ABSTRACT

The attention that has been drawn to urban experimentation has contributed to new knowledge of the role of local governance for a sustainable transition. Still, there remains little knowledge of how municipalities can foster experimentation and that may result in real change across the protected spaces of experimentation and the existing policy structures. This paper aims at exploring how experimental governance result in real policy change over time by reviewing related discussions from the cross-disciplinary fields of sustainability transition and collaborative innovation, and by discussing findings from a longitudinal case study of an emerging innovation for sustainable mobility services in Oslo. This longitudinal study shows how experimental governance have played various roles at different times in the emerging innovation: promoting innovation, destabilising existing policy arrangements, transforming institutional routines and co-creating shared interests. The findings demonstrate the critical co-evolutionary dynamics of experimental governance, transforming existing policy structures over time.

Introduction

Cities have been identified as being particularly important locations in need of sustainable transitions, in the context of the increased urgency of climate-related pressures – for example, population density and emissions from transport. Cities have also been the place for many initiatives of urban experimentation. Early initiatives were driven by social movements, but, in recent decades, established actors in the market, civil society and knowledge infrastructures have sought to transform society (Bulkeley & Betsill, Citation2005; Grin, Citation2020; Ostrom, Citation2010; von Wirth et al., Citation2019; Wolfram et al., Citation2016).

Recently, a new wave of focus has emerged, in which local governance has a key role in urban experimentation (Hofstad & Vedeld, Citation2021; Mukhtar-Landgren et al., Citation2019; Nieminen et al., Citation2021). This has raised conceptual discussions related to the various roles of municipalities, in initiating, leading and collaborating for sustainable development (Kronsell & Mukhtar-Landgren, Citation2018; Mukhtar-Landgren et al., Citation2019; Nieminen et al., Citation2021). Moreover, different roles can be found in different parts of the municipalities and they can shift over time. Still, knowledge is limited about how local governmental policies can foster experimentation that results in sustainable transition.

In this regard, the attention to local governance is consistent with the general literature on policy experimentation, which contends that there exists little knowledge about how governmental policy can generate dynamics that result in sustainable transition. Policy changes resulting from experimentation are often taken for granted (McFadgen & Huitema, Citation2018; Voß & Simons, Citation2018). In particular, there is little discussion about the transition dynamics across the two levels identified in the literature – of the protected spaces for experimentation and of the incumbent structures of existing policy (Huitema et al., Citation2018; Kivimaa et al., Citation2017; Sengers et al., Citation2019). The attention to urban experimentation has emphasised the need to understand the impact of governmental policy in the city as a whole (Fuenfschilling et al., Citation2019; Grin, Citation2020; von Wirth et al., Citation2019).

Thus, the focus on urban experimentation has contributed with a useful framework to sort the various roles of governmental policy, of the nurturing of change in protected spaces and of destabilising factors in existing policy. It has also incorporated discussions from various fields of literature that are helpful in creating further knowledge on the dynamics of experimental governance and policy change. This paper aims to contribute to the creation of knowledge on the dynamics of how experimental governance may be nurturing, but also obstructing, sustainable transition and how obstacles can be overcome and result in real policy changes over time. The paper enhances the conceptualisation of these dynamics, by bringing in related discussions from the fields of sustainability transition (Köhler et al., Citation2019; Markard et al., Citation2012) and collaborative innovation (Sørensen & Torfing, Citation2011; Torfing et al., Citation2016). Both fields of literature have contributed to understanding the various roles of governmental policy across the two levels of experimentation and existing policy structures.

Moreover, the need for in-depth studies to understand the underlying dynamics has been called for (Kronsell & Mukhtar-Landgren, Citation2018; Nieminen et al., Citation2021). This paper explores the issues of experimental governance and policy change empirically by discussing findings from a longitudinal case study of emerging innovation in sustainable mobility services: the public charging stations for electric vehicles (EVs) in the city of Oslo in 2007–2017. This emerging innovation is an interesting case that demonstrates how local governance nurtures, but also obstruct, transition. By investigating the case in a longitudinal research design, this paper contributes with critical understanding of how experimental governance can create change over time (Langley et al., Citation2013; Pettigrew, Citation1990).

The innovation studied was fostered by a governmental decision to build 400 charging stations for EVs in 2007. A major challenge was that the governmental decision was assigned to an agency that had an existing policy arrangement that largely conflicted with the new governmental goal. Also, there was no market for EVs at this time, and charging stations were not ready-made products and had to be developed. Nevertheless, this governmental goal was implemented, on time and within budget, and resulted further in a regionally based infrastructure, which by the end of this study in 2017 had reached 1,260 publicly available EV charging stations. Thus, the governmental goal was realised despite many challenges rooted in existing policies, which may help us to understand how experimental governance can promote innovation, destabilise existing policy arrangements, transform institutional routines and co-create shared interests.

The next section discusses theoretical debates of experimental governance and policy change. This is followed by a section that introduces and discusses the methods of a longitudinal case used in this study. Then, an extended section presents the findings of the empirical study of the public charging stations for EVs in Oslo. The final section discusses the empirical findings, draws conclusions about the theoretical points and delineates some points for further research.

Experimental governance and policy change

Recent literature on experimental governance has called attention to the critical role of local governance in their legitimacy as formal decision-making institutions (Hofstad & Vedeld, Citation2021; Kronsell & Mukhtar-Landgren, Citation2018). The legitimacy rests on two functions, the democratic function and the formal regulatory function. Cities are local governmental units, ruled by elected politicians and administrated by professionals. Indeed, there are differences between municipalities in their functions, and three ideal typical roles are identified: as promoter, enabler and partner.

Municipalities may act as promoters, initiating and leading urban experimentation by use of formal steering instruments, for example by allocating funding to experiments. This role can follow a strictly hierarchical top–down logic, with politicians in leading positions (Kronsell & Mukhtar-Landgren, Citation2018). The role as enabler also follows a top–down logic, but less active in style. Local government may open up for opportunities and facilitate for collaboration, as for example by the use of measures for creating meeting places (Bulkeley & Betsill, Citation2005; Mukhtar-Landgren et al., Citation2019). Municipalities may also act as partners, taking an actively part in the collaboration, as responsible for public services and owner of public facilities. This role differs from the other two in entailing a horizontal logic of shared leadership, in which several partners have complementary roles (Kronsell & Mukhtar-Landgren, Citation2018; Nieminen et al., Citation2021).

Importantly, a municipality is not a unitary actor but consists of many parts with various responsibilities, competencies and priorities. As a result, one part of the municipality may take on the role of a promoter, whereas another part may act as a partner. The roles may also shift over time. This plurality can be an inhibiting factor if their interests are contrasting. Experimentation can also be hindered if administrative routines are ‘sticky’ (Hofstad & Vedeld, Citation2021; Mukhtar-Landgren et al., Citation2019). Yet, as brought to attention in this paper, there is little knowledge about how municipalities take on and shift between the different roles, and how obstacles can be overcome and result in real policy change over time. In order to build knowledge of these dynamics, this paper brings in related discussions from the fields of collaborative innovation and sustainability transitions. The three ideal-typical roles of municipalities are grounded in these cross-disciplinary literatures.

The field of collaborative innovation has contributed to the understanding of a similar dynamic of experimentation and existing policy structures. Here, the focus is on the processes at the local level, in the co-creation of interests in practical problem-solving processes (Ansell & Torfing, Citation2014; Torfing et al., Citation2016). According to this literature, politicians, public agencies, users, private companies, civil society organisations and other stakeholders with a shared interest tend to come together in governance networks (Crosby et al., Citation2017; Sørensen & Torfing, Citation2011). Still, their shared interest does not necessarily result in sustainable solutions. Conflict and mistrust can arise, and may hinder the development of sufficiently strong relationships, whilst interactions can also be too sturdy and prevent the generation of novel results (Ansell & Torfing, Citation2014; Hartley et al., Citation2013; Termeer & Dewulf, Citation2019). Thus, the literature may contribute to understand the underlying dynamics of how shared interest may nurture change, but also lock in existing activity and hinder policy change.

In the field of collaborative innovation, change transforms in a setting of institutionalised routines of political life (Hartley et al., Citation2013; March & Olsen, Citation1984). The institutional routines are not constant but change through continuous processes of interpretation and adaptation. People simply learn by trial and error, and by doing more of what results in positive outcomes. Organisations do not necessarily make better choices over time, given that certain rules of appropriate behaviour influence their choices. Institutions create certain elements of an order, of what makes sense and what is taken for granted in a given organisational context. However, recent studies have stressed how modern social problems add a complicating factor, in that major problems cut across existing policy domains. The problem of climate change, for example, overlaps the policy domains of health, energy and transport (Head & Alford, Citation2015; Peters & Tarpey, Citation2019). Thus, policy change faces challenges in the vastness of the problems to be solved, and in the various expectations in different policy domains. Public values are assessed in social outcomes, and may change character over time and from place to place, related to shifting interests and priorities of involved actors (Crosby et al., Citation2017).

In the sustainability transition literature, the complex challenge of the existing structure is at the core of attention, framed in the analytical dimensions of niches and socio-technical systems. Niches refer to the processes of experimentation in protected spaces (Hoogma et al., Citation2002; Smith & Raven, Citation2012). The experimentation is needed for the improvement of technical deficits, but also for the maturing of the novel ideas and the building of a social network of supporters, partners and financial backers. This may sound neat and easy, but this is certainly not the case. Niches need to fight against existing technology and beliefs in the excellence of the technology in the incumbent socio-technical systems. The socio-technical system is the notion for the social structures that exist in the activities of actors. Each actor is a member of several social groups, such as technicians, politicians, pressure groups and customers. As members of these various groups, they hold certain rule-sets that form their actions and beliefs of what is achievable, in a policy rationale (Geels, Citation2004; Hodson et al., Citation2017). There are also rule-sets across groups, in interrelated belief systems. These interrelated rule-sets form complex social systems, which are difficult to change given their tangled activities, and the systems become locked-in, in deep-seated structures.

However, socio-technical systems are not constant. Change is considered to co-evolve in interrelated activities of temporal elements across niches and socio-technical systems – for example, new technologies, changed legislations, consumer patterns and political trends. Moreover, several studies have ascribed governmental policy and politics a central role in this co-evolution (Avelino et al., Citation2016; Meadowcroft, Citation2011; Smith et al., Citation2005). In one sense, innovation policies represent stabilising social structures in prevailing rationales of the actors that implement the policy. On the other hand, governmental policy can destabilise existing systems and create new ones (Hoogma et al., Citation2002; Raven et al., Citation2016). Policy mandates can define demonstration projects that offer the prospects of niches. General governmental support can also provide spaces for local experimental initiatives. Thus, the sustainability transition literature has contributed to acknowledge governmental policy both as a constraint for the stabilising of incumbent systems, and as a tool for nurturing change.

The fields of collaborative innovation and sustainability transition have both given governmental policy a critical role in the need to overcome modern social problems. The two fields have also demonstrated the complexity of the concept of governmental policy, in how the policy operates at many levels, at various points in time and over time. Also, both fields have targeted the difficulties of changing existing policy, in the institutionalised routines of political life and the incumbent systems of existing policy structures. Moreover, both fields have identified a dynamic that can change the existing policy structures, in the co-creation among various actors in governance networks, and in the co-evolution among novelties in niches and existing structures in socio-technical systems. These two dynamics describe the layered arrangement of experimental governance and policy change in two different ways that can extend the knowledge of how local governance can facilitate for sustainable transition.

Collaborative innovation has focused on how actors with shared political interests create a space for creating policy together in networks. Sustainability transition, on the other hand, has emphasised the need for governmental policy to nurture such protected spaces. The field of collaborative innovation has also emphasised how existing institutions create certain elements of order in a given organisational context, whereas the field of sustainability transition has outlined the problem of locked-in rationales in existing policy structures. These contradicting aspects of governmental policy fit well with the various and shifting roles pointed at in the literature of experimental governance, as promoter, enabler and partner.

Moreover, the many concepts of governmental policy in these two fields of literature may help to sort out and clarify the complexity of experimental governance and policy change, for building a more solid ground for the reasoning of similar patterns of roles and dynamics in empirical studies. Thus, the theoretical constructs discussed here are tentative identifications of patterns before a more open inductive reasoning of the underlying dynamics of various roles of experimental governance.

Method

This paper is based on findings from a longitudinal case study of the emerging innovation of the new public charging stations for EVs in the city of Oslo during the period 2007–2017. This emerging innovation is a selected case that provides empirical insights into the theoretical outlooks discussed, and how experimental governance may foster policy change and create sustainable transition.

A longitudinal case study (Langley et al., Citation2013; Pettigrew, Citation1990) enables an investigation of how a phenomenon develops in detail and over time, applying the methods of process research. These methods build on an overall view of innovation and change as being too complex to be broken down into independent and dependent variables. There is a need to study innovation and change in its real social setting, by focusing on the action of real people in their given settings and within a given time. In the present study, the process methods were considered relevant for studying the many temporal elements that initiate, drive and hinder the emerging innovation of public charging stations for EVs over time, and for testing the many explanations in the theories of experimental governance and policy change.

When developing a theory, the first step is to reconstruct empirical patterns, and then search for the theoretical explanations while scrutinising the many possible explanations for the observable outcomes. Yet, as pointed at, existing theoretical constructs characterise tentative patterns before a more open inductive reasoning (Langley et al., Citation2013; Pettigrew, Citation1990). In these steps, various strategies were applied: process-tracing to develop a historical outline of how the charging stations emerged, narratives to reconstruct and explain detailed stories of how and why human actions unfolded, and temporal bracketing to divide explanations into discrete time periods and phases.

Data was collected and analysed using many methods: personal interviews, focus group interviews, document analysis, archival studies, visual inspections of the technical equipment and statistical analysis. The data collection and the analysis were parallel processes, where preliminary results gave rise to new rounds of data collection. Data collection was conducted both in real time and retrospectively, to understand the longitudinal nature of the process. The next parts give details about the data collection and analysis.

The process started in 2009 with the mapping of the innovation and its key actors. Data was collected using publicly available information, most of which was collected from local newspapers, the websites of key actors, and newsletters from the city of Oslo. In addition, initial meetings with the Traffic Agency, the public entity developing the charging stations, and with the private firm developing the first type of charging stations provided critical insight into the early situation.

The data collection and analysis were extended in 2011, with a reconstruction of the emerging historical process. Personal interviews were conducted with all key actors involved: the politician who initiated the governmental goal, the environmental organisations that lobbied for it, the team of public managers that developed the public charging stations within the Traffic Agency, the private firms that delivered the first and the second type of charging stations, and the user organisation that helped to develop it. This amounted to 14 personal interviews. The interviews were open, allowing interviewees to describe their points of view of how the public charging stations for EVs had developed, how they contributed, the challenges they faced and the successes they experienced at various phases.

The interview data resulted in broad descriptions, in narratives, displaying a historical outline, but also a more complex reality. The reconstructed patterns were discussed in two focus group interviews with the group of public managers from the Traffic Agency in 2012 and in 2014. In 2012, the Traffic Agency had gone through a reorganisation, becoming the larger unit of the Agency for Urban Environment. However, this article refers to the Traffic Agency as the public entity throughout the text, because the reorganisation is not an issue in this paper.

The complexity patterns detected were elaborated upon in a final extensive round of data collection in 2014-2017. The extensiveness was partly a result of the fact that the development of the new public charging stations did not stop at the initial goal of 400, but continued in new governmental goals of an additional 100 per year in 2012, and an additional 200 from 2014. This round of data collection included an extensive study of the governmental policy for EVs in a document analysis of white papers, green papers and hearings. It also involved the collection of archive material from the Traffic Agency, to understand how the agency acted on the policy and interacted with other actors (public agencies, politicians, private producers and non-profit organisations). The archive material mainly comprised of letters, but included also notes and annual reports. These two document studies supplemented the previous data collection. In addition, this round of data collection included statistical materials concerning the EV market, visual inspections of the technical artefacts of the charging stations and a study of the public discussion in web-based EV forums and national newspapers.

Results

This section presents the empirical findings of the issues of experimental governance and policy change for the emerging innovation of public charging stations for EVs in Oslo, by showing how a governmental decision was promoting the innovation, destabilising existing policy arrangements, transforming institutional routines and co-creating shared interests.

Governmental decision promoting innovation

The public charging stations for EVs in Oslo was initiated by a City Council decision, whereby the City Council requested: ‘the City Government to build 400 charging stations for EVs in the period 2008–2011’.Footnote1 This governmental decision had several aspects of the ideal typical role of promoter of experimental governance.

First and foremost, the City Council decision had its origins in a policy proposal of August 2007, which stated the policy aim of a political party:

It is an important mission for the Liberal Left Party to increase the number of EVs at the expense of cars that use fossil fuels. Our ambition is to make Oslo the leading city to cater for EVs. To reach this ambition, we need reserved parking places for charging EV batteries. (…) Building 400 charging stations will contribute to making the use of EVs more attractive and user-friendly.Footnote2

(…) EVs have many economic benefits to enhance their use. Charging stations must be added in addition to earlier measures, including e.g. free passage on toll roads, free municipal parking, access to bus lanes, and VAT exemption and other taxes.Footnote3

From this, one could argue that there was an existing policy rationale for EVs. However, it is important to remember that in 2007, when the proposal was made, there were only 1,457Footnote4 registered EVs in Norway. In 2020, the total number of EVs in Norway was 340,002. Thus, the policy rationale in the small niche market of 2007 was not the same as it was in 2020. Still, one could argue that there existed general governmental support, that can have provided a space for experimentation at the local level. Yet, the City Council decision was critical, and can be regarded as a policy mandate that offered the prospects of niches.

Table 1. Legislations for EVs in Norway.

Destabilising existing policy arrangements

This City Council decision was part of the municipal budget for Oslo in 2008. Being part of the budget meant that the City Council had allocated funding for developing the governmental policy. The budgetary post also meant that the City Council decision was assigned to a public agency to be put into practice. This procedure can look like a simple top–down logic of implementation of a governmental decision. However, when looking into this case in detail, the data shows that this implementation was not simple. The governmental decision conflicted with the existing policy structures. Still, the public agency did put the governmental decision into practice. One may argue that the assignment held a critical legitimacy that had the dynamic of destabilising existing policy arrangements.

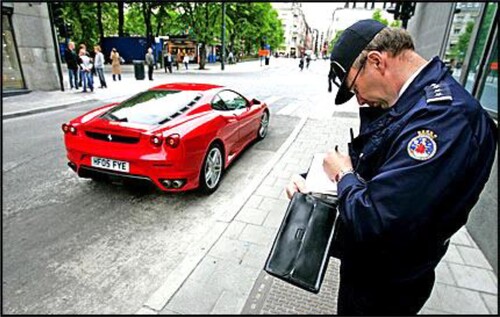

The budgetary assignment was sent to the Traffic Agency. This agency had no existing services for EVs, nor any other sustainable mobility services. Its activity was stated in its organisational goal: ‘The Traffic Agency works to ensure a safe city with properly passable streets and an adequate number of accessible parking spots’.Footnote5 Over time, its dominant routines had become the monitoring of parking and the imposition of fines, evolving out of the delegated power in the law on parking pursuant to the Norwegian Road Traffic Act of 1973. Two-thirds of the employees in the agency worked as parking agents, and the rest administrated and planned the system.Footnote6 illustrates their work.

Parking tickets and fines had also become an important source of income, which amounted to 82 per cent of total revenue in 2008.Footnote7 The new public service of charging stations, on the other hand, did not bring any profits. The public managers and workers were indignant. They regarded free charging stations as constituting a reduction in the total number of parking spots for which fines could be levied. The following statement by a public manager in the Traffic Agency in 2009 captures the challenge:Footnote8

We are a parking agency. We do not have a great interest in charging stations for EVs, especially since we lose money for every station we build. For us, it is a reduction in income.

The new assignment of charging stations broke with the existing policy arrangements for mobility services in Oslo. However, the existing structures also created a basis for the new assignment. The Traffic Agency’s self-constituted authority as a parking agency was an outcome of its organisational form, in which monitoring through fines was defined by means of an estimated target number of fines per year. The governmental decision was designed in a similar way, as an estimated number of public charging stations to be built per year. Thus, existing policy arrangements may have locked in and counteracted innovative thinking, but can also have created pressures that destabilised existing structures, and made the transformation more efficient.

Transforming administrative routines

Looking more closely at the emerging innovation at the Traffic Agency level shows how certain aspects of the governmental decision contributed to destabilising, but also transforming administrative routines in the public agency. The transformation is based on the institutional routines of the Traffic Agency, changing the political life in the public agency in continuous processes of interpretation and adaptation. Three critical processes can illustrate the transformation.

Firstly, the City Council decision requested the precise number of 400 charging stations for EVs. At the outset, the project team within the Traffic Agency that was handed the assignment stated that they felt that 400 charging stations was an extremely high number. The statistics for Oslo show that only 311Footnote9 EVs were registered in 2007, which could support their point. They feared a scenario of ‘400 unused reserved parking places for EV-charging’.Footnote10 Their fear was related to their administrative routines as a parking agency, caring for the scarce number of parking places in the city. Their fear was an obstacle for the emerging innovation, but it was also a driver, which pushed the Traffic Agency to search for the best solutions to maximise the use of the charging stations.

Secondly, the City Council decision also included an expectation of rapid development to increase the number of charging stations from zero to 400 within a defined period of four years. This may seem unproblematic, but when the Traffic Agency was assigned the task in 2008, charging stations were not a ready-made product. The fact that the technological equipment was largely unavailable necessitated active involvement in developing the technology. As described by an employee in the Traffic Agency in 2009: ‘we just had to get started to be able to perform’.Footnote11 The precise numbers of charging stations and defined period triggered immediate action. The agency had a performance-oriented style, formed by the administrative routine of the estimated target number of fines per year in the budget.

Thirdly, as a public agency, the Traffic Agency issued calls for tenders to procure technological equipment. The first call to tenderFootnote12 did not result in any bidders. Then, one of the project members in the Traffic Agency came up with the idea to procure a related product, and they re-launched the call to tender as a development contract with an invitation to producers of this product. One year later they launched a second call to tender. This rose from a re-interpretation of the assignment based on their experiences with the design of the very first charging station and the charging station products that now was entering the market.Footnote13 Three years later, in 2012, they issued a third call to tender.Footnote14 This specified several technical details, such as the inclusion of various modes of charging, and displayed a mature buyer in a now-existing market for charging stations. The various actions taken at different times in the procurement processes demonstrate how the administrative routines transformed gradually over time, from novices to experts of public EV charging stations. Moreover, the procurement processes show how their action related to an emerging market for charging stations.

These three processes show how the City Council decision involved many continuous processes of interpretation and adaptation. Moreover, these processes were not limited to the public entity of the Traffic Agency, but co-evolved with other actors and organisations, and with ongoing activities in the overall society.

Co-creating shared interests

As shown in , the arrangements for EVs was not radically new in Norway. Actually, free parking had already been a priority for 15 years when the City Government of Oslo decided on the 400 charging stations.

The history of EV policy in Norway is critical to take into consideration in understanding how the charging stations for EVs developed in Oslo. In the early 1990s, two EV models – Think and Buddy – were developed in Norway. This was before the international automotive industry launched its EV models, and the two models played a central role in forming an early niche market. Think and Buddy shared some features that were typical for the early EV models. These EVs were small vehicles, lightweight and type-approved as motorcycles. By practically dominating the early market, the specificity of the two models created certain rule-sets. One of these rule-sets was particularly relevant for the case of the public charging stations in Oslo. A unique parking style evolved out of their small size and their type-approval, which made it legal to park in small spaces reserved for motorcycles. shows this parking style.

In 2007, the Traffic Agency started to fine drivers for this cross-parking style. The new fining practice infuriated the EV owners: a public entity had removed their lawful right of free parking on the municipal ground! They contacted the national user organisation for EVs (NEF). NEF discussed the situation with the City Council. The local newspapers picked up the case, and several environmental organisations engaged themselves in the public debate that followed. NEF had worked actively to improve the conditions for EVs in Norway since the early 1990s, and had collaborated with several environmental organisations in developing the legislation at the national level. However, NEF had never been directly involved in processes of change at the local level.

The need for charging stations soon emerged as an element in the debate. The issue had been raised earlier, but mainly by NEF and at the national level. Now, NEF, the environmental organisations and some of the politicians in the City Council, had come together in the interest of parking issues for EVs in Oslo. Their shared interests for EVs brought them together and created a common ground for co-creation. They started to discuss practical problems, such as the scarce number of parking places in Oslo, the required number of charging stations, charging technology and the designated locations for the charging stations. The various actors had different views on these practical issues, but they all had an interest in the outcome of building charging stations for EVs in Oslo. NEF had an interest in the need of improving the charging possibilities for their members, the EV owners. The environmental organisations were interested in public EV charging as a green measure, and the local politicians saw charging stations as a sustainable mobility service that could contribute to enhance the use of low emission vehicles in the city. Some of the politicians involved made the policy proposal of August 2007.

Based on these events, one could argue that it was the fining practice of the Traffic Agency for EV cross-parking that initially sparked a political process that resulted in the City Council’s decision of the 400 public charging stations. At least, the incident had a critical role in bringing actors together, and co-creating the innovation of the public charging stations for EVs in Oslo.

Discussion

This case study seeks to demonstrate the crucial role of experimental governance, as pointed at in recent literature on urban experimentation (Hofstad & Vedeld, Citation2021; Kronsell & Mukhtar-Landgren, Citation2018; Mukhtar-Landgren et al., Citation2019; Nieminen et al., Citation2021). Moreover, the study reveals how various forms of experimental governance played various roles at different points in time. This final part will discuss how the fields of collaborative innovation (Sørensen & Torfing, Citation2011; Torfing et al., Citation2016) and sustainability transition (Köhler et al., Citation2019; Markard et al., Citation2012) can contribute to conceptualise the underlying dynamics of these roles and outline a co-evolutionary dynamic of experimental governance.

The empirical results highlight the key role of the City Council decision, and how it can shed light on several aspects of the ideal-typical role of municipalities as promoters, following a hierarchical logic with politicians in leading positions (Kronsell & Mukhtar-Landgren, Citation2018). The City Council decision had its origin in a policy proposal, and was included in the municipal budget. The budgetary post meant that money was allocated to implement the governmental decision. Also, the budgetary procedure assigned the City Council decision in a top–down routine to a public agency to be put into practice.

Yet, as shown, the agency that was assigned the task had no existing services for EVs. Its dominant activity had become the monitoring of parking, institutionalised in the routines of ‘the parking agency’. Still, the public agency put the governmental decision into practice. Seeing the City Council decision through the lens of a niche, as described in the literature of sustainability transition (Hoogma et al., Citation2002; Smith & Raven, Citation2012), can contribute to target the processes of experimentation at the micro level, and how these processes involved the need to fight against the existing structures.

The City Council’s decision in some aspects contributed to destabilise, but also transform the administrative routines in the Traffic Agency, through a precise number of charging stations, and a defined period for the implementation. The existing routines in the Traffic Agency was oriented at numbers, in the estimated number of fines per year and in the scarce number of parking places in the city. Thus, the measurable attributes of the governmental goal mobilised the attention of the agency. It laid the foundations for transforming existing arrangements through continuous processes of interpretation and adaptation, processes acknowledged as a fundamental dynamic of institutional routines of political life by March and Olsen (Citation1983).

The three tenders also reveal how the agency gradually developed the charging stations, based on their experiences with existing solutions, the needs of the users, and the available technology in the market. Here it is important to bear in mind that the situation for EVs was very different from today, as demonstrated in the increase from 1,457 EVs in Norway in 2007 to 340,002 in 2020. This may correspond to a typical characteristic of a niche, nurturing and testing the novelty in an emerging market, as described in the literature of sustainability transitions (Hoogma et al., Citation2002; Köhler et al., Citation2019; Smith & Raven, Citation2012). However, the charging station case involved some critical differences from the typical characteristics of a niche. The task of the new sustainable mobility service was allocated to the agency in a hierarchical way, and the politicians that initiated the policy was not involved in developing the new service. Thus, the maturing of the novelty was without the initial champions and partners, which normally are associated with niches.

The initiation was a political process, which took place at the democratic level of the City Council, and was then handed over to the Traffic Agency to be put into practice, as a formal regulatory function. Thus, supporting the two critical functions of legitimacy as pointed out in the literature of experimental governance (Hofstad & Vedeld, Citation2021; Kronsell & Mukhtar-Landgren, Citation2018). Here, the two functions of legitimacies can be regarded to have operated in separate periods of the emerging innovation, but as shown the policy also had a critical pre-history that involved co-creation with regulatory functions, for example, existing legislations, parking regulations and fining practice. The City Council decision was an outcome of the co-creation from shared interests, as pointed out in the literature of collaborative innovation (Sørensen & Torfing, Citation2011; Torfing et al., Citation2016).

The politicians chose a clever design of the governmental goal, given that it was the fining practice of the Traffic Agency that triggered the policy process. This fining practice backfired on them, so to speak. The situation was difficult, to begin with, as public managers and employees were reluctant to embrace the new task, but the agency was pushed by its own standards to deliver on governmental goals and budgets. This certainly contrasts from the horizontal logic pointed at in the ideal-typical role of municipalities as partners (Kronsell & Mukhtar-Landgren, Citation2018; Nieminen et al., Citation2021). Yet, users of EVs were represented by NEF and citizens with green interests by environmental organisations.

Based on this, one may argue that, experimental governance can nurture policy change in a hierarchical way by allocating funding and providing spaces for experimentation. Yet, experimental governance may also promote change in more sophisticated ways, for example by specifying critical attributes in governmental goals as a way to overcome existing structural challenges and transforming institutional routines. In this case, the governmental goal promoted, destabilised, transformed and co-created policy change at various times, but also over time. As shown, these various governmental roles created pressure for change through various pieces of governmental policies. For example, the City Council decision involved various policy elements at the democratic level, for example, governmental goals, policy proposals and budgetary items. It also included elements that operated at the administrative level, for example, assignment procedures, organisational goals and institutional routines. Each of these various pieces created underlying dynamics, as separate and temporal elements. As shown here, these temporal elements also interacted and co-evolved over time.

The many temporal elements created pressure for change from various sources, but they were also intertwined in the one City Council decision. This governmental policy acted at various levels, and over time, and created several underlying dynamics. Moreover, the shifting roles of promoting, destabilising, transforming and co-creating demonstrate how the dynamics also acted over time, which resulted in combined effects that contributed to strengthen the policy goal. Moreover, the policy co-evolved with critical elements in the given context. The urban experiment of charging stations emerged in a small market for EVs, which allowed for policy learning. Thus, being an experiment, a successful outcome for the governmental goal was not given. Moreover, as we have witnessed in recent years, the huge development of the EV market in Norway has resulted in new policy dilemmas, which are currently being debated – for example, concerning the advantageous of the legislation for EVs.

In order to understand the critical co-evolutionary dynamic of experimental governance we need more in-depth studies of the role of governmental policies in their distinct context. More studies need to address how policies evolve with events in the overall society. Moreover, detailed studies are needed to examine how policies act out at various levels, and over time, so as to uncover the fundamental forces for how governmental policy can foster innovation, challenge existing structures and transform policies into new practices, demonstrating the critical layered arrangement of experimental governance and policy change. Such studies can contribute to a more accurate understanding of the complexity of governmental policy, in how it operates as a temporal element at a distinct point in time, but also across different levels and over time creating critical co-evolving dynamics that strengthen the policy goal.

This study also demonstrates the need for more studies of the importance of experimental governance in urban experiments. As stated above, the development of the EV market in Norway has resulted in new dilemmas for the legitimacy of the EV policy. Indeed, these debates do not refer to emerging markets, or any evaluation of the intended policy goals of the legislations for EVs, that could have showed the successful outcome of the policies, in the growth in EVs as a sustainable mobility solution in cities. The lack of contextual and historical approaches in the public debate highlights the need for more attention in academic research on the importance of temporal elements of governmental policy and of the co-evolutionary dynamics of such elements of governmental policies over time. Moreover, there is a need for more studies of experimental governance, in contributing to a more solid knowledge of the many underlying dynamics of how local governance create green and smart cities.

Acknowledgements

A preliminary outline of this paper was presented at the IST Conference at Carleton University in June 2019, at the special track for mobility futures. The author is grateful for the discussions in the session, and for the great comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rannveig Røste

Rannveig Røste is associate professor in the cross-disciplinary field of innovation, organisational behaviour and public administration at Østfold University College. Røste has a Ph.D. in Innovation and Entrepreneurship from the Norwegian Business School and a cand. polit. in political science from the University of Oslo. Her main research interest is innovation processes in complex systems, with a special focus on sustainability transitions in public services.

Notes

1 City Government of Oslo 2007: Budget for Oslo 2008.

2 Private Proposal by Liberal Left Party, City Council, August 2007.

3 Private Proposal by Liberal Left Party, City Council, August 2007.

4 SSB 2021: statistic registered EVs in Norway.

5 Annual Reports, Traffic Agency 2004-2010.

6 Annual Report 2006, Traffic Agency.

7 Annual Report 2008, Traffic Agency.

8 Personal interview with public manager in the Traffic Agency, April 2009.

9 Statistics Norway 2016.

10 Personal interviews with the team of public managers in the Traffic Agency and the Norwegian EV Association, 2011.

11 Personal interview Traffic Agency 2009 and 2011.

12 Traffic Agency 2008: ‘Coupling houses with power supplies for EVs’. Tender document.

13 Traffic Agency 2009: ‘Technical equipment for charging of EVs’. Tender document.

14 Traffic Agency 2012: ‘Charging stations for EVs in the City of Oslo’. Tender document.

References

- Ansell, C., & Torfing, J. (2014). Collaboration and design: New tools for public innovation. In C. Ansell & J. Torfing (Eds.), Public innovation through collaboration and design (pp. 1–19). Routledge.

- Avelino, F., Grin, J., Pel, B., & Jhagroe, S. (2016). The politics of sustainability transitions. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 18(5), 557–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2016.1216782

- Bulkeley, H., & Betsill, M. (2005). Rethinking sustainable cities: Multilevel governance and the ‘urban’ politics of climate change. Environmental Politics, 14(1), 42–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/0964401042000310178

- Crosby, B. C., ‘t Hart, P., & Torfing, J. (2017). Public value creation through collaborative innovation. Public Management Review, 19(5), 655–669. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2016.1192165

- Fuenfschilling, L., Frantzeskaki, N., & Coenen, L. (2019). Urban experimentation & sustainability transitions. European Planning Studies, 27(2), 219–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1532977

- Geels, F. W. (2004). From sectoral systems of innovation to socio-technical systems: Insights about dynamics and change from sociology and institutional theory. Research Policy, 33(6-7), 897–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2004.01.015

- Grin, J. (2020). Doing’ system innovations from within the heart of the regime. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 22(5), 682–694. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1776099

- Hartley, J., Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J. (2013). Collaborative innovation: A viable alternative to market competition and organizational entrepreneurship. Public Administration Review, 73(6), 821–830. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12136

- Head, B. W., & Alford, J. (2015). Wicked problems: Implications for public policy and management. Administration & Society, 47(6), 711–739. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399713481601

- Hodson, M., Geels, F. W., & McMeekin, A. (2017). Reconfiguring urban sustainability transitions, analysing multiplicity. Sustainability, 9(2), 299. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9020299

- Hofstad, H., & Vedeld, T. (2021). Exploring city climate leadership in theory and practice: Responding to the polycentric challenge. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 23(4), 496–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2021.1883425

- Hoogma, R., K, R., Schot, J., & Truffer, B. (2002). Experimenting for sustainable transport: The approach of strategic niche management. Spoon Press.

- Huitema, D., Jordan, A., Munaretto, S., & Hildén, M. (2018). Policy experimentation: Core concepts, political dynamics, governance and impacts. Policy Sciences, 51(2), 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-018-9321-9

- Kivimaa, P., Hildén, M., Huitema, D., Jordan, A., & Newig, J. (2017). Experiments in climate governance – A systematic review of research on energy and built environment transitions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 169, 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.01.027

- Köhler, J., Geels, F. W., Kern, F., Markard, J., Onsongo, E., Wieczorek, A., Alkemade, F., Avelino, F., Bergek, A., Boons, F., Fünfschilling, L., Hess, D., Holtz, G., Hyysalo, S., Jenkins, K., Kivimaa, P., Martiskainen, M., McMeekin, A., Mühlemeier, M. S., … Wells, P. (2019). An agenda for sustainability transitions research: State of the art and future directions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 31, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.01.004

- Kronsell, A., & Mukhtar-Landgren, D. (2018). Experimental governance: The role of municipalities in urban living labs. European Planning Studies, 26(5), 988–1007. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1435631

- Langley, A., Smallman, C., Tsoukas, H., & Ven, A. H. V. d. (2013). Process studies of change in Organization and management: Unveiling temporality, activity, and flow. Academy of Management Journal, 56(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.4001

- March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. (1983). The New institutionalism: Organizational factors in political life. American Political Science Review, 78(3), 734–749. https://doi.org/10.2307/1961840

- Markard, J., Raven, R., & Truffer, B. (2012). Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects. Research Policy, 41(6), 955–967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2012.02.013

- McFadgen, B., & Huitema, D. (2018). Experimentation at the interface of science and policy: A multi-case analysis of how policy experiments influence political decision-makers. Policy Sciences, 51(2), 161–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-017-9276-2

- Meadowcroft, J. (2011). Engaging with the politics of sustainability transitions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 1(1), 70–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2011.02.003

- Moore, M., & Hartley, J. (2008). Innovations in governance. Public Management Review, 10(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030701763161

- Mukhtar-Landgren, D., Kronsell, A., Voytenko Palgan, Y., & von Wirth, T. (2019). Municipalities as enablers in urban experimentation. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 21(6), 718–733. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2019.1672525

- Nieminen, J., Salomaa, A., & Juhola, S. (2021). Governing urban sustainability transitions: Urban planning regime and modes of governance. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 64(4), 559–580. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2020.1776690

- Ostrom, E. (2010). Polycentric systems for coping with collective action and global environmental change. Global Environmental Change, 20(4), 550–557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.07.004

- Peters, B. G., & Tarpey, M. (2019). Are wicked problems really so wicked? Perceptions of policy problems. Policy and Society, 38(2), 218–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2019.1626595

- Pettigrew, A. M. (1990). Longitudinal field research on change: Theory and practice. Organization Science, 1(3), 267–292. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1.3.267

- Raven, R., Kern, F., Verhees, B., & Smith, A. (2016). Niche construction and empowerment through socio-political work. A meta-analysis of six low-carbon technology cases. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 18, 164–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2015.02.002

- Sengers, F., Wieczorek, A. J., & Raven, R. (2019). Experimenting for sustainability transitions: A systematic literature review. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 145, 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.08.031

- Smith, A., & Raven, R. (2012). What is protective space? Reconsidering niches in transitions to sustainability. Research Policy, 41(6), 1025–1036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.12.012

- Smith, A., Stirling, A., & Berkhout, F. (2005). The governance of sustainable socio-technical transitions. Research Policy, 34(10), 1491–1510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2005.07.005

- Sørensen, E., & Torfing, J. (2011). Enhancing collaborative innovation in the public sector. Administration & Society, 43(8), 842–868. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399711418768

- Termeer, C. J. A. M., & Dewulf, A. (2019). A small wins framework to overcome the evaluation paradox of governing wicked problems. Policy and Society, 38(2), 298–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2018.1497933

- Torfing, J., Sørensen, E., & Røiseland, A. (2016). Transforming the public Sector into an arena for co-creation: Barriers, drivers, benefits, and ways forward. Administration & Society, 51(5), 795–825. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399716680057

- von Wirth, T., Fuenfschilling, L., Frantzeskaki, N., & Coenen, L. (2019). Impacts of urban living labs on sustainability transitions: Mechanisms and strategies for systemic change through experimentation. European Planning Studies, 27(2), 229–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1504895

- Voß, J.-P., & Simons, A. (2018). A novel understanding of experimentation in governance: Co-producing innovations between “lab” and “field”. Policy Sciences, 51(2), 213–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-018-9313-9

- Wolfram, M., Frantzeskaki, N., & Maschmeyer, S. (2016). Cities, systems and sustainability: Status and perspectives of research on urban transformations. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 22, 18–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2017.01.014