension, they often overlook the anthropogenic nature of climate change, prioritizing pragmatic adaptation over mitigation. While this may be an effective tactic to spur action, it also risks maladaptation by shifting vulnerability (Juhola et al., Citation2016; Lewandowsky, Citation2021). Plans and programs carried out on a defense premise embody other risks common to many adaptation projects including prioritizing high value assets over vulnerable populations, prioritizing sensational risks over more pervasive ones, and relying on technocratic solutions (Adger et al., Citation2009; Barnett & O’Neill, Citation2010; Barnett & Palutikof, Citation2014). It remains important to continually recognize these, be aware of the trade-offs they entail, and pursue adaptation that is more equitable for communities and ecosystems (Steele et al., Citation2015). Climate security has brought attention to a climate agenda, but could still result in regressive or progressive climate action; the contestation involved here needs to be interrogated further (Gordon, Citation2018). Some climate security advocates address the ‘human security’ dimension of lives and livelihoods as well (Teicher, Citation2019). Some plans in progress direct resources toward low-income communities while federal defense community programs are poised to make resources available to small inland communities far from the adaptation limelight. The climate security frame is malleable and may be used for either inclusive or exclusive ends.

While the climate security project offers a unique angle, the process of establishing credibility is not unique to defense. Climate coalitions organized around public health, economic competitiveness, and faith-based stewardship suggest other versions of a credibility machine. Some of the climate security proponents who are committed to the defense angle maintain this broader perspective, considering it one useful message along with those related to health, business, and religion (Interviews, 2017). Each of these sectors, which offers a powerful, pragmatic, and not explicitly environmental narrative concerning the necessity for climate action, has already been recognized for its potential as a framing device and to some extent pressed into service through influential organizations (Goldberg et al., Citation2019; Hoffman, Citation2015; Nelson & Luetz, Citation2019; Nisbet, Citation2009). Analyzing each of these efforts through the framework of the credibility machine would foreground the extent to which the work is organized, how it achieves the institutionalization of discourse, the persuasive and concrete effects of that discourse, and how lessons might translate between sectors. This could advance the coordinated strategies that are necessary, but not yet developed, to overcome the ‘organizational power of misinformation’ (Farrell et al., Citation2019).

Conclusion

Extensive scholarly attention has gone into understanding the impact of organized denial on climate inaction. Similarly, sustained attention has gone to the social and environmental movements to which denial is the countermovement. Conceptualizing organized credibility as a third form of intervention suggests a way to confer power on non-environmental agendas as anchors for climate organizing. Studying the use of the climate security frame beyond an experimental setting in real world decision-making contexts positions it in a new light as a productive strategy. The case study here reveals an indication of that potential. In dynamic real-world decision-making contexts, constructing credibility can help to institutionalize a discourse coalition with direct results in planning, policy and resource consolidation. This concept requires further analysis to more deeply understand how coalitions that construct and mobilize credibility achieve results, and the potential for this to persist over time. In addition to security, organizing in the domains of health, business and faith, could be an avenue to harnessing the broadest political access, power, and resources to mitigate and adapt to runaway climate change.

Ethics approval

The research protocol was determined exempt by the MIT Committee On the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects, COUHES Protocol #1705961697. Informed consent was obtained in person at the time of each interview and by correspondence before inclusion in the original manuscript.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the reviewers for their comments which helped to substantially improve the manuscript. I would also like to thank Brent D. Ryan, Jennifer S. Light and Neil Brenner for their valuable feedback throughout the research process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hannah M. Teicher

Dr. Hannah M. Teicher is the Researcher in Residence for the built environment at the Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions where she catalyzes partnerships between academia, government, industry and NGOs for mitigation and adaptation. She is currently implementing an initiative to accelerate policy for embodied emissions at the city scale in buildings and beyond. In her PhD research in urban and regional planning at MIT she focused on cross-sectoral collaborations for adaptation planning. Before beginning her research career, Dr. Teicher practiced architecture in Vancouver where she played a key role in developing sustainable residential and community projects.

References

- Acuto, M., & Rayner, S. (2016). City networks: Breaking gridlocks or forging (new) lock-ins? International Affairs, 92(5), 1147–1166. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12700

- Adger, W. N., Dessai, S., Goulden, M., Hulme, M., Lorenzoni, I., Nelson, D. R., Naess, L. O., Wolf, J., & Wreford, A. (2009). Are there social limits to adaptation to climate change? Climatic Change, 93(3–4), 335–354. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-008-9520-z

- AFC staff. (2019). American flood coalition: Our policy platform. Floodcoalition.Org.

- Almiron, N., & Xifra, J. (2019). Climate change denial and public relations: Strategic communication and interest groups in climate inaction. Routledge.

- Andonova, L. B., Betsill, M. M., & Bulkeley, H. (2009). Transnational Climate governance. Global Environmental Politics, 9(2), 52–73. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/glep.2009.9.2.52

- Association of Defense Communities. (2019). Implementing the defense community infrastructure program: A survey of projects ready to enhance military value (Issue March).

- Bansard, J. S., Pattberg, P. H., & Widerberg, O. (2017). Cities to the rescue? Assessing the performance of transnational municipal networks in global climate governance. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 17(2), 229–246. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-016-9318-9

- Barnett, J., & O’Neill, S. (2010). Maladaptation. Global Environmental Change, 20(2), 211–213. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.11.004

- Barnett, J., & Palutikof, J. P.. (2014). The limits to adaptation: A comparative analysis. In J.P. Palutikof, S.L. Boulter, J. Barnett, & D. Rissik (Eds.), Applied Studies in Climate Adaptation (pp. 231–240).). Wiley Blackwell.

- Betsill, M. M., & Bulkeley, H. (2006). Cities and the multilevel governance of Global climate change. Global Governance, 12(2), 141–159. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/27800607

- Bierbaum, R., Lee, A., & Smith, J. (2014). Ch. 28 adaptation, climate change impacts in the United States: The third national climate assessment.

- Billig, M. (1997). Discursive, rhetorical and ideological messages. In M. Wetherell, S. Taylor, & S. Yates (Eds.), Discourse theory and practice: A reader (pp. 210–221). Sage.

- Bolsen, T., Palm, R., & Kingsland, J. T. (2019). The impact of message source on the effectiveness of communications about climate change. Science Communication, 41, 464–487. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547019863154

- Bouteligier, S. (2013). Cities, networks, and global environmental governance : Spaces of innovation, places of leadership. Routledge.

- Brulle, R., & Timmons, J. R. (2021, April 23). What obstruction to Biden’s climate initiative will look like. The Hill.

- Brulle, R. J. (2014). Institutionalizing delay: Foundation funding and the creation of U.S. climate change counter-movement organizations. Climatic Change, 122(4), 681–694. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-1018-7

- Brulle, R. J. (2019). Networks of opposition: A structural analysis of U.S. climate change countermovement coalitions 1989–2015. Sociological Inquiry, xx(x), 1–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12333

- Bulkeley, H. (2000). Discourse coalitions and the Australian climate change policy network. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 18(6), 727–748. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/c9905j

- Bulkeley, H., Andonova, L. B., Betsill, M. M., Compagnon, D., Hale, T., Hoffmann, M., Newell, P., Paterson, M., Roger, C., & VanDeveer, S. D. (2014). Transnational climate change governance. Cambridge University Press.

- Bulkeley, H., & Betsill, M. (2005). Rethinking sustainable cities: Multilevel governance and the “urban” politics of climate change. Environmental Politics, 14(1), 42–63. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0964401042000310178

- Bulkeley, H., & Schroeder, H. (2012). Beyond state/non-state divides: Global cities and the governing of climate change. European Journal of International Relations, 18(4), 743–766. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066111413308

- Burawoy, M. (1998). The extended case method. Sociological Theory, 16(1), 4–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/0735-2751.00040

- CCS Staff. (2019). The center for climate and security: Events. Climateandsecurity.Org.

- Clary, J., & Grootendorst, G. (2013). Economic impact of the DoD in Hampton Roads (Issue October). https://www.nngov.com/DocumentCenter/View/5948

- CNA Military Advisory Board. (2007). National security and the threat of climate change.

- Cook, J.. (2019). Understanding and countering misinformation about climate change. In I. Chiluwa & S. Samoilenko (Eds.), Handbook of research on deception, fake news, and misinformation online (pp. 281–306).

- Cummings, L. (2014). The “trust” heuristic: Arguments from authority in public health. Health Communication, 29(10), 1043–1056. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2013.831685

- Delorme, D. E., Stephens, S. H., & Hagen, S. C. (2018). Transdisciplinary sea level rise risk communication and outreach strategies from stakeholder focus groups. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 8, 13–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-017-0443-8

- Diez, T., von Lucke, F., & Wellmann, Z. (2016). The securitisation of climate change: Actors, processes and consequences. Routledge.

- Dunlap, R. E., & McCright, A. M. (2003). Defeating Kyoto : The conservative movement ‘ s impact on U. S. climate change policy. Social Problems, 50(3), 348–373. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2003.50.3.348

- Dunlap, R. E., & McCright, A. M. (2010). Climate change denial: Sources, actors and strategies. In C. Lever-Tracy (Ed.), Routledge handbook of climate change and society (pp. 240–259). Routledge.

- Dunlap, R. E., & McCright, A. M. (2011). Organized climate change denial. In J. S. Dryzek, R. B. Norgaard, & D. Schlosberg (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of climate change and society (pp. 144–160). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199566600.003.0010.

- Eilperin, J., Dennis, B., & Ryan, M. (2019, April 8). As White House questions climate change, U.S. military is planning for it. The Washington Post.

- Esposo, S. R., Hornsey, M. J., & Spoor, J. R. (2013). Shooting the messenger: Outsiders critical of your group are rejected regardless of argument quality. British Journal of Social Psychology, 52(2), 386–395. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12024

- Farrell, J., McConnell, K., & Brulle, R. (2019). Evidence-based strategies to combat scientific misinformation. Nature Climate Change, 9(3), 191–195. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0368-6

- Fischer, F. (2003). 4 Public policy and discourse analysis. In Reframing public policy: Discursive politics and deliberative practices (pp. 73–93). Oxford University Press.

- Fischer, F. (2019). Knowledge politics and post-truth in climate denial: On the social construction of alternative facts. Critical Policy Studies, 13(2), 133–152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2019.1602067

- Fischer, F. (2020). Post-truth politics and climate denial: Further reflections. Critical Policy Studies, 14(1), 124–130. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2020.1734846

- Fisher, D. R. (2013). Understanding the relationship between subnational and national climate change politics in the United States: Toward a theory of boomerang federalism. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 31(5), 769–784. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/c11186

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363

- Frug, G. E., & Barron, D. J. (2013). City bound: How states stifle urban innovation. Cornell University Press.

- Fuhr, H., Hickmann, T., & Kern, K. (2018). The role of cities in multi-level climate governance: Local climate policies and the 1.5°C target. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 30, 1–6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2017.10.006

- Fünfgeld, H. (2015). Facilitating local climate change adaptation through transnational municipal networks. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 12, 67–73. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2014.10.011

- Goh, K. (2020). Flows in formation: The global-urban networks of climate change adaptation. Urban Studies, 57(11), 2222–2240. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018807306.

- Goldberg, M. H., Gustafson, A., Ballew, M. T., Rosenthal, S. A., & Leiserowitz, A. (2019). A social identity approach to engaging Christians in the issue of climate change. Science Communication, 41(4), 442–463. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547019860847.

- Gordon, D. J. (2018). Global urban climate governance in three and a half parts: Experimentation, coordination, integration (and contestation). Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 9(6), 1–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.546

- Griggs, G., Árvai, J., Cayan, D., DeConto, R., Fox, J., Fricker, H. A., Kopp, R. E., Tebaldi, C., & Whiteman, E. (2017). Rising seas in California. April. http://www.opc.ca.gov/webmaster/ftp/pdf/docs/rising-seas-in-california-an-update-on-sea-level-rise-science.pdf

- Hajer, M., & Versteeg, W. (2005). A decade of discourse analysis of environmental politics: Achievements, challenges, perspectives. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 7(3), 175–184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15239080500339646

- Hajer, M. A. (1993). Discourse coalitions and the institutionalization of practice: The case of acid rain in britain. In The argumentative turn in policy analysis and planning (pp. 43–76). Routledge.

- Hallegatte, S., & Corfee-Morlot, J. (2011). Understanding climate change impacts, vulnerability and adaptation at city scale: An introduction. Climatic Change, 104(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-010-9981-8

- Harper, S. (2010, December 3). Navy admiral urges action in dealing with climate. The Virginian-Pilot.

- Hejny, J. (2018). The Trump administration and environmental policy: Reagan redux ? Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 8(2), 197–211. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-018-0470-0

- Hoffman, A. J. (2011). Talking past each other? Cultural framing of skeptical and convinced logics in the climate change debate. Organization and Environment, 24(1), 3–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026611404336

- Hoffman, A. J. (2015). Bridging the cultural schism. In How culture shapes the climate change debate (pp. 48–69). Stanford University Press.

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2003). Unraveling the central state, but how? Types of Multi-Level Governance, 97(2), 233–243.

- Hornsey, M. J., & Fielding, K. S. (2020). Understanding (and reducing) inaction on climate change. Social Issues and Policy Review, 14(1), 3–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12058.

- HRPDC. (2016). Request for proposals: Multidisciplinary planning services for Hampton Roads Region - Norfolk and Virginia Beach Joint Land Use Study.

- Hughes, S. (2017). The politics of urban climate change policy: Toward a research agenda. Urban Affairs Review, 53(2), 362–380. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087416649756

- Hughes, S., Chu, E., & Mason, S. (2018). Climate change in cities: Innovations in multi-level governance. Springer.

- Jenkins-Smith, H., Silva, C. L., Gupta, K., & Ripberger, J. T. (2014). Belief system continuity and change in policy advocacy coalitions: Using cultural theory to specify belief systems, coalitions, and sources of change. Policy Studies Journal, 42(4), 484–508. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12071

- Johnson, C., Toly, N., & Schroeder, H. (2015). The urban climate challenge : Rethinking the role of cities in the global climate regime. Routledge.

- Juhola, S., Glaas, E., Linner, B. O., & Neset, T. S. (2016). Redefining maladaptation. Environmental Science and Policy, 55, 135–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.09.014

- Kalafatis, S. E., & Lemos, M. C. (2017). The emergence of climate change policy entrepreneurs in urban regions. Regional Environmental Change, 17(6), 1791–1799. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-017-1154-0

- Lee, T. (2013). Global cities and transnational climate change networks. Global Environmental Politics, 13(1), 108–127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00156

- Leiserowitz, A. (2006). Climate change risk perception and policy preferences: The role of affect, imagery, and values. Climatic Change, 77(1–2), 45–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-006-9059-9

- Lewandowsky, S. (2021). Climate change, disinformation, and how to combat It. Annual Review of Public Health, 42, 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3693773.

- Light, S. E. (2015). The military-environmental complex. Environmental Law Reporter News & Analysis, 45, 10763–10769.

- Lyons, B. A., Hasell, A., Tallapragada, M., & Jamieson, K. H. (2019). Conversion messages and attitude change: Strong arguments, not costly signals. Public Understanding of Science, 28(3), 320–338. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662518821017

- Marquart-Pyatt, S. T., McCright, A. M., Dietz, T., & Dunlap, R. E. (2014). Politics eclipses climate extremes for climate change perceptions. Global Environmental Change, 29, 246–257. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.10.004

- McCann, E., & Ward, K. (2012). Assembling urbanism: Following policies and “studying through” the sites and situations of policy making. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 44(1), 42–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/a44178

- McCright, A. M., Charters, M., Dentzman, K., & Dietz, T. (2016). Examining the effectiveness of climate change frames in the face of a climate change denial counter-frame. Topics in Cognitive Science, 8(1), 76–97. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12171

- McCright, A. M., & Dunlap, R. E. (2000). Challenging global warming as a social problem: An analysis of the conservative movement’s counter-claims. Social Problems, 47(4), 499–522. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3097132

- Mccright, A. M., & Dunlap, R. E. (2011). The politicization of climate change And polarization in the American public’s views of global warming, 2001-2010. The Sociological Quarterly, 52(2), 155–194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2011.01198.x

- Measham, T. G., Preston, B. L., Smith, T. F., Brooke, C., Gorddard, R., Withycombe, G., & Morrison, C. (2011). Adapting to climate change through local municipal planning: Barriers and challenges. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 16(8), 889–909. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-011-9301-2

- Mols, F., Bell, J., & Head, B. (2018). Bridging the research-policy gap: The importance of effective identity leadership and shared commitment. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 16(1), 145–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1332/174426418 ( 15378681300533

- Moser, S. C. (2016). Reflections on climate change communication research and practice in the second decade of the 21st century: What more is there to say? Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 7(3), 345–369. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.403

- Moser, S. C., & Dilling, L. (2011). Communicating climate change: Closing the science-action gap. In J.S. Dryzek, R.B. Norgaard, & D. Schlosberg (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of climate change and society (pp. 161–174). Oxford University Press.

- Moser, S. C., & Ekstrom, J. A. (2010). A framework to diagnose barriers to climate change adaptation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(51), 22026–22031. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1007887107

- National Ocean Service, NOAA, & U.S. Department of Commerce. (2015). Coastal flooding in California: What you need to know. http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/news/dec15/california-flooding.html

- Nelson, W., & Luetz, J. M. (2019). What can we learn from Pope Francis about change management for environmental sustainability? A case study on success factors for leading change in change-resistant institutional environments. In W. L. Filho, & A. C. McCrea (Eds.), Sustainability and the humanities (pp. 503–524). Springer International Publishing.

- Newell, P., Pattberg, P., & Schroeder, H. (2012). Multiactor governance and the environment. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 37(1), 365–387. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-020911-094659

- Nisbet, M. C.. (2009). Communicating climate change: why frames matter for public engagement. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 51(2), 12–23.

- Oberlack, C. (2017). Diagnosing institutional barriers and opportunities for adaptation to climate change. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 22(5), 805–838. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-015-9699-z

- Office of the Under Secretary of Defense Acquisition Technology and Logistics. (2014). Memo: DoD climate preparedness and resilience planning pilots.

- Oreskes, N., & Conway, E. M. (2010). Merchants of doubt: How a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming. Bloomsbury Press.

- Peck, J., & Theodore, N. (2012). Follow the policy: A distended case approach. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 44(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/a44179

- Purkarthofer, E. (2018). Diminishing borders and conflating spaces: A storyline to promote soft planning scales. European Planning Studies, 26(5), 1008–1027. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1430750

- Rieh, S. Y. (2010). Credibility and cognitive authority of information. In M.J. Bates & M.N. Maack (Eds.), Encyclopedia of library and information sciences (3rd ed.), pp. 1337–1344). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1081/e-elis3-120044103

- Romero-Lankao, P., Bulkeley, H., Pelling, M., Burch, S., Gordon, D. J., Gupta, J., Johnson, C., Kurian, P., Lecavalier, E., Simon, D., Tozer, L., Ziervogel, G., & Munshi, D. (2018). Urban transformative potential in a changing climate. Nature Climate Change, 8(9), 754–756. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0264-0

- Rosenzweig, C., & Solecki, W. (2018). Action pathways for transforming cities. Nature Climate Change, 8(9), 754–756. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0264-0

- Rydin, Y. (2021). Discourse, knowledge and governmentality: The influence of foucault. In Theory in planning research (pp. 149–169). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-33-6568-1.

- Salon, D., Murphy, S., & Sciara, G. C. (2014). Local climate action: Motives, enabling factors and barriers. Carbon Management, 5(1), 67–79. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4155/cmt.13.81

- San Diego Economic Development Corporation. (2016, June 24). EDC, SDMAC talk regional defense sector in nation’s capital.

- Schroeder, H., Burch, S., & Rayner, S. (2013). Novel multisector networks and entrepreneurship in urban climate governance. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 31(5), 761–768. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/c3105ed

- SDMAC. (2016). 8th Annual San Diego Military Economic Impact Study.

- Sharp, L., & Richardson, T. (2001). Reflections on foucauldian discourse analysis in planning and environmental policy research. Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, 3(3), 193–209. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jepp.88

- Shi, L. (2019). Promise and paradox of metropolitan regional climate adaptation. Environmental Science and Policy, 92(April 2018), 262–274. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.11.002

- Steele, W., Mata, L., & Fünfgeld, H. (2015). Urban climate justice: Creating sustainable pathways for humans and other species. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 14, 121–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2015.05.004

- Steinhilber, E. E., Boswell, M., Considine, C., & Mast, L. (2016). Hampton Roads sea level rise preparedness and resilience intergovernmental pilot project, Phase 2 report: Recommendations, accomplishments and lessons learned.

- Sweet, W. V., & Marra, J. J. (2016). 2015 State of U. S. “ Nuisance” tidal flooding. 2013–2017.

- Tahvilzadeh, N., Montin, S., & Cullberg, M. (2017). Functions of sustainability: Exploring what urban sustainability policy discourse “does” in the gothenburg metropolitan area. Local Environment, 22(May), 66–85. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2017.1320538

- Teicher, H. M. (2019). Climate allies: How urban/military interdependence enables adaptation. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- The Economist. (2018, February 22). One arm of the Trump administration thinks climate change is a security threat. The Economist.

- Union of Concerned Scientists. (2016). The US military on the front lines of rising seas. http://www.ucsusa.org/sites/default/files/attach/2016/07/front-lines-of-rising-seas-key-executive-summary.pdf

- U.S. Department of Defense, & Office of Economic Adjustment. (2015). Defense spending by state FY 2015.

- van Doren, D., Driessen, P. P. J., Runhaar, H., & Giezen, M. (2018). Scaling-up low-carbon urban initiatives: Towards a better understanding. Urban Studies, 55(1), 175–194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016640456

- Walton, D. (1997). Appeal to expert opinion: Arguments from authority. Penn State University Press.

- Watts, M. (2017). Commentary: Cities spearhead climate action. Nature Climate Change, 7(8), 537–538. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3358

- Wolsko, C. (2017). Expanding the range of environmental values: Political orientation, moral foundations, and the common ingroup. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 51, 284–294. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.04.005

- Yin, R. K. (2013). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). SAGE.