ABSTRACT

The use of strategic visions based on concepts like climate-neutrality, net-zero emissions and energy efficiency is important to align action and build momentum. The agency of transition actors requires clear definitions and explanations of visions, enabling operationalization for action, monitoring and measuring of results. This paper develops a maturity scale for climate-related strategic visions among local governments. Further, the maturity of Swedish municipalities’ climate-related strategic visions is reviewed. The results show that out of Sweden’s 290 municipalities, 256 shows overall low maturity in their strategic visions, not supporting their local, regional and national system actors sufficiently. Furthermore, results from workshops indicate that the roles, mandate and process for working with municipal strategic visions are not clear. There is an ambiguity around visions that is hindering aligned action and progress.

Introduction

‘Striving to be the first climate-neutral continent’ is the first message that greets visitors on the webpage that introduces the European Union’s (EU) ‘Green Deal’ (European Commission, Citation2022b). EU and its member states have formally ratified the Paris agreement from 2015 and the EU countries are committed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% until 2030. Climate-neutrality is a concept that has been defined by the IPCC as a ‘concept of a state in which human activities result in no net effect on the climate system’ (IPCC, Citation2018). In general, to achieve climate-neutrality all annual emissions need to be balanced by removing the same amount of carbon dioxide equivalents, i.e. not only carbon dioxide, from the atmosphere. The international support for the Paris Climate agreement indicates that striving to achieve a climate-neutral state is a vision worthy of pursuit although it entails a societal transition.

Transition researchers have previously emphasized the importance of using visions to pursuit sustainable development (Loorbach, Citation2010). The concept of sustainable transitions is drawing attention from several disciplines aiming to support policy and decision makers for an accelerated transition towards a new state of sustainability (Köhler et al., Citation2019). One key feature for initiating and accelerating a transition is to ‘zoom in and out’, so that global problems can find local solutions (Köhler et al., Citation2021). Strategic visions and mission-oriented innovation systems are developed in the sub-field of transition management (Hekkert et al., Citation2020; Loorbach, Citation2010; Loorbach & Rotmans, Citation2010), and be used as powerful tools for local transition management. The notion of the EU striving to be the first climate-neutral continent is an example of high-level visions to be brought down to a local level for guiding a sustainable transition.

On a national-level, Sweden as a member state of EU has a long-term vision to have net-zero emissions of greenhouse gases by 2045. To reach the national climate goals, several Swedish regions and cities have set their own goals, presented in local environmental/sustainability action plans and/or policies. Municipalities and regions in Sweden are authorities that have direct influence and control over city- and regional development. Regions, cities and municipalities are using a variety of different terms to describe and communicate visions, goals and/or actions to decrease regional and local emissions of greenhouse gases. Municipalities and local actors play a key role to realize the sustainable development visions and goals set by the government (Fenton & Gustafsson, Citation2017; Graute, Citation2016; Moloney et al., Citation2018).

The problem statement here is that when Swedish municipalities communicate future strategic visions for cities and/or city districts in terms of climate-neutrality, net-zero emissions, low energy, passivity, net-zero energy or even energy positivity, the clear-cut definition of the concept is seldom explicit. The impression is that these terms often contain a vagueness and room for interpretation, i.e. ‘interpretive flexibility’ (Smith et al., Citation2005). This impression is also supported by the conclusions from (de Jong et al., Citation2015) where conceptual differences are studied regarding descriptions of ideas for improved environmental, social and economic conditions for cities. This inherent vagueness and large variety in concepts have also been shown to impose difficulties in designing efficient municipal actions in order to achieve set goals, as well as the possibility to follow-up on measures taken. The latter is described in Keskitalo and Liljenfeldt (Citation2012), where a number of Swedish municipalities and their work on sustainable development is studied. The picture of inefficiencies in local and regional actions for sustainable development is further strengthened by Damsø et al. (Citation2017), stating that executions of local action plans seldom are implemented fully.

Based on these previous results from various actors engaged in local governance, an idea of maturity levels among the municipalities is introduced with a focus on differences in the use and communication of climate-related strategic visions. How this maturity scale is constructed is described in the methodology section, following the ideas from transition- and change management presented in the section for theoretical framework.

Two Swedish network initiatives are introduced; Klimatkommunerna (Climate municipalities) and Ekokommunerna (Eco municipalities). These initiatives promote municipal collaboration and networking activities in order to increase understanding, i.e. maturity, for improved municipal climate action. They are operating with the specific purpose of aligning and increasing the climate-related understanding of strategic visions among Swedish municipalities, which builds an expectation that members of these two networks are more mature than non-members.

This paper was initiated with the aim of investigating the use of climate-related concepts in strategic visions of Swedish municipalities and how the maturity level of such climate-related concepts effect operational activities among the officials at the municipalities. Based on the presumption that the use of climate-related concepts is key for aligning actions in the transition towards the Swedish national goal and EU’s ambition to become the first climate-neutral continent, two initial research questions explored are:

RQ1 How mature is Swedish municipalities in their work with climate-related strategic visions?

RQ2 Are the strategic visions from members of networking organizations, here the Climate municipalities and the Eco municipalities, more mature than other municipalities strategies?

RQ3 How is the maturity of strategic visions for a local policy maker, here a Swedish municipality, affecting the work of operational actors in the system?

Theoretical framework

Studies in sustainable transitions are focused on large-scale societal changes needed to achieve sustainable development (Loorbach et al., Citation2017; Markard et al., Citation2012). While sustainable development and sustainability often is used interchangeably, the two concepts can be viewed as a path and destination. Sustainable transitions are concerned with how to bring about change on multiple levels of societal structures, see overview of multi-level perspective in Geels (Citation2002). In these efforts it is mainly concerned with the path, the ‘how’ of transitions, where the ‘what’, i.e. the destination is seldom specified. One suggestion is that the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) should be combined to form the framework for future research on sustainable transition studies (Singh, Citation2020). In this paper, the sustainability dimension in focus is the environment and more specifically climate change – which is SDG number 13 (UN General Assembly, Citation2015).

Transition management

The governance approach of transition management (TM) is focused on managing socio-technical systems transition and transformation (Kemp & Loorbach, Citation2006; Loorbach, Citation2010). The activities of TM are commonly divided into four types: strategic, tactical, operational and reflexive. ‘Guiding visions’ are used as an instrumental tool in TM for governance at the strategic, tactical and operational level:

An important driver for innovation and experimentation at all levels is the belief actors have in alternative futures and fundamental values that they strive to realize. Visioning … are therefore important tools in transition governance to facilitate and empower actors and networks, so that they can more strategically work on transitions, explore more radical innovation trajectories, and formulate alternative goals. (Loorbach et al., Citation2017, p. 614)

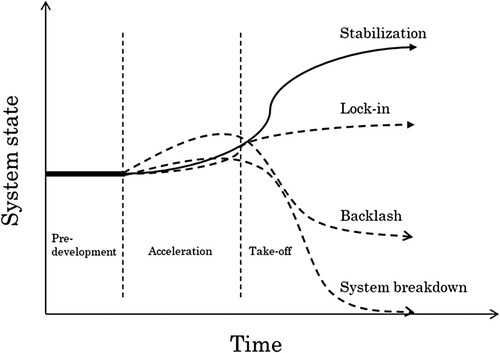

The larger context in which strategic visions are framed is called transition pathways (Grin et al., Citation2010; Loorbach et al., Citation2017), see . A transition pathway is the imagined shift in system state (system performance), from one level to another. The pathway visualizes the intended transition. The first of the transition pathways conceptualizes the desired transition, where a system over a period of time changes toward a higher state and stabilizes in a new equilibrium state (named stabilization in ). A transition that seems promising but later reverts back into a lower system state is called a backlash, while a minor improvement that is unable to reach a higher system state is called a lock-in. In the case where a transition cannot reach a higher system state and only decreases is called a system breakdown. All transition pathways illustrated in are unwanted except the stable transition towards a higher system level, interpreted as a defined improvement in system performance. In this study, the stabilization pathway relates to a state of climate neutrality. That would be moving from a system state that has an output which affects the climate system in such a way that it deviates from its normal conditions.

Figure 1. Illustrating four generic transition pathways, stabilization, lock-in, backlash and system breakdown where each pathway finds a new system state over a three time periods characterized by different rates of change. Source: Grin et al. (Citation2010).

The role of strategic visions in transition management

Looking beyond TM, local governance related to sustainability issues has been a topic of research for more than 20 years (Eckerberg, Citation2001; Khakee, Citation2002). Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, several case studies in Sweden and Denmark have provided insights into local governance and implementation of visions for sustainable development. Keskitalo and Liljenfeldt (Citation2012) provide insights from seven municipalities on working with sustainability, Isaksson and Hagbert (Citation2020) explore institutional capacity in two Swedish municipalities, Damsø et al. (Citation2017) assesses the implementation plan for local climate transition towards a carbon-neutral Copenhagen, Fenton and Gustafsson (Citation2017) study the specific relation between national and local governance for sustainability in municipalities, and Gustafsson and Mignon (Citation2020) explore the role of municipalities as intermediaries for the design and implementation of local climate visions. In a Swedish case study from 2003, Rowe and Fudge explore the relationship between national strategies for sustainable development and local implementation (Rowe & Fudge, Citation2003). Findings from the above-mentioned studies suggest that the challenges of articulating explicitly what the long-term planning is hindering progress. While the ‘guiding visions’ are suggested as one of the main tools for strategic activities in TM, its importance should not be overemphasized:

A vision is useful in giving direction, but the importance of the vision itself should not be overstated as there are often many different visions competing in a context where all sorts of uncertainties and seemingly random events might take over. The role of visions in transition governance is thus mainly to motivate, coordinate, and empower actions in the short term and medium term. (Loorbach et al., Citation2017, p. 614)

Considering the idea of climate-neutrality and net-zero greenhouse gases as a normative strategic vision for Sweden, the change between the current system and the vision, i.e. the transition, requires actors taking action. A conceptualization of sustainable business models and the link to strategic, tactical and operational activities of TM is described in Hernández-Chea et al. (Citation2021). The core idea here is that the strategic vision can be used as a tool for guiding action among these distinguished actors that enables a successful transition (Loorbach et al., Citation2017). The use of visions as a tool to accelerate the transition towards a net-zero emission society is hereby related to the operations at municipal level in two ways. First, as a way for municipalities to align their operations to manage such a transition process. Second, as a way for municipalities to increase the agency of other actors in the local system, with operations directly related to strategic visions. Here, agency is defined as the combination of willingness, access to resources, strategies and skills (Avelino, Citation2011), which all could be influenced by the municipal actors. Focus is on the climate policies which are understood as strategic visions.

Functions and maturity of strategic visions

The idea of how strategic vision can be used to coordinate action between mutually dependent actors described above and in Kemp and Rotmans (Citation2004) has been criticized for too optimistically portraying the process of vision formation as a per se constructive process (Grin, Citation2000). While there are interesting empirical research on this formation process, e.g. Späth and Rohracher (Citation2010), this paper focuses on the maturity of the presented strategic visions and the effect on local actors in their operational activities. For such purposes, a conceptualization of the function of visions suggests five functions that a vision could support: visions (1) map a ‘possibility space’, (2) function as a heuristic, (3) provide a stable frame for target setting and monitoring progress, (4) serve as a metaphor for building actor networks and (5) offer a narrative for focusing capital and other resources (Smith et al., Citation2005). Here the functions (2) and (3) are described in terms of tools supporting technical problem-solving and innovation where (3) specifically could be ‘serving as a common reference point for actors collaborating on its realization’ (Smith et al., Citation2005, p. 1506). As a counterweight to the desired technical specificity of visions, a degree of ‘interpretive flexibility’ of visions is stressed for the wider acceptance of the vision in its functions (1), (4) and (5) (Smith et al., Citation2005). As the storylines codifying the visions are reshaped and several processes of revisioning may occur as the transition unfolds, initial visions may be relatively vague and incoherent. This provides the interpretative flexibility among actors which will support initial formation of coalitions picking up the vision (Smith et al., Citation2005). However, as the coalition is to pursue the vision too much flexibility can cause interpretive instability and harm the robustness of the vision (Smith et al., Citation2005).

From an organizational perspective, a five-step sensemaking process for leading for sustainable development has been suggested to include Understanding, Defining, Measuring, Communicating and Leading sustainable development (Isaksson & Hallencreutz, Citation2008). For the municipality to be a leading actor for sustainable development, in this case, a leader for decarbonization and climate-neutrality of their jurisdiction, they should communicate progress and targets based on their measurements. Related to function (3) ‘provide a stable frame for target setting and monitoring progress’, these measurements should reflect the definitions of climate goals and visions that result from the municipality’s understanding of the transition needed (Isaksson & Hallencreutz, Citation2008). In deciding what is a ‘well-communicated strategic vision’, three key parts are identified:

an understanding (manifested in an explanation)

a definition, and

measurements for monitoring.

Combining the five functions with the five-step sensemaking logic, a maturity scale for strategic visions is derived. It suggests that a communicated strategic vision can be scaled from insufficient to sufficient. The implied relation between the maturity level of a vision is that the higher maturity level, the clearer direction for sub-system activities. This sets the conditions for an accelerated transition towards the goal and the vision has a higher robustness, i.e. a high maturity level, in the technical specificity of measurements for monitoring progress. Conversely, a low maturity level indicates a lower robustness but larger interpretative flexibility of the vision. The maturity scale assumes a necessity of alignment of measurements for transition agendas set by strategic visions. Maturity of visions is viewed from the perspective that the initial need for interpretative flexibility is eventually reduced as the coalition is formed. Emphasis is placed on transition progress which requires measurements for monitoring. A mature vision is here seen as a necessary but not sufficient criteria for an accelerated transition, as the tools and activities needed to make the vision happen are part of a complex process beyond the strategic vision. Note that this study only considers the maturity scale regarding the vision of climate-neutrality and net-zero emissions, the realization of the action plans/policies is not considered.

Defining climate neutrality and net-zero emissions

Climate-neutrality is a concept describing a state of society where the outcome from human activities results in no net effects on the climate system. The concept could be used as a descriptive state but also as a normative idea of how our societal system should work.

IPCC defines climate-neutrality as:

a concept of a state in which human activities result in no net effect on the climate system. Achieving such a state would require balancing of residual emissions with emission (carbon dioxide) removal as well as accounting for regional or local biogeophysical effects of human activities that, for example, affect surface albedo or local climate. (IPCC, Citation2018)

IPCC has also defined Net zero CO2 emissions as: ‘Net zero carbon dioxide emissions are achieved when anthropogenic CO2 emissions are balanced globally by anthropogenic CO2 removals over a specified period’ (IPCC, Citation2018).

The EU declares at their official homepage that: ‘The European Green Deal will ensure no net emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050’ and follows with the ambition of: ‘EU Striving to be the first climate-neutral continent’ (European Commission, Citation2022b). Another example where both the terms climate-neutral and net-emissions are mentioned in the same context is at the official homepage describing the climate strategies and targets: ‘The EU aims to be climate-neutral by 2050 – an economy with net-zero greenhouse gas emissions’ (European Commission, Citation2022a).

It is apparent that the concepts climate-neutrality and net-zero emissions are mixed without any distinction in the European Green Deal while IPCC makes a clear distinction. IPCC’s definition takes a larger scope of human activities including biogeophysical effects on top of greenhouse gas emissions, an important difference for the operationalization of the concept. The Swedish government has set a goal to have net-zero emissions of greenhouse gases by 2045 (Ett Klimatpolitiskt Ramverk För Sverige, Citation2017; IPCC, Citation2018). In the national vision regarding emissions of greenhouse gases and climate change, the concept of climate-neutrality is left unmentioned.

Although precise definitions and taxonomy-like use of climate-related concepts like climate-neutrality and net-zero emissions exist, the short review of IPCC, EU, and Swedish government indicates that the concepts are not always concurrent. For the rest of the paper, we focus on how Swedish municipalities are using climate-related concepts.

Methodology

This descriptive study is based on a review of 290 local municipalities environmental/sustainability action plans/policies. Data was collected through desk research and complemented by transcripts from a workshop with officials from the Swedish municipalities of Gävle, Uppsala and Knivsta. The descriptive study is divided into two parts where the first part rates the local action plans/policies based on an ordinal maturity scale. The second part explores how the visions are used and effect the actors of local governance in a workshop forum.

Measuring maturity of climate policies

The resulting maturity scale for the first part of the study was constructed to categorize the local municipalities communication of their ambitions and targets. The policies were rated based on an ordinal maturity scale from 0 to 3 where the intervals were constructed based on the communication of a strategic vision with the components definition, explanation and measures, see . It is important to note that these grades are not the results from a thorough analysis of the actual sustainability ambitions or efforts made by these municipalities, but rather an analysis of the formal and publicly available strategies communicated on websites.

Table 1. Maturity scale for strategic visions relating climate-policies, with four levels from level 0 to 3.

The suggested maturity scale presented in assumes the ability to distinguish and assess the key parts, definition, explanation and measurability of the strategic vision. Using the written information from official websites and policy documents, we assume that the organization is transparent, i.e. communicating what they are doing and also doing what they are communicating. While both these assumptions can be questioned and should be scrutinized, we argue that language is a tool for communication and explicit definitions and stringent use of concepts must be accepted as truthful and reflections of the reality of the policy-making organization. When an organization has a vision statement with clear use of concepts that leads to something that is operationalized and where progress can be monitored, we accept that at face value. The other way around, when a policy-making organization has a vision statement without any definitions of the used concepts, the lack of clarity is instead understood as ambiguity (intended or unintended). In attempts to provide rigidness in terms of replicability of results, the maturity assessment criteria and levels are kept as simple and explicit as possible.

The assessment of each municipality’s environmental policy followed an iterative process where the keywords used for searching for public content on each municipalities webpage were revised in three steps. Initial searches were made for: klimatplan, klimatmål, miljöplan, miljömål, miljöbokslut, klimatbokslut. If no results were obtained, as the keywords miljö, klimat and hållbarhet were used.Footnote1 If still no results were obtained, a final search was conducted for the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The screening was conducted during December 2021 and January 2022. An additional search was conducted among the municipalities reaching level 1, 2 and 3 in July 2022 screening for the use of the term climate-neutrality among the municipalities environmental action plan/policy.

After rating all 290 municipalities the two networks Klimatkommunerna (Climate municipalities) and Ekokommunerna (Eco municipalities) were reviewed in terms of municipality membership. Klimatkommunerna has 40 members and Ekokommunerna has 111 members at the time of the study. Out of these, 10 municipalities were members in both networks, which means that 141 out of the totally 290 Swedish municipalities are members of at least one of the two networks. The two networks were chosen based on their explicit goal to support municipalities in their climate-related policy work and both organizations being contributors to the proposition resulting in the new climate policy framework passed in 2017 (Regeringskansliet, Citationn.d.-a). The distribution of maturity ratings was cross-checked against the overall distribution to assess the effectiveness of the two networks.

Workshops on climate-neutral cities

In 2016, the Swedish government presented a report where nine areas in six municipalities were identified as suitable areas for large-scale urban transformation projects with an aim to build residential areas. Three out of these six municipalities; Gävle, Knivsta and Uppsala, signed contracts with the government. The contract states that the municipalities were to build climate-neutral city districts, while the government finances regional infrastructural development. This contract is used as the criteria for sampling municipalities for this study, in line with the purposeful sampling method ‘criterion sampling’ as described in Patton (Citation2002, p. 200). As part of a project financed by the Swedish Energy Agency with the aim to analyze different ways of managing a climate-neutral energy use in those areas, two workshops were held with officials representing the three municipalities. Since the municipalities had signed a contract where the term climate neutral is used, the maturity level of the strategic visions was assumed to be higher and they could serve as examples of forerunners in Sweden.

During the workshops, the participants were asked to reflect on the term climate-neutrality and what it meant them and their respective organization. The discussions were then widened to climate policies and the role and responsibilities for the municipalities. The main theme of the first workshop was the maturity of the strategic visions for local sustainability transition but the discussions continued in the second workshop. The workshops were held online on March 24th and April 29th in 2021. Both workshops lasted for about three hours. The entire workshops were recorded and later transcribed. Resulting data material was considered sufficient for the purpose of exploring RQ3 among the three sampled municipalities.

In the workshops, the municipalities of Gävle and Knivsta were represented by three officials per municipality, and Uppsala municipality by two officials. All officials participating are involved with climate-neutral city districts in their municipalities but also the more general local climate policies. The data analysis was guided by the inductive content analysis (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008) which is suitable when theory-informed categorization is not available prior to data analysis (Cho & Lee, Citation2014). The unit of analysis was decided to be the individual officials and their expressed perception regarding the use of climate neutrality and related terms was decided as the selection criteria for reducing the transcribed data from the workshops. Following the process of open coding, creating categories and abstraction (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008), the workshop data was initially organized as paragraphs of related information. These paragraphs or sentences were then categorized and ordered into higher order abstractions. These are definition of climate neutrality, relations between politics and municipal officials, and finally, conditions for municipal planning, implementing and assessing climate measures. Identified key content was then translated from Swedish to English and constructed into a descriptive summary of the officials perceived use of strategic visions among municipalities when discussing climate-neutral neighborhoods and cities.

Climate policy in Sweden

Introducing municipal governance in Sweden

Swedish state and regional governance is split into three levels; national, regional and local levels (Regeringskansliet, Citationn.d.-c). There are 21 regions and 290 local municipalities. Responsibility for the national government that regulates what regions and municipalities must do/fulfill. The regions are responsible for tasks that are common to larger geographical areas and that often require large financial resources. Local municipalities are exercising self-governance, based on the democratic principles of distributed power. Each local municipality is organized through several boards and administrations that are obliged by the law to cater their community with a set of societal services. Climate governance in regional and local municipalities is one of the responsibilities delegated to the local governing organizations. Municipalities are expected to carry through decisions made by the government but the self-government in municipalities makes the hierarchical governance somehow diffuse (Montin, Citation2007). Entailing that active engagement for certain legislations from national level is optional for local municipalities due to lack of resources or that the laws and regulations are in conflict with other prioritized interests (Montin, Citation2007).

From a national perspective, a major input to the municipalities climate policies was introduced in 2017. As part of following the Paris Agreement from COP21 (2015), a climate policy framework was adopted. The framework comprises three different parts: (1) a climate act, (2) long-term climate targets (zero net greenhouse gas emissions by 2045) with milestone targets for 2020, 2030 and 2040, (3) a Climate Policy Council with a mission to control the pursued politic and results (Regeringskansliet, Citationn.d.-b). In tandem with the climate policy framework, a climate act was adopted by the government where the purpose of the climate work is clarified but the act also regulates how this work shall be carried out and monitored (Regeringskansliet, Citationn.d.-a). The new climate act laid out the fundamental structure for how the Swedish government should work and consider climate-related policies. For the milestone targets, the emission rates from 1990 are used as a baseline. To reach net-zero emissions of greenhouse gases in Swedish territory the definition states that the emission levels need to be at least 85% lower territorial emissions than the emission rates of 1990. Further, the remaining emissions are compensated by supplementary measures, such as increased uptake of carbon dioxide by forests or investments in various climate projects abroad. The climate policy framework includes a planning and monitoring scheme for Swedish actors with yearly climate reports and climate policy action plans. The proposition motivating the new policy framework emphasizes that ‘it is now central for all affected parts of the policy, nations, municipalities, business and civil society to take immediate actions to align with the Paris pledge’ (Ett Klimatpolitiskt Ramverk För Sverige, Citation2017, p. 27).

Municipal policy maturity in Sweden

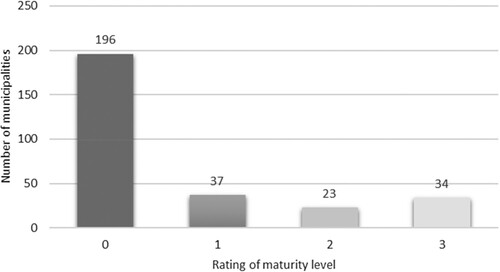

RQ1 is answered by the distribution illustrated in , where an overall low maturity among Swedish municipalities is found. 196 (68%) of Swedish municipalities does not communicate any strategic vision related to climate-neutrality and net-zero society. Only 34 (12%) of all 290 Swedish municipalities provide a mature, i.e. sufficient, communication around their climate-related strategic visions that enables system actors to use and increase their agency for a transition towards the strategic vision. Twenty-three municipalities meet the criteria for level 2, 37 meet the criteria for level 1.

Among the 94 municipalities with a rating of one or higher, 27 municipalities use the term climate-neutral in their action plans/policies.

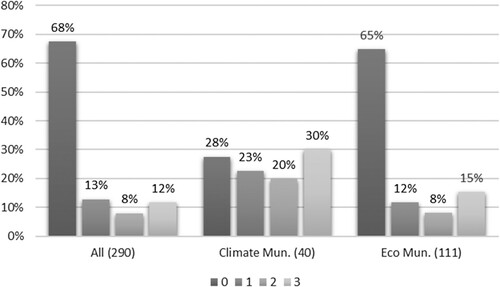

In , the distribution of ratings for both the network of ‘Climate municipalities’ and ‘Eco municipalities’ are compared to the results of all municipalities. RQ2 is answered by the cross-check against members of the Climate municipalities and Eco municipalities which indicate inconsistent results. Where the distribution among the Eco municipalities is similar to the national distribution, the distribution for the Climate municipalities shows a significant lower number of level 0 and a higher number of level 3 among their members.

Figure 3. Distribution of maturity ratings for three groups of municipalities, all, Climate municipalities and Eco municipalities.

For the municipalities participating in the workshop, the level of maturity was assessed to a level 2 for Gävle, level 1 for Uppsala and level zero for Knivsta. Gävle has done substantial work with their local environmental policy but also with an action plan with local targets. The reason for not reaching the highest maturity is that their goals include consumption-based emissions and not territory-based emissions which are more common. Also, the Gävle action plan lacks a definition on how the consumption-based emissions should be calculated and monitored. Therefore, the maturity is assessed to level 2. The municipality of Uppsala has set ambitious environmental targets that the municipality should be fossil free in 2030 and climate-positive in 2050. The maturity level is assessed to one since there is no explanation how climate-positive is defined, for example, if the system boarders for the calculations are territory-based. Knivsta receives a zero in maturity since there was only an out-of-date environmental plan and plans/policies for local areas within the municipality, not for the whole municipality as a geographic area.

The use of strategic visions in action

This section presents the main findings from the transcribed workshop discussions based on three themes, definition of climate neutrality, relations between politics and municipal officials, and conditions for municipal planning, implementing and assessing climate measures.

Climate-neutrality and what is included

The workshop discussions show clear differences in how explicit the municipalities are regarding their definitions and explanations of what is included in their visions. Gävle, for instance, is clear on the fact that climate-neutrality will include emissions from all activities in the region as well as indirect emissions from all consumption within the region. This goal is set for 2035 and motivated by the municipality’s ambition to have an overall perspective on the transition management strategy for sustainability. Knivsta is, as Gävle, reasonably clear on what their goals are. However, the scope of Knivstas’ goals is more sector specific and limited to fossil-free transport and climate-neutral energy use in buildings. This is a significantly lower ambition for emission reductions than what Gävle communicates. One of the Knivsta representatives mentions that ‘soft’ values are what is most important, and that if people experience that their situation is good and safe, they are more likely to engage in environmental issues and participate in the transition. This indicates that Knivsta might have ambitions that have a wider scope and a more indirect priority, rather than focusing solely and directly on emissions of CO2 and climate change. Knivsta representatives also raise the issue of responsibility for indirect emissions caused by international trade.

During the workshop, Uppsala claims to have a very ambitious goal, namely climate-positivity. The Uppsala representatives do not specify what is meant by ‘positivity’ and also not what sectors or geographical parts of the municipality that this concept includes.

Regarding what climate-positivity actually is, I am not there with the definition yet, so to speak. And I do not really think anyone else within the organisation is either. (Official at Uppsala municipality)

Politicians vs. officials

Officials from all three municipalities agree that the relationship between themselves and their governing politicians is crucial for defining strategies and climate goals. In Knivsta and Gävle, officials say that governing politicians often set goals for increased sustainability that have not been established well enough within the organization. These officials experience that politicians have high, and sometimes unclear, ambitions. Thereafter it is up to the officials to figure out how this is supposed to be done, and that this is a difficult and complex task.

Also, the officials from Gävle experience that political goals can change drastically and suddenly, sometimes due to changed policy priorities. This is further raised by Uppsala in the sense that, since the political horizon is generally four years, it is problematic to define goals suitable for transition strategies for decades to come. Part of the explanation for this is that politicians focus on re-elections and that this influence the goals and visions that are set. The officials taking part in the workshop discussion claim to see a clear connection between the lack of collaboration with the politicians and the vagueness in their sustainability transition strategies.

Climate management tools and practice

An issue raised throughout the workshop discussions is the difficulty associated with measuring carbon dioxide emissions. The lack of consensus among municipalities and authorities regarding what to include in emission accounting and how to assess indirect emissions is raised by both Gävle and Knivsta officials as a main issue in defining goals and strategies. Even though there are some tools available, such as ‘koldioxidbudget’ (carbon dioxide budget) and official emission factors from regional administrative boards, there is still a gap between the goals set by municipal politicians and the range of what these tools cover.

Another aspect is the feasibility and fairness of compensating for emissions by investing in a carbon sink somewhere else. This is raised by Uppsala officials as an issue that holds both opportunities as well as risks. This also relates to a discussion on what system-level climate-neutrality or net-zero emissions is to be assessed. An argument from Knivsta officials is that it would be easier to achieve climate-neutrality for residential areas close to public transport systems and more difficult elsewhere. Therefore, tools such as the carbon dioxide budgets need to be refined in order to allow compensations for higher emissions in one part of a system with lower emissions in another part. As voiced by an Uppsala official, there might be a risk that compensations are used as an excuse to avoid more expensive low-emission solutions. And that these compensations are based on conditions that might change in a way that is out of control for the municipal organization. Which eventually could lead to less credited emissions and thus higher overall net-emissions than expected.

As an answer to RQ3, it is clear from the workshop results that municipality officials see ambiguity, i.e. the low maturity, of the municipal sustainability goals and visions as problematic. This ambiguity limits the progress of the municipalities’ work on reducing climate impact. The main problem with immature strategies is the difficulties related to assess and measure emissions and indirectly sustainability. The officials claim that one part of the problem is that politicians, when crafting the sustainability strategies, generally do not include officials. The tension between the inherent nature of politics and the need for long-term perspectives for a transition towards a sustainable society, reduces the agency of municipal officials to follow strategies and achieve climate goals. This in turn leads to insufficient clarity about the actions needed to achieve the strategic vision and how to monitor progress.

Climate-neutrality in Sweden as a case of strategic visions in transition management

Our study serves as an illustrative case of how definitions and conceptualizations from the highest level (IPCC and EU) could flow though the national and regional governance actors and find its way to the local policy maker level and from there increase the agency of the actors in the local system. With a preference for robustness in terms of operationalizability of clearly defined concepts such as climate-neutrality, the maturity results for climate visions in Swedish municipalities are low. The fact that the majority of Swedish municipalities do not define a climate vision indicated a gap in the high-level ambitions of EU- and Swedish national-level visions and the actors with the local mandate to take action. While one of the five functions of visions is described as ‘serving as a metaphor for building networks’ (Smith et al., Citation2005), our results indicate a lack of unity and robustness of climate visions. With references to the theory of institutional capacity, Isaksson and Hagbert (Citation2020) emphasize the use of networks for building relational capacity as a part of successfully implementing a strategic vision. The engagement with both horizontal and vertical networks is also raised in Fenton and Gustafsson (Citation2017) where further research is requested. Our results indicate that being part of a network related to climate policy is not necessarily a condition for increased maturity (based on the similar distribution among the eco municipalities) but that there are networks that seem to have a positive effect on municipal maturity (based on the distribution among the climate municipalities). Here sampling of municipalities could play a part as the network of climate municipalities is smaller in size with 40 municipalities and the eco municipality network has 111 members. Results from Isaksson and Hagbert (Citation2020), as an example, are based on a sample of two municipalities with a more ‘radical’ approach to sustainable development. What potential causes for these divergent results could be and the effect of sampling criteria is not the focus of this paper but could be interesting areas of future research.

Previous studies identify vagueness of the climate-related concepts to be explanations for the low maturity among Swedish municipalities (Damsø et al., Citation2017; de Jong et al., Citation2015; Fenton & Gustafsson, Citation2017; Isaksson & Hagbert, Citation2020; Keskitalo & Liljenfeldt, Citation2012). The ‘interpretative flexibility’ of climate visions is seen as a hinder for operational activities by the municipal officials in this study. The explanations for why the vagueness exist is based on the differences in incentives among the different roles among the municipal actors, where politicians seek ambiguity and operational actors seek robustness. These results show how the focus on different functionalities of the strategic visions leads actors to influence the vision formation with different agendas.

One of the findings raised by the municipality officials in this study was the challenges with crafting relevant indicators to track progress. The complexity around measuring progress for climate-related policies and sustainable development is well-established (Damsø et al., Citation2017; Fenton & Gustafsson, Citation2017; Gustafsson & Mignon, Citation2020; Isaksson & Hagbert, Citation2020; Keskitalo & Liljenfeldt, Citation2012). Existing standards and tools for calculating emissions are not adapted to capture what is included in the goals and strategies for climate-neutrality and/or positivity. This leads to insufficient robustness with regards to the two functions of visions as heuristics for decision support and provide a stable frame for target setting and monitoring progress. The operational officials call for a unified solution to the ambiguity around the measurement procedures related to the progress monitoring of climate-neutrality. Failing to do so could potentially lead to municipalities failing to create and share a sense of urgency for change. Fenton and Gustafsson (Citation2017) suggest, based on a review of previous research, that the municipalities could act as both a coordinator supporting and enabling other actors in implementation of sustainable development goals whilst ensuring its own alignment of actions with the overall sustainability agenda, i.e. strategic vision. Gustafsson and Mignon (Citation2020) emphasize the local context in which the governance is taking place and highlights the managerial abilities of the municipality officials as critical due to the high degrees of autonomy owned by Swedish municipalities. The implication for local governance is therefore to clarify the roles among the internal actors in the municipality and reach a broad agreement on how long-term strategic visions should be used both internally and externally in the local governance. These agreements should include the need to clearly define, explain and provide indicators of progress for the strategic visions.

From a broader perspective, going beyond Sweden, lessons from this study highlight the need for governing actors with agency in systems to be balanced in their formulation of strategic visions. Particular efforts should be made to make sure the strategic vision is clearly defined, explained and provided with the necessary measurements for monitoring progress. These results align and contribute to previous studies (see e.g. Damsø et al., Citation2017; de Jong et al., Citation2015) where the ability to measure and monitor progress is suggested as a key feature of a strategic vision. As innovation policy is suggested to move into a new era of mission-oriented innovation systems our findings reaffirm the new agenda declared by Hekkert et al. (Citation2020). Further, our results highlight the current difficulties local governance are showing in describing a robust climate-related strategic vision which should inform efforts in the future mission-oriented policy work.

Conclusions

A local, regional, national or international policy makers’ maturity of strategic visions can be evaluated based on their definition, explanation and measurability of the stated vision. In the case of Swedish local municipalities, 256 out of the 290 screened municipalities are not supporting their local, regional and national system actors sufficiently in providing a clearly defined, explained and measurable strategic vision. Twenty-seven out of the 94 municipalities that make a reference to a climate-related concept like climate-neutrality or net-zero also includes the climate-related strategic vision in their official climate policy. The cross-check against membership in climate-related supporting networks indicated inconsistent results, where members of the organization Climate municipalities show a more mature distribution than the national average.

Municipalities are shown to have an important role in the local system with an opportunity to influence the strategy, as a key part of each actor’s condition for agency, and thereby empower actions for a sustainable transition. The municipalities maturity relating to the use of strategic climate visions is communicated through many different roles of the governing organization including politicians, officials, civil servants and others. This leads to conflicting incentives to clarify or blur the defining concepts of the strategic climate vision for the system. Without a strategic vision to relate and align tactical and operational activities to the system, there is a risk for deviating from the intended transition pathway and to instead follow the undesired path towards lock-in, or face a backlash or even a system breakdown. Considering the detrimental risks of climate change it is highly doubtful that our society and planetary system can afford any transition pathway other than a successful transition (IPCC, Citation2022). Uniting around robust strategic visions is thus a necessary but not sufficient local, national and international requirement for becoming ‘the first climate neutral continent’ and part of avoiding irreversible climate change for current and future generations.

The complexity among the interconnected actors within the municipal organization calls for further studies to better understand the potential power struggle stemming from opposing incentives regarding vagueness in strategic visions between politicians, officials and other faces of the municipality. The screening results from Swedish municipalities also entail further questions about what are the explanatory factors for low, medium and high maturity, with suggestions like population size, economic power, location of universities for higher education and research. Building on the conflicting results from the membership organizations Climate- and Eco municipalities, further studies on the effectiveness of networking organizations focusing on climate-related strategic visions and evaluation is called for. Finally, the emerging wave of mission-oriented innovation systems for sustainable transitions will require major efforts in establishing systems thinking. This case highlights the need for the local actors to ‘zoom in and out’ in order to utilize their full agency for change in their system.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Max Rosvall

Max Rosvall holds an M.SC. in socio-technical systems engineering and a B.SC. in business with a current research focus on systems theory for sustainable development.

Mattias Gustafsson

Mattias Gustafsson is employed as a researcher at the University of Gävle. His research is focused on the energy system here, through various research projects to meet the challenges of the future society. Mattias is currently working in the academic world but has an extensive experience in the more problem-oriented world of municipalities and municipality-owned companies.

Magnus Åberg

Magnus Åberg has been an associate professor at Uppsala University since 2008. He defended his thesis “System effects of improved energy efficiency in district-heated buildings”, in 2014. Currently, he is working as a senior lecturer at the Division of Civil Engineering and Built Environment. Åberg is continuously researching on the system impacts of district-heated building energy efficiency, integration of carbon capture and storage in district heating and power systems, market aspects of district heating, and aspects of organising and managing energy system transitions.

Notes

1 The English equivalent of the Swedish keywords is: climate plan, climate goals, climate statements, environmental plan, environmental goals and environmental statements. The Swedish translation of an environmental policy is not commonly used by municipalities in Sweden. The broader search used the keywords environment, climate and sustainability.

References

- Avelino, F. (2011). Power in transition: Empowering discourses on sustainability transitions.

- Cho, J. Y., & Lee, E.-H. (2014). Reducing confusion about grounded theory and qualitative content analysis: Similarities and differences. Qualitative Report, 19(32). https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2014.1028.

- Damsø, T., Kjær, T., & Christensen, T. B. (2017). Implementation of local climate action plans: Copenhagen – Towards a carbon-neutral capital. Journal of Cleaner Production, 167(1), 406–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2017.08.156.

- de Jong, M., Joss, S., Schraven, D., Zhan, C., & Weijnen, M. (2015). Sustainable–smart–resilient–low carbon–eco–knowledge cities; making sense of a multitude of concepts promoting sustainable urbanization. Journal of Cleaner Production, 109(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.02.004.

- Eckerberg, K. (2001). Sweden problems and prospects at the leading edge of LA21 implementation. In Sustainable communities in Europe (pp. 15–40). Routledge.

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Ett klimatpolitiskt ramverk för Sverige. (2017). No. 2016/17:146.

- European Commission. (2022a). 2050 long-term strategy. https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/climate-strategies-targets/2050-long-term-strategy_en

- European Commission. (2022b). A European Green Deal [Text]. European Commission - European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en

- Fenton, P., & Gustafsson, S. (2017). Moving from high-level words to local action – Governance for urban sustainability in municipalities. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 26–27(Open issue part II), 129–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2017.07.009.

- Geels, F. W. (2002). Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: A multi-level perspective and a case-study. Research Policy, 31(8–9), 1257–1274. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00062-8

- Graute, U. (2016). Local authorities acting globally for sustainable development. Regional Studies, 50(11), 1931–1942. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1161740

- Grin, J. (2000). Vision assessment to support shaping 21 st century society? Technology assessment as a tool for political judgement. Vision Assessment: Shaping Technology in 21 St Century Society: Towards a Repertoire for Technology Assessment, 9–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-59702-2_2

- Grin, J., Rotmans, J., & Schot, J. (2010). Transitions to sustainable development: New directions in the study of long term transformative change. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203856598

- Gustafsson, S., & Mignon, I. (2020). Municipalities as intermediaries for the design and local implementation of climate visions. European Planning Studies, 28(6), 1161–1182. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1612327

- Hekkert, M. P., Janssen, M. J., Wesseling, J. H., & Negro, S. O. (2020). Mission-oriented innovation systems. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 34(1), 76–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.11.011.

- Hernández-Chea, R., Jain, A., Bocken, N. M. P., & Gurtoo, A. (2021). The business model in sustainability transitions: A conceptualization. Sustainability, 13(11), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13115763

- IPCC. (2018). Annex I: Glossary. https://archive.ipcc.ch/pdf/special-reports/sr15/sr15_glossary.pdf

- IPCC. (2022). Global warming of 1.5°C: IPCC special report on impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels in context of strengthening response to climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157940

- Isaksson, K., & Hagbert, P. (2020). Institutional capacity to integrate ‘radical’ perspectives on sustainability in small municipalities: Experiences from Sweden. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 36(1), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2020.05.002.

- Isaksson, R., & Hallencreutz, J. (2008). The measurement system resource as support for sustainable change. International Journal of Knowledge, Culture and Change Management, 8(1), 265–274. https://doi.org/10.18848/1447-9524/CGP/v08i01/50493.

- Kemp, R., & Loorbach, D. (2006). Reflexive Governance for Sustainable Development (pp. 103–130). Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- Kemp, R., & Rotmans, J. (2004). Managing the transition to sustainable mobility. System Innovation and the Transition to Sustainability: Theory, Evidence and Policy, 137–167.

- Keskitalo, E. C. H., & Liljenfeldt, J. (2012). Working with sustainability: Experiences of sustainability processes in Swedish municipalities. Natural Resources Forum, 36(1), 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-8947.2012.01442.x

- Khakee, A. (2002). Assessing institutional capital building in a local agenda 21 process in Goteborg. Planning Theory & Practice, 3(1), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649350220117807

- Köhler, J., Dütschke, E., & Wittmayer, J. (2021). Introduction to ‘zooming in and out: Special issue on local transition governance’. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 40(1), 203–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2021.07.005.

- Köhler, J., Geels, F. W., Kern, F., Markard, J., Onsongo, E., Wieczorek, A., Alkemade, F., Avelino, F., Bergek, A., & Boons, F. (2019). An agenda for sustainability transitions research: State of the art and future directions. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 31(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2019.01.004.

- Loorbach, D. (2010). Transition management for sustainable development: A prescriptive, complexity-based governance framework. Governance, 23(1), 161–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2009.01471.x

- Loorbach, D., Frantzeskaki, N., & Avelino, F. (2017). Sustainability transitions research: Transforming science and practice for societal change. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 42(1), 599–626. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102014-021340

- Loorbach, D., & Rotmans, J. (2010). The practice of transition management: Examples and lessons from four distinct cases. Futures, 42(3), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2009.11.009

- Markard, J., Raven, R., & Truffer, B. (2012). Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects. Research Policy, 41(6), 955–967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2012.02.013

- Moloney, S., Fünfgeld, H., & Granberg, M. (2018). Climate change responses from the global to local scale: An overview. In Local action on climate change (pp. 1–17). Routledge.

- Montin, S. (2007). Kommunerna och klimatpolitiken-ett exempel på tredje generationens politikområden. Statsvetenskaplig Tidskrift, 109(1).

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Purposeful sampling. In M. Q. Patton (Ed.), Qualitative research & evaluation methods (pp. 230–246). Sage.

- Regeringskansliet. (n.d.-a). Klimatlag (2017:720). Retrieved March 3, 2022, from https://lagen.nu/2017:720

- Regeringskansliet. (n.d.-b). Klimatpolitiska rådets uppdrag och behovet av en ny analysmodell. Retrieved March 3, 2022, from https://www.klimatpolitiskaradet.se/klimatpolitiska-radets-uppdrag-och-behovet-av-ett-nytt-analytiskt-ramverk/

- Regeringskansliet. (n.d.-c). Kommunallag (2017:725). Retrieved March 3, 2022, from https://lagen.nu/2017:725

- Rowe, J., & Fudge, C. (2003). Linking national sustainable development strategy and local implementation: A case study in Sweden. Local Environment, 8(2), 125–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354983032000048451

- Singh, G. G. (2020). Determining a path to a destination: Pairing strategic frameworks with the sustainable development goals to promote research and policy. Evolutionary and Institutional Economics Review, 17(2), 521–539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40844-020-00162-5

- Smith, A., Stirling, A., & Berkhout, F. (2005). The governance of sustainable socio-technical transitions. Research Policy, 34(10), 1491–1510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2005.07.005

- Späth, P., & Rohracher, H. (2010). ‘Energy regions’: The transformative power of regional discourses on socio-technical futures. Research Policy, 39(4), 449–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2010.01.017

- UN General Assembly. (2015, October 21). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. A/RES/70/1. https://www.refworld.org/docid/57b6e3e44.html